Type I interferons (IFNs) are secretory cytokines with protective roles against viral infection. Most studies have focused on the signaling pathways that regulate the transcriptional activation of type I IFNs; however, little is known about the secretory mechanism of these cytokines, except for information obtained from a few studies reporting the secretion polarity of IFNβ in epithelial cells.1–4 Here, we investigate the role of Rab1, a small GTPase of the Rab family, in IFNβ secretion. We show that Rab1 inactivation blocked the secretion of IFNβ from human embryonic kidney 293T (HEK293T) cells transfected with IFNβ-inducing molecules (TRIF, MAVS, and TBK1) but not from cells stimulated with RNA ligands (Sendai virus (SeV) or polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C)). Despite the differential effects of Rab1 inactivation and regardless of the triggering stimuli, IFNβ secretion was inhibited by brefeldin A (BFA), a fungal metabolite that inhibits ER-to-Golgi transport. In addition, a proportion of endogenous 3×Flag-tagged IFNβ colocalized with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 within SeV-infected cells. Our results indicate that IFNβ secretion generally requires the conventional ER-Golgi pathway while showing differential responses to Rab1 inactivation in cells exposed to distinct innate immune stimuli.

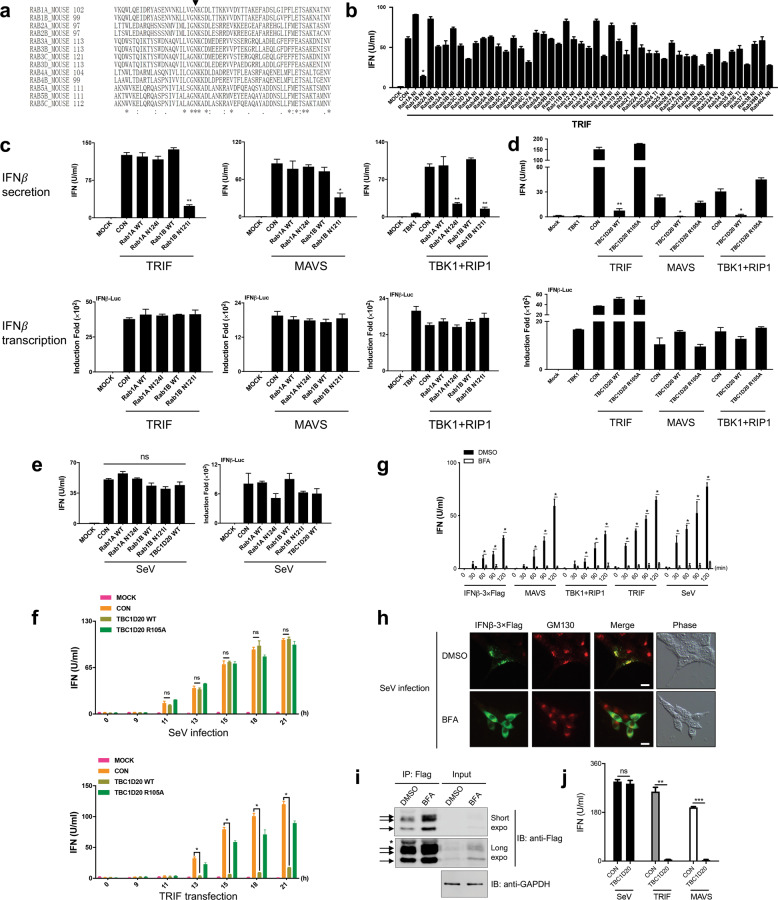

Rab family members are small GTPases belonging to the Ras superfamily that act as central regulators of membrane trafficking in all eukaryotic cells.5,6 GTP-binding-defective Rab mutants exert a dominant inhibitory effect on the function of endogenous Rab proteins.7,8 To determine which Rab proteins might play a role in IFNβ secretion, we cotransfected Rab mutants (Fig. 1a, b, primers in Table S1) individually with TRIF (a strong activator of type I IFNs in the TLR3 pathway) into HEK293T cells. Among all the Rab mutants tested, Rab1B (N121I) had the strongest inhibitory effect on the release of IFNβ into the culture medium of TRIF-expressing cells (Fig. 1b), indicating that Rab1B might be a key regulator of IFNβ secretion. As crucial regulators of ER-Golgi and intra-Golgi transport in mammalian cells,8,9 the two Rab1 isoforms Rab1A and Rab1B share 92% amino acid identity and are thought to be functionally redundant. We found that Rab1B (N121I), but not Rab1A (N124I), blocked IFNβ secretion induced by TRIF or MAVS (a strong activator of type I IFNs in the RIG-I/MDA5 pathway) (Fig. 1c, upper panel), indicating that Rab1B plays a more dominant role than Rab1A in IFNβ secretion under these conditions. The inhibitory effect of Rab1B (N121I) on IFNβ secretion was not due to a defect in IFNβ transcription, as shown by IFNβ reporter assays (Fig. 1c, lower panel).

Fig. 1.

IFNβ secretion requires the conventional ER-Golgi pathway while showing differential susceptibility to Rab1 inactivation in HEK293T cells upon exposure to distinct innate immune stimuli. a Asn121 of Rab1B is one of the most conserved amino acids in Rab proteins. Sequence alignment of the nucleotide-binding region containing the highly conserved asparagine (N, black triangle) of several murine Rab proteins. Mutation of the conserved Asn generates a GTP-binding-defective Rab mutant. b Rab1B (N121I) strongly blocks IFNβ secretion in TRIF-expressing cells. Type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium of HEK293T cells cotransfected with 50 ng of TRIF and 150 ng of the indicated Rab mutants were performed at 24 h post transfection. c Rab1B is required for the IFNβ secretion induced by TRIF and MAVS, while both Rab1A and Rab1B are required for the IFNβ secretion induced by TBK1 plus RIP1. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 50 ng of IFNβ-Luc, 100 ng of TRIF, MAVS, TBK1 or TBK1 plus RIP1, and 100 ng of the indicated Rab1 plasmids for 24 h. Type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium (upper panel) and luciferase activity assays (lower panel) were performed. d Rab1 inactivation by TBC1D20 impairs IFNβ secretion induced by signaling molecules. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 50 ng of IFNβ-Luc, 100 ng of TBK1, TBK1 plus RIP1, MAVS, TRIF, and 100 ng of the indicated TBC1D20 plasmids for 24 h. Type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium (upper panel) and luciferase activity assays (lower panel) were performed. e SeV-induced IFNβ secretion is resistant to Rab1 inactivation. HEK293T cells were cotransfected with 50 ng of IFNβ-Luc and 100 ng of the indicated plasmids for 6 h and then infected with SeV for 18 h. Type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium (left panel) and luciferase activity assays (right panel) were assessed. f SeV-induced IFNβ secretion is resistant to Rab1 inactivation by TBC1D20 at different time points. HEK293T cells were transfected with 2 μg of the indicated plasmids and infected with SeV (upper panel) or cotransfected with 2 μg of TRIF (lower panel). At the indicated time points, type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium were performed. g BFA strongly blocks IFNβ secretion under all conditions. HEK293T cells were transfected with 150 ng of the indicated plasmids or infected with SeV for 18 h and then treated with DMSO (black, control) or BFA (white, 2.0 μg/ml) in fresh culture medium. Type I IFN bioassays of the supernatants of the cells at the indicated time points posttreatment were assessed. h, i BFA treatment caused a dispersed distribution and accumulation of IFNβ-3×Flag in the cytoplasm of knock-in cells infected with SeV. The 293T-IFNβ-3×Flag-KI-3# cells were infected with SeV for 14 h and then treated with DMSO (control) or BFA (2.0 μg/ml) for 1 h. The cells were fixed, labeled with the indicated antibodies (anti-Flag and anti-GM130), and imaged with a fluorescence microscopy (h). All images are representative of at least three independent experiments. Scale bars represent 10 μm. 293T-IFNβ-3×Flag-KI-3# cells were infected with SeV for 23 h and then treated with DMSO or BFA (2.0 μg/ml) for 1 h. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-Flag beads, followed by immunoblotting (IB) (i). Blots were probed with mouse anti-Flag, and rabbit anti-GAPDH was the loading control. Arrows indicate the bands associated with IFNβ-3×Flag, and the asterisk indicates the antibody light chain. Short expo, short exposure time; long expo, long exposure time. j SeV-induced IFNβ-3×Flag secretion is resistant to Rab1 inactivation by TBC1D20 in the knock-in cells. 293T-IFNβ-3×Flag-KI-3# cells were transfected with 100 ng of the TBC1D20 plasmid and infected with SeV or cotransfected with 100 ng of TRIF or MAVS. After 20 h, type I IFN bioassays of the culture medium were performed. The data are representative of at least three experiments (mean ± SEM, unpaired t-test, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ns not significant). WT, wild type

TBK1 is a common kinase downstream of TRIF and MAVS. Unexpectedly, TBK1 strongly induced the expression but failed to trigger the secretion of IFNβ in HEK293T cells, whereas MAVS and RIG-I-N (the constitutive active form of RIG-I) induced both the expression and secretion of IFNβ in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S1a). Interestingly, we found that coexpression of RIP1 (a protein that functions in a variety of cellular pathways, including intracellular dsRNA-induced antiviral response10) and TBK1 was able to reverse defective IFNβ secretion (Fig. S1b). These results imply that the secretory process of IFNβ can be influenced by various innate immune stimuli. Indeed, IFNβ secretion induced by TBK1 and RIP1 was slightly different from that induced by TRIF or MAVS, as the former was dependent on both Rab1A and Rab1B (Fig. 1c).

TBC1 domain family member 20 (TBC1D20) (Fig. S2a), a GTPase-activating protein (GAP) that inactivates Rab1,11,12 can disrupt Golgi integrity through its GAP activity (Fig. S2b). TBC1D20, but not its catalytically inactive mutant TBC1D20 (R105A), strongly blocked the IFNβ secretion induced by TRIF, MAVS, or TBK1 plus RIP1 without altering the transcription of IFNβ (Fig. 1d). This result further demonstrates that normal Rab1 activity is required for IFNβ secretion induced by the expression of IFNβ-inducing molecules.

However, SeV-induced IFNβ secretion was unaffected by Rab1 mutants or TBC1D20 (Fig. 1e). Our time-course experiment also confirmed that TBC1D20 did not affect SeV-induced IFNβ secretion, although it significantly inhibited TRIF-induced IFNβ secretion at different time points (Fig. 1f). Similarly, IFNβ secretion upon transfection of poly(I:C), a synthetic mimic of dsRNA, was also unaffected by Rab1 inactivation (Fig. S3). These results prompted us to examine whether RNA ligand-induced IFNβ is secreted via the ER-Golgi pathway, in which Rab1 plays an important role. We found that IFNβ secretion triggered by the expression of various proteins or SeV infection was significantly inhibited by BFA, a well-known inhibitor of ER-Golgi transport13 (Fig. 1g), indicating that the ER-Golgi pathway is required for IFNβ secretion under all the circumstances investigated. To visualize endogenous IFNβ upon SeV infection, we generated a 3′-terminal 3×Flag-tagged IFNβ knock-in (IFNβ-3×Flag-KI) HEK293T cell line by CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig. S4 and Materials and Methods). IFNβ-3×Flag proteins induced by SeV infection displayed a punctate staining pattern resembling Golgi stacks, and a large portion of these puncta colocalized with the cis-Golgi marker GM130 (Fig. 1h, upper panel). BFA treatment caused a dispersed distribution of IFNβ-3×Flag throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 1h, lower panel) and an accumulation of intracellular IFNβ-3×Flag in SeV-infected IFNβ-knock-in cells (Fig. 1i). TBC1D20 was unable to inhibit IFNβ-3×Flag secretion in the knock-in cells infected with SeV, whereas it abolished the secretion induced by TRIF or MAVS (Fig. 1j). These data further demonstrated that IFNβ secretion upon SeV infection relies on the conventional ER-Golgi pathway but shows strong resistance to Rab1 inactivation. This seems to be a paradox given the established role of Rab1 in the ER-Golgi pathway, and we suggest two possible hypotheses: (1) viral infection might reactivate endogenous Rab1, which is not entirely inhibited by Rab1 mutants or TBC1D20, and/or (2) viral infection might switch on additional secretory components in the ER-Golgi pathway that compensate for the loss of Rab1 activity.

In summary, our findings expand the paradigm that the secretory mode of a specific cargo, such as IFNβ, is determined not only by the nature of the protein itself but also by additional factors, such as the gene expression pattern and the cell type.1–3,14 We illustrated that IFNβ is transported via the conventional ER-Golgi pathway in HEK293T cells and that this secretion process relies on different Rab1 isoforms and possibly other secretory components upon exposure to distinct innate immune stimuli (Fig. S5). These observations demonstrate that the molecular basis for the secretion process of type I IFNs is more complicated than initially presumed and will need further investigation in different cell types and animal models, which we believe will broaden our understanding of the antiviral immune responses and relevant disease control.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31830022 and 81621001) and the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2019YFA0508500). X.Z. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31800752). We thank Dr. Jianzhong Xi (Peking University) for hCas9 and gRNA expression vectors; Dr. Mitsunori Fukuda (Tohoku University) for mouse Rab expression vectors; Dr. Hongbing Shu (Wuhan University) for the human MAVS expression vector; Dr. Jianguo Chen (Peking University) for the peYFP-Golgi expression vector; Dr. Congyi Zheng (Wuhan University) for SeV; and Drs. Yulong Li and Jianli Tao (Peking University) for critical discussions.

Author contributions

J.Y. and Z.J. designed the research; J.Y. performed the majority of the experiments; X.Z., R.Z., H.S., and F.Y. assisted in some experiments, including the construct preparations; J.Y., X.Z., and Z.J. analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Jing Yang, Xiang Zhou

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41423-021-00659-y.

References

- 1.Okamoto S, et al. Stimulation side-dependent asymmetrical secretion of poly I:poly C-induced interferon-beta from polarized epithelial cell lines. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;254:5–9. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi K, et al. Secretion polarity of interferon-beta in epithelial cell lines. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;402:201–207. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maruyama M, et al. Subcellular trafficking of exogenously expressed interferon-beta in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2004;201:117–125. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakamura M, et al. Exogenous expression of interferon-beta in cultured brain microvessel endothelial cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:1441–1443. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stenmark H. Rab GTPases as coordinators of vesicle traffic. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:513–525. doi: 10.1038/nrm2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukuda M. Regulation of secretory vesicle traffic by Rab small GTPases. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:2801–2813. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8351-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hume AN, et al. Rab27a regulates the peripheral distribution of melanosomes in melanocytes. J. Cell Biol. 2001;152:795–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tisdale EJ, et al. GTP-binding mutants of rab1 and rab2 are potent inhibitors of vesicular transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the Golgi complex. J. Cell Biol. 1992;119:749–761. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plutner H, et al. Rab1b regulates vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and successive Golgi compartments. J. Cell Biol. 1991;115:31–43. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balachandran S, Thomas E, Barber GN. A FADD-dependent innate immune mechanism in mammalian cells. Nature. 2004;432:401–405. doi: 10.1038/nature03124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas AK, et al. Analysis of GTPase-activating proteins: Rab1 and Rab43 are key Rabs required to maintain a functional Golgi complex in human cells. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:2997–3010. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sklan EH, et al. TBC1D20 is a Rab1 GTPase-activating protein that mediates hepatitis C virus replication. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:36354–36361. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nickel W, Rabouille C. Mechanisms of regulated unconventional protein secretion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:148–155. doi: 10.1038/nrm2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishio T, et al. Secretion mode and subcellular localization of human interferon-beta exogenously expressed in porcine renal epithelial LLC-PK1 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:1653–1655. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.