Abstract

Background

The host’s immune system develops in equilibrium with both cellular self-antigens and non-self-antigens derived from microorganisms which enter the body during lifetime. In addition, during the years, a tumor may arise presenting to the immune system an additional pool of non-self-antigens, namely tumor antigens (tumor-associated antigens, TAAs; tumor-specific antigens, TSAs).

Methods

In the present study, we looked for homology between published TAAs and non-self-viral-derived epitopes. Bioinformatics analyses and ex vivo immunological validations have been performed.

Results

Surprisingly, several of such homologies have been found. Moreover, structural similarities between paired TAAs and viral peptides as well as comparable patterns of contact with HLA and T cell receptor (TCR) α and β chains have been observed. Therefore, the two classes of non-self-antigens (viral antigens and tumor antigens) may converge, eliciting cross-reacting CD8+ T cell responses which possibly drive the fate of cancer development and progression.

Conclusions

An established antiviral T cell memory may turn out to be an anticancer T cell memory, able to control the growth of a cancer developed during the lifetime if the expressed TAA is similar to the viral epitope. This may ultimately represent a relevant selective advantage for patients with cancer and may lead to a novel preventive anticancer vaccine strategy.

Keywords: antigens, immunotherapy, immunity, cellular, CD8-positive T-lymphocytes, vaccination

Introduction

Therapeutic cancer vaccines have been developed and evaluated in clinical trials targeting different tumor settings and involving thousands of patients with cancer. The observed overall rate of clinical benefit is a rather disappointing 20%.1–6

One of the factors responsible for such limited efficacy is represented by the quality of target tumor antigens identified over the years and included in the vaccine (https://caped.icp.ucl.ac.be/Peptide/list).7 Indeed, tumor antigens need to be sufficiently distinct from self-antigens to break the immunological tolerance that physiologically blocks undesired autoimmune reactivity against normal cells.

Tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) are shared among patients with the same malignancy.8–11 They include different type of antigens, namely aberrantly overexpressed self-antigens in tumor cells compared with normal cells, cell lineage differentiation antigens, which are normally not expressed in adult tissue12–14 and cancer/germline antigens (also known as cancer/testis), which are normally expressed only in immune-privileged germline cells.15–19

Consequently, the main drawback of using overexpressed or cell lineage differentiation TAAs in cancer immunotherapy is the induction of T cells with low-affinity receptors (TCRs), which are unable to mediate effective antitumor responses.20 21 Alternatively, they may be unable to elicit an immune response given that T cells specific for these self-antigens may have been removed from the immune repertoire by central and peripheral tolerance.22

To improve the immunogenicity of TAAs, peptides have been modified (heteroclitic peptides) to increase their affinity and binding to the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC)-I.23 Such modified peptides have been shown to break the immunological tolerance, inducing a more potent CD8+ T cell response able to recognize the native peptide and kill tumor cells.24–28 Indeed, it has been proven that TCRs are able to cross-react with multiple pMHCs characterized by narrow sequence differences.29–31

An alternative strategy would be the identification of natural analog peptides, sharing sequence homology with TAAs and able to induce T cells with cross-reacting TCRs for an improved antitumor cytotoxic effect.

In this respect, scattered data suggest that antigens derived from pathogens (pathogen-associated antigens, PaAs) may share sequence homology with TAAs and elicit cross-reacting CD8+ T cell responses, driving the fate of cancer development, progression and eventually response to therapy. Different research groups have reported that patients with cancer with tumor lesions expressing tumor antigens with high similarity to pathogens may have a better clinical outcome.32–36 We have recently shown that mutated neoantigens may show >50% sequence similarity to PaAs and the central TCR-facing residues can be identical. Paired neoantigens and PaAs were shown to elicit cross-reacting T cells in immunized mice and to be cross-recognized by peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from a long-term surviving patient with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).37 Furthermore, mice prevaccinated with viral epitopes with high similarity to tumor epitopes have been shown to better control tumor growth compared with naïve mice.

Based on such reported observations, and considering the large number of non-self-PaAs to which humans are exposed during their lifetime, we screened all the TAAs described in the literature and publicly available at cancer peptide database (https://caped.icp.ucl.ac.be/Peptide/list) for sequence homology to viral sequences. Surprisingly, several such homologies have been found. Moreover, structural similarities between paired TAAs and viral peptides as well as comparable patterns of contact with HLA and TCR α and β chains have been observed. Therefore, viral antigens and tumor antigens may elicit cross-reacting CD8+ T cell responses and an antiviral T cell memory may be able to control the growth of a cancer developed during the lifetime, if the expressed TAA is similar to the viral epitope. This may ultimately represent a relevant selective advantage for patients with cancer and may lead to a novel preventive anticancer vaccine strategy.

Materials and methods

Epitope prediction analysis

All the peptides selected in the study were predicted with the NetMHCpan V.4.1 and the NetMHCstabpan V.1.0 predictive algorithms (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?NetMHCpan-4.1; https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?NetMHCstabpan-1.0).

The peptides deposited at the cancer antigenic peptide database (https://caped.icp.ucl.ac.be/Peptide/list) were used to interrogate NetMHCpan V.4.1 tool.38 Nanomer peptides for the four most prevalent MHC class I HLA-A*0101, 0201, 0301 and 2402 alleles (http://www.allelefrequencies.net) have been selected with a predicted affinity value <100 nM (strong binders, SBs).

Likewise, viral nanomer peptides identified by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) homology search were used to interrogate NetMHCstabpan V.1.0 tool39 for the four most prevalent MHC class I HLA-A*0101, 0201, 0301 and 2402 alleles. SB peptides were selected with a predicted affinity value <100 nM and stability >1 hour.

BLAST homology search

The TAAs selected as SB according to NetMHCpan V.4.1 prediction tool have been submitted to BLAST for a protein homology search against viral sequences (Viruses—taxid:10239) within the non-redundant protein sequences database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). Homologous viral protein sequences have been extracted from the protein database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and epitope prediction has been performed with the NetMHCstabpan V.1.0 tool.

Epitope modeling and molecular docking

The 1AO7 complex was selected from the protein data bank which includes the structure of the HTLV-I LLFGYPVYV peptide crystallized with the HLA-A*0201 molecule, the β2 microglobulin, the α and β chains of the TCR (PDB https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1AO7). The PyMol software (PyMol Molecular graphics system, V.1.8.6.2) was used to modify the TAX peptide sequence into the peptides analyzed in the present study. The Molsoft Mol Browser (version 3.8-7d) was used to generate the epitope modeling and molecular docking.

IFN-γ ELISpot assay

IFN-γ ELISpot (BD human IFN-γ ELISPOT Set) assay was performed on PBMCs from HLA-A*0201 healthy subjects. 4×106 PBMCs/mL/well were stimulated ex vivo with viral peptides at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. In particular, MLGTHAMLV (CytomegalovirusCMV)), ILDCVLVHL (human papillomavirus (HPV)) and IIIGALVGV (HIV) viral peptides were used for the ex vivo stimulation. On day three, 10 U/mL IL-2 was added to each well. On day five, half of the volume of medium was replaced with fresh medium containing IL-2 at a final concentration of 10 U/mL. On day seven, PBMCs were restimulated with each peptide. On day 10, cells were harvested for IFN-γ ELISpot assay. Paired TAA peptides MLGTHTMEV (gp100), ILDKVLVHL (Caseinolytic Mitochondrial Matrix Peptidase Proteolytic Subunit (CLPP)) and IMIGVLVGV (Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)) were added at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL to 2×105 PBMCs per well in 100 µL RPMI 1640 medium (Capricorn Scientific GmbH). PBMCs were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 20 hours. Stimulation with 10 µg/mL Phytohemagglutinin (PHA-K; Capricorn Scientific GmbH) was used as positive control, PBMCs without added peptides were used as the negative control, RPMI 1640 medium (Capricorn Scientific GmbH) was used as background control. The plates were read with an AID EliSpot Reader Systems (AID GmbH, Strassberg, Germany). Determinations from triplicate tests were averaged. Data were analyzed by subtracting the mean number of spots in the wells with cells and medium-only from the mean counts of spots in wells with cells and antigen. Spot forming units (SFU) were calculated as the frequency per 106 PBMCs.

The computational model

The computational model C-IMMSIM derives from a general-purpose simulation platform that suitably characterizes the role of the immune response in different human pathologies such as infections, cancer, hypersensitivity, and inflammation. The model integrates the primary sequences of TCRs, BCRs, paratopes, peptides and epitopes of the antigen (eg, a virus or a tumor antigenic determinant). It exploits immunoinformatics tools to calculate B-cell epitopes and TCR peptides of antigenic sequences, and a generic contact potential to estimate the affinity between T-cells receptors and peptides presented by antigen-presenting cells, infected cells, or, as in the present case, malignant (tumor) cells.40 41 Besides that, the model accepts in input any pre-calculated list of peptides associated with a “ranked likelihood” to bind a certain HLA,42 for example, NetMHCstabpan.39 Moreover, an arbitrary value is introduced in the modeling to evaluate the conformational similarity between the paired peptides. In the present study, a number of malignant cells (103 cells) are set in the simulated volume (about 10 µL) at the beginning of the simulation (ie, day 0). These cells promptly start to duplicate (population doubling time of about 80 hours) and, in absence of therapy, they would reach a limiting value determining the interruption of the simulation (this limiting value is set to 3.4×105 cancer cells/µL).

The vaccination protocol consists of five injections of paired peptides formulated with a generic “virtual” adjuvant whose unique effect is to activate innate immune cells. The vaccine administration protocol is shown in online supplemental figure 4. The results refer to simulations of 80 days of virtual time post-tumor implantation.

jitc-2021-002694supp001.pdf (60KB, pdf)

jitc-2021-002694supp002.pdf (1.8MB, pdf)

Results

Blast search for homology between tumor antigens and viral sequences

Peptides from the cancer antigenic peptide database (https://caped.icp.ucl.ac.be/Peptide/list) were used to interrogate the NetMHCpan predictive algorithm. Predicted SBs restricted to the most frequent MHC class I alleles were selected (nr. 99) with a binding affinity value <100 nM. The vast majority of such SB were identified for the HLA-A*0201 (75 out 99, 75.7%) and 41/75 were identified in the “overexpressed” subgroup (table 1).

Table 1.

Affinity prediction for tumor-associated antigens from the cancer antigenic peptide database

| Mutation | Tumor specific | Differentiation | Overexpressed | ||||

| Seq | Aff (nM) | Seq | Aff (nM) | Seq | Aff (nM) | Seq | Aff(nM) |

| HLA-A*0201 | |||||||

| FLDEFMEGV | 2.86 | MLAVISCAV | 6.18 | IMIGVLVGV | 3.61 | FMNKFIYEI | 2.34 |

| VVMSWAPPV | 5.04 | KVLEYVIKV | 6.23 | RLMKQDFSV | 4.23 | RLMNDMTAV | 3.39 |

| GLFGDIYLA | 6.07 | GLYDGMEHL | 7.91 | YMDGTMSQV | 5.06 | RLAPFVYLL | 3.57 |

| LLDDLLVSI | 7.09 | FLWGPRALV | 8.25 | MLGTHTMEV | 7.3 | FLLGLIFLL | 3.81 |

| ILDKVLVHL | 23.6 | KVAELVHFL | 12.85 | MLLAVLYCL | 9.16 | LLNAFTVTV | 4.62 |

| FLIIWQNTM | 41.32 | KASEKIFYV | 19.14 | KTWGQYWQV | 10.05 | FLGYLILGV | 4.72 |

| ILNAMIAKI | 48.98 | KVVEFLAML | 28.91 | YLSGANLNL | 11.01 | RLVDDFLLV | 5.33 |

| RLSSCVPVA | 95.1 | FLDRFLSCM | 29.39 | SLSKILDTV | 11.3 | ILAKFLHWL | 6.69 |

| MLMAQEALA | 36.44 | TLMSAMTNL | 14.16 | SLLSGDWVL | 9.08 | ||

| ALSVMGVYV | 39.45 | LLWSFQTSA | 15.49 | ALLALTSAV | 9.8 | ||

| SLGWLFLLL | 62.17 | SVYDFFVWL | 30.44 | RMPEAAPPV | 9.87 | ||

| TLDSQVMSL | 40.15 | SLLQHLIGL | 10.34 | ||||

| FLFLLFFWL | 42.03 | LLGATCMFV | 10.56 | ||||

| YLEPGPVTA | 90.62 | ALWPWLLMA | 11.75 | ||||

| VLHWDPETV | 93.14 | LLGRNSFEV | 12.27 | ||||

| KIFGSLAFL | 12.97 | ||||||

| FMVEDETVL | 16.5 | ||||||

| MIAVFLPIV | 19.54 | ||||||

| FVGEFFTDV | 19.75 | ||||||

| TLNDECWPA | 20.02 | ||||||

| VLDGLDVLL | 22.43 | ||||||

| TLPGYPPHV | 23.06 | ||||||

| LLLLTVLTV | 23.85 | ||||||

| CQWGRLWQL | 24.33 | ||||||

| ALLEIASCL | 26.78 | ||||||

| FLALSILVL | 30.04 | ||||||

| RLLQETELV | 30.47 | ||||||

| ILHNGAYSL | 30.71 | ||||||

| VLVPPLPSL | 30.78 | ||||||

| LLSDDDVVV | 32.87 | ||||||

| VVLGVVFGI | 33.45 | ||||||

| KMDAEHPEL | 35.44 | ||||||

| CIAEQYHTV | 48.36 | ||||||

| HLSTAFARV | 49.81 | ||||||

| TIHDSIQYV | 50.48 | ||||||

| KVHPVIWSL | 57.52 | ||||||

| VLCSIDWFM | 58.74 | ||||||

| GLPPDVQRV | 64.57 | ||||||

| SVASTITGV | 70.61 | ||||||

| MIMVKCWMI | 74.82 | ||||||

| GLQLGVQAV | 77.31 | ||||||

| HLA-A*2402 | |||||||

| SYLDSGIHF | 30.15 | LYATVIHDI | 36.85 | IYMDGTADF | 11.17 | KYDCFLHPF | 21.58 |

| NYKRCFPVI | 76.24 | AFLPWHRLF | 36.32 | LYVDSLFFL | 73.72 | ||

| TYACFVSNL | 43.49 | NYARTEDFF | 100.71 | ||||

| VYFFLPDHL | 47.11 | ||||||

| HLA-A*0101 | |||||||

| YTDFHCQYV | 20.14 | EVDPIGHLY | 20.91 | N/A | N/A | ||

| YVDFREYEY | 11.2 | EADPTGHSY | 71.37 | ||||

| HLA-A*0301 | |||||||

| KINKNPKYK | 55.3 | SLFRAVITK | 12.2 | HLFGYSWYK | 6.17 | NTYASPRFK | 29.97 |

| LIYRRRLMK | 7.81 | VLRENTSPK | 31.21 | ||||

| ALNFPGSQK | 15.05 | LASFKSFLK | 90.6 | ||||

| ALLAVGATK | 38.81 | ||||||

| RSYVPLAHR | 64.02 | ||||||

In order to identify homologous viral sequences, all the predicted SB TAAs were subjected to global protein BLAST against the virus sequences within the GeneBank non-redundant protein database. The search returned a large number (n=82) of viral sequences sharing homology with the TAAs and the vast majority (n=75) were HLA-A*0201 restricted. Interestingly, the virus sharing the highest number of sequences with TAAs is the HIV type 1 (HIV-1) (36/82), followed by the Herpesviruses (22/82) and by the human papillomaviruses (9/82) (table 2).

Table 2.

Viral-derived sequences sharing sequence homology with tumor-associated antigens (TAAs)

| HLA-A*0201 | |||||

| Mutation | Tumor specific | ||||

| VVMSWAPPV | NWMSWVLPI | Envelope protein (HERV-H/env59) | MLAVISCAV | MLAVISTIR | Envelope glycoprotein UL33 (human betaherpesvirus 7) |

| GLFGDIYLA | GLFNDIYPN | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | FLWGPRALV | SQWGPRAIL | Deoxyuridine triphosphatase (human alphaherpesvirus 2) |

| LLDDLLVSI | CSDDLLISI | DNA packaging terminase subunit 1 (human betaherpesvirus 7) | KVAELVHFL | KVAELRQFL | Pol protein, partial (HIV 1) |

| ILDKVLVHL | ILEKVHVHL | Major capsid protein, partial (human papillomavirus) | KASEKIFYV | HEEEKVFYV | E2 protein (human papillomavirus 77) |

| ILDCVLVHL | E1 protein (human papillomavirus) | KVVEFLAML | KVVEFLSGS | Capsid maturation protease (human betaherpesvirus 5) | |

| FLIIWQNTM | LDIIWQNMT | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | |||

| RLSSCVPVA | AVSTCVPVA | Envelope glycoprotein B (human alphaherpesvirus 2) | |||

| Differentiation | Overexpressed | ||||

| IMIGVLVGV | IMVGALIGV | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | RLMNDMTAV | RLADDMTSV | Large tegument protein (human alphaherpesvirus 2) |

| IIIGALVGV | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | RLAPFVYLL | RLAPFGYKI | Polyprotein, partial (Vilyuisk human encephalomyelitis virus) | |

| IMIGGLIGL | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | FLLGLIFLL | PLLGLIFLS | Polymerase (human T-lymphotropic virus 4) | |

| RLMKQDFSV | NEMKQDFVV | Major capsid protein (human betaherpesvirus 5) | LLNAFTVTV | LLNAFAITV | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) |

| YMDGTMSQV | YMNSTMSET | Structural protein VP7 (human rotavirus A) | KKNAFTVTV | Early protein E2 (human papillomavirus 157) | |

| MLGTHTMEV | MLGTHAMLV | Membrane protein UL20 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | LLNAFAIAV | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | |

| MLLAVLYCL | NLLAVLYCV | Gag protein, partial (HIV 1) | FLGYLILGV | AVGYLILGV | CR1-alpha (human adenovirus 42) |

| NTLAVLYCV | Gag protein (HIV 1) | RLVDDFLLV | RLVDEFLAI | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | |

| KTWGQYWQV | DTWGEYWQA | Pol protein, partial (HIV 1) | RLVNDFLAL | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | |

| TWWGEYWQA | Pol protein, partial (HIV 1) | SLLSGDWVL | TDESGDWVL | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | |

| YLSGANLNL | YLSGANMLY | Hexon protein (human adenovirus 46) | ALLALTSAV | ALLPLTSAN | Polyprotein, partial (human poliovirus 2) |

| GDDKILDTV | Polyprotein (human enterovirus 79) | ALLALTKAQ | Outer capsid glycoprotein VP7, partial (human rotavirus A) | ||

| SLSKILDTV | SMTKILDTF | Pol protein, partial (HIV 1) | ALWPWLLMA | CLWPWLAIE | Envelope protein UL43 (human gammaherpesvirus 4), vpr protein (HIV 1) |

| TLMSAMTNL | CLMPAMTNN | UL86 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | VSWPWLLRW | Hypothetical protein (human alphaherpesvirus 2) | |

| LLWSFQTSA | SPWSFQTLT | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | TVLIWLLMA | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | |

| FLFLLFFWL | FLFMLYFWN | Protein UL140 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | LLGRNSFEV | LLGRNSFRG | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) |

| IVTLLFFLF | Protein UL140 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | LLGRNSWEA | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | ||

| YLEPGPVTA | TLEPGPVVR | L2 (human papillomavirus type 54) | KIFGSLAFL | KIFGSLVYF | L2 protein (human papillomavirus) |

| LLEPGPPTA | LF1 (human gammaherpesvirus 4) | TLPGYPPHV | DALGYPPHV | EBNA-3A (human gammaherpesvirus 4) | |

| VLHWDPETV | ALHWDPSIG | Unknown, partial (human picobirnavirus) | SPQHYPPHV | Capsid maturation protease (human alphaherpesvirus 1) | |

| LLLLTVLTV | LLLNTVLTV | ORF46 (human gammaherpesvirus 8) | |||

| CQWGRLWQL | DEWASLWXW | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | |||

| FLALSILVL | YLALSVLVT | Vif protein (HIV 1) | |||

| FLALSIVNR | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | ||||

| RLLQETELV | RLLQQTEVY | E6 (human papillomavirus type 39) | |||

| LLLQETEVI | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | ||||

| ILHNGAYSL | ILXNGXYSL | Truncated pol protein, partial (HIV 1) | |||

| ILXNGQYSL | |||||

| YYHNGAYSD | Envelope glycoprotein (HIV 1) | ||||

| VLVPPLPSL | DQVPPLPSL | Gag protein, partial (HIV 1) | |||

| KEIPPLPSL | Gag protein, partial (HIV 1) | ||||

| DREPPLPSL | Gag protein (HIV 1) | ||||

| LLSDDDVVV | SLAEDDVVV | Envelope glycoprotein, partial (HIV 1) | |||

| KMDAEHPEL | RMDAEHPGL | Polymerase PB1 (influenza B virus) | |||

| KMDEEHPGL | Polymerase PB1 (influenza B virus (B/Ann Arbor/1994)) | ||||

| VFDPEHPEL | DNA polymerase (human mastadenovirus D, human adenovirus 63) | ||||

| CIAEQYHTV | SAAEAYHTV | Small hydrophobic protein (human metapneumovirus) | |||

| HLSTAFARV | LLSTAFARW | Protein UL150 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | |||

| LLSTAFAIW | Protein UL150 (human betaherpesvirus 5) | ||||

| TIHDSIQYV | QIHDRIQYV | BALF5 (human gammaherpesvirus 4) | |||

| KVHPVIWSL | SVHPVLWNC | ORF4a protein (human betacoronavirus 2c Jordan-N3/2012) | |||

| MIMVKCWMI | TQEVKCWMT | p24, partial (HIV 1) | |||

| MIMVKGIPK | Envelope glycoprotein O (human betaherpesvirus 5) | ||||

| MIMVKVGGQ | Pol protein, partial (HIV 1) | ||||

| DIMVKCYLA | DNA polymerase (human mastadenovirus C) | ||||

| HLA-A24:02 | |||||

| Mutation | Tumor specific | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| SYLDSGIHF | TYLDNGVHV | L2 protein human papillomavirus 204 | NYKRCFPVI | NYKKCYPKI | Human rotavirus A |

| Differentiation | Overexpressed | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| N/A | NYARTEDFF | LYKRTEDFW | Reverse transcriptase, partial (HIV 1) | ||

| HLA-A01:01 | |||||

| Mutation | Tumor specific | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| YVDFREYEY | ETMFREYNY | Envelope glycoprotein B (HHV-8) | N/A | ||

| Differentiation | Overexpressed | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| N/A | N/A | ||||

| HLA-A03:01 | |||||

| Mutation | Tumor specific | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| N/A | SLFRAVITK | SLFNAVVTL | Gag polyprotein, HIV 1 | ||

| Differentiation | Overexpressed | ||||

| TAA | Blast Seq | Virus | TAA | Blast Seq | Virus |

| ALNFPGSQK | ALNFPGKWK | Pol polyprotein, HIV 1 | LASFKSFLK | LAAFKSFLK | E1 protein human papillomavirus 57 |

Epitope prediction for the viral sequences

All the 82 viral sequences identified through the BLAST search, sharing sequence homology with the TAAs, were used to interrogate the NetMHCstabpan predictive algorithm. The results showed that only a limited number of such viral sequences (nr. 20) are predicted to be SBs to the corresponding MHC-class I alleles, and 9/20 sequences (45%) are derived from HIV-1. Affinity values are significantly lower than 100 nM and in most cases lower than 50 nM, which are comparable to those of the corresponding TAAs (table 3). Furthermore, the algorithm predicts an average binding stability of the viral sequences, expressed in hours, which is lower than the one predicted for the TAAs (6.01 hour vs 10.3 hour) but does not reach the statistical significance (table 3 and online supplemental figure 1). Overall, with the exception of few pairs with the viral sequences having suboptimal values of affinity and stability, all the others show predicted values of the highest biological relevance (figure 1).

Table 3.

Affinity and stability prediction for the paired peptides PLEASE ALSO IN THIS TABLE CHANGE COMMAS WITH DECIMAL DOT

| HLA | Epitope seq | Affinity (nM) | TAA | Class | Tumor | Pathogen | ID seq |

| A*02:01 | ILDKVLVHL | 23,6 | CLPP | Mutation | Melanoma | ||

| ILEKVHVHL | 378,08 | L1 capsid protein (HPV) | AEQ98783.1 | ||||

| ILDCVLVHL | 12,61 | E1 protein (HPV) | AYA94830.2 | ||||

| A*03:01 | ILDAVVAQK | 131,69 | EFTUD2 | Mutation | Melanoma | ||

| IIDAVVSQK | 117,57 | Non-structural protein (Chikungunya virus) | AND80849.1 | ||||

| A*24:02 | NYKRCFPVI | 76,24 | MAGE-A4 | Tumor specific | Multiple | ||

| NYKKCYPKI | 118,22 | Human rotavirus A | CAA54177.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | IMIGVLVGV | 3,61 | CEA | Differentiation | Gut ca | ||

| IMVGALIGV | 4,86 | Env protein (HIV-1) | ALF12185.1 | ||||

| IIIGALVGV | 8,04 | Env protein (HIV-1) | AAL98851.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | MLGTHTMEV | 7,3 | gp100 | Differentiation | Melanoma | ||

| MLGTHAMLV | 12,6 | Membrane protein UL20 HHV5 | AKI23125.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | MLLAVLYCL | 9,16 | Tyrosinase | Differentiation | Melanoma | ||

| NLLAVLYCV | 6,18 | Gag protein (HIV-1) | AAA45294.1 | ||||

| NTLAVLYCV | 38,61 | Gag protein (HIV-1) | AAS45421.1 | ||||

| MLLAALMIV | 5,38 | Env protein (HERVK) | CAA76880.1 | ||||

| A*03:01 | ALNFPGSQK | 15,05 | Gp100 | Differentiation | Melanoma | ||

| ALNFPGKWK | 36,42 | Pol (HIV-1) | AWT86382.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | RLMNDMTAV | 3,39 | HSPH1 | Overexpressed | Ubiquitous | ||

| RLADDMTSV | 5,65 | Large tegument protein (HSV-2) | AMB66144.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | RLAPFVYLL | 3,57 | HEPACAM | Overexpressed | LIVER | ||

| RLAPFGYKI | 24,96 | polyprotein (Vilyuisk human encephalomyelitis virus) | ACG55801.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | LLNAFTVTV | 4,62 | CD274 | Overexpressed | Multiple tissues | ||

| LLNAFAIAV | 8,96 | Env protein (HIV-1) | AXP14971.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | RLVDDFLLV | 5,33 | Telomerase | Overexpressed | Multiple tissues | ||

| RLVDEFLAI | 18,98 | Env protein (HIV-1) | AKR69573.1 | ||||

| RLVNDFLAL | 30,13 | Env protein (HIV-1) | ASN74133.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | LLLLTVLTV | 23,85 | MUC1 | Overexpressed | Gland epithelial | ||

| LLLNTVLTV | 5,88 | ORF46 (HHV8) | QKE51297.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | LLSDDDVVV | 32,87 | KIF20A | Overexpressed | Ubiquitous | ||

| SLAEDDVVV | 33,9 | Env protein (HIV-1) | QCC27033.1 | ||||

| A*02:01 | KMDAEHPEL | 35,44 | Secernin 1 | Overexpressed | Ubiquitous | ||

| RMDAEHPGL | 94,22 | Pol PB1 (influenza B virus) | AXA17413.1 | ||||

| KMDEEHPGL | 20,99 | Pol PB1 (influenza B virus) | ABL77000.1 | ||||

| A*03:01 | LASFKSFLK | 90,6 | RGS5 | Overexpressed | Ubiquitous | E1 (HPV 57) | BAF80482.1 |

| LAAFKSFLK | 78,01 | ||||||

TAA, tumor-associated antigen.

Figure 1.

Affinity and stability of paired peptides. The affinity and stability to corresponding HLA molecules were predicted by NetMHCstabpan for each viral and tumor-associated antigen paired peptides. The stability (Thalf) values are expressed in hours (h); the affinity (Aff) values are expressed in nanomolarity (nM).

Epitope modeling and molecular docking

In order to verify that predicted paired TAA and viral epitopes share similar contact residues with both the HLA molecule and the TCR, epitope modeling and molecular docking were performed for each paired peptides. This was possible only for HLA-A*0201 restricted epitopes, due to the lack of crystallized structures including both HLA and TCR for other alleles deposited in the PDB. Epitopes crystallized with the HLA-A*0201 and the TCR showing sequence homology with TAA peptides were not found. Therefore, fully aware of the possible caveats, the 1AO7 crystallized complex including the HTLV-I TAX epitope was used as general template to conduct the analyses.

CLPP versus E1 HPV

The ILDCVLVHL E1 HPV peptide is predicted to have a higher affinity (12.9 vs 24.98 nM) and a similar stability (5.36 vs 6.54 hours) than the ILDKVLVHL CLPP peptide. The interacting pattern between the residues of both peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR is identical. The only difference is represented by the difference in position 4 of the basic K with a polar C residue, which substantially changes the contact pattern with the α chain of the TCR (figure 2A). This would suggest that the TCR clones targeting the two peptides would share only the same β chain. Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues. However, only the HPV peptide shows two bonds between the L2 residue and the HLA K66 as well as the TCR α chain Q30, supporting the higher affinity to the HLA molecule and suggesting a limited T cell cross-reactivity (online supplemental figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Structural predicted conformation of paired peptides. The conformation of the paired viral and tumor-associated antigen peptides bound to the HLA-A*02:01 molecule is shown. The prediction was performed using as template structure the HTLV-I LLFGYPVYV peptide crystallized with the HLA-A*0201 molecule, the β2 microglobulin, the α and β chains of the T cell receptor (TCR) (PDB https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1AO7). Blue areas = contact points with HLA molecule; Red areas=contact points with the TCR α chain; Green areas=contact points with the TCR β chain.

Gp100 versus UL20 HCMV

The MLGTHAMLV UL20 human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) peptide is predicted to have high but lower affinity (15.38 vs 7.67 nM) and a good but lower stability (3 vs 6.4 hours) than the MLGTHTMEV gp100 peptide. The interacting pattern between the residues of both peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR is identical. Interestingly, the polar to non-polar T-A mismatch at position 6 does not changes the contact pattern (figure 2B). This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the two peptides would share the same α and β chains. Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues. This would support the high-affinity value for both peptides (online supplemental figure 2B).

HSPH1 versus large tegument protein HSV-2

The RLADDMTSV large tegument protein HSV-2 peptide is predicted to have high and similar affinity (5.65 vs 3.39 nM) and a good but lower stability (11.18 vs 24.75 hours) than the RLMNDMTAV HSPH1 peptide. The mismatches along the sequence between the paired peptides are conservative non-polar residues (A3M), non-conservative polar to non-polar (S8A) and polar to acidic (N4D). Nevertheless, this does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR, suggesting that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same chains (figure 2C). The pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides shows significant differences, including an increased distance at R1 – HLA Y159 and A3 – HLA Y99 bonds and the missing L2 – TCR α chain Q30. This may explain the lower binding stability of the HSV-2 peptide to the HLA compared with the HSPH1 peptide (online supplemental figure 2C).

HEPACAM versus polyprotein encephalomyelitis virus

The RLAPFGYKI polyprotein encephalomyelitis virus peptide is predicted to have high but lower affinity (28.02 vs 4.25 nM) and a lower stability (17.78 vs 7.02 hours) than the RLAPFVYLL HEPACAM peptide. The interacting pattern between the residues of both peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR is identical. Interestingly, the positive to non-polar K-L mismatch at position 8 as well as the conservative non-polar residues (G6V; I9L) do not change the contact pattern (figure 2D). This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the two peptides would share the same α and β chains. Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues. The only differences are observed in the interactions with the HLA L98 and Y84 residues which would explain the lower affinity and stability to the HLA of the polyprotein encephalomyelitis virus peptide compared with the HEPACAM peptide (online supplemental figure 2D).

CD274 versus ENV HIV

The LLNAFAIAV Env HIV peptide is predicted to have high but lower affinity (8.96 vs 4.62 nM) and a good but lower stability (11.15 vs 23.08 hours) than the LLNAFTVTV CD274 peptide. The interacting pattern between the residues of both peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR is identical. Interestingly, the polar to non-polar T-A mismatch at positions 6 and 8 as well as the conservative non-polar residues (I7V) do not change the contact pattern (figure 2E). This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the two peptides would share the same α and β chains. Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues. The only difference is the missing A8 – HLA D77 bond which would explain the lower affinity and stability to the HLA of the Env HIV peptide compared with the CD274 peptide (online supplemental figure 2E).

MUC1 versus ORF46 HHV8

The LLLNTVLTV ORF46 HHV8 peptide is predicted to have a higher affinity (5.88 vs 23.85 nM) with higher stability (13.11 vs 6.69 hours) than the LLLLTVLTV MUC1 peptide. The only mismatch along the sequence between the two peptides is the non-conservative polar to non-polar residue N to L at position 4. The contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR is identical. On the contrary, the contact pattern with the α chain of the TCR is substantially different, suggesting that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same β chain and a different α chain (figure 2F). The pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides shows a missing L2 – HLA K66 bond in the HHV8 peptide and two missing L2 – TCR α chain Q30 as well as T8 – HLA D77 bonds in the MUC1 peptide. All other bonds show no deviation in the distances. Such a pattern of hydrogen bonds may explain the higher affinity and stability to the HLA of the HHV8 peptide compared with the MUC1 peptide (online supplemental figure 2F).

KIF20A versus Env HIV

The SLAEDDVVV Env HIV peptide is predicted to have a high and similar affinity (33.9 vs 32.87 nM) with similar stability (1.84 vs 2.41 hours) than the LLSDDDVVV KIF20A peptide. The mismatches along the sequence between the two peptides are the non-conservative polar to non-polar S1L and A3S residues as well as the conservative acidic E5D residues. The contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR is identical. On the contrary, the contact pattern with the α chain of the TCR is substantially different, suggesting that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same β chain and a different α chain (figure 2G). The pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides shows three missing bonds in the KIF20A peptide, namely L2 – HLA K66, L2 – TCR α chain Q30 and A3 – HLA Y99. All other bonds show minor deviations in the distances. Nevertheless, the affinity and stability to the HLA of the two peptides are similar (online supplemental figure 2G).

Tyrosinase versus Gag HIV and Env HERV

The NLLAVLYCV Gag HIV peptide and the MLLAALMIV Env HERV peptide are predicted to have a very high and similar affinity (6.18 and 5.38 vs 9.16 nM) with high and similar stability (17.51 and 11.83 vs 12.3 hours) than (shouldn't be to?) the MLLAVLYCL tyrosinase peptide. The two mismatches along the sequence between the Gag HIV and tyrosinase peptides are conservative non-polar residues (L9V) and non-conservative polar to non-polar (N1M). This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR, with a minor change in the contact pattern with the α chain. This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same chains. The mismatches along the sequence between the Env HERV and tyrosinase peptides are conservative non-polar (A5V and V9L) and non-conservative polar to non-polar residues (M7Y and I8C). This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the α chain of the TCR. On the contrary, the contact pattern with the β chain of TCR shows a substantial change. This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same α chains but different β chains (figure 2H). Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues with minor deviations. The only exception for the Env HERV peptide is the missing M1 – HLA Y159 bond, although this does not impact neither on the affinity nor on the stability to the HLA compared with the Gag HIV and the tyrosinase peptides (online supplemental figure 2H).

CEA versus Env HIV

The IMVGALIGV Env1 and IIIGALVGV Env2 HIV peptides are predicted to have a very high and similar affinity (4.86 and 8.04 vs 3.61 nM) with high but lower stability (8.4 and 9.1 vs 29.43 hours) than the IMIGVLVGV CEA peptide. The mismatches along the sequence between the Env HIV and CEA peptides are all conservative non-polar residues. This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR, suggesting that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same chains. In particular, the Env2 HIV peptide shows the highest similarity with the CEA peptide (figure 2I). Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired peptides is extremely similar with identical distances between the interacting residues. The only exception for the Env1 peptide is the more distant V3 – HLA Y99 bond; for the Env2 peptide the missing I1 – HLA Y159 bond and the closer I2 – HLA E63 bond. The latter differences may support the lower affinity value to the HLA of the Env2 peptide compared with the Env1 and the CEA peptides (online supplemental figure 2I).

Telomerase versus Env HIV

The RLVDEFLAI Env1 and RLVNDFLAL Env2 HIV peptides are predicted to have a high but lower affinity (18.98 and 30.13 vs 5.33 nM) with good but lower stability (3.13 and 1.7 vs 5.87 hours) than the RLVDDFLLV Telomerase peptide. The mismatches along the sequence between the Env1 HIV and Telomerase peptides are conservative non-polar (A8L and I9V) and conservative acidic residues (E5D). This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the α and β chains of the TCR. This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same chains. On the contrary, the mismatches along the sequence between the Env2 HIV and Telomerase peptides are conservative non-polar (A8L and L9V) and non-conservative polar to acidic residues (N4D). The latter has a substantial change in the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the α and β chains of the TCR, suggesting that the TCR clones targeting the peptides would be different (figure 2L). Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired Env1 HIV and the telomerase peptides shows a deviation in the distance between the D4 – TCR α chain S100 residues. On the contrary, the pattern of hydrogen bonds observed in the paired Env2 HIV and the Telomerase peptides shows a deviation both in the distances in the D4 – TCR α chain S100 as well as in the R1 – HLA Y159 residues. The latter deviations in the pattern of hydrogen bonds may explain the substantially lower affinity and stability to the HLA of the Enva peptide compared with the Envb HIV and the Telomerase peptides (online supplemental figure 2L).

Secernin1 versus PolB1 influenza

The RMDAEHPGL Infl1 peptide is predicted to have a lower affinity (94.22 vs 35.44 nM) while the KMDEEHPGL Infl2 peptide is predicted to have a higher affinity (20.99 vs 35.44 nM) with similar stability (1.18 and 0.98 vs 1.03 hours) to the HLA than the KMDAEHPEL Secernin 1 peptide. The mismatches along the sequence between the Infl1 and Secernin 1 peptides are conservative basic residues (R1K) and non-conservative non-polar to acidic residues (G8E). This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR, while the contact pattern with the α chain of the TCR is severely affected. This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same β chain but different α chains. On the contrary, the mismatches along the sequence between the Inflb and Secernin 1 peptides are non-conservative non-polar to acidic residues (A4E and G8E). This does not substantially change the contact pattern between the residues of the peptides and the HLA as well as the β chain of the TCR, while the contact pattern with the α chain of the TCR is slightly affected. This would suggest that the TCR clone targeting the peptides would share the same β chain but different α chains (figure 2M). Furthermore, the pattern of hydrogen bonds shows a missing bond in the Infl2 and Secernin 1 peptides, namely L2 – HLA K66; a missing bond in the Infl1 and Infl2 peptides was observed, namely L9 – HLA T143. Moreover, a significant deviation was observed in the in the distance between A4 – TCR α chain bond of the Infla peptide. These differences in the hydrogen bonds may explain the affinity and stability to the HLA observed for the two Influenza peptides compared with the Secernin 1 peptide (online supplemental figure 2M).

Ex vivo cross-reactivity to viral antigens and TAAs

A cross reactive immunity between paired HLA-A*02:01 restricted viral epitopes and TAAs was verified ex vivo using PBMCs from HLA-A*02:01 subjects. In order to simulate how an in vivo preimmunization to viral antigens might cross-react to a paired TAA expressed by cancer cells, PBMCs were “immunized” ex vivo with each of the selected viral peptides. After 14 days, the IFNγ ELISpot assay was then performed by restimulating in parallel with the “vaccine” viral peptide or the paired TAA peptide. The first observation was that individual subjects had variable levels of circulating T cells reacting to the viral peptides, with the strongest reactivity against the HPV ILDCVLVHL peptide and a significantly weaker reactivity against the CMV MLGTHAMLV and HIV IIIGALVGV peptides. The reactivity against the latter two peptides was not statistically different (figure 3A, B). Considering that the three viral peptides show comparable binding affinity, stability and T-cell propensity prediction scores, such a different IFNγ production could be explained by the expansion ex vivo of a pre-existing immunological memory to the HPV peptide. Strikingly, restimulation with paired TAA peptides induced a T cell cross-reactivity in all three settings, with inter-subject variation (online supplemental figure 3). Overall, gp100 and CEA TAA peptides induced an IFNγ production not statistically different from the paired viral peptides, CMV and HIV-1 respectively. On the contrary, restimulation with CLPP peptides induced a T cell response which was significantly lower than the HPV paired peptide (113 vs 802 SFU × 106 cells) (figure 3C). Interestingly, although binding affinity, stability and T-cell propensity prediction scores were similar between the three paired peptides, the structural conformation of the HPV and CLPP paired peptides showed a significant discordance (figure 2A). The latter observation could explain the lower T cell cross-reactivity induced by these two paired peptides.

Figure 3.

Ex vivo immunization with paired peptides. PBMCs from HLA-A*02:01 positive healthy subjects were immunized ex vivo with viral peptides. After 14 days, IFNγ EliSpot assay was performed restimulating the cells with the same viral peptide or with the paired tumor-associated antigen (TAA) peptide. Individual (A) and average (B) responsiveness to each viral peptide. (C) Average cross-reactivity versus viral and paired TAA peptides. SFU = IFNγ spot forming units.

Prediction of cross-reactive antitumor T cell response

Simulation experiments of cross-reactive antitumor T cells responses induced by the homologous viral epitopes were designed as previously described.40

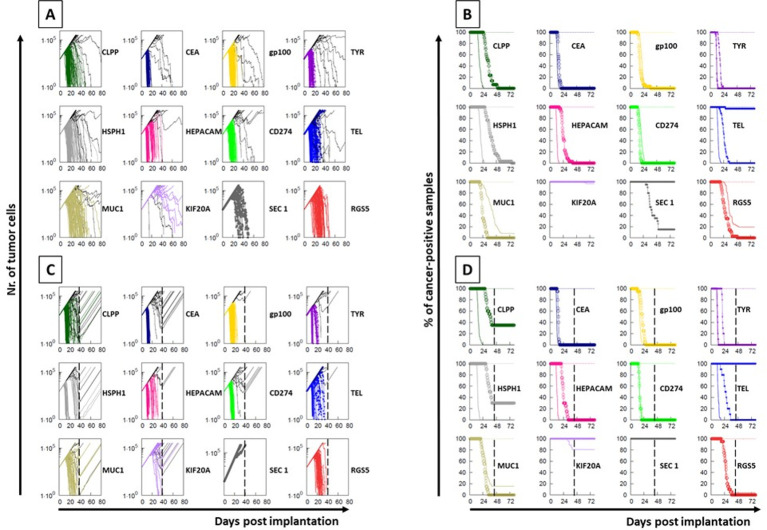

Each experiment simulated an in vivo vaccination with a TAA or its homologous viral epitope consisting of of five injections at days 7, 10, 13, 16 and 19. A subsequent challenge was simulated with 1×103 cancer cells expressing the TAA. The simulations showed that in most cases the clearance of the tumor cells is reached within an identical timeframe and curve’s shape, suggesting that the T cell immune response induced by the viral epitopes has the same antitumor efficacy as the one induced by the paired TAA. In other cases, for which the prediction affinity and stability values are significantly different, the timeframe is slightly (HSPH1), significantly (HEPACAM, TELOMERASE) delayed or no cross-reactivity is observed at all (KIF20A). Interestingly, the simulation model is able to assess the limited cross-reactivity between paired peptides with similar prediction affinity and stability values but showing a significant conformational difference (CLPP/HPV; MUC1/HHV8; SECERNIN1/INFLUENZA) (figure 4A, B). The same simulation approach is able to predict the role of the CD8+ T cell subset in the biological effect. Indeed, the curves of tumor growth show a rapid and steep increase when the removal at day 40 of the CD8+ T cells is simulated in the experimental models, and the percentage of cancer-free samples does not reach the zero (figure 4C, D).

Figure 4.

Simulation of immunization. An in vivo immunization and tumor challenge was simulated with 100 replicates. Multiple administrations of the viral or the paired TAA peptides were considered; the challenge was simulated with cancer cells expressing the tumor-associated antigen (TAA) peptide. The tumor growth (A) and the inverted Kaplan-Meier survival curve (B) are shown for each protocol. The same protocols were executed simulating the complete ablation of CD8+ T cells (C, D). In each paired peptides, the solid line indicates the results obtained with the TAA immunization while the circled line indicates the results obtained with the paired viral peptide immunization.

Discussion

In the present study we aimed at identifying, for the first time, viral epitopes with sequence and structural homology to TAAs, to be selected for eliciting an efficient cross-reacting CD8+ T cell response with a potential strong anticancer activity. Indeed, previous seminal studies by Oldstone have showed the same type of homology only between viral sequences and cellular antigens (the so called "molecular mimicry"), laying the foundation for the biological mechanisms driving the autoimmune diseases.43–45

All the TAAs from the cancer peptide database have been analyzed and a list of nonamer peptides have been predicted as SBs to the MHC class-I HLA-A*01:01, 02:01, 03:01 and 24:02 alleles, which altogether cover about 50% of the world population. In particular, about 60% of the European as well as the north American Caucasian populations, 50% of the Japanese population, 30% of the Chinese population, 20% of the Indian population (http://www.allelefrequencies.net). Among the predicted SBs, only those with a very high affinity (<100 nM) have been selected, given that, according to our previous studies, only these are confirmed to bind the HLA-A*02:01 molecule in 100% of the cases.37 Overall, 99 SBs have been predicted for the four alleles analyzed; 75.7% of them restricted to the HLA-A*02:01% and 54.6% of these belonging to the overexpressed subgroup. A large number (n=82) of viral sequences sharing homology with the TAAs were identified and the vast majority (n=75) were HLA-A*02:01 restricted. Such sequences were not uniformly derived from different human viruses. Indeed, the HIV-1 contributed by far with the largest number of viral sequences (36/82), followed by the herpesviruses (22/82) and the outdistanced human papillomaviruses (9/82). However, only 20 of such viral sequences are predicted to be SBs to the corresponding MHC-class I alleles. Strikingly, 45% of these sequences are derived from Gag and Env HIV-1 proteins, which is unlike to be a random observation (online supplemental figure 5). On the contrary, this would indicate that HIV-1 provide a significant number of TAA-like epitopes, supporting the epidemiological notion that people living with HIV or AIDS (PLWHA) have a significantly lower incidence of non-viral associated solid tumors compared with the HIV-negative population.46 47 Of interest is also the observed homology between the melanoma-associated tyrosinase TAA and an epitope derived from the HERVK env protein. Indeed, the HERVK expression in melanoma has been reported and a cross-reacting T cell response may play a relevant role in tumor prognosis.48

The epitope modeling showed that most of the paired TAA and viral epitopes not only share the same conformation but also the same contact patterns when docked into the HLA-A*02:01 molecule. In most cases, the paired peptides show the same contact patterns with the TCR α and β chains. The best examples are represented by the gp100/HCMV, the HEPACAM/ENCEPH, the CD274/HIV, tyrosinase/HIV, CEA/HIV and telomerase/HIVa pairs for which the contact pattern with the HLA-A*02:01 as well as the TCR α and β chains are identical. This would strongly suggest that, for each pair, the same CD8+ T cell clone may be able to cross-react with both peptides when presented in the context of the HLA-A*02:01 molecule. Moreover, in all cases, with the exception for the tyrosinase/HERV and CEA/HIVa pairs, the contact pattern with the TCR β chain is identical for paired epitopes suggesting that the reacting CD8+ T clones may express a TCR sharing the same β chain coupled with a different α chain. As anticipated, structural homologies between pair of peptides are highly dependent on the type of amino acid changes at specific positions and conservative changes are always predictive of structural preservation.

Furthermore, the number and the distance of hydrogen bonds formed by the residues of the paired epitopes with the HLA-A*02:01, the TCR α and β chains fully confirm the contact patterns as well as the predicted values of binding and stability. The lack of the homology between the analyzed peptides and the HTLV-1 Tax peptide crystallized in the 1AO7 structure may represent a bias for the constrained conformation. Nevertheless, regardless of the selected surrogate model, the different conformation and contact pattern between the peptide pairs evaluated in the present study confirm that indeed the approach is reliable to evaluate and compare conformation and molecular docking of peptides.

The biological confirmation of cross-reactive T cell responses against the paired peptides was assessed by ex vivo immunization experiments. PBMCs were induced for 14 days with the viral epitope and restimulated in parallel with the vaccine viral peptide and the paired TAA peptide. The results clearly showed induction of a significant cross-reactive response within the paired peptides. This effect was directly correlated with the conformational homology between the paired peptides. Indeed, the lowest cross-reactivity was observed between the HPV and CLPP peptides characterized by a significant conformational difference due to the C to K amino acid mismatch at position 4. The immunological cross-reactivity induced by paired peptides was further confirmed using a simulation approach, showing a noteworthy concordance with the prediction values as well as the conformational similarities. Indeed, also in this approach, the simulation of a vaccination with the HPV peptide showed the induction of a partial cross-protection against tumor cells expressing the paired CLPP TAA, while vaccination with the CMV and HIV-1 peptides induced a perfectly matching protection against tumor cells expressing the paired gp100 and CEA TAAs, respectively.

In conclusion, the present study shows for the first time the high sequence and structural homology between TAAs and viral sequences. In some cases, such homologies are striking. The number of high homologous epitope pairs is unlike to be a random event, given that the probability of an identical stretch of seven or eight amino acid in a nonamer sequence is extremely low (7.8×10–10 and 3.9×10–11, respectively).

On the contrary, this would strongly support the concept that TAAs and viral antigens may converge in the evolutionary process and may represent two sides of the same coin. In this respect, the previous exposure to specific viral epitopes may result in the establishment of a bi-specific antiviral/anticancer T cell memory if a cancer would develop during the lifetime presenting, by chance, a TAA sharing sequence and conformation similarities with the viral epitope. This may ultimately represent a relevant selective advantage for patients with cancer and may provide a totally new set of antigens for developing a novel preventive anticancer vaccine strategy.

Footnotes

CR and CM contributed equally.

Contributors: CM and AM performed bioinformatics predictions of binding affinity; CR performed all the epitope conformation and in vitro validation; BC performed the ex vivo analyses; LV contributed to the conformational analyses; EI performed the peptide synthesis and MR supervised the optimization of the peptide synthesis; FC performed the simulation analyses; MLT and FMB contributed to data analysis; MT and LB designed the study, supervised the analysis and drafted the manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by the FP-7 HEPAVAC (Grant nr. 602893) (LB); Transcan2 – HEPAMUT project (Grant nr. 643638) (LB); Italian Ministry of Health through Institutional “Ricerca Corrente” (LB); POR FESR 2014/2020 “Campania OncoTerapie” (LB, LV, MR); H2020 - iPC (Grant nr. 826121) (FC); AM is funded by “Ricerca Corrente”. CM, BC; CR are funded by POR FESR 2014/2020 “NanoCAN”.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article.

References

- 1.Melero I, Gaudernack G, Gerritsen W, et al. Therapeutic vaccines for cancer: an overview of clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2014;11:509–24. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pol J, Bloy N, Buqué A, et al. Trial Watch: peptide-based anticancer vaccines. Oncoimmunology 2015;4:e974411. 10.4161/2162402X.2014.974411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melief CJM, van Hall T, Arens R, et al. Therapeutic cancer vaccines. J Clin Invest 2015;125:3401–12. 10.1172/JCI80009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tran T, Blanc C, Granier C, et al. Therapeutic cancer vaccine: building the future from lessons of the past. Semin Immunopathol 2019;41:69–85. 10.1007/s00281-018-0691-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buonaguro FM, Tornesello ML, Buonaguro L. Virus-like particle vaccines and adjuvants: the HPV paradigm. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009;8:1379–98. 10.1586/erv.09.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visciano ML, Diomede L, Tagliamonte M, et al. Generation of HIV-1 virus-like particles expressing different HIV-1 glycoproteins. Vaccine 2011;29:4903–12. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buonaguro L, Tagliamonte M. Selecting target antigens for cancer vaccine development. Vaccines 2020;8. 10.3390/vaccines8040615. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vonderheide RH, Hahn WC, Schultze JL, et al. The telomerase catalytic subunit is a widely expressed tumor-associated antigen recognized by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Immunity 1999;10:673–9. 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80066-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Disis ML, Wallace DR, Gooley TA, et al. Concurrent trastuzumab and HER2/neu-specific vaccination in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:4685–92. 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang K, Pastan I. Molecular cloning of mesothelin, a differentiation antigen present on mesothelium, mesotheliomas, and ovarian cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996;93:136–40. 10.1073/pnas.93.1.136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finn OJ, Gantt KR, Lepisto AJ, et al. Importance of MUC1 and spontaneous mouse tumor models for understanding the immunobiology of human adenocarcinomas. Immunol Res 2011;50:261–8. 10.1007/s12026-011-8214-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkhurst MR, Fitzgerald EB, Southwood S, et al. Identification of a shared HLA-A*0201-restricted T-cell epitope from the melanoma antigen tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP2). Cancer Res 1998;58:4895–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Correale P, Walmsley K, Nieroda C, et al. In vitro generation of human cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for peptides derived from prostate-specific antigen. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:293–300. 10.1093/jnci/89.4.293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam KW, Li CY, Yam LT, et al. Improved immunohistochemical detection of prostatic acid phosphatase by a monoclonal antibody. Prostate 1989;15:13–21. 10.1002/pros.2990150103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Smet C, Lurquin C, van der Bruggen P, et al. Sequence and expression pattern of the human MAGE2 gene. Immunogenetics 1994;39:121–9. 10.1007/BF00188615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gnjatic S, Cao Y, Reichelt U, et al. NY-CO-58/KIF2C is overexpressed in a variety of solid tumors and induces frequent T cell responses in patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer 2010;127:381–93. 10.1002/ijc.25058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofmann O, Caballero OL, Stevenson BJ, et al. Genome-wide analysis of cancer/testis gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105:20422–7. 10.1073/pnas.0810777105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simpson AJG, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A, et al. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:615–25. 10.1038/nrc1669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karbach J, Neumann A, Atmaca A, et al. Efficient in vivo priming by vaccination with recombinant NY-ESO-1 protein and CpG in antigen naive prostate cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:861–70. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Theobald M, Biggs J, Hernández J, et al. Tolerance to p53 by A2.1-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med 1997;185:833–42. 10.1084/jem.185.5.833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buonaguro L, Tornesello ML, Gallo RC, et al. Th2 polarization in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infected subjects, as activated by HIV virus-like particles. J Virol 2009;83:304–13. 10.1128/JVI.01606-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parmiani G, Castelli C, Dalerba P, et al. Cancer immunotherapy with peptide-based vaccines: what have we achieved? Where are we going? J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:805–18. 10.1093/jnci/94.11.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fikes JD, Sette A. Design of multi-epitope, analogue-based cancer vaccines. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2003;3:985–93. 10.1517/14712598.3.6.985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrabba MG, Castelli C, Maeurer MJ, et al. Suboptimal activation of CD8(+) T cells by melanoma-derived altered peptide ligands: role of Melan-A/MART-1 optimized analogues. Cancer Res 2003;63:1560–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parkhurst MR, Salgaller ML, Southwood S, et al. Improved induction of melanoma-reactive CTL with peptides from the melanoma antigen gp100 modified at HLA-A*0201-binding residues. J Immunol 1996;157:2539–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen JL, Dunbar PR, Gileadi U, et al. Identification of NY-ESO-1 peptide analogues capable of improved stimulation of tumor-reactive CTL. J Immunol 2000;165:948–55. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dao T, Korontsvit T, Zakhaleva V, et al. An immunogenic WT1-derived peptide that induces T cell response in the context of HLA-A*02:01 and HLA-A*24:02 molecules. Oncoimmunology 2017;6:e1252895. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1252895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bae J, Samur M, Munshi A, et al. Heteroclitic XBP1 peptides evoke tumor-specific memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes against breast cancer, colon cancer, and pancreatic cancer cells. Oncoimmunology 2014;3:e970914. 10.4161/21624011.2014.970914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birnbaum ME, Mendoza JL, Sethi DK, et al. Deconstructing the peptide-MHC specificity of T cell recognition. Cell 2014;157:1073–87. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stone JD, Chervin AS, Kranz DM. T-cell receptor binding affinities and kinetics: impact on T-cell activity and specificity. Immunology 2009;126:165–76. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03015.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hawse WF, De S, Greenwood AI, et al. TCR scanning of peptide/MHC through complementary matching of receptor and ligand molecular flexibility. J Immunol 2014;192:2885–91. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balachandran VP, Łuksza M, Zhao JN, et al. Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2017;551:512–6. 10.1038/nature24462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tornesello ML, Buonaguro L, Izzo F, et al. Molecular alterations in hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections. Oncotarget 2016;7:25087–102. 10.18632/oncotarget.7837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:2189–99. 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 2015;348:124–8. 10.1126/science.aaa1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buonaguro L, Cerullo V. Pathogens: our allies against cancer? Mol Ther 2021;29:10–12. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrizzo A, Tagliamonte M, Mauriello A, et al. Unique true predicted neoantigens (TPNAs) correlates with anti-tumor immune control in HCC patients. J Transl Med 2018;16:286. 10.1186/s12967-018-1662-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reynisson B, Alvarez B, Paul S, et al. NetMHCpan-4.1 and NetMHCIIpan-4.0: improved predictions of MHC antigen presentation by concurrent motif deconvolution and integration of MS MHC eluted ligand data. Nucleic Acids Res 2020;48:W449–54. 10.1093/nar/gkaa379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rasmussen M, Fenoy E, Harndahl M, et al. Pan-Specific prediction of peptide-MHC class I complex stability, a correlate of T cell immunogenicity. J Immunol 2016;197:1517–24. 10.4049/jimmunol.1600582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapin N, Lund O, Bernaschi M, et al. Computational immunology meets bioinformatics: the use of prediction tools for molecular binding in the simulation of the immune system. PLoS One 2010;5:e9862. 10.1371/journal.pone.0009862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyazawa S, Jernigan RL. Residue-residue potentials with a favorable contact pair term and an unfavorable high packing density term, for simulation and threading. J Mol Biol 1996;256:623–44. 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Eichborn J, Woelke AL, Castiglione F, et al. VaccImm: simulating peptide vaccination in cancer therapy. BMC Bioinformatics 2013;14:127. 10.1186/1471-2105-14-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB, Wroblewska Z, et al. Molecular mimicry in virus infection: crossreaction of measles virus phosphoprotein or of herpes simplex virus protein with human intermediate filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1983;80:2346–50. 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB. Amino acid homology between the encephalitogenic site of myelin basic protein and virus: mechanism for autoimmunity. Science 1985;230:1043–5. 10.1126/science.2414848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oldstone MB. Molecular mimicry and autoimmune disease. Cell 1987;50:819–20. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90507-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grulich AE, Vajdic CM. The epidemiology of cancers in human immunodeficiency virus infection and after organ transplantation. Semin Oncol 2015;42:247–57. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2014.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calabresi A, Ferraresi A, Festa A, et al. Incidence of AIDS-defining cancers and virus-related and non-virus-related non-AIDS-defining cancers among HIV-infected patients compared with the general population in a large health district of Northern Italy, 1999-2009. HIV Med 2013;14:481–90. 10.1111/hiv.12034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schmitt K, Reichrath J, Roesch A, et al. Transcriptional profiling of human endogenous retrovirus group HERV-K(HML-2) loci in melanoma. Genome Biol Evol 2013;5:307–28. 10.1093/gbe/evt010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jitc-2021-002694supp001.pdf (60KB, pdf)

jitc-2021-002694supp002.pdf (1.8MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. All data relevant to the study are included in the article.