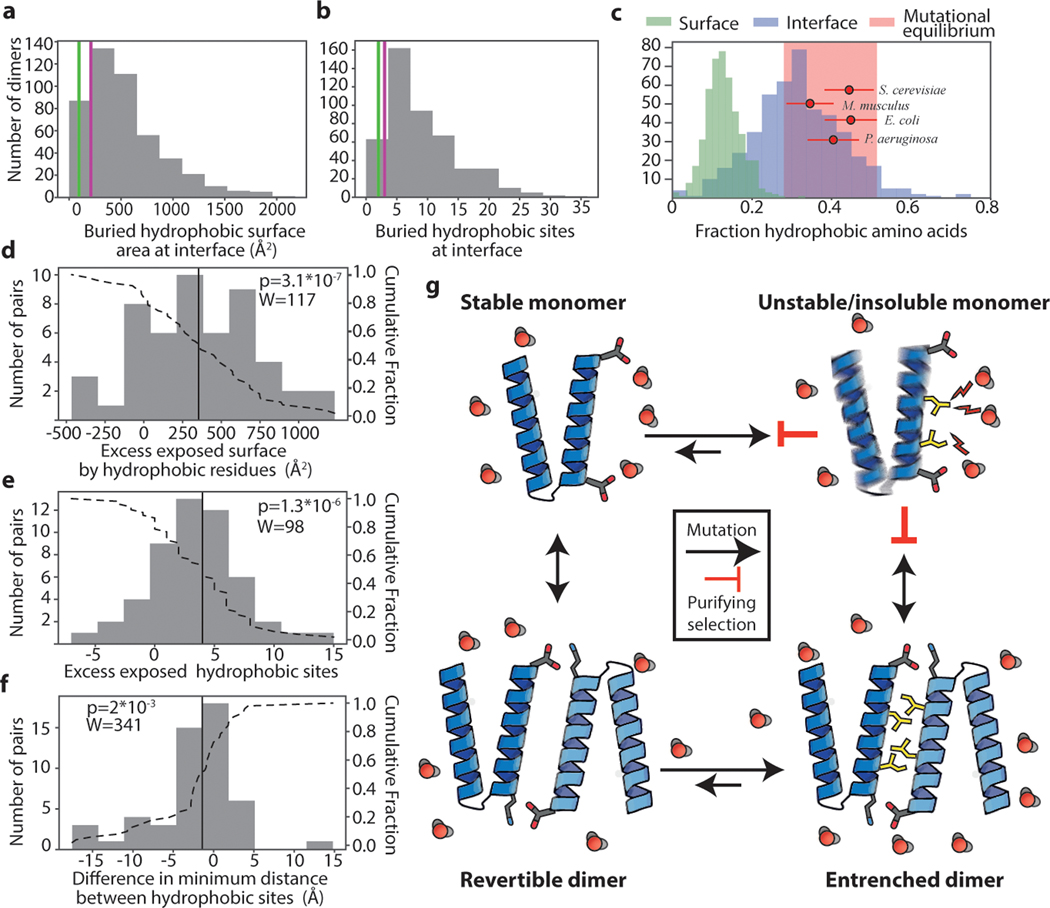

Figure 4: Pervasive hydrophobic entrenchment of molecular complexes.

Surface area (a) and count (b) of hydrophobic residues (amino acids CFILMVY) buried in dimer interfaces in a database of 466 non-redundant dimer structures. Purple and green lines, AncSR1-LBD and AncSR2-LBD interfaces. c) Dimer interfaces are more hydrophobic than is tolerated at surfaces and are close to the hydrophobicity expected by mutation alone. Histograms: Fraction of residues that are hydrophobic on solvent-exposed surfaces (green) or buried in dimer interfaces (blue). Red circles: expected fraction of hydrophobic amino acids from mutation alone, based on spectra from mutation accumulation data in 4 model organisms (see Extended Fig. 5C). Points and error bars, mean and SD from 100 replicates. Pink box, ±1 SD of the mean across all simulations. Red dots are distributed vertically for visual clarity. d-f) Histograms of the difference in surface properties between dimer subunits (when dissociated into monomers) and their monomeric homologs. Dotted line, cumulative fraction of pairs with greater difference. Solid line, median. d) Exposed surface area contributed by hydrophobic residues in dissociated dimer subunits minus that on monomeric homolog. e) Number of hydrophobic residues on surfaces of dimer subunits minus that on monomers. f) Difference in clustering of hydrophobic surface residues between dimer subunits and monomers, calculated as average surface distance from exposed hydrophobic residues to their nearest hydrophobic neighbor. n=51 independent monomer-dimer pairs; P-value and test-statistic W from two-tailed paired Wilcoxon test. g) Mechanism of the hydrophobic ratchet. In monomers, purifying selection counteracts mutational pressure towards increased surface hydrophobicity (yellow sticks), which would be deleterious because of increased propensity to aggregate and/or misfold. Once shielded from solvent (red) in dimers, hydrophobic mutations are free to accumulate in the buried interface. Purifying selection then preserves the complex.