We read with interest the study recently published by Tré-Hardy et al., who reported that Adverse Events (AEs) after the first dose of mRNA-1273/Moderna vaccine were greater in those previously infected with COVID-191. Their findings are consistent with other studies that suggest mRNA vaccines may cause more AEs in those with a history SARS-CoV-2 infection [2], [3], [4]. These results warrant further investigation into the effects of prior COVID-19 history on vaccine reactions, particularly whether time between previous infection and vaccination administration, or the presence of ‘Long-COVID’ [5], can predict AEs. This information is important, as it could identify individuals more likely to experience side effects to COVID-19 vaccines. Furthermore, there are implications regarding vaccine hesitancy, which is partially driven by fear of AEs [6]. As part of an observational study of COVID-19 outcomes in healthcare workers in North-East England, we evaluated AEs following first doses of BNT162b2/Pfizer vaccine, with reference to previous COVID-19 and Long-COVID.

Healthcare workers completed an electronic survey, which captured self-reported COVID-19 symptoms, PCR/antibody results, and AEs following first doses. The FDA Toxicity Grading Scale [7] was modified, allowing participants to self-report AEs for severity (mild/moderate/severe/very severe), duration (≤24 h/>24 h) and onset (≤24 h/>24 h); lymphadenopathy was also included. A composite score for symptom nature and severity was calculated, to provide an overall estimate of AE-related morbidity. Individual and composite AE scores were compared between those with and without a prior history of COVID-19, as indicated by self-reported prior positive antibody and/or PCR result. Long-COVID was defined as symptoms persisting for >2 months prior to vaccination. Effects of age, gender and time between past infection to vaccination were also considered.

Respondents who permitted laboratory results to be accessed (SARS-CoV-2 PCR/antibody), formed a subgroup for a ‘sensitivity analysis’. Statistical analysis was conducted using JASPv0.14.1.0. Composite scores were compared using 2-way ANCOVA. Multivariable logistic regressions were used, to identify the relationship between COVID-19 status and moderate/severe symptoms in each category, and the Bonferroni correction applied to the resulting significance/confidence intervals. The study was approved by Cambridge East Research Ethics Committee.

Of 974 healthcare workers (aged 19–72-years) responding to the survey and providing complete data for analysis, 265 (27%) participants (84% female, mean-age 48.9) reported a prior positive PCR and/or antibody result, and 709 (80% female, mean-age 47.0) had no COVID-19 history. Within the previous COVID-19 group (symptoms median 8.9 months before vaccination), 30 (83% female, mean-age 48.8) complained of Long-COVID (median duration 9.3 months, range 2.8–10.4).

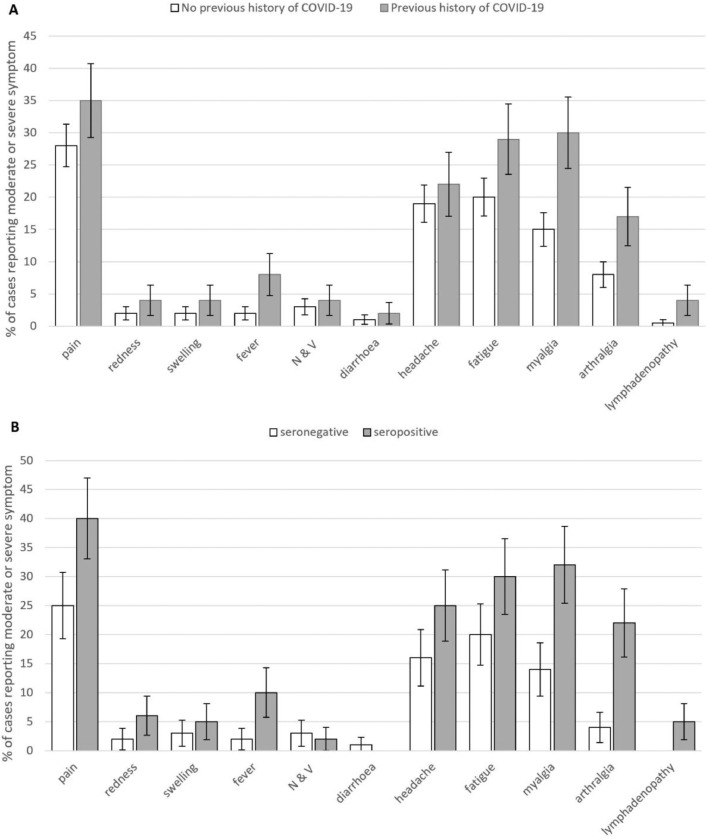

Fig. 1A shows frequencies of each symptom by COVID-19 status. The proportion of participants reporting at least one moderate-to-severe symptom was higher in the previous COVID-19 group (56% v 47%, OR=1.5 [95%CI, 1.1–2.0], p=.009). Symptom onset was mostly within 24 h (75%) with no onset >48 h. Number and total duration of reported symptoms was greater in women (1.24 (1.67) v 0.84 (1.46) symptoms, d = 0.25 [0.09–0.42], p=.002; 2.10 (2.99) v 1.39 (2.54) symptom-days, d = 0.22 [0.09–0.42], p=.001) and significantly decreased with age (symptoms: rs=−0.25, p<.001; symptom-days: rs=−0.24, p<.001). After controlling for age and sex, higher symptom number (1.61 (2.26) v 0.89 (2.02) symptoms, d = 0.34 [0.20–0.49], p<.001) and severity (2.7 (6.65) v 1.5 (2.21) symptom-days, d = 0.41 [0.27–0.55], p<.001) were significantly associated with reporting previous COVID-19.

Fig. 1.

Moderate and Severe Symptoms by COVID-19 Status: Percentage of cases reporting moderate or severe symptoms (95% CI) in those with and without a history of COVID-19 (the former including Long-COVID). N & V: nausea and vomiting. Upper panel (A): entire cohort; lower panel (B): sensitivity analysis subset.

Logistic regressions (Table 1 ) controlling for age and sex showed five systemic symptoms were significantly associated with previous COVID-19 status: fever, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia and lymphadenopathy. Arthralgia was regularly co-reported with myalgia (87 cases), but rarely alone, and was not independently associated (OR 1.4 [95%CI 0.86–2.37], p=.49) with COVID-19 exposure once myalgia was controlled for. Neither local nor gastrointestinal symptoms were significantly associated with previous COVID-19 history.

Table 1.

Results of Logistic Regression Analyses: Logistic regressions showing those symptoms significantly predicted by previous history of COVID-19 after controlling for differences in age and gender, and with p values and confidence intervals corrected (Bonferroni) for multiple comparisons.

| Whole cohort | Sensitivity Analysis Subset | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio (95% C.I.) | p | Odds Ratio (95% C.I.) | p | |

| Fever | 2.87 (1.10 – 7.51) | .044 | 5.68 (0.69 – 46.65) | .32 |

| Fatigue | 1.78 (1.12 – 2.84) | .011 | 2.17 (0.85– 5.54) | .31 |

| Myalgia | 2.34 (1.44 – 3.88) | <0.001 | 3.18 (1.16 – 8.69) | .02 |

| Arthralgia | 2.25 (1.23 – 4.12) | .004 | 7.06 (2.05 – 36.91) | .01 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 5.18 (1.19 – 22.63) | .033 | **** | **** |

| Local Pain | 1.55 (0.99 – 2.40) | .09 | 2.28 (0.96 – 5.43) | .11 |

| Local Redness | 2.93 (0.84 – 10.20) | .24 | 3.92 (0.43 – 35.79) | >0.99 |

| Local Swelling | 2.0 (0.64 – 6.27) | .14 | 2.1 (0.29 – 15.33) | >0.99 |

| n & v | 1.47 (0.48 – 4.42) | >0.99 | 0.72 (0.05 – 8.81) | >0.99 |

| diarrhea | 2.35 (0.30 – 18.25) | >0.99 | **** | **** |

| Headache | 1.31 (0.80 – 2.15) | >0.99 | 1.78 (0.65 – 4.83) | >0.99 |

**** No model could be calculated due to absence of cases in this cohort. In all cases age and gender were included in the null model as nuisance variables. Adjusted P values and adjusted confidence intervals corrected (Bonferroni) for 11 outcomes in each case.

Symptom number and duration was not significantly higher in those with Long-COVID after accounting for gender and age effects. No individual symptom was significantly associated with this condition. Importantly, among those with prior COVID-19, there was no significant relationship between illness-vaccine time interval and either composite score (rs=0.09, p=.44 for symptoms; rs=0.10, p=.42 for symptom–days), nor any difference in mean time interval based on presence of any of the symptoms (all p>.05).

For the ‘sensitivity analysis’, PCR/antibody results were verified for 412 participants. Of this subgroup, 228 (55%) were PCR/antibody negative (80% female, mean-(SD)-age 47.0 [11.1]) and 184 (45%) were PCR or antibody positive (91% female, mean-(SD)-age 47.3 [11.5]). Nine (5%) complained of Long-COVID (range 2.8–10.4 months). The pattern of results was broadly replicated in this subgroup analysis (Fig. 1B), with more previous-COVID-19 individuals reporting at least one moderate symptom (63% v 43%, OR=2.2 [1.2–4.0], p=.006) and previous-COVID-19 being associated with higher symptom number (1.81 (3.09) v 0.85 (4.12) symptoms, d = 0.25 [0.05–0.44] p=.012) and severity (3.0 (8.3) v 1.5 (5.6) symptom days d = 0.2 [95% CI 0.02–0.41], p=.0350). Only myalgia and arthralgia remain as significant outcomes once multiple comparisons were controlled for though pattern of outcomes remains similar.

This study of healthcare workers demonstrated that prior COVID-19, but not Long-COVID, was associated with increased risk of AEs following BNT162b2/Pfizer vaccination, although there was no relationship with duration since COVID-19 illness. Women and younger individuals were also more likely to report AEs. Our study adds to other reports supporting the wider understanding of AEs following COVID-19 vaccination [1], [2], [3], [4]. Importantly, given hesitancy surrounding recently developed COVID-19 vaccines [6], our findings may help inform those with previous COVID-19 of increased susceptibility to certain AEs. Our study also adds weight to the question of whether a second dose of mRNA vaccine is necessary in those with previous COVID-19, assuming effective immunity is established after the first dose [1,2,8,9]. This is relevant, given that Tre-Hardy's and other studies have reported worse AEs following second doses of vaccine [1,3].

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, some non-responder bias[ 10 ] is likely, with 27% of participants reporting previous COVID-19. Secondly, AE information was gathered via self-reported questionnaires, and hence was subjective. Thirdly, PCR/antibody results were self-reported. We addressed this via a sensitivity analysis on a subset with laboratory data available, which mostly confirmed the findings. Finally, numbers of participants with Long-COVID were relatively small for comparison.

Author contributions

DRC/CK/RKR conceived the study and DRC is chief investigator of CHOIS. RKR acted as site principal investigator. DRC/RKR/CW contributed to the study protocol, design, and data collection. JR/RKR/DRC did the statistical analysis. RKR/JR/DRC prepared the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version.

Declarations of Competing Interest

No conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the CHOIS research team, John Rouse and the North East and North Cumbria NIHR for assistance with the survey. The CHOIS study was supported by the North East and North Cumbria Academic Health Sciences Network (AHSN) and Siemens Healthcare Ltd, who provided assays – but had no input into the study design.

References

- 1.Tré-Hardy M., Cupaiolo R., Papleux E., et al. Reactogenicity, safety and antibody response, after one and two doses of mRNA-1273 in seronegative and seropositive healthcare workers. J Infect. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2021.03.025. Article in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krammer F., Srivastava K., Marks F., et al. Robust spike antibody responses and increased reactogenicity in seropositive individuals after a 1 single dose of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.29.21250653. 2021.01.29.21250653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kings College London COVID Symptom Study. Here's what we know so far about the after effects of the Pfizer COVID vaccine. 2021. https://covid.joinzoe.com/post/covid-vaccine-pfizer-effects (accessed Feb 5, 2021).

- 4.Mathioudakis A.G., Ghrew M., Ustianowski A. et al. Self-reported real-world safety and reactogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines: an international vaccine-recipient survey. MedRxiv 2021; 2021.02.26.21252096. doi: 10.1101/2021.02.26.21252096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Carfì A., Bernabei R., Landi F. Gemelli against COVID-19 post-acute care study group. persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324(6):603–605. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barello S., Nania T., Dellafiore F., Graffigna G., Caruso R. Vaccine hesitancy' among university students in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J Epidemiol. 2020;35(8):781–783. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00670-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry toxicity grading scale for healthy adult and adolescent volunteers enrolled in preventive vaccine clinical trials. 2021. https://www.fda.gov/media/73679/download (accessed Feb 5, 2021).

- 8.Manisty C., Otter A.D., Treibel T.A., et al. Antibody response to first BNT162b2 dose in previously SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. Lancet. 2021;397:1057–1058. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00501-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shields A., Faustini S.E., Perez-Toledo M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and asymptomatic viral carriage in healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Thorax. 2020;75(12):1089–1094. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sax L.J., Gilmartin S.K., Bryant A.N. Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Res High Edu. 2003;44(4):409–432. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2006.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]