Knowledge Into Practice.

Community pharmacists in Canada are able to dispense mifepristone/misoprostol for medical abortion when prescribed by a health professional, such as a physician or nurse practitioner.

Our study demonstrates the usability and acceptability of the newly developed Pharmacist Checklist for Medical Abortion and the Pharmacist Resource Guide for Medical Abortion created by and for pharmacists.

The Pharmacist Checklist for Medical Abortion and the Pharmacist Resource Guide for Medical Abortion have the potential to enhance the timely provision of systematic pharmacist counselling for medical abortion, ensuring patients consistently receive high-quality guidance and support for managing their medical abortion health care needs.

Introduction

In Canada, abortion is a safe, common and legal reproductive health procedure. One in 3 Canadian individuals who become pregnant will experience at least 1 abortion during their reproductive years.1,2 Nevertheless, access to abortion services has not been equitable nationwide.2,3 In 2012, approximately 300 physicians in Canada provided abortion services, predominately surgical abortions (96%), at 94 facilities primarily located in major cities and urban centres.2-4 Patients living outside of urban centres may experience onerous barriers to timely abortion access related to travel, financial disparities and significant wait times.3,5,6 In January 2017, mifepristone 200 mg/misoprostol 800 mcg (Mifegymiso) for medical abortion became available in Canada, offering an opportunity to address inequities in accessing abortion care.3 Internationally, provider training, reduced financial burdens and expanded eligible prescribers (e.g., family physicians, nurse practitioners, etc.) have enhanced the successful implementation and uptake of this innovation.3,7-10 When Health Canada eliminated several restrictions to mifepristone/misoprostol provision,11 including physician-only dispensing and mandatory prescriber training in November 2017, pharmacists became an integral part of abortion provision.12,13 Nevertheless, uptake of mifepristone prescribing across the country continued to be variable3 and pharmacists experienced barriers to providing care to their patients.11

We recognized that novel educational and dispensing resources were needed to support the expanded role of Canadian pharmacists in medical abortion care.3,11 We aimed to develop an effective and efficient Pharmacist Checklist and Resource Guide to promote consistent dispensing of mifepristone and facilitate widespread adoption of medical abortion services in community pharmacy practice.

Methods

Our study is embedded in an observational mixed-methods research program, the Contraception and Abortion Research Team (CART)–Mifepristone Implementation Study.3 Our research approach was guided by user-centred design principles, a well-established method for rapid innovation design with direct input and preferences from “end-users” of a product or service through ideation, rapid prototyping and iterative revisions based upon strengths and weaknesses of prototypes.14,15 We divided development and testing into 2 phases: 1) expert development of pilot prototypes and 2) multimethod usability testing of iterative prototypes (i.e., interviews, surveys) after each of the 3 rounds of revisions.

Phase 1: Checklist and resource guide development

We created the Pharmacist Checklist and Resource Guide prototypes by adapting content from the 2016 Medical Abortion Guidelines by the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC)16 and the Health Canada Product Monograph for Mifegymiso.17 Four CART members, including pharmacist and physician content experts, reviewed prototypes via email. One team member (N.R.) documented recommended modifications, and revised versions were circulated until consensus was reached on user testing materials.

Phase 2: Pharmacist usability testing

We invited practising pharmacists in urban and rural settings within western Canada to participate. We emailed invitations to preidentified content experts and encouraged them to identify eligible peers, using a snowball approach. We performed iterative user testing and revision in 3 rounds: first with pharmacy practice educators, followed by 2 rounds with community pharmacists. After participants provided written informed consent and basic sociodemographic information (age, gender, pharmacy position), we emailed them the Pharmacist Checklist and Resource Guide. We instructed participants to familiarize themselves with the resources and provided close-ended questions for their consideration (e.g., Is the information provided complete?). Pharmacists participated in 30- to 60-minute telephone or in-person interviews with a single interviewer (N.R.). Interviews used a concurrent think-aloud approach developed by Ericsson and Simon,18 encouraging participants to describe their thought process while navigating the materials line by line. Participants were probed with specific questions about content, layout, language and ease of use of the materials as well as the feasibility of implementing the materials into their existing pharmacy workflow. We adapted the interview protocol and probes from our previous user-centred design studies.19,20 Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviewer took detailed field notes and encouraged participants to make notes on the materials and return marked-up copies to the research team. After interview completion, participants verbally responded to a questionnaire comprised of an adapted System Usability Scale (SUS),21 a validated set of 10 statements scored on a 5-point scale used to assess a variety of health care technologies (e.g., decision aids)22-24 and an adjective rating scored on a 7-point scale from “Worst”‘ to “Best imaginable.”25 Total SUS scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating increased user-friendliness.25 We continued collecting data until no new usability issues were identified by participants or the research team.

After each interview, the interviewer reviewed field notes and participant notations to identify usability issues, list modifiable changes and revise the materials as appropriate. At least 1 additional team member reviewed modifications to the study materials to ensure that changes were clinically accurate. We used inductive content analysis to analyze the transcripts, an approach that aims to produce replicable and valid conclusions generating knowledge, novel insights and practical solutions.26 Initially, we used line-by-line coding to identify the scope of usability concepts, followed by focused coding and constant comparison to identify patterns and similarities within and between interviews. Codes were clustered into categories. Categories addressing related concepts were grouped into themes. We calculated demographic statistics and mean SUS and adjective rating scores after each round of testing. Generally, a SUS score above 70 is passable, high-quality scores are 70 to 80 and superior products score above 90.25 The adjective rating scale closely matches the SUS scale and provides a subjective label for a product’s SUS score.25

This study received ethics approval from the University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Results

Twelve participants (2 educators, 10 community pharmacists) from 9 western Canadian communities participated in usability testing between July 2017 and August 2018 (Table 1). The participants’ mean age was 41, half were female and they held a range of community and academic pharmacy positions (e.g., full-time, part-time, pharmacy manager, pharmacy educator).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristics | All participants (n = 12) |

Round 1: Pharmacy practice educators (n = 2) |

Round 2: Community pharmacists (n = 5) |

Round 3: Community pharmacists (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 41 (14) | 50 (3) | 34 (5) | 45 (21) |

| Female, n (%) | 6 (50) | 1 (50) | 4 (80) | 1 (20) |

| Pharmacy position, n (%) | ||||

| Full-time staff pharmacist | 5 (42) | 0 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) |

| Part-time staff pharmacist | 2 (17) | 1 (50) | 0 | 1 (20) |

| Floater pharmacist | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) |

| Store pharmacy manager | 5 (42) | 0 | 2 (40) | 3 (60) |

| Pharmacy owner | 4 (33) | 0 | 2 (40) | 2 (40) |

| Pharmacy educator | 2 (17) | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (20) |

Modifying the pharmacist tools for medical abortion

Table 2 presents findings from the usability questionnaire. The mean SUS scores were similar between community pharmacist evaluations (Round 2: 89.0, SD = 9.1; Round 3: 88.0, SD = 10.7). The mean adjective rating score (Round 2: 6.2, SD = 0.5; Round 3: 5.6, SD = 0.6, where a score of 6 corresponds to “Excellent”) reflected previously reported correlations with mean SUS scores.25

Table 2.

Pharmacist checklist and reference guide usability testing results

|

Modified system usability scale items

(1 = Strongly disagree; 5 = Strongly agree) |

All participants (N = 12) |

Round 1: Pharmacy practice educators (n = 2) |

Round 2: Community pharmacists (n = 5) |

Round 3: Community pharmacists (n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. I think that I would like to use these resources frequently. | 4.7 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.7) | 5.0 (0.0) | 4.4 (1.3) |

| 2. I found these resources unnecessarily complex. | 1.8 (1.3) | 3.0 (2.8) | 1.8 (1.3) | 1.4 (0.6) |

| 3. I think these resources are easy to use. | 4.3 (1.2) | 3.0 (2.8) | 4.6 (0.9) | 4.6 (0.6) |

| 4. I think that I would need the support of an expert to be able to use these resources. | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.0 (0.0) | 2.2 (1.3) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| 5. I found the various components in these resources are well integrated. | 4.1 (1.4) | 3.5 (2.1) | 5.0 (0.0) | 3.4 (1.5) |

| 6. I think these resources are too inconsistent. | 1.4 (0.9) | 2.5 (2.1) | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) |

| 7. I would imagine that most pharmacists would learn to use these resources very quickly. | 4.4 (1.2) | 3.0 (2.8) | 4.8 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.6) |

| 8. I found these resources very awkward to use. | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.0 (0.0) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.6) |

| 9. I feel very confident using these resources. | 4.6 (0.9) | 3.5 (2.1) | 4.8 (0.5) | 4.8 (0.5) |

| 10. I need to learn a lot before I start using these resources. | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.6) |

| Total system usability scale score (items 1 to 10) | 85.6 (16.3) | 71.3 (40.7) | 89.0 (9.1) | 88.0 (10.7) |

| 11. I would rate the overall user-friendliness of this product as (1 = Worst imaginable; 7 = Best imaginable) |

5.6 (1.0) | 4.0 (1.4) | 6.2 (0.5) | 5.6 (0.6) |

Values are expressed as mean (SD).

Content analysis of interview transcripts identified modifiable changes for improving the usability of materials. Two usability themes, “information delivery” and “layout,” were discussed and addressed in subsequent revisions. Appendix 1 (available online at www.cpjournal.ca) summarizes modified items, provides rationale-guiding changes and identifies when feedback leading to major (e.g., addition of new content) and minor (e.g., language use, amount of information) revisions was provided.

Information delivery

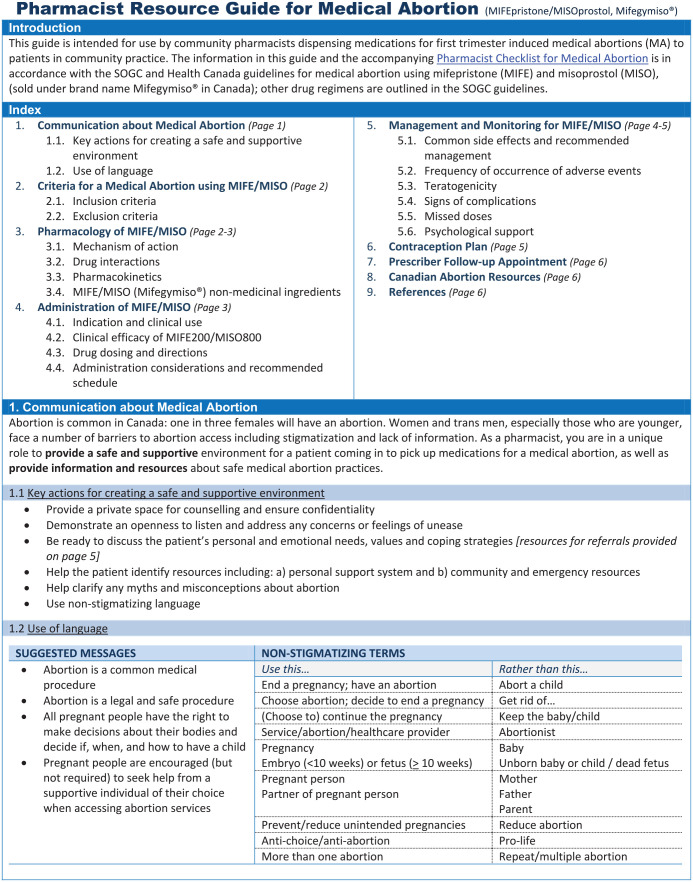

Pharmacists identified 4 categories related to information delivery: 1) content, 2) integration of information between checklist and guide, 3) integration of information with other resources and 4) language use. Pharmacists wanted the Checklist (Figure 1; see online Appendix 2 for French version) to focus on the required protocol for dispensing mifepristone/misoprostol and the Resource Guide (in English and French, Appendix 3 and 4, available online; see Figure 2 for first page of the 6-page document) to provide the rationale for the protocol steps. They wanted content within these resources to reflect information patients receive from other health care sources and recommendations from Canadian health care organizations and governing bodies. Pharmacists appreciated when language reflected pharmacist-specific vocabulary (e.g., NESA: Necessary, Effective, Safe, Adherence) and wanted content to follow a pharmacist’s thought process when systematically reviewing and dispensing prescriptions. After Round 1, the Pharmacist Checklist was subdivided into 4 parts: 1) Pharmacist Prescription Assessment guided by the NESA thought process; 2) Patient Counselling of mifepristone/misoprostol, including directions for use, missed doses and side effect monitoring; 3) Supportive Care Checklist for managing side effects and facilitating patients’ reproductive health goals; and 4) Optional Pharmacist Follow-up. Recommendations for assessing the prescription written date, guidance for managing missed doses and the Health Canada and SOGC indications for use were added to both documents. After Round 2, information to support patient choice of a convenient treatment start date, mifepristone/misoprostol nonmedical ingredients and a comprehensive list of “Canadian Abortion Resources” and support services were added to the Resource Guide. After Round 3, space was added for pharmacist’s notes in the Pharmacist Checklist. An index and information on psychological support were added to the Resource Guide.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Layout

Pharmacists identified 3 categories for visual presentation and content arrangement: 1) amount of information; 2) organization of information; and 3) visual aesthetic. Overall, pharmacists agreed the Checklist should be concise, point form and limited to a single page. The length of the Resource Guide could be longer to ensure inclusion of necessary information. After Round 1, pharmacists approved revisions of the Checklist organization to reflect pharmacists’ systematic thought process and dispensary workflow. After Round 2, pharmacists welcomed revisions of the Resource Guide to reflect the familiar organization of a drug monograph. Pharmacists encouraged the use of checkboxes and tables to organize practical considerations of complex topics (e.g., columns titled “what to expect” and “when to seek help” for side effects management), which were incorporated across several sections of the resources. Major aesthetic revisions were made after Rounds 2 and 3, after pharmacists provided recommendations on using colour, font style and bolded and underlined text to emphasize and organize important ideas.

Implementing the pharmacist tools for medical abortion

Pharmacists identified 3 themes related to facilitators and barriers to mifepristone/misoprostol dispensing in community pharmacies (Appendix 5, available online): 1) usability of the Checklist and Resource Guide; 2) the pharmacist’s role in abortion provision; and 3) implementation of abortion services in community pharmacy practice.

Usability of the Checklist and Resource Guide

Pharmacists understood the intended use of the Checklist was to serve as a complete and concise summary of a pharmacist’s counselling responsibilities when dispensing mifepristone/misoprostol, while the Resource Guide provides background knowledge and rationale for each checklist item. One pharmacist described the resources as “suited for a pharmacist who has not . . . dispensed Mifegymiso [mifepristone/misoprostol]” (Participant 12, Round 3). Pharmacists appreciated the completeness of the resources, as one stated, “I think [the Checklist] has all the necessary information in order for the pharmacists to be able to do what they need to do” (Participant 2, Round 1). Another described the ease of use of these resources: “It’s a nice layout, the Checklist and then if you have any questions about the Checklist content, you can just refer to the Guide” (Participant 10, Round 3). Additionally, community pharmacists emphasised the usefulness of having specific action-oriented steps for counselling patients, as one identified,

It’s nice to have a strict guideline. . . . Then I have confidence in telling them, “You can go [seek immediate help] if this is happening. This is what I mean by heavy bleeding. This is what I mean by a fever.” (Participant 6, Round 2)

Pharmacist’s role in abortion provision

When discussing performing a clinical assessment of the prescription and making therapeutic decisions, participants shared approaches for providing a prescription double-check to ensure it was necessary, effective and safe for the patient. When providing medication counselling, pharmacists described providing a treatment timeline and managing expected side effects, as one articulated, “This is when you can expect stuff to happen. This is how long it should last” (Participant 6, Round 2). When discussing abortion with patients, pharmacists recognized the importance of word choice in respectful health communication and appreciated its inclusion in the Resource Guide, as one pharmacist described,

I also like in your Guide the use of language and the communication about [abortion] because I see so many different situations with so many patients . . . and sensitivity with patients is essential. (Participant 12, Round 3)

Pharmacists described providing a pharmacist follow-up to support patients, noting the importance of obtaining consent for follow-up in this context. Moreover, when providing supportive care and resources, pharmacists appreciated the “Canadian Abortion Resources” in the Resource Guide that can be shared with patients and the “Supportive Care Checklist” in the Checklist summarizing critical nonpharmaceutical items to review with patients (e.g., sanitary pads, contraceptive plan, personal support). One participant noted,

As a pharmacist, this is [information] that probably would have slipped my mind, so I think it’s good that it’s in [the Supportive Care Checklist]. (Participant 7, Round 2)

Finally, pharmacists shared finding innovative methods of supporting patients, including using technology when encountering language barriers, employing telemedicine, shipping medications to patients in remote locations and providing a copy of the Checklist to patients.

Implementation of abortion services in community pharmacy practice

Pharmacists reported feeling underprepared to provide medical abortion. One pharmacist described feeling relieved to have the Checklist available when they first dispensed mifepristone/misoprostol:

I thought the checklist was really helpful. I wasn’t expecting a patient to show up and need me to counsel her . . . so having that checklist there was definitely a good fallback for me. It was very, very informative. (Participant 8, Round 3)

Several pharmacists shared using the resources as educational tools, including one who said, “With the other pharmacists [I trained], I basically gave them the Guide and asked them to read it” (Participant 11, Round 3), describing using the resources to frame discussions about medical abortion provision when training peers. When integrating the resources into their practice, pharmacists described where they would store the materials to facilitate others accessing the resources, including printed copies in a designated folder in the pharmacy, with the medication, or in the counselling room, as well as online files saved on a shared computer server. In larger and busier pharmacies, some pharmacists described designating a pharmacist expert to take charge of dispensing and counselling on medical abortion prescriptions. Pharmacists discussed using the Checklist to document counselling to enable referencing who dispensed the prescription and what was covered during patient counselling. Pharmacists did not foresee documentation becoming a regular part of their workflow unless it was mandated by the College of Pharmacists. Pharmacists identified scheduling time to provide counselling when working alone or in a busy pharmacy and using a private space for counselling, particularly at pharmacies lacking a private counselling area, as potential challenges to creating safe and supportive environments for patient-pharmacist discussions. Moreover, they discussed issues related to working with prescribers, including limited provider training, inadequate communication between providers and pharmacists and the quality of provider counselling to patients. Pharmacists indicated that the “Criteria for Medical Abortion” in the Resource Guide supported their understanding of a patient’s medical abortion care pathway and confirming patients receive the necessary information to make an informed choice.

Discussion

We developed a Pharmacist Checklist and Resource Guide to facilitate pharmacist provision of standardized informative medical abortion counselling to patients. Pharmacists found these resources easy to use and simple to integrate into traditional community pharmacy practice.

Validated usability scores suggest that our final materials are “Excellent” and reflect results from other user-centred design studies that developed and evaluated health care devices and decisions aids.22-24 Qualitative data facilitated our development process, ensured the inclusion of essential content and enhanced the systematic organization of the Checklist to reflect pharmacists’ structured dispensing thought process and the Resource Guide to resemble familiar drug monograph formatting. Iterative revisions allowed for gathering feedback on modifications and finetuning the final resources.

Our interviews elicited opportunities for pharmacists to provide compassionate and comprehensive care beyond simply counselling on medication effects. The Pharmacist Checklist was recognized as a valuable tool for proactively facilitating discussions about timing treatment initiation within a patient’s lifestyle and ensuring a patient has all required treatment supplies when leaving the pharmacy. Inclusive and patient-friendly language within the resources enables the respectful framing of conversations about abortion. Additional Canadian Abortion Resources in the Resource Guide provide helpful information for both health care professionals and patients. Counselling points within the Checklist provide opportunities to empower patients to actively participate in their care. Interventions, such as health professional training and patient decision aids, may improve patient participation and shared decision making.27 Patient participation enables patients to make decisions aligning with their best interest, to share information with their health care provider and to ask for support when needed.28-30 Positive relationships between patients and health care providers lead to better health outcomes, while education and counselling about medical abortion result in improved patient satisfaction.28 These pharmacist resources may be used in combination with the Medical Abortion 101 visual infographic,31 intended to be provided to patients when counselling on what to expect during medical abortion treatment.

Pharmacist interviews revealed barriers and facilitators to incorporating the pharmacy resources into Canadian community pharmacy practice. We found that pharmacists continued to experience barriers to provision even after prescribing restrictions were removed, such as lack of consistent messages from federal (i.e., Health Canada, Ministry of Health) and provincial (e.g., Colleges of Pharmacists and Physicians) regulatory bodies about the pharmacist’s role and responsibilities in mifepristone/misoprostol provision. As medical abortion counselling may require additional time and resources inadequately reflected in a pharmacist’s dispensing fee, our data indicate this may act as an additional barrier to provision for some pharmacists. Ongoing research3,32-35 suggests that 3 years since mifepristone/misoprostol for medical abortion entered the Canadian market in January 2017, uptake continues to be variable across Canada.

Several pharmacy managers in our study reported using the Pharmacist Checklist and Resource Guide to train staff pharmacists for medical abortion provision. Indeed, a strength of our study was our integrated knowledge translation strategy for engaging knowledge users throughout the research process. We provided participating pharmacists permission to use the materials and made the developing tools publicly available on the Canadian Abortion Providers Support website in July 2018 after Round 1 evaluations and modifications. This allowed data collection from pharmacists who used the resources and incorporated them into their practice. Snowball sampling ensured that we recruited pharmacists with diverse exposures to mifepristone/misoprostol dispensing and unique insights into the pharmacist’s role in medical abortion provision. Nevertheless, as we recruited pharmacists practising in western Canadian regions, a limitation of our study was that our sample may not fully incorporate pharmacist experiences in more restrictive regions and provinces,32 such as Québec.33 While our sample size did not allow for hypothesis testing of quantitative data, it reflected the size of similar qualitatively driven studies.22-24 We observed data saturation in Round 3 evaluations with no new modifiable issues identified.

Conclusion

The Pharmacist Checklist and the Pharmacist Resource Guide for Medical Abortion have the potential to enhance the provision of pharmacist counselling for medical abortion in a wide range of practice settings, ensuring patients receive timely information and compassionate medical abortion care. The final products are available in English and French through the Canadian Abortion Providers Support (www.caps-cpca.ubc.ca) and the Canadian Pharmacists Association (www.pharmacists.ca) websites.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Footnotes

Author Contributions:Study initiation (Rebic, Soon, Munro), prototype development (Rebic, Soon), data collection and modifications of the tools (Rebic, Soon), review of the findings (Rebic, Soon, Munro), analysis and interpretation of the data (Rebic, Munro, Norman, Soon), manuscript preparation (Rebic, Munro, Norman, Soon) and manuscript review and approval of the final manuscript (Rebic, Munro, Norman, Soon).

Financial disclosures:This study was supported by a Canadian Institutes for Health Research Partnerships for Health System Improvement grant (PHE Award #148161), in partnership with the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Award #16743). N. Rebic received a CIHR Drug Safety and Effectiveness Cross-Disciplinary Training (DSECT) program award (Award #6443). S. Munro and W.V. Norman are supported as Scholars of the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (Award #18270, Award #2012-5139 [HSR]) and W.V. Norman is an Applied Public Health Research Chair supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CPP-329455-107837).

Funding:This study did not receive industry sponsorship.

ORCID iDs:Nevena Rebic  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6466-5357

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6466-5357

Wendy V. Norman  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4340-7882

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4340-7882

Judith A. Soon  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-3223

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5274-3223

Contributor Information

Nevena Rebic, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Sarah Munro, Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC; Faculty of Medicine, the Centre for Health Evaluation & Outcome Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Wendy V. Norman, Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

Judith A. Soon, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC; Department of Family Practice, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC.

References

- 1. Norman WV. Induced abortion in Canada 1974-2005: trends over the first generation with legal access. Contraception 2012;85(2):185-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Norman WV, Guilbert ER, Okpaleke C, et al. Abortion health services in Canada: results of a 2012 national survey. Can Fam Physician 2016;62(4):e209-17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Norman WV, Munro S, Brooks M, et al. Could implementation of mifepristone address Canada’s urban–rural abortion access disparity: a mixed-methods implementation study protocol. BMJ Open 2019;9(4):e028443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kaposy C. Improving abortion access in Canada. Health Care Anal 2010;18(1):17-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sethna C, Doull M. Spatial disparities and travel to freestanding abortion clinics in Canada. Women’s Studies International Forum 2013;38:52-62. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sethna C, Doull M. Far from home? A pilot study tracking women’s journeys to a Canadian abortion clinic. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007;29(8):640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jones RK, Henshaw SK. Mifepristone for early medical abortion: experiences in France, Great Britain and Sweden. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2002;34(3):154-61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bartlett LA, Berg CJ, Shulman HB, et al. Risk factors for legal induced abortion-related mortality in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2004;103(4):729-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Oppegaard KS, Qvigstad E, Fiala C, Heikinheimo O, Benson L, Gemzell-Danielsson K. Clinical follow-up compared with self-assessment of outcome after medical abortion: a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2015;385(9969):698-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lokeland M, Iversen OE, Engeland A, Okland I, Bjorge L. Medical abortion with mifepristone and home administration of misoprostol up to 63 days’ gestation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2014;93(7):647-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Norman WV, Soon JA. Requiring physicians to dispense mifepristone: an unnecessary limit on safety and access to medical abortion. CMAJ 2016;188(17-18):E429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vogel L. More doctors providing abortion after federal rules change. CMAJ 2018;190(5):E147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights The Politics of Mifegymiso in Canada. Key dates and milestones. Available: https://www.actioncanadashr.org/resources/factsheets-guidelines/2018-11-05-politics-mifegymiso-canada-key-dates-and-milestones (accessed Apr. 2, 2021).

- 14. Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C. A design thinking framework for health care management and innovation. Healthc (Amst) 2016;4(1):11-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kelley T, Littman J. The art of innovation: lessons in creativity from IDEO, America’s leading design firm. New York: Doubleday; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Costescu D, Guilbert E, Bernardin J, et al. Medical abortion. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2016;38(4):366-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linepharma International Limited. Health Canada MIFEGYMISO product monograph. Submission control No: 225430. April 15, 2019. Available: https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00050659.PDF (accessed Apr. 2, 2021).

- 18. Ericsson KA, Simon HA. Protocol analysis: verbal reports as data. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munro S, Hui A, Salmons V, et al. SmartMom text messaging for prenatal education: a qualitative focus group study to explore Canadian women’s perceptions. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2017;3(1):e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munro S, Sou J, Zhang W, et al. Attitudes toward prenatal screening for chromosomal abnormalities: a focus group study. Women Birth 2019;32(4):364-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brooke J. SUS: a “quick and dirty” usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland IL, eds. Usability evaluation in industry. London (UK): Taylor & Francis; 1996:189-94. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li LC, Adam PM, Townsend AF, et al. Usability testing of ANSWER: a web-based methotrexate decision aid for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13(1):131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nair KM, Malaeekeh R, Schabort I, Taenzer P, Radhakrishnan A, Guenter D. A clinical decision support system for chronic pain management in primary care: usability testing and its relevance. J Innov Health Inform 2015;22(3):329-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Trafton J, Martins S, Michel M, et al. Evaluation of the acceptability and usability of a decision support system to encourage safe and effective use of opioid therapy for chronic, noncancer pain by primary care providers. Pain Med 2010;11(4):575-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bangor A, Kortum PT, Miller JT. An empirical evaluation of the system usability scale. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2008;24(6):574-94. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62(1):107-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Légaré F, Turcotte S, Stacey D, Ratté S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID. Patients’ perceptions of sharing in decisions: a systematic review of interventions to enhance shared decision making in routine clinical practice. Patient 2012;5(1):1-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Breitbart V. Counseling for medical abortion. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;183(2):S26-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sanders AR, van Weeghel I, Vogelaar M, et al. Effects of improved patient participation in primary care on health-related outcomes: a systematic review. Fam Pract 2013;30(4):365-78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clayman ML, Bylund CL, Chewning B, Makoul G. The impact of patient participation in health decisions within medical encounters: a systematic review. Med Decis Making 2016;36(4):427-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bancsi A, Grindrod K. Medical abortion: a practice tool for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2019;152(3):160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Devane C, Renner RM, Munro S, et al. Implementation of mifepristone medical abortion in Canada: pilot and feasibility testing of a survey to assess facilitators and barriers. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2019;5(1):126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wagner M-S, Munro S, Wilcox ES, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of first trimester medical abortion with mifepristone in the Province of Quebec: a qualitative investigation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020;42:576-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guilbert E, Wagner M-S, Munro S, et al. Slow implementation of mifepristone medical termination of pregnancy in Quebec, Canada: a qualitative investigation. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2020;25(3):190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Munro S, Guilbert E, Wagner M-S, et al. Perspectives among Canadian physicians on factors influencing implementation of mifepristone medical abortion: a national qualitative study. Ann Fam Med 2020;18(5):413-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-3-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-4-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-5-cph-10.1177_17151635211005503 for Pharmacist checklist and resource guide for mifepristone medical abortion: User-centred development and testing by Nevena Rebic, Sarah Munro, Wendy V. Norman and Judith A. Soon in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada