Abstract

Bone mass is regulated by osteoblast-mediated bone formation and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption. Osteoporosis is a bone metabolism disorder in which bone mass decreases due to increased bone resorption rather than bone formation. We focused on the traditional plant Alpinia zerumbet in Okinawa, Japan, and searched for promising compounds for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Pinocembrin isolated from the leaves of A. zerumbet showed enhanced alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and mineralization and increased mRNA expression of osteoblast-related genes Alp and Osteocalcin (Ocn) in MC3T3-E1 cells. Pinocembrin increased the mRNA expression of Runx2 and Osterix, which are important transcription factors in osteoblast differentiation, and the mRNA expression of Dlx5 and Msx2, which are enhancers of these transcription factors. The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonist noggin, its receptor kinase inhibitor LDN-193189 and p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 attenuated pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity. Pinocembrin increased the mRNA of Bmp-2 and its target gene Id1. In addition, the estrogen receptor (ER) inhibitor ICI182780 suppressed pinocembrin-stimulated ALP activity. Pinocembrin may increase BMP-2 expression via ER. Then, the BMP-2 promotes osteoblast specific genes expression and mineralization through both Smad-dependent and independent pathway following Runx2 and Osterix induction. Our findings suggest that pinocembrin has bone anabolic effects and may be useful for the prevention and treatment of bone metabolic diseases such as osteoporosis.

Keywords: Alpinia zerumbet, Pinocembrin, Osteoblast differentiation, BMP pathway, Estrogen receptor

Introduction

Bone mass is maintained by a balance between bone resorption by osteoclasts and bone formation by osteoblasts (Phan et al. 2004; Crockett et al. 2011). This biological mechanism is called “bone remodeling which is influenced by a number of factors, such as aging, hormonal conditions and lifestyle. Osteoporosis is a metabolic bone disease that has a higher risk of developing in women than in men (Tobias and Compston 1999). Postmenopausal women have reduced levels of the estrogen, a sex hormone that plays an important role in maintaining normal bone remodeling. Estrogen deficiency reduces bone mass due to increased bone resorption and increases the risk of fracture (Rodan and Martin 2000). Current treatments of osteoporosis include a bisphosphonate preparation having a bone resorption inhibitory effect and an estrogen preparation having a bone formation promoting and bone resorption suppressing effect are used. However, these drugs have side effects such as increased risk of breast cancer and endometriosis by estrogen preparations (Parente et al. 2008; Rossouw et al. 2002), and osteonecrosis of the jaw by bisphosphonate preparations (Zhao et al. 2016). Therefore, therapeutic strategies with minimal side effects are desired.

Osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stem cells, which can also differentiate into adipocytes and chondrocytes (Caplan 1991) and produce alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and bone matrix proteins such as type I collagen (COL1) and osteocalcin (Ocn), all factors in inducing osteoblastic mineralization. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are cytokines belonging to the transforming growth factor (TGF) β superfamily that regulated differentiation, proliferation and apoptosis (Katagiri et al. 2008). When bound to their receptor, BMPs regulate the expression of many target genes via Smad and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) which the signaling molecules (Miyazono et al. 2005; Canalis et al. 2003). Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) and Osterix are known to be essential transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation. Gene knockout mice for Runx2 and Osterix exhibit a marked inhibit in bone formation (Komori et al. 1997; Nakashima et al. 2002). BMPs were reported to activate these transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation (Marie 2008). Thus, BMPs have been developed as bone anabolic agents and approved for clinical use (Axelrad and Einhorn 2009). However, these agents have some inadequacies, including topical application and high costs (Garrett 2007). Therefore, small molecules that stimulate the production or signaling pathways of BMPs may be useful to resolve these problems.

For a long time, natural materials such as plants and microorganism and their components have been expected to have an effect of reducing the risk of developing diseases including osteoporosis and diabetes. Soy isoflavones (genistein, daidzein) contained in soybean have an estrogen-like effect, and it has been reported that these promote osteoblast differentiation (Pan et al. 2005; Yamaguchi and Sugimoto 2000) and suppress osteoclast differentiation (Rassi et al. 2002; Gao and Yamaguchi 1999). In addition, genistein and daidzein have also been shown to increase bone mass in osteoporosis model mice by promoting bone formation and suppressing bone resorption (Yamaguchi 2002). We searched for functional materials and bioactive compounds that could be useful in the prevention and treatment of bone metabolic disorders.

We focused on Alpinia zerumbet, which is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions and is known as a traditional plant in Okinawa, JAPNA (Zoghbi et al. 1999; Matsubara et al. 1994). Leaves, seeds, roots and fruits of A. zerumbet has been used as a folk medicine, because they have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. In addition, A. zerumbet contains 5,6-dehydrokawain and dihydro-5,6-dehydrokawain which promotes osteoblast differentiation (Kumagai et al. 2016), and cardamonin which suppresses osteoclast differentiation (Sung et al. 2013). Pinocembrin has been reported to have antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective (Rasul et al. 2013). In addition, pinocembrin has also been reported to exhibit estrogen-like effects (Zhao et al. 2008). However, the effect of pinocembrin on bone metabolism has not been reported yet. Therefore, we examined the effect of pinocembrin isolated from leaves of A. zerumbet on osteoblast differentiation.

Materials and methods

Reagents

Pinocembrin (molecular weight; 256.25, pKa; 7.27) was isolated and purified from the leaves of A. zerumbet from Okinawa, Japan in our laboratory. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR data of purified pinocembrin were consistent with those reported elsewhere (Tanjung et al. 2013). The purity (> 95%) of pinocembrin was determined by HPLC. Pinocembrin was dissolved in DMSO and stocked in freezer. Recombinant human noggin (BMP antagonist), LDN-193189 (BMP receptor I inhibitor), SB203580 (p38 MAPK inhibitor), PD98059 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor), SP600125 (c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) inhibitor), ICI 182,780 (Estrogen receptor (ER) antagonist) and Alizarin red S were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and phosphatase substrate were purchased from SIGMA-ALDRICH, Co. (St. Louis, MO). α-MEM was purchased Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other reagents were obtained from SIGMA-ALDRICH, Co. or Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd.

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 cells, an osteoblastic cell line from mouse calvaria, were obtained from the RIKEN Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan). MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Cell viability and proliferation

In cell viability assay, MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a cell density of 5000 cells/well and cultured for 2 days. After reaching confluency, the cells were further incubated with or without pinocembrin for 6 days. The cell viability was determined using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (DOJINDO, Kumamoto, Japan). The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader. In cell proliferation assay, MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a cell density of 2000 cells/well and cultured for 1 days. After a day, the cells were further incubated with or without pinocembrin for 2 days. The cell number was determined using a MTT reagent as an indicator of living cells. The absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Osteoblast differentiation

MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a cell density of 5000 cells/well and cultured for 2 days. After, reaching confluency, the cells were further incubated with or without pinocembrin for 6 days and fixed with ice-cold methanol. The fixed cells were incubated in ALP substrate buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH8.5, 2 mM MgCl2, 7.3 mM 4-nitrophenyl phosphate) at room temperature. The absorbance at 405 nm was measured as the ALP activity using a microplate reader. MC3T3-E1 cells were incubated with or without pinocembrin in osteogenic medium containing 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate for 9 to 12 days and fixed with ice-cold methanol. Mineralization of the extracellular matrix was determined by Alizarin red S staining which stain calcium. After cell fixation, 1% Alizarin red S solution was added and incubated at room temperature. Then, the cells were washed, dried and photographed.

Real time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

MC3T3-E1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a cell density of 1.5 × 105 cells/well and cultured for 2 days. The cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin for 6 h to 5 days. Total RNA was isolated using RNeasy Plus Mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). RNA concentration was determined using Nano Drop ND-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA was synthesized using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT kit (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (Rox) (Roche Diagnostics K. K., Mannheim, Germany) in an ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). The relative expression levels of the target genes to the expression level of the endogenous reference gene (β-actin) were calculated using the delta cycle threshold (Ct) method. The primer sequences are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer sequences of RT-PCR

| Target gene | Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) |

|---|---|---|

| Alkaline phosphate (Alp) | AACCACGCCACACCCAGTGC | GCCGCCACCCATGATCACGT |

| Osteocalcin (Ocn) | GGTAGTGAACAGACTCCGGC | CAAGCAGGGTTAAGCTCACA |

| Runx2 | CCGCACGACAACCGCACCAT | CGCTCCGGCCCACAAATCTC |

| Osterix | CCCACCCTTCCCTCACTCAT | CCTTGTACCACGAGCCATAGG |

| DIx5 | CTGGCCGCTTTACAGAGAAG | GGTGACTGTGGCGAGTTACA |

| Msx2 | AACACAAGACCAACCGGAAG | GCAGCCATTTTCAGCTTTTC |

| Bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp)-2 | GCTCCACAAACGAGAAAAGC | AGCAAGGGGAAAAGGACACT |

| Id1 | ATGGACTCCAGCCCTTCAG | AACACGCGGGGTTGATTA |

| β-actin | GGCTGTATTCCCCTCCATCG | CCAGTTGGTAACAATGCCATGT |

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were compared by using Dunnett’s t test. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance (Fig. 1).

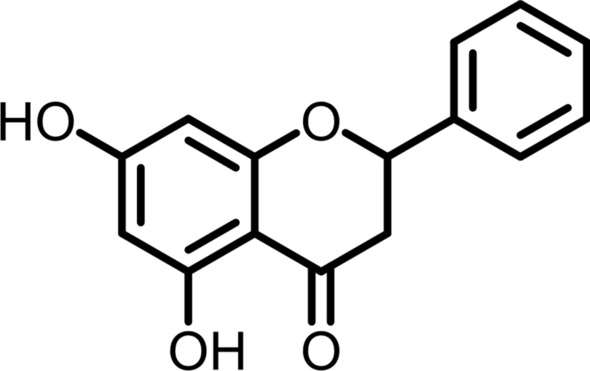

Fig. 1.

Structure of pinocembrin

Results

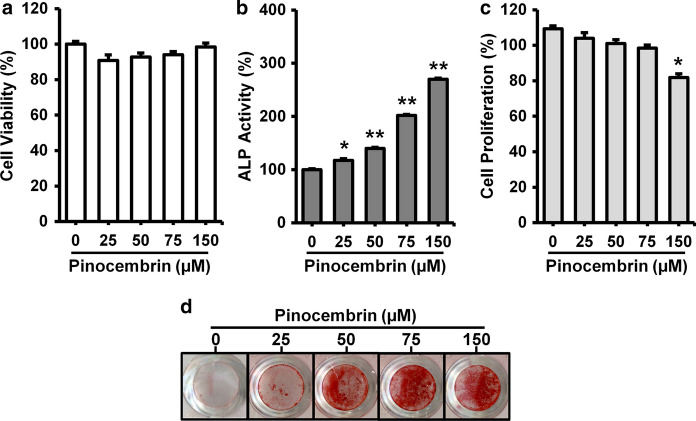

The effect of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells

To evaluate the effects of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation, we measured ALP activity as an early stage osteoblast maker in MC3T3-E1 cell. Without affecting cell viability, pinocembrin enhanced the ALP activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2a, b). In addition, to confirm that the pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity is independent on cell number, we measured the effect of pinocembrin on cell proliferation rate. Pinocembrin slightly inhibited cell proliferation at concentration of 150 µM but not increased (Fig. 2c). Next, the effect of pinocembrin on mineralization of MC3T3-E1 cells was confirmed as a late stage osteoblast maker using calcium staining Alizarin Red. The result showed that calcified area stained red was increased by the treatment of pinocembrin in a concentration-dependent manner, and indicated pinocembrin promoted osteoblastic mineralization (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

Effects of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. a, b MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin for 6 days. The cell viability was determined using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (a). Then, the cells were fixed and the ALP activity was measured (b). c MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin for 2 days. The cell viability was determined using a MTT assay. d MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin in osteogenic medium containing 50 µg/ml ascorbic acid and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate for 9 to 12 days. Osteoblastic mineralization was determined by Alizarin red S staining. The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the control (0 µM)

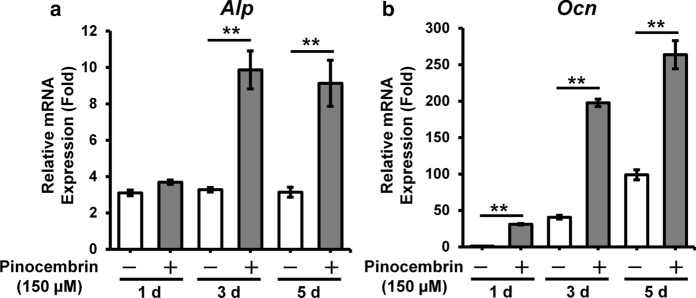

Effects of pinocembrin on mRNA expression of osteoblast differentiation marker genes

Next, to confirm the influence of pinocembrin on the expression of osteoblast differentiation marker genes, we performed real-time RT-PCR analysis. Pinocembrin significantly increased Alp and Ocn mRNA expression compared to the cells cultured without pinocembrin (Fig. 3a, b). Expression of Alp and Ocn mRNA markedly increased from 3 days after pinocembrin treatment.

Fig. 3.

Effects of pinocembrin on mRNA expression of osteoblast differentiation marker in MC3T3–E1 cells. a, b MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin (150 µM) for the indicated numbers of days after the cells reached confluency. The relative mRNA expressions of Alp (a) and Ocn (b) were determined by real-time RT-PCR. The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the cells cultured without pinocembrin

Effects of pinocembrin on mRNA expression of osteoblast differentiation essential transcription factor.

We confirmed the influence on mRNA expression of Runx2 and Osterix which are essential transcription factors for osteoblast differentiation. The expression of Runx2 and Osterix mRNA peaked at 12 h after pinocembrin treatment (Fig. 4a, b). Furthermore, mRNA expression of distal-less homeobox 5 (Dlx5) and Msh homeobox 2 (Msx2), which are enhancers of these transcription factors was also confirmed. The expression of Dlx5 and Msx2 mRNA peaked at 12 h after pinocembrin treatment, and then became equivalent to the cells cultured without pinocembrin (Fig. 4c, d).

Fig. 4.

Effects of pinocembrin on mRNA expression of osteoblast differentiation-related transcription factors in MC3T3-E1 cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin (150 µM) for the indicated numbers of days after the cells reached confluency. The relative mRNA expressions of Runx2, Osterix, Dlx5 and Msx2 were determined by real-time RT-PCR (a–d). The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the cells cultured without pinocembrin

Involvement of BMP signaling pathways in the effects of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation.

To clarify the participation of BMP signaling pathways in the effects of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation, we analyzed using its specific inhibitors. Both BMP antagonist (noggin) and BMPR I kinase inhibitor (LDN-193189) almost completely invalidated the pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity (Fig. 5a). The p38 MAPK signaling inhibitor (SB203580) partly and dose-dependently decreased the pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity (Fig. 5b). In contact, the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling inhibitor (PD98059) further enhanced pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, the JNK signaling inhibitor (SP600125) had no effect on pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity (Fig. 5c). These data suggest that BMP is involved in the effect of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation.

Fig. 5.

Effects of pinocembrin on BMP-2 related signaling pathways. a, b MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with the specific inhibitors [noggin (Nog; 7.5, 15 ng/ml), LDN-193189 (LDN; 7.5, 15 nM), SB203580 (SB; 5, 10 µM), PD98059 (PD; 5, 10 µM), SP600125 (SP; 5, 10 µM)] in the presence pinocembrin (150 µM) for 6 days. After the culture, the cells were fixed and the ALP activity was measured. The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the cells cultured without pinocembrin. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. the pinocembrin-treated cells without an inhibitor. c, d MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with or without pinocembrin (150 µM) for the indicated numbers of days after the cells reached confluency. The relative mRNA expressions of Bmp-2 and Id1 were determined by real-time RT-PCR. The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the cells cultured without pinocembrin

Therefore, we next examined the effect of pinocembrin on Bmp-2 expression in the mRNA level. The expression of Bmp-2 mRNA peaked at 12 h after pinocembrin treatment, and then became equivalent to the cells untreated (Fig. 5c). Additionally, pinocembrin also increased the mRNA expression of inhibitor of DNA-binding 1 (Id1), which is a target gene of BMP-2, as well as Bmp-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 5d). These results indicated pinocembrin induced BMP-2 expression and activate BMP signaling pathway.

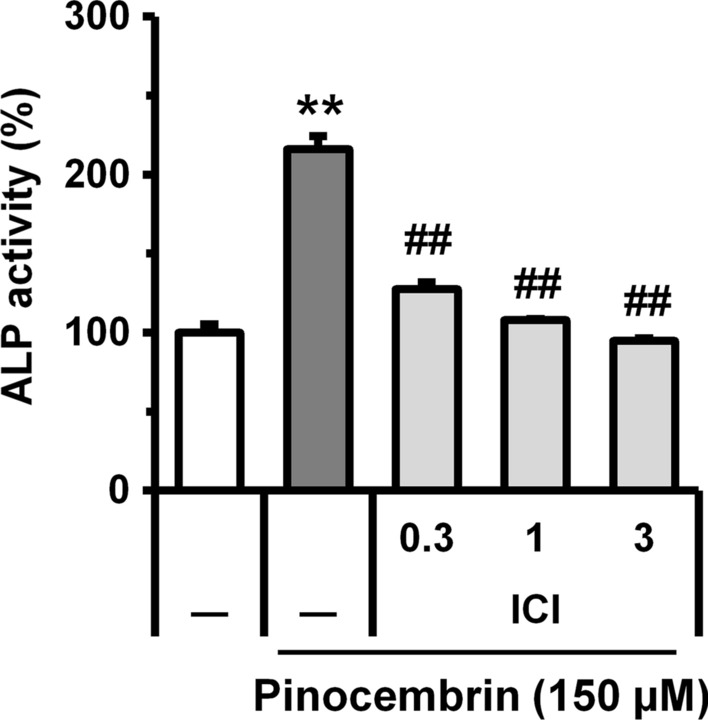

Involvement of estrogen receptor on pinocembrin-induced osteoblast differentiation

We examined whether or not ER is related to the effect of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation using ER antagonist. As a result, the estrogen receptor antagonist (ICI182780) completely abolished the increase of ALP activity-induced by the treatment of pinocembrin (Fig. 6). This suggests that pinocembrin induces osteoblast differentiation via ER dependent signal transduction.

Fig. 6.

Action of estrogen receptor inhibitor on pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity in MC3T3-E1 cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured with the estrogen receptor inhibitor [ICI 182,780 (ICI; 0.3, 1, 3 µM)] in the presence pinocembrin (150 µM) for 6 days. After the culture, the cells were fixed and the ALP activity was measured. The data represent the means ± SD of three independent experiment. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the cells cultured without pinocembrin. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 vs. the pinocembrin-treated cells without an inhibitor

Discussion

Natural products and their components are expected to be applied as supplements and medicines for the prevention and treatment of various diseases. Pinocembrin, isolated from A. zerumbet, is a natural flavonoid compound that is also found in honey, propolis and ginger plants (Massaro et al. 2014; Lan et al. 2016) containing various pharmacological effects such as antibacterial (Veloz et al. 2019), anti-inflammatory (Saad et al. 2015), anti-allergy (Hanieh et al. 2017) and anti-cancer (Aryappalli et al. 2019) properties. In this study, we evaluated the effect of pinocembrin on osteoblast differentiation.

Pinocembrin isolated from leaves of A. zerumbet promoted ALP activity and mineralization in MC3T3-E1 cells, and also increased mRNA expression of Alp and Ocn. These results suggest that pinocembrin promotes both early and late osteoblast differentiation in MC3T3-E1 cells. The BMP signaling pathway plays an important role in osteoblast differentiation whose pathway is also reported to be induced by hesperetin, daidzein and genistein (Trzeciakiewicz et al. 2010; Jia et al. 2003; Dai et al. 2013). BMPs have been reported to bind type I serine/threonine kinase receptor and induce osteoblast differentiation through Smad-dependent pathways and Smad-independent pathways including p38, ERK and JNK MAPK pathways (Miyazono et al. 2005; Higuchi et al. 2002). We showed that Noggin, which blocks its receptor binding of BMPs, and LDN-193189, which blocks BMP receptor kinase, completely abolished pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity. Furthermore, pinocembrin increased BMP-2 mRNA expression in MC3T3-E1 cells. Activated BMP receptors phosphorylate Smad1/5/8, the key transcriptional factor of BMP signaling, and then Smad1/5/8 bind to BMP response elements in target genes such as Id1 (Miyazono et al. 2005). Because pinocembrin increased Id1 mRNA expression in MC3T3-E1 cells, pinocembrin may induce the Smad-dependent BMP signaling pathway. We also investigated the involvement of p38, ERK, and JNK MAPK, which are related to Smad-independent pathways, in pinocembrin-induced osteoblast differentiation. p38 MAPK inhibitor almost suppressed the pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity while ERK inhibitors further enhanced pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity. MC3T3-E1 cells and BMP-2 treated C2C12 cells have been reported to promote differentiation and mineralization by ERK inhibitors (Higuchi et al. 2002), which is consistent with our results. In contrast, JNK inhibitors did not affect pinocembrin-promoted ALP activity. These results suggest that pinocembrin stimulates osteoblast differentiation through Smad-dependent pathway and Smad-independent p38 MAPK pathway associated with BMP-2 induction.

Runx2 and Osterix are known as essential transcription factors in osteoblast differentiation. It has been reported that BMP-2 induces osteoblast differentiation by activating Runx2 and Osterix existing downstream of the BMP signaling pathway (Marie 2008). Osterix exists downstream of Runx2, and Osterix activation is said to depend on Runx2 (Nakashima et al. 2002). Pinocembrin increased Runx2 and Osterix mRNA expression, suggesting that it induces activation of these transcription factors via the BMP signaling pathway. Runx2 is activated by Dlx5, a homeobox transcription factor that acts as an enhancer of Runx2. In addition, it has been reported that p38 MAPK, which is a Smad-dependent pathway and a Smad-independent pathway, plays an important role in Dlx5 activation (Kawane et al. 2014; Rahman et al. 2015). BMP-2 treated Runx2 knockout mice show increased expression of Osterix, but this Osterix expression is abolished by knocking down the transcription factor Msx2, deeply involved in the increased expression of Runx2-independent Osterix (Lee et al. 2003). Expression of Msx2 has been reported to be increased by BMP-2 (Liu et al. 2007). Osterix has also been reported to be activated by Runx2 enhancer Dlx5 (Lee et al. 2003). Pinocembrin increased Dlx5 and Msx2 mRNA expression in MC3T3-E1 cells, which may induce Runx2 and Msx2-dependent osteoblast differentiation through the BMP signaling pathway.

The sex hormone estrogen plays an important role in controlling bone remodeling (Turner et al. 1994). It has been reported that 17β-estradiol (E2), a type of estrogen, forms a complex with the estrogen receptor, binds directly to the estrogen response element (ERE), and activates transcription of the BMP-2 genes (Mathieu and Merregaert 1994; Zhou et al. 2003). Loss of binding between ER and ERE has also been reported to reduce expression of Col1, ALP and OC in osteoblasts (Rudnik et al. 2008). These reports indicate that ER-ERE binding is important for bone morphogenetic gene expression and osteoblast differentiation. Because pinocembrin has been reported to exhibit an estrogen-like action, we confirmed whether ER is involved in the osteoblast differentiation-inducing action of pinocembrin. Estrogen receptor inhibitors completely abolished pinocembrin-stimulated ALP activity. This result suggests that the ER activity by pinocembrin may contribute to the increase of BMP-2 mRNA expression.

The MAPKs and transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) plays an important role not only in inflammatory responses but also in osteoclast differentiation (Asagiri and Takayanagi 2007). Pinocembrin has been reported to suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses accompanying the inhibition of MAPKs and NF-κB signaling pathway in mouse monocytic RAW264.7 cells (Soromou et al. 2012). Therefore, pinocembrin is expected to have a bone anabolic effect as well as suppression of osteoclast differentiation and bone loss.

Because pinocembrin has severely limited applications due to its low water solubility, some studies have been conducted to improve water solubility and stability of pinocembrin by introducing inclusion complexes with cyclodextrin and lecithin (Zhou et al. 2014; Yang et al. 2018). These reports may further facilitate clinical application studies of pinocembrin.

In this study, we found that pinocembrin isolated from A. zerumbet promotes osteoblast differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells. Pinocembrin may increase BMP-2 expression via ER which then promotes osteoblast specific genes expression and mineralization through both Smad-dependent and independent pathway following Runx2 and Osterix induction. Thus, pinocembrin is highly anticipated as an anabolic drug candidate for the prevention and treatment of bone metabolic diseases such as osteoporosis.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Takayuki Yonezawa and Toshiaki Teruya contributed equally to this work.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Aryappalli P, Shabbiri K, Masad RJ, Al-Marri RH, Haneefa SM, et al. Inhibition of tyrosine-phosphorylated STAT3 in human breast and lung cancer cells by manuka honey is mediated by selective antagonism of the IL-6 receptor. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:4340. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asagiri M, Takayanagi H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone. 2007;40:251–264. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrad TW, Einhorn TA. Bone morphogenetic proteins in orthopaedic surgery. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009;20:481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canalis E, Economides AN, Gazzerro E. Bone morphogenetic proteins, their antagonists, and the skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:218–235. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells. J Orthop Res. 1991;9:641–650. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100090504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett JC, Rogers MJ, Coxon FP, Hocking LJ, Helfrich MH. Bone remodelling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:991–998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.063032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J, Li Y, Zhou H, Chen J, Chen M, Xiao Z. Genistein promotion of osteogenic differentiation through BMP2/SMAD5/RUNX2 signaling. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9:1089–1098. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao YH, Yamaguchi M. Suppressive effect of genistein on rat bone osteoclasts: apoptosis is induced through Ca2+ signaling. Biol Pharm Bull. 1999;22:805–809. doi: 10.1248/bpb.22.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett IR. Anabolic agents and the bone morphogenetic protein pathway. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;78:127–171. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)78004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanieh H, Hairul Islam VI, Saravanan S, Chellappandian M, Ragul K, et al. Pinocembrin, a novel histidine decarboxylase inhibitor with anti-allergic potential in in vitro. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017;814:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi C, Myoui A, Hashimoto N, Kuriyama K, Yoshioka K, et al. Continuous inhibition of MAPK signaling promotes the early osteoblastic differentiation and mineralization of the extracellular matrix. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1785–1794. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia TL, Wang HZ, Xie LP, Wang XY, Zhang RQ. Daidzein enhances osteoblast growth that may be mediated by increased bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) production. Biochem Pharmacol. 2003;65:709–715. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(02)01585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katagiri T, Suda T, Miyazono K. The bone morphogenetic proteins. In: Derynck R, Miyazono K, editors. The TGF-b family. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2008. pp. 121–149. [Google Scholar]

- Kawane T, Komori H, Liu W, Moriishi T, Miyazaki T, et al. Dlx5 and mef2 regulate a novel runx2 enhancer for osteoblast-specific expression. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:1960–1969. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komori T, et al. Targeted disruption of Cbfa1 results in a complete lack of bone formation owing to maturational arrest of osteoblasts. Cell. 1997;89:755–764. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80258-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai M, Mishima T, Watanabe A, Harada T, Yoshida I, et al. 5,6-Dehydrokawain from Alpinia zerumbet promotes osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cell differentiation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2016;80:1425–1432. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2016.1153959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X, Wang W, Li Q, Wang J. The natural flavonoid pinocembrin: molecular targets and potential therapeutic applications. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:1794–1801. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MH, Kwon TG, Park HS, Wozney JM, Ryoo HM. BMP-2-induced Osterix expression is mediated by Dlx5 but is independent of Runx2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;309:689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Gao Y, Sakamoto K, Minamizato T, Furukawa K, et al. BMP-2 promotes differentiation of osteoblasts and chondroblasts in Runx2-deficient cell lines. J Cell Physiol. 2007;211:728–735. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie PJ. Transcription factors controlling osteoblastogenesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;473:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massaro CF, Katouli M, Grkovic T, Vu H, Quinn RJ, et al. Anti-staphylococcal activity of C-methyl flavanones from propolis of Australian stingless bees (Tetragonula carbonaria) and fruit resins of Corymbia torelliana (Myrtaceae) Fitoterapia. 2014;95:247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu E, Merregaert J. Characterization of the stromal osteogenic cell line MN7: mRNA steady-state level of selected osteogenic markers depends on cell density and is influenced by 17β-estradiol. J Bone Miner Res. 1994;9:183–192. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650090207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara Y, Morita M, Katsui A, Sawabe A. Constituents of essential oil in the leaf and flower of Getto (Alpinia speciosa K. Schum.) J Jpn Oil Chem Soc. 1994;43:424–427. doi: 10.5650/jos1956.43.424. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K, Maeda S, Imamura T. BMP receptor signaling: transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Zhou X, Kunkel G, Zhang Z, Deng JM, et al. The novel zinc finger-containing transcription factor osterix is required for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Cell. 2002;108:17–29. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W, Quarles LD, Song LH, Yu YH, Jiao C, et al. Genistein stimulates the osteoblastic differentiation via NO/cGMP in bone marrow culture. J Cell Biochem. 2005;94:307–316. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parente L, Uyehara C, Larsen W, Whitcomb B, Farley J. Long-term impact of the women's health initiative on HRT. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;277:219–224. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan TC, Xu J, Zheng MH. Interaction between osteoblast and osteoclast: impact in bone disease. Histol Histopathol. 2004;19:1325–1344. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MS, Akhtar N, Jamil HM, Banik RS, Asaduzzaman SM. TGF-β/BMP signaling and other molecular events: regulation of osteoblastogenesis and bone formation. Bone Res. 2015;3:15005. doi: 10.1038/boneres.2015.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi CM, Lieberherr M, Chaumaz G, Pointillart A, Cournot G. Down-regulation of osteoclast differentiation by daidzein via caspase 3. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:630–638. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.4.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasul A, Millimouno FM, Ali Eltayb W, Ali M, Li J, Li X. Pinocembrin: a novel natural compound with versatile pharmacological and biological activities. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2013/379850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodan GA, Martin TJ. Therapeutic approaches to bone diseases. Science. 2000;289:1508–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossouw JE, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women's Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudnik V, Sanyal A, Syed FA, Monroe DG, Spelsberg TC, Oursler MJ, Khosla S. Loss of ERE binding activity by estrogen receptor-α alters basal and estrogen-stimulated bone-related gene expression by osteoblastic cells. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103:896–907. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad MA, Abdel Salam RM, Kenawy SA, Attia AS. Pinocembrin attenuates hippocampal inflammation, oxidative perturbations and apoptosis in a rat model of global cerebral ischemia reperfusion. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soromou LW, Chu X, Jiang L, Wei M, Huo M, Chen N, Guan S, Yang X, Chen C, Feng H, Deng X. In vitro and in vivo protection provided by pinocembrin against lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2012;14:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung B, Prasad S, Yadav VR, Gupta SC, Reuter S, et al. RANKL signaling and osteoclastogenesis is negatively regulated by cardamonin. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e64118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanjung M, Tjahjandarie TS, Sentosa MH. Antioxidant and cytotoxic agent from the rhizomes of Kaempferia pandurate. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2013;3:401–404. doi: 10.1016/s2222-1808(13)60091-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias JH, Compston JE. Does estrogen stimulate osteoblast function in postmenopausal women? Bone. 1999;24:121–124. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trzeciakiewicz A, Habauzit V, Mercier S, Lebecque P, Davicco MJ, et al. Hesperetin stimulates differentiation of primary rat osteoblasts involving the BMP signalling pathway. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RT, Riggs BL, Spelsberg TC. Skeletal effects of estrogen. Endocr Rev. 1994;15:275–300. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloz JJ, Alvear M, Salazar LA. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm activity against Streptococcus mutans of individual and mixtures of the main polyphenolic compounds found in Chilean propolis. Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2019/7602343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M. Isoflavone and bone metabolism: its cellular mechanism and preventive role in bone loss. J Health Sci. 2002;48:209–222. doi: 10.1248/jhs.48.209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi M, Sugimoto E. Stimulatory effect of genistein and daidzein on protein synthesis in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells: activation of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;214:97–102. doi: 10.1023/a:1007199120295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Wang X, Chen XY, Ji HY, Zhang Y, Liu AJ. Pinocembrin-lecithin complex: characterization, solubilization, and antioxidant activities. Biomolecules. 2018;8:41. doi: 10.3390/biom8020041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Dasmahapatra AK, Khan SI, Khan IA. Anti-aromatase activity of the constituents from damiana (Turnera diffusa) J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;120:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao TT, Zhong Z, Xiao SF. Review of bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2016;30:589–592. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1781.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Turgeman G, Harris SE, Leitman DC, Komm BS, Bodine PV, Gazit D. Estrogens activate bone morphogenetic protein-2 gene transcription in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:56–66. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SY, Ma SX, Cheng HL, Yang LJ, Chen W, Yin YQ, Shi YM. Host–guest interaction between pinocembrin and cyclodextrins: Characterization, solubilization and stability. J Mol Struct. 2014;1058:181–188. doi: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2013.11.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zoghbi MGB, Andrade EHA, Maia JGS. Volatile constituents from leaves and flowers of Alpinia speciosa K. Schum. and A. purpurata (Viell.) Schum. Flavour Fragr J. 1999;14:411–414. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1026(199911/12)14:6<411::AID-FFJ854>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [Google Scholar]