Abstract

Researchers studying the effect of folate restriction on rodents have resorted to the use of the antibiotic succinylsulfathiazole (SST) in the folate depleted diet to induce a folate deficient status. SST has been used extensively in rodent studies since the 1940s. Its localized effect on the gut bacteria as well as its effectiveness in reducing folate producing species is well documented. The possible overlap between the pathways affected by folate depletion and SST could potentially produce a confounding variable in such studies. In our novel study, we analyzed the effect of SST on folate levels in c57Bl/6 male mice fed folate supplemented and deficient diets. We did not observe any significant difference on growth and weight gain at 21 weeks. SST did not significantly affect folate levels in the plasma, liver and colon tissues; however, it did alter energy metabolism and expression of key genes in the mTOR signaling pathway in the liver. This research sheds light on a possible confounding element when using SST to study folate depletion due to the potential overlap with multiple critical pathways such as mTOR.

Summary

The antibiotic succinylsulfathiazole (SST) is used to reduce folate producing bacteria in rodent folate depletion studies. SST can modulate critical energy and nutrient sensing pathways converging onto mTOR signaling, and potentially confounding cancer studies.

Introduction

The gut microbiome is a complex and diverse array of microorganisms that colonize the digestive system. The gut microbiome of humans and other mammals has been extensively studied due to its profound effect on the health and disease of the host. Perturbations of the gut microbiome has been linked to various disease etiologies, including: metabolic diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, autoimmune disorders, inflammation, allergies, cancer, and more1–9. The gut microbiota is responsible for producing a plethora of compounds and signaling molecules that mediate the complex interactions with its host. These compounds include: branched and short chain fatty acids (SCFA), organic acids, menaquinones (vitamin K), and some B vitamins10,11. Specifically, the ability of certain bacteria in the gut to synthetize large amounts of folates is well documented12,13. Others have shown that bacterial folate is easily absorbed and incorporated into the host folate stores in various tissues14–18. The amount of folates produced by a healthy gut flora, specifically through fermentation in the large intestine, is diet dependent. In fact, diets rich in fermentable fibers have been shown to increase folate levels and decrease homocysteine in rats, while no effect was observed with non-fermentable fiber supplemented diets19.

Other manipulations of the diet, such as the addition of antibiotics, can yield drastic changes to the gut microbiome20–23. The addition of 1% succinylsulfathiazole (SST), a long-acting sulfonamide, can produce large shifts in the composition of the gut flora and the ability to synthetize folate24,25. SST is characterized by poor absorption and localized antibacterial activity that is primarily limited to the gut26. It was used in the 1940s as a gut antiseptic to lower the bacterial load and prevent infections after gut surgeries24,27,28. Similar to other sulfonamides in its class, SST works by inhibiting bacterial folate synthesis through competitive inhibition with P-aminobenzoic acid (PABA)29. SST persists in the gut much longer than absorbable antibiotics and has no known systemic toxicities30. It is hydrolyzed slowly in the large intestines by bacterial esterases to the active form sulfathiazole26. The effect of SST on gut microbial density and folate production is documented in earlier studies24,27,28. Since then, SST has been replaced clinically by more efficacious and potent antibiotics. However, researchers have used it extensively in studies to reduce or limit the folate producing bacteria in various lab models31–34.

In our studies, we have used SST along with dietary folate depletion to study the impact of folate depletion on colon cancer initiation35. We were concerned that the use of SST to induce a folate deficient status in rodents can modulate some of the same pathways that are affected by folate depletion. In the present study, we were interested in examining the long-term effects of SST in the livers of C57BL6 mice fed folate supplemented and folate depleted diets. We analyzed the impact of SST on folate levels in the serum, colon, and liver. We were specifically interested in investigating the effect of the antibiotic on the mTOR signaling pathway, a major growth regulator that converges signals form growth factors, amino acids, glucose, stress, and energy levels, and impacts cellular growth, autophagy, and proliferation.

Materials and methods

Animals

c57Bl/6 male specific pathogen free mice were purchased from Charles Rivers at 6 weeks of age (n=3). Animals were maintained in accordance with NIH guidelines for the use and care of laboratory animals. The Animal protocol was approved by the Wayne State University Animal Investigation Committee. They were fed the standard mouse chow and water ad libitum and were maintained on a 12-hr light/dark cycle until the start of the experiment. Mice were anesthetized in a CO2 chamber and the abdominal cavity was opened for excising the colon and harvesting the liver tissue. Blood was obtained by cardiac puncture, centrifuged, and the serum separated. The harvested liver was flash frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Diets

At 4 months of age, mice were randomly assigned to 4 dietary groups and fed AIN93G-purified isoenergetic diets (Dyets, Inc., Lehigh Valley, PA)36. Diets were stored at −20°C. The control groups received either a folate adequate diet (FA) (2mg FA/kg diet for 21 weeks) or folate depleted diet (FD) (0mg FA/kg diet for 21 weeks). The experimental groups received either a folate adequate diet supplemented with 1% succinyl sulfathiazole (FA SST) (2mg FA/kg diet + 1% SST for 21 weeks) or a folate depleted diet with 1% SST (FD SST) (0mg FA/kg diet +1% SST for 21 weeks).

Folate Assay

Serum, liver, and colon mucosa were collected upon sacrifice. Folate was measured using the Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay of folic acid derivatives as described by Horne et. Al37. Briefly, growth response of lactobacillus casei to folate availability was measured at OD 600 nm. A standard curve was used to calculate folate concentrations. Folate levels are expressed as nmol/g.

Isolation of Whole cell extract

Whole cell extracts were isolated using RIPA buffer. Briefly, 50 mg of liver tissue was homogenized using RIPA buffer (1% Igepal, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% LDS, 1X PBS) combined with HALT protease inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Fisher). Whole cell extracts collected were stored at −80°C for further analysis.

Western Blot Analysis

Protein expression analysis was performed using the V3 western blot system from Bio-Rad. 50 μg of protein was loaded onto criterion TGX stain free precast Gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gels were imaged using chemidoc XRS+ system then wet transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes and gels were imaged to verify complete transfer. Manufacturer recommended dilutions of anti-sera developed against various anti-bodies (cell signaling) were used to detect proteins of interest followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). The bands were visualized and quantified using chemidoc XRS+ imager and Image lab software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) after incubation in SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Data are expressed as adjusted band volume normalized to total lane proteins as described in Taylor et al.38. Phosphorylated forms of proteins were normalized to total and expressed as ratio. Full western blot images are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Gene expression profiling

The mRNA expression levels of various genes were quantified using a real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted from liver tissue using RNeasy extraction kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). First strand cDNA was synthesized from 1μg RNA using random primers and poly-A primers. Expression of each gene was quantified using real time PCR with specific primers for the gene. The gene transcript was normalized to GAPDH. External standards for all genes were prepared by subcloning the amplicons, synthesized using the specific primers into PGEM-T easy vector. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 2.

ATP Assay

ADP/ATP ratio was assessed using a luciferase based bioluminescent assay kit (Abcam). Briefly, 10 mg of liver tissue was quickly homogenized with nucleotide releasing buffer. Using a microplate reader, the homogenate was assayed per protocol to determine ATP induced luminescence. Then ADP converting enzyme was added and luminescence was further determined. Data are expressed at ADP/ATP ratio.

NAD/NADH Assay

NAD+/NADH was assayed using a fluorometric microplate reader assay (Abcam). 20 mg of liver tissue was homogenized in provided lysis buffer and supernatant was collected. Total NAD, NAD+ and NADH were assayed per protocol. Fluorescence was measured at EX/EM=540/590 nm. Data are expressed at NAD+ to NADH ratio.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance between means was determined using one way and 2-way ANOVA followed by post tukey test wherever appropriate. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Antibiotic in the Diet and the Effect on Weight gain, Serum, Liver and Colon Folate Levels

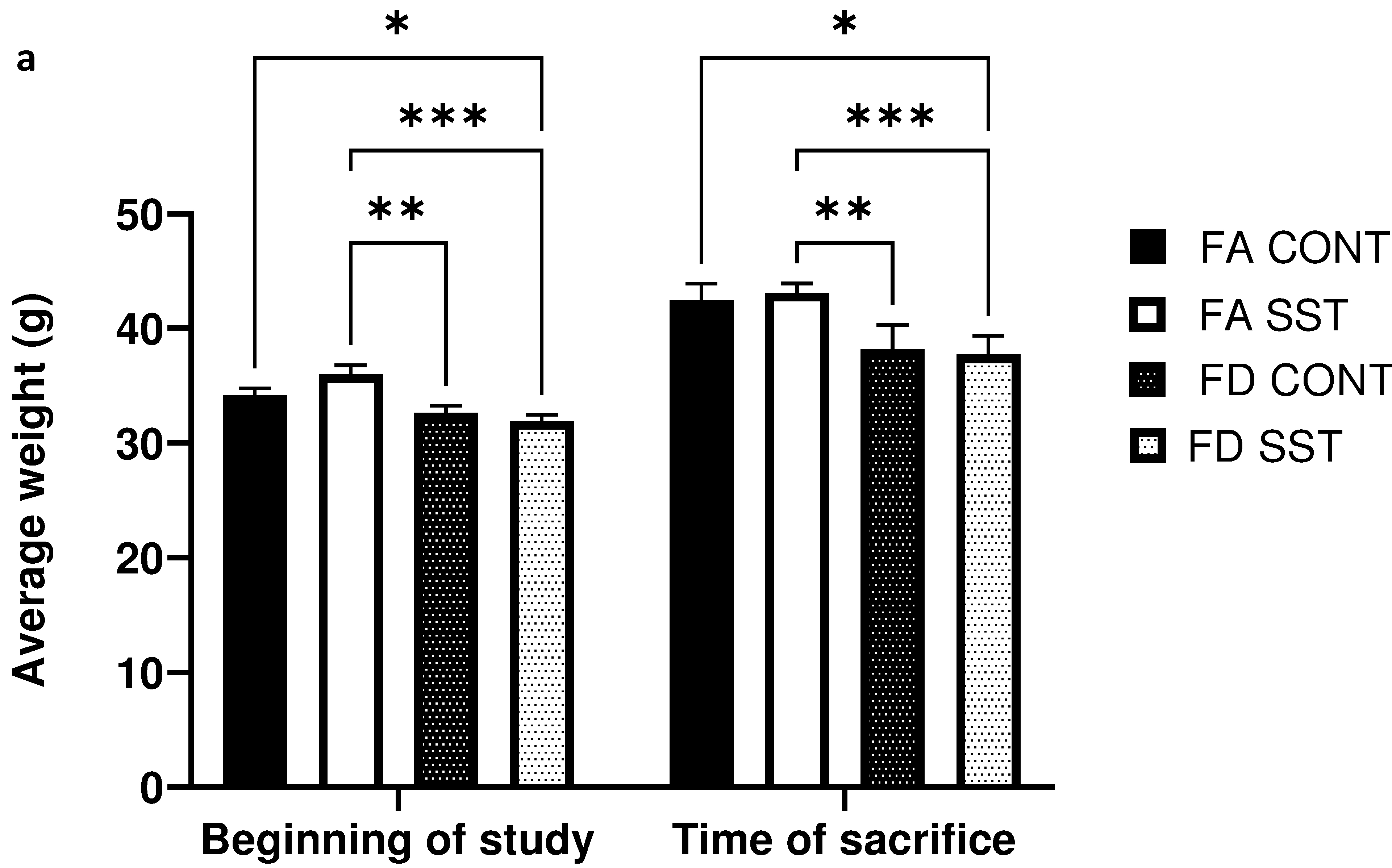

This study was designed to analyze the potential confounding effect of antibiotics used to induce folate depletion in mouse folate studies. Since antibiotics have been used non-therapeutically in animal husbandry to promote weight gain and growth39, we were interested in examining the long-term (21 weeks) effect of SST on animal weights. We monitored weight gain weekly for the duration of the study, however there was no significant difference after 21 weeks on the diets between matched groups (fig. 1a). The animals grew normally and did not exhibit any gross anomalies or physiological differences. We also did not observe any differences in food consumption (fig. S1) between the control and experimental groups.

Fig. 1.

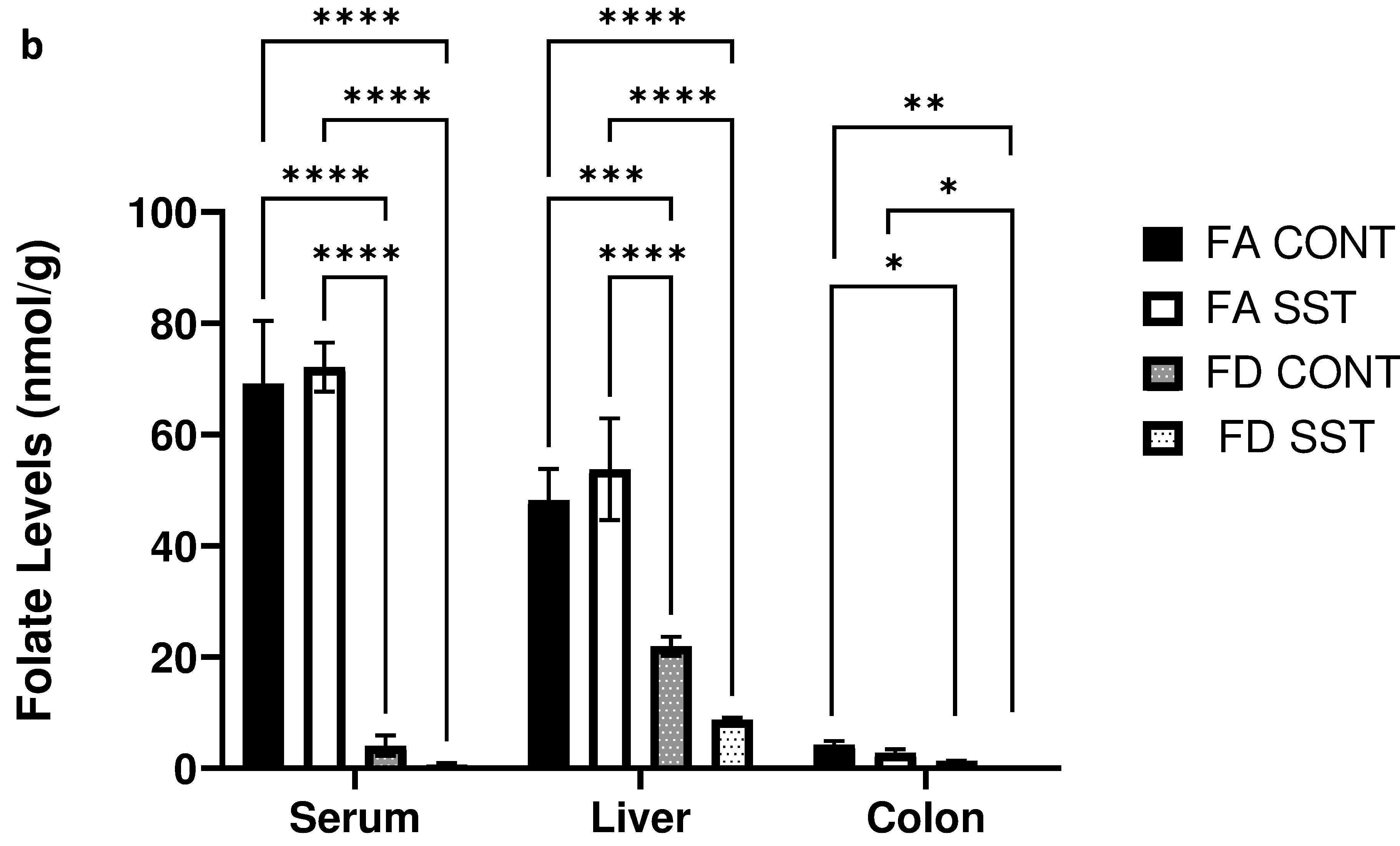

1% succinylsulfathiazole (SST) in the diet does not impact weight gain or folate levels in folate adequate and folate depleted c57BL/6 mice. a) Average mouse weights at the beginning of the experiment and after 21 weeks on respective diets (FA=folate adequate diet (2 mg folate/kg diet), FA SST= folate adequate diet (2 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST), FD=folate depleted diet (0 mg folate/kg diet), FD SST=folate depleted diet (0 mg folate/kg diet + 1%SST)). b) Folate levels (nmol/g) in the serum, liver and colon of mice fed FA and FA SST diets compared to folate levels in mice fed FD and FD SST. n=3 Bars, S.E.M, *p<0.05, **p<0.005, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001

We were interested in determining whether long term SST alone influences folate levels in the animals. We did not observe any significant difference in tissue specific folate levels between FA CONT and FA SST mice (fig. 1b). As expected, mice fed a folate depleted diet exhibited a significant decrease in folate levels in plasma, liver and colon compared to folate supplemented mice. The addition of SST to the folate depleted diet resulted in a measurable and consistent decrease in mean folate levels compared to both folate supplemented and folate depleted groups. However, this effect was not statistically significant when comparing FD SST to FD CONT in all tissues (fig. 1b). Furthermore, SST is known to competitively inhibit folate uptake in the colon due to structural similarities to folic acid, however we did not see a significant difference in colon folate levels in the antibiotic treated folate supplemented and folate depleted groups compared to their respective controls (fig. 1b). Thus, we show here that SST alone does not significantly affect liver, serum, and colon folate levels.

Antibiotic Effect on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

Our lab has previously shown that folate depletion provides protection against colon carcinogenesis in β-pol haploinsufficient mice35. We have also seen that folate status in the diet alters expression of genes in mTOR signaling (fig. S2); a major nutrient sensing pathway that has been implicated in cancer and aging. Since SST is widely used in folate depletion mouse studies, it was necessary to determine the effect of SST alone on mTOR signaling. mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin, is a conserved serine/threonine protein kinase downstream of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway40. It is present in two multiprotein complexes (mTORc1 and mTORc2) and integrates signals from multiple upstream factors such as insulin, hormones, cytokines, growth factors, stress, hypoxia, glucose, energy, and amino acid levels (fig. S3). mTORc1 specifically, is a key player in regulating multiple downstream processes such as cell growth, proliferation, and autophagy41. mTOR signaling has been shown to be dysregulated in various cancers, and is a key target in multiple life extension strategies42–44. Since our array data previously showed that mTOR signaling is reduced under folate depletion (fig. S2), we wanted to determine whether SST has a confounding effect on the expression of proteins in this pathway.

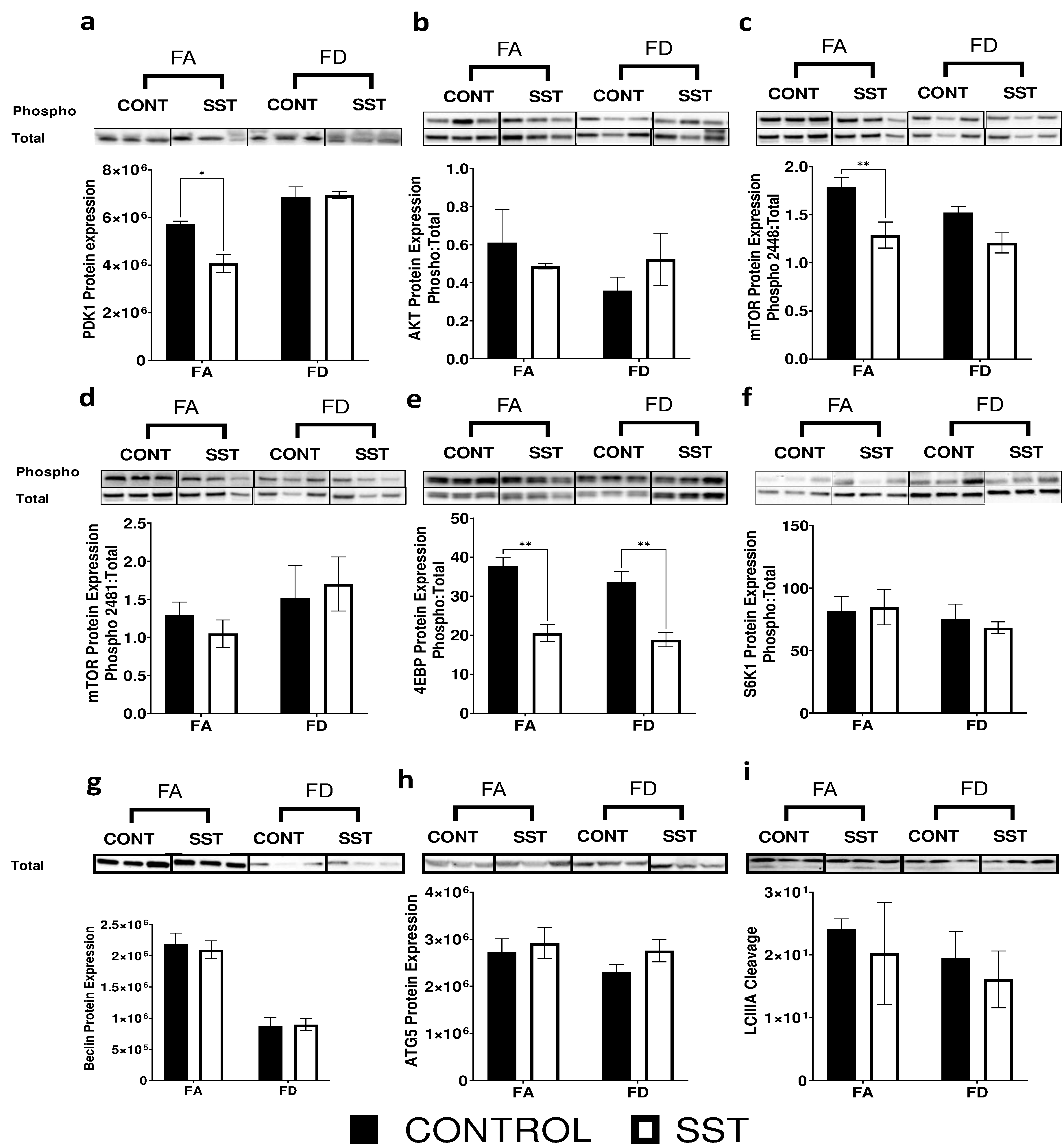

PDK1 (3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1) is an upstream activator of mTORc1 in the IRS-1/PI3K/AKT pathway. It phosphorylates AKT at the Thr308 residue, inhibiting the TSC1/TSC2 complex and activating mTORc145. mTORc2 on the other hand phosphorylates AKT (Ser473) as a feedback mechanism activating mTORc1. SST significantly decreases expression of PDK1 protein in our FA mice (fig. 2a), has no effect on AKT expression (fig. 2b), and significantly decreases phosphorylation of mTORc1 at the ser2448 residue in the FA group (fig. 2c). SST did not impact the auto-phosphorylation of mTORc1 at the ser2481 residue (fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Succinylsulfathiazole alters expression of proteins involved in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling in the liver of c57BL/6 mice resulting in decreased mTOR signaling. Western blot images and quantification of: a-b) phosphorylation of upstream regulators of mTOR (PDK-1 (ser241) and AKT(ser473)), c-d) mTOR phosphorylation at ser2448 and ser2481 residues, e-f) phosphorylation of downstream targets of mTOR (4ebp1 (thr37/46) and s6k1(thr421/ser424)), and g-i) expression of autophagy related proteins (Beclin, ATG5 and cleaved LCIII) in the liver of mice fed FA (2 mg folate/kg diet), FA SST (2 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST), FD (0 mg folate/kg diet) and FD SST (0 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST) diets. Normalized to total lane proteins. n=3 Bars, S.E.M., *p<0.05, **p<0.005

We examined the role of SST and its effect on mTORc1 regulation of protein synthesis and autophagy. The main characterized substrates of mTORc1 in regulating translation are S6K1 (ribosomal p70 S6 protein kinase) and 4E-BP1 (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1)45. In line with decreased mTORc1 activation at ser2448, we saw that in both FA and FD conditions, SST significantly decreases 4E-BP1 phosphorylation (fig. 2e) but does not influence S6K1 phosphorylation (fig. 2f). SST did not impact the expression of autophagy related proteins Beclin, ATG5 and LCIII cleavage (fig. 2g-i). Since SST altered expression of proteins in the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, we were interested in understanding whether it alters other upstream regulators of TOR signaling, specifically regulators of stress and energy metabolism.

The effect of SST on upstream regulators of mTOR

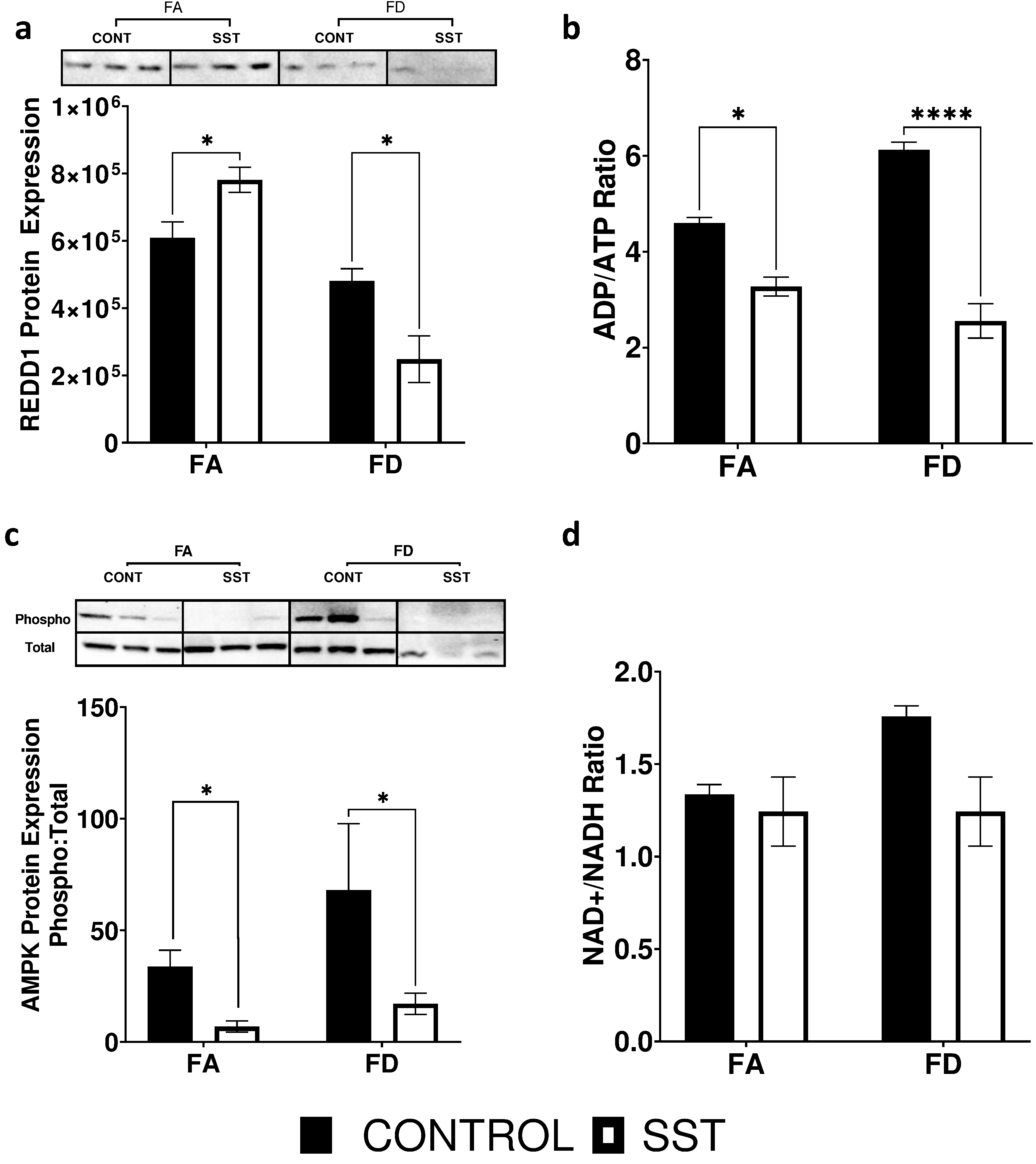

The mTOR signaling pathway is directly altered in response to hypoxia, DNA damage, and energy status41. REDD1 (regulated in development and DNA damage response 1) is induced following exposure to hypoxia, DNA damage and other environmental stresses such as energy stress and reactive oxygen species46,47. An increase in REDD1 levels leads to the activation of the TSC1/TSC2 complex and to the inhibition of mTORc1 (fig. S3). Interestingly, REDD1 protein expression in the liver significantly increases in response to SST in a folate adequate (fig. 3a) environment potentially providing evidence for mTOR reduced activation under this condition. Paradoxically, FD in combination with SST results in a significant decrease in REDD1 expression (fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Effect of SST on upstream regulators of mTOR in the liver of c57BL6 mice. a) Western blot image and quantification of REDD1 protein expression, b) ADP/ATP ratio, c) western blot image and quantification of AMPK (thr172) protein phosphorylation, and d) NAD+/NADH levels. Data is from the liver of mice fed: FA (2 mg folate/kg diet), FA SST (2 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST), FD (0 mg folate/kg diet) and FD SST (0 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST) diets. Westerns normalized to total lane proteins n=3 Bars, S.E.M., *p<0.05, ****p<0.0001

The mTOR signaling pathway has also been shown to be altered in response to energy status48. AMPK, a metabolic fuel gauge that detects changes in intracellular AMP/ATP ratio, directly inhibits mTORc149. It is activated in response to nutrient depletion and acts to maintain energy stores by switching on pathways that produce ATP and switching off pathways that consume ATP48. AMPK also enhances SIRT1 activity by increasing cellular levels of NAD+ 50. NAD cycles between the oxidized (NAD+) and reduced forms (NADH), partaking a central role in cellular metabolism and energy production. We saw a significant decrease in ADP/ATP ratio (fig. 3b) and AMPK phosphorylation (fig. 3c) in response to SST in both FA and FD mice. However, SST did not impact NAD+/NADH levels (fig. 3d) or SIRT1 expression (fig. 4).

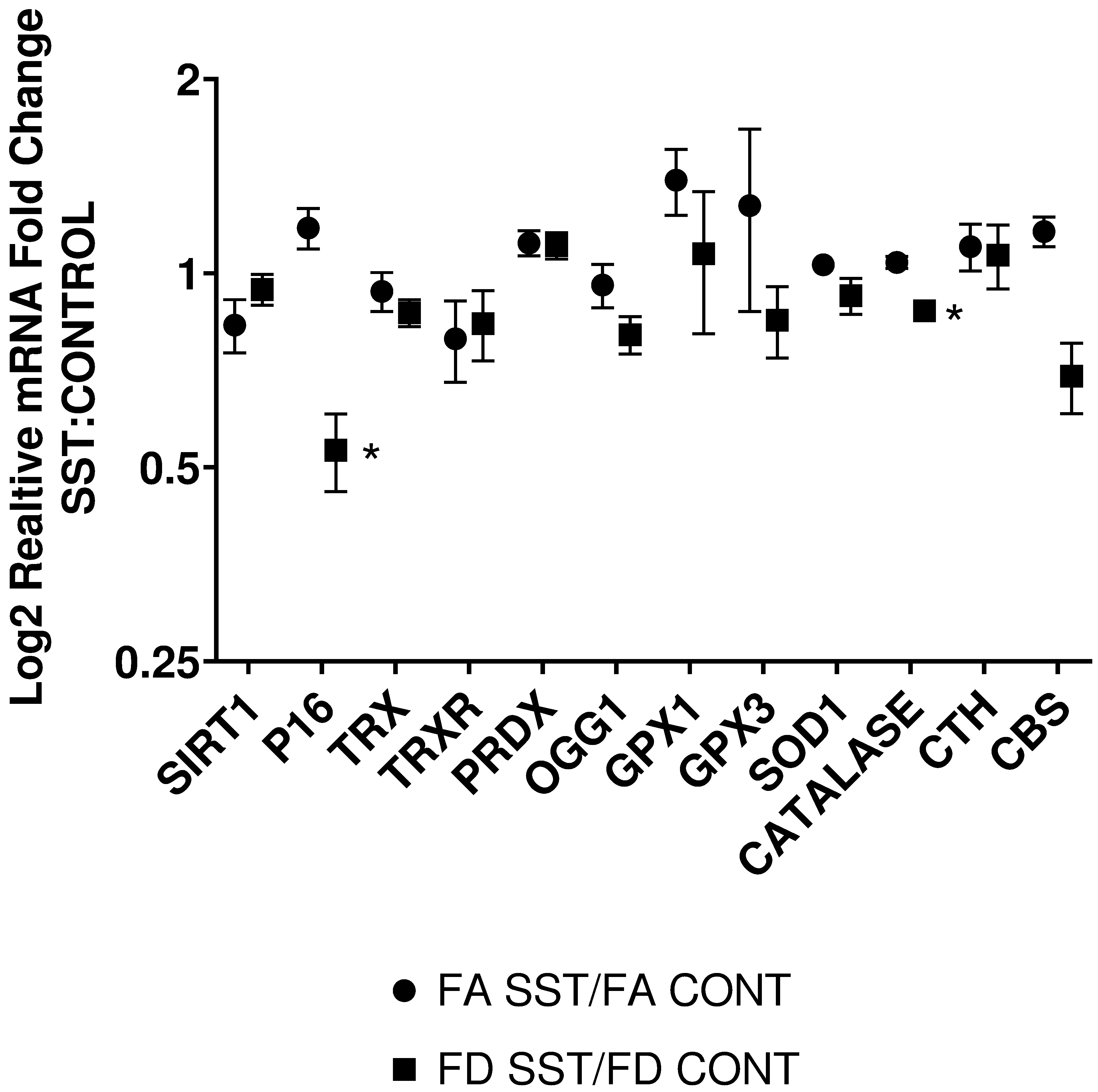

Fig. 4.

Effect of SST on relative expression of genes known to be altered by folate status and oxidative stress in the liver of mice fed FA (2 mg folate/kg diet), FA SST (2 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST), FD (0 mg folate/kg diet) and FD SST (0 mg folate/kg diet + 1% SST) diets. Data expressed as fold ratio of FA SST:FA CONT and FD SST:FD CONT and plotted on a log2 scale. n=3 Bars S.E.M., *p<0.05.

Discussion

mTOR microbiome interaction

Recently, various laboratories began uncovering the complex interactions between the gut microbiome and the host, shedding new light on the importance of these microorganisms on overall health 2,4–7,10. Antibiotic use in laboratory models can introduce significant confounding elements to an experiment due in part to the perturbation of the intestinal microbiome21,22,51. The intestinal microbiota plays a critical role in tuning and regulating many of the host immune and metabolic processes. Recent research has linked perturbation of the microbiome and the resulting dysbiosis to a host of pathologies like cancer, diabetes, metabolic disorders, inflammation, and immune dysfunction 84. A common switch that controls many of these processes is the mTOR pathway. Studies highlighting the intricate and bidirectional relationship between mTOR regulation and the gut microbiota interactions are being steadily uncovered by researchers52. Drugs that inhibit mTOR signaling such as metformin, reservatrol, and rapamycin have been shown to alter the gut microbiota and directly affect host metabolism and immune functions52–54. Similarly, aging researchers uncovered evidence that the crosstalk between mTOR and the microbiome plays a critical role in regulating immune homeostasis, inflammation, senescence, and slowing cellular aging52,55–57. Metabolites produced by the microbiome, including short chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate), modulate energy homeostasis, immune function, and cancer risk through complex interactions with the host52. Many groups have identified the mTOR pathway as being central to the protective effect rendered by gut metabolites58–60.

Antibiotic induced dysbiosis

Recent advances in sequencing and analysis are beginning to uncover the complexity and diversity of a healthy gut microbiome. The gut microbiome is normally dominated by 4 phyla (Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria) along with a host of other organisms including yeast, viruses, bacteriophages, helminths, and protozoa61. Antibiotic use has been associated with significant short and long-term changes to the gut microbiome, potentially leading to dysbiosis62. In fact, studies in humans and lab models have shown that antibiotic exposure in the early stages of life can lead to permanent changes in the gut microbiome profile leading to increased disease risk, susceptibility to obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cancer63. The effect of an antibiotic on the bacterial composition is dependent upon several factors including the drug’s pharmacokinetics. Following antibiotic administration, there is an increase in the facultative anaerobic Proteobacteria species, blooming of non-dominant and drug resistant species, as well as a decrease in butyrate and SCFA production63. Furthermore, antibiotic induced dysbiosis not only impacts nutrient absorption, metabolism, and redox status in the gut epithelium, but also affects distant organs like the liver and the brain63–65. Some non-absorbable antibiotics like rifaximin exert a positive effect by increasing the abundance of beneficial species66. Preliminary data from our lab revealed that SST produced a distinct shift in bacterial phyla composition. Furthermore, we observed 2 separate clusters within the SST treated group that correspond to higher Bacteroidetes:Firmicutes ratio, and Parabacteroides enrichment. Studies have suggested that such shifts are associated with dysregulated metabolism and predisposition to fatty liver disease67,68.

Effect of SST on mTOR pathway

Due to the extent, bidirectionality, and complexity of the interactions of the gut microbiome with the host, and specifically with critical pathways such as mTOR, the observed effect that we documented was paradoxical at times. Studies in germ free mice, and evidence from the use of antibiotics in animal husbandry found that antibiotic use increases nutrient absorption, total mass, and fat mass; a phenotype associated with mTORc1 activation64,69,70. Our results confirm increased energy availability through the decrease in ADP/ATP ratio, and the corresponding decrease in AMPK phosphorylation (fig. 3b-c). In a healthy unaltered microbiome, the production of SCFA helps regulate appetite, decrease intestinal permeability, lower inflammation and oxidative stress, and improve insulin sensitivity by upregulating AMPK in the liver and muscles17,71. Disruption of the microbiota can lead to decreased SCFA production, resulting in decreased AMPK and NADPH oxidase activity72. Despite the reduction of AMPK activation with SST, we did not observe a significant effect on NAD+/NADH ratio (fig. 3d) or SIRT1 expression (fig. 4). Furthermore, food consumption and animal weights did not differ significantly between antibiotic treated groups and control. Being a major regulator of mTORc1 signaling pathway, we would expect reduced AMPK phosphorylation to correspond to increased mTORc1 activity and its downstream targets as it signals increased energy availability. Surprisingly, mTORc1 activation at ser2448 as well as 4ebp phosphorylation was reduced by SST in both FA and FD groups, but no effect was seen on S6k1. Although S6k1 activation is commonly linked to mTORc1 signaling, evidence suggests that the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) can also promote S6k1 activation and synergistically enhance mTORc1 activation through RSK-mediated phosphorylation of Raptor73–77. Further research is required to explain and validate the discrepancy between 4E-BP and S6k phosphorylation in this model. P16 gene expression, a downstream target of S6K1 and an important regulator of cell cycle regulation and proliferation45, was only reduced in the FD mice by the addition of SST (fig. 4).

SST and oxidative stress

The link between gut microbiota, inflammation, and oxidative stress is well established78–81. Various factors such as diet, lifestyle, and antibiotic use can lead to dysbiosis and exacerbate oxidative stress through increased production and bioavailability of reactive oxygen species82. Specifically, antibiotic induced dysbiosis has been implicated in increased oxidative stress and damage, affecting distant organs such as the brain, liver, and cardiovascular system83–85. In our bid to understand how SST might be impacting mTOR, possibly through oxidative stress, we looked at REDD1(regulated in development and DNA damage 1), an important inhibitor of mTOR and a major sensor of oxidative stress and hypoxia. In FA mice, SST increased REDD1 protein expression, potentially providing a mechanistic validation to mTOR inhibition. However, REDD1 protein expression significantly decreased in the FD animals in response to SST. Furthermore, real time analysis of a panel of major antioxidant genes (TRX, TRXR, PRDX, OGG1, GPX1, GPX3, SOD and CAT) did not reveal any significant differences between SST and control groups (fig. 4). Since SST is used to deplete folate, directly impacting one carbon metabolism31–34, we were interested in looking at the effect of the antibiotic on the expression of genes in the transsulfuration pathway responsible for the production of the antioxidant glutathione. SST did not have a significant effect on the expression of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CTH), the key enzymes in the transsulfuration pathway (fig. 4).

Conclusion

Although a clear mechanistic elucidation of the effect of SST on the mTOR pathway did not emerge from this study, the results provide a clear insight on the significant and confounding effect SST exerts on the results of animal studies. SST impacted mTORc1 and its downstream target 4ebp, as well as energy levels and the energy gauge AMPK. SST impacted REDD1 differentially in FA and FD groups but had no effect on animal weights and food consumption, autophagy, and major antioxidant gene expression. Further research will be required to fully encompass the complexity of the host-microbiome interactions and how antibiotics such as SST can perturb various pathways involved in energy sensing, metabolism, growth, and oxidative stress. Since the effect of antibiotics is highly variable, potentially paradoxical, and dependent on various individual factors, we hope that this research will serve as cautionary account against the use of antibiotics for microbiome alterations in folate depletion and similar studies.

Supplementary Material

Funding

National Institutes of Health (CA121298 to A.R.H.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

References

- 1.O’Keefe SJD et al. Products of the Colonic Microbiota Mediate the Effects of Diet on Colon Cancer Risk. J. Nutr 139, 2044–2048 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace BD & Redinbo MR The human microbiome is a source of therapeutic drug targets. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 17, 379–384 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jovel J, Dieleman LA, Kao D, Mason AL & Wine E The Human Gut Microbiome in Health and Disease. Metagenomics Perspect. Methods, Appl 197–213 (2017) doi: 10.1016/B978-0-08-102268-9.00010-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tojo R et al. Intestinal microbiota in health and disease: Role of bifidobacteria in gut homeostasis. World J. Gastroenterol 20, 15163–15176 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffery IB Gut microbiota and aging 350, (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manuscript A The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 31, 69–75 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patterson EE et al. Gut microbiota, obesity and diabetes. Postgrad. Med. J 92, 286–300 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plaza-Diaz J, Gomez-Llorente C, Fontana L & Gil A Modulation of immunity and inflammatory gene expression in the gut, in inflammatory diseases of the gut and in the liver by probiotics. World J. Gastroenterol 20, 15632–15649 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milani C et al. The human gut microbiota and its interactive connections to diet. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet 29, 539–546 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill MJ Intestinal flora and endogenous vitamin synthesis. in European Journal of Cancer Prevention (1997). doi: 10.1097/00008469-199703001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leblanc JG et al. B-Group vitamin production by lactic acid bacteria - current knowledge and potential applications. Journal of Applied Microbiology (2011) doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossi M, Amaretti A & Raimondi S Folate production by probiotic bacteria. Nutrients 3, 118–134 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess C, O’Connell-Motherway M, Sybesma W, Hugenholtz J & Van Sinderen D Riboflavin production in Lactococcus lactis: Potential for in situ production of vitamin-enriched foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol (2004) doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.5769-5777.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim TH, Yang J, Darling PB & O’Connor DL A Large Pool of Available Folate Exists in the Large Intestine of Human Infants and Piglets. J. Nutr 134, 1389–1394 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asrar FM & O’Connor DL Bacterially synthesized folate and supplemental folic acid are absorbed across the large intestine of piglets. J. Nutr. Biochem (2005) doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pompei A et al. Administration of Folate-Producing Bifidobacteria Enhances Folate Status in Wistar Rats. J. Nutr (2007) doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller R & Gibson GR Modification of the intestinal microflora using probiotics and prebiotics. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, Supplement (1997) doi: 10.1080/00365521.1997.11720714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rong N, Selhub J, Goldin BR & Rosenberg IH Bacterially synthesized folate in rat large intestine is incorporated into host tissue folyl polyglutamates. J. Nutr 121, 1955–1959 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thoma C, Green TJ & Ferguson LR Citrus Pectin and Oligofructose Improve Folate Status and Lower Serum Total Homocysteine in Rats. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res (2003) doi: 10.1024/0300-9831.73.6.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorbach SL Perturbation of intestinal microflora. in Veterinary and Human Toxicology (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekirov I et al. Antibiotic-induced perturbations of the intestinal microbiota alter host susceptibility to enteric infection. Infect. Immun (2008) doi: 10.1128/IAI.00319-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DEARING WH & HEILMAN FR The effect of antibacterial agents on the intestinal flora of patients: the use of aureomycin, chloromycetin, dihydrostreptomycin, sulfasuxidine and sulfathalidine. Gastroenterology vol. 16 12–18 (1950). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jernberg C, Löfmark S, Edlund C & Jansson JK Long-term impacts of antibiotic exposure on the human intestinal microbiota. Microbiology (2010) doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040618-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.ARCHER HL & LEHMAN EP CLINICAL AND LABORATORY EXPERIENCES WITH SUCCINYL SULFATHIAZOLE. Ann. Surg (1944) doi: 10.1097/00000658-194404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.NELSON MM & EVANS HM The effect of succinylsulfathiazole on pteroylglutamic acid deficiency during lactation in the rat. Archives of biochemistry vol. 18 153–159 (1948). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degroote S, Hunting DJ, Baccarelli AA & Takser L Maternal gut and fetal brain connection: Increased anxiety and reduced social interactions in Wistar rat offspring following peri-conceptional antibiotic exposure. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol. Psychiatry (2016) doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.POTH EJ CLINICAL USE OF SUCCINYLSULFATHIAZOLE. Arch. Surg (1942) doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1942.01210200024002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.BELL HG Succinylsulfathiazole in resection for carcinoma of the colon; its. Trans. West. Surg. Assoc (1948). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stokstad ELR & Jukes TH Sulfonamides and Folic Acid Antagonists: A Historical Review. J. Nutr 117, 1335–1341 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patrick GL An Introduction to Medicinal Chemistry (5th edition) Oxford: (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgoon JM, Selhub J, Nadeau M & Sadler TW Investigation of the effects of folate deficiency on embryonic development through the establishment of a folate deficient mouse model. Teratology (2002) doi: 10.1002/tera.10040. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Zhao M et al. Chronic folate deficiency induces glucose and lipid metabolism disorders and subsequent cognitive dysfunction in mice. PLoS One (2018) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Le Leu RK, Young GP & McIntosh GH Folate deficiency diminishes the occurrence of aberrant crypt foci in the rat colon but does not alter global DNA methylation status. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 15, 1158–1164 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unnikrishnan A et al. Folate deficiency regulates expression of DNA polymerase β in response to oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med 50, 270–280 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ventrella-Lucente LF et al. Folate deficiency provides protection against colon carcinogenesis in DNA polymerase beta haploinsufficient mice. J Biol Chem 285, 19246–19258 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabelof DC et al. Imbalanced base excision repair in response to folate deficiency is accelerated by polymerase beta haploinsufficiency. J Biol Chem 279, 36504–36513 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horne DW & Patterson D Lactobacillus casei microbiological assay of folic acid derivatives in 96-well microtiter plates. Clin Chem 34, 2357–2359 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor SC & Posch A The design of a quantitative western blot experiment. BioMed Research International vol. 2014 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Dibner JJ & Richards JD Antibiotic growth promoters in agriculture: History and mode of action. in Poultry Science (2005). doi: 10.1093/ps/84.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laplante M & Sabatini DM mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laplante M & Sabatini DM mTOR signaling. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol (2012) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Porta C, Paglino C & Mosca A Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling in cancer. Frontiers in Oncology (2014) doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Zoncu R, Efeyan A & Sabatini DM mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12, 21–35 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.A. A & H. MK mTOR signaling for biological control and cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hay N & Sonenberg N Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev 2004, 18, 1926–1945. Genes Dev (2004) doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704.hibiting. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deyoung MP, Horak P, Sofer A, Sgroi D & Ellisen LW Hypoxia regulates TSC1/2-mTOR signaling and tumor suppression through REDD1-mediated 14–3-3 shuttling. Genes Dev (2008) doi: 10.1101/gad.1617608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Regazzetti C et al. Regulated in Development and DNA Damage Responses -1 (REDD1) Protein Contributes to Insulin Signaling Pathway in Adipocytes. PLoS One (2012) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hardie DG AMP-activated/SNF1 protein kinases: Conserved guardians of cellular energy. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology (2007) doi: 10.1038/nrm2249. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Kahn BB, Alquier T, Carling D & Hardie DG AMP-activated protein kinase: Ancient energy gauge provides clues to modern understanding of metabolism. Cell Metabolism (2005) doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Cantó C et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD + metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature (2009) doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Rowland IR, Mallett AK & Wise A The effect of diet on the mammalian gut flora and its metabolic activities. Crit. Rev. Toxicol (1985) doi: 10.3109/10408448509041324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Noureldein MH & Eid AA Gut microbiota and mTOR signaling: Insight on a new pathophysiological interaction. Microbial Pathogenesis (2018) doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Jung MJ et al. Chronic Repression of mTOR Complex 2 Induces Changes in the Gut Microbiota of Diet-induced Obese Mice. Sci. Rep (2016) doi: 10.1038/srep30887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shin NR et al. An increase in the Akkermansia spp. population induced by metformin treatment improves glucose homeostasis in diet-induced obese mice. Gut (2014) doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303839. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Chin RM et al. The metabolite α-ketoglutarate extends lifespan by inhibiting ATP synthase and TOR. Nature (2014) doi: 10.1038/nature13264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Fu X et al. 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits ATP synthase and mTOR Signaling. Cell Metab (2015) doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Mizunuma M, Neumann-Haefelin E, Moroz N, Li Y & Blackwell TK mTORC2-SGK-1 acts in two environmentally responsive pathways with opposing effects on longevity. Aging Cell (2014) doi: 10.1111/acel.12248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Pant K, Saraya A & Venugopal SK Oxidative stress plays a key role in butyrate-mediated autophagy via Akt/mTOR pathway in hepatoma cells. Chem. Biol. Interact (2017) doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang Y, Chen Y, Jiang H & Nie D The role of short-chain fatty acids in orchestrating two types of programmed cell death in colon cancer. Autophagy (2011) doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.14277. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 60.Zeng H et al. MTORC1 couples immune signals and metabolic programming to establish T reg-cell function. Nature (2013) doi: 10.1038/nature12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rizzatti G, Ianiro G & Gasbarrini A Antibiotic and Modulation of Microbiota A New Paradigm? J. Clin. Gastroenterol 52, S74–S77 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jandhyala SM et al. Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J. Gastroenterol 21, 8836–8847 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mu C & Zhu W Antibiotic effects on gut microbiota, metabolism, and beyond. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology vol. 103 9277–9285 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cox LM et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell (2014) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Nobel YR et al. Metabolic and metagenomic outcomes from early-life pulsed antibiotic treatment. Nat. Commun (2015) doi: 10.1038/ncomms8486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bajaj JS et al. Modulation of the Metabiome by Rifaximin in Patients with Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy. PLoS One (2013) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Brandl K & Schnabl B Intestinal microbiota and NASH. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolodziejczyk AA, Zheng D, Shibolet O & Elinav E The role of the microbiome in NAFLD and NASH. EMBO Mol. Med (2019) doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Angelakis E & Lagier JC Samples and techniques highlighting the links between obesity and microbiota. Microbial Pathogenesis (2017) doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lynch SV & Pedersen O The Human Intestinal Microbiome in Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med (2016) doi: 10.1056/nejmra1600266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim YA, Keogh JB & Clifton PM Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics and insulin sensitivity. Nutrition Research Reviews (2018) doi: 10.1017/S095442241700018X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu H, Qin L, Hu H & Wang Z Alteration of the Gut Microbiota and Its Effect on AMPK/NADPH Oxidase Signaling Pathway in 2K1C Rats (2019) doi: 10.1155/2019/8250619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Dennis PB, Pullen N, Pearson RB, Kozma SC & Thomas G Phosphorylation sites in the autoinhibitory domain participate in p70(s6k) activation loop phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem 273, 14845–14852 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kelleher RJ, Govindarajan A, Jung HY, Kang H & Tonegawa S Translational control by MAPK signaling in long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell 116, 467–479 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mukhopadhyay NK et al. An array of insulin-activated, proline-directed serine/threonine protein kinases phosphorylate the p70 S6 kinase. J. Biol. Chem (1992) doi: 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)50735-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Antion MD, Hou L, Wong H, Hoeffer CA & Klann E mGluR-Dependent Long-Term Depression Is Associated with Increased Phosphorylation of S6 and Synthesis of Elongation Factor 1A but Remains Expressed in S6K-Deficient Mice. Mol. Cell. Biol 28, 2996–3007 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gangarossa G et al. Repeated stimulation of dopamine D1-like receptor and hyperactivation of mTOR signaling lead to generalized seizures, altered dentate gyrus plasticity, and memory deficits. Hippocampus 24, 1466–1481 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dumitrescu L et al. Oxidative stress and the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev 2018, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tomasello G et al. Nutrition, oxidative stress and intestinal dysbiosis: Influence of diet on gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases. Biomed. Pap 160, 461–466 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luca M, Mauro M Mauro Di, Di M & Luca A Gut microbiota in Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The role of oxidative stress. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity vol. 2019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Weiss GA & Hennet T Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences vol. 74 2959–2977 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vasquez EC, Pereira TMC, Campos-Toimil M, Baldo MP & Peotta VA Gut Microbiota, Diet, and Chronic Diseases: The Role Played by Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity vol. 2019 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hao WZ, Li XJ, Zhang PW & Chen JX A review of antibiotics, depression, and the gut microbiome. Psychiatry Research vol. 284 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kalghatgi S et al. Bactericidal antibiotics induce mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative damage in mammalian cells. Sci. Transl. Med 5, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brunt VE et al. Suppression of the gut microbiome ameliorates age-related arterial dysfunction and oxidative stress in mice. J. Physiol 597, 2361–2378 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.