Abstract

Objectives

Although psychological stress is a risk factor for oral diseases, there seems to be no review on work stress. This study aimed to review the evidence on the association between work stress and oral conditions, including dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss.

Design

A systematic review of published observational studies.

Data sources

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed and Scopus databases on 12 August 2020.

Study selection

Articles were screened based on the following inclusion criteria: published after 1966; in English only; epidemiological studies on humans (except case studies, reviews, letters, commentaries and editorials); and examined the association of work stress with dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from eligible studies. A quality assessment was conducted using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

Results

Of 402 articles identified, 11 met the inclusion criteria, and 1 study assessed the association of work stress with dental caries and periodontal status. Of 11 studies, 1 reported a non-significant association between work stress and dental caries; 8 of 9 studies reported a significant association between work stress and worse periodontal status; and 1 of 2 studies reported a significant association between work stress and tooth loss. Nine of 11 studies were cross-sectional, while the remaining 2 studies had unclear methodology. Only two studies were sufficiently adjusted for potential confounders. Eight studies assessed work stress but did not use the current major measures. Three studies were rated as fair, while eight studies had poor quality.

Conclusions

There is a lack of evidence on the association of work stress with dental caries and tooth loss. Eight studies suggested potential associations between periodontal status and work stress. Cohort studies using the major work stress measures and adjusting for the potential confounders are needed.

Keywords: occupational & industrial medicine, social medicine, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first systematic review to evaluate and summarise the literature on the association between work stress and oral conditions, including dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss.

This systematic review provides a comprehensive insight into the quality of the included papers.

The systematic literature search, screening and quality assessments were conducted by only one investigator.

A meta-analysis could not be conducted because of the heterogeneity of work stress measures and outcome definitions.

Introduction

Oral diseases, such as dental caries and periodontal disease, are a major health concern worldwide. The Global Burden of Disease Study has estimated that 2.3 billion individuals had untreated dental caries, 796 million had severe periodontal disease and 267 million had a complete loss of natural teeth in 2017.1 Dental caries is the destruction of dental hard tissues in the crowns and roots of the teeth.2 Periodontal diseases are chronic inflammatory conditions with disorders of the tissues surrounding and supporting the teeth.3 Tooth loss is mainly the consequence of dental caries and periodontal disease.2 3 Because oral diseases result in severe toothache and eating, sleeping, and communication disabilities,4 5 poor oral conditions can restrict work performance4 5 and create a significant economic burden.6 Indeed, work productivity loss due to oral conditions is estimated at US$187.61 billion annually.6 The necessity of preventing oral diseases for working adults is highlighted.

Since the 1990s, rapid changes in the global economy and the diverse markets have occurred, and psychological workplace stress has become more prevalent and severe, especially among industrialised countries.7 Indeed, Kivimäki et al reported a 15% prevalence of job strain measured using job content and demand control questionnaires from 13 European cohorts’ data (1985–2006).8 Besides, work stress can have profound effects on health. There is accumulating evidence of the risk of work stress on cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes and depression.9 10 Béjean and Sultan-Taïeb estimated that the work-related stress costs due to illnesses could range between €1167 million and €1975 million in France in 2000.11 Work stress affects workers’ health and productivity.

Psychological stress is recognised as a risk factor for dental caries and periodontal diseases. Psychological stress is related to oral diseases through immune system dysfunction, increased stress hormones, cariogenic bacterial counts and poor oral health behaviours.12 13 Work stress is strongly linked with psychological and physical health.9 10 Previous systematic reviews suggested potential associations of psychological stress with dental caries and periodontitis.14 15 However, there seems to be no review on the association between work stress and oral diseases. Today, work stress has become an increasingly serious problem. Besides, the number of women in the workforce and dual-earner families has been increasing.16 A wide range of populations can suffer the risk of oral diseases from exposure to work stress. Thus, the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate and summarise the literature on the association between work stress and oral conditions, including dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss. We set the following review question: Is work stress associated with dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss among working adults?

Methods

The reporting of this systematic review conforms to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.17 18 We also followed the Conducting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies of Etiology guidance19 and the reporting of Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.20 The protocol of this systematic review was not registered.

Eligibility criteria

Published studies were eligible if they: (1) were published in English; (2) were epidemiological studies on humans (except case studies, reviews, letters, commentaries and editorials); and (3) examined the association of work stress with dental caries, periodontal status and tooth loss.

Information sources and searches

On 12 August 2020, we identified potentially relevant published studies in PubMed (1966–12 August 2020) and Scopus (1966–12 August 2020) databases. As PubMed and Scopus have only data back to 1966, we focused on articles published after 1966. We used the following script to obtain a wide range of literature: (“job strain” OR “effort reward”) AND (dental OR oral); (“job stress” OR “work stress” OR “occupational stress”) AND (dental OR oral). The details of the search strategies for each database are shown in online supplemental table 1. Besides, we manually hand-searched for potentially suitable studies through the reference lists of identified articles and Google Scholar. After excluding duplicate articles, one author (YSato) assessed the titles and abstracts according to the aforementioned criteria. Then, eligible studies were selected for the full-text review.

bmjopen-2020-046532supp001.pdf (34.2KB, pdf)

Data extraction

One author (YSato) extracted the following information from each eligible study: (1) name of the first author; (2) study design; (3) study location (country); (4) number of participants and work-related characteristics; (5) exposure and its measurements; (6) outcome and its measurements; (7) age range and proportion of women; (8) covariates included in the adjusted models and (9) the main results. The results were shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies on work stress and oral conditions

| Author’s name (year of publication) | Study design | Study location | Exposure (work stress) | Outcome | Number of participants | Mean age of the participants and proportion of women | Covariates | Main results |

| Dental caries | ||||||||

| Marcenes and Sheiham (1992)27 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | Karasek job strain model | DMFS index (number of decayed (D), missing (M), and filled (F) teeth surfaces per person) | 164 male paid workers aged from 35 to 44 years | Mean age=41.2 (SD=2.2) 0% |

Marital quality, toothbrushing frequency, sugar consumption, age, years of residence, type of toothpaste, frequency of dental attendance and socioeconomic status | Work mental demand: coefficients=0.19 (95% CI=−0.91 to 1.29) Work control: coefficients=0.87 (95% CI=−0.18 to 1.91) Work variety: coefficients=−0.06 (95% CI=−1.57 to 1.45) from a linear regression analysis |

| Periodontal status | ||||||||

| Marcenes and Sheiham (1992)27 | Cross-sectional | Brazil | Karasek job strain model | The presence or absence of teeth either with gums bleeding on probing or with pockets was used. The indicator was labelled as ‘complete absence of teeth with gums bleeding on probing and with pockets’, and ‘presence of any tooth with gums bleeding on probing or pockets’ | 164 male paid workers aged from 35 to 44 years (16 workers were excluded from 164 participants due to missing values and edentulous) | Mean age=41.2 (SD=2.2) 0% |

Marital quality, toothbrushing frequency, sugar consumption, age, years of residence, type of toothpaste, frequency of dental attendance and socioeconomic status | Work mental demand: OR=1.22 (95% CI=1.06 to 1.37) Work control: OR=0.97 (95% CI=0.88 to 1.07) Work variety: OR=0.99 (95% CI=0.85 to 1.16) from a logistic regression analysis |

| Freeman and Goss (1993)23 | Unknown | Not reported | Occupational Stress Indicator | Mean increases in pocket depth | 10 women and 8 men from the head office of a large company | Mean age=39 55.6% |

Unknown | Type A behaviour: coefficients=0.41 (p=0.003) Work environment (organisation/climate): coefficients=−0.34 (p=0.007) (statistical model was not reported) |

| Linden et al (1996)28 | Unknown | UK | Occupational Stress Indicator assessed at the second examination | Changes in clinical attachment level after an interval of 5.5 (SD 0.6) years | 23 employed regular dental attendees aged between 20 and 50 years who had moderate or established periodontitis (13 men and 10 women) | Mean age=41.1 (SD=7.3) 43.5% |

Age and social class of the household | Job satisfaction: coefficients=−0.014 (p <0.01) Type A: coefficients=0.026 (p<0.05) Locus of control: coefficients=−0.035 (p≥0.05) (statistical model was not reported) |

| Genco et al (1999)29 | Cross-sectional | USA | Problems of Everyday Living Scale of Pearlin and Schooler | Severity of Attachment Loss Healthy (0–1 mm clinical attachment level), low (1.1–2.0 mm), moderate (2.1–3.0 mm), high (3.1–4.0 mm) and severe (4.1–8.0 mm) Severity of Alveolar Bone Loss Healthy (0.4–1.9 mm alveolar crestal height), low (2.0–2.9 mm), moderate (3.0–3.9 mm) and severe (≥4.0 mm) |

1426 inhabitants aged 25–74 years (741 women and 685 men) *working status was unknown |

Mean age=48.9 (SD=13.9) 52.0% |

Age, gender and levels of smoking | Job strain score among Attachment Loss categories (mean±SE) Healthy: 2.12±0.05 Low: 2.09±0.02 Moderate: 2.16±0.02 High: 2.09±0.05 Severe: 2.22±0.05 (non-significant) from analysis of covariance Job strain score among Alveolar Bone Loss categories (mean±SE) Healthy: 2.12±0.02 Low: 2.10±0.03 Moderate: 2.09±0.04 Severe: 2.19±0.04 (non-significant) from analysis of covariance |

| Akhter et al (2005)30 | Cross-sectional | Japan | Life Events Scale (yes or no) |

Those with mean clinical attachment loss <1.5 mm were assigned to a non-diseased group and those with mean clinical attachment loss ≥1.5 mm were assigned to a diseased group | 1089 employed and unemployed residents ranging in age from 18 to 96 years of a farming village in the northernmost island of Japan (531 men and 558 women) | Mean age=55.0 (SD=1.7) 51.2% |

Age, gender, employment status, smoking behaviour, stress within 1 month, self-health-related stress, family health-related stress, frequency of dental attendance, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus | Job stress (reference: no): OR=1.71 (95% CI=1.10 to 2.67) from a logistic regression analysis |

| Talib Bandar (2009)22 | Cross-sectional | Iraq | Life Events Scale (yes or no) |

Gingival Index, probing pocket depth (PPD), bleeding on probing and clinical attachment level | 64 working dental patients of both genders with ages ranging from 23 to 65 years | Mean age and sex were not reported | None | The mean Gingival Index yes=1.851 and no=1.586 (p>0.05) Total mean percentage of sites with PPD ≥4 mm yes=6.277% and no=4.762% (p<0.05) Total mean bleeding on probing yes=41.534% and no=32.137% (p>0.05) The mean of the clinical attachment level yes=2.837 and no=2.275 (p>0.05) (all p values from t-test) |

| Mahendra et al (2011)31 | Cross-sectional | India | An Occupational Stress Index of Srivastava, A K and Singh, A P | Control group (n=30): PPD ≤3 mm Test group 1 (n=40): at least four sites with PPD >4 mm and ≤6 mm Test group 2 (n=30): at least four sites with PPD >6 mm |

110 police personnel aged 35–48 years with moderate or established periodontitis | Mean age (SD); control group: 40.23 (3.46); test group 1: 40.42 (3.54); test group 2: 41.18 (3.78) Sex was not reported |

None | Mean Occupational Stress Index Score (SD) Control: 79.53 (23.57) Test group 1: 133.68 (33.23) Test group 2: 158.13 (32.44) p<0.001 (p values from ANOVA with the Scheffe test) |

| Ramji (2011)24 | Cross-sectional | India | Self-reported job stress (having or not) | Community Periodontal Index and Treatment Needs protocol (a tooth scored 3 or 4 indicating increased pocket depth of over 2 mm indicates presence of periodontitis) |

198 industrial labour full-time workers from a small-scale sector (SS) and 68 from a large-scale sector (LS) between the ages of 18 and 64 years | Age groups (SS (n=130), LS (n=68)) 15–19 years: 0%, 1% 20–29 years: 38%, 60% 30–44 years: 45%, 20% 45–64 years: 17%, 19% Sex was not reported |

None | Having self-reported job stress: OR=7.5 (95% CI=3.7 to 15.02) from a logistic regression analysis |

| Islam et al (2019)32 | Cross-sectional | Japan | Brief Job Stress Questionnaire developed by referring the demand–control– support model in Japan (low stress, high stress-high coping, and high stress-low coping) *coping was assessed using a questionnaire developed by a Japanese company |

No inflammation of the gingiva or redness and/or swelling of the interdental papilla without gingival recession was classified as non-periodontitis, and any redness and/or swelling in the gingiva with gingival recession and/or tooth mobility was classified as periodontitis, based on visual inspection by dentists | 738 workers of a Japanese crane manufacturing company (92 were women) | Mean age=40.7 (SD=10.5) 12.5% |

Age, gender, daily flossing, regular dental check-up, body mass index, sleeping duration, current smoker, daily alcohol drinking, monthly overtime work and worker type | High stress-high coping: OR=0.30 (95% CI=0.14 to 0.66) High stress-low coping: OR=2.79 (95% CI=1.05 to 7.43) (reference: low stress) from a logistic regression analysis |

| Tooth loss | ||||||||

| Hayashi et al (2001)33 | Cross-sectional | Japan | Karasek job strain model (high job demand and low control and other categories) |

Tooth loss via oral examination (≥4 teeth lost and ≤3 teeth lost) |

252 male workers employed at a manufacturing company aged 20–59 years | Mean age=38.7 (SD=11.0) 0% |

Age, type A behaviour, alexythymia, depression, job satisfaction and life satisfaction | High job demand and low control (reference: other categories): OR=1.2 (95% CI=0.40 to 3.42) from a logistic regression analysis |

| Sato et al (2020)34 | Cross-sectional | Japan | Effort–reward imbalance model (having or not) |

Self-reported tooth loss Having tooth loss or not (=no experience of tooth loss) |

1195 employees aged 25–50 years old who work 20 hours per week or more (women=569) | Median age=37 (1st and 3rd quartiles=31 and 43) 48% |

Age, sex, marital status, annual household income, years of education, employment status, occupation, working hours per week, job position, company size, body mass index and smoking status | High effort–reward imbalance ratio: prevalence ratio=1.20 (95% CI=1.01 to 1.42) from Poisson regression models with a robust error variance |

ANOVA, analysis of variance.

Quality assessment

We used the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies to assess the quality of included studies.21 This tool includes 14 questions for evaluating the internal validity of a study and these questions are documented in the footnote of table 2. For each question, one author (YSato) rated them as yes, no or other (including cannot determine, not reported and not applicable). The overall quality rating for the study was regarded as good if all the domains were assessed favourably.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included studies

| Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Quality rating (good, fair or poor) | |

| Marcenes and Sheiham27 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Yes | Fair |

| Freeman and Goss23 | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Linden et al28 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Genco et al29 | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Akhter et al30 | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | No | No | NA | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Talib Bandar22 | Yes | Yes | NR | No | No | No | No | NA | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Mahendra et al31 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Ramji24 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Islam et al32 | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | No | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Poor |

| Hayashi et al33 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA | No | Fair |

| Sato et al34 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | NA | Yes | No | Yes | No | NA | Yes | Fair |

Q1. Was the research question or objective in this paper clearly stated?

Q2. Was the study population clearly specified and defined?

Q3. Was the participation rate of eligible persons at least 50%?

Q4. Were all the subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)? Were inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study prespecified and applied uniformly to all participants?

Q5. Was a sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimates provided?

Q6. For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured?

Q7. Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?

Q8. For exposures that can vary in amount or level, did the study examine different levels of the exposure as related to the outcome (eg, categories of exposure, or exposure measured as continuous variable)?

Q9. Were the exposure measures (independent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?

Q10. Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time?

Q11. Were the outcome measures (dependent variables) clearly defined, valid, reliable and implemented consistently across all study participants?

Q12. Were the outcome assessors blinded to the exposure status of participants?

Q13. Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less?

Q14. Were key potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

NA, not applicable; NR, not reported.

Synthesis of results

A meta-analysis could not be conducted because of the heterogeneity of work stress measures and outcome definitions.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved.

Results

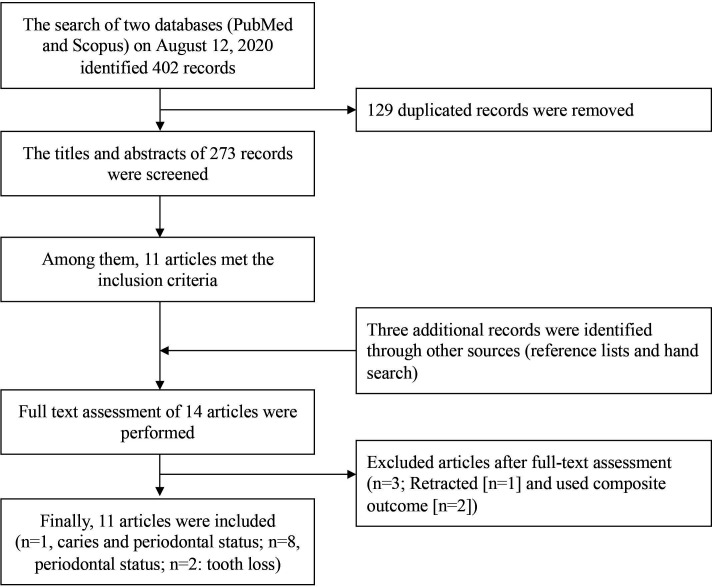

Figure 1 presents the flow diagram of information through the phases of the systematic review. Of the 402 articles identified in PubMed and Scopus databases, 129 duplicated articles were removed, the titles and abstracts of 273 were screened, and 11 met the eligibility criteria. Three more articles identified through reference lists and hand-search were added. One article was identified by a hand-search using Google Scholar,22 one was from a reference list23 and the third was an article24 plagiarised by a retraction paper. Because the article24 which was plagiarised by the retracted one was published officially and has not been retracted, it was included in our references. After full-text assessments of 14 articles, 3 were excluded due to retraction (n=1) and the use of composite outcomes including dental caries and periodontal status (n=2).25 26 Finally, 11 articles were included in this systematic review.22–24 27–34

Figure 1.

Flow of search strategy and selection of studies for a systematic review.

Study characteristics of individual studies

Table 1 shows the 12 summaries from the 11 studies. One of 11 studies reported on dental caries and periodontal status,27 8 reported on periodontal status22–24 28–32 and 2 reported on tooth loss.33 34 Three studies were conducted in Japan,30 32–34 two in India,24 31 and one each in the UK,28 the USA,29 Brazil27 and Iraq.22 One study did not report on the study location.28 The sample size varied from 18 to 1426 among included studies. In one study, working status was not reported.29 One study included employed and unemployed participants.30 Two studies did not include women,27 33 and three did not report on sex.22 24 31

Three studies assessed work stress using the current major measures (job demand–control model and effort–reward imbalance model).27 33 34 Work stress was assessed using the Karasek job strain model,27 33 the Effort–Reward Imbalance model,34 the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire developed by referring to the demand–control–support model in Japan,32 a self-reported job stress,24 the Occupational Stress Indicator,23 28 an Occupational Stress Index by Srivastava and Singh,31 the Life Events Scale,22 30 and the Problems of Everyday Living Scale by Pearlin and Schooler.29

Three studies presented only descriptive statistics.22 29 31 Eight studies performed regression analyses23 24 27 28 30 32–34; but two of the eight studies did not report the types of a regression modelling used.23 28 Only two studies sufficiently adjusted for potential confounders such as socioeconomic status and work-related variables.27 34

Dental caries and work stress

One study reported the cross-sectional association between work stress and dental caries, which included 164 paid male workers aged 35–44 years in Brazil.27 Work stress was assessed according to the Karasek job strain model.35 Dental caries status was assessed using the DMFS index (the number of decayed (D), missing (M) and filled (F) teeth surfaces per person). After adjusting for covariates, one-point increases in the work mental demand, work control, and work variety scores were associated with 0.19 (95% CI=−0.91 to 1.29), 0.87 (95% CI=−0.18 to 1.91), and −0.06 (95% CI=−1.57 to 1.45) increases in the DMFS index, respectively, in a multivariable regression analysis. Consequently, this study reported a non-significant association between work stress and dental caries.27

Periodontal status and work stress

Eight of nine studies reported a significant association between work stress and worse periodontal status.22–24 27–32 The measurements of periodontal status varied across the included studies. The measurements included probing pocket depth,22 23 31 clinical attachment level,22 28 29 alveolar bone loss,29 Gingival Index,22 bleeding on probing,22 the Community Periodontal Index and Treatment Needs protocol,24 and a composite outcome, including these measures.27 32 Eight studies assessed periodontal status based on oral examination with probe, but one study was based on only visual inspection by dentists.32

Among the nine studies, two studies had unclear methodology; therefore, they were categorised as unknown.23 28 Freeman and Goss assessed work stress and periodontal status over a 12-month period.23 However, they did not clearly report when work stress and periodontal status variables were assessed and how they were used in the statistical models. Linden et al followed up patients for 5.5 years, but work stress was only assessed at the follow-up examination, not at the baseline survey.28

Among the remaining seven studies, after excluding the above two studies, three studies presented only descriptive statistics.22 29 31 The remaining four papers reported significant associations following regression analyses.24 27 30 32 However, Akhter et al used general stress questions not specific to work stress and included non-working adults.30 Islam et al used the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire derived from the demand–control–support model in Japan, and periodontal status was assessed based on the visual inspection by dentists.32 Important potential confounders, such as socioeconomic status and work-related variables, were not included. Ramji assessed work stress using a single job stress question and did not adjust for covariates in the statistical models.24 Marcenes and Sheiham reported a significant association between periodontal status and work stress.27 Periodontal status was assessed by the presence or absence of gums bleeding on probing or with pockets. The authors divided periodontal measures into groups based on ‘complete absence of teeth with gums bleeding on probing and with pockets,’ or ‘the presence of any tooth with gums bleeding on probing or pockets,’ and defined the latter as those with periodontal disease. After adjusting for covariates, one-point increases in work mental demand scores, work control scores, and work variety scores were associated with ORs of 1.22 (95% CI=1.06 to 1.37), 0.97 (95% CI=0.88 to 1.07), and 0.99 (95% CI=0.85 to 1.16), respectively, for having periodontal disease, in a logistic regression model.

Tooth loss and work stress

Two studies on the association between work stress and tooth loss were identified. One of the two reported a significant association between work stress and tooth loss.33 34 Hayashi et al reported the association between work stress, assessed using the Karasek job strain model and tooth loss.33 A total of 322 male workers employed at a manufacturing company were included. They dichotomised the number of tooth loss into ≤3 and ≥4. After adjusting for covariates, high job demand and low control conditions were associated with high odds of having ≥4 teeth loss but not significant (OR=1.2 (95% CI=0.40 to 3.42)). This study did not adjust for the important potential confounders such as socioeconomic status and work-related variables. Sato et al reported the association between work stress, assessed using the effort–reward imbalance model and self-reported tooth loss.34 After adjusting for covariates including socioeconomic status and work-related variables, a high effort–reward imbalance ratio was significantly associated with a high prevalence of ≥1 tooth loss (prevalence ratio=1.20 (95% CI=1.01 to 1.42)).

Study quality

Table 2 presents the results of the quality assessments for each study. Eight studies (73%) had poor quality, while three (27%) were rated as fair. None of the studies addressed questions 6 (‘For the analyses in this paper, were the exposure(s) of interest measured prior to the outcome(s) being measured?’); 7 (‘Was the timeframe sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?’) and 10 (‘Was the exposure(s) assessed more than once over time?’), because all the studies were cross-sectional or the study design was unclear.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review to evaluate and summarise the existing literature on the associations between work stress and oral conditions. As our findings showed, only one study reported on dental caries and periodontal status, nine on periodontal status and two on tooth loss. Based on the findings of this review, the evidence is lacking on the association of work stress with dental caries and tooth loss. Eight of nine studies reported the significant associations between multiple periodontal measures and work stress.

Limitations of the review

This systematic review has four limitations. First, the systematic literature search, screening and quality assessments were conducted by only one investigator. A single screening could miss more studies than a double screening.36 Second, only English-language literature was included. Although a systematic review found no bias due to English-language restriction in systematic reviews,37 this review might include bias. Third, there was no protocol for this systematic review. A priori systematic review protocol registration provides the rigour and trustworthiness of the reviews.38 This might weaken the rigour and trustworthiness of our review. Finally, a meta-analysis could not be conducted owing to the heterogeneity of the included studies. Work stress was assessed using varied measures. Particularly, only a few studies used the current major measures of work stress. Indicators of periodontal status were also varied. No study used valid epidemiological definitions for periodontal disease as the outcome. The cut-off points differed between the two studies on tooth loss and work stress. Besides, there was only one study on dental caries and work stress. These limitations hindered us from performing a meta-analysis.

Dental caries and work stress

We found only one study on the cross-sectional association between work stress and dental caries.27 The conclusion was that there was no significant association between work stress and dental caries. However, since the sample size was relatively small (n=164), there is the possibility of a false negative association. Besides, each subscale of the Karasek job strain model was simultaneously included in the statistical model. Generally, in the Karasek job strain model, the recommendation is to use four categories of job strain generated by the interaction of the subscales: high-strain jobs, active jobs, low-strain jobs and passive jobs.9 Due to the above treatments of the subscales, it is possible that the association was underestimated. Additionally, as there was no cohort study, we could not assess the prospective associations. Considering the above limitations, it was difficult to determine whether work stress is associated with dental caries. A further study should include a cohort design and a relatively large sample size with appropriate work stress measures.

Periodontal status and work stress

Nine studies reported on the association between work stress and periodontal status.22–24 27–32 However, the outcome measures were varied across the included studies. Although there are the accepted epidemiological definitions of periodontitis according to the European Workshop in Periodontology and the Centers for Disease Control/American Academy of Periodontology,39 40 there was no study that used the definitions. It means that the included studies reported the associations between work stress and periodontal measures, not periodontal disease. In addition, the measurement of work stress measured also varied across studies. Each measure assessed different dimensions of work stress.41 Due to the heterogeneity of exposures and outcomes, we could not conduct a meta-analysis.

Of the nine studies, only one study adjusted for the potential confounders, such as socioeconomic status and work-related variables.27 Besides, no cohort study was found. The failure to adjust for the confounders and consider the induction time weakens the research evidence. However, despite the above limitations, the consistent association between work stress and worse periodontal status is noteworthy. To verify the current results, a further cohort study using the validated definitions of periodontal disease and current measurements of work stress, in addition to adjusting for the potential confounders, should be performed.

Tooth loss and work stress

Two studies on the association between work stress and tooth loss were identified. Hayashi et al’s study included only male workers employed at one manufacturing company.33 In contrast, Sato et al’s study included active workers sampled from a general population.34 However, the response rate was relatively low (32%). The generalisability of both studies could be limited.

The two studies had different cut-off points of tooth loss. Hayashi et al’s study used the cut-off point of more than four teeth lost. The cut-off point is higher than the mean number of teeth loss (at 25–34, 35–45, 46–54 and 55–64 years=0.16, 0.58, 1.48 and 4.00, respectively) reported by the national statistical surveys.42 This study targeted severe cases only. In Sato et al’s study, the outcome was the loss of at least more than one tooth. However, this outcome relied on self-reported answers; therefore, self-reported bias might exist.

Both studies showed an increased risk of tooth loss, although only one of the two studies reported a significant association between work stress and tooth loss. However, due to the above limitations, it is difficult to derive any form of conclusion. In the future, a cohort study including general workers should be conducted to confirm these findings.

Conclusions

Based on the findings, this systematic review suggests a lack of evidence on the association of work stress with dental caries and tooth loss. Although eight of the nine studies reported significant associations between multiple periodontal measures and work stress, no study used valid epidemiological definitions of periodontal disease. For future research, well-designed cohort studies including potential confounding factors and the use of generally accepted measurements of work stress and periodontal disease are needed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: YSato contributed to the acquisition and the interpretation of data and drafting of the work. YSaijo and EY revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors contributed to the conception and design of the work, approved the final version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This study was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant number JP19K19306).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. Not applicable.

References

- 1.GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators, Bernabe E, Marcenes W, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J Dent Res 2020;99:362–73. 10.1177/0022034520908533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17030. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kinane DF, Stathopoulou PG, Papapanou PN. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17038. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheiham A, Croog SH. The psychosocial impact of dental diseases on individuals and communities. J Behav Med 1981;4:257–72. 10.1007/BF00844251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisine ST. The impact of dental conditions on social functioning and the quality of life. Annu Rev Public Health 1988;9:1–19. 10.1146/annurev.pu.09.050188.000245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Righolt AJ, Jevdjevic M, Marcenes W, et al. Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. J Dent Res 2018;97:501–7. 10.1177/0022034517750572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lundberg U, Cooper C. The new workplace in a rapidly changing World. : The science of occupational health: stress, psychobiology, and the new world of work. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010: 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kivimäki M, Nyberg ST, Batty GD, et al. Job strain as a risk factor for coronary heart disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet 2012;380:1491–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60994-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman L, Kawachi I, Theorell T. Working conditions and health. : Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014: 153–81. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lundberg U, Cooper C. Stress-related health problems. : The science of occupational health: stress, psychobiology, and the new world of work. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010: 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Béjean S, Sultan-Taïeb H. Modeling the economic burden of diseases imputable to stress at work. Eur J Health Econ 2005;6:16–23. 10.1007/s10198-004-0251-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabbah W, Gomaa N, Gireesh A. Stress, allostatic load, and periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2018;78:154–61. 10.1111/prd.12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomaa N, Glogauer M, Tenenbaum H, et al. Social-biological interactions in oral disease: a ‘cells to society’ view. PLoS One 2016;11:e0146218. 10.1371/journal.pone.0146218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tikhonova S, Booij L, D’Souza V, et al. Investigating the association between stress, saliva and dental caries: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health 2018;18:41. 10.1186/s12903-018-0500-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Castro MML, Ferreira RdeO, Fagundes NCF, et al. Association between psychological stress and periodontitis: a systematic review. Eur J Dent 2020;14:171–9. 10.1055/s-0039-1693507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lundberg U, Cooper C. Introduction: History of work and health. : The science of occupational health: stress, psychobiology, and the new world of work. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dekkers OM, Vandenbroucke JP, Cevallos M, et al. COSMOS-E: guidance on conducting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies of etiology. PLoS Med 2019;16:e1002742. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 2000;283:2008–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Institutes of Health . Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, 2014. Available: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Accessed 17 Sep 2020].

- 22.Talib Bandar K. The association between periodontal disease and job stress in Baghdad City. J Kerbala Univ 2009;5:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman R, Goss S. Stress measures as predictors of periodontal disease – a preliminary communication. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993;21:176–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00748.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramji R. Assessing the relationship between occupational stress and periodontitis in industrial workers. PHD thesis, Umeå international school of public health 2011.

- 25.Yoshino K, Suzuki S, Ishizuka Y, et al. Relationship between job stress and subjective oral health symptoms in male financial workers in Japan. Ind Health 2017;55:119–26. 10.2486/indhealth.2016-0120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capurro DA, Davidsen M. Socioeconomic inequalities in dental health among middle-aged adults and the role of behavioral and psychosocial factors: evidence from the Spanish National Health Survey. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:34. 10.1186/s12939-017-0529-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcenes WS, Sheiham A. The relationship between work stress and oral health status. Soc Sci Med 1992;35:1511–20. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90054-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linden GJ, Mullally BH, Freeman R. Stress and the progression of periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 1996;23:675–80. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.1996.tb00593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genco RJ, Ho AW, Grossi SG, et al. Relationship of stress, distress and inadequate coping behaviors to periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1999;70:711–23. 10.1902/jop.1999.70.7.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akhter R, Hannan MA, Okhubo R, et al. Relationship between stress factor and periodontal disease in a rural area population in Japan. Eur J Med Res 2005;10:352–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahendra L, Mahendra J, Austin RD. Stress as an aggravating factor for periodontal diseases. J Clin Diagn Res 2011;5:889–93. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Islam MM, Ekuni D, Yoneda T, et al. Influence of occupational stress and coping style on periodontitis among Japanese workers: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3540. 10.3390/ijerph16193540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hayasht N, Tamagawa H, Tanaka M, et al. Association of tooth loss with psychosocial factors in male Japanese employees. J Occup Health 2001;43:351–5. 10.1539/joh.43.351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sato Y, Tsuboya T, Aida J, et al. Effort-reward imbalance at work and tooth loss: a cross-sectional study from the J-SHINE project. Ind Health 2020;58:26–34. 10.2486/indhealth.2018-0226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 1979;24:285–308. 10.2307/2392498 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waffenschmidt S, Knelangen M, Sieben W, et al. Single screening versus conventional double screening for study selection in systematic reviews: a methodological systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2019;19:132. 10.1186/s12874-019-0782-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrison A, Polisena J, Husereau D, et al. The effect of English-language restriction on systematic review-based meta-analyses: a systematic review of empirical studies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2012;28:138–44. 10.1017/S0266462312000086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647. 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Page RC, Eke PI. Case definitions for use in population-based surveillance of periodontitis. J Periodontol 2007;78:1387–99. 10.1902/jop.2007.060264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tonetti MS, Claffey N, European Workshop in Periodontology group C . Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. group C consensus report of the 5th European workshop in Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol 2005;32:210–3. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00822.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leka S, Jain A, World Health Organization . Health impact of psychosocial hazards at work: an overview, 2010. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44428

- 42.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (Japan) . Dental diseases survey, 2016. Available: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/62-17b.html [Accessed 12 Mar 2021].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-046532supp001.pdf (34.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. Not applicable.