Significance

Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinases PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ are essential for the development of late-onset tumors in mice with germline p53 deletion. The mechanism underlying their synthetic lethality was previously undefined. Here, we leverage structural insights of the lipid kinase to develop a highly potent and selective noncovalent inhibitor for PI5P4Kα/β. We show that pharmacological inhibition of PI5P4Kα/β disrupts cell energy homeostasis, causing AMPK activation and mTORC1 inhibition. Feedback through the S6K/insulin receptor substrate (IRS) loop contributes to insulin hypersensitivity and enhanced PI3K signaling. Most significantly, the energy stress induced by PI5P4Kα/β inhibition is selectively toxic toward p53-null tumor cells. The chemical probe may lead to a novel class of diabetes and cancer drugs.

Keywords: lipid kinase, chemical biology, p53, pip4k, synthetic lethality

Abstract

Most human cancer cells harbor loss-of-function mutations in the p53 tumor suppressor gene. Genetic experiments have shown that phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase α and β (PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ) are essential for the development of late-onset tumors in mice with germline p53 deletion, but the mechanism underlying this acquired dependence remains unclear. PI5P4K has been previously implicated in metabolic regulation. Here, we show that inhibition of PI5P4Kα/β kinase activity by a potent and selective small-molecule probe disrupts cell energy homeostasis, causing AMPK activation and mTORC1 inhibition in a variety of cell types. Feedback through the S6K/insulin receptor substrate (IRS) loop contributes to insulin hypersensitivity and enhanced PI3K signaling in terminally differentiated myotubes. Most significantly, the energy stress induced by PI5P4Kαβ inhibition is selectively toxic toward p53-null tumor cells. The chemical probe, and the structural basis for its exquisite specificity, provide a promising platform for further development, which may lead to a novel class of diabetes and cancer drugs.

There are two synthetic routes for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, or PI(4,5)P2, a versatile phospholipid with both structural and signaling functions in most eukaryotic cells (1 –3). The bulk of PI(4,5)P2 is found at the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane and is synthesized from phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate, or PI(4)P, by type 1 phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase PI4P5K (4, 5). A smaller fraction of PI(4,5)P2 is generated from the much rarer phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate, or PI(5)P, through the activity of type 2 phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase PI5P4K (6, 7). Although PI5P4K is as abundantly expressed as PI4P5K (8), its function is less well understood (9). It has been proposed that PI5P4K may play a role in suppressing PI(5)P, which is often elevated by stress (10, 11), or produce local pools of PI(4,5)P2 at subcellular compartments such as Golgi and nucleus (12).

Higher animals have three PI5P4K isoforms, α, β, and γ, which are encoded by three different genes, PIP4K2A, PIP4K2B, and PIP4K2C. The three isoforms differ, at least in vitro, significantly in enzymatic activity: PI5P4Kα is two orders of magnitude more active than PI5P4Kβ, while PI5P4K-γ has very little activity (13). PI5P4Ks are dimeric proteins (14), and the possibility that they can form heterodimers may have important functional implications, especially for the lesser active isoforms (15, 16). PI5P4Kβ is the only isoform that preferentially localizes to the nucleus (17).

Genetic studies have implicated PI5P4Kβ in metabolic regulation (18, 19). Mice with both PIP4K2B genes inactivated manifest hypersensitivity to insulin stimulation (adult males are also leaner). Although this is consistent with the observation that PI(5)P levels, which can be manipulated by overexpressing PI5P4K or a bacterial phosphatase that robustly produces PI(5)P from PI(4,5)P2, correlate positively with PI3K/Akt signaling, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain undefined (20). Both male and female PIP4K2B −/− mice are mildly growth retarded. Inactivation of the only PI5P4K isoform in Drosophila also produced small and developmentally delayed animals (21). These phenotypes may be related to suppressed TOR signaling (22, 23), but again, the underlying mechanism is unclear since TORC1 is downstream of, and positively regulated by, PI3K/Akt. Knocking out the enzymatically more active PI5P4Kα, in contrast, did not produce any overt metabolic or developmental phenotypes (19).

Malignant transformation is associated with profound changes in cell metabolism (24, 25). Although metabolic reprograming generally benefits tumor cells by increasing energy and material supplies, it can also, counterintuitively, generate unique dependencies (26, 27). Loss of p53, a tumor suppressor that is mutated in most human cancers, has been shown to render cells more susceptible to nutrient stress (28, 29) and to the antidiabetic drug metformin (30, 31). Although TP53 −/− and PIP4K2B −/− mice are themselves viable, combining the two is embryonically lethal (19). Knocking out three copies of PI5P4K (PIP4K2A −/− PIP4K2B +/− ) greatly reduces tumor formation and cancer-related death in TP53 −/− animals (19). The synthetic lethal interaction between p53 and PI5P4Kα/β was thought to result from suppressed glycolysis and increased reactive oxygen species (19), although how the lipid kinases impact glucose metabolism remains uncertain.

Given the interest in the physiological function of this alternative synthetic route for PI(4,5)P2, and the potential of PI5P4K inactivation in treating type 2 diabetes and cancer, several attempts have been made to identify chemical probes that target various PI5P4K isoforms, which yielded compounds with micromolar affinity and unknown selectivity (32 –35). Here, we report the development of a class of PI5P4Kα/β inhibitors that have much improved potency and better-defined selectivity. Using the chemical probe, we show that transient inhibition of the lipid kinases alters cell energy metabolism and induces different responses in muscle and cancer cells.

Results

Discovery of the 2-Amino-Dihydropteridinone Pharmacophore.

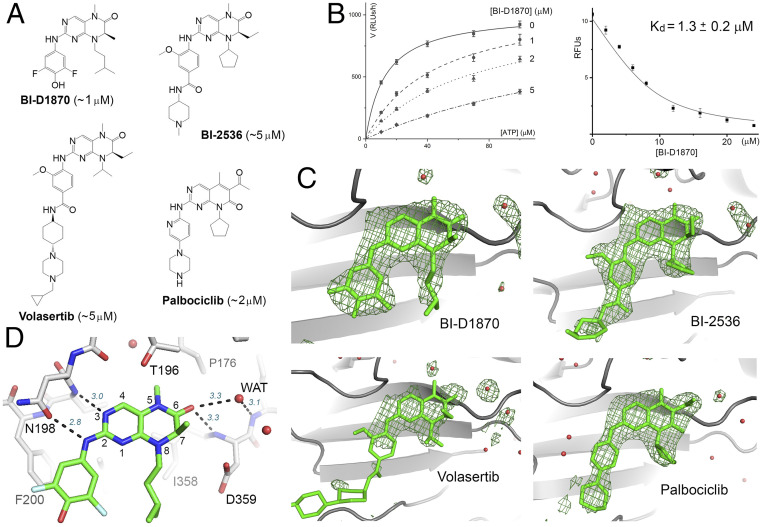

High-throughput screening of 5,759 small molecules, which included 640 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs, 515 synthetic kinase inhibitors, 446 compounds from the NIH clinical collection, and 4,158 other bioactive compounds, was conducted at the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery to identify hits against PI5P4Kα. Our assay protocol is similar to that developed by Davis et al. (33) but differs in lipid substrate preparation. Instead of dissolving the lipid in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and mixing it with assay buffer by sonication, a dried 1:2 mixture of PI(5)P and phosphatidylserine was suspended in the buffer, sonicated, and passed through a 0.2-μm extruder, which yielded unilamellar liposomes. Substrate prepared this way produced consistent results in a 384-well high-throughput assay format (Z’ ∼0.8). The top-ranking compound from the screen was a dihydropteridinone derivative called BI-D1870, which is an inhibitor for protein kinase RSK (Fig. 1A ). Kinetic studies showed that BI-D1870 is competitive with ATP and has a Ki of ∼1 μM, which was confirmed by directly measuring its binding affinity for PI5P4Kα (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1A ). Crystallographic analysis showed that BI-D1870 is bound within the ATP-binding pocket of the lipid kinase (Fig. 1C ). Our screen also produced three other compounds with identical or similar core structures: BI-2536, volasertib, and palbociclib, which are all protein kinase inhibitors but have slightly higher Kis for PI5P4Kα (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B ).

Fig. 1.

Hit molecules with a 2-amino-dihydropteridinone core. (A) The chemical structures of the hit molecules and their Kis for PI5P4Kα (shown in the parentheses). The core structure of palbociclib is slightly different but engages in similar hydrogen-bonding interactions with the kinase. (B) Michaelis–Menten curves obtained at different BI-D1870 concentrations (based on ADP-Glo measurement of relative luminescence unit, or RLU; Left). BI-D1870 displaces a bound fluorescent ATP analog from PI5P4Kα, which provides an independent measurement of its Kd (RFU, relative fluorescence unit; Right) (66). (C) Difference Fourier analysis confirms inhibitor binding to the ATP-binding pocket of PI5P4Kα. Fo-Fc maps, contoured at 3σ, are shown in green. Red spheres represent water. The cyclohexane piperazine side chain of volasertib is largely disordered. (D) Key binding interactions exemplified by the crystal structure of PI5P4Kα in complex with BI-D1870. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines with distance labeled (italic). The numbering system for pteridine is also shown.

Crystal structures of PI5P4Kα in complex with AMP-PNP and with the hit molecules were solved to assist in the design of potent and PI5P4K-specific inhibitors ( SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2). Additionally, while not relevant to inhibitor optimization, the structures also shed light on enzyme mechanisms, especially about the “specificity loop” ( SI Appendix, Fig. S2) and about ATP binding ( SI Appendix, Fig. S3). A straightforward conclusion from the crystallographic analysis is that all four compounds share the same binding mode (Fig. 1 C and D ). In contrast, the compounds bind to their respective protein kinase targets differently, with the core adopting opposing orientations (36, 37). The common 2-amino dihydropteridinone moiety is bound within the adenine binding pocket of PI5P4Kα: the 2-amino group forms a hydrogen bond with Asn-198 (a hydrogen bond between Asn-198 and Lys-140 helps orient Asn-198’s side chain carbonyl toward the 2-amino group); the N3 of the pteridinone (see Fig. 1D for atom numbers) is hydrogen bonded to the backbone amide of Val-199; and the 6-carbonyl replaces a water that is hydrogen bonded to the backbone amide of Asp-359 (“WAT1” in SI Appendix, Fig. S4). The 6-acetyl group of palbociclib is similarly posed to form hydrogen bonds with Asp-359 and Ile-360 (the latter mediated through a water molecule). The other aromatic ring linked to the 2-amino group, for example, the difluorophenol group in BI-D1870, snugly fits inside a hydrophobic cleft formed between Phe-134 and Phe-200. Phe-134 is flexible and adopts a different conformation in the complex with AMP-PNP.

Development of Potent and Selective PI5P4K Inhibitors.

The binding mode of the hit molecules resembles that of BI-2536 bound to protein kinase Plk1 (37) ( SI Appendix, Fig. S5A ). Like other type I inhibitors (38), BI-2536 binds to the active, DFG-in, conformation of the kinase (39): the DFG-in conformation enables the backbone amides of Asp-194 and Phe-195 to engage the 6-carbonyl of dihydropteridinone through water-mediated hydrogen bonds. Since dihydropteridinone is not compatible with the inactive, DFG-out, conformation of protein kinases, due to steric constraints imposed by its 6-carbonyl, a chief consideration in our effort to reengineer the protein kinase inhibitors to selectively target PI5P4K was to incorporate structural features that would have a conflict with the active conformation of protein kinases in general.

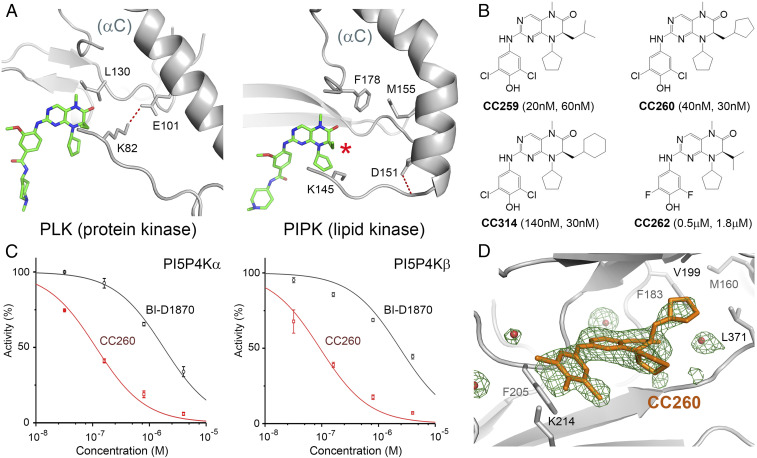

PI5P4Ks are only distantly related to the protein kinase in fold (14, 40) and harbor highly divergent structural features (41). We exploited one such feature (Fig. 2A ). In Plk1, as in all active protein kinases, there is a conserved salt bridge between Lys-82 (from a central β-strand in the N-lobe) and Glu-101 (from αC), which stabilizes the lysine for ATP binding. In PI5P4Kα, the salt bridge is missing. The helix that corresponds to αC is bent near where the glutamate should be, whereas the glutamate is replaced by a hydrophobic residue (Met-155). The kink is a defining feature of the lipid kinase family, contributing to the formation of a flat protein surface for membrane binding (14, 41). Although Asp-151, on the preceding turn of the helix, is highly conserved, it does not interact with the lysine (it is instead hydrogen bonded to Thr-148; SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B ). In Plk1, the salt bridge is immediately adjacent to the C7 ethyl side chain of BI-2536, whereas in PI5P4Kα, the kinked helix, as well as the missing salt bridge, create a deep hydrophobic pocket that is accessible from C7 of the pteridine ring (red asterisk in Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B and C ). Therefore, it seemed reasonable that we could try to introduce a bulky hydrophobic group at the C7 position of the 2-amino-dihydropteridinone pharmacophore, which would enhance the complementary fit with PI5P4K, while preventing the compound from binding to any active protein kinase.

Fig. 2.

Potent and selective lipid kinase inhibitors. (A) Comparing the binding of BI-2536 to polo-like kinase 1 (PDB: 2RKU) and PI5P4Kα. The kinked αC helix as well as the absence of a conserved salt bridge create a pocket in the lipid kinase adjacent to the C7 side chain of the bound inhibitor (indicated by the red asterisk). (B) The chemical structures of the compounds used in the biological experiments. The Ki values for PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ are shown in the parentheses. (C) Concentration-inhibition curves of CC260 (red) and BI-D1870 (black) for PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ based on measurements of 32P-labled PI(4,5)P2 resolved by TLC. ATP concentration was fixed at 20 μM in both experiments (Km,ATP for PI5P4Kα is 13 μM; Km,ATP for PI5P4Kβ is 17 μM). (D) Difference Fourier analysis confirmed the binding of CC260 to the active site of PI5P4Kβ. Fo-Fc map, shown in green, was contoured at 3σ. Red spheres represent water.

A synthetic effort was undertaken to attach various hydrophobic side chains to C7 and to swap side chains at the 2-amino group, and at N8, of the hit molecules ( SI Appendix, Figs. S6–S8). Several compounds demonstrated exceptional potency toward both PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ but not PI5P4K-γ [Fig. 2 B and C and SI Appendix, Figs. S9–S11; since PI5P4Kβ may also use GTP as the phosphodonor (42), we tested CC260’s ability to compete with GTP as well]. Compound CC259, with an isobutyl C7 side chain, is the most potent against PI5P4Kα (Ki ∼20 nM, representing a 50-fold gain over parent compound BI-D1870). Replacing the isobutyl with a cyclopentylmethyl group in CC260 improved potency toward PI5P4Kβ (Ki ∼30 nM). Increasing the size of the side chain further in CC314 started to weaken the affinity with PI5P4Kα but had no effect on PI5P4Kβ binding, making this compound a prototype for differentiating the two isoforms. The isopropyl side chain in CC262 completely destroyed the potency gain that was initially obtained. Given its structural similarity to the more active compounds, however, CC262 is still useful as a control compound in cell-based experiments (see below).

CC260 was cocrystallized with PI5P4Kβ ( SI Appendix, Table S3). Difference Fourier map confirmed that the compound was bound at the ATP-binding site, projecting its 7-cyclopentylmethyl side chain into the lipid kinase–specific pocket (Fig. 2D ). Inhibitor binding caused little conformational change in PI5P4Kβ except for the Gly-rich loop, which caps the ATP-binding site, and has been found to adopt a number of different conformations in the apo form ( SI Appendix, Fig. S12).

To test if our design was successful in achieving selectivity against protein kinases, we assayed CC260 against Plk1 and RSK2, the targets of parent compounds BI-2536 and BI-D1870 ( SI Appendix, Fig. S13). CC260 no longer inhibited Plk1 and only inhibited RSK2 weakly (Ki ∼1 μM, 50 times less potent than BI-D1870). CC260 was also profiled against a panel of 396 protein kinases (including atypical kinases; SI Appendix, Fig. S13). At a compound concentration of 0.5 μM, only seven protein kinases were mildly inhibited (EIF2AK3, 50% activity remaining; NEK11, 66%; NEK1, 67%; c-MER, 67%; TYRO3, 72%; TNIK, 73%; and PLK2, 75%), and the Kis of CC260 for these kinases were estimated to range from 250 to 1,000 nM, substantially higher than that for PI5P4Kβ.

PI4P5K (type 1 PIPK), PI5P4K (type 2), and PIKfyve (type 3) have homologous kinase domains. CC260 showed little activity against PI4P5K-α (Ki ∼5 μM) but modestly inhibited PIKfyve (Ki ∼200 nM; SI Appendix, Fig. S13). Further profiling against a panel of 14 lipid kinases showed that CC260 did not inhibit most PI3Ks, PI4Ks, or sphingosine kinases but modestly inhibited PI3K-γ (Ki ∼200 nM) and PI3K-δ (Ki ∼120 nM). This discovery was unexpected but not completely surprising because the salt bridge discussed above is not as structurally important in some of these atypical kinases as in typical protein kinases (41).

PI5P4K Inhibition Causes AMPK Activation in Cultured Myotubes.

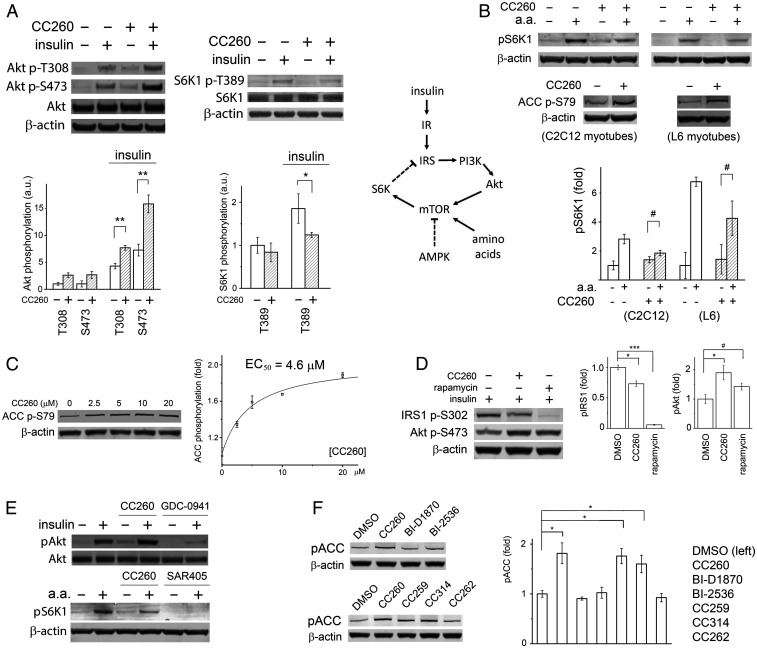

It was previously reported that PIP4K2B −/− mice were hypersensitive to insulin, with significantly enhanced Akt phosphorylation in skeletal muscles upon hormone stimulation (18). Interpretation of the phenotype was complicated, however, by the fact that the gene knockout also affected development, producing growth-retarded animals. Now equipped with a potent small-molecule PI5P4K inhibitor, we set out to test directly the effect of lipid kinase inhibition on cell signaling: in cultured C2C12 myotubes, overnight incubation with 20-μM CC260 increased hormone-induced Akt phosphorylation, especially at Ser-473 (Fig. 3A ). This result is in general agreement with the finding based on PIP4K2B −/− mice (18) but contradicts with the observation that, in dPIP4K −/− flies (Drosophila has only one PI5P4K isoform), Akt phosphorylation at Ser-505, the counterpart of mammalian Ser-473, was reduced, at least during the larval stage (21). It is possible that the effect of PI5P4K inhibition on Akt activation is context dependent. In our experiment, part of the increase in Akt phosphorylation could also be caused by PI5P4Kα inhibition (CC260 is equally potent toward PI5P4Kα), as acute removal of PI5P4Kα in cell culture through auxin degron has been found to increase Ser-473 phosphorylation (43).

Fig. 3.

PI5P4K inhibition activates AMPK in myotubes. (A) CC260 enhanced insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at both Thr-308 and Ser-473 but suppressed S6K phosphorylation by mTORC1. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 in a serum-free DMEM overnight before being stimulated by 15 nM insulin for 30 min (n = 3). (B) mTORC1 receives major inputs from growth factors through the PI3K/Akt pathway, amino acids, AMPK, stress, and hypoxia (the latter two not shown in the simplified diagram) (44). IR, insulin receptor; IRS, insulin receptor substrate. In both C2C12 and L6 myotubes, CC260 did not prevent amino acids from activating mTORC1. The myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 overnight in serum- and amino acid–free media before being transferred to serum-free media with amino acids and cultured for an additional 30 min (n = 3). (C) CC260 activated AMPK in a dose-dependent manner. C2C12 myotubes were treated with various concentrations of CC260 in a serum-free DMEM overnight before Western blot analysis (n = 3). The y-axis represents the effect (fold change) of the compound on ACC phosphorylation relative to DMSO control. (D) Enhanced Akt phosphorylation correlated with reduced IRS1 phosphorylation at Ser-302, caused by either CC260 or rapamycin treatment. C2C12 myotubes were treated with either 10 μM CC260 (overnight) or 10 nM rapamycin (1 h) and then stimulated with 15 nM insulin for 30 min (n = 3). (E) PI3K-α inhibitor GDC-0941 eliminated insulin-induced Akt phosphorylation at Ser-473. Vps34 inhibitor SAR405 prevented mTORC1 activation by amino acids. CC260 had neither of these effects. Although CC260 reduced S6K phosphorylation in myotubes, it did not inhibit mTOR/FRAP1 from the protein kinase panel. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 or 1 μM GDC-0941 overnight before being stimulated by 15 nM insulin for 30 min (n = 3). C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 or 10 μM SAR405 overnight in an amino acid–free medium before being transferred to a standard medium with amino acids for 30 min (n = 3). (F) Parent compounds BI-D1870 and BI-2536, and control compound CC262, did not increase ACC phosphorylation, whereas CC259 and CC260, equipotent toward PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ, and CC314, more specific for PI5P4Kβ, activated AMPK. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM compound overnight in serum-free media before Western blot analysis (n = 3). Quantifications of the Western blots are shown as means ± SEM, * indicates P ≤ 0.01, ** indicates P ≤ 0.001, *** indicates P ≤ 0.0001, and # indicates P ≤ 0.05 based on Student’s t test.

Both PIP4K2B −/− mice and dPIP4K −/− flies are smaller than their wild-type counterparts (18, 21). In Drosophila, this phenotype has been attributed to suppressed TORC1 signaling, as cell size and p70 S6 kinase (S6K) phosphorylation were found to be reduced in knockout animals (21 –23). Upon CC260 treatment, both basal- and insulin-induced phosphorylation of S6K at Thr-389 was reduced, confirming that mTORC1 activity was suppressed in C2C12 myotubes (Fig. 3A ).

Akt is a major activator of mTORC1 (44). The seemingly conflicting observation that CC260 enhanced Akt phosphorylation but suppressed mTORC1 signaling led us to investigate whether other inputs to mTORC1 were altered by PI5P4Kβ inhibition (Fig. 3B ). We first examined if the ability of mTORC1 to sense amino acids was compromised as this requires translocation of the TOR complex to the surface of lysosomes, a membrane compartment that could potentially be affected by lipid kinase inhibition. In contrary to this hypothesis, we found that, although CC260 reduced overall levels of S6K phosphorylation, mTORC1 activity remained sensitive to the presence of amino acids in the culture media (Fig. 3B ). We next examined if AMPK, a negative regulator of mTORC1, was affected by compound treatment. In both C2C12 and L6 myotubes, we found that CC260 significantly increased phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), another major substrate for AMPK, in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3 B and C ). Together, these data suggest a possible link between disrupted energy metabolism and the phenotypes manifested by the knockout animals (18, 19).

Suppressed mTORC1 activity provides one plausible explanation for the enhanced insulin sensitivity in myocytes: mTORC1, as well as S6K, in a negative feedback loop, phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate (IRS) on multiple serine residues, reducing its ability to activate PI3K (45) (Fig. 3B ). CC260 treatment reduced IRS phosphorylation at Ser-302, a known S6K site (46) (Fig. 3D ). Intriguingly, rapamycin, which almost eliminated Ser-302 phosphorylation, only modestly enhanced Akt phosphorylation, whereas CC260 had a more pronounced effect, suggesting that additional signaling components, for example, a lipid phosphatase (20), could be invoked upon PI5P4Kβ inactivation (Fig. 3D ).

The signaling circuitry illustrated in Fig. 3B involves two classes of lipid kinase PI3Ks. Class I PI3K, upon activation by IRS, converts PI(4,5)P2 to PI(3,4,5)P3, which recruits Akt to the plasma membrane for phosphorylation (2). Class III PI3K, or Vps34, is required for mTORC1 activation by amino acids (47). The contrasting response of C2C12 myotubes to CC260 and type I PI3K inhibitor GDC-0941, or Vps34 inhibitor SAR405, agrees with in vitro profiling results showing that p110-α/p85-α and Vps34 are not inhibited by CC260 (Fig. 3E ).

Parent compounds BI-D1870 and BI-2536 did not induce ACC phosphorylation in myotubes, suggesting that AMPK activation is a biological activity associated with the chemical modifications introduced into CC260 (Fig. 3F ). CC262, a structurally similar compound that does not potently inhibit PI5P4Kα or PI5P4Kβ in vitro, also failed to induce ACC phosphorylation. CC314, more potent against PI5P4Kβ than PI5P4Kα, enhanced ACC phosphorylation to a similar degree as CC260 or CC259.

PI5P4K Inhibition Disrupts Energy Homeostasis in Myotubes.

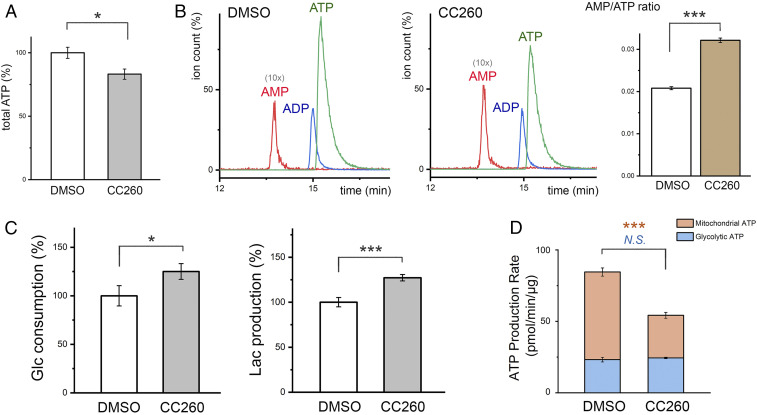

Enhanced AMPK activity suggests that cell energy metabolism was perturbed by PI5P4K inhibition (48). Measurements of intracellular ATP levels, either using a bioluminescence assay (Fig. 4A ) or by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) ( SI Appendix, Fig. S14 A and B ), consistently showed a 15% reduction in compound-treated myotubes. In contrast, ADP concentrations remained unchanged. AMP, which has a much lower concentration and overlapped with other metabolites upon HPLC fractionation, was quantified by triple quadrupole liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), which identifies the metabolite not only by its molecular weight but also by its known fragmentation pattern ( SI Appendix, Fig. S14 C and D ). The tandem mass spectrometry experiment revealed that CC260 treatment caused a 30% increase in AMP concentration or a 50% increase in AMP/ATP ratio (Fig. 4B ). The accumulation of intracellular AMP explains the observed increase in ACC phosphorylation by AMPK (48).

Fig. 4.

PI5P4K inhibition perturbs energy metabolism. (A) Total cellular ATP measured using a luminescent ATP detection assay kit (Abcam) and normalized against total protein concentration. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 overnight before the assay (n = 3). (B) Levels of intracellular AMP, ADP, and ATP measured by LC-MS/MS. The elution profiles of the control and compound-treated samples are scaled according to total ATP determined by the luminescent assay. The AMP peak is shown as 10 times the actual height for easier visualization. C2C12 myotubes were treated with 10 μM CC260 overnight before nucleotide extraction (n = 3). AMP/ATP ratio was measured in triplicate. (C) After 16 h, glucose concentrations in the media were reduced by 2.3 and 2.9 mM for cultured C2C12 myotubes treated with DMSO or 10 μM CC260, respectively (n = 3). Lactate accumulated to 3.2 and 4.0 mM (∼70% of the consumed glucose was used for fermentation). The lactate in each well (∼300 μg) is several times greater in mass than the cells (total protein ∼50 μg), suggesting that it is mainly derived from glycolysis. (D) Metabolic flux analysis quantifying mitochondrial and glycolytic ATP production rates (n = 16). Results are shown as means ± SEM, * indicates P ≤ 0.01, and *** indicates P ≤ 0.0001 based on Student’s t test. N.S., nonstatistically significant.

After 16 h of culture, CC260 increased glucose consumption and lactate secretion by about 25% (Fig. 4C ), suggesting that the disrupted energy homeostasis was not due to suppressed glycolysis. To corroborate this observation, we used a Seahorse XF Analyzer to directly examine the effect of CC260 on the energetics of C2C12 myotubes ( SI Appendix, Fig. S21A ). The Seahorse data showed that CC260 caused little change in the myotubes’ glycolytic ATP production rate (Fig. 4D ). In contrast, compound treatment negatively impacted mitochondrial ATP production, which provides one possible explanation for the disrupted energy homeostasis.

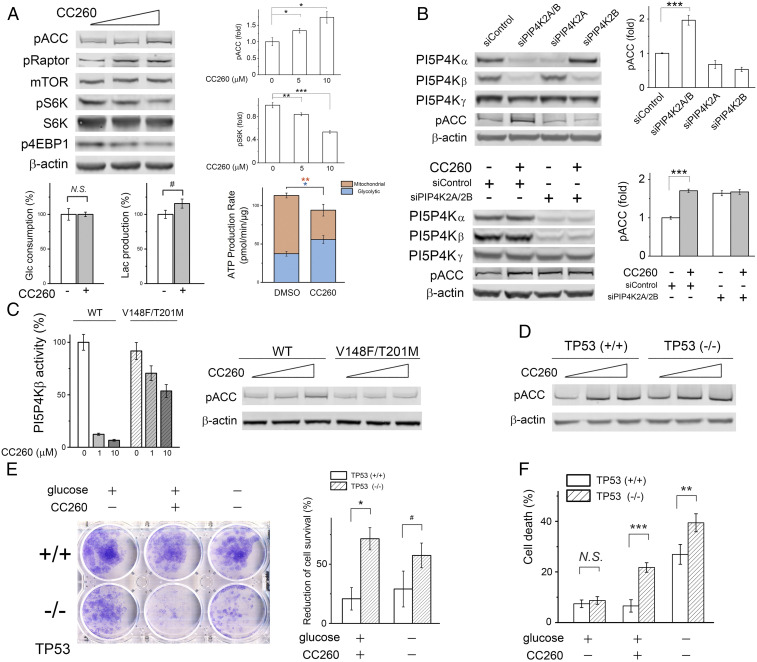

PI5P4K Inhibition Reduces Cancer Cell Survival under Nutrient Stress.

Western blot analyses showed that AMPK was also activated in CC260-treated breast cancer BT474 cells, as phosphorylation of ACC and raptor (another AMPK substrate and a regulatory component of mTORC1) were both increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S15A ). Raptor phosphorylation caused a reduction of mTORC1 activity (44), resulting in less S6K and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation. CC260 treatment caused a slight increase of total cellular PI(5)P ( SI Appendix, Fig. S15B ) but had little effect on glucose consumption by BT474 cells (Fig. 5A ). Aerobic glycolysis was slightly increased, which likely reflects the attempt of the cells to adjust to perturbed energy metabolism (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S21B ). Small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ expression in BT474 cells simultaneously, and not individually, increased ACC phosphorylation, suggesting that perturbation of energy homeostasis results from inhibition of both lipid kinase isoforms (19) (Fig. 5B ). After siRNA knockdown of PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ, no further increase in AMPK activity was achieved by CC260 treatment. To further demonstrate the on-target effect of CC260, we generated a cell line that stably expressed a mutant form of PI5P4Kβ (V148F/T201M) that is refractory to CC260 inhibition. The crystal structure suggested that, while the bulkier side chains at positions 148 and 201 sterically clash with the inhibitor, they should have a minimal impact on ATP binding ( SI Appendix, Fig. S12B ). In vitro kinase assay confirmed that the mutant retained about 90% wild-type activity but had a weaker affinity for CC260 (Ki > 10 μM; Fig. 5C ). Expressing the double mutant in BT474 cells prevented CC260-induced AMPK activation, whereas cells similarly constructed to express the wild-type kinase remained sensitive to the inhibitor (Fig. 5C ). Given the high expression level of the heterologous kinase, the resistance of the mutant-expressing cells to CC260 could result from either restored PI5P4Kβ function alone or some PI5P4Kα function as well due to compensation by the excess PI5P4K activity. Overexpression of PI5P4Kα itself caused AMPK activation, which prevented us from using the same approach to assess the contribution of its inhibition to AMPK activation ( SI Appendix, Fig. S16). The reason behind this activation is presently unclear and could involve mechanisms that are not directly related to the cells’ energy status (49).

Fig. 5.

PI5P4K inhibition reduces tumor cell survival. (A) CC260 (0, 5, and 10 μM) caused AMPK activation and mTORC1 inhibition in BT474 cells after overnight treatment in DMEM without serum (n = 4). To measure glucose consumption and lactate production, BT474 cells were cultured in DMEM without serum for 24 h (the medium did not contain pyruvate). In DMSO control, glucose concentration decreased by 7.0 mM, and the final lactate concentration was 11.9 mM (∼85% of the consumed glucose was used for lactate fermentation). With 10 μM CC260, glucose decreased by 7.0 mM while lactate accumulated to 13.8 mM (∼99% used for fermentation) (n = 3). Mitochondrial and glycolytic ATP production rates were shown as means ± SEM (n = 16). (B) Simultaneous knockdown of PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ by siRNA caused AMPK activation. Oligo “siControl” is of random sequence. After 1 d of transfection, BT474 cells were transferred to an siRNA-free DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum and cultured for 2 more days before Western blot analysis (n = 4). CC260 did not cause further AMPK activation when PI5P4Kα and PI5P4Kβ were both knocked down by siRNA (n = 3). After transfection, BT474 cells were treated with 10 μM CC260 overnight before Western blot analysis. (C) AMPK activation was abrogated in BT474 cells expressing a refractory PI5P4Kβ double mutant. Cells were treated with compound (0, 5, and 10 μM) overnight in serum-free DMEM. (Left) Comparing the in vitro activities of wild-type and mutant PI5P4Kβ at different inhibitor concentrations (n = 3). (D) CC260 caused AMPK activation in both p53+/+ and p53−/− MCF-10A cells. (E) CC260 or glucose starvation (12 h) was selectively toxic toward p53−/− cells, causing a greater reduction of the number of proliferative cells in the clonogenic assay. The area covered by the cell was quantified, and the percentage decrease was based on comparison with p53+/+ and p53−/− cells without compound treatment or glucose starvation, respectively (n = 3). (F) After overnight CC260 (10 μM) treatment or glucose starvation in serum-free DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 100 ng/mL cholera toxin, and 10 μg/mL insulin, the dead cells were measured by propidium iodide staining (n = 6). Results are shown as means ± SEM, * indicates P ≤ 0.01, ** indicates P ≤ 0.001, *** indicates P ≤ 0.0001, and # indicates P ≤ 0.05 based on Student’s t test. N.S., nonstatistically significant.

Besides myotubes and BT474 cells, CC260 caused AMPK activation in a panel of diverse breast cancer cell lines ( SI Appendix, Fig. S17). The metabolic disruption appears to be independent of the cell lines’ p53 status. BT474 harbors a temperature-sensitive p53 mutation (E285K) (19, 50). Lowering the culture temperature to 32 °C, which restores p53 function, did not alter BT474 cell’s response to PI5P4K inhibition. To directly examine the role of p53, we utilized a pair of isogenic MCF10A cell lines that differ only in the TP53 gene. Again, CC260 caused similar levels of AMPK activation in both p53+/+ and p53−/− cells (Fig. 5D ).

The metabolic stress caused by PI5P4K inhibition is detrimental to cell viability. CC260 treatment reduced the ability of BT474 cells to survive serum starvation, which could be rescued by expressing the PI5P4Kβ refractory mutant ( SI Appendix, Fig. S18). We used the MCF10A isogenic cell pair to examine if p53 influences cell survival after CC260 treatment. As shown in Fig. 5E , p53+/+ cells were only moderately affected (MCF10A cells do not form well-defined colonies like BT474 cells do, thus the area covered by the cell was used to estimate the number of cells that remained viable after treatment), while the majority of p53−/− cells lost the ability to proliferate. The increased vulnerability of p53−/− cells to energy stress is corroborated by subjecting the cells to both serum and glucose starvation. Examining the cause for the reduced number of proliferative cells, we found that CC260 treatment (or glucose starvation) significantly increased the percentage of p53−/− cells that were positive in propidium iodide staining (Fig. 5F ), the amount of LDH released into the culture medium ( SI Appendix, Fig. S19), and the number of cells that became detached from the plate, which are indicative of plasma membrane leakage and cell death. Taken together, these results suggest that pharmacological inhibition of PI5P4Kα/β could be selectively toxic toward p53−/− cells when growth factors and nutrients are scarce.

Discussion

Recent animal genetics have revealed important functions for the enigmatic type 2 PIP kinases, which catalyze an alternative PI(4,5)P2 synthetic reaction (6), in metabolic regulation (18, 19, 21), tumorigenesis (19), and immune response (51). In this study, we have developed highly potent and selective PI5P4Kα/β inhibitors and used them to interrogate the biological function of these lipid kinases (52). Our probes compare very favorably to previously reported, less-potent inhibitors (32 –35): the lead compound CC260 is based on a new pharmacophore and achieves selectivity over protein kinases by incorporating a hydrophobic side chain that occupies a pocket unique to the lipid kinase family. Profiling against a large panel of kinases representing ∼70% of the human kinome provided assurance that this probe does not cross-inhibit any protein kinase. The only significant off-target activity is against PI3K-δ, and even for this lipid kinase, the Ki is four times higher. Since PI3K-δ is minimally expressed in skeletal muscle and breast tissues (53), its inhibition is unlikely to affect our experimental interpretations. Additional evidence was also obtained to show the following: 1) siRNA knockdown of PI5P4Kα/β expression altered cell signaling in an analogous manner; 2) the change in cell physiology can be reversed by expressing a PI5P4Kβ mutant refractory to CC260 inhibition; and 3) a structurally related inactive compound failed to induce any cell response. The general agreement between our cell culture data and the phenotypes of the knockout animals added further confidence that the chemical probe engaged its intended cellular target.

A major unexpected finding of the study is that PI5P4Kα/β inhibition disrupts cell energy homeostasis, resulting in AMPK activation. Contrary to an earlier hypothesis (19), the disruption does not appear to correlate with suppressed glycolysis: in BT474 cells, CC260 treatment caused an increase in glycolytic ATP production (Fig. 5A ). The observation that this adaptation fails to restore homeostasis indicates that other aspects of energy metabolism must be affected (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation or energy expenditure). The preferred localization of PI5P4Kβ to the nucleus raises the possibility that altered nuclear phosphoinositide signaling could play a crucial role, for example, by modifying transcription. Previous studies have shown that various stresses elevate nuclear PI(5)P levels (10, 11), and several chromatin- or transcription-complex–associated proteins bind to PI(5)P (54 –56). There is also evidence that PI5P4Kβ could be phosphorylated by MAP kinase p38 in response to stress, which results in its inhibition, in an apparently positive feedback loop (10, 19). Pharmacologic inhibition of the lipid kinase may elicit a similar response, although the intensity and duration of the inactivation may also cause additional or greater changes ( SI Appendix, Fig. S20) (19, 57). A third mechanism through which PI5P4Kα/β inhibition may impact energy metabolism is by suppressing autophagy (58).

The ability of PI5P4Kα/β inactivation to suppress tumorigenesis in p53-null mice may relate to the transcription factor’s lesser-known function in cell metabolism. Besides its classic role in controlling cell cycle, senescence, and apoptosis, p53 regulates several aspects of energy metabolism (28), for example, oxidative phosphorylation (mitochondrial respiration is a significant source of ATP production in tumor cells) (59, 60). It is possible that simultaneous disruption of the two energy-related pathways is particularly detrimental to certain tumor cells under poor growth factor and nutrient conditions (Fig. 5 E and F ), and this synthetic lethal interaction contributes to the complete absence of late-onset tumors in mice with germline p53 deletion. The beneficial metabolic function of p53, and the ability of small-molecule PI5P4Kα/β inhibitors to exploit the vulnerability imposed by its loss, raises hope that the chemical probe generated in this study could be further developed to treat a wide range of p53-null tumors. Although p53 missense mutations are more common in human cancer cells, they invariably affect the transcriptional programs controlled by the functional p53 and may thus render those cells similarly susceptible to PI5P4Kα/β inhibition (50, 61). The systemic effect of AMPK activation in nonproliferating cells, especially in skeletal muscle where metformin is not effective, may also benefit patients with metabolic disorders such as obesity and type 2 diabetes. Future medicinal chemistry is required to not only optimize the lead inhibitor’s pharmacokinetic properties but also to improve its selectivity, especially over PI3K-γ/-δ expressed by immune cells, in order to test its efficacy in whole animals.

While this paper was under review, two new classes of chemical probes targeting PI5P4K were reported (62 –64). Although these inhibitors appear to have weaker affinities than CC260 in vitro, one of them can react covalently with a free cysteine adjacent to the lipid kinase’s active site, which should enhance its effectiveness and selectivity. Given their different off-target profiles, studies combining all three inhibitor classes are expected to facilitate further research into the biological functions of the enigmatic type 2 PIP kinases. Another recent study suggested that PI5P4K may allosterically regulate the type 1 PIP kinase, thereby modulating PI(4,5)P2 and PI(3,4,5)P3 levels in a catalytic-independent manner (65). It remains of great interest for future chemical biological studies to determine which aspects of the physiological changes caused by the gene knockout could be recapitulated by small-molecule PI5P4K inhibitors in intact animals.

Methods

High-Throughput Screen.

Nine compound libraries were screened at the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery (https://ycmd.yale.edu/smallmoleculecollections). Lipid vesicles [2:1 mixture of DPPS (1,2-Dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine) and PI(5)P] were prepared by sonication and extrusion in a buffer containing 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS), 20 mM Hepes pH 7.3, 200 mM NaCl, and 20 mM MgCl2, aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C. Immediately before assay, thawed lipid suspension was sonicated and extruded again and mixed with PI5P4Kα freshly purified in the same buffer. We dispensed 9 µl lipid/kinase mixture into each well of a white solid-bottom 384-well plate (Corning 3574). A total of 20 nl library compound (10 mM DMSO solution) was transferred to the well by an Aquarius system (Tecan). The plates were shaken for 30 s. Then, 1 μL ATP solution was added to initiate the reaction [final concentrations: PI(5)P 100 μM; lipid kinase 2 µg/mL; ATP 40 μM; and library compound 20 μM]. After incubating at room temperature in the dark for 1 h, 5 µl ADP-Glo reagent (Promega) was added to stop the reaction. After 40 min further incubation, 10 µl Kinase Detection reagent (Promega) was added. After 30 min, the luminescence was measured with an EnVision Multimode Plate Reader.

Enzymatic and Fluorescent Binding Assays.

In vitro kinase assay based on ADP (product) detection was performed similarly in a white solid-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3600). Within each well, 10 μL final reaction mixture contains 100 μM PI(5)P, 2 μg/mL PI5P4Kα, 10 μM ATP (in Fig. 1B , ATP concentration varied from 10 to 100 μM), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1% CHAPS, and 20 mM Hepes pH 7.3. After reaction, 10 μL ADP-Glo reagent and 20 μL Kinase Detection reagent were used for luminescence reading. Kinase assay based on PI(4,5)P2 (product) detection was carried out in a 50-μL assay mixture containing 40 μM PI(5)P, 0.4 μg/mL PI5P4Kα, 20 μM ATP (unless otherwise stated), 10 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Hepes pH 7.3, and 10 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP for 1 h at RT. For PI5P4Kβ and PI5P4K-γ, which are less active, the reaction was carried out with 4 μg/mL and 20 μg/mL enzyme, respectively, for 3 h at RT. The reaction was terminated by adding 5 μL 12N HCl. After termination, 175 μL phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer and 380 μL methanol/chloroform mix (1:1, volume[vol]/vol) containing 10 μg/mL bovine brain extract (type I; Folch Fraction I; Sigma Aldrich) were added. The lower organic phase, containing the extracted lipids, was collected and dried under vacuum. The dried lipids were resuspended in 25 μL methanol/chloroform mix (2:1, vol/vol) and separated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). For TLC, heat activated 1% potassium oxalate-coated silica gel 60 plates were used (20 cm × 20 cm, Merck), and the running solvent contained water, acetic acid, methanol, acetone, and chloroform (3:32:24:30:64 mix by vol). Radiolabeled lipid product was quantified with a phosphor imager (Bio-Rad Molecular Imager FX). Except for palbociclib, which was dissolved in water, all commercial and synthesized inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO as 10 mM stock solutions and stored at −80 °C. The inhibitor was usually incubated with the enzyme at RT for 20 min before the reaction was initiated.

A competitive binding assay was employed to directly measure the Kd of BI-D1870 for PI5P4Kα. Different amounts of kinase were mixed with 6 μM TNP-ATP (a fluorescent ATP analog) in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 2% DMSO (total vol 100 μL). Samples were gently shaken for 20 min on an orbital shaker at RT and read from a black solid-bottom 96-well plate (Corning 3650) using SpectraMax M5 plate reader (excitation 410 nm; emission 540 nm). The change in fluorescence enabled us to obtain the Kd for TNP-ATP (13 μM). Increasing amounts of BI-D1870 were then added to a mixture of 6.8 μM PI5P4Kα and 10 μM TNP-ATP in the same buffer. The displacement of TNP-ATP from the kinase by the inhibitor enabled us to calculate its Kd to be ∼1.3 μM (66).

Lactate Fermentation.

BT-474 cells were seeded onto a 12-well plate at 50% confluency and cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (phenol red-free, pyruvate-free) with 0.5% DMSO or 10 μM CC260 for 24 h. C2C12 myoblasts were plated at 80% confluency and differentiated in DMEM containing 2% horse serum for 5 d. After differentiation, the myotubes were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (phenol red-free, pyruvate-free) with 0.5% DMSO or 10 μM CC260 overnight. The culture media were collected and deproteinized by centrifugation using an Amicon Ultra centrifugal filter (3 kDa cutoff), while cells were lysed and used for protein concentration determination by bicinchoninic acid assay. The media were assayed immediately for glucose and lactate levels using colorimetric assay kits from BioVision following the manufacturer’s protocols. The values were normalized against protein concentration. All measurements were made in triplicate.

Clonogenic Assay and Propidium Iodide Staining.

BT474 cells were treated with 10 μM CC260 in low-glucose DMEM for 18 h, while MCF-10A cells were treated with 10 μM CC260 in low-glucose DMEM/F-12 medium supplemented with 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 100 ng/mL cholera toxin, and 10 μg/mL insulin for 24 h. After treatment, cells were trypsinized, counted, and seeded into 6-well plates (BT474, 2,000 cells per well; MCF-10A, 10,000 cells per well). BT474 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 12 d, and MCF-10A cells were grown in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 5% horse serum, 20 ng/mL EGF, 0.5 μg/mL hydrocortisone, 100 ng/mL cholera toxin, and 10 μg/mL insulin for 7 d. The colonies were washed with PBS and stained with a 6% glutaraldehyde/0.5% crystal violet solution for 1 h. Colony number or the area covered by cells was measured by ImageJ. Cell death was based on propidium iodide fluorescence (67). To measure the amount of cell death, the culture was treated with 5 μg/mL propidium iodide in an incubator for 1 h before fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax M5 plate reader. Total cell was determined by pretreating the culture with TX-100.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Janie Merkel and Peter Gareiss for help during the high-throughput assay setup and compound screening at the Yale Center for Molecular Discovery. We thank the staff at the Advanced Photon Source beamlines 24-ID C and E, Vivian Stojanoff (National Synchrotron Light Source/Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource), Howard Robinson (National Synchrotron Light Source), and Yagmur Muftuoglu for their assistance during X-ray diffraction data collection at the synchrotrons. We thank Gary Rudnick for sharing his imager, oscillation counter, and radioactivity room, Ben Turk for sharing his plate reader, and Karen Anderson for sharing her phosphorimager. We also thank Tommy Cheng for his advice on measuring intracellular nucleotides, Hyun Bong Park for his advice on using the LC-MS/MS equipment, Elizabeth Gullen for her help with cell culture, Rebecca Cardone and Xiaojian Zhao for their help with the Seahorse Analyzer, and Yuanwei Zhang for his help with radioactive material handling. We thank Tommy Cheng, Ben Turk, and Qin Yan for sharing breast cancer cell lines. This work was partly supported by Yale University (Y.H.), NIH grants GM112778 (to Y.H.), GM138722 (to Y.H.), and GM122473 (to J.E.), and a YCMD pilot grant (to Y.H.).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: S.C., C.C.T., J.E., and Y.H. are inventors on a patent application for the novel compounds described in this work.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2002486118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Protein structure data have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (PDB) (7N6Z, 7N71, 7N7J–7N7O, 7N80, 7N81).

Change History

November 15, 2021: A Competing Interest statement has been added; please see accompanying Correction for details.

References

- 1. Berridge M. J., Irvine R. F., Inositol phosphates and cell signalling. Nature 341, 197–205 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cantley L. C., The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296, 1655–1657 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Di Paolo G., De Camilli P., Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature 443, 651–657 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ling L. E., Schulz J. T., Cantley L. C., Characterization and purification of membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate kinase from human red blood cells. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 5080–5088 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bazenet C. E., Ruano A. R., Brockman J. L., Anderson R. A., The human erythrocyte contains two forms of phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase which are differentially active toward membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 18012–18022 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rameh L. E., Tolias K. F., Duckworth B. C., Cantley L. C., A new pathway for synthesis of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nature 390, 192–196 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Itoh T., Ijuin T., Takenawa T., A novel phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate 4-kinase (phosphatidylinositol-phosphate kinase IIgamma) is phosphorylated in the endoplasmic reticulum in response to mitogenic signals. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 20292–20299 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagaraj N., et al., Deep proteome and transcriptome mapping of a human cancer cell line. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7, 548 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fiume R., et al., PIP4K and the role of nuclear phosphoinositides in tumour suppression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1851, 898–910 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones D. R., et al., Nuclear PtdIns5P as a transducer of stress signaling: An in vivo role for PIP4Kbeta. Mol. Cell 23, 685–695 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones D. R., Foulger R., Keune W. J., Bultsma Y., Divecha N., PtdIns5P is an oxidative stress-induced second messenger that regulates PKB activation. FASEB J. 27, 1644–1656 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sarkes D., Rameh L. E., A novel HPLC-based approach makes possible the spatial characterization of cellular PtdIns5P and other phosphoinositides. Biochem. J. 428, 375–384 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Clarke J. H., Irvine R. F., Evolutionarily conserved structural changes in phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PI5P4K) isoforms are responsible for differences in enzyme activity and localization. Biochem. J. 454, 49–57 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rao V. D., Misra S., Boronenkov I. V., Anderson R. A., Hurley J. H., Structure of type IIbeta phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase: A protein kinase fold flattened for interfacial phosphorylation. Cell 94, 829–839 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang M., et al., Genomic tagging reveals a random association of endogenous PtdIns5P 4-kinases IIalpha and IIbeta and a partial nuclear localization of the IIalpha isoform. Biochem. J. 430, 215–221 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bultsma Y., Keune W. J., Divecha N., PIP4Kbeta interacts with and modulates nuclear localization of the high-activity PtdIns5P-4-kinase isoform PIP4Kalpha. Biochem. J. 430, 223–235 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ciruela A., Hinchliffe K. A., Divecha N., Irvine R. F., Nuclear targeting of the beta isoform of type II phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase) by its alpha-helix 7. Biochem. J. 346, 587–591 (2000). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lamia K. A., et al., Increased insulin sensitivity and reduced adiposity in phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase beta-/- mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5080–5087 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Emerling B. M., et al., Depletion of a putatively druggable class of phosphatidylinositol kinases inhibits growth of p53-null tumors. Cell 155, 844–857 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carricaburu V., et al., The phosphatidylinositol (PI)-5-phosphate 4-kinase type II enzyme controls insulin signaling by regulating PI-3,4,5-trisphosphate degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 9867–9872 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gupta A., et al., Phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PIP4K) regulates TOR signaling and cell growth during Drosophila development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 5963–5968 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shima H., et al., Disruption of the p70(s6k)/p85(s6k) gene reveals a small mouse phenotype and a new functional S6 kinase. EMBO J. 17, 6649–6659 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Montagne J., et al., Drosophila S6 kinase: A regulator of cell size. Science 285, 2126–2129 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hanahan D., Weinberg R. A., Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pavlova N. N., Thompson C. B., The emerging hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 23, 27–47 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim J., et al., CPS1 maintains pyrimidine pools and DNA synthesis in KRAS/LKB1-mutant lung cancer cells. Nature 546, 168–172 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maddocks O. D., et al., Serine starvation induces stress and p53-dependent metabolic remodelling in cancer cells. Nature 493, 542–546 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kruiswijk F., Labuschagne C. F., Vousden K. H., p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 393–405 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jones R. G., et al., AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 18, 283–293 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Buzzai M., et al., Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 67, 6745–6752 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang P. Y., et al., Inhibiting mitochondrial respiration prevents cancer in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 132–136 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Demian D. J., et al., High-throughput, cell-free, liposome-based approach for assessing in vitro activity of lipid kinases. J. Biomol. Screen. 14, 838–844 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Davis M. I., et al., A homogeneous, high-throughput assay for phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase with a novel, rapid substrate preparation. PloS One 8, e54127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Voss M. D., et al., Discovery and pharmacological characterization of a novel small molecule inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate 4-kinase, type II, beta. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 449, 327–331 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kitagawa M., et al., Dual blockade of the lipid kinase PIP4Ks and mitotic pathways leads to cancer-selective lethality. Nat. Commun. 8, 2200 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jain R., et al., Discovery of potent and selective RSK inhibitors as biological probes. J. Med. Chem. 58, 6766–6783 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kothe M., et al., Selectivity-determining residues in Plk1. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 70, 540–546 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang J., Yang P. L., Gray N. S., Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 28–39 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Endicott J. A., Noble M. E., Johnson L. N., The structural basis for control of eukaryotic protein kinases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 587–613 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grishin N. V., Phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase: A link between protein kinase and glutathione synthase folds. J. Mol. Biol. 291, 239–247 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Scheeff E. D., Bourne P. E., Structural evolution of the protein kinase-like superfamily. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1, e49 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sumita K., et al., The lipid kinase PI5P4Kβ is an intracellular GTP sensor for metabolism and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell 61, 187–198 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bulley S. J., et al., In B cells, phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase-α synthesizes PI(4,5)P2 to impact mTORC2 and Akt signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 10571–10576 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Laplante M., Sabatini D. M., mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Copps K. D., White M. F., Regulation of insulin sensitivity by serine/threonine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins IRS1 and IRS2. Diabetologia 55, 2565–2582 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shah O. J., Hunter T., Turnover of the active fraction of IRS1 involves raptor-mTOR- and S6K1-dependent serine phosphorylation in cell culture models of tuberous sclerosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 6425–6434 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nobukuni T., et al., Amino acids mediate mTOR/raptor signaling through activation of class 3 phosphatidylinositol 3OH-kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14238–14243 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gowans G. J., Hawley S. A., Ross F. A., Hardie D. G., AMP is a true physiological regulator of AMP-activated protein kinase by both allosteric activation and enhancing net phosphorylation. Cell Metab. 18, 556–566 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Woods A., et al., Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-beta acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metab. 2, 21–33 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Dearth L. R., et al., Inactive full-length p53 mutants lacking dominant wild-type p53 inhibition highlight loss of heterozygosity as an important aspect of p53 status in human cancers. Carcinogenesis 28, 289–298 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shim H., et al., Deletion of the gene Pip4k2c, a novel phosphatidylinositol kinase, results in hyperactivation of the immune system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 7596–7601 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arrowsmith C. H., et al., The promise and peril of chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 536–541 (2015). Corrected in: Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 541 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Uhlén M., et al., Proteomics. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 347, 1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gozani O., et al., The PHD finger of the chromatin-associated protein ING2 functions as a nuclear phosphoinositide receptor. Cell 114, 99–111 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gelato K. A., et al., Accessibility of different histone H3-binding domains of UHRF1 is allosterically regulated by phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate. Mol. Cell 54, 905–919 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Stijf-Bultsma Y., et al., The basal transcription complex component TAF3 transduces changes in nuclear phosphoinositides into transcriptional output. Mol. Cell 58, 453–467 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Puigserver P., et al., Cytokine stimulation of energy expenditure through p38 MAP kinase activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1. Mol. Cell 8, 971–982 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Lundquist M. R., et al., Phosphatidylinositol-5-Phosphate 4-kinases regulate cellular lipid metabolism by facilitating autophagy. Mol. Cell 70, 531–544.e9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Matoba S., et al., p53 regulates mitochondrial respiration. Science 312, 1650–1653 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Weinberg S. E., Chandel N. S., Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 9–15 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kastenhuber E. R., Lowe S. W., Putting p53 in context. Cell 170, 1062–1078 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Manz T. D., et al., Structure-activity relationship study of covalent pan-phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11, 346–352 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sivakumaren S. C., et al., Targeting the PI5P4K lipid kinase family in cancer using covalent inhibitors. Cell Chem. Biol. 27, 525–537.e6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Manz T. D., et al., Discovery and structure-activity relationship study of (Z)-5-Methylenethiazolidin-4-one derivatives as potent and selective pan-phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 63, 4880–4895 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wang D. G., et al., PIP4Ks suppress insulin signaling through a catalytic-independent mechanism. Cell Rep. 27, 1991–2001.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wang Z. X., An exact mathematical expression for describing competitive binding of two different ligands to a protein molecule. FEBS Lett. 360, 111–114 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Trost L. C., Lemasters J. J., A cytotoxicity assay for tumor necrosis factor employing a multiwell fluorescence scanner. Anal. Biochem. 220, 149–153 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Protein structure data have been deposited in Protein Data Bank (PDB) (7N6Z, 7N71, 7N7J–7N7O, 7N80, 7N81).