In 2019, recognizing the importance of quality in TB care, the Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases, launched a series on this topic [1]. The series included 19 published papers [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], and covered a diverse range of topics. The entire series is open access and available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/journal-of-clinical-tuberculosis-and-other-mycobacterial-diseases/special-issue/10JL8LN0VVT.

In this concluding article, we cover the key messages from papers in the series. We also outline some strategies for improving quality of TB care. Given the Covid-19 pandemic and its negative impact on TB services, the topic of quality of TB care has become even more pertinent.

1. Impact of Covid-19 pandemic on TB services

Progress in TB control was stalling, even before the Covid-19 pandemic. The 2020 Global TB report shows little change since the previous year [21]. Nearly 1.4 million people died from TB in 2019. Of the estimated 10 million people who developed TB that year, some 3 million were either not diagnosed, or were not officially reported to national authorities.

Progress towards SDG, End TB and UN High Level TB meeting targets is lagging. For example, while the target for TB preventive therapy is 30 million by 2022, only 6.3 million people have been treated during 2018 and 2019. While the target for funding TB care and prevention is $13 billion annually, only $6.5 billion were raised during 2020.

As predicted, the Covid-19 pandemic is making things worse. In September, several civil society organizations working on TB released the results of a large survey done to document the impact of the pandemic on TB care, research and funding [22]. Around the world, policy and program officers reported significant drops in TB notification. Over 70% of healthcare workers and advocates reported a decrease in the number of people coming to health facilities for TB testing. In Kenya, 50% of people with TB reported having trouble finding transport to care and in India, 36% of people with TB reported health facilities they normally visit closed.

The 2020 Global TB Report shows big reductions in TB notifications. The data show 25–30% reductions in TB notifications reported in 3 high burden countries – India, Indonesia, the Philippines – between January and June 2020 compared to the same 6-month period in 2019. TB services are similarly disrupted in many countries, and the disruptions extend over several months, rather than just weeks.

In India, the world’s highest burden country, TB services are seriously disrupted, and the disruptions extend over several months, rather than just weeks [23]. India is dealing with a large-scale syndemic of TB and Covid-19.

A model by WHO [21] suggests that the global number of TB deaths could increase by around 0.2–0.4 million in 2020 alone, if health services are disrupted to the extent that the number of people with TB who are detected and treated falls by 25–50% over a period of 3 months.

The first pressing priority is to catch-up on all the missed patients and offer them TB treatment, in both public and private health sectors. It is also critical to ensure that everyone on TB therapy is adequately supported to complete the full duration of treatment. In this context, the key messages in the 19 articles in our series are highly relevant.

2. Key messages from the articles in the series

Table 1 attempts to summarize the key messages in the 19 articles in the series. The articles clearly demonstrate that poor quality of TB care is a major issue in all subgroups (adults, children), in all forms of TB (childhood, latent and DR-TB), and in a variety of countries and settings [2], [3], [5], [10], [12], [15]. Standardized patient (SP) studies in 4 high-burden countries showed that few patients were offered appropriate diagnostic tests but many were offered empirical therapies, including broad-spectrum antibiotics and steroids [2]. Several articles described the so-called “know-do” gap in which healthcare workers can describe best practices in theory but don’t necessarily implement them in practice [2], [4]. Other articles highlighted the importance of high-quality health systems (as part of universal health coverage [UHC]) in improving the quality of TB care, arguing for a shift in focus from the quality of individual providers to the strength of the health system at every level of care in both public and private sectors [5], [6], [8], [11], [14], [18]. The series also highlights the importance of the private health sector in many high TB burden countries, and the importance of engaging private providers to improve quality of TB care [13], [20].

Table 1.

Key messages from the articles in the series on quality of care.

| Focus (reference) | Authors | Abstract |

|---|---|---|

| Lessons on quality of TB diagnosis from standardized patients [2] | Benjamin Daniels, Ada Kwan, Madhukar Pai, Jishnu Das | Standardized patient (SP) studies in India, China, South Africa and Kenya show that in general quality of TB care is low: relatively few SPs were offered appropriate diagnostic tests but 83% of interactions resulted in prescription of medication, frequently inappropriate broad-spectrum antibiotics, fluoroquinolones and steroids |

| Quality of drug-resistant tuberculosis care: Gaps and solutions [3] | Zarir Udwadia, Jennifer Furin | There is a quality crisis in the field of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) care. DR-TB care is unsafe, inequitable, not patient-centred, and ineffective. The paper posits strategies to improve quality of care and advocates for a human-rights based approach to DR-TB care |

| In the eye of the multiple beholders: Qualitative research perspectives on studying and encouraging quality of TB care in India [4] | Andrew McDowell, Nora Engel, Amrita Daftary | Three qualitative case studies on TB diagnosis in India. (1) “Know-do” gap: GPs know best practices but don’t implement them. (2) Quality of care is limited by health system issues, even with easy-to-use diagnostics. (3) Patients in private pharmacies expect to receive tangible products. Pharmacists can “dispense” free vouchers for TB screening tests |

| Measuring and improving the quality of tuberculosis care: A framework and implications from the Lancet Global Health Commission [5] | Catherine Arsenault, Sanam Roder-DeWan, Margaret E. Kruk | Expanding diagnosis and treatment coverage alone will not create a TB-free world; high-quality health systems are essential. Efforts should focus on governing for quality, redesigning service delivery, transforming the health workforce and igniting demand for quality TB services |

| Implementing quality improvement in tuberculosis programming: Lessons learned from the global HIV response [6] | Daniel J. Ikeda, Apollo Basenero, Joseph Murungu, Margareth Jasmin, … Bruce D. Agins | Lessons learned from successful QI programs for HIV can guide improvements in TB care quality. QI programs should be NTP-coordinated. NTPs should develop comprehensive frameworks for QI capacity building, specifying curricula and standards for training at all health system levels in both public and private sectors, with scalability planned from the outset |

| Quality of TB services assessment: The unique contribution of patient and provider perspectives in identifying and addressing gaps in the quality of TB services [7] | Charlotte Colvin, Gretchen De Silva, Celine Garfin, Soumya Alva, … Jeanne Chauffour | The quality of TB services assessment (QTSA) aims to identify gaps in TB services and prioritize ways to improve care. A recent QTSA in the Philippines showed that providers report having counselled patients on TB more than patients report having received the information |

| The high-quality health system ‘revolution’: Re-imagining tuberculosis infection prevention and control [8] | Helene-Mari van der Westhuizen, Ruvandhi R. Nathavitharana, Clio Pillay, Ingrid Schoeman, Rodney Ehrlich | TB infection prevention and control (IPC) implementation should be linked with health system strengthening, moving it from the silo of NTPs, with IPC viewed as a system-wide goal rather than the responsibility of individual healthcare workers. Patient experience should be added to the definition of high-quality care |

| Quality of life with tuberculosis [9] | Ashutosh N. Aggarwal | Diminished capacity to work, social stigmatization, and psychological issues worsen quality of life (QOL) in TB patients. Governments and program managers need to step up socio-cultural reforms, health education, and additional support to patients to counter impairment in QOL |

| Quality of TB care among people living with HIV: Gaps and solutions [10] | Kogieleum Naidoo, Santhanalakshmi Gengiah, Satvinder Singh, Jonathan Stillo, Nesri Padayatchi | Gaps within HIV-TB care cascades must be systematically analysed. HIV-infected patients often present asymptomatically with TB and are under-evaluated with routinely available diagnostics. HIV-TB patients can have poor treatment outcomes due to unmanageable side effects of concomitant TB therapy and ART and the financial expense of multiple health visits |

| Closing gaps in the tuberculosis care cascade: an action-oriented research agenda [11] | Ramnath Subbaraman, Tulip Jhaveri, Ruvandhi R. Nathavitharana | Many people with active TB suffer poor outcomes at critical points in the health system, highlighting poor quality of TB care. The proposed research agenda asks: 1) Who is falling out of the TB care cascade?, 2) Why are patients falling out of the cascade?, and 3) What interventions are needed to reduce gaps in the care cascade? |

| Quality matters: Redefining child TB care with an emphasis on quality [12] | Farhana Amanullah, Jason Michael Bacha, Lucia Gonzalez Fernandez, Anna Maria Mandalakas | Child TB often presents like non-TB pneumonia or with difficult-to-diagnose extrapulmonary TB. Bacteriological confirmation is challenging. Children are rarely included in Phase 3 trials so have delayed access to new medications. Child TB cascade data is rarely available. The authors present a framework to improve the quality of child TB care |

| Quality of tuberculosis care by pharmacies in low- and middle-income countries: Gaps and opportunities [13] | Rosalind Miller, Catherine Goodman | The quality of pharmaceutical TB care has historically been poor. Interventions should expand beyond case detection to improve counselling of patients and appropriate medicine sales. Key areas for attention include pharmacy-specific global guidelines and the regulatory environment |

| Implementation science to improve the quality of tuberculosis diagnostic services in Uganda [14] | Adithya Cattamanchi, Christopher A. Berger, Priya B. Shete, Stavia Turyahabwe, … Achilles Katamba | System-level barriers lower the quality of care in Uganda, despite Xpert availability. Only 20% of patients with presumed TB received Xpert testing and nearly half with positive Xpert results were not rapidly linked to treatment. The authors conclude that Xpert scale-up should be accompanied by health system cointerventions to facilitate effective implementation |

| Identifying gaps in the quality of latent tuberculosis infection care [15] | Hannah Alsdurf, Dick Menzies | Quality care for LTBI must address key challenges including low prioritization of LTBI, provider knowledge gaps about testing and treatment, and patient concerns about side effects of preventive treatment. TB programmes need to ensure that these issues are addressed in a patient-centred manner |

| User experience and patient satisfaction with tuberculosis care in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review [16] | Danielle Cazabon, Tripti Pande, Paulami Sen, Amrita Daftary, … Madhukar Pai | Most patients reported high satisfaction, despite widespread evidence of low-quality TB care. This could be due to acquiescence response bias, low expectations or because patients fear loss of services if they express dissatisfaction. The authors note the lack of standardized tools for measuring patient satisfaction and recommend their development. |

| Tuberculosis deaths are predictable and preventable: Comprehensive assessment and clinical care is the key [17] | Anurag Bhargava, Madhavi Bhargava | Comprehensive assessment and clinical care are required to reduce TB morbidity and mortality. TB programs need to define criteria for inpatient care referral, address the paucity of hospital beds, and develop and implement guidelines for the clinical management of seriously ill patients with co-morbidities |

| Improving quality is necessary to building a TB-free world: Lancet Commission on Tuberculosis [18] | Michael J.A. Reid, Eric Goosby | The Lancet Commission on TB states that strategies for improving quality must be hard-wired into the organization of NTPs. It calls for implementation research to understand how to improve care cascades, highlights the compelling economic rationale for ending TB and describes addressing TB as a core component in achieving Universal Health Coverage |

| What quality of care means to tuberculosis survivors [19] | Chapal Mehra, Debshree Lokhande, Deepti Chavan, Saurabh Rane | When high quality care is defined without patients’ perspectives, their needs and expectations are not addressed. High quality care for TB-affected patients is affordable, easily available and accessible, delivered efficiently, and provided in a dignified, empathetic and stigma-free manner |

| Quality of tuberculosis care in the private health sector [20] | Guy Stallworthy, Hannah Monica Dias, Madhukar Pai | In many high TB burden countries, the private healthcare sector manages a large share of all patients. However, quality of TB care in the private sector falls short of international standards in many places and urgently needs improvement |

3. How can we improve quality of care?

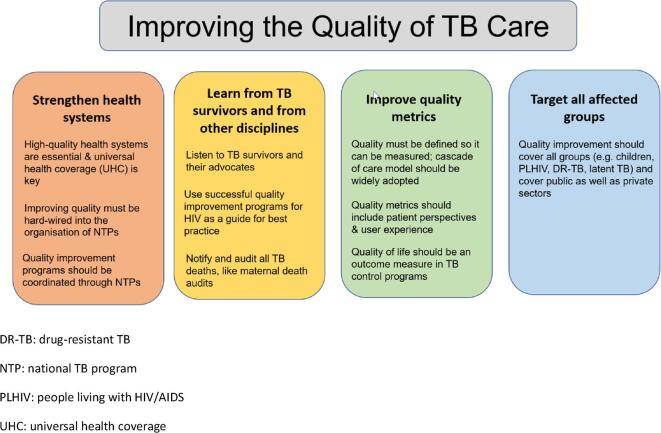

In addition to pointing out key gaps in care quality, some of the articles outline several potential solutions (Fig. 1 provides a high-level summary). A clear consensus is that improving the quality of TB care cannot be accomplished in a vacuum – it requires UHC and approaches that target the foundational strength of robust health systems [5], [6], [8], [11], [14], [18]. Quality in TB care needs to be better defined so it can be measured [5], [11], and it must be centered on patients’ perspectives to ensure that their needs and expectations are addressed [19]. Efforts to improve quality of TB care can be designed with lessons learned from other disciplines as a guide [6]. Promising approaches proposed in these articles included using existing tools and approaches for quality improvement [7], [14] and pursuing a research agenda that investigates reasons for losses at each stage of the TB care cascade [11].

Fig. 1.

Strategies to improve quality of TB care. DR-TB: drug-resistant TB. NTP: national TB program. PLHIV: people living with HIV/AIDS. UHC: universal health coverage.

When the series was launched in 2019, we had hoped it would result in a robust and sustained conversation about quality TB care, a topic that has heretofore been woefully neglected. At the start of 2021, we find ourselves in a crisis, where the TB epidemic has worsened because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Given the massive setback to progress in reaching any of the TB targets, it's time for the TB community to leverage Covid-19 innovations and systems (e.g. home-based and tele-health care, rapid and easy access to testing, digital adherence tools, real-time data tracking, sick pay and social benefits) to improve TB care and get back on track [24]. In fact, there cannot be a more opportune moment for the TB community to leverage Covid-19 innovations to reimagine TB care, and make universal health coverage a reality.

Ethical statement

The manuscript is an editorial with no original data. Ethics approval is not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Pai M., Temesgen Z. Quality: the missing ingredient in TB care and control. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;14:12–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels B., Kwan A., Pai M., Das J. Lessons on the quality of tuberculosis diagnosis from standardized patients in China, India, Kenya, and South Africa. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;16:100109. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udwadia Z., Furin J. Quality of drug-resistant tuberculosis care: Gaps and solutions. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;16:100101. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDowell A., Engel N., Daftary A. In the eye of the multiple beholders: qualitative research perspectives on studying and encouraging quality of TB care in India. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;16:100111. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arsenault C., Roder-DeWan S., Kruk M.E. Measuring and improving the quality of tuberculosis care: a framework and implications from the Lancet Global Health Commission. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;16:100112. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda D.J., Basenero A., Murungu J., Jasmin M., Inimah M., Agins B.D. Implementing quality improvement in tuberculosis programming: lessons learned from the global HIV response. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100116. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colvin C., De Silva G., Garfin C., Alva S., Cloutier S., Gaviola D. Quality of TB services assessment: the unique contribution of patient and provider perspectives in identifying and addressing gaps in the quality of TB services. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100117. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Westhuizen H.-M., Nathavitharana R.R., Pillay C., Schoeman I., Ehrlich R. The high-quality health system ‘revolution’: re-imagining tuberculosis infection prevention and control. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100118. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aggarwal A.N. Quality of life with tuberculosis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100121. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naidoo K., Gengiah S., Singh S., Stillo J., Padayatchi N. Quality of TB care among people living with HIV: gaps and solutions. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100122. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subbaraman R., Jhaveri T., Nathavitharana R.R. Closing gaps in the tuberculosis care cascade: an action-oriented research agenda. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100144. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amanullah F., Bacha J.M., Fernandez L.G., Mandalakas A.M. Quality matters: redefining child TB care with an emphasis on quality. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2019;17:100130. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller R., Goodman C. Quality of tuberculosis care by pharmacies in low- and middle-income countries: gaps and opportunities. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;18:100135. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cattamanchi A., Berger C.A., Shete P.B., Turyahabwe S., Joloba M., Moore D.AJ. Implementation science to improve the quality of tuberculosis diagnostic services in Uganda. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;18:100136. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2019.100136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hannah A., Dick M. Identifying gaps in the quality of latent tuberculosis infection care. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;18:100142. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cazabon D., Pande T., Sen P., Daftary A., Arsenault C., Bhatnagar H. User experience and patient satisfaction with tuberculosis care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100154. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhargava A., Bhargava M. Tuberculosis deaths are predictable and preventable: Comprehensive assessment and clinical care is the key. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100155. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid M.J.A., Goosby E. Improving quality is necessary to building a TB-free world: Lancet Commission on Tuberculosis. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100156. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehra C., Lokhande D., Chavan D., Rane S. What quality of care means to tuberculosis survivors. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;19:100157. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stallworthy G., Dias H.M., Pai M. Quality of tuberculosis care in the private health sector. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2020;20:100171. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2020.100171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2020; 2020 [Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/336069/9789240013131-eng.pdf] [Accessed 7 Dec 2020].

- 22.ACTION, Global Coalition of TB Activists, Global TB Caucus, KANCO, McGill International TB Centre, Results, Stop TB Partnership, TB People, TB PPM Learning Network, We are TB. The impact of COVID-19 on the TB epidemic: a community perspective; 2020 [Available from: https://spark.adobe.com/page/xJ7pygvhrIAqW/] [Accessed 13 Sept 2020].

- 23.Shrinivasan R., Rane S., Pai M. India’s syndemic of tuberculosis and COVID-19. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(11):e003979. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai M. It’s time to use Covid-19 innovations and systems to reimagine TB care; 2020 [Available from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/madhukarpai/2020/10/22/time-to-tap-covid-19-innovations--systems-to-reimagine-tb-care/?sh=180c0fd4494d] [Accessed 7 Dec 2020].