Highlights

-

•

There have been many developments in national physical activity policy in England that are targeted to children and young people.

-

•

The area of most significant progress is national physical activity guidelines.

-

•

Physical activity targets have focussed on provision rather than behaviour.

-

•

Surveillance of physical activity has been plentiful but infrequent over time.

-

•

There has been a sustained public-education campaign but limited evaluation of its effectiveness.

Keywords: Physical activity, Policy, Public education, Recommendations, Surveillance

Abstract

Background

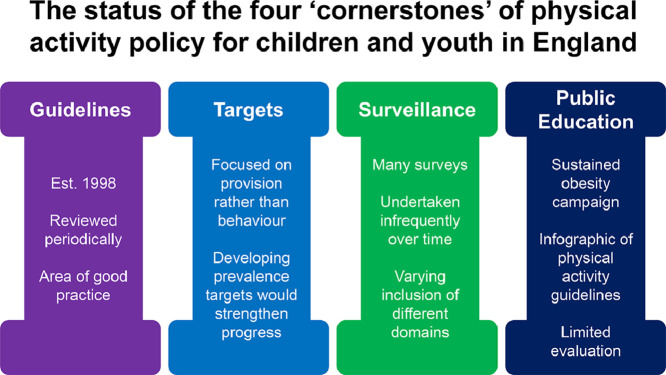

There has been an increasing focus on the importance of national policy to address population levels of physical inactivity. It has been suggested that the 4 cornerstones of policy comprise (1) national guidelines on physical activity (PA), (2) setting population goals and targets, (3) surveillance or health-monitoring systems, and (4) public education. The current study aimed to review the policy actions that have addressed each of these elements for children and youth in England and to identify areas of progress and remaining challenges.

Methods

A literature search was undertaken to identify past and present documents relevant to PA policy for children and youth in England. Each document was analyzed to identify content relevant to the 4 cornerstones of policy.

Results

Physical activity guidelines (Cornerstone 1) for children and youth have been in place since 1998 and reviewed periodically. Physical activity targets (Cornerstone 2) have focussed on the provision of opportunities for PA, mainly through physical education in schools rather than in relation to the proportion of children meeting recommended PA levels. There has been much surveillance (Cornerstone 3) of children's PA, but this has been undertaken infrequently over time and with varying inclusions of differing domains of activity. There has been only 1 campaign (Cornerstone 4) that targeted children and their intermediaries, Change4Life, which was an obesity campaign focussing on dietary behavior in combination with PA. Most recently, a government infographic supporting the PA guidelines for children and young people was developed, but details of its dissemination and usage are unknown.

Conclusion

There have been many developments in national PA policy in England targeted to children and young people. The area of most significant progress is national PA guidelines. Establishing prevalence targets, streamlining surveillance systems, and investing in public education with supportive policies, environments, and opportunities would strengthen national policy efforts to increase PA and reduce sedentary behavior.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

The health benefits of a physically active lifestyle for children and young people are well documented, with many international and large-scale reviews demonstrating the direct health benefits of physical activity (PA) on children's physical, psychosocial, and intellectual development.1 Current evidence suggests that many of these benefits are likely to track or carry forward into adulthood,2, 3, 4 which has important implications for health-promotion efforts, given that PA declines with age from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood.5,6

Despite the substantial and varied benefits of PA, the majority of children worldwide are not meeting the aerobic component of the current World Health Organization (WHO)'s PA guidelines of at least 60 min of moderate-to-vigorous PA daily.7 A recent analysis of pooled data from 146 countries reported that an estimated 81% of young people (aged 11–17 years) globally are insufficiently active.8 In England 52.2% of children and young people are insufficiently active, and girls are more inactive than boys, with 49% of boys and 57% of girls not meeting the PA guidelines.9

There has been an increasing focus on the importance of national policy to address population levels of physical inactivity.9 Indeed, the WHO's Global Action Plan on Physical Activity highlighted the importance of scaling-up policy actions and government strategies for PA.10 A comprehensive policy framework for PA is recognized as an essential prerequisite for coordinating partnerships across sectors and securing political commitment for activities aimed at increasing the population's PA levels.11

Four key areas of policy have been identified as the cornerstones of a successful national policy framework. They are (1) national guidelines on PA, (2) national goals and targets, (3) surveillance or health-monitoring systems, and (4) public education.12,13 PA guidelines (Cornerstone 1) represent evidence-based consensus statements on the amount and type of PA needed to benefit health. Such guidelines may constitute an important information resource, guide national goal setting, and policy development, and they serve as primary benchmarks for PA monitoring and surveillance initiatives. Identifying specific and measurable targets within national policy (Cornerstone 2) can help to ensure that clear policy actions are identified and implemented and that relevant agencies are held accountable for progress. The availability of reliable information about PA trends and prevalence in populations (Cornerstone 3) is crucial for informing evidence-based interventions and policy. Communication campaigns (Cornerstone 4) typically use a variety of strategies to convey key messages about the importance of PA, including mass media, social media, and community events, to influence attitudes and motivation toward leading an active lifestyle.

Previous research has examined policy actions addressing each of these policy components in England in relation to adults’ PA.14 Given the importance of PA for the current and future health of children and young people, the aim of this study was to review the policy actions that have addressed each of these elements for children and young people in England and to identify areas of progress and remaining challenges. Responsibility for PA policy in England has fallen mostly to the Department of Health. However, policies that influence children and young people's PA have also been produced by other departments, including the Department for Education and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport.

2. Methods

The methods were consistent with an earlier review of the 4 cornerstones of PA policy among adults.14 A literature and Web search was undertaken to identify key documents associated with PA policy in England related to children and young people. The mid-1990s to the late-2010s (1994–2019) formed the focus of the current review, reflecting the past 25 years. The web search focused predominantly on gov.uk, the public sector information website created by the Government Digital Service, to provide a single point of access to government services in the United Kingdom (UK). The search term “physical activity” was used, and all identified documents were considered. This search elicited key policy documents for PA from several UK government departments with the responsibility for the promotion of PA and sport in England, including the Department of Health and Social Care, the Department for Education and the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. The policy documents included those relating to national guidelines on PA and key strategy documents. Other websites that were searched included Sport England, which is funded by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Sport England is responsible for the delivery of sport and PA opportunities in England and is a main source of national data on children and young people's PA. In addition, reference searches and citation searches were conducted in order to identify and obtain any other relevant documents. A total of 2996 unduplicated documents were retrieved.

The lead author (AC) screened each document to identify content relevant to the 4 key elements of policy that formed the focus of this review. A 10% sample of excluded documents were verified by the second author (KM). For the included documents (n = 54), an in-depth content analysis was undertaken. The lead author (AC) extracted any content related to each of the 4 cornerstones, taking into account both the text and the specific context. This involved reading each document and identifying text (e.g., phrases, sentences, and passages) that focused on one or more of the cornerstones. Relevant text was copied from each record and pasted into a separate file and was treated as data for this study. The second author (KM) verified all data extraction and interpretation, and any differences were resolved through discussion.

3. Results

This review focused on 4 key aspects of PA policy: (1) national guidelines on PA, (2) national goals and targets, (3) surveillance or health-monitoring systems, and (4) public education. A summary of the findings for each policy component is presented below.

3.1. National guidelines on PA levels

In 1997, the Heath Education Authority commissioned a group of experts to prepare review papers concerning 8 key aspects related to the field of PA and young people, including existing guidelines for children and young people and the relationship between PA and health. Drafts of these review papers were presented at a 2-day symposium called Young and Active?, which brought together more than 50 UK-based and international academics and experts from a range of disciplines within the field of young people and PA. This symposium informed the policy framework on children's PA, Young and Active?, which included, for the first time, PA guidelines for children and young people.15 These PA guidelines were later endorsed in a landmark document from the Chief Medical Officer (CMO), At Least Five a Week; the document was published in 2004.16

Four years later, in 2008, the Department of Health commissioned a review and update of the PA guidelines. This was prompted by updates to the PA guidelines in other countries (e.g., the United States and Canada) and an ambition to work toward a harmonized set of PA guidelines across the UK. The outcome of this review was published 3 years later, in 2011, in the form of Start Active, Stay Active: A Report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers.17 These new CMO guidelines included a greater focus on the additional health benefits brought about by vigorous PA and the potential risk of sedentary behavior.

The most recent guidelines were published in 201918 in response to updates from the United States,1 Canada,19 and the Netherlands.20 Only slight tweaks were made to the earlier guidelines, demonstrating that epidemiological evidence from the past 8 years has not substantially changed our understanding of the relationship between PA and health. The recommendations from each set of guidelines are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of the PA guidelines for children and young people (5–18 years old) in England.

| Document | Moderate-to-vigorous aerobic PA | Muscle- and bone-strengthening activities | Sedentary behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young and active? (1997)15 | All young people should participate in PA of at least moderate intensity for 1 h per day. Young people who currently do little activity should participate in PA of at least moderate intensity for at least 30 min per day. |

At least twice a week, young people should engage in some activities that help enhance muscular strength, flexibility, and bone health. | N/A |

| Start active, stay active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers (2011)17 | All children and young people should engage in moderate-to-vigorous PA for at least 60 min, and up to several hours, every day. | Vigorous intensity activities, including those that strengthen muscle and bone, should be incorporated at least 3 days a week. | All children and young people should minimize the amount of time spent being sedentary (sitting) for extended periods. |

| UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity guidelines (2019)18 | Children and young people should engage in moderate-to-vigorous PA for an average of at least 60 min per day across the week. This can include all forms of activity, such as physical education, active travel, after-school activities, play, and sports. | Children and young people should engage in various types and intensities of PA across the week to develop movement skills, muscular fitness, and bone strength. | Children and young people should aim to minimize the amount of time spent being sedentary and, when physically possible, should break up long periods of not moving with at least light PA. |

Abbreviations: PA = physical activity; N/A = not applicable.

3.2. National goals and targets

Whereas the setting of goals and targets around PA for adults has focussed on the proportion of the population meeting recommended PA levels,14 goals and targets in relation to children and young people have focused primarily on the provision of PA opportunities.

The Physical Education, School Sport and Club Links strategy marked the first specification of a national target for children's participation in physical education (PE) and school sport.21 It sought to ensure that 75% of children and young people spend a minimum of 2 h a week in high-quality PE and school sport within and beyond the curriculum by 2006 and that 85% of children and young people meet that goal by 2008. At the time the target was set, approximately one-quarter of schools met this goal at Key Stage 1 (5–7 years), two-fifths met it at Key Stage 2 (7–11 years), and a third met it at Key Stage 3 (11–14 years) and Key Stage 4 (14–16 years).21 A Key Stage is a stage of the state education system which, in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland, sets the educational knowledge expected of students at various ages.

The subsequent Physical Education, School Sport and Young People Strategy set out an even more ambitious success measure, known as the “five-hour offer”.22 For individuals 5–16 years old, the expectation was that schools would provide 3 h of the 5 h, with 2 h a week provided through high-quality PE within the curriculum and at least 1 h a week of sport provided for all young people beyond the curriculum (out-of-school hours on school sites). Community and club providers sought to ensure additional 2 h a week where available. At the time this target was set, it was estimated that only around 10% of individuals 5–16 years old and around 17% of individuals 16–19 years old participated in the 5 h of sport each week.23

Whilst the majority of the policy during this period focussed primarily on school provision of PE and sport, other types of provision with specific goals and targets included school travel plans24 and the availability of sports clubs.25 Notably, however, no target has ever been set for increasing the proportion of children and young people meeting the CMO PA guidelines. A summary of the national goals and targets relating to children's PA is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

A summary of national goals and targets relating to children's PA in England.

| Strategy | Key components |

|---|---|

| Physical education, school sport and club links (2002)21 | The overall objective was to enhance the take-up of sporting opportunities by individuals 5–16 years old. Included a target to ensure that 75% of children and young people spend a minimum of 2 h a week on high-quality PE and school sport within and beyond the curriculum by 2006 and 85% by 2008. |

| Sustainable schools for pupils, communities and the environment—An action plan for the DfES (2006)24 | A joint Department for Children, Schools and Families and Department for Transport target for all schools to have an approved school travel plan that addressed sustainability and pupil health and fitness by March 2010. |

| Physical education school sport for young people (2008)22 | The overall objective was to create a world-class system for PE and sport for all children and young people and improve the quality and quantity of PE and sport undertaken by young people aged 5–19 years. This relates to the target to “deliver a successful Olympic Games and Paralympic Games with a sustainable legacy and get more children and young people taking part in high-quality PE and sport”. Consequently, the strategy included an ambitious measure referred to as the “five-hour offer”. For individuals 5–16 years old, the expectation was that schools would provide 3 h of the 5 h per week, with 2 h per week provided through high-quality PE within the curriculum. At least 1 h per week of sport for all young people would be provided beyond the curriculum (out-of-school hours on school sites). Community and club providers sought to ensure additional 2 h a week, where available. |

| Creating a sporting habit for life (2012)25 | The overall objective was to support an increase in the proportion of people regularly playing sport, in particular, to raise the percentage of individuals 14–25 years old who play sport for at least 30 min each week and to establish a lasting network of links between schools and sports clubs in local communities so that young people keep playing sport up to and beyond the age of 25 years. |

Abbreviations: DfES = Department for Education and Skills; PA = physical activity; PE = physical education.

3.3. Monitoring and surveillance

The first national survey to assess childrens’ and young peoples’ PA levels was the Young People and Sport National Survey, conducted in 1994 by Sport England (called the English Sports Council at the time).26 Since then, there have been many surveys that have assessed children's PA levels. These surveys have been led by a range of organizations, have been undertaken infrequently over time, and have included various domains of activity, such as school PE, leisure-time activity, and active travel (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of national surveillance of children's physical activity levels.

| Survey | Lead agency | Year established | Subsequent survey years | Age of sample (year) | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people and sport in England26 | The English Sports Council, 1994 Sport England, 1999 and 2002 |

1994 | 1999 2002 2002 |

6–16 |

|

| Health survey for England27 | Department of Health | 1995–1996 | 2006 2007 2008 2012 2015 |

2–15 |

|

| Young people health related behaviour survey41 | Schools Health Education Unit | 2000 | N/A | 10–15 |

|

| National diet and nutrition survey42 | ONS and the Medical Research Council Human Nutrition Research | 2000 | N/A | 1.5–4.5 4–18 |

Unknown |

| Taking part survey43 | Department for Culture, Media and Sport | 2005/06 | 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 2017/18 2018/19 |

5–15 |

|

| National diet and nutrition survey44 | Public Health England and the UK FSA | 2008/09 | 2009/10 2010/11 2011/12 2012/13 2013/14 2014/15 2015/16 2016/17 |

1.5–3.3 4–10 11–18 |

|

| Health behaviour in school-aged children45 | WHO Regional Office for Europe | 2009/10 | 2014 2018 |

11–15 |

|

| What about YOUth46 | Department of Health | 2014 | N/A | 15 |

|

| Active lives children and young people survey28 | Sport England | 2017/18 | 2018/19 2019/20 |

5–16 |

|

Abbreviations: FSA = Food Standards Agency; N/A = not applicable; ONS = Office for National Statistics; PA = physical activity; WHO = World Health Organization.

The Health Survey for England has been the primary source of data for the national prevalence of PA among children. The survey sample includes children aged 2–15 years, with proxy reports taken from parents for those under 12 years old. PA among children was initially measured via the Health Survey for England from 1995 to 199627 and had been measured subsequently in surveys taken in 2002, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2012, and 2015. The same questionnaire had been used in each survey, allowing for the monitoring of secular trends and assessment of the impact of public health policy on population levels of PA. The survey does not, however, provide an estimate of prevalence against the full set of PA guidelines because it assesses moderate-to-vigorous PA only. Muscle-strengthening activity is not measured in the survey, and the inclusion of questions on sedentary behavior has been sporadic.

The Active Lives Children and Young People Survey was established by Sport England in 2017, and the first set of results was published in 2018.28 It is among the largest national surveillance surveys of children and young people (aged 5–16 years) worldwide. It is being conducted annually and assesses children's and young people's attitudes toward and behaviors concerning PA and sport. The survey is conducted through schools, which are randomly selected each term; and 100,000 children and young people are recruited to complete the survey during each academic year. The large sample size enables Sport England to produce data at the national, regional, and local levels to inform government policy as well as local decision making.

3.4. Public education

Change4Life was the social marketing campaign element of Healthy Weight, Healthy Lives, the cross-government obesity strategy published in January 2008.29 The campaign was targeted to parents of children between the ages of 5 and 11 years as part of a multi-component strategy to reduce childhood obesity. Although the campaign was initially targeted to adults, the images and language used have always been child friendly.

The Change4Life campaign targets both diet and PA, although there has been greater emphasis and action around diet. To promote PA, Change4Life has partnered with Disney to create a range of “10-min shake up games”, including Elsa's Freeze Tag (from the movie Frozen) and Jumping with Destiny (from the movie Finding Dory). In terms of diet, a wide range of actions has been taken, including the development of easy recipes, help in understanding food labels, and guidance in choosing more healthful snacks. Change4Life has been sustained over the past 11 years through a range of funding sources. Current funders, however, include Britvic, a leading manufacturer of sugar-sweetened beverages.30

There has been limited evaluation of the Change4Life campaign, beyond the number of people exposed to it31 (i.e., those who sign up to receive resources or download the app). Therefore, the impact of the campaign on children's PA levels is unknown. Based on national surveillance data, the prevalence of PA among children has decreased over the period of the campaign, while the prevalence of obesity has remained static. In 2008, before the launch of the campaign, 32% of boys and 24% of girls aged 5–15 years were meeting the aerobic PA recommendation.32 The latest data, from 2015, show that PA prevalence has decreased to 23% among boys and 20% among girls.33 In 2008, 17% of boys and 15% of girls were classified as obese.32 The latest data from 2018 show that the values have remained at 17% and 15%, respectively, demonstrating that no reduction in obesity for either gender has taken place over this 10-year period.34

The regular reviews and updates of the PA guidelines have not previously been supported by a communication strategy that educates the public and professionals; hence, knowledge of the PA guidelines has remained consistently low. For example, it is estimated that just 18% of adults in England are aware of the PA guidelines,35 and only 20% of health professionals are “broadly familiar” with them.36 To address the lack of knowledge and awareness of the PA guidelines, the Department of Health and Social Care commissioned a set of infographics37 aimed at making the information more accessible. The series of infographics was published throughout 2017 and represented the various guidelines recommended throughout the life course. These include guidelines for children under 5 years of age, children and young people (aged 5–18 years), and adults and older adults (aged 19 years and older).37 The infographics have been updated to reflect the changes in the guidelines that were made following the 2019 review; however, details of their dissemination and usage have not yet been evaluated.

4. Discussion

There have been many developments in national PA policy in England targeted at children and young people. PA guidelines (Cornerstone 1) for children and youth have been in place since 1998 and have been reviewed periodically. PA targets (Cornerstone 2) have focussed on the provision of opportunities for PA, mainly through PE in schools rather than in relation to the proportion of children meeting recommended PA levels. There has been much surveillance (Cornerstone 3) of children's PA, but this has been undertaken infrequently over time and with varying inclusions of differing domains of activity. There has been only 1 campaign (Cornerstone 4) targeted to children and their intermediaries, which was an obesity campaign (Change4Life) focussing on dietary behavior in combination with PA. More recently, a government infographic supporting the PA guidelines for children and young people was developed, but details of its dissemination and usage are unknown.

National guidelines on children's PA have been established since 1998, yet a significant milestone in the development of PA guidelines was the publication of At Least Five a Week in 2004.16 This document presented the first in-depth review of the impact of PA on health for differing population groups and was officially endorsed by the CMO. The publication of Start Active, Stay Active in 2011 presented the first set of UK-wide PA recommendations, as well as recommendations for all age groups, from “cradle to grave”.17 Prior to 2011, PA guidelines were inconsistent across the 4 UK home-nations and were available only for specific age groups. A robust, scientific process to collate and synthesise the evidence has been successively adopted; this process includes reviews of the evidence, stakeholder engagement, scientific meetings, and wider consultation. Consequently, this represents an area of PA policy where much progress has been made, and good practice has been demonstrated. The PA guidelines should continue to be updated regularly in response to the developing epidemiological evidence base.

Setting goals and targets increases accountability and, as such, can often drive investment. This was seen in the early 2000s, following the publication of the Physical Education, School Sport and Club Links Strategy.21 This strategy marked the beginning of substantial increases in government funding for PE and school sport, with the subsequent Physical Education, School Sport and Club Links Strategy being supported by an unprecedented investment of GBP783 million.22 The successful bid to host the 2012 Olympics led to the development of further goals to support children and young people to be physically active and provided a catalyst for policy aimed at increasing participation. However, national goals and targets in relation to children's PA have focused exclusively on the delivery and accessibility of PA opportunities rather than on the proportion of the population meeting recommended PA levels. Developing prevalence targets aligned to the PA recommendations is advocated to hold policymakers to account and to ensure that success is measured, not only in relation to the opportunities provided to children and young people but also the impact of those opportunities on participation levels. This would encourage more robust evaluation of “what works” to get children and young people more active, which would help to inform subsequent decision making and the distribution of resources.

Surveillance of children and young people's PA in England has been an area of considerable progress; however, interest in this area has led to many different stakeholders’ and organizations’ undertaking different surveys and to an apparent lack of coherence. The Health Survey for England has been successfully implemented over time to provide secular trend data, and the scale of the new Active Lives Survey means it can provide a detailed analysis of children's PA at the local level. A limitation of these surveillance systems is that they assess participation in aerobic PA only. The Health Survey for England periodically assesses sedentary behavior, but neither of the leading surveys measure muscle-strengthening activity. The data, therefore, provide only a partial indicator of children's PA and not an accurate estimate of the proportion of children meeting the CMO's recommended levels. Furthermore, while the PA guidelines in England are now consistent with the other 4 home nations, each country uses different surveillance systems, limiting comparability and data pooling. Expanding surveillance systems to measure all aspects of the PA guidelines, as well as harmonizing the tools and methods used across the UK, would strengthen current practice. This should be informed by a review of current practice and through consultation with the survey leads in each country. A further consideration is that future surveillance systems should be aligned (in their timing and objectives) to measure progress in achieving any specific goals and targets that are set.

PA guidelines have been described as the “first link in a chain of communication to inform behaviour change”.17 However, the development of national PA guidelines is rarely complemented by a coherent strategy for how to disseminate and communicate them to various audiences.38 Public education (e.g., through mass media, social media, educational resources, and community events) provides an effective way to transmit clear and consistent messages about PA to large populations.

The implementation of public education campaigns is underpinned by robust evidence that appropriate and well-resourced campaigns are effective in influencing knowledge, awareness, and motivation towards PA.39,40 However, public education, in isolation, is unlikely to lead to PA behavior change; it must be supported by appropriate policies, environments, and opportunities for PA. The government has demonstrated a sustained commitment to Change4Life, having implemented the campaign for 11 years. An evaluation report was produced following the first year of the campaign, but it focussed mainly on exposure to the campaign as opposed to any attitudinal or behavioral outcomes.31 Surveillance data suggest that levels of PA among children are not increasing, and levels of obesity are not decreasing. More robust evaluations of public-education campaigns are needed to understand the most effective messages and delivery channels as well as the frequency and dose of delivery required to achieve different outcomes, including changes in knowledge and behavior.

These 4 cornerstones of policy underpin national efforts for PA promotion, but integrated action is needed to ensure that the right policies, environments, and opportunities are in place to encourage and support children and young people in being more active. A strategic combination of upstream policy actions, which address contextual factors that shape children and young people's health across a range of political, social, cultural, environmental, and economic sectors and settings, combined with downstream approaches which are individually focused, such as educational and information approaches, are needed to promote equitable access to opportunities to be active.10

5. Conclusion

This study has identified areas of progress as well as remaining challenges in 4 key areas of national PA policy in England. The area of greatest progress has been the development of national PA guidelines. Establishing clear prevalence targets, providing greater coherence and synergy across surveillance systems, and investing in public education with supportive policies, environments, and opportunities would strengthen national policy efforts to promote PA.

Authors’ contributions

AC conceived the study, conducted the literature search, drafted of the manuscript, and led the document analysis; KM conceived the study, drafted the manuscript, and verified the document analysis. Both authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

Both authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

References

- 1.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Committee scientific report. Available at: https://health.gov/paguidelines/second-edition/report/. [accessed 02.02.2020]

- 2.Telama R, Yang X, Viikari J, Välimäki I, Wanne O, Raitakari O. Physical activity from childhood to adulthood. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Telama R. Tracking of physical activity from childhood to adulthood: A review. Obes Facts. 2009;2:187–195. doi: 10.1159/000222244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Telama R, Yang X, Leskinen E. Tracking of physical activity from early childhood through youth into adulthood. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2014;46:955–962. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Dalene KE. Variations in accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time across Europe: Harmonized analyses of 47,497 children and adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17:38. doi: 10.1186/s12966-020-00930-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lounassalo I, Salin K, Kankaanpää A. Distinct trajectories of physical activity and related factors during the life course in the general population: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:271. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6513-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . 2010. Global recommendations on physical activity for health.http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/factsheet_recommendations/en/ Available at: [accessed 02.01.2020] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Global trends in insufficient physical activity among adolescents: A pooled analysis of 298 population-based surveys with 16 million participants. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30323-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Breda J, Jakovljevic J, Rathmes G. Promoting health-enhancing physical activity in Europe: Current state of surveillance, policy development and implementation. Health Policy. 2018;122:519–527. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030. Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 11.Bull F, Milton K, Kahlmeier S. Health-Enhancing Physical Activity (HEPA) Policy Audit Tool (PAT). Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/disease-prevention/physical-activity/publications/2015/health-enhancing-physical-activity-hepa-policy-audit-tool-pat-version-2-2015. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 12.Bull FC, Bellew B, Schöppe S, Bauman AE. Developments in national physical activity policy: An international review and recommendations towards better practice. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7:93–104. doi: 10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. A guide for population-based approaches to increasing levels of physical activity: Implementation of the WHO global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. Available at: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/PA-promotionguide-2007.pdf. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 14.Milton K, Bauman A. A critical analysis of the cycles of physical activity policy in England. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0169-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biddle S, Sallis JF, Cavill N. Health Education Authority; London: 1997. Young and active? [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health . Department of Health; London: 2004. At least five a week: Evidence on the impact of physcal activity and its relationship to health. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health. Start active, stay active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/start-active-stay-active-a-report-on-physical-activity-from-the-four-home-countries-chief-medical-officers. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 18.Department of Health and Social Care UK Chief Medical Officers’ physical activity guidelines. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-uk-chief-medical-officers-report Availale at: [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 19.Tremblay MS, Carson V, Chaput JP. Introduction to the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for children and youth: An integration of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41(Suppl. 3) doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0203. iii–iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Health Council of the Netherlands. Advisory Report Physical Activity Guidelines 2017. Available at: https://www.healthcouncil.nl/documents/advisory-reports/2017/08/22/physical-activity-guidelines-2017. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 21.Department for Education and Skills, Department for Culture Media and Sport . Department for Education and Skills; London: 2002. Learning through PE and sport: A guide to the physical education, school sport and club links strategy. [accessed 02.01.2020] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sport England, Youth Sport Trust . Sport England; London: 2008. The PE and sport strategy for young people: A guide to delivering the five hour offer. [Google Scholar]

- 23.DCMS, DCSF. PE and sport strategy for young people leaflet. Available at: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20120505035838/https://www.education.gov.uk/publications/eOrderingDownload/PE_Sport_Strategy_leaflet_2008.pdf. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 24.Department for Education and Skills. Sustainable schools for pupils, communities and the environment—An action plan for the DfES. Available at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6600/1/SustSchUN.pdf%5Cnhttps://think-global.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/dea/documents/DEA_Response_sust_schools.pdf. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 25.Department for Culture Media and Sport Creating a sporting habit for life: A new youth sport strategy. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/78318/creating_a_sporting_habit_for_life.pdf Available at: [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 26.Mason V. Sports Council; London: 1995. Young people and sport in England, 1994: The views of teachers and children. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joint Health Surveys Unit of Social and Community Planning Research and University College London . 1996. Health survey for England 1995–. Colchester, Essex: SCPR and UCL; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sport England. Active lives children and young people survey academic year 2017/18. Available at: https://www.sportengland.org/media/13698/active-lives-children-survey-academic-year-17-18.pdf. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 29.Department of Health. Healthy weight, healthy lives: A cross-government strategy for England. Available at:http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113486%5Cnhttp://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_112529%5Cnhttp://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/2. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 30.Public Health England. How we work. Available at: https://campaignresources.phe.gov.uk/resources/partners/national-partners. [accessed 27.03.2020]

- 31.TNS-BNRB . TNS-BNRB; London: 2010. Change4Life tracking study. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The NHS Information Centre . 2009. Health survey for England 2008: Physical activity and fitness: Summary of key findings. London: The NHS Information Centre; [Google Scholar]

- 33.Health and Social Care Information Centre . 2016. Health survey for England 2015: Physical activity in children. Leeds: NHS Digital; [Google Scholar]

- 34.NHS Digital . NHS Digital; Leeds: 2019. Health survey for England 2018 overweight and obesity in adults and children. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knox ECL, Esliger DW, Biddle SJH, Sherar LB. Lack of knowledge of physical activity guidelines: Can physical activity promotion campaigns do better? BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chatterjee R, Chapman T, Brannan MG, Varney J. GPs’ knowledge, use, and confidence in national physical activity and health guidelines and tools: A questionnaire-based survey of general practice in England. Br J Gen Pract. 2017;67:e668–e675. doi: 10.3399/bjgp17X692513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Department of Health and Social Care. Physical activity guidelines: Infographics. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/physical-activity-guidelines-infographics. [accessed 02.01.2020]

- 38.Kahlmeier S, Wijnhoven TMA, Alpiger P, Schweizer C, Breda J, Martin BW. National physical activity recommendations: Systematic overview and analysis of the situation in European countries. BMC Pub Health. 2015;15:133. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1412-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stead M, Angus K, Langley T. Mass media to communicate public health messages in six health topic areas: A systematic review and other reviews of the evidence. Public Heal Res. 2019;7:1–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.International Society for Physical Activity and Health ISPAH's eight investments that work for physical activity. www.ispah.org.uk Available at: [accessed 02.01.2020] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Balding J. Young People in 2000: The heath-related behaviour questionnaire results for 42,073 young people between the ages of 10 and 15. Available at: http://sheu.org.uk/sheux/yppdf/yp00/7.pdf. [accessed 11.08.2020]

- 42.Smithers G, Gregory JR, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Jackson LV, Wenlock R. The national diet and nutrition survey: Young people aged 4–18 years. Nutr Bull. 2000;25:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport. Taking part survey. Technical report: Taking part survey, 2005 to 2006 (Year1). Available at:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/technical-report-taking-part-survey-2005-to-2006-year-1. [accessed 02.01.2020].

- 44.Public Health England, Food Standards Agency. National diet and nutrition survey. Available at:https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-diet-and-nutrition-survey-results-from-years-1-to-4-combined-of-the-rolling-programme-for-2008-and-2009-to-2011-and-2012. [accessed 02.01.2020].

- 45.Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2012. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Health and Social Care Information. Health and wellbeing of 15-year-olds in England; Main findings from the What About YOUth? Available at:https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/health-and-wellbeing-of-15-year-olds-in-england-main-findings-from-the-what-about-youth-survey-2014. [accessed 02.02.2020].