Abstract

Fungi are a large and hyper-diverse group with major taxa present in every ecosystem on earth. However, compared to other eukaryotic organisms, their diversity is largely understudied. Since the rise of molecular techniques, new lineages are being discovered at an increasing rate, but many are not accurately characterised. Access to comprehensive and reliable taxonomic information of organisms is fundamental for research in different disciplines exploring a variety of questions. A globally dominant ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungal family in terrestrial ecosystems is the Russulaceae (Russulales, Basidiomycota) family. Amongst the mainly agaricoid Russulaceae genera, the ectomycorrhizal genus Lactifluus was historically least studied due to its largely tropical distribution in many underexplored areas and the apparent occurrence of several species complexes. Due to increased studies in the tropics, with a focus on this genus, knowledge on Lactifluus grew. We demonstrate here that Lactifluus is now one of the best-known ECM genera. This paper aims to provide a thorough overview of the current knowledge of Lactifluus, with information on diversity, distribution, ecology, phylogeny, taxonomy, morphology, and ethnomycological uses of species in this genus. This is a result of our larger study, aimed at building a comprehensive and complete dataset or taxonomic framework for Lactifluus, based on molecular, morphological, biogeographical, and taxonomical data as a tool and reference for other researchers.

Citation: De Crop E, Delgat L, Nuytinck J, Halling RE, Verbeken A (2021). A short story of nearly everything in Lactifluus (Russulaceae). Fungal Systematics and Evolution 7: 133–164. doi: 10.3114/fuse.2021.07.07

Keywords: ectomycorrhizal fungi, fungal diversity, Lactarius, milkcaps, Russulales

INTRODUCTION

Fungal diversity and the need for a solid taxonomic framework

Fungi are one of the largest and most diverse groups of organisms on Earth. There are currently about 148 000 fungal species described (Cheek et al. 2020), but recent studies estimate that this is only a fraction of a total of 2.2 (6.5%)–3.8 (3.8 %) M fungal species (Hawksworth 2001, O’Brien et al. 2005, Schmit & Mueller 2007, Blackwell 2011, Hawksworth & Lücking 2017). Compared to flowering plants or vertebrates, where 80–90 % of estimated species numbers are described (Convention on Biological Diversity, CBD 2006, Pimm & Joppa 2015, Kew 2016), there is a major gap for fungi. The majority of fungi are undescribed; many are microscopic and cannot be cultured, many lineages have only been recovered with environmental sequencing, or they exist in remote and un- or underexplored areas. Likewise, even mushroom-forming lineages contain many undescribed taxa (Blackwell 2011).

One ecological guild with many mushroom-forming lineages is the ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi. Although various ECM fungi are well-studied, many species remain undiscovered or undescribed. For example, a seven-year-long study of ECM fungi in the Guiana Shield (Guyana) led to the discovery of one new ECM genus (Sanchez-Garcia et al. 2016) and new taxon discovery rates were estimated to be around 60–70 % (Henkel et al. 2012). In tropical Africa, Verbeken & Buyck (2002) estimated the number of all undescribed ECM species to be double the number of described taxa.

This large gap between the estimated and the actual described number of fungal species became especially obvious since the development of next generation sequencing (NGS) tools, where one soil sample could reveal hundreds of potential new species (e.g. in Tedersoo et al. 2014). The use of these techniques results in a much faster molecular “species” discovery (operational taxonomical units, OTU’s) than the more traditional species discovery, based on a combination of morphology, molecular data and species delimitation techniques. Unfortunately, as most fungal groups are still underexplored, the majority of these OTU’s remain unidentified, especially at species level.

A solid taxonomic framework is needed by which the metagenomic sequences generated can be compared and linked to actual species. The existence of such a framework is rare, especially in tropical or underexplored areas, while when extant, it often only holds basic information. This has major complications regarding the conclusions that can be drawn from such incomplete data. The compilation of detailed species descriptions, however, is a meticulous and time-consuming task, and a morphological description tied to a physical type specimen is needed at a minimum. This is not always easily available for fungi, for example for many microscopic fungi (Taylor et al. 2006, Hibbett 2016), or for species only known from environmental sequences.

The predominantly tropical ECM genus Lactifluus (Russulaceae) has been extensively studied during recent years, resulting in the availability of a solid phylogeny, combined with a revised taxonomy (De Crop et al. 2017). With this review, we want to contribute to the knowledge of this genus and supplement its taxonomic framework with detailed information on diversity, morphology, and ecology. We give an overview of all 224 described Lactifluus species, accompanied by information on their subgeneric classification and quality of those data. We discuss the distribution of Lactifluus species and their ecology, and we explore publicly available metabarcoding data and discuss their impact on our current knowledge of Lactifluus. We provide a thorough overview of macro- and microscopical features of Lactifluus species and discuss their use as renewable natural resources.

Russulales

In 1796 and 1797, Persoon described the genera Russula and Lactarius as discrete genera of agaricoid fungi, differing primarily from other genera by their brittle context. Russula species have sporocarps with strikingly coloured caps and Lactarius species exude a milk-like solution (latex) when sporocarps are bruised (Persoon 1796, 1797). Due to their striking morphological characteristics, Lactarius and Russula were later classified in their own order, Russulales, within Agaricomycetes with pale-coloured spores (Kreisel 1969, Oberwinkler 1977). Morphologically, this classification was mainly supported by microscopical features such as sphaerocytes in the trama, responsible for the brittle context, amyloid spore ornamentation and a gloeoplerous hyphal system (i.e. hyphae with long cells that contain numerous oil droplets in the cytoplasm; Fig. 1). Combinations of these characters were also found in several taxa with other basidiocarp types and were included in this order (Romagnesi 1948, Donk 1971, Oberwinkler 1977). Next to the agaricoid Russula and Lactarius, Russulales further comprised coral fungi (Artomyces; Jülich 1981), poroid fungi (Heterobasidion), hydnoid fungi (Echinodontium, and Hericium) and corticioid fungi (Gloeocystidiellum, Boidinia, and Gloiothele).

Fig. 1.

A. Sphaerocytes within the trama of Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-060). B. Amyloid spore ornamentation of Lf. russulisporus (REH 9398). C. Gloeocystidia in Gloeocystidiellum porosum [Photographs by E. De Crop (A, B) and N. Schoutteten (C)].

Over the last two decades, molecular phylogenetic research contributed to a revision of the Russulales. Molecular data showed strong support for a russuloid clade with corticioid, resupinate, discoid, clavarioid, pileate, effused-reflexed, and gasteroid taxa with smooth, poroid, hydnoid, lamellate or labyrinthoid hymenophores (Fig. 2), but not all shared sphaerocytes and amyloid spore ornamentation (Hibbett et al. 1997, Hibbett & Binder 2002, Larsson & Larsson 2003, Larsson et al. 2004, Miller et al. 2006, Buyck et al. 2008). The Russulales order is morphologically supported by the presence of gloeocystidia or a gloeoplerous hyphal system (Larsson & Larsson 2003, Miller et al. 2006).

Fig. 2.

Different types of sporocarps and hymenophores within the Russulales. A. Clavarioid sporocarp of Artomyces pyxidatus. B. Effused-reflexed sporocarps with smooth hymenium of Stereum rugosum. C. Pileate sporocarp with hydnoid hymenium of Auriscalpium sp. (EDC 14-511). D. Resupinate sporocarp with smooth hymenium of Peniophora incarnata. E. Discoid sporocarp with smooth hymenium of Aleurodiscus disciforme. F. Pileate sporocarp with lamellate hymenium of Lactifluus urens (EDC 12-032) [Photographs by R. Walleyn (A, B), E. De Crop (C, F) and N. Schoutteten (D, E)].

Russula, Lactarius and some pleurotoid and sequestrate genera form a discrete group within this clade and circumscribe the Russulaceae (Redhead & Norvell 1993, Miller et al. 2001, Larsson & Larsson 2003, Eberhardt & Verbeken 2004, Nuytinck et al. 2004).

Russulaceae

Before 2000, Russulaceae classification was mainly based on morphological characters such as sporocarp type. Agaricoid species were placed in Russula and Lactarius. Pleurotoid species were placed in Pleurogala. Sequestrate species were classified as Arcangeliella, Gastrolactarius, Zelleromyces, Cystangium, Elasmomyces, Gymnomyces, Martellia and Macowanites. Veiled species were placed in the genus Lactariopsis. Generic concepts in the mushroom-forming Russulaceae changed when hypotheses were advanced that pleurotoid, sequestrate and veiled forms originated several times, both in Lactarius and Russula. Morphological and molecular studies of pleurotoid Russulaceae species (Verbeken 1998, Buyck & Horak 1999, Henkel et al. 2000), supported placement in either Russula or Lactarius. Hence, Pleurogala (Redhead & Norvell 1993) was abandoned. Likewise, sequestrate species originally allied to Lactarius (Arcangeliella, Gastrolactarius and Zelleromyces) and Russula (Cystangium, Elasmomyces, Gymnomyces, Martellia and Macowanites) were reclassified (Calonge & Martín 2000, Miller et al. 2001, Binder & Bresinsky 2002, Desjardin 2003, Nuytinck et al. 2003, Eberhardt & Verbeken 2004, Lebel & Tonkin 2007, Verbeken et al. 2014). Species with a velum occur both in Lactarius and Russula. This is in line with the standpoint of Verbeken (1998) and abandons the separate genus in which they were placed by other authors (Hennings 1902, Heim 1937, Redhead & Norvell 1993). From 2003 on, molecular analyses indicated that Russulaceae also contains several corticioid taxa from three genera: Boidinia, Gloeopeniophorella and Pseudoxenasma (Larsson & Larsson 2003, Miller et al. 2006).

Buyck et al. (2008) constructed a phylogeny of the agaricoid Russulaceae genera. They focused on more tropical taxa than previous studies. In some cases, tropical Lactarius and Russula species turned out to be indistinguishable from each other based on morphology. Their results showed that Lactarius and Russula were not two well-defined and separate clades. Russula appears to be monophyletic only if a small group of species is excluded. The genus Russula sensu Buyck et al. (2008) is the largest Russulaceae genus, with more than 750–900 species described all over the world (Kirk et al. 2008, Buyck & Atri 2011, Looney et al. 2016). The majority of Russula species is agaricoid, but some are pleurotoid or sequestrate, and veiled species are also known (Fig. 3). All species lack latex production and lack pseudocystidia. They are characterised by a brittle context caused by sphaerocytes in the context and trama, and by the presence of bright pigments, especially in the cap (usually contrasting with a white or whitish stipe and gills that vary from white to yellow, depending on the colour of the spores).

Fig. 3.

Different Russula species. A. Agaricoid species Russula sp. (EDC 12-063). B. Agaricoid species Russula sp. (EDC 12-058). C. Annulate agaricoid species Russula sp. (EDC 14-381). D. Annulate agaricoid species Russula sp. (EDC 14-040). E. Secotoid species Russula sp. (former Macowanites sp.) (REH 9496). F. Pleurotoid species R. campinensis (TH 9252) [Photographs by E. De Crop (A–D), R. Halling (E) and T. Henkel (F)].

A small group of species excluded from the former Russula forms a clade together with some Lactarius species. This clade was described as the new genus Multifurca (Buyck et al. 2008). The former Russula subsect. Ochricompactae, the Asian species Russula zonaria and the American species Lactarius furcatus were included in this genus. Multifurca species are characterised by furcate lamellae, dark yellowish lamellae and spore-prints, a strong zonation of pileus and context (Fig. 4). Latex is only present in some Multifurca species and the presence of latex seems to be a variable character in this genus, even within one species. Only 11 Multifurca species are currently known (Buyck et al. 2008, Wang & Liu 2010, Lebel et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2018) from three biogeographic regions: Asia, Australasia and North/Central America.

Fig. 4.

Different Multifurca species. A. M. zonaria (FH 12-009). B. Detail on zonate context of M. zonaria. C. M. pseudofurcata (xp2-20120922-01) [Photographs by F. Hampe (A), A. Verbeken (B) and G. Jiayu (C)].

The remainder of Lactarius was split in two different clades (Buyck et al. 2008). One large clade contained the majority of described milkcap species (about 75 % of those known) and one smaller clade with mainly tropical species. At that time, this smaller clade contained the type species of Lactarius: Lactarius piperatus. A proposal to conserve Lactarius (hereafter abbreviated as L.) with a conserved type species, Lactarius torminosus was accepted (Buyck et al. 2010, McNeill et al. 2011) and the name Lactarius has been retained for the larger clade (Fig. 5). The subgenera L. subg. Lactarius (the former L. subg. Piperites), L. subg. Russularia, and L. subg. Plinthogalus, together with several undescribed tropical lineages that need to be described at subgenus level (Nuytinck et al. 2020), now constitute the larger milkcap genus Lactarius sensu Buyck et al. (2008), Buyck et al. (2010). Approximately 450 species are accepted in Lactarius, which occurs worldwide but has its main distribution in the temperate and boreal regions.

Fig. 5.

Different Lactarius species. A. L. torminosus (JN 2011-087). B. L. deliciosus (JN 2003-055). C. L. lacunarum. D. L. tenellus (EDC 14-064). E. L. chromospermus (EDC 14-108). F. L. stephensii (EDC 14-575) [Photographs by J. Nuytinck (A, B), A. Verbeken (C) and E. De Crop (D–F)].

The smaller milkcap group, with approximately 200 described species, is named Lactifluus (hereafter abbreviated as Lf.) and is automatically typified by Agaricus lactifluus, currently known as Lf. volemus (Buyck et al. 2010). New combinations were made in a series of three papers for the different subgenera (Verbeken et al. 2011, Stubbe et al. 2012b, Verbeken et al. 2012).

The two milkcap genera, Lactarius and Lactifluus, are well-supported based on molecular inference, but no synapomorphic characteristics have been found to consistently separate both genera. The morphological distinction between the genera is thus far based on several trends:

Characteristics of the pileus – Lactifluus is generally characterised by the complete absence of zonate and viscose to glutinous caps, while it contains many species with velvety caps, and even some with veiled caps. Lactarius however, contains many species with zonate and viscose to glutinous caps (Verbeken & Nuytinck 2013). Veiled species are not known in Lactarius.

Sporocarp characteristics – pleurotoid milkcap species are so far only known in Lactifluus (Buyck et al. 2008, Verbeken & Nuytinck 2013), sequestrate species are most common in Lactarius, but were recently found to occur in Lactifluus too (Lebel et al. 2016).

Hymenophoral trama – the hymenophoral trama of Lactifluus species is mostly composed of sphaerocytes, which is also common in Russula (Verbeken & Nuytinck 2013). In contrast, these sphaerocytes are only rarely observed in Lactarius species, where the hymenophoral trama most often is composed of filamentous hyphae only.

Thick-walled elements – thick-walled elements in the pileipellis, stipitipellis and hymenophoral trama are common in the genus Lactifluus, while they are hardly observed in the genus Lactarius (Verbeken & Nuytinck 2013).

These features might be helpful when identifying milkcap species, but they are not exclusive. There are species, especially in the tropics, in which a molecular characterisation is needed to determine to which genus they belong.

THE GENUS LACTIFLUUS

Diversity and distribution

The milkcap genus Lactifluus is predominantly present in the tropics. Mainly due to this distribution, Lactifluus has long been understudied compared to its sister Lactarius. Before the start of our study of the genus Lactifluus at the end of 2010, the highest diversity of the genus was known from sub-Saharan Africa, with 60 species described (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010), and Asia, with 23 species described (Le et al. 2007, Stubbe et al. 2010, Van de Putte et al. 2010). However, the genus also appears to be well-represented in South America, as new species are being discovered since more South American habitats are being explored (Henkel et al. 2000, Miller et al. 2002, Smith et al. 2011, Sá et al. 2013, Sá & Wartchow 2013, Crous et al. 2017, Delgat et al. 2019, Delgat et al. 2020, Duque Barbosa et al. 2020), and the majority of the proposed South American Lactarius species turns out to belong in Lactifluus (Pegler & Fiard 1979, Singer et al. 1983, Miller et al. 2002). Since 2010, 78 new Lactifluus species have been described: 34 from Asia (Stubbe et al. 2012a, Van de Putte et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2012, Wang et al. 2015, Morozova et al. 2013, Latha et al. 2016, Li et al. 2016, Uniyal et al. 2016, Zhang et al. 2016, Das et al. 2017, Hyde et al. 2017, Song et al. 2017, De Crop et al. 2018, Liu et al. 2018, Song et al. 2018, Bera & Das 2019, Dierickx et al. 2019a, b, Phookamsak et al. 2019), 16 from Africa (De Crop et al. 2012, Maba et al. 2014, Maba et al. 2015a, b, De Crop et al. 2016a, b, De Crop et al. 2019, Delgat et al. 2017, De Lange et al. 2018), 20 from the Neotropics (Miller et al. 2012, Montoya et al. 2012, Sá et al. 2013, Sá & Wartchow 2013, Wartchow et al. 2013, Crous et al. 2017, Crous et al. 2019, Delgat et al. 2019, Delgat et al. 2020, Sá et al. 2019, Duque Barbosa et al. 2020, Silva et al. 2020), seven from Australasia (Stubbe et al. 2012a, Kropp 2016, Dierickx et al. 2019a, b, Crous et al. 2020a, b), and one species from Europe (Van de Putte et al. 2016). This brings the total number of described Lactifluus species to 226. However, recent phylogenetic studies suggest that there are more lineages that represent new species (De Crop et al. 2017; Delgat & De Crop unpubl.). De Crop (2016) performed a worldwide phylogeny of 1 306 Lactifluus ITS sequences on which species were delimited using the GMYC method (Pons et al. 2006). This resulted in 369 putative Lactifluus species. Based on this number of species and using a species accumulation curve, the total number of Lactifluus species was estimated to be around 530 species (De Crop 2016, He et al. 2019, Nuytinck et al. 2020). Although this is a rough estimate, it indicates that the majority of Lactifluus species is still undescribed. Many known species-level clades are not described yet because they lack detailed documentation, or they are singletons, and describing species is a laborious work.

So far, none of the Lactifluus species occurs with certainty on two or more continents (Table 1). Although, some species records used to suggest otherwise. For example, collections identified as the North American Lf. luteolus based on morphology were also found in Europe, Asia and Australia. All collections have typical cream-beige sporocarps, which exude white milk that quickly stains brownish. However, a recent molecular study of Dierickx et al. 2019b showed that Lf. luteolus is a North American species. The records from other continents represent different species. Another example is the North American species Lf. hygrophoroides which was also reported from Asia. However, preliminary molecular results show the existence of multiple clades identified as Lf. hygrophoroides, each clade occurring on one continent, instead of one intercontinental species (De Crop, unpubl.). The recently described Australian species Lf. austropiperatus forms a strongly supported clade with a Thai specimen, however, the authors maintain the Australian material as distinct until further collections from Thailand can be examined and sequenced (Crous et al. 2020b). In all other known cases of possible intercontinental species, molecular inference rejected this possibility (Stubbe et al. 2010, Van de Putte et al. 2010, De Crop et al. 2014).

Table 1.

List of described Lactifluus species, together with the current authors, the original publication, and biogeographical region of origin. Biogeographic regions are based on biogeographic realms (https://ecoregions2017.appspot.com/), with three major differences: Western Palearctic (Western part of the Palearctic realm), Asia (Eastern part of the Palearctic realm combined with the Indo-Malay realm), and Australasia (Australasian realm combined with the Oceanian realm). See Supplementary data (Figure S1) for an overview of the biogeographical regions used. Varieties of species are not included in this list. See supplementary data (Table S1) for more information on the classification of the Lactifluus species.

| Name | Current authors | Original publication | Biogeographical region | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lf. acicularis | (Van de Putte & Verbeken) Van de Putte | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 2 | Lf. acrissimus | (Verbeken & Van Rooij) Nuytinck | Van Rooij et al. 2003 | Afrotropics |

| 3 | Lf. adustus | (Rick) Delgat comb. nov. | Rick (1938) | Neotropics |

| 4 | Lf. albocinctus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2000 | Afrotropics |

| 5 | Lf. albomembranaceus | De Wilde & Van de Putte | De Crop et al. 2016 | Afrotropics |

| 6 | Lf. albopicri | T. Lebel & L. Tegart | Crous et al. 2020b | Australasia |

| 7 | Lf. allardii | (Coker) De Crop | Coker (1918) | Nearctic |

| 8 | Lf. amazonensis | (Singer) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 9 | Lf. ambicystidiatus | X.H. Wang | Wang et al. 2015 | Asia |

| 10 | Lf. angustifolius | (Hesler & A.H. Sm.) De Crop | Hesler & Smith (1979) | Nearctic |

| 11 | Lf. angustus | (R. Heim & Gooss.-Font.) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 12 | Lf. annulatoangustifolius | (Beeli) Buyck | Beeli (1936) | Afrotropics |

| 13 | Lf. annulatolongisporus | Maba | Maba et al. 2015a | Afrotropics |

| 14 | Lf. annulifer | (Singer) Nuytinck | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 15 | Lf. arcuatus | (Murrill) Delgat | Murrill (1941) | Western Palearctic |

| 16 | Lf. armeniacus | De Crop & Verbeken | Li et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 17 | Lf. arsenei | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 18 | Lf. atrovelutinus | (J.Z. Ying) X.H. Wang | Ying (1991) | Asia |

| 19 | Lf. aurantiifolius | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 20 | Lf. aurantiorugosus | Sá & Wartchow | Sá & Wartchow (2013) | Neotropics |

| 21 | Lf. aurantiotinctus | Kropp | Kropp (2016) | Australasia |

| 22 | Lf. aureifolius | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 23 | Lf. auriculiformis | Verbeken & Hampe | De Crop et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 24 | Lf. austropiperatus | T. Lebel & L. Tegart | Crous et al. 2020b | Australasia |

| 25 | Lf. austrovolemus | (Hongo) Verbeken | Hongo (1973) | Australasia |

| 26 | Lf. batistae | Wartchow, J.L. Bezerra & M. Cavalc. | Wartchow et al. 2013 | Neotropics |

| 27 | Lf. bertillonii | (Neuhoff ex Z. Schaef.) Verbeken | Schaefer (1979) | Western Palearctic |

| 28 | Lf. bhandaryi | Verbeken & De Crop | De Crop et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 29 | Lf. bicapillus | Lescroart & De Crop | De Crop et al. 2019 | Afrotropics |

| 30 | Lf. bicolor | (Massee) Verbeken | Massee (1914) | Asia |

| 31 | Lf. brachystegiae | (Verbeken & C. Sharp) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2000 | Afrotropics |

| 32 | Lf. brasiliensis | (Singer) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 33 | Lf. braunii | (Rick) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Rick (1930) | Neotropics |

| 34 | Lf. brunellus | (S.L. Mill., Aime & T.W. Henkel) De Crop | Miller et al. 2002 | Neotropics |

| 35 | Lf. brunneocarpus | Maba | Maba et al. 2015a | Afrotropics |

| 36 | Lf. brunneoviolascens | (Bon) Verbeken | Bon (1971) | Western Palearctic |

| 37 | Lf. brunnescens | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 38 | Lf. burkinabei | Maba | Maba et al. 2015a | Afrotropics |

| 39 | Lf. caatingae | Sá & Wartchow | Sá et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 40 | Lf. caeruleitinctus | (Murrill) Delgat | Murrill (1939) | Western Palearctic |

| 41 | Lf. caliendrifer | Froyen & De Crop | Dierickx et al. 2019 | Asia |

| 42 | Lf. caperatus | (R. Heim & Gooss.-Font.) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 43 | Lf. caribaeus | (Pegler) Verbeken | Pegler & Fiard (1979) | Neotropics |

| 44 | Lf. carmineus | (Verbeken & Walleyn) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2000 | Afrotropics |

| 45 | Lf. catarinensis | J. Duque, M.A. Neves & M. Jaegger | Duque Barbosa et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 46 | Lf. ceraceus | Delgat & M. Roy | Crous (2017) | Neotropics |

| 47 | Lf. chamaeleontinus | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 48 | Lf. chiapanensis | (Montoya, Bandala-Muñoz & Guzmán) De Crop | Montoya et al. 1996 | Neotropics |

| 49 | Lf. chrysocarpus | E. S. Popov & O.V. Morozova | Morozova et al. 2013 | Asia |

| 50 | Lf. claricolor | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 51 | Lf. clarkeae | (Cleland) Verbeken | Cleland (1927) | Australasia |

| 52 | Lf. coccolobae | (O. K. Miller & Lodge) Delgat | Miller et al. 2000 | Neotropics |

| 53 | Lf. cocosmus | (Van de Putte & De Kesel) Van de Putte | Van de Putte et al. 2009 | Afrotropics |

| 54 | Lf. conchatulus | (Stubbe & H.T. Le) Stubbe | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 55 | Lf. coniculus | Stubbe & Verbeken | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 56 | Lf. corbula | (R. Heim & Gooss.-Font.) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 57 | Lf. corrugis | (Peck) Kuntze | Peck (1879) | Nearctic |

| 58 | Lf. crocatus | Van de Putte & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 59 | Lf. cyanovirescens | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 60 | Lf. deceptivus | (Peck) Kuntze | Peck (1885) | Nearctic |

| 61 | Lf. denigricans | (Verbeken & Karhula) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996b) | Afrotropics |

| 62 | Lf. densifolius | (Verbeken & Karhula) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 63 | Lf. dinghuensis | Jianbin | Zhang et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 64 | Lf. dissitus | Van de Putte, K. Das & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 65 | Lf. distans | (Peck) Kuntze | Peck (1873) | Nearctic |

| 66 | Lf. distantifolius | Van de Putte, Stubbe & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 67 | Lf. domingensis | Delgat & Angelini | Delgat et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 68 | Lf. dunensis | Sá & Wartchow | Sá et al. 2013 | Neotropics |

| 69 | Lf. dwaliensis | (K. Das, J.R. Sharma & Verbeken) K. Das | Das et al. 2003 | Asia |

| 70 | Lf. echinatus | (Thiers) De Crop comb. nov. | Thiers (1957) | Nearctic |

| 71 | Lf. edulis | (Verbeken & Buyck) Buyck | Buyck (1994) | Afrotropics |

| 72 | Lf. emergens | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2000 | Afrotropics |

| 73 | Lf. epitheliosus | (Buyck & Courtec.) Delgat comb. nov. | Courtecuisse & Buyck (1991) | Neotropics |

| 74 | Lf. fazaoensis | Maba, Yorou & Guelly | Maba et al. 2014 | Afrotropics |

| 75 | Lf. flammans | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 76 | Lf. flavellus | Maba & Guelly | Maba et al. 2015b | Afrotropics |

| 77 | Lf. flocktonae | (Cleland & Cheel) Lebel | Cleland & Cheel (1919) | Australasia |

| 78 | Lf. foetens | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Van Rooij et al. 2003 | Afrotropics |

| 79 | Lf. fuscomarginatus | (Montoya, Bandala & Haug) Delgat | Montoya et al. 2012 | Neotropics |

| 80 | Lf. genevievae | (Stubbe & Verbeken) Stubbe | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Australasia |

| 81 | Lf. gerardiellus | Wisitrassameewong & Verbeken | De Crop et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 82 | Lf. gerardii | (Peck) Kuntze | Peck (1874) | Nearctic |

| 83 | Lf. glaucescens | (Crossl.) Verbeken | Crossland (1900) | Western Palearctic |

| 84 | Lf. goossensiae | (Beeli) Verbeken | Beeli (1928) | Afrotropics |

| 85 | Lf. guadeloupensis | Delgat & Courtec. | Delgat et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 86 | Lf. guanensis | Delgat & Lodge | Crous et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 87 | Lf. guellii | Maba | Maba et al. 2015a | Afrotropics |

| 88 | Lf. gymnocarpoides | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 89 | Lf. gymnocarpus | (R. Heim ex Singer) Verbeken | Singer (1948) | Afrotropics |

| 90 | Lf. hallingii | Delgat & De Wilde | Delgat et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 91 | Lf. heimii | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 92 | Lf. holophyllus | H. Lee & Y.W. Lim | Hyde et al. 2017 | Asia |

| 93 | Lf. hora | Stubbe & Verbeken | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 94 | Lf. hygrophoroides | (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Kuntze | Berkeley & Curtis (1859) | Nearctic |

| 95 | Lf. igniculus | O.V. Morozova & E.S. Popov | Morozova et al. 2013 | Asia |

| 96 | Lf. ignifluus | (Vrinda & C. K. Pradeep) De Crop comb. nov. | Vrinda et al. 2002 | Asia |

| 97 | Lf. indicus | K.N.A. Raj & Manim. | Latha et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 98 | Lf. indovolemus | I. Bera & K. Das | Bera & Das (2019) | Asia |

| 99 | Lf. indusiatus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 100 | Lf. inversus | (Gooss.-Font. & R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 101 | Lf. kigomaensis | De Crop & Verbeken | De Crop et al. 2012 | Afrotropics |

| 102 | Lf. kivuensis | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 103 | Lf. lactiglaucus | P. Leonard & Dearnaley | Crous et al. 2020a | Australasia |

| 104 | Lf. laevigatus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 105 | Lf. lamprocystidiatus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (2000) | Australasia |

| 106 | Lf. latifolius | (Gooss.-Font. & R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 107 | Lf. leae | Stubbe & Verbeken | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 108 | Lf. leonardii | Stubbe & Verbeken | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Australasia |

| 109 | Lf. leoninus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (1999) | Australasia |

| 110 | Lf. leptomerus | Van de Putte, K. Das & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 111 | Lf. lepus | Delgat & Courtec. | Delgat et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 112 | Lf. leucophaeus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (1999) | Australasia |

| 113 | Lf. limbatus | Stubbe & Verbeken | Stubbe et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 114 | Lf. longibasidius | Maba & Verbeken | Maba et al. 2015b | Afrotropics |

| 115 | Lf. longipes | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 116 | Lf. longipilus | Van de Putte, Le & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 117 | Lf. longisporus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 118 | Lf. longivelutinus | (X.H. Wang & Verbeken) X.H. Wang | Wang & Verbeken (2006) | Asia |

| 119 | Lf. lorenae | Montoya, Caro, Ramos & Bandala | Montoya et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 120 | Lf. luteolamellatus | H. Lee & Y.W. Lim | Hyde et al. 2017 | Asia |

| 121 | Lf. luteolus | (Peck) Verbeken | Peck (1896) | Nearctic |

| 122 | Lf. luteopus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 123 | Lf. madagascariensis | (Verbeken & Buyck) Buyck | Buyck et al. 2007 | Afrotropics |

| 124 | Lf. maenamensis | K. Das, D. Chakr. & Buyck | Das et al. 2017 | Asia |

| 125 | Lf. mamorensis | (Rick) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 126 | Lf. marielleae | J. Duque & M.A. Neves | Duque Barbosa et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 127 | Lf. marmoratus | Delgat | Delgat et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 128 | Lf. medusae | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 129 | Lf. melleus | Maba | Maba et al. 2015b | Afrotropics |

| 130 | Lf. membranaceus | Maba | Maba et al. 2015a | Afrotropics |

| 131 | Lf. mexicanus | Montoya, Caro, Bandala & Ramos | Montoya et al. 2019 | Neotropics |

| 132 | Lf. midnapurensis | S. Paloi & K. Acharya | Phookamsak et al. 2019 | Asia |

| 133 | Lf. mordax | (Thiers) Delgat | Thiers (1957) | Nearctic |

| 134 | Lf. multiceps | (S.L. Miller, Aime & TW Henkel) De Crop | Miller et al. 2002 | Neotropics |

| 135 | Lf. murinipes | (Pegler) De Crop | Pegler & Fiard (1979) | Neotropics |

| 136 | Lf. nebulosus | (Pegler) De Crop | Pegler & Fiard (1979) | Neotropics |

| 137 | Lf. neotropicus | (Singer) Nuytinck | Singer (1952) | Neotropics |

| 138 | Lf. neuhoffii | (Hesler & A.H. Sm.) De Crop | Hesler & Smith (1979) | Nearctic |

| 139 | Lf. nodosicystidiosus | (Verbeken & Buyck) Buyck | Buyck et al. 2007 | Afrotropics |

| 140 | Lf. nonpiscis | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 141 | Lf. novoguineensis | (Henn.) Verbeken | Hennings (1898) | Australasia |

| 142 | Lf. ochrogalactus | (Hashiya) X.H. Wang | Wang et al. 2006 | Asia |

| 143 | Lf. oedematopus | (Scop.) Kuntze | Scopoli (1772) | Western Palearctic |

| 144 | Lf. olivescens | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (2000) | Australasia |

| 145 | Lf. paleus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (1999) | Australasia |

| 146 | Lf. pallidilamellatus | (Montoya & Bandala) Van de Putte | Montoya & Bandala (2004) | Neotropics |

| 147 | Lf. pallidipes | (Singer) Delgat comb. nov. | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 148 | Lf. panuoides | (Singer) De Crop | Singer (1952) | Neotropics |

| 149 | Lf. parvigerardii | X.H. Wang & D. Stubbe | Wang et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 150 | Lf. paulensis | (Singer) Delgat comb. nov. | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 151 | Lf. pectinatus | Maba & Yorou | Maba et al. 2015b | Afrotropics |

| 152 | Lf. pegleri | (Pacioni & Lalli) Delgat | Lalli & Pacioni (1992) | Neotropics |

| 153 | Lf. pelliculatus | (Beeli) Buyck | Buyck (1989) | Afrotropics |

| 154 | Lf. persicinus | Delgat & De Crop | Delgat et al. 2017 | Afrotropics |

| 155 | Lf. petersenii | (Hesler & A.H. Sm.) Stubbe | Hesler & Smith (1979) | Nearctic |

| 156 | Lf. phlebonemus | (R. Heim & Gooss.-Font.) Verbeken | Heim (1955) | Afrotropics |

| 157 | Lf. phlebophyllus | (R. Heim) Buyck | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 158 | Lf. pilosus | (Verbeken, H.T. Le & Lumyong) Verbeken | Le et al. 2007 | Asia |

| 159 | Lf. pinguis | Van de Putte & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 160 | Lf. piperatus | (L.: Fr.) Kuntze | Linnaeus (1753) | Western Palearctic |

| 161 | Lf. pisciodorus | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 162 | Lf. princeps | (Berk.) Kuntze | Berkeley (1852) | Asia |

| 163 | Lf. pruinatus | (Verbeken & Buyck) Verbeken | Verbeken (1998) | Afrotropics |

| 164 | Lf. pseudogymnocarpus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1995) | Afrotropics |

| 165 | Lf. pseudohygrophoroides | H. Lee & Y.W. Lim | Hyde et al. 2017 | Asia |

| 166 | Lf. pseudoluteopus | (X.H. Wang & Verbeken) X.H. Wang | Wang & Verbeken (2006) | Asia |

| 167 | Lf. pseudotorminosus | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 168 | Lf. pseudovolemus | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 169 | Lf. puberulus | (H.A. Wen & J.Z. Ying) Nuytinck | Wen & Ying (2005) | Asia |

| 170 | Lf. pulchrellus | Hampe & Wisitrassameewong | De Crop et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 171 | Lf. pumilus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 172 | Lf. putidus | (Pegler) Verbeken | Pegler & Fiard (1979) | Neotropics |

| 173 | Lf. rajendrae | Uniyal & K. Das | Uniyal et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 174 | Lf. ramipilosus | Verbeken & De Crop | Li et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 175 | Lf. raspei | Verbeken & De Crop | De Crop et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 176 | Lf. reticulatovenosus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2001 | Asia |

| 177 | Lf. robustus | Y. Song, J.B. Zhang & L.H. Qiu | Song et al. 2017 | Asia |

| 178 | Lf. roseolus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 179 | Lf. roseophyllus | (R. Heim) De Crop | Heim (1966) | Asia |

| 180 | Lf. rubiginosus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 181 | Lf. rubrobrunnescens | (Verbeken, E. Horak & Desjardin) Verbeken | Verbeken et al. 2001 | Asia |

| 182 | Lf. rubroviolascens | (R. Heim) Verbeken | Heim (1938) | Afrotropics |

| 183 | Lf. rufomarginatus | (Verbeken & Van Rooij) De Crop | Van Rooij et al. 2003 | Afrotropics |

| 184 | Lf. rugatus | (Kühner & Romagn.) Verbeken | Kühner & Romagnesi (1953) | Western Palearctic |

| 185 | Lf. rupestris | (Wartchow) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Wartchow et al. 2010 | Neotropics |

| 186 | Lf. russula | (Rick) Silva-Filho & Wartchow | Rick (1906) | Neotropics |

| 187 | Lf. russulisporus | Dierickx & De Crop | Dierickx et al. 2019 | Australasia |

| 188 | Lf. ruvubuensis | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 189 | Lf. sainii | Sharma & Atri | Liu et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 190 | Lf. sepiaceus | (McNabb) Stubbe | McNabb (1971) | Australasia |

| 191 | Lf. sesemotani | (Beeli) Buyck | Buyck (1989) | Afrotropics |

| 192 | Lf. sinensis | J.B. Zhang, Y. Song & L.H. Qiu | Song et al. 2018 | Asia |

| 193 | Lf. subclarkeae | (Grgur.) Verbeken | Grgurinovic (1997) | Australasia |

| 194 | Lf. subgerardii | (Hesler & A.H. Sm.) Stubbe | Hesler & Smith (1979) | Nearctic |

| 195 | Lf. subiculatus | S.L. Mill., Aime & T.W. Henkel | Miller et al. 2012 | Neotropics |

| 196 | Lf. subkigomaensis | De Lange & De Crop | De Lange et al. 2018 | Afrotropics |

| 197 | Lf. subpiperatus | (Hongo) Verbeken | Hongo (1964) | Asia |

| 198 | Lf. subpruinosus | X.H. Wang | Wang et al. 2015 | Asia |

| 199 | Lf. subreticulatus | (Singer) Delgat comb. nov. | Singer et al. 1983 | Neotropics |

| 200 | Lf. subtomentosus | (Berk. & Ravenel) Kuntze | Berkeley & Curtis (1859) | Nearctic |

| 201 | Lf. subvellereus | (Peck) Nuytinck | Peck (1898) | Nearctic |

| 202 | Lf. subvolemus | Van de Putte & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2016 | Western Palearctic |

| 203 | Lf. sudanicus | Maba, Yorou & Guelly | Maba et al. 2014 | Afrotropics |

| 204 | Lf. tanzanicus | (Karhula & Verbeken) Verbeken | Karhula et al. 1998 | Afrotropics |

| 205 | Lf. tenuicystidiatus | (X.H. Wang & Verbeken) X.H. Wang | Wang & Verbeken (2006) | Asia |

| 206 | Lf. tropicosinicus | X.H. Wang | Wang et al. 2015 | Asia |

| 207 | Lf. uapacae | (Verbeken & Stubbe) De Crop | Verbeken et al. 2008 | Afrotropics |

| 208 | Lf. umbilicatus | Silva-Filho, D.L. Komura & Wartchow | Silva et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 209 | Lf. umbonatus | K.P.D. Latha & Manim. | Latha et al. 2016 | Asia |

| 210 | Lf. urens | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 211 | Lf. uyedae | (Singer) Verbeken | Singer (1984) | Asia |

| 212 | Lf. vellereus | (Fr.) Kuntze | Fries (1838) | Western Palearctic |

| 213 | Lf. velutissimus | (Verbeken) Verbeken | Verbeken (1996a) | Afrotropics |

| 214 | Lf. venezuelanus | (Dennis) De Crop | Dennis (1970) | Neotropics |

| 215 | Lf. venosellus | Silva-Filho, Sá & Wartchow | Silva et al. 2020 | Neotropics |

| 216 | Lf. venosus | (Verbeken & E. Horak) Verbeken | Verbeken & Horak (2000) | Australasia |

| 217 | Lf. veraecrucis | (Singer) Verbeken | Singer (1973) | Neotropics |

| 218 | Lf. versiformis | Van de Putte, K. Das & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2012 | Asia |

| 219 | Lf. vitellinus | Van de Putte & Verbeken | Van de Putte et al. 2010 | Asia |

| 220 | Lf. volemoides | (Karhula) Verbeken | Karhula et al. 1998 | Afrotropics |

| 221 | Lf. volemus | (Fr.: Fr.) Kuntze | Fries (1838) | Western Palearctic |

| 222 | Lf. waltersii | (Hesler & A.H. Sm.) De Crop | Hesler & Smith (1979) | Nearctic |

| 223 | Lf. wangii | (J.Z. Ying & H.A. Wen) De Crop comb. nov. | Ying & Wen (2005) | Asia |

| 224 | Lf. wirrabara | (Grgur.) Stubbe | Grgurinovic (1997) | Australasia |

| 225 | Lf. xerampelinus | (Karhula & Verbeken) Verbeken | Karhula et al. 1998 | Afrotropics |

| 226 | Lf. zenkeri | (Henn.) Verbeken | Singer (1942) | Afrotropics |

In Russulaceae in general, intercontinental conspecificity appears to be rare. In Lactarius it seems to be more common than in Lactifluus. For example, Nuytinck et al. (2007) reported Lactarius deliciosus to occur in Europe and China, Nuytinck et al. (2010) found L. controversus to be conspecific between Europe and North America, and Wisitrassameewong (2015) reported L. badiosanguineus to occur both in Europe and China. Some records of species occurring on two or more continents are due to the introduction of their host trees in a new continent. For example, L. hepaticus was introduced in Madagascar and South Africa, when European Pinus trees were introduced for cultivation (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010).

Ecology

Species of the genus Lactifluus are found in subtropical and tropical regions and to a lesser extent in temperate areas, in a wide range of vegetation types, including tropical and subtropical rain forests, subtropical dry forests, monsoon forests, tree savannahs, Mediterranean woodlands, temperate broadleaf and coniferous forests and montane forests. Basidiocarps are commonly found on soil, but in tropical habitats with high humidity they are sporadically found on stems or epigeous roots of trees, such as Lf. brunellus on stems of Dicymbe corymbosa (Miller et al. 2002), Lf. multiceps and Lf. raspei on plant seedlings (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Lactifluus species growing on trees or plant seedlings. A. Subiculum of Lf. brunellus on the stem of a tree. B. Lf. multiceps (TH 9807). C. Lf. raspei (EDC 14-517) [Photographs by T. Henkel (A), T. Elliot (B) and E. De Crop (C)].

Lactifluus, Lactarius, Multifurca and Russula species are ectomycorrhizal fungi, while the corticioid Russulaceae taxa are reported to be saprotrophic (Larsson & Larsson 2003, Miller et al. 2006, Tedersoo et al. 2010a). However, the latter is questioned by Miller et al. (2006), who suggest that these corticioid taxa might also be ectomycorrhizal symbionts. Together with Russula, Lactifluus appears to be one of the most dominant ectomycorrhizal genera in the tropics (Tedersoo et al. 2010b, 2011). Host plants for Lactifluus are leguminous trees (Fabaceae), members of the Dipterocarpaceae and the Fagaceae, together with genera from several other families. European and North American Lactifluus species are mainly associated with trees of Betulaceae (e.g. Betula, Carpinus, Corylus), Fagaceae (e.g. Castanea, Fagus, Quercus), Pinaceae (e.g. Abies, Picea, Pinus), and Cistaceae (e.g. Cistus, Halimium) (Hesler & Smith 1979, Heilmann-Clausen et al. 1998, Comandini et al. 2006, Van de Putte 2012, Leonardi et al. 2016, Leonardi et al. 2020). In Asia, Lactifluus species mainly occur with Dipterocarpaceae (e.g. Dipterocarpus, Shorea) and Fagaceae (e.g. Castanopsis, Lithocarpus) (Le 2007, Van de Putte 2012). In sub-Saharan Africa, Lactifluus species often grow with Dipterocarpaceae (e.g. Monotes), Fabaceae (e.g. Afzelia, Berlinia, Brachystegia, Gilbertiodendron, Isoberlinia, Julbernardia), and Phyllanthaceae (e.g. Uapaca) (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010). In Central and South America, Lactifluus species grow with Fabaceae (e.g. Dicymbe), Fagaceae (e.g. Quercus), Nyctaginaceae (e.g. Neea, Guapira), and Polygonaceae (e.g. Coccoloba) (Tedersoo et al. 2010c). In Australasia, Lactifluus species are mainly associated with Myrtaceae (e.g. Eucalyptus and Leptospermum), and Nothofagaceae (e.g. Nothofagus) (McNabb 1971).

Present data suggest that especially generalists occur in Lactifluus, in contrast to Lactarius and Russula where many host specific species are known. It is hard to draw conclusions concerning hosts generalism or specialism in Lactifluus, as studies proving the mycorrhizal association are scarce, but for most Lactifluus species multiple host trees are suggested. Lactifluus volemus, for example, has a broad host range and is known to occur with hosts from both Fagaceae and Pinaceae (Van de Putte et al. 2016). The European Lf. rugatus, that was thought to grow solely with Quercus, is now also known to grow with Cistus in Mediterranean areas (Brotzu 1998, Comandini et al. 2006, Leonardi et al. 2016). The few species that appear to be host specific are so far only known from a few records, such as Lf. madagascariensis that is only known to occur with Uapaca louvellii in Madagascar (Buyck et al. 2007), Lf. corbula found both in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon in monodominant Gilbertiodendron dewevrei plots (Henkel, pers. comm.), or Lf. coccolobae which is only known from Coccoloba uvifera in the sand dunes of the Antilles (Miller et al. 2000).

For most Lactifluus species, the exact ECM connection generally remains undetermined. Ecological characteristics are not commonly recorded for every collection during field work, and it is hard to find out which tree a fungal species grows with in mixed forests. Common techniques to detect the host tree in mixed forests are labour-intensive and expensive, since ectomycorrhizal roots have to be excavated, both fungus and plant need to be sequenced, identified, and herbarium material needs to be collected [e.g. in the study of Osmundson et al. 2007].

Phylogeny and molecular diversity

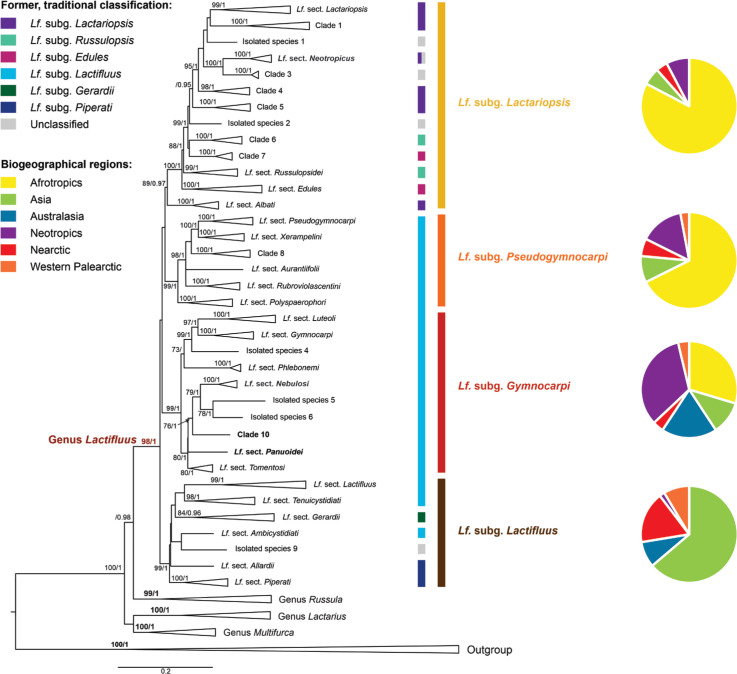

In 2017, De Crop et al. (2017) performed a global study of the genus Lactifluus, which resulted in a new infrageneric classification of the genus. Originally the genus was divided in 6 subgenera, 13 sections and three unclassified species, but De Crop et al. (2017) inferred that the genus could be divided into four subgenera: Lf. subg. Gymnocarpi, Lf. subg. Lactariopsis, Lf. subg. Lactifluus, and Lf. subg. Pseudogymnocarpi (Fig. 7). Each subgenus was further divided into four or more sections, together with undescribed clades and species on isolated positions.

Fig. 7.

Overview Maximum Likelihood tree of the genus Lactifluus, based on concatenated ITS, LSU, RPB2 and RPB1 sequence data, adapted from De Crop et al. (2017). The first column of colour bars represents the former, traditional classification. The second column represents the current classification. Pie charts represent the biogeographical regions in which species of each subgenus occur. Maximum Likelihood bootstrap values > 70 % and Bayesian Inference posterior probabilities > 0.95 are shown. Clade names in bold are names that changed since the publication of De Crop et al. (2017).

The majority of species was combined into Lactifluus in a series of specific papers (Verbeken et al. 2011,Verbeken et al. 2012, Stubbe et al. 2012b), other species were combined in Lactifluus as part of larger studies (De Crop et al. 2017, Delgat et al. 2019, 2020), and the remaining species are combined here (see Taxonomy). Table 1 further gives an overview of the currently described species and the subgeneric classification of all Lactifluus species is given in Supplementary Table S1.

The occurrence of several species complexes and species on long and isolated branches reflects the large genetic diversity as was earlier described by Verbeken & Nuytinck (2013). Several species complexes have been intensively studied and have revealed an enormous diversity. In the complex around Lf. volemus, Van de Putte et al. (2010, 2012, 2016) applied phylogenetic species recognition and discovered about 45 different clades within this group. Some of them could be morphologically distinguished and were described as new species. Others remain cryptic since no morphological differences were found. Stubbe et al. (2010, 2012a) examined the group around Lf. gerardii. At the start of this study, only a handful of species were known, while at the end, more than 30 clades were discovered, of which about two-third are morphologically identifiable species. De Crop et al. (2014) studied the complex of Lf. sect. Piperati. They found 10–20 putative species worldwide, most of them morphological look-a-likes. Recently, Delgat et al. (2019) studied the complex of Lf. sect. Albati and reported 29 species, which had previously been identified as only a handful of species based on morphology. These four former species complexes contain species from a wide geographic range (Asia, Europe, Australasia, and North America), from the temperate regions to the tropics. However, no representatives in South America’s eastern side of the Andes or sub-Saharan Africa are known. Apart from these four species complexes, several other species are assumed to be part of species complexes. These occur on a somewhat smaller scale (one continent). For example, within the African Lf. gymnocarpoides, Lf. pumilus and Lf. longisporus all have similar morphological characteristics and are hard to distinguish in the field. In the Neotropics, the species Lf. annulifer and Lf. venezuelanus are assumed to be part of a species complex (L. sect. Neotropicus). In Australasia, Lf. clarkeae, Lf. flocktonae and Lf. subclarkeae are morphologically rather similar and together with some undescribed clades, they presumably belong to a species complex (unpubl. res.).

Juxtaposed to the species complexes, several Lactifluus species occur on long branches and have isolated positions in the phylogenetic tree; these include Lf. ambicystidiatus from China (Wang et al. 2015), Lf. aurantiifolius from tropical Africa (Verbeken 1996a, Buyck et al. 2007), Lf. cocosmus from Togo (Van de Putte et al. 2009), Lf. chrysocarpus from Vietnam (Morozova et al. 2013), and Lf. foetens from Benin and Togo (Van Rooij et al. 2003, De Crop et al. 2016), and Lf. russula from Brazil (Delgat, unpubl. res.).

Taxonomy

New combinations

Eight species, originally described as Lactarius, need to be recombined in the genus Lactifluus.

Lactifluus adustus (Rick) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832778.

Basionym: Lactarius adustus Rick, Lilloa 2: 304. 1938.

Lactifluus echinatus (Thiers) De Crop, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832779.

Basionym: Lactarius echinatus Thiers, Mycologia 49: 716. 1957.

Lactifluus epitheliosus (Buyck & Courtec.) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832780.

Basionym: Lactarius epitheliosus Buyck & Courtec., Mycologia Helvetica 4: 211. 1991.

Lactifluus ignifluus (Vrinda & C. K. Pradeep) De Crop, comb. nov. MycoBank MB838409.

Basionym: Lactarius ignifluus Vrinda & C. K. Pradeep, Persoonia 18: 129. 2002.

Lactifluus pallidipes (Singer) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832781.

Basionym: Lactarius pallidipes Singer, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 77: 299. 1983.

Lactifluus paulensis (Singer) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832782.

Basionym: Lactarius paulensis Singer, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 77: 305. 1983.

Lactifluus subreticulatus (Singer) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832783.

Basionym: Lactarius subreticulatus Singer, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 77: 314. 1983.

Lactifluus wangii (J.Z. Ying & H.A. Wen) De Crop, comb. nov. MycoBank MB838408.

Basionym: Lactarius wangii J.Z. Ying & H.A. Wen, Mycosystema 24: 156. 2005.

Excluded names

Lactarius subpallidipes appears to be a Russula species, for which a new combination is proposed.

Russula subpallidipes (Singer) Delgat, comb. nov. MycoBank MB832784.

Basionym: Lactarius subpallidipes Singer, Beih. Nova Hedwigia 77: 298. 1983.

Uncertain species/genus status

From one species, Lactarius steffenii, the type material is apparently lost, and this makes it difficult to assess to which milkcap genus this Brazilian species belongs (Silva-Filho & Wartchow 2019).

Belowground diversity

Lactifluus species have been recovered from soil samples in several studies. In the recently published public database GlobalFungi (Vetrovsky et al. 2020, accessed on 28/07/2020) Lactifluus OTUs were found in 343 of the 20 009 sampled sites worldwide (in 498 samples when singletons, i.e. OTU abundance = 1, are included). On a global scale, the study of Tedersoo et al. (2014) have recovered Lactifluus OTU’s from all continents. Other studies concentrate on a specific region within a country (e.g. Tian et al. 2017) or focus on a continent (e.g. Bissett et al. 2016).

Preliminary results (see supplementary Tables S2–S4) of the data (singletons excluded) suggest that these metabarcoding data recovered 18 possible new Lactifluus species. Only 23.8 % of the described species available in our dataset were recovered. If we consider both described species and species that are undescribed but known by our research group, only 16.6 % of the species were found. These low numbers are mainly due to an undersampling of the main distribution areas of Lactifluus, i.e. (sub)tropical Africa, Southeast Asia and South America, for which respectively only 22.7 %, 7.9 % and 6.8 % of the known species were found in soil samples. Furthermore, in order to find Lactifluus, samples need to be taken in proximity of ECM trees, which was mostly not the case.

Comparing the results between continents, different patterns emerge. Twenty-eight of the 240 sampled sites in Africa contained Lactifluus OTUs. Those 28 samples were taken in five regions in sub-Saharan Africa, all with a history of Lactifluus research. Those regions are largely covered by ECM vegetation. Lactifluus is one of the dominant ECM fungal groups present in those vegetation types and this is reflected in the results. In the 28 sampling sites, 22.7 % of the known and described African species and ten possible new lineages were retrieved. These results suggest that with new regions explored, there might still be many new Lactifluus species to be found in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Asian samples were taken all over the continent, however, not always in ECM forest. Thus from the almost 3 000 sampled sites, Lactifluus was found in only 25 sampling sites. This includes 7.9 % of the known or described Asian species and three possible new lineages. This is only a fraction of the currently known Asian diversity.

Due to the BASE project (Bissett et al. 2016), the Australasian region is rather well sampled. Although Lactifluus OTUs were found in only 6 % of the sampled sites, 54.5 % of the known or described Australasian species were found. Ten known species were not retrieved in the soil samples and two more possible new lineages were found.

In absolute numbers, Europe is the best sampled region. However, samples were mainly taken for studies with a focus on specific regions, not covering the whole continent and not necessarily taken in proximity of ECM trees. This is reflected in the results for Lactifluus. Less than 1 % of the sampling sites contains Lactifluus OTUs, and of the nine known and described species, only four were retrieved. Due to the lack of sampling sites in Southern Europe, none of the more Mediterranean species was found. As the European Lactifluus species have been studied in great detail (Heilmann-Clausen et al. 1998, Basso 1999, De Crop et al. 2014, Leonardi et al. 2016, Van de Putte et al. 2016, Delgat et al. 2019, Dierickx et al. 2019b), we did not expect new lineages to emerge, which was indeed the case.

North America also contains a lot of sampled sites, however, again constricted to certain areas. Lactifluus OTUs were found in only 1.4 % of the samples, 27 % of the known species were retrieved in the soil samples, and two possible new lineages were found.

In Central and South America, ECM trees are mostly scattered throughout the forests, which makes it difficult to detect ECM fungi from soil samples. From the 33 sampling sites in which Lactifluus was found, the majority was taken in the forests of Western Guyana where monodominant forests of the ectomycorrhizal Dicymbe corymbosa occur and where Russulaceae have been the focus of a series of studies (Henkel et al. 2000,Henkel et al. 2012, Miller et al. 2002, Miller et al. 2012). However, only 6.8 % of the known or described species was found, and those found were thus only species known to occur in those Dicymbe forests. Only one possible new lineage was found.

Macromorphology

Despite the existence of species complexes, in which morphological diversity is rather limited, the genus Lactifluus generally shows a large diversity of macromorphological characters (Fig. 8), which can often be used for species delimitation.

Fig. 8.

Overview of different types of Lactifluus sporocarps. Lf. subg. Gymnocarpi: A. Lf. nonpiscis (EDC 14-056). B. Lf. tanzanicus (EDC 11-224). C. Lf. gymnocarpus (EDC 12-047). D. Lf. albomembranaceus (EDC 12-046). E. Lf. cf. phlebonemus (EDC 12-067). F. Lf. panuoides. G. Lf. putidus (LD 15-002). H. Lf. clarkeae (REH 9871). Lf. subg. Lactifluus: I. Lf. volemus. J. Lf. longipilus (KVP 08-005). K. Lf. atrovelutinus (DS 06-003). L. Lf. raspei (EDC 14-517). M. Lf. aff. piperatus (DS 07-467). N. Lf. roseophyllus (JN 2011-076). O. Lf. allardii (C.C. 3.0). P. Lf. aff. tenuicystidiatus (DS 07-465). Lf. subg. Lactariopsis: Q. Lactifluus sp. (EDC 11-068). R. Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-091). S. Lf. cyanovirescens (EDC 11-021). T. Lf. multiceps (TH 9807). U. Lf. longipes (EDC 14-049). V. Lactifluus sp. (EDC 12-069). W. Lf. roseolus (EDC 14-228). X. Lf. subvellereus (AV 13-025). Lf. subg. Pseudogymnocarpi: Y. Lf. cf. gymnocarpoides (EDC 14-106). Z. Lf. medusae (EDC 12-152). AA. Lf. luteopus (EDC 14-086). BB. Lf. bicapillus (EDC 12-176). CC. Lf. rubiginosus (EDC 11-067). DD. Lf. armeniacus (EDC-501). EE. Lf. denigricans (EDC 14-067). FF. Lf. pegleri (LD 15-014) [Photographs by E. De Crop (A–E,L,Q–S,U–W,Y–EE), T. Henkel (F), L. Delgat (G,FF), R. Halling (H), G. Boerio (I), K. Van de Putte (J), D. Stubbe (K,M,P), J. Nuytinck (N), D. Molter C.C. 3.0 (O), T. Elliot (T) and A. Verbeken (X)].

A striking first character is the sporocarp type and size. Currently, three different sporocarp types are known in Lactifluus: the agaricoid type (i.e. with cap, gills and centrally attached stipe, e.g. Fig. 8A), the pleurotoid type (i.e. with cap, gills and laterally attached stipe, e.g. Fig. 8L), and the sequestrate sporocarp type (Lebel et al. 2016). Sporocarps of Lactifluus species range from miniscule sporocarps, such as in Lf. igniculus (pileus 5–16 mm diam), to large basidiocarps, such as in Lf. vellereus (pileus 50–300 mm diam.). Most sporocarps grow directly on soil, but tiny agaricoid and pleurotoid species may often grow on a subiculum (Fig. 6), which is an interwoven network of thick-walled hyphae from which sporocarps arise. This subiculum grows on saplings, roots, stems, soil or rocks, and can be intermixed with bryophyte growth and subtended by ectomycorrhizal rootlets. It can be small to very extensive, e.g. the subiculum of Lf. multiceps was recorded to stretch out over 15 m (Miller et al. 2002).

Within the Russulaceae, the genera Lactifluus and Russula are known to contain species with a secondary velum. In Lactifluus, this velum can be present as an annulus around the stipe or as velar remnants on the pileus edge (Fig. 9). The annulus is fibrous, membranous, thin to almost invisible and not mobile, unlike in some Russula species with a mobile annulus which often sticks to the growing cap (Fig. 3C). Species with a secondary velum, together with their closest relatives, are characterised by an involute pileus margin when young. This involute pileus margin can make contact with the stipitipellis and protects the developing lamellae (Heim 1937).

Fig. 9.

Overview of different types of velum in unidentified Lactifluus spp. A. EDC 14-060. B. EDC 14-065. C. EDC 11-127. D. EDC 11-144. E. EDC 14-172. F. EDC 14-059. G. EDC 14-146. H. EDC 14-091. I. EDC 14-051. [Photographs by E. De Crop (A–D, F–I) and J. Nuytinck (E)].

The pileus shape of Lactifluus species varies between applanate, planoconvex, concave, infundibuliform or deeply infundibuliform. Pileus colours range from white, yellow, orange, red to brownish colours. Pileus surfaces range from smooth caps to chamois-leather-like to velvety or woolly (Fig. 10). Some species, especially from Lf. sect. Albati are known for their woolly pileus surface and their local names often refer to this aspect (e.g. Lactifluus vellereus in Dutch: schaapje, in English: fleecy milkcap, in German: Wollige Milchling, Mildmilchender Wollschwamm or Samtiger Milchling, in Spanish: lactario aterciopelado). The pileus margin is often concentrically wrinkled near the edge and can be grooved or involute. The pileus edge is either entire, crenulate or eroded. Stipe colours and surface mainly resemble those of the pileus but are often slightly paler or less felted. The stipe is generally centrally attached and often tapering downwards or curved near the base.

Fig. 10.

Overview of different types of pileus surface in Lactifluus. A. Wrinkled and finely felty pileus of Lf. brunnescens (EDC 12-116). B. Sulcate pileus of Lactifluus sp. – Lf. sect. Lactariopsis (EDC 11-084). C. Finely squamulose pileus of Lf. urens (EDC 14-032). D. Pileus tomentose and cracked into small, felty flocks in Lf. inversus (EDC 12-070). E. Pruinose pileus of Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-153). F. Smooth and somewhat shiny pileus of Lf. cyanovirescens (EDC 11-021) (Photographs by E. De Crop).

Lamellae of Lactifluus species are mostly slightly paler than the pileus, except in some species, e.g. Lf. aurantiifolius with dark yellow-orange lamellae. Lamellae may be thin, almost paper-like, such as in Lf. pelliculatus; or thick and brittle, such as in Lf. rubroviolascens. They may be very broad, as in Lf. sesemotani or narrow, as in Lf. inversus. Some are distant, as in Lf. distantifolius, or very crowded, as in Lf. phlebophyllus (Fig. 11). The attachment to the stipe varies from adnate, adnate with a decurrent tooth to decurrent. Generally, the lamella edge is entire and concolourous with the rest of the lamellae. However in some species, like Lf. bicolor, the lamella edge is concolourous with the pileus or stipe. In almost all Lactifluus species, lamellulae (l) are present between the lamellae (L). These lamellulae often occur in a pattern: L–l–L or L–ls–l–ls–L, with ls the smallest lamellula. Various Lactifluus species have bifurcating lamellae, while others have venation patterns on their lamellae. Venation is either transvenose (when veins occur on the lamella surface) or intervenose (when veins occur between lamellae).

Fig. 11.

Overview of different types of lamellae in Lactifluus. A. Thin and paper-like lamellae of Lf. urens (EDC 14-032). B. Thick and brittle lamellae in Lf. aff. longisporus (EDC 12-199). C. Distant and broad lamellae in Lf. gymnocarpus (EDC 12-055). D. Bifurcating narrow and crowded lamellae in Lf. densifolius (EDC 11-220). E. Lamellae with venation of Lf. persicinus (EDC 12-002). F. Lamellae with coloured edge in Lf. bicolor (DS 06-230) [Photographs by E. De Crop (A–E) and D. Stubbe (F)].

As indicated by their name, Lactifluus species, as Lactarius species, exude latex when bruised. Several latex features have been important in species delimitation in both genera. In Lactifluus, latex can be white, coloured, watery or whey-like and some species have latex changing colour (e.g. blue-green, brown or red-black) after contact with air (Fig. 12). In some species, the latex colours the lamellae and context after exposure to air. Species differ in latex abundance or taste. For instance, in Lf. volemus latex is very abundant and in Lf. piperatus, the latex is very acrid.

Fig. 12.

Overview of different types of latex colourations in Lactifluus. A. Unchanging white latex in Lactifluus sp. (AV 11-089). B. White latex changing greenish in Lf. cyanovirescens (EDC 11-001). C. Unchanging watery white latex in Lf. rubiginosus (EDC 11-067). D. White latex that colours the lamellae brownish in Lf. gymnocarpus (EDC 12-103). E. Brown whey-like latex in Lf. brunnescens (EDC 12-116). F. Watery white latex changing red and later black in Lf. rubroviolascens (EDC 14-384) [Photographs by A. Verbeken (A) and E. De Crop (B–F)].

The context of Lactifluus species ranges from firm to stuffed, to partly hollow, chambered or hollow (Fig. 13). The context of most species is white or cream-coloured and in some species, the context changes colour after exposure to air. The context is mild or has a very acrid taste, such as in Lf. acrissimus or Lf. urens. Some species smell like fish or seafood (Lf. volemus, Lf. nonpiscis), fruit (Lf. edulis, Lf. aureifolius), or coconut (Lf. cocosmus). Some of the typical odours that occur in the genus Lactarius are lacking here, for example the Heteroptera-odour of L. quietus, the odour of curry or camphor of L. camphoratus, or the fenugreek odour of L. helvus. The spore print of all Lactifluus species is white but cannot be used explicitly to delimit Lactifluus species.

Fig. 13.

Overview of different types of context in Lactifluus. A. Firm context in Lf. urens (EDC 14-032). B. Chambered context in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-061). C. Chambered context in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-046). D. Stuffed context in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-512). E. Partly hollow context in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-038). F. Hollow context in Lf. nonpiscis (EDC 14-056) [Scale bar = 1 cm. Line drawings by E. De Crop].

Micromorphology

The genus Lactifluus is known for the occurrence of thick-walled elements in many of its species. For terminology concerning these characters we follow Verbeken & Walleyn (2010).

Structures of the pileipellis and stipitipellis

The structure of the pileipellis is an important character in this genus and is used to delimit species, sections or subgenera. As pileipellis and stipitipellis structures slightly change during their development (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010), pellis structures in this study were observed in mature specimens. Drawings were made using tissue taken halfway along the radius of the pileus or halfway up the stipe height.

For the description of the pellis structures, we follow Heilmann-Clausen et al. (1998) and Verbeken & Walleyn (2010). In Lactifluus, the pileipellis is regularly differentiated from the underlying trama and often consists of two layers, indicated as supra- and subpellis. The most important characters to look at are the presence of thick-walled elements, the presence of isodiametric cells and the orientation of the terminal elements.

Thick-walled elements are present in many Lactifluus species. They may occur as one consistent layer or as scattered hairs in a layer of thin-walled elements. Their presence is indicated with the prefix “lampro” in the name of that pileipellis structure, e.g. lampropalisade.

Many Lactifluus species are characterised by the presence of isodiametric cells, or sphaerocytes, in the subpellis, more rarely in the suprapellis. These are thin- or thick-walled and form one distinct layer or are mixed with cylindrical hyphae.

In case of a distinctly two-layered pileipellis, the suprapellis consists of terminal elements. These are either hair-like elements, hyphae or clavate elements. Their orientation is important in defining the different pellis structures.

The combination of these characters leads to a differentiation between 14 pilei- and stipitipellis types (Fig. 14). Intermediate types sometimes occur.

Fig. 14.

Overview of different pileipellis types found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Cutis in Lf. urens (JR 6002). B. Irregular cutis in Lf. hallingii (FH 18–077). C. Trichoderm in Lf. aurantiifolius (AV 94-063). D. Lamprotrichoderm in Lf. pruinatus (BB 3248). E. Ixotrichoderm in Lf. rufomarginatus (ADK 3011). F. Hyphoepithelium in Lf. piperatus (HP 8475). G. Palisade in Lf. atrovelutinus (DS 06-003). H. Lampropalisade in Lf. oedematopus (RW 1228). I. Hymeniderm in Lf. roseolus (AV 94-064). J. Trichopalisade in Lf. xerampelinus (TS 1116). K. Lamprotrichopalisade in Lf. heimii (AV 94-465). L. Mixed trichopalisade in Lf. indusiatus (AV 94-122). M. Mixed trichopalisade abundant thick-walled elements in Lf. sesemotani (GF 143). [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by A. Verbeken (A, C–F, I–M), L. Delgat (B), D. Stubbe (G) and K. Van de Putte (H)]. Adapted from fig. 1 from De Crop et al. (2017).

Pellis entirely composed of filamentous elements, without isodiametric cells

Cutis: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae, which lay parallel, pericline or are slightly intermixed. Differentiated terminal elements are mostly lacking, although in some species of Lf. sect. Russulopsidei, there are dermatocystidia present in this layer.

Irregular cutis: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae which are irregularly ordered.

Ixocutis: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae which are embedded in a slime layer, which may be produced by hyphae secreting slime or by gelatinized hyphae walls.

Trichoderm: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae, of which the terminal elements are ascending and lay anticline. These hairs often form dense turfs.

Lamprotrichoderm: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae, of which the terminal elements are thick-walled, ascending and lay anticline.

Ixotrichoderm: the suprapellis consists of hyaline, thin-walled hyphae, of which the terminal elements are ascending, lay anticline and are embedded in a slime layer, which may be produced by hyphae secreting slime or by gelatinized hyphae walls.

Pellis with a distinct layer of isodiametric cells

Hyphoepithelium: the suprapellis consists of pericline, hyaline and thin-walled hyphae, which lay on a cellular subpellis.

Palisade: the suprapellis consists of anticline, thin-walled, elongated terminal elements, which lay on a cellular subpellis. The terminal elements are either hair-like or septate.

Lampropalisade: the suprapellis consists of anticline, thick-walled, elongated terminal elements, which lay on a cellular subpellis.

Hymeniderm: the suprapellis consists of anticline, thin-walled, short and clavate terminal elements, which lay on an often thin cellular subpellis.

Pellis with isodiametric cells, but never forming a distinct layer

Trichopalisade: looks like a trichoderm in which some of the anticline hyphae are inflated or rounded, which gives it a palisade-like impression.

Lamprotrichopalisade: as a trichopalisade, but with thick-walled terminal elements.

Mixed trichopalisade: as a trichopalisade, in which some terminal elements are thick-walled.

Mixed trichopalisade with abundant thick-walled elements: as a trichopalisade, in which the majority of terminal elements are thick-walled.

Dermatocystidia rarely occur in the genus Lactifluus. However, they are present in Lf. sect. Russulopsidei and Lf. sect. Piperati, in the upper layer of cutis-like structures or of a hyphoepithelium (Fig. 15).

Fig. 15.

Overview of different types of dermatocystidia found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Lf. ruvubuensis (AV 94-617). B. Lf. longipes (BB 1345). C. Lf. claricolor (R. Heim J18bis) [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by A. Verbeken (A–C)].

Hymenial elements

Basidia and basidioles only slightly differ between closely related species (Fig. 16). Some species have long and slender basidia, such as Lf. albomembranaceus, while others have small and almost clavate basidia, such as Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-061; Fig. 16B). Sterigmata can be short, or long and slender. Most basidia have four sterigmata and form four spores. However, several Lactifluus species also have two- or one-spored basidia, such as Lf. bicapillus (EDC 12-071; Fig. 16D). Basidia are measured excluding sterigmata and their width is measured at the broadest place.

Fig. 16.

Overview of different basidium types found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Long and slender basidia in Lf. albomembranaceus (EDC 12-046). B. Short and clavate basidia in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 14-061). C. Four-spored basidia in Lf. heimii (EDC 11-082). D. One-, two- and four-spored basidia in Lf. bicapillus (EDC 12-071) [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by E. De Crop].

The genus Lactifluus displays different cystidium types. Pseudocystidia, which also occur in Lactarius and some Multifurca species, have no septum and are the extremities of lactiferous hyphae (Fig. 17). Their content therefore resembles the content of lactiferous hyphae, which is refringent, dense, oleiferic or needle-like to granular (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010). In Lactifluus, their abundance and form may vary considerably. In many species of Lf. subg. Pseudogymnocarpi they are scarce, while in many species of Lf. sect. Lactariopsis they are conspicuous and abundant. Pseudocystidia are slender or broad and in some species strongly emergent. Their top is rounded, tapering, moniliform or even forked. Depending on their position on the lamellae, they are called pleuropseudocystidia, when located at the lamella side, or cheilopseudocystidia, when located at the lamella edge.

Fig. 17.

Overview of different pseudocystidium types found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Broad and emergent pseudocystidium in Lactifluus sp. (EDC 12-040). B. Very broad pseudocystidium in Lactifluus sp (EDC 12-030). C. Not emergent pseudocystidia in Lf. cyanovirescens (FN 05-631). D. Narrow pseudocystidium in Lactifluus sp. (JN 2011-071). E. Very narrow pseudocystidium in Lf. cf. phlebonemus (EDC 12-067) [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by E. De Crop (A–C, E) and S. De Wilde (D)].

True pleurocystidia and cheilocystidia also occur. Three different types of true cystidia are known in Lactifluus species (Fig. 18).

Fig. 18.

Overview of different true cystidium types found in the genus Lactifluus. A–D Lamprocystidia. A. In Lf. armeniacus (EDC 14-501). B. In Lf. kigomaensis (AV 11-006). C. In Lf. cf. pumilus (EDC 12-066). D. In Lf. cf. volemus (REH 9320). E–F Macrocystidia. E. In Lf. hallingii (REH 7993). F. In Lf. roseophyllus (JN 2011-076). G–I Leptocystidia. G. In Lf. ruvubuensis (AV 94-599). H. In Lf. indusiatus (AV 94-122). I. In Lf. densifolius (BB 3601) [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by E. De Crop (A–D, F), L. Delgat (E) and A. Verbeken (G–I)]. Adapted from fig. 2 from De Crop et al. (2017).

Lamprocystidia: thick-walled cystidia, which are often very large, frequently emergent to strongly emergent and sometimes septate. Some of the largest lamprocystidia emerge from within the hymenophoral trama, such as in species of Lf. sect. Lactifluus.

Macrocystidia: thin-walled cystidia with a specific content, which is oil-like, needle-like or granular. Their top is rounded, tapering or moniliform.

Leptocystidia: thin-walled cystidia, without a remarkable content, but with a deviating shape. They are rather rare in Lactifluus.

Next to different types of cystidia, some Lactifluus species have sterile elements in their hymenium (Fig. 19). These cells are septate, thin-walled, with no remarkable content and no deviating shape. They are cylindrical and usually ending blunt. Dierickx et al. (2019b) dismiss the idea that these cells represent basidioles or cystidia. They are known to occur in a handful of species (Delgat et al. 2017, De Crop et al. 2019, Dierickx et al. 2019b), but due to their unremarkable shape and content, they might be overlooked and thus more common than currently known.

Fig. 19.

Overview of different types of sterile elements found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Thin-walled, cylindrical, and septate sterile elements, sometimes with clamp-like bulges under the septum, of Lf. bicapillus (EDC 12-169, adapted from De Crop et al. 2019). B. Cylindrical, septate, and slightly thick-walled sterile elements of the hymenium in Lf. persicinus (EDC 14-376, EDC 14-371 and EDC 14-380, adapted from Delgat et al. 2017). [Scale bar = 10 μm].

The lamella edge may contain different elements, such as pseudocystidia, true cystidia, basidioles, basidia, sterile elements or marginal cells. Cheilopseudocystidia, true cystidia and other elements that are present at the lamella edge are often smaller than those on the lamella sides. In several Lactifluus species, the lamella edge is sterile and entirely composed of sterile marginal cells (Fig. 20). These marginal cells are either thin- or thick-walled, hyaline, with a clavate, fusiform to irregular shape (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010).

Fig. 20.

Overview of different marginal cell types found in the genus Lactifluus. A. Lf. russulisporus (REH 9398). B. Lf. armeniacus (EDC 14-501). C. Lf. cf. phlebonemus (EDC 12-067) [Scale bar = 10 μm. Line drawings by E. De Crop (A–C)].

Russulaceae species, together with many species of other Russulales families, are characterised by basidiospores with an amyloid spore ornamentation (Fig. 21). In Lactifluus, the spore ornamentation patterns are important in delimiting species or sections, and range from isolated warts and warts connected with fine connective lines, to a complete reticulum. Spore ornamentation can be very low (<0.1 μm in Lf. indusiatus) to rather high (ridges up to 2.3 μm in Lf. longipilus). The plage (smooth area just above the apiculus) is either inamyloid, centrally amyloid, distantly amyloid or completely amyloid. The length and width of Lactifluus spores are measured in side view, excluding ornamentation. Most Lactifluus spore dimensions fit the following range 6.1–13.4 × 4.8–11.1 μm. Lactifluus carmineus has the longest spores (11.0–13.4 μm long), while Lf. conchatulus has the shortest spores (6.1–7.8 μm long). Lactifluus subvolemus has the broadest spores (7.3–11.1 μm broad), while Lf. foetens has the narrowest spores (4.8–6.5 μm broad). The overall spore shape is determined by the length : width-ratio (quotient or Q-value): globose spores are defined by a Q-value ranging from 1.00–1.05, subglobose spores by Q between 1.06–1.12, ellipsoid spores by Q between 1.13–1.39 and elongate spores by Q >1.39 (Verbeken & Walleyn 2010). The spore shape in Lactifluus species ranges between subglobose to ellipsoid (average Q between 1.10–1.37), only a few species have globose spores, such as in some Lf. oedematopus collections (Q = 1) or elongate spores, such as in some Lf. longisporus collections (Q = 1.6).

Fig. 21.