Abstract

Torus mandibularis is a benign osseous overgrowth arising from the lingual surface of the mandible. It is a common, incidental finding on imaging due to its relatively high prevalence. In the majority of cases, mandibular tori are asymptomatic. We report a novel presentation of a giant torus mandibularis causing bilateral obstruction of the submandibular ducts and consequent sialadenitis. Our patient presented with progressive pain centered in the floor of his mouth and had bilateral submandibular glandular enlargement on exam. Computed tomography showed a giant right torus mandibularis, which was causing obstruction and dilation of the bilateral submandibular ducts. Although conservative management was attempted, he ultimately underwent surgical resection of his torus with symptomatic improvement. This patient highlights a novel complication of torus mandibularis and illustrates successful treatment. Though not previously described, this complication may be underreported and should be considered in the appropriate clinical setting.

Keywords: Salivary duct obstruction, sialadenitis, submandibular duct, submandibular gland, torus mandibularis

Introduction

Torus mandibularis (TM) is a common, normal variant characterized by osseous overgrowth on the lingual aspect of the mandible. TM has an estimated prevalence of 7–10% in the United States, although some studies have found a prevalence as high as 16–33% in various other patient groups.1,2 In particular, it appears to occur more commonly in Asian populations and males. Several studies have also found an association between bruxism and TM.3 Overall, TM is likely to be associated with a variety of genetic and behavioral factors.4 Not surprisingly, TM is a common incidental finding in head and neck imaging. Typical imaging features include densely mineralized bone arising from the lingual mandible, which may or may not have an associated medullary cavity. Histologically, TM is typically described as an osseous exostosis consisting of hyperplastic bone with mature cortical and trabecular elements.

TM is a generally benign and inconsequential finding. In rare instances, the presence of TM can actually be beneficial to patients. For instance, these lesions can potentially be used as a source for autologous bone graft harvesting in patients with periodontal osseous defects.5 Conversely, some tori can be symptomatic. For example, one study found that TM can worsen the severity of obstructive sleep apnea.6

We report an unusual presentation of a large TM causing bilateral submandibular duct obstruction, leading to sialadenitis of the submandibular glands. To our knowledge, this complication of TM has not previously been reported.

Patient presentation and work-up

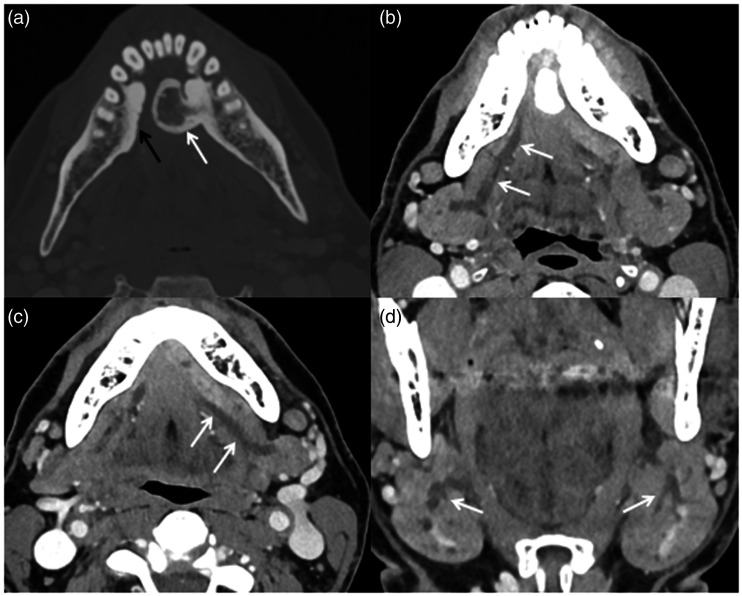

A 58-year-old male presented to the emergency department with several days of pain and swelling centered in the floor of his mouth. He endorsed 2–3 months of more mild, progressive jaw pain and submandibular swelling prior to this, resulting in a 20 lb. weight loss due to avoidance of chewing. Physical exam revealed a large palpable bump on the floor of his mouth as well as enlargement and fluctuance of both submandibular glands. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck was obtained, which demonstrated a large left and small right TM (Figure 1(a)). The large left TM caused extrinsic compression of the bilateral submandibular ducts (Figures 1(b) and (c)). This resulted in upstream bilateral ductal and submandibular glandular enlargement (Figures 1(b) to (d)). There was no evidence of sialolithiasis or other obstructive etiology. On review of a previous neck CT done 6 years earlier, it was apparent that the left torus had enlarged in the interval (Figure 2). However, the patient had no symptoms of sialadenitis or ductal dilation at the time of his prior imaging.

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced CT at the level of the mandible windowed for bone: (a) demonstrates a large left torus mandibularis (white arrow) and a small right torus mandibularis (black arrow). Additional images windowed for soft tissue show dilation of (b) the right (arrows) and (c) left (arrows) submandibular ducts. (d) This ductal dilation extended into both submandibular glands (arrows).

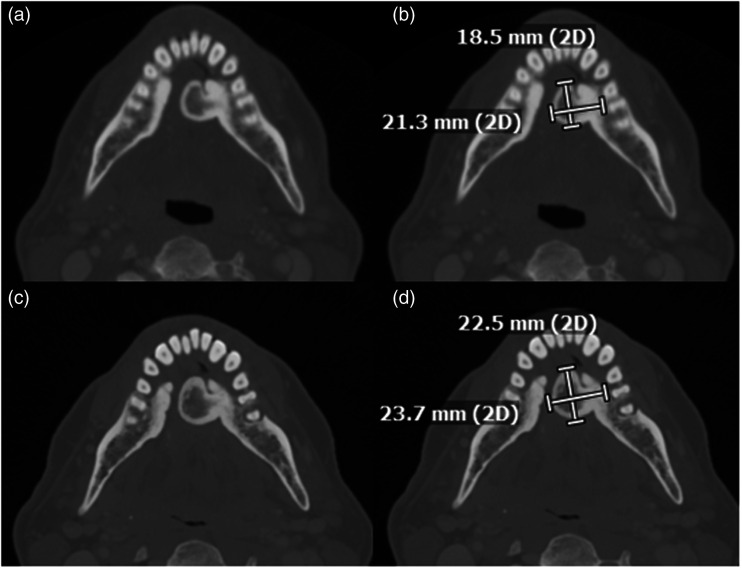

Figure 2.

Axial CT at the level of the mandible, obtained 6 years prior to the patient’s presentation: (a) without and (b) with annotated measurements, again show a left torus mandibularis. Images at the level of the mandible at the same level at the time of the patient’s presentation: (c) without and (d) with annotated measurements are shown for comparison. There is mild growth of the right torus mandibularis over the imaging interval.

The patient was diagnosed with bilateral sialadenitis of the submandibular glands resulting from extrinsic ductal obstruction related to his large left TM. He was initially discharged home on a short course of oral steroids and instructed to employ frequent glandular massage and to use sialogogues. His symptoms continued over the next 2 weeks despite conservative therapy, and ultimately surgical management was recommended. He underwent resection of his large left and small right mandibular tori without complication and had symptomatic improvement. The patient returned a year later for new left lower facial swelling and was clinically diagnosed with a dental abscess, which was successfully treated with antibiotics. Since that time, he has had no recurrent symptoms.

Discussion

We report a novel presentation of bilateral sialadenitis due to submandibular duct obstruction from a giant TM. To our knowledge, neither sialadenitis nor salivary duct obstruction have been previously reported as complications of TM.

Sialadenitis refers to inflammation of the salivary glands and has a variety of potential causes, including infection, ductal obstruction, radiation, trauma, and numerous inflammatory disorders such as IgG4 related disease.7 The etiology can also be multifactorial. For example, salivary duct obstruction may lead to superimposed infection. The submandibular glands are more commonly affected compared to other salivary glands, which is likely to be due to the upward course of their ducts and relatively viscous secretions, both of which predispose them to sialolithiasis. Aside from sialoliths, extrinsic lesions such as tumors, sialoceles, or even dentures can also cause duct obstruction.8

Imaging plays an important role in the evaluation of sialadenitis, particularly with regard to identifying any obstructing lesion or complication such as abscesses. CT and ultrasound are commonly employed for these purposes.7 CT findings of sialadenitis are variable but can include salivary gland enlargement, heterogeneous attenuation or enhancement, and periglandular fat stranding. When complicated by infection, abscesses may be present. Ultrasound typically demonstrates enlarged and hypoechoic glands. Both modalities can reveal ductal dilation and sialolithiasis, though CT is usually more effective in identifying extrinsic lesions or distal stones.7,9 For this reason, CT is more commonly employed at our institution, particularly when there is clinical suspicion of unusual etiologies or abscesses.

Treatment of sialadenitis depends on the etiology and may include salivary gland massage, hydration, and sialogogues. These measures can even be effective in obstructive cases due to small sialoliths, though large stones or those refractory to conservative measures sometimes require lithotripsy or sialendoscopic removal. Cases related to extrinsic obstruction require a more individualized approach based on specific etiology. In our patient, conservative treatment was insufficient and surgical resection of his tori was required.

While it is evident that our patient’s ductal dilation and sialadenitis were due to mechanical obstruction from his large TM, it is less clear what led to his subacute development of symptoms over 2–3 months. Based on his prior imaging, he had had a large TM for at least 6 years. This initially was not causing any imaging evidence of duct obstruction, and he was asymptomatic for most of this time. It is notable that his imaging did show mild interval enlargement of his TM at the time of presentation. Thus, we speculate that the lesion reached a threshold size such that external pressure exceeded the compliance of the submandibular ducts, eventually causing obstruction that was symptomatic. It is also conceivable that a separate infectious or inflammatory process exacerbated an otherwise compensated state, though he had no clinical evidence to suggest this, and his CT showed no substantial inflammatory change outside of the submandibular glands. His clinical improvement after resection of the TM confirmed that his symptoms were mainly related to mechanical duct obstruction. Identification of any similar cases would be helpful to elucidate the potential association between TM, duct obstruction, and sialadenitis and to further understand the pathophysiology.

Conclusion

We have described a presentation of a giant TM causing submandibular duct obstruction and sialadenitis. Several learning points can be gleaned from our patient. First, we have shown that large mandibular tori can cause submandibular duct obstruction, which has not been previously demonstrated. Second, surgical consultation for potential resection should be considered in patients with this presentation. Our patient did not have any substantial clinical improvement with the conservative measures that are often effective for sialolithiasis, which is not surprising given that his symptoms were related to extrinsic ductal compression. Finally, it is interesting that our patient had a slowly growing TM that was previously asymptomatic for years. There may be a role for close clinical follow-up of patients with large tori who have not yet developed symptoms. Further study would be needed to define the appropriateness of any such clinical follow-up.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for medical images and records to be used for research purposes.

ORCID iDs: Ajay A Madhavan https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1794-4502

Jared T Verdoorn https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1592-1182

References

- 1.Chaubal TV, Bapat R, Poonja K. Torus mandibularis. Am J Med 2017; 130: e451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruprecht A, Hellstein J, Bobinet K, et al. The prevalence of radiographically evident mandibular tori in the University of Iowa dental patients. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2000; 29: 291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auskalnis A, Rutkunas V, Bernhardt O, et al . Multifactorial etiology of torus mandibularis: study of twins. Stomatologija 2015; 17: 35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seah YH. Torus palatinus and torus mandibularis: a review of the literature. Aust Dent J 1995; 40: 318–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hassan KS, Al-Agal A, Abdel-Hady AI, et al. Mandibular tori as bone grafts: an alternative treatment for periodontal osseous defects – clinical, radiographic and histologic morphology evaluation. J Contemp Dent Pract 2015; 16: 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn SH, Ha JG, Kim JW, et al. Torus mandibularis affects the severity and position-dependent sleep apnoea in non-obese patients. Clin Otolaryngol 2019; 44: 279–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel Razek AAK, Mukherji S. Imaging of sialadenitis. Neuroradiol J 2017; 30: 205–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aframian DJ, Lustmann J, Fisher D, et al. An unusual cause of obstructive sialadenitis. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 2001; 30: 226–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burke CJ, Thomas RH, Howlett D. Imaging the major salivary glands. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011; 49: 261–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]