Significance

Alternative end joining (A-EJ) is implicated in oncogenic translocations and mediating DNA double-strand-break (DSB) repair in cycling cells when classical nonhomologous end-joining (C-NHEJ) factors of the C-NHEJ ligase complex are absent. However, V(D)J recombination-associated DSBs that occur in G1 cell cycle-phase progenitor lymphocytes are joined exclusively by the C-NHEJ pathway. Until now, however, the overall mechanisms that join general DSBs in G1-phase progenitor B cells had not been fully elucidated. Here, we report that Ku, a core C-NHEJ DSB recognition complex, directs repair of a variety of different targeted DSBs toward C-NHEJ and suppresses A-EJ in G1-phase cells. We suggest this Ku activity explains how Ku deficiency can rescue the neuronal development and embryonic lethality phenotype of ligase 4-deficient mice.

Keywords: end joining, DSB repair, Cas9, G1 phase, V(D)J recombination

Abstract

Classical nonhomologous end joining (C-NHEJ) repairs DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) throughout interphase but predominates in G1 phase when homologous recombination is unavailable. Complexes containing the Ku70/80 (“Ku”) and XRCC4/ligase IV (Lig4) core C-NHEJ factors are required, respectively, for sensing and joining DSBs. While XRCC4/Lig4 are absolutely required for joining RAG1/2 endonuclease (“RAG”)-initiated DSBs during V(D)J recombination in G1-phase progenitor lymphocytes, cycling cells deficient for XRCC4/Lig4 also can join chromosomal DSBs by alternative end-joining (A-EJ) pathways. Restriction of V(D)J recombination by XRCC4/Lig4-mediated joining has been attributed to RAG shepherding V(D)J DSBs exclusively into the C-NHEJ pathway. Here, we report that A-EJ of DSB ends generated by RAG1/2, Cas9:gRNA, and Zinc finger endonucleases in Lig4-deficient G1-arrested progenitor B cell lines is suppressed by Ku. Thus, while diverse DSBs remain largely as free broken ends in Lig4-deficient G1-arrested progenitor B cells, deletion of Ku70 increases DSB rejoining and translocation levels to those observed in Ku70-deficient counterparts. Correspondingly, while RAG-initiated V(D)J DSB joining is abrogated in Lig4-deficient G1-arrested progenitor B cell lines, joining of RAG-generated DSBs in Ku70-deficient and Ku70/Lig4 double-deficient lines occurs through a translocation-like A-EJ mechanism. Thus, in G1-arrested, Lig4-deficient progenitor B cells are functionally end-joining suppressed due to Ku-dependent blockage of A-EJ, potentially in association with G1-phase down-regulation of Lig1. Finally, we suggest that differential impacts of Ku deficiency versus Lig4 deficiency on V(D)J recombination, neuronal apoptosis, and embryonic development results from Ku-mediated inhibition of A-EJ in the G1 cell cycle phase in Lig4-deficient developing lymphocyte and neuronal cells.

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) arise from sources both intrinsic and extrinsic to the cell, and improper DSB repair can lead to genomic instability and oncogenic translocations. To resolve DSBs, mammalian cells largely use two major classes of repair pathways: classical nonhomologous end joining (C-NHEJ), which is active throughout interphase, and homology-directed repair (HDR), which is only active in S/G2 cell cycle phases (1, 2). In the absence of C-NHEJ, cycling cells have been found to also join DSBs by an alternative end-joining pathway or pathways (1).

Programmed, cell-intrinsic DSBs are generated during V(D)J recombination in developing B and T lymphocytes. V(D)J recombination assembles V, D, and J gene segments into variable region exons within antigen receptor loci of lymphocyte progenitors during the G1 cell cycle phase (3). The RAG1/2 (RAG) endonuclease is recruited to a recombination center in antigen receptor loci (3, 4), where it binds recombination signal sequence (RSS) located adjacent to V, D, and J gene segments in one of its two active sites (5, 6). Then, the single RSS-bound RAG linearly scans long-range distances of adjacent chromatin in the locus, presented by cohesin-mediated loop extrusion, for compatible RSSs with which to mediate cleavage (4, 7–13). Once two RSSs are appropriately paired, RAG cleaves between the two sets of RSSs and their coding ends (CEs) to form RSS and CE DSB ends that are held in a postcleavage synaptic complex (14). Joining of cleaved RSS ends to each other and coding ends to each other, respectively, is subsequently carried out exclusively by C-NHEJ (15, 16), potentially due to RAG shepherding the broken ends specifically into the C-NHEJ pathway (17, 18). V(D)J recombination end-specific joining is unlike most chromosomal translocations or deletions (involving, for example, Cas9:gRNA or other types of DSBs) in which a given DSB end can join to either DSB end of the other DSB (19, 20).

C-NHEJ contains the “core” factors Ku70/Ku80 (Ku), which form the DSB recognition complex, as well as XRCC4/ligase IV (Lig4), which forms the DSB ligation complex. Core C-NHEJ factors are necessary for joining CEs and RSS ends during V(D)J recombination in G1-phase developing lymphocyte progenitors; accordingly, mice deficient in core C-NHEJ factors exhibit a severe combined immune deficiency (SCID) due to defective repair during V(D)J recombination (15, 16). However, Ku70-deficient mice can have a “leaky” SCID when compared to a complete SCID in XRCC4/Lig4-deficient mice, consistent with a low level of V(D)J recombination-like joining in the absence of Ku (21). Deficiency in core C-NHEJ factors also leads to substantial p53-dependent apoptosis of newly generated postmitotic neurons (22–24); however, the impact of Ku deficiency on neuronal apoptosis is not nearly as severe as that of XRCC4 or Lig4 deficiency (25).

As defined in the context of core C-NHEJ deficiency, cycling mammalian cells can also access an alternative end-joining (A-EJ) pathway (or pathways) to relatively robustly join DSB ends generated via translocations or during immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) class switch recombination (CSR) in mature B cells (26–28). A-EJ also joins chromosomally I-SceI-generated DSBs in cycling mammalian cell lines (29, 30), fuses dysfunctional telomeres (31), and promotes translocations to replication stress-enhanced recurrent DSB clusters in neural stem and progenitor cells (32). Implicated A-EJ factors include: Parp1, XRCC1/ligase III (31, 33), Pol θ (34, 35), and RAD52 (36). Recent studies have also implicated Pol θ as specifically involved in A-EJ in the S/G2 phase (37). Cumulatively, studies of A-EJ have not fully addressed all contexts through which cells commit to A-EJ versus C-NHEJ (37–43). In the context of V(D)J recombination, the postsynaptic RAG complex itself has been implicated in shepherding V(D)J RSS and coding end DSBs into the C-NHEJ versus A-EJ pathways in G1-phase progenitor B cell lines (16–18). However, whether RAG-generated DSBs can translocate to more general DSBs or whether repair of general DSBs in G1-arrested progenitor B cells can employ A-EJ have remained to be determined (37).

XRCC4- or Lig4-deficient mice succumb to embryonic lethality, which along with their severe neuronal apoptosis is rescued by p53 deficiency, with rescue of neuronal development and embryonic development potentially occurring by rescue of newly generated Lig4- and XRCC4-deficient neurons from p53-dependent apoptosis in the presence of large numbers of unrepaired DSBs (22, 23). In contrast, Ku-deficient mice do not have an embryonic lethal phenotype and, correspondingly, exhibit a much milder neuronal apoptosis phenotype (21, 25, 44). Notably, Ku deficiency rescues the embryonic lethality of Lig4-deficiency mice and has related effects in cell lines (45, 46). In this context, Ku binding to unrepaired breaks in the context of Lig4- or XRCC4-deficient newly generated neurons has been speculated to suppress their ability to repair persistent DSBs by A-EJ, thereby promoting their apoptotic cell death (15, 47). As DSBs can be substantially joined by A-EJ in cycling Lig4- or XRCC4-deficient cells (26, 29), such Ku-dependent down-regulation of A-EJ could in theory have more impact in noncycling cells such as neurons and G1-phase progenitor B cells.

To ascertain whether additional mechanisms that might restrict joining of RAG-initiated DSBs and determine whether joining of other types of DSBs is also restricted in the G1 cell cycle phase, we mapped RAG-, Cas9:gRNA- and Zinc finger nuclease-generated DSB repair fates in G1-arrested v-Abl-transformed progenitor B cell lines through a version of our linear amplification-mediated, high-throughput, genome-wide translocation sequencing (LAM-HTGTS) (48), modified to map “bait” DSB rejoining at single nucleotide resolution.

Results

Repair of Cas9:gRNA DSBs in G1.

We derived two independent clonal wild-type (WT) v-Abl-transformed progenitor B cell lines (Abl lines) designated “WT A” and “WT B” Abl lines, respectively (Methods). We derived clonal “Ku70−/−A1” and “Lig4−/−A1” Abl lines from WT A and “Ku70−/−B1” and “Lig4−/−B1” from WT B Abl lines, respectively, (Methods). We also obtained two independent Lig4-deficient (Lig4−/−) Abl lines (49, 50), which we termed “Lig4−/−C” and “Lig4−/−D” lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–G). As reported in earlier studies (21) loss of Ku70 decreases Ku80 protein to virtually undetectable levels, resulting in a complete loss of the Ku complex (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and E). Treatment with Abl kinase inhibitor (STI-571) for all Abl lines described causes G1 arrest, induction of RAG expression, and V(D)J recombination at endogenous antigen receptor loci, including the Ig kappa (Igκ) locus with Abl lines surviving under G1 arrest throughout experiments due to the Eμ-Bcl2 transgene present in the original A and B wild-type lines (49).

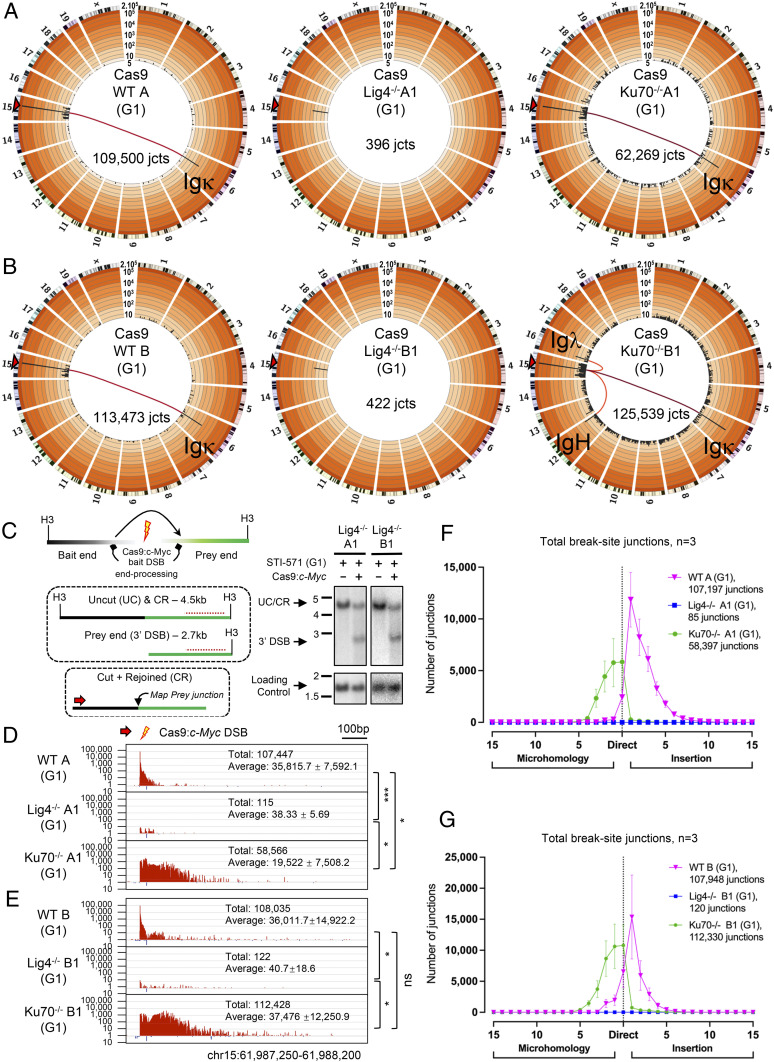

We introduced a Cas9:guide RNA (gRNA) bait DSB targeting the first intron of c-Myc (7) in G1-arrested Abl cells and employed HTGTS-JoinT-seq (HTGTS-based reJoining and Translocation sequencing) (SI Appendix, Methods) to measure genome-wide “prey” translocations from the 5′ bait DSB broken end and to measure imperfect rejoining of the 5′ bait DSB to its corresponding 3′ broken end, both at single nucleotide resolution. The use of a modified pipeline was necessary, given that the original LAM-HTGTS translocation pipeline (48) detects only very few imperfectly rejoined bait DSB junctions in G1-arrested WT Abl cells due to limited resection in the G1 phase (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A–C). We performed three independent replicates of experiments for each line assayed, for a combined total of ∼100,000 junctions from each WT Abl line (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Table S1). Genome-wide plots from the Cas9:c-Myc bait for each G1-arrested, WT A and B Abl cells displayed three distinct junction groups: 1) bait DSB ends rejoined to each other (i.e., the bait break site); 2) recurrent translocations to RAG-initiated DSBs in antigen receptor loci; and 3) low-level, widespread translocations (15, 20) (Fig. 1 A and B). As predicted, the majority of recovered junctions from G1-arrested WT A and WT B Abl cells involved rejoining of the bait DSB ends (∼97% of total junctions) with a limited mean resection distance (<1 bp) (Fig. 1 A–E and SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2). In this regard, rejoined junctions predominantly harbored small insertions (∼70 to 90%), consistent with known polymerases that work with C-NHEJ (51–54), with the remaining junctions being either direct joins (5 to 20%) or employing short microhomologies (MHs) (1 to 10%) (Fig. 1 F and G). Given the very high proportion of bait DSB rejoins relative to translocations, we have focused here on rejoining outcomes of the bait DSB ends except for internal RAG-generated DSB Igκ locus joining, which occurs more frequently.

Fig. 1.

Disparate G1-arrested A-EJ outcomes of Cas9:c-Myc DSBs from specific core C-NHEJ deficiencies. (A and B) Genome-wide prey junctions from independently derived WT A and B, Lig4−/−A1 and B1, and Ku70−/−A1 and B1 Abl lines are binned into 5-Mb regions (black bars) and plotted on Circos plots displaying a 1/2/5 increment log10 scale (20). Bar height indicates junction frequency. Frequency ranges are colored by order of magnitude from very light (<10) to dark orange (>105). The light-to-dark red tone lines connecting the bait break to Ig loci represent translocation hotspots of greater significance. Circos plots are from pooled libraries after normalization, with total junctions indicated (n = 3 for each clone; see SI Appendix, Table S1). (C) Left: Diagram of Cas9:c-Myc bait DSB locus (Upper) with Southern fragments (H3 = HindIII) detected by probe (Middle; red dashed line) and HTGTS-JoinT-seq emphasizing cut + rejoined junctions (Lower; red arow = bait primer). Right: Southern for Lig4−/−A1 and B1 clones; cutting and G1 arrest are indicated. (D and E) Bait break-site profiles for clone set A (D) and B (E). Junctions in both (+) (red) and (−) (blue) chromosome orientations plotted on log10 scale from pooled libraries indicated by total and average junction numbers (n = 3 for each clone, mean ± SD; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant). (F and G) Microhomology and insertion utilization of bait break-site junctions are plotted with indicated lengths (n = 3 for each clone, mean ± SD).

Lig4−/−A1 and Lig4−/−B1 Abl cells were G1 arrested and then expressed with Cas9:c-Myc to measure repair in the absence of C-NHEJ. Strikingly, we recovered very few junctions with the total being 100- to 1,000-fold fewer than the number recovered from WT clones and approaching background levels (Fig. 1 A–E and SI Appendix, Table S1). Southern blotting analyses of the Cas9:c-Myc bait break site revealed little change in the germline band, consistent with dominant rejoining with limited resection; however, a substantial fraction of the c-Myc alleles in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells were present as unjoined DSB ends (Fig. 1C and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C), demonstrating substantial bait site cutting but little rejoining in the latter. Retroviral complementation of Lig4−/−A1 Abl cells with Lig4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B) restored joining patterns, junction structures, and median resection distance similar to those observed in WT (Fig. 2 A–C and SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2) and, correspondingly, with a decreased level of Cas9:c-Myc bait broken ends as detected by Southern blotting (SI Appendix, Fig. S3D). Finally, cycling WT A and Lig4−/−A1 Abl cells robustly rejoined the Cas9:c-Myc bait DSB ends. The majority of junctions from cycling WT A harbored short insertions over a mean resection distance of ∼70 bp, whereas cycling Lig4−/−A1 were nearly all short MHs over a mean resection distance of ∼300 bp (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B and Tables S1 and S2), and no discernable change was observed in the Southern blot band harboring Cas9:c-Myc bait DSB (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). We conclude that the inability to rejoin in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells is specific to both the absence of Lig4 and the G1 cell cycle phase.

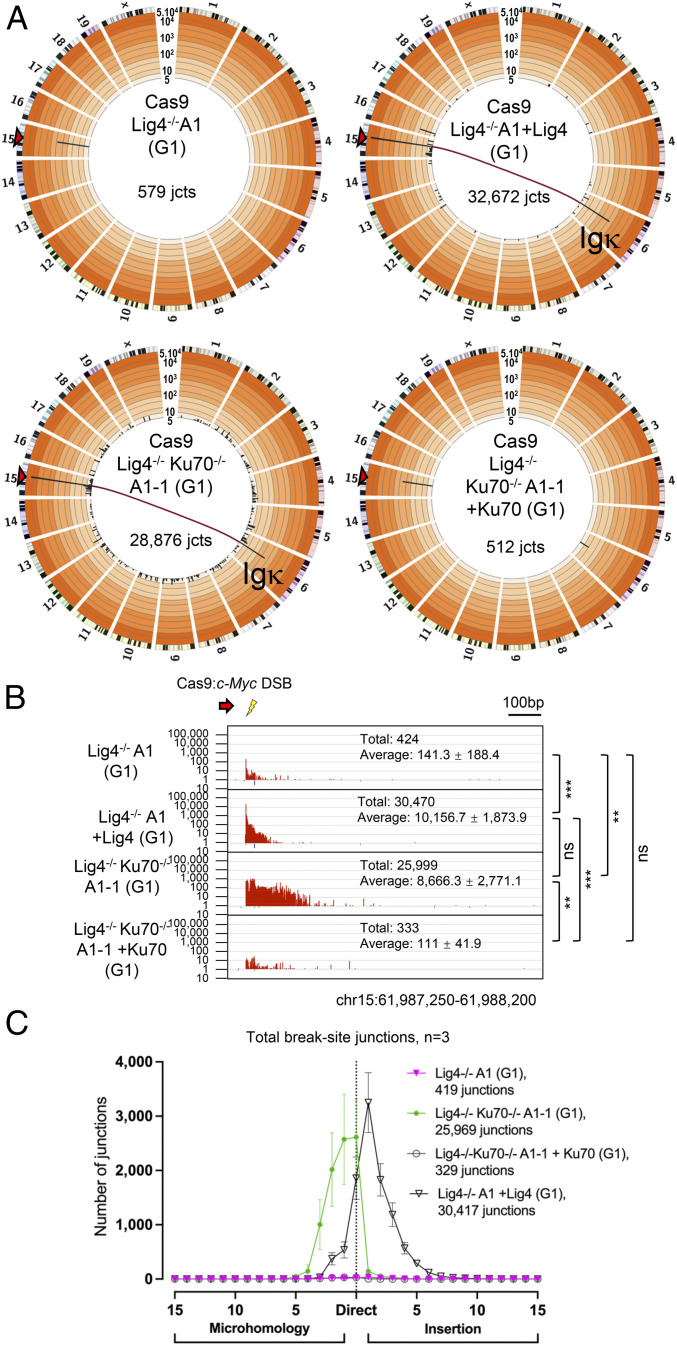

Fig. 2.

Ku70 suppresses the rejoining and translocation of Cas9:c-Myc DSBs in Lig4-deficient G1-arrested Abl cells. (A) Genome-wide prey junctions from Cas9:c-Myc bait DSBs displayed as Circos plots (see Fig. 1 legend; SI Appendix, Table S1) for G1-arrested Lig4−/−A1, Lig4−/−A1 +Lig4, Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1, and Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1 +Ku70 Abl cells. (B) Bait break-site junction profiles for Abl lines described in A. Junctions are plotted similarly to Fig. 1D (n = 3 for each clone; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; see Fig. 1 legend). (C) Microhomology and insertion usage of break-site junctions are plotted with indicated lengths (n = 3 for each clone, mean ± SD) for the Abl lines and conditions described in A.

Ku deficiency has differential impacts on organismal development compared to XRCC4/Lig4 deficiency (21, 55). Thus, we evaluated A-EJ of Cas9:c-Myc DSBs in G1-arrested Ku70−/−A1 and B1 Abl cells. Contrary to the near complete absence of A-EJ in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells, Ku-deficient A-EJ was robust with recovered junctions at similar to slightly lower levels than that of WT Abl cells (Fig. 1 A and B and SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2). Notably, Ku deficiency increased the mean resection distance of bait DSB rejoined junctions (to ∼45 bp) compared to WT Abl cells (SI Appendix, Table S2). Despite the robust G1-arrested Ku70−/− A-EJ (Fig. 1 D and E), Southern blotting analysis displayed substantial unrepaired bait DSB ends (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A–C). Ku-deficient rejoined junction structures predominantly consisted of small MHs (∼66%), but with a high fraction of direct joins (∼30%) (Fig. 1 F and G).

Because Ku deficiency can rescue the embryonic lethality of Lig4 deficiency (45), we hypothesized that the presence of Ku in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells may block access of DSBs to A-EJ (15). To test this, we deleted Ku70 from Lig4−/−A1 and C Abl cell lines (generating Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1 and C1 lines) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and E) and assayed rejoining outcomes. Indeed, loss of Ku70 in Lig4−/− Abl cell lines fully restored G1-phase joining patterns (e.g., increased resection, rejoining of bait ends, and direct junction utilization) to those observed in G1-arrested Ku70−/−A1 and B1 Abl cells (Fig. 2 A–C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 A and B and S6 A–C and Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, complementation of Ku70 in Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1 and C1 Abl cell lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E), suppressed repair levels ∼100-fold, to low levels that approached those of G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cell lines (Fig. 2 A–C and SI Appendix, Figs. S5 A and B and S6 A–C and Table S1), demonstrating that rejoining suppression was indeed Ku70 specific. We conclude that in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells, A-EJ for Cas9 DSBs is suppressed by the Ku C-NHEJ DSB recognition complex.

Repair of 5′ Overhangs in G1.

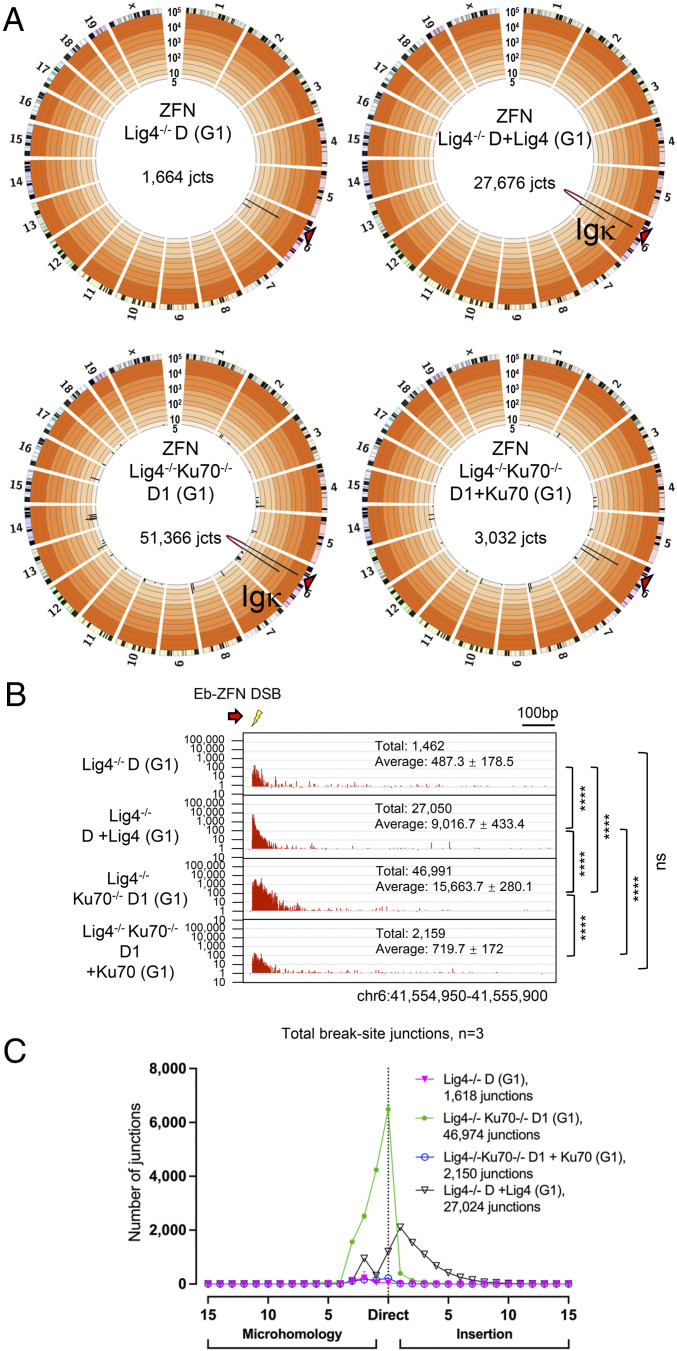

To determine whether DSB repair differences between C-NHEJ and A-EJ proficient backgrounds extend beyond repair of blunt DSB ends, we employed Lig4−/−D Abl cells, which harbor a doxycycline-inducible zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) that targets the TCRβ locus enhancer on chromosome 6 (Eb-ZFN) (50). Upon doxycycline treatment, the ZFNs generate DSBs containing 4-bp-long 5′ overhang ends (56). We then generated a WT equivalent control by retroviral expression of Lig4 in these Lig4−/−D Abl cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F). G1-arrested Lig4−/−D Abl cells displayed ∼20-fold fewer total junctions from Eb-ZFN-induced DSBs than their Lig4-complemented G1-arrested counterparts (Fig. 3 A and B), and, unlike their Lig4-complemented G1-arrested counterparts, accumulated substantial levels of unrepaired broken ends (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B). Notably, although at low levels, significant numbers of junctions from Eb-ZFN expressing G1-arrested Lig4−/−D Abl cells were recovered (Figs. 1 A–E and 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Table S1). Furthermore, junctions recovered from the G1-arrested Lig4-complemented Lig4−/−D Abl cells again predominantly contained short insertions with a limited mean resection distance (5 bp) similar to rejoined Cas9:c-Myc bait DSB ends in WT Abl cells (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2).

Fig. 3.

A-EJ of short 5′ overhangs from ZFN cleavage are suppressed by Ku in Lig4-deficient G1-arrested Abl cells. (A) Genome-wide prey junctions from doxycycline-induced Eb-ZFN Lig4−/−D, Lig4−/− +Lig4, Lig4−/−Ku70−/−D1, and Lig4−/−Ku70−/−D1 +Ku70 Abl cells displayed on Circos plots (see Fig. 1 legend; SI Appendix, Table S1). (B) Induced Eb-ZFN bait break-site junction profiles from the G1-arrested Abl lines described in A (n = 3 for each clone; one-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test, ****P < 0.0001; see Fig. 1 legend). (C) Microhomology and insertion usage of Eb-ZFN break-site junctions from the Abl lines described in A are plotted with indicated lengths (n = 3 for each clone, data represent mean ± SD).

To examine the influence of Ku on Eb-ZFN-generated DSBs, we deleted Ku70 from two separate clones of Lig4−/−D Abl cells to generate Lig4−/−Ku70−/−D1 and D2 Abl lines, which led to an ∼20- to 30-fold increase in Eb-ZFN junctions recovered in the presence of Eb-ZFN; in this context, rejoined bait DSB junction structures predominantly contained short MHs (70%) but also had substantial numbers that were direct (30%), consistent with Cas9:c-Myc bait findings (Fig. 3 A–C and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 C and D and S8 A–C and Table S1). Correspondingly, ectopic expression of Ku70 in Lig4−/−Ku70−/−D1 and D2 Abl lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S1G), in the presence of Eb-ZFN, decreased junction numbers to levels comparable to Lig4−/−D Abl cells (Fig. 3 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S7 C and D and S8 A–C and Table S1). Collectively, we conclude that the inability to repair DSBs in G1-arrested Lig4−/− Abl cells, due to Ku suppression of A-EJ, also largely applies to ends with short 5′ overhangs.

A-EJ of RAG-Initiated DSBs.

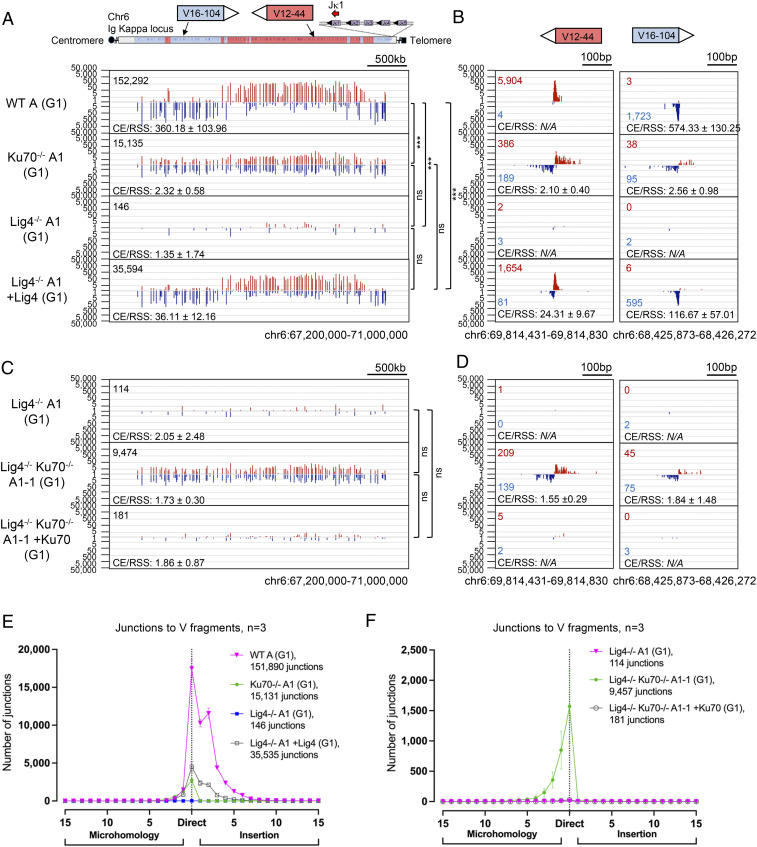

Given that Ku suppresses A-EJ for Cas9 and ZFN DSBs (above) and that Ku70−/− mice can display a leaky SCID phenotype (21), we revisited the extent to which A-EJ participates in a V(D)J recombination-like process. Thus, we employed HTGTS-V(D)J-sequencing (seq) to measure the joining of the Jκ1 CE to other potential bait DSB ends, which includes the ∼130-Vκ gene segment CEs and their associated RSS ends (7–12). Vκ gene segments in Igκ are either in deletional (blue bars) or inversional (red bars) recombination orientation relative to Jκ gene segments (Fig. 4 A–D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A–D). As expected for the Jκ1 CE bait, WT A and B Abl libraries generated hundreds of thousands of junctions, displayed as highly orientation-biased joining to individual Vκ CEs, consistent with the V(D)J recombination mechanism (Fig. 4 A and B and SI Appendix, Table S3) (4, 7–12, 57). Most Vκ-to-Jκ V(D)J recombination-mediated joints were either direct or contained short insertions (Fig. 4E and SI Appendix, Fig. S9E), consistent with high-level TdT expression in these lines (SI Appendix, Fig. S9G), which obviates use of dominant MHs between Vκ and Jκ junctional sequences (58). We found little to no RAG DSB junctions in Lig4−/−A1, B1, and C Abl cell lines, and, correspondingly, these lines accumulated stable Jκ broken ends (Fig. 4 A–D and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 A–D, S10 A and B, S11 A and B, and Table S3). Lig4 complementation of Lig4−/−A1 and C Abl lines attenuated levels of Jκ broken ends and restored normal Vκ-to-Jκ joining with orientation bias and junction structures characteristic of normal V(D)J recombination (Fig. 4 A, B, and E and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 C–F, S10C, S11B, and Table S3).

Fig. 4.

RAG DSBs are robustly joined to each other in the absence of the Ku DSB sensor by a translocation-based A-EJ mechanism. (A) HTGTS-V(D)J-seq examining joining patterns of prey Vκ DSBs to the Jκ1 coding end comparing WT A, Ku70−/−A1, Lig4−/−A1, or Lig4−/−A1 +Lig4 Abl cells. Blue bars indicate junctions positioned in the (−) chromosomal orientation and red bars indicate junctions in the (+) chromosomal orientation; depending on the relative orientation of the coding segments in Igκ, junctions of either orientation will represent joins to either CEs or RSSs generated from RAG cleavage at a Vκ RSS. Joins falling within 200 bp of a CE or RSS are plotted (n = 3 for each clone; one-way ANOVA to compare the ratios CE/RSS with post hoc Tukey’s test, ***P < 0.001; see SI Appendix, Table S4). (B) Zoom-in of selected Vκ gene segments from A (N/A, not available). (C) HTGTS-V(D)J-seq using the same approach as A but comparing Lig4−/−A1, Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1, and Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1 +Ku70 Abl cells. (D) Zoom-in of selected Vκ gene segments from C. (E and F) Microhomology and insertion usage in junctions joining from Jκ1 to Vκ segments are plotted with indicated lengths (n = 3 for each clone, data represent mean ± SD).

In contrast to WT V(D)J recombination, we found significant levels of joining of the Jκ1 bait end to Vκ CEs and RSS ends in Ku70−/−A1 and B1 Abl cells, albeit at levels that were 5- to 10-fold lower than the levels of bona fide Vκ-to-Jκ junctions in WT A and B Abl lines (Fig. 4 A and B and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 A and B, S10B, S11A, and Table S3). Thus, the Jκ1 CE junctions in the Ku70−/−A1 and B1 Abl cells were not orientation biased toward Vκ CEs like with C-NHEJ, but rather, were balanced for both Vκ CEs and Vκ RSSs (Fig. 4 A–D and SI Appendix, Fig. S9 A–D and Table S3), thereby indicating that they were joined by an A-EJ-mediated repair mechanism as opposed to end-specific joining by bona fide V(D)J recombination. A significant fraction of the Vκ to Jκ A-EJ-mediated joins in Ku-deficient cells (∼30%) were potentially productive in that they fused the Vκ into the Jκ in frame (SI Appendix, Fig. S9H) with a major subset of those that maintain Vκ and Jκ sequences with little or no deletion/resection similar to those of functional joins in WT cells (Fig. 4B). Finally, deletion of Ku in Lig4−/−A1 and C Abl cells rescued Vκ-to-Jκ junctions to levels comparable to those found in the context of Ku70 deficiency alone (Fig. 4 C–F and SI Appendix, Figs. S9 C–F, S10D, S11C, and Table S3). Such A-EJ-mediated joins could be responsible for the leaky V(D)J recombination phenotype of Vκ-to-Jκ joining in Ku-deficient mice described previously (21).

Discussion

We report that DNA DSBs generated by three different classes of endonucleases: RAG, Cas9:gRNA, and ZFN in G1-arrested Abl cells accumulate as unjoined broken ends in the absence of the Lig4 core C-NHEJ factor. We further define the mechanism as suppression of A-EJ in these G1-arrested cells by Ku. This finding is notable as it greatly contrasts with relatively robust A-EJ of general or CSR-associated DSBs reported previously in the absence of Lig4 or its essential XRCC4 cofactor complex in various cycling contexts (28, 30, 37, 59). While A-EJ is often considered a single pathway, two pathways of A-EJ have been proposed to be capable of mediating CSR in cycling B cells. One pathway, which occurs in Lig4-deficient B cells, uses almost exclusively MH-mediated joins and potentially represents a variation of C-NHEJ that likely uses Lig1 (28, 30). The second pathway found in the absence of either Ku or Ku plus Lig4, substantially uses direct joins and represents a true A-EJ pathway, since it occurs in the absence of C-NHEJ recognition and joining components (28). The A-EJ pathway that operates in Ku-deficient G1-arrested Abl cells, generally matches well with the latter end-joining pathway and thus represents a bona fide A-EJ pathway. On the other hand, the C-NHEJ variant pathway that operates in CSR is essentially absent in G1-arrested Abl cells, consistent with very low-level Lig1 and Polθ expression in these and other G1-arrested cells (SI Appendix, Figs. S12 A–E and S13) (37, 60). Notably, however, joining of ZFN-generated DSBs in Lig4-deficient, G1-arrested Abl cells was substantially but not completely suppressed by Ku, with recovered joins mostly MH dependent, consistent with mediation by the variant C-NHEJ pathway using Lig3. There are various mechanisms by which ZFN-generated DSBs access this joining pathway at low level, for example, if ZFN-binding partially interferes with Ku binding, but resolution of the mechanism will require further investigation. Thus, Ku presence at the end appears to serve as a crucial access point for switching DSB repair pathways.

Our findings provide a molecular mechanism that could enforce the shepherding of RAG-initiated DSBs to repair by C-NHEJ, versus A-EJ, during V(D)J recombination (17, 61–63). Our findings also provide a cellular mechanism as to why Ku deficiency versus XRCC4/Lig4 deficiency differentially impacts developmental processes in vivo. With respect to lymphoid development, we have now mechanistically defined why low-level joining of RAG-initiated DSB joining occurs during V(D)J recombination in Ku70-deficient versus Lig4- or XRCC4-deficient mice (21, 25). In this context, the inefficient translocation-based joining of Vκ and Jκ gene segments that escape the RAG postsynaptic complex are fused to make V(D)J-like joints of which a significant proportion can serve as functional joins (7). In addition, we speculate that our findings may explain the differential impact of Ku deficiency versus Lig4 or XRCC4 deficiency on embryonic development. Thus, our findings support the hypothesis (15, 47) that absence of Ku allows A-EJ to rejoin a substantial fraction of DSBs in postmitotic neurons and thereby does not impact embryonic viability, whereas, the abrogation of end joining, mediated by the Ku complex, would lead to an intolerable DSB burden and embryonic lethality in the context of Lig4 or XRCC4 deficiency. This model also can explain why Ku deficiency rescues embryonic lethality of XRCC4/Lig4-deficient mice (45).

Methods

Generation of Cell Lines and Reagents.

The WT A Abl cell line was generated from a Lig4flox/flox Eµ-Bcl2 transgenic mouse as previously described (59). The WT B Abl cell line was generated from an Eµ-Bcl2 transgenic mouse. Lig4−/−A1 was generated by Cre deletion, using adeno-Cre recombinase, from WT A. Ku70−/−A1 was generated from WT A, and Lig4−/−Ku70−/−A1-1 was generated from Lig4−/−A1 using Cas9 (SI Appendix, Table S4). Lig4−/−B1 and Ku70−/−B1 Abl lines were generated from WT B. Lig4−/−C and Lig4−/−D (Eb-ZFN) (50) were gifts from Barry Sleckman, University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL; Lig4−/−Ku70−/−C1 was derived from Lig4−/−C; and Lig4−/−Ku70−/−D1 was derived from Lig4−/−D (SI Appendix, Table S4). All CRISPR/Cas9 generation and screening of knockout cell lines were performed as previously described (64). Abl cells were G1 arrested using STI-571 (3 µM) for 96 h (SI Appendix, Methods).

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Sample Preparation and HTGTS-JoinT-seq.

Designer nuclease bait experiments employed HTGTS-JoinT-seq. Junction-enriched libraries were generated as previously described for LAM-HTGTS (48) but with the removal of the bait DSB rejoining blocking step. Input genomic DNA for each junction library sample/replication was 12 μg and all sequences were aligned to the mm10 genome build. Libraries were sequenced by Illumina MisEq (250PE) or NextsEq (150PE) and primers specific to each are indicated (SI Appendix, Table S4). Pooled raw sequences were demultiplexed and adapter trimmed using TranslocPreprocess (48). Libraries were then normalized to the same number of raw reads within each experiment. Translocations were identified using TranslocWrapper (48) with additional modifications, followed by mapping rejoined bait ends using the R module, JoinT (SI Appendix, Methods). See SI Appendix for description of HTGTS-Rep-Rejoin.

HTGTS-V(D)J-seq and Hotspot Analysis.

HTGTS-V(D)J-seq (11) was performed for the Jκ1 coding end bait as similarly described (7, 8) using the mm10 genome build, and only junctions within 200 bp of bona fide Vκ RSSs, with or without 150 bp of bona fide Jκ RSSs, were described. For all NGS experiments, MACS2-based algorithm was used with a false discovery rate (FDR)-adjusted P-value enrichment threshold of 10-10 as described (20). Hotspots were called if enriched sites were significant in all replicate libraries.

Southern Analysis.

Southern blots were performed with 20 µg of input DNA of the given condition and digested with either HindIII (to detect unrepaired Cas9 DSB ends at c-Myc or ZFN DSB ends at Eb) or double digest with EcoRI and NcoI (to detect unrepaired Jκ DSB ends). Southern probes used and additional methods are indicated (SI Appendix, Methods and Table S4).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the F.W.A. and R.L.F. laboratories for stimulating discussions and feedback. We thank Zhaoqing Ba, James Haber, and Andre Nussenzweig for helpful comments. We thank Barry Sleckman (University of Alabama) for the Lig4−/−C and Eb-ZFN expressing Lig4−/−D Abl lines. This work was supported by NIH grant AI020047 (to F.W.A.), NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award fellowships CA189740 (to V.K.) and AI117920 (to S.G.L.), a Cancer Research Institute training grant (to C.B.), and a Radiation Research Foundation Career Development Award (to R.L.F.). F.W.A. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. R.L.F. is a V Scholar for the V Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2103630118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Raw and processed sequencing data are available through GEO (GSE162453). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. Previously published data were used for this work [GSE151910 (12) and GSE142781 (11)].

References

- 1.Chang H. H. Y., Pannunzio N. R., Adachi N., Lieber M. R., Non-homologous DNA end joining and alternative pathways to double-strand break repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 495–506 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scully R., Panday A., Elango R., Willis N. A., DNA double-strand break repair-pathway choice in somatic mammalian cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 698–714 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teng G., Schatz D. G., Regulation and evolution of the RAG recombinase. Adv. Immunol. 128, 1–39 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin S. G., Ba Z., Alt F. W., Zhang Y., RAG chromatin scanning during V(D)J recombination and chromatin loop extrusion are related processes. Adv. Immunol. 139, 93–135 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim M. S., Lapkouski M., Yang W., Gellert M., Crystal structure of the V(D)J recombinase RAG1-RAG2. Nature 518, 507–511 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ru H., et al., Molecular mechanism of V(D)J recombination from synaptic RAG1-RAG2 complex structures. Cell 163, 1138–1152 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu J., et al., Chromosomal loop domains direct the recombination of antigen receptor genes. Cell 163, 947–959 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao L., et al., Orientation-specific RAG activity in chromosomal loop domains contributes to Tcrd V(D)J recombination during T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 213, 1921–1936 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jain S., Ba Z., Zhang Y., Dai H. Q., Alt F. W., CTCF-binding elements mediate accessibility of RAG substrates during chromatin scanning. Cell 174, 102–116.e14 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Y., et al., The fundamental role of chromatin loop extrusion in physiological V(D)J recombination. Nature 573, 600–604 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ba Z., et al., CTCF orchestrates long-range cohesin-driven V(D)J recombinational scanning. Nature 586, 305–310 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dai H. Q., et al., Loop extrusion mediates physiological Igh locus contraction for RAG scanning. Nature 590, 338–343 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill L., et al., Wapl repression by Pax5 promotes V gene recombination by Igh loop extrusion. Nature 584, 142–147 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schatz D. G., Swanson P. C., V(D)J recombination: Mechanisms of initiation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45, 167–202 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alt F. W., Zhang Y., Meng F. L., Guo C., Schwer B., Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell 152, 417–429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar V., Alt F. W., “NHEJ and other repair factors in V(D)J recombination” in Encyclopedia of Immunobiology, Ratcliffe M. J. H., Ed. (Elsevier, 2016), pp. 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corneo B., et al., Rag mutations reveal robust alternative end joining. Nature 449, 483–486 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee G. S., Neiditch M. B., Salus S. S., Roth D. B., RAG proteins shepherd double-strand breaks to a specific pathway, suppressing error-prone repair, but RAG nicking initiates homologous recombination. Cell 117, 171–184 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiarle R., et al., Genome-wide translocation sequencing reveals mechanisms of chromosome breaks and rearrangements in B cells. Cell 147, 107–119 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frock R. L., et al., Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 179–186 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu Y., et al., Growth retardation and leaky SCID phenotype of Ku70-deficient mice. Immunity 7, 653–665 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frank K. M., et al., DNA ligase IV deficiency in mice leads to defective neurogenesis and embryonic lethality via the p53 pathway. Mol. Cell 5, 993–1002 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gao Y., et al., Interplay of p53 and DNA-repair protein XRCC4 in tumorigenesis, genomic stability and development. Nature 404, 897–900 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao Y., et al., A critical role for DNA end-joining proteins in both lymphogenesis and neurogenesis. Cell 95, 891–902 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Y., et al., Defective embryonic neurogenesis in Ku-deficient but not DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 2668–2673 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan C. T., et al., IgH class switching and translocations use a robust non-classical end-joining pathway. Nature 449, 478–482 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu C., et al., Unrepaired DNA breaks in p53-deficient cells lead to oncogenic gene amplification subsequent to translocations. Cell 109, 811–821 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boboila C., et al., Alternative end-joining catalyzes class switch recombination in the absence of both Ku70 and DNA ligase 4. J. Exp. Med. 207, 417–427 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guirouilh-Barbat J., Rass E., Plo I., Bertrand P., Lopez B. S., Defects in XRCC4 and KU80 differentially affect the joining of distal nonhomologous ends. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 20902–20907 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boboila C., et al., Robust chromosomal DNA repair via alternative end-joining in the absence of X-ray repair cross-complementing protein 1 (XRCC1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2473–2478 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sfeir A., de Lange T., Removal of shelterin reveals the telomere end-protection problem. Science 336, 593–597 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wei P. C., et al., Long neural genes harbor recurrent DNA break clusters in neural stem/progenitor cells. Cell 164, 644–655 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Audebert M., Salles B., Calsou P., Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 and XRCC1/DNA ligase III in an alternative route for DNA double-strand breaks rejoining. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55117–55126 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ceccaldi R., et al., Homologous-recombination-deficient tumours are dependent on Polθ-mediated repair. Nature 518, 258–262 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mateos-Gomez P. A., et al., Mammalian polymerase θ promotes alternative NHEJ and suppresses recombination. Nature 518, 254–257 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zan H., et al., Rad52 competes with Ku70/Ku86 for binding to S-region DSB ends to modulate antibody class-switch DNA recombination. Nat. Commun. 8, 14244 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu W., et al., Repair of G1 induced DNA double-strand breaks in S-G2/M by alternative NHEJ. Nat. Commun. 11, 5239 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansour W. Y., Borgmann K., Petersen C., Dikomey E., Dahm-Daphi J., The absence of Ku but not defects in classical non-homologous end-joining is required to trigger PARP1-dependent end-joining. DNA Repair (Amst.) 12, 1134–1142 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Truong L. N., et al., Microhomology-mediated End Joining and Homologous Recombination share the initial end resection step to repair DNA double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 7720–7725 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soni A., et al., Requirement for Parp-1 and DNA ligases 1 or 3 but not of Xrcc1 in chromosomal translocation formation by backup end joining. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 6380–6392 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shamanna R. A., et al., WRN regulates pathway choice between classical and alternative non-homologous end joining. Nat. Commun. 7, 13785 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bakr A., et al., Impaired 53BP1/RIF1 DSB mediated end-protection stimulates CtIP-dependent end resection and switches the repair to PARP1-dependent end joining in G1. Oncotarget 7, 57679–57693 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kang Y. J., Yan C. T., Regulation of DNA repair in the absence of classical non-homologous end joining. DNA Repair (Amst.) 68, 34–40 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nussenzweig A., et al., Requirement for Ku80 in growth and immunoglobulin V(D)J recombination. Nature 382, 551–555 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karanjawala Z. E., et al., The embryonic lethality in DNA ligase IV-deficient mice is rescued by deletion of Ku: Implications for unifying the heterogeneous phenotypes of NHEJ mutants. DNA Repair (Amst.) 1, 1017–1026 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adachi N., Ishino T., Ishii Y., Takeda S., Koyama H., DNA ligase IV-deficient cells are more resistant to ionizing radiation in the absence of Ku70: Implications for DNA double-strand break repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12109–12113 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haber J. E., Alternative endings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 405–406 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hu J., et al., Detecting DNA double-stranded breaks in mammalian genomes by linear amplification-mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 11, 853–871 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bredemeyer A. L., et al., ATM stabilizes DNA double-strand-break complexes during V(D)J recombination. Nature 442, 466–470 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee B. S., et al., Functional intersection of ATM and DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit in coding end joining during V(D)J recombination. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 3568–3579 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pryor J. M., et al., Essential role for polymerase specialization in cellular nonhomologous end joining. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E4537–E4545 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stinson B. M., Moreno A. T., Walter J. C., Loparo J. J., A mechanism to minimize errors during non-homologous end joining. Mol. Cell 77, 1080–1091.e8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gouge J., et al., Structural basis for a novel mechanism of DNA bridging and alignment in eukaryotic DSB DNA repair. EMBO J. 34, 1126–1142 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemos B. R., et al., CRISPR/Cas9 cleavages in budding yeast reveal templated insertions and strand-specific insertion/deletion profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E2040–E2047 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Frank K. M., et al., Late embryonic lethality and impaired V(D)J recombination in mice lacking DNA ligase IV. Nature 396, 173–177 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith J., et al., Requirements for double-strand cleavage by chimeric restriction enzymes with zinc finger DNA-recognition domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 3361–3369 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen H., et al., BCR selection and affinity maturation in Peyer’s patch germinal centres. Nature 582, 421–425 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Komori T., Okada A., Stewart V., Alt F. W., Lack of N regions in antigen receptor variable region genes of TdT-deficient lymphocytes. Science 261, 1171–1175 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boboila C., et al., Alternative end-joining catalyzes robust IgH locus deletions and translocations in the combined absence of ligase 4 and Ku70. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3034–3039 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Akbari M., et al., Extracts of proliferating and non-proliferating human cells display different base excision pathways and repair fidelity. DNA Repair (Amst.) 8, 834–843 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gigi V., et al., RAG2 mutants alter DSB repair pathway choice in vivo and illuminate the nature of ‘alternative NHEJ’. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 6352–6364 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lescale C., et al., RAG2 and XLF/Cernunnos interplay reveals a novel role for the RAG complex in DNA repair. Nat. Commun. 7, 10529 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Deriano L., et al., The RAG2 C terminus suppresses genomic instability and lymphomagenesis. Nature 471, 119–123 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kumar V., Alt F. W., Frock R. L., PAXX and XLF DNA repair factors are functionally redundant in joining DNA breaks in a G1-arrested progenitor B-cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 10619–10624 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw and processed sequencing data are available through GEO (GSE162453). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information. Previously published data were used for this work [GSE151910 (12) and GSE142781 (11)].