Abstract

Introduction

Childhood obesity is a public health concern globally. In Arab countries, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased significantly over the last three decades. The level of childhood overweight and obesity in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is high and continues to increase. This study will explore factors associated with overweight and obesity among adolescents and identify barriers and enablers to the implementation of comprehensive school-based obesity prevention interventions.

Methods and analysis

Socioecological model will inform this mixed-methods study. The study will include three phases: (1) a scoping review of the literature; (2) the development of a student survey instrument and (3) a mixed-method study comprising a cross-sectional survey targeting students aged 12–15 years with the collection of the students’ height and weight measurements; one-on-one interviews with physical education teachers and school principals; and the administration of school climate audits using the Health Promoting School framework. Reliability and validity of the survey instrument will be examined during survey development. Descriptive, inferential and thematic analysis will be employed using appropriate statistical software.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been granted from the Curtin University of Human Research Ethics Committee (HR2020-0337) and from the KSA Ministry of Education (4181827686). School principals will provide permission to conduct the study in individual schools. Individual consent/assent will be obtained from students and their parents, and teachers. Study findings will be disseminated via peer-review publications, reports and conferences.

Keywords: public health, nutrition & dietetics

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study will employ multiple methodologies to explore barriers and enablers within a school context to inform the development of interventions to reduce the prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents.

The validated student survey and whole school audit tools will be enhance school-based planning.

A review of the published literature has indicated that this will be the first mixed-methods study to collecting data from students and teachers to specifically inform the development of whole school interventions and policy focusing on obesity preventions. Findings will inform school-based interventions in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA).

Participants will be recruited from intermediate level students from multiple schools; however, the study will be conducted only in one region of KSA, Jeddah.

Introduction

Obesity in general, and childhood obesity specifically, is a key public health issue in many high-income countries and is a steadily rising public health problem in low-income and middle-income countries. Globally, the overall overweight and obesity prevalence has nearly tripled since the mid-1970s and it is the fifth most common cause of mortality globally, contributing to at least 2.8 million deaths per year.1 2 Obesity among children and adolescents is associated with a range of psychological health issues including depression,3 4 low self-esteem5 and increased risk of infections.6 Childhood obesity is also a risk factor for several non-communicable chronic diseases in adulthood7 such as diabetes,8 hypertension,9 musculoskeletal disorders10 and heart disease.11 It also impacts academic outcomes of school students, overall quality of life12 and has been linked to psychosocial factors such as weight-based teasing.13 Obesity is also responsible for deaths in later life as a complication of chronic diseases.14 15 There is a substantial direct and indirect economic burden attributed to childhood overweight and obesity.16 Studies have reported costs attributable to overweight and obesity are three times higher for men and nearly five times higher for women with a history of childhood obesity.17 18

During the past three decades, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in Arabic speaking countries has steadily increased.19 A study among adults involving 52 countries found the Middle East region to score the highest mean body mass index (BMI) after North America.20 The increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in Eastern Mediterranean countries has reached a critical level where the prevalence of overweight and obese adolescents is greater than adolescents classified as normal weight.21 In a review conducted among children under 12 years in the Gulf countries, there was a 5%–14% and 3%–18% prevalence of obesity among males and females, respectively.22

Similarly, the level of childhood overweight and obesity in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is high and continues to increase.23 24 A study in 2012 in KSA among 19 317 children and adolescents (aged 5–18 years) found the prevalence of overweight, obesity and severe obesity to be 23%, 9% and 2%, respectively.25 Another recent study in 2015 in KSA among 7930 children aged 6–16 years reported 13% to be overweight and 18% to be obese.26 In recent decades, the population of KSA has undergone a nutritional transition where traditional food is being substituted by fast food which is usually energy-dense and nutrient-poor.27 The consumption of unhealthy foods and sugary carbonated drinks, especially among children and adolescents is increasing at a rapid rate.28 In addition, Saudi people are more likely to adopt sedentary lifestyles when compared with other non-Arab cultures.29 The increased socioeconomic status of KSA residents has also resulted in increased use of personal cars for transportation and an increase in indoor games and television viewing which has resulted in children and adolescents being less likely to walk to school and play outdoors than in the past.30

Considering the increased prevalence along with the health and economic issues associated with childhood obesity, effective programmes to encourage physical activity and improve healthy eating behaviours to prevent obesity are imperative.31 Schools have been identified as an ideal setting to promote health given the association between health and education along with the amount of time children and adolescents spend at school.32

The Health Promoting Schools (HPS) Framework is adopted by WHO and recommends a whole of school approach to promote healthy schools.33 34 The HPS Framework focuses on the domains of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning; School Organisation, Ethos and Environment; and Partnerships and Services.

Published research in KSA has primarily focused on a single element in regards to the determinants of weight-related issues among adolescents including anthropometric measurement35; dietary patterns such as eating in restaurants and sedentary lifestyles with low levels of physical activity.23 36 There is no published research that focuses on broader socioecological influences of overweight and obesity among Saudi children and adolescents within the school setting.37 This study aims to address this gap by adopting a mixed-methods approach to explore factors associated with overweight and obesity among intermediate school students aged 12–15 years within the school setting in Jeddah, KSA.

Methods

Objectives

The specific objectives of the study are: (1) to identify self-reported physical activity and nutrition knowledge, attitudes and behaviours (KAB); (2) to determine the association between BMI, sociodemographic factors and nutrition and physical activity related KAB and (3) to explore barriers and enablers to the implementation of comprehensive school-based obesity prevention interventions perceived by schoolteachers and school principals; and (4) undertake school audits to determine factors within the schools that may influence overweight and obesity.

Research design

This mixed-methods study will be informed by the socialecological model (SEM),38 which has been used in the context of obesity elsewhere.39 40 The HPS Framework will also inform the study design.41 This study will be conducted in three phases: (1) a scoping review of the literature; (2) the development of a student survey instrument and (3) a mixed-methods study comprising a cross-sectional survey of students aged 12–15 years investigating their KAB with regard to physical activity and nutrition; the collection of student BMI measurements; one-on-one interviews with physical education teachers and school principals; and school climate audits.

Theoretical framework

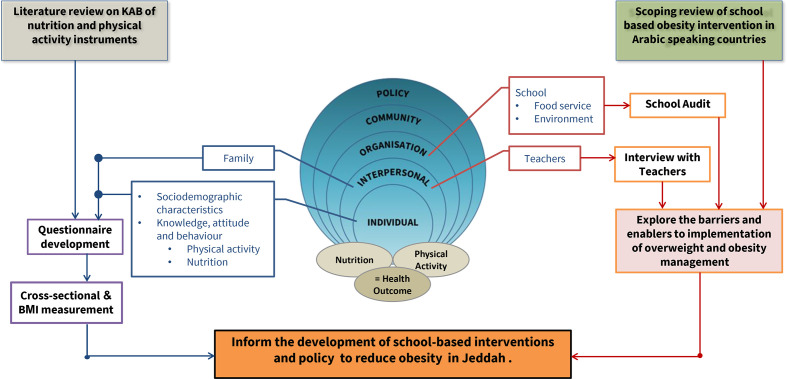

Major tenets of the SEM acknowledge and situate adolescents within their environment and further recognise the position of ecology or contextual elements for children within their family and wider social context.42 The theory posits that the health and health behaviours of individuals are interconnected with their surroundings, and that environment needs to be understood in order to explain health.40 42 43 In essence, the socioecological perspective considers a more comprehensive view of the influences on childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity.44 The SEM recognises influences at the student, interpersonal (family, peers and teachers), school environment, community and policy levels.45 The factors associated with childhood overweight and obesity are multifactorial and interconnected, hence the SEM will be used to inform this study. Figure 1 describes the interrelationship between the SEM and the study design.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework using socioecological model to inform the study design setting. KAB, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours.

Setting

The study will be conducted in Jeddah City, KSA in three boys’ and three girls’ intermediate schools. Schools will be randomly selected from 262 intermediate government schools, recruiting approximately even numbers of males and females. Students (grades 7–9; 12–15 years), teachers and principals will be invited to participate in the study. In KSA, all schools are single gender.46

Phase 1: scoping review

A scoping review will be initially conducted to understand school-based obesity prevention interventions in Arabic speaking countries. Population, intervention, control and outcomes (PICO) format47 will be used to guide the development of the review’s question, generating relevant keywords for searching and developing in inclusion and exclusion criteria. This review will consider school-based interventions focusing on overweight and obesity prevention (including promotion of healthy eating and physical activity) within schools in predominantly Arabic-speaking countries (n=22 countries) within the last 10 years. Finally, a systematic search and screening will be conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.48

Search strategy and study selection

Systematic searches of the following electronic databases will be undertaken through PubMed, Medline, Scopus, CINHAL, Cochrane, ERIC, EMBASE, ProQuest, EBSCO Host and Global Health and manual exploration of relevant publications will be conducted. School-based intervention studies will be included with keywords (Child or Adol*) and (Bahrain or Kuwait or Oman or Qatar or Saudi Arabia or United Arab Emirates or gulf countries or Gulf Cooperation Council or Algeria or Palestinian Territories or Comoros or Djibouti or Egypt or Iraq or Jordan or Lebanon or Libya or Mauritania or Morocco or Somalia or Sudan or Syria or Tunisia or Yemen) and school and (intervention or programme or curriculum or health promotion or health education) and (physical activity or exercise or diet or nutrition or food choices or obesity or overweight or BMI or or body weight). Inclusion criteria will be studies which focus on school-aged children from 5 to 18 years, interventions aiming to prevent overweight and obesity, school-based quantitative and/or qualitative intervention studies, peer-reviewed articles published in English or Arabic and articles for which full text is available. Systematic searching will be documented, and duplicates will be removed using reference management software (ie, EndNote X9). The relevant data extracted from each article will be systematically summarised and tabulated and will be analysed for intervention characteristics, measurable outcomes, and the enablers and barriers of the interventional studies.34

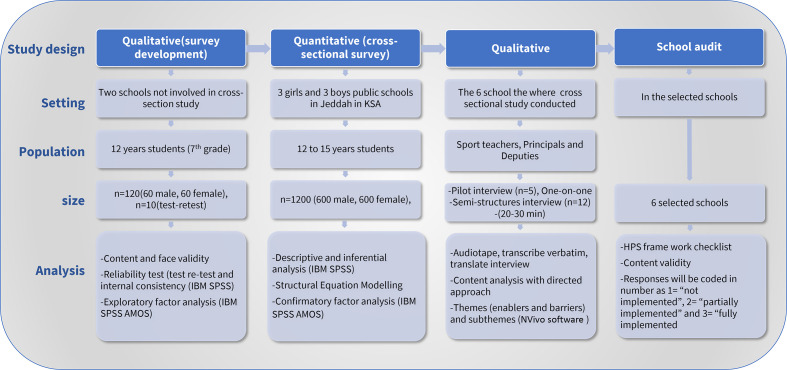

Phase 2: survey development

A self-report survey will be developed to measure demographics and KAB regarding physical activity and nutrition among grades 7–9 students (figure 2). The survey will be informed by the literature and where possible previously validated items will be used. The survey be tested for validity and reliability.49 Content validity testing of the survey will be conducted with experts (ie, public health academics with clinical and education backgrounds from KSA; n=6–8) initially in English and the final format in Arabic. The survey will be tested for reliability. A test–retest will be conducted in Jeddah KSA with seventh grade (aged 12) students (male, n=60 and female=60) from two schools (one male and one female) not involved in the main study. The survey will be administered by a research assistant in a classroom at a time convenient to the school in paper or online. The survey will be administered to the same 60 students 2 weeks after the initial survey administration. This pilot study will inform the researchers, the minimum and maximum time required to complete the survey.

Figure 2.

Processes and analysis of survey development and mixed-methodology instrumentation. KSA, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Instrumentation

Demographics including age, gender, grade level and parent education level will be collected. Physical activity knowledge will be measured using five questions adapted from a Malaysian study involving 8–11 year old children (responses ‘True’, ‘False’ and ‘I don’t know’).50 Attitudes towards physical activity will be measured using an eight question scale adapted from a university study in Gambia (Likert scale: strongly agree1 to strongly disagree).5 51 Physical activity behaviours will be measured using eight questions. The first question uses the SCREENS questionnaire which was originally developed for children aged 6–10 years in Denmark (SCREENS-Q). This question includes six-sub questions and focuses on time per day spent on different screen-related activities.52 The remaining five questions were adapted to the KSA intermediate school context from the Australian National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey which collected data about 5–17 years old. These questions focus on usual daily activity, level of activity and amount and type of sports activities provided at school.53

Nutrition knowledge will be measured using eight items adapted from a validated nutritional survey developed for use among urban South African adolescents (responses: true, false, I don’t know).54 55 Eight items adapted from an English survey for 11–12 years old will measure nutrition attitudes (Likert scale: strongly agree1 to strongly disagree).5 55 Nutrition-related behaviours will be measured using nine questions adapted from an Australian school students survey. These questions focus on types and approximate quantities of food consumed on a usual day. Questions focus of fruit, vegetable, bread and cereal, fast food, energy dense snacks, sugary drinks, milk and water consumption.56

Phase 3: mixed-methods study

Phase 3 will comprise the mixed-methods study which includes a cross-sectional survey and BMI measurements with grades 7–9 students. Individual interviews with physical education teachers and school principals and the administration of school environment audits will also be undertaken (figure 2).

Study population and sample size

Cross-sectional and BMI measurements

Of the 262 intermediate schools in Jeddah, six schools will be randomly selected. A random sample of six intermediate schools will be generated from six different geographical regions in Jeddah using SPSS random generated sample selection method. Intermediate Schools include students from grades 7 to 9. All students within participating classes from each school will be invited.

Principals will provide consent for the school to participate in the study. Parental consent and student assent will be required for individual student participation. Inclusion criteria will be children from grades 7 to 9 who assent to participate and for whom parental consent is provided. Students who are unable to take the survey for any reason and/or are unable to stand up long enough to have their height and weight measured (ie, students who are not cognitively or physically able to participate) will be excluded from the study.

In order to calculate sufficient sample size to ensure representativeness of the study population, the highest available prevalence of overweight and obesity (23.1%) reported among KSA children and adolescents in a study by El Mouzan et al,25 was used. The following formula was used for sample size calculation: Sample size (n)=Z12-α/2 Pq /d2.57 Based on the formula, the required minimum sample size for intermediate school (12–15 years old), is 273 participants. To factor in 10% non-response rate, a total of 300 students is required for this study. Since this study employed cluster sampling a design effect will be employed. A design effect usually ranges from 1 to 3.58 Therefore, the design effect of two will be used to reach a sample size of 600. Since this study is targeting both male and female students, the total estimated sample size will be 1200 students (600 males and 600 females).

Interview with school principals and sport teachers

We will aim to recruit six physical education teachers and six principals or deputy principals (one teacher and one principal/deputy from each school; n=12). Due to cultural reasons, the male principal researcher will conduct face-to-face interviews with male participants and phone interviews with the female participants.

School climate audit

The principal researcher (or the research assistant for female schools) will complete the school audit checklist with the school principal or deputy and one physical education teacher.

Data collection

Cross-sectional and BMI measurements

The validated self-administrated survey (developed in phase 2) will collect demographic information and physical activity and nutrition KAB. The self-report instrument will be administered via paper or online during class time by the principal researcher (or research assistant in the girls’ schools) with the assistance of the classroom teachers in each school.

The height and weight of consenting students will also be measured. The researcher will follow the international standards for anthropometric assessment.59 The BMI for age will be calculated.59 The principal investigator will take the measurements of the male students and female research assistant will be employed to measure female students and both will be trained in correct anthropometric measurement techniques. A calibrated digital measuring scale will be used, and the scale will be reset before measurement. The use of such digital scales has been supported for good accuracy with evidence.60 Student height will be measured using a portable stadiometer set up on a hard, flat surface.61 Privacy will be given to each child so that their measurements are known only to the person taking the measurements. The height and weight data measurement will be written on the individual survey forms.

Interview with school principals and sport teachers

Individual in-depth interviews will be conducted with physical education teachers and principals to explore their beliefs and perceptions of the barriers and enablers to the implementation of school-based interventions focusing on obesity prevention. This is expected to provide a richer understanding of the topic from the point of view of relevant school staff.

The questions will be informed by the results of the systematic review, the cross-sectional study and relevant literature,62–67 and a semistructured interview guide will be developed. The interview guide will be piloted with two teachers uninvolved in the study to estimate the time the interview can be expected to take and to obtain feedback on the clarity of the interview questions.

The semistructured one-on-one interviews will be audiotaped, transcribed verbatim, translated and will be reviewed by the researcher and supervisors to maintain dependability and determine credibility.68 The translation process will resume after transcription with an audioconverter Arabic to Arabic then the researcher will review all the resulting transcriptions and adjust for accuracy. The principal investigator will translate for the closest intended meaning based on his knowledge of English and Arabic then will get this checked by an Accredited English-Arabic translator.

School climate audit

A school climate audit tool will be developed from previous tools based on the HPS Framework33 69 and will be based on the three interrelated components of the HPS Framework: curriculum, teaching and learning; school organisation, ethos and environment; and partnerships and services.70–72 The tool will be adapted from the items from four studies with acceptable psychometric levels: a tool developed for multiple countries with almost perfect reliability (κ=0.80–0.96)70; an audit tool focusing on the walkability of school environments with average interrater reliability score from USA (κ=0.839)73; school audit tools used in the IDEA study in the USA74; and the Australian HPS school audit.72 The tool includes whole school strategies relevant to promoting good nutrition and physical activity.

Data analysis

Phase 2: survey analysis

Survey development (validity and reliability testing)

Validity and reliability during the survey development and the cross-sectional survey will be examined using different types of factor analysis as details are detailed below (figure 2).

Explanatory factor analysis

The initial construct validity of the instrument will be established through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), allowing the transformation of correlations among a set of observed variables into each of the six proposed subscales of overweight and obesity.75 EFA will be used to extract factors with eigenvalues>1, which will then be rotated to identify subscales or factors that best fit the instrument76 and decisions will be made if the items need to be excluded which is testing the initial construct validity of the instrument. The assumptions should be met where the number of participants is sufficient as literature states that three to 20 people per variable is sufficient to run this EFA analysis,77 the Kaiser-Mayer-Olkin (>0.50) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p<0.05). For the sample size of 120 students, the sufficient factor loading is above 0.50.78

Internal consistency

Once the factors are extracted using the EFA, internal consistency of each factor within the instrument and its items will be measured using Cronbach’s alpha, an alpha greater than or equal to 0.7 will be considered adequate.79

Test–retest reliability

The scores and mean scores obtained during the two surveys will be calculated with the Pearson product–moment correlation analysis. Spearman’s r, a measure of agreement between scores on different administrations of the instrument will be calculated and the correlation coefficient between 0.7 and 1.0 indicate that the instrument is reliable or shows consistency across time.80 81

Phase 3: mixed-methods study

Cross-sectional and BMI measurements

Confirmatory factor analysis

In this phase, the construct validity will be assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). For confirmatory content analysis and explanatory analysis more than 500 or 10 samples per item are sufficient.82 In our study, the sample size calculated is 1200 which is sufficient to undergo CFA. This construct validity using CFA will indicate whether the subscales of overweight and obesity identified in phase 2 are valid and is achieved when the fitness indexes is achieved to the required level: χ2 (p>0,05), χ2/df<3.0, root mean square error of approximation <0.08), Goodness-of-Fit Index >0.90, Comparative Fit Index >0.90, Normed Fit Index>0.90.83 The second stage of EFA analysis at this phase is to identify and estimate whether it fits the model and the df as well. The CFA will be analysed using a powerful structural equation modelling software IBM SPSS Amos. Finally, the model will be rearranged revised to improve the fit as indicated and Akaike information criterion will be used to compare between model during the fitting process.84

Descriptive data analysis

During data entry, exploratory data analysis will be conducted to identify outliers, missing data, describe and check the assumption of normality and distribution of continuous data using histogram and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and Shapiro-Wilk test.85 The central tendencies will be expressed in mean, median, SD and IQR for continuous data while frequencies and percentages will be used to express data for categorical variables. χ2 tests will assess the associations between each independent variable and overweight and obesity.

Inferential data analysis

Initially, all variables will be analysed univariately and those with p value more than 0.25 will be included in the model to avoid the possibility of residual cofounders.57 Logistic regression will be employed to analyse the predictors of obesity and overweight (BMI measurements). The significance level will be set at p<0.05 at 95% CI. Data analysis will be carried out using the SPSS software V.26.0.

Interview with school principals and sport teachers

Content analysis will explore perceptions and experiences, generating rich and in-depth information on the underlying studied phenomena.86 Themes will be identified, and responses coded to elicit shared meanings of perceptions across interviews and to guide the researchers in reporting the results. For this purpose, directed thematic analysis approach will be employed.87 Common themes and subthemes will be identified based on the interview responses.88 The qualitative data will be managed using software package NVivo V.12. When the interview is transcribed, it will be sent back to a sample of consenting participants for verification.

School climate audit

The school climate audit will be reviewed by health promotion and education experts from Australia and KSA to determine face and content validity. The tool will be tested with two teachers from the two Intermediate Schools in Jeddah conducting the student survey test–retest. The audit responses will be classified as ‘implemented’, ‘partially implemented’ and ‘not implemented’ and will be tabulated and evaluated section by section.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or public involved.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been granted through Curtin University’s Human Research Ethics Committee (HRE2020-0337) and from the KSA Ministry of Education (4181827686). Initially consent will be obtained from the principals of each school involved to allow their school to participate in the study. Individual consent will be sought from teachers, principal/deputy and parents and assent sought from students. Participant information sheets will be provided for the principal describing the school’s involvement. All participants (teachers, principals/deputies, students) and parents will be provided individual participant information sheets describing the study and highlighting the voluntary nature of the study.

All information collected from participating schools, principals, teachers and students will be de-identified. Students completing the survey will be assigned an identification number/code stipulated in the survey prior to data collection so that their BMI can be linked to their survey responses. If surveys are conducted on paper they will be scanned, and originals stored securely until appropriately disposed. All electronic data will be stored on a secure password protected network which can only be accessed by the researchers. Data will be appropriately disposed of after a minimum of 7 years after project completion or until the participant has reached 25 years of age.89 Results will be presented as aggregate and there will be no identification of individuals.

This study provides a unique opportunity to inform school-based interventions in KSA. Recommendations will be made to the KSA Ministry of Education regarding the implementation of whole school interventions. Findings will be used to advocate for school-based curriculum and policy change at a national level. The tools developed, and the learnings from the study will be made available to individual schools to support school-based planning. Findings will be published as a doctoral thesis, in peer-review publications and at conferences. In addition, key findings will be shared with the KSA Ministry of Education, participating schools and to the broader school community through newsletters.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed significantly to the conceptualisation, design and drafting of this protocol. NSA, conceived the study which was developed with guidance and support from SB and LP. NSA drafted the paper which was critically reviewed and edited by SB and LP. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research project is funded by Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia in Australia (Award/Grant number is not applicable) and administered through the doctoral programme run at Curtin University’s School of Public Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. WHO . Global Health Observatory (GHO) data- Overweight and obesity -Prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents [Internet], 2018. Available: https://www.who.int/gho/ncd/risk_factors/overweight_obesity/obesity_adolescents/en/

- 2. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) . Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet 2017;390:2627–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sutaria S, Devakumar D, Yasuda SS, et al. Is obesity associated with depression in children? systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child 2019;104:64–74. 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nemiary D, Shim R, Mattox G, et al. The relationship between obesity and depression among adolescents. Psychiatr Ann 2012;42:305–8. 10.3928/00485713-20120806-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Danielsen YS, Stormark KM, Nordhus IH, et al. Factors associated with low self-esteem in children with overweight. Obes Facts 2012;5:722–33. 10.1159/000338333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bechard LJ, Rothpletz-Puglia P, Touger-Decker R, et al. Influence of obesity on clinical outcomes in hospitalized children: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:476–82. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO . Obesity : Preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organization: Technical Report Series [Internet]. WHO Technical Report Series, no. 894, 2000. Available: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/WHO_TRS_894/en/ [PubMed]

- 8. Fang X, Zuo J, Zhou J, et al. Childhood obesity leads to adult type 2 diabetes and coronary artery diseases. Medicine 2019;98:e16825 http://insights.ovid.com/crossref?an=00005792-201908090-00076 10.1097/MD.0000000000016825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brady TM. Obesity-related hypertension in children. Front Pediatr 2017;5:197. 10.3389/fped.2017.00197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Onyemaechi NO, Anyanwu GE, Obikili EN, et al. Impact of overweight and obesity on the musculoskeletal system using lumbosacral angles. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:291–6. 10.2147/PPA.S90967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carbone S, Canada JM, Billingsley HE, et al. Obesity paradox in cardiovascular disease: where do we stand? Vasc Health Risk Manag 2019;15:89–100. 10.2147/VHRM.S168946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Buttitta M, Iliescu C, Rousseau A, et al. Quality of life in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a literature review. Qual Life Res 2014;23:1117–39. 10.1007/s11136-013-0568-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krukowski RA, West DS, Philyaw Perez A, et al. Overweight children, weight-based teasing and academic performance. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009;4:274–80. 10.3109/17477160902846203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gunnell DJ, Frankel SJ, Nanchahal K, et al. Childhood obesity and adult cardiovascular mortality: a 57-y follow-up study based on the Boyd Orr cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:1111–8 https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/article/67/6/1111-1118/4666016 10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Franks PW, Hanson RL, Knowler WC. Cardiovascular risk factors, and premature death. N Engl J Med 2010;362:485–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sonntag D. Why early prevention of childhood obesity is more than a medical concern: a health economic approach. Ann Nutr Metab 2017;70:175–8 https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/456554 10.1159/000456554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sonntag D, Ali S, De Bock F. Lifetime indirect cost of childhood overweight and obesity: a decision analytic model. Obesity 2016;24:200–6. 10.1002/oby.21323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sonntag D, Ali S, Lehnert T, et al. Estimating the lifetime cost of childhood obesity in Germany: results of a Markov model. Pediatr Obes 2015;10:416–22. 10.1111/ijpo.278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Musaiger AO, Hassan AS, Obeid O. The paradox of nutrition-related diseases in the Arab countries: the need for action. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:3637–71. 10.3390/ijerph8093637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ôunpuu S, et al. Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet 2005;366:1640–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Musaiger AO, Al-Mannai M, Al-Lalla O, et al. Obesity among adolescents in five Arab countries; relative to gender and age. Nutr Hosp 2013;28:1922-5. 10.3305/nutrhosp.v28in06.6412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ALNohair S. Obesity in Gulf countries. Int J Health Sci 2014;8:79–83 http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4039587&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.12816/0006074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Al-Muhaimeed AA, Dandash K, Ismail MS, et al. Prevalence and correlates of overweight status among Saudi school children. Ann Saudi Med 2015;35:275–81. 10.5144/0256-4947.2015.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Ghamdi S, Shubair MM, Aldiab A, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity based on the body mass index; a cross-sectional study in Alkharj, Saudi Arabia. Lipids Health Dis 2018;17:134. 10.1186/s12944-018-0778-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Mouzan MI, Foster PJ, Al Herbish AS, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in Saudi children and adolescents. Ann Saudi Med 2010;30:203–8. 10.4103/0256-4947.62833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Al-Hussaini A, Bashir MS, Khormi M, et al. Overweight and obesity among Saudi children and adolescents: where do we stand today? Saudi J Gastroenterol 2019;25:229 http://www.saudijgastro.com/text.asp?2019/25/4/229/259848 10.4103/sjg.SJG_617_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moalla N, Al Moraie D. Dietary patterns in Saudi Arabian adults residing in different geographical locations in Saudi Arabia and in the UK in relation to heart disease risk. Newcastle University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Aljoudi A, Mwanri L, Al Dhaifallah A. Childhood obesity in Saudi Arabia: opportunities and challenges. Saudi J Obesity 2015;3:2. 10.4103/2347-2618.158684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in eastern Mediterranean region: prevalence and possible causes. J Obes 2011;2011:1–17. 10.1155/2011/407237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sahoo K, Sahoo B, Choudhury AK. Childhood obesity: causes and consequences. J Fam Med Prim care 2015;4:187–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Musaiger AO, Al Hazzaa HM, Al-Qahtani A, et al. Strategy to combat obesity and to promote physical activity in Arab countries. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2011;4:89–97. 10.2147/DMSO.S17322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen Y, Ma L, Ma Y, et al. A national school-based health lifestyles interventions among Chinese children and adolescents against obesity: rationale, design and methodology of a randomized controlled trial in China. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1–10. 10.1186/s12889-015-1516-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Langford R, Bonell C, Jones H, et al. The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: a Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:1–15. 10.1186/s12889-015-1360-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bennett L, Burns S. Implementing health-promoting schools to prevent obesity. Health Educ 2020;120:197–216 https://www.emerald.com/insight/0965-4283.htm 10.1108/HE-11-2019-0054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Al-Hazzaa HM. Prevalence and trends in obesity among school boys in central Saudi Arabia between 1988 and 2005. Saudi Med J 2007;28:1569–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Al-Hazzaa HM, Al-Sobayel HI, Abahussain NA, et al. Association of dietary habits with levels of physical activity and screen time among adolescents living in Saudi Arabia. J Hum Nutr Diet 2014;27:204–13. 10.1111/jhn.12147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schoon M, Der LSV. The shift toward social-ecological systems perspectives : insights into the human-nature relationship. Natures Sci Sociétés 2015;23:166–74. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American heart association Council on epidemiology and prevention, interdisciplinary Committee for prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science). Circulation 2008;118:428–64. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988;15:351–77. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. WHO . Regional guidelines: development of health-promoting schools - a framework for action [Internet], 1996. Available: http://iris.wpro.who.int/handle/10665.1/1435

- 42. Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:307–26 http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McLaren L, Hawe P. Ecological perspectives in health research. J Epidemiol Community Health 2005;59:6–14. 10.1136/jech.2003.018044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Townsend N, Foster C. Developing and applying a socio-ecological model to the promotion of healthy eating in the school. Public Health Nutr 2013;16:1101–8. 10.1017/S1368980011002655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Golden SD, Earp JAL. Social ecological approaches to individuals and their contexts: twenty years of health education & behavior health promotion interventions. Health Educ Behav 2012;39:364–72. 10.1177/1090198111418634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wiseman AW, Sadaawi A, Alromi NH. Educational indicators and national development in Saudi Arabia. Paper presented at the 3rd IEA International Research Conference; 18-20 Sept, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Higgins JPT, Sterne JAC, Savović J. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2016:1–4 http://www.nccmt.ca/resources/search/280 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cecchetto FH, Pellanda LC. Construction and validation of a questionnaire on the knowledge of healthy habits and risk factors for cardiovascular disease in schoolchildren. J Pediatr 2014;90:415–9 http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0021-75572014000400415 10.1016/j.jped.2013.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shah A, Aishath OA, Farhana H. Knowledge, attitude and practice regarding healthy diet and physical activity among overweight or obese children. Int J Public Heal Clin Sci 2018;5. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bajinka O, Badjan M, Awareness AT. Attitude and practice of students in the public health and education department, University of the Gambia. Acta Sci Med Sci 2019;3:52–62. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Klakk H, Wester CT, Olesen LG, et al. The development of a questionnaire to assess leisure time screen-based media use and its proximal correlates in children (SCREENS-Q). BMC Public Health 2020;20. 10.1186/s12889-020-08810-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines and the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines [Internet]. Australian Government Department of Health, 2013. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/4364.0.55.0042011-12?OpenDocument [Google Scholar]

- 54. Whati LH, Senekal M, Steyn NP, et al. Development of a reliable and valid nutritional knowledge questionnaire for urban South African adolescents. Nutrition 2005;21:76–85. 10.1016/j.nut.2004.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Frobisher C, Maxwell SM. The attitudes and nutritional knowledge of a group of 11–12 year olds in Merseyside. Int J Health Promot Educ 2001;39:121–7. 10.1080/14635240.2001.10806187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Health NSW. School students behaviour survey: HealthStats NSW. 2016;1–24. Available: https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/surveys/student/Documents/student-health-survey-2017-quest.pdf

- 57. Lemeshow S, Hosmer DW, Klar J. Adequacy of sample size in health studies. New York, USA: WHO, 1990: 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shackman G. Sample size and design effect. Retrieved from [Internet]. Chapter of American Statistical Association. NYS DOH, 2001. Available: http://faculty.smu.edu/slstokes/stat6380/deffdoc.pdf

- 59. Stewart A, Marfell-Jones M, Olds T. International standards for anthropometric assessment. International Society for the Advancement of Kinanthropometry. Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yorkin M, Spaccarotella K, Martin-Biggers J, et al. Accuracy and consistency of weights provided by home bathroom scales. BMC Public Health 2013;13:1–5. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Himes JH. Challenges of accurately measuring and using BMI and other indicators of obesity in children. Pediatrics 2009;124:s3–22. 10.1542/peds.2008-3586D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Howard-Drake EJ, Halliday V. Exploring primary school headteachers’ perspectives on the barriers and facilitators of preventing childhood obesity: Table 1. J Public Health 2016;38:44–52. 10.1093/pubmed/fdv021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schuler BR, Saksvig BI, Nduka J, et al. Barriers and Enablers to the implementation of school wellness policies: an economic perspective. Health Promot Pract 2018;19:873–83. 10.1177/1524839917752109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Clarke J, Fletcher B, Lancashire E, et al. The views of stakeholders on the role of the primary school in preventing childhood obesity: a qualitative systematic review. Obes Rev 2013;14:975–88. 10.1111/obr.12058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Della Torre Swiss SB, Akré C, Suris J-C. Obesity prevention opinions of school stakeholders: a qualitative study. J Sch Health 2010;80:233–9. 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00495.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Patino-Fernandez AM, Hernandez J, Villa M, et al. School-based health promotion intervention: parent and school staff perspectives. J Sch Health 2013;83:763–70. 10.1111/josh.12092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Schetzina KE, Dalton WT, Lowe EF, et al. Developing a coordinated school health approach to child obesity prevention in rural Appalachia: results of focus groups with teachers, parents, and students. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sutton J, Austin Z. Qualitative research: data collection, analysis, and management. Can J Hosp Pharm 2015;68:226–31. 10.4212/cjhp.v68i3.1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Langford R, Bonell C, Jones H, et al. Obesity prevention and the health promoting schools framework: essential components and barriers to success. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:15. 10.1186/s12966-015-0167-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Broyles ST, Drazba KT, Church TS, et al. Development and reliability of an audit tool to assess the school physical activity environment across 12 countries. Int J Obes Suppl 2015;5:S36–42. 10.1038/ijosup.2015.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Katzmarzyk PT, Barreira TV, Broyles ST, Champagne CM, Chaput J-P, Tudor-Locke C, et al. The International study of childhood obesity, lifestyle and the environment (ISCOLE): design and methods. BMC Public Health 2013;13:900. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. WAHPSA . Health promoting schools framework [Internet], 2014. Available: http://www.hpb.gov.sg/HOPPortal/programmes-article/3128

- 73. Lee C, Kim HJ, Dowdy DM, et al. TCOPPE school environmental audit tool: assessing safety and walkability of school environments. J Phys Act Health 2013;10:949–60 www.JPAH-Journal.com 10.1123/jpah.10.7.949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lytle LA. Examining the etiology of childhood obesity: the idea study. Am J Community Psychol 2009;44:338–49. 10.1007/s10464-009-9269-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Brown TA, Moore MT. Handbook of structural equation modeling. : Confirmatory factor analysis. New York, NY, US: The Guilford Press, 2012: 361–79. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Taherdoost H. Validity and reliability of the research instrument; how to test the validation of a Questionnaire/Survey in a research. Int J Acad Res Manag 2016;5:28–36. 10.2139/ssrn.3205040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mundfrom DJ, Shaw DG, Ke TL. Minimum sample size recommendations for conducting factor analyses. Int J Test 2005;5:159–68 https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hijt20 10.1207/s15327574ijt0502_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78. JFH J, Black WC, Babin BJ. Exploratory Factor Analysis. In: Multivariate data analysis hair black babin Anderson. 7 edn, 2014: 89–150. www.pearsoned.co.uk [Google Scholar]

- 79. Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach ’ S alpha. Int J Med Educ 2011;2:53–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Gliner JA, Morgan GA, Harmon RJ. Measurement reliability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:486–8. 10.1097/00004583-200104000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Weiner J. Measurement : reliability and validity measures, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics [Internet]. 6th Edition, 2013. Available: https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Tabachnick-Using-Multivariate-Statistics-6th-Edition/PGM332849.html

- 83. Awang Z. Validating the Measurement Model: CFA. : SEM made simple : a gentle approach to learning structural equation modeling. MPWS Rich Publication, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 84. Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the Fit of Structural Equation Models: Tests of Significance and Descriptive Goodness-of-Fit Measures. : Methods of psychological research online. ., 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics [Internet]. Fourth edi. London: SAGE Publications Inc, 2013. Available: https://books.google.co.nz/books?hl=en&lr=&id=c0Wk9IuBmAoC&oi=fnd&pg=PP2&ots=LbGnGG-u3H&sig=A6dblN8tUIo9xYdhoPn2z40aY3c&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- 86. Lichtman M. Qualitative research in education: a user’s guide. 2 edn. California: sage, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. : Qualitative research in psychology. In, 2006: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Vaismoradi M, Jones J, Turunen H, et al. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurs Educ Pract 2016;6. 10.5430/jnep.v6n5p100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Western Australian university sector disposal authority, 2013. Available: http://www.sro.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/western_australian_university_sector_disposal_authority_sd2011011.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.