Abstract

Cryptococcosis is an invasive infection that accounts for 15% of AIDS-related fatalities. Still, treating cryptococcosis remains a significant challenge due to the poor availability of effective antifungal therapies and emergence of drug resistance. Interestingly, protease inhibitor components of antiretroviral therapy regimens have shown some clinical benefits in these opportunistic infections. We investigated Major aspartyl peptidase 1 (May1), a secreted Cryptococcus neoformans protease, as a possible target for the development of drugs that act against both fungal and retroviral aspartyl proteases. Here, we describe the biochemical characterization of May1, present its high-resolution X-ray structure, and provide its substrate specificity analysis. Through combinatorial screening of 11,520 compounds, we identified a potent inhibitor of May1 and HIV protease. This dual-specificity inhibitor exhibits antifungal activity in yeast culture, low cytotoxicity, and low off-target activity against host proteases and could thus serve as a lead compound for further development of May1 and HIV protease inhibitors.

Introduction

Cryptococcus neoformans, along with Cryptococcus gattii, is one of the two major basidiomycetes yeasts responsible for cryptococcosis,1 a life-threatening systemic mycosis that frequently occurs in immunosuppressed patients, chiefly in cases of HIV infection.2,3 Cryptococcosis, typically environmentally acquired by inhalation of basidiospores,4 can lead to fatal cryptococcal meningitis even in immunocompetent patients.5−7

More than 1 million cases of cryptococcosis are reported each year worldwide, with an estimated annual death toll of 181,100,8 accounting for 15% of AIDS-related fatalities.9 The World Health Organization recommends combination therapy with amphotericin B and flucytosine followed by fluconazole for management of cryptococcosis.10 However, this approach has been hampered by shortages of key regimen components (recently fluconazole11), the general inaccessibility of effective therapeutics in developing areas,12 and a rapid increase in incidence of multidrug-resistant pathogenic fungi.13,14 Cryptococcus mutants resistant to individual components of the regimen—amphotericin B,15 flucytosine,16 and fluconazole17 —have been identified, and the emergence of complete cross-resistance is a possible threat.18

As these medications represent the three chief classes of approved antifungals currently used in clinical practice,19 advances in development of novel antifungals are of utmost importance. Focus should be placed on the large population of HIV patients with Cryptococcus coinfections to maximize the availability of treatment regimens and minimize the patients’ already high pill burden.20

One potential solution is the development of HIV-1 protease (HIV-1 Pr) inhibitors that also target vital fungal proteases, which often serve critical roles in survival, reproduction, and host tissue invasion.21,22 We set out to characterize C. neoformans Major aspartyl peptidase 1 (May1,23 CnAP124) as a possible target for antifungal therapy,23 search for novel aspartyl protease inhibitor motifs, and examine their structure–activity relationship based on X-ray structures of May1 alone and in complex with the model inhibitor pepstatin A.

May1 is one of many proteases in the C. neoformans secreted proteome, members of which serve diverse functions, including virulence modulation,25,26 host tissue invasion,27 dissemination to the central nervous system,28 and nitrogen assimilation.29,30 May1 is a secreted fungal pepsin-like acidic endopeptidase24 with a broad substrate preference for hydrolysis between hydrophobic residues required for high-density growth under acidic conditions. Experiments in a mouse inhalation model of infection established that May1 is required for fungal virulence.23

The HIV-1 Pr inhibitors saquinavir, darunavir, ritonavir, and indinavir can affect production of important C. neoformans virulence factors.25,31 Similarly, the protease inhibitors indinavir, ritonavir, and pepstatin A inhibit growth of Candida albicans under nitrogen-limited conditions.32 People with HIV who have had cryptococcal meningitis have a lower risk of cryptococcosis relapse while taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimens including protease inhibitors, even without direct antifungal maintenance.33 A similar phenomenon has been hypothesized for C. albicans infections.34 These observations formed our basic rationale for exploring May1 as a possible secondary target of components of HIV-1 Pr inhibitor regimens as well as a direct target for antifungal drug development.

Results

Expression and Characterization of Recombinant May1

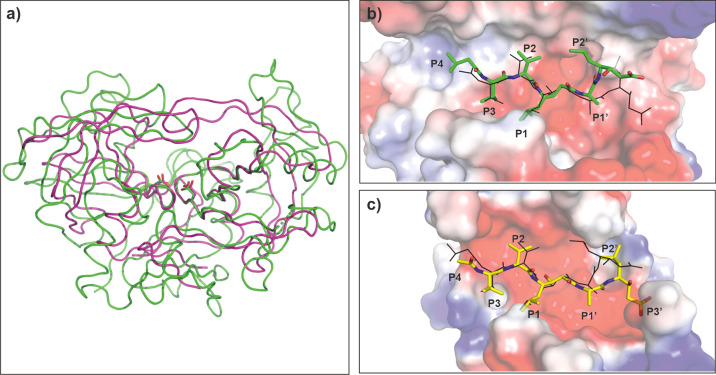

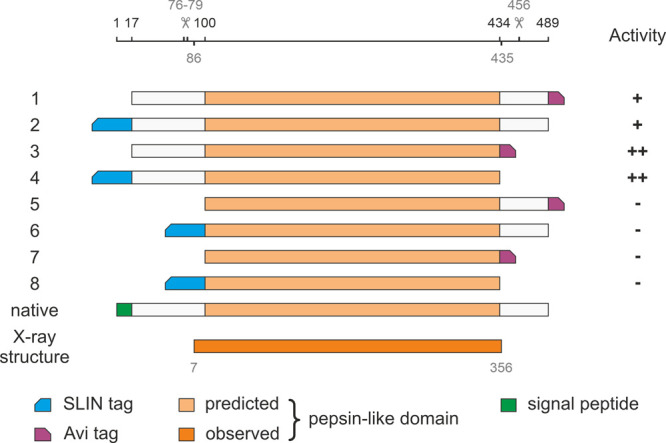

Full-length C. neoformans var. grubii H99 May1 is a 489 amino acid long, multi-domain enzyme encoded by the gene cnap1 (CNAG_05872). To prepare a recombinant protein for subsequent biochemical and structural characterization, we designed a series of C. neoformans May1 constructs with N/C-terminal purification tags for recombinant expression in Drosophila S2 cells. The constructs span different regions of the protein according to the predicted architecture35 shown in Figure 1. The 17 N-terminal amino acids, forming a putative native secretion signal,36 were replaced with a secretion signal compatible with the Drosophila expression system.

Figure 1.

Diagram of constructs used to identify May1 architecture and optimize expression strategy. Residue numbers indicate construct boundaries. The first 17 N-terminal amino acids, forming a putative native secretion signal, were replaced with a secretion signal compatible with the S2 expression system (not shown for clarity). Beveled rectangles denote positions of affinity tags used for purification.

We evaluated enzymatic activity using a fluorometric assay with the internally quenched fluorogenic substrate IQ-2 [AMC-GSPAF*LAK(DNP)dR-NH2; May1 cleaves between the phenylalanine and leucine residues.23 Activity assays using IQ-2 confirmed that May1 is activated upon autoproteolytic cleavage of the prodomain37 and that the presence of the prodomain in the construct is necessary to retain activity. Interestingly, mass spectrometry analysis indicated promiscuous autoproteolytic cleavages from residue 76 to residue 79 (Figure S1a). The presence of the C-terminal domain (downstream from residue 434) decreased the enzymatic activity. This domain was cleaved at residue 456 at the pH optimum of the protease, hinting at a possible regulatory or other function. The C-terminal cleavage site does not appear to be directly sequence-dependent, as constructs with different tags and multiple adaptor sequences (Strep-tag, Avi-tag, and His-tag) all underwent autocatalytic processing. The C-terminal purification tag required a thorough sequence optimization, which finally yielded a construct with a stable C-terminal biotinylation site (Avi-tag; construct 3 in Figure 1).

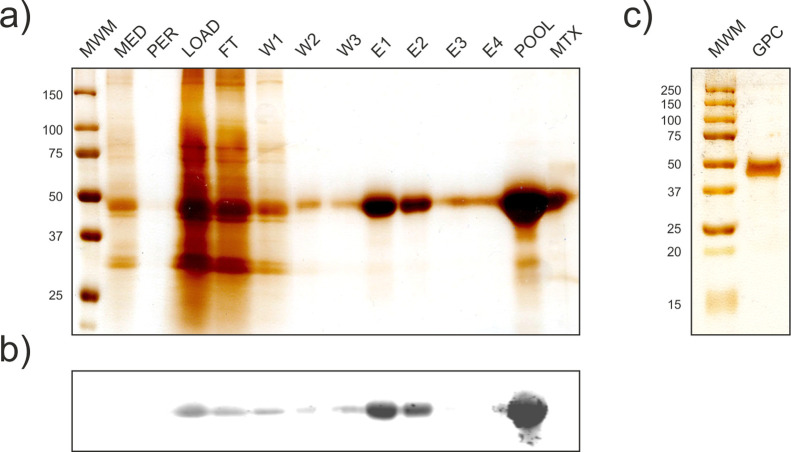

To obtain a sufficient quantity and purity of May1 for biochemical characterization, we conducted large-scale expression of construct 3 [May1(17-434)-Avi]. The recombinant protein was purified by affinity chromatography and size exclusion chromatography. Overall, 3 L of S2 culture media yielded 15 mg of monodisperse recombinant enzyme that was >95% pure according to SDS-PAGE (Figure 2) with an apparent molecular weight of 45 kDa. The mass spectrum shows multiple peaks with a dominant mass of 40,830 Da (Figure S1b). This value is larger than the theoretically largest possible average molecular weight of 40,145 Da (residues 77-434, including C-terminal tag and its biotinylation), which together with the broad peak distribution indicates that the protein undergoes glycosylation. The enzyme concentration and purity were further evaluated by amino acid analysis and active site titration.

Figure 2.

Analysis of May1(17-434)-Avi expression and purification. (a) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE of samples collected throughout the purification process. MED, crude S2 media; PER, permeate from media concentration; LOAD, concentrated filtrate; FT, flow-through; W1-3, wash fractions; E1-4, elution fractions; POOL, pooled concentrated elution fractions; MTX, matrix binding control. (b) Western blot analysis with the same layout as in a visualized using Streptavidin-800CW (LI-COR, 1:15,000). (c) Silver-stained SDS-PAGE of concentrated pooled fractions after size exclusion chromatography.

Once the expression protocol was established, kinetic assay conditions were optimized to enable the design of a combinatorial screening assay. May1 exhibits optimal activity at pH 5.0, consistent with other members of the pepsin-like aspartyl protease family.37 Ionic strength does not affect enzyme activity in the near-isotonic range (see Figure S2). The enzyme does not significantly lose activity in <0.5% Triton X-100 and Tween-20 or <5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (data not shown).

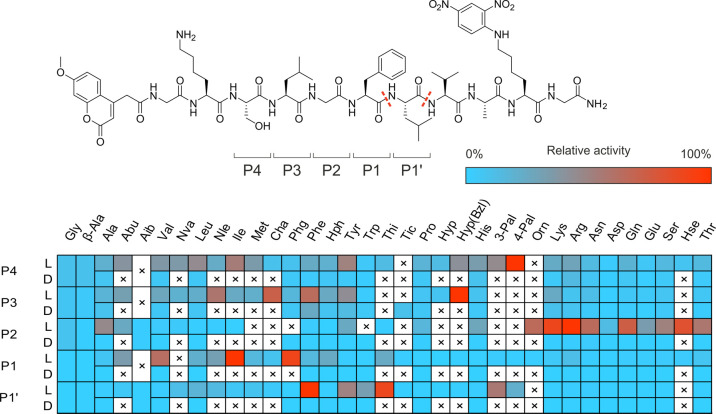

Substrate Specificity of May1

May1 exhibits a substrate preference for aromatic and positively charged residues at the P3–P1 and P1′ positions,23 like many proteases of the pepsin-like family.37 To gain broader structural insight into the substrate specificity of the enzyme, we evaluated its ability to cleave an internally quenched fluorescent substrate library with a general structure of ACC-GKSLGFLVAK(DNP)G-NH2. In the presumed P4–P1′ positions, we incorporated natural and unnatural amino acids (ACC-GK-P4-P3-P2-P1-P1′VAK(DNP)G-NH2). Library screening revealed that phenylalanine and its derivatives (Phe-3F, Phe-3Cl) and Ala(2-thienyl) were preferred amino acids at the P1′ position. Hydrophobic residues were favored at the P1 position [relative activity: Ile (100%), Phg (90%), Val (63%), Chg (38%), Abu (34%), Nle (32%)] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Substrate specificity profile of May1 at the P4–P1′ positions presented as a heat map. L and D rows indicate the amino acid enantiomer at a given position. Dashed lines indicate substrate cleavage sites detected by LC–MS, with the most abundant N-proximal Phe*Leu site selected as a residue numbering reference.

Positively charged amino acids were preferred in the S2 pocket [Arg (100%), Lys (89%), Orn (65%)]. This pocket also was able to accommodate polar, uncharged residues including hSer, Cit, Thr, and Ser. May1 favored hydrophobic amino acids at the P3 and P4 positions. Interestingly, in addition to the expected processing at P1–P1′ (Phe–Leu), we also observed substrate cleavage at P1′–P2′ (Leu–Val), suggesting some degree of catalytic promiscuity.

May1 Inhibition by Candidate and Clinically Used Protease Inhibitors

To further investigate the biochemical basis of reports that HIV-1 Pr inhibitor regimens lower relapse rates of cryptococcal meningitis33 and to explore a possible link of this phenomenon to May1 activity, we screened all protease inhibitors currently used in ART regimens38 to assess their inhibitory activity against May1 and validate previously published results.23

Only two such protease inhibitors exhibited detectable inhibitory activity against May1: amprenavir (Ki = 750 ± 320 nM) and ritonavir (Ki = 1.8 ± 0.5 μM). We also screened an extended panel of candidates and discontinued HIV-1 Pr inhibitors. CGP53437 (discontinued at phase I, Novartis39), GS-8374 (discontinued at a preclinical stage, Gilead40), and brecanavir (discontinued at phase II, GlaxoSmithKline41) inhibited May1 with Ki values of 13 ± 10, 170 ± 10, and 350 ± 20 nM, respectively. The relatively high Ki values of amprenavir and ritonavir do not support the notion that May1 inhibition is a major biochemical mechanism underlying the beneficial effect of HIV-1 Pr inhibitors in preventing cryptococcal meningitis, suggesting an alternative mode of action for these protease inhibitors.

Crystal Structure of May1

We crystallized a May1 construct spanning residues 17 to 434 with a C-terminal Avi tag both in free form and in complex with pepstatin A (PepA), an aspartyl protease inhibitor reported to inhibit May1.23,24 We verified that May1(17-434)-Avi is inhibited by both PepA and acetyl pepstatin with Ki values of 1.3 ± 0.1 and 3.3 ± 0.1 nM, respectively.

Diffraction data for May1 and the May1–PepA complex were collected to maximal resolutions of 1.75 and 1.8 Å, respectively. The May1 crystal structure was determined by molecular replacement using the structure of human renin42 as a model. The centered orthorhombic crystal contained 63% solvent and one protein molecule per asymmetric unit, representing a monomeric biological unit. Residues 86-435 were modeled into the electron density map and numbered 7-356 starting with the N-terminus generated upon cleavage at position 79. The structure revealed that the boundary of the pepsin-like domain is shifted by four residues toward the N-terminus compared to the predicted one (Figure 1). No electron density was observed for N-terminal residues 80–85 or the C-terminal Avi tag; residue 356 in the crystal structure represents a cloning artifact. Additional residues that were not modeled in the May1–PepA crystallographic model include residues 226–236 that belong to a surface-exposed loop with poor electron density. Both structures contain a glycosylated asparagine at position 187, modeled as GlcNAc-β(1 → 4)GlcNAc-β-Asn187.

As previously predicted by homology modeling,24 May1 adopts a renin fold, which is a predominantly β-sheet conformation characteristic of the aspartyl proteinase family.43 The substrate binding cleft and active site are at the junction of two structurally similar domains of approximately equal size.44 The catalytic residues, Asp40 and Asp238, are located centrally in the cleft (Figure 4) with the carboxyl side chains and surrounding main chain scaffolding related by an approximate twofold interdomain axis.43,45,46

Figure 4.

(a) Crystal structure of recombinant May1 in free form (PDB 6R5H). The catalytic Asp residues are highlighted as magenta sticks. (b) Superposition of May1 (green) with human renin (magenta, PDB code 2REN(42)).

Structural comparison with models deposited in the Protein Data Bank using the program DALI47,58 identified various aspartyl proteases as structural homologues of May1, with human renin being the closest homologue (the RMSD for Cα superposition of 232 residues was 1.5 Å). We also identified structural similarity to HIV-1 Pr48 despite its low sequence identity of 13% (the RMSD for Cα superposition of 175 residues was 3.2 Å).

PepA binds in the substrate binding groove of May1, and its central statine residue with a non-scissile bond acts as a tetrahedral transition-state mimic. The first five residues of the PepA molecule were modeled into a well-defined continuous electron density map. The ambiguous electron density map for the C-terminal part of the inhibitor can be explained by two equally occupied conformations of the terminal Sta residue (Figure 5a). The May1 structure does not change significantly upon PepA binding; the RMSD for superposition of the free and complexed May1 structures was 0.129 Å.

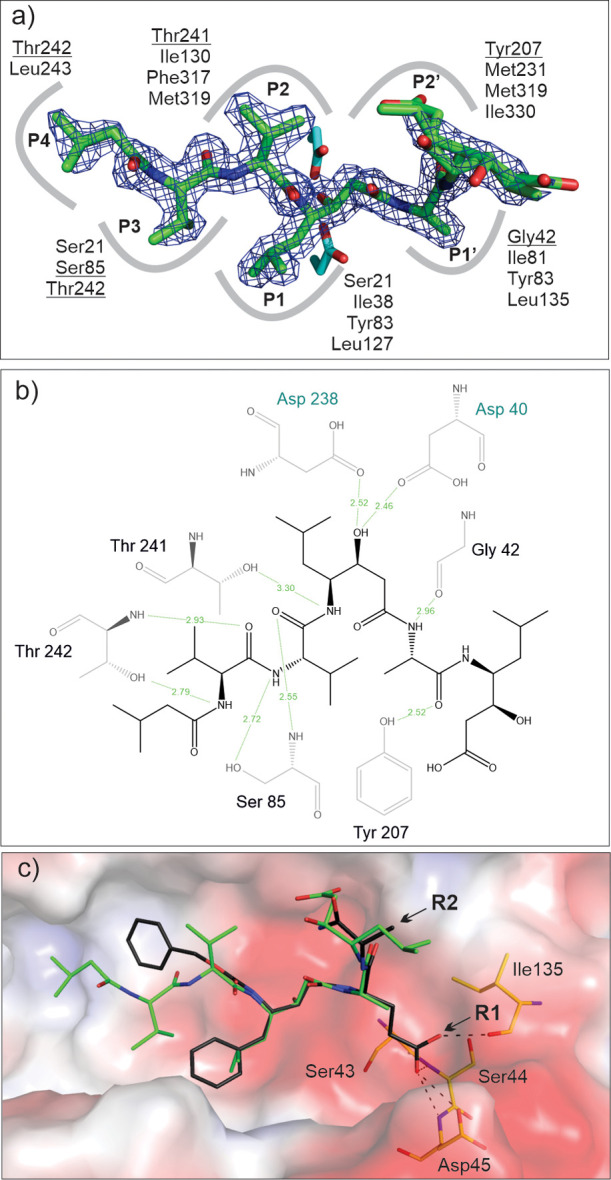

Figure 5.

PepA binding to May1 (PDB 6R6A). (a) Top view of the binding pose of PepA in the May1 active site. The 2Fo-Fc map (contoured at 1.5σ) is shown in blue; catalytic aspartates (sticks with carbons colored cyan) interact with the central statine residue. Residues contributing to PepA binding in the S4–S3 subsites are indicated; those forming polar interactions are underlined. (b) Ligand–protein interaction diagram of the May1–PepA complex generated by LigPlot.49 Residues engaged in polar ligand interactions (green dashed lines) are shown; numbers represent distances between hydrogen bond donor and acceptor in Å. (c) Model of N-terminally carboxybenzylated phenylstatine superimposed with PepA. Points of attachment for the R1 and R2 substituents are indicated by arrows. The protein is represented by its solvent accessible surface area colored by electrostatic potential (red for negative, blue for positive). Residues available to form polar interactions with the P1′ substituent are shown as sticks and labeled, and possible interactions are indicated by dashed lines.

PepA binds to May1 in an extended conformation occupying the S4–S2′ substrate binding subsites. The hydroxyl group of the central statine moiety forms two hydrogen bonds with the side chains of the two catalytic aspartates (Asp40 and Asp238). Additional hydrogen bonding interactions involve the main chain atoms of Gly42 (O), Gly84 (N), Thr82 (O), Ser85 (N), and Thr242 (N) and the side chain atoms of Ser85 (OG), Tyr207 (OH), Thr241 (OG), and Thr242 (OG). In addition to this hydrogen bonding network, the inhibitor forms extensive van der Waals interactions with May1 (Figure 5b).

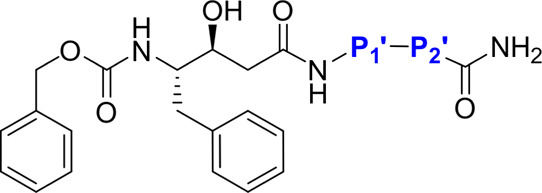

The binding pose of PepA in the active site was used to validate N-terminally carboxybenzylated phenylstatine as a suitable scaffold for production of an inhibitor library. We constructed a model by altering PepA substituents in the P2, P1, and P1′ positions and fitting them into the corresponding enzyme subsites. The model indicated that the active site of May1 is able to accommodate bulky benzene substituents in the P2 and P1 positions and polar substitutions in P1′ (Figure 5c). Moreover, we identified potential hydrogen bond donors and acceptors for interaction with P1′ polar groups (OH or NH2). The model also showed that the binding pose allows for attachment of an R2 substituent that can be extended into the S3′ subsite (Figure 5c).

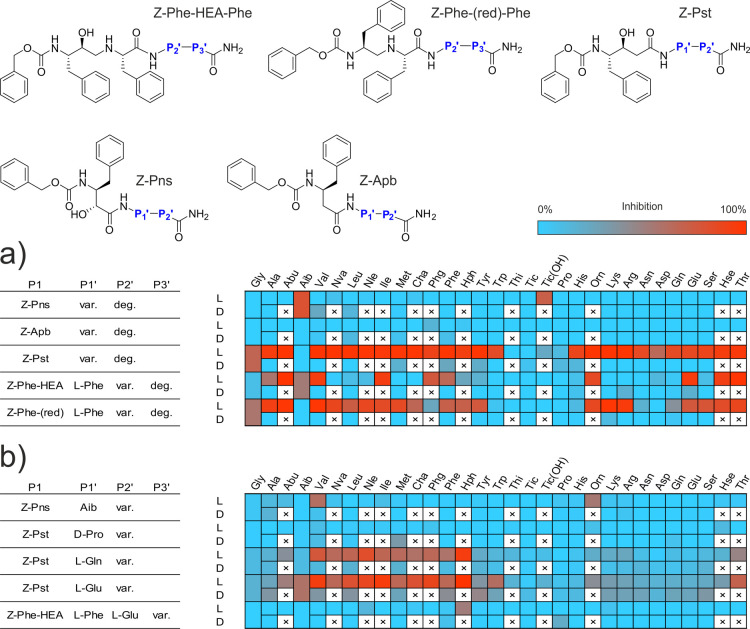

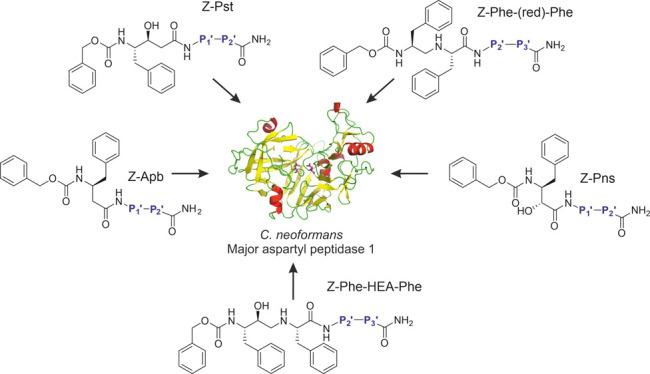

Inhibitor Motif Identification Using a Combinatorial Approach

Our first approach to lead identification involved screening a library of candidates comprising N-terminally carboxybenzylated50 (Z) aromatic peptide bond mimetics followed by a single amino acid and ending with a degenerate amino acid amide assembled by the split and mix method. We used the known peptide bond mimetics phenylnorstatine (Pns51), 3-amino-4-phenylbutanoic acid (Apb52), phenylstatine (Pst53), a Phe–Phe moiety with a reduced peptide bond (Phe–CH2–NH–Phe54) and a Phe–Phe moiety analogue with a hydroxyethylamine mimetic linkage (Phe–HEA–Phe55). For the two attached amino acids, we used a selection of 48 amino acid building blocks, including all proteinogenic amino acids except cysteine, 16 corresponding D-enantiomers, and 13 synthetic amino acid derivatives.56,57

To conduct the screening, we developed an automated assay using the internally quenched fluorescent substrate IQ-2. This method allowed us to evaluate the relative activity of individual compound mixtures expressed as a fluorescence percentage ratio between a control reaction with no inhibitor and the test compound mixture (500 nM per compound) using the PepA-inhibited reaction as a background control. This assay, combined with our combinatorial approach to inhibitor screening, allowed us to perform duplicate evaluation of 11,520 compounds in two 384-well plates to assess pharmacophore preference in the P2′ position (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Linear statin inhibitor structures and residue preference heatmaps. L and D rows indicate the amino acid enantiomer at a given position. (a) Initial screening of the N-proximal site with a degenerate C-terminal residue. A final concentration of 500 nM per individual compound was used in library screening. (b) Deconvolution of selected libraries with favorable N-proximal residues based on initial screening. Single-compound deconvolution experiments were conducted with a 1 μM final concentration of the test compound.

The results of this screening were cross-referenced with the binding preferences of HIV-1 Pr for similar statin derivatives52,56 to determine which libraries to further deconvolute to resolve the P3′ position preference and ultimately obtain a consensus inhibitor structure. HIV-1 Pr shared a preference for P2′ l-Glu and l-Gln in the Pst library class, l-Glu in the Phe–HEA–Phe class, and Aib in the Pns class. These four library mixtures were deconvoluted by screening the 48 individual mixture components (Figure 6b). Based on the results of this preliminary screen, we determined Ki values of the selected compounds presumed to inhibit at concentrations in the nanomolar range (Table 1). Compound 13a (Z-Pst–l-Glu–Hph–NH2) had the most favorable binding to May1 with Ki = 12 ± 1 nM and was therefore selected as the lead compound for further analysis.

Table 1. SAR of Selected May1 Inhibitors Derived from an N-Terminally Carboxybenzylated Phenylstatine Scaffold.

| May1 Ki [nM] |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| P2′ | P1′: L-Glu (a) | P1′: L-Gln (b) | |

| 1 | l-Abu | 760 ± 50 | 1200 ± 100 |

| 2 | l-Nva | 410 ± 60 | 470 ± 40 |

| 3 | l-Val | 82 ± 12 | 120 ± 20 |

| 4 | l-Nle | 180 ± 20 | 170 ± 10 |

| 5 | l-Leu | 160 ± 10 | ND |

| 6 | l-Ile | 410 ± 60 | 240 ± 30 |

| 7 | l-Thr | 250 ± 20 | 1300 ± 200 |

| 8 | l-Met | 280 ± 20 | 290 ± 40 |

| 9 | l-Trp | 340 ± 30 | ND |

| 10 | l-Cha | 160 ± 20 | 400 ± 60 |

| 11 | l-Phg | 210 ± 20 | 360 ± 40 |

| 12 | l-Phe | 390 ± 50 | 320 ± 30 |

| 13 | l-Hph | 12 ± 1 | 64 ± 7 |

Off-Target Activity of Lead Compound Z-Pst–l-Glu–Hph–NH2

Off-target activity is a major concern in the design of protease inhibitors. Lead compound 13a was thus investigated for in vitro off-target activity against several relevant host aspartyl proteases—human pepsin, renin, and cathepsins D and E (Table 2). In addition to inhibiting target protease May1, 13a was a potent, subnanomolar inhibitor of wild-type HIV-1 Pr.

Table 2. In Vitro Off-Target Profile of Lead Compound Z-Pst–l-Glu–Hph–NH2.

| May1 C. neoformans | HIV-1 Pr wild-type | Pepsin porcine | Renin human | Cathepsin D human | Cathepsin E human |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki 12 ± 1 nM | 32 ± 5 pM56 | 1.6 ± 0.3 μM | 19 ± 2 μM | 620 ± 50 nM | 440 ± 70 nM |

While the lead compound inhibited both cathepsins D and E at higher concentrations, the overall cytotoxic effect of the compound was very low, with CC50 higher than 80 μM for multiple cell lines (Table S2, Figure S3). As exemplified by experiments with the HepG2 cell line, the cytotoxicity is on par with or lower than that of clinically used protease inhibitors, including darunavir, amprenavir, and indinavir.40

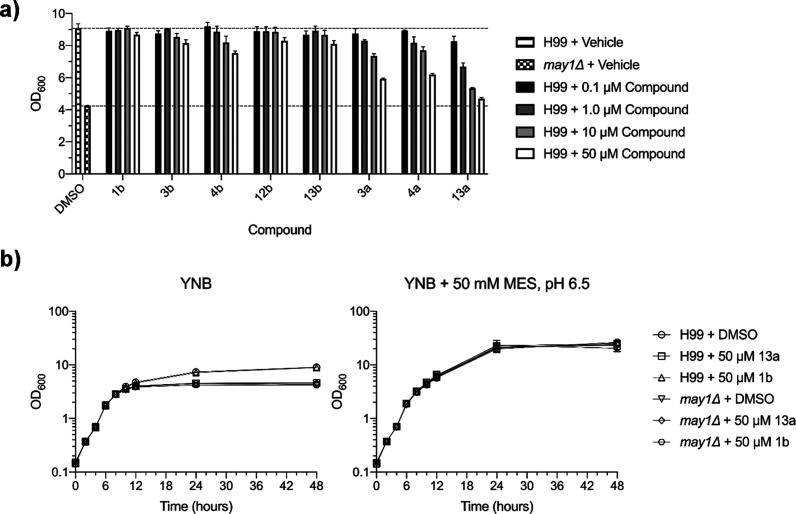

Activity of Lead Compound against Cultured C. neoformans Yeast

Next, we assessed whether May1 inhibitors identified here were effective against cultured C. neoformans yeast. Previous work showed that May1 activity is required for acidic pH tolerance of yeast grown in minimal medium.23 May1 deficiency manifested as a culture saturation density phenotype wherein may1Δ or pepstatin A-treated yeast grew normally during logarithmic growth but achieved lower terminal densities during the stationary phase after the medium had acidified.23 To identify compounds with activity against May1 in an in vivo setting, we treated yeast with a panel of inhibitors that had displayed a range of in vitro efficacies against May1 (Figure 7a). After 48 h of culture, yeast treated with compounds 3a, 4a, and 13a exhibited dose-dependent reductions in terminal culture density, with 50 μM 13a treatment nearly phenocopying the may1Δ mutant (Figure 7a).

Figure 7.

Evaluation of May1 inhibitor activity against cultured C. neoformans yeast. (a) Terminal saturation densities of yeast cultured for 48 h in YNB minimal medium containing May1 inhibitors or a 0.5% DMSO vehicle. Dashed lines represent terminal OD600’s of the DMSO-treated H99 and may1Δ controls. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean from triplicate cultures. (b) Growth curves of H99 and may1Δ yeast treated with lead compound 13a, negative control compound 1b, or a 0.5% DMSO vehicle control in either standard YNB medium (left) or YNB medium buffered to pH 6.5 (right). Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean from triplicate cultures.

If 13a activity is selective for May1, we expected that (1) 13a-treated yeast should grow similarly to untreated yeast during the logarithmic phase; (2) 13a-treatment should not further inhibit the growth or terminal saturation density of may1Δ yeast, which are already null for may1; and (3) 13a-treatment should not affect the growth of yeast cultured in medium buffered to pH 6.5, which negates the need for May1 activity.23 Consistent with 13a being a specific inhibitor of May1, 13a-treated yeast achieved similar densities to 1b- or DMSO-treated controls during the logarithmic phase growth despite failing to attain the same terminal density at saturation (Figure 7b, left). Additionally, 13a-treatment of may1Δ yeast did not further reduce culture densities during either the logarithmic or the stationary phase (Figure 7b, left), and buffering the medium to pH 6.5 eliminated the saturation density phenotype of both may1Δ and 13a-treated yeast (Figure 7b, right). Altogether, these data indicate that compound 13a is a selective May1 inhibitor in the context of cultured C. neoformans.

Discussion

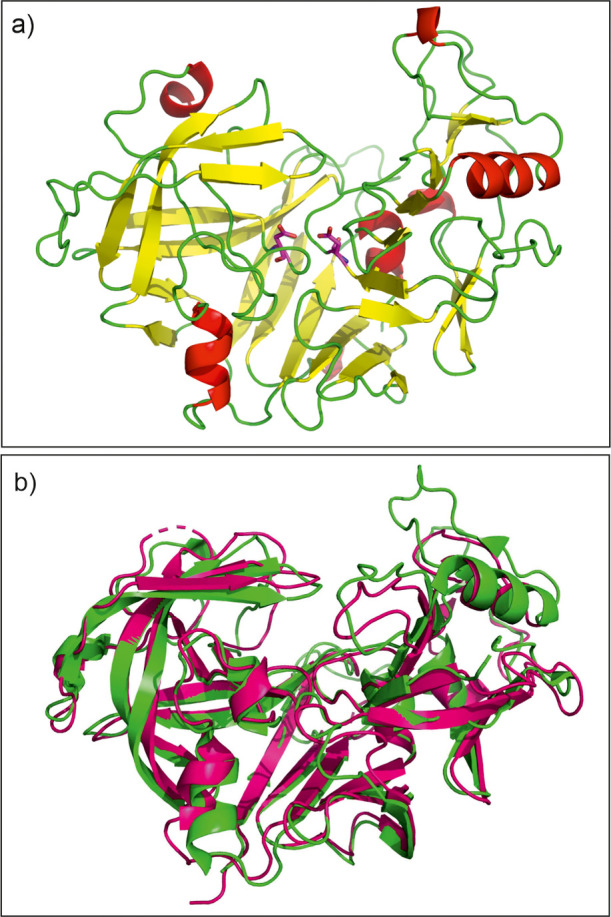

May1 has a high degree of similarity to other members of the aspartyl protease family, and we identified aspartyl proteases including endohiapepsin,59Rhizomucor miehei aspartyl proteinase,60 and candidapepsin61 as its closest structural homologues. Although the May1 sequence is distinct from that of HIV-1 Pr (13% similarity), structural similarity between the two enzymes is high, with an RMSD for superposition of 175 residues of 3.2 Å (Figure 8a). Comparison of the substrate binding clefts and binding poses of pepstatin inhibitors revealed additional similarities (Figure 8b,c).

Figure 8.

Comparison of May1 (PDB code 6R5H) with HIV-1 Pr (PDB code 2hvp(62)). (a) Overall superposition of May1 (green) with HIV-1 Pr (maroon). Catalytic aspartates are highlighted in stick representation. (b) Top view into the May1 active site. The protein is represented by the solvent accessible surface area colored by electrostatic potential; PepA is represented as sticks with carbon atoms colored green; the inhibitor pose in HIV-1 Pr is shown with black lines. (c) Top view into the HIV-1 Pr active site. The protein is represented by solvent accessible surface area colored by electrostatic potential; acetyl-pepstatin is represented as sticks with carbon atoms colored yellow; the PepA pose in May1 is shown with black lines. In b and c, flap regions covering the active site are omitted for clarity.

Inhibitors bind to the active sites of both enzymes in a comparable manner, especially for the P1 to P4 substituents (Figure 8b,c). On the other hand, we observed variation in the positions of P1′, P2′, and P3′ substituents. May1 binding sites on the prime side form a rather wide groove that could accommodate larger P2′ and P3′ substituents, such as Hph in Z-Pst–l-Glu–Hph–NH2.

Internally quenched fluorescent substrate libraries containing natural and unnatural amino acids are a convenient chemical tool for investigating the substrate specificity of endopeptidases.65,66 Inclusion of unnatural amino acids with diverse chemical structures enables precise examination of the binding pocket architecture. We confirmed the preference of May1 for large aromatic and hydrophobic residues in the P1–P1′ positions, as expected for an aspartyl protease, and observed favorable binding of positively charged amino acids at the P2 subsite. These findings are in agreement with the promiscuous GIT*R*R*K*RAN prodomain cleavage sites identified by mass spectrometry (Figure S1a) and follow general preferences for aspartyl protease sequence specificity.63 The observed preference for hydrophobic and positively charged amino acids potentially implicates May1 in cleavage of lamin, fibronectin, and elastin,64 further reinforcing the link between May1 and extracellular matrix degradation.

Next, we set out to identify a potential dual-specificity inhibitor of HIV-1 Pr and May1. Pepstatin is a prototypical aspartyl protease inhibitor with picomolar binding affinity toward cathepsin D-like enzymes.65,66 We and others have previously shown that pepstatin derivatives can serve as a useful scaffold for design of highly potent inhibitors of HIV-1 Pr and cathepsin D-like enzymes.67,68 Therefore, we based our inhibition specificity screen on pepstatin-like scaffolds (phenylstatine and phenylnorstatine) and complemented them with other peptidomimetics such as Apb, a reduced peptide bond, and a hydroxyethylamine peptide bond isostere. Libraries containing peptidomimetics other than Apb showed inhibitory activity against May1. Libraries containing Pns and Phe–CH2–NH–Phe mimetics with l-amino acid enantiomers at the P2′ position were generally good inhibitors, with no strong preference for a single amino acid class. Only peptides with orientation-changing residues (D-enantiomers, Aib, Pro, Tic) were disfavored. Phe–HEA–Phe libraries had a narrower preference for charged amino acids and shared the trend of favoring P2′ l-Glu rather than l-Asp with the Phe–CH2–NH–Phe class. Curiously, Phe–HEA–Phe and Pns libraries were more tolerant of Aib substitution, which was also the dominant residue in the Pns class. The observed preference for hydrophobic and charged residues at the P2′ position in the Pst, Phe–HEA–Phe, and Phe–CH2–NH–Phe mimetic classes is not in complete agreement with a recently published May1 substrate specificity analysis,23 which reports hydrophobic and aromatic residues being favored in P1′–P3′, with Asn and Gln being disfavored in P2′ presumably due to the difference in the libraries used to probe the specificity.

Deconvolution screening of the Pns–Aib and Phe–HEA–Phe libraries did not yield any major hits. However, these libraries shared a common preference for some hydrophobic and aromatic residues in the P3′ position with the Pst–l-Glu and Pst–l-Gln libraries, which showed an almost exclusive preference for this class of residues. Most importantly, Pst–l-Glu and Pst–l-Gln inhibitors with aromatic residues at the P3′ position were favored, similarly as for HIV-1 Pr inhibitors of these classes.52 Both Pst–l-Glu and Pst–l-Gln exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect with l-homophenylalanine (Hph) at the terminal P3′ position, which we determined to be the most favorable residue among the 48 assayed blocks.

The lead structure obtained by combinatorial screening—13a—is a potent inhibitor of May1 with Ki = 12 ± 1 nM, and its activity profile in yeast culture indicates that its mode of antifungal action is driven specifically by MayI inhibition. It also inhibits wild-type HIV-1 Pr with Ki = 32 ± 5 pM and three drug resistance-associated mutants with Ki values ranging from 24 to 320 pM.56 Compound 13a also showed remarkable selectivity between May1 and human renin, its closest structural homologue. This can be attributed to the distinct renin inhibitor preference.69 Renin inhibition favors non-aromatic transition-state analogues preceded by nonpolar residues,69 whereas 13a as a May1 inhibitor possesses a phenylstatine analogue preceded by a charged Glu residue. This lead compound therefore exemplifies a common inhibitor of both HIV-1 Pr and May1 with a favorable in vitro cytotoxicity and anti-fungal activity profile.

Conclusions

In this work, we structurally and functionally characterized C. neoformans May1, a secreted fungal protease. Using structure-guided combinatorial screening, we identified a common inhibitor of both May1 and HIV-1 Pr. With a favorable cytotoxicity profile, low in vitro off-target activity, and demonstrated activity in yeast culture, this compound could serve as a scaffold for further inhibitor development.

Experimental Section

Expression of Recombinant May1

An established protocol for the expression and purification of proteins in Drosophila S2 cells70 was used to prepare the May1(17-434)-Avi construct for kinetics and crystallization. Full-length cnap1 gene cDNA encoding May1 (CNAG_05872) generated in silico in pUC57 plasmid was purchased from Genscript. The 17-434 fragment was PCR amplified using primers 5′-AAAAAGATCTGCACCAAGCAACAGCGTC-3′ and 5′-AAAAGCGGCCGCCAGTTCAGCGAATCCGAT-3′, which include BglII and NotI restriction sites. The amplified fragment was purified by gel extraction and digested with BglII and NotI (NEB R0144, R0189) per the manufacturer’s protocol. The cleaved fragment was again purified and ligated using T4 DNA ligase (NEB M0202) into an analogously digested and purified pMT_BiP_CAvi plasmid fragment. The ligation reaction mixture was transformed into TOP10 competent Escherichia coli (Invitrogen C404010), and the sequence identity of the resulting plasmid DNA was verified by sequencing. Following transfection of S2 cells using calcium phosphate and selection of an expression clone (300 μg/mL hygromycin-B), a large-scale expression in 3 L of serum-free media (Thermo Fisher Scientific 21720) was carried out. The expressed construct was concentrated and purified using affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography. Briefly, crude media was concentrated using tangential flow filtration (Labscale TFF), yielding a 50-fold concentrate and permeate, which was discarded. The concentrate dialyzed against 100 mM Tris, pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl (Buffer W) was purified using Streptavidin Mutein Matrix (Roche 3708152001) in a cold room. The flow-through fraction was collected and used for subsequent purification (a total of 4 times per expression run). The enzyme was eluted using 2 mM biotin in Buffer W. Elution fractions were pooled, concentrated, and exchanged into 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 50 mM sodium chloride (Buffer P) by ultrafiltration to avoid loss of activity outside the pH optimum and then purified by Superdex 75 gel filtration on a GE ÄKTA Explorer FPLC system. Size exclusion chromatography yielded a monodisperse protein preparation as verified by dynamic light scattering (Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS, data not shown). Overall, 3 L of S2 culture yielded 15 mg of >95% pure (SDS-PAGE) monodisperse recombinant May1. Enzyme concentration and purity was further evaluated by amino acid analysis and active site titration. Protein mass was evaluated using Bruker Daltonics UltrafleXtreme a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer.

Combinatorial Library Testing

Assays were conducted in 384-well plates with transparent flat bottoms (Greiner 781097) in a stop-point format. Assay mixtures consisted of 15 μL of 50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.0, 50 mM sodium chloride, 0.05% Tween-20 (Buffer R) with 20 μM IQ-2 substrate [AMC-GSPAFLAK(DNP)dR-NH2]. Test compounds were dispensed by a LabCyte Echo 550 acoustic dispensing system with a final DMSO content of 0.8% (v/v). For library mixtures, a final concentration of 500 nM of each individual compound was used; for single-compound deconvolution experiments, a 1 μM final concentration was used. Reactions conducted at 37 °C were started by sequential addition of 5 ng May1 in 10 μL of Buffer R to each well by an EnSpire Multilabel Reader and stopped after 20 min by addition of 12 μL of 50 μM pepstatin A in Buffer R. Reaction fluorescence (excitation at 328 nm, emission at 393 nm) was analyzed using a plate reader (Tecan Infinite M1000). Each plate contained two columns of positive control wells containing 1 μM pepstatin A and negative controls with DMSO to determine Z′ and a vertical signal shift.

Ki Determination

The combinatorial library screening assay was adjusted to contain a threefold dilution series of inhibitors with 10 points in total designed to be centered around the expected Ki determined from preliminary assays. Ki values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis using the Williams–Morrison equation (GraphPad Software GraphPad Prism 6) and applying the Cheng-Prusoff model for correction based on the Km value of the IQ-2 substrate (21 ± 4 μM), as previously described.71 Inhibition curves are included in Figure S4 in the Supporting Information.

Active Site Titration

The fraction of active protease in our enzyme preparations was determined by assessing 20 μM IQ-2 substrate cleavage efficiency in the presence of 50 nM May1 protease in Buffer P and titrating with increasing amounts of PepA (Ki = 1.3 nM). In a linear regression model of the percentage of protease activity against the PepA concentration, the x-axis intercept represents the concentration of active protease present in the sample. The active site concentrations of all preparations were close to the respective protein concentrations determined by amino acid analysis, indicating that the enzyme preparations were >99% active (data not shown).

Determining the May1 pH Optimum

Fluorogenic activity assays were conducted using 20 μM IQ-2 with 50 ng of May1(17-434)-Avi in 40 mM phosphate-borate-acetate Britton–Robinson buffer72 from pH 2.0 to 13.0 with steps of 0.5. The activity maximum was further resolved with a series of buffers with pH values ranging from 4.0 to 6.0 with steps of 0.2.

Substrate Specificity Screening

To obtain a substrate specificity matrix, the peptide ACC-GKSLGFLVAK(DNP)G-NH2 was modified by incorporating natural and unnatural amino acids in the SLGFL sequence to yield five internally quenched fluorescent substrate sublibraries (P1-4 and P1′), each consisting of 85–91 compounds. These sublibraries were screened at 2 μM with 2 nM May1(17-434)-Avi100 in Buffer P (1% v/v DMSO) in a final volume of 100 μL. Substrate specificity screening was conducted in an opaque 96-well plate (Costar, Corning). The enzyme was incubated in buffer P for 15 min at 37 °C prior to substrate addition, and substrate hydrolysis was monitored by fluorescence measurement on a SpectraMax Gemini XPS Microplate Reader (Molecular Devices) in kinetic mode (excitation at 355 nm, emission at 460 nm) for 15 min, using only the linear portion of the hydrolysis curve to calculate the final reaction velocity (relative fluorescent units per second, RFU/s). Screening of libraries was performed in duplicate, and the resulting average value was used to calculate May1 specificity matrices. Every sublibrary was scaled to 100% for the amino acid with the highest RFU/s value.

Assays for Off-Target Activity

Selected lead inhibitors were screened for off-target activity against pepsin (porcine, Sigma-Aldrich P7012), renin (human, Biovision 6300), cathepsin D (human, Athens Research & Technology 16-12-030104), and cathepsin E (human, Biovision 7842). We followed established protocols with the substrates BSA–bromophenol blue73 (formal Km = 80 μM) for pepsin, H-R-E(EDANS)-IHPFHLVIHT-K(DABCYL)-R-OH74 (Km = 2.5 μM, Anaspec AS-62022) for renin, and ACC-GKPILFFRLK(DNP)-(dR)-NH275 (Km,CatD = 3.7 μM, Km,CatE = 3.3 μM, Anaspec AS-61793) for cathepsins D and E. Inhibition curves are included in Figure S5 in the Supporting Information.

Yeast Culture Activity Assay

C. neoformans strains H99 (CM018) and may1Δ (CM1383)23 were cultured in Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) medium containing 2% glucose. To assess May1 inhibitors for reduction of saturation culture density, overnight cultures were diluted to OD600’s of 0.1 the presence of 0.5% DMSO vehicle or 0.1, 1.0, 10, or 50 μM compound. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C on a tube rotator, and OD600’s were measured after 48 h. For full growth curves, logarithmically growing cultures were pelleted and resuspended to OD600’s of 0.1 in either unbuffered YNB or YNB containing 50 mM MES, pH 6.5. Cultures were treated with 50 μM 13a, 50 μM 1b, or 0.5% DMSO vehicle and were incubated at 30 °C on a tube rotator. OD600’s were measured at 2 h intervals for 12 h and after 24 and 48 h of growth.

Crystallization and X-ray Data Collection

Diffraction-quality crystals of native May1 were obtained at 25 °C using the hanging-drop vapor diffusion technique by mixing equal volumes of May1(17-434)-Avi (83 mg/mL) in Buffer P with reservoir solution composed of 200 mM lithium sulfate, 45% (v/v) PEG-400, 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5. After 7 days, crystals used for X-ray data collection were harvested, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen with the reservoir solution as self-cryoprotectant, and stored. These conditions yielded crystals of space group C2221 (a = 97.4 Å, b = 112.1 Å, c = 91.2 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) diffracting up to 1.75 Ε. Co-crystallization of May1 with PepA was performed using the same technique. The May1–inhibitor complex was formed by incubating May1(17-434)-Avi protein (1 mg/mL) in Buffer P with PepA (100 μM final concentration) at 4 °C for 1 h. The complex was then concentrated, and excess inhibitor was removed by ultrafiltration using an Amicon 3K MWCO centrifugal device. Diffraction quality crystals were obtained at 25 °C by mixing equal volumes of the concentrated May1–PepA complex with the same reservoir solution as above. Drops were streak-seeded with previously obtained native May1 crystal seeds. After 4–9 days, the crystals were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored for X-ray data collection.

Diffraction data for the May1–PepA complex were collected at 100 K on an in-house MicroMax-007 HF Microfocus X-ray generator with a VariMax VHF ArcSec confocal optical system (Rigaku, Japan), an AFC11 partial four-axis goniometer (Rigaku, Japan), a PILATUS 300 K detector (Dectris, Switzerland), and a Cryostream 800 cryocooling system (Oxford Cryosystems, England). Diffraction data for free May1 were collected at 100 K on MX 14.1 operated by the Joint Berlin MX-Laboratory at the BESSY II electron-storage ring in Berlin-Adlershof, Germany.76 Diffraction data were processed using XDS.77 The crystal parameters and data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table S1.

Structure Determination, Model Building, and Refinement

The structure of the May1–PepA complex was solved by molecular replacement with CCP4 Molrep78,79 using the structure of human renin (PDB 2REN)42 and the native May1 structure (PDB 6R5H, this work) as search models. The initial models were refined through several cycles of manual building using Coot and automated refinement with CCP4 REFMAC5.80 Visualization of structural data was performed in PyMOL 0.99rc6, and 2D diagrams summarizing molecular interaction between inhibitors and May1 were prepared using LigPlot.49 Atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited into the Protein Data Bank under codes 6R5H and 6R6A for free May1 and the May1–PepA complex, respectively.

Organic Synthesis

Synthesis and characterization of linear statin combinatorial libraries have been previously described.57 Briefly, libraries were prepared on a Rink amide linker resin using an automated Fmoc/HOBt/DIC SPPS strategy. Degenerate positions were introduced by the split and mix method using 48 amino acid building blocks and five peptidomimetic building blocks with carboxybenzylated N-termini. Deconvoluted libraries and individual assayed compounds were synthesized as previously described.56 Internally quenched fluorescent substrate libraries were prepared using standard SPPS as previously described.81

1H and 13C NMR spectra were measured using a Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 with broadband PRODIGY cryo-probe. High-resolution ESI mass spectra were recorded using a hybrid FT mass spectrometer with an Orbitrap mass analyzer (LTQ Orbitrap XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Nominal ESI mass and purity of the compounds were assessed on an analytical Agilent 6230 Accurate-Mass TOF liquid chromatograph–mass spectrometer (flow rate of 0.3 mL min–1, invariable gradient from 2 to 100% acetonitrile in 8 min, 0.1% formic acid) with a Waters ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (1.7 μm, 100 × 2.1 mm).

The compounds were purified by preparative HPLC on an Agilent 1200 Series instrument equipped with a G1365D DAD detector and Vydac 218TP101522 C18 Prep Column (10–15 μm, 22 × 250 mm) using invariable 2 to 100% gradient of CH3OH/H2O with 0.05% TFA for 90 min, 222 nm detection, and flow rate of 7 mL min–1.

Compounds with high activity against May1 (3a, 3b, 4a, 4b, 13a, and 13b) were selected for thorough characterization by 1H and 13C NMR. Their LC traces are included in the Supporting Information Figure S6. The following compounds were under 95% purity: 2a, 5a, 6a, 8a, 9a, 11a, 12a, 1b, 2b, 4b, 6b, 7b, 8b, 10b, 11b, and 12b. Compounds 1a, 3a, 4a, 7a, 10a, 13a, 3b, and 13b were ≥95% pure.

Compound 1a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 557.26 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 579.24182 [M + Na]+ calcd C28H36O8N4Na+, 579.24254. HPLC: rt 6.47 min (95.1%).

Compound 2a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 571.28 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 593.25778 [M + Na]+ calcd C29H38O8N4Na+, 593.25819. HPLC: rt 6.34 min (93.6%).

Compound 3a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 571.28 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.09 (s, 1H), 8.04 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.24 (m, 5H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.15 (m, 5H), 7.12 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.00 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (td, J = 8.3, 5.3 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dd, J = 8.9, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.96–3.92 (m, 1H), 3.77–3.65 (m, 2H), 2.87 (dd, J = 13.7, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 13.6, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.34–2.17 (m, 4H), 2.00–1.82 (m, 2H), 1.79–1.67 (m, 1H), 0.82 (dd, J = 13.1, 6.7 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.55, 173.24, 171.64, 171.60, 156.43, 139.94, 137.71, 129.56 (2C), 128.74 (2C), 128.52 (2C), 128.02, 127.69 (2C), 126.33, 69.32, 65.43, 57.79, 57.38, 52.58, 49.06, 36.11, 30.87, 30.70, 27.71, 19.75, 18.32. HRMS m/z: 571.27579 [M + H]+ calcd C29H39O8N4+, 571.27624. HPLC: rt 6.92 min (98.9%).

Compound 4a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxohexan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 585.31 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.05 (s, 1H), 8.09 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.23 (m, 5H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.16 (m, 5H), 7.14 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (td, J = 8.3, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dt, J = 8.8, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 3.99–3.90 (m, 1H), 3.77–3.56 (m, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 13.7, 4.5 Hz, 1H), 2.64 (dd, J = 13.8, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 2.34–2.22 (m, 4H), 1.93–1.70 (m, 2H), 1.73–1.57 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.38 (m, 1H), 1.26–1.12 (m, 4H), 0.79 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.52, 174.15, 171.88, 171.59, 156.57, 139.86, 137.69, 129.59 (2C), 128.73 (2C), 128.50 (2C), 128.00, 127.62 (2C), 126.30, 69.48, 65.44, 57.08, 53.04, 52.84, 49.07, 36.56, 31.58, 30.57, 28.02, 27.53, 22.20, 14.31. HRMS m/z: 585.29153 [M + H]+ calcd C30H41O8N4+, 585.29189. HPLC: rt 7.02 min (96.2%).

Compound 5a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-4-methyl-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 585.30 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 607.27309 [M + Na]+ calcd C30H40N4O8Na+, 607.27384. HPLC: rt 6.79 min (94.4%).

Compound 6a ((S)-5-(((2S,3S)-1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 585.30 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 607.27311 [M + Na]+ calcd C30H40N4O8Na+, 607.27384. HPLC: rt 6.81 min (92.2%).

Compound 7a ((S)-5-(((2S,3R)-1-amino-3-hydroxy-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 573.26 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 595.23689 [M + Na]+ calcd C28H36N4O9Na+, 595.23745. HPLC: rt 6.36 min (99.5%).

Compound 8a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-4-(methylthio)-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 603.25 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 603.24782 [M + H]+ calcd C29H39N4O8S+, 603.24831. HPLC: rt 6.63 min (71.6%).

Compound 9a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-1-oxopropan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 658.29 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 680.26867 [M + Na]+ calcd C35H39N5O8Na+, 680.26908. HPLC: rt 6.86 min (74.1%).

Compound 10a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 625.33 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 647.30450 [M + Na]+ calcd C33H44N4O8Na+, 647.30514. HPLC: rt 7.12 min (95.1%).

Compound 11a ((S)-5-(((S)-2-amino-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 605.27 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 627.24160 [M + Na]+ calcd C32H36N4O8Na+, 627.24254. HPLC: rt 6.79 min (93.1%).

Compound 12a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 619.28 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 641.25726 [M + Na]+ calcd C33H38N4O8Na+, 641.25819. HPLC: rt 6.81 min (94.8%).

Compound 13a ((S)-5-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxo-4-phenylbutan-2-yl)amino)-4-((3S,4S)-4-(((benzyloxy)carbonyl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-phenylpentanamido)-5-oxopentanoic acid) analytical data MS m/z: 633.32 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 12.10 (s, 1H), 8.16 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (s, 1H), 7.30–7.22 (m, 5H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.22–7.11 (m, 10H), 7.10 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 12.1 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.21–4.14 (m, 2H), 4.00–3.93 (m, 1H), 3.77–3.66 (m, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 13.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.68–2.60 (m, 1H), 2.48–2.40 (m, 2H), 2.36–2.26 (m, 4H), 1.97–1.86 (m, 2H), 1.86–1.70 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.51, 173.97, 172.04, 171.80, 156.63, 141.77, 139.83, 137.65, 129.60 (2C), 128.72 (2C + 2C, overlap), 128.49 (2C), 127.99 (2C), 127.61 (2C + 1C, overlap), 126.30, 126.23, 69.58, 65.48, 57.01, 53.32, 52.57, 49.06, 36.70, 33.46, 31.93, 30.62, 27.38. HRMS m/z: 633.29153 [M + H]+ calcd C34H41O8N4+, 633.29189. HPLC: rt 7.25 min (98.3%).

Compound 1b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 556.28 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 578.25753 [M + Na]+ calcd C28H37N5O7Na+, 578.25852. HPLC: rt 6.34 min (93.6%).

Compound 2b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 570.30 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 592.27344 [M + Na]+ calcd C29H39N5O7Na+, 592.27417. HPLC: rt 6.49 min (88.1%).

Compound 3b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 570.31 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.06 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.35–7.24 (m, 5H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.24–7.16 (m, 5H), 7.13 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.76 (s, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (d, J = 12.8 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (td, J = 8.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (dd, J = 8.9, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 3.99–3.88 (m, 2H), 3.72 (t, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.87 (dd, J = 13.6, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.60 (dd, J = 13.7, 10.0 Hz, 1H), 2.34–2.17 (m, 2H), 2.17–2.02 (m, 2H), 2.01–1.82 (m, 2H), 1.77–1.65 (m, 1H), 0.82 (dd, J = 13.2, 6.8 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.33, 173.28, 171.80, 171.56, 156.44, 139.95, 137.71, 129.56 (2C), 128.74 (2C), 128.52 (2C), 128.02, 127.69 (2C), 126.33, 69.34, 65.43, 57.74, 57.37, 52.97, 49.06, 36.10, 32.06, 30.90, 28.29, 19.76, 18.30. HRMS m/z: 570.29189 [M + H]+ calcd C29H40O7N5+, 570.29223. HPLC: rt 6.73 min (95.0%).

Compound 4b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxohexan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 584.33 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.14 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 7.82 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.32 (s, 1H), 7.32–7.23 (m, 5H), 7.23 (s, 1H), 7.23–7.16 (m, 5H), 7.14 (d, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 6.78 (s, 1H), 5.02 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.88 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 4.17–4.05 (m, 2H), 3.96 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.77–3.67 (m, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 13.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.65 (dd, J = 13.8, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.24 (m, 2H), 2.20–2.04 (m, 2H), 1.92–1.71 (m, 2H), 1.69–1.59 (m, 1H), 1.49–1.38 (m, 1H), 1.25–1.13 (m, 4H), 0.79 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.33, 174.22, 171.84, 171.77, 156.58, 139.85, 137.69, 129.60 (2C), 128.73 (2C), 128.50 (2C), 128.00, 127.62 (2C), 126.30, 69.50, 65.44, 57.05, 53.47, 52.85, 49.07, 36.56, 31.98, 31.59, 28.10, 28.02, 22.21, 14.31. HRMS m/z: 584.30756 [M + H]+ calcd C30H42O7N5+, 584.30788. HPLC: rt 6.88 min (92.1%).

Compound 6b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((2S,3S)-1-amino-3-methyl-1-oxopentan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 584.31 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 606.28878 [M + Na]+ calcd C30H41N5O7Na+, 606.28982. HPLC: rt 6.65 min (88.2%).

Compound 7b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((2S,3R)-1-amino-3-hydroxy-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 572.28 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 594.25243 [M + Na]+ calcd C28H37N5O8Na+, 594.25343. HPLC: rt 6.25 min (92.1%).

Compound 8b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-4-(methylthio)-1-oxobutan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 602.27 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 602.26362 [M + H]+ calcd C29H40N5O7S+, 602.26430. HPLC: rt 6.51 min (82.2%).

Compound 10b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-3-cyclohexyl-1-oxopropan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 624.35 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 646.32006 [M + Na]+ calcd C33H45N5O7Na+, 646.32112. HPLC: rt 7.00 min (84.2%).

Compound 11b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-2-amino-2-oxo-1-phenylethyl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 604.28 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 626.25753 [M + Na]+ calcd C32H37N5O7Na+, 626.25852. HPLC: rt 6.64 min (87.4%).

Compound 12b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxo-3-phenylpropan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 618.30 [M + H]+, HRMS m/z: 640.27388 [M + Na]+ calcd C33H39N5O7Na+, 640.27417. HPLC: rt 6.71 min (85.3%).

Compound 13b (benzyl ((2S,3S)-5-(((S)-5-amino-1-(((S)-1-amino-1-oxo-4-phenylbutan-2-yl)amino)-1,5-dioxopentan-2-yl)amino)-3-hydroxy-5-oxo-1-phenylpentan-2-yl)carbamate) analytical data MS m/z: 632.33 [M + H]+. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.22 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (s, 1H), 7.30–7.23 (m, 5H), 7.22 (s, 1H), 7.22–7.11 (m, 10H), 7.11 (s, 1H), 7.10 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (s, 1H), 4.99 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.87 (d, J = 12.9 Hz, 1H), 4.18–4.05 (m, 2H), 3.98 (td, J = 6.7, 2.6 Hz, 1H), 3.76–3.68 (m, 2H), 2.83 (dd, J = 13.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.66 (dd, J = 13.6, 10.3 Hz, 1H), 2.47–2.39 (m, 2H), 2.32 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.24–2.09 (m, 2H), 1.99–1.85 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.68 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 174.33, 174.05, 172.01, 171.98, 156.65, 141.79, 139.82, 137.65, 129.61 (2C), 128.72 (2C + 2C, overlap), 128.49 (2C), 128.00 (2C), 127.61 (2C + 1C, overlap), 126.31, 126.22, 69.60, 65.49, 56.98, 53.78, 52.56, 49.07, 36.72, 33.47, 31.98, 31.93, 27.93. HRMS m/z: 632.30772 [M + H]+ calcd C34H42O7N5+, 632.30788. HPLC: rt 7.07 min (96.7%).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karolína Šrámková for technical support throughout the duration of the study.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AMC

7-amino-4-methyl-3-coumarinylacetic acid

- ACC

7-amino-4-carbamoylmethylcoumarin

- K(DNP)

Nε-((2,4-dinitrophenyl)-l-lysine)

- HIV-1 Pr

HIV-1 protease

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- Pns

phenylnorstatine

- Apb

3-amino-4-phenylbutanoic acid

- Pst

phenylstatine

- HEA

hydroxethylamine mimetic linkage

- Abu

2-aminobutyric acid

- Nva

norvaline

- Cha

3-cyclohexylalanine

- Phg

phenylglycine

- Hph

homophenylalanine

- Aib

2-aminoisobutyric acid

- Tic

1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline-3-carboxylic acid

- Pal

pyridylalanine

- Thi

β-thienylalanine

- Hyp

4-hydroxyproline

- hSer

homoserine

- PepA

pepstatin A

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c02177.

Accession Codes

PDB code for MayI with bound PepA is 6R6A. MayI in apo-enzyme form is under 6R5H.

The study was supported by the EU Regional Development Fund (OP RDE) Project Chemical biology for drugging undruggable targets (J.K., ChemBioDrug, CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000729) and by National Institutes of Health grants T32HL007185 (M.J.B.), F32AI152270 (M.J.B.), R01AI100272 (H.D.M.), and P50GM082250 (C.S.C.). H.D.M. is an Investigator of the Chan-Zuckerberg Biohub.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

The authors will release the atomic coordinates and experimental data upon article publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kwon-Chung K. J.; Boekhout T.; Wickes B. L.; Fell J. W.. Systematics of the Genus Cryptococcus and its Type Species C. Neoformans. Cryptococcus; ASM Press, 2011; Vol. 1; pp 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Chang C. C.; Crane M.; Zhou J.; Mina M.; Post J. J.; Cameron B. A.; Lloyd A. R.; Jaworowski A.; French M. A.; Lewin S. R. HIV and Co-infections. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 114–142. 10.1111/imr.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis J. N.; Harrison T. S. HIV-associated Cryptococcal Meningitis. AIDS 2007, 21, 2119–2129. 10.1097/qad.0b013e3282a4a64d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velagapudi R.; Hsueh Y.-P.; Geunes-Boyer S.; Wright J. R.; Heitman J. Spores as Infectious Propagules of Cryptococcus Neoformans. Infect. Immun. 2009, 77, 4345–4355. 10.1128/iai.00542-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson H. I. Not Your “Typical Patient”: Cryptococcal Meningitis in an Immunocompetent Patient. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 2005, 37, 144–148. 10.1097/01376517-200506000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui G.; Lee N.; Ip M.; Choi K. W.; Tso Y. K.; Lam E.; Chau S.; Lai R.; Cockram C. S. Cryptococcosis in Apparently Immunocompetent Patients. Q. J. Med. 2006, 99, 143–151. 10.1093/qjmed/hcl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas P. G. Cryptococcal Infections in Non-HIV-infected Patients. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2013, 124, 61–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasingham R.; Smith R. M.; Park B. J.; Jarvis J. N.; Govender N. P.; Chiller T. M.; Denning D. W.; Loyse A.; Boulware D. R. Global Burden of Disease of HIV-associated Cryptococcal Meningitis: an Updated Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 873–881. 10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30243-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-James D.; Meintjes G.; Brown G. D. A Neglected Epidemic: Fungal Infections in HIV/AIDS. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 120–127. 10.1016/j.tim.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Guidelines for the Diagnosis, Prevention and Management of Cryptococcal Disease in HIV-Infected Adults, Adolescents and Children: Supplement to the 2016 Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluconazole Injection Current Drug Shortages. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortage-Detail.aspx?id=318 (accessed Mar 19, 2021).

- Sloan D. J.; Dedicoat M. J.; Lalloo D. G. Treatment of Cryptococcal Meningitis in Resource Limited Settings. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 22, 455–463. 10.1097/qco.0b013e32832fa214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold N. P. Antifungal Resistance: Current Trends and Future Strategies to Combat. Infect. Drug Resist. 2017, 10, 249–259. 10.2147/idr.s124918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins N.; Caplan T.; Cowen L. E. Molecular Evolution of Antifungal Drug Resistance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 753–775. 10.1146/annurev-micro-030117-020345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph-Horne T.; Loeffler R. S. T.; Hollomon D. W.; Kelly S. L. Amphotericin B resistant isolates ofCryptococcus neoformanswithout alteration in sterol biosynthesis. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 1996, 34, 223–225. 10.1080/02681219680000381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyse A.; Dromer F.; Day J.; Lortholary O.; Harrison T. S. Flucytosine and Cryptococcosis: Time to Urgently Address the Worldwide Accessibility of a 50-year-old Antifungal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2435–2444. 10.1093/jac/dkt221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.-C.; Chang T.-Y.; Liu J.-W.; Chen F.-J.; Chien C.-C.; Lee C.-H.; Lu C.-H. Increasing Trend of Fluconazole-non-susceptible Cryptococcus Neoformans in Patients with Invasive Cryptococcosis: a 12-year Longitudinal Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2015, 15, 277. 10.1186/s12879-015-1023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanglard D. Emerging Threats in Antifungal-Resistant Fungal Pathogens. Front. Med. 2016, 3, 11. 10.3389/fmed.2016.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scorzoni L.; de Paula E Silva A. C. A.; Marcos C. M.; Assato P. A.; de Melo W. C. M. A.; de Oliveira H. C.; Costa-Orlandi C. B.; Mendes-Giannini M. J. S.; Fusco-Almeida A. M. Antifungal Therapy: New Advances in the Understanding and Treatment of Mycosis. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 08, 36. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanjako D.; Colebunders R.; Coutinho A. G.; Kamya M. R. Strategies to Optimize HIV Treatment Outcomes in Resource-limited Settings. AIDS Rev. 2009, 11, 179–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan L. H.; Klein B. S.; Levitz S. M. Virulence Factors of Medically Important Fungi. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1996, 9, 469–488. 10.1128/cmr.9.4.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandujano-González V.; Villa-Tanaca L.; Anducho-Reyes M. A.; Mercado-Flores Y. Secreted Fungal Aspartic Proteases: A review. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2016, 33, 76–82. 10.1016/j.riam.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke S. C.; Dumesic P. A.; Homer C. M.; O’Donoghue A. J.; La Greca F.; Pallova L.; Majer P.; Madhani H. D.; Craik C. S. Integrated Activity and Genetic Profiling of Secreted Peptidases in Cryptococcus Neoformans Reveals an Aspartyl Peptidase Required for Low pH Survival and Virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1006051 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinti M.; Orsi C. F.; Gibellini L.; Esposito R.; Cossarizza A.; Blasi E.; Peppoloni S.; Mussini C. Identification and characterization of an aspartyl protease fromCryptococcus neoformans. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3882–3886. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidrim J. J. C.; Perdigão-Neto L. V.; Cordeiro R. A.; Brilhante R. S. N.; Leite J. J. G.; Teixeira C. E. C.; Monteiro A. J.; Freitas R. M. F.; Ribeiro J. F.; Mesquita J. R. L.; Gonçalves M. V. F.; Rocha M. F. G. Viral Protease Inhibitors Affect the Production of Virulence Factors in Cryptococcus Neoformans. Can. J. Microbiol. 2012, 58, 932–936. 10.1139/w2012-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida F.; Wolf J. M.; Casadevall A. Virulence-Associated Enzymes of Cryptococcus Neoformans. Eukaryotic Cell 2015, 14, 1173–1185. 10.1128/ec.00103-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A.; Coelho C.; Alanio A. Mechanisms of Cryptococcus Neoformans-mediated Host Damage. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 855. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vu K.; Tham R.; Uhrig J. P.; Thompson G. R.; Na Pombejra S.; Jamklang M.; Bautos J. M.; Gelli A. Invasion of the Central Nervous System by Cryptococcus Neoformans Requires a Secreted Fungal Metalloprotease. mBio 2014, 5, e01101 10.1128/mBio.01101-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki S.; Ito-Kuwa S.; Nakamura K.; Kato J.; Ninomiya K.; Vidotto V. Extracellular proteolytic activity of Cryptococcus neoformans. Mycopathologia 1994, 128, 143–150. 10.1007/bf01138475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. C.; Blank E. S.; Casadevall A. Extracellular Proteinase Activity of Cryptococcus Neoformans. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1996, 3, 570–574. 10.1128/cdli.3.5.570-574.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi E.; Colombari B.; Francesca Orsi C.; Pinti M.; Troiano L.; Cossarizza A.; Esposito R.; Peppoloni S.; Mussini C.; Neglia R. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) protease inhibitor indinavir directly affects the opportunistic fungal pathogenCryptococcus neoformans. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 187–195. 10.1016/j.femsim.2004.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassone A.; De Bernardis F.; Torosantucci A.; Tacconelli E.; Tumbarello M.; Cauda R. In Vitro and In Vivo Anticandidal Activity of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Protease Inhibitors. J. Infect. Dis. 1999, 180, 448–453. 10.1086/314871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussini C.; Pezzotti P.; Miro J. M.; Martinez E.; de Quiros J. C. L. B.; Cinque P.; Borghi V.; Bedini A.; Domingo P.; Cahn P.; Bossi P.; de Luca A.; d’Arminio Monforte A.; Nelson M.; Nwokolo N.; Helou S.; Negroni R.; Jacchetti G.; Antinori S.; Lazzarin A.; Cossarizza A.; Esposito R.; Antinori A.; Aberg J. A. Discontinuation of Maintenance Therapy for Cryptococcal Meningitis in Patients with AIDS Treated with Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy: an International Observational Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 565–571. 10.1086/381261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos A. L. S.; Braga-Silva L. A. Aspartic Protease Inhibitors: Effective Drugs Against the Human Fungal Pathogen Candida Albicans. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2013, 13, 155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist C. J. A.; Cerutti L.; Hulo N.; Gattiker A.; Falquet L.; Pagni M.; Bairoch A.; Bucher P. PROSITE: a Documented Database Using Patterns and Profiles as Motif Descriptors. Briefings Bioinf. 2002, 3, 265–274. 10.1093/bib/3.3.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen T. N.; Brunak S.; von Heijne G.; Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: Discriminating Signal Peptides from Transmembrane Regions. Nat. Methods 2011, 8, 785–786. 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn B. M. Structure and Mechanism of the Pepsin-like Family of Aspartic Peptidases. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 4431–4458. 10.1021/cr010167q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu D.-Y.; Wu H.-Y.; Yarla N. S.; Xu B.; Ding J.; Lu T.-R. HAART in HIV/AIDS Treatments: Future Trends. Infect. Disord.: Drug Targets 2018, 18, 15–22. 10.2174/1871526517666170505122800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alteri E.; Bold G.; Cozens R.; Faessler A.; Klimkait T.; Lang M.; Lazdins J.; Poncioni B.; Roesel J. L.; Schneider P. CGP 53437, an Orally Bioavailable Inhibitor of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease with Potent Antiviral Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1993, 37, 2087–2092. 10.1128/aac.37.10.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut C.; Stray K.; Tsai L.; Williams M.; Yang Z.-Y.; Cannizzaro C.; Leavitt S. A.; Liu X.; Wang K.; Murray B. P.; Mulato A.; Hatada M.; Priskich T.; Parkin N.; Swaminathan S.; Lee W.; He G.-X.; Xu L.; Cihlar T. In Vitro Characterization of GS-8374, a Novel Phosphonate-Containing Inhibitor of HIV-1 Protease with a Favorable Resistance Profile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1366–1376. 10.1128/aac.01183-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazen R.; Harvey R.; Ferris R.; Craig C.; Yates P.; Griffin P.; Miller J.; Kaldor I.; Ray J.; Samano V.; Furfine E.; Spaltenstein A.; Hale M.; Tung R.; St. Clair M.; Hanlon M.; Boone L. In Vitro Antiviral Activity of the Novel, Tyrosyl-Based Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Type 1 Protease Inhibitor Brecanavir (GW640385) in Combination with Other Antiretrovirals and against a Panel of Protease Inhibitor-Resistant HIV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 3147–3154. 10.1128/aac.00401-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sielecki A. R.; Hayakawa K.; Fujinaga M.; Murphy M.; Fraser M.; Muir A.; Carilli C.; Lewicki J.; Baxter J.; James M. Structure of Recombinant Human Renin, a Target for Cardiovascular-active Drugs, at 2.5 A resolution. Science 1989, 243, 1346–1351. 10.1126/science.2493678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. N. G.; Sielecki A. R.. Aspartic Proteinases and their Catalytic Pathway. In Biological Macromolecules and Assemblies, Vol. 3 Active Sites of Enzymes; Jurnak F. A., McPherson A., Eds.; Wiley: New York, 1987; pp 413–482. [Google Scholar]

- Tang J.; James M. N. G.; Hsu I. N.; Jenkins J. A.; Blundell T. L. Structural Evidence for Gene Duplication in the Evolution of the Acid Proteases. Nature 1978, 271, 618–621. 10.1038/271618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell T. L.; Sewell B. T.; McLachlan A. D. Four-fold Structural Repeat in the Acid Proteases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1979, 580, 24–31. 10.1016/0005-2795(79)90194-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James M. N. G.; Sielecki A. R. Structure and refinement of penicillopepsin at 1.8 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1983, 163, 299–361. 10.1016/0022-2836(83)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L.; Rosenström P. Dali Server: Conservation Mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W545–W549. 10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm L.; Laakso L. M. Dali Server Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 351–355. 10.1093/nar/gkw357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navia M. A.; Fitzgerald P. M. D.; McKeever B. M.; Leu C.-T.; Heimbach J. C.; Herber W. K.; Sigal I. S.; Darke P. L.; Springer J. P. Three-dimensional Structure of Aspartyl Protease from Human Immunodeficiency Virus HIV-1. Nature 1989, 337, 615–620. 10.1038/337615a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R. A.; Swindells M. B. LigPlot+: Multiple Ligand-protein Interaction Diagrams for Drug Discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2011, 51, 2778–2786. 10.1021/ci200227u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett A. J.; Rawlings N. D.; Woessner J. F.. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Elsevier Academic Press: Amsterdam, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mimoto T.; Imai J.; Tanaka S.; Hattori N.; Kisanuki S.; Akaji K.; Kiso Y. KNI-102, a Novel Tripeptide HIV Protease Inhibitor Containing Allophenylnorstatine as a Transition-state Mimic. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1991, 39, 3088–3090. 10.1248/cpb.39.3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hradilek M.; Rinnová M.; Bařinka C.; Souček M.; Konvalinka J.. Analysis of Substrate Specificity of HIV Protease Species. In Peptides for the New Millennium: Proceedings of the 16th American Peptide Symposium June 26–July 1, 1999, Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S.A.; Fields G. B., Tam J. P., Barany G., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2002; pp 474–475.

- Dreyer G. B.; Metcalf B. W.; Tomaszek T. A.; Carr T. J.; Chandler A. C.; Hyland L.; Fakhoury S. A.; Magaard V. W.; Moore M. L.; Strickler J. E. Inhibition of Human Immunodeficiency Virus 1 Protease In Vitro: Rational Design of Substrate Analogue Inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1989, 86, 9752–9756. 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J.; Konvalinka J.; Stehliková J.; Gregorová E.; Majer P.; Souček M.; Andreánsky M.; Fábrys M.; Štrop P. Reduced-bond Tight-binding Inhibitors of HIV-1 Protease Fine Tuning of the Enzyme Subsite Specificity. FEBS Lett. 1992, 298, 9–13. 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80010-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich D. H.; Prasad J. V. N. V.; Sun C. Q.; Green J.; Mueller R.; Houseman K.; MacKenzie D.; Malkovsky M. New Hydroxyethylamine HIV Protease Inhibitors that Suppress Viral Replication. J. Med. Chem. 1992, 35, 3803–3812. 10.1021/jm00099a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinnová M.; Hradilek M.; Bařinka C.; Weber J.; Souček M.; Vondrášek J.; Klimkait T.; Konvalinka J. A Picomolar Inhibitor of Resistant Strains of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Protease Identified by a Combinatorial Approach. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 382, 22–30. 10.1006/abbi.2000.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hradilek M.; Rinnova M.; Barinka C.; Souček M.; Konvalinka J. Synthesis of Library of HIV Proteases Inhibitors. Collect. Symp. Ser. 1999, 3, 79–81. 10.1135/css199903079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J.; Foundling S.; Hemmings A.; Blundell T.; Jones D. M.; Hallett A.; Szelke M. The Structure of a Synthetic Pepsin Inhibitor Complexed with Endothiapepsin. Eur. J. Biochem. 1987, 169, 215–221. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J.; Quail J. W. Structure of theRhizomucor mieheiaspartic proteinase complexed with the inhibitor pepstatin A at 2.7 Å resolution. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 1999, 55, 625–630. 10.1107/s0907444998013961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borelli C.; Ruge E.; Lee J. H.; Schaller M.; Vogelsang A.; Monod M.; Korting H. C.; Huber R.; Maskos K. X-ray structures of Sap1 and Sap5: Structural Comparison of the Secreted Aspartic Proteinases from Candida Albicans. Proteins 2008, 72, 1308–1319. 10.1002/prot.22021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald P. M.; McKeever B. M.; VanMiddlesworth J. F.; Springer J. P.; Heimbach J. C.; Leu C. T.; Herber W. K.; Dixon R. A.; Darke P. L. Crystallographic Analysis of a Complex Between Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Protease and Acetyl-pepstatin at 2.0-A Resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 14209–14219. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)77288-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rut W.; Poręba M.; Kasperkiewicz P.; Snipas S. J.; Drąg M. Selective Substrates and Activity-based Probes for Imaging of the Human Constitutive 20S Proteasome in Cells and Blood Samples. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5222–5234. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poreba M.; Solberg R.; Rut W.; Lunde N. N.; Kasperkiewicz P.; Snipas S. J.; Mihelic M.; Turk D.; Turk B.; Salvesen G. S.; Drag M. Counter Selection Substrate Library Strategy for Developing Specific Protease Substrates and Probes. Cell Chem. Biol. 2016, 23, 1023–1035. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay J.; Dunn B. M. Substrate Specificity and Inhibitors of Aspartic Proteinases. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. 1992, 52, 23–30. 10.3109/00365519209104651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu P.; Takai K.; Weaver V. M.; Werb Z. Extracellular Matrix Degradation and Remodeling in Development and Disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a005058. 10.1101/cshperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majer P.; Urban J.; Gregorová E.; Konvalinka J.; Novek P.; Stehlíková J.; Andreánsky M.; Sedlácek J.; Strop P. Specificity Mapping of HIV-1 Protease by Reduced Bond Inhibitors. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 304, 1–8. 10.1006/abbi.1993.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houštecká R.; Hadzima M.; Fanfrlík J.; Brynda J.; Pallová L.; Hánová I.; Mertlíková-Kaiserová H.; Lepšík M.; Horn M.; Smrčina M.; Majer P.; Mareš M. Biomimetic Macrocyclic Inhibitors of Human Cathepsin D: Structure–Activity Relationship and Binding Mode Analysis. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 1576–1596. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R. L.; Schiering N.; Sedrani R.; Maibaum J. Direct Renin Inhibitors as a New Therapy for Hypertension. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 7490–7520. 10.1021/jm901885s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tykvart J.; Šácha P.; Bařinka C.; Knedlík T.; Starková J.; Lubkowski J.; Konvalinka J. Efficient and Versatile One-step Affinity Purification of In Vivo Biotinylated Proteins: Expression, Characterization and Structure Analysis of Recombinant Human Glutamate Carboxypeptidase II. Protein Expression Purif. 2012, 82, 106–115. 10.1016/j.pep.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung-Chi C.; Prusoff W. H. Relationship between the Inhibition Constant (KI) and the Concentration of Inhibitor which Causes 50 per cent Inhibition (I50) of an Enzymatic Reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099–3108. 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton H. T. S.; Robinson R. A. CXCVIII.-Universal Buffer Solutions and the Dissociation Constant of Veronal. J. Chem. Soc. 1931, 1456–1462. 10.1039/jr9310001456. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. P.; Billings J. A. Kinetic Assay of Human Pepsin with Albumin-bromphenol Blue as Substrate. Clin. Chem. 1983, 29, 447–451. 10.1093/clinchem/29.3.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzman T. F.; Chung C. C.; Edalji R.; Egan D. A.; Gubbins E. J.; Rueter A.; Howard G.; Yang L. K.; Pederson T. M.; Krafft G. A.; Wang G. T. Recombinant Human Prorenin from CHO Cells: Expression and Purification. J. Protein Chem. 1990, 9, 663–672. 10.1007/bf01024761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda Y.; Kageyama T.; Akamine A.; Shibata M.; Kominami E.; Uchiyama Y.; Yamamoto K. Characterization of New Fluorogenic Substrates for the Rapid and Sensitive Assay of Cathepsin E and Cathepsin D. J. Biochem. 1999, 125, 1137–1143. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach M.; Mueller U.; Weiss M. S. The MX Beamlines BL14.1-3 at BESSY II. J. Large-scale Res. Facil. 2016, 2, 47. 10.17815/jlsrf-2-64. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Integration, Scaling, Space-group Assignment and Post-refinement. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 133–144. 10.1107/s0907444909047374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn M. D.; Ballard C. C.; Cowtan K. D.; Dodson E. J.; Emsley P.; Evans P. R.; Keegan R. M.; Krissinel E. B.; Leslie A. G. W.; McCoy A.; McNicholas S. J.; Murshudov G. N.; Pannu N. S.; Potterton E. A.; Powell H. R.; Read R. J.; Vagin A.; Wilson K. S. Overview of theCCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2011, 67, 235–242. 10.1107/s0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vagin A.; Teplyakov A. MOLREP: an Automated Program for Molecular Replacement. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 1022–1025. 10.1107/s0021889897006766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]