Significance

This work explores carbon aerogels with a three-dimensional interconnected nanofiber network and rationally designed hierarchical porous structures, which endow the supercapacitors (SCs) with both high energy density and long-term stability, with the goal of practical application. The as-constructed SCs have a high specific capacitance of 297 F ⋅ g–1 at 1 A ⋅ g–1 and remarkable energy density of 14.83 Wh ⋅ kg−1 at 0.60 kW ⋅ kg−1, both of which are much higher than those of most carbon-based SCs. Significantly, they have an extremely high stability, with capacitance retention of 100% over 65,000 cycles, the best among carbon-based SCs.

Keywords: supercapacitors, carbon aerogels, specific capacitance, energy density, cycling stability

Abstract

In terms of ideal future energy storage systems, besides the always-pursued energy/power characteristics, long-term stability is crucial for their practical application. Here, we report a facile and sustainable strategy for the scalable fabrication of carbon aerogels with three-dimensional interconnected nanofiber networks and rationally designed hierarchical porous structures, which are based on the carbonization of bacterial cellulose assisted by the soft template of Zn-1,3,5-benzenetricarboxylic acid. As binder-free electrodes, they deliver a fundamentally enhanced specific capacitance of 352 F ⋅ g–1 at 1 A ⋅ g–1 in a wide potential window (1.2 V, 6 M KOH) in comparison with those of bacterial cellulose–derived carbons (178 F ⋅ g–1) and most activated carbons (usually lower than 250 F ⋅ g–1). The as-assembled supercapacitors exhibit an ultrahigh capacitance of 297 F ⋅ g−1 at 1 A ⋅ g−1, remarkable energy density (14.83 Wh ⋅ kg−1 at 0.60 kW ⋅ kg−1), and extremely high stability, with 100% capacitance retention for up to 65,000 cycles at 6 A ⋅ g−1, representing their superior energy storage performance when compared with that of state-of-the-art supercapacitors of commercial activated carbons and biomass-derived analogs.

With the rapid development of sustainable and renewable energy resources, supercapacitors (SCs) have been recognized as an integral part of future power systems because of their high-power characteristics, fast charge–discharge capacity, long lifespan, and high safety and reliability (1–3). Carbon nanomaterials, as an excellent candidate for electrical double-layer capacitive (EDLC) electrodes, have been intensively investigated [e.g., activated carbons (4), porous carbons (5), carbide-derived carbons (6), carbon nanofibers (7), carbon nanotubes (8), and graphene (9, 10)], owing to their favorable structural features, such as high chemical stability, high porosity, large specific surface area (SSA), and high electrical conductivity (11, 12). Among the carbon nanomaterials, activated carbons still hold a predominant share in commercial markets. Nevertheless, currently, the popular SCs based on activated carbons still have unsatisfactory energy density (<10 Wh ⋅ kg−1) and stability. For practical applications, it is highly desired to explore carbon materials with enhanced specific capacitance without sacrificing the power performance and cycling stability.

It is widely accepted that hierarchical carbon materials, with expected appropriate distribution of interconnected macro/meso/micropores and high SSA, can facilitate both fast mass diffusion and optimal site exposure, thus allowing large capacitances under high charge–discharge conditions (13). To date, to realize the desirable porous structures, the hard templates (e.g., MgO, ZnO, and SiO2) (14) and physical (e.g., CO2 and steam) (15) and chemical activations (e.g., H3PO4, H2SO4, ZnCl2, and KOH) (16) have been generally required. Although they are effective in creating abundant pores, there are some intrinsic drawbacks with high energy/time consumption, a complicated process, low yield, and environmental hazard. Alternatively, the soft templates provide a more facile, more efficient, and lower-pollution strategy for the synthesis of porous carbons with controllable pore structures (17–20). Therefore, the applied surfactant is considered the key point, which should not only be converted to carbons completely but also possess large diffusion limitation and low electric conductivity (21–24). Regardless of the fact that tremendous efforts have been made to improve the capacitance of carbon materials, it remains a great challenge to exploit porous carbons with both high specific capacitance and long cycle life.

In the present work, a facile and sustainable approach is developed for scalable fabrication of hierarchical porous carbon aerogels with a three-dimensional (3D), interconnected nanofiber network based on the carbonization of bacterial cellulose (BC) assisted by the soft template of Zn-1,3,5-Benzenetricarboxylic acid (Zn-BTC). Here, 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) is preferred to oxidize BC, which provides uniformly dispersed cellulose nanofibers (TOCN) with high-density carboxy groups (25). Accordingly, the resultant TOCN could have strong a affinity with Zn2+ ions in Zn-BTC on BC nanofibers, followed by gasification/evaporation etching over the carbonization process for the creation of rich defects and abundant micro- and mesopores within the BC-derived nanofibers. The as-fabricated carbon aerogels possess expected hierarchical porous structures with substantially increased micropores, large SSA, and appropriate defects without any introduced metal/nonmetal heteroatoms. As a proof of concept, they deliver an enhanced specific capacitance (352 F ⋅ g−1 at 1 A ⋅ g−1, 6 M KOH) compared to TOCN-derived carbon (178 F ⋅ g−1) and most reported activated carbons (usually lower than 250 F ⋅ g−1). Moreover, the as-constructed symmetric SCs have a high specific capacitance up to ∼297 F ⋅ g−1 at 1 A ⋅ g−1 and remarkable energy and power densities of 14.83 Wh ⋅ kg−1 at 0.60 kW ⋅ kg−1 and 9.065 Wh ⋅ kg−1 at 24.35 kW ⋅ kg−1, respectively. Interestingly, they have an extremely robust stability, with a capacitance retention of 100% for up to 65,000 cycles, demonstrating a superior overall energy storage performance that is highly promising for practical applications in advanced energy storage devices.

Results and Discussion

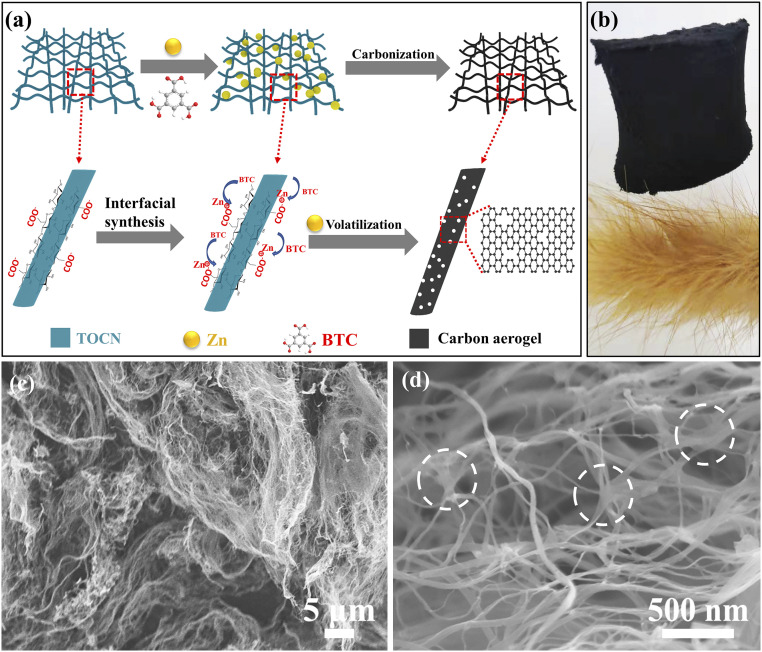

The preparation of the Zn-BTC@TOCN–derived carbon aerogel (referred to as sample ZBTC0.8-900) is schematically illustrated in Fig. 1A. It starts with the chemical functionalization of BC by TEMPO oxidation for obtaining an even monodispersion of BC nanofibers in water, in which the glucosyl residues in cellulose chains can be transformed into sodium glucuronosyl residues (i.e., carboxyl groups) (26). The existing abundant carboxylates could endow stronger affinities for Zn2+ cations (27) than Na+ in TOCN, leading to the formation of a stable Zn2+−RCOO− complex. The subsequent addition of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O and BTC initiates the rapid construction of Zn-BTC on Zn2+−RCOO− sites, causing the homogeneous distribution of Zn-BTC particles within TOCN networks (referred to as sample Zn-BTC@TOCN) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In the current case, it seems that the Zn-BTC assembly (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and the molecule unit of Zn-BTC in SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (28) would happen in water under ambient conditions rather than the common conditions assisted by organic solvents [e.g., ethanol (29), dimethyl sulfoxide (30), dimethyl formamide (31), oil bath (32), microwave (33), or solvothermal conditions (34)], suggesting a facile and sustainable process. Afterward, heat treatment at 900 °C for 2 h causes the transformation of Zn-BTC@TOCN into the scalable fabrication of carbon aerogels, as shown in Fig. 1B. The obtained aerogels exhibit an ultralow density of ∼1.5 mg ⋅ cm−3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), which is much lower than that of the TOCN-derived counterpart (i.e., sample TC-900 with a typical density of 2.5 mg ⋅ cm−3) and comparable to that of air under ambient conditions (i.e., 1.2 mg ⋅ cm−3), implying the existence of rich porosity with high SSA of the target product.

Fig. 1.

(A) The schematic illustration on fabricating carbon aerogels with 3D interconnected networks and hierarchical porous structures. (B) The recorded digital photograph showing the scalable fabrication of the product. (C and D) Typical SEM images of sample ZBTC0.8-900 under different magnifications. The white circles in D show the 3D interconnected network within the carbon aerogels.

Fig. 1 C and D show the typical field-emission scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of sample ZBTC0.8-900 under different magnifications, presenting its highly dispersed fiber-like structure with diameters ranging from 10 to 50 nm and abundant welded joints for building a 3D interconnected network, which accounts for its high compressibility with nearly 100% recovery, regardless of being subjected to 90% compression under 3.5 kPa (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). In comparison, sample TC-900, as prepared without the regulation of Zn-BTC, exhibits a similar morphology but without obvious joint points among the carbon nanofibers (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). The obtained ZBTC0.8-900 aerogel has abundant welded joints among the nanofibers, which allow for the formation of a unique, spiderweb-like 3D network structure with enhanced interconnection, thus making the structure more robust and stable. However, the Zn-BTC–derived carbons (i.e., sample ZBC-900) have a disordered structure with a sheet and particle arrangement (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 C and D). Notably, the Zn-BTC–derived carbon particles cannot be observed on sample ZBTC0.8-900, implying that the introduced Zn-BTC should mainly act as the soft template for the creation of pores and defects rather than the carbon precursor. SI Appendix, Fig. S7 C and D provide the typical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of sample TC-900, showing its turbostratic graphite-like carbon structure. SI Appendix, Fig. S7 E and F confirm the existence of numerous Zn nanoparticles (3 to ∼10 nm in diameter) within sample ZBC-900. SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B are the representative TEM images of sample ZBTC0.8-900, revealing the disordered carbon structure accompanied with the formation of micropores. The curve edges imply the ultrathin nature of carbon nanofibers, while the discontinuous fringes reveal the existence of plentiful defects in sample ZBTC0.8-900, mainly caused by the evaporation of Zn ions (35–37). SI Appendix, Fig. S8 shows the improved KOH wettability of sample ZBTC0.8-900 as compared to sample TC-900, demonstrating its fundamentally enhanced ion transport (38).

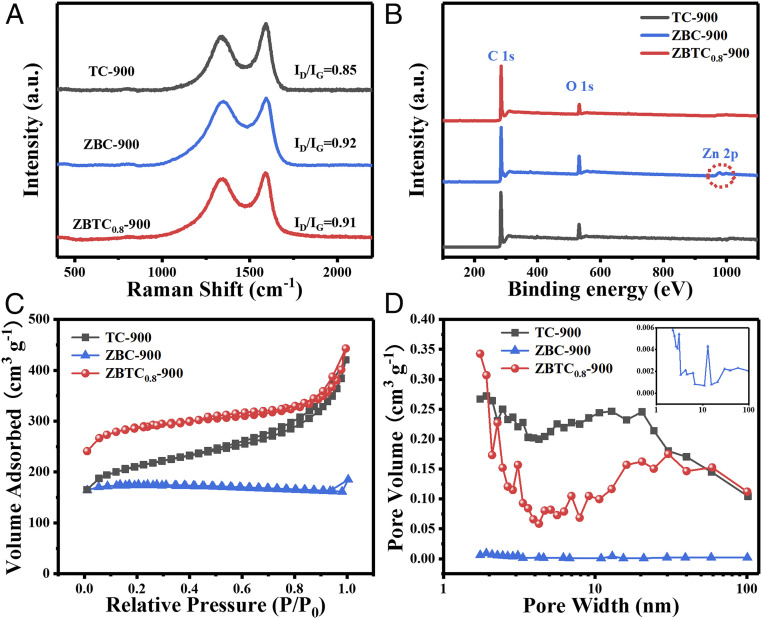

Fig. 2A is the Raman spectra of sample TC-900, ZBC-900, and ZBTC0.8-900. They have two peaks at 1,343 and 1,580 cm−1, representing the defects (sp3-C, D band) (39) and graphitization (sp2-C, G band) (40), respectively. The intensity ratios (ID/IG) for sample TC-900, ZBC-900, and ZBTC0.8-900 are ca. ∼0.85, ∼0.92, and ∼0.91, respectively, revealing the worst graphitization in sample ZBC-900. The incorporation of Zn in precursors increases the porosity and exposes edge defects in resultant carbon materials, which can be validated by the slightly higher ID/IG value of ZBTC0.8-900 than TC-900. Accordingly, the evaporation effect of Zn-BTC enriches the active sites and allows for the intercalation of small ions, which are favorable for charge storage performance. Fig. 2B provides the typical X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey spectra, indicating the exclusive existence of carbon and oxygen in sample TC-900 and ZBTC0.8-900 with a tiny amount of Zn (∼0.12 at%) detected in sample ZBC-900. However, no Zn signals are detected in sample ZBTC0.8-900 according to the analyses of XPS (Fig. 2B), X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectra (EDX) (SI Appendix, Table S1). The Zn species have been detected within sample ZBC-900, which are identified as metallic Zn0 state (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). For sample ZBTC0.8-900, the high-resolution C 1 s spectrum in SI Appendix, Fig. S11 can be deconvoluted into four peaks, that is, the dominant sp2 C=C (284.5 eV) species accompanied with sp3-C (285.2 eV), C–O (286.8 eV), and O–C=O (288.9 eV) (41, 42). Among these, the strong sp3-C signal responds to a large amount of C–C and C–H bonding in graphite matrix (43), demonstrating the existence of rich defects. Based on the calculated ratio of sp3-C to total C, it confirms that more moderate defects have been created in sample ZBTC0.8-900 (32.3%) compared to those of sample ZBC-900 (44.3%) and TC-900 (25.8%), in agreement with the observations of TEM and Raman.

Fig. 2.

(A) Representative Raman spectra, (B) XPS survey spectra, (C) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms, and (D) pore diameter distributions of sample TC-900, ZBC-900, and ZBTC0.8-900, respectively.

Fig. 2C provides the N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of sample TC-900, ZBC-900, and ZBTC0.8-900 with typical type-IV adsorption, in which the observed hysteresis represents their mesoporous characteristic (44). Correspondingly, the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) SSAs of sample TC-900 and ZBTC0.8-900 are ca. 674 and 893 m2 ⋅ g−1, respectively, much higher than that of sample ZBC-900 (123 m2 ⋅ g−1). The largest SSA in sample ZBTC0.8-900 suggests it has the optimal electrode/electrolyte interface for improved electrical charge storage. What is more, the SSA values deduced from the micropore portion are ca. 379 and 660 m2 ⋅ g−1 for sample TC-900 and ZBTC0.8-900, respectively, verifying a much higher ratio of micropores to mesopores in sample ZBTC0.8-900. Thus, the effect of introduced Zn-BTC is inferred to mainly cause the formation of micropores within TOCN-derived carbon networks. This can be further confirmed from the pore size distribution in Fig. 2D, in which sample ZBTC0.8-900 presents abundant tiny pores at 1 to 4 nm as compared to sample TC-900. Moreover, sample ZBTC0.8-900 has larger mesopores centered at ∼30 nm in size, while those in sample TC-900 are centered at ∼18 nm. Additionally, sample ZBTC0.8-900 possesses a smaller average pore volume of 0.30 cm3 ⋅ g–1 than sample TC-900 at 0.42 cm3 ⋅ g–1, reflecting more micropores generated. Briefly, it can be confirmed that the introduced soft template of Zn-BTC can significantly enhance the SSA by creating micropores and enlarging mesopores for as-fabricated carbon aerogels with hierarchical porous structures to favor the charge storage, as the micropores facilitate the charge accumulation and the desired mesopores accelerate the ion diffusion (45).

To disclose the effect of carbonization temperatures on the growth of products, the temperatures are fixed in the range of 800 to 1,000 °C with an interval of 100 °C, and the resultant samples are referred to as sample ZBTC0.8-T (T = 800, 900, and 1,000 °C), as shown in SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13. ZnO particles are clearly observed in sample ZBTC0.8-800 (SI Appendix, Fig. S13 and Table S1), implying the incomplete removal of ZnO at the relatively lower temperature of 800 °C (46). However, once the temperature is higher than 900 °C, as for sample ZBTC0.8-1000, it shows a nanofiber network similar to that of ZBTC0.8-900 without ZnO/Zn nanoparticles (SI Appendix, Fig. S12 C and D and Table S1). Their typical XRD patterns (SI Appendix, Fig. S14A) exhibit two similar broad peaks, indicating the formation of amorphous carbons. Sample ZBTC0.8-800 shows several weak diffraction peaks of ZnO (47), further reflecting the incomplete evaporation of Zn at a temperature lower than 900 °C. Furthermore, the Raman spectra of these samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S14B) show that the ID/IG ratios are reduced from 0.93 to 0.88 with an increase in temperature from 800 to 1,000 °C, indicating improved graphitization upon raising the temperature. Based on N2 adsorption–desorption tests, all three samples are hierarchically porous with the coexistence of micropores, mesopores, and macropores. Therefore, sample ZBTC0.8-900 has the highest SSA value (893 m2 ⋅ g−1), largest pore volume (0.30 cm3 ⋅ g–1), and smallest average pore size (6.71 nm) compared to those of sample ZBTC0.8-800 (572 m2 ⋅ g−1, 0.15 cm3 ⋅ g–1, and 10.4 nm) and ZBTC0.8-1000 (676 m2 ⋅ g−1, 0.14 cm3 ⋅ g–1, and 8.88 nm) (SI Appendix, Fig. S14 C and D), implying it has the best electrochemical interface behaviors.

The effect of Zn-BTC loading amounts within TOCN networks is also investigated, and the obtained carbon aerogels are denoted as sample ZBTCx-900, where x indicates the ratios of Zn-BTC to TOCN in source materials (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mmol Zn2+ with BC kept at 14 mg). It demonstrates that the defect degrees of these five samples increases successively, with ID/IG values reduced from 0.87 to 0.92 by increasing the Zn-BTC loading amounts (SI Appendix, Fig. S15A). Their SSA values keep increasing before x = 0.8, reaching the maximum 893 m2 ⋅ g−1 for sample ZBTC0.8-900 and then decreasing to 605 m2 ⋅ g−1 for sample ZBTC1.0-900 (SI Appendix, Fig. S15B). Additionally, it shows that all samples of ZBTCx-900 have more micropores than those of TC-900 (SI Appendix, Fig. S15C). These results underscore the critical role of the soft template of Zn-BTC in the rationally designed creation of defects and micro/mesopores within the carbon matrix under the optimized temperature and source material ratio, making sample ZBTC0.8-900 an advanced metal-free carbon material with a favorable interconnected nanofiber network, ultralow density, excellent flexibility, rich defects, large SSA, and hierarchical porous characteristics.

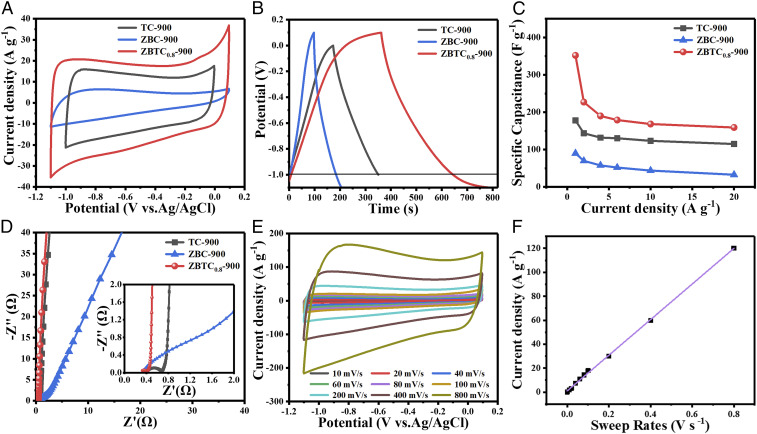

Fig. 3A shows the typical cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves of the electrodes based on sample ZBTC0.8-900, TC-900, and ZBC-900 at a scan rate of 100 mV ⋅ s–1. It seems that the CV profiles of ZBTC0.8-900 and TC-900 electrodes exhibit a similar rectangular-like shape, whereas that of ZBC-900 is more triangular, indicating ideal capacitive behavior of the former two samples. The electrode based on sample ZBTC0.8-900 has a wider potential window (1.2 V) than that of TC-900 (1.0 V), mainly attributed to the existing micropores providing reduced ion mobility among the electrolyte/electrode surface (48). Moreover, the ZBTC0.8-900 electrode has a larger CV-enclosed area than TC-900 and ZBC-900, indicating it has the highest specific capacitance. This can be further confirmed from their galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) curves at 1 A ⋅ g–1, as displayed in Fig. 3B. The ZBTC0.8-900 electrode has a specific capacitance of 352 F ⋅ g–1 (superior to those of sample TC-900 [178 F ⋅ g–1] and ZBC-900 [90 F ⋅ g–1]), which stands among the best metal–organic frameworks (MOF)/biomass-derived carbons ever reported (SI Appendix, Table S2). This should be mainly ascribed to the desired large SSA and hierarchical porous structure of sample ZBTC0.8-900 with abundant micro- and mesopores as well as appropriate defects (summary found in SI Appendix, Table S3), which offer large electrode/electrolyte interfaces and fast electrolyte ion diffusion for enhanced charge capacitance ability (49). Moreover, even at a high current density of 20 A ⋅ g–1, the ZBTC0.8-900 electrode still has a specific capacitance up to 159 F ⋅ g–1, while the TC-900 and ZBC-900 electrodes keep lower capacitances of 115 and 33 F ⋅ g–1, respectively (Fig. 3C). Fig. 3D provides the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analyses of these three electrodes during the charge storage process, verifying the minimum semicircle radius of ZBTC0.8-900 electrode in a high-frequency region with the smallest charge transfer resistance (Rct) of 0.23 Ω (versus 0.66 and 2.39 Ω for sample TC-900 and ZBC-900, respectively). Additionally, the equivalent series resistance (Rs) derived from the intercept on the imaginary axis is 0.31 Ω for the ZBTC0.8-900 electrode, smaller than those of sample TC-900 (0.34 Ω) and ZBC-900 (0.35 Ω). The scan-rate–dependent voltametric currents are further investigated to identify whether the electrochemical process comes from a surface mechanism or diffusion-controlled process. Based on the CV plots at the scan rates ranging from 10 to 800 mV ⋅ s−1 (Fig. 3E), the current density at −0.5 V versus Ag/AgCl shows an ideal linearity, even at the highest sweep rate of 800 mV ⋅ s−1 (Fig. 3F), indicating that the surface capacitive behavior plays the decisive role (50). Together with the comparison of the electrochemical performances of ZBTC0.8-T (T = 800, 900, and 1,000 °C) (SI Appendix, Fig. S16 and Table S4) and ZBTCx-900 (x = 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0) (SI Appendix, Fig. S17 and Table S3), it is confirmed that the ZBTC0.8-900 electrode delivers the lowest charge/mass transfer resistance and smallest internal resistance with the best EDLC capacitance behaviors.

Fig. 3.

Electrochemical performance of the samples in a three-electrode system. (A) CV plots at 100 mV ⋅ s–1. (B) GCD curves under 1 A ⋅ g–1. (C) Specific capacitances at different current densities. (D) Nyquist plots of sample TC-900, ZBC-900, and ZBTC0.8-900. (E) CV plots of sample ZBTC0.8-900 at different scan rates. (F) The dependence of current densities at −0.5 V on the scan rates.

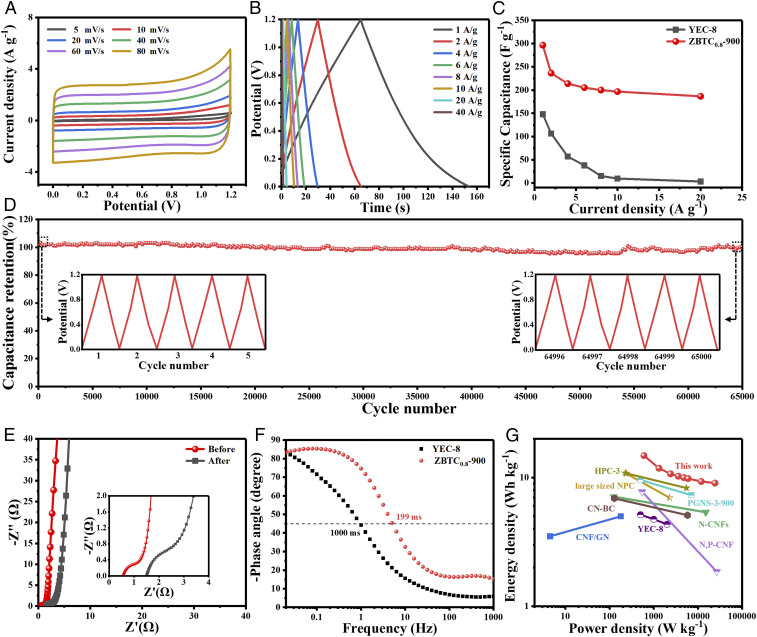

The symmetric SCs in 6 M KOH are then assembled based on sample ZBTC0.8-900 to evaluate the potential for practical application. All the recorded CV curves swept from 5 to 80 mV ⋅ s–1 (Fig. 4A) show a wide potential window of 1.2 V, with similar near-rectangular shapes and rapid current responses upon voltage reversal, suggesting the excellent capacitive behavior. All the measured GCD curves at different current densities (Fig. 4B) are nearly linear and symmetrical over the current range from 1 to 40 A ⋅ g–1, further showing its outstanding capacitive reversibility. Fig. 4C shows the calculated specific capacitances, presenting its specific capacitance of 297 F ⋅ g–1 at a current density of 1 A ⋅ g–1, which is much higher than any other reported SCs assembled by commercial activated carbon (YEC-8, 148 F ⋅ g–1) (SI Appendix, Fig. S18 A and B) or other biomass-derived carbon materials (SI Appendix, Table S5). With the increase of current density up to 20 A ⋅ g–1, the device still maintains a specific capacitance of 187 F ⋅ g–1, which is even higher than that of YEC-8 at 1 A ⋅ g–1 and 20 A ⋅ g–1 (3.2 F ⋅ g–1). In addition, it held 62.69% of original capacitance as the current density increased from 1 to 20 A ⋅ g–1, indicating the outstanding rate capability of current SCs. It is noteworthy that just small internal resistance (IR) drops can be observed in the GCD curves, even at a high current density of 40 A ⋅ g–1 (<15 mV), revealing the small internal resistances within the SCs. More interestingly, the as-constructed SCs exhibit an extremely high stability, with a capacitance retention of 100% for up to 65,000 GCD cycles at 6 A ⋅ g–1 (Fig. 4D), which is superior to those of most carbon-based SCs (SI Appendix, Table S6) as well as the assembled SCs based on YEC-8 (94.6%, SI Appendix, Fig. S18C). Furthermore, the Nyquist plots shown in Fig. 4E show that the excellent mass transport ability can be retained well after 65,000 cycles, regardless of a slight increase of intrinsic ohmic and charge transfer resistances. Fig. 4F provides the Bode plots of the electrodes based on YEC-8 and sample ZBTC0.8-900. The ZBTC0.8-900 electrode has a much shorter time constant of ∼199 ms than YEC-8 (∼1,000 ms), indicating its significantly improved electron transfer and capacitive behavior. Moreover, the SCs based on ZBTC0.8-900 electrode deliver an encouraging energy density of 14.83 Wh ⋅ kg–1 at a specific power of 0.6 kW ⋅ kg–1, which can maintain a high value of 9.07 Wh ⋅ kg–1 upon a much higher power density of 24.35 kW ⋅ kg–1. The Ragone plot shown in Fig. 4G compares the performances of the symmetric SCs based on sample ZBTC0.8-900, YEC-8, high-performance carbon materials (often less than 10 Wh ⋅ kg–1), and metal oxides typically reported (51–57), confirming the much better energy/power characteristics of the present devices.

Fig. 4.

Electrochemical performance of ZBTC0.8-900 electrode in a symmetrical two-electrode system. (A) CV plots at different scan rates. (B) GCD curves under different current densities. (C) Specific capacitances of the electrodes based on commercial YEC-8 activated carbon and sample ZBTC0.8-900 at different current densities. (D) Cycling stability at a density of 6 A ⋅ g–1 for 65,000 cycles. The right and left insets show the GCD curves at the first and last five cycles, respectively. (E) Nyquist plots before and after 65,000 cycles. (F) Impedance phase angle versus frequency of the electrodes based on YEC-8 and sample ZBTC0.8-900 electrode. (G) Ragone plots of SCs based on sample ZBTC0.8-900 and typical carbon materials.

Conclusions

In summary, we report the exploration of scalable fabrication of carbon aerogels by a facile and sustainable strategy, which is based on carbonization of TOCN assisted by the soft template of Zn-BTC. The as-fabricated carbon aerogels with 3D interconnected nanofiber networks possess a rationally designed hierarchical porous structure with the coexistence of meso- and micropores. They have excellent mechanical strength, substantially increased micropores, large SSA, and appropriate defects, without any metal and nonmetal heteroatoms. The as-constructed electrodes exhibit a high specific capacitance of 352 F ⋅ g−1 in 6 M KOH, and the as-assembled symmetrical SCs deliver an outstanding energy density of 14.83 Wh ⋅ kg–1 at a power density of 0.60 kW ⋅ kg–1. Moreover, they have an extremely high cycling stability, with a capacitance retention of 100% for up to 65,000 cycles at a large charge/discharge current of 6 A ⋅ g–1, demonstrating their overall superior capacitive behavior compared to the state-of-the-art SCs of commercial activated carbons and biomass-derived carbons. The current work might provide some insight on the exploration of carbon materials for advanced energy storage with both high energy/power characteristics and long-term stability for practical application.

Materials and Methods

Chemical Reagents and Materials.

The raw materials of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, 1,3,5-BTC, and tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) were commercially available from Aladdin and used directly without further purification. The BC dispersion with a fiber content of ∼0.7 weight% was kindly provided by Hainan Yeguo Foods Co., Ltd. All water used in the current work was deionized.

Material Synthesis.

Synthesis of Zn-BTC.

In a typical process, the source materials of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (6.70 mmol, 2.00 g) and BTC (4.47 mmol, 0.94 g) were mixed in water (25 mL) and kept stirring at 80 °C for 1 h. The precipitation was then collected by filtration, followed by washing with deionized water, and subsequently subjected to freeze drying to obtain a white powder, which was denoted as sample Zn-BTC.

Synthesis of Zn-BTC@TOCN.

BC nanofibers were initially oxidized by TEMPO. First, TEMPO (0.10 mmol, 0.016 g) and NaBr (0.97 mmol, 0.1 g) were mixed in 100 mL water under stirring for 1 h. Then, the BC dispersion (230 mg BC) was introduced into the above solution. After that, the reaction was triggered by adding 6 to 14% NaClO solution (0.03 mmol, 2 mL) and concentrated HCl (0.07 mmol, 2 mL) under room temperature (RT). The pH value was adjusted to 10.0 by using 0.5 M NaOH at the end of the reaction, and the TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers were designated as sample TOCN. After introducing Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.3 mmol, 89 mg) into TOCN dispersion (25 mL, 14 mg BC), the ion exchange of Na+ with Zn2+ occurred immediately at the carboxylates on TOCN surfaces, followed by centrifugation at RT. Afterward, the formed solid product was collected and dispersed in 25 mL water/TBA mixture with a volume ratio of 5:1 (water:TBA), which contained Zn(NO3)2·6H2O and BTC with a molar ratio of 1.5:1 (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O:BTC). To investigate the effect of introduced Zn-BTC on the growth of the target product, the amounts of Zn(NO3)2·6H2O were fixed at 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mmol Zn2+ with the BC kept at 14 mg. The above mixtures were reacted under stirring at 80 °C for 1 h and then centrifuged to remove the insoluble impurities. The obtained solid product was redispersed in 25 mL water/TBA mixture with a volume ratio of 5:1 (water:TBA), followed by stirring for 5 min to form the transparent suspension. Finally, the suspension was subjected to freeze drying, and the as-fabricated productions at this stage were named as sample Zn-BTC@TOCN.

Synthesis of Zn-BTC@TOCN–derived carbon aerogels.

The as-fabricated Zn-BTC@TOCN was pyrolyzed in Ar atmosphere at temperatures of 800, 900, and 1,000 °C for 2 h, respectively, with a heating rate of 2 °C ⋅ min−1 to the desired temperature. These resultant carbon aerogels were denoted as sample ZBTCx-T, where x indicates the given ratio of Zn-BTC to TOCN (x = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1.0 mmol Zn2+, with BC kept at 14 mg) and T responds to the pyrolysis temperature (T = 800, 900, and 1,000 °C). For comparison, the precursors of Zn-BTC and TOCN were separately carbonized under Ar atmosphere at 900 °C for 2 h with the identical carbonization procedure as that of ZBTC0.8-900. The resultant products were referred to as sample ZBC-900 and TC-900, respectively.

Microstructural Characterization.

The morphology and the microstructure of the samples were characterized by field-emission SEM (S-4800, Hitachi Global) and high-resolution TEM (JEM-2100F, JEOL) equipped with EDX (Quantax-STEM). The phase compositions were characterized by XRD (D8 Advance) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) and Raman spectroscopy (Renishaw inVia) with a laser wavelength of 532 nm. The chemical states were measured by XPS (ES-CALAB 250Xi, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms were collected on a Tristar II machine (Micrometrics, ASAP 2020 HD88) at 77 K. The SSA was calculated using the adsorption data at the pressure range of P/P0 = 0 to 1 by the BET model. The pore size distribution was analyzed by the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda model using the adsorption branch of the isotherm. The compressive tests of the carbon aerogels were performed using a 5565A machine (Instron). The strain ramp rate was maintained at 10 mm ⋅ min−1 during the whole process. The surface wettability was examined by a contact angle instrument (Kruss DSA, JY-82B). The densities of the products were calculated via dividing the mass (measured by a balance with 0.01-mg accuracy) by volume (measured by digital vernier caliper).

Electrochemical Measurements.

Three-electrode system.

The CV, GCD, and EIS curves were measured using an electrochemical workstation system (Autolab, PGSTAT302N) in a three-electrode cell (Pt plate and Ag|AgCl/KCl acting as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively) as well as a symmetrical two-electrode cell under RT. The working electrode was prepared as follows: sample TC-900 and ZBTCx-T were first cut into slices sized ∼1.5 × 1.5 × 0.3 cm3 with the mass of ∼1.8 and ∼1.0 mg, respectively. After that, they were directly pressed on a nickel foam at 0.1 MPa for ∼5 s, without the addition of any binder and conductive additives. In a symmetrical two-electrode device, the total mass of both working electrodes is ∼2.0 mg. Whereas sample ZBC-900 has a powder characteristic, the electrode was prepared by the following procedure: 80 wt% ZBC-900 powder, 10 wt% carbon black, and 10 wt% poly(tetrafluoroethylene) were homogeneously mixed in ethanol/water mixture. Then, the obtained slurry was pressed into the nickel foam (1 × 1 cm2) followed by drying at 50 °C for 12 h.

The specific capacitances of the electrodes (Cs, F ⋅ g–1) in three-electrode and two-electrode systems were calculated from the discharge curves according to Eq. 1. The energy density (E, Wh ⋅ kg–1) and power density (P, W ⋅ kg–1) were calculated in accordance with Eqs. 2 and 3, respectively.

| [1] |

| [2] |

| [3] |

where I (A) is the constant current, ∆t (s) is the discharge time, ∆V (V) represents the absolute discharge potential window, m (g) responds to the total mass of carbon materials, and Cs (F ⋅ g–1) represents the specific capacitance, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 51702176 and 51972178), the Zhejiang Provincial Nature Science Foundation (Grant LY20E020009), and the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo (Grant 2019A610014).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2105610118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Huang P., et al., On-chip and freestanding elastic carbon films for micro-supercapacitors. Science 351, 691–695 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Kady M. F., et al., Engineering three-dimensional hybrid supercapacitors and microsupercapacitors for high-performance integrated energy storage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 4233–4238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shan X. Y., et al., A smart self-regenerative lithium ion supercapacitor with a real-time safety monitor. Energy Storage Mater. 1, 146–151 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gamby J., Taberna P. L., Simon P., Fauvarque J. F., Chesneaub M., Studies and characterisations of various activated carbons used for carbon/carbon supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 101, 109–116 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuertes A. B., Lota G., Centeno T. A., Frackowiak E., Templated mesoporous carbons for supercapacitor application. Electrochim. Acta 50, 2799–2805 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chmiola J., Yushin G., Dash R., Gogotsi Y., Effect of pore size and surface area of carbide derived carbons on specific capacitance. J. Power Sources 158, 765–772 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L. F., Lu Y., Yu L., Lou X. W., Designed formation of hollow particle-based nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers for high-performance supercapacitors. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1777–1783 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pan H., Li J., Feng Y., Carbon nanotubes for supercapacitor. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 5, 654–668 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Z., et al., Exceptional supercapacitor performance from optimized oxidation of graphene-oxide. Energy Storage Mater. 17, 12–21 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horn M., Gupta B., MacLeod J., Liu J., Motta N., Graphene-based supercapacitor electrodes: Addressing challenges in mechanisms and materials. Curr. Opin. Green Sust. Chem. 17, 42–48 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y., et al., High-performance asymmetric supercapacitors based on multilayer MnO2/graphene oxide nanoflakes and hierarchical porous carbon with enhanced cycling stability. Small 11, 1310–1319 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi N. S., et al., Challenges facing lithium batteries and electrical double-layer capacitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51, 9994–10024 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu J., Wang H., Gao Q., Guo H., Porous carbons prepared by using metal–organic framework as the precursor for supercapacitors. Carbon 48, 3599–3606 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen J., et al., N/P co-doped hierarchical porous carbon materials for superior performance supercapacitors. Electrochim. Acta 271, 49–57 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abioye A. M., Ani F. N., Recent development in the production of activated carbon electrodes from agricultural waste biomass for supercapacitors: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 52, 1282–1293 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y., et al., Application studies of activated carbon derived from rice husks produced by chemical-thermal process–A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 163, 39–52 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran C. C. H., Santos-Peña J., Damas C., Theoretical and practical approach of soft template synthesis for the preparation of MnO2 supercapacitor electrode. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 16–29 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wan L., Wang J., Xie L., Sun Y., Li K., Nitrogen-enriched hierarchically porous carbons prepared from polybenzoxazine for high-performance supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 15583–15596 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y., et al., Biobased nitrogen- and oxygen-codoped carbon materials for high-performance supercapacitor. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 2763–2773 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang D., et al., Synthesis of nitrogen- and sulfur-codoped 3D cubic-ordered mesoporous carbon with superior performance in supercapacitors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 2657–2665 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun H., et al., Nitrogen-doped hierarchically structured porous carbon as a bifunctional electrode material for oxygen reduction and supercapacitor. J. Alloys Compd. 826, 154208 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun L., et al., Double soft-template synthesis of nitrogen/sulfur-codoped hierarchically porous carbon materials derived from protic ionic liquid for supercapacitor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 26088–26095 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu P., et al., A novel sustainable flour derived hierarchical nitrogen-doped porous carbon/polyaniline electrode for advanced asymmetric supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1601111 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang J., et al., Thermal conversion of core-shell metal-organic frameworks: A new method for selectively functionalized nanoporous hybrid carbon. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1572–1580 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y., et al., Ultralight and robust carbon nanofiber aerogels for advanced energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 9, 900–907 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isogai A., Saito T., Fukuzumi H., TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers. Nanoscale 3, 71–85 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Y., et al., Preparation and mineralization of three-dimensional carbon nanofibers from bacterial cellulose as potential scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Surf. Coat. Tech. 205, 2938–2946 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maihom T., Probst M., Limtrakul J., Computational study of the carbonyl-ene reaction between formaldehyde and propylene encapsulated in coordinatively unsaturated metal-organic frameworks M3(btc)2 (M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn). Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 2783–2789 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ji L., et al., Morphology-dependent electrochemical sensing performance of metal (Ni, Co, Zn)-organic frameworks. Anal. Chim. Acta 1031, 60–66 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiyappa H. B., Pachfule P., Banerjee R., Kurungot S., Porous carbons from nonporous MOFs: Influence of ligand characteristics on intrinsic properties of end carbon. Cryst. Growth Des. 13, 4195–4199 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y., Hao S., Zhao H., Wang Y., Zhang X., Hierarchically porous carbons derived from nonporous metal-organic frameworks: Synthesis and influence of struts. Electrochim. Acta 180, 651–657 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chai L., et al., Bottom-up synthesis of MOF-derived hollow N-doped carbon materials for enhanced ORR performance. Carbon 146, 248–256 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pereira da Silva C. T., et al., Synthesis of Zn-BTC metal organic framework assisted by a home microwave oven and their unusual morphologies. Mater. Lett. 182, 231–234 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu W., et al., In situ fabrication of nitrogen doped porous carbon nanorods derived from metal-organic frameworks and its application as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Solid State Chem. 277, 100–106 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X., et al., A directional synthesis for topological defect in carbon. Chem 6, 1–15 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao X., et al., Defect-driven oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) of carbon without any element doping. Inorg. Chem. Front. 3, 417–421 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang W., Wu Z. Y., Jiang H. L., Yu S. H., Nanowire-directed templating synthesis of metal-organic framework nanofibers and their derived porous doped carbon nanofibers for enhanced electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 14385–14388 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang D. W., Li F., Liu M., Lu G. Q., Cheng H. M., 3D aperiodic hierarchical porous graphitic carbon material for high-rate electrochemical capacitive energy storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 373–376 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gueon D., Ju M. Y., Moon J. H., Complete encapsulation of sulfur through interfacial energy control of sulfur solutions for high-performance Li-S batteries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 12686–12692 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen H., et al., Free-standing N-self-doped carbon nanofiber aerogels for high-performance all-solid-state supercapacitors. Nano Energy 63, 103836 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu S. Y., et al., Chemically exfoliating biomass into a graphene-like porous active carbon with rational pore structure, good conductivity, and large surface area for high-performance supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702545 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hao L., Li X., Zhi L., Carbonaceous electrode materials for supercapacitors. Adv. Mater. 25, 3899–3904 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li N., Chen Z., Ren W., Li F., Cheng H. M., Flexible graphene-based lithium ion batteries with ultrafast charge and discharge rates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 17360–17365 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carriazo D., et al., Block-copolymer assisted synthesis of hierarchical carbon monoliths suitable as supercapacitor electrodes. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 773–780 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang G., Zhang L., Zhang J., A review of electrode materials for electrochemical supercapacitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 797–828 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang Z., et al., Fe, Cu-coordinated ZIF-derived carbon framework for efficient oxygen reduction reaction and zinc-air batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1802596 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mohan A. C., Renjanadevi B., Preparation of zinc oxide nanoparticles and its characterization using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray diffraction(XRD). Procedia Tech. 24, 761–766 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zabihinpour M., Ghenaatian H. R., A novel multilayered architecture of graphene oxide nanosheets for high supercapacitive performance electrode material. Synth. Met. 175, 62–67 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui J., et al., Prolifera-green-tide as sustainable source for carbonaceous aerogels with hierarchical pore to achieve multiple energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 8487–8495 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu T. C., Pell W. G., Conway B. E., Behavior of molybdenum nitrides as materials for electrochemical capacitors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 145, 1882–1888 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hao X., et al., Bacterial-cellulose-derived interconnected meso-microporous carbon nanofiber networks as binder-free electrodes for high-performance supercapacitors. J. Power Sources 352, 34–41 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen L. F., Huang Z. H., Liang H. W., Gao H. L., Yu S. H., Three-dimensional heteroatom-doped carbon nanofiber networks derived from bacterial cellulose for supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 5104–5111 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun L., et al., From coconut shell to porous graphene-like nanosheets for high-power supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 1, 6462–6470 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salunkhe R. R., et al., Fabrication of symmetric supercapacitors based on MOF-derived nanoporous carbons. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. Energy Sustain. 2, 19848–19854 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen L. F., et al., Synthesis of nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanofibers as an efficient electrode material for supercapacitors. ACS Nano 6, 7092–7102 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luo H., et al., Uniformly dispersed freestanding carbon nanofiber/graphene electrodes made by a scalable biological method for high‐performance flexible supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1803075 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang G., et al., Unconventional carbon: Alkaline dehalogenation of polymers yields N-doped carbon electrode for high-performance capacitive energy storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3340–3348 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.