Abstract

Objective

Informal family caregivers play a crucial role in cancer care. Effective caregiver involvement in cancer care can improve both patient and caregiver outcomes. Despite this, interventions improving the caregiver involvement are sparse. This protocol describes a randomised controlled trial evaluating the combined effectiveness of novel online caregiver communication education modules for: (1) oncology clinicians (eTRIO) and (2) patients with cancer and caregivers (eTRIO-pc).

Methods and analysis

Thirty medical/radiation/surgical oncology or haematology doctors and nurses will be randomly allocated to either intervention (eTRIO) or control (an Australian State Government Health website on caregivers) education conditions. Following completion of education, each clinician will recruit nine patient–caregiver pairs, who will be allocated to the same condition as their recruiting clinician. Eligibility includes any new adult patient diagnosed with any type/stage cancer attending consultations with a caregiver. Approximately 270 patient–caregiver pairs will be recruited. The primary outcome is caregiver self-efficacy in triadic (clinician–patient–caregiver) communication. Patient and clinician self-efficacy in triadic communication are secondary outcomes. Additional secondary outcomes for clinicians include preferences for caregiver involvement, perceived module usability/acceptability, analysis of module use, satisfaction with the module, knowledge of strategies and feedback interviews. Secondary outcomes for caregivers and patients include preferences for caregiver involvement, satisfaction with clinician communication, distress, quality of life, healthcare expenditure, perceived module usability/acceptability and analysis of module use. A subset of patients and caregivers will complete feedback interviews. Secondary outcomes for caregivers include preparedness for caregiving, patient–caregiver communication and caring experience. Assessments will be conducted at baseline, and 1 week, 12 weeks and 26 weeks post-intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been received by the Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (REGIS project ID number: 2019/PID09787), with site-specific approval from each recruitment site. Protocol V.7 (dated 1 September 2020) is currently approved and reported in this manuscript. Findings will be disseminated via presentations and peer-reviewed publications. Engagement with clinicians, media, government, consumers and peak cancer groups will facilitate widespread dissemination and long-term availability of the educational modules.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12619001507178.

Keywords: world wide web technology, medical education & training, oncology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A major strength of this study is that the eTRIO interventions concurrently address caregiver involvement among all key stakeholders (patients, caregivers, doctors and nurses) in cancer consultations and care.

Another key strength is the use of web-based technology to ensure convenient, flexible and scalable delivery of education.

The inclusion of the user experience and engagement substudy will provide insights into how participants engage with online education, what aspects of the interactive modules are most useful and how these features impact on learning.

COVID-19 has resulted in changes to cancer service delivery (eg, telehealth consultations), caregiver involvement (eg, restrictions around accompanying persons and visitors) and clinician capacity to participate in research, therefore trial progress may be slower than originally anticipated.

Background

Informal family caregivers (a patient’s partner, family member or friend; known in this paper as ‘caregivers’) play a critical role in care for patients with cancer. They commonly attend consultations,1 provide emotional and informational support to patients,2 assist in treatment decision-making,3 support treatment adherence,4provide home-based care including helping manage symptoms/side effects5 and facilitate healthy lifestyle behaviours.6

However, reflecting their generally overlooked and under-supported position, caregivers tend to have greater unmet informational and psychosocial needs than patients themselves,7 as well as experiencing negative impacts on their physical health and quality of life.8 There is a demonstrated inter-relationship between patients and caregivers8 9; caregiver psychological and physical morbidity10 11 may compromise their ability to provide effective patient care, thereby impacting patient outcomes,12 including survival.13 Thus, interventions to support cancer caregivers are warranted to improve both caregiver and patient outcomes.

Good clinician–patient–caregiver communication can guide, educate and support caregivers in their roles.14 Empowering caregivers as partners-in-care is increasingly important as cancer care shifts from inpatient to outpatient, and increasingly home-based, healthcare models. However, some caregivers report feeling disempowered, excluded and ill-equipped to support patients.15 Suboptimal clinician–caregiver communication is common; consultation analyses found that oncologists rarely initiated interaction with caregivers during consultations.16 As a result, caregivers may self-censor information, questions and needs when communicating with clinicians. Furthermore, when not managed effectively, some caregivers can derail patient care by impeding discussions and informed decision-making17 as well as potentially compromising patient autonomy (eg, caregiver dominance) or privacy (eg, lost opportunities for patient–clinician to discuss sensitive topics such as sexual functioning). Other challenging situations can include conflicting patient–caregiver treatment wishes and caregiver anger.18 19 Skilful navigation of these complex triadic (clinician–patient–caregiver) situations is needed to optimise patient care as well as provide support and guidance to caregivers who may themselves be experiencing considerable distress.

Most clinicians report that they value caregiver input, but find aspects of caregiver involvement challenging, lack confidence in managing these challenges and want help navigating these complex interactions.18 20 Indeed, in a recent study, oncologists emphasised their lack of education in communicating with caregivers despite the very demanding family situations they frequently face.20 A 2019 Delphi consensus study among caregivers, researchers and clinicians to identify priority topics for caregiver research in cancer care, found that training for healthcare professionals working with caregivers achieved consensus among all stakeholder panels.21 To date, very little training has been developed to help clinicians manage or enhance communication with caregivers.

One intervention that has been developed, Responding to Challenging Interactions with Families used a didactic presentation and experiential role-play to educate nurses in responding to stressful family situations. Nurse’s confidence significantly increased following the programme.22 Another workshop-based intervention used didactic presentations, video clips and role plays to educate clinicians in how to conduct family meetings. Pre–post measures found a significant increase in self-efficacy to conduct family meetings and high levels of workshop satisfaction.23 Within these studies, clinician self-efficacy (confidence in one’s own capability to perform in a specific situation) has been a specific focus. Self-efficacy has been established as an efficient and reliable outcome for assessing the impact of clinician communication education,24 with associations between self-efficacy and actual performance found up to a year after a communication skills education programme.25 Despite promising results, the feasibility and long-term sustainability of face-to-face workshops remains a central concern as they are costly to run, accessible to only a few and difficult to sustain in the long-term. Well-designed online education can be effective in teaching complex skills, and can be more time and cost efficient compared with traditional face-to-face formats.26

Although clinician education has received little attention, an increasing number of interventions for cancer caregivers have been developed. Recent reviews have found existing interventions have focused primarily on information for caregivers (eg, patient symptom management) and psychosocial support for caregivers.27–29 Two of these reviews focused on technology-based interventions,27 28 and found high levels of acceptability, with caregivers appreciating the flexibility and personalisation of online interventions. These reviews also demonstrated that technology-based interventions can improve caregiver outcomes such as self-efficacy, burden, emotional well-being and quality of life.28

Despite its importance in the clinical context, only a small number of interventions have specifically focused on caregiver communication. One intervention that did aim to improve caregiver communication found that among a sample of 197 caregivers (patient illness not specified), a 2-hour webinar focusing on caregiver empowerment and consultation communication was effective in increasing caregiver self-efficacy and knowledge.30 Caregiver self-efficacy has been identified as an important component of a caregiver’s coping, with higher caregiver self-efficacy associated with lower caregiver burnout and psychosocial distress as well improved patient well-being.31 32 Wittenberg and colleagues33 recently published a Delphi consensus curriculum for cancer caregivers identifying seven key areas for future intervention development, one of which focuses on caregivers working with health professionals, including preparing for consultations, sharing information, asking and prioritising questions and communicating patient need. A paucity of targeted education for cancer caregivers to more confidently and skilfully engage with oncology clinicians remains.

Our team has been engaged in a research programme over 10 years (TRIadic Oncology; TRIO) focusing on understanding and improving caregiver communication in triadic cancer consultations. This has involved: a systematic review,1 qualitative studies,2 17 18 analyses of consultation audiotapes16 and development of a TRIO conceptual framework.34 This culminated in the first comprehensive TRIO Clinical Guidelines to help oncology physicians and nurses better communicate with, and support, caregivers.14 35 The TRIO Guidelines comprise two sets of evidence-based strategies aiming to improve clinician engagement with caregivers (eg, rapport building, meeting emotional/informational caregiver needs)14 and management of challenging and complex caregiver situations (eg, conflicting patient–caregiver treatment wishes, caregiver anger or dominance).35 Based on the TRIO Guidelines, as well as a web-review of online advice for caregivers regarding involvement in consultations,36 and a comprehensive review of existing caregiver communication evidence, we have developed two online interactive education modules: (1) for oncology doctors and nurses (eTRIO), to help clinicians effectively communicate, support and engage with caregivers (and patients); and (2) the patient–caregiver module (eTRIO-pc) to empower, motivate and educate caregivers in their caring role.37

Study aims

The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness of the combined clinician and patient–caregiver online education modules in improving caregiver confidence, engagement and management, when compared with control websites (NSW Health Support for Carers), using a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design.

It is hypothesised that:

The combined eTRIO and eTRIO-pc interventions, when compared with a control website, will result in improved caregiver self-efficacy in triadic consultation interactions (primary outcome)

-

Secondary hypotheses posit that

For clinicians the combined eTRIO and eTRIO-pc interventions will result in improved clinician self-efficacy in triadic consultation interactions, increased preferences for caregiver involvement, improved knowledge of strategies and improved use of caregiver inclusive policies/practices in the clinical setting.

For caregivers, the combined eTRIO and eTRIO-pc modules will result in higher preferences for caregiver involvement, greater satisfaction with clinician communication, lower distress, higher quality of life, greater preparedness for caregiving, improved patient–caregiver communication and an improved caregiving experience.

For patients, the combined eTRIO and eTRIO-pc modules will result in improved patient self-efficacy in triadic consultation interactions, higher preferences for caregiver involvement, greater satisfaction with clinician communication, lower distress and higher quality of life.

Exploratory aims for this trial include: (1) understanding the user experience, engagement and acceptability of the eTRIO and eTRIO-pc modules among patients, caregivers and clinicians (user experience and engagement substudy), (2) exploring the impact of the eTRIO modules on actual triadic consultation behaviours (audio recording substudy) and (3) exploring whether the eTRIO and eTRIO-pc interventions impact on patient and caregiver healthcare expenditure.

Methods

Study design

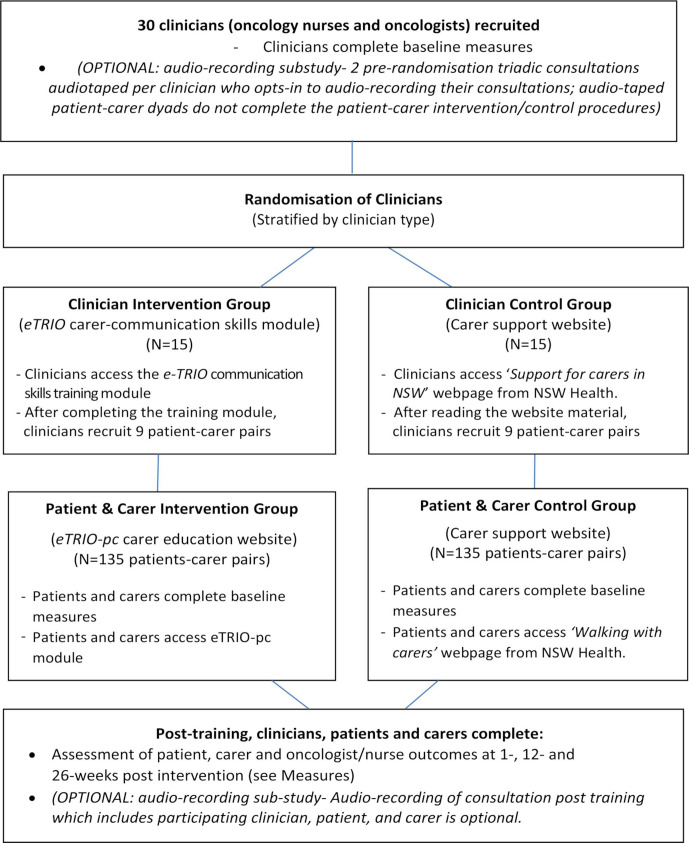

This is a Phase III, parallel group randomised controlled trial with 1:1 allocation ratio. In this RCT, 30 oncology clinicians will be randomly allocated. Randomisation will be stratified within each centre to ensure roughly equal numbers of eTRIO intervention and control clinicians at each participating site. Each clinician will recruit 9 or 10 patient–caregiver pairs to participate. Patients and caregivers receive the same allocation as their clinician (ie, those patients/caregivers whose clinician was randomised to receive eTRIO will receive eTRIO-pc, while those whose clinician was randomised to the control website will also be allocated to the control website) (see figure 1). See figures 2–4 for caregiver, clinician and patient timelines for enrolment, interventions and assessments.

Figure 1.

eTRIO trial study design.

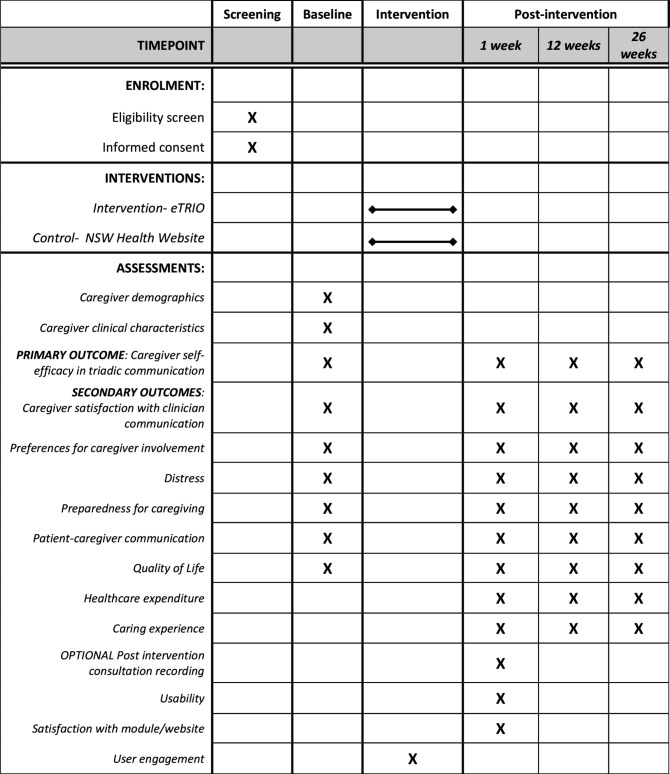

Figure 2.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments for participating caregivers.

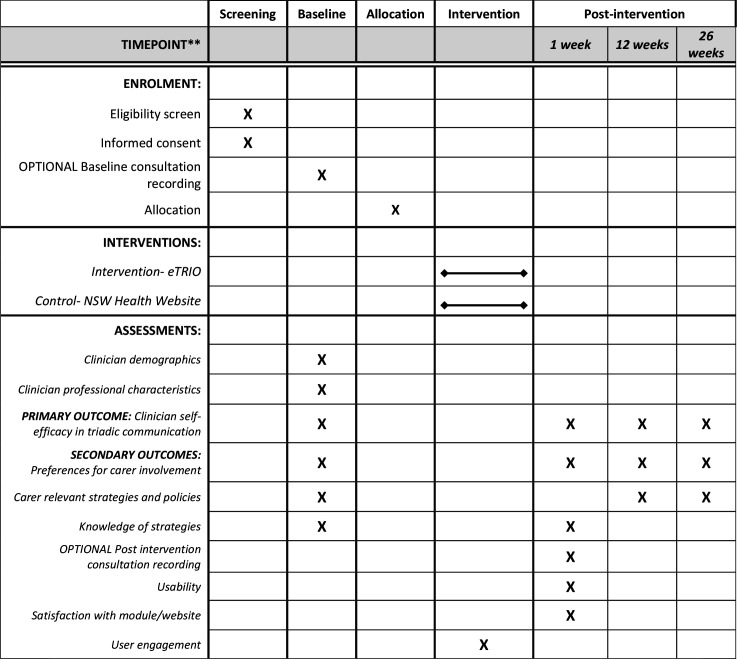

Figure 3.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments for oncology clinicians.

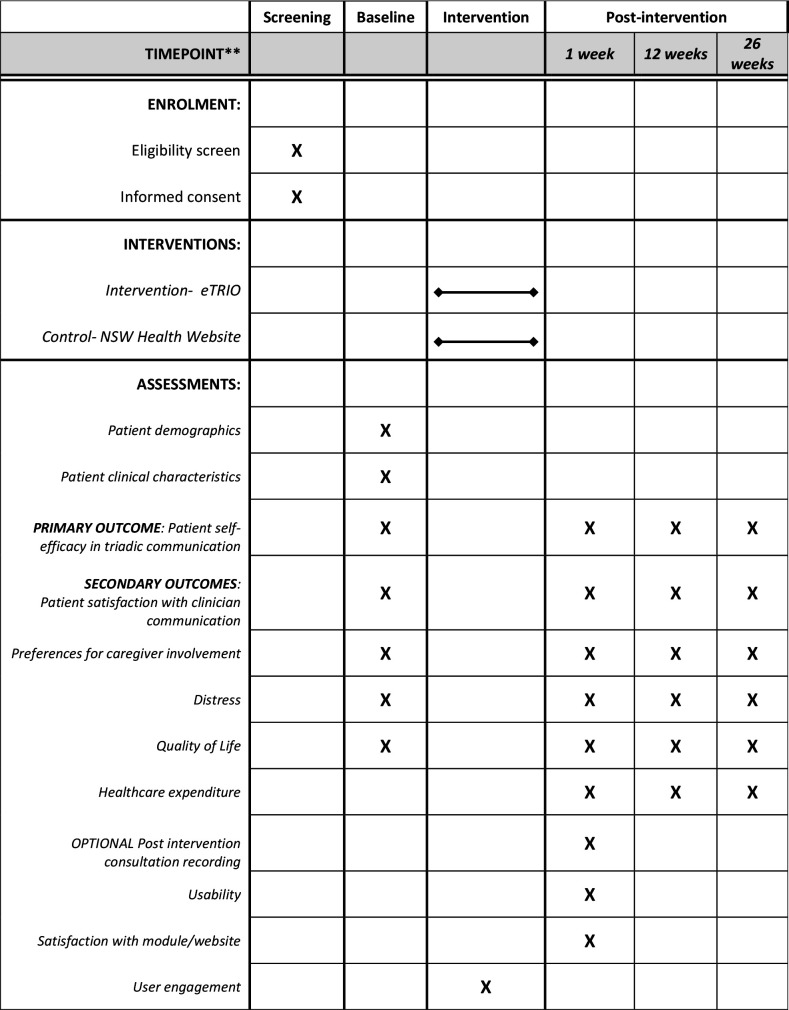

Figure 4.

Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials schedule of enrolment, interventions and assessments for participating patients.

Optional audio-recording substudy

An optional trial substudy will involve audio-recoding triadic consultations before and after randomisation to ascertain any changes in triadic consultation behaviours. Pre-randomisation, clinicians will audio-record (with patient–caregiver permission) one substantive consultation (ie, initial or treatment decision-making consultation; not brief review consultation) with each of two patient–caregiver pairs. These patients–caregivers will not complete the intervention or control condition and will only complete baseline measures. They will be known as the ‘baseline recording’ group.

After randomisation and completing the intervention/control condition, clinicians will (with patient–caregiver permission) audio-record one substantive consultation with each patient–caregiver pair who have participated in the full trial (ie, completed the patient–caregiver intervention/control condition).

Participants

Thirty oncology clinicians (oncology doctors and nurses) will be recruited by clinician champions at participating sites. Two hundred and seventy patient–caregiver pairs (ie, adults with cancer and the caregiver who usually accompanies them to consultations) will also be recruited, by their participating clinician. The study will be conducted in medical/radiation/surgical oncology and haematology hospital clinics around Australia.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible, clinicians will (1) be hospital-based medical/radiation/surgical oncology or haematology doctors (Registrar, Fellow or Specialist) and nurses (specialised in oncology/haematology nursing) treating patients diagnosed with any cancer type, (2) have consultations with patients and caregivers to discuss cancer treatment and (3) have ongoing and substantial patient and caregiver contact via face-to-face or Telehealth. Where doctors and nurses work together within the same consultations at a site, only one may participate in the study.

Patients will be screened for eligibility by their participating clinician and study staff. Patient eligibility criteria include: (1) diagnosis of any type and any stage of cancer (excluding those receiving end-of-life care), (2) aged >18 years, (3) attending a first, second or third oncology consultation with the eTRIO clinician, (4) willing to be accompanied to consultations by an informal caregiver, (5) have a suitable device (eg, computer, tablet, smartphone) and internet access and (6) cognitively and physically well enough to give informed consent to the study. Patients will be excluded if their clinician deems them too unwell or to have insufficient literacy and/or English language proficiency to complete the module/website and/or questionnaires.

Eligibility criteria for caregivers includes: (1) be an informal caregiver (family member, friend or neighbour who supports the patient inside and outside a consultation), (2) aged >18 years, (3) have a suitable device (eg, computer, tablet, smartphone) and internet access and (4) be willing to participate in the study. Caregivers will be excluded if they do not have sufficient literacy and/or English language proficiency to complete the module/website and/or questionnaires or if they are a paid, formal caregiver (such as a community support worker).

Description of the interventions eTRIO (clinician module)

The eTRIO module is an evidence-based online learning platform. The content of the module is based on extensive prior research from our team,1 2 16–18 the wider evidence-base7 19 38 39 and published consensus guidelines about communicating with caregivers.14 35 Module content underwent extensive iterative review from a multidisciplinary expert advisory group comprising psycho-oncologists, medical, surgical and radiation oncologists, oncology nurses and experts in the development of medical education and online learning.

The eTRIO web platform was designed by a professional web-development company with experience in designing health professional training with interactive functionality. Usability was refined in two ways. A usability expert conducted a heuristic evaluation method40 and the results were used to improve the interface. Then, testing was conducted using a think-aloud methodology with five health professionals naïve to the TRIO Guidelines (two consultant-level doctors and three specialist oncology/palliative care nurses), with amendments made to the module based on their feedback. Additionally, a targeted module based on the TRIO guidelines, developed with the McGrath Breast Cancer Foundation to specifically address the training needs of nurses facing complex situations with family carers such as dominance, anger or conflict was piloted.41 This pilot intervention was found to increase nurses’ confidence in managing interactions with carers. Qualitative feedback provided by participants helped to inform the features and functionality of the eTRIO module.

The final eTRIO module comprises 14 study units, of which clinicians must complete a minimum of 8. Depending on which eight units a clinician chooses to complete, the eTRIO module takes approximately 1.5–2 hours to complete. Table 1 displays a summary of the content and activities within the eTRIO module.

Table 1.

Summary of each guideline in the online eTRIO clinician module

| Guideline | Summary of content and activities |

| Introduction to eTRIO | Overview of the module, navigation tips, benefits of caregiver involvement, caregiver burden. Includes clinician self-reflection activity and true/false questions about the effects of caregiving. |

| Guideline 1: caregiver inclusive practices | Practical ways clinicians can include caregivers in clinic procedures and set up. Includes photos of good and poor clinic room setups. |

| Guideline 2: encouraging caregiver attendance | How to actively encourage caregiver attendance. Exploring reasons why caregivers do not attend consultations. Includes scenario question regarding encouraging caregiver attendance at an important consultation |

| Guideline 3: building rapport | Practical steps to build a positive relationship with caregivers. Includes interactive short film activity where clinicians identify good rapport building. |

| Guideline 4: patient privacy and confidentiality | How to manage sensitive information when a caregiver is present. How to deal with caregiver requests for patient information. Includes two short films exploring patient privacy and caregiver requests for information with reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 5: observing relationships | Signs to watch for between the patient and caregiver which indicate potential problems. Includes interactive image of non-verbal signs of family discord. |

| Guideline 6: emotional and informational needs | How to identify and manage the emotional and informational needs of caregivers. Includes true/false questions about caregiver needs and an interactive activity teaching the top five unmet informational needs of caregivers. |

| Guideline 7: large families | How to deal with a large family in the waiting room, and strategies to sensitively navigate this situation. Includes short film on managing many family caregivers, with multiple choice reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 8: requests for non-disclosure | How to deal with the request of “don’t tell my wife she has cancer”, and strategies on how to sensitively and legally navigate these requests. Includes short film on family request for non-disclosure, with open text reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 9: family as interpreters | Reasons why patients/caregivers might resist professional language interpreters, strategies to overcome these issues and strategies to engage and use formal interpretation services. Includes short film on managing resistance to formal interpretation services, with reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 10: conflicting treatment preferences | How to manage a patient and caregiver who disagree on the treatment, and strategies to negotiate a path forward in this stressful and emotional situation. Includes short film on managing patient-family conflict, with open text reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 11: caregiver dominance | How to identify the signs of unwanted caregiver dominance, and strategies to respectfully address and productively contain the caregiver’s dominance. Includes interactive short film activity where clinicians identify signs of dominance. |

| Guideline 12: caregiver anger | How to de-escalate the situation and strategies to establish a working relationship with the caregiver. Includes short film on managing angry family member, with reflective activity and feedback. |

| Guideline 13: longstanding family conflict | How to manage longstanding conflict between a patient and caregiver, and strategies to address the conflict, while not allowing it to derail the consultation. Includes short film on managing longstanding mother–daughter conflict, with reflective activity and feedback. |

eTRIO-pc (patient–caregiver modules)

The eTRIO-pc module is also an evidence-based online learning platform, informed by our group’s2 17 and others’15 42 research, as well as an extensive review of available online guidance for caregivers36 and interventions to improve caregiver engagement in consultations.29 The eTRIO-pc modules focus on providing informative and supportive content. Module content underwent extensive review by clinicians, patient and caregiver consumers, psychologists and other experts in supportive care and web-based patient and caregiver resources. eTRIO-pc was designed by a professional web-development company and features many interactive activities. Usability and user experience testing was conducted in a similar way to that described above for the clinician module, with the think-aloud user studies involving three caregivers and three patients with cancer/survivors naïve to the TRIO Guidelines. The module was iteratively refined based on user feedback.

Patient and caregiver modules are similar, however key differences include: (1) caregiver module is worded for the caregiver, patient module is worded for the patient; (2) the caregiver module is instructive about key caregiver skills and goes into more depth across the various topics; (3) the patient module informs the patient about what their caregiver is learning. The caregiver module comprises 11 units and takes approximately 1 hour to complete. Caregivers need to complete a minimum of six units of their own choosing. The patient module comprises seven units and takes approximately 40 min to complete. A minimum of four units of the patient’s choosing need to be completed. The content of the patient and the caregiver modules is summarised in table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of each component of the online eTRIO-pc module

| Module/section | Summary of content and activities |

| Caregiver module | |

| Introduction | Overview of the module, tips on navigation, definition of ‘caregiver’. |

| Part 1: the importance of caregivers | How important a patient’s caregiver is during the cancer process. Includes video of a cancer patient outlining benefits of caregiver involvement, and interactivity activity creating a caregiving team. |

| Part 2: introduction to cancer care | Becoming familiar with different cancer care health professionals and the rights of patients and caregivers. Includes video of a radiation oncologist discussing the importance of caregivers. |

| Part 3: first meetings with clinicians | How to establish a good working relationship with health professionals. Includes a short film modelling key caregiver behaviours in a first consultation. |

| Part 4: preparing for consultations | Ways to help caregivers prepare for a consultation with a health professional. Includes interactive question list builder and checklist of caregiver roles. |

| Part 5: caregiver roles during a consultation | Effective ways for caregivers to be involved during cancer consultations. Includes a short film modelling key caregiver behaviours in managing information (asking questions, taking notes) within a consultation. |

| Part 6: after the consultation | Ways to help the patient debrief after a consultation with a health professional. Includes experiences of real caregivers and patients. |

| Part 7: caregiver involvement in decision-making | How caregivers can help to support the patient when making decisions about their care. Includes interactive activity about ways caregiver can be helpful during decision-making. |

| Part 8: advocating for the patient | How to speak up for the patient in the healthcare setting. Includes a short film modelling key caregiver behaviours on how to speak up for a patient’s needs. |

| Part 9: if the caregiver feels ignored | What to do if a caregiver feels ignored by a health professional. |

| Summary and conclusions | Summary of all sections of the module. |

| Patient module | |

| Introduction | Overview of the module, why complete this programme, tips on navigation, who is considered a caregiver in this resource. |

| Part 1: the importance of caregivers | How important caregivers can be during cancer treatment. Includes video of a patient with cancer outlining benefits of caregiver involvement, and interactivity activity creating a caregiving team. |

| Part 2: introduction to cancer care | Becoming familiar with different health professionals patients may meet during cancer care and the rights of patients and caregivers. Includes video of a radiation oncologist discussing the importance of caregivers. |

| Part 3: including caregivers in consultations | How a caregiver can introduce themselves to health professionals, and how patients can help to establish a good working relationship between caregivers and health professionals. |

| Part 4: how caregivers can help in consultations | Ways that caregivers can be involved before, during and after consultations with health professionals. Includes interactive question list builder and interactive checklist of caregiver roles. |

| Part 5: caregiver involvement in medical decisions | Caregiver involvement in decisions about cancer care. |

| Conclusion | Summary of all sections of the module. |

Description of the control condition: clinicians

Entitled ‘Support for carers in NSW’, available on an Australian State Government Health website https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/carers/Pages/default.aspx, this was selected as an attention control because it is a relevant government webpage for clinicians, provides a range of additional resources for interested clinicians and is likely to represent the extent of professional development on caregiver inclusivity that average clinicians would receive.

Description of the control condition: patients/caregivers

The website the ‘Walking with Carers in NSW’ website, publicly available on an Australian State Government Health website https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/carers/Publications/walking-with-carers-in-nsw.pdf, was selected as an attention control because it is a relevant government webpage for patients and caregivers, provides a high level of supportive information for caregivers and is likely to represent the extent of caregiver support that average patients/caregivers would receive in standard care.

Procedures

Recruitment

Clinicians

Clinician champions (individual clinicians approached by the study team to assist with the trial at specific hospital sites) will assist in recruiting hospital-based surgical/medical/radiation/haematology doctors and nurses with a range of experience at their respective sites. Interested clinicians will discuss the study with clinician champions and/or study staff and will be provided with a participant information statement and consent form. Clinician champions will be eligible to participate in the trial if they are not existing members of the study team and have not been involved in development of the eTRIO or eTRIO-pc modules. We expect to recruit five clinicians per month over the course of 6 months.

Patients and caregivers (intervention/control group)

Nine patient–caregiver pairs per participating clinician will be recruited and complete either intervention or control procedures. Eligible patients of participating clinicians, and their caregivers, will be invited to participate in a study ‘testing which of two different websites is most helpful in preparing and empowering caregivers to participate in cancer consultations’. Recruitment must take place prior to the third consultation with a participating clinician. We expect to recruit approximately 31 patient–carer dyads per month over the course of 9 months.

Potential patient and caregiver participants will be invited to the study via one of the following recruitment pathways. Each recruiting clinician can select the most appropriate and feasible option/s:

Clinic research nurses/staff: Clinic research staff members will call eligible patients with an upcoming appointment with a participating clinician and introduce the study to them. Staff will assess interest, and if verbal consent gained, provide to the researchers, the patients’/caregivers’ contact details.

Participating clinicians: Participating clinicians will introduce the study to patients/caregivers during their consultation and obtain permission to pass on the details of interested patients/caregivers to the research team.

Study staff: The researchers will check with participating clinicians whether any potentially eligible patient–caregiver pairs are attending the consultation. A study staff member will approach eligible and clinician-approved patients/caregivers before or after a consultation in the waiting room of the clinic and invite them to participate in the study.

Invitation letter: Participating clinicians will send an invitation letter to eligible patients (and caregivers), providing patients and caregivers with the researchers’ phone number and email address to contact if they are interested in participating in the study (opt in approach).

Interested patients and caregivers will be telephoned by a member of the research team to explain the study in detail and screen eligibility. If eligible and willing to participate, they will each be sent individual participant information sheets via email or post, depending on their preference. An electronic consent form will be available at the start of the REDCap questionnaire (REDCap is a secure web application for managing online surveys and databases) or will be posted for those participants preferring to complete a hardcopy. Both the patient and the caregiver will need to provide consent to participate in the study.

Patients and caregivers (OPTIONAL ‘baseline recording’ group)

An OPTIONAL substudy will assess pre and post intervention communication. It is optional due to practical/logistical challenges of audio-recording suitable consultations as well as personal preferences of some clinicians, patients and caregivers who do not wish to audio-record their consultations. A subgroup of patient–caregiver pairs, comprising two pairs per clinician, will be recruited for the purpose of collecting baseline data on participating clinicians’ behaviours. This is an optional component of the study and will only be completed by clinicians opting to participate in the optional audio-recording substudy. Patient/caregiver eligibility criteria for this substudy are the same as for the main study. Eligible patients of participating clinicians and their caregivers will be invited to participate in a study ‘observing the interaction between health professionals, patients and caregivers by audio-recording a cancer consultation’. Potential participants will be approached and invited to the study through recruitment pathways described in the Patients and Caregivers (Intervention/Control Group) section. Patients and caregivers recruited to the ‘baseline recording’ subgroup will not go on to participate in the main eTRIO trial.

Randomisation

Participating clinicians will be directed to a link in an email invitation in order to receive a unique username and password to access the baseline questionnaire in the online survey platform REDCap. After completing the baseline questionnaire, clinicians will be randomly allocated (1:1), stratified by profession (doctor or nurse), to the intervention or control group. Randomisation will be electronically generated by the trial statistician (DSJC) using an Access database. Allocation will be concealed in sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes which will be opened by a research assistant not involved in the enrolment of clinicians, during the randomisation process.

No patient or caregiver randomisation will be required, as the recruiting clinician’s randomisation will determine to which website the patient and caregiver will be allocated. Given the nature of the intervention, blinding of researchers and participants is not possible.

Post-randomisation procedures

Clinicians

All clinicians randomised to both intervention and control groups will be asked to visit their respective websites within 4 weeks post-randomisation. They will be emailed a link to their respective website (intervention participants will be required to create a user account). Three reminders via email and/or short messaging service (SMS) (1, 2, 3 weeks post-randomisation) will be sent to prompt completion of the intervention/control websites.

Once they have completed the intervention/control, clinicians will recruit nine new patient–caregiver pairs. New patient–caregiver pairs are defined as attending a first, second or third consultation. The restriction to new patients and caregivers is because of the wide variability and potential confounding nature of existing clinician–patient–caregiver relationships which may have entrenched dynamics and patterns of communication. Clinicians participating in the audio-recording substudy will be asked to record one of these consultations for each participating patient–caregiver pair. All clinicians will complete follow-up questionnaires via the online survey platform REDCap at 1, 12 and 26 weeks after intervention completion. Feedback interviews will be conducted with all clinicians to obtain feedback about their experience of either the eTRIO intervention or Support for Carers control.

Patients and caregivers

Once consented, all participating patients and caregivers will be emailed a link to complete relevant baseline questionnaires in REDCap. Each participant will then be emailed a link to the website they have been randomised to visit (either eTRIO-pc or NSW Health Support for Carers). Three reminders via email and/or SMS (1, 2, 3 weeks post-randomisation) will be sent to prompt completion of the intervention/control websites. All patient and caregiver participants will be prompted to separately complete follow-up online questionnaires in REDCap at 1, 12 and 26 weeks after completion of the eTRIO-pc module. Given the nature of the trial, adverse physical and psychological events are not anticipated. However, participants will be reassured of their ability to discontinue participation at any time and referrals for psychological support will be provided should any participants become distressed during the trial. Feedback interviews will be conducted with a subset of patients and carers to obtain feedback about their experience of either the eTRIO intervention or Walking with Carers control.

Participant retention

Once enrolled and randomised, every reasonable effort will be made by study staff to follow all participants for the entire study period. Clinicians will be sent encouraging emails throughout the study. Participating clinicians will also be offered a US$50 gift card for participating in the study; to, in a small way, compensate them for time given to the study. In addition, clinicians could use the intervention to count towards continuing professional development points.

Patients and carers will be followed up three times at different times of the day by phone or email if questionnaires are not completed.

Measures

Caregiver measures

Table 3 summarises the caregiver primary and secondary outcome measures, with time point/s of administration displayed in figure 2. Caregiver demographics and clinical variables including age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, ethnicity and postcode will also be measured at baseline.

Table 3.

Summary of primary and secondary outcome measures

| Measures | Items and assessed construct |

| Clinician measures | |

| Oncologist and nurse self-efficacy in triadic communication | 13-item perceived self-efficacy in triadic communication scale based on Parle et al.51 |

| Preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication/decision-making | 2 questions developed by Shin et al44 assessing clinician preferences of caregiver involvement in treatment decision-making |

| Practical strategies/policies for including caregivers | 12-item purpose-built questionnaire assessing how clinicians welcome and manage caregivers in their own workplace |

| Knowledge of strategies | 14 purpose-designed situational vignette items assessing clinician knowledge/application of strategies to manage caregiver involvement. |

| Usability | 2-item UMUX-LITE.52 Assesses overall usability (ease of use and system capability) of module. |

| Satisfaction with the module/website | 11-item purpose designed questionnaire assessing participant satisfaction with features of eTRIO or NSW Health websites. |

| Caregiver measures | |

| Caregiver self-efficacy in interactions with their oncologist or nurse | 14-item perceived self-efficacy in triadic consultation communication adapted from PEPPI-1043 with seven additional items. |

| Caregiver satisfaction with communication with their oncologist and nurse | 25-item purpose-designed Consultation Satisfaction Scale adapted from.45 Assesses caregiver satisfaction with clinician communication. |

| Health literacy | 4 item health literacy measure.53 |

| Preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication/decision-making | 2-item scale44 assessing caregiver preferences for involvement. |

| Caregiver distress | 21-item Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21).46 |

| Preparedness for caregiving | 8-item Preparedness for Caregiving Scale.47 |

| Patient-caregiver communication | 2 subscales of the Health Literacy of Caregiver Scale—Cancer.48 Assesses cancer related patient–caregiver communication and needs and preferences. |

| Quality of life (health utility) | 12-item quality of life measure assessment of quality of life (AQoL)-4D.49 |

| Healthcare expenditure | Purpose designed incurred cost questionnaire. Assesses patient general practitioner (GP)/specialist visits, hospital stays, counselling and other support services. |

| Caregiver time | 2-item scale. Valued using the market price of labour (ie, wages or the aged pension). |

| Caring experience | The Carer Experience Scale.50 |

| Usability | 2-item UMUX-LITE.52 Assesses overall usability (ease of use and system capability) of module. |

| Satisfaction with the module/website | 11-item purpose designed questionnaire assessing participant satisfaction with features of eTRIO or NSW Health websites. |

| Patient measures | |

| Patient self-efficacy in interactions with their oncologist or nurse | 11-item perceived self-efficacy triadic consultation communication adapted from PEPPI-1043 with four additional items. Assesses patient self-efficacy in triadic communication with their clinician and caregiver. |

| Patient satisfaction with communication with their oncologist and nurse | 25-item purpose-designed Consultation Satisfaction Scale, adapted from.45 Assesses patient’s satisfaction with communication with their clinician. |

| Health literacy | 4 item health literacy measure.53 |

| Preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication/ decision-making | 2 questions developed by Shin et al.44 Assesses patient preferences of caregiver involvement in treatment decision-making. |

| Patient distress | 21-item DASS-21.46 |

| Quality of life (health utility) | 12-item quality of life measure AQoL-4D.49 |

| Healthcare expenditure | 8-item purpose designed incurred cost questionnaire. Assesses patient GP/specialist visits, hospital stays, counselling and other support services. |

| Usability | 2-item UMUX-LITE.52 Assesses overall usability (ease of use and system capability) of module. |

| Satisfaction with the module/website | 11-item purpose designed questionnaire assessing participant satisfaction with features of eTRIO or NSW Health websites. |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of caregiver self-efficacy in interactions with the patient and their oncologist or nurse will be measured using a 14-item scale, based on the widely used, validated Perceived Efficacy in Patient–Physician Interactions scale (PEPPI-10).43 Seven relevant PEPPI-10 items were appropriately transformed to be caregiver related, with an additional seven items purpose-designed to assess other topics such as caregiver confidence in: establishing a relationship with the clinician, contributing to decision-making discussions and speaking up (advocating) for the patient. All questions will ask respondents ‘how confident are you in your ability to’ followed by 14 different caregiver behaviours/skills relating to consultation communication. As per PEPPI-10, ratings of strength of self-efficacy for each item will range from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes measured will include preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication and decision-making,44 caregiver satisfaction with communication with their clinician (adapted from45), caregiver distress,46 preparedness for caregiving,47 patient–caregiver communication,48 quality of life,49 healthcare expenditure (purpose designed measure), caregiver time and caring experience.50

Clinician measures

Table 3 summarises the caregiver primary and secondary outcome measures, with time point/s of administration displayed in figure 3. Clinician demographic and professional characteristics, including age, gender, years in practice, main cancers treated and prior communication skills training will also be obtained at baseline.

Secondary outcomes

Oncologist and nurse self-efficacy in triadic communication will be measured using a 13-item scale, based on the widely used Parle and colleagues’51 clinician communication self-efficacy scale, adapted to capture triadic communication. Questions will ask respondents ‘how confident are you in your ability to’ followed by 13 different clinician skills relating to triadic communication and management of caregivers. Ratings of strength of self-efficacy for each item will range from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (very confident). Other secondary outcomes include preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication/decision-making,44 perceived module usability52 as well as satisfaction with the module, knowledge of TRIO strategies and practical strategies/policies clinicians currently have in place to include caregivers (purpose designed questionnaires).

Patient measures

Table 3 summarises the caregiver primary and secondary outcome measures, with time point/s of administration displayed in figure 4. At baseline, patients will disclose their demographic and clinical details including age, gender, marital status, education level, occupation, ethnicity, diagnosis, stage of disease, treatment type and postcode.

Secondary outcomes

Patient self-efficacy in interactions with their oncologist/nurse and caregiver will be measured using an 11-item scale, based on the widely used, validated PEPPI-10.43 Seven relevant PEPPI-10 items were included, with an additional four items purpose-designed to assess other caregiver related topics such as patient confidence in establishing the caregiver’s involvement in consultations. All questions will ask respondents ‘how confident are you in your ability to’ followed by 11 different behaviours/skills relating to triadic consultation communication. As per PEPPI-10, ratings of strength of self-efficacy for each item will range from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (very confident). Other secondary outcomes will include preferences for involvement of the caregiver in communication and decision-making,44 patient satisfaction with communication with their oncologist and nurse (adapted from45), patient distress,46 health literacy,53 quality of life (health utility)49 and healthcare expenditure will also be measured.

User experience and engagement sub-study

This substudy seeks to gain insights into how participants used the eTRIO modules, to provide better understanding of its successes/failures, with the ultimate aim of providing lessons to others developing future online clinician, patient or carer resources.

Both intervention and control participants will be asked to complete a measure of user experience (UMUX-LITE)52 and a custom-designed feedback questionnaire assessing the usability and acceptability of either the eTRIO module or NSW Health Website. All intervention clinicians (n=15) and control clinicians (n=15) and a subset of intervention caregivers (n=15), control caregivers (n=15) and intervention (n=15) and control (n=15) patients will be invited to participate in semi-structured feedback interviews assessing the usability, acceptability and practical application of the intervention/control training. These interviews will take place between 1 week and 1 month post-intervention and will be analysed using thematic analysis. Participants will also answer questions about the amount of time spent on the website/module, the number of times they access the training, and percentage of the website/module they completed.

For intervention clinicians, caregivers and patients, participant engagement will also be assessed through percentage of modules’ content completed based on hits and Google diagnostics as well as user interaction with the modules analysed using captured log-data. This will include pages visited, time spent on each section, information viewed and downloaded and engagement with interactive activities such as videos watched and participant responses to questions. Website analytics will be used to better understand user behaviours and interaction with the eTRIO sites, including order of use, areas of high versus low engagement and revisit behaviour as well as devices used (eg, mobile, desktop). These insights may lead to improved understanding of how to engage with and educate clinicians, patients and carers using online tools as well as the aspects of the website that affected the other outcomes.

Triadic consultation behaviour (audio-recording substudy)

For those clinician, patient and caregiver triads who opt-in to the audio-recording substudy, their application of knowledge learnt throughout the intervention/control conditions will also be assessed pre-intervention and post-intervention using an adapted version of the validated 80-item KINCode behavioural coding system.16 KINcode codes for the behaviours of the clinician, patient and caregiver across four different consultation phases (history taking, information exchange, deliberation and logistical arrangements) and assess for the presence/absence of specific behaviours (eg, caregiver asks a question). Additionally, pre and post intervention behaviours captured in consultation audio-recordings (for those who have consented to do so) will also be qualitatively analysed using conversational analysis. Consultation data will be analysed and presented descriptively.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on a standardised mean difference between intervention and control groups of 0.5, which is a moderate effect and is widely used in situations like this where there are no published estimates of effect size from similar studies and no minimally important difference for the primary outcome measure. Assuming a 1:1 randomisation for online training versus control, a two-sided test with alpha=0.05, and 80% power, this gives a total sample of 126. To account for clustering by clinician we multiplied the number above by the design effect 1+(m–1)×ICC, where ICC is the intra-cluster correlation and m is the number of patient/caregivers per clinician (=7 expected after attrition). Based on reviews in psycho-oncology,54 we believe that using an ICC of 0.1 is appropriately conservative. Multiplying by the design effect, this gives a total required sample size of 202 patient–caregiver pairs. Based on attrition rates of studies described in a Cochrane review of caregiver psychosocial interventions,55 an attrition rate of 30% (10% at each time point) was considered appropriate. To account for this attrition rate, the required sample is 277 patient–carer dyads.

Data collection

Quantitative data will be collected through REDCap, a secure online survey platform which will allow close adherence to the study protocol. All primary outcome measures have been designed within the questionnaires to require a response, thereby minimising issues of missing data.

Research personnel have completed training in Good Clinical Practice Guidelines (internationally accepted standards for conducting clinical trials). They also completed training in REDCap questionnaire formation, data collection, storage, and retrieval.

Data analysis

Primary outcome

Intervention efficacy of the eTRIO and eTRIO-pc modules will be determined by group differences in changes in caregiver self-efficacy in triadic communication scores. Analyses will consist of a random effects linear regression model (ie, mixed effects model), with caregivers as the unit of analysis and intervention versus control as a clinician-level predictor. The random effect will account for multiple patients nested within each clinician. Assessment time will also be included as a factor, resulting in a three-level model (clinician–patient/caregiver-time). Potential confounders will be controlled for in all analyses. All caregivers who provide data at any time point will be included in the analysis. At the item level, missing data will be mean-imputed if at least half of the data are not missing. For aggregated variables (ie, those included in analysis), we will examine patterns of missingness, and the random effects model handles missing data by using all available information, that is, no explicit imputation.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes will be examined using separate random effects regression models created for each outcome measure across testing points, the same as for the primary outcome. For the patient and caregiver outcome variables (ie, satisfaction and distress), the clinician will be modelled as a random effect.

Feedback interview analysis

Feedback interviews will be transcribed verbatim and undergo thematic analysis.56 Team based coding and thematic conceptualisation with experts in qualitative methods will ensure rigorous analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol has received ethical approval from the Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee (REGIS project ID number: 2019/PID09787), with site-specific approval from each recruitment site.

Findings will be disseminated via normal academic channels (presentations, peer-reviewed publications) as well as engagement with clinicians, media, government and consumers. To ensure widespread dissemination of the eTRIO education, assuming it is found to be beneficial, the research team have partnered with two peak cancer groups in Australia, the Cancer Council NSW (non-government cancer information, advocacy and support service for patients and caregivers) and Cancer Institute NSW (state government health department which provides expert guidance on cancer control, including health professional education). On successful completion of the trial, the eTRIO modules will be incorporated into their respective online learning platforms for long-term availability to clinicians, patients and caregivers. Our team have established links with peak oncology professional and consumer groups and will advocate endorsement and use of the eTRIO modules. Implementation of the clinician module into professional oncology association training and postgraduate medical curricula will be advocated, including application for the eTRIO programme to have continuing professional development points.

Careful consideration has been given to the practical implementation and use of the modules in cancer care. The modules have been designed based on iterative feedback from stakeholders and principles of e-learning in medical education and training.57 The modules can be completed in small chunks over a period of time,58 include interactive activities and the presentation of information in various modalities,59 opportunities for revision and the ability to navigate back to topic areas of interest, while users direct their own learning by choosing the scope, pace and sequence of their learning.60 These features ensure the modules will be able to be scaled up for wider dissemination.

Patient and public involvement

Our groups’ early qualitative work on patients, caregivers and clinicians’ experiences of caregiver involvement prompted the development of the TRIO Guidelines and the eTRIO trial. A group of patient and caregiver consumer advisors (four patients and four caregivers), as well as an oncology clinician advisory group (medical, radiation and surgical oncology doctors and oncology nurses), have been actively involved in each stage of trial design and have provided iterative feedback on the design and content of the eTRIO and eTRIO-pc interventions.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the eTRIO intervention is the first to concurrently address caregiver involvement among all key stakeholders in cancer consultations and care (patients, caregivers, nurses and oncologists). The development and testing of the eTRIO modules signifies a critical step towards improved engagement with, and management of, caregivers in the cancer setting. The current Phase III data will indicate the effectiveness of the combined (eTRIO and eTRIO-pc) modules in improving stakeholder self-efficacy in communication and patient/caregiver psychosocial outcomes, and lowering patient/caregiver health costs. Namely, it is hoped that the modules will facilitate clinicians to be more inclusive of caregivers and more confident in managing the challenges of caregiver involvement. Additionally, it is hoped that caregivers will more effectively participate in consultations and support the patient, and patients with cancer/caregivers will be better informed, supported and less psychologically distressed.

This study has been designed to gain insights into the ways that participants use and engage with the eTRIO programmes, including the use of web analytics to understand actual user behaviours and qualitative interviews to elicit participant experiences of the modules. It is hoped that the user experience and engagement substudy will contribute to a better understanding of what technical features and functions contribute to improved medical education and supportive patient care. This novel and timely research has at its core the translation of the TRIO Guidelines into improved healthcare performance, by addressing known challenges of engaging caregivers in cancer care in an accessible and effective way. The ultimate goal of this research is to shift the status of caregivers from an under-served, vulnerable and disempowered cancer population to being confident, engaged and supported participants in the cancer care process.

Trial status

Patient recruitment is open.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the members of the eTRIO consumer advisory groups for their input into the intervention and trial design.

Footnotes

Contributors: IJ and PB conceptualised the study and formed the project team. All authors are members of the steering committee and contributed to the design of the study. IJ, RL-P and PB are the lead investigators of the study and the TRIO programme more broadly. RL-P, RK, ZB, IJ and PB drafted the study protocol and manuscript, which was reviewed, modified and supplemented by all other authors. PS, DSJC and PY form the trial methodology advisory committee, with DSJC responsible for data analysis. JK provides information technology expertise. ST, CS, BK, MJ, PY, FB and KW form the clinician advisory committee. AM provides expertise in patient and caregiver supportive care and community delivery. RLM will contribute specifically to design of the exploratory cost-effectiveness substudy. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This trial is supported by Cancer Australia and Cancer Council NSW, through the Priority-driven Collaborative Cancer Research Scheme (project number 1146383). Funding will be managed by study sponsor: The University of Sydney under the guidance of principal investigator IJ.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Protocol V.7 (dated 1 September 2020) is currently approved and reported in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Laidsaar-Powell RC, Butow PN, Bu S, et al. Physician-patient-companion communication and decision-making: a systematic review of triadic medical consultations. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:3–13. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Attitudes and experiences of family involvement in cancer consultations: a qualitative exploration of patient and family member perspectives. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:4131–40. 10.1007/s00520-016-3237-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem D, Wells R, et al. How family caregivers of persons with advanced cancer assist with upstream healthcare decision-making: a qualitative study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212967. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roter DL, Narayanan S, Smith K, et al. Family caregivers' facilitation of daily adult prescription medication use. Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:908–16. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas C, Morris SM, Harman JC. Companions through cancer: the care given by informal carers in cancer contexts. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:529–44. 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00048-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellis KR, Janevic MR, Kershaw T, et al. Engagement in health-promoting behaviors and patient-caregiver interdependence in dyads facing advanced cancer: an exploratory study. J Behav Med 2017;40:506–19. 10.1007/s10865-016-9819-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer 2015;121:1513–9. 10.1002/cncr.29223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun V, Raz DJ, Kim JY. Caring for the informal cancer caregiver. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2019;13:238–42. 10.1097/SPC.0000000000000438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Streck BP, Wardell DW, LoBiondo-Wood G, et al. Interdependence of physical and psychological morbidity among patients with cancer and family caregivers: review of the literature. Psychooncology 2020;29:974–89. 10.1002/pon.5382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rumpold T, Schur S, Amering M, et al. Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:1975–82. 10.1007/s00520-015-2987-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS. Physical and mental health trajectories of cancer patients and caregivers across the year post-diagnosis: a dyadic investigation. Psychol Health 2016;31:655–74. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1131826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litzelman K, Kent EE, Mollica M, et al. How does caregiver well-being relate to perceived quality of care in patients with cancer? exploring associations and pathways. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3554. 10.1200/JCO.2016.67.3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boele FW, Given CW, Given BA, et al. Family caregivers' level of mastery predicts survival of patients with glioblastoma: a preliminary report. Cancer 2017;123:832–40. 10.1002/cncr.30428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Boyle F, et al. Facilitating collaborative and effective family involvement in the cancer setting: guidelines for clinicians (TRIO Guidelines-1). Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:970–82. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy B. Family members of patients with cancer: what they know, how they know and what they want to know. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2011;15:428–41. 10.1016/j.ejon.2010.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S. Exploring the communication of oncologists, patients and family members in cancer consultations: development and application of a coding system capturing family‐relevant behaviours (KINcode). Psycho‐Oncology 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Family involvement in cancer treatment decision-making: a qualitative study of patient, family, and clinician attitudes and experiences. Patient Educ Couns 2016;99:1146–55. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Bu S, et al. Oncologists' and oncology nurses' attitudes and practices towards family involvement in cancer consultations. Eur J Cancer Care 2017;26. 10.1111/ecc.12470. [Epub ahead of print: 01 03 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, et al. Involving family members in cancer care: focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psychooncology 2000;9:101–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Røen I, Stifoss-Hanssen H, Grande G, et al. Supporting carers: health care professionals in need of system improvements and education - a qualitative study. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:58. 10.1186/s12904-019-0444-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lambert SD, Ould Brahim L, Morrison M, et al. Priorities for caregiver research in cancer care: an international Delphi survey of caregivers, clinicians, managers, and researchers. Support Care Cancer 2019;27:805–17. 10.1007/s00520-018-4314-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zaider TI, Banerjee SC, Manna R, et al. Responding to challenging interactions with families: a training module for inpatient oncology nurses. Families, Systems, & Health 2016;34:204–12. 10.1037/fsh0000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gueguen JA, Bylund CL, Brown RF, et al. Conducting family meetings in palliative care: themes, techniques, and preliminary evaluation of a communication skills module. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:171–9. 10.1017/S1478951509000224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nørgaard B, Ammentorp J, Ohm Kyvik K, et al. Communication skills training increases self‐efficacy of health care professionals. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 2012;32:90–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gulbrandsen P, Jensen BF, Finset A, et al. Long-Term effect of communication training on the relationship between physicians' self-efficacy and performance. Patient Educ Couns 2013;91:180–5. 10.1016/j.pec.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook DA, Levinson AJ, Garside S, et al. Internet-Based learning in the health professions: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2008;300:1181–96. 10.1001/jama.300.10.1181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heynsbergh N, Botti M, Heckel L, et al. Caring for the person with cancer: information and support needs and the role of technology. Psychooncology 2018;27:1650–5. 10.1002/pon.4722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin JY, Kang TI, Noll RB, et al. Supporting caregivers of patients with cancer: a summary of Technology-Mediated interventions and future directions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:838–49. 10.1200/EDBK_201397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrell B, Wittenberg E. A review of family caregiving intervention trials in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2017;67:318–25. 10.3322/caac.21396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore CD, Cook KM. Promoting and measuring family caregiver self-efficacy in caregiver-physician interactions. Soc Work Health Care 2011;50:801–14. 10.1080/00981389.2011.580835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merluzzi TV, Philip EJ, Vachon DO, et al. Assessment of self-efficacy for caregiving: the critical role of self-care in caregiver stress and burden. Palliat Support Care 2011;9:15. 10.1017/S1478951510000507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Porter LS, et al. The self-efficacy of family caregivers for helping cancer patients manage pain at end-of-life. Pain 2003;103:157–62. 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00448-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wittenberg E, Goldsmith J, Parnell TA. Development of a communication and health literacy curriculum: optimizing the informal cancer caregiver role. Psychooncology 2020;29:766–74. 10.1002/pon.5341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Charles C, et al. The TRIO framework: conceptual insights into family caregiver involvement and influence throughout cancer treatment decision-making. Patient Educ Couns 2017;100:2035–46. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, Boyle F, et al. Managing challenging interactions with family caregivers in the cancer setting: guidelines for clinicians (TRIO Guidelines-2). Patient Educ Couns 2018;101:983–94. 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keast R, Butow PN, Juraskova I, et al. Online resources for family caregivers of cognitively competent patients: a review of user-driven reputable health website content on caregiver communication with health professionals. Patient Educ Couns 2020. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.04.026. [Epub ahead of print: 05 May 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juraskova I, Laidsaar-Powell R, Butow P, et al. Facilitating effective family carer engagement in cancer care: development of the eTRIO education modules. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology 2019;15:90. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lown BA. Difficult conversations: anger in the clinician-patient/family relationship. South Med J 2007;100:34–9. 10.1097/01.smj.0000223950.96273.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hallenbeck J, Arnold R. A request for nondisclosure: don't tell mother. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5030–4. 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.8802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nielsen J. Usability engineering: Morgan Kaufmann 1994.

- 41.Laidsaar-Powell R, Keast R, Butow P, et al. Improving breast cancer nurses' management of challenging situations involving family carers: pilot evaluation of a brief targeted online education module (TRIO-Conflict). Patient Educ Couns 2021. 10.1016/j.pec.2021.04.003. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Apr 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Northouse L, Schafenacker A, Barr KLC, et al. A tailored web-based psychoeducational intervention for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs 2014;37:321–30. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maly RC, Frank JC, Marshall GN, et al. Perceived efficacy in patient-physician interactions (PEPPI): validation of an instrument in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:889–94. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb02725.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shin DW, Cho J, Roter DL, et al. Preferences for and experiences of family involvement in cancer treatment decision‐making: patient–caregiver dyads study. Psycho‐Oncology 2013;22:2624–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown R, Dunn S, Butow P. Meeting patient expectations in the cancer consultation. Ann Oncol 1997;8:877–82. 10.1023/a:1008213630112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behav Res Ther 1995;33:335–43. 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Archbold PG, Stewart BJ, Greenlick MR, et al. Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Res Nurs Health 1990;13:375–84. 10.1002/nur.4770130605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuen E, Knight T, Dodson S, et al. Measuring cancer caregiver health literacy: validation of the health literacy of caregivers Scale-Cancer (HLCS-C) in an Australian population. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26:330–44. 10.1111/hsc.12524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The assessment of quality of life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1999;8:209–24. 10.1023/a:1008815005736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Janabi H, Coast J, Flynn TN. What do people value when they provide unpaid care for an older person? A meta-ethnography with interview follow-up. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:111–21. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parle M, Maguire P, Heaven C. The development of a training model to improve health professionals' skills, self-efficacy and outcome expectancies when communicating with cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 1997;44:231–40. 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00148-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu LS, Huh J, Neogi T, et al. UMUX-LITE: when there’s no time for the SUS. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2013:49–58. 10.1145/2470654.2470663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halverson JL, Martinez-Donate AP, Palta M, et al. Health literacy and health-related quality of life among a population-based sample of cancer patients. J Health Commun 2015;20:1320–9. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bell ML, McKenzie JE. Designing psycho-oncology randomised trials and cluster randomised trials: variance components and intra-cluster correlation of commonly used psychosocial measures. Psychooncology 2013;22:1738–47. 10.1002/pon.3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Treanor CJ, Santin O, Prue G, et al. Psychosocial interventions for informal caregivers of people living with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;6:CD009912. 10.1002/14651858.CD009912.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Masters K, Ellaway R. E-Learning in medical education guide 32 Part 2: technology, management and design. Med Teach 2008;30:474–89. 10.1080/01421590802108349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Atack L. Becoming a web-based learner: registered nurses' experiences. J Adv Nurs 2003;44:289–97. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scott KM, Baur L, Barrett J. Evidence-Based principles for using technology-enhanced learning in the continuing professional development of health professionals. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2017;37:61–6. 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lau KHV. Computer-Based teaching module design: principles derived from learning theories. Med Educ 2014;48:247–54. 10.1111/medu.12357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.