Abstract

Purpose:

Pediatric palliative care (PC) is an evolving field and involves a comprehensive approach to care of children with cancer. The goal of this paper was to explore how pediatric oncologists define, interpret and practice pediatric palliative care in their clinical settings.

Methods:

The study used the Grounded Theory approach to data collection and analysis. Twenty-one pediatric oncologists from six pediatric cancer centers across Israel were interviewed. Data was analyzed using line-by line coding.

Results:

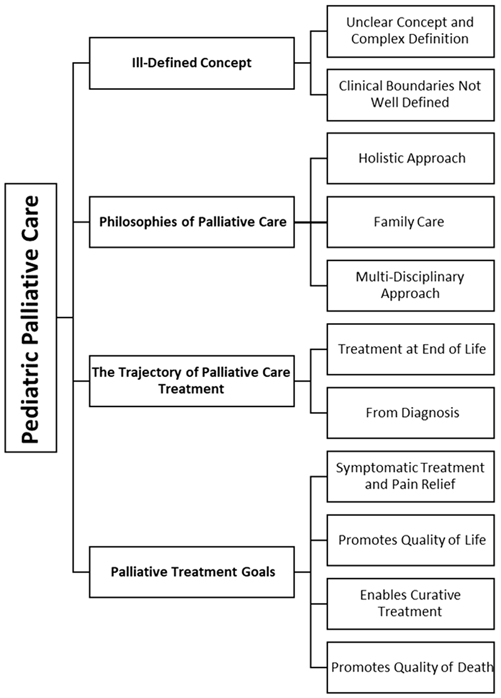

The analysis resulted in a four-tiered conceptual model. This model included the following categories: 1) Ill-defined concept; 2) Philosophies of palliative care; 3) Trajectory of palliative care; and 4) Palliative care treatment goals.

Conclusion:

The findings illustrate the current conceptualizations of pediatric palliative care among the pediatric oncology community in Israel. The conceptual model documents their understanding of pediatric palliative care as philosophical approach and the challenges they face in differentiating between palliative care and standard pediatric oncology care. Pediatric palliative care is a highly needed and valued sub-specialty. The findings from this study highlight the importance for its continued development in Israel, as it can reduce the suffering of children and their families. Concurrently, pediatric oncologists need to have more resources and access to explicit knowledge of the conceptual and practical aspects of both primary and specialized pediatric palliative care.

Keywords: Palliative care, Pediatric oncology, Oncology, Cancer, Qualitative Research

Introduction

Pediatric Palliative Care (PC) is defined as the complete care of the child's body, mind, and spirit as well as providing support for families of children suffering from serious illnesses [1]. The ideal model recommends that pediatric PC should begin when illness is first diagnosed and be provided throughout the course of the child’s illness, however, in practice, this does often happen [2]. Since the World Health Organization (WHO) defined pediatric PC nearly two decades ago and called for its inclusion into pediatric oncology care, the data has shown that palliative care and pediatric PC teams can improve the quality of life of children and their families, and reduce physical suffering caused by oncological illness [1, 3]. Evidence exists that PC can also ease mental distress in children and promote better decision-making processes for parents [4-7]. On the organizational level, PC services can lower costs for the healthcare system by reducing the need for hospital-based care [8] and has been associated with a reduction in use of intensive care services [9-11].

Historically, the development of pediatric palliative care has been given lower priority than adult palliative care [11]. While there are similarities between pediatric and adult care, there are several important differences, including age-related communication issues (i.e. children’s understanding of illness, death, consent etc.); and biological issues such as the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of medicines, developmental challenges in children etc. [12, 13].

Barriers to pediatric PC exist even where trained specialists are available. These barriers can include healthcare professionals potential reluctance to integrate into care [14, 15]. For example, in a recent study, "the main perceived barrier to palliative care subspecialist consultation was oncology providers’ perceptions that the oncologist was already providing palliative care" [2 (p6)]. Another barrier has to do with unclear professional boundaries. For example, a Dutch study on this topic identified the need for a clearer definition of the responsibilities, obligations, and requirements of the pediatric PC team [14]. Though this perception and ambiguity creates a barrier for integration of pediatric PC specialists, they also represent the evolution of the concept of PC as a multidimensional field that includes both primary care administered by healthcare professionals, and specialty PC [3, 16]. Another known barrier is that medical oncologists associate PC with end of life care [17]. In previous studies, pediatric oncologists described the goals of PC as inconsistent with cure, an alternative to cancer therapy, and appropriate only when recovery is no longer the goal [18-21].

Pediatric palliative care in Israel

In Israel, PC and hospice services are covered by Israel’s National Health Insurance and are considered a basic human right [22, 23]. In 2009, the Director General of Israel’s Ministry of Health published a policy statement describing standards for the development and provision of palliative care services for hospitals and healthcare plans [22]. That same year, the first training programs for PC nurse specialists were offered [24], and four years later (2013), PC was officially recognized in Israel as a medical specialty [25]. In 2016, a national palliative care program was launched as part of the campaign to make palliative care available to all citizens [22-24, 26].

In Israel, palliative care for children is less developed than PC for adults [27]. In 2018, there were only 3 pediatric PC doctors and 2 pediatric PC trained nurse practitioners across 6 major pediatric oncology centers [25]. Only one pediatric PC unit exists that integrates PC from diagnosis, and provides hospice care dedicated to pediatric oncology [28]. Pediatric PC in Israel has been described by professionals in the field as: "uncomprehensive, fragmented geographically, understaffed, and underfunded." [25 (p.5)]. The vast majority of cancer centers for children in Israel have at most one physician with formal PC training. As a result, primary oncologists are generally responsible for most patient care throughout the illness trajectory, including at end of life. This is important as more than 90% of children are hospitalized during the last six months of their lives [29], and approximately 70%-90% of children die in the hospital in Israel [29, 30]. As pediatric oncologists are the primary providers of PC, and as the concept of pediatric PC is continuing to evolve worldwide [20, 31], there is an urgent need to better understand how pediatric oncologists perceive this field. Their perception may have a direct effect on the care that children who are coping with life-threatening diseases receive. This study is part of a larger project exploring barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric PC in Israel [32, 33]. The objective for this study was to explore how Israeli pediatric oncologists perceive, define, and practice pediatric palliative care in their clinical care.

Methods

Study design and participants:

Research ethics boards (REB) approvals were obtained from all participating institutions prior to launching the study. The Grounded Theory method was utilized [34, 35]. Our sample consisted of 21 pediatric oncologists. The participants were recruited between November 2017 and January 2019 from the existing six pediatric-oncology medical centers in Israel. Using a purposive sampling technique, we interviewed oncologists at various stages of their careers and personal and professional backgrounds.

Procedure:

After REB approvals were obtained, co-investigators at each center sent out information about the study by email to all pediatric oncological in the centers. There are seventy-nine pediatric oncologists working at these 6 centers. Twenty-one people responded to these emails which represents a 25% response rate. To encourage participation and maintain anonymity, participants were asked to directly contact the researcher (who is not a pediatric oncologist, and who did not know the participants prior to beginning the study) if they were interested in hearing more about the research. All those who contacted the researcher agreed to participate after hearing more about the research. Interviews were conducted by a trained health psychologist with over 10 years of experience in psycho-oncology. The interviews were scheduled with the oncologists at a place and time convenient to them. Participants signed a consent form and the interviews were audio-recorded. The interviews lasted between 35 minutes to 1 hour and 40 minutes. The researcher used a semi-structured interview guide. Questions focused on the oncologist's definition and perception of PC and the available PC services for children and their families at their centers. The interviews were then transcribed with all personal information removed from the transcripts.

Data analysis:

Data was collected and analyzed concurrently. Inductive analysis was used, and the participants’ narratives were coded line-by-line to produce codes and categories. Constant comparison was utilized to understand the relationships between the emerging categories and themes. We compared category to category, theme to theme and code to code throughout the process of data collection and analysis. During data collection and throughout the analysis, team meetings with the study PI and the researcher, were held on a regular basis. Team meetings with the co-investigators were held periodically throughout the process of data collection and analysis to discuss emerging findings and any issues requiring clarification. We incorporated peer debriefing by national and international expert researchers and clinicians in the fields of pediatric oncology throughout the process of analysis. Once the analysis stopped producing new codes the team determined that we had reached data saturation and that no new codes or themes were emerging from the data, at which point, we stopped conducting new interviews. NVivo 12 software was used for storing, coding and organizing the data.

Findings

The analysis resulted in a four-tiered conceptual model (see Fig. 1). The four tiers of this model includes the following findings: 1) An Ill-Defined Concept, with the themes of unclear and complex definition and clinical boundaries ill-defined; 2) Philosophes of Palliative Care, with the themes of holistic approach, family care, and multi-disciplinary approach; 3) Trajectory of Palliative Care, with the themes of treatment at end of life and from diagnosis; 4) Palliative Care Treatment Goals, which included the themes of symptomatic treatment and pain relief, promoting quality of life, enabling curative treatment, and promoting quality of death. Each of these themes and sub-themes are presented in more detail below with supporting quotations.

Fig 1. Understanding of pediatric palliative care conceptual model: Tiers and themes.

*pptx graphic. Black and white graphic.

1. An Ill-Defined Concept

Unclear and complex definition:

Oncologists noted that PC is a concept that tends to be unclear, complex, and hard to define. When trying to define it during the interviews, some gave contradictory definitions, and noted that the verbal definitions are not always aligned with their clinical practice. On this, one oncologist explained:

There are patients who we are definitely trying to save, but they need a lot of supportive care for all the symptoms. Is that palliative care? Yes. By definition yes. But we don't consider it palliative care.

Clinical boundaries ill-defined:

The overlap between pediatric oncology, supportive care, and palliative care emerged numerous times and demonstrated the difficulty with pediatric PC conceptualization. One oncologist reported: "Palliation for us is part of the treatment, we don’t call it palliation. We don’t separate it. It is an integral part, 'the patients get what they need'”.

2. Philosophies of Palliative Care

Holistic approach:

Pediatric PC was described as a philosophy of care and a theoretical, abstract concept that inspires a specific orientation of care. It was presented as a holistic approach that considers the entire spectrum of child and family needs, also referred to as 'treating the patient and not the disease'. One oncologist noted:

The benefit is to the patients, their pain, technical difficulties, and ability to deal with everything, from how to take the elevator, to how to go to school and maintain a social life.

Another oncologist similarly reported: "for me, any auxiliary treatment that is not proper chemotherapy is PC".

Family care:

Examples of PC for the family, and particularly for the parents of children with cancer, included: 1) Practical aspects related to organizing every-day life, balancing parents' careers with their child’s medical needs, and helping parents obtain the Social Security annuity to which they are entitled; 2) Emotional support for parents such as being emotionally available, showing compassion and emotional containment, and treating parents' anxiety (using designated conversations, hypnosis treatments, etc.) and distress, as well as reducing suffering and distress of other relatives, such as siblings and grandparents, and encouraging open communication as a means for emotional support; and finally, 3) Medical care for families. Oncologists described providing direct medical treatment for the caregiver as part of their understanding of pediatric PC. As one oncologist noted, "Many times, we deal with the grandmothers' heart attack. We just had a grandmother who suffered from a heart attack during the child's hospitalization … this is also palliative care in my view".

Multi-disciplinary approach:

This approach to pediatric PC is a manifestation of the holistic philosophy of PC. Many different healthcare providers and services were included under this rubric, such as 1) Physicians, pain experts, anesthesiologists, surgeons, and psychiatrists; 2) Nurses, including those who specialize in palliative care and pain management, coordinators, and oncological nurses in general; and 3) Other healthcare professionals such as social workers, psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, nutritionists, emotional therapists (i.e., art and music therapists), complimentary medicine personnel, clowning, and volunteer associations including national service volunteers.

3. The Trajectory of Palliative Care Treatment

Oncologists used the timeline of the illness to better explain pediatric PC. They often referred to the end-of-life (EOL) period and did so in two conflicting ways. They stated that PC should be given to a child who has no prospect of cure or is approaching end of life, but also contradicted the statement that PC should be given only at end of life.

Treatment at end of life.

In the first instance, oncologists spoke of PC as care given at the EOL. For example, one oncologist noted: “When I think of palliation, I think of it at the point in time that is associated with the end". Another explained, "Palliative treatment in my eyes is a treatment whose purpose is not cure, but to accompany a patient in a non-curable situation".

From diagnosis:

Other oncologists stated that pediatric PC should start as early as the day of diagnosis. On this, one oncologist explained:

Palliation starts on the day of diagnosis, while palliation refers to all the general needs of the child. Whether or not the child is going to die or not, there is palliation.

Other participants noted that by definition, pediatric PC should start at an early stage, but they themselves practice it only at EOL. For example, one oncologist noted:

If you take the definition I mentioned, palliative care needs to start at the beginning. In practice, our patients get palliative care at end of life when I'm convinced that no matter what I will do, the patient will not be cured.

4. Palliative Treatment Goals

Several themes emerged from the broad category of palliative treatment goals that help clarify the purpose of PC in the eyes of pediatric oncologists and describe the ways in which they provide it.

Symptomatic treatment & pain relief:

There was a consensus among pediatric oncologists that symptomatic treatment and pain relief are the primary goals of pediatric PC. To better understand what falls into this theme, we asked the participants to elaborate on current, related pediatric PC goals and services (see Table 2). Pain relief options included different medications, patches, hypnosis, radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy when they are administered for the purpose of pain relief. Examples of other symptomatic treatments included respiratory distress and suffocation, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, disabilities and decreased functioning, neurological symptoms, depression and anxiety, and long-term adverse effects such as infertility and peripheral neuropathy.

TABLE 2.

The goals of pediatric palliative care as described by Israeli pediatric oncologists

| Symptom | Professionals involved |

Pediatric PCi treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Pain treatment | Pediatric & radiation oncologists, nurses, Pediatric PC specialists, pain experts, anesthesiologists specializing in pediatrics, surgeons. |

|

| Lack of appetite, nausea, and vomiting | Pediatric oncologists, nurses, nutritionists, Pediatric PC specialists, complimentary medicine. |

|

| Low immunity and its consequences (e.g. mucositis) | Pediatric oncologists | Infection prevention:

Infection treatment:

|

| Treating respiratory distress & suffocation | Pediatric oncologists |

|

| Neurological symptoms | Radiation oncologists |

|

| Treating incurable disease | Pediatric oncologists |

|

| Disabilities and reduced functioning | Physical therapists |

|

| Depression and anxiety | Psychiatrists, nurses, psychologists, social workers, Pediatric PC specialists, art therapists, music therapists. |

|

| Long term side effects: Infertility Peripheral neuropathy General long-term consequences | Pediatric oncologists |

|

PC: Palliative Care

Promoting quality of life:

Oncologists described quality of life (QOL) as another goal of pediatric PC. Supportive services were part of the pediatric oncologists’ understanding of the broader notion of the PC approach and are considered a component of pediatric PC that impacts the QOL of children and their families. An oncologist noted:

[PC is] preserving the quality of life. Throughout the entire illness. When the outcome for a child is not totally clear … the approach aims to ease symptoms, and to preserve and improve quality of life. That is the palliative care approach.

In the context of pediatric PC, support involves compassion, care, and encouragement. When elaborating about the roles of other staff members, they spoke of nurses' care and support, psychological therapy, social workers, and art and music therapists. Other services such as in-hospital education, therapeutic clowns, national service volunteers, and other volunteer associations, were also described as part of PC services. The participants described the contributions of volunteers to the well-being and spirit of children on two levels. The first is practical and includes material contributions such as donation of wigs and hospital equipment like wheelchairs. The second is the emotional support provided by creating a social environment for sick children and organizing different celebrations for them.

Enabling curative treatment:

Another goal described for pediatric PC was enabling treatment and cure by reducing the suffering and pain of the children and their families. On this, one oncologist explained, “A child who is not in pain is a child who is able to cope and to heal better. And the family can also cope with what they are going through in a better way.”

Promoting better quality of death:

Finally, providing better quality of death was described as a goal of pediatric PC. One oncologist explained: "Palliative care is a treatment that by definition should relieve the child’s suffering at the end of life". Unfortunately, this was also described as a goal that is still unachievable for some children, as pediatric oncologists spoke of children dying in pain and suffering. On this another oncologist remarked:

The child was lying there all night long and nobody started him on a drip. And he died in agony because none of us had the… I don't know how to say it. The sight to say: ‘guys, it’s over, start the drip instead’.

Discussion

This study explored pediatric oncologists’ conceptualization of pediatric palliative care. The findings resulted in a four-tiered model. As specialized pediatric PC services are rare in Israel [25] this mapping represents primary PC given by healthcare professionals in pediatric oncology. The results suggest that the WHO holistic notion of palliative care for children as treatment of the child's body, mind and spirit as a whole [1] is embedded in the perception of Israeli pediatric oncologists practice of palliative care. In some countries, including Germany and Italy, strong pressure has been exerted to define palliative medicine as a sub-discipline of pain therapy and to focus research almost entirely on pharmacological pain treatment and control of symptoms [36]. This significantly differs from the holistic approach towards palliative care [36].

However, as PC is a holistic domain, it is harder to define and set professional boundaries between primary and specialized pediatric PC, and perhaps even to distinguish between regular pediatric-oncological care and primary PC. This may explain some of the difficulties pediatric oncologists face when they must share their treatment domains with PC, a relatively newly established sub-specialty. This ambiguity is enhanced when considering the lack of PC training for pediatric oncologists [37] and corresponds with literature from other countries indicating that pediatric oncologists lack knowledge of PC [14] and receive little, or no, training [38, 39].

Although few studies are available on the perceptions of pediatric oncology providers in Israel, our results correspond with publications from other countries. In the United states, multi-professional healthcare teams working in pediatric oncologists were asked to define pediatric PC. Four themes emerged: EOL care, quality of life (i.e., managing symptoms, comprehensive care, or treating patients as a whole to improve quality of life), psychosocial therapy, and spiritual care [20]. The first three of these findings overlap with our results. In both studies, pediatric oncologists spoke of the difficulty in distinguishing between specialized pediatric PC and routine pediatric oncological work, and frequently mentioned end-of-life care as a point of reference for pediatric PC definition and evolvement [20].

An earlier study in the United States showed that pediatric oncologists have concerns about overlapping roles between the primary oncology physicians and the pediatric PC specialists, a concern based on oncologists' perception that they are already providing palliative care [40]. Similarly, a study in the Netherlands reported that pediatric PC teams’ tasks and responsibilities are vaguely understood by pediatric oncologists [14]. Our data suggests that the ambiguous definition of pediatric PC and the overlap of tasks between primary pediatric PC and specialized pediatric PC creates a level of uncertainty. This is added to the other stresses and uncertainty associated with care for pediatric patients with advanced-stage cancer, including prognosis, individual needs, communication, relationships, interactions between colleagues and inter-organizational issues [41].

The challenges of integrating PC and pediatric oncology care exceed addressing the needs of patients, availability of services, and professional guidelines [19]. They include significant variation at the provider level in the use of the palliative care sub-specialty for patients with cancer, regardless of their age [42]. A recent literature review of pediatric providers in the United States reported that barriers for pediatric PC on the provider level include insufficient knowledge about PC; a view of PC as equivalent to hospice or EOL care; discomfort with talking about death; and trying to foster a “culture of hope” in pediatric medical settings [15]. These are challenges that still need to be overcome, as data supports the availability of pediatric PC teams and pediatric PC training programs can reduce children’s suffering, pain, and anxiety, improve other symptoms, significantly reduce hospitalization time, reduce the number of deaths in the pediatric intensive care unit, and improve advanced care planning [43, 44]. In Israel, pediatric palliative specialist teams are rare. To date, only one hospital has a pediatric PC unit that integrates PC from diagnosis and provides inpatient hospice care. Nonetheless, Israel has developed a health care policy regarding PC and is working towards integration of PC for children and adults across the country [23, 25]. There are also many other supporting services in Israel available to children and their families, including but not limited to advanced pain treatments, psychosocial care, physiotherapy, music and art therapy [30], along with a broad exposure to world-leading care and services. These places the Israeli healthcare system in general, and pediatric oncologists in particular in a unique position for developing a specialized pediatric PC program that can overcome some of the barriers to integration of pediatric PC that appear all over the world [3, 15, 17, 45].

The need for a clearer practical definition of the holistic term pediatric PC that arose from the knowledge and practices of participants in this study has important implications. It reflects the universal challenge of defining pediatric PC [44], and the lack of service standardization [39] that can create a barrier for integration of pediatric PC specialists. A clear definition may also help resolve challenges related to policies and payment, and encourage allocation of resources [15, 46]. The Israeli pediatric oncologists’ model of pediatric PC conceptualization that emerged from this data may contribute to this process. Finally, there is a need to develop programs suited for both generalist and specialists, as both types of professionals can and should provide palliative care when needed [16, 46].

Limitations:

The goal of this qualitative study was to explore how Israeli pediatric oncologists perceive, define, and practice pediatric palliative care in their clinical care. The purpose of qualitative research is to gain an in-depth understanding of participants experiences. Our response rate represents 20% of all licensed pediatric oncologists in Israel, and as such, is a good representation of the field. Future studies wishing to explore the broader generalizability of these findings might consider including a larger number of pediatric oncologists using quantitative methods.

Conclusions:

Pediatric PC is a highly needed and valued sub-specialty. The findings from this study highlight the importance for its continued development in Israel, as it can reduce the suffering of children and their families. Concurrently, pediatric oncologists need to have more resources and access to explicit knowledge of the conceptual and practical aspects of both primary pediatric PC and specialized pediatric PC.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 12 | 57 |

| Female | 9 | 43 |

| Age | ||

| Mean | 53 | |

| Range | 40-67 | |

| Years in Oncological Practice | ||

| Less than 5 | 4 | 19 |

| 5-10 | 7 | 33.5 |

| 11-15 | 3 | 14 |

| More than 15 | 7 | 33.5 |

| Years of Providing PC | ||

| Less than 5 | 6 | 29 |

| 5-10 | 5 | 24 |

| 11-15 | 3 | 14 |

| More than 15 | 7 | 33 |

| No. of patients seen per week in Oncology | ||

| 26-35 | 6 | 29 |

| 36-40 | 3 | 14 |

| More than 40 | 12 | 57 |

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF). Grant (No.179/17) awarded to Leeat Granek (PI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official so may therefore version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and .differ from this version

Conflict of Interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval: This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Ben-Gurion University (Date 28.07.2017/No. 1532-1).

Consent to participate: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication: Consent was obtained to write up research papers based on anonymized data.

Availability of data and material: Not applicable. The data collected in this research are of full interviews with healthcare providers. As such, data cannot be shared as it would violate participant confidentiality.

Code availability: Not applicable.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (1998) Cancer pain relief and palliative care in children. World Health Organization Press, Geneva, Switzerland [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver MS, Rosenberg AR, Tager J, et al. (2018) A Summary of Pediatric Palliative Care Team Structure and Services as Reported by Centers Caring for Children with Cancer. J Palliat Med 21:452–462. 10.1089/jpm.2017.0405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J (2017) Approaching the third decade of paediatric palliative oncology investigation: historical progress and future directions. Lancet Child Adolesc. Heal 1:56–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groh G, Borasio GD, Nickolay C, et al. (2013) Specialized pediatric palliative home care: A prospective evaluation. J Palliat Med 16:1588–1594. 10.1089/jpm.2013.0129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gans D, Kominski GF, Roby DH, et al. (2012) Better outcomes, lower costs: palliative care program reduces stress, costs of care for children with life-threatening conditions. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res 1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickens DS (2010) Comparing pediatric deaths with and without hospice support. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54:746–750. 10.1002/pbc.22413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, et al. (2011) Pediatric palliative care patients: A prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 127:1094–1101. 10.1542/peds.2010-3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tamir O, Singer Y, Shvartzman P (2007) Taking care of terminally-ill patients at home - The economic perspective revisited. Palliat Med 21:537–541. 10.1177/0269216307080822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. (2006) Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gómez-Batiste X, Tuca A, Corrales E, et al. (2006) Resource Consumption and Costs of Palliative Care Services in Spain: A Multicenter Prospective Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 31:522–532. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fassbender K, Fainsinger R, Brenneis C, et al. (2005) Utilization and costs of the introduction of system-wide palliative care in Alberta, 1993-2000. Palliat Med 19:513–520. 10.1191/0269216305pm1071oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downing J, Boucher S, Daniels A, Nkosi B (2018) Paediatric Palliative Care in Resource-Poor Countries. Children 5:27. 10.3390/children5020027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilden J, Himelstein B, Freyer D, et al. (2001) End-of-Life Care: Special Issues in Pediatric Oncology. In: Foley KM, Gelband H (eds) Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. National Academies Press (US), Washington (DC), pp 161–199 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schepers SA, et al. (2018) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a paediatric palliative care team. BMC Palliat Care 17:23. 10.1186/s12904-018-0274-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haines ER, Frost AC, Kane HL, Rokoske FS (2018) Barriers to accessing palliative care for pediatric patients with cancer: A review of the literature. Cancer 124:2278–2288. 10.1002/cncr.31265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg AR, Weaver MS, Wiener L (2018) Who is responsible for delivering palliative care to children with cancer? Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e26889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Daher M, et al. (2012) Palliative cancer care in middle eastern countries: Accomplishments and challenges. Ann Oncol 23:15–28. 10.1093/annonc/mds084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalberg T, McNinch NL, Friebert S (2018) Perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care: A national survey of pediatric oncology providers. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65:e26996. 10.1002/pbc.26996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, et al. (2014) Oncologist Factors That Influence Referrals to Subspecialty Palliative Care Clinics. J Oncol Pract 10:e37–e44. 10.1200/jop.2013.001130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuviello A, Raisanen JC, Donohue PK, et al. (2020) Defining the Boundaries of Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology. J Pain Symptom Manage. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuviello A, Boss R, Shah N, et al. (2019) Utilization of palliative care consultations in pediatric oncology phase I clinical trials. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66:e27771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentur N, Emanuel LL, Cherney N (2012) Progress in palliative care in Israel: Comparative mapping and next steps. Isr J Health Policy Res 1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of health, The Myers-JDC-Brookdale Institute, JDC-ESHEL JOINT Israel (2016) Recommendations for the national palliative care program and for end of life situations

- 24.Livneh J (2011) Development of palliative care in israel and the rising status of the clinical nurse specialist. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 33:S157–8. 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318230e22f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaulov A, Baddarni K, Cherny N, et al. (2019) “Death is inevitable – a bad death is not” report from an international workshop. Isr J Heal Policy Res 8:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bentur N, Emanuel LL, Cherney N (2012) Progress in palliative care in Israel: Comparative mapping and next steps. Isr J Health Policy Res 1:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silbermann M, Arnaout M, Sayed HAR, et al. (2012) Pediatric palliative care in the Middle East. In: Knapp C, Fowler-Kerry S, Madden V (eds) Pediatric Palliative Care: Global Perspectives. Springer, London New York, pp 127–159 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golan H, Bielorai B, Grebler D, et al. (2008) Integration of a palliative and terminal care center into a comprehensive Pediatric Oncology Department. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50:949–955. 10.1002/pbc.21476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yaniv I (2012) Pediatric Oncology Palliative Care in Israel. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 34:S32–S35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ben-Arush MW (2011) Current status of palliative care in Israel: A pediatric oncologist’s perspective. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol Suppl 1:S56–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meghani SH (2004) A concept analysis of palliative care in the United States. J Adv Nurs 46:152–161. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2003.02975.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laronne A, Granek L, Golan H, et al. (2020) Conceptualizations and definitions of pediatric palliative care by Israeli oncologists. In: Psycho-Oncology 29. pp 47–47 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laronne A, Granek L, Golan H, Feder-Bubis P (2020) The 3" C’s" in the physician-parent alliance in pediatric oncology. In: Psycho-Oncology 29. pp 98–9831483911 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Charmaz K (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Research. Sage, London [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glaser BG, Strauss AL (2017) Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge, New York [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borasio GD (2011) Translating the World Health Organization definition of palliative care into scientific practice. Palliat Support Care 9:1–2. 10.1017/S1478951510000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Israeli medical Association (2016) Pediatric hemato-oncologist internship program. https://www.ima.org.il/internesnew/viewcategory.aspx?categoryid=6943. Accessed 5 May 2020

- 38.Hilden JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, et al. (2001) Attitudes and practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: Results of the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey. J Clin Oncol 19:205–212. 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, et al. (2013) Pediatric palliative care programs in children’s hospitals: A cross-Sectional national survey. Pediatrics 132:1063–1070. 10.1542/peds.2013-1286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalberg T, Jacob-Files E, Carney PA, et al. (2013) Pediatric oncology providers perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60:1875–1881. 10.1002/pbc.24673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hill DL, Walter JK, Szymczak JE, et al. (2020) Seven Types of Uncertainty When Clinicians Care for Pediatric Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 59:86–94. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cherny NI, Catane R (2003) Attitudes of Medical Oncologists Toward Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced and Incurable Cancer: Report on a Survey by the European Society of Medical Oncology Taskforce on Palliative and Supportive Care. Cancer 98:2502–2510. 10.1002/cncr.11815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. (2008) Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: Is care changing? J Clin Oncol 26:1717–1723. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klick JC, Hauer J (2010) Pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 40:120–51. 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schepers SA, et al. (2018) Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a paediatric palliative care team. BMC Palliat Care 17:23. 10.1186/s12904-018-0274-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Himelstein BP, Hilden JM, Boldt AM, Weissman D (2004) Pediatric Palliative Care. N Engl J Med 350:1752–1762. 10.1056/NEJMra030334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]