There are approximately 900,000 primary heart failure (HF) hospitalizations per year in the United States.1 Observational analysis of these hospitalizations could help clinical investigators improve care for patients with acute HF. However, research from electronic health records and administrative databases is often limited by a lack of specificity, which is especially true in HF where the use of nonspecific codes is frequent.2 Systolic and diastolic HFs affect different patient populations and have distinct treatment options; thus, failure to distinguish between types of HF limits the ability to study these diseases and assess risks factors, therapeutic effectiveness, and quality of care.

In October 2015, all health care facilities in the United States transitioned from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Edition (ICD-9) to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) for the coding of electronic health care transactions. The new classification system has almost 5 times as many diagnostic codes and thus allows for more detail and a more accurate reflection of disease severity. However, how this systematic switch from ICD-9 to ICD-10 has influenced the classification of HF admissions has not previously been elucidated.

We used the Premier Healthcare Database (Premier, Inc, Charlotte, NC) to assess how the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding affected the specificity of HF diagnoses for older hospitalized patients ≥75 years of age. The Premier Healthcare Database is a large, multicenter database of hospital encounters from more than 750 hospitals and health care systems in the United States. Since 2012, there have been more than 8 million inpatient admissions and 71 million outpatient visits per year included in the database, representing approximately 25% of all hospital admissions per year in the United States.3

For this analysis, we used hospital discharge data from the first quarter of each year from 2013 through 2018, representing 3 years prior to and 3 years following the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding. Of all hospitalizations with a primary (first coding position) or secondary (coding position 2-15) diagnosis that included HF (ICD-9 codes 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 428.X; ICD-10 code I50.X), we assessed the proportion (%) of admissions with specific coding for acute systolic HF (including acute systolic HF, acute on chronic systolic HF, acute combined systolic and diastolic HF, and acute on chronic combined systolic and diastolic HF [ICD-9 codes 428.21, 428.23, 428.41, 428.43, respectively, and ICD-10 codes I50.21, I50.23, I50.41, I50.43]) and acute diastolic HF (including acute diastolic HF and acute on chronic diastolic HF [ICD-9 codes 428.31, 428.33, respectively, and ICD-10 codes I50.31, I50.33, respectively]).

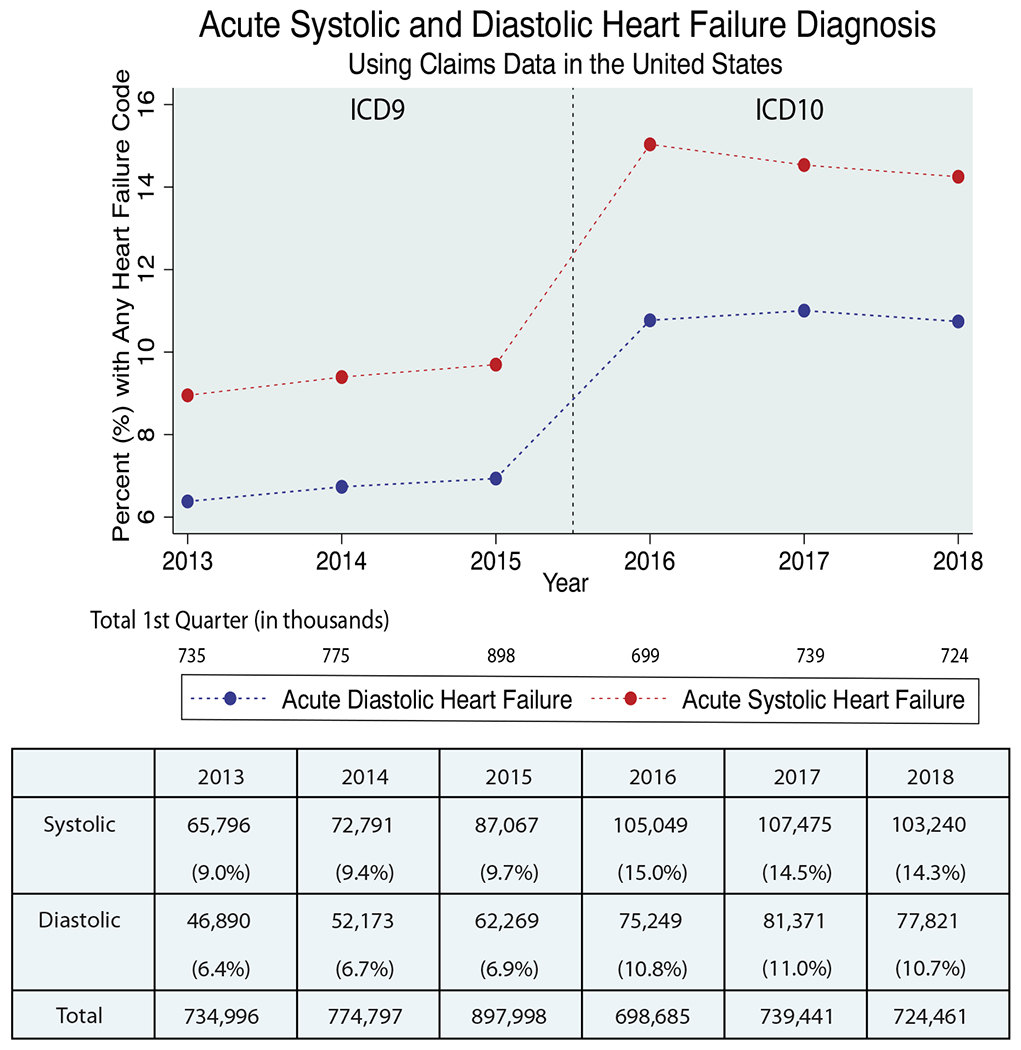

The number of first quarter HF hospitalizations was similar each year from 2013 through 2018, except for an increase in 2015. For the period between 2013 and 2015, 9.4% of hospitalizations with an HF diagnosis had specific coding for acute systolic HF and 6.7% for acute diastolic HF. Following the change to ICD-10 coding from 2016 to 2018, 14.6% were assigned a specific coding for acute systolic HF and 10.8% for acute diastolic HF. Therefore, although nonspecific codes were still used frequently, the change from ICD-9 to ICD-10 coding was associated with a ~50% increase in the use of specific administrative codes for acute HF (See Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Acute systolic and diastolic HF diagnosis using claims data in the United States. The figure illustrates the change in the specificity of HF diagnosis with the change of ICD-9 to ICD-10 within each first quarter of the years 2013 to 2018 (data source: Premier Healthcare Database).

The use of administrative claims data (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and others) for research is common and will only likely increase in the future. However, the questionable accuracy of the diagnostic codes used in these databases remains a significant limitation to their effective use in clinical research. For example, prior work has shown poor accuracy of ICD-9 codes, and the accuracy of ICD-10 codes has not yet been studied.2 Our study suggests that since the adoption of ICD-10 coding, there has been a notable increase in the use of distinct codes for acute systolic and diastolic HF. However, nonspecific codes continue to be used commonly. Continued improvement in specific code usage and coding accuracy will hopefully usher in a new era of HF outcomes research using data from electronic health records and administrative databases.

References

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019;139:e56–e528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidenreich PA, Natarajan S, Bahrami H. Accuracy of administrative coding to identify reduced and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. Journal of Cardiac Failure 2019;25:486–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Premier Healthcare Database white paper: data that informs and performs, July 29, 2018. Premier Applied Sciences®, Premier Inc. https://learn.premierinc.com/white-papers/premier-healthcaredatabase-whitepaper. [Google Scholar]