Abstract

In eukaryotic organisms, transfer RNA (tRNA)-derived fragments have diverse biological functions. Considering the conserved sequences of tRNAs, it is not surprising that endogenous tRNA fragments in bacteria also play important regulatory roles. Recent studies have shown that microbes secrete extracellular vesicles (EVs) containing tRNA fragments and that the EVs deliver tRNA fragments to eukaryotic hosts where they regulate gene expression. Here, we review the literature describing microbial tRNA fragment biogenesis and how the fragments secreted in microbial EVs suppress the host immune response, thereby facilitating chronic infection. Also, we discuss knowledge gaps and research challenges for understanding the pathogenic roles of microbial tRNA fragments in regulating the host response to infection.

Keywords: transfer RNA fragments, regulatory RNA, extracellular vesicles, outer membrane vesicles, microbial small RNAs, host-pathogen interaction

Introduction

To thrive in harsh conditions, micro-organisms must respond to changes in the environment, including iron deprivation, nutrient starvation, and host immune responses. The transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation by small RNAs (sRNAs) is a highly efficient mechanism to reshape microbial transcriptomes and metabolism in response to changes in the environment. Conventional microbial sRNAs are heterogeneous in size, ranging from 50 to 500 nt, and regulate gene expression by base-pairing with the translation initiation region or coding sequence of target mRNAs or by acting as sRNA sponges (Carrier et al., 2018). In the past decade, microbial non-coding sRNAs (ncRNAs) originating from intergenic regions have been characterized and reviewed extensively (Wagner and Romby, 2015; Carrier et al., 2018). Usually, ncRNAs from the intergenic regions have their promoters, and hence their expression is dictated by promoter activity and transcriptional regulators. Recently, it has become evident that intergenic regions are not the only source of microbial sRNAs. For example, sRNAs cleaved from 5' or 3' untranslated regions of mRNAs with regulatory roles have been reported (Ren et al., 2017; Manna et al., 2018).

Advancements in sRNA sequencing technologies and bioinformatics tools have led to the discovery of transfer RNA (tRNA)-derived fragments, leading to functional studies that have elucidated the regulatory roles of these fragments (Su et al., 2020). In eukaryotes and prokaryotes, tRNAs are the most abundant RNA species by the number of molecules (Neidhardt, 1996; Palazzo and Lee, 2015) and are evolutionarily conserved. Although most studies examining the role of tRNA-derived fragments have been conducted in mammals, in this mini-review, we focus on studies describing the biogenesis and cell-autonomous effects of microbial tRNA fragments. Also, we review papers that report the role of microbial tRNA fragments secreted in extracellular vesicles (EVs) and how they regulate gene expression in the host.

Extracellular vesicles secreted by microbes serve various functions, including intra-kingdom and inter-kingdom transfer of toxins, virulence factors, DNA, sRNAs, and tRNA fragments (Wang and Fu, 2019; Ahmadi Badi et al., 2020). There are several categories of EVs based on their origin, biogenesis, size (10–1,000 nm), and composition (Théry et al., 2018; Toyofuku et al., 2019). One of the main functions of EVs is to protect their RNA content from RNases present in the extracellular environment. In bacteria, the most studied EVs secreted by Gram-negative bacteria are outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) with a single bilayer derived from the outer membrane (Jan, 2017). Also, outer-inner membrane vesicles (O-IMVs), having a double bilayer composed of the outer and inner membranes, are secreted by Gram-negative bacteria, but only represent a very small fraction of EVs (Pérez-Cruz et al., 2015). OMVs and O-IMVs are ~100 nm vesicles that subserve various functions, including pathogen-pathogen interactions, and delivering virulence factors, sRNAs and tRNA fragments into host cells to modulate the host immune response (Kaparakis-Liaskos and Ferrero, 2015; Koeppen et al., 2016; Vitse and Devreese, 2020). Gram-positive bacteria and fungal pathogens also secrete EVs that contain sRNAs, tRNAs, and tRNA fragments (Peres da Silva et al., 2015; Resch et al., 2016; Alves et al., 2019; Rodriguez and Kuehn, 2020; Joshi et al., 2021). In sum, microbial EVs containing sRNAs and tRNA fragments deliver their contents to recipient cells, and a few studies have shown by transfecting synthetic RNA oligos and making sRNA-deletion mutants, that sRNAs and tRNAs regulate gene expression in eukaryotic host cells (Garcia-Silva et al., 2014a; Koeppen et al., 2016; Choi et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020).

This article summarizes the current stage of knowledge regarding the biogenesis of microbial tRNA fragments and their regulatory roles in pathogens and host cells. In addition, important knowledge gaps and research challenges regarding their roles in microbial pathogenesis will be discussed.

Microbial tRNA Fragments and Their Biogenesis

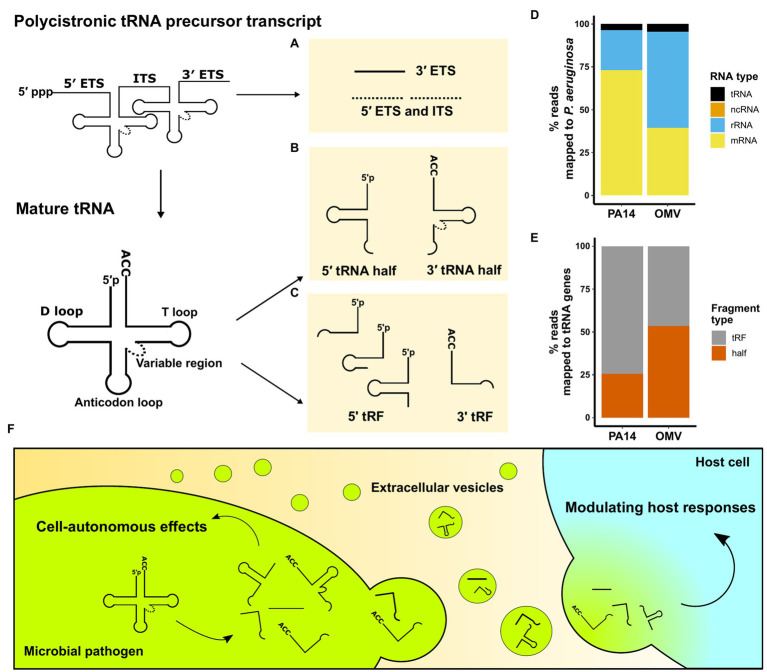

Transfer RNAs are 70–100 nucleotides (nt) long molecules with highly conserved sequences that form secondary cloverleaf and L-shaped three-dimensional structures (Fujishima and Kanai, 2014). Besides their well-known function as amino acid carriers to decode mRNA sequences in eukaryotes, numerous non-canonical roles of tRNAs have been identified, including tRNA fragment mediated gene silencing through an Argonaute-microRNA like mechanism (Maute et al., 2013) and both negative and positive effects on global regulation of protein translation (Yamasaki et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2017). The roles of tRNA fragments in eukaryotes have been extensively reviewed (Keam and Hutvagner, 2015; Su et al., 2020). tRNA fragments were first described in Escherichia coli in response to bacteriophage infection (Levitz et al., 1990). Over the past decades, using northern blot analysis and sRNA sequencing techniques, tRNA fragments have been found in all domains of life and are not random degradation products (Kumar et al., 2014). This article summarizes identified microbial tRNA fragments into three categories (Figures 1A–C). They are either derived from a polycistronic tRNA precursor transcript or a mature tRNA and include: (1) external transcribed spacer (ETS) and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences, (2) 5' and 3' tRNA halves, and (3) 5' tRNA-derived fragments (5' tRFs) and 3' tRNA-derived fragments (3' tRFs).

Figure 1.

An overview of microbial tRNA-derived fragments. (A–C) Three categories of tRNA fragments have been identified based on their origin and processing. Stable tRNA fragments can originate from polycistronic pre-tRNA transcripts or mature tRNAs. (A) ETS and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences are excised from the pre-tRNA transcripts; however, no stable 5' ETS and ITS (dotted) have been reported. (B) Cleavage at the anticodon loops creates 5' tRNA half and 3' tRNA half fragments. (C) RNases cleave near D loops and T loops to generate 5' tRFs and 3' tRFs. (D) sRNA unique sequencing reads from P. aeruginosa strain PA14 cells and their OMVs. Non-coding sRNAs (ncRNAs) are not visible on the plot as they accounted for less than 0.02% of total reads. (E) tRNA fragment type distribution of unique reads mapped to PA14 tRNA genes in PA14 cells and OMVs. Sequence reads in (D) and (E) are from Koeppen et al. (2016). (F) Schematic representation of microbial tRNA fragment-mediated effects in pathogens and the pathogen-to-host interaction via EVs.

The first category of tRNA fragments is the spacer RNAs arising from the tRNA maturation process (Figure 1A). tRNA precursors contain a 5' ETS and a 3' ETS. Prokaryotic tRNA precursors from operons have ITS to separate tRNAs. Multiple ribonucleases, including RNase P and E, are required to generate mature tRNAs and release ETS and ITS (Esakova and Krasilnikov, 2010; Shepherd and Ibba, 2015).

The second category of tRNA fragments consists of 5' tRNA halves and 3' tRNA halves, which are products of endoribonuclease-mediated cleavage in the anticodon loop of mature tRNAs (Figure 1B). 5' tRNA halves are 32–40 nucleotides from the 5′ terminus of mature tRNAs, while 3' halves are 40–50 bases from the anticodon loop to the 3' terminus due to the variable region and 3'-CCA. Various anticodon ribonucleases (ACNases) targeting the anticodon loop have been identified. In E. coli, T4 phage infection activates PrrC, a tRNALys-specific ACNase, as one of the suicidal events to protect the population from infection (Morad et al., 1993). Colicin E5 and Colicin D secreted from E. coli are ACNases that cleave multiple tRNAs of competing E. coli strains in half (Ogawa et al., 1999; Tomita et al., 2000). Ogawa et al. (2020) revealed that the anticodon-loop sequence of tRNAArg determines its susceptibility to colicin D, and they also demonstrated that the cleaved tRNAArg occupies the ribosome A-site leading to the impairment of translation. Similarly, fungi secrete different ribotoxins that generate 5' tRNA halves and 3' tRNA halves which inhibit cell growth of nonself yeast cells (Lu et al., 2005; Chakravarty et al., 2014). Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces MazF-mt9 that cleaves tRNALys in half, which downregulates bacterial growth (Schifano et al., 2016). Ribotoxins including VapCs in M. tuberculosis, Shigella flexneri, and Salmonella enterica target the anticodon loop of different tRNAs to modulate translation (Winther and Gerdes, 2011; Winther et al., 2016).

The third category of tRNA fragments includes 5' tRFs and 3' tRFs. These tRFs are cleavage products near the D loop or in the T loop of mature tRNAs (Figure 1C). 5' tRFs start from the extreme 5' end into the D stem, D loop, or anticodon stem; hence, 5' tRFs usually range from 18 to 31 nt. 3' tRFs are defined as sRNAs derived from cleavage in the T loop with a 3'-CCA end and about 18–22 nt in length. MazF-mt9 toxin in M. tuberculosis has been reported to cleave tRNAPro to generate 5' tRFs (Schifano et al., 2016). Due to the size similarity between microRNAs (miRNAs) in eukaryotes and tRFs, the miRNA generation machinery has been implicated in generating 5' tRFs and 3′ tRFs. Dicer, which plays a major role in the maturation of miRNAs, also cleaves several mature tRNAs to generate tRFs in vertebrates (Cole et al., 2009; Shigematsu and Kirino, 2015). sRNA sequencing analyses comparing wildtype and Dicer knockout cells in different eukaryotes reveal that Dicer is dispensable for the biogenesis of the majority of 5' tRFs and 3' tRFs (Li et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2014); however, in prokaryotes, the biogenesis of tRFs remains largely unknown at this time.

Microbial tRNA Fragments and Their Cell-Autonomous Effects

Lalaouna et al. (2015) identified the first functional tRNA fragment from an ETS in E. coli and demonstrated that the 3' ETS of leuZ (3' ETSleuz) is an sRNA sponge that inhibits the activity of target sRNAs, RyhB, and RybB. RyhB and RybB regulate iron homeostasis and outer membrane integrity, respectively. To demonstrate the physiological role of 3' ETSleuZ in E. coli, the authors reported that it prevents cells from using succinate as the sole carbon source and decreases antibiotic colicin sensitivity. Importantly, they demonstrated that Hfq, a conserved bacterial RNA-binding protein, is required to form the tRNA fragment-sRNA target complex.

Gebetsberger et al. (2012) sequenced sRNAs co-purified with ribosomes of Haloferax volcanii, a halophilic archaeon, and identified multiple 5' tRFs. They found that cells grown under elevated pH have abundant 5' tRNAVal fragment, which binds to small ribosomal subunits to inhibit translation globally. In addition, the 5' tRNAVal fragment of H. volcanii also attenuates protein synthesis by S. cerevisiae and E. coli’s ribosomes (Gebetsberger et al., 2017). Also the 3' tRNAThr half from Trypanosoma brucei has a similar effect in H. volcanii and S. cerevisiae to mediate translation stimulation (Fricker et al., 2019). These reports suggest a functionally conserved mode of action across life domains. Similar regulatory roles of 5' tRFs and 3' tRFs in S. cerevisiae have also been identified. Several tRFs in yeast bind to the small ribosomal subunits and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to reduce global translation (Mleczko et al., 2018).

Although 5' and 3' tRNA halves have been identified in many studies, the cell-autonomous effects of tRNA halves are largely unknown. Studies in M. tuberculosis and Aspergillus fumigatus suggest that micro-organisms maintain their persistence in host cells or remain in a life stage by cleaving tRNAs in half (Jöchl et al., 2008; Winther et al., 2016). Selective human 5' tRNA halves identified in saliva have high sequence similarity to tRNAs of Fusobacterium nucleatum, an oral opportunistic pathogen. Co-culture of human 5' tRNA halves with F. nucleatum inhibits bacterial growth, likely through interference with bacterial protein biosynthesis (He et al., 2018). Several studies have also demonstrated that environmental stress increases cytosolic tRNA halves in microbes (Thompson et al., 2008; Garcia-Silva et al., 2010; Fricker et al., 2019; Raad et al., 2021); however, the function of 5' and 3' tRNA halves induced by stress remains elusive.

Taken together, these initial reports describing the ubiquity and the function of cytosolic tRNA fragments in microbial cells and the differential expression of specific tRNA fragments (summarized in Table 1) suggest their possible roles in bacterial homeostasis and in regulating the expression of virulence factors.

Table 1.

Studies identifying and characterizing microbial transfer RNA (tRNA) fragments.

| Microbial species | Description of identified tRNA fragments | Proposed function and relevant findings of tRNA fragments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus fumigatus (ATCC46645) | 5' and 3' tRNA halves from multiple tRNAs during conidiogenesis were detected by northern blot analysis. | The cleavage of tRNAs into halves causes conidial tRNA depletion leading to the resting stage of A. fumigatus | Jöchl et al., 2008 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 5' and 3' tRNA halves from multiple tRNAs were detected by northern blot analysis during oxidative stress and stationary phase. | tRNA cleavage is not a function of quality control and unlikely to inhibit protein synthesis. | Thompson et al., 2008; Thompson and Parker, 2009 |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | About 25% of small RNAs (sRNAs) sequenced in the unicellular parasites were 5' tRNA halves from three specific tRNA isoacceptors. | Nutritional stress induces a significant increase of tRNA halves. | Garcia-Silva et al., 2010 |

| Trypanosoma cruzi | tRNA fragments were the second most abundant class in extracellular vesicles (EVs). A high level of tRNA halves from specific tRNA isoacceptors suggests differential packaging. | 5' tRNA halves are transferred between parasites to host cells via EVs. 5' tRNA halves affect gene expression patterns in host cells. | Bayer-Santos et al., 2014; Garcia-Silva et al., 2014a,b |

| Escherichia coli (MG1655) | Abundant tRNA fragments were found in both E. coli cells and outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). Over 90% of sRNA reads in OMVs were mapped to tRNA fragments. | The first report providing detailed profiling of the RNA content in E. coli cells and their OMVs and suggesting selective tRFs are packed into EVs. | Ghosal et al., 2015 |

| Escherichia coli (MG1655) | Excised 3' external transcribed spacer (ETS) of leuZ (3' ETSleuZ, 53 nt-long) was co-purified with sRNAs RyhB, and RybB. | 3' ETSleuZ is excised from the pre-tRNA transcript and acts as an sRNA sponge in E. coli to suppress the activity of sRNAs modulating tricarboxylic acid cycle fluxes and antibiotic sensitivity. | Lalaouna et al., 2015, 2017 |

| Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | A high abundance of 3' tRF Arginine (CCU) was found in fungal EVs. sRNA reads mapped to tRNAs account for 20–60% of all reads. | Arginine tRNA (CCU) is required to synthesize the heat shock protein at high temperatures through the regulation of translational frameshift. The production of 3' tRF from this tRNA is suggested to affect fungal gene expression. | Peres da Silva et al., 2015 |

| Leishmania donovani, Leishmania braziliensis | About 25–45% of all reads in the Leishmania EVs were mapped to tRNA fragments. Among those, 5' tRNA halves from a small subset of the same tRNA isoacceptors accounted for the majority of reads. | tRNA fragments and other sRNAs in EVs are delivered into macrophages. | Lambertz et al., 2015 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Multiple tRNA fragments were detected in microbes and OMVs. sRNA52320, a 5' tRNAfMet fragment and a 5' tRNAfMet half were differentially enriched in the OMVs compared to the cells. | A 5' tRNAfMet fragment is transferred into host cells where it targets the LPS-induced MAPK pathway to reduce IL-8 secretion. | Koeppen et al., 2016 |

| Escherichia coli (UPEC) strain 536 | In EVs, 27% of sRNA reads were mapped to tRNA fragments, and only 0.23% reads were mapped to mature intact tRNAs. | Detailed profiling of total RNA in EVs secreted by uropathogenic E. coli adds to the growing evidence of host-pathogen interactions mediated by sRNAs in EVs. | Blenkiron et al., 2016 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Multiple tRNA halves were identified by using deep sequencing and northern blot analyses. | Twelve anticodon nucleases cleave essential tRNAs to halt protein synthesis leading to survival in host cells. | Winther et al., 2016 |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | MazF-mt9 toxin cleaves tRNAPro14 and tRNALys43 in the D loop and anticodon loop, respectively. | The cleavage of specific tRNAs arrests translation and bacterial growth. | Schifano et al., 2016 |

| Haloferax volcanii | Multiple 5' tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) were co-purified with ribosomes and detected by sRNA sequencing and northern blot analyses. | 5' tRNAVal fragment production is induced at elevated pH, and the fragment binds to small ribosomal subunits to attenuate global translation. | Gebetsberger et al., 2012, 2017 |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Multiple 5' tRFs and 3' tRFs were co-purified with ribosomes and detected by northern blot analyses. | tRFs binds to small ribosomal subunit and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases to attenuate global translation. | Mleczko et al., 2018 |

| Trypanosoma brucei | tRNA halves were significantly induced during nutrient deprivation. 3' tRNAThr half was the most abundant sRNAs. | 3' tRNAThr half associates with ribosomes to stimulate translation during the recovery from nutritional stress. | Fricker et al., 2019 |

| Bradyrhizobium japonicum (rhizobium) | Rhizobial tRFs were identified in soybean nodules. | Rhizobial 5' and 3' tRFs are positive regulators of plant nodulation mediated by AGO1. | Ren et al., 2019 |

| Escherichia coli | The susceptibility of four E. coli tRNAArg isoacceptors to colicin D, an anticodon nuclease, was tested. | Cleaved tRNAArg occupies ribosomal A-site and thus impairs protein translation. | Ogawa et al., 2020 |

| Helicobacter pylori J99 | 3' tRNAAsn half and 5' tRNAfMet fragment were identified as the most abundant and differentially packed sRNAs in EVs. | sR-2509025, a 5' tRNAfMet fragment, is transferred from OMVs into human gastric adenocarcinoma cells and reduced the OMV-induced IL-8 secretion. | Zhang et al., 2020 |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | Around 88.2% of sRNA reads in EVs were mapped to tRNA fragments. | 5' tRNA halves are the most abundant sRNAs in EVs. The delivery of RNA cargo from EVs to host cells is via lipid raft-dependent endocytosis. | Artuyants et al., 2020 |

| Escherichia coli (MG1655) | Multiple tRNA fragments were detected in total RNA of cells from different growth stages. | Multiple tRFs are enriched in the stationary but not exponential phase suggesting the possible role of maintaining the stationary phase as well as the bacterial stress response. | Raad et al., 2021 |

Extracellular Vesicles are Important Mediators of Intercellular Communication and Delivery of tRNA Fragments to the Host

Intercellular communication mediated by EVs is an important aspect of host-pathogen interaction without direct cell-cell contact (Yáñez-Mó et al., 2015). Secretion of EVs as a mechanism of inter-kingdom and intra-kingdom communication is evolutionarily conserved, as organisms from prokaryotes, plants, and animal cells release EVs into the surrounding environment (Deatherage and Cookson, 2012; Gill et al., 2019; Woith et al., 2019). Identification of regulatory tRNA fragments in EVs has recently garnered attention and led to extensive sRNA content profiling of EVs secreted by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and intracellular parasites (summarized in Table 1). Ghosal et al. (2015) performed the first comprehensive sRNA profiling comparing E. coli and their secreted OMVs. In E. coli OMVs, over 90% of sequence reads were mapped to tRNA fragments, and the authors reported differential packaging of tRNA fragments in OMVs. In a study sequencing sRNA in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Koeppen et al., 2016), we found that tRNA fragments are more abundant than canonical ncRNAs (Figure 1D), and those tRNA fragments are differentially packaged in OMVs (Figure 1E). Moreover, we exposed human primary bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells to OMVs and used sRNA sequencing to demonstrate that tRNA fragments are the main P. aeruginosa sRNAs transferred from OMVs to host cells after exposure. Although tRNA fragments are only a small fraction of sRNAs in OMVs, their predominance in host cells suggests that tRNA fragments may have longer half-lives than other more abundant sRNAs. Moreover, EVs produced by Trichomonas vaginalis encapsulate abundant 5' tRNA halves and fuse with benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH-1) cells to deliver sRNAs (Artuyants et al., 2020). In addition, EVs secreted by Gram-positive bacteria, fungi, and even intracellular parasites also deliver protein toxins and sRNA products to host cells to modulate the host immune response (Rodrigues et al., 2008; Rivera et al., 2010; Silverman et al., 2010; Resch et al., 2016; Munhoz da Rocha et al., 2020).

Several studies have reported that tRNA fragments secreted in OMVs are involved in host-pathogen interactions. We demonstrated that sRNA52320, a 24-nt long 5' tRNAfMet fragment, is secreted by P. aeruginosa in OMVs that fuse with primary HBE cells and attenuates OMV-induced IL-8 secretion and recruitment of neutrophils into mouse lung by reducing the expression of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK; Koeppen et al., 2016). In our study, we used miRanda, a miRNA target prediction algorithm, to reveal that the 5' tRNAfMet fragment has specific targets in the MAPK signaling pathway in the host, including MAP2K2, MAP2K3, MAP2K4, MAP3K7, and PIK3R2. An unbiased proteomics approach confirmed our target predictions. In addition, sR-2509025, a 31-nt 5' tRNAfMet fragment, is secreted by Helicobacter pylori in OMVs and is delivered to human gastric adenocarcinoma cells and diminish LPS-induced IL-8 secretion (Zhang et al., 2020). Intriguingly, the 5' tRNAfMet fragments identified from these two independent studies have a high sequence similarity, with only four nucleotides difference in the 24-nt long overlapping region. Moreover, Garcia-Silva et al. (2014a,b) demonstrated that tRNA halves in Trypanosoma cruzi EVs are delivered into HeLa cells where the 5' tRNAThr half modulates the immune response, including upregulating CXCL2 gene expression.

Considering the findings discussed above, we propose that tRNA fragments delivered by microbial EVs to host cells are a widespread mechanism utilized to hijack the host immune response to enhance survival (Figure 1F). Additional studies are required to test this hypothesis, including studies on how microbes regulate the biogenesis of tRNA fragments in response to different environmental stimuli, the molecular mechanisms of differential packaging of tRNA fragments in EVs, and the molecular mechanisms whereby microbial tRNA fragments regulate the eukaryotic host response to infection. It will be informative to determine if microbial tRNA fragments delivered to eukaryotic hosts utilize the same mechanisms that mammalian tRNA fragments utilize (Chen and Shen, 2020).

Conclusion and Perspectives

Recent studies have demonstrated that tRNA fragments secreted by microbes in EVs regulate gene expression in various hosts, thus representing an important but underappreciated mechanism of host-pathogen interactions. Although progress has been made in elucidating the role of tRNA fragments in regulating gene expression in microbes and their hosts, there is much to be learned. For example, although sRNA sequencing has identified tRNA fragments in microbes and EVs, it is important to note current sequencing limitations and biases. First, most of the current approaches of preparing sRNA sequencing libraries rely on adaptor ligation, which requires 5' monophosphate and 3' OH of RNA molecules. This requirement limits the tRNA fragments that can be identified. For example, 5' ETS with 5' triphosphates and tRNA halves with 2-3-cyclic phosphate at the 3' end or 5' OH created by ACNases are not amenable to adaptor ligation. However, there are methods that use different enzymes to treat RNA samples before adaptor ligation to enrich RNA molecules with different end chemistries (Thomason et al., 2015; Shigematsu et al., 2018). Second, there are more than 90 post-transcriptional modifications found in tRNAs, which are required for their activity, and some of them impede reverse transcription during library preparation and RT-PCR experiments, which could lead to inaccurate profiling of tRNA fragments (Kellner et al., 2010; Lorenz et al., 2017). Also, the stable structure of tRNAs interferes with cDNA synthesis (Zheng et al., 2015; Behrens et al., 2021). Thus, new approaches are needed to identify tRNA fragments more thoroughly. In addition, better algorithms are needed to predict targets of tRNA fragments. Although tRNA fragments regulate gene expression by base-pairing with target genes in host cells, which is reminiscent of microRNA-mRNA interactions in eukaryotes, targeting algorithms for tRNA fragments should be improved due to a variety of factors. For example, sRNAs base-pair to targets with limited complementarity and conserved sequences called seed regions; however, the seed regions of tRFs and tRNA halves have not been fully characterized; thus, a better understanding of seed regions in tRNA fragments is required for a more accurate target prediction. With a better understanding of the targeting rules of tRNA fragments, it would be possible to generalize experiment findings on one tRNA fragment to other pathogens, given the highly conserved tRNA sequences in microbes (Saks and Conery, 2007).

Additional outstanding questions regarding the role of tRNA fragments in mediating host-pathogen interactions are worthy of note. Is the production and packaging of tRNA fragments into microbial EVs regulated? Does the nucleotide sequence or secondary structure determine differential packaging? How is the secretion of EVs regulated? How do microbial tRNA fragments regulate gene expression in eukaryotic cells? To what extent do microbial EVs in plasma regulate multiple organs? Do differences in EV isolation methods affect EV cargo and the effect of EVs on host cell biology? In this regard, the International Society of Extracellular Vesicles (ISEV) has published a suggested set of standards to increase rigor and reproducibility in EV research (Théry et al., 2018).

In conclusion, despite numerous publications demonstrating the existence of tRNA fragments in microbes and in secreted EVs, many details on the immunoregulatory role of tRNA fragments in regulating the host are unknown. We postulate that tRNA fragments are underappreciated molecules in microbial physiology and host-pathogen interactions (Figure 1F). We anticipate that a greater focus on these molecules in future investigations will lead to a more complete understanding of their roles in mediating host-pathogen interactions.

Author Contributions

ZL and BS conceived and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katja Koeppen and Thomas H. Hampton for reviewing this mini review and their collaboration on studies examining the role of tRNA fragments in host-pathogen interactions.

Footnotes

Funding. Grants from the NIH (P30 DK117469 and R01 HL151385) and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (STANTO19R0 and STANTO19GO) supported the research described in the authors’ laboratory.

References

- Ahmadi Badi S., Bruno S. P., Moshiri A., Tarashi S., Siadat S. D., Masotti A. (2020). Small RNAs in outer membrane vesicles and their function in host-microbe interactions. Front. Microbiol. 11:1209. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01209, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves L. R., da Silva R. P., Sanchez D. A., Zamith-Miranda D., Rodrigues M. L., Goldenberg S., et al. (2019). Extracellular vesicle-mediated RNA release in Histoplasma capsulatum. mSphere 4, e00176–e00119. 10.1128/mSphere.00176-19, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artuyants A., Campos T. L., Rai A. K., Johnson P. J., Dauros-Singorenko P., Phillips A., et al. (2020). Extracellular vesicles produced by the protozoan parasite Trichomonas vaginalis contain a preferential cargo of tRNA-derived small RNAs. Int. J. Parasitol. 50, 1145–1155. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2020.07.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer-Santos E., Lima F. M., Ruiz J. C., Almeida I. C., da Silveira J. F. (2014). Characterization of the small RNA content of Trypanosoma cruzi extracellular vesicles. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 193, 71–74. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.02.004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens A., Rodschinka G., Nedialkova D. D. (2021). High-resolution quantitative profiling of tRNA abundance and modification status in eukaryotes by mim-tRNAseq. Mol. Cell 81, 1802–1815.e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.01.028, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blenkiron C., Simonov D., Muthukaruppan A., Tsai P., Dauros P., Green S., et al. (2016). Uropathogenic Escherichia coli releases extracellular vesicles that are associated with RNA. PLoS One 11:e0160440. 10.1371/journal.pone.0160440, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrier M. -C., Lalaouna D., Massé E. (2018). Broadening the definition of bacterial small RNAs: characteristics and mechanisms of action. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 72, 141–161. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062607, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty A. K., Smith P., Jalan R., Shuman S. (2014). Structure, mechanism, and specificity of a eukaryal tRNA restriction enzyme involved in self-nonself discrimination. Cell Rep. 7, 339–347. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.034, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Shen J. (2020). Mucosal immunity and tRNA, tRF, and tiRNA. J. Mol. Med. 99, 47–56. 10.1007/s00109-020-02008-4, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. -W., Kim S. -C., Hong S. -H., Lee H. -J. (2017). Secretable small RNAs via outer membrane vesicles in periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 96, 458–466. 10.1177/0022034516685071, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole C., Sobala A., Lu C., Thatcher S. R., Bowman A., Brown J. W. S., et al. (2009). Filtering of deep sequencing data reveals the existence of abundant dicer-dependent small RNAs derived from tRNAs. RNA 15, 2147–2160. 10.1261/rna.1738409, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deatherage B. L., Cookson B. T. (2012). Membrane vesicle release in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: a conserved yet underappreciated aspect of microbial life. Infect. Immun. 80, 1948–1957. 10.1128/IAI.06014-11, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esakova O., Krasilnikov A. S. (2010). Of proteins and RNA: The RNase P/MRP family. RNA 16, 1725–1747. 10.1261/rna.2214510, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricker R., Brogli R., Luidalepp H., Wyss L., Fasnacht M., Joss O., et al. (2019). A tRNA half modulates translation as stress response in Trypanosoma brucei. Nat. Commun. 10:118. 10.1038/s41467-018-07949-6, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima K., Kanai A. (2014). tRNA gene diversity in the three domains of life. Front. Genet. 5:142. 10.3389/fgene.2014.00142, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Silva M. R., Cabrera-Cabrera F., Cura das Neves R. F., Souto-Padrón T., de Souza W., Cayota A. (2014a). Gene expression changes induced by Trypanosoma cruzi shed microvesicles in mammalian host cells: relevance of tRNA-derived halves. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:e305239. 10.1155/2014/305239, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Silva M. R., Cura das Neves R. F., Cabrera-Cabrera F., Sanguinetti J., Medeiros L. C., Robello C., et al. (2014b). Extracellular vesicles shed by Trypanosoma cruzi are linked to small RNA pathways, life cycle regulation, and susceptibility to infection of mammalian cells. Parasitol. Res. 113, 285–304. 10.1007/s00436-013-3655-1, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Silva M. R., Frugier M., Tosar J. P., Correa-Dominguez A., Ronalte-Alves L., Parodi-Talice A., et al. (2010). A population of tRNA-derived small RNAs is actively produced in Trypanosoma cruzi and recruited to specific cytoplasmic granules. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 171, 64–73. 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.02.003, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebetsberger J., Wyss L., Mleczko A. M., Reuther J., Polacek N. (2017). A tRNA-derived fragment competes with mRNA for ribosome binding and regulates translation during stress. RNA Biol. 14, 1364–1373. 10.1080/15476286.2016.1257470, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebetsberger J., Zywicki M., Künzi A., Polacek N. (2012). tRNA-derived fragments target the ribosome and function as regulatory non-coding RNA in Haloferax volcanii. Archaea 2012:e260909. 10.1155/2012/260909, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosal A., Upadhyaya B. B., Fritz J. V., Heintz-Buschart A., Desai M. S., Yusuf D., et al. (2015). The extracellular RNA complement of Escherichia coli. Microbiology 4, 252–266. 10.1002/mbo3.235, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill S., Catchpole R., Forterre P. (2019). Extracellular membrane vesicles in the three domains of life and beyond. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 43, 273–303. 10.1093/femsre/fuy042, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X., Li F., Bor B., Koyano K., Cen L., Xiao X., et al. (2018). Human tRNA-derived small RNAs modulate host–Oral microbial interactions. J. Dent. Res. 97, 1236–1243. 10.1177/0022034518770605, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan A. T. (2017). Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) of gram-negative Bacteria: A perspective update. Front. Microbiol. 8:1053. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01053, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jöchl C., Rederstorff M., Hertel J., Stadler P. F., Hofacker I. L., Schrettl M., et al. (2008). Small ncRNA transcriptome analysis from Aspergillus fumigatus suggests a novel mechanism for regulation of protein synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2677–2689. 10.1093/nar/gkn123, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi B., Singh B., Nadeem A., Askarian F., Wai S. N., Johannessen M., et al. (2021). Transcriptome profiling of Staphylococcus aureus associated extracellular vesicles reveals presence of small RNA-cargo. Front. Mol. Biosci. 7:566207. 10.3389/fmolb.2020.566207, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaparakis-Liaskos M., Ferrero R. L. (2015). Immune modulation by bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15, 375–387. 10.1038/nri3837, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keam S. P., Hutvagner G. (2015). tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs): emerging new roles for an ancient RNA in the regulation of gene expression. Life 5, 1638–1651. 10.3390/life5041638, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellner S., Burhenne J., Helm M. (2010). Detection of RNA modifications. RNA Biol. 7, 237–247. 10.4161/rna.7.2.11468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. K., Fuchs G., Wang S., Wei W., Zhang Y., Park H., et al. (2017). A transfer-RNA-derived small RNA regulates ribosome biogenesis. Nature 552, 57–62. 10.1038/nature25005, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppen K., Hampton T. H., Jarek M., Scharfe M., Gerber S. A., Mielcarz D. W., et al. (2016). A novel mechanism of host-pathogen interaction through sRNA in bacterial outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005672. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005672, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Anaya J., Mudunuri S. B., Dutta A. (2014). Meta-analysis of tRNA derived RNA fragments reveals that they are evolutionarily conserved and associate with AGO proteins to recognize specific RNA targets. BMC Biol. 12:78. 10.1186/s12915-014-0078-0, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalaouna D., Carrier M.-C., Semsey S., Brouard J.-S., Wang J., Wade J. T., et al. (2015). A 3' external transcribed spacer in a tRNA transcript acts as a sponge for small RNAs to prevent transcriptional noise. Mol. Cell 58, 393–405. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.013, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalaouna D., Prévost K., Eyraud A., Massé E. (2017). Identification of unknown RNA partners using MAPS. Methods 117, 28–34. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2016.11.011, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambertz U., Oviedo Ovando M. E., Vasconcelos E. J., Unrau P. J., Myler P. J., Reiner N. E. (2015). Small RNAs derived from tRNAs and rRNAs are highly enriched in exosomes from both old and new world Leishmania providing evidence for conserved exosomal RNA packaging. BMC Genomics 16:151. 10.1186/s12864-015-1260-7, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitz R., Chapman D., Amitsur M., Green R., Snyder L., Kaufmann G. (1990). The optional E. coli prr locus encodes a latent form of phage T4-induced anticodon nuclease. EMBO J. 9, 1383–1389. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08253.x, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Ender C., Meister G., Moore P. S., Chang Y., John B. (2012). Extensive terminal and asymmetric processing of small RNAs from rRNAs, snoRNAs, snRNAs, and tRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 6787–6799. 10.1093/nar/gks307, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz C., Lünse C. E., Mörl M. (2017). tRNA modifications: impact on structure and thermal adaptation. Biomol. Ther. 7:35. 10.3390/biom7020035, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Huang B., Esberg A., Johansson M. J. O., Byström A. S. (2005). The Kluyveromyces lactis γ-toxin targets tRNA anticodons. RNA 11, 1648–1654. 10.1261/rna.2172105, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna A. C., Kim S., Cengher L., Corvaglia A., Leo S., Francois P., et al. (2018). Small RNA teg49 is derived from a sarA transcript and regulates virulence genes independent of SarA in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 86, e00635–e00617. 10.1128/IAI.00635-17, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maute R. L., Schneider C., Sumazin P., Holmes A., Califano A., Basso K., et al. (2013). tRNA-derived microRNA modulates proliferation and the DNA damage response and is down-regulated in B cell lymphoma. PNAS 110, 1404–1409. 10.1073/pnas.1206761110, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mleczko A. M., Celichowski P., Bąkowska-Żywicka K. (2018). Transfer RNA-derived fragments target and regulate ribosome-associated aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1861, 647–656. 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.06.001, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad I., Chapman-Shimshoni D., Amitsur M., Kaufmann G. (1993). Functional expression and properties of the tRNA(Lys)-specific core anticodon nuclease encoded by Escherichia coli prrC. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 26842–26849. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)74188-X, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munhoz da Rocha I. F., Amatuzzi R. F., Lucena A. C. R., Faoro H., Alves L. R. (2020). Cross-kingdom extracellular vesicles EV-RNA communication as a mechanism for host–pathogen interaction. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 10:593160. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.593160, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidhardt F. C. (1996). Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2nd Edn. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Takahashi K., Ishida W., Aono T., Hidaka M., Terada T., et al. (2020). Substrate recognition mechanism of tRNA-targeting ribonuclease, colicin D, and an insight into tRNA cleavage-mediated translation impairment. RNA Biol. 1–13. 10.1080/15476286.2020.1838782 [Epub ahead of print], PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa T., Tomita K., Ueda T., Watanabe K., Uozumi T., Masaki H. (1999). A cytotoxic ribonuclease targeting specific transfer RNA anticodons. Science 283, 2097–2100. 10.1126/science.283.5410.2097, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo A. F., Lee E. S. (2015). Non-coding RNA: what is functional and what is junk? Front. Genet. 6:2. 10.3389/fgene.2015.00002, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peres da Silva R., Puccia R., Rodrigues M. L., Oliveira D. L., Joffe L. S., César G. V., et al. (2015). Extracellular vesicle-mediated export of fungal RNA. Sci. Rep. 5:7763. 10.1038/srep07763, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Cruz C., Delgado L., López-Iglesias C., Mercade E. (2015). Outer-inner membrane vesicles naturally secreted by gram-negative pathogenic bacteria. PLoS One 10:e0116896. 10.1371/journal.pone.0116896, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raad N., Luidalepp H., Fasnacht M., Polacek N. (2021). Transcriptome-wide analysis of stationary phase small ncRNAs in E. coli. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22:1703. 10.3390/ijms22041703, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G. -X., Guo X. -P., Sun Y. -C. (2017). Regulatory 3' Untranslated regions of bacterial mRNAs. Front. Microbiol. 8:1276. 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01276, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B., Wang X., Duan J., Ma J. (2019). Rhizobial tRNA-derived small RNAs are signal molecules regulating plant nodulation. Science 365, 919–922. 10.1126/science.aav8907, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resch U., Tsatsaronis J. A., Rhun A. L., Stübiger G., Rohde M., Kasvandik S., et al. (2016). A two-component regulatory system impacts extracellular membrane-derived vesicle production in group A Streptococcus. MBio 7, e00207–e00216. 10.1128/mBio.00207-16, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera J., Cordero R. J. B., Nakouzi A. S., Frases S., Nicola A., Casadevall A. (2010). Bacillus anthracis produces membrane-derived vesicles containing biologically active toxins. PNAS 107, 19002–19007. 10.1073/pnas.1008843107, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M. L., Nakayasu E. S., Oliveira D. L., Nimrichter L., Nosanchuk J. D., Almeida I. C., et al. (2008). Extracellular vesicles produced by Cryptococcus neoformans contain protein components associated with virulence. Eukaryot. Cell 7, 58–67. 10.1128/EC.00370-07, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez B. V., Kuehn M. J. (2020). Staphylococcus aureus secretes immunomodulatory RNA and DNA via membrane vesicles. Sci. Rep. 10:18293. 10.1038/s41598-020-75108-3, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saks M. E., Conery J. S. (2007). Anticodon-dependent conservation of bacterial tRNA gene sequences. RNA 13, 651–660. 10.1261/rna.345907, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano J. M., Cruz J. W., Vvedenskaya I. O., Edifor R., Ouyang M., Husson R. N., et al. (2016). tRNA is a new target for cleavage by a MazF toxin. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1256–1270. 10.1093/nar/gkv1370, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J., Ibba M. (2015). Bacterial transfer RNAs. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 280–300. 10.1093/femsre/fuv004, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu M., Kawamura T., Kirino Y. (2018). Generation of 2',3'-cyclic phosphate-containing RNAs as a hidden layer of the transcriptome. Front. Genet. 9:562. 10.3389/fgene.2018.00562, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigematsu M., Kirino Y. (2015). tRNA-derived short non-coding RNA as interacting Partners of Argonaute Proteins. Gene Regul. Syst. Bio. 9:GRSB.S29411. 10.4137/GRSB.S29411, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J. M., Clos J., de’Oliveira C. C., Shirvani O., Fang Y., Wang C., et al. (2010). An exosome-based secretion pathway is responsible for protein export from Leishmania and communication with macrophages. J. Cell Sci. 123, 842–852. 10.1242/jcs.056465, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Z., Wilson B., Kumar P., Dutta A. (2020). Noncanonical roles of tRNAs: tRNA fragments and beyond. Annu. Rev. Genet. 54, 47–69. 10.1146/annurev-genet-022620-101840, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théry C., Witwer K. W., Aikawa E., Alcaraz M. J., Anderson J. D., Andriantsitohaina R., et al. (2018). Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J. Extracell. Vesicles 7:1535750. 10.1080/20013078.2018.1535750, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason M. K., Bischler T., Eisenbart S. K., Förstner K. U., Zhang A., Herbig A., et al. (2015). Global transcriptional start site mapping using differential RNA sequencing reveals novel antisense RNAs in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 197, 18–28. 10.1128/JB.02096-14, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. M., Lu C., Green P. J., Parker R. (2008). tRNA cleavage is a conserved response to oxidative stress in eukaryotes. RNA 14, 2095–2103. 10.1261/rna.1232808, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. M., Parker R. (2009). The RNase Rny1p cleaves tRNAs and promotes cell death during oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 185, 43–50. 10.1083/jcb.200811119, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita K., Ogawa T., Uozumi T., Watanabe K., Masaki H. (2000). A cytotoxic ribonuclease which specifically cleaves four isoaccepting arginine tRNAs at their anticodon loops. PNAS 97, 8278–8283. 10.1073/pnas.140213797, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku M., Nomura N., Eberl L. (2019). Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 13–24. 10.1038/s41579-018-0112-2, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitse J., Devreese B. (2020). The contribution of membrane vesicles to bacterial pathogenicity in cystic fibrosis infections and healthcare associated pneumonia. Front. Microbiol. 11:630. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00630, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner E. G. H., Romby P. (2015). Small RNAs in bacteria and archaea: who they are, what they do, and how they do it. Adv. Genet. 90, 133–208. 10.1016/bs.adgen.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. F., Fu J. (2019). Secretory and circulating bacterial small RNAs: a mini-review of the literature. ExRNA 1:14. 10.1186/s41544-019-0015-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winther K. S., Gerdes K. (2011). Enteric virulence associated protein VapC inhibits translation by cleavage of initiator tRNA. PNAS 108, 7403–7407. 10.1073/pnas.1019587108, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winther K., Tree J. J., Tollervey D., Gerdes K. (2016). VapCs of Mycobacterium tuberculosis cleave RNAs essential for translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 9860–9871. 10.1093/nar/gkw781, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woith E., Fuhrmann G., Melzig M. F. (2019). Extracellular vesicles—connecting kingdoms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:5695. 10.3390/ijms20225695, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki S., Ivanov P., Hu G., Anderson P. (2009). Angiogenin cleaves tRNA and promotes stress-induced translational repression. J. Cell Biol. 185, 35–42. 10.1083/jcb.200811106, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yáñez-Mó M., Siljander P. R.-M., Andreu Z., Zavec A. B., Borràs F. E., Buzas E. I., et al. (2015). Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 4:27066. 10.3402/jev.v4.27066, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Zhang Y., Song Z., Li R., Ruan H., Liu Q., et al. (2020). sncRNAs packaged by Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles attenuate IL-8 secretion in human cells. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 310:151356. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151356, PMID: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng G., Qin Y., Clark W. C., Dai Q., Yi C., He C., et al. (2015). Efficient and quantitative high-throughput tRNA sequencing. Nat. Methods 12, 835–837. 10.1038/nmeth.3478, PMID: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]