Abstract

Background

Antibiotic resistance poses a significant threat to public health globally. Irrational utilization of antibiotics being one of the main reasons of antibiotic resistant. Children as a special group, there's more chance of getting infected. Although most of the infection is viral in etiology, antibiotics still are the most frequently prescribed medications for children. Therefore, high use of antibiotics among children raises concern about the appropriateness of antibiotic prescribing. This systematic review aims to measuring prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic utilization in children in China.

Methods

English and Chinese databases were searched to identify relevant studies evaluating the prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children (0-18 years), which were published between 2010 and July 2020. A Meta-analysis of prevalence was performed using random effect model. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and modified Jadad score was used to assess risk of bias of studies. In addition, we explored the risk factors of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children using qualitative analysis.

Results

Of 10,075 studies identified, 98 eligible studies were included after excluded duplicated studies. A total of 79 studies reported prevalence and 42 studies reported risk factors for antibiotic utilization in children. The overall prevalence of antibiotic utilization among outpatients and inpatients were 63.8% (35 studies, 95% confidence interval (CI): 55.1-72.4%), and 81.3% (41 studies, 95% CI: 77.3-85.2%), respectively. In addition, the overall prevalence of caregiver’s self-medicating of antibiotics for children at home was 37.8% (4 studies, 95% CI: 7.9-67.6%). The high prevalence of antibiotics was associated with multiple factors, while lacking of skills and knowledge in both physicians and caregivers was the most recognized risk factor, caregivers put pressure on physicians to get antibiotics and self-medicating with antibiotics at home for children also were the main factors attributed to this issue.

Conclusion

The prevalence of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children is heavy both in hospitals and home. It is important for government to develop more effective strategies to improve the irrational use of antibiotic, especially in rural setting.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12887-021-02706-z.

Keywords: Antibiotic, Prevalence, Risk factors, Children, China

Background

Antibiotic utilization is a major driver of antibiotic resistance, which is becoming a serious public health threat, imposing a direct effect on morbidity, mortality, and financial burden [1–3]. It was reported that China was the second largest consumer of antibiotics, and up to 57% of the increase in antibiotic consumption in the hospital sector among BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) was attributable to China [4]. In addition, China also has the most rapid growth rate of antibiotic resistance worldwide [5].

Antibiotics are the most widely prescribed therapy among all medications given to children [6, 7]. It was reported that the proportion of children with antibiotic prescription in the hospital settings was between 22% and 78 %[8–13], at the same time, inappropriate antibiotic prescription was the most common in pediatric clinical practice [14, 15]. About 50% of antibiotics were prescribed to children who were suffering from viral infection or non-infectious diseases, and the proportion of antibiotic prescriptions under 15 years old was three times than other ages [16, 17]. In addition, antibiotic abuse and misuse can also result in adverse events and drug toxicity due to children’s special physiological condition [18]. Children who prescribed antibiotics were more likely to have a subsequent acute bronchitis episode [19, 20]. China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS) showed that the proportions of gram-positive bacteria isolated from children and newborns was 45.5% in 2017, which were higher than that of the adults [21]. Children may have little or even no benefit from antibiotics [22], therefore, promotion of rational use of antibiotics and reduction in antibiotic resistance in children has become an urgent problem [23, 24]. To combat this problem, the Chinese government has launched relevant policies continuously since 2009. In 2009, to improve rational use of medicines, China government enacted the national essential medicines scheme, which aimed to curb the use of antibiotics by breaking the financial relation between drug prescription and physician income. Zero-mark-up policy was introduced to primary healthcare centers (PHCs) firstly in 2009, then followed by secondary hospitals in 2012, and expanded in tertiary hospitals in 2016 [25]. Hierarchical management was carried out for the clinical use of antibacterial drugs, which includes three levels: unrestricted use, restricted use and special use, according to safety, effect, drug resistance, and price in 2012 [26]. Since 2013, to improve antibiotic utilization in public hospitals, National Antibiotic Stewardship Program (NASP) was implemented nationwide which limits the proportion of outpatient antibiotic prescriptions and inpatient antibiotic prescriptions in hospitals to 20% and 60%, respectively [27]. National action plan combating antimicrobial resistance proposed to carry out health education on the rational use of antibiotics in primary and secondary schools [28].

Recently, the number of studies on the prevalence of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children has increased greatly, while sparse studies explored risk factors. Assessment of risk factors for antibiotic utilization in children may lead to a better understanding of the prevalence rates of antibiotics utilization and therefore leading to a more effective preventive strategy. In addition, most of the relevant studies were published in Chinese, with only a few in English language, which caused a lack of awareness of antibiotic utilization in China worldwide. There has not been an in-depth, up-to-date, and comparative analysis of the contemporary literature reporting the prevalence and risk factors for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children. In this study, we aimed to summarize the proportion of antibiotic usage among outpatients, inpatients, and self-medication, and investigate the major risk factors for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline [29]. The protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42020200172) (Table S1 in Additional file 1).

Search strategy

We searched three Chinese databases including China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chongqing VIP, and Wanfang Data, and three English databases including PubMed, Web of Science, and Embase between January 1, 2010 and July 10, 2020. Search terms were a combination of antibiotic, children, China, and prevalence (or risk factor). Then, references lists of the included studies were screened to complement our database searches. The detailed search strategies were presented in Table S2 Additional file 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) studies published in English or Chinese language; (2) publication date was between January 1, 2010 and July 10, 2020; (3) original studies using any study designs, such as observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional) or randomized studies; (4) reports on children (≤18 years old); (5) reports in China; (6) reports on prevalence rates or risk factors for antibiotic utilization. In order to update the analysis reflecting current patterns and practice guidelines, we excluded studies published before 2010. Children with special diseases (e.g. cancer, leukemia) were excluded as well. For randomized studies, we only included data of baseline or control group. Two reviewers (XY and GS) independently estimated the titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies using the above eligibility criteria, then, full texts were examined. Any discrepancies were resolved by the third reviewer (XM).

Data extraction

A pre-designed standardized extraction form was used to record the characteristics of each study including first author, publication year, study period, study design, geographical regions, study setting (rural: “rural” refer to place where laborers mainly engaged in agricultural production; urban: “urban” or “city” are cities which are officially administered at the national level as cities [30]), hospital levels (Level 1 hospital: primary hospitals or health institutions offer preventive, clinical treatment, health care and rehabilitation service in community. Generally, a primary hospital has 20-99 ward beds; Level 2 hospital: regional hospitals offer comprehensive medical and health services to multiple communities and offer medical training and research. Ward beds of Level 2 hospitals are between 100 and 499; Level 3 hospital: tertiary hospitals serve multiple regions, offer high-level and specialized medical services and are responsible for higher education and specific research. Each Level 3 hospital has over 500 ward beds [31]), sample size (number of children), age, number of children with antibiotics, number of children with one antibiotic, number of children with antibiotic combination, the top 3 types and utilization rates of antibiotics, and risk factors for antibiotic utilization.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, STATA version 15.0 was employed. We assessed heterogeneity of prevalence estimates using I2 index, which was categorized as low (0-25%), moderate (26-50%), and high (above 50% )[32].A random-effect meta-analysis was used to calculate the overall pooled prevalence of antibiotic utilization in children with 95% confidence interval (CI) due to high heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses for prevalence were performed with respect to study location (outpatient, inpatient, and self-medication at home), geographical region (eastern, central, and western), setting (urban and rural area), hospital levels (level 1, 2, 3), quantity of antibiotic use (alone or in combination), simple size, study period.

Study quality assessment

We assessed the included study quality using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) for observational studies [33]. We considered 11-item checklist for quality assessment, including source of investigation, inclusion and exclusion criteria, time period, consecutive of subjects, objectivity of indicators, reproducibility of indicators, reason for subject exclusions, confounding controlled, missing data handled, response rate and completeness of data collection, and results of follow-up. “No” or “Unclear” was scored “0”, and “Yes” was scored “1”. We considered studies that ≤ 3 scores as low quality, 4-7 scores as moderate quality, ≥8 scores as high quality. For randomized studies, we used modified Jadad score with classification criteria of high quality (6-7 scores), moderate quality (4-5 scores), and low quality (≤3), which included the generation of random sequences, randomization, blinding, follow-up. “No” was scored “0”, “unclear” was scored “1”, and “Yes” was scored “2” [34].

Results

Study selection

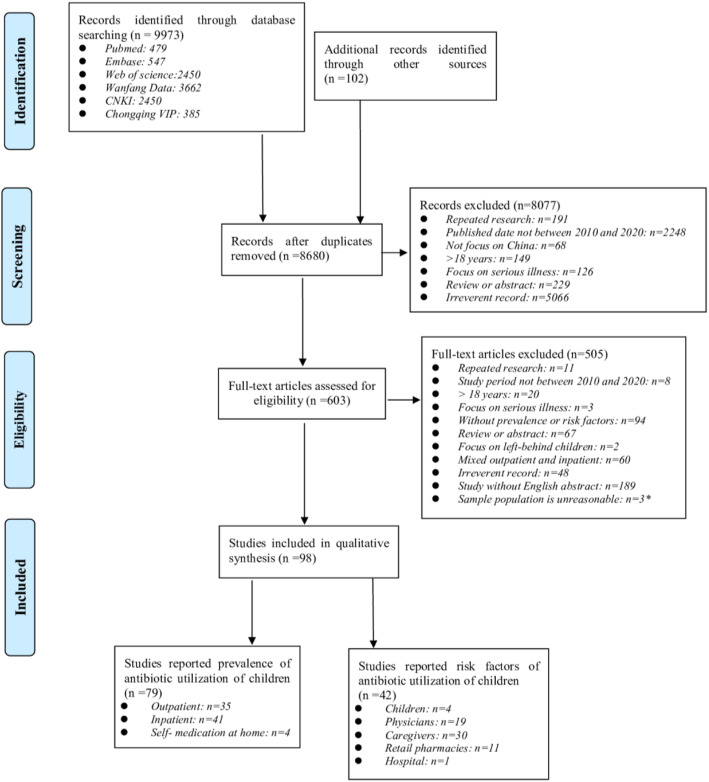

A total of 9,973 records were retrieved in the initial literature search, and additional 102 studies were identified through manual reference screens. After removing 1,395 duplicates, 8,680 studies were retrieved. Titles and abstracts screening resulting in 603 records for full-text evaluation. Finally, 98 records were included (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process. PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. CNKI: China National Knowledge Infrastructure. As all subjects in these 3 referenced articles received antibiotics (100% prevalence) as inpatients with bacterial infections, references [158–160] were excluded from the meta-analysis

Study characteristics and quality

Of the 98 eligible studies included in our review, 79 studies reported the prevalence of antibiotic utilization of children, including 34 studies on outpatient [35–68], 40 studies on inpatient [69–108] , and one study on both outpatient and inpatient [109]. Moreover, four studies reported the prevalence of self-medication antibiotic utilization at home [110–113]. The majority of the studies were retrospective observational studies (n=73), 6 studies were randomized controlled study, and majority of the studies were conducted in urban area (n=72), 7 studies conducted in rural area, and collected data from the Level 3 hospital (n=53). The study data were obtained from 22 provinces in mainland China, with the largest number of studies from Guangdong province (n=14), followed by Guangxi province (n=9), and Jiangsu province (n=7). A total of 49 studies collected data from the eastern economic zone, 17 studies from the western economic zone, 10 studies from the central economic zone, and three studies reported data from nationwide. The sample sizes ranged from 45 to 37211. In addition, 42 studies reported the risk factors for antibiotic utilization [20, 35, 36, 42, 45, 46, 52, 53, 58, 60, 67, 70, 76, 77, 83–85, 91, 92, 99, 110–131], of which, four studies focused on children, 19 studies focused on physicians, 30 studies reported from caregivers, 11 studies reported from retail pharmacies, and one study reported from hospital.(Table S3, Table S4, Table S5,Table S6 in Additional file 1).

Regarding the quality of included studies, for observational studies, 36 were with high quality and 56 were with moderate quality (Table S7 in Additional file 1). For randomized studies, 2 were with high quality, 4 were with moderate quality. (Table S8 in Additional file 1).

Prevalence of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children

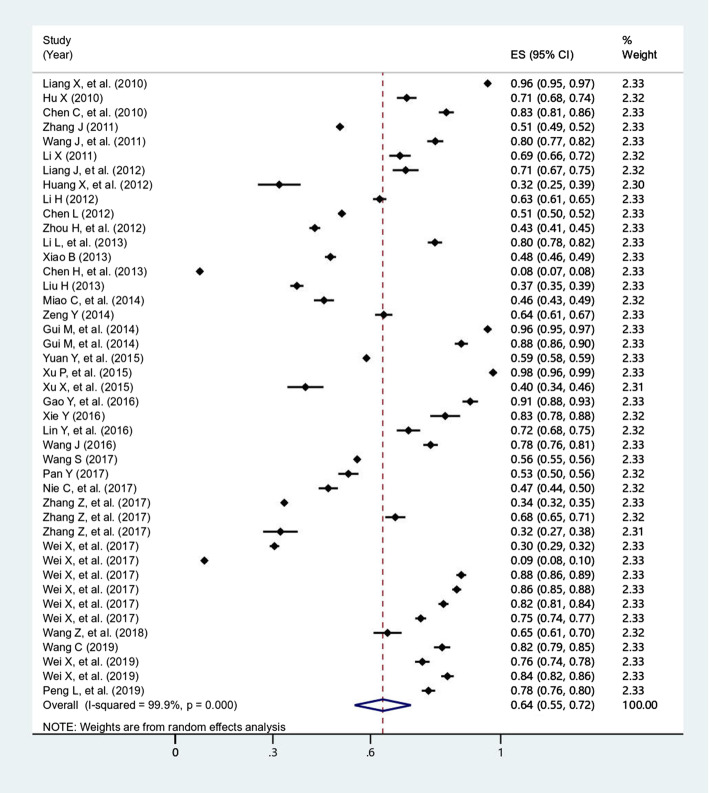

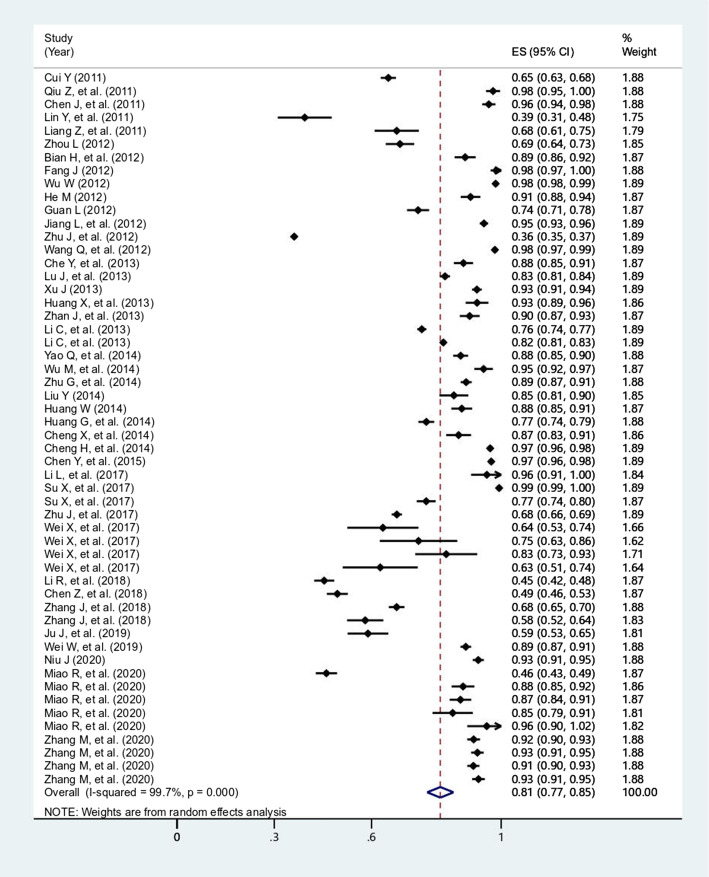

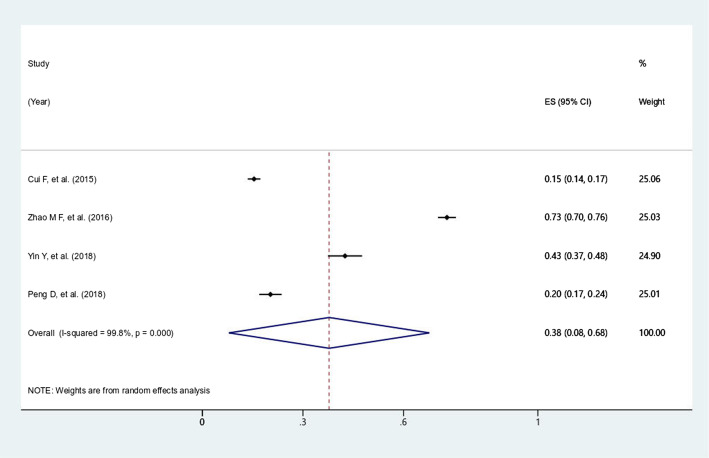

The overall prevalence of antibiotic utilization among outpatients and inpatients were 63.8% (95% CI: 55.1-72.4%, I2=99.9%, P<0.0001) (Fig. 2), and 81.3% (95% CI: 77.3-85.2%, I2=99.7%, P<0.0001) (Fig. 3), respectively. In addition, the overall prevalence of caregiver’s self-medicating of antibiotics for children at home was 37.8% (95% CI: 7.9-67.6%, I2=99.8%, P<0.0001) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the studies for prevalence of antibiotic utilization of outpatient

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of the studies for prevalence of antibiotic utilization of inpatient

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of the studies for prevalence of self-medicating at home

In the subgroup analyses, the prevalence of combined use of antibiotic was 25.2% among outpatients, and 40.2% among inpatients. The prevalence of antibiotic utilization in eastern, central, and western economic zone were 59.8%, 80.0%, 70.0%, respectively, for outpatients, and 81.0%, 78.9%, 80.5%, respectively, for inpatients. A higher prevalence antibiotic utilization was found in urban, with 64.1% and 81.7% for outpatients and inpatients respectively. In addition, prevalence of antibiotic utilization in level 1, 2, 3 hospital were 71.3%, 57.3% 64.0%, respectively, among outpatients, and 85.5% in level 2 hospital, 79.7% in level 3 hospital among inpatients. The percentage of antibiotic utilization fluctuated over time. In outpatient department, it declined between from 2010 to 2013, and in recent years, there has been an upward trend. For inpatient department, it increased from 2010 to 2013, then decrease from 2014-2017, and in recent years, there has been an upward trend. In outpatient department, the prevalence of antibiotic prescription prevalence was 57.7% for studies that included a sample of above 5000, and it was 64.8% for studies that included a sample of 5000 and less than 5000; in inpatient department, the prevalence of antibiotic prescription prevalence was 82.0% for studies that included a sample of above 1000, and it was 81.0% for studies that included a sample of 1000 and less than 1000 (Tables 1 and 2). In addition, we found that the most frequently used antibiotics were the third-generation cephalosporins, penicillins, and macrolides.

Table 1.

The prevalence of outpatient antibiotic utilization by antibiotic combination situation, economic zone, study setting, and hospital level.

| No. of studies (N) | n/N | Percentage (95% CI) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic combination situation (23) | |||

| Single use of antibiotic | 23 | 28467/36751 | 74.8 (68.2-81.3) |

| Combined use of antibiotic | 23 | 8284/36751 | 25.2 (18.7-31.8) |

| Economic zone (35) | |||

| Eastern | 24 | 74716/134667 | 59.8 (49.3-70.2) |

| Central | 4 | 4363/5244 | 80.0 (67.2-92.8) |

| Western | 7 | 5371/8540 | 70.0 (56.1-83.9) |

| Study setting (35) | |||

| Urban | 29 | 68961/118022 | 64.1 (54.4-73.8) |

| Rural | 6 | 15489/30429 | 63.1 (44.3-82.0) |

| Hospital level (35) | |||

| Level 3 | 19 | 61551/103670 | 64.0 (54.9-73.0) |

| Level 2 | 9 | 14214/33478 | 57.3 (37.1-77.6) |

| Level 1 | 8 | 8658/11303 | 71.3 (63.0-79.6) |

| Study period (33) | |||

| 2010-2011 | 15 | 66803/10992 | 68.5 (58.5-78.4) |

| 2012-2013 | 9 | 10607/22511 | 54.5 (35.0-74.1) |

| 2014-2015 | 12 | 16919/31424 | 65.2 (49.3-81.1) |

| 2016-2018 | 7 | 24033/39501 | 68.6 (59.0-78.1) |

| Sample size (35) | |||

| ≤5000 | 29 | 31832/55737 | 64.8 (53.5-76.1) |

| >5000 | 6 | 52618/92714 | 57.7 (39.3-76.0) |

N: Sample Size; n: Number of Children with Antibiotics; random-effect meta-analysis was used to calculate the overall pooled prevalence of antibiotic utilization. For studies reported different economic zone, study setting, hospital level, study period, sample size, we conducted meta- analysis more than once. Two studies study period was in 2009, therefore, there were 33 studies included subgroup analysis of study period.

Table 2.

The prevalence of inpatient antibiotic utilization by antibiotic combination situation, economic zone, study setting, and hospital level.

| No. of studies (N) | n/N | Percentage (95% CI) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic combination situation (31) | |||

| Single use of antibiotic | 31 | 14591/24236 | 59.8 (51.0-68.6) |

| Combined use of antibiotic | 31 | 9654/24236 | 40.2 (31.4-49.0) |

| Economic zone (41) | |||

| Eastern | 25 | 29815/36466 | 81.0 (77.3-84.7) |

| Central | 9 | 17707/22043 | 78.9 (71.9-86.0) |

| Western | 13 | 23205/32583 | 80.5 (71.2-89.8) |

| Study setting (41) | |||

| Urban | 40 | 4420/58190 | 81.7 (77.5-86.0) |

| Rural | 2 | 219/296 | 76.3 (62.3-90.3) |

| Hospital level (41) | |||

| Level 3 | 31 | 41159/54494 | 79.7 (74.7-84.6) |

| Level 2 | 11 | 3437/3947 | 85.5 (81.6-89.5) |

| Level 1 | 1 | 43/45 | 95.6(-) |

| Study period (35) | |||

| 2010-2011 | 22 | 30276/40486 | 82.9 (77.4-88.3) |

| 2012-2013 | 11 | 10748/12445 | 87.9 (84.3-91.4) |

| 2014-2015 | 8 | 9232/11193 | 82.9 (75.8-89.9) |

| 2016-2017 | 6 | 5801/ 8209 | 67.6 (57.1-78.1) |

| 2018-2019 | 4 | 3506/4351 | 82.3 (72.9-91.7) |

| Sample size (41) | |||

| ≤1000 | 27 | 12534/15777 | 81.0 (76.8-85.3) |

| >1000 | 15 | 32105/42709 | 82.0 (73.9-90.2) |

N: Sample Size; n: Number of Children with Antibiotics; random-effect meta-analysis was used to calculate the overall pooled prevalence of antibiotic utilization. For studies reported different economic zone, study setting, hospital level, study period, sample size, we conducted meta- analysis more than once. Six studies study period was before 2010, therefore, there were 35 studies included subgroup analysis of study period.

Risk factors of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children

We explored the risk factors of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children using qualitative analysis from five aspects and 12 items (Table 3). The presentation of factors here is grouped into those at children level (e.g. distribution of disease, lack of skills and knowledge), and physician level (e.g. lack of skills and knowledge, pressure from patient, physician-patient relationship, economic incentive and profit from prescribing medicine, lack of pathogen detection or low pathogen detection rate), and caregiver level (e.g. lack of skills and knowledge, put pressure on physician to get antibiotics, behavior of self-medicating with antibiotics at home for children) and retail pharmacies level (e.g. sale antibiotics without prescription) and hospital level (e.g. ward capacity).

Table 3.

Risk factors of antibiotic utilization in children in China.

| Risk factors | No. of studies (N=42) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | distribution of disease |

The biological systems and organs of children are not well-developed, especially those of younger children, which make children more vulnerable. Children with upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) are among the highest receivers of antibiotics. |

3 (7.1%) |

| lack of skills and knowledge | Middle school students still have problems in medication adherence, the management of expired drugs and the antibiotics cognition. | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Physicians | lack of skills and knowledge |

Physicians consider antibiotics to be anti-inflammatory drugs is a common misconception. Doctors might overprescribe antibiotics due to lack of knowledge of its rational use. Gaps between reported knowledge and actual practice within antibiotic prescribing are commonly encountered. |

19 (45.2%) |

| pressure from patient | Majority of the village doctors would prescribe antibiotics if their patients stick to getting them. | 5 (11.9%) | |

| physician-patient relationship | Ineffective communication between patients and physicians may lead to the unnecessary prescription of antibiotics. | 2 (4.8%) | |

| economic incentive and profit from prescribing medicine |

Retention of patients would increase physicians’ consultation fees. Doctors are able to make a profit from individual drug prescriptions, including antibiotics, and this may stimulate over-prescribing of antibiotics. |

5 (11.9%) | |

| lack of pathogen detection or low pathogen detection rate |

Uncertainty in the etiological diagnosis is reported as one of the main causes of fear when prescribing in primary care settings. The doctor paid little attention to microbiological examination. |

8 (19.0%) | |

| Caregivers | lack of skills and knowledge |

Parents have considerable misunderstandings that may contribute to inappropriate antibiotic use. Most of parents believe that taking antibiotics in advance could protect children from common diseases. |

28 (66.6%) |

| put pressure on physician to get antibiotics | Parents’ high expectations of quick relief of symptoms and recovery of their children would impose further pressure on doctors to prescribe antibiotic in order to make treatments more immediately effective. | 14 (33.3%) | |

| self-medicating with antibiotics at home for children | Most of the parents would use lower dose of antibiotics than required by the instruction with consideration of safety, and some parents would choose a higher dose. | 14 (33.3%) | |

| Retail pharmacies | sale antibiotics without prescription | Although antibiotics sales in retail pharmacies are not within the jurisdiction of government regulation, retail pharmacy is still the main channel for parents to purchase antibiotics. | 11 (26.2%) |

| Hospitals | ward capacity | Newborn units with more than 100 beds have the highest rate of antibiotic use, compared to units with 50 or fewer beds, and those with 51–100 beds. | 1 (2.4%) |

Distribution of disease in children has been regarded as a risk factor influencing antibiotic utilization by 7.1% (3/42) of studies. A study indicated that the reasons that lead physicians prescribe antibiotics were mainly clinical determinants such as severity of symptoms, immediate clinical issue [129]. Another survey on pediatric outpatient prescription found that respiratory infection was one of the diseases with the highest frequency, the most dosage of antibiotic utilization [86]. In addition, children lacking of skills and knowledge about antibiotics also influences antibiotic utilization. Although children knew that antibiotics were not antiviral drugs, they were less able to identify specific antibiotics [121].

A total of 45.2% (19/42) of studies suggested that physicians lacking of skills and knowledge was an important factor influencing antibiotic utilization of children. It was indicated that nearly 30% of pediatricians considered antibiotics to be anti-inflammatories [45], and some village doctors confused to select appropriate antibiotics for children [120]. Some studies explored that pressure from patient had an effect on antibiotic prescriptions. About 70% of the village doctors complied with the primary caregivers’ request even when they felt the antibiotics were unnecessary [120]. Physician-patient relationship was mentioned by 4.8% (2/42) of studies. Physicians wariness of medical disputes by dissatisfied patients might induce them to order unnecessary investigations and overprescribe antibiotics [77]. Economic incentives and profits from prescription also lead physicians to prescribe antibiotics. A study reported that inter-hospital competition was a driver of inappropriate prescribing, if patients did not have antibiotics they want, they will choose other hospital to purchase, leading to suffer financially [128]. A total of 19.0% (8/42) of studies reported that lacking of pathogen detection or low pathogen detection rate was also a risk factor. Through meta-analysis, we found that the overall pathogen detection rate among inpatients was 44.7% (95% CI: 29.7-59.7%, I2=99.7%, P<0.0001), but there was no study on outpatients. (Fig. S1 in Additional file 1).

A total of 66.6% (28/42) of studies reported that lacking of skills and knowledge from caregivers influences antibiotic utilization for children. Almost 66.3% of respondents mistakenly believed that antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs are the same drugs, 68.8% of respondents believed that antibiotics can cure infections caused by virus, 51.5% of respondents believed that antibiotics can be used to treat common cold, 69.9% of respondents believed that antibiotics can be used to treat pharyngitis or nonsuppurative tonsillitis, 37.9% of respondents didn’t know antibiotics should only be obtained with a doctor’s prescription, and 46.6% of respondents didn’t know inappropriate use of antibiotics can reduce the effectiveness of antibiotics (Table S9 in Additional file 1). A total of 33.3% (14/42) of studies reported put pressure on physician to get antibiotics was one of the risk factors influencing antibiotic utilization for children. A study reported that about half of the caregivers had requested antibiotics directly from physicians [117]. A total of 33.3% (14/42) of studies reported self-medicating with antibiotics at home for children was a risk factor of antibiotic utilization. A study reported that about 69.2% of caregivers would self-medication for children before visiting a doctor, in addition, to improve the effectiveness of treatment, they would increase the dosage arbitrarily [118].

For retail pharmacies, selling antibiotics without prescription has been regarded as a risk factor of antibiotic utilization for children. It was reported that individuals in most rural areas continue to have easy access to antibiotics [125]. The rate of antibiotic use was also associated with bed capacity, newborn units with more than 100 beds had the highest rate of antibiotic use, compared to units with 50 or fewer beds, and those with 51–100 beds [124].

Discussion

The prevalence of antibiotic utilization in Chinese children was high. The overall prevalence of antibiotic utilization among outpatients and inpatients was 63.8% and 81.3%, respectively, and caregivers’ self-medicating with antibiotics for children at home was 37.8%.

Two literature reviews reported a prevalence of 89% or 90.6% for antibiotic utilization in Chinese children, which was higher than that in our study [108, 132]. Compared to before 2010, the prevalence of antibiotics in children has decreased, which was 93.0 % [108, 132]. However, our results were still much higher than the standard values of 20% for outpatient and 60% for inpatient with antibiotic prescriptions issued in an antimicrobial stewardship policy by Chinese government [133]. In addition, the prevalence of antibiotic utilization for children in China was higher than that in the USA (17%-29% ) [134]. According to the ARPEC (Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children) report, the prevalence of antibiotic utilization from 226 hospitals in 41 countries was 36.7 % [12]. The overall prevalence of caregiver’s self-medicating of antibiotics for children at home was 37.8%, which was similar to the Chang et.al’ s finding (37.67% ) [122], but lower than that in India (69.4% ) [135].

Children are more susceptible to infection due to their unique peculiarities of body size, surface area, drug metabolism, and excretion, which may be associated with high antibiotic prevalence. However, acute upper respiratory infections (AURIs) are the most common condition associated with the excessive use of antibiotics [136]. Most AURIs are caused by viral infection and usually resolved after three to seven days [137]. However, the use rate of antiviral drugs in the treatment of AURIs in children is low, and most of physicians choose newer, broad-spectrum antibiotics [45]. Therefore, identifying the characteristics of childhood diseases and encouraging the prescriptions of older, narrow-spectrum antibiotics rather than newer, broad-spectrum antibiotics plays an important role in the process of rational use of antibiotics. For school student, there is no systematic teaching on antibiotics, therefore, it is difficult for them to identify antibiotics. In addition, students in different regions have varieties of understandings of antibiotics. The awareness of antibiotics utilization in central urban areas is higher than that of urban and rural areas and counties in suburbs, in addition, the awareness of antibiotics utilization in high school students is higher than that in junior high school and vocational high school [121]. Therefore, more efforts should be made to improve the cognition of student in different regions and different types of school.

The high prevalence of antibiotic utilization in children might have a strong association with physicians, such as lacking of skills and knowledge, pressure from patient, physician-patient relationship, economic incentive and profit from prescribing medicine, lacking of pathogen detection or low pathogen detection rate.

First, physicians in high-level hospitals are more likely to receive training on rational use of antibiotics than those in primary hospitals [138]. Physicians who has not attend related training are more likely to prescribe antibiotics [139]. Sometimes routine training for village doctors is held regularly, however, the content of training is repeated without new course, so the training seems not effective [140]. Therefore, continuous education can narrow the knowledge gap among physicians in different levels of hospital, meanwhile, the quality of education also should be emphasized.

Secondly, many caregivers faithfully embrace the effectiveness of antibiotics and injections over other regimens, and they will actively ask these therapies when visiting doctors. When physicians feel pressure from patients, about 70% of them would prescribe antibiotic [139]. On the other hand, the physician-patient relationship in China is highly strained [141]. Because there is no formal appointment system, patients generally prefer morning consultations, and there is long wait time and short consultations, which cause dissatisfaction among parents [142]. Therefore, some physicians protect themselves by regarding antibiotics as a weapon, especially expensive and injectable ones when they perceive that parents are dissatisfied [77]. They believe that prescribing antibiotics not only satisfy the patients’ claims, but further ease the strained doctor-patient relationship [143].

Thirdly, economic incentive and profit from prescribing medicine also lead physicians to prescribe antibiotics. Antibiotics, which account for approximately 20% of all drug sales in general hospitals [47], are the most frequently used medicine in Chinese medical facilities. In some regions, doctors’ income covered by government funds and profits from drug sales is virtually nail, these changes are not associated with improved antibiotic use. This may partly due to the low salary of medical staff, which motivates the personnel to seek additional income by providing other services and selling pharmaceutical products [144]. In addition, patient retention also could increase the income of physicians. In village clinic, if physicians adopt wait-and-watch policy or prescribe only antiviral drugs for fevers or the common cold, the caregivers would be dissatisfied with the village doctor, and would visit other village doctors. Furthermore, the primary caregivers would not return to the clinic the next time when their child had disease [120]. This may be a reason for the high prevalence of antibiotic utilization in children.

Fourthly, we found that pathogen detection rate among inpatients was 44.7% in our study, which was similar to the result in another study [108]. Antibiotic use without a clear indication is common [126], it is difficult for physicians to distinguish viral infection and bacterial infection, because the diagnostic tests, such as a routine blood test or C-reactive test, are not available in rural settings in China, so they make decisions based on clinical experience without clear indications. However, differentiating definitively between bacterial and viral causes of respiratory infections based on signs and symptoms alone is seldomly possible, and this imprecision and concern about missed bacterial diagnosis likely drives over-prescription of antibiotics [145]. Therefore, additional tools are necessary to physicians.

Parents’ perceptions and practices of how to use medicines have important effect on the management of childhood illness [146]. Through meta-analysis, we found that parents who had considerable misunderstandings may contribute to inappropriate antibiotic use. We found that 66% of caregivers believed that antibiotics could cure infection caused by viruses, a higher percentage than that was found in a pan-European study (54% ) [147]. Furthermore, half of the parents believed that antibiotics could cure common cold. Some parents often overestimate the benefits of antibiotics [148], and consider them as panacea [149]. For caregivers with correct recognition of antibiotics, the self-directed medication rate is lower than the doctor-dependent medication rate [115]. Thus, parents should receive more health education about antibiotics to improve the ability of antibiotic cognition. In addition, one study reported that about 60% of parents asked for doctors to prescribe antibiotics [150], and those who took antibiotic previously were more likely to put pressure on physicians to get them once again [151]. Other inappropriate behaviors include portraying severity of illness, or providing positive experience with use of antibiotic voluntary. However, sometimes, some physicians might misunderstand the willingness of the parents who just would like to ask for an advice or explanation from physicians rather than an antibiotic prescription [152]. Therefore, strategies for effective communication with patients and the prudent prescription of antibiotics are important. In addition, through meta-analysis, we found the overall prevalence of caregiver’s self-medicating of antibiotics for children at home was 37.8%, the result was lower than Yu et.al ’s finding [117]. The reasons for the prevalence of self-medicating children with antibiotics are multifactorial. Storing antibiotics at home increases the probability of medicating children with antibiotics, almost 50% of the caregivers keep antibiotics at home for children [153]. Parents who keep antibiotics at home prefer to self-medicate their children rather than directly seeking advice from a medical professional [122], and people tend to use the same drugs when they confronted similar symptoms based on their experience [154]. In addition, most of home-stored antibiotics are reported to be left over from previous prescriptions [113].

Having purchased antibiotics from retail pharmacies without a physician’s prescription is a critical factor contributing to self-medicating children with antibiotics. As early as 2004, the Chinese government introduced antimicrobial resistance targeted policies, banning the over-the-counter sale of antibiotics [155]. In addition, there is a separate counter displaying antibiotics and labeled “prescription-only medicine” posted to indicating customer antibiotics can only be sold with a prescription. However, in fact, more than 80% pharmacies dispensed antibiotics without a valid prescription. On the one hand, pharmacies dispensed the antibiotics without any prescription; on the other hand, dispensed them with a prescription provided by the pharmacy itself [156]. In addition, in 2012, to supervise the dispensing of medicines and ensure the safety of rational drug use, Chinese government launched the 12th five-year plan on drug safety, which called for all community and hospital pharmacies should have licensed pharmacists on duty during business hours by 201 5[157]. However, when dispensing the antibiotics, most pharmacy staff neither ask information of client nor provide relevant information about antibiotics. Through meta-analysis, we found that about 37% of caregivers do not know that antibiotics should only be obtained with a doctor’s prescription. Although the purchase of antibiotics without a prescription is forbidden by State Food and Drug Administration regulations, customers nevertheless have easy access to antibiotics in most areas. Therefore, stringent implementation of regulations concerning non-prescribed antibiotics in retail pharmacies is essential to restrict access to antibiotics.

Our study has several limitations. First, the heterogeneity across studies was statistically significant and the available data were insufficient to explain all the observed heterogeneity across studies. Second, age groups, hospital wards and characteristics of hospitalized children may also factors influence prevalence of antibiotic prescription. However, it was impossible to conduct meta-analyses due to a smaller number of studies assessing these factors. Third, there are few studies reported the antibiotic utilization in rural areas, however, as there is a rural population of nearly 800 million in China, antibiotic misuse in rural areas may be more serious, and we will investigate antibiotic use among children in rural areas. In addition, only published literatures were included, and potential publication bias cannot be neglected.

Conclusion

The prevalence of antibiotic utilization is much higher than the standard. The overall prevalence of antibiotic utilization among outpatients, inpatients, and caregiver’s self-medicating at home were 63.8%, 81.3%, and 37.8% respectively. The high prevalence of antibiotics is associated with multiple factors, including at children level (e.g. distribution of disease, lacking of skills and knowledge), and physician level (e.g. lacking of skills and knowledge, pressure from patient, physician-patient relationship, economic incentive and profit from prescribing medicine, lacking of pathogen detection or low pathogen detection rate), and caregiver level (e.g. lacking of skills and knowledge, put pressure on physician to get antibiotics, behavior of self-medicating with antibiotics at home for children) and retail pharmacies level (e.g. sale antibiotics without prescription) and hospital level (e.g. ward capacity). Efforts to improve the prevalence of antibiotic utilization require multisector cooperation, and long-term efforts should target at both children and caregivers, and also prescribers, like health education or training on the proper use of antibiotics and powerful supervision. Further studies should focus on antibiotic utilization of children, especially in rural area.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial and executive support of the Centre for Health Management and Policy Research, School of Public Health, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University for the assistance.

Abbreviations

- BRICS

Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa

- CARSS

China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System

- NASP

National Antibiotic Stewardship Program

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CI

Confidence interval

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- ARPEC

Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children

- AURIs

Acute upper respiratory infections

Authors’ contributions

S.G., Q.S., and Xu Z. confirmed the research questions and the search strategies before screening the database. S.G. and Xi Z. were the two reviewers, and they screened the titles and abstracts, read the full texts, and conducted the quality assessments for the included articles. Xu Z. acted as the third reviewer, made the final decision when disagreement between the two reviewers occurred. S.G., Xi Z. and L.S. participated in the data extracting and checked the accuracy of the data. S.G. wrote the manuscript, and Xu Z. checked the manuscript for polishing language. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (71774103), Young Scholar of Shandong University and The Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, data interpretation, writing the manuscript, and publication.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not public, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for this study was not required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wise R, Hart T, Cars O, et al. Antimicrobial resistance. Is a major threat to public health. BMJ. 1998;317(7159):609–610. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7159.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harbarth S, Samore MH. Antimicrobial resistance determinants and future control. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(6):794–801. doi: 10.3201/eid1106.050167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SSM N. Antibiotic resistance and the commensal flora: role of the commensal flora in the development and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Maastricht University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Boeckel TP, Gandra S, Ashok A, et al. Global antibiotic consumption 2000 to 2010: an analysis of national pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):742–750. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70780-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heddini A, Cars O, Qiang S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in China--a major future challenge. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61956-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zeman K. Effectiveness and tolerance of antibiotics in pediatrics patients. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2011;30(179):352–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nicolini G, Sperotto F, Esposito S. Combating the rise of antibiotic resistance in children. Minerva Pediatrica. 2014;66(1):31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pakyz AL, Gurgle HE, Ibrahim OM, et al. Trends in antibacterial use in hospitalized pediatric patients in United States academic health centers. Syst Rev. 2009;30(6):600–603. doi: 10.1086/597545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, et al. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053–1061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levy ER, Swami S, Dubois SG, et al. Rates and appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing at an academic children’s hospital, 2007-2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(4):346–353. doi: 10.1086/664761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutledge-Taylor K, Matlow A, Gravel D, et al. A point prevalence survey of health care-associated infections in Canadian pediatric inpatients. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(6):491–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Versporten A, Bielicki J, Drapier N, et al. The Worldwide Antibiotic Resistance and Prescribing in European Children (ARPEC) point prevalence survey: developing hospital-quality indicators of antibiotic prescribing for children. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(4):1106–1117. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida S, Takeuchi M, Kawakami K. Prescription of antibiotics to pre-school children from 2005 to 2014 in Japan: a retrospective claims database study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2018;40(2):397–403. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdx045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schindler C, Krappweis J, Morgenstern I, et al. Prescriptions of systemic antibiotics for children in Germany aged between 0 and 6 years. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2003;12(2):113–120. doi: 10.1002/pds.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W, Shen X, Wang Y, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use and assessment of antibiotic guidelines in Chinese children’s hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(8):821–828. doi: 10.1007/s00228-008-0489-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nyquist AC, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA. 1998;279(11):875–877. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong L, Yan H, Wang D. Antibiotic prescribing patterns in village health clinics across 10 provinces of Western China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62(2):410–415. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rogawski ET, Platts-Mills JA, Seidman JC, et al. Use of antibiotics in children younger than two years in eight countries: a prospective cohort study. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(1):49–61. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.176123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qu M, Lv B, Zhang X, et al. Prevalence and antibiotic resistance of bacterial pathogens isolated from childhood diarrhea in Beijing, China (2010-2014) Gut Pathogens. 2016;8:31. doi: 10.1186/s13099-016-0116-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li R, Xiao F, Zheng X, et al. Antibiotic misuse among children with diarrhea in China: results from a national survey. Peerj. 2016;4:e2668. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.China Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System: Surveillance of bacterial resistance in children and newborns across China from 2014 to 2017. Natl Med J China. 2018;98(40):3279–87. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Chang H, Shen X, Fu Z, et al. Antibiotic resistance and molecular analysis of Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from healthy schoolchildren in China. Scand J Infect Dis. 2010;42(2):84–89. doi: 10.3109/00365540903321598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yin X, Song F, Gong Y, et al. A systematic review of antibiotic utilization in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(11):2445–2452. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medernach RL, Logan LK. The Growing Threat of Antibiotic Resistance in Children. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2018;32(1):1–17. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao W, Wen C. The Zero Mark-up Policy for essential medicines at primary level facilities. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Administrative measures for the clinical use of antibacterial drugs. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . Notification of the implementation plan for special rectification on nationwide clinical antibiotic use. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . National action plan to combat antimcirobial resistance. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Plos Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin MF. Defining China's Rural Population. The China Quarterly. 1992;1992(130):392–401.

- 31.Pacific WHOR. People’s Republic of China health system review: Manila : WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.West S, King V, Carey TS, et al. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence No. 47. AHRQ Publication No. 02-E016. Rockville: Agency for Health care Research and Quality; 2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, et al. Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12(3):232–236. doi: 10.1159/000051263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang X, Zhuo Y. Analysis of appliance of antibiotics about outpatient transfusion prescriptions in our hospital. Guangzhou Med J. 2010;41(4):65–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu X. Analysis of the utilization of antibiotics in pediatric department of our hospital. China Pharm. 2010;21(44):4186–4188. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Xin L, Tan F. Analysis on the use of antibacterials in pediatric outpatient department of our hospital. China Pract Med. 2010;5(29):9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J. Analysis on antibiotic treatment among pediatric outpatients in our hospital in 2010. Chin J Med Guide. 2011;13(12):2166. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Li G, Xiang F. Analysis of antibiotic application in outptient pediatric prescriptions. Modern Hosp. 2011;11(5):57–58. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li X. The application situation analysis of antibiotic usage in outpatient department with acute upper respiratory infections in our hospital. China Modern Med. 2011;18(9):150–151. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang J, Liang Y. Clinical observation of 500 cases with antibiotics in outpatient department of pediatrics. Contemp Med. 2012;30:144–145. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang X, Xie J, Xu Y, et al. The investigation research of the prescription of antibiotic drugs in outpatient of the pediatric department of one hospital. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2012;5(36):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H. Analysis and evaluation of drug application in pediatric outpatients of our hospital. China Med Herald. 2012;9(08):114–115. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen L. Our hospital antimicrobial prescription pediatric clinic is not reasonable use analysis. J North Pharm. 2012;9(11):66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou H, Lin Z, Lv D, et al. Investigation of the use of antibacterial drugs in pediatric outpatient department of our hospital. Chin J Pharmacovigilance. 2012;9(09):566–568. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li L, Feng L. Analysis of drugs application for upper respiratory tract infection in pediatric outpatient. China Med Herald. 2013;10(02):114–116. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xiao B. Analysis of the use of antibiotics in 1553 outpatient pediatric patients. Med J Natl Defending Forces Southwest China. 2013;23(07):779–780. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen H, Zhu F, Lu H. Application analysis of antibacterial drugs in pediatric outpatient department of Lianzhou People’s Hospital. China Med Pharm. 2013;3(11):64–65. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu H. The analysis of the pediatric outpatient anti-infective drug using. Hebei Med. 2013;19(03):436–439. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miao C, Lei H, Rong Y, et al. Medication analysis on pediatrics outpatient prescription at our hospital. China Health Ind. 2014;5(4):7. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng Y. Analysis on the pediatric prescriptions in the outpatient. Med Forum. 2014;1:121–123. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gui M, Wang J. To analyze the service condition of antibacterial agents of upper respiratory tract infection prescription in pediatric outpatient department. Chinese Community Doctors. 2014;5(15):7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan Y, Cao L, Yu X, et al. Prescriptions of antibiotics for children with upper respiratory infections in outpatient department. Chin J Gen Pract. 2015;14(8):616–620. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu P, Lin R. Investigation on current situation of using antibiotics for acute upper respiratory infection in Children. J Pediatr Pharm. 2015;21(7):47–49. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu X, Liu T. Analysis of usage of anti-infection drugs in department of pediatrics in our hospital. China Med Pharm. 2015;5(24):72–74. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gao Y. Analysis of antibiotics in pediatric patients with acute upper respiratory tract infection. Chinese Community Doctors. 2016;32(19):13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie Y. MTP rationality of prescription and the effect of interventions in the treatment of acute upper respiratory tract infection in outpatient pediatrics. Anhui Med Pharm J. 2016;20(9):1784. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin Y, Nie C, Yang L, et al. Analysis and evaluation of prescriptions for pediatric upper respiratory tract infection. China Licensed Pharmacist. 2016;13(2):15–18. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J. Evaluation of the use of antimicrobial drugs in pediatric outpatients with acute respiratory infection. J Trop Med. 2016;16(06):796–798. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang S. Analysis of antibacterials usage in respiratory tract infection of outpatient department of pediatrics in our hospital. Chin J Drug Eval. 2017;34(4):290–293. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan Y. Analysis on application of oral medicine for upper respiratory tract infections in our hospital. Chin Foreign Med Res. 2017;15(13):142–143. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nie C, Zhang J, Zhao Q, et al. Investigation and analysis of antibiotics application in pediatric clinic of our hospital. Modern Hosp. 2017;17(08):1223–1225. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhang Z, Hu Y, Zou G, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory infections among children in rural China: a cross-sectional study of outpatient prescriptions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1287334. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1287334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei X, Zhang Z, Walley JD, et al. Effect of a training and educational intervention for physicians and caregivers on antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in children at primary care facilities in rural China: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1258–e1267. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wei X, Yin J, Walley JD, et al. Impact of China’s essential medicines scheme and zero-mark-up policy on antibiotic prescriptions in county hospitals: a mixed methods study. Trop Med Int Health. 2017;22(9):1166–1174. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Z, Li L, Huang F, et al. Analysis of rational drug use of the pediatric prescriptions from 45 grassroots hospitals in an area. Pharm Adm. 2018;27(17):86–89. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang C. Analysis of the use of antibiotics in outpatients with acute upper respiratory tract infections in pediatrics department. Clin Res Pract. 2019;4(03):118–119. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Peng L, Wang Z, Zhang Y. Analysis of rational use of antibiotic drugs in hospital pediatrics based on children’s drug utilization index and drug safety. Boletin De Malariologia Y Salud Ambiental. 2019;59(1):89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cui Y. Analysis of antibiotics in hospitalized children. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2011;04(23):43–44. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qiu Z, Xie L, Xie H. Application analysis on antibiotics in pediatric patient with acute upper respiratory tract infection. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2011;04(25):4–5. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen J, Wen Z. Research study on antibiotic application for bronchopneumonia of the children in-patient in pediatrics in 2010. Int Med Health Guid News. 2011;17(24):3075–3078. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lin Y. Analysis of antibiotics application in pediatric upper respiratory tract infection. Chin J Nosocomiol. 2011;21(12):2576–2577. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liang Z, Li L, Li K. Analysis of the use of antibiotic in pediatric inpatients. Med Recapitulate. 2011;17(12):1890–1891. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhou L. The analysis of nosocomial infection and antibiotics usage in hospitalized neonates. China Pract Med. 2012;07(15):32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bian H, Zhang T. Investigation of drug use in pediatrics in our hospital. Chin J Pharmacoepidemiol. 2012;21(3):138–139. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fang J. Antibiotics application in 196 pediatric patients with acute upper respiratory infection. J Modern Clin Med. 2012;38(2):123–124. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu W. An empirical analysis of antibiotic drug usage in pediatrics. World Health Digest Med Periodieal. 2012;39:72–73. [Google Scholar]

- 78.He M. Investigation of antibiotic use in hospitalized children with respiratory tract infection in our hospital from 2009 to 2011. Gems Health. 2012;4:389. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guan L. Investigation of antibiotic use in pediatric inpatient with acute upper respiratory tract infections. World Health Digest Med Periodieal. 2012;9(49):231–232. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang L, Yang P. Investigation and analysis of nosocomial infection and antibiotic application in 1148 hospitalized children. J Front Med. 2012;20:94–95. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu J, Shen N, Wang Y, et al. Application of antibiotics in neonatal wards. Chin J Nosocomiol. 2012;22(17):3836. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang Q, Sun C, Xu Y. Analysis on the usage of antibacterials in pediatric inpatients. Chin J Drug Appl Monit. 2012;9(06):348–350. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Che Y, Dong J. Use of antibiotics for neonates in a basic hospital and influencing factors analysis. Chin J Woman Child Health Res. 2013;24(3):296–298. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lu J, Huang J. Clinical analysis of antibiotics application for children with acute respiratory infection in Qinzhou. J Clin Pulmon Med. 2013;18(12):2210–2212. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Xu J. Analysis of the usage of antibacterials in pediatric inpatients. Chin J Pharmacoepidemiol. 2013;22(4):196–198. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Huang X, Zhang W, Xu Q. Investigation of 215 medical records in internal medicine of pediatrics and analysis of antimicrobial drug Use. J Pediatr Pharm. 2013;19(3):38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhan J, Chen Q. Investigation and analysis of the application condition of antibacterial agents on hospitalization children in our hospital. Nei Mongol J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;32(18):96–97. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Li C, Ren N, Wen X, et al. Changes in antimicrobial use prevalence in China: results from five points prevalence studies. Plos One. 2013;8(12):e82785. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yao Q, Luo Z. Clinical application of antibiotic in department of pediatrics. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2014;15:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wu M, Chen Y, Wu X. Investigation of pediatric medical records and analysis of antimicrobial drug application in a certain hospital. J Navy Med. 2014;4:260–262. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhu G, Wu X. Antibiotics usage analysis in pediatric inpatients. J Modern Med Health. 2014;30(21):3239–3240. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu Y. Survey and analysis of the use of antibacterials in pediatric inpatients of our hospital. China Licensed Pharmacist. 2014;11(11):13–15. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang W. Analysis of the use of antibiotic in our hospital in 2013 were from January to December in pediatrics. China Health Ind. 2014;11(21):35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Huang G, Miao D, Lai X, et al. Investigation of use of antibiotics by hospitalized neonates. Chin J Nosocomiol. 2014;24(01):97–98. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Cheng X, Yan X, Lin S. The Investigation and analysis of antimicrobial drugs used by 258 pediatric inpatients. J Hubei Univ Nationalities Med Ed. 2014;31(02):40–41. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cheng H, Wu D. Survey of antimicrobial agents use in pediatric inpatients. Chin J Pharmaco Epidemiol. 2014;23(12):737–740. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Y, Ye J. Pharmaceutical intervention on the use of antibiotics in the neonatology of X-hospital. China Health Ind. 2015;16:12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li L, Xu H, Zhou J, et al. Application effect of clinical pathway management in infantile capillary bronchitis and the impact on antibiotics utilization ratio. Chin J Clin Ration Drug Use. 2017;10(12):35–36. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Su X, Zhu H, Yuan H. Analysis of antibiotic use for bronchial pneumonia in pediatrics. J Kunming Med Univ. 2017;38(7):126–129. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhu J, Luo M, Li L, et al. Promotion of PDCA cycle on rational usage of antibiotics in neonatal department. J Guangdong Pharmaceut Univ. 2017;33(5):649–653. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Li R, Zhang J, Li G. Analysis of clinical antibiotic use and adverse reactions in pediatrics. Chin Nurs Res. 2018;32(23):3815–3817. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen Z, Xiao Y. Analysis on usage of antibacterial drugs in inpatient children of Tianjin Children’s Hosptial in 2016. Drugs Clinic. 2018;33(03):672–675. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang JS, Liu G, Zhang WS, et al. Antibiotic usage in Chinese children: a point prevalence survey. World J Pediatr. 2018;14(4):335–343. doi: 10.1007/s12519-018-0176-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ju J. Study on the effect of pharmacist intervention on rational use of pediatric antibiotics. China Foreign Med Treat. 2019;38(7):127–129. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wei W, Wang XF, Liu JP, et al. Status of antibiotic use in hospitalized children with community-acquired pneumonia in multiple regions of China. Chin J Contemp Pediatr. 2019;21(1):11–17. doi: 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Niu J. Analysis on the treatment and intervention of pediatric upper respiratory tract infection in hospital. Chin Community Doctors. 2020;36(16):18. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Miao R, Wan C, Wang Z, et al. Inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among pediatric inpatients in different type hospitals. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(2):e18714. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Zhang M, Ma XY, Feng ZQ, et al. Survey of antibiotic use among hospitalised children in a hospital in Northeast China over a 4-year period. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2020;25(2):e12282. doi: 10.1111/jspn.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wei X, Zhang Z, Hicks JP, et al. Long-term outcomes of an educational intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for childhood upper respiratory tract infections in rural China: Follow-up of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PloS Med. 2019;16(2):e1002733. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cui F, Yuan Y, Cui H, et al. A survey on the knowledge of antibiotics of children parents in three children-hospitals of Beijing. Chin J Med. 2015;8:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhao M, Nan W, Jiao X, et al. Survey on the parent situation of antibacteriol drugs use for children. Northwest Pharmaceut J. 2016;31(02):200–202. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yin Y, Cui N. Antibiotics use among preschool children and parental cognition in Ji’nan city. Chin J Public Health. 2018;34(1):118–120. [Google Scholar]

- 113.Peng D, Zhou X. Parents’ antibiotic use for children in Ningbo: knowledge, behaviors and influencing factors. J Zhejiang Univ. 2018;47(2):156–162. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2018.04.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yao Z, Zhou J, Li Y, et al. Prevalence of self-medication with antibiotics in kindergarten children of Guangzhou city. Chin J Public Health. 2013;29(10):1485–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Miao R. Investigation on the impact of parents’ cognitive level of antibiotics on self-directed use of antibiotics in pupils. Pract Prev Med. 2013;20(1):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang G, Cao L, Yuan Y. 10 years’ changes on parent’s antibiotic knowledge in Beijing. Chin J Med. 2014;10:41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Yu M, Zhao G, Stålsby LC, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of parents in rural China on the use of antibiotics in children: a cross-sectional study. Bmc Infect Dis. 2014;14:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ding L, Sun W, Li Y, et al. Studying on the status of rural parents’ cognition on antibiotics and its influencing factors. Chin Health Serv Manage. 2016;33(2):111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cen Q, Dai D. The relationship between novice mother and neonates in use of antibiotic cold medications and the effects of health education. Drug Eval. 2016;13(21):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang Z, Zhan X, Zhou H, et al. Antibiotic prescribing of village doctors for children under 15 years with upper respiratory tract infections in rural China: A qualitative study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(23):e3803. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Cheng YC, Pan YP, Zhang Y, et al. Investigation of the cognition and behavior on drug safety in Beijing middle school students. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2017;49(6):1038–1043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Chang J, Lv B, Zhu S, et al. Non-prescription use of antibiotics among children in urban China: a cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2018;16(2):163–172. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1425616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Fan W, Mu J, Song X, et al. Investigation on antibiotic cognition and use of parents of preschool children in Tianjin. Chin Prim Health Care. 2019;33(4):61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ge Y, Chipenda DS, Liao XP. Advanced neonatal medicine in China: Is newborn ward capacity associated with inpatient antibiotic usage? PloS One. 2019;14(8):e219630. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0219630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cheng J, Chai J, Sun Y, et al. Antibiotics use for upper respiratory tract infections among children in rural Anhui: children’s presentations, caregivers’ management, and implications for public health policy. J Public Health Policy. 2019;40(2):236–252. doi: 10.1057/s41271-019-00161-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang J, Sheng Y, Ni J, et al. Shanghai parents’ perception and attitude towards the use of antibiotics on children: A cross-sectional study. Infect Drug Resist. 2019;12:3259–3267. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S219287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Ye D, Yan K, Zhang H, et al. A survey of knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning antibiotic prescription for upper respiratory tract infections among pediatricians in 2018 in Shaanxi Province, China. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020;18(9):927–936. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2020.1761789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wei X, Deng S, Haldane V, et al. Understanding factors influencing antibiotic prescribing behaviour in rural China: a qualitative process evaluation of a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2020;25(2):94–103. doi: 10.1177/1355819619896588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang J, Cameron D, Quak SH, et al. Rates and determinants of antibiotics and probiotics prescription to children in Asia-Pacific countries. Beneficial Microbes. 2020;11(4):329–338. doi: 10.3920/BM2019.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wang J, Huang C, Li Z, et al. Knowledge and behavior of antibiotic use for upper respiratory tract infection among parents of young children in Changsha city. Chin J Public Health. 2017;33(3):415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zhang Y, Lin S, Li G, et al. Cognition and usage of antibiotics in caregivers of 0-6 years old children in the rural area of Weinan City, 2015. Pract Prev Med. 2017;24(2):196–198. [Google Scholar]

- 132.Li W, Lu Y, Chen M, et al. Meta-analysis on Antibiotics Usage in Children with Upper Respiratory Tract Infection in China. Chin Pharmaceut J. 2017;52(10):880–885. [Google Scholar]

- 133.Department of Health MoH National antimicrobial drug clinical application special rehabilitation program (Excerpt) Chin Community Physician (Medical) 2012;14:8. [Google Scholar]

- 134.Poole NM, Shapiro DJ, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Antibiotic prescribing for children in United States emergency departments: 2009-2014. Pediatrics. 2019;143:2. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kumar R, Goyal A, Padhy BM, et al. Self-medication practice and factors influencing it among medical and paramedical students in India: A two-period comparative cross-sectional study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2016;7(2):143–148. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.184694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhao H, Bian J, Han X, et al. Outpatient antibiotic use associated with acute upper respiratory infections in China: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(106193). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 137.Hao Q, Dong BR, Wu T. Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:D6895. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Bai Y, Wang S, Yin X, et al. Factors associated with doctors’ knowledge on antibiotic use in China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23429. doi: 10.1038/srep23429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sun Q, Dyar OJ, Zhao L, et al. Overuse of antibiotics for the common cold - attitudes and behaviors among doctors in rural areas of Shandong Province, China. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2015;16:6. doi: 10.1186/s40360-015-0009-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yin J, Dyar OJ, Yang P, et al. Pattern of antibiotic prescribing and factors associated with it in eight village clinics in rural Shandong Province, China: a descriptive study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2019;113(11):714–721. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trz058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ma S, Huang Y, Yang Y, et al. Prevalence of burnout and career satisfaction among oncologists in China: A national survey. Oncologist. 2019;24(7):e480–e489. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Yin J, Wei X, Li H, et al. Assessing the impact of general practitioner team service on perceived quality of care among patients with non-communicable diseases in China: a natural experimental study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2016;28(5):554–560. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kunin CM, Tupasi T, Craig WA. Use of antibiotics. A brief exposition of the problem and some tentative solutions. Ann Intern Med. 1973;79(4):555–560. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-79-4-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wang J, Wang P, Wang X, et al. Use and prescription of antibiotics in primary health care settings in China. Jama Intern Med. 2014;174(12):1914–1920. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.McKay R, Mah A, Law MR, et al. Systematic review of factors associated with antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(7):4106–4118. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00209-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Togoobaatar G, Ikeda N, Ali M, et al. Survey of non-prescribed use of antibiotics for children in an urban community in Mongolia. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88(12):930–936. doi: 10.2471/BLT.10.079004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Grigoryan L, Burgerhof JG, Degener JE, et al. Attitudes, beliefs and knowledge concerning antibiotic use and self-medication: a comparative European study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16(11):1234–1243. doi: 10.1002/pds.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Coxeter PD, Mar CD, Hoffmann TC. Parents’ expectations and experiences of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections in primary care. Ann Family Med. 2017;15(2):149–154. doi: 10.1370/afm.2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Sun X, Jackson S, Carmichael GA, et al. Prescribing behaviour of village doctors under China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(10):1775–1779. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zeru T, Berihu H, Buruh G, et al. Parental knowledge and practice on antibiotic use for upper respiratory tract infections in children, in Aksum town health institutions, Northern Ethiopia: a croos-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35:142. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.35.142.17848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.El-Hawy RM, Ashmawy MI, Kamal MM, et al. Studying the knowledge, attitude and practice of antibiotic misuse among Alexandria population. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(6):349–354. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2016-001032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Connelly J. Critical realism and health promotion: effective practice needs an effective theory. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(2):115–119. doi: 10.1093/her/16.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Sun C, Hu YJ, Wang X, et al. Influence of leftover antibiotics on self-medication with antibiotics for children: a cross-sectional study from three Chinese provinces. Bmj Open. 2019;9(12):e33679. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Jin C, Ely A, Fang L, et al. Framing a global health risk from the bottom-up: User perceptions and practices around antibiotics in four villages in China. Health Risk Soc. 2011;13(5):433–449. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2011.596188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Administration CFAD . Notice on strengthening the administration of antibacterial drug sales at retail pharmacies and promoting rational drug use. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 156.Gong Y, Jiang N, Chen Z, et al. Over-the-counter antibiotic sales in community and online pharmacies, China. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(7):449–457. doi: 10.2471/BLT.19.242370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.The State Council of People’s Republic of China . The twelfth five-year plan on drug safety. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 158.He D. 877 example young child acute under respiratory tract infects in hospital trouble clinical analysis. Chin Manipulation Rehabil Med. 2011;8:97. [Google Scholar]

- 159.Xie H, Zhou J, Liu F. Paediatric antibiotic use and monitoring of common bacterial resistance. Chin J Ethnomed Ethnopharm. 2011;20(9):8. [Google Scholar]

- 160.Wu J. The Analysis of utilization of antibiotics in children with respiratory tract infection. Guide China Med. 2012;10(11):31–32. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are not public, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.