Summary

Mesenchymal tumours represent one of the most challenging field of diagnostic pathology and refinement of classification schemes plays a key role in improving the quality of pathologic diagnosis and, as a consequence, of therapeutic options. The recent publication of the new WHO classification of Soft Tissue Tumours and Bone represents a major step toward improved standardization of diagnosis. Importantly, the 2020 WHO classification has been opened to expert clinicians that have further contributed to underline the key value of pathologic diagnosis as a rationale for proper treatment. Several relevant advances have been introduced. In the attempt to improve the prediction of clinical behaviour of solitary fibrous tumour, a risk assessment scheme has been implemented. NTRK-rearranged soft tissue tumours are now listed as an “emerging entity” also in consideration of the recent therapeutic developments in terms of NTRK inhibition. This decision has been source of a passionate debate regarding the definition of “tumour entity” as well as the consequences of a “pathology agnostic” approach to precision oncology. In consideration of their distinct clinicopathologic features, undifferentiated round cell sarcomas are now kept separate from Ewing sarcoma and subclassified, according to the underlying gene rearrangements, into three main subgroups (CIC, BCLR and not ETS fused sarcomas) Importantly, In order to avoid potential confusion, tumour entities such as gastrointestinal stroma tumours are addressed homogenously across the different WHO fascicles. Pathologic diagnosis represents the integration of morphologic, immunohistochemical and molecular characteristics and is a key element of clinical decision making. The WHO classification is as a key instrument to promote multidisciplinarity, stimulating pathologists, geneticists and clinicians to join efforts aimed to translate novel pathologic findings into more effective treatments.

Key words: WHO classification, soft tissue sarcoma, new entity, molecular genetics, morphology

Introduction

The publication of the new WHO classification always generates within the sarcoma community great expectations. Mesenchymal tumours are in fact regarded as one of the most challenging fields of diagnostic pathology and refinement of classification schemes is perceived as the cornerstone around which improving the quality of both pathologic diagnosis and therapeutic options 1. Published data indicate in sarcoma a rate of diagnostic inaccuracy ranging between 20 and 30% 2-4. However, this is not at all due to pathologists’ negligence. As a matter of fact, there exist objective factors that appear to impact negatively over both the accuracy and the reproducibility of pathologic diagnosis, factors the pathologist have always tried to overcome through specific strategies, most of all by implementation of diagnostic second opinion in expert centers or within collaborative networks 5. Four main sources of challenge can be identified.

Rarity. Sarcomas as a whole are characterised by an incidence of approximately 5 cases/100,000 thus matching the formal definition of a rare tumor 6. However, soft tissue malignancies are further subclassified in approximately 70 subtypes, each characterized by a distinct morphology, that often translates into a specific clinical behaviour as well as into specific therapeutic approaches. Moreover, many histotypes are exceedingly rare (in the range of 0.1 cases/100,000), to the extent that a pathologist not working in a high-volume centre may not encounter them for years. In this scenario, achieving specific expertise represents undoubtedly a challenge.

Intrinsic complexity. Mesenchymal tumours are characterised by specific diagnostic peculiarities. First of all, the mere application of morphologic criteria of malignancy used for epithelial cancer are not always applicable. The best example is represented by nodular fasciitis, a benign condition most often occurring in the forearm of a young adults, who exhibits clinicopathologic features (rapid growth, hypercellularity and high mitotic activity) that in the context of an epithelial cancer would be highly supportive of a diagnosis of malignancy. The relatively frequent violation of diagnostic criteria of malignancy appears to represent a unique feature of mesenchymal tumours and represents one of the major reasons for diagnostic inaccuracy.

Technological complexity. The diagnostic process of mesenchymal tumours relies upon a complex combination of conventional microscopic morphology, immunohistochemistry, and molecular genetics 7. This requires state of the art molecular technology that more and more includes Next Generation Sequencing approaches 8. In contrast with popular belief molecular genetics requires high professional expertise coupled with even higher quality control standards (as compared for example to immunohistochemistry). In this perspective, it is quite intuitive that centralisation of molecular diagnostics in high volume centres is mandatory on order to maintain high analytic quality 9.

Lower impact of educational efforts. Even if education still plays a fundamental role in increasing diagnostic expertise, it has to be admitted that in the field of rare cancers its efficacy is somewhat hampered. Unless a pathologist is continuously exposed to soft tissue tumours diagnostics, the expertise developed through educational efforts is at risk of being gradually lost.

The field of sarcoma oncology is rapidly evolving through the development of an even close correlation between pathologic diagnosis and tailored treatments 10-16. The WHO classification of soft tissue tumours, since 1999 17-19. has introduced a profound change in its methodological approach aimed to support a more rational therapeutic approach. Major changes can be summarised as follows:

Integration of morphology with immunohistochemistry and molecular genetics. The marriage between morphology and genetics by direct involvement of cytogeneticists has certainly represented a major step forward.

Involvement of a broad number of sarcoma expert pathologists. This approach has minimised the risk of generation of “opinion-leader” bias and has led to a broader diffusion of the classification among pathologists.

Precise definition of clinicopathological categories. It is now broadly accepted that in between benign and malignant categories there exists an ”intermediate” category of lesions that can be either locally aggressive (i.e. desmoid fibromatosis) or rarely metastasizing (i.e. plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumour).

Involvement of clinicians. For the first time the 2020 WHO classification of soft tissue and bone tumours, representatives of clinical disciplines such as medical, surgical and radiation oncology have been directly involved. This close interaction has strongly enhanced the clinical value of pathological diagnosis.

The aim of this paper is to review the main advances contained in the current classification and also discuss new perspectives that most likely will generate some debate in the years to come. In consideration of the complexity of the new classification and despite the fact that some soft sarcomas can rarely arise primarily in bone 20, with the exception of undifferentiated round cell sarcoma that can occur both in soft tissue and bone, we will focus on tumours of the soft tissue.

Advances in classification

ADIPOCYTIC TUMOURS

The entities characterised by adipocytic differentiation are listed in Table I. Newcomers are represented by atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomatous tumour and myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma. Importantly, both lesions are now regarded as benign and therefore treated with simple surgical excision.

Table I.

Adipocytic tumours.

| Benign |

| Lipoma and lipomatosis |

| Lipomatosis of nerve |

| Lipoblastoma and lipoblastomatosis |

| Angiolipoma |

| Myolipoma of soft parts |

| Chondroid lipoma |

| Spindle cell/pleomorphic lipoma |

| Atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic atypical lipomatous tumor |

| Hibernoma |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) |

| Atypical lipomatous tumor |

| Malignant adipocytic tumours |

| Well differentiated liposarcoma: lipoma-like, sclerosing, inflammatory |

| Dedifferentiated liposarcoma |

| Myxoid liposarcoma |

| Pleomorphic liposarcoma |

| Myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma |

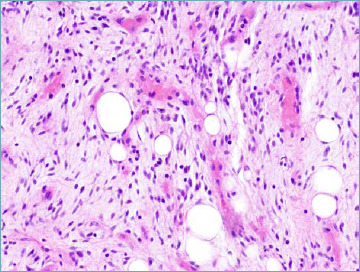

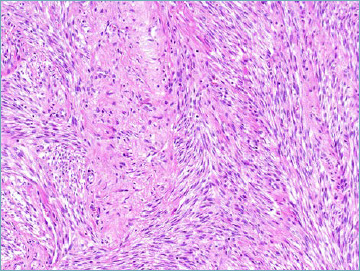

The label atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumour represents a new name for the entity formerly known as spindle cell liposarcoma 21,22 and at the time of first description regarded as a variant of well differentiated liposarcoma. The entity is now defined as an ill-circumscribed, moderately atypical spindle cell tumour featuring the presence of a variable number of lipoblasts. Matrix can vary from fibrous to myxoid (Fig. 1A). A remarkable tendency to occur superficially is observed. The new label is justified by the distinctively indolent clinical course. Separation from the group of well differentiated liposarcoma/atypical lipomatous tumour is also justified by the fact that atypical spindle cell tumour is not driven genetically by the amplification of MDM2 and/or CDK4 genes. In further contrast dedifferentiation (i.e. transition from low grade to high grade histology) seems not to occur.

Figure 1A.

Atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor. The tumor is composed of mildly atypical, hyperchromatic, spindle cells, and adipocytic cells set in a myxocollagenous stroma. A bivacuolate lipoblast is seen.

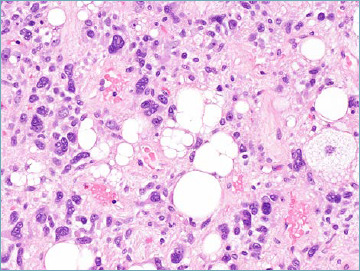

Atypical pleomorphic lipomatous tumour has been recently introduced to recognise the existence of examples of pleomorphic lipoma that, while keeping some key diagnostic features (presence of florette-like multinucleated giant cells as well as of coarse eosinophilic collagen bundles) exhibit higher cellularity, increased mitotic activity and presence of numerous lipoblasts, however without reaching histologic criteria consistent with the diagnosis of pleomorphic liposarcoma 23 (Fig. 1B). Atypical pleomorphic lipomatous tumour, despite alarming morphology, is characterised by a benign clinical behaviour that contrasts with the remarkable aggressiveness of pleomorphic liposarcoma.

Figure 1B.

Atypical pleomorphic lipomatous tumor. The presence of multivacuolated lipoblasts is accepted.

Both spindle and pleomorphic atypical lipomatous tumours occur most often in the limbs and limb girdles of middle-aged patients. Importantly, they can rarely arise at visceral locations including the retroperitoneum. From a molecular standpoint RB1 gene loss is frequently observed that translates into loss of nuclear RB1 immunoreactivity. As mentioned, both lesions tend to exhibit a low rate of recurrence that seems to be limited to lesions excised incompletely.

Myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma is an exceedingly rare adipocytic malignancy, and is characterised by occurrence in children and adolescents with female predominance 24. Most common anatomic sites are represented by the mediastinum followed by the limbs and the head and neck region. Morphologically myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma shows features of both myxoid (presence of a rich capillary size vascular network set in myxoid background) and pleomorphic liposarcoma (presence of pleomorphic lipoblasts (Fig. 1C). No specific genetic aberrations have been so far detected. Clinical behaviour is aggressive with a high recurrence rate and early metastatic spread to the lungs, bone, and soft tissues. It should be remembered that true myxoid liposarcomas almost never occurs in children, those reported case most likely representing examples of lipoblastoma 25,26.

Figure 1C.

Myxoid pleomorphic liposarcoma. Neoplastic cells are set in a myxoid stroma with plexiform vascular pattern. Rare pleomorphic lipoblasts can be observed.

FIBROBLASTIC/MYOFIBROBLASTIC TUMOURS

The entities characterised by fibroblastic/myofibroblastic differentiation are listed in Table II. Despite representing one of the larger groups, only three new benign entities are considered in the new classification: angiofibroma of soft tissues 27, EWSR1-SMAD3 positive fibroblastic tumour 28, and superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumour 29.

Table II.

Fibroblastic/myofibroblastic tumours.

| Benign |

| Nodular fasciitis |

| Proliferative fasciitis and proliferative myositis |

| Myositis ossificans and fibro-osseous pseudotumor of digits |

| Ischaemic fasciitis |

| Elastofibroma |

| Fibrous hamartoma of infancy |

| Fibromatosis colli |

| Juvenile hyaline fibromatosis |

| Inclusion body fibromatosis |

| Fibroma of tendon sheath |

| Desmoplastic fibroblastoma |

| Myofibroblastoma |

| Mammary-type myofibroblastoma |

| Calcifying aponeurotic fibroma |

| EWSR1-SMAD3-positive fibroblastic tumour (emerging) |

| Angiomyofibroblastoma |

| Cellular angiofibroma |

| Angiofibroma NOS |

| Nuchal fibroma |

| Acral fibromyxoma |

| Gardner fibroma |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) |

| Palmar/plantar-type fibromatosis |

| Desmoid-type fibromatosis |

| Lipofibromatosis |

| Giant cell fibroblastoma |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasising) |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, fibrosarcomatous |

| Solitary fibrous tumour |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumour |

| Low-grade myofibroblastic sarcoma |

| Superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumour |

| Myxoinflammatory fibroblastic sarcoma |

| Infantile fibrosarcoma |

| Malignant |

| Solitary fibrous tumour, malignant |

| Fibrosarcoma NOS |

| Myxofibrosarcoma |

| Low grade fibromyxoid sarcoma |

| Sclerosing epithelioid fibrosarcoma |

Angiofibroma of soft tissue is a benign lesion most often occurring in the subcutaneous soft tissues of the extremities of adult patients. Morphologically it is composed of a uniform spindle cell proliferation set in a variably myxoid and collagenous background, and associated with a remarkably rich thin-walled vascular network (Fig. 2A). Neoplastic cells express CD34 and EMA. Desmin positivity is often observed in dendritic cells. The presence of an AHRR-NCOA2 fusion gene is reported in the majority of cases 30.

Figure 2A.

Angiofibroma of soft tissue. A prominent vascular network composed of thin walled branching vessels represents one of the main features of this entity. The neoplastic spindle cells show inconspicuous palely eosinophilic cytoplasm.

EWSR1-SMAD3 fibroblastic tumour represents one of the new entities in which the name is determined by the involved fusion gene. It is a benign neoplasm most often occurring in the hands and feet with a broad age range. Morphologically it is composed of intersecting cellular fascicles of cytologically bland monomorphic spindle cells, alternating with hypocellular, hyalinised areas (Fig. 2B). Immunohistochemically it is characterized by nuclear expression of ERG.

Figure 2B.

EWSR1-SMAD3 fibroblastic tumour. Alternation of hyalinised hypocellular areas and more cellular areas composed of intersecting fascicles of monomorphic spindle cells is most often observed.

Superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumour occurs most often skin and subcutis of the lower extremities of middle-aged patients. Morphologically is composed of spindle and epithelioid cell proliferation, often featuring striking cytologic atypia that is associated with insignificant mitotic activity. Neoplastic cells invariably express CD34 (Fig. 2C). Importantly, despite alarming morphologic features no recurrences are reported following complete excision.

Figure 2C.

Superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumour. Striking cytologic atypia in absence of mitotic figures and necrosis is often present.

SO-CALLED FIBROHISTIOCYTIC TUMOUR

The category of fibrohistiocytic tumours is the group that through the last three editions of the WHO classification has lost most of the tumour entities. Currently recognised lesions are listed in Table III. The very concept of fibrohistiocytic differentiation is rather elusive as in most cases the histiocytic component is actually non-neoplastic. However, as happens in giant cell tumour, the histiocytic component contributes significantly to the development of the lesion. The most relevant entity that has disappeared since 2013 is represented by the family of so called malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), a group of lesions that until the early 2000 accounted for approximately 50% of sarcoma diagnoses 31-33. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma currently represents the correct label for the prototypical storiform and pleomorphic variant of MFH. Giant cell MFH is currently replaced by three distinct tumour types: giant cell tumour of soft tissues, extraskeletal osteosarcoma and giant cell rich osteosarcoma. Myxoid MFH is currently recognised as a purely fibroblastic tumour identified with the original name myxofibrosarcoma 34-36. So called inflammatory MFH overlaps entirely with the inflammatory variant of dedifferentiated liposarcomas 37, and so called angiomatoid MFH (a clinically indolent lesion most often harbouring a EWSR1-CREB1 fusion gene and, more rarely a EWSR1-ATF1 or a FUS-ATF1) is currently listed within the group of soft tissue lesion of unknown differentiation 38.

Table III.

So-called fibrohistiocytic tumours.

| Benign |

| Tenosynovial giant cell tumour |

| Deep benign fibrous histiocytoma |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasising) |

| Plexiform fibrohistiocytic tumour |

| Giant cell tumour of soft parts NOS |

| Malignant |

| Malignant tenosynovial giant cell tumour |

VASCULAR TUMOURS

The group of neoplasms featuring endothelial differentiation is also very heterogenous both in terms of degree of vasoformative morphology and biological behaviour (Tab. IV). It is worth stressing that despite the label implying an intermediate behaviour, epithelioid haemangioendothelioma (EHE) is actually ranked among vascular malignancies. This is the consequence of an overall metastatic rate of approximately 15%, and the tendency to be remarkably aggressive in specific anatomic locations such as lungs and pleura. Two morphological and molecular variants (CAMTA1 and TFE3-related) are recognised however at the moment no statistically significant differences in terms of clinical behaviour seems to emerge 39.

Table IV.

Vascular tumours.

| Benign |

| Synovial haemangioma |

| Intramuscular haemangioma |

| Arteriovenous malformation/haemangioma |

| Venous haemangioma |

| Anastomosing haemangioma |

| Epithelioid haemangioma |

| Lymphangioma and lymphangiomatosis |

| Acquired tufted haemangioma |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) |

| Kaposiform haemangioendothelioma |

| Retiform haemangioendothelioma |

| Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma |

| Composite haemangioendothelioma |

| Kaposi sarcoma |

| Pseudomyogenic haemangioendothelioma |

| Malignant |

| Epithelioid haemangioendothelioma |

| Angiosarcoma |

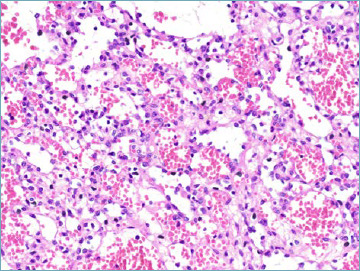

The single new entity appearing among vascular lesions is represented by a benign lesion named anastomosing haemangioma (AH). Initially reported in the male genital tract 40,41, anstamosing haemangioma most commonly occurs in the kidney and in the retroperitoneum of adults. Morphologically AH is composed of anastomosing capillary-sized vessels featuring scattered hobnail endothelial cells (Fig. 3). Anastomosing haemangioma is frequently misinterpreted as angiosarcoma, however if present endothelial atypia is mild, and is never associated with multilayering as is typically observed in angiosarcoma.

Figure 3.

Anastomosing haemangioma. Anastomosing capillary-sized vessels are lined by hobnail endothelial cells in absence of significant nuclear atypia.

PERICYTIC (PERIVASCULAR) TUMOURS

This group of lesions share morphologically the presence of a distinctive perivascular pattern of growth (Tab. V). Cell shape varies form epithelioid (such as in glomus tumour) to spindle as observed in myopericytoma/myofibroma and angioleiomyoma. It seems likely the whole group represents a spectrum of perivascular neoplasia exhibiting a variable contractile phenotype. Most of the lesions tend to exhibit a benign clinical course. The diffuse variants (glomangiomatosis and myofibromatosis) however are associated with significant local morbidity. Malignancy represents an extremely rare condition.

Table V.

Pericytic (perivascular) tumours.

| Benign and intermediate |

| Glomus tumour NOS |

| Myopericytoma, including myofibroma |

| Angioleiomyoma |

| Malignant |

| Glomus tumour, malignant |

Since 2013 the major advance is represented by the abolition of haemangiopericytoma 42. The original intuition of Arthur Purdy Stout represented by the recognition of neoplasms composed of perivascular contractile cells, remains absolutely valid, and is currently encompassed by myopericytoma. Unfortunately, through the decades hemangiopericytoma became the preferred label for unrelated lesions sharing an hemangiopericytic vascular pattern, namely the presence of dilated, branching, thin walled blood vessels. Most haemangiopericytomas are now recognized as examples of solitary fibrous tumours, however the list of lesions featuring haemangiopericytomas-like vessels is broad and includes among others myopericytoma/myofibroma, synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours, endometrial stroma sarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. Solitary fibrous tumour still represents a diagnostic challenge because as mentioned above can mimic many mesenchymal and non-mesenchymal unrelated tumour entities 43. The availability of STAT6 immunostaining has certainly contributed to improve diagnostic accuracy 44 and, most importantly, for the first time the prediction of the outcome of is not simply determined by mitotic count 45, but by a risk assessment scheme that considers, patient’s age, tumour size, depth of location, and mitotic index 46.

SMOOTH MUSCLE TUMOURS

The changes introduced in the category of soft tissue tumours featuring smooth muscle differentiation are represented by the inclusion as distinct entities of both EBV-associated smooth muscle tumours, and inflammatory leiomyosarcoma (Tab. VI).

Table VI.

Smooth muscle tumours.

| Benign |

| Leiomyoma |

| Intermediate |

| Smooth muscle tumour of uncertain malignant potential |

| EBV-associated smooth muscle tumour |

| Malignant |

| Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma |

| Leiomyosarcoma |

EBV-associated smooth muscle tumours are intimately associated with EBV infection most often in the context of immunosuppression 47. Age range is broad as anatomic location. HIV-associated lesions however tend to occur most often in the central nervous system whereas post-transplant proliferations feature a remarkable tropism for the liver, followed by the lungs and the gastrointestinal tract. Prognosis tends to be more related to the evolution of the state of immunosuppression

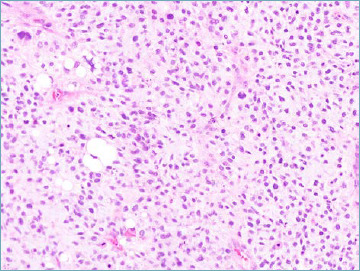

Most cases of inflammatory leiomyosarcoma occur in the deep soft tissues of the lower limbs, trunk and retroperitoneum of adult patients, with a peak incidence between the third and the fourth decade 48. Microscopically smooth muscle cells are most often low grade and associated with a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates that tend to be so prominent to overshadow the neoplastic component. Less often a histiocytic population predominates sometimes assuming a xanthomatous appearance. Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma seems to behave less aggressively than ordinary leiomyosarcoma however follow-up data are still very limited.

SKELETAL MUSCLE TUMOURS

No major changes are reported within this subgroup (Tab. VII). A notable exception is however the recognition that rhabdomyosarcoma can occur primarily in bone as a spindle cell and epithelioid cell neoplasm (Fig. 4) that is most often associated with fusion of the TFCP2 gene with FUS or EWSR1 and expression of ALK (in absence of ALK gene rearrangement) 49-51. Recently an alternative MEIS1-NCOA2 gene fusion has been reported 52. With the bias determined by their extreme rarity, the clinical behaviour appears to be very aggressive.

Table VII.

Skeletal muscle tumours.

| Benign |

| Rhabdomyoma |

| Malignant |

| Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Spindle cell / sclerosing rhabdomyosarcoma |

| Ectomesenchymoma |

Figure 4.

Intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma. In this example an epithelioid atypical neoplastic cell population predominates.

GASTROINTESTINAL STROMAL TUMOURS (GIST)

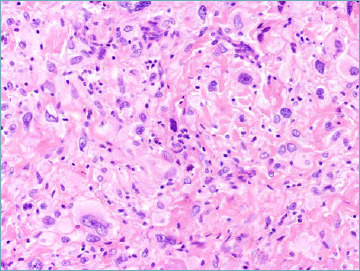

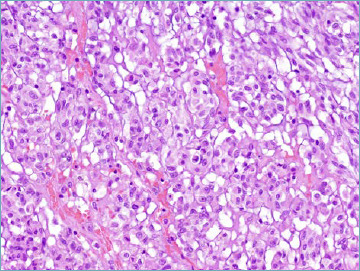

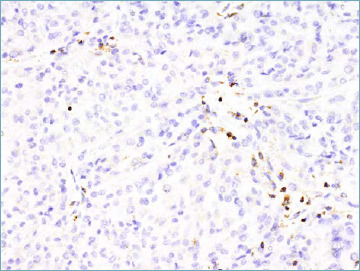

One major step forward is that in the 5th series GIST is covered by the same authors in both the gastrointestinal and soft tissue fascicles, therefore ensuring a more homogenous diagnostic approach (Tab. VIII). In comparison with previous editions SDH-deficient GISTs are now discussed in greater detail. This distinct subset (accounting for approximately 5 to 10% of all GIST) is characterised by occurrence in children and adolescents, with female predominance 53. Relatively often SDH-deficient GISTs feature a distinctive multinodular pattern of growth associated with predominantly epithelioid morphology (Fig. 5A). The presence of SDH subunit genes mutations is observed in approximately 60% of cases (SDHA mutations are the most frequently observed) and, whatever the subunit involved is predicted by immunohistochemical loss of SDHB expression 54 (Fig. 5B). In 40% of cases SDHC promoter methylation (epimutation) is detected. Importantly SDH-deficient GIST appears to be resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In this context the risk assessment schemes utilised for KIT/PDGFRA mutated GIST is not applicable.

Table VIII.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours.

| Benign |

| MicroGIST |

| Malignant |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumors |

Figure 5A.

SDH-deficient GIST. Most cases are predominantly composed of epithelioid cell with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Figure 5B.

SDH-deficient GIST. The neoplastic cells show loss of staining for SDHB. Endothelial cells and lymphocytes represent the internal positive control.

CHONDRO-OSSEOUS TUMOURS

As exemplified in Table IX no new entries have been included. Both soft tissue chondroma and extraskeletal osteosarcoma represent exceedingly rare lesions. In approximately 50% of soft tissue chondroma FN1 gene rearrangements have been documented. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma remains an extremely aggressive neoplasms of elderly patients, often presenting with lung metastases at diagnosis.

Table IX.

Chondro-osseous tumours.

| Benign |

| Chondroma |

| Malignant |

| Osteosarcoma, extraskeletal |

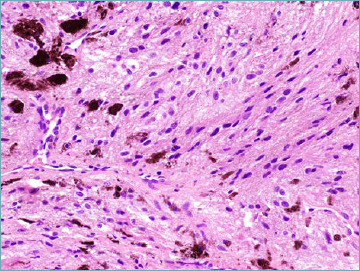

PERIPHERAL NERVE SHEATH TUMOURS

The single major change introduced by the 2020 WHO classification is the recognition that so called melanotic schwannoma actually represents a clinically aggressive neoplasm (not belonging anymore to the intermediate category) being consequently relabelled as malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumour 55 (Tab. X). It most often occurs in a midline location within spinal and autonomic nerves of adult patients. A subset of lesions occurs in context of Carney complex. Microscopically is composed by spindle and epithelioid neoplastic cells organised in sheets and short fascicles. Cytoplasm vary from eosinophilic to amphophilic and contain round nuclei often featuring pseudoinclusions. The amount of pigment varies from focal to massively abundant (Fig. 6). Approximately half of cases contain psammoma bodies. Presence of necrosis and mitotic activity can be observed that however does not seem to predict outcome. Immunohisochemically, malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumour express S100, SOX10, HMB45 and MelanA. Pathogenetically, the vast majority of tumour are associated with inactivating mutation of the PRKAR1A gene leading to the loss of expression of the protein thereof 56. It has become evident that this lesion is associated with high risk of both local recurrence and metastatic spread, even many years from resection of the primary lesion. As a consequence, long term follow-up is strongly advised.

Table X.

Peripheral nerve sheath tumours.

| Benign |

| Schwannoma |

| Neurofibroma |

| Perineurioma |

| Granular cell tumour |

| Nerve sheath myxoma |

| Solitary circumscribed neuroma |

| Meningioma |

| Hybrid nerve sheath tumour |

| Malignant |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour |

| Melanotic malignant nerve sheath tumour |

| Granular cell tumour, malignant |

| Perineurioma, malignant |

Figure 6.

Malignant melanotic nerve sheath tumour. Spindle cell set in a fibrous stroma with heavy melanin pigment deposition is seen.

TUMOURS OF UNCERTAIN DIFFERENTIATION

The inclusion within this tumour category (Tab. XI) as an emerging entity of the category of NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasm (excluding infantile fibrosarcoma that represent a distinct clinicopathologic entity defined molecularly by the presence of NTRK3-ETV6 fusion gene), represents one of the most relevant innovation. The availability of a new class of drugs characterised by NTRK inhibitory action (Entrectinib and Larotrectinib) has in fact generated a remarkable interest towards any neoplasm harbouring a rearrangement of any of NTRK 1, 2 and 3 genes 57.

Table XI.

Tumors of uncertain differentiation.

| Benign |

| Myxoma (cellular myxoma) |

| Deep (aggressive) angiomyxoma |

| Pleomorphic hyalinising angiectatic tumour |

| Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour |

| Perivascular epithelioid tumour, benign |

| Angiomyolipoma |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) |

| Haemosiderotic fibrolipomatous tumour |

| Angiomyolipoma, epithelioid |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasising) |

| Atypical fibroxanthoma |

| Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma |

| Ossifying fibromyxoid tumour |

| Myoepithelioma |

| Malignant |

| Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumour, malignant |

| NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasm (emerging) |

| Synovial sarcoma |

| Epithelioid sarcoma: proximal and classic variant |

| Alveolar soft part sarcoma |

| Clear cell sarcoma |

| Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma |

| Desmoplastic small round cell tumour |

| Rhabdoid tumour |

| Perivascular epithelioid tumour, malignant |

| Intimal sarcoma |

| Ossifying fibromyxoid tumour, malignant |

| Myoepithelial carcinoma |

| Undifferentiated sarcoma |

| Spindle cell sarcoma, undifferentiated |

| Pleomorphic sarcoma, undifferentiated |

| Round cell sarcoma, undifferentiated |

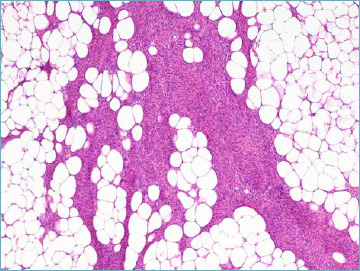

NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasms appear to form a morphological spectrum that occurs most often in the superficial or deep soft tissue of the extremities of children and adolescents. The molecular pathogenesis is most often related to rearrangement of the NTRK1 gene with a variety of partners. More rarely NTRK2 and NTRK3 aberrations have been detected. At one end of this spectrum is the so-called lipofibromatosis-like neural tumour (LLNT), composed of monomorphic spindle cells co-expressing S100 and CD34, featuring a highly infiltrative pattern within subcutaneous fat, therefore closely resembling lipofibromatosis (Fig. 7A). From the clinical standpoint LLNT can recur locally but seems not to possess metastatic potential 58.

Figure 7A.

Lipofibromatosis-like neural tumour. Spindle cells infiltrate adipose tissue resembling lipofibromatosis.

A second subset of cases features a predominantly solid pattern of growth, and is composed of a cellular proliferation of uniform spindle cells that in higher grade examples resemble malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours and therefore labelled as NTRK- rearranged neoplasm resembling peripheral nerve sheath tumours (Fig. 7B). Prominent deposition of hyalinised collagen is often observed 59,60. Rarely, a myopericytoma-like architecture is detectable 61. Outcome seems to correlate with morphology. Lesions with high grade features tend to behave aggressively often featuring distant spread to the lungs. All these entities share the expression (that is not of course specific) of anti- pan-TRK antibodies. Hopefully, the accrual of more cases will allow in the future to better define the clinicopathologic boundaries of this group of lesions.

Figure 7B.

NTRK-positive tumor resembling peripheral nerve sheath tumour. A highly cellular spindle cell proliferation organised in fascicles is seen.

UNDIFFERENTIATED SMALL ROUND CELL SARCOMAS OF BONE AND SOFT TISSUES

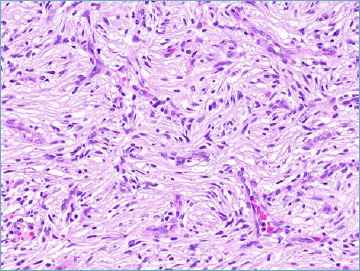

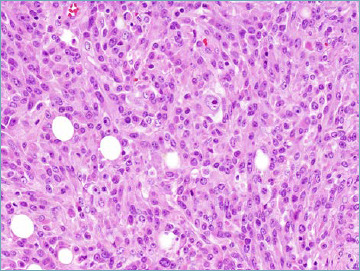

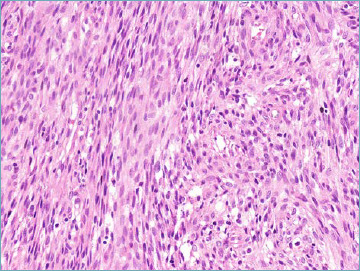

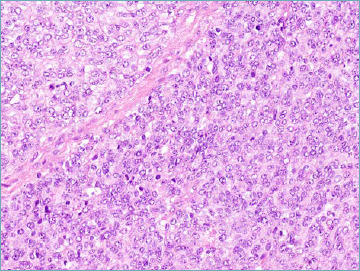

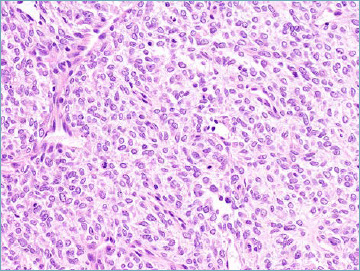

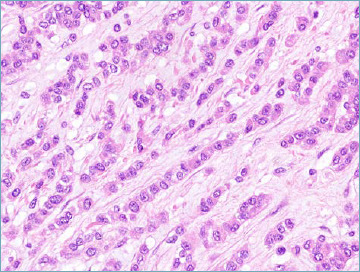

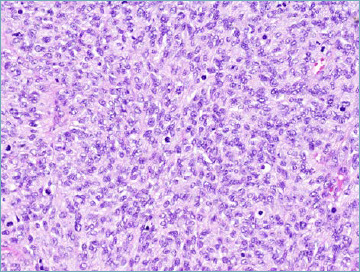

The creation of a separate chapter encompassing round cell sarcoma of soft tissue and bone also represents a major step forward of the 2020 WHO classification (Tab. XII). This new section contains not only the prototypical round cell sarcoma named Ewing’s sarcoma, but also three distinct subsets that differs from Ewing’s sarcoma clinically, pathologically and molecularly 49,62: 1. Round cell sarcomas with EWSR1 gene fusion with non-ETS family members 63-65, 2. CIC-rearranged sarcomas 66-68, and 3. BCOR-rearranged sarcomas 69. Interestingly, despite significant morphologic overlap, most of these entities tend to exhibit some morphologic features predictive of the underlying molecular alteration. If Ewing sarcoma represents the prototype of round cell sarcoma, CIC sarcomas always exhibits focal pleomorphism, and at times epithelioid morphology can predominate (Fig. 8A). BCOR sarcomas (despite being allocated to the round cell sarcoma family) more often tend to exhibit a spindled morphology (Fig. 8B). NFATC2 sarcoma may exhibit remarkable epithelioid features (Fig. 8C), and PATZ1 sarcomas are composed of a rather undifferentiated round to ovoid cell population (Fig. 8D), often characterised by the presence of a sclerotic background. The differential diagnosis for these tumours is rather broad, and among round cell sarcomas includes alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumour, poorly differentiated round cell synovial sarcoma, small cell osteosarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma. A combination of morphologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular findings allows accurate classification in most cases. A granular diagnostic approach to Ewing sarcoma and Ewing-like sarcomas is justified by significant differences in terms of both response to chemotherapy and overall survival 68,69. As all these entities are in part defined by specific fusion genes, a molecular diagnostic approach based on NGS technology should be preferred 8. In consideration of the extreme rarity of many of these tumour entities, referral to expert rare cancer centres or to rare cancer networks represents the best strategy in order to minimise diagnostic inaccuracy, and allow proper patient management.

Table XII.

Undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue.

| Ewing sarcoma |

| Round cell sarcoma with EWSR1-non-ETS fusions |

| CIC-rearranged sarcomas |

| Sarcoma with BCOR genetic alterations |

Figure 8A.

CIC-rearranged sarcoma. Highly atypical undifferentiated neoplastic cells are organised in a diffuse pattern of growth.

Figure 8B.

BCOR-rearranged sarcoma. Neoplastic cell population tends to assume a spindle morphology.

Figure 8C.

NFATC2-rearramged sarcoma. Striking epithelioid morphology characterises the majority of cases.

Figure 8D.

PATZ1-rearranged sarcoma. Neoplastic cells feature round to ovoid nuclei and are organised in a diffuse pattern of growth.

Standing Issues

DIAGNOSTIC ROLE OF MOLECULAR PATHOLOGY

The integration of morphology and genetics represents one of the major advances introduce by WHO classification since 2000, to the extent that the “blue Book” was labelled as “Pathology and Genetics” 17. In the last 20 years descriptions of genetic aberrations (particularly new fusion genes) have increased exponentially. Many of these genetic abnormalities are linked with specific histotypes (i.e. MDM2 gene amplification and well differentiated/liposarcoma; SYT gene rearrangement in synovial sarcoma etc.) whereas many others (particularly fusion genes) seem to represent non-driver (stochastic) molecular events the detection of which has been enhanced by extensive use of NGS-based molecular approaches 70. Moreover, some histotypes are currently defined on the basis of their genetics (i.e. NTRK, CIC and BCOR sarcomas). Whether molecular analysis should be mandatorily associated with conventional microscopic examination is still source of debate. The WHO expert panel has decided to report in the “blue book” all pertinent genetic aberrations not making them diagnostically obligational. Two main reasons are: 1. Accurate pathologic diagnosis can be reached (in expert hands) without the support of molecular diagnostics. 2. WHO classification is meant to be used globally, including those countries in which molecular pathology is not implemented. Both arguments are of course valid. There exists however one contradiction represented by the introduction of entities labelled based on “specific” fusion genes. In our opinion, it sounds for instance somewhat illogical to make a diagnosis of EWSR1-SMAD3 positive fibroblastic tumour in absence of a formal demonstration of the associated genetic aberration.

DEFINITION OF A TUMOUR ENTITY

An unavoidable consequence of using molecular genetics as the main driver for tumour classification is to generate a debate regarding the principles behind the definition of a tumour entity. Moreover, the advent of “precision oncology” has generated the (mis) concept that extensive molecular profiling of cancer is the only way to improve patients’ outcome 71. The underlying ambition would be the generation of a new taxonomy of human cancer based on molecular genetics, aimed to replace histology-based classifications. Certainly, molecular characterisation can allow to predict sensitivity to treatments, especially molecularly targeted therapies. In the sarcoma field, this has proved extremely effective with tyrosine kinase inhibition in GIST. The principle of precision oncology is however based on the concept that medical therapies should focus on the predictive molecular biomarker rather than on the histoype 72,73. This “histological agnosticism” has led for the first time to the approval of anticancer agents based solely on the availability of a molecular target. The prototypical example is in fact represented by neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase (NTRK) inhibitors, the concept being that a NTRK-inhibitor may be effective against different malignancies as long as they harbour a NTRK gene fusion 57. As discussed previously, the 2020 WHO classification has introduced an “emerging entity” named NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasm 19. This seems apparently a timely decision however it should be considered that several factors will necessarily influence the actual use of these new agents:

The clinical positioning of the drug that may vary based on the natural history of the cancer type.

The actual need for a medical therapy when the stage of the disease is considered.

The availability of alternative effective agents.

An NTRK-inhibitor will be used for instance as a last-line therapy in one malignancy and as a first-line therapy in another one. In other words, the regulatory approval of a drug may be histologically agnostic, but its clinical use will never be. Irrespective of its predictive power, a molecular biomarker aimed to select medical therapies should never become the key element to define a disease. In the case of NTRK rearranged spindle cell sarcomas one may suppose that these tumours are sensitive to the new NTRK-inhibitors, however their epidemiology, clinical presentation, natural history and prognosis seems to be extremely variable and somewhat unspecific. If the only common denominator, is the potential activity of a class of drugs, actually many other unrelated non-mesenchymal cancers will be sensitive to the same drugs. On the contrary, a time-honoured entity such as infantile fibrosarcoma, in addition to be pathogenetically related to a gene fusion involving NTRK3, clearly features epidemiological, clinical and pathologic characteristics which are highly specific. Its sensitivity to NTRK-inhibitors is just a complement to all that. Thus, while there is no reason to challenge the existence of a disease called infantile fibrosarcoma, one could for instance consider premature (this may change in the future as more data are collected) to consider NTRK-rearranged spindle cell neoplasm as a distinct nosological entity, and this may in principle apply to other “new” sarcoma entities. For these reasons, the concept that a new entity in the sarcoma field should never reflect just the mere presence of a predictive molecular biomarker has been recently proposed to the sarcoma community 74.

Conclusions

The publication of a new WHO classification represents a major step towards standardization of cancer diagnostics. In the case of rare diseases such as soft tissue tumours its value is even greater as it contributes significantly to improve diagnostic accuracy. Pathologic diagnosis of cancer represents the result of a complex integration of microscopic, immunophenotypic and molecular features and, with rare exceptions is the cornerstone of clinical decision making. WHO classification appears more and more as the field wherein the joint efforts of pathologists, geneticists and clinicians can translate novel findings into more rationale as well as more effective treatments.

Figures and tables

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

MS drafted the manuscript. EB selected the illustrations and drafted the tables. APTD edited the final version of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Sbaraglia M, Dei Tos AP. The pathology of soft tissue sarcomas. Radiol Med 2019;124:266-81. Epub 2018 Jun 12. PMID: 29948548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11547-018-0882-7 10.1007/s11547-018-0882-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kissin MW, Fisher C, Webb AJ, Westbury G. Value of fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of soft tissue tumours: a preliminary study on the excised specimen. Br J Surg 1987;74:479-80. PMID: 3607402. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.1800740616 10.1002/bjs.1800740616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray-Coquard I, Montesco MC, Coindre JM, et al. Sarcoma: concordance between initial diagnosis and centralized expert review in a population-based study within three European regions. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2442-9. Epub 2012 Feb 13. PMID: 22331640; PMCID: PMC3425368. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdr610 10.1093/annonc/mdr610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thway K, Wang J, Mubako T, Fisher C. Histopathological diagnostic discrepancies in soft tissue tumours referred to a specialist centre: reassessment in the era of ancillary molecular diagnosis. Sarcoma 2014;2014:686902. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/686902 10.1155/2014/686902 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frezza AM, Lee ATJ, Nizri E, et al. 2018 ESMO Sarcoma and GIST Symposium: ‘take-home messages’ in soft tissue sarcoma. ESMO Open 2018;3:e000390. PMID: 30018812; PMCID: PMC6045770. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000390 10.1136/esmoopen-2018-000390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gatta G, van der Zwan JM, Casali PG, et al. ; RARECARE working group. Rare cancers are not so rare: the rare cancer burden in Europe. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2493-511. Epub 2011 Oct 25. PMID: 22033323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.08.008 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuville A, Ranchère-Vince D, Dei Tos AP, et al. Impact of molecular analysis on the final sarcoma diagnosis: a study on 763 cases collected during a European epidemiological study. Am J Surg Pathol 2013;37:1259-68. PMID: 23774173. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828f51b9 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31828f51b9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racanelli D, Brenca M, Baldazzi D, et al. Next-generation sequencing approaches for the identification of pathognomonic fusion transcripts in sarcomas: the experience of the Italian ACC Sarcoma Working Group. Front Oncol 2020;10:489. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00489. Erratum in: Front Oncol 2020;10:944. PMID: 32351889; PMCID: PMC7175964. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00489. Erratum in: Front Oncol 2020;10:944. PMID: 32351889; PMCID: PMC7175964. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hostein I, Debiec-Rychter M, Olschwang S, et al. A quality control program for mutation detection in KIT and PDGFRA in gastrointestinal stromal tumours. J Gastroenterol 2011;46:586-94. Epub 2011 Feb 1. PMID: 21286759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-011-0375-0 10.1007/s00535-011-0375-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demetri GD, Blay JY, Casali PG. Advances and controversies in the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Future Oncol. 2017;13(1s):3-11. PMID: 27918199. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2016-0498 10.2217/fon-2016-0498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiusole B, Le Cesne A, Rastrelli M, et al. Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma: clinical and molecular characteristics and outcomes of patients treated at two institutions. Front Oncol 2020;10:828. PMID: 32612944; PMCID: PMC7308468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2020.00828 10.3389/fonc.2020.00828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sanfilippo R, Jones RL, Blay JY, et al. Role of chemotherapy, VEGFR inhibitors, and mTOR inhibitors in advanced perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComas). Clin Cancer Res 2019;25:5295-300. Epub 2019 Jun 19. PMID: 31217199. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0288 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-0288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanfilippo R, Fabbroni C, Fucà G, et al. Addition of antiestrogen treatment in patients with malignant PEComa progressing to mTOR Inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2020. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32605908. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1191 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gronchi A, Palmerini E, Quagliuolo V, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk soft tissue sarcomas: final results of a randomized trial from Italian (ISG), Spanish (GEIS), French (FSG), and Polish (PSG) Sarcoma Groups. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:2178-86. Epub 2020 May 18. PMID: 32421444. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.19.03289 10.1200/JCO.19.03289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldi GG, Brahmi M, Lo Vullo S, et al. The activity of chemotherapy in inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors: a multicenter, European retrospective case series analysis. Oncologist 2020. June 25. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32584482. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0352 10.1634/theoncologist.2020-0352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frezza AM, Assi T, Lo Vullo S, et al. Systemic treatments in MDM2 positive intimal sarcoma: a multicentre experience with anthracycline, gemcitabine, and pazopanib within the World Sarcoma Network. Cancer 2020;126:98-104. Epub 2019 Sep 19. PMID: 31536651. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32508 10.1002/cncr.32508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 3rd ed., Vol. 5. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fletcher CDM, Bridge JA, Pancras CW, et al., eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 4th ed., Vol. 5. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Soft tissue and bone tumours. Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. (WHO classification of tumours series, 5th ed. Vol. 3). https://publications.Iarc.fr/588 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sbaraglia M, Righi A, Gambarotti M, et al. Soft Tissue tumors rarely presenting primary in bone; diagnostic pitfalls. Surg Pathol Clin 2017;10:705-30. Epub 2017 Jun 29. PMID: 28797510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.path.2017.04.013 10.1016/j.path.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dei Tos AP, Mentzel T, Newman PL, et al. Spindle cell liposarcoma, a hitherto unrecognized variant of liposarcoma. Analysis of six cases. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:913-21. PMID: 8067512. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199409000-00006 10.1097/00000478-199409000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mariño-Enriquez A, Nascimento AF, Ligon AH, et al. Atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor: clinicopathologic characterization of 232 cases demonstrating a morphologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:234-44. PMID: 27879515. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000770 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creytens D, Mentzel T, Ferdinande L, et al. “Atypical” pleomorphic lipomatous tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular study of 21 cases, emphasizing its relationship to atypical spindle cell lipomatous tumor and suggesting a morphologic spectrum (atypical spindle cell/pleomorphic lipomatous tumor). Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:1443-55. PMID: 28877053. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000936 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alaggio R, Coffin CM, Weiss SW, et al. Liposarcomas in young patients: a study of 82 cases occurring in patients younger than 22 years of age. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:645-58. PMID: 19194281. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181963c9c 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181963c9c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dei Tos AP, Piccinin S, Doglioni C, et al. Molecular aberrations of the G1-S checkpoint in myxoid and round cell liposarcoma. Am J Pathol 1997;151:1531-9. PMID: 9403703; PMCID: PMC1858364. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dei Tos AP. Liposarcomas: diagnostic pitfalls and new insights. Histopathology 2014;64:38-52. Epub 2013 Dec 6. PMID: 24118009. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.12311 10.1111/his.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mariño-Enríquez A, Fletcher CD. Angiofibroma of soft tissue: clinicopathologic characterization of a distinctive benign fibrovascular neoplasm in a series of 37 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2012;36:500-8. PMID: 22301504. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823defbe 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31823defbe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter JM, Weiss SW, Linos K, et al. Superficial CD34-positive fibroblastic tumor: report of 18 cases of a distinctive low-grade mesenchymal neoplasm of intermediate (borderline) malignancy. Mod Pathol 2014;27:294-302. Epub 2013 Jul 26. PMID: 23887307. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.139 10.1038/modpathol.2013.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kao YC, Flucke U, Eijkelenboom A, et al. Novel EWSR1-SMAD3 gene fusions in a group of acral fibroblastic spindle cell neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:522-8. PMID: 29309308; PMCID: PMC5844807. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001002 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin Y, Möller E, Nord KH, et al. Fusion of the AHRR and NCOA2 genes through a recurrent translocation t(5;8)(p15;q13) in soft tissue angiofibroma results in upregulation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor target genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:510-20. Epub 2012 Feb 15. PMID: 22337624. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.21939 10.1002/gcc.21939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma: an analysis of 200 cases. Cancer 1978;41:2250-66. PMID: 207408. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197806)41:6<2250::aid-cncr2820410626>3.0.co;2-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fletcher CD. Pleomorphic malignant fibrous histiocytoma: fact or fiction? A critical reappraisal based on 159 tumors diagnosed as pleomorphic sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1992;16:213-28. PMID: 1317996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dei Tos AP. Classification of pleomorphic sarcomas: where are we now? Histopathology. 2006;48:51-62. PMID: 16359537. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02289.x 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02289.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Myxoid variant of malignant fibrous histiocytoma. Cancer 1977;39:1672-85. PMID: 192434. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0142(197704)39:4<1672::aid cncr2820390442>3.0.co;2-c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angervall L, Kindblom LG, Merck C. Myxofibrosarcoma. A study of 30 cases. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 1977;85A:127-40. PMID: 15396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mentzel T, Calonje E, Wadden C, et al. Myxofibrosarcoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 75 cases with emphasis on the low-grade variant. Am J Surg Pathol 1996;20:391-405 PMID: 8604805. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199604000-00001 10.1097/00000478-199604000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fabre-Guillevin E, Coindre JM, Somerhausen Nde S, et al. Retroperitoneal liposarcomas: follow-up analysis of dedifferentiation after clinicopathologic reexamination of 86 liposarcomas and malignant fibrous histiocytomas. Cancer 2006;106:2725-33. PMID: 16688768. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.21933 10.1002/cncr.21933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rossi S, Szuhai K, Ijszenga M, et al. EWSR1-CREB1 and EWSR1-ATF1 fusion genes in angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:7322-8. PMID: 18094413. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1744 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Righi A, Sbaraglia M, Gambarotti M, et al. Primary Vascular tumors of bone: a monoinstitutional morphologic and molecular analysis of 427 cases with emphasis on epithelioid variants. Am J Surg Pathol 2020;44:1192-1203. PMID: 32271190. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001487 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Montgomery E, Epstein JI. Anastomosing hemangioma of the genitourinary tract: a lesion mimicking angiosarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2009;33:1364-9. PMID: 19606014. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ad30a7 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ad30a7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lappa E, Drakos E. Anastomosing hemangioma: short review of a benign mimicker of angiosarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2020;144:240-244. Epub 2019 Apr 8. PMID: 30958692. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2018-0264-RS 10.5858/arpa.2018-0264-RS [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fletcher CD. The evolving classification of soft tissue tumours: an update based on the new WHO classification. Histopathology 2006;48:3-12. PMID: 16359532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02284.x 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.D’Amico FE, Ruffolo C, Romano M, et al. Rare neoplasm mimicking neuoroendocrine pancreatic tumor: a case report of solitary fibrous tumor with review of the literature. Anticancer Res 2017;37:3093-7. PMID: 28551649. https://doi.org/10.21873/anticanres.11665 10.21873/anticanres.11665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doyle LA, Vivero M, Fletcher CD, et al. Nuclear expression of STAT6 distinguishes solitary fibrous tumor from histologic mimics. Mod Pathol 2014;27:390-5. Epub 2013 Sep 13. PMID: 24030747. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.164 10.1038/modpathol.2013.164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vallat-Decouvelaere AV, Dry SM, Fletcher CD. Atypical and malignant solitary fibrous tumors in extrathoracic locations: evidence of their comparability to intra-thoracic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:1501-11. PMID: 9850176. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199812000-00007 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demicco EG, Griffin AM, Gladdy RA, et al. Comparison of published risk models for prediction of outcome in patients with extrameningeal solitary fibrous tumour. Histopathology. 2019;75:723-37. Epub 2019 Sep 5. PMID: 31206727. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13940 10.1111/his.13940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Magg T, Schober T, Walz C, et al. Epstein-Barr Virus+ smooth muscle tumors as manifestation of primary immunodeficiency disorders. Front Immunol 2018;9:368. PMID: 29535735; PMCID: PMC5835094. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00368 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arbajian E, Köster J, Vult von Steyern F, et al. Inflammatory leiomyosarcoma is a distinct tumor characterized by near-haploidization, few somatic mutations, and a primitive myogenic gene expression signature. Mod Pathol 2018;31:93-100. Epub 2017 Sep 8. PMID: 28884746. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2017.113 10.1038/modpathol.2017.113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watson S, Perrin V, Guillemot D, et al. Transcriptomic definition of molecular subgroups of small round cell sarcomas. J Pathol 2018;245:29-40. Epub 2018 Mar 30. PMID: 29431183. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.5053 10.1002/path.5053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chrisinger JSA, Wehrli B, Dickson BC, et al. Epithelioid and spindle cell rhabdomyosarcoma with FUS-TFCP2 or EWSR1-TFCP2 fusion: report of two cases. Virchows Arch 2020. June 19. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32556562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-020-02870-0 10.1007/s00428-020-02870-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Le Loarer F, Cleven AHG, Bouvier C, et al. A subset of epithelioid and spindle cell rhabdomyosarcomas is associated with TFCP2 fusions and common ALK upregulation. Mod Pathol 2020;33:404-19. Epub 2019 Aug 5. PMID: 31383960. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0323-8 10.1038/s41379-019-0323-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agaram NP, Zhang L, Sung YS, et al. Expanding the spectrum of intraosseous rhabdomyosarcoma: correlation between 2 distinct gene fusions and phenotype. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:695-702. PMID: 30720533; PMCID: PMC6613942. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001227 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gill AJ. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient neoplasia. Histopathology 2018;72:106-16. PMID: 29239034. https://doi.org/10.1111/his.13277 10.1111/his.13277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner AJ, Remillard SP, Zhang YX, et al. Loss of expression of SDHA predicts SDHA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol 2013;26:289-94. Epub 2012 Sep 7. PMID: 22955521. https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2012.153 10.1038/modpathol.2012.153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Torres-Mora J, Dry S, Li X, et al. Malignant melanotic schwannian tumor: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and gene expression profiling study of 40 cases, with a proposal for the reclassification of “melanotic schwannoma”. Am J Surg Pathol 2014;38:94-105. PMID: 24145644. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182a0a150 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182a0a150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang L, Zehir A, Sadowska J, et al. Consistent copy number changes and recurrent PRKAR1A mutations distinguish Melanotic Schwannomas from Melanomas: SNP-array and next generation sequencing analysis. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2015;54:463-71. Epub 2015 May 29. PMID: 26031761; PMCID: PMC6446921. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22254 10.1002/gcc.22254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Demetri GD, Antonescu CR, Bjerkehagen B, et al. Diagnosis and management of tropomyosin receptor kinase (TRK) fusion sarcomas: expert recommendations from the World Sarcoma Network. Ann Oncol 2020. September 3;S0923-7534(20)42297-5. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2232 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.08.2232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Agaram NP, Zhang L, Sung YS, et al. Recurrent NTRK1 gene fusions define a novel subset of locally aggressive lipofibromatosis-like neural tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:1407-16 PMID: 27259011; PMCID: PMC5023452. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000675 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suurmeijer AJH, Dickson BC, Swanson D, et al. A novel group of spindle cell tumors defined by S100 and CD34 co-expression shows recurrent fusions involving RAF1, BRAF, and NTRK1/2 genes. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2018;57:611-21. Epub 2018 Oct 1. PMID: 30276917; PMCID: PMC6746236. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22671 10.1002/gcc.22671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis JL, Lockwood CM, Stohr B, et al. Expanding the spectrum of pediatric NTRK-rearranged mesenchymal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:435-45. PMID: 30585824. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001203 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haller F, Knopf J, Ackermann A, et al. Paediatric and adult soft tissue sarcomas with NTRK1 gene fusions: a subset of spindle cell sarcomas unified by a prominent myopericytic/haemangiopericytic pattern. J Pathol 2016;238:700-10. PMID: 26863915. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.4701 10.1002/path.4701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sbaraglia M, Righi A, Gambarotti M, et al. Ewing sarcoma and Ewing-like tumors. Virchows Arch 2020;476:109-19. Epub 2019 Dec 4. PMID: 31802230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00428-019-02720-8 10.1007/s00428-019-02720-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang GY, Thomas DG, Davis JL, et al. EWSR1-NFATC2 Translocation-associated sarcoma clinicopathologic findings in a rare aggressive primary bone or soft tissue tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:1112-22. PMID: 30994538. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001260 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chougule A, Taylor MS, Nardi V, et al. Spindle and round cell sarcoma with EWSR1-PATZ1 gene fusion: a sarcoma with polyphenotypic differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 2019;43:220-8. PMID: 30379650; PMCID: PMC6590674. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000001183 10.1097/PAS.0000000000001183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bridge JA, Sumegi J, Druta M, et al. Clinical, pathological, and genomic features of EWSR1-PATZ1 fusion sarcoma. Mod Pathol 2019;32:1593-1604. Epub 2019 Jun 12. PMID: 31189996. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0301-1 10.1038/s41379-019-0301-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Italiano A, Sung YS, Zhang L, et al. High prevalence of CIC fusion with double-homeobox (DUX4) transcription factors in EWSR1-negative undifferentiated small blue round cell sarcomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2012;51:207-18. Epub 2011 Nov 10. PMID: 22072439; PMCID: PMC3404826. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.20945 10.1002/gcc.20945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gambarotti M, Benini S, Gamberi G, et al. CIC-DUX4 fusion-positive round-cell sarcomas of soft tissue and bone: a single-institution morphological and molecular analysis of seven cases. Histopathology 2016;69:624-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antonescu CR, Owosho AA, Zhang L, et al. Sarcomas with CIC-rearrangements are a distinct pathologic entity with aggressive outcome: a clinicopathologic and molecular study of 115 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 2017;41:941-9. PMID: 28346326; PMCID: PMC5468475. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000846 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kao YC, Owosho AA, Sung YS, et al. BCOR-CCNB3 fusion positive sarcomas: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 36 cases with comparison to morphologic spectrum and clinical behavior of other round cell sarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2018;42:604-15. PMID: 29300189; PMCID: PMC5893395. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0000000000000965 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Johansson B, Mertens F, Schyman T, et al. Most gene fusions in cancer are stochastic events. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2019;58:607-11. Epub 2019 Mar 18. PMID: 30807681. https://doi.org/10.1002/gcc.22745 10.1002/gcc.22745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arnaud-Coffin P, Brahmi M, Vanacker H, et al. Therapeutic relevance of molecular screening program in patients with metastatic sarcoma: analysis from the ProfiLER 01 trial. Transl Oncol 2020;13:100870. Epub 2020 Sep 18. PMID: 32950930; PMCID: PMC7509228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100870 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seligson ND, Knepper TC, Ragg S, et al. Developing drugs for tissue-agnostic indications: a paradigm shift in leveraging cancer biology for precision medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2020. June 14. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.1946 10.1002/cpt.1946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pestana RC, Sen S, Hobbs BP, et al. Histology-agnostic drug development - considering issues beyond the tissue. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2020;17:555-68. Epub 2020 Jun 11. PMID: 32528101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-020-0384-0 10.1038/s41571-020-0384-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Casali PG, Dei Tos AP, Gronchi A. When does a new sarcoma exist? Clin Sarcoma Res 2020;10:19. PMID: 32944215; PMCID: PMC7488849. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13569-020-00141-9. 10.1186/s13569-020-00141-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]