Abstract

Background

Understanding gender gaps in trainee evaluations is critical because these may ultimately determine the duration of training. Currently, no studies describe the influence of gender on the evaluation of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellows.

Objective

The objective of our study was to compare milestone scores of female versus male PEM fellows.

Methods

This is a multicenter retrospective cohort study of a national sample of PEM fellows from July 2014 to June 2018. Accreditation Council for Medical Education (ACGME) subcompetencies are scored on a 5‐point scale and span six domains: patient care (PC), medical knowledge, systems‐based practice, practice‐based learning and improvement, professionalism, and interpersonal and communication skills (ICS). Summative assessments of the 23 PEM subcompetencies are assigned by each program’s clinical competency committee and submitted semiannually for each fellow. Program directors voluntarily provided deidentified ACGME milestone reports. Demographics including sex, program region, and type of residency were collected. Descriptive analysis of milestones was performed for each year of fellowship. Multivariate analyses evaluated the difference in scores by sex for each of the subcompetencies.

Results

Forty‐eight geographically diverse programs participated, yielding data for 639 fellows (66% of all PEM fellows nationally); sex was recorded for 604 fellows, of whom 67% were female. When comparing the mean milestone scores in each of the six domains, there were no differences by sex in any year of training. When comparing scores within each of the 23 subcompetencies and correcting the significance level for comparison of multiple milestones, the scores for PC3 and ICS2 were significantly, albeit not meaningfully, higher for females.

Conclusion

In a national sample of PEM fellows, we found no major differences in milestone scores between females and males.

Gender bias has been suggested to be a contributing factor to the lag in academic achievement of women compared to men. 1 , 2 , 3 For trainees, current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) evaluations may ultimately determine the total time needed for training. 4 Given this and the potential for evaluations to influence academic opportunities, medical educators have a role to monitor the presence of implicit biases in the evaluative processes in training programs. 5 While some studies have reported implicit gender bias in the evaluation of trainees, 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 others have found no gender differences. 10 , 11 Recent data from an emergency medicine resident data set show higher milestone ratings assigned to males than females after both direct observation at the end of training and qualitative differences in feedback. 8 , 9 However, research using ACGME milestone data for emergency medicine residents submitted by clinical competency committees (CCC) found no differences by sex of trainee. 12 Currently, no studies describe the influence of gender differences in the evaluation of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) fellows.

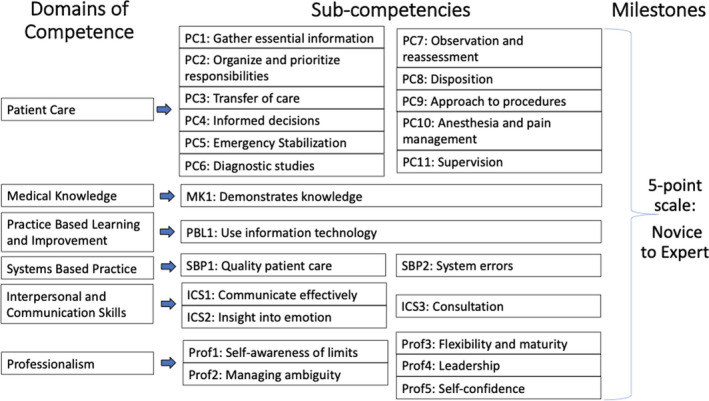

As part of the ACGME Next Accreditation System, PEM has 23 specialty‐based subcompetencies that are a combination of subcompetencies from pediatrics and EM residency milestone projects. 13 PEM‐specific subcompetencies within each of the six core domains: patient care (PC), medical knowledge (MK), practice‐based learning and improvement (PBLI), systems‐based practice (SBP), professionalism (PROF), and interpersonal and communication skills (ICS) are shown in Figure 1. The objective of our study was to compare milestone scores of female versus male fellows in PEM training.

Figure 1.

Domains of competence, subcompetencies, and milestones construct. MK = medical knowledge; PBLI = practice‐based learning and improvement; PC = patient care; Prof = professionalism; SBP = systems‐based practice.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting, and Population

This is a retrospective cohort study of PEM fellows from July 2014 to June 2018. During this time frame, there were between 73 and 77 PEM fellowship programs in the United States and between 159 and 178 new PEM fellows nationwide per year. 14 Beginning in January 2015, program directors (PDs) were required to report subcompentency milestone scores assigned by the program’s CCC for each trainee to the ACGME semiannually. 15 For this study, PDs were recruited during national meetings for PEM PDs and via e‐mail through a national PEM PDs listserv over a 6‐month period by a subgroup of PDs who served as the primary investigators. PEM fellowship PDs were asked to voluntarily share deidentified milestone reports for all of their trainees within the study time frame. Trainee milestone reports are available for download through the ACGME WebAds portal and were deidentified for fellow name and training program. Trainees automatically receive a unique ID number from the ACGME, which was used to track their information over time. Basic demographic information, which is entered for the fellow by each program, including sex, type of primary residency program (pediatrics vs. EM) and year entering fellowship was also collected.

Measurements and Data Analysis

For the purposes of statistical analyses, the individual 23 PEM subcompetencies were first evaluated within the six main competency domains, each as a separate hypothesis: 1) PC, 2) MK, 3) SBP, 4) PBLI, 5) PROF, and 6) ICS. Descriptive analysis of milestone scores for PEM fellows was completed for each year of fellowship (e.g., year 1, year 2, and final year). This included means and standard deviations (SDs) for each item as well as frequencies and percentages for categorical data such as male/female and type of residency program. While all trainees entering PEM fellowship after a pediatrics residency require 3 years of training, the length of training is variable for trainees entering fellowship after training in EM (either 2 or 3 years). In our analysis the final year of training represented the last year of training for a fellow. For each subcompetency, milestones are scored on a five‐level ordinal scale; only full and half‐level scores can be granted. Trainees can also receive a score of “not yet assessable” for each subcompetency. Any not yet assessable scores were excluded in the comparative analyses.

To address our primary aim of assessing differences in milestones scoring between male and female fellows during PEM training, mean response profile models with unstructured covariance models were used to evaluate the differences in mean scores for each of the six domains and 23 subcompetencies. The main effects included year of training, sex, geographical region, and the interaction term between the year of training and sex. To adjust for multiple comparisons, we used the Bonferroni correction, where the domain‐level alpha level of 0.05 was divided by the number of questions used in that domain: PC (11), MK (1), SBP (2), PBLI (1), PROF (5), and ICS (3). For example, for the domain PC, there were a total of 11 questions; therefore, the significance level was established at alpha of 0.05/11 = 0.0045. Results for select subcompetencies were summarized using plots of least‐square means and surrounding 95% confidence intervals for males and females for each year of training. Due to the very low number of fellows in some programs, we would have been unable to reliably estimate the program effect in our sample; therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by selecting programs with at least six fellows and introduced a random effect for program in addition to directly modeling the within‐fellow covariance.

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The human subjects committee and institutional review board approved this study and determined that the study qualified for exemption.

RESULTS

Of the active PEM fellowship programs in the United States, 48 participated in the study, which yielded data for 639 individual fellows (66% of all fellows nationally). Information on sex of trainee was missing for 35 fellows and these individuals were excluded, leaving 604 (94.5%) fellows remaining in the final analyses. Females comprised 67% of the sample. Demographic information for these fellows is provided in Table 1. Among the fellows who completed an EM residency prior to fellowship, five of the 30 (17%) completed 3 years of fellowship training.

Table 1.

Demographic Information by Gender

|

Female (n = 403) |

Male (n = 201) |

p‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary residency | |||

| Pediatrics | 383 (96%) | 186 (93%) | 0.23 |

| EM | 17 (4%) | 13 (7%) | |

| Geographic area | |||

| Northeast | 151 (37%) | 68 (34%) | 0.08 |

| South | 96 (24%) | 59 (29%) | |

| Midwest | 107 (27%) | 40 (20%) | |

| West | 49 (12%) | 34 (17%) | |

Data are reported as n (%).

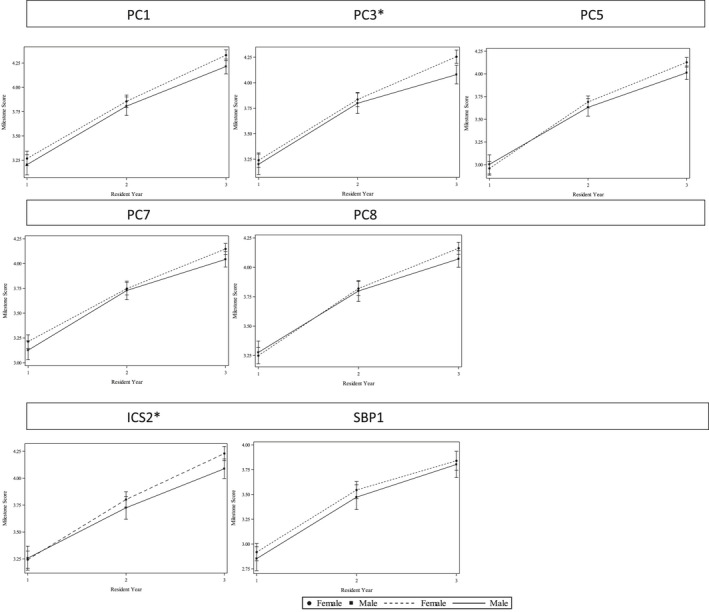

When comparing mean milestone scores in each of the six domains across the total study sample, there were no differences by sex in the first, second, or third years of fellowship training. We confirmed our findings in the sensitivity analysis with programs with at least six fellows (n = 5 or 10.4% of fellowship programs excluded). When comparing the individual subcompetencies within each domain for the total population, females had higher mean milestone scores than males for six subcompetencies in the final year of fellowship training only: PC1, PC 3, PC5, PC7, PC8, and ICS2 (Figure 2). However, when correcting our significance level for the comparison of multiple milestones, only PC3 and ICS2 mean scores continued to have statistical significance (PC3, 4.26 vs. 4.08, p = 0.022; ICS2, 4.23 vs. 4.09, p = 0.026).

Figure 2.

Milestone trajectories for females and males by year of training. *Significant after correcting for multiple comparisons. ICS = interpersonal and communication skills; PC = patient care; SBP = systems‐based practice.

DISCUSSION

In this national sample of PEM fellows, we found no major differences in ACGME milestone attainment by sex, with the exception that after correction for multiple comparisons, female fellows achieved significantly higher mean scores for two subcompetencies, PC3 and ICS2. PC3 evaluates the ability to provide seamless transitions in patient care and ICS2 evaluates the skills of developing insight and understanding into emotion and human response. It is possible these higher scores in females represent a higher achievement of or perception of skills requiring communication in transitioning care and responding to patient emotion. However, as mean scores for these two subcompetencies fall in the same “functional level,” for females and males, this may more likely represent a statistical rather than clinical attainment difference.

Standardized milestone assessments have inherent implications to limit biases. 4 , 15 The original intent of the ACGME was for training programs to use milestones as summative assessments assigned by the programs’ CCC and not individual raters. A recent study of EM residents found that the rate of milestone attainment was higher for male than females throughout training using postshift evaluations by direct faculty observation in eight programs. 8 Narrative comments attached to the milestone evaluations also found qualitative differences in feedback given to female versus male residents. 9 Subsequent to these studies, Santen et al. 12 examined a national data set of semiannual EM resident milestone ratings to determine if the previous studies’ findings were reproducible when all EM programs were evaluated and when milestones were assigned by the CCC (similar to our methods) versus direct observation. Of note, in the EM resident population in this study, males comprised 64.2% and females 34.8% of trainees (the inverse of our PEM fellow population). Santen et al. found only four of the 23 EM‐specific subcompetencies, all in the domain of PC, showed statistically significant, but small absolute differences in milestones by gender favoring males. They concluded that males and females were rated similarly by the CCC at the end of their training for the majority of EM subcompetencies.

Our methods also utilized CCC summative milestones assignment. An assessment by a group of trained faculty educators utilizing multisource data may allow more broad and unbiased assignments. Moreover, these findings may inform PDs who select CCC members and have the ability to provide additional training in the recognition and reduction in implicit biases in evaluations. Additionally, as CCCs are tasked with making milestone assessments using multiple data sources, consideration of the potential for bias within specific data sources (such as direct observation) can be given. A recent study of nursing evaluations of EM residents highlighted this potential bias demonstrating lower evaluations in the categories of ability and work ethic for female versus male residents. 16 Utilizing standardized assessments in controlled or simulated environments may also be helpful, especially if there are discrepant evaluations for trainees. In a 2018 study of medical simulations for EM residents conducted with a scripted and standardized assessments found that there were no differences in scores due to resident or rater gender, supporting these assessments to limit bias. 17 These simulated assessments can be part of a larger portfolio of multisource evaluation tools utilized by CCCs to consider when assigning semiannual competency ratings. Given the continued need to ensure that gender bias is not contributing to inequity in trainee evaluations, additional research is needed to identify better tools to assess this bias in training. Collaboration with medical education colleagues to study the effect of gender bias on trainee educational achievement, promotion, self‐efficacy, and perception would also be useful to achieve equity in this area.

Women make up the majority of the workforce in pediatrics, which may influence gender bias in our field of PEM. In pediatric medicine in 2017, women comprised 63% of physicians in practice, 57% of academicians, and 72% of residents. 18 , 19 Similarly in PEM in 2018 to 2019, 57% of physicians and 70% of first‐year fellows were female. 20 It is possible with a higher proportion of female trainees and faculty in pediatrics, compared with other more male‐dominated subspecialties such as EM, implicit gender bias wanes. Preliminary findings abstracted from a study of pediatric residents assessed with milestones after direct observation during their PEM clinical rotation found no significant gender bias. 21 A recent study supported gender bias waning with the presence of more female residents, reporting an association between gender and implicit bias favoring men in leadership positions to be higher in EM residents compared to obstetric and gynecology residents. 22 The authors suggest that this is possibly explained by the higher proportion of females in leadership roles in obstetric and gynecology programs mitigating bias. As implicit gender bias reflected in trainee evaluations has the potential to carry over to academic promotion and future success, strategies to combat this problem among all specialties are needed. Our and others’ findings of less implicit gender bias in female‐dominated specialties lends support to the value of increasing the proportion of women across specialties as trainees and in leadership positions as a potential mechanism to mitigate gender bias.

LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations in our study. First, the sample size was limited by the response rate from programs, which was approximately 65%. While the geographical representation was inclusive, the programs that did not report their milestone assignments may have had different outcomes from those programs that did respond. There were a low percentage of fellows from the west coast, which is a reflection of the percentage of programs in that area (16% of national). Similarly, there is a low percentage of EM‐trained PEM fellows, which reflects national trends. These fellows have variable lengths of training and we chose to compare their final‐year scores to the third‐year scores of pediatrics‐trained fellows. We chose to use the PEM milestones assessment to assess implicit gender bias, which we did not find in our sample. Although our data reflect the reported national gender distribution for PEM fellows, we have no information about the distribution of gender among the programs that did not respond, which could potentially skew data if different than the overall sample. The milestone assessments are a blunt instrument, limited in variability and, thus, potentially in their inherent ability to determine implicit gender bias. Although we show no difference in female versus male metrics, this does not provide information on the accuracy or bias related to these assessments. We found no differences in milestones by sex and year of training, but did not assess between years of training. Additionally, because it is important to understand biases at the program level, individual programs should consider conducting ongoing evaluations of differences in female versus male trainees in their CCC milestone assessments. We chose to look at the summative milestone evaluations only. Information on direct observation/individual feedback was not assessed and may have found differences in females compared to males in our setting (similar to the study by Dayal et al. 8 ); however, this was not part of our study’s data collection. We also did not collect data on the structure, process, or gender make‐up of the CCC at each program. There is not a standardized faculty structure or process for the CCC nationally; however, research in EM residencies has reported that most of their CCCs include program leadership, meet regularly, and use multisource data to make summative assessments. 23 Despite the potential for variability in PEM CCCs, we did not find major differences in PEM trainee assessments in females versus males. Combining the subcompetencies by competency domain in analysis is a limitation; however, the analysis was also performed at the subcompetency level. Our primary analysis did not directly take into account the effect of fellowship program, although our sensitivity analysis corroborated our findings. Finally, it is possible the summative assessment of PEM milestones scales are not refined enough to detect educationally significant differences.

CONCLUSIONS

In a national cohort of pediatric emergency medicine programs, we found no major meaningful differences in pediatric emergency medicine specific milestone scores reported to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in female versus male trainees.

AEM Education and Training. 2021;5:1–7

Presented at the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Virtual Annual Meeting, May 2020; and accepted for presentation at the Pediatric Academic Society National Meeting, Philadelphia, PA April 2020 (meeting canceled due to COVID‐19).

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

Author contributions: study concept and design—NZ, KL, MK, JR, CR, TV, AB, KL, and ML; acquisition of the data—NZ, KL, MK, JR, CR, TV, AB, KL, and ML; analysis and interpretation of the data—NZ, KL, MK, JR, CR, TV, AB, KL, and ML; drafting of the manuscript—NZ, KL, and ML; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content—NZ, KL, MK, JR, CR, TV, AB, KL, VS, and ML; statistical expertise—VS; administrative, technical, or material support—ML; study supervision—ML.

References

- 1. Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA 2016;315:2120–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cydulka RK, D’Onofrio G, Schneider S, Emerman CL, Sullivan LM. Women in academic emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spector ND, Asante PA, Marcelin JR, et al. Women in pediatrics: progress, barriers, and opportunities for equity, diversity, and inclusion. Pediatrics 2019;144:2019–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system ‐ Rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1051–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cooke M. Implicit bias in academic medicine: #WhatADoctorLooksLike. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:657–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thackeray EW, Halvorsen AJ, Ficalora RD, Engstler GJ, McDonald FS. The effects of gender and age on evaluation of trainees and faculty in gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1610–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rand VE, Hudes ES, Browner WS, Wachter RM, Avins AL. Effect of evaluator and resident gender on the American Board of Internal Medicine evaluation scores. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:670–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Qadri U, Arora VM. Comparison of male vs female resident milestone evaluations by faculty during emergency medicine residency training. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mueller AS, Jenkins TM, Osborne M, Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Arora VM. Gender differences in attending physicians’ feedback to residents: a qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ 2017;9:577–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brienza RS, Huot S, Holmboe ES. Influence of gender on the evaluation of internal medicine residents. J Women’s Health 2004;13:77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holmboe E, Huot S, Brienza R, Hawkins R. The association of faculty and the association of faculty and residents’ gender on faculty residents’ gender on faculty evaluations of internal medicine residents in 16 residencies. Acad Med 2009;84:381–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Santen SA, Yamazaki K, Holmboe ES, Yarris LM, Hamstra SJ. Comparison of male and female resident milestone assessments during emergency medicine residency training. Acad Med 2020;95:263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. The Pediatric Emergency Medicine Milestone Project 2015. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/PediatricEmergencyMedicineMilestones.pdf?ver=2015‐11‐06‐120523‐717. Accessed May 9, 2020.

- 14. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: Specialties Matching Service 2018 Appointment Year. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2018. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/report‐archives/. Accessed May 9, 2020.

- 15. Holmboe ES, Edgar LH ACGME The Milestones Guidebook Version 2016. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/MilestonesGuidebook.pdf?ver=2016‐05‐31‐113245‐103. Accessed May 8, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brucker K, Whitaker N, Morgan Z, et al. Exploring gender bias in nursing evaluations of emergency medicine residents. Acad Emerg Med 2019;26:1266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siegelman JN, Lall M, Lee L, Moran TP, Wallenstein J, Shah B. Gender bias in simulation‐based assessments of emergency medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ 2018;10:411–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Association of American Medical Colleges . Table 2.2 Number and Percentage of ACGME Residents and Fellows by Sex and Specialty, 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/data‐reports/workforce/interactive‐data/acgme‐residents‐and‐fellows‐sex‐and‐specialty‐2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2020.

- 19. Association of American Medical Colleges . Table 13 U.S. Medical School Faculty by Sex, Rank, and Department. 2017. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020‐01/2017Table13.pdf. Accessed Feb 2, 2020.

- 20. Pediatric Physicians Workforce Data Book 2018–2019 . American Board of Pediatrics. Pediatric Physicians Workforce Data Book, 2018–2019. Available at: https://www.abp.org/sites/abp/files/workforcedata2018‐2019.pdf. Accessed Feb 2, 2020.

- 21. Rabon L, McGreevy J, Mirea L.Gender gaps in the pediatric emergency department: how does gender affect evaluations? [Abstract/Platform Presenation #1170.8]. In: Baltimore, MD: Pediatric Acacemic Societies Meeting; 2019.

- 22. Hansen M, Schoonover A, Skarica B, Harrod T, Bahr N, Guise JM. Implicit gender bias among US resident physicians. BMC Med Educ 2019;19:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Doty CI, Roppolo LP, Asher S, et al. How do emergency medicine residency programs structure their clinical competency committees? A survey. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:1351–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]