Abstract

Purpose

This Lyme disease early detection economic model, for patients with suspected Lyme disease without erythema migrans (EM), compares outcomes of standard two-tier testing (sTTT), modified two-tier testing (mTTT) and the DiaSorin Lyme Detection Algorithm (LDA), a combination of both serology tests and Interferon-ɤ Release Assay.

Patients and Methods

A patient-level simulation model was built to incorporate effectiveness estimation from a structured focused literature review, and health-care cost inputs for the United States, Germany, and Italy. Simulated clinical outcomes were 1) percent of patients with timely and correct diagnosis, 2) patients appropriately treated and exposed to antibiotics therapy, and 3) patients with late Lyme disease manifestations. Expected health outcomes were expressed in terms of differences in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) due to disseminated Lyme disease and persisting symptoms, and economic outcomes were analyzed from a third-party payer perspective.

Results

The DiaSorin LDA resulted in a better sensitivity compared to sTTT and mTTT, 84% vs 49% and 45%, respectively, in the base case (13% of infected patients in the tested population). Due to the improved diagnostic performance, the LDA-based strategy is expected to be more effective, providing mean incremental 0.024 QALYs per tested patient, or 0.19 per infected patient. Furthermore, from a third-party payer perspective, the adoption of the LDA-based strategy would reduce the expected health-care cost for suspected and confirmed Lyme disease by roughly 40%, ie about $410, €130, and €170 per tested patient in the United States, Germany, and Italy, respectively, compared to sTTT. The results are most sensitive to the infection rate in the tested population, with LDA maintaining a cost advantage for Lyme disease active infection rates ≥0.8-2.5%.

Conclusion

LDA early diagnostic testing and subsequent treatment of subjects with early Lyme disease without EM are expected to outperform traditional management strategies both clinically and economically in the US, Germany, and Italy.

Keywords: Lyme borreliosis, early diagnostics, QALYs, health-care cost, IGRA, serology

Introduction

Lyme disease (LD) is a tick-borne disease transmitted by hard ticks of the Ixodes genus (Ixodes ricinus in Europe).1,2 The infection is caused by spirochetes of the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, mainly B. Burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii and B. garinii.1 The first manifestation of the disease is often a localized rash known as erythema migrans (EM) that may resolve spontaneously. However, if left untreated, disseminated Lyme borreliosis can develop, manifesting in more severe forms such as neuroborreliosis or Lyme arthritis.3–5 Early diagnosis, and prompt appropriate therapy of Lyme borreliosis are necessary for avoiding the later and most impactful stages of the disease.

The diagnosis of LD is made clinically and in conjunction with laboratory serology tests. International guidelines, including the newly released guideline from the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR),6 recommend that an EM is sufficient for clinical diagnosis, eliminating the need for serological testing.7 However, EM are not always present, are frequently atypical, and in approximately 50% of the cases, there is no known history of a tick bite, which makes diagnosis considerably more difficult.8 Furthermore, with non-experts, uncertain recognition of an EM leads to a consequential body of confirmatory testing,9–11 a significant portion of which is prompted by the dual need to appease patient demand, and provide reassurance.12,13

Conventional serological testing for LD employs a two-tier solution employing an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test in the first tier followed by confirmatory IgM/IgG immunoblotting in the second tier for positive or equivocal results. Diagnostic performance is often unsatisfactory, especially in early infection, where standard two-tier testing (sTTT) rarely exceeds sensitivities of 50%.14,15 A study carried out by Branda et al discussed an alternative serology test strategy named modified two-tier testing (mTTT).16 The mTTT algorithm includes an EIA plus another confirmatory EIA for patients testing positive or equivocal. However, even with this alternative antibody detection assay sequence for patients suspected with an early infection, sensitivity ranged from only 36% to 54%.16

Challenges in diagnosing early Lyme infection with consequent suboptimal clinical management, increased health-care costs, and resulted in quality of life burden17 due to the difficulty of interpretation and limitations of IgG-seropositivity, which occurs relatively late during the infective course, and may persist for many years, even after infection has resolved.8

T-lymphocyte-mediated responses to seminal Borrelia burgdorferi antigens have been shown to result in the specific release of cytokines, especially interferon-gamma (IFN-ɤ), which can be measured using interferon gamma release assays (IGRA).18 A study from Branda et al states that strong interferon-gamma responses were observed in some cases shortly after initial infection, and thus IGRAs could provide a tool for detecting the infection earlier than antibody tests.18

A study conducted by Callister et al demonstrated that combining information from standard serological testing with IGRA resulted in higher sensitivity for early LD.14 The results showed a sensitivity of 83% when IGRA was combined to serology, versus 59% when only the serology was used (patients with EM taken as paradigm for early LD).14 Furthermore, IGRA + serology assay combination improved the discriminatory ability between ongoing and past infection.14

The aim of this study is to derive a model-based estimation of clinical and economic outcomes of a new testing algorithm co-developed by DiaSorin and QIAGEN, wherein Interferon-ɤ Release Assay (IGRA) testing is coupled with IgM and IgG serology (Lyme Detection Algorithm, LDA) to assess its comparative effectiveness and cost-effectiveness against sTTT and mTTT. As per the design of LDA and data on file at DiaSorin from the EU clinical study, the clinical performance in Europe of LDA is comparable to the results presented by Callister et al on US bacteria strains.

Patients and Methods

Literature Search

Official guidelines issued by health authorities and/or scientific societies were examined, and a focused scientific literature search was conducted for English, German, Italian and French language studies published in the electronic literature databases PubMed and EMBASE.

The terms for the searched focused scientific literature included “Lyme Disease”, “Lyme borreliosis”, “Erythema migrans”, “Disseminated Lyme”, “Neuroborreliosis”, “Post-treatment Lyme Disease”, “Early Lyme diagnosis”, “Lyme guidelines”, “Lyme disease diagnostic guidelines”, “Lyme treatment”, “Healthcare costs”, “Economic evaluation”, “Health economics”, “DALYs Lyme disease”, “QALYs Lyme disease”, “Lyme cost-effectiveness”.

Economic Model

The economic evaluation was based on a patient-level simulation on a decision-analytic tree structure built in Microsoft Excel® which assessed the outcomes associated with sTTT, mTTT (for US only, as it is not currently in use in European countries) and LDA diagnostic-therapeutic algorithms.

The model presents a mathematical simplification of possible clinical pathways experienced by patients presenting with suspected clinical Borrelia infection. Positive and negative test results of infected or non-infected subjects depend upon the degree of infection, time from infection to tested specimen collection, and the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of the applied testing strategy.

Patients testing positive had higher chances of getting timely prescriptions of an appropriate therapy. Infected patients treated with an early and appropriate therapy had better chances of a favorable clinical outcome, reducing risks of infective dissemination and chronic symptoms. On the other hand, falsely positive patients risk being exposed to unnecessary and potentially harmful antibiotic treatment.

The timeframe of the evaluation covers the whole duration of the care episode for a single suspected infection, defined as the time span elapsing from tick bite to complete resolution of symptoms, meaning that patients stay in the model at least for the time needed to have a final laboratory result (true negative patients). Given the limited timeframe of the analysis, no discounting on costs or benefits, accruing after the first year, was applied.

10,000 patients with suspected LD due to known history of tick bite and/or suggestive symptoms, but without EM, were individually sent through three alternative simulation arms, which differed for the initial diagnostic part (varying sensitivity, specificity), time to final test result, and treatment decision. The patient population analyzed replicated the target population in active infection rate, and time from exposure to serological testing.

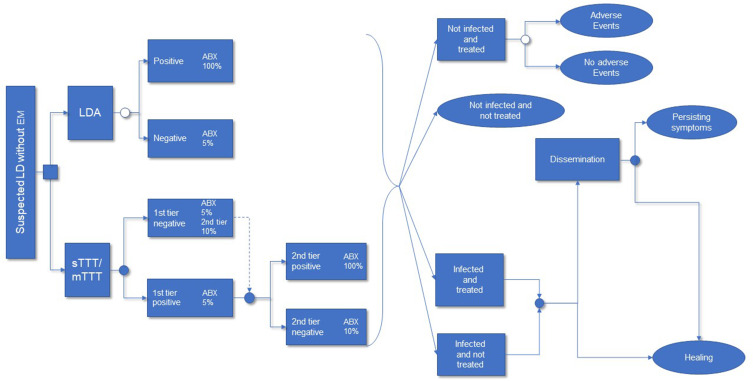

The model, populated with data from literature searches (detailed in the following sections), and whose patient pathway is depicted in (Figure 1) estimated three types of outcome:

clinical: percent of patients with timely and correct diagnoses, patients appropriately treated or inappropriately exposed to antibiotic therapy (ABX) and patients with late LD manifestations;

health: QALYs lost due to LD;

economic: health-care costs for third-party payers, including costs for diagnostics, ABX, management of late LD and ABX adverse effects.

Figure 1.

Simplified Patient Pathway Model Schemea.

Notes: The square at the root of the tree is the decision node. The white dot is a probabilistic node. The blue dot is a probabilistic and time-dependent node. The oval shape is the end of pathway. aInfective status, diagnostic performance, and clinical decision rules (left part of the figure) determine the distribution of patients into therapeutic categories (central part); infective status, exposure to appropriate antibiotic treatment, and its timeliness (not represented) influences probabilities of clinical outcomes (right part of the figure).

Abbreviations: LD, Lyme Disease; LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ABX, antibiotic therapy.

Inputs

A review study conducted by Eldin et al, scored sixteen guidelines from seven countries. The best ratings were obtained by the National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE), and the European Federation of Neurological Societies (EFNS).1 Therefore, here the NICE guidelines are adopted as the main source of diagnostic performance indicators, and diagnostic-therapeutic pathways.

More than 120 publications were screened, and considered relevant, if they provided at least one relevant health, clinical or economic outcome evaluated according to evidence-based medical criteria, including real-world data published in peer-reviewed journals, if referring to North American or European patients.

Diagnostic performance data for sTTT and mTTT were extracted by the meta-analysis conducted within the NICE guideline development process.19 LDA data were derived from a controlled study conducted on 29 patients with EM and 192 healthy controls, whose blood samples were tested with both IGRA and standard serology (Table 1).14 Importantly, all diagnostic performance studies on early LD were conducted on patients with EM for practical reasons, and – in general practice and in the presented model, comparable performances are assumed for the early LD patients without EM.

Table 1.

Diagnostic Performances Used for ELISA, ImmunoBlot and LDA

| Time From Infection to Sampling | Within 6 Weeks | After 6 Weeks | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| ELISA (first-tier for sTTT and mTTT, second tier for mTTT)19 | 67% (55–77%) | 98% (94–99%) | 86.7% (64–97%) | 98.1% (97–99%) |

| ImmunoBlot (second-tier for sTTT)19 | 72% (55–85%) | 97% (91–100%) | 87% (60–98%) | 97% (91–100%) |

| LDA14 | 83% (64–94%) | 97% (93–99%) | 83% (64–94%) | 97% (93–99%) |

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays; CI, confidence interval.

The active infection rate in the tested population was set at 13%, based on the positivity rate reported by Lee-Lewandrowski et al on over 5 million tests performed in the USA during the period 2010 to 2016, using the diagnostic performance and timing parameters in Table 1.13

Data regarding real-life pathways and clinical decision-making following test results were largely irretrievable; therefore, some assumptions (Table 2), had to be made, backed by clinical practice, to depict the patient journeys, which only in part follow clinical guideline recommendations. Slight deviations from the guidelines were considered for the real life clinical practice model. It was assumed that some clinicians practicing in high LD incidence areas will prescribe prophylactic antibiotic treatment without EM and without following guideline suggested algorithm. Our assumption is that these behaviors will not change following the availability of a new test. Therefore, 5% of patients is assumed to receive antibiotic treatment following first-tier testing, both with no confirmatory testing (positive first-tier), and despite negative laboratory results. Furthermore, we assumed that 10% of patients testing negative on the first tier will anyways undergo second tier testing.

Table 2.

Therapeutic Pathway and Treatment Effectiveness Inputs

| Event | Condition | Probability/Proportion of Cases | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient receives ABX already after the 1st tier if | Test positive | 5% | Assumption |

| Test negative | 5% | Assumption | |

| 2nd tier testing is performed if | Test positive | 100% | Assumption |

| Test negative | 10% | Assumption | |

| Time to second tier | 4 weeks | Assumption | |

| Patient receives ABX after the 2nd tier if | Test positive | 100% | Assumption |

| Test negative | 10% | Assumption | |

| Patient receives ABX after LDA if | Test positive | 100% | Assumption |

| Test negative | 5% | Assumption | |

| Healing of the infection occurs if | ABX given < 30 infection days | 95% | 2 |

| ABX given < 60 infection days | 79.4% | Linear interpolation | |

| ABX given < 6 infection months | 48.20% | ||

| No ABX given >= 6 infection months | 17% | 20 | |

| Testing is repeated if | A false negative patient results unhealed after > 6 months | 10% | Assumption |

| Patient receives ABX after 6 months if | Symptomatic, with no previous ABX received | 50% | Assumption |

| Symptomatic, despite previous ABX received | 50% | Assumption | |

| Persistent symptoms develop in | Not healed, but 1st ABX received < 3 months from tick bite | 10% | 2 |

| Not healed, but 1st ABX received < 6 months from tick bite | 20% | ||

| Not healed, but 1st ABX received > 6 months from tick bite | 80% |

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; ABX, antibiotic therapy.

In terms of timing, it was assumed that the time from tick bite to sample collection and first tier testing would be normally distributed with a mean of 3 weeks for these patients without typical EM, having non-specific symptoms and/or a known history of tick bite. It was further assumed that clinical decision-making following second-tier test results in the relevant strategies would occur after a further mean lag of 1 week. These assumptions were challenged in sensitivity analyses. Data on time-dependent antibiotic treatment effectiveness (Table 2) were repurposed from previous research.2,20

The impact on quality of life of patients was based on observational data collected from a Dutch population with confirmed LD, detailed by stage. In this study,21 the EQ-5D questionnaire was used for estimating specific disutilities for localized LD (EM, neglected in the model), disseminated LD, and persisting LD symptoms after successful treatment. These, combined with disease stage duration data collected in the study alongside the quality of life impact, were used to attribute QALY loss due to advanced LD stages in the model (Table 3).

Table 3.

QALY Impact of LD

| Lyme borreliosis Outcome | Disutility Weight (95% CI) | Duration of Disease in Years (95% CI) | QALY Loss per Episode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disseminated Lyme21 | 0.26 (0.21–0.33) | 0.43 (0.30–0.66) | 0.11 (0.07–0.18) |

| Persisting symptoms21 | 0.36 (0.33–0.40) | 4.57 (3.32–5.23) | 1.66 (1.37–1.97) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

The economic analysis adopted the perspective of a third-party payer. Consequently, it considered direct health-care costs, namely for diagnostic work-up and for antibiotic treatment, including the management of emerging adverse events and the costs for advanced LD (disseminated and with persisting symptoms). The cost of testing procedures was based on cost for reagents provided by DiaSorin’s Market Intelligence for all evaluated settings. According to Mouseli et al, these represent 37% of total testing costs: a lump sum for structural and labor cost was calculated, common to all types of test within a country, and added to each diagnostic session to obtain the full testing cost (Table 4).22

Table 4.

Economic Input per Patient

| Resource/Condition | US ($) | Source | DE (€) | Sources | IT (€) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First ELISA | 8 | 23 | 7 | 23 | 14 | 23 |

| Second ELISA (mTTT) | 16a | – | – | |||

| ImmunoBlot (TTT) | 23b | 14b | 28b | |||

| LDA | 40c | 39c | 44c | |||

| GP office visit | 62 | 20,24,25 | 27 | 26 | 19 | 27 |

| Oral ABXd | 35 | 32 | 28 | 25 | 29 | |

| AEs oral ABX | 6 | 3 | 30–32 | 3 | 30–32 | |

| Disseminated LD | 11,467 | 4829 | 5754 | |||

| Persisting symptoms | 11,612 | 3326 | 3963 |

Notes: a3 USD per ELISA, 100% IgM+IgG. b10 USD/5€/10€/per test: 50% only IgG, 50% IgG+IgM (patients with blood collection w/in 4 weeks. cPrice of LDA indicative and not reflective of final price of the product. dAssuming 50% doxycycline and 50% amoxicillin treatments, at recommended doses.

Abbreviations: LD, Lyme Disease; LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; TTT, two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ABX, antibiotic therapy; GP, general practitioner; AEs, Adverse Events; US, United States of America; DE, Federal Republic of Germany; IT, Italian Republic.

The other unit costs pertaining to the US health-care system were sourced from previous economic evaluations, after updating reported figures to 2020 values, using the HCPI for Health.20,24,25,32

For Germany and Italy, costs for GP office visits and antibiotic treatment were taken from published sources,26–29 and updated to 2020 values.32 The costs for ABX adverse events management were obtained by applying the same proportion of GP visit costs as seen in the US to the local values. For Germany, insufficient data on the management costs of advanced disease stages (per episode) exist. Hence, these costs were estimated combining evidence on annual hospital costs of the German LD population from the health-care utilization study by Lohr et al (values updated to 2020) with the overall cost structure of the Dutch late LD population, as reported by van den Wijngaard et al.21,30 In this study, 75% of the annual LD hospital cost is accrued by late disseminated LD patients representing 50% of their total direct health-care costs. The remaining 25% of LD hospital cost is accrued by patients with persisting symptoms, representing about 25% of their overall direct health-care cost.21 The cost for advanced LD stages in Italy, for which no data was available, was estimated using the values calculated for Germany after applying value conversions based on purchasing power parities (PPP) for health services, as reported by the OECD,33 and updated using the HCPI for Health.32 The economic inputs are summarized in Table 4.

Sensitivity Analyses

Robustness of results was tested via univariate Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis (DSA) and Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis (PSA). In the DSA, model robustness was tested by varying one of the parameters to both extremely high and low values, while maintaining all other parameters fixed: this was useful to inform which parameters are most influential to the results, and whether variations within the range of plausible values could change the analytical conclusion. Here, extreme values chosen corresponded to the upper and higher limit of the 95% confidence interval, where available, or to increases/decreases of 50% of the mean value. In the PSA, total impact of the uncertainty surrounding point estimates was used in the base case analysis, and evaluated by repeating the full patient-level simulation 1000 times, running each with a unique combination of parameter values randomly drawn from the probability distributions that represented their variability (Table 5).

Table 5.

Model Parameters for Base Case and Sensitivity Analyses

| Parameter | Base Case | SE | Dist. Type | DSA min | DSA max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % infected patients | 13% | 1.3% | Normal | 6.5% | 19.5% |

| Median time from tick bite to first tier (weeks) | 3 | 0.3 | Normal | 1.5 | 4.5 |

| Sensitivity ELISA within 6 weeks | 67% | 5.6% | Normal | 55% | 77% |

| Specificity ELISA within 6 weeks | 98% | 1.3% | Normal | 94% | 99% |

| Sensitivity ELISA after 6 weeks | 87% | 8.3% | Normal | 64% | 97% |

| Specificity ELISA after 6 weeks | 98% | 0.6% | Normal | 97% | 99% |

| Sensitivity Blot within 6 weeks | 72% | 7.7% | Normal | 55% | 85% |

| Specificity Blot within 6 weeks | 97% | 2.3% | Normal | 91% | 100% |

| Sensitivity Blot after 6 weeks | 87% | 9.7% | Normal | 60% | 98% |

| Specificity Blot after 6 weeks | 97% | 2.3% | Normal | 91% | 100% |

| Sensitivity test LDA | 82.8% | 7.6% | Normal | 64% | 94% |

| Specificity test LDA | 96.9% | 1.4% | Normal | 93% | 99% |

| % treated with positive 1st test, pending confirmation | 5% | 0.5% | Normal | 2.5% | 7.5% |

| % treated with negative 1st test | 5% | 0.5% | Normal | 2.5% | 7.5% |

| % second tier after first tier positive | 100% | NO PSA | – | 80% | |

| % second tier after first tier negative | 10% | 1.0% | Normal | 5% | 20% |

| Time from 1st to 2 tier (weeks) | 1 | 0.1 | Normal | 0.5 | 1.5 |

| % treated with positive 2nd tier | 100% | NO PSA | Normal | 80% | |

| % treated with negative 2nd tier (ongoing clinical suspicion) | 10% | 1.0% | Normal | 5% | 20% |

| % treated with positive LDA | 100% | NO PSA | – | 80% | |

| % treated with negative LDA (ongoing clinical suspicion) | 5% | 0.5% | Normal | 2.5% | 7.5% |

| % healed treated within 30 days | 95% | 9.5% | Normal | 48% | 100% |

| % healed treated within 60 days | 79% | 7.9% | Normal | 40% | 100% |

| % healed treated beyond 60 days | 48% | 4.8% | Normal | 24% | 72% |

| % healed never treated | 17% | 1.7% | Normal | 9% | 26% |

| % re-tested if negative but symptoms persists > 12 weeks | 10% | 1.0% | Normal | 5% | 15% |

| % treated if symptoms persist > 12 w (no previous ABX) | 50% | 5.0% | Normal | 25% | 75% |

| % treated if symptoms persist > 12 w (previous ABX) | 50% | 5.0% | Normal | 25% | 75% |

| % persistent symptoms patients treated early | 10% | 1.0% | Normal | 5% | 15% |

| % persistent symptoms patients treated late | 20% | 2.0% | Normal | 10% | 30% |

| % persistent symptoms patients never treated | 80% | 8.0% | Normal | 40% | 100% |

| Disability disseminated Lyme | 0.262 | 3.1% | Normal | 0.205 | 0.325 |

| Disability persisting symptoms | 0.364 | 1.8% | Normal | 0.326 | 0.397 |

| Duration disseminated Lyme (years) | 0.432 | 0.09 | Normal | 0.304 | 0.656 |

| Duration persisting symptoms (years) | 4.568 | 0.34 | Normal | 3.919 | 5.234 |

| Cost first-tier _ US ($) | 8.1 | 0.81 | Normal | 4.1 | 12.2 |

| Cost 2nd tier mTTT _ US ($) | 16.2 | 1.62 | Normal | 8.1 | 24.3 |

| Cost blot test _ US ($) | 22.7 | 2.27 | Normal | 11.3 | 34.0 |

| Cost LDA_US ($) | 40.1 | 4.01 | Normal | 20.1 | 60.2 |

| Cost antibiotic course _ US ($) | 34.8 | 5.02 | Normal | 26 | 45 |

| Cost adverse events _ US ($) | 5.8 | 2.38 | Normal | 3 | 12 |

| Cost office visit _ US ($) | 62.1 | 15.82 | Normal | 31 | 93 |

| Cost disseminated Lyme _ US ($) | 11,466 | 1755 | Normal | 8026 | 14,906 |

| Cost persisting symptoms _ US ($) | 11,611 | 2172 | Normal | 8127 | 16,639 |

| Cost TTT first-tier _ DE (€) | 6.8 | 0.68 | Normal | 3.38 | 10.14 |

| Cost blot test _ DE (€) | 13.9 | 1.39 | Normal | 6.94 | 20.83 |

| Cost LDA _ DE (€) | 39.3 | 3.93 | Normal | 19.63 | 58.89 |

| Cost antibiotic course _ DE (€) | 33.2 | 1.71 | Normal | 30 | 36 |

| Cost adverse events _ DE (€) | 2.6 | 1.06 | Normal | 1 | 5 |

| Cost office visit _ DE (€) | 27.7 | 7.07 | Normal | 14 | 42 |

| Cost disseminated Lyme _ DE (€) | 4829 | 1339 | Normal | 2345 | 7595 |

| Cost persisting symptoms _ DE (€) | 3326 | 3442 | Normal | 2689 | 4036 |

| Cost TTT first-tier _ Italy (€) | 13.5 | 1.35 | Normal | 6.76 | 20.27 |

| Cost blot test _ Italy (€) | 27.8 | 2.78 | Normal | 13.89 | 41.66 |

| Cost LDA _ Italy (€) | 43.5 | 4.35 | Normal | 21.76 | 65.27 |

| Cost antibiotic course _ Italy (€) | 25.0 | 4.08 | Normal | 17 | 33 |

| Cost adverse events _ Italy (€) | 2.6 | 1.06 | Normal | 1 | 5 |

| Cost office visit _ Italy (€) | 19.5 | 4.96 | Normal | 10 | 29 |

| Cost disseminated Lyme _ Italy (€) | 5754 | 1596 | Normal | 2795 | 9051 |

| Cost persisting symptoms _ Italy (€) | 3963 | 409 | Normal | 3204 | 4809 |

Abbreviations: LD, Lyme Disease; LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; TTT, two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ABX, antibiotic therapy, US, United States of America; DE, Federal Republic of Germany; SE, standard error; Dist. Type, distribution type; DSA min., Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis minimum; DSA max., Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis maximum.

Results

Consistently with the inputs, LDA has a higher detection rate (84%, vs sTTT 49% and mTTT 45%) and more rapid definitive response: these two factors allow for prompter prescription of appropriate antibiotic(s) and reduce the probability of developing more severe disease stages (Table 6). These, in turn, dictate the vast majority of humanistic and economic impact outcomes (Table 7).

Table 6.

Clinical Result

| sTTT | mTTT | LDA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of 1st tests | 10,000 | 10,000 | 10,000 |

| Total number of 2nd tests | 1976 | 1976 | 0 |

| Total LD cases | 1290 | 1290 | 1290 |

| Infected patients diagnosed | 635 (49%) | 585 (45%) | 1079 (84%) |

| Not infected treated with ABX | 539 | 535 | 680 |

| Infected not treated with ABX | 567 | 616 | 199 |

| Total number of re-tested | 61 | 65 | 21 |

| Total antibiotics administered | 1508 | 1481 | 1906 |

| Early/asymptomatic LD only | 761 | 718 | 999 |

| w/disseminated LD | 529 | 572 | 291 |

| w/persisting symptoms | 215 | 233 | 86 |

Note: In bold, the most relevant clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations: LD, Lyme Disease; LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ABX, antibiotic therapy.

Table 7.

Incremental Cost and Effectiveness results for US, Germany, and Italy. Values are Expressed as Mean Difference (LDA – Comparator) per Tested Patient

| LDA vs sTTT | LDA vs mTTT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | D | I | US | |

| Incremental total cost | $-411 | €-132 | €-167 | $-478 |

| Incremental total QALYs | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.024 | 0.028 |

| ICER | LDA dominates | LDA dominates | LDA dominates | LDA dominates |

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; US, United States of America; DE, Federal Republic of Germany; IT, Italian Republic; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

The present analysis indicates that LDA limits the health burden of LD in the evaluated population (Table 7), expressed in terms of QALYs lost due to the disease, to no more than 50% of what is expected with the current two-tiered strategy. This reduction corresponds to 0.024 mean additional QALYs per tested patient, or 0.19 additional QALYs per infected patient, as compared to sTTT. With the LDA-based approach, expenses for the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway of a patient tested for suspected early Lyme disease without a recognized EM, are expected to be reduced by approximately 40% of the total or roughly, $410, €130, and €170 per patient tested in the United States, Germany, and Italy, respectively, as compared to sTTT, with mTTT expected to be slightly worse than sTTT (Table 8). The LDA algorithm thus proves to be the strategy associated with expected best effectiveness and lowest total cost (ie, dominant in decision-analytic jargon), in all evaluated settings, when compared to sTTT and mTTT (the latter in the US only, as it is not currently a relevant strategy in Europe).

Table 8.

Base Case Economic and Health Result USA, Germany, and Italy

| sTTT | mTTT | LDA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | D | I | US | US | D | I | |

| Total cost per patient tested | 983 | 375 | 436 | 1051 | 573 | 243 | 270 |

| Testing | 13 | 10 | 19 | 10 | 40 | 39 | 44 |

| Treatment | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 5 |

| Physician visit | 106 | 33 | 23 | 106 | 88 | 28 | 20 |

| AE management | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Late disease management | 607 | 255 | 304 | 656 | 334 | 141 | 167 |

| Persisting Symptoms management | 250 | 72 | 85 | 271 | 100 | 29 | 34 |

| Total QALYs lost per patient tested due to LD | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.018 |

| Early LD | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Disseminated LD | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Persisting symptoms | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.036 | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.014 |

| Total QALYs lost per infected patient due to LD | 0.323 | 0.323 | 0.323 | 0.350 | 0.136 | 0.136 | 0.136 |

| Early LD | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Disseminated LD | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.049 | 0.026 | 0.026 | 0.026 |

| Persisting symptoms | 0.277 | 0.277 | 0.277 | 0.300 | 0.111 | 0.111 | 0.111 |

Note: In bold, the most relevant economic and quality of life outcomes.

Abbreviations: LD, Lyme Disease; LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; ABX, antibiotic therapy; AEs, Adverse Events; US, United States of America; DE, Federal Republic of Germany; IT, Italian Republic; QALY, quality-adjusted life year.

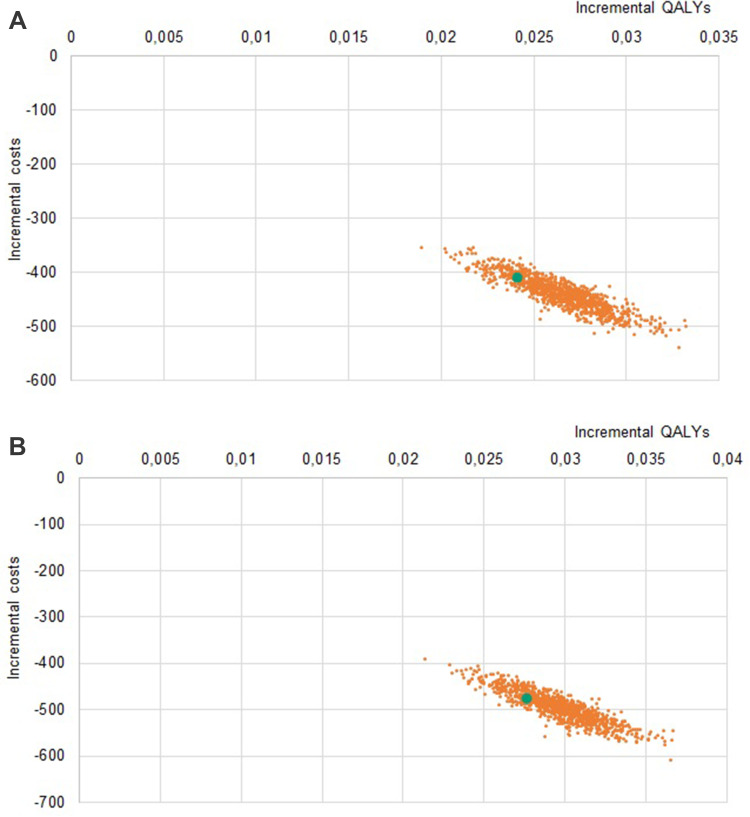

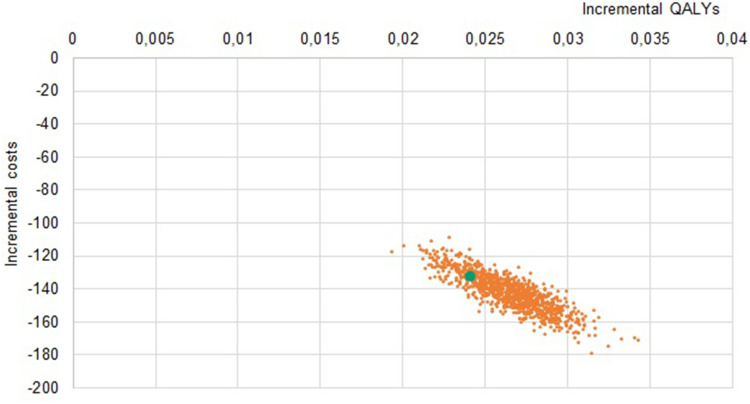

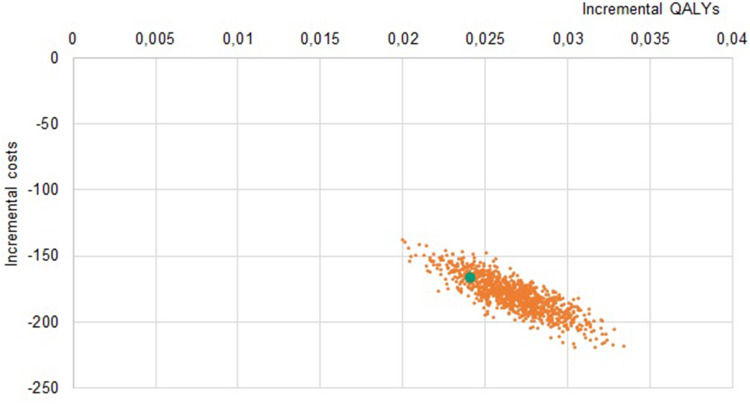

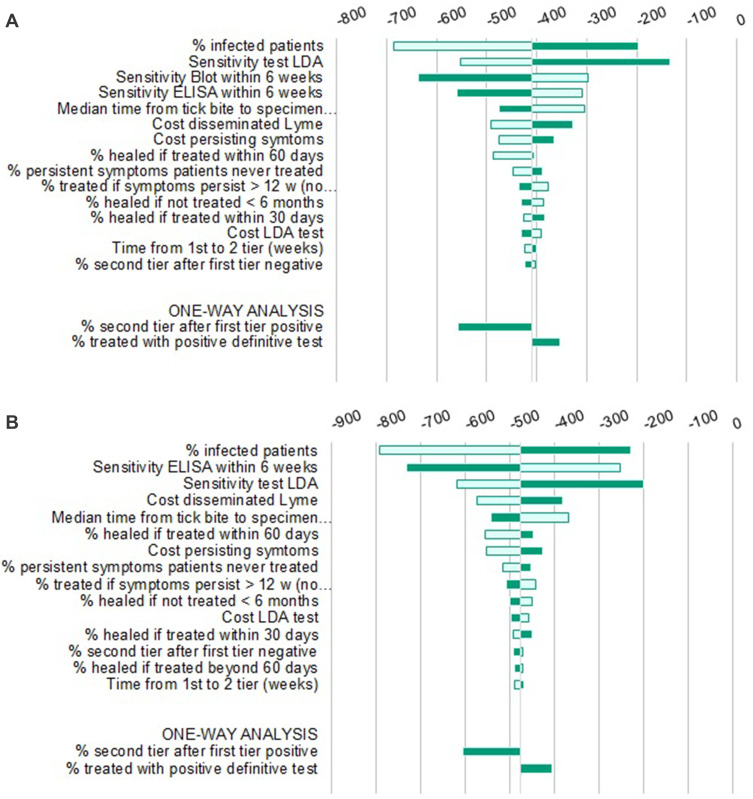

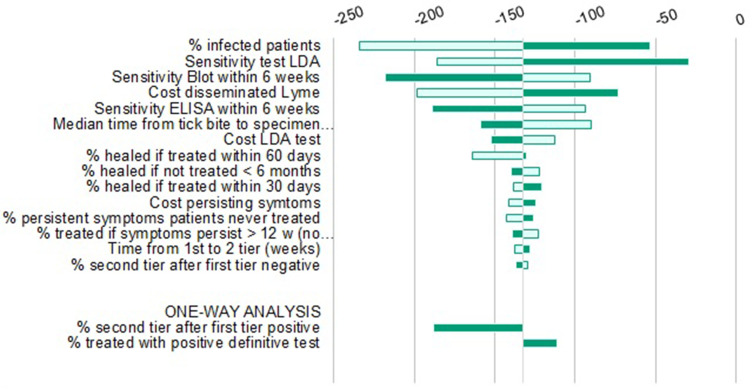

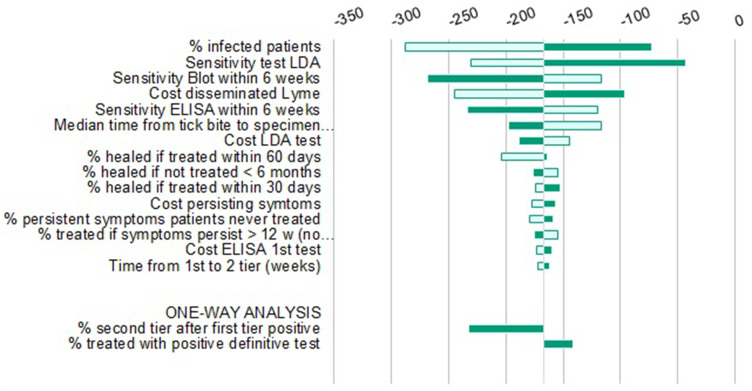

Solidity of results was confirmed with sensitivity analyses: in the PSA, all simulations lay in the same quadrant as the base case (Figures 2–4), indicating strong confidence in the direction of differences in both clinical and economic estimates.

Figure 2.

(A) Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, US. (B) Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs mTTT, US.

Note: The orange dots represent the samples, the green dot represents the base case.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; US, United States of America.

Figure 3.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, Germany.

Note: The orange dots represent the samples, the green dot represents the base case.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; DE, Federal Republic of Germany.

Figure 4.

Probabilistic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, Italy.

Note: The orange dots represent the samples, the green dot represents the base case.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; IT, Italian Republic.

Similarly, in the DSA (Figures 5–7), none of the variations tested changed the main conclusion of the analysis. As determined by the sensitivity analysis, results were most responsive to variations in the active infection rate in the tested populations; therefore, threshold analyses with this parameter were conducted in order to identify the lowest infection rate for which LDA remained dominant. Results indicate that this threshold runs as low as 0.8%, 2.5% and 1.9% for the US, Germany and Italy, respectively.

Figure 5.

(A) Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, US. (B) Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs mTTT, US.

Notes: Light green is the result at the lower 95% CI boundary; Dark green is the result at higher 95% CI boundary.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; mTTT, modified two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; US, United States of America.

Figure 6.

Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, Germany.

Notes: Light green is the result at the lower 95% CI boundary; Dark green is the result at higher 95% CI boundary.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; DE, Federal Republic of Germany.

Figure 7.

Deterministic Sensitivity Analysis LDA vs sTTT, Italy.

Notes: Light green is the result at the lower 95% CI boundary; Dark green is the result at higher 95% CI boundary.

Abbreviations: LDA, Lyme Detection Algorithm; sTTT, standard two-tier testing; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years; IT, Italian Republic.

Discussion and Conclusion

Difficulties with clinical management of early LD are mainly related to the challenges associated with making correct diagnoses. While clinical guidelines exist to direct and inform medical decision-making, perceived difficulties related to proper adherence have limited the breadth and extent of their application, especially for those physicians with less LD experience.9 Experts have highlighted a clear need to

simplify the testing algorithm for Lyme disease, improving sensitivity in early disease while still maintaining high specificity and providing information about the stage of infection.15

Furthermore, Branda et al emphasized that the false-negative window, where the kinetics of antibody response cannot be useful for LD diagnosis, will need to be closed either with improved direct diagnostic tests or with non-antibody-based indirect tests, such as cytokine release assays or metabolite-based assay.18

In this manuscript, an economic model-based analysis of early LD is presented, aimed at estimating the potential for improved clinical management using a new diagnostic-therapeutic paradigm based on a single high performing test session. The test, under model conditions and assumptions, was shown to support and inform an immediate therapeutic decision-making process by leveraging the combination of IGRA and serology into a single diagnostic kit, leading to the realization of substantial benefits to both patients and health-care providers across multiple geographies.

These results should be interpreted carefully and cautiously, as limitations do apply to the analyses. Most importantly, the diagnostic performance of the new LDA strategy has relatively little exposure within the public domain, and as such, should be considered to be preliminary. More insight will be gained from broader international multicenter studies that are currently ongoing.34 Knowledge refinements characterizing long-term clinical course and reliable predictors of adverse outcomes in LD are also expected from an ongoing well-designed study by Vrijmoeth et al.35 Despite these limitations, the predictions of the economic model of early LD presented here compare well with data available in the literature, in terms of both clinical and economic outcomes, and affirm the validity of its main conclusions.

A review on economic evaluation studies on Lyme disease available in peer-reviewed literature was recently published by Mattingly et al36. The results of this review support the methods and sources used in the present study, underlying the conservative approach of our analysis, at least from the perspectives of the patient and the society overall, as it neglects indirect costs, that represent an important share of overall LD burden.

From the clinical point of view, the most relevant outcome predicted by the model, ie the percentage of treatment failures and corresponding, subsequent development of persistent symptomatologies consequent to current TTT-based guidance, is well in line with published literature.37–40

From an economic standpoint, the expected reduction in disease burden is consistent with the findings of previous research, highlighting the economic potential of late LD stages prevention by improved diagnostic accuracy, or by vaccination.19–21,24,25,28,31,41,42

We point out that indirect costs have not been incorporated in the model, for two main reasons: firstly, the adopted cost perspective is the one of the third-party payers that will ultimately have to decide upon the funding of the new technology, and secondly the limited data availability with estimates available only for the Netherlands, not for the countries evaluated.21,31 It is conceivable that savings with the most efficient technology would increase in case productivity losses due to the disease and its management would be factored into the analysis.

The previous advances and achievements notwithstanding, potential savings for third-party payers, will need coordination amongst health systems to become practically actionable and accessible: most of the cost savings relate to late and disseminated disease, managed by secondary and tertiary health providers, while the main stakeholders in the diagnostic phase, and potential drivers of the adoption of the new strategy, will be prescribing primary care physicians and purchasing diagnostics laboratories. A translation of projected into actual cost savings will require policy-makers to foster diagnostic and clinical appropriateness by predisposing adequate reimbursement strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Claudia Zierold, Frank Blocki, and Luca Pallavicini for their contribution to this paper.

Disclosure

We acknowledge the full financial support of DiaSorin SpA for this research manuscript. DiaSorin provided support in the form of salaries for authors Fabrizio Bonelli, Mariella Calleri, Matteo Pinciroli, Beatrice Grassi, and Hirad Houshmand. Lorenzo Pradelli is the co-owner and an employee of AdRes and has received project funding from DiaSorin SpA. Dr Maurizio Ruscio has received consulting honoraria from DiaSorin SpA.

References

- 1.Eldin C, Raffetin A, Bouiller K, et al. Review of European and American guidelines for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Médecine et Maladies Infectieuses. 2019;49(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rauer S, Kastenbauer S, Fingerle V, Hunfeld KP, Huppertz HI, Dersch R. Lyme Neuroborreliosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(45):751–756. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2018.0751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stanek G, Fingerle V, Hunfeld KP, et al. Lyme borreliosis: clinical case definitions for diagnosis and management in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(1):69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wormser GP, Dattwyler RJ, Shapiro ED, et al. The clinical assessment, treatment, and prevention of lyme disease, human granulocytic anaplasmosis, and babesiosis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1089–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofhuis A, Herremans T, Notermans DW, et al. A prospective study among patients presenting at the general practitioner with a tick bite or erythema migrans in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e64361. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lantos PM, Rumbaugh J, Bockenstedt LK, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), American Academy of Neurology (AAN), and American College of Rheumatology (ACR): 2020 Guidelines for the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Lyme Disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(UK) National Guideline Centre (UK). Lyme disease: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2018. April. (NICE Guideline, No. 95) NICE Guideline: methods. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542111/. Accessed April30, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.van de Schoor FR, Baarsma ME, Gauw SA, et al. Validation of cellular tests for Lyme borreliosis (VICTORY) study. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):732. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4323-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vreugdenhil TM, Leeflang M, Hovius JW, et al. Serological testing for Lyme Borreliosis in general practice: a qualitative study among Dutch general practitioners. Eur J General Practice. 2020;26(1):51–57. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2020.1732347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forde K, Cryan B, Keady D, et al. GP201 Incidence and clinical presentation of serologically confirmed paediatric lyme disease in Ireland over a 5 year period. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(Suppl 3):A112–A112. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns V, Wallenhorst C, Rietbrock S, Martinez C. Incidence of Lyme disease in the UK: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7):e025916. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiting P, Toerien M, de Salis I, et al. A review identifies and classifies reasons for ordering diagnostic tests. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(10):981–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee-Lewandrowski E, Chen Z, Branda J, Baron J, Kaufman HW. Laboratory blood-based testing for lyme disease at a national reference laboratory. Am J Clin Pathol. 2019;152(1):91–96. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqz030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Callister SM, Jobe DA, Stuparic-Stancic A, et al. Detection of IFN-gamma Secretion by T Cells collected before and after successful treatment of early lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):1235–1241. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques AR. Laboratory diagnosis of Lyme disease: advances and challenges. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):295–307. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Branda JA, Strle K, Nigrovic LE, et al. Evaluation of modified 2-tiered serodiagnostic testing algorithms for early lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(8):1074–1080. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore A, Nelson C, Molins C, Mead P, Schriefer M. Current guidelines, common clinical pitfalls, and future directions for laboratory diagnosis of lyme disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis j. 2016;22(7):1169. doi: 10.3201/eid2207.151694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Branda JA, Steere AC. Laboratory diagnosis of lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021;34(2):e00018–00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Guideline Centre (UK). Lyme disease: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK); 2018. April. (NICE Guideline, No. 95.) NICE Guideline: methods. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng95/evidence/c-diagnostic-tests-pdf-4792271008. Accessed April30, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shadick NA, Liang MH, Phillips CB, Fossel K, Kuntz KM. The cost-effectiveness of vaccination against lyme disease. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(4):554–561. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.4.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Wijngaard CC, Hofhuis A, Harms MG, et al. The burden of Lyme borreliosis expressed in disability-adjusted life years. Eur J Public Health. 2015;25(6):1071–1078. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouseli A, Barouni M, Amiresmaili M, Samiee SM, Vali L. Cost-price estimation of clinical laboratory services based on activity-based costing: a case study from a developing country. Electron Physician. 2017;9(4):4077–4083. doi: 10.19082/4077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DiaSorin. Business intelligence data; 2020.

- 24.Hsia EC, Chung JB, Schwartz JS, Albert DA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the Lyme disease vaccine. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(6):1651–1660. doi: 10.1002/art.10270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lantos PM, Brinkerhoff RJ, Wormser GP, Clemen R. Empiric antibiotic treatment of erythema migrans-like skin lesions as a function of geography: a clinical and cost effectiveness modeling study. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Dis. 2013;13(12):877–883. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2013.1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anastassopoulou A, Wahle K, Hain J, Schroeder C, Ehlken B. PIN43. Cost of influenza in Germany. Value Health. 2013;16:A348. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garattini L, Castelnuovo E, Lanzeni D, Viscarra C, Gruppo di studio DYSCO VISITE DV. Durata e costo delle visite in medicina generale: il progetto DYSCO. Farmeconomia. Health economics and therapeutic pathways. 2003;4(2):6. doi: 10.7175/fe.v4i2.773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Müller I, Freitag MH, Poggensee G, et al. Evaluating frequency, diagnostic quality, and cost of Lyme borreliosis testing in Germany: a retrospective model analysis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:595427. doi: 10.1155/2012/595427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AIFA Liste di trasparenza AIFA [homepage on the Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://www.aifa.gov.it/liste-di-trasparenza. Accessed February4, 2021.

- 30.Lohr B, Müller I, Mai M, Norris DE, Schöffski O, Hunfeld KP. Epidemiology and cost of hospital care for Lyme borreliosis in Germany: lessons from a health care utilization database analysis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;6(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van den Wijngaard CC, Hofhuis A, Wong A, et al. The cost of Lyme borreliosis. Eur J Public Health. 2017;27(3):538–547. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckw269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eurostat Harmonized Indices of Consumer Prices (HICPs) - Health Sector [homepage on Internet]; 2020. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/hicp. Accessed April30, 2021

- 33.OECD Purchasing power parities - Health services [homepage on Internet]; 2014. Available from: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=PPP2014. Accessed February4, 2021.

- 34.DiaSorin and QIAGEN collaborate on novel QuantiFERON-based test with breakthrough potential for earlier detection of Lyme disease [homepage on Internet]; 2019. Available from: https://diasoringroup.com/sites/diasorincorp/files/allegati_pressrel/pr_diasorin_qiagen_lyme.pdf. Accessed April30, 2021.

- 35.Vrijmoeth HD, Ursinus J, Harms MG, et al. Prevalence and determinants of persistent symptoms after treatment for Lyme borreliosis: study protocol for an observational, prospective cohort study (LymeProspect). BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):324. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-3949-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mattingly TJ, Shere-Wolfe K. Clinical and economic outcomes evaluated in Lyme disease: a systematic review. Parasit Vectors. 2020;13(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s13071-020-04214-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feder H, Johnson B, O’Connell S, et al. A Critical Appraisal of “Chronic Lyme Disease”. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1422–1430. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DeLong A, Hsu M, Kotsoris H. Estimation of cumulative number of post-treatment Lyme disease cases in the US, 2016 and 2020. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):352. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6681-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rebman AW, Bechtold KT, Yang T, et al. The clinical, symptom, and quality-of-life characterization of a well-defined group of patients with posttreatment lyme disease syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017;4:224. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marques A. Chronic Lyme disease: a review. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22(2):341–360, vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adrion ER, Aucott J, Lemke KW, Weiner JP. Health care costs, utilization and patterns of care following Lyme disease. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0116767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joung H-A, Ballard ZS, Wu J, et al. Point-of-care serodiagnostic test for early-stage Lyme disease using a multiplexed paper-based immunoassay and machine learning. medRxiv. 2019;19009423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]