Abstract

Objectives

To eliminate the hepatitis C virus (HCV) by 2030, Canada must adopt a microelimination approach targeting priority populations, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM). Accurately describing HCV prevalence and risk factors locally is essential to design appropriate prevention and treatment interventions. We aimed to estimate temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence between 2005 and 2018 among Montréal MSM, and to identify socioeconomic, behavioural and biological factors associated with HCV exposure among this population.

Methods

We used data from three cross-sectional surveys conducted among Montréal MSM in 2005 (n=1795), 2009 (n=1258) and 2018 (n=1086). To ensure comparability of seroprevalence estimates across time, we standardised the 2005 and 2009 time-location samples to the 2018 respondent-driven sample. Time trends overall and stratified by HIV status, history of injection drug use (IDU) and age were examined. Modified Poisson regression analyses with generalised estimating equations were used to identify factors associated with HCV seropositivity pooling all surveys.

Results

Standardised HCV seroprevalence among all MSM remained stable from 7% (95% CI 3% to 10%) in 2005, to 8% (95% CI 1% to 9%) in 2009 and 8% (95% CI 4% to 11%) in 2018. This apparent stability hides diverging temporal trends in seroprevalence between age groups, with a decrease among MSM <30 years old and an increase among MSM aged ≥45 years old. Lifetime IDU was the strongest predictor of HCV seropositivity, and no association was found between HCV seroprevalence and sexual risk factors studied (condomless anal sex with men of serodiscordant/unknown HIV status, number of sexual partners, group sex).

Conclusions

HCV seroprevalence remained stable among Montréal MSM between 2005 and 2018. Unlike other settings where HCV infection was strongly associated with sexual risk factors among MSM, IDU was the pre-eminent risk factor for HCV seropositivity. Understanding the intersection of IDU contexts, practices and populations is essential to prevent HCV transmission among MSM.

Keywords: hepatitis C, gay men, seroprevalence, risk factors, epidemiology (general)

Introduction

Canada is not on track to eliminate the hepatitis C virus (HCV) as a public health threat by 2030.1 2 Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) have been identified as a priority population for HCV microelimination.3–5 Since 2000, HCV epidemics have been reported among MSM living with HIV in industrialised countries.6 In this population, global HCV incidence has increased from 2.6 per 1000 person-years pre-2000 to 8.1 per 1000 person-years post-2010,7 with high reinfection rates,6 and global HCV seroprevalence was estimated at 6.4% from 2002 to 2015.8 Comparatively, the HCV burden has remained stable among HIV-negative MSM, with estimates of seroprevalence ranging from 0.0% to 3.4%9–13 and a global incidence of 0.4 per 1000 person-years.14 Nevertheless, acute HCV infections have recently been reported among HIV-negative MSM without a history of injection drug use (IDU) in Europe,15 the USA16 and Vancouver, British Columbia (Canada).17 These data may mask variations across geographical settings, highlighting the importance of local contexts and related risks.

In industrialised countries, most HCV infections have been attributed to the use of unsterile needles and drug paraphernalia, and receipt of blood or blood products before the introduction of HCV screening.18 In parallel, evidence from Europe, the USA and Vancouver shows that sexual transmission can account for a substantial proportion of incident HCV infections among MSM.6 17 19–21 Two other overlapping population groups may be at increased risk of being chronically infected with HCV: individuals born between 1945 and 1975, due to exposures to HCV-contaminated blood and blood products before 1990,22 and immigrants originating from HCV endemic countries.23 Socioeconomic factors such as education and income can also influence the risk of acquiring HCV among MSM.19 24–26 The impact of these factors on HCV transmission among MSM subgroups is context-dependent and may vary by HIV status. Additionally, sexual and injecting behaviours may interact, for example through the practice of chemsex, a form of sexualised drug use associated with a higher risk of HCV infection among MSM.27 28 To date, there has been little evidence of sexual transmission of HCV among MSM in Canada.12 13 17 29 30

The variability in HCV incidence and prevalence among MSM populations, as well as the diversity of potential routes of transmission reflect the importance of using locally valid epidemiological evidence to inform tailored interventions targeting microelimination. Scarce evidence exists on HCV prevalence and risk factors among MSM subgroups in Canadian cities. In Vancouver, HCV seroprevalence among all MSM was estimated at 5% in a cross-sectional study conducted in 2008–2009.12 In this city, 17% of MSM living with HIV tested HCV seropositive, against 10% in a similar study conducted in Toronto, Ontario in 2010–2012.13 Temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence among MSM have not been assessed in Canada, and available cross-sectional data suggest potential within-country variability in seroprevalence. In Montréal, Québec (Canada), up-to-date and comprehensive information is required to inform HCV elimination interventions among MSM.

In this study, we aimed to (1) investigate temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence among MSM living in Montréal from 2005 to 2018, overall and stratified by HIV status, IDU status and age group; and (2) identify the social, behavioural and biological factors associated with HCV exposure among this heterogeneous population.

Methods

Data sources and harmonisation

Three cross-sectional surveys of sexually transmitted and bloodborne infections were conducted among Montréal MSM in 2005, 2009 and 2018: Argus 1, Argus 2 and the first wave of the Engage cohort study, respectively. These surveys have been previously described.[w1, w2] Briefly, they combined HIV, HCV and syphilis surveillance and behavioural monitoring through self-administered questionnaires. In 2005 (n=1957) and 2009 (n=1873), locations where MSM can be found were identified. In 2005, venues were selected using convenience sampling, and in 2009 time-location sampling was used, where sampling probabilities are generated at the location and individual level.[w3, w4] In 2018, a community-based sample of 1179 MSM were recruited using respondent-driven sampling (RDS), a link-tracing method that uses information about participants’ social networks to estimate their probability of being recruited and adjust for the biases associated with oversampling/undersampling of certain groups.[w5] Eligibility criteria varied slightly across the three surveys (online supplementary file 2).

sextrans-2020-054464supp001.pdf (180KB, pdf)

To compare the three surveys, we first harmonised the eligibility criteria across data sets. Our analyses were restricted to cis-gender men aged ≥18 years who reported sexual activity with a man in the past 6 months (P6M) and resided in Montréal. The sensitivity and specificity of the assays used for anti-HCV antibody detection in the three surveys were comparable (sensitivity: 100% in 2005, 2009 and 2018; specificity: 99.95% in 2005 and 2009, and 99.69% in 2018).[w1, w2, w6]

Temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence

We estimated HCV seroprevalence in 2005, 2009 and 2018, among all MSM, stratified by HIV status, lifetime history of IDU and age group, and among HIV-negative MSM without a history of IDU. To ensure comparability of the samples across time, regression-based standardisation was performed. The RDS-weighted 2018 survey was used as the standard and the other surveys were adjusted to yield the same distribution of age, sexual orientation, annual income and first language. This was achieved by first fitting multivariable logistic regression models with HCV seropositivity as the outcome (defined as a positive anti-HCV antibody test) to the 2005 and 2009 data, separately. Age was modelled using a restricted cubic spline,[w7] and we investigated the presence of multiplicative statistical interaction between each pair of covariates. For the stratified analyses, the same model was fitted separately among each subgroup of interest. Using these models, we then predicted the individual probability of testing HCV seropositive using the covariate patterns observed in the 2018 standard sample, among all MSM and by subgroup. Finally, we computed the weighted mean of these individual probabilities using Volz-Heckathorn weights[w8] to estimate standardised HCV seroprevalence among the different groups at all time points. We obtained 95% CIs using cluster-level block bootstrap, with clusters corresponding to the recruitment site in 2005 (n=40 sites) and 2009 (n=39 sites) and to the initial seed of the recruitment chain in 2018 (n=27 seeds). We performed complete case analyses as only 5% of observations had any missing value for the variables used in these estimations.[w9]

Factors associated with HCV seropositivity

Pooling data from the three surveys, we examined potential determinants of HCV seropositivity using prevalence ratios. We used univariable and multivariable modified Poisson regression models with generalised estimating equations (with exchangeable correlation structures), accounting for clustering.[w10–w12] The following predictors were selected a priori based on their potential association with HCV: survey year, lifetime history of IDU, HIV seropositivity, history of syphilis (defined as a reactive serological test), age (categorical), birth outside of Canada, annual income ≥$C30 000, education level higher than high school, sexual orientation other than gay/homosexual, self-identification as Indigenous, first language other than French/English, and specific sexual practices reported in the P6M: transactional sex (defined as having given/received money, drugs, or other goods or services in exchange for sex), condomless anal sex (CAS) with a man of serodiscordant/unknown HIV status, >5 male sexual partners and group sex. We used multiple imputation by chained equations for missing values as 33% of observations had at least one missing value for these variables, principally information regarding CAS (23%).[w13, w14]

We also investigated whether the impact of sexual practices on HCV varied by HIV status, and quantified the joint association of lifetime IDU and sexual behaviours with the outcome. We assessed the presence of additive and multiplicative interactions between the following terms: (1) HIV seropositivity and four sexual risk factors reported in the P6M (ie, transactional sex, CAS with a man of serodiscordant/unknown HIV status, number of sexual partners and group sex); and (2) history of IDU and the same four factors. To evaluate multiplicative interaction, we included the product term of each selected pair of factors in the main analysis model separately and examined the estimate and CI of each product term coefficient.[w15] Additive interaction was assessed by obtaining the relative excess risk due to interaction and its CI.[w16, w17] All analyses were conducted using R V.3.5.3,[w18] with the RDS,[w19] geepack,[w20] mice [w14] and dplyr [w21] packages.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Characteristics of participants (prestandardisation)

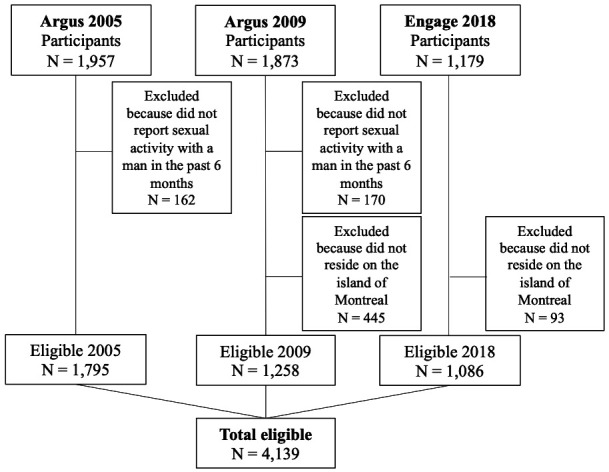

A total of 4139 MSM were included in our analyses (1795 in 2005; 1258 in 2009; 1086 in 2018) (figure 1). The pre-standardised proportion of participants living with HIV was 13% (95% CI 11% to 14%) in 2005, 15% (95% CI 13% to 17%) in 2009 and 18% (95% CI 16% to 21%) in 2018 (table 1). Unadjusted HCV antibody prevalence was 5% in 2005, 4% in 2009 and 5% in 2018. The raw percentage of participants with a history of IDU was 7% (95% CI 6% to 8%) in 2005, 12% (95% CI 10% to 14%) in 2009 and 10% (95% CI 8% to 12%) in 2018.

Figure 1.

Study eligibility flow chart. Individuals missing values on any eligibility criteria were excluded from our analyses.

Table 1.

Description of participants included in three cross-sectional biobehavioural surveys of men who have sex with men conducted in Montréal, Québec (Canada) (2005–2018, before any imputation or standardisation)

| Characteristics | 2005 | 2009 | 2018 |

| (n=1795) | (n=1258) | (n=1086) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| HCV seropositivity | 95 (5) | 49 (4) | 58 (5) |

| HIV seropositivity | 224 (13) | 193 (15) | 200 (18) |

| Reactive syphilis serology | 93 (5) | 116 (9) | 194 (18) |

| Age | 38 (28–47)* | 40 (30–47)* | 34 (28–49)* |

| Income ≥$C30 000 in the past year | 891 (50) | 763 (61) | 461 (42) |

| Education level higher than high school | 1217 (68) | 537 (43) | 806 (74) |

| Sexual orientation other than gay/homosexual | 336 (19) | 107 (9) | 205 (19) |

| Born outside of Canada | 244 (14) | 194 (15) | 348 (32) |

| Self-reported ethnicity or family background | |||

| Indigenous | 33 (2)† | 16 (1) | 9 (1) |

| English Canadian | 146 (8)† | 108 (9) | 103 (9) |

| French Canadian | 1219 (68)† | 865 (69) | 537 (49) |

| European | 105 (6)† | 119 (9) | 157 (14) |

| Asian | 31 (2)† | 14 (1) | 40 (4) |

| Arab or North African | 28 (2)† | 20 (2) | 44 (4) |

| Sub-Saharan African | 3 (<1)† | 3 (<1) | 9 (1) |

| Latin, South or Central American | 60 (3)† | 29 (2) | 92 (8) |

| Caribbean | 20 (1)† | 7 (1) | 9 (1) |

| Oceanian (eg, Australian, Pacific Islander) | 2 (<1)† | 0 | 1 (<1) |

| Other | 84 (5)† | 61 (5) | 74 (7) |

| First language other than French/English | 125 (7) | 101 (8) | 74 (7) |

| Transactional sex in the P6M‡ | 329 (18)† | 187 (15)† | 108 (10) |

| CAS with a man of serodiscordant/unknown HIV status in the P6M | 200 (11)† | 251 (20)† | 395 (36)† |

| >5 male sexual partners in the P6M§ | 664 (37) | 569 (45) | 533 (51) |

| Group sex in the P6M | 479 (27) | 407 (32)† | 252 (23) |

| History of injection drug use¶ | 128 (7)† | 147 (12) | 110 (10) |

*Median (IQR).

†More than 2% of observations were missing for this variable, in this data set.

‡Transactional sex was defined as having given/received money, drugs, or other goods or services in exchange for sex in the P6M.

§Male sexual partners included both oral and anal sexual partners.

¶Lifetime injection of any non-prescribed drug was considered as a previous experience of injection drug use.

CAS, condomless anal sex; HCV, hepatitis C virus; P6M, past 6 months.

Temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence (poststandardisation)

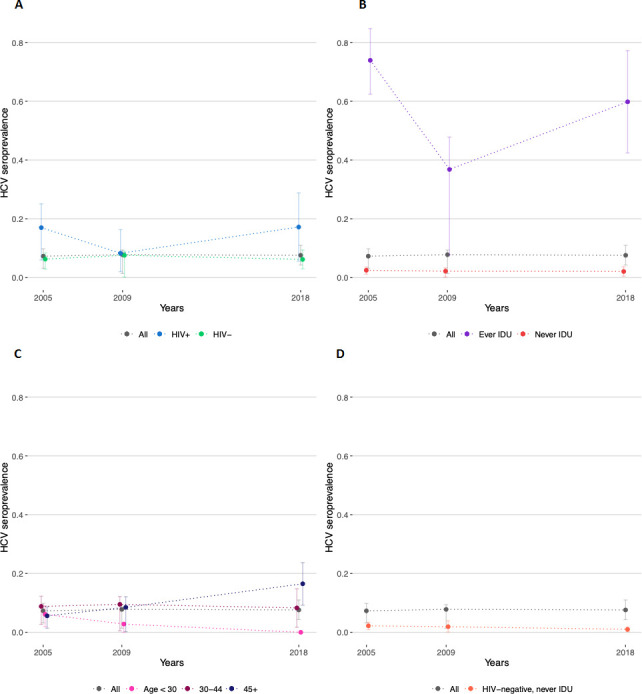

Standardised HCV seroprevalence among all MSM remained stable, ranging from 7% (95% CI 3% to 10%) in 2005, to 8% (95% CI 1% to 9%) in 2009 and 8% (95% CI 4% to 11%) in 2018 (figure 2, online supplementary file 3).

Figure 2.

HCV seroprevalence estimates among gay, bisexual and other MSM overall and stratified by (A) HIV status, (B) lifetime history of IDU, (C) age group and (D) HIV-negative MSM without history of IDU in 2005, 2009 and 2018 in Montréal, Québéc (Canada). HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDU, injection drug use; MSM, men who have sex with men.

Stratification by HIV and IDU status did not reveal consistent temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence among these subgroups. We observed a drop in estimates for MSM living with HIV and MSM with a history of IDU in 2009 and obtained relatively wide CIs among these two groups due to smaller numbers of observations. The highest HCV seroprevalence point estimates were obtained among participants with a history of IDU, with 74% (95% CI 62% to 85%) in 2005, 37% (95% CI 8% to 48%) in 2009 and 60% (95% CI 42% to 77%) in 2018. In contrast, HCV seroprevalence among MSM without a history of IDU was estimated at 3% (95% CI 1% to 4%) in 2005, 2% (95% CI 0% to 3%) in 2009 and 2% (95% CI 1% to 4%) in 2018. HCV seropositivity was also far more common among MSM living with HIV at 17% (95% CI 6% to 25%) in 2005, 8% (95% CI 2% to 16%) in 2009 and 17% (95% CI 6% to 29%) in 2018, than among HIV-negative MSM at 6% (95% CI 3% to 8%) in 2005, 8% (95% CI 0% to 9%) in 2009 and 6% (95% CI 3% to 9%) in 2018. Finally, HCV seroprevalence remained relatively stable among HIV-negative MSM without a history of IDU at 2% (95% CI 1% to 3%) in 2005, 2% (95% CI 0% to 4%) in 2009 and 1% (95% CI 0% to 2%) in 2018.

When stratifying by age group, we observed a decrease in HCV seroprevalence among MSM <30 years old over time, from 6% (95% CI 2% to 9%) in 2005, to 3% (95% CI 0% to 3%) in 2009 and 0% (95% CI 0% to 1%) in 2018. We noted no clear temporal trend in HCV seroprevalence among MSM aged 30–44 years (9%, 95% CI 3% to 12% in 2005; 10%, 95% CI 1% to 12% in 2009; and 8%, 95% CI 2% to 15% in 2018). Among MSM aged ≥45 years, HCV seroprevalence increased from 6% (95% CI 1% to 9%) in 2005, to 9% (95% CI 0% to 12%) in 2009 and to 17% (95% CI 9% to 24%) in 2018.

Factors associated with HCV seropositivity

Lifetime history of IDU was the strongest predictor of HCV seropositivity in our population (table 2). Increased age, recent transactional sex, HIV seropositivity and sexual orientation other than gay/homosexual were also associated with increased HCV seroprevalence. Our results suggest an association between socioeconomic factors and the outcome: MSM with higher income and education level were less likely to test HCV-seropositive. Being born outside of Canada was also associated with lower HCV seroprevalence. Few participants identified as Indigenous (1%–2% across surveys), leading to wide uncertainty around the adjusted prevalence ratio for this population group. We found no association between the recent sexual behaviours examined and HCV seropositivity. Finally, first language other than French/English was not associated with variation in the outcome.

Table 2.

HCV seroprevalence ratios obtained by pooling three cross-sectional surveys of men who have sex with men conducted in Montréal, Québec (Canada) (2005, 2009, 2018)

| Covariates | Univariable prevalence ratio (95% CI) | Multivariable prevalence ratio (95% CI) |

| History of IDU | 18.2 (12.2 to 27.2) | 8.0 (5.5 to 11.5) |

| Age | ||

| <30 | 1 | 1 |

| 30–44 | 2.1 (1.4 to 3.2) | 2.2 (1.5 to 3.3) |

| ≥45 | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.1) | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.9) |

| Transactional sex (P6M) | 4.6 (3.0 to 7.1) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.5) |

| HIV seropositivity | 2.9 (1.8 to 4.8) | 1.7 (1.3 to 2.3) |

| Sexual orientation other than gay/homosexual | 5.4 (3.2 to 9.2) | 1.6 (1.3 to 2.1) |

| Income ≥$C30 000 in the past year | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.7) |

| Born outside of Canada | 0.2 (0.0 to 0.6) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) |

| Year of data collection | ||

| 2005 | 1 | 1 |

| 2009 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.8) | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.8) |

| 2018 | 0.9 (0.3 to 2.4) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) |

| Education level higher than high school | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.3) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.6) |

| Self-identified Indigenous ethnicity or family background | 1.1 (0.1 to 23.7) | 1.4 (0.4 to 4.5) |

| Reactive syphilis serology | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.9) | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.6) |

| First language other than French/English | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| >5 male sexual partners (P6M) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.3) |

| Group sex in the P6M | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) |

| CAS with a man of serodiscordant/unknown HIV status (P6M) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.6) | 0.7 (0.5 to 1.1) |

CAS, condomless anal sex; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IDU, injection drug use; P6M, past 6 months.

Sensitivity analyses

We detected negative additive and multiplicative interactions between HIV seropositivity and transactional sex in the P6M (online supplementary file 4). The presence of negative additive and multiplicative interactions means that the association with HCV seropositivity when both factors are present is smaller than, respectively, the sum and product of the individual associations of the two factors with the outcome. We also identified negative additive interactions between history of IDU and each sexual risk factor studied, separately, and a positive multiplicative interaction between history of IDU and group sex in the P6M. A positive multiplicative interaction indicates that the association when both factors are present is stronger than the product of the individual associations.

Discussion

Standardising and pooling three large cross-sectional surveys of MSM from 2005 to 2018, our results suggest that HCV seroprevalence has remained stable around 8% in Montréal, at a higher level than in other North American settings (3%–5%).12 [w22, w23] Despite this overall stability, we observed diverging trends among age groups. Monitoring changes in HCV seroprevalence among young adults has been used to gauge trends in HCV incidence in the general population.3 The decrease observed in HCV seroprevalence among younger participants may therefore indicate a decline in new HCV infections among MSM from 2005 to 2018. In contrast, the increase in HCV seroprevalence among MSM aged ≥45 years may reflect birth cohort effects (ie, men born between 1945 and 197522), temporal changes in injecting and/or sexual behaviours among older MSM, or changes in intergenerational transmission of HCV over time.

HCV seroprevalence was particularly high among MSM living with HIV and those with a history of IDU. The drop in seroprevalence observed in 2009 among these groups could indicate temporal changes in injecting behaviours (eg, increased number of new injectors never exposed to HCV). However, these results could reflect remaining differences in the composition of the samples post-standardisation. HCV seroprevalence among HIV-negative MSM in Montréal ranged from 6% to 8% between 2005 and 2018, on the high end of estimates from Canada,13 the USA[w23] and Europe.10 The seroprevalence estimated among MSM without a history of IDU (2%–3%) was also twice as high as that estimated in Vancouver for the same group.12 These numbers are greater than the 1% HCV seroprevalence estimated for the general Canadian population.[w24] Yet, the seroprevalence observed among HIV-negative MSM without a history of IDU (1%–2%) was comparable with that among the general population, in line with previous findings from Argus 1.[w25] The relatively high HCV seroprevalence observed among all MSM may therefore reflect frequent exposure to the virus among subgroups with particular vulnerabilities (eg, HIV infection) or risk behaviours (eg, IDU).

Reporting a history of IDU was the strongest predictor of HCV seropositivity among Montréal MSM between 2005 and 2018. This is concerning given that the proportion of MSM who reported lifetime IDU in Engage (6%[w2]) is 12 times that reported among the general population in Montréal (0.5%[w26]). Aside from recent transactional sex, which encompasses having given/received drugs in exchange for sex, we observed no association between sexual behaviours and HCV seroprevalence. These results are consistent with those obtained in Toronto13 and a study conducted in 2001 among Montréal MSM.29 However, they contrast with emerging evidence from Vancouver17 and with studies conducted in Europe6 and the USA,14 where sexual risk factors were strongly associated with new HCV infections among MSM.

We observed no positive interactions between HIV positivity and sexual behaviours. One potentially important risk factor that we could not directly investigate is chemsex. Nevertheless, the positive multiplicative interaction observed between group sex and IDU could partly capture the association of chemsex practices with HCV seroprevalence, although we could not measure the concomitance of injecting and sexual behaviours. No positive interaction was observed between history of IDU and other sexual risk factors.

Altogether, higher socioeconomic status (ie, income and education) was associated with lower HCV seroprevalence. Our data did not allow us to specifically examine the relationship between birth in HCV endemic countries and HCV seropositivity. In this regard, interpreting the negative association between birth outside of Canada and HCV seroprevalence is challenging. Having a first language other than French/English, another proxy for country of origin, was not associated with the outcome. Reporting a sexual orientation other than gay/homosexual was positively associated with HCV seropositivity. Because data on sexual orientation were categorised differently across our three surveys, the ‘other’ category represents varied self-reported sexual orientations (bisexual, heterosexual and queer). Few studies have examined the distribution of sexually transmitted and bloodborne infections by sexual orientation among MSM populations.[w27–w29] Understanding these complex links remains challenging and studies did not consistently identify groups most at risk or with unmet prevention needs.

Our results should be interpreted considering the study’s main limitations. First, cross-sectional data render the interpretation of observed associations challenging due to temporality bias. However, pooling the available data allowed us to produce robust, comparable estimates of HCV exposure across time and to investigate the plausibility of different modes of transmission of the virus among these groups. Second, we could not investigate the relationship between lifelong sexual practices and HCV seropositivity due to data limitations. Yet we could quantify the adjusted association of numerous recent sexual behaviours with HCV exposure.

Strengths of this study include its large sample size, resulting from the pooling of three comparable surveys. To maximise internal validity, we standardised our three samples on variables whose distributions should have remained relatively stable over time. Although generalisability to the target population cannot be directly assessed, we used the community-based, RDS-adjusted Engage sample as a standard. Additionally, recent epidemiological data on HCV exposure and determinants among MSM living in Montréal are lacking, and very few population-based studies have examined HCV prevalence trends among MSM subgroups globally. As such, our work provides a unique opportunity to inform local public health interventions. Canadian guidelines recommend HCV screening among people born from 1945 to 1975, with a history of IDU and/or living with HIV, and treatment for all chronically infected people.[w30] In addition, specific efforts should be directed towards understanding and reducing harms associated with IDU practices among MSM.

Conclusions

HCV seroprevalence remained high among Montréal MSM between 2005 and 2018, likely reflecting frequent exposure to the virus among MSM living with HIV and MSM with a history of IDU. Unlike other settings where HCV infection was strongly associated with sexual risk factors among MSM subgroups, history of IDU was the pre-eminent risk factor for HCV seropositivity among Montréal MSM. Understanding the intersection of IDU contexts, practices and populations is essential to prevent HCV transmission among these overlapping populations.

Key messages.

Standardised hepatitis C virus (HCV) seroprevalence remained stable at approximately 8% among Montréal men who have sex with men (MSM) from 2005 to 2018.

We observed diverging temporal trends in HCV seroprevalence across age groups, with a decrease among men <30 years and an increase among men aged ≥45 years.

Lifetime history of injection drug use was the pre-eminent risk factor for HCV seropositivity among MSM living in Montréal.

Recent sexual behaviours did not exhibit strong associations with HCV exposure in our population.

sextrans-2020-054464supp002.pdf (45.3KB, pdf)

Acknowledgments

The principal investigators of Argus are Michel Alary, Chris Archibald, Joseph Cox, Louis-Robert Frigault, Marc-André Gadoury, Gilles Lambert, René Lavoie, Robert Remis, Paul Sandstrom, Cécile Tremblay, François Tremblay and Jon Vincelette. We would like to thank all men who agreed to participate in the Argus surveys, as well as the owners and managers of the establishments where the participants were recruited. We would also like to thank the gay community organisations in Montréal who supported this research. The principal investigators of Engage are Joseph Cox, Daniel Grace, Trevor Hart, Jody Jollimore, Nathan Lachowsky, Gilles Lambert and David Moore. We would like to thank all the Engage participants, the community engagement committee members and the affiliated community agencies.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Anna Maria Geretti

Twitter: @NJLachowsky

Contributors: CLD, JC, MK and MM-G conceived and designed the study. JC and GL were involved in the study design and data collection of the Argus 1 and 2 surveys. JC, GL, DG and NJL were involved in the study design and data collection of the Engage study. CLD administered and processed the different databases. CLD performed the statistical analyses with inputs from MK and MM-G. All authors contributed to results interpretation. CLD drafted the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed it for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The Argus surveys were funded by the Institut national de santé publique du Québec and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Engage is funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for AIDS Research, and the Ontario HIV Treatment Network. CLD received a PhD trainee fellowship from the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C. The Canadian Network on Hepatitis C is funded by a joint initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (NHC-142832) and the Public Health Agency of Canada. CLD also received a doctoral training award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. MK is supported by a Tier I Canada Research Chair. MM-G’s research programme is funded by a career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé. The authors thank the Réseau de recherche en santé des populations du Québec (RRSPQ) for its contribution to the financing of this publication.

Competing interests: JC has received research grant funding from Gilead Sciences, Merck Canada and ViiV Healthcare. He also received travel support and honoraria for advisory work from Gilead Sciences, Merck Canada and ViiV Healthcare. MK reports grants for investigator-initiated studies from ViiV Healthcare, Merck and Gilead; research grants from Janssen; and personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie and Gilead, all outside the submitted work. MM-G reports grant funding from Gilead Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Deidentified participant data used in this analysis are stored at the Direction régionale de santé publique Montréal and BCCfE. For information regarding these databases, and related access, please contact JC (joseph.cox@mcgill.ca; ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7041-1556), a principal investigator on both studies.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The research ethics board of the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Center approved all three surveys (Argus ethics committee number: A10-M66-04B; Engage ethics committee number: MP-CUSM-15-632).

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030: advocacy brief. World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Waheed Y, Siddiq M, Jamil Z, et al. Hepatitis elimination by 2030: progress and challenges. World J Gastroenterol 2018;24:4959–61. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i44.4959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. The Canadian Network on Hepatitis C Blueprint Writing Committee and Working Groups . Blueprint to inform hepatitis C elimination efforts in Canada. Canadian Network on Hepatitis C, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lazarus JV, Wiktor S, Colombo M, et al. Micro-elimination - A path to global elimination of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2017;67:665–6. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lazarus JV, Safreed-Harmon K, Thursz MR, et al. The micro-elimination approach to eliminating hepatitis C: strategic and operational considerations. Semin Liver Dis 2018;38:181–92. 10.1055/s-0038-1666841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hagan H, Jordan AE, Neurer J, et al. Incidence of sexually transmitted hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-positive men who have sex with men. AIDS 2015;29:2335–45. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ghisla V, Scherrer AU, Nicca D, et al. Incidence of hepatitis C in HIV positive and negative men who have sex with men 2000-2016: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infection 2017;45:309–21. 10.1007/s15010-016-0975-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:797–808. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00485-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Han R, Zhou J, François C, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C infection among the general population and high-risk groups in the EU/EEA: a systematic review update. BMC Infect Dis 2019;19:655. 10.1186/s12879-019-4284-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newsum AM, van Rooijen MS, Kroone M, et al. Stable low hepatitis C virus antibody prevalence among HIV-negative men who have sex with men attending the sexually transmitted infection outpatient clinic in Amsterdam, 2007 to 2017. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45:813–7. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Falla AM, Hofstraat SHI, Duffell E, et al. Hepatitis B/C in the countries of the EU/EEA: a systematic review of the prevalence among at-risk groups. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:79. 10.1186/s12879-018-2988-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wong J, Moore D, Kanters S, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C and correlates of seropositivity among men who have sex with men in Vancouver, Canada: a cross-sectional survey. Sex Transm Infect 2015;91:430–3. 10.1136/sextrans-2014-051928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Remis RS, Liu J, Loutfy MR, et al. Prevalence of sexually transmitted viral and bacterial infections in HIV-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men in Toronto. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158090. 10.1371/journal.pone.0158090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jin F, Matthews GV, Grulich AE. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among gay and bisexual men: a systematic review. Sex Health 2017;14:28–41. 10.1071/SH16141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McFaul K, Maghlaoui A, Nzuruba M, et al. Acute hepatitis C infection in HIV-negative men who have sex with men. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:535–8. 10.1111/jvh.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infections among users of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1728–9. 10.1093/cid/civ129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lachowsky N, Stephenson K, Cui Z, et al. Prevalence and factors of HCV infection among HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM [abstract]. Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization . Global hepatitis report. WHO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Breskin A, Drobnik A, Pathela P, et al. Factors associated with hepatitis C infection among HIV-infected men who have sex with men with no reported injection drug use in New York City, 2000-2010. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42:382–6. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Danta M, Brown D, Bhagani S, et al. Recent epidemic of acute hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive men who have sex with men linked to high-risk sexual behaviours. AIDS 2007;21:983–91. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281053a0c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Witt MD, Seaberg EC, Darilay A, et al. Incident hepatitis C virus infection in men who have sex with men: a prospective cohort analysis, 1984-2011. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:77–84. 10.1093/cid/cit197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Trubnikov M, Yan P, Njihia J, et al. Identifying and describing a cohort effect in the National database of reported cases of hepatitis C virus infection in Canada (1991-2010): an age-period-cohort analysis. CMAJ Open 2014;2:E281–7. 10.9778/cmajo.20140041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Greenaway C, Thu Ma A, Kloda LA, et al. The seroprevalence of hepatitis C antibodies in immigrants and refugees from intermediate and high endemic countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141715. 10.1371/journal.pone.0141715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schmidt AJ, Falcato L, Zahno B, et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C in a Swiss sample of men who have sex with men: whom to screen for HCV infection? BMC Public Health 2014;14:3. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Saxton PJW, Hughes AJ, Robinson EM. Sexually transmitted diseases and hepatitis in a national sample of men who have sex with men in New Zealand. N Z Med J 2002;115:U106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen Y-C, Wiberg KJ, Hsieh Y-H, et al. Favorable socioeconomic status and recreational polydrug use are linked with sexual hepatitis C virus transmission among human immunodeficiency virus-infected men who have sex with men. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016;3:ofw137. 10.1093/ofid/ofw137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2019;63:74–89. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tomkins A, George R, Kliner M. Sexualised drug taking among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Perspect Public Health 2019;139:23–33. 10.1177/1757913918778872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alary M, Joly JR, Vincelette J, et al. Lack of evidence of sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus in a prospective cohort study of men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2005;95:502–5. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Myers T, Allman D, Xu K, et al. The prevalence and correlates of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and HCV–HIV co-infection in a community sample of gay and bisexual men. Int JInfec Dis 2009;13:730–9. 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.11.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sextrans-2020-054464supp001.pdf (180KB, pdf)

sextrans-2020-054464supp002.pdf (45.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Deidentified participant data used in this analysis are stored at the Direction régionale de santé publique Montréal and BCCfE. For information regarding these databases, and related access, please contact JC (joseph.cox@mcgill.ca; ORCID ID https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7041-1556), a principal investigator on both studies.