Abstract

Introduction

Ensuring safety of the mother along with the delivery of a healthy baby is the ultimate objective of all obstetricians. Labour induction is increasingly becoming one of the most common obstetric interventions in India. The aim of the study is to compare the feto-maternal outcome of induction of labour versus spontaneous labour in postdated women.

Method

This was a prospective observational comparative study. A total of 100 patients were selected, 50 who had induction of labour (study group) and 50 who had spontaneous labour (control). A structured proforma and partographs were used to obtain data.

Result

42% nulliparous women had induction of labour as compared to 29% multiparous women. The rate of cesarean section (58%) was substantially higher in those who had been induced. Non-progression of labour or failure of induction was the commonest indication for cesarean section. Post-partum haemorrhage was a complication found more commonly in the study group. Perineal tears were found more commonly in the control group.

The mean birth weight of babies born to mothers who had been induced was significantly higher than that of those born to women who went into spontaneous labour. The APGAR scores were comparable in both groups. There was a higher incidence of hyperbilirubinemia in the study group.

Conclusion

Although induction of labour is a relatively safe procedure, some foetal and maternal risks were found to be higher in induced group than in those with spontaneous labour. Induction must be carried out only when necessary and not as a routine elective procedure.

Keywords: Induction of labour, Spontaneous labour, Failure of induction, Postdated, Cesarean section

Introduction

Ensuring safety of the mother along with the delivery of a healthy baby is the ultimate objective of all obstetricians. Reduction in maternal and infant mortality also finds a mention in the Sustainable Development Goals of India [1]. More than 500 women die annually due to labour-related complications and about 4 million foetuses are stillborn annually in developing countries [2]. As per the SRS statistical report 2018, perinatal mortality rate is at an alarming 22 per 1000 live births. Labour induction is increasingly becoming one of the most common obstetric interventions in these cases. The prevalence of induction is up to 22% in India [3]. Yet the WHO recommendation on labour induction cites weak evidence due to lack of adequate research [4]. A few prospective, randomized controlled trials have shown labour induction in postdated women to have numerous beneficial effects, lowering the incidence of cesarean section as well as adverse foetal outcomes [5–7]. However, some research also indicates that labour induction is itself a risk factor leading to an increase in maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality including post-partum haemorrhage due to atony and, an increased risk of failure of induction necessitating an emergency cesarean section and longer duration of NICU stay [8–10]. Hence, there is a perilous uncertainty about the effect of induction. Determining the effect of elective induction of labour on maternal and neonatal outcomes is of paramount importance. The aim of the study is to compare the feto-maternal outcome of induction of labour versus spontaneous labour in postdated women in the busy labour ward of a tertiary care hospital. This includes maternal outcomes such as the number of emergency cesarean section, meconium-stained liquor, post-partum haemorrhage and cord prolapse among other in the induced labour groups as compared to their counterparts. Neonatal outcomes such as NICU admission for hyperbilirubinemia, respiratory distress have also been compared.

Objectives

1. To compare the maternal outcome in uncomplicated postdated women with induced labour versus those in spontaneous labour.

2. To compare the neonatal outcome in induced versus spontaneous labour in uncomplicated postdated women.

Method

This was a prospective observational comparative study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. A written informed consent was acquired from each patient prior to inclusion. This study was conducted in postdated women who had induction of labour and those with a comparable gestational age in spontaneous labour.

In this observational study, patients admitted over a 3-month duration were evaluated and a sample size of 100 was selected which was approximately 10% of the total patients studied. 50 who had induction of labour (study group) were compared with 50 who had spontaneous labour as control. Inclusion criteria included women with a live singleton foetus, vertex presentation with gestational age > 39 weeks + 6 days. Exclusion criteria included patients with complications such as preeclampsia, eclampsia, gestational diabetes mellitus, pregnancy-induced hypertension, placenta praevia, abruptio placenta, oligohydramnios, polyhydramnios, cephalo pelvic disproportion, malpresentation, previous LSCS, patients with underlying medical conditions that could affect the outcome of the pregnancy, patients with a medical contraindication to induction of labour and patients with known foetal abnormalities including intrauterine growth restriction, foetal congenital anomalies, hydrocephalus or cystic hygroma and foetal death diagnosed during the duration of pregnancy. Gestational age was determined by ultrasonography in the first trimester of pregnancy.

A structured proforma was used to obtain demographic data, parity and gestational age. Labour progress of both groups was charted on a partograph. Intrauterine foetal heart rate, uterine activity and maternal vital signs were regularly monitored. Induction was done using PGE2 intracervical gel 0.5 mg within 24 h of admission but not before 40 weeks + 0 days. For this study, successful induction was defined as an uncomplicated vaginal delivery and failed induction as inability to achieve cervical dilatation of 4 cm or more with 90% effacement after 12 h of dinoprostone gel and oxytocin administration.

Statistical Analysis

Data obtained were statistically studied using Chi-square test to evaluate associations and statistical significance between variables. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant at 95% confidence interval.

Result

Over a period of 3 months, 393 patients underwent induction of labour of which 50 patients met the selection criteria for this study (study group). Fifty women who had spontaneous labour were selected consecutively as the control group. The mean age of the participants was found to be 25.83 years for the study group and 29.20 years for the control group. This difference was statistically significant ( t = 2.88734, P = 0.02395).

42% of the nulliparous women in the study underwent induction of labour and 28% went into spontaneous labour, whereas in the multiparous women 29% underwent induction of labour while 36% had spontaneous onset of labour. This difference is statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

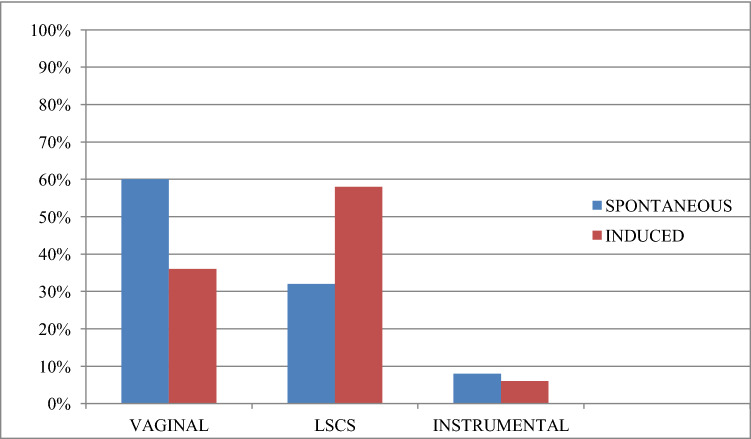

The rate of vaginal delivery was 36% in the study group and 60% in the control group. The rate of Cesarean section was 58% in the study group and 32% in the control. This difference bears statistical significance (P = 0.031771). Instrumental delivery was 6% and 8% in the respective groups (Tables 1, 2; Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Type of delivery in the control group and study group

| Mode of delivery | Spontaneous (N = 50) |

Induced (N = 50) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal |

30 (60%) |

18 (36%) |

.01428 |

| Instrumental |

4 (8%) |

3 (6%) |

.59612 |

| LSCS |

16 (32%) |

29 (58%) |

.00614 |

Table 2.

Mode of delivery

| Mode of delivery | Spontaneous | Induced | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal | Nullipara |

3 (20%) |

5 (23.81%) |

.0735 |

| Multipara |

26 (72.22%) |

11 (37.93%) |

.0055 | |

| Instrumental | Nullipara |

4 (26.67%) |

1 (14.28%) |

.4534 |

| Multipara |

1 (2.78%) |

2 (66.67%) |

.7779 | |

| LSCS | Nullipara |

7 (31.81%) |

15 (71.43%) |

.0016 |

| Multipara |

9 (25%) |

16 (55.17%) |

.0208 | |

| Total | Nullipara | 14 | 21 | |

| Multipara | 36 | 29 |

Fig. 1.

Comparing the type of delivery in spontaneous versus induced labour

Maternal complications included post-partum haemorrhage- 14% in the study group and 2% in the control group (P = 0.0271). Complications of no statistical significance included perineal lacerations (excluding episiotomies) 2% in the study group and 4% in the control group and sepsis 16% in the study group and 14% in the control group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Maternal complications

| Complication | Spontaneous | Induced | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-partum haemorrhage |

1 (2%) |

7 (14%) |

8 | .0271 |

| Perineal tear |

2 (4%) |

1 (2%) |

3 | .5552 |

| SEPSIS |

2 (4%) |

3 (6%) |

5 | .64552 |

The most frequent indication for Cesarean section was non-progression of labour: 93.10% in the study group and 62.50% in the control which was found to be statistically significant (P = 0.01016). Other indications which did not have statistical significance included foetal distress: 6.90% and 25%, cord prolapse: 0 and 6.25% and meconium-stained amniotic fluid: 6.25% and 6.45% in the study and control groups, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Indication for LSCS

| Indication for LSCS | Spontaneous | Induced | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-progression of labour |

10 (62.50%) |

27 (93.10%) |

.4899 |

| Foetal distress |

4 (25%) |

2 (6.90%) |

.08726 |

| Cord prolapse |

1 (6.25%) |

0 | .17384 |

| Meconium-stained amniotic fluid |

2 (6.45%) |

1 (6.25%) |

.3436 |

The incidence of foetal distress is low in both the study and control groups because high risk pregnancies were excluded from this study

The mean birth weight was 2871.86 kg in the study group and 2473.04 kg in the control group. This was statistically significant (t = −3.17984 P = 0.000995). There was no statistical significance in the number of NICU admissions: 10% in the study group and 8% in the control group. Neonatal complications noted were hyperbilirubinemia 8% and 2% and meconium aspiration 0 and 2% in the study and control groups, respectively. The incidence of respiratory distress was 4% in the study and control groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Neonatal complications

| Complication | Spontaneous | Induced | Total | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory distress |

2 (4%) |

2 (4%) |

4 | 1 |

| Hyperbilirubinemia |

1 (2%) |

4 (8%) |

5 | .16758 |

| Meconium aspiration |

1 (2%) |

0 | 1 | .3125 |

| Total no of complications |

4 (8%) |

6 (12%) |

10 | .50286 |

Discussion

The aim of induction is to achieve a safe and successful vaginal delivery. A risk benefit analysis to gain the best outcome is made in each individual case. In this study, it was observed that considerably fewer number of nulliparous women (28%) went into spontaneous labour when compared to multiparous women (72%). Another interesting fact that emerged from this study is that the average age of the study group was 25.83 years, appreciably lower than that of the control group, i.e. 29.20 years. This is in contrast to a study conducted by Abisowo et al when the mean age group of patients who were induced was found to higher [9].

When the modes of delivery were compared, it was found that the rate of cesarean section was substantially higher in those patients who had been induced (58%) versus that for spontaneous labour (32%) and the rates of vaginal deliveries were notably higher in those who went into spontaneous labour. This difference was even more marked in nulliparous women where 71.43% of those who had been induced underwent a cesarean section. This was found to be consistent with multiple studies which concluded that induction of labour increased the frequency of cesarean section [8, 9, 11, 12]. This was also, however, in contrast to several other studies which stated that induction of labour decreased the rates of cesarean section [5–7, 13]. It is imperative to note here that while the goal of induction was to facilitate a successful vaginal delivery, induction has been shown to increase the rate of cesarean section in both nulliparous and multiparous women. Non-progression of labour or failure of induction was the commonest reason for cesarean section.

Post-partum haemorrhage was a complication found more commonly in the study group (14%) than in the control group (2%). It resulted from uterine hyper stimulation and post-partum uterine exhaustion predisposing to atony of the uterus. Perineal tears, however, were found to be more common in the control group, a finding similar to those observed in other studies [13, 14].

The mean birth weight of babies born to mothers who had been induced was found to be significantly higher than the mean birth weight of those born to women who went into spontaneous labour. The neonatal APGAR scores were comparable in both groups with no statistically significant variation. It is, however, pertinent to note that a higher proportion of neonates born via induction of labour beyond 40 weeks of gestation had a better APGAR score compared to those who underwent spontaneous labour beyond 40 weeks. This finding is consistent with the results of other studies [13, 15, 16]. Postdatism is a known risk factor for foetal morbidity and mortality and prolonging the pregnancy could further increase the risk of foetal complications [17]. NICU admissions were found to be more in the control group (10%) than in those born via induction of labour (8%). However, there was a higher incidence of hyperbilirubinemia in the study group (8%) than the control group (2%). This needs further research.

The optimal timing for offering induction of labour to a postdated woman warrants more extensive research [15]. Although induction of labour is a relatively safe procedure, some foetal and maternal risks were found to be higher than in those with spontaneous labour. The indications of induction and potential maternal and foetal outcomes as well as resources available at the institution must be taken into account before inducing a patient. Induction must be carried out only when deemed necessary and not as a routine elective procedure.1

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The questionnaire and methodology of the study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital. (IEC/97/18).

Setu Dagli

is an intern at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Neonatology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital with a number of publications, presentations and academic achievements. She is currently working under the highly acclaimed Gynecologist, Dr. Michelle Fonseca.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Informed consent

Written informed consent was taken from all the participants of the study prior to collection of data.

Funding

No funding from any individual or organisation was used during this study.

Footnotes

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee on January 24th, 2019 (IEC/97/18). All participants have given informed written consent before taking part in the study.

Declaration of conflict of interest: All the authors declare that they have no financial relationship with any organization that may have an interest in the presented work; no other relationships or activities that could influence the work submitted.

Setu Dagli is an Intern in Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital, Sion West, Mumbai, India; Michelle Fonseca is a Professor in department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Lokmanya Tilak Municipal Medical College and General Hospital, Sion West, Mumbai, India

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Setu Dagli, Email: setudagli1905@gmail.com.

Michelle Fonseca, Email: michellefonseca@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals. World Health Organization; 2016.

- 2.Ade-Ojo IP, Akintayo AA. Induction of labour in the developing countries–an overview. J Med MedSci. 2013;4(7):258–262. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathy P, Pati T, Baby P, et al. Prevalence and predictors of failed Induction. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2016;39(2):189–194. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang J, Kapp N, Dragoman M, et al. WHO recommendations for misoprostol use for obstetric and gynecologic indications. Int J Gynecol & Obstet. 2013;121(2):186–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caughey AB, Sundaram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labour versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):252–263. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babu S, Manjeera ML. Elective induction versus spontaneous labour at term: prospective study of outcome and complications. Int J ReprodContraceptObstetGynecol. 2017;6:4899–4907. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wennerholm UB, Hagberg H, Brorsson B, et al. Induction of labour versus expectant management for post-date pregnancy: is there sufficient evidence for a change in clinical practice? ActaObstetGynecolScand. 2009;88(1):6–17. doi: 10.1080/00016340802555948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simpson KR, Thorman KE. Obstetric conveniences: elective induction of labour, cesarean birth on demand, and other potentially unnecessary interventions. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2005;19(2):134–144. doi: 10.1097/00005237-200504000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abisowo OY, Oyinyechi AJ, Olusegun FA, et al. Feto-maternal outcome of induced versus spontaneous labour in a Nigerian Tertiary Maternity Unit. Trop J Obstet and Gynaecol. 2017;34(1):21–27. doi: 10.4103/TJOG.TJOG_59_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orji EO, Olabode TA. Comparative study of labour progress and delivery outcome among induced versus spontaneous labour in the nulliparous women using modified WHO partograph. Niger J ObstetGynaecol. 2008;3:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selo-Ojeme D, Rogers C, Mohanty A, Zaidi N, Villar R, Shangaris P, et al. Is induced labour in the nullipara associated with more maternal and perinatal morbidity? Arch GynecolObstet. 2011;284(2):337–341. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1671-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwakume EY, Ayarte RP. The use of misoprostol for induction of labour in a low resource setting. Trop J ObstetGynaecol. 2002;19:78–81. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ekele BA, Oyetunji JA. Induction of labour at usmandanfodiyo university teaching hospital. Sokoto Trop J ObstetGynaecol. 2002;19:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durodola A, Kuti O, Orji EO, et al. Rate of increase of Oxytocin dose on the outcome of labour induction. Int J ObstetGynaecol. 2005;10:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Middleton P, Shepherd E, Crowther CA. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2018 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004945.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caughey AB, Sunduram V, Kaimal AJ, et al. Systematic review: elective induction of labour versus expectant management of pregnancy. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:252–263. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulmezoglu AM, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Induction of labour for improving birth outcomes for women at or beyond term. Cochrane Database Sys Rev 2006;4:CD004945. [DOI] [PubMed]