Abstract

Background

Intimate partner violence (IPV) includes any violence (physical, sexual or psychological/emotional) by a current or former partner. This review reflects the current understanding of IPV as a profoundly gendered issue, perpetrated most often by men against women. IPV may result in substantial physical and mental health impacts for survivors. Women affected by IPV are more likely to have contact with healthcare providers (HCPs) (e.g. nurses, doctors, midwives), even though women often do not disclose the violence. Training HCPs on IPV, including how to respond to survivors of IPV, is an important intervention to improve HCPs' knowledge, attitudes and practice, and subsequently the care and health outcomes for IPV survivors.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of training programmes that seek to improve HCPs' identification of and response to IPV against women, compared to no intervention, wait‐list, placebo or training as usual.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and seven other databases up to June 2020. We also searched two clinical trials registries and relevant websites. In addition, we contacted primary authors of included studies to ask if they knew of any relevant studies not identified in the search. We evaluated the reference lists of all included studies and systematic reviews for inclusion. We applied no restrictions by search dates or language.

Selection criteria

All randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials comparing IPV training or educational programmes for HCPs compared with no training, wait‐list, training as usual, placebo, or a sub‐component of the intervention.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures outlined by Cochrane. Two review authors independently assessed studies for eligibility, undertook data extraction and assessed risks of bias. Where possible, we synthesised the effects of IPV training in a meta‐analysis. Other analyses were synthesised in a narrative manner. We assessed evidence certainty using the GRADE approach.

Main results

We included 19 trials involving 1662 participants. Three‐quarters of all studies were conducted in the USA, with single studies from Australia, Iran, Mexico, Turkey and the Netherlands. Twelve trials compared IPV training versus no training, and seven trials compared the effects of IPV training to training as usual or a sub‐component of the intervention in the comparison group, or both.

Study participants included 618 medical staff/students, 460 nurses/students, 348 dentists/students, 161 counsellors or psychologists/students, 70 midwives and 5 social workers. Studies were heterogeneous and varied across training content delivered, pedagogy and time to follow‐up (immediately post training to 24 months). The risk of bias assessment highlighted unclear reporting across many areas of bias. The GRADE assessment of the studies found that the certainty of the evidence for the primary outcomes was low to very low, with studies often reporting on perceived or self‐reported outcomes rather than actual HCPs' practices or outcomes for women. Eleven of the 19 included studies received some form of research grant funding to complete the research.

Within 12 months post‐intervention, the evidence suggests that compared to no intervention, wait‐list or placebo, IPV training:

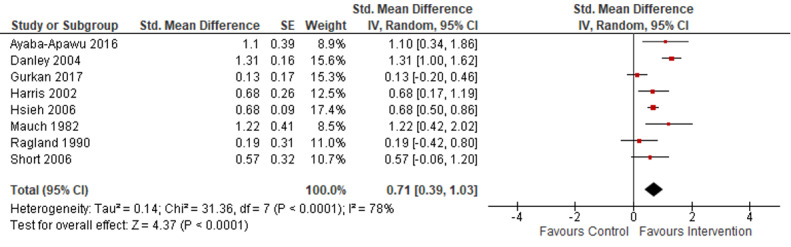

· may improve HCPs' attitudes towards IPV survivors (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.71, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.03; 8 studies, 641 participants; low‐certainty evidence);

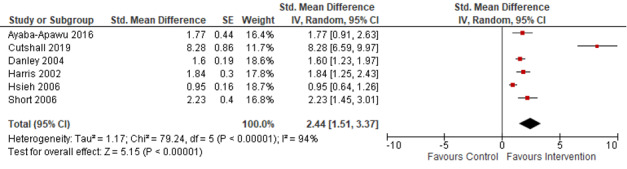

· may have a large effect on HCPs' self‐perceived readiness to respond to IPV survivors, although the evidence was uncertain (SMD 2.44, 95% CI 1.51 to 3.37; 6 studies, 487 participants; very low‐certainty evidence);

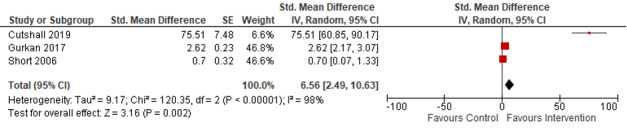

· may have a large effect on HCPs' knowledge of IPV, although the evidence was uncertain (SMD 6.56, 95% CI 2.49 to 10.63; 3 studies, 239 participants; very low‐certainty evidence);

· may make little to no difference to HCPs' referral practices of women to support agencies, although this is based on only one study (with 49 clinics) assessed to be very low certainty;

· has an uncertain effect on HCPs' response behaviours (based on two studies of very low certainty), with one trial (with 27 participants) reporting that trained HCPs were more likely to successfully provide advice on safety planning during their interactions with standardised patients, and the other study (with 49 clinics) reporting no clear impact on safety planning practices;

· may improve identification of IPV at six months post‐training (RR 4.54, 95% CI 2.5 to 8.09) as in one study (with 54 participants), although three studies (with 48 participants) reported little to no effects of training on identification or documentation of IPV, or both.

No studies assessed the impact of training HCPs on the mental health of women survivors of IPV compared to no intervention, wait‐list or placebo.

When IPV training was compared to training as usual or a sub‐component of the intervention, or both, no clear effects were seen on HCPs' attitudes/beliefs, safety planning, and referral to services or mental health outcomes for women. Inconsistent results were seen for HCPs' readiness to respond (improvements in two out of three studies) and HCPs' IPV knowledge (improved in two out of four studies). One study found that IPV training improved HCPs' validation responses.

No adverse IPV‐related events were reported in any of the studies identified in this review.

Authors' conclusions

Overall, IPV training for HCPs may be effective for outcomes that are precursors to behaviour change. There is some, albeit weak evidence that IPV training may improve HCPs' attitudes towards IPV. Training may also improve IPV knowledge and HCPs' self‐perceived readiness to respond to those affected by IPV, although we are not certain about this evidence. Although supportive evidence is weak and inconsistent, training may improve HCPs' actual responses, including the use of safety planning, identification and documentation of IPV in women's case histories. The sustained effect of training on these outcomes beyond 12 months is undetermined. Our confidence in these findings is reduced by the substantial level of heterogeneity across studies and the unclear risk of bias around randomisation and blinding of participants, as well as high risk of bias from attrition in many studies. Further research is needed that overcomes these limitations, as well as assesses the impacts of IPV training on HCPs' behavioral outcomes and the well‐being of women survivors of IPV.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Bias; Dentists; Dentists/education; Health Personnel; Health Personnel/education; Intimate Partner Violence; Medical Staff; Medical Staff/education; Midwifery; Midwifery/education; Nursing Staff; Nursing Staff/education; Psychology; Psychology/education; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Social Workers; Social Workers/education; Students, Health Occupations

Plain language summary

Training healthcare providers to respond to intimate partner violence against women

Review question

Does intimate partner violence (IPV) training for healthcare providers (HCPs) improve their:

· attitudes or beliefs, or both, towards IPV, · readiness to respond to those affected by IPV, · knowledge of IPV, · referral of women being subjected to IPV to specialist services, · actual response to women subjected to IPV (such as validation or safety planning), · identification and documentation of IPV, and · the mental health of survivors of IPV?

Background

Intimate partner violence is associated with a wide range of short‐ and long‐term physical and mental health problems. These include injuries and death, depression, anxiety, post‐traumatic stress disorder, unplanned/unwanted pregnancies and gynaecological problems, to name a few. Health problems can last beyond the duration of the violence and women who have experienced violence are more likely to seek health care compared to women who have never experienced violence.

Women are more likely to trust HCPs with a disclosure of violence. For some women, a healthcare setting may be one of the few places women can attend on their own. HCPs (such as nurses, doctors, midwives, etc.) are therefore ideally situated to identify and provide support for women affected by IPV. Many healthcare settings provide clinical guidelines or training or both on how to identify and respond to IPV. We wanted to find out what difference training makes to IPV‐related HCP attitudes, knowledge and response, including the care provided to women affected by IPV and whether it improved their health outcomes, including their mental health, or made a difference to their exposure to IPV.

Study characteristics

We found 19 trials comparing IPV training to no training, training as usual, or other trainings that were included in this review, with 1662 participants who were practising or student/trainee doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists, social workers and psychologists/counsellors. Three‐quarters of all studies were conducted in the USA, with single studies from Australia, Iran, Mexico, Turkey and the Netherlands. Most studies received some university or government financial support to complete the research.

Studies varied greatly in the kind of IPV training provided, in both content and delivery method. Studies differed in how they measured training outcomes and follow‐up time points. Most IPV training included types and definitions of IPV, prevalence and risk factors, and sought to challenge common myths and misinformation. Clinical scenarios were frequently used as learning tools, outlining typical patient presentations, and skills training involved learning how to ask women about IPV, how to respond by validating their experiences, document accurately, discuss safety planning and refer women to support services.

Key results with an assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Compared to no training, placebo or wait‐list, IPV training may have positive effects on HCPs' attitudes towards survivors of IPV. Training may improve their knowledge around, and readiness to respond to survivors of IPV, but the evidence is very uncertain. There is limited evidence that some types of IPV training can lead to improvements in identification, safety planning and documentation of IPV, but the findings are inconsistent, and most studies report little to no impact of training on these outcomes. Training may make little to no difference to referral practices. No studies with no training, placebo or wait‐list in the comparison group, assessed IPV survivors' mental health outcomes. No adverse effects of IPV training were reported in any of these studies.

The studies that compared training of HCPs to training as usual or a sub‐component of the training typically found no difference in HCPs' attitudes, safety planning, and referral to services or mental health outcomes for women. The evidence was inconsistent about provider readiness to respond, their actual response and changes in IPV knowledge.

Overall, the certainty of the evidence for the effectiveness of training HCPs in how to respond to IPV is low to very low. Future research should include higher‐quality trials, with greater clarity of methods that objectively measure outcomes (actual rather than perceived), with an emphasis on behaviour change in HCPs, and the well‐being of women survivors of IPV.

Up‐to‐dateness of the review

The evidence is current to June 2020.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Training to respond to intimate partner violence compared to no intervention, wait‐list or placebo on healthcare providers' attitudes towards, knowledge of and readiness to manage IPV, referrals for and response to IPV.

| Training to respond to intimate partner violence compared to no intervention, wait‐list, placebo in healthcare providers at less than 12 months after intervention | ||||||

|

Patient or population: physicians/doctors, medical staff, medical students, residents, nurses and nursing students, dentists and dental students, counsellors and psychology students

Setting: teaching and clinical practice settings such as universities, primary care clinics, clinical teaching hospitals/schools and online platforms Intervention: training to respond to intimate partner violence Comparison: no intervention, wait list, or placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with no intervention, wait list, or /placebo | Risk with training to respond to intimate partner violence | |||||

| Healthcare providers’ attitudes/beliefs towards IPV Assessed with: Attitude Toward Battered Women Questionnaire; PREMIS‐ victim blaming or opinion subscale; Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy, etc. | ‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 0.71 standard deviations higher (0.39 higher to 1.03 higher) | ‐ | 641 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Higher scores indicate improved attitudes towards addressing IPV and helping IPV survivors. Training probably improves healthcare providers' (HCPs') attitudes towards survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV). The effect of training appears to be moderate. |

| Healthcare providers’ readiness to respond to/manage survivors of IPV Assessed with: self‐efficacy or perceived preparation subscale of the PREMIS; intended AVDR subscale of the subscale of the Domestic Violence Assessment Instrument | ‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 2.44standard deviations higher (1.51 higher to 3.37 higher) | ‐ | 487 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowb,c,d | Higher scores indicate improved readiness to respond to IPV and helping IPV survivors. Training probably improves healthcare providers' readiness to respond to survivors of IPV. The effect appears to be large. A quasi‐RCT with 136 medical residents (and high risk of bias) did not provide data in a way that could be combined in the meta‐analysis. The authors report that compared to the control group, there was a statistically significant improvement from baseline to post‐training (P < 0.001) in HCPs' ability to explain correct interventions for survivors of IPV. |

| Healthcare providers knowledge or awareness about IPV Assessed with: Knowledge Test About Violence Against Women and the actual knowledge sub scale of the PREMIS | ‐ | The mean score in the intervention groups was 6.56standard deviations higher (2.49 higher to 10.63 higher) | ‐ | 239 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowe,f,g | Higher scores indicate improved knowledge of IPV. Training probably improves healthcare providers' knowledge of IPV. The effect of the intervention is large. 2 other studies provided further support that training may improve HCPs' knowledge of IPV. 1 study with 23 medical residents compared change in percent of correct answers on 5 knowledge questions and report that the experimental group scored 17% more on average than the control group (P < 0.002). The risk of bias in this study was unclear. Another with 30 graduate students pursuing a counselling degree reported a Cohen's d of 0.42, indicating a medium effect of training on IPV knowledge. The risk of bias in this study was low. |

| Referrals made to support agencies, social workers or other specialised services Assessed with: a standardised researcher‐created checklist on office practices | 1 study reported on the referral practices of offices where intervention‐arm HCPs were based compared to referral practices of offices where the control‐arm HCPs were based. The study authors report that no difference in referral practices were seen between the 2 clusters. Physician referral rates were not measured. The study had a high risk of bias due to high and unequal attrition. | ‐ | 49 (1 RCT) | ‐ | ‐ | |

| Provider response to IPV: safety planning, counselling and validation of survivors’ feelings Assessed with: standardised patient reports of HCPs practicing at least 6 out of 8 on common safety planning items | Study population | RR 3.07 (0.96 to 9.77) | 29 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Verylowg,h | Based on the 1 study reported here, we cannot conclude if training could improve healthcare providers' response to survivors of IPV. 1 other study, a cluster‐RCT, compared differences in self‐reported safety planning at the practice level. The authors report little to no difference in self‐reported safety planning between practices. The study had a high risk of bias due to high and unequal attrition. |

|

| 231 per 1000 | 571 per 1000 (238 to 851) | |||||

| Adverse outcomes | Not reported | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No data on harms are available | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

AVDR: Ask, Validate, Document and Refer; CI: confidence interval; HCP: Healthcare Provider; IPV: intimate partner violence; PREMIS: Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. We interpreted the SMD using Cohen’s D, where we treated an SMD of about 0.2 as a small effect, an SMD of about 0.5 as a moderate effect, and a SMD of more than 0.8 as a large effect (Cohen 1977) | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

aDowngraded one level for study limitations owing to unclear risk of bias from lack of blinding in all studies, high risk of bias from high and unequal attrition and lack of standardised tools in some studies, and high risk of bias due to lack of random sequence generation in one study. bDowngraded one level owing to inconsistency (heterogeneity in intervention and statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 75% and significant Chi2 test of heterogeneity has a low value and wide variance in point estimates across studies). cDowngraded one level for study limitations owing to unclear or high risk of bias from lack of blinding in all studies, high risk of bias from high and unequal attrition and lack of standardised tools in some studies. dDowngraded one level owing to indirectness (with respect to population and setting as only dentists, mental health professionals and graduate students and physicians were represented, and all the training took place online). eDowngraded one level owing to high risk of bias from high and unequal attrition in two out of three studies in the meta‐analysis, and high risk of bias due to lack of random sequence generation in one study. fDowngraded one level owing to indirectness (with respect to population and setting as only general practitioners/community physicians and nursing and counselling students were represented, and the training took place in university settings or online). gDowngraded two levels owing to imprecision. CIs are wide and clustering of events within individuals does not seem to be accounted for. Small sample sizes may be further contributing to this imprecision. hDowngraded one level owing to indirectness (with respect to population and setting, as GRADE criteria was only applied to one study).

Background

Description of the condition

Intimate partner violence (IPV) against women includes any violence (physical, sexual or psychological/emotional) or threats of such violence by a partner or a former partner, and is hereafter referred to as IPV or partner violence. In this Cochrane Review, we use the overarching definition of Heise 2002 (p 89), that refers to IPV as "any behaviour within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship". Prevalence estimates based on data from 2000 to 2018 recently published by the World Health Organization (WHO) show that globally 27% of women and girls aged 15 to 49 years have been subjected to physical or sexual IPV or both in their lifetime (WHO 2021).

In addition to fatal (Stöckl 2013) and non‐fatal physical injuries that are a direct result of the inflicted violence, IPV that may involve psychological and sexual violence has been linked to a wide range of negative health outcomes, disorders or conditions such as sexually‐transmitted infections, HIV, unwanted and unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, gastrointestinal and gynaecological disorders, chronic diseases, harmful substance use, depression, post‐traumatic stress and other anxiety disorders, and other somatoform conditions (Campbell 2002; Coker 2002; WHO 2013a). Partner violence survivors are more likely to seek health care and to interact with healthcare providers (HCPs) than those who have not been exposed to IPV (WHO 2013b).

Healthcare providers are often a first point of call for women and are among those professionals they are most likely to trust with a disclosure (Feder 2006; Tarzia 2020). An empathetic well‐trained provider can validate women's experiences and help women access the support they need, often by connecting them with specialised services. Healthcare providers are in an ideal position to identify and provide care and support for women who have been victims of IPV, by linking them to other services, and potentially contributing to a reduction in violence and improved outcomes for women and their children (Aksan 2007; Bullock 1997; Garcia‐Moreno 2002; Garcia‐Moreno 2014; Kim 2002; Short 1998; WHO 2014). Healthcare providers can also play a central role in collecting and documenting evidence necessary for identification and legal action against the perpetrator of the violence (WHO 2013b). Furthermore, the healthcare sector presents a potential pathway to other services that survivors may need, including but not limited to, legal aid, social welfare or psychosocial support, and community resources targeted at addressing the needs of IPV survivors (WHO 2013b; WHO 2014). Healthcare providers may also be in a position to provide support to children exposed to violence within their families (Garcia‐Moreno 2014).

Despite widespread agreement on the role that HCPs can play in addressing IPV, many barriers can inhibit HCPs from adequately identifying and responding to women experiencing violence. Intimate partner violence training for HCPs could help overcome HCP‐related barriers to caring for women experiencing IPV. Tolerance for violence against women can result in low reporting rates of IPV. In some cultures, HCPs' attitudes towards violence against women and beliefs that place the responsibility for violence on the victim, act as a barrier to understanding that IPV is an issue that they need to address and provide appropriate care (Aksan 2007; Wood 1998; Zakar 2011). In addition, a HCP's own experience of violence can affect their ability to respond supportively to women experiencing IPV (Aksan 2007). A primary barrier to asking about IPV includes the belief (of HCPs) that by asking about IPV, HCPs will enter a personal and complex situation that they are unprepared to handle, due to inadequate training (Beynon 2012; Davidson 2001; Djikanovic 2010). Asking all women about IPV may increase identification by HCPs, although it has not been demonstrated to increase referrals by HCPs or uptake by women of support services, something that may be explained by an absence of adequate training in responding to IPV (O'Doherty 2015). Furthermore, it has been suggested that HCPs who lack adequate training in enquiring about and responding to IPV can cause harm; perhaps by advocating women leave an abusive relationship while failing to provide survivors with a safety plan or to take into account the survivor's perspective (Morse 2012). Responses like this may leave IPV survivors feeling helpless, guilty, isolated and at risk of further violence (Djikanovic 2010).

Training and education of HCPs in IPV is an important means of addressing several of these barriers and may lead to enhanced care and better health outcomes for survivors of IPV. In addition to these aspects and given the significant cost of IPV to a woman's family, community and society more broadly, HCP training has been proposed to be a cost‐effective and cost‐saving intervention from a societal perspective (Devine 2012). In this context, it is essential to evaluate the impact of training HCPs in how to respond to IPV against women, and to identify the characteristics of successful training interventions.

Description of the intervention

Training programmes should aim to increase HCPs' understanding and skill set related to providing care for women experiencing IPV. Training should provide HCPs with the knowledge and skills they need to investigate and respond appropriately to women experiencing IPV, including ensuring the safety and confidentiality of survivors (Garcia‐Moreno 2002; Garcia‐Moreno 2014). Training programmes examined in this review involve structured training that aimed to increase HCPs' knowledge about IPV (while targeting their existing beliefs and attitudes towards IPV) and aimed to improve the ability of HCPs to respond appropriately to survivors of IPV. Effective responses include knowledge of when and how to ask about violence, empathetic listening, validation of survivors' feelings, discussions around the violence and survivors’ readiness for change, first‐line psychological support, encouragement of safety‐promoting behaviours for IPV survivors, and identification and reporting of the violence, with improved documentation as well as referral of survivors of IPV to specialist agencies where they exist (Bair‐Merritt 2014; WHO 2014).

Training of HCPs in how they should respond to survivors of IPV was a central component of the structured interventions in this review. We considered any training intervention method and pedagogy. Some interventions explicitly identify themselves as based on AVDR (Asking, Validating, Documenting and Referral; Gerbert 2000). These typically listed the following four aspects of training:

Asking: routinely asking patients about partner violence, which should be done in a private setting, while ensuring confidentiality, and using a non‐judgemental and empathetic tone;

Validating: providing validating messages and compassionate statements that acknowledge that IPV is wrong, while confirming the worth of the woman;

Documenting: accurately documenting signs, symptoms and exact words of disclosures in writing or with photographs, or both; and

Making referrals: referring victims to social workers on‐site or to IPV advocates, or other relevant resources within the community.

Other programmes may identify this process as RADAR, which refers to Routine screening, Ask direct questions, Document your findings, Assess patient safety and Review patient options and referrals (Harwell 1998). This intervention typically involves three to six hours of trauma theory‐based training in IPV; it includes sessions with representatives of domestic violence (DV) agencies in the community, and has a similar aim of improving HCPs' ability to document IPV and carry out safety assessments and referrals for IPV survivors. Other studies have provided training on use of resource books and initiation of referrals in response to reporting of IPV on a screening form (Garg 2007). Still others have used computer‐assisted training, electronic reminders or practice "domestic violence advocates" (Feder 2011, p 1). Overall, a central component of the interventions involved training of HCPs in how to identify and respond to survivors of IPV.

Despite the focus on training HCPs on how to respond to survivors of IPV, there is noticeable variation in content, structure and duration of programmes. Training interventions use a wide variety of pedagogical techniques, including role‐plays, group discussions, lectures, experiential training and simulations, among others. They are delivered through a variety of methods, such as workshops, classroom‐based face‐to‐face teaching, online learning and seminars.

Training is sometimes tailored to accommodate the scenario in which HCPs encounter patients, for example, providers working in emergency services may be approached when survivors are seeking orders of protection (Morse 2012), and dentists are in a position to come across facial injuries that can be markers of IPV in women (Ochs 1996; Perciaccante 1999). Where available, the review extracts data on the method of delivery, pedagogical technique, content, frequency, duration, and intensity of the training intervention.

How the intervention might work

Increasing HCPs' awareness of the links between IPV exposure and presenting health issues (physical injury, medically unexplained symptoms, chronic health problems, ongoing mental health problems, etc.) may enhance provider self‐efficacy and understanding of the need to support patients with presenting complaints. Physicians who are trained in IPV during their residency, or who have received continuing education on IPV after licensing, are more likely to ask questions routinely and to identify victims of IPV (Sitterding 2003). Training interventions address HCPs' concerns about the lack of information on how to ask, and how to respond after identification, which is often a barrier to asking about and responding to IPV (Beynon 2012; Davidson 2001; Djikanovic 2010). Training interventions should go beyond addressing these barriers and should attempt to improve HCPs' knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviours related to caring for survivors of IPV. The theory of planned behaviour change (Azjen 1991) posits that behaviours are influenced mainly by an individual’s attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control, and that changes in these can lead to a successful change in the intended behaviour. Training interventions may influence beliefs around IPV that can lead to a change in attitudes towards IPV; may influence subjective norms around responding to IPV; and may increase knowledge of, and provide skills on, how to respond to IPV, thereby changing perceived behavioural control. Thus, changes in HCPs' knowledge and attitudes towards IPV may impact their behaviours/responses to women's disclosure, which in turn may affect the well‐being of IPV survivors. Being supported by a health system that provides ongoing HCP education and clinical support may enhance provider readiness to address IPV (Hegarty 2020; WHO 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

A recent systematic review (O'Doherty 2015) found that even though screening for IPV by healthcare providers can lead to increased identification of victims, overwhelming evidence shows that IPV screening does not increase the number of IPV survivors referred to specialist agencies. Encouraging disclosure of IPV and failing to respond adequately can threaten women's safety and weaken their confidence (Heron 2002). Many HCPs acknowledge that addressing IPV falls within the purview of their professional responsibility (Richardson 2001), although a lack of training on what to do following identification or disclosure remains a barrier to asking about IPV in the first place (Beynon 2012; Djikanovic 2010). Adequate training in both identification of and response to IPV disclosure may address this risk. However, even providers who have received training in IPV continue to feel underprepared to respond to survivors of IPV (Cohen 2002). It is therefore important to identify how to ensure that training in IPV improves identification/disclosure and HCPs' response, and then in turn women's health and well‐being outcomes. In this review we aimed to identify the characteristics of an effective training intervention that can successfully address the needs of HCPs and the women they care for.

No previous Cochrane Review has examined training interventions for HCPs on how to respond to IPV. O'Doherty 2015 assessed the impact of screening, not the impact of training providers in screening and responding. Note that studies in which the intervention group receives a screening tool, and the control group does not, fall outside the purview of this review. Previous systematic reviews on the topic of training are more than a decade old (Davidson 2001; Ramsay 2005). They included observational studies, as well as randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs. The authors of these reviews concluded that overall no conclusive evidence showed the impact of IPV training or education on HCPs or on women survivors of IPV (Davidson 2001; Garcia‐Moreno 2002). Since that time, many studies have evaluated the impact of training HCPs in IPV. A systematic review conducted in 2011 as part of the background research for WHO guidelines on the health sectors' response towards interpersonal violence towards women (WHO 2013b), identified several new studies. This review did not include studies published before the year 2000, did not have a stringent inclusion criterion that was limited to only IPV training programmes, and did not adequately identify and include studies that were written in languages other than English.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of training programmes that seek to improve HCPs' identification of and response to IPV against women, compared to no intervention, wait‐list, placebo or usual care.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials and quasi‐RCTs (in which allocation is not truly random, for example, by date of birth, day of the week, alternate person).

Types of participants

All healthcare providers (HCPs) and HCP students (i.e. doctors, nurses, midwives, dentists, community health workers, medical social workers, dieticians, nutritionists, medical students or residents/fellows, healthcare assistants, paramedics, etc.) in any kind of healthcare setting (primary, secondary, tertiary or community setting), who directly provide health services. This review excluded studies of health professionals who are not direct providers of health care, such as hospital administrative staff and medical and health service managers.

Types of interventions

Any structured programme of (in‐service) training, including experiential training, workshops and educational programmes and sessions, delivered in‐person or virtually, in which the central component is aimed at improving HCPs' ability to identify and respond to IPV against women aged 16 years and older.

We excluded studies:

that addressed only screening for or identification of IPV, as these have been covered elsewhere (O'Doherty 2015);

that addressed training where the focus was on multiple types of violence, including rape and child abuse, and researchers did not specify that they included IPV; and

of training and educational interventions dealing with domestic violence (DV) that was not perpetrated by a partner or directed towards women in a current or past intimate relationship.

Comparisons

No training, wait‐list or placebo.

Training as usual (also referred to as 'treatment and usual' or 'usual care').

A sub‐component of the multi‐component intervention in the intervention arm. For example, the intervention arm includes component A + component B, compared to component B alone in the comparator arm, so as to allow the effect of component A to be assessed.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Healthcare providers’ attitudes/beliefs towards IPV, measured on a scale such as the Domestic Violence Assessment Instrument (Danley 2004) or similar tools used by study authors.

Healthcare providers’ readiness to manage/respond to or support women survivors of IPV, measured on a scale such as the Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate partner violence Survey (PREMIS; Short 2006a) or similar tools.

Healthcare providers’ knowledge or awareness of IPV, measured on a scale such as the PREMIS (Short 2006a) or similar tools.

Referrals made to support agencies, social workers or other specialised services. These could have been self‐reported or documented by HCPs or by women survivors (or both) from medical records, or complete referrals measured by the use of referred services from the records of social workers or family/DV services.

Provider response to IPV: safety planning, counselling or validation of survivors' feelings, or both. This could have been assessed by means of self‐report or documented by HCPs or by women survivors (or both) from medical records.

Adverse outcomes for providers that may have included worsened attitudes, beliefs towards IPV or reduced readiness to manage IPV.

Secondary outcomes

Documentation or identification of IPV (or both) as part of routine data. This could have been self‐reported or documented by HCPs or by women survivors (or both) from medical records.

Mental health outcomes for women survivors of IPV. Depression measured by a standardised instrument such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ; Goldberg 1979), the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Murray 1990) or the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1974). Anxiety measured by a standardised instrument such as Spielberger’s State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger 1994), or similar tools used by study authors.

Adverse outcomes such as IPV‐related death, measured by medical records or vital data records (such as death certificate), or recurrence of IPV or injury after disclosure to a HCP, measured by standardised instruments such as the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS; Hegarty 1999; Hegarty 2005), the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CST2; Straus 1996) or the Women's Experience of Battering (WEB) scale (Smith 1999) or similar tools used by authors.

Search methods for identification of studies

We ran the first searches in April 2017 and ran top‐up searches in April 2019 and June 2020. We did not limit our searches by date or language but used a study methods filter, when appropriate, to identify RCTs and quasi‐RCTs (Lefebvre 2021).

Electronic searches

We searched the electronic databases and trials registers listed below from inception onwards:

Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CENTRAL) (crso.cochrane.org/, searched 2 June 2020)

MEDLINE Ovid (1946 to May Week 4 2020)

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations Ovid (searched 2 June 2020)

MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print Ovid (searched 2 June 2020)

Embase Ovid (1974 to 1 June 2020)

ERIC EBSCOhost (1966 to 2 June 2020)

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus EBSCO); 1937 to 2 June 2020)

PsycINFO Ovid (1806 to May Week 4 2020)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 6 2020; searched 2 June 2020)

Popline (Population Information Online; www.popline.org; searched 3 May 2019. This database service retired on 1 September 2019)

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS); lilacs.bvsalud.org/en; searched 2 June 2020)

African Index Medicus (AIM; indexmedicus.afro.who.int; searched 3 May 2019, service unavailable in June 2020)

World Health Organization Library and Information Networks for Knowledge (WHOLIS; www.who.int/en; searched 3 May 2019; service unavailable in June 2020)

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP; apps.who.int/trialsearch; searched 3 May 2019, service unavailable in June 2020. Message on website 'Due to heavy traffic generated by the COVID‐19 outbreak, the ICTRP Search Portal is not responding from outside WHO temporarily')

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov; searched 2 June 2020)

The search strategies used for each database are reported in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We searched the resources listed below, to identify any additional studies.

Websites

We searched the following websites.

World Bank (www.worldbank.org; searched on 14 August 2018);

Violence Prevention (Centre for Public Health, Liverpool John Moores University; www.preventviolence.info; searched on 15 June 2019);

International Council of Nurses (ICN; www.icn.ch; searched on 15 June 2019);

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (www.cdc.gov/injury; searched on 15 June 2019);

Centre for Public Health (cph.org.uk/expertise/violence) redirected to (www.ljmu.ac.uk/research/centres-and-institutes/public-health-institute; searched on 15 June 2019).

Reference lists

We searched the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews and all included studies.

Personal communication

We contacted the authors of included studies and other experts in the field to ask for details of any published or unpublished studies not identified by our searches or when we needed additional information to determine whether to include/exclude a study.

Data collection and analysis

In the following sections, we report only the methods that are used in the review. For methods that we had planned to use (Kalra 2017), readers are directed to Appendix 2 and the section on Differences between protocol and review.

Selection of studies

In line with the Cochrane Handbook (Higgiins 2021), two review authors (NK and LH or SR) independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to titles and abstracts and full reports and resolved conflicts with the help of the third review author (LH or SR). For studies that were not excluded or when we had insufficient information to decide whether they met the inclusion criteria, we obtained full reports based on their abstract (Criteria for considering studies for this review). Two review authors (NK and LH or SR) reapplied the exclusion criteria to full reports and excluded from the review those that did not meet these criteria. The review team translated non‐English abstracts and full texts of studies where necessary, using Google Translate.

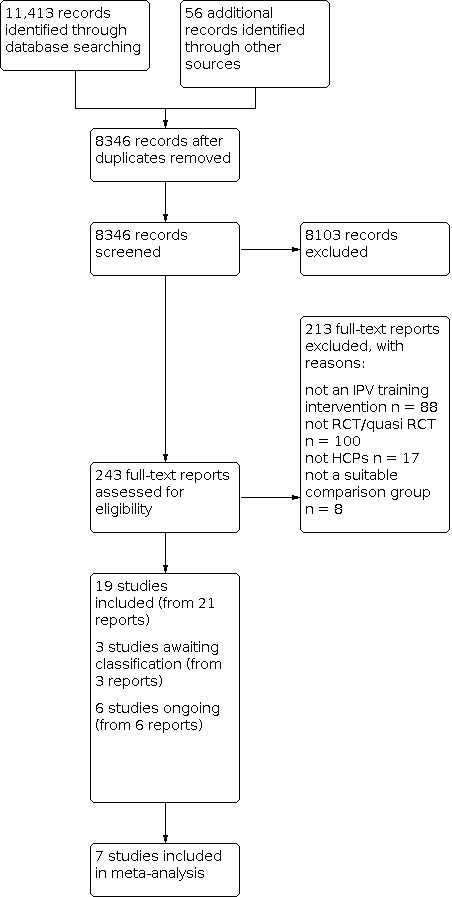

We describe the flow of studies by using a PRISMA flow chart (Moher 2009) (see Figure 1: PRISMA: Flow of studies diagram).

Data extraction and management

One member of the review team (NK and LH or SR) independently extracted descriptive details from full reports, and a second review author (LH, SR or NK) confirmed them. Review authors used a specially‐designed data collection form that was initially piloted and revised to ensure that relevant details were consistently collected from the full reports. We resolved conflicts in data extraction with the help of the third review author (LH or SR). We extracted data related to study population, design, intervention, randomisation methods, blinding, sample size, attrition and handling of missing data, other potential risks of bias, outcome measures, follow‐up duration and methods of analysis. We also extracted data specifying characteristics of the intervention and controls, such as content of the curriculum (e.g. Did it include addressing attitudes? Did it focus on providing counselling and psychological response training? Was it focused on skills like AVDR or identification only, duration and frequency, setting, training method and delivery mode?). We documented contextual factors and equity considerations when the information was available. For outcomes that were ambiguous or that were reported only in graphical form, we contacted the study authors for additional details.

We entered and managed extracted data on electronic data collection forms created in EPPI Reviewer software, version 4.0 (EPPI‐Reviewer 2010).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011), two review authors (NK and LH or SR) independently assessed the risks of bias as low risk, high risk, or unclear risk for each included study across the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcomes, selective reporting, and other. More details of how risk of bias was assessed are in Appendix 3. We resolved disagreements through discussion and consultation with the third review author (SR or LH) as necessary.

We summarised the risk of bias for each study across domains. We present the results for each included study in a risk of bias table under the Characteristics of included studies and in a summary table and graph (Figure 2).

Measures of treatment effect

Binary data

For one study, which we report in Table 1, an odds ratio (OR) was provided. We used the data that were reported in that study to calculate the risk ratio (RR), which we report in the table.

Continuous outcome data

For continuous outcomes, we extract and pool differences of endpoint minus baseline values (meta‐analysis of difference‐in‐differences, which removes the component of between‐person variability from the analysis). When one study failed to report this information, we used and pooled the change score provided by the study. We entered outcome data on means, standard deviations and number of participants in each arm into an Excel sheet and into EPPI‐Reviewer 2010. As different scales were used to measure the same outcome, we synthesised results using the standardised mean difference (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals in random‐effects (DerSimonian 1986) models using Stata 16 software (Stata 2019) and Review Manager 2020, where the data permitted such a synthesis. In line with the specification in our protocol, we also report a fixed‐effect (Inverse variance) model for each meta‐analysis. However, due to the heterogeneity across trials and large Tau2 values, we consider the random‐effects model results to be our primary meta‐analysis results. We interpreted the SMD using Cohen’s D, whereby we interpreted about 0.2 as a small effect, an SMD of about 0.5 as a moderate effect, and a SMD of more than 0.8 as a large effect (Cohen 1977; Cohen 1988).

Multiple outcomes

If a study used more than one measure of the same outcome, we did not double‐count the data and gave preference to outcomes from a standardised scale.

Endpoint versus change scores

For continuous outcomes, we extracted and pooled differences of endpoint minus baseline values, where the latter were reported. If only change scores were available from the primary studies, we used these and relied on the assumption of good balance across the two arms at baseline.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐RCTs

In the case of cluster‐RCTs, we assessed if the study authors had taken clustering into account in the data analyses. When an individual study had failed to conduct and report the proper analysis, we looked for the intra‐cluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) and found that these were not available in the studies where clustering had not been taken into account. In the absence of an ICC to borrow from other studies, we used the approach suggested by McKenzie 2016, that involves inflating the standard error of the estimated intervention effect (rather than reducing the sample size). This approach requires the calculation of a design effect, and therefore an estimate of the ICC. The adjustment is computed by multiplying the standard error by the square root of the design effect. The design effect can be calculated as 1+(M‐1)*ICC (where M is the mean cluster size). We explored some simulated examples using various combinations of M and the ICC. The 10% inflation is based on an M value of around 10 and ICC of 0.025 whilst the 30% inflation uses a very conservative value of ICC of 0.1. In the absence of a reliable estimate of the design effect, we conducted sensitivity analyses with and without inflating the standard errors (SEs) by 10% and 30% (Sensitivity analysis). In the meta‐analyses, we used the SE inflated by 10% for studies that did not correct for the ICC.

Multi‐arm trials

When a study involved more than one treatment group, including different individuals relevant to the review, we reported the multiple interventions in a narrative manner and used only the treatment group that was most compatible with the other interventions in the meta‐analysis. We retained the treatment arm with intervention components that were most similar to the treatment in other studies.

Dealing with missing data

We report on the extent and nature of missing data in the Risk of bias in included studies tables.

For each outcome, we extracted and reported potential reasons for missing data, where reported, how the missing data were handled (ignored, last observation carried forward (LOCF), statistical modelling, etc.), if specified, and the impact of missingness on review results. We also assessed and reported the risk of bias due to selective reporting of outcomes and attrition for each study. We contacted study authors for any unreported data. We ran a complete‐case analysis (by pooling only available data) on the assumption that the missing data are the same as the observed data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Clinical heterogeneity

Although we had hoped to assess all studies together, we expected variation in studies due to type of provider, type of intervention (content of training, training technique, intensity and duration of intervention), and outcome measurement. Clinical diversity introduced by variation in the type of provider may be negligible to answer our overall question about all HCPs; however, clinical diversity in the type of training may need further exploration through subgroup analysis. Given this, we critically assessed the extent of this heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses (see section on Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Statistical heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity in statistical effects in each meta‐analysis by using the I2 statistic and evaluating the Chi2 test of homogeneity (Deeks 2021).

The Chi2 test has low power with few studies and small sample sizes, so although a statistically significant result may indicate some level of heterogeneity across studies, a non‐significant result does not indicate homogeneity. For this reason, we considered probability values less than 0.10 as statistically significant. Along with the Chi2 test, we quantified inconsistency of results through the I2 statistic, which is the proportion of variability in the effect of estimates due to heterogeneity, rather than to chance alone.

We performed both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models; with the latter, we provided an estimate of between‐study variance (Tau2).

Assessment of reporting biases

We graphically displayed funnel plots to assess asymmetry and investigate small‐study effects and other possible reasons (e.g. publication bias) for asymmetry.

Data synthesis

We present a narrative overview of intervention characteristics and findings.

We pooled results only when we expected minimal clinical heterogeneity (i.e. in the intervention, population and outcomes) between studies. We conducted a separate analysis of each outcome assessed at less than one year, at one to two years, and beyond two years. We conducted the meta‐analysis using the statistical software Stata 16 (Stata 2019). The main commands used were metan (for the meta analysis) and metafunnel (for the funnel plots).

When we detected substantial statistical heterogeneity (i.e. if the I2 value was greater than 50%), we used a random‐effects model to account for the heterogeneity. We reported and commented on the results of the model that was more relevant (random‐effects model where heterogeneity is formally incorporated into the pooled estimates) in our main results. However, in line with our protocol, we used both random‐effects (DerSimonian 1986) and fixed‐effect models (inverse variance method) to calculate the pooled intervention effect for each outcome, and we present the results in a sensitivity analysis. As we found substantial statistical heterogeneity in the main pooled results and since the true intervention effect size varies across studies, as well as keeping in mind our aim to generalise the results to similar populations, we use the results from the random‐effects model.

When we found large variation among types of interventions, comparisons and outcomes evaluated in the reports included in this review and it was not appropriate to conduct a statistical meta‐analysis, we described and synthesised study findings in a narrative manner. For example, we considered that the studies comparing intervention to no intervention, wait‐list or placebo were different to those that compared intervention to treatment as usual. We therefore did not combine these studies with different control arms in the same meta‐analysis. Similarly, the studies that compared intervention to ‘treatment as usual’ were clinically heterogeneous due to the wide variation in what was considered usual treatment and therefore were not combined in a meta‐analysis. We structured the narrative synthesis around outcomes. We were unable to synthesise data to comment on clinical significance based on the outcomes provided in the studies.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored clinical heterogeneity by conducting the subgroup analyses listed below.

Intervention type: we pooled together two or more studies that provided AVDR (including interventions that did not explicitly identify themselves as AVDR, such as RADAR or several others), and separately pooled those that addressed only a response to violence and did not address attitudes, beliefs or knowledge change, in order to identify the effective components of an intervention.

Duration of the intervention: We pooled together interventions that took less than one day, that required two to seven days of training, and that lasted longer than one week. If booster sessions were provided, we included their duration when calculating the duration of the intervention.

Mode of delivery: We pooled together two or more studies that reported on delivery modes, including computer‐based training or in‐person lectures.

Teaching technique: We pooled together two or more studies that used specific teaching techniques including role‐plays, group discussions, lectures, experiential training or simulations

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the overall meta‐analysis to the following.

Model of meta‐analysis: we conducted both fixed‐effect and random‐effects meta‐analyses and presented both results when they differed.

ICC: for studies that did not account for clustering and where we could not borrow an ICC from other studies, we explored some simulated examples according to various combinations of mean and the ICC to account for clustering. Whilst the base case analysis is based on the 10% inflation of the SE of the study which did not consider the cluster effect, we have also explored two sensitivity analyses: one based on a scenario which did not inflate the SE of Short 2006b and another including a 30% inflation. See section on Differences between protocol and review for our justification for using this approach.

Outliers: where a study appears to be an obvious outlier, in line with the suggestion by Ryan 2016 we carried out sensitivity analyses with and without the study.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the five GRADE criteria: study limitations, imprecision, inconsistency of results, indirectness of evidence and likelihood of publication bias (Guyatt 2011), to assess the overall quality of the body of evidence for each of the Primary outcomes within 12 months of the intervention (HCPs attitudes towards, knowledge of and readiness to manage IPV, referrals for and response to IPV). On the basis of design, we viewed the RCTs included in the review as providing high‐certainty evidence, but downgraded to moderate, low or very low certainty, depending on the presence of the aforementioned GRADE criteria.

One review author (NK) applied the GRADE criteria independently, and another (LH) reviewed them. No disagreements occurred. We used this information to populate the overall certainty of evidence section of the Table 1, that also included information on the number of participants, RR for dichotomous outcomes, SMD for continuous outcomes, number of studies and their design. We created this table by using the software developed by the GRADE working group: GRADEprofiler (GRADEpro GDT 2014), for the comparison: training to respond to IPV versus no intervention, wait‐list, or placebo.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

We identified a total of 11,413 records from searches of bibliographic databases, and 56 additional records from websites and reference checking of relevant studies and systematic reviews (Figure 1). We removed 3123 duplicates and screened 8346 titles and abstracts. Abstract screening revealed 8103 irrelevant records, leaving 243 for full‐text review. The review authors excluded 213 records that did not meet the review criteria (see Figure 1). We identified 19 studies (from 21 reports) for synthesis and possible meta‐analysis. We contacted 31 study authors for additional information, 10 of whom responded and provided further details to aid us in our evaluation of potential study eligibility for inclusion (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Abraham 2011; Dubowitz 2011; Feder 2011; Feigelman 2011; Harris 2002. Hegarty 2013; Jack 2019; McFarlane 2006; Short 2006b). From the 9 reports which remained, we identified 3 which are awaiting classification, and 6 ongoing studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We include 19 studies in this review (from 21 reports). Fifteen of these are peer‐reviewed journal articles (Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Hegarty 2013; Hsieh 2006; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Moskovic 2008; Sharps 2016; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017), and four are PhD theses (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Cutshall 2019; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989).

The earliest trials were two unpublished PhD dissertations in the 1980s (Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989). Most of the studies (n = 12) were published in the 2000s. In the past decade, seven trials have been published, three of which were published in 2017 (Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Vakily 2017).

Additional reports on studies by Gupta 2017 and Hegarty 2013 were found in their respective published protocols. We also received results for Hegarty 2013 through personal communication. Information for Short 2006b and Harris 2002 was obtained through correspondence with Harris 2002.

Location and healthcare settings

Most studies were conducted in the USA (14 studies), with the remaining single studies from Australia (Hegarty 2013), and Iran (Vakily 2017), Mexico (Gupta 2017), The Netherlands (Lo Fo Wong 2006), and Turkey (Gürkan 2017).

Healthcare provider training interventions occurred in various teaching and clinical settings. Universities were the most frequently‐reported location for training (seven studies: Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Hsieh 2006; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989), followed by primary care clinics (five studies: Gupta 2017; Haist 2007; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Sharps 2016), and clinical teaching hospitals/schools (four studies: Coonrod 2000; Gürkan 2017; Moskovic 2008; Vakily 2017). Three studies used online platforms to deliver and evaluate provider IPV training (Cutshall 2019; Harris 2002; Short 2006b).

Study designs

Study designs varied. Twelve studies were RCTs conducted at the individual participant level (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Cutshall 2019; Danley 2004; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Hsieh 2006; Mauch 1982; Moskovic 2008; Ragland 1989; Vakily 2017). Of the remaining seven studies, four were cluster‐RCTs (Gupta 2017; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Short 2006b), and one apiece were a quasi‐RCT (Gürkan 2017), a quasi‐cluster‐RCT (Edwardsen 2006), and a combination of both individual randomisation in blocks along with randomisation of clusters (Sharps 2016).

Participants and sample size

The 19 included studies covered of 1662 HCPs, with the numbers of participants in each study ranging from 27 (Haist 2007) to 197 (Gupta 2017).

While a range of HCPs were included, medical staff were the most frequently studied (nine studies). This included medical residents/students (five studies: Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Edwardsen 2006; Haist 2007; Moskovic 2008) and qualified physicians/doctors (four studies: Harris 2002; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Short 2006b). The remaining providers included nurses, home visitors and nursing students (three studies: Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Sharps 2016), dentists and dental students (two studies: Danley 2004; Hsieh 2006), counsellors (including social workers) or psychology students/graduates (four studies: Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Cutshall 2019; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989), and one study of midwives (Vakily 2017).

Healthcare provider participant socio‐demographic characteristics were poorly described in seven studies (Coonrod 2000; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Hegarty 2013; Moskovic 2008; Sharps 2016; Vakily 2017). Only 12 of the 19 included studies clearly defined the sex of participants (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Cutshall 2019; Danley 2004; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Hsieh 2006; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989; Short 2006b). Eleven of the 19 studies included healthcare students still in training (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Hsieh 2006; Mauch 1982; Moskovic 2008; Ragland 1989), who had limited or no previous IPV training prior to the intervention.

IPV training interventions

Training content

Few studies provided comprehensive detail on IPV training content, with significant variation noted across trials. Studies commonly included some form of general information about IPV (types and definitions, prevalence and risk factors) to challenge myths and provider misinformation (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Cutshall 2019; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Haist 2007; Hegarty 2013; Hsieh 2006; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989; Sharps 2016; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017). Some also covered historical and cultural aspects of IPV (Cutshall 2019; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989; Vakily 2017), including sex role socialisation (Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989). Ragland 1989 showed media clips (news, movies/television) to emphasise community attitudes towards abused women.

Expanded IPV training content included exploration of common clinical presentations/impact on women’s health (Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Short 2006b), including perinatal health (Sharps 2016), reproductive coercion (Gupta 2017), and profiles on perpetrators and effects of partner violence on children (Lo Fo Wong 2006).

Some studies then followed up with clinical practice requirements, most frequently providing training in AVDR: Asking about IPV in order to identify IPV survivors, providing Validating responses, ensuring accurate Documentation, and Referralto specialist services. In particular, Danley 2004 and Hsieh 2006 used this AVDR framework explicitly in the development of their tutorial to train dentists on IPV. Danley 2004 reported delivering content on AVDR without any mention of foundational theory on IPV, such as common clinical presentations and impacts of IPV. Hsieh 2006 included how to identify signs of IPV in dental patients and then used an interactive, multimedia AVDR tutorial.

Other authors based their provider training around some or all of these core (AVDR) elements. The most common element of training (based on what was mentioned by the study authors) was on IPV identification through asking or routine screening (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Hsieh 2006; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Sharps 2016; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017). Only a third of studies reported training providers on accurate documentation of IPV (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Gürkan 2017; Harris 2002; Hsieh 2006; Sharps 2016). More than half of the included studies mentioned that they provided training on how to validate survivor experiences (Brienza 2005; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Harris 2002; Hegarty 2013; Hsieh 2006; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989; Short 2006b). A small sub‐set of these explicitly mentioned that they provided some kind of training in counselling (Gupta 2017; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982). Over half of all included studies explicitly mentioned training on referral options, including information about local women’s shelters (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Harris 2002; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Sharps 2016; Danley 2004; Edwardsen 2006; Hsieh 2006; Short 2006b).

Moskovic 2008 provided little detail on the didactic content of IPV training but included an experiential component (termed "outreach" (p 1043) by the authors) in the intervention, where medical students delivered the curriculum to adolescents on dating violence. A women’s DV safe shelter experience was offered to medical residents in Brienza 2005, to augment their IPV education by attending group evening sessions, where women survivors discussed their experiences and the impact of IPV on their work, health and children.

Edwardsen 2006 described the testing of a mnemonic to aid medical student IPV identification and management. All students received one hour of training on IPV, which included exposure to the mnemonic SCRAPED (Identification of IPV:Suspicion/screen, Central injuries, Repetitive, Abuse stated, Possessive partner, Explanation inconsistent, Direct questions; and Management of IPV: Safety, Crime reported, Referral, Acknowledgement, Protocols, Evidence collection, Documentation) and a model interview with an IPV survivor. The intervention arm then completed a smaller one‐hour workshop, which included detailed instruction and practice asking simulated patients about IPV, while using a laminated copy of the SCRAPED mnemonic. Controls received ‘standard teaching methods’ and obtained the mnemonic after the workshop. In a family home‐visiting IPV intervention that focused on prevention and early intervention, Sharps 2016 tested the Domestic Violence Enhanced Home Visitation Program (DOVE), which included training nurses to empower women by providing information, risk assessment, safety planning, emphasising her options and supporting her decision‐making and autonomy.

Other common content included explicitly addressing HCPs' beliefs or attitudes towards IPV (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Lo Fo Wong 2006), understanding the barriers to identifying IPV (Brienza 2005; Lo Fo Wong 2006), and IPV survivor barriers to presenting and disclosing violence (Brienza 2005; Mauch 1982). Also included were safety planning and risk assessment (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Sharps 2016; Short 2006b), use of clinical guidelines and screening tools/methods (Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Sharps 2016), and training on mandatory reporting/legislative requirements (Cutshall 2019; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Harris 2002; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Short 2006b).

Women’s ‘readiness to change’ their IPV relationship was included by Hegarty 2013 and Short 2006b in their online medical training programmes. Hegarty 2013 used motivational interviewing, tailoring a women‐centred approach to care with an emphasis on assessing women’s readiness rather than using a structured approach like AVDR alone, while Short 2006b developed an interactive case study to emphasise the concept of behaviour change and women’s readiness.

IPV training duration and methods

IPV training time frames ranged from 15‐minute, brief education sessions (Danley 2004; Hsieh 2006) to three days of intensive IPV training with clinic follow‐up visits by educators, to support HCPs' practice skills (Gupta 2017). More than half of the included studies (n = 9) offered two hours or less of IPV training. The remaining studies delivered approximately three (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016), four (Vakily 2017), five (Mauch 1982), six (Moskovic 2008), eight (Gürkan 2017; Hegarty 2013; Sharps 2016) and 15 (Cutshall 2019) hours of training, respectively. Hegarty 2013 and Sharps 2016 implemented provider training prior to and in addition to broader supportive systems‐level interventions. Cutshall 2019 offered 15 hours of online, interactive problem‐based learning to licensed professional counsellors, social workers and psychologists, delivered over three five‐hour modules. Short 2006b provided online continuous medical education (CME) to practising primary care physicians in the USA that included four to 16 hours of IPV learning. Most physicians (65%) completed the minimum time frame to obtain four CME points (Short 2006b), with only two physicians completing all online modules to obtain the full 16 CME points that count towards the physicians' continued licensing requirements. Two studies included booster training sessions, one at three months after training (Gupta 2017) and the other annually (Sharps 2016).

IPV training methods, as part of the interventions, were very heterogeneous. The varied level of detail provided in papers on IPV training made synthesis challenging. Most applied a didactic portion of the training and combined it with other varied pedagogical methods. Delivery of the intervention through group work was more common (12 studies: Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Cutshall 2019; Edwardsen 2006; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Haist 2007; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Moskovic 2008; Ragland 1989; Sharps 2016) than individually‐delivered content, which was usually accessed online (six studies: Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Danley 2004; Harris 2002; Hegarty 2013; Hsieh 2006; Short 2006b). One study (Vakily 2017) offered both methods, where team learning was followed up by viewing online content in individual sessions.

A variety of teaching methods were used to educate HCPs on IPV, and the skills required to respond to survivors of IPV effectively. Lecture or didactic information sessions, often combined with role‐play, were the most common (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Brienza 2005; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Hegarty 2013; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982; Sharps 2016), where participants worked in small groups and undertook the role of the HCP or patient (or used simulated patients) and practised asking about violence and responding in line with best‐practice methods. Nine studies used video footage in educational sessions to reinforce didactic content, depict survivor voices and model sound counselling skills (Brienza 2005; Coonrod 2000; Gupta 2017; Gürkan 2017; Hsieh 2006; Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017). Case studies/scenarios were also used and reflected common clinical presentations (Harris 2002; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017).

Clinical case studies or vignettes, familiar to trainees, were frequently used as learning tools. These were included as part of group work or online sessions (Gürkan 2017; Harris 2002; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Ragland 1989; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017). Seven studies used interactive online multi‐media methods (Cutshall 2019; Danley 2004; Harris 2002; Hegarty 2013; Hsieh 2006; Short 2006b; Vakily 2017).

Vakily 2017 offered a compact disc (CD) of IPV content (general information, case reports and videos) to the intervention‐group midwives, who also received the same content in didactic form. Harris 2002 and Short 2006b used online case studies of common clinical situations to reinforce best practice for existing medical practitioners. After watching the scenarios, users answered questions on how to respond and were provided with correct answers. Information also included online resources and referral options. Short 2006b used the online platform to deliver 17 typical, interactive, clinical IPV cases. These included simulated cases that often present in specialty areas: family medicine, mental health services, paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology.

Danley 2004 and Hsieh 2006 used a (brief) online AVDR teaching method for dentists. The tailored interactive resource depicts a clinical interaction between practising dentist and a patient (actors) who presents with facial trauma. Online users ask the virtual patient questions and they respond in various ways. The dentist then guides the user on their interaction and practice. Training methods evolve as authors engage with technology and advanced pedagogy. Hegarty 2013 used online distance education training combined with four teleconference sessions for doctors that were followed up with clinic visits for role‐play skills with simulated patients.

Other aspects of IPV training included the provision of readings (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Coonrod 2000; Edwardsen 2006; Hegarty 2013), and modelling best‐practice interviewing/counselling of patients, either by the educator (Mauch 1982) or using simulated patients (Edwardsen 2006; Haist 2007; Hegarty 2013). In a novel approach, Moskovic 2008 provided didactic IPV training to all medical students included in the trial. In addition, intervention‐group students delivered community‐based education to high school students on dating violence and relationship conflict, which reinforced their IPV learning.

Comparisons

Twelve studies compared IPV training with no training (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Cutshall 2019; Gürkan 2017; Lo Fo Wong 2006; Mauch 1982), placebo (Coonrod 2000; Haist 2007; Ragland 1989), or a wait‐list control group (Danley 2004; Harris 2002; Hsieh 2006; Short 2006b).

In three studies the control arm received some form of intervention that was described as usual care: Gupta 2017 (one day training); Sharps 2016 (usual care); and Vakily 2017 (traditional training).

For another four RCTs (Brienza 2005; Edwardsen 2006; Hegarty 2013; Moskovic 2008), an intervention with multiple components was provided in the intervention arm and one of the sub‐components of that intervention was provided alone in the comparator arm. This type of study tests the impact of component A of an intervention by implementing component A + component B in the intervention arm, versus only component B in the control arm. Brienza 2005 tested experiential learning in a women’s safety shelter + workshop seminar versus workshop seminar alone. Edwardsen 2006 tested the effect of a mnemonic technique + lecture/simulated patient versus lecture/simulated patient alone. Hegarty 2013 tested the impact of the Healthy Relationship Training program focused on responding to IPV survivors + a basic IPV education versus basic IPV education alone. Moskovic 2008 tested the impact of outreach education to adolescents + didactic training on IPV versus didactic training on IPV alone.

Measurement of outcomes

Primary outcomes

'Attitudes or Beliefs about IPV' were assessed in 10 studies using scales or subscales. The most commonly‐reported scales to measure attitudes or beliefs towards IPV were the Attitude Toward Battered Women Questionnaire (Mauch 1982; Ragland 1989) and the victim‐understanding subscale of the Physician Readiness to Manage Intimate Partner Violence Survey (PREMIS) (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Harris 2002; Short 2006b). Other measures used to assess HCPs' attitudes and beliefs towards IPV were: the Attitudes Towards Domestic Violence Scale (ATDVS) (Gürkan 2017); the attitude subscale of the Domestic Violence Assessment Instrument (Danley 2004); and the attitude subscale of the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (Hsieh 2006). Brienza 2005 used an attitude subscale of an instrument adapted from the Health Care Provider Survey for Domestic Violence, while Vakily 2017 developed a standardised 15‐item attitude measure for their study.

Ten studies assessed HCPs' 'readiness to manage/respond to survivors of IPV'. One study assessed this using a nine‐item (self‐developed) scale, which they called HCP confidence and attitude (Moskovic 2008); however, the items appear to assess medical students' confidence in their ability to address IPV, and discuss, recognise and respond to IPV. The most common scales to assess HCPs' readiness to respond to IPV were the self‐efficacy (Harris 2002; Short 2006b) or perceived preparation (Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Cutshall 2019; Hegarty 2013) subscales of the PREMIS, and the intended asking, validating, documenting and referring subscale of the Domestic Violence Assessment Instrument (Danley 2004; Hsieh 2006). Gürkan 2017 used HCP responses to open‐ended questions following a 'Written case study of violence against women' (WCSVAW) to determine percentage change in correct responses between intervention and control. Brienza 2005 assessed self‐perceived skills and resource awareness using an adaptation of the Health Care Provider Survey for Domestic Violence instrument.

HCPs' 'knowledge of IPV' was mostly assessed using questions that appear to have been developed by the authors (Coonrod 2000; Gürkan 2017; Moskovic 2008; Vakily 2017). A few studies used subscales, such as Brienza 2005 who assessed knowledge of IPV using a seven‐item subscale of the Health Care Provider Survey for Domestic Violence instrument, and Ayaba‐Apawu 2016; Cutshall 2019; Hegarty 2013 and Short 2006b, who reported on actual and/or perceived knowledge using the PREMIS (we only used results from the actual knowledge subscale and not perceived knowledge for this outcome).

'Referrals' provided by HCPs were assessed in three of the 19 included studies by measuring women’s use of community resources (as a result of HCP referrals) (Gupta 2017), the instances of offering referrals to simulated patients (Edwardsen 2006), or by asking an office manager about practice‐level referral relationships and if referrals of women to IPV services was routine or if there was evidence of contact with IPV service providers (even though only some HCPs from the practices were allocated to the control or intervention arm) (Short 2006b).