Abstract

Objective

In the era of competency‐based medical education (CBME), the collection of more and more trainee data is being mandated by accrediting bodies such as the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. However, few efforts have been made to synthesize the literature around the current issues surrounding workplace‐based assessment (WBA) data. This scoping review seeks to synthesize the landscape of literature on the topic of data collection and utilization for trainees’ WBAs in emergency medicine (EM).

Methods

The authors conducted a scoping review in the style of Arksey and O’Malley, seeking to synthesize and map literature on collecting, aggregating, and reporting WBA data. The authors extracted, mapped, and synthesized literature that describes, supports, and substantiates effective data collection and utilization in the context of the CBME movement within EM.

Results

Our literature search retrieved 189 potentially relevant references (after removing duplicates) that were screened to 29 abstracts and papers relevant to collecting, aggregating, and reporting WBAs. Our analysis shows that there is an increasing temporal trend toward contributions in these topics, with the majority of the papers (16/29) being published in the past 3 years alone.

Conclusion

There is increasing interest in the areas around data collection and utilization in the age of CBME. The field, however, is only beginning to emerge, leaving more work that can and should be done in this area.

McGaghie and colleagues first proposed competency‐based medical education (CBME) in their World Health Organization report in 1978, 1 where they detailed the need to transition from a subject‐based curriculum or even an integrated curriculum to CBME in order to truly produce physicians that “can practice medicine at a defined level of proficiency, in accord with local conditions, to meet local needs.” 1 The first step in transitioning to CBME (and realizing its full potential) is to define professional competence and its components. 1 In the late 1990s, medical education took this first step in the form of the Canadian Medical Education Directives for Specialists (CanMEDS) roles 2 , 3 and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies. 4 , 5

As the 21st century progressed, this transition to CBME became more concrete as specialty‐specific competencies were created. Emergency medicine (EM) was one of the first specialties to implement this form of CBME with the ACGME’s introduction of 23 EM competencies, each with five levels of milestones designed to be attained as training progresses. 5 , 6 , 7 More recently, the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada EM specialty committee developed a suite of 28 entrustable professional activities to encompass the CanMEDS milestones as part of their competence‐by‐design stage‐based program of development and assessment. 8

One barrier to CBME is that, to accurately assess the learner’s progression through training, the associated programmatic assessments for each learner require voluminous amounts of information from multiple sources. The clinical workspace is a rich learning environment with significant potential to provide these data. 9 , 10 Missing the opportunities within the clinical workspace to capture trainee assessments would result in a narrower picture of each trainee’s abilities. 9 , 10 Programs of assessment potentially allow residencies or fellowships to strengthen the rigor and accuracy of trainee assessment by allowing for more perspectives and voices within the data, 11 for larger population‐level analyses of achievement to unveil systemic biases, 12 , 13 and for program evaluation to identify gaps in training programs. 14 Some organizations have found that specific programs of assessment substantially increase the frequency of assessment for individual trainees, resulting in even more data, 15 , 16 , 17 with some programs reporting the collection of thousands of data points from workplace environments. 18 As this volume of data is generated, there exists an increased responsibility to determine its value and use the data appropriately to guide both decision making and educational support of trainees. 18 , 19 To do so requires delineation of best practices and isolation of effective methods of high‐quality data aggregation that can function with large volumes of data.

The goal of this scoping review is to synthesize the literature from EM and provide key considerations for those interested in engaging in scholarship within the domains of collecting, aggregating, and reporting workplace‐based assessment (WBA) data and to guide its future use, supporting educational decision making for trainees, particularly in the context of CBME.

METHODS

We conducted a scoping review of the literature (systematic search of literature, followed by a thematic mapping of the findings) per the protocol of Arksey and O’Malley. 20

Step 1: The Research Question

A core group of investigators (TC, MG, CS) met to determine the bounds of this review. Via discussion about key issues within the literature around CBME, this group determined that with regard to WBAs, the evidentiary chain is from workplace to reporting. After determining three key components (i.e., direct observation, data collection/aggregation/reporting for decision‐making and supporting trainees, data utilization by trainees), we focused on one key area: What are the primary considerations when collecting, aggregating, reporting WBA data for the diagnosis and support of trainees?

Step 2: Relevant Studies

With the assistance of a medical librarian (JW), we conducted a search of six databases (PubMed, Scopus, ERIC, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Google Scholar). The search was conducted on January 10, 2020. No date limit was imposed. After removing duplicates (n = 9), we were left with 189 unique titles and abstracts to review. The search terms are in Data Supplement S1, Appendix S1 (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper, which is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/aet2.10544/full).

Step 3: Literature Selection

Two reviewers (TC, SSS) reviewed the abstracts using Covidence (covidence.org), and a kappa statistic was calculated for this first screening for inclusion versus exclusion. All discrepancies were resolved via a consensus‐building process between the two reviewers. Full texts of the remaining papers (n = 63) were then acquired, and three reviewers (TC, WC, SSS) screened the full texts for determination of final inclusion or exclusion, based on the screening criteria. Our inclusion criteria were dictated by our initial research question. Works that highlighted procedures addressing the collection, aggregation, analysis, or report generation of WBAs for further downstream educational decision‐making (e.g., for competency committee utilization, summative decisions, and supporting trainees throughout training) were included. To facilitate study selection, we restricted our selection processes to journal articles and conference proceedings (including conference papers and white papers) that were indexed within our selected databases.

Step 4: Charting the Data

Based on our research questions and informed by previous scoping review studies completed by our lead author, 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 we designed a data extraction tool incorporating the Cook, Bordage, and Schmidt framework for different types of scholarships (description, justification, and clarification). 26 We also attempted to classify the outcomes measured in empirical studies according to Kirkpatrick's evaluation framework. 27 , 28 , 29 Authorship team members (TC, WC, SSS) reviewed the Google Form (Mountainview, CA) extraction tool and provided feedback in an iterative fashion, refining this tool among the team based on a selected sample of four papers. The final extraction tool can be found in Data Supplement S1, Appendix S2.

Step 5: Collating, Reporting, and Summarizing the Data

Our final list of papers for full‐text review and extraction were divided among the entire authorship team. Authors were responsible for a final review of each paper regarding its suitability for our study (applying our inclusion and exclusion criteria once more). For the studies where the extractor was unsure about inclusion, a second author was asked to review the paper to render a final decision. Non–English‐language articles were excluded at this phase.

After meeting inclusion criteria, remaining papers underwent the extraction process with the aforementioned data extraction tool. During the extraction process, we used an inductive method to identify key themes related to the techniques for improving data collection, aggregation, analysis, and representation/visualization for informing decisions about trainee progress. Initially, the list of categories was restricted to common themes that our authorship team thought would be prevalent within the literature, but this list of themes was iteratively expanded throughout the data extraction process.

All summary statistic calculations were completed with either Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) or SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Step 6: Consultation

Upon completing our data extraction, the themes and findings from our study were reviewed with three education researchers with domain‐relevant expertise. We used this optional step within the Arksey and O’Malley process because our lead author (TC) had reflected that she had been highly embroiled in this area and wished to have external experts participating to check the comprehensiveness of our review processes. We used this consultation process as a method to engage in a form of reflexivity check. These researchers were required to have a graduate degree in education or psychometrics and measurement and at least three peer‐reviewed publications within the area of data collection, aggregation, analysis, or representation and preferably published in more than one domain. Consulting researchers were known to the research team, and many had served as coauthors with at least one member of the authorship team. For the expert consultations, one‐on‐one conversations via video conference were initiated with the lead author (TC).

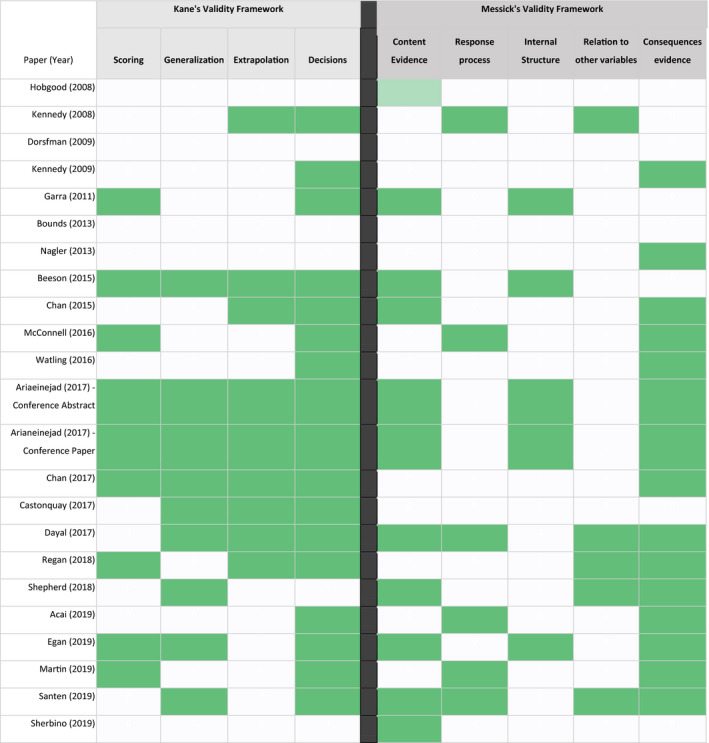

Based on the suggestions from our consultations, we conducted a final mapping exercise. Using two assessment validity frameworks (Kane and Messick), we determined whether the papers mapped, or could be logically categorized to, elements of these frameworks. 30 , 31 , 32 These mappings were thought to help new scholars better identify areas where they could engage in applying these validity frameworks.

RESULTS

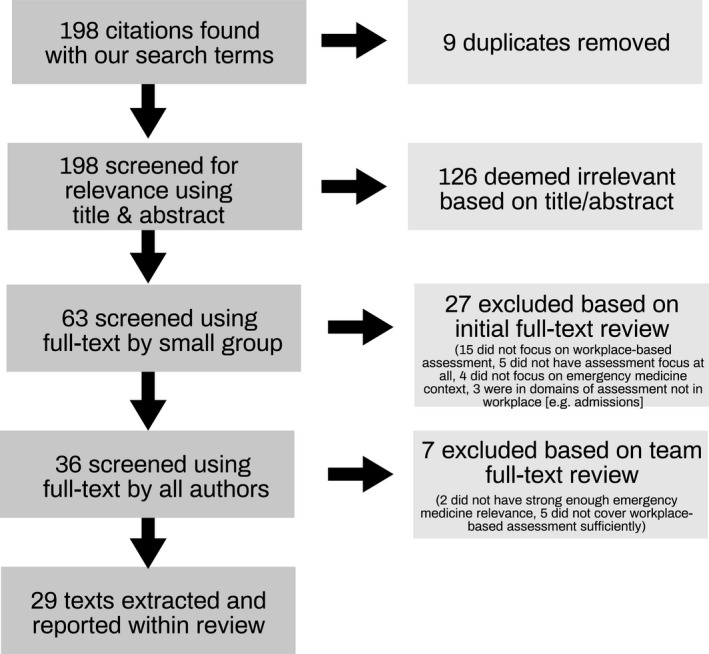

The search retrieved 198 potentially relevant references, which were reduced to 63 papers after removing duplicates and screening based on title/abstract alone. These 63 studies were then reviewed in full by three authors each to evaluate whether they met our inclusion and exclusion criteria. We excluded a total of 27 more papers at this phase. Seven more papers were excluded by the team after full‐text review by the rest of the authorship team (please see the flow diagram [Figure 1] for details).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of our literature screening and selection process.

About the Texts

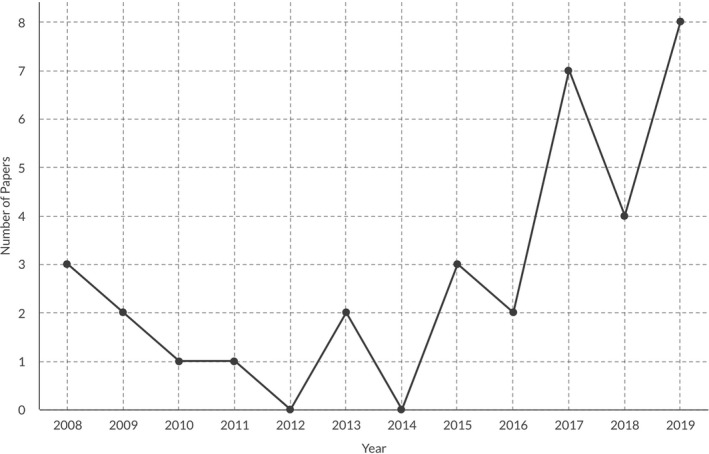

The date of the papers ranged from 2008 to 2019. The majority of papers were published in the past 3 years (55%, 16/29). Figure 2 displays the trend over time.

Figure 2.

The trend of publications found using this scoping review on the topic of workplace‐based assessment in emergency medicine from 2008‐2019.

Four of the texts that we reviewed were conference‐related content (three abstracts, one conference paper), with one abstract serving as an early report of the subsequent full conference paper. 33 Fifteen papers were descriptive papers, where authors described their design processes. There was one justification paper 34 and two clarification papers. 12 , 14 There were only six conceptual pieces (21% of all our papers) and three descriptions of innovations without evaluation data (10%, 3/29) within our findings, suggesting that the majority (66%, 19/29) of this area of EM education literature is empirically driven.

For empirically driven research (n = 19), the majority of papers were quantitative (53%, 10/19), while the remaining were qualitative work (31%, 6/19) or mixed methods (11%, 3/19). The quantitative approaches used in the studies included mainly descriptive techniques (n = 7); however, many also used inferential statistical techniques, including psychometrics (n = 3).

The majority of identified texts focused on EM only (72%, 21/29), but a large minority of our reviewed content featured other specialties (41%, 12/29). These other specialties included internal medicine, family medicine, surgery, pediatrics, psychiatry, neurology, obstetrics and gynecology, radiation oncology, and nephrology.

Due to the specialty‐oriented search, the vast majority of the papers in our final analysis focused on residents (89%, 25/29). Four articles (14%) featured multiple groups, including other groups such as medical students, fellows, practicing physicians, and members of other health care professions.

The majority of papers were conducted in or originated from North America (89%, 26/29). Of the remaining conceptual papers, one was from an international grouping of authors, one was from the International Federation of Emergency Medicine, and the other by the International Competency‐Based Medical Education collaborators.

The Forms of Evidence

Overall, studies fell into four major categories, as depicted in Table 1. Eighteen of the studies were descriptive in nature. 14 , 49 These papers usually described a phenomenon focusing on the first step in the scientific process (e.g., observation). 26 While these studies described the intervention and outcomes, they typically did not provide a comparison. Six papers were conceptual pieces (e.g., narrative review, opinion, editorial, or other theory‐advancing commentary). 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 Three papers were classified as justification studies. 34 , 41 , 56 Justification studies focus on the last step in the scientific method by comparing one educational intervention with another to address whether the intervention was effective. The remaining two papers were clarification studies. 12 , 14 These papers typically employ each step in the scientific method, starting with observations (often building on prior research), models, or theories and then using this to make and test predictions.

Table 1.

Types of Scholarship

| DESCRIPTION STUDY (usually of a phenomenon): focuses on the first step in the scientific method, namely, observation. For example, intervention descriptions outcome data reported, usually no comparisons. | 18 |

| JUSTIFICATION STUDY: focuses on the last step in the scientific method by comparing one educational intervention with another to address the question(often implied): "Does the new intervention work?" | 3 |

| CLARIFICATION STUDY: employ each step in the scientific method, starting with observations (typically building on prior research) and models or theories, making predictions, and testing these predictions. | 2 |

| CONCEPTUAL WORK (i.e., narrative review, opinion, editorial, or other theory advancing commentary). | 6 |

The reviewed publications consisted of six different methodologies. Nine studies were quantitative, 12 , 14 , 33 , 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 43 , 48 , 56 six were qualitative, 35 , 37 , 42 , 45 , 47 , 49 and two included mixed methodologies. 17 , 34 Many of the remaining publications were conceptual pieces, 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 innovation reports without results, 8 , 40 or consensus conference proceedings. 44

Validity Evidence

Validity frameworks are organizing concepts for guiding the construction of assessment tools. Data Supplement S1, Appendix S3, describes both Kane’s and Messick’s validity frameworks and provides a complete mapping of the 23 empirical papers within these two frameworks. Of the empirical papers, the majority of papers (n = 18/23) addressed at least one element of Kane’s validity framework, and nearly all addressed at least one element of Messick’s validity framework (n = 21/23). On the other hand, only two papers and one conference abstract addressed all the elements of Kane’s framework within a single paper. 33 , 43 , 48 Meanwhile, no single paper within our study addressed all of the elements of Messick’s validity framework.

Themes From the Literature Reviewed

All of these papers could be filed under one or more of the following four categories: 1) collecting workplace‐based assessment data; 2) aggregating workplace‐based data; 3) assessment of learning: data utilization (e.g., interpretation, visualization, analysis) for promotion, remediation, diagnosis of trainee problems; or 4) assessment for learning (e.g., visualization, analysis) for supporting trainee growth and development. Approximately half of reviewed literature (52%, 15/29) focused on one of the four key themes, with the other half addressing multiple themes (48%, 14/29). Four papers discussed all four of our themes. 12 , 46 , 52 , 53 There was one additional theme that was found in our literature review that focused on the functioning of competency committees, suggesting that this is an emerging area of scholarly interest. 33 , 37 , 43 , 51

The majority of the papers in our study addressed the first theme of collecting workplace‐based assessment data (62%, 18/29). The second theme (processes that assist in aggregating workplace‐based data) was covered by 45% (n = 13), and the third theme (processes that assist in data utilization for assessment of learning), 48% (14/29). Our final theme of examining data utilization for assessment for learning was only found in 31% of the papers (9/29).

Theme 1: Collecting WBA Data

Papers that addressed collection of WBA data were characterized by quantitative, qualitative, or mixed‐methods approaches as well as editorials and commentaries. Studies highlighted the need to move beyond number counting and toward assessment of specific components of competency. 44 , 50 They emphasized the importance of purposefully selecting psychometrically sound assessments matched to competency domains of interest and ensuring that selected tools are “fit for purpose.” 8 , 17 , 41 , 46 , 51 , 52 Authors reported not only on the value of collecting reliable quantitative data but also the utility of gathering rich qualitative data to add greater meaning to learner assessment and to facilitate data interpretation. 17 , 52

Three studies warned against rater‐ or learner‐driven sampling bias in data collection. 12 , 43 , 44 They encouraged the purposeful collection of WBA data using multiple methods, by multiple assessors, and across multiple contexts to mitigate the risks of biased sampling and to address limitations of individual assessment tools and individual rater shortcomings, such as halo or leniency effects. 18 , 43 , 46 Best practice models of programmatic assessment were described as a systematic way of organizing assessments; with regard to WBAs, this included the intentional collection of data from multiple sources over time. 46 Two papers provided detailed descriptions of the design and implementation of their program of assessment, 17 , 46 highlighting the benefits related to normalizing the collection of daily WBA and facilitating downstream data aggregation and interpretation.

A major challenge to collecting WBA data cited among several studies related to the feasibility of assessment methods and processes. 43 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56 Caretta‐Weyer and Gisondi 55 emphasized the need to simplify frontline assessment to be more intuitive for assessors to complete. They suggest that this could be done by designing collection forms that use task‐based components and that incorporate language that aligns with how supervisors make everyday judgments of learners. Other studies focused on the use of digital technology as a powerful tool to enhance data collection by facilitating real‐time feedback and documentation of learner performance. 17 , 34 , 37 , 52 Assessor training was also recognized as important and necessary for supporting faculty‐driven collection of learner assessment. 37 , 52 The paper by Lockyer et al. 52 provides a review of the literature addressing collection of WBA data in the context of CBME, highlighting best‐practices, and challenges, while offering suggestions to optimize the process.

Theme 2: Aggregating WBA Data

Aggregating WBA data describes how data collected by trainees could be consolidated and viewed holistically at the individual, program, or institutional level. Studies in this area were characterized by both qualitative and quantitative approaches to better understand how various assessments of residents in EM fit within a broader system of assessment or align with EM‐specific milestones or are consistent across different EM settings. The most commonly used qualitative approach was constructivist grounded theory to highlight the experiences and social interactions between trainees and their assessors. 35 , 42 , 45 Regression approaches with more specifically multilevel modeling was one quantitative approach used to model trainee progression over time. 43

A few studies offered frameworks and program descriptions that help guide effective aggregation of WBA from multiple sources. For example, Chan and Sherbino 17 describe the McMaster Modular Assessment Program (McMAP), a WBA system designed specifically for EM trainees. The assessments were EM aligned and blueprinted back to the national CanMEDS framework (i.e., a framework that describes the abilities physicians need to possess and demonstrate to be deemed effective in meeting patients’ needs).

Theme 3: Data (e.g., Visualization, Analysis) for Assessment of Learning

In addition to previous studies that focused on aggregating WBA data for a variety of purposes, we observed that studies in this area were often conducted to determine how aggregated data could be leveraged to track progression. The most frequent utilization was to identify issues (e.g., how trainees perceive their role) or determine which trainees were struggling. A theme around how clinical competence committees (CCCs) take these data to make decisions was also identified. Since these are a relatively new phenomenon, we did find that there was an intersection between the CCCs and the emerging literature around assessment of learning.

Acai and colleagues 37 interviewed 16 EM attendings about their experiences with the McMAP WBA system and noted logistic concerns as to how to accumulate sufficient digitalized data in a transparent, nongameable fashion that overcomes a bias against reporting negative feedback. While this qualitative study may need to be triangulated with actual analyses to determine if this perception aligns with the reality of data acquisition, it is still important to bear in mind how the absence of data may have ramifications for deciding trainee progression. This paper nicely maps to another paper within this program of research around the sources of missing data. 14

Beeson et al. 41 report on the even larger, cross‐program milestones data collected by the ACGME where, over a 68‐day window, they collected milestone data on 5,805 residents and found that it demonstrated a consistent factor structure. However, the factor loading (i.e., the clustering of milestones together in WBA data) described within this paper’s findings suggest that there are marked limits to our ability to use the milestones for decision‐making purposes.

Approaches to data visualization and analysis included automating case logs, developing structured educational programs, creating trainee report cards using electronic health record (EHR) data, and applying machine learning algorithms to flag struggling trainees. 33 , 48 , 49 Using the data aggregated in Chan and Sherbino’s McMAP system, Ariaeinejad and colleagues 33 , 48 conducted machine learning and regression analyses in an attempt to predict the future performance of trainees. They successfully predicted whether an individual trainee was “at risk” or “not at risk” based on the large data set. Machine learning algorithms could be used to enhance human decision making for deciding whether a resident might not be progressing in their learning or achievement.

In our validity framework analysis, we found that there was a trend toward increased use of both Kane’s and Messick’s validity frameworks in the literature. To depict this, we have chronologically mapped the literature for our review and used a heat mapping function to display the validity elements that we felt each paper displayed or addressed in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

A heat map that depicts the validity framework incorporation within the EM assessment literature over time.

Theme 4: Data Utilization (e.g., Visualization, Analysis) for Assessment for Learning

A number of studies have laid the groundwork for data‐driven interventions in real time. We perceived a shift from retrospective data analyses to prospective ones: from annual or semiannual reports that summarize a completed time period to the development of dashboards that update as the data is accumulated. Such systems are enabled by the increasingly digitalized environments in which clinical care is carried out. Shepherd et al. 49 interviewed EM trainees and faculty to determine which performance indicators could be pulled from the EHR and meaningfully used to represent both independent and interdependent clinical actions by the trainees.

When thinking of trainee support, we must also consider the role of program evaluation and systems‐level supports that are examined in the literature. What should not be overlooked is the benefit to the program of the data collected on behalf of individuals. Dorfsman et al. 57 observed 32 EM residents for 4 to 5 hours each and reaped a rich trove of information that pointed the way to program curriculum enhancements, in addition to the individualized feedback. Dayal et al. 12 used EM program evaluation data to show that sex bias may exist in resident evaluations. Using real‐time algorithms, their sex‐informed program evaluation process could also be the basis for real‐time reporting and intervention, especially as the differences became more manifest as the residents advanced in the program.

DISCUSSION

As CBME becomes more prevalent within medical education, 5 , 8 , 58 it is important to develop strategies for effective collection, aggregation, and dissemination of WBA data. This scoping review identified 29 EM publications specifically addressing this topic and identified several key patterns to inform practice and future research. This review reports these early studies within this area in hopes of providing new education scholars with insights on the scholarly conversations within our specialty.

When collecting data, multiple studies emphasized the need for using both quantitative and qualitative components to avoid the limitations of purely numeric‐based assessments. 17 , 44 , 50 , 52 Obtaining substantive comments on assessment forms can be challenging, 59 , 60 and future research should assess strategies for increasing qualitative comments. 61 , 62 , 63 Recent studies have also described tools for evaluating the quality of workplace‐based assessment comments (e.g., Completed Clinical Evaluation Report Rating tool, Quality of Assessment for Learning score). 59 , 64 One study found that targeted feedback improved qualitative feedback quality. 64 Future research should expand on this and determine strategies for increasing both the quantity and the quality of WBA data provided. Moreover, given the complexity and time‐pressured nature of the emergency department environment, efforts should also be made to facilitate WBAs by streamlining forms and utilizing technology to facilitate data entry and capture. 33 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 55 , 56

Data should be aggregated and presented in a manner to augment decision making or trainee support in a meaningful format. In this capacity, it would be valuable to utilize keyword technology and machine learning algorithms to identify trends to facilitate earlier interventions among “at‐risk” learners. 33 , 65 More recently (and outside of our present study period), a conversation has begun in the literature that describes the nature of dashboards that marshal these types of real‐time data flows. 19 , 66 Exciting new areas of research that have more recently shown up in the literature (both within and outside of EM) include the incorporation of EHR data for trending or tracking workplace outcomes. 49 , 67 , 68 , 69 , 70 However, enthusiasm for the possibilities of digitized data should be tempered by the ongoing need for assessor judgment of important but nondigitizable aspects of resident performance, such as discernment, conscientiousness, and truthfulness. 45 Moreover, we must know what these data are actually capturing, since they are not always easy to interpret due to issues around interdependence of teammates or trainee–teacher dyads. 49 , 70 , 71 While digital systems can collect text data, meaning needs to be extracted in a way that ensures proper weighting of these important attributes. The theme around decision‐making processes and group work (e.g., clinical competence committees) also intersects with this body of literature related to data aggregation/visualization—and there is certainly much work to be done examining how the decision makers are affected by the data’s representation. Only just recently has a study describing the use of a design‐based model to develop a dashboard for clinical competency committees been published. 66 Clearly, our review shows that there is still ample room for continued innovation and scholarship in this area.

In this new era of increased WBA data, we must begin to think about how best to incorporate them into our existing workflows, but also be deliberate about how to do this with care and thoughtfulness. Some innovations will flow easily (e.g., real‐time feedback for more robust coaching), while other changes may require more planning and care to initiate (e.g., whether to attribute successes or failures of certain interventions to trainees, their attendings, or the team at large). Ellaway et al., 72 , 73 for example, have frequently written about these issues, and those looking to enter into this area of research should consider their thoughts and heed their warnings.

Finally, we found the validity framework analysis suggested by our consultations quite fascinating. This analysis allowed us to quickly see how much rigor has been added to the literature in recent years. We recommend that new scholars entering into the scholarly conversation around WBA data within EM may find our validity framework analyses useful to gain guidance as to the types of validity evidence they may want to highlight in their own work. Future research should also evaluate strategies for maximizing purposeful utilization of data by harnessing technology to better identify trends as well as presenting data in a more user‐friendly format. Other gaps that exist in the current literature within our field identified by our consultants in step 6 of our scoping review process included:

Data access and ethics around trainee data stewardship (e.g., Do our trainees know how the data is being stored? Are they aware of who owns the data about them? Who has access? Do trainees have a say in how this data can be used?)

Data utilization for purposes beyond single‐trainee decisions (e.g., How can we use this same data for program evaluation, faculty development, and quality improvement?).

LIMITATIONS

The authors would like to first remind readers that this review is the beginning of a scholarly conversation and not the end. While we have identified some works in the area of WBA aggregation and analysis within our field, there is certainly room for more work and clarification in this area. One of the other key limitations of our study is that much of the literature that currently exists concerning WBA data collection, aggregation, and visualization exists outside of EM. Many articles about these themes were found within our search but were excluded because they did not involve specific mention or provide guidance in EM. It is possible that some of the general literature may contain evidence that could guide EM faculty on these issues, but we felt that a concerted effort to focus on EM literature would help to shed light on opportunities for scholars in our specialty to explore and pursue. There are also some semantic nuances (e.g., feedback vs. assessment) that exist within the literature, and we anticipate that some key papers may have been relevant but used different terminology in their papers (and hence would have been excluded by our scoping review search and subsequent processes). 13 , 74

Moreover, the lead author of this paper (TC) would note that she has been involved in many of the papers cited within this paper, but the team has helped her engage in checking her reflexivity throughout the scoping review process at every step—including dual coding within paper selection and inviting in external assessment experts to ensure that no literature was missing. We value her expertise but have tried our best to ensure that her perspective and vantage point did not dominate this review and that we conducted a comprehensive initial search.

We are also aware that this field is evolving, with increasing numbers of papers in more recent years. Based on this trend, we suspect that a future review on these topics will yield more high‐quality evidence over time. That said, we are certain that more work would be welcome in this area, especially as we complete our transition to a CBME era.

CONCLUSIONS

This scoping review identified a trend toward more literature about workplace‐based assessment data collection, aggregation, and visualization within EM education, with the majority of the papers being published in the past 3 years. There is a burgeoning body of EM literature within this area of assessment, and those seeking to carve out a scholarship niche in this area can look to some of the authors in our review for guidance and mentorship. Ultimately, our scoping review suggests that more work must be done to provide greater evidence for how best to collect, process, and visualize the wealth of data from both quantitative and qualitative sources in the workplace.

Supporting information

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.

The authors thank Jennifer Westwick, AHIP, MSLIS, for her assistance with our initial search protocol. We also thank our external consultants on this paper for phase 6 of our review (Drs. Sandra Monteiro, Brent Thoma, and Andrew Hall).

AEM Education and Training. 2021;5:1–13

The authors have no relevant financial information or potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1. McGaghie WC, Miller GE, Sajid AW, Telder TV. Competency Based Curriculum in Medical Education: An Introduction. Public Health Papers No. 68. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1978. [PubMed]

- 2. Frank JR, editor. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework: Better Standards, Better Physicians, Better Care. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2005.

- 3. Frank JR. CanMEDS 2015 Physician Competency. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Batalden P, Leach D, Swing S, Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;2:103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kessler CS, Leone KA. The current state of core competency assessment in emergency medicine and a future research agenda: recommendations of the working group on assessment of observable learner performance. Acad Emerg Med 2012;19:1354–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beeson MS, Carter WA, Christopher TA, et al. Emergency medicine milestones. J Grad Med Educ 2013;5:5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santen SA, Rademacher N, Heron SL, Khandelwal S, Hauff S, Hopson L. How competent are emergency medicine interns for Level 1 milestones: who is responsible? Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:736–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sherbino J, Bandiera G, Doyle K, et al. The competency‐based medical education evolution of Canadian emergency medicine specialist training. Can J Emerg Med 2020;22:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. van Loon KA, Driessen EW, Teunissen PW, Scheele F. Experiences with EPAs, potential benefits and pitfalls. Med Teach 2014;36:698–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Durning SJ, Artino AR. Situativity theory: a perspective on how participants and the environment can interact: AMEE Guide no. 52. Med Teach 2011;33:188–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bok HG, Teunissen PW, Favier RP, et al. Programmatic assessment of competency‐based workplace learning: when theory meets practice. BMC Med Educ 2013;13:123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Qadri U, Arora VM. Comparison of male vs female resident milestone evaluations by faculty during emergency medicine residency training. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mueller AS, Jenkins T, Osborne M, Dayal A, O’Connor DM, Arora VM. Gender differences in attending physicians’ feedback for residents in an emergency medical residency program: a qualitative analysis. J Grad Med Educ 2017;577–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McConnell M, Sherbino J, Chan TM. Mind the gap: the prospects of missing data. J Grad Med Educ 2016;8:708–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li S, Sherbino J, Chan TM. McMaster Modular Assessment Program (McMAP) through the years: residents’ experience with an evolving feedback culture over a 3‐year period. AEM Educ Train 2017;1:5–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nousiainen MT, Caverzagie KJ, Ferguson PC, Frank JR. Implementing competency‐based medical education: what changes in curricular structure and processes are needed? Med Teach 2017;39:594–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chan T, Sherbino J. The McMaster Modular Assessment Program (McMAP). Acad Med 2015;90:900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chan T, Sebok‐Syer S, Thoma B, Wise A, Sherbino J, Pusic M. Learning analytics in medical education assessment: the past, the present, and the future. AEM Educ Train 2018;2:178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boscardin C, Fergus KB, Hellevig B, Hauer KE. Twelve tips to promote successful development of a learner performance dashboard within a medical education program. Med Teach 2017;40:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol Theory Pract 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chan TM, Dzara K, Dimeo SP, Bhalerao A, Maggio LA. Social media in knowledge translation and education for physicians and trainees : a scoping review. Perspect Med Educ 2020;9:20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thoma B, Camorlinga P, Chan TM, Hall AK, Murnaghan A, Sherbino J. A writer’s guide to education scholarship: quantitative methodologies for medical education research (part 1). CJEM 2018;20:125–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chan TM, Ting DK, Hall AK, et al. A writer’s guide to education scholarship: qualitative education scholarship (Part 2). Can J Emerg Med 2018;20:284–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chan TM, Thoma B, Hall AK, et al. CAEP 2016 academic symposium: a writer’s guide to key steps in producing quality education scholarship. CJEM 2017;19:S9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Murnaghan A, Weersink K, Thoma B, Hall AK, Chan T. The writer’s guide to education scholarship in emergency medicine: systematic reviews and the scholarship of integration (part 4). Can J Emerg Med 2018;20:626–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cook DA, Bordage G, Schmidt HG. Description, justification and clarification: a framework for classifying the purposes of research in medical education. Med Educ 2008;42:128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Beckman TJ, Cook DA. Developing scholarly projects in education: a primer for medical teachers. Med Teach 2007;29:210–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Frye AW, Hemmer PA. Program evaluation models and related theories: AMEE Guide No. 67. Med Teach 2012;34:e288–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yardley S, Dornan T. Kirkpatrick’s levels and education ‘evidence’. Med Educ 2012;46:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lineberry M.Validity and its threats. In: Downing SM, Haladyna TM, editors. Assessment in Health Professions Education. New York/London: Routledge, 2019:21–55.

- 31. Cook DA, Zendejas B, Hamstra SJ, Hatala R, Brydges R. What counts as validity evidence? Examples and prevalence in a systematic review of simulation‐based assessment. Adv Health Sci Educ 2014;19:233–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Messick S. Validity. In: Linn RL, editor. Educational Measurement. Third ed. New York: Macmillan, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ariaeinejad A, Samavi R, Chan TM, Doyle TE. A Performance Predictive Model for Emergency Medicine Residents. Proc 27th Annu Int Conf Comput Sci Softw Eng, 2017:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nagler J, Pina C, Weiner DL, Nagler A, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG. Use of an automated case log to improve trainee evaluations on a pediatric emergency medicine rotation. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29:314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Watling C, LaDonna KA, Lingard L, Voyer S, Hatala R. ‘Sometimes the work just needs to be done’: socio‐cultural influences on direct observation in medical training. Med Educ 2016;50:1054–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Egan R, Chaplin T, Szulewski A, et al. A case for feedback and monitoring assessment in competency‐based medical education. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;4:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Acai A, Li SA, Sherbino J, Chan TM. Attending emergency physicians’ perceptions of a programmatic workplace‐based assessment system: the McMaster Modular Assessment Program (McMAP). Teach Learn Med 2019;31:434–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Santen SA, Yamazaki K, Holmboe ES, Yarris LM, Hamstra SJ. Comparison of male and female resident milestone assessments during emergency medicine residency training: a national study. Acad Med 2020;95:263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Regan L, Cope L, Omron R, Bright L, Bayram JD. Do end‐of‐rotation and end‐of‐shift assessments inform clinical competency committees’ (CCC) decisions? West J Emerg Med 2018;19:121–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bounds R, Bush C, Aghera A, Rodriguez N, Stansfield RB, Santen SA. Emergency medicine residents’ self‐assessments play a critical role when receiving feedback. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1055–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beeson MS, Holmboe ES, Korte RC, et al. Initial validity analysis of the emergency medicine milestones. Acad Emerg Med 2015;22:838–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kennedy TJ, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard LA. ‘It’s a cultural expectation…’ The pressure on medical trainees to work independently in clinical practice. Med Educ 2009;43:645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chan TM, Sherbino J, Mercuri M. Nuance and noise: lessons learned from longitudinal aggregated assessment data. J Grad Med Educ 2017;9:724–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hobgood C, Promes S, Wang E, Moriarity R, Goyal DG. Outcome assessment in emergency medicine ‐ A beginning: Results of the Council of Emergency Medicine Residency Directors (CORD) Emergency Medicine Consensus Workgroup on Outcome Assessment. Acad Emerg Med 2008;15:267–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kennedy TJT, Regehr G, Baker GR, Lingard L. Point‐of‐care assessment of medical trainee competence for independent clinical work. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2008;83:89–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Perry M, Linn A, Munzer BW, et al. Programmatic assessment in emergency medicine: implementation of best practices. J Grad Med Educ 2018;10:84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martin L, Sibbald M, Brandt Vegas D, Russell D, Govaerts M. The impact of entrustment assessments on feedback and learning: trainee perspectives. Med Educ 2020;54:328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ariaeinejad A, Patel R, Chan TM, Samavi R. Using machine learning algorithms for predicting future performance of emergency medicine residents. Can J Emerg Physicians 2017;19(Suppl S1):S88. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shepherd L, Sebok‐Syer S, Lingard L, McConnell A, Sedran RJ, Dukelow A. Using electronic health record data to assess emergency medicine trainees independent and interdependent performance: a qualitative perspective on measuring what matters. Can J Emerg Phys. 2018;20:S106. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sherbino J, Bandiera G, Frank JR. Assessing competence in emergency medicine trainees: an overview of effective methodologies. CJEM 2008;10:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kwan J, Jouriles N, Singer A, et al. Designing assessment programmes for the model curriculum for emergency medicine specialists. CJEM 2015;17:462–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lockyer J, Carraccio C, Chan MK, et al. Core principles of assessment in competency‐based medical education. Med Teach 2017;39:609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dauphinee WD, Boulet JR, Norcini JJ. Considerations that will determine if competency‐based assessment is a sustainable innovation. Adv Health Sci Educ 2019;24:413–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tweed M, Wilkinson T. Student progress decision‐making in programmatic assessment: can we extrapolate from clinical decision‐making and jury decision‐making? BMC Med Educ 2019;19:176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Caretta‐Weyer H, Gisondi M. Design your clinical workplace to facilitate competency‐based education. West J Emerg Med 2019;20:651–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Garra G, Thode H. Synchronous collection of multisource feedback evaluations does not increase inter‐rater reliability. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dorfsman ML, Wolfson AB. Direct observation of residents in the emergency department: a structured educational program. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:343–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Competency by Design . Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. 2015. Available at: http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/common/documents/canmeds/cbd/what_is_cbd_e.pdf. Accessed Jul 2, 2020.

- 59. Chan TM, Sebok‐Syer SS, Sampson C, Monteiro S. Reliability and validity evidence for the quality of assessment for learning (QuAL) score. Acad Emerg Med 2018;25:S83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gottlieb M, Jordan J, Siegelman JN, Cooney R, Stehman C, Chan TM. Direct observation tools in emergency medicine: a systematic review of the literature. AEM Educ Train 2020;4:XXX–x. 10.1002/aet2.10519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CP, Eva KW. The hidden value of narrative comments for assessment. Acad Med. 2017;92:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ginsburg S, Eva K, Regehr G. Do in‐training evaluation reports deserve their bad reputations? A study of the reliability and predictive ability of ITER scores and narrative comments. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2013;88:1539–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CP, Eva KW, Lingard L. Cracking the code: residents’ interpretations of written assessment comments. Med Educ 2017;51:401–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Dudek NL, Marks MB, Bandiera G, White J, Wood TJ. Quality In‐training evaluation reports—does feedback drive faculty performance? Acad Med 2013;88:1129–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tremblay G, Carmichael PH, Maziade J, Grégoire M. Detection of residents with progress issues using a keyword‐specific algorithm. J Grad Med Educ 2019;11:656–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Thoma B, Bandi V, Carey R, et al. Developing a dashboard to meet competence committee needs: a design‐based research project. Can Med Educ J 2020;11:e16–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schumacher DJ, Holmboe ES, Van Der Vleuten C, Busari JO, Carraccio C. Developing resident‐sensitive quality measures: a model from pediatric emergency medicine. Acad Med 2018;93:1071–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Smirnova A, Sebok‐Syer SS, Chahine S, et al. Defining and adopting clinical performance measures in graduate medical education: where are we now and where are we going? Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2019;94:671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sebok‐Syer SS, Goldszmidt M, Watling CJ, Chahine S, Venance SL, Lingard L. Using electronic health record data to assess residents’ clinical performance in the workplace: the good, the bad, and the unthinkable. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll 2019;94:853–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sebok‐Syer SS, Chahine S, Watling CJ, Goldszmidt M, Cristancho S, Lingard L. Considering the interdependence of clinical performance: implications for assessment and entrustment. Med Educ 2018;52:970–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet 2010;376:1923–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ellaway RH, Pusic MV, Galbraith RM, Cameron T. Developing the role of big data and analytics in health professional education. Med Teach 2014;36:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ellaway RH, Topps D, Pusic M. Data, big and small: emerging challenges to medical education scholarship. Acad Med 2019;94:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med Educ 2019;53:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Supplement S1. Supplemental material.