Abstract

The deficiency of vitamin D has been reported to be relevant to cancer risk. DHCR7 and CYP2R1 are crucial components of vitamin D-metabolizing enzymes. Thus, accumulating researchers are concerned with the correlation between polymorphisms of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 genes and cancer susceptibility. Nevertheless, the conclusions of literatures are inconsistent. We conducted an integrated review for the correlation of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs with cancer susceptibility. In the meanwhile, a meta-analysis was performed using accessible data to clarify the association between DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs and overall cancer risk. Literatures which meet the rigid inclusion and exclusion criteria were involved. The association of each SNP with cancer risk was calculated by odds ratios (ORs). 12 case-control designed studies covering 23780 cases and 27307 controls were ultimately evolved in the present meta-analysis of five SNPs (DHCR7 rs12785878 and rs1790349 SNP; CYP2R1 rs10741657, rs12794714, and rs2060793 SNP). We found that DHCR7 rs12785878 SNP was significantly related to cancer risk in the whole population, Caucasian subgroup, and hospital-based (HB) subgroup. DHCR7 rs1790349 SNP was analyzed to increase cancer risk in Caucasians. Moreover, CYP2R1 rs12794714-A allele had correlation with a lower risk of colorectal cancer. Our findings indicated that rs12785878, rs1790349, and rs12794714 SNPs might potentially be biomarkers for cancer susceptibility.

1. Introduction

Vitamin D, also regarded as 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, is a pivotal steroid prohormone which has a significant role to play in musculoskeletal health [1]. Additionally, compelling evidence reveals the roles of vitamin D on extraskeletal diseases, such as infectious disease [2], cardiovascular disease [3], autoimmune disease [4], neurodegeneration [5], and cancer [6]. Deficiency of vitamin D has been reported to be relevant to oral squamous cell carcinoma [7], breast cancer [8], colorectal cancer [9], prostate cancer [10], pancreas cancer [11], thyroid cancer [12], hepatocellular carcinoma [13], and ovarian cancer [14]. Furthermore, vitamin D supplementation may decrease the death of cancer by 16% [15].

There has an individual variability in serum vitamin D stores which cannot be explained alone by age, sunlight exposure, body mass index, or dietary intake [12]. Studies have demonstrated that vitamin D level is highly heritable [16]. Genetic and epigenetic factors can impact several crucial steps along the metabolic pathway of vitamin D. Genes who directly participate in the vitamin D pathway gene are DHCR7, CYP2R1, VDR, CYP24A1, CYP27B1, and so on, and the aberrant expressions of them have been demonstrated to be associated with vitamin D concentrations and cancer [17–21]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have detected the correlations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on genes that participated in the vitamin D metabolic pathway [1, 16].

DHCR7, located on chromosome 11q13.4, encodes ultimate enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase which catalyzes the conversion of the vitamin D3 precursor (7-dehydrocholesterol) to cholesterol, instead of vitamin D3 [22]. Cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily R member 1 (CYP2R1, on chromosome 11p15.2) encodes vitamin D 25-hydroxylase which catalyzes the initial hydroxylation reaction of vitamin D synthesis, converting vitamin D to 25-hydroxyvitamin D [9]. Increasing correlational studies were concerned with DHCR7 and CYP2R1 polymorphisms and susceptibility to cancer. Some studies confirmed the associations, whereas others remained skeptical or denied their correlations. The aim of the present study was to explore whether the DHCR7 or CYP2R1 SNPs are related to cancer risk.

We comprehensively reviewed the eligible studies and analyzed all available data. Our aim is to explore the association of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs with cancer risk, supplying clues to researchers for screening novel cancer biomarkers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Retrieval Strategy

Two investigators (J.W. and J.L.), respectively, carried out a comprehensive literature retrieval in PubMed and Web of Science database up to February 2020, by using the following query terms: “CYP2R1/cytochrome P450 family 2 subfamily R member 1/DHCR7/7-dehydrocholesterol reductase”, “polymorphism/SNP/variant/variation”, and “cancer/carcinoma/neoplasm/tumor/”. All enrolled articles must satisfy inclusion standards: (1) case-control or nested case-control designed study; (2) in regard to the association of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs with predisposition to cancer. Meanwhile, publications meeting the following exclusion standards were removed: (1) letters or reviews; (2) repeated records; (3) irrelevant to DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs or carcinoma; (4) without any available genotype distribution data.

2.2. Data Extraction

Data was collected by two investigators (J.W. and J.L.) independently and came to a consensus regarding all items. Essential characteristics extracted from each qualified publication comprised first author, year of publication, ethnicity, sample size, type of carcinoma, gene, SNPs, genotype distribution frequency of case and control groups, control group source (hospital-based (HB) or population-based (PB)), Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), adjustment factors, and genotyping method. When multiple studies were conducted in one article, data were collected individually.

2.3. Methodology Quality Assessment

Two authors (J.W. and X.L.) scored the quality of each enrolled publication independently, based on a scoring scheme mentioned in prior literature [23, 24]. Six evaluation items were involved in the scoring scheme: representativeness of cases, control source, ascertainment of carcinomas, sample size, HWE in the control group, and quality assurance of genotyping methods. The quality assessment scores ranged from 0 to 10. Study with no less than 5 quality scores was recognized as an eligible study which could be enrolled in subsequent analysis.

2.4. False-Positive Report Probability

False-positive report probability (FPRP) was computed to estimate whether our study findings are “noteworthy.” Initially, we computed the statistic power of the test based on the sample size, ORs, and P values by using NCSS-PASS software (USA, version 11.0.7). Then, we drew the FPRP values from a calculation formula which had been reported in earlier researches, and FPRP < 0.5 was regarded as a noteworthy finding [25].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test (χ2 test) was conducted to compute the HWE for genotype frequency distribution of CYP2R1 and DHCR7 polymorphisms in controls. The correlation of each CYP2R1 and DHCR7 polymorphism with carcinoma risk was computed by odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Cochran's χ2-based Q test was adopted to estimate the heterogeneity of interstudy (significance set as P < 0.10, I2 > 50%). We pooled the results by means of a fixed-effects model when no interstudy heterogeneity arose; the random-effects model was adopted otherwise. Besides, the recessive and dominant genetic models were, respectively, considered as variant homozygote vs. heterozygote/wild homozygote, and heterozygote/variant homozygote vs. wild homozygote. Publication bias was estimated using the rank correlation test (Begg's test) and linear regression methods (Egger's test). Sensitivity analysis was calculated to show whether the merged findings were steady enough after removing those outlying studies. All the mentioned statistical analyses were calculated by STATA software (STATA Corp., College Station, TX, USA, version 11.0). All P values were for two-tailed tests, and less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Features of Eligible Studies and Analyzed SNPs

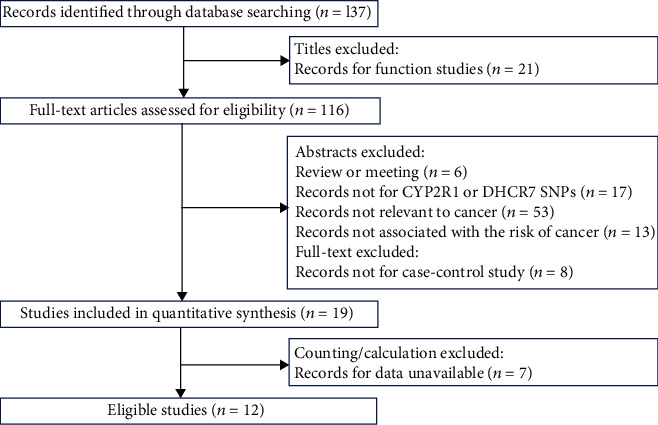

Totally 137 publications were gathered through database retrieval after removing duplicate hits. 125 articles were removed after browsing titles and abstracts: 21 were functional studies; 6 were review or meeting; 8 were not case-control studies; 17 were not related to DHCR7 or CYP2R1 SNPs; 53 were not concerned with carcinoma; and 13 were not correlated with carcinoma risk. Therefore, 19 studies are ought to be involved in the present analysis. Nevertheless, 7 publications lost original data, 5 of which were genome-wide association studies. And we were not able to contact with authors. Thus, 12 case-control designed studies were finally evolved in the present meta-analysis, covering 23780 cases and 27307 controls, which is shown in Figure 1. The features of these eligible studies which met the quality assessment criterion are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

The flow chart of identification for studies included in the meta-analysis based on PRISMA guidelines.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies.

| No. | First author | Year | Ethnicity | Sample size | Source of control groups | Genotyping method | Adjusted factors | Citation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | ||||||||

| 1 | Isabel S. Carvalho | 2019 | Caucasian (Portugal) | 500 | 500 | PB | PCR-RFLP | Age, sex | [12] |

| 2 | Prajjalendra Barooah | 2019 | Caucasian (Indian) | 60 | 102 | HB | PCR-RFLP | Age, sex | [13] |

| 3 | Jianzhou Yang | 2017 | Asian (China) | 565 | 557 | PB | GenomeLab SNPstream | Age, sex | [35] |

| 4 | Alison M. Mondul | 2015 | Caucasian (European) | 8618 | 9960 | HB | TaqMan or genome-wide scans | Age | [36] |

| 5 | Tess V. Clendenen | 2015 | Caucasian (Swedish) | 733 | 1432 | PB | Illumina GoldenGate assay | Age, menopausal status | [37] |

| 6 | Fabio Pibiri | 2014 | African (African-American) | 902 | 760 | PB | Sequenom MassARRAY | Age, sex, ancestry | [38] |

| 7 | Touraj Mahmoudi | 2014 | Caucasian (Iranian) | 290 | 354 | HB | PCR-RFLP | Age, BMI, sex | [9] |

| 8 | Wei Wang | 2014 | Caucasian (Hispanic) | 826 | 779 | PB | Illumina GoldenGate assay | Age, BMI | |

| Wei Wang | 2014 | Mixed (non-Hispanic) | 224 | 130 | PB | Illumina GoldenGate assay | Age, BMI | [39] | |

| 9 | Christian M. Lange | 2013 | Asian (Japanese) | 803 | 1253 | HB | Competitive allele-specific TaqMan PCR | Sex | [40] |

| 10 | Alison M. Mondul | 2013 | Caucasian | 9378 | 9986 | PB | TaqMan | Age, ethnicity | [41] |

| 11 | Laura N. Anderson | 2013 | Caucasian (Canada) | 628 | 1192 | PB | MassARRAY | Age, sex | [11] |

| 12 | Marissa Penna-Martinez | 2012 | Caucasian (Germany) | 253 | 302 | PB | TaqMan | NM | [42] |

Note: HB: hospital based; PB: population based; PCR-RFLP: in reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism; NM: not mentioned.

Six polymorphisms were able to be involved in our systematic review, including rs10741657 G/A, rs12794714 G/A, rs2060793 G/A, rs3829251 G/A, rs12785878 T/G, and rs1790349 A/G. The frequency distribution of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs genotype is shown in Table 2. Six records, however, were removed from quantitative synthesis owing to the insufficient study number for some loci or being not conformed to HWE (PHWE < 0.05). Consequently, five SNPs were covered in the eventual meta-analysis. For DHCR7, the analyzed SNPs were rs12785878 T/G and rs1790349 A/G; for CYP2R1, the analyzed SNPs were rs10741657 G/A, rs12794714 G/A, and rs2060793 G/A.

Table 2.

Genotype frequency distributions of lncRNA SNPs studied in included studies.

| First author | Year | Gene | SNPsa | Type of cancer | Ethnicity | Sample size | Case | Control | Quality score | P HWE | Included in meta-analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | Homozygote wild | Heterozygote | Homozygote variant | Homozygote wild | Heterozygote | Homozygote variant | |||||||||

| Isabel S. Carvalho | 2019 | CYP2R1 | rs2060793 (G/A) | TC | Caucasian (Portugal) | 500 | 500 | 189 | 236 | 75 | 183 | 256 | 61 | 7 | 0.047 | Noc |

| 2019 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | TC | Caucasian (Portugal) | 500 | 500 | 150 | 251 | 99 | 197 | 234 | 69 | 7 | 0.971 | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Prajjalendra Barooah | 2019 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | HCC | Caucasian (Indian) | 60 | 102 | 28 | 23 | 9 | 51 | 35 | 16 | 4.5 | 0.025 | Noc |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Jianzhou Yang | 2017 | DHCR7 | rs3829251 (G/A) | ESCC | Asian (China) | 565 | 557 | 302 | 218 | 45 | 283 | 232 | 42 | 8 | 0.557 | Nob |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Alison M. Mondul | 2015 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | BC | Caucasian (European) | 8618 | 9960 | 3276 | 4041 | 1301 | 3708 | 4766 | 1486 | 6.5 | 0.475 | Yes |

| 2015 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | BC | Caucasian (European) | 9224 | 10560 | 4935 | 3620 | 669 | 5674 | 4052 | 834 | 5.5 | 0.003 | Noc | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Tess V. Clendenen | 2015 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | BC | Caucasian (Swedish) | 733 | 1432 | 200 | 358 | 175 | 405 | 720 | 307 | 7.5 | 0.696 | Yes |

| 2015 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | BC | Caucasian (Swedish) | 733 | 1433 | 273 | 371 | 89 | 571 | 659 | 203 | 7.5 | 0.562 | Yes | |

| 2015 | DHCR7 | rs1790349 (A/G) | BC | Caucasian (Swedish) | 732 | 1431 | 348 | 326 | 58 | 752 | 571 | 108 | 7.5 | 0.978 | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Fabio Pibiri | 2014 | CYP2R1 | rs12794714 (G/A) | CRC | African (African-American) | 902 | 760 | 638 | 253 | 11 | 501 | 239 | 20 | 9.5 | 0.175 | Yes |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Touraj Mahmoudi | 2014 | CYP2R1 | rs12794714 (G/A) | CRC | Caucasian (Iranian) | 290 | 354 | 93 | 135 | 62 | 110 | 167 | 77 | 7 | 0.364 | Yes |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Wei Wang | 2014 | CYP2R1 | rs2060793 (G/A) | BC | Mixed (Hispanic) | 826 | 779 | 303 | 391 | 132 | 315 | 356 | 108 | 9.5 | 0.644 | Yes |

| 2014 | CYP2R1 | rs2060793 (G/A) | Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 224 | 130 | 89 | 104 | 31 | 51 | 58 | 21 | 8.5 | 0.512 | Yes | ||

| 2014 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | BC | Mixed (Hispanic) | 826 | 779 | 189 | 410 | 227 | 185 | 353 | 241 | 7.5 | 0.013 | Noc | |

| 2014 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | BC | Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 224 | 130 | 123 | 90 | 11 | 62 | 55 | 13 | 8.5 | 0.876 | Yes | |

| 2014 | DHCR7 | rs1790349 (A/G) | BC | Mixed (Hispanic) | 826 | 779 | 573 | 227 | 26 | 527 | 227 | 25 | 8.5 | 0.927 | Yes | |

| 2014 | DHCR7 | rs1790349 (A/G) | BC | Caucasian (non-Hispanic) | 224 | 130 | 168 | 52 | 4 | 95 | 30 | 5 | 8.5 | 0.195 | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Christian M. Lange | 2013 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | HCC | Asian (Japanese) | 803 | 1253 | 320 | 377 | 106 | 482 | 597 | 174 | 8.5 | 0.615 | Yes |

| 2013 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | HCC | Asian (Japanese) | 803 | 1253 | 84 | 336 | 383 | 153 | 543 | 557 | 8.5 | 0.247 | Yes | |

| 2013 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | HCC | Caucasian (German) | 116 | 208 | 63 | 44 | 9 | 113 | 77 | 18 | 8.5 | 0.353 | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Alison M. Mondul | 2013 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | PC1 | Caucasian | 9378 | 9986 | 3481 | 4392 | 1505 | 3789 | 4667 | 1530 | 9 | 0.137 | Yes |

| 2013 | DHCR7 | rs12785878 (T/G) | PC1 | Caucasian | 9620 | 10225 | 4979 | 3816 | 825 | 5221 | 4047 | 957 | 8 | 2.401E − 05 | Noc | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Laura N. Anderson | 2013 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | PC2 | Caucasian (Canada) | 625 | 1191 | 262 | 286 | 77 | 451 | 550 | 190 | 8 | 0.304 | Yes |

| 2013 | CYP2R1 | rs12794714 (G/A) | PC2 | Caucasian (Canada) | 628 | 1192 | 180 | 307 | 141 | 399 | 559 | 234 | 8 | 0.131 | Yes | |

|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Marissa Penna-Martinez | 2012 | CYP2R1 | rs10741657 (G/A) | TC | Caucasian (German) | 253 | 302 | 96 | 110 | 47 | 119 | 139 | 44 | 7.5 | 0.742 | Yes |

| 2012 | CYP2R1 | rs12794714 (G/A) | TC | Caucasian (German) | 253 | 302 | 78 | 130 | 45 | 94 | 144 | 64 | 7.5 | 0.522 | Yes | |

Note: PHWE: the P value for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in control groups; amajor/minor; bexcluded due to the limited number for this locus; cexcluded due to the SNP not being in accordance with HWE. The results are in bold if P < 0.05; TC = thyroid cancer; HCC = hepatocellular carcinoma; ESCC = esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; BC = breast cancer; PC1 = prostate cancer; PC2 = pancreas cancer.

3.2. Quantitative Data Synthesis of Five SNPs in DHCR7 and CYP2R1 Genes

3.2.1. Two Polymorphisms in DHCR7 Gene

Five eligible studies were collected to evaluate the relationships between DHCR7 SNPs and risk of carcinoma, on the basis of entire population. The rs12785878 T/G SNP was illustrated to be associated with incremental cancer risk. The correlation of rs12785878 T/G SNP was discovered under the heterozygote genotype model (TG vs. TT: OR (95%CI) = 1.168 (1.027-1.328), P = 0.018, Table 3). The relationship between rs1790349 A/G SNP and carcinoma risk was not found in the initial analysis.

Table 3.

Meta-analysis of the association between common SNPs and cancer risk.

| Stratification | N | Heterozygote vs. wild-type | Mutation homozygote vs. wild-type | Dominant model | Recessive model | Allelic model | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | I 2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | I 2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | I 2 (%) | OR (95% CI) | P | I 2(%) | OR (95% CI) | P | I 2 (%) | ||

| CYP2R1 | ||||||||||||||||

| rs10741657 (G/A) | 6 | 0.987 (0.947-1.028) | 0.522 | 0 | 1.006 (0.906-1.117) | 0.905 | 50.9 | 0.995 (0.957-1.034) | 0.799 | 18.4 | 1.030 (0.978-1.084) | 0.264 | 41.2 | 0.998 (0.949-1.050) | 0.943 | 51.2 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 5 | 0.989 (0.948-1.031) | 0.587 | 0 | 1.016 (0.905-1.142) | 0.785 | 58.2 | 0.997 (0.959-1.038) | 0.901 | 30.8 | 1.030 (0.936-1.133) | 0.543 | 50.2 | 1.003 (0.948-1.061) | 0.917 | 58.5 |

| Asian | 1 | 0.951 (0.786-1.152) | 0.608 | NA | 0.918 (0.694-1.214) | 0.547 | NA | 0.944 (0.787-1.131) | 0.531 | NA | 0.943 (0.727-1.223) | 0.658 | NA | 0.957 (0.840-1.089) | 0.503 | NA |

| Type of cancer | ||||||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 2 | 0.963 (0.907-1.023) | 0.227 | 0 | 1.008 (0.927-1.095) | 0.858 | 20.7 | 0.974 (0.920-1.031) | 0.361 | 0 | 1.030 (0.955-1.111) | 0.442 | 14.9 | 0.995 (0.957-1.036) | 0.817 | 31.1 |

| Pancreas cancer 2 | 1 | 0.895 (0.726-1.103) | 0.289 | NA | 0.698 (0.514-0.947) | 0.021 | NA | 0.844 (0.693-1.029) | 0.093 | NA | 0.740 (0.557-0.984) | 0.038 | NA | 0.848 (0.736-0.978) | 0.023 | NA |

| Prostate cancer | 1 | 1.024 (0.963-1.090) | 0.445 | NA | 1.071 (0.984-1.165) | 0.114 | NA | 1.036 (0.977-1.098) | 0.236 | NA | 1.057 (0.978-1.142) | 0.165 | NA | 1.033 (0.992-1.076) | 0.118 | NA |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1 | 0.951 (0.786-1.152) | 0.608 | NA | 0.918 (0.694-1.214) | 0.547 | NA | 0.944 (0.787-1.131) | 0.531 | NA | 0.943 (0.727-1.223) | 0.658 | NA | 0.957 (0.840-1.089) | 0.503 | NA |

| Thyroid caner | 1 | 0.981 (0.679-1.416) | 0.918 | NA | 1.324 (0.810-2.164) | 0.263 | NA | 1.063 (0.755-1.499) | 0.725 | NA | 1.338 (0.853-2.098) | 0.205 | NA | 1.122 (0.881-1.429) | 0.352 | NA |

| Source of controls | ||||||||||||||||

| HB | 2 | 0.959 (0.903-1.018) | 0.169 | 0 | 0.984 (0.905-1.070) | 0.709 | 0 | 0.965 (0.912-1.021) | 0.214 | 0 | 1.007 (0.933-1.088) | 0.85 | 0 | 0.984 (0.946-1.024) | 0.437 | 0 |

| PB | 4 | 1.012 (0.957-1.071) | 0.677 | 0 | 1.020 (0.829-1.256) | 0.849 | 64.6 | 1.022 (0.969-1.078) | 0.415 | 23.5 | 1.032 (0.867-1.229) | 0.723 | 60.7 | 1.007 (0.913-1.110) | 0.89 | 62.3 |

| rs12794714 (G/A) | 4 | 1.007 (0.825-1.231) | 0.942 | 51 | 0.908 (0.609-1.352) | 0.634 | 68 | 0.993 (0.789-1.249) | 0.953 | 66.2 | 0.907 (0.664-1.239) | 0.539 | 58.9 | 0.968 (0.807-1.160) | 0.723 | 72.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 3 | 1.127 (0.951-1.336) | 0.167 | 0 | 1.134 (0.921-1.397) | 0.236 | 40.9 | 1.130 (0.964-1.326) | 0.132 | 10.5 | 1.056 (0.881-1.265) | 0.558 | 24.8 | 1.074 (0.967-1.192) | 0.183 | 41.2 |

| African | 1 | 0.831 (0.672-1.028) | 0.088 | NA | 0.432 (0.205-0.910) | 0.027 | NA | 0.800 (0.650-0.985) | 0.036 | NA | 0.457 (0.217-0.959) | 0.039 | NA | 0.800 (0.666-0.960) | 0.017 | NA |

| Type of cancer | ||||||||||||||||

| Colorectal cancer | 2 | 0.862 (0.718-1.035) | 0.111 | 0 | 0.681 (0.317-1.466) | 0.326 | 69.1 | 0.841 (0.705-1.003) | 0.054 | 0 | 0.717 (0.344-1.493) | 0.374 | 68.9 | 0.866 (0.753-0.997) | 0.046 | 44.1 |

| Pancreas cancer | 1 | 1.217 (0.973-1.524) | 0.086 | NA | 1.336 (1.016-1.775) | 0.038 | NA | 1.252 (1.014-1.546) | 0.036 | NA | 1.185 (0.936-1.500) | 0.157 | NA | 1.167 (1.017-1.339) | 0.028 | NA |

| Thyroid caner | 1 | 1.088 (0.742-1.595) | 0.666 | NA | 0.847 (0.522-1.377) | 0.504 | NA | 1.014 (0.706-1.455) | 0.94 | NA | 0.805 (0.526-1.230) | 0.315 | NA | 0.939 (0.740-1.191) | 0.604 | NA |

| Source of controls | ||||||||||||||||

| HB | 1 | 0.956 (0.669-1.367) | 0.806 | NA | 0.952 (0.617-1.469) | 0.825 | NA | 0.955 (0.684-1.333) | 0.787 | NA | 0.978 (0.671-1.427) | 0.909 | NA | 0.973 (0.780-1.213) | 0.806 | NA |

| PB | 3 | 1.023 (0.787-1.331) | 0.864 | 66.9 | 0.856 (0.476-1.538) | 0.602 | 78 | 1.004 (0.742-1.360) | 0.978 | 77.3 | 0.839 (0.522-1.348) | 0.468 | 72.5 | 0.963 (0.754-1.231) | 0.765 | 81.6 |

| rs2060793 (G/A) | 2 | 1.121 (0.923-1.362) | 0.247 | 0 | 1.184 (0.902-1.554) | 0.223 | 19 | 1.136 (0.946-1.364) | 0.172 | 0 | 1.113 (0.866-1.430) | 0.402 | 6.3 | 1.098 (0.964-1.250) | 0.16 | 8.4 |

| DHCR7 | ||||||||||||||||

| rs12785878 (T/G) | 5 | 1.168 (1.027-1.328) | 0.018 | 8.3 | 1.074 (0.736-1.569) | 0.71 | 73.1 | 1.136 (0.935-1.381) | 0.2 | 53.2 | 1.017 (0.762-1.357) | 0.91 | 67.5 | 1.064 (0.906-1.250) | 0.448 | 70.1 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 4 | 1.178 (1.021-1.358) | 0.024 | 30.1 | 0.980 (0.562-1.710) | 0.944 | 79.2 | 1.108 (0.854-1.436) | 0.441 | 64.8 | 0.929 (0.584-1.477) | 0.756 | 73.7 | 1.031 (0.814-1.305) | 0.802 | 77.2 |

| Asian | 1 | 1.127 (0.836-1.520) | 0.433 | NA | 1.252 (0.931-1.684) | 0.136 | NA | 1.191 (0.898-1.579) | 0.226 | NA | 1.139 (0.954-1.361) | 0.15 | NA | 1.120 (0.980-1.281) | 0.097 | NA |

| Type of cancer | ||||||||||||||||

| Breast cancer | 2 | 1.048 (0.756-1.454) | 0.778 | 50.1 | 0.699 (0.341-1.433) | 0.328 | 63.5 | 0.961 (0.658-1.404) | 0.838 | 63.9 | 0.795 (0.616-1.025) | 0.077 | 42.4 | 0.899 (0.665-1.215) | 0.488 | 66.1 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 2 | 1.098 (0.851-1.415) | 0.472 | 0 | 1.209 (0.913-1.599) | 0.185 | 0 | 1.135 (0.893-1.442) | 0.302 | 0 | 1.127 (0.947-1.341) | 0.177 | 0 | 1.102 (0.972-1.250) | 0.129 | 0 |

| Thyroid caner | 1 | 1.409 (1.068-1.859) | 0.015 | NA | 1.884 (1.297-2.738) | 0.001 | NA | 1.517 (1.167-1.972) | 0.002 | NA | 1.542 (1.102-2.158) | 0.012 | NA | 1.376 (1.150-1.645) | <0.001 | NA |

| Source of controls | ||||||||||||||||

| HB | 2 | 1.098 (0.852-1.415) | 0.471 | 0 | 1.209 (0.913-1.599) | 0.185 | 0 | 1.135 (0.893-1.442) | 0.302 | 0 | 1.127 (0.947-1.341) | 0.177 | 0 | 1.102 (0.972-1.250) | 0.129 | 0 |

| PB | 3 | 1.193 (1.028-1.385) | 0.02 | 49.3 | 0.988 (0.501-1.945) | 0.971 | 85.9 | 1.125 (0.815-1.552) | 0.474 | 75.3 | 0.925 (0.528-1.623) | 0.787 | 82.3 | 1.038 (0.777-1.388) | 0.8 | 84.5 |

| rs1790349 (A/G) | 3 | 1.060 (0.850-1.323) | 0.605 | 52 | 1.056 (0.793-1.407) | 0.71 | 0 | 1.043 (0.837-1.300) | 0.705 | 55.1 | 0.998 (0.754-1.319) | 0.986 | 0 | 1.048 (0.942-1.167) | 0.391 | 45.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||||||||

| Caucasian | 2 | 1.201 (1.008-1.431) | 0.04 | 0 | 1.094 (0.784-1.526) | 0.598 | 44 | 1.180 (0.998-1.396) | 0.053 | 21.2 | 1.003 (0.727-1.386) | 0.983 | 30.6 | 1.110 (0.972-1.266) | 0.122 | 37.4 |

| Mixed | 1 | 0.920 (0.739-1.145) | 0.453 | NA | 0.957 (0.545-1.677) | 0.877 | NA | 0.923 (0.748-1.140) | 0.458 | NA | 0.980 (0.561-1.712) | 0.944 | NA | 0.940 (0.783-1.128) | 0.505 | NA |

Note: OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval. The results are in bold if P < 0.05.

In stratified analyses, rs12785878 T/G SNP was quantitatively analyzed in “ethnicity,” “type of carcinoma,” and “source of control group” subgroups, and the rs1790349 A/G SNP was analyzed in the “ethnicity” subgroup. For rs12785878 T/G SNP, correlations calculated under the heterozygote genotype model (TG vs. TT) were observed in “Caucasian population” and “PB” subgroups (Caucasian: OR (95%CI) = 1.178 (1.021-1.358), P = 0.024; PB: OR (95%CI) = 1.193 (1.028-1.385), P = 0.020, Table 3). For rs1790349 A/G SNP, association was only manifested in the “Caucasian population” subgroup (AG vs. AA: OR (95%CI) = 1.201 (1.008-1.431), P = 0.040, Table 3).

3.2.2. Three Polymorphisms in CYP2R1 Gene

Nine eligible publications were involved to estimate the association intensity of CYP2R1 polymorphisms and overall carcinoma risk. Nevertheless, none of these SNPs manifest significant correlations with risk of carcinoma in any genetic models.

Then, stratified analyses of rs10741657 G/A and rs12794714 G/A SNPs were conducted based on “ethnicity,” “type of carcinoma,” and “source of control group,” on account of the presence of between-study heterogeneity. For rs12794714 G/A SNP, its allelic models had correlation with a decreased genetic predisposition to colorectal cancer (A vs. G: OR (95%CI) = 0.866 (0.753-0.997), P = 0.046, Table 3). Correlations could not be elucidated among any of the stratified analyses of rs10741657 G/A SNP.

3.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was adopted to assess the impact of each study on summarized findings, by means of calculating the OR (95% CI) before and after deleting each article from the pooled analysis. For rs12785878 T/G SNP, it made no sense after the removal of two articles (Isabel S. Carvalho 2019, Tess V. Clendenen 2015) individually (Supplementary Table S1).

3.4. Publication Bias

Potential publication bias was evaluated for all covered publications by means of two test methods mentioned above. The publication bias was found in rs12794714 G/A SNP under the recessive model, for P < 0.1 in both tests, which might be because of the deficient publications with negative results or the defective methodological design for small-scale studies (Table 4).

Table 4.

The results of Begg's and Egger's test for the publication bias.

| Comparison type | Begg's test | Egger's test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z value | P value | t value | P value | |

| CYP2R1 rs10741657 (G/A) | ||||

| Heterozygote vs. homozygote wild | 0 | 1 | -0.7 | 0.521 |

| Homozygote variant vs. homozygote wild | 0.38 | 0.707 | -0.73 | 0.503 |

| Dominant model | 0 | 1 | -0.53 | 0.627 |

| Recessive model | 0 | 1 | -0.29 | 0.787 |

| Allelic model | 0.75 | 0.452 | -0.38 | 0.722 |

| CYP2R1 rs12794714 (G/A) | ||||

| Heterozygote vs. homozygote wild | 0.34 | 0.734 | 0.21 | 0.851 |

| Homozygote variant vs. homozygote wild | 1.02 | 0.308 | -2.84 | 0.105 |

| Dominant model | 0.34 | 0.734 | -0.01 | 0.994 |

| Recessive model | 1.7 | 0.089 | -9.45 | 0.011 |

| Allelic model | 0.34 | 0.734 | -1.12 | 0.38 |

| CYP2R1 rs2060793 (G/A) | ||||

| Heterozygote vs. homozygote wild | 0 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Homozygote variant vs. homozygote wild | 0 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Dominant model | 0 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Recessive model | 0 | 1 | NA | NA |

| Allelic model | 0 | 1 | NA | NA |

| DHCR7 rs12785878 (T/G) | ||||

| Heterozygote vs. homozygote wild | 0.24 | 0.806 | -1.64 | 0.2 |

| Homozygote variant vs. homozygote wild | -0.24 | 1 | -1.76 | 0.177 |

| Dominant model | -0.24 | 1 | -1.74 | 0.18 |

| Recessive model | 0.24 | 0.806 | -1.15 | 0.332 |

| Allelic model | 0.24 | 0.806 | -1.56 | 0.217 |

| DHCR7 rs1790349 (A/G) | ||||

| Heterozygote vs. homozygote wild | 0 | 1 | 0.18 | 0.884 |

| Homozygote variant vs. homozygote wild | 0 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.92 |

| Dominant model | 0 | 1 | -0.44 | 0.737 |

| Recessive model | 0 | 1 | -2.34 | 0.257 |

| Allelic model | 1.04 | 0.296 | -0.9 | 0.532 |

Note: the results are in bold if P < 0.1.

3.5. FPRP Analyses

Eventually, we assessed the FPRP for our significant findings. For studies of uncommon neoplasm or common tumors with small sample size, the FRPR value less than 0.5 would make a massive improvement over previous practice, based on the professional guide of FPRP calculation. Since the present study is the first meta-analysis to estimate the association between DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs and cancer risk, we consider 0.5 as the FPRP threshold. The FPRP values of rs12785878 SNP (prior probability 0.25/0.1) were less than 0.5, and FPRP values of rs1790349 and rs12794714 SNPs were also less than 0.5 (prior probability 0.25), suggesting these significant associations are deserving of attention (Table 5).

Table 5.

False-positive report probability values for correlations between genotype frequency of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 and cancer risk.

| Genotype | OR (95% CI) | P value | Statistical powera | Prior probabilityb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | ||||

| rs12785878 (T/G) | ||||||||

| GT vs. TT (overall) | 1.168 (1.027-1.328) | 0.018 | 0.312 | 0.235 | 0.390 | 0.853 | 0.983 | 0.998 |

| GT vs. TT (Caucasian) | 1.178 (1.021-1.358) | 0.024 | 0.271 | 0.321 | 0.496 | 0.899 | 0.989 | 0.999 |

| GT vs. TT (PB) | 1.193 (1.028-1.385) | 0.02 | 0.264 | 0.288 | 0.457 | 0.885 | 0.986 | 0.999 |

| rs1790349 (A/G) | ||||||||

| GA vs. AA (Caucasian) | 1.201 (1.008-1.431) | 0.04 | 0.290 | 0.424 | 0.605 | 0.933 | 0.993 | 0.999 |

| rs12794714 (G/A) | ||||||||

| AA vs. GG (CRC) | 0.866 (0.753-0.997) | 0.046 | 0.367 | 0.401 | 0.582 | 0.927 | 0.992 | 0.999 |

Note: CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; astatistical power was computed using the sample size of case and control, OR, and P values; bthe false-positive report probability is in italics if the value < 0.5.

4. Discussion

In the present article, a comprehensive review was performed for the correlation of SNPs in DHCR7 and CYP2R1 genes with overall cancer risk. And a meta-analysis was conducted for five prevalent SNPs (DHCR7: rs12785878 T/G and rs1790349 A/G; CYP2R1: rs10741657 G/A, rs12794714 G/A, and rs2060793 G/A) for the first time. Our findings showed that rs12785878, rs1790349, and rs12794714 SNPs were related to cancer susceptibility in the whole population or in some subgroups, which means they might participate in cancerogenesis. No associations were discovered in other polymorphisms.

4.1. Polymorphisms in DHCR7

DHCR7 encodes an enzyme 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase which converts 7-dehydrocholesterol into cholesterol. This enzyme is a critical regulatory switch between vitamin D3 and cholesterol, for both biosynthesis processes require 7-dehydrocholesterol as substrate [26]. Moreover, DHCR7 has been assumed to be a correlated gene for vitamin D concentration and carcinoma risk [1].

Regarding rs12785878 T/G, it has been illustrated to be a 25(OH) D concentration-related SNP [1]. We found significant correlations between rs12785878 SNP and cancer susceptibility in the whole population, Caucasian subgroup, and population-based subgroup. rs12785878 SNP is located 8000 bases upstream from 5 prime UTR region of DHCR7, and it is still unclear whether it has an impact on gene expression or has a linkage disequilibrium with some other functional SNPs. The present meta-analysis of rs12785878 SNP encompasses 5 case-control studies. Only one of the five studies, however, was in accordance with our consequence. For the rs1790349 A/G SNP, it was computed to be associated with cancer risk in the Caucasian subgroup under heterozygote genotype. The rs1790349 SNP is located in the intergenic region near DHCR7 and has also been identified to be a 25(OH) D concentration-associated SNP in genome-wide association study [16, 27, 28]. Our analysis of rs1790349 SNP involves only 2 case-control studies, so further expansion of sample volume is needed.

4.2. Polymorphisms in CYP2R1

CYP2R1, as a vital important 25-hydroxylase, metabolizes vitamin D to 25(OH) D in the liver [29]. The genetic variations in CYP2R1 were correlated with the impaired activity of 25-hydroxylases, which influence the serum 25(OH) D level [30]. Association of serum 25(OH) D level with cancer susceptibility has been revealed in breast cancer [20], gastric cancer [31], thyroid cancer [32], prostate cancer [33], colorectal cancer [34], and so on. Thus, accumulating researchers were concerned with the correlation between CYP2R1 SNPs and cancer susceptibility.

For rs12794714 (G/A) SNP, we analyzed a significant relationship between A allele-rs12794714 SNP and decreased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC). Located in exon 1 region of CYP2R1, rs12794714 G/A SNP may function as an exon splicing enhancer (ESE)/exon splicing silencer (ESS) to impact gene expression, whereas it is a synonymous variant (https://snpinfo.niehs.nih.gov/). The A allele-rs12794714 SNP has been illustrated to be associated with higher serum 25-hydroxyviatamin D concentrations [16]; thus, it may reduce the cancer risk. Thus far, the protective effect of rs12794714 has only been demonstrated in CRC. Further studies remain desired concerning rs12794714 and cancer.

4.3. Limitations and Conclusions

It ought to be mentioned that the present study has several limitations. First and foremost, association studies of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 polymorphisms with cancer predisposition remain limited. Further researches are demanded for updated meta-analyses. Moreover, several items without accessible original records were removed from ultimate analysis, which might cause publication bias.

Overall, we comprehensively assessed the correlation of DHCR7 and CYP2R1 SNPs with carcinoma risk. Additionally, a meta-analysis was conducted based on all accessible data for five polymorphisms. The consequence demonstrated that 3 (re12794714, rs12785878, and rs1790349) of the 5 SNPs were associated with cancer risk in whole population or in some subgroups, indicating that they might be feasible biomarkers for cancer susceptibility.

Abbreviations

- SNP:

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- GWAS:

Genome-wide association studies

- ORs:

Odds ratios

- CI:

Confidence intervals

- HWE:

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium

- FPRP:

False-positive report probability

- ESE:

Exon splicing enhancer

- ESS:

Exon splicing silencer.

Data Availability

The authors declare that all relevant data are presented within the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Aiping Wang conceived and designed the study. Jing Wen and Lia Li were responsible for the data extraction. Jing Wen and Xinyuan Liang were responsible for the quality assessment. Jing Wen and Aiping Wang wrote the manuscript, and Aiping Wang revised the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: ORs (95% CIs) of sensitivity analysis.

References

- 1.Jiang X., O’Reilly P. F., Aschard H., et al. Genome-wide association study in 79,366 European-ancestry individuals informs the genetic architecture of 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):p. 260. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02662-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martineau A. R., Jolliffe D. A., Hooper R. L., et al. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory tract infections: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ. 2017;356, article i6583 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pilz S., Verheyen N., Grubler M. R., Tomaschitz A., Marz W. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease prevention. Nature Reviews. Cardiology. 2016;13(7):404–417. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2016.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berardi S., Giardullo L., Corrado A., Cantatore F. P. Vitamin D and connective tissue diseases. Inflammation Research. 2020;69(5):453–462. doi: 10.1007/s00011-020-01337-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes de Abreu D. A., Eyles D., Feron F. Vitamin D, a neuro-immunomodulator: implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S265–S277. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu X., Hu W., Lu L., et al. Repurposing vitamin D for treatment of human malignancies via targeting tumor microenvironment. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2019;9(2):203–219. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Z., Zhang Y., Li H., et al. Vitamin D promotes the cisplatin sensitivity of oral squamous cell carcinoma by inhibiting LCN2-modulated NF-κB pathway activation through RPS3. Cell Death & Disease. 2019;10(12):p. 936. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song D., Deng Y., Liu K., et al. Vitamin D intake, blood vitamin D levels, and the risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging (Albany NY) 2019;11(24):12708–12732. doi: 10.18632/aging.102597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmoudi T., Karimi K., Arkani M., et al. Lack of associations between vitamin D metabolism-related gene variants and risk of colorectal cancer. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention: APJCP. 2014;15(2):957–961. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.2.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shui I. M., Mucci L. A., Kraft P., et al. Vitamin D-related genetic variation, plasma vitamin D, and risk of lethal prostate cancer: a prospective nested case-control study. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2012;104(9):690–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson L. N., Cotterchio M., Knight J. A., Borgida A., Gallinger S., Cleary S. P. Genetic variants in vitamin d pathway genes and risk of pancreas cancer; results from a population-based case-control study in Ontario, Canada. PloS one. 2013;8(6, article e66768) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carvalho I. S., Goncalves C. I., Almeida J. T., et al. Association of vitamin D pathway genetic variation and thyroid cancer. Genes. 2019;10(8):p. 572. doi: 10.3390/genes10080572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barooah P., Saikia S., Bharadwaj R., et al. Role of VDR, GC, and CYP2R1 polymorphisms in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Genetic Testing and Molecular Biomarkers. 2019;23(5):325–331. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2018.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dovnik A., Fokter Dovnik N. Vitamin D and ovarian cancer: systematic review of the literature with a focus on molecular mechanisms. Cell. 2020;9(2):p. 335. doi: 10.3390/cells9020335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y., Fang F., Tang J., et al. Association between vitamin D supplementation and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;366:p. l4673. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang T. J., Zhang F., Richards J. B., et al. Common genetic determinants of vitamin D insufficiency: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):180–188. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60588-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afshan F. U., Masood A., Nissar B., et al. Promoter hypermethylation regulates vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression in colorectal cancer-a study from Kashmir valley. Cancer Genetics. 2021;252-253:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gnagnarella P., Raimondi S., Aristarco V., et al. Ethnicity as modifier of risk for vitamin D receptors polymorphisms: comprehensive meta-analysis of all cancer sites. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2021;158:p. 103202. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.103202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latacz M., Snarska J., Kostyra E., Fiedorowicz E., Savelkoul H. F., Grzybowski R. Cieslinska A: Single nucleotide polymorphisms in 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-alpha-hydroxylase (CYP27B1) gene: the risk of malignant tumors and other chronic diseases. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):p. 801. doi: 10.3390/nu12030801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien K. M., Sandler D. P., Kinyamu H. K., Taylor J. A., Weinberg C. R. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in vitamin D-related genes may modify vitamin D-breast cancer associations. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2017;26(12):1761–1771. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Voutsadakis I. A. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) and metabolizing enzymes CYP27B1 and CYP24A1 in breast cancer. Molecular Biology Reports. 2020;47(12):9821–9830. doi: 10.1007/s11033-020-05780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arem H., Yu K., Xiong X., et al. Vitamin D metabolic pathway genes and pancreatic cancer risk. PLoS One. 2015;10(3, article e0117574) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Torre G., Chiaradia G., Gianfagna F., Laurentis A., Boccia S., Ricciardi W. Quality assessment in meta-analysis. Italian Journal of Public Health. 2006;3:44–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lv Z., Xu Q., Yuan Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association between long non- coding RNA polymorphisms and cancer risk. Mutation Research. 2017;771:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wacholder S., Chanock S., Garcia-Closas M., El Ghormli L., Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2004;96(6):434–442. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strawbridge R. J., Deleskog A., McLeod O., et al. A serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration-associated genetic variant in DHCR7 interacts with type 2 diabetes status to influence subclinical atherosclerosis (measured by carotid intima-media thickness) Diabetologia. 2014;57(6):1159–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3215-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu L., Sheng H., Li H., et al. Associations between common variants in GC and DHCR7/NADSYN1 and vitamin D concentration in Chinese Hans. Human Genetics. 2012;131(3):505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-1099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahn J., Yu K., Stolzenberg-Solomon R., et al. Genome-wide association study of circulating vitamin D levels. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19(13):2739–2745. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunkar S., Neeharika D. CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 genes: an in silico approach to identify the deleterious mutations, impact on structure and their differential expression in disease conditions. Genomics. 2020;112(5):3677–3686. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2020.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thacher T. D., Fischer P. R., Singh R. J., Roizen J., Levine M. A. CYP2R1 mutations impair generation of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and cause an atypical form of vitamin D deficiency. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2015;100(7):E1005–E1013. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak J. H., Paik J. K. Vitamin D status and gastric cancer: a cross-sectional study in Koreans. Nutrients. 2020;12(7):p. 2004. doi: 10.3390/nu12072004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu M. J., Niu Q. S., Wu H. B., et al. Association of thyroid cancer risk with plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and vitamin D binding protein: a case-control study in China. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 2020;43(6):799–808. doi: 10.1007/s40618-019-01167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao J., Wei W., Wang G., Zhou H., Fu Y., Liu N. Circulating vitamin D concentration and risk of prostate cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 2018;Volume 14:95–104. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S149325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang L., Zou H., Zhao Y., et al. Association between blood circulating vitamin D and colorectal cancer risk in Asian countries: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12, article e030513) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang J., Wang H., Ji A., et al. Vitamin D signaling pathways confer the susceptibility of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a northern Chinese population. Nutrition and Cancer. 2017;69(4):593–600. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2017.1299873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mondul A. M., Shui I. M., Yu K., et al. Vitamin D-associated genetic variation and risk of breast cancer in the breast and prostate cancer cohort consortium (BPC3) Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2015;24(3):627–630. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clendenen T. V., Ge W., Koenig K. L., et al. Genetic polymorphisms in vitamin D metabolism and signaling genes and risk of breast cancer: a nested case-control study. PLoS One. 2015;10(10, article e0140478) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pibiri F., Kittles R. A., Sandler R. S., et al. Genetic variation in vitamin D-related genes and risk of colorectal cancer in African Americans. Cancer Causes & Control. 2014;25(5):561–570. doi: 10.1007/s10552-014-0361-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang W., Ingles S. A., Torres-Mejía G., et al. Genetic variants and non-genetic factors predict circulating vitamin D levels in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: the Breast Cancer Health Disparities Study. International Journal of Molecular Epidemiology and Genetics. 2014;5(1):31–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lange C. M., Miki D., Ochi H., et al. Genetic analyses reveal a role for vitamin D insufficiency in HCV-associated hepatocellular carcinoma development. PLoS One. 2013;8(5, article e64053) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mondul A. M., Shui I. M., Yu K., et al. Genetic variation in the vitamin d pathway in relation to risk of prostate cancer--results from the breast and prostate cancer cohort consortium. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2013;22(4):688–696. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0007-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penna-Martinez M., Ramos-Lopez E., Stern J., et al. Impaired vitamin D activation and association with CYP24A1 haplotypes in differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid. 2012;22(7):709–716. doi: 10.1089/thy.2011.0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: ORs (95% CIs) of sensitivity analysis.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all relevant data are presented within the paper.