Abstract

Objectives:

To examine real-time relationships between social interactions and poststroke mood and somatic symptoms in participants’ daily environments.

Design:

Prospective observational study using smartphone-based ecological momentary assessment (EMA) surveys 5 times a day for 2 weeks. Multilevel models were used to analyze data for concurrent and lagged associations.

Setting:

Community.

Participants:

Adults (NZ48) with mild stroke.

Interventions:

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures:

EMA measures of self-appraisal of social interactions (confidence, satisfaction, and success), as well as mood (depression and anxiety) and somatic (pain and fatigue) symptoms.

Results:

In concurrent associations, increased depressed mood was associated with reduced ratings of all aspects of social interactions. Fatigue was associated with reduced ratings of social satisfaction and success. In lagged associations, increased anxious mood preceded increased subsequent social confidence. Higher average social satisfaction, confidence, and success were related to lower momentary fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood at the next time point. Regarding clinicodemographic factors, being employed was concurrently related to increased social interactions. An increased number of comorbidities predicted higher somatic, but not mood, symptoms at the next time point.

Conclusions:

This study provides preliminary evidence of dynamic relationships between social interactions and somatic and mood symptoms in individuals with mild stroke. Interventions to not only address the sequelae of symptoms, but also to promote participation in social activities in poststroke life should be explored.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Ecological momentary assessment, Fatigue, Interpersonal relations, Rehabilitation, Stroke

Social isolation adversely affects physiological and mental health1 and may be a risk factor for stroke.2 Social isolation, defined as “the relative absence of social relationships,”3(pS54) is associated with decreased cognition,4 depression,5 anxiety,6 and early mortality.7 Social interaction is defined as an encounter between 2 or more individuals in which verbal or nonverbal communication is mutual (ie, at least 2 parties are communicating with each other).8 Decreased social interactions in personal, professional, and community settings are common for individuals after stroke and contribute to social isolation,9 leading to adverse effects on the individual’s mental health and well-being.10 Conversely, social isolation can be a consequence of stroke. Common sequelae that can contribute to reduced social interactions after stroke include somatic symptoms such as pain11,12 and fatigue,13 and mood symptoms such as anxiety13 and depression.14 These symptoms may affect an individual’s capacity to participate in prestroke social activities.

Research concerning the relationships between social isolation and discrete mood or somatic symptoms is often cross-sectional.15,16 Clinically, symptoms and functions are often measured at several time points weeks or months apart.17 Although such methods are likely to capture incidence and perhaps long-term associations, they do not fully capture the complexity of time-varying relationships between variables. There is emerging evidence that mood and somatic symptoms can vary within a given day. Researchers are challenged to develop interventions that can respond to within- and across-day fluctuations.18 Thus, we proposed the use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA) to assess microlevel trends of social interactions and poststroke symptoms and to understand their dynamic relationships. EMA is a method of intensive, repeated measurement that is useful for assessing temporal relationships between variables across hours or days in one’s natural environment.

Current forms of EMA use electronic surveys administered on a smart device such as a smartphone or iPod Touch,a enabling effective collection of time- and context-specific data. This method has been well validated to study mood, cognition, and behaviors in different populations, including stroke.19–21 Paolillo et al22 used electronic EMA to explore the interaction between social activity and mood, fatigue, and pain in 20 older adults with human immunodeficiency virus and found real-time relationships between being alone and these symptoms. No study to date has examined such relationships between social interactions and somatic and mood symptoms in a stroke population.

The purpose of this study was to use EMA to examine real-time relationships between social interactions and poststroke symptoms of pain, fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood to lay the groundwork for developing interventions that effectively address social isolation or sequelae after stroke. To measure social interactions comprehensively, we examined social interactions via 3 quality indicators: social satisfaction, social confidence, and social success. We explored concurrent (responses within the same EMA survey) and lagged (responses from one survey predicting responses on the next survey) relationships of these variables. For concurrent relationships, we hypothesized that increased social interactions would be related to decreased mood and somatic symptoms. Regarding lagged relationships, we hypothesized that increased social interactions on one survey would predict decreased mood and somatic symptoms on the next survey. Similarly, we hypothesized that decreases in these symptoms would predict increased social interactions on the next survey.

Methods

Study sample

Participants were recruited from the Stroke Management and Rehabilitation Team Stroke Registry, a single-hospital database of individuals who consented to be contacted for future research at the time of hospitalization for stroke. Inclusion criteria were history of mild ischemic stroke at least 3 months before enrollment, aged 18 years or older, and English language fluency. Mild stroke was defined by a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale23 score of 5 or lower at the time of stroke onset and a modified Rankin Scale score of 2 or less at the time of in-person screening. Exclusion criteria were previous comorbid neurologic or psychiatric disorders, severe communication difficulty (Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test24 score <24), severe apraxia (Apraxia Screen of Test for Upper-Limb Apraxia25 score <6), evidence of unilateral visual inattention (Star Cancellation Test26 ≤44), hemorrhagic stroke, and visual problems that would interfere with reading text on a small screen (visual acuity worse than 20/100 corrected vision on the Lighthouse Near Visual Acuity Test27).

Procedures

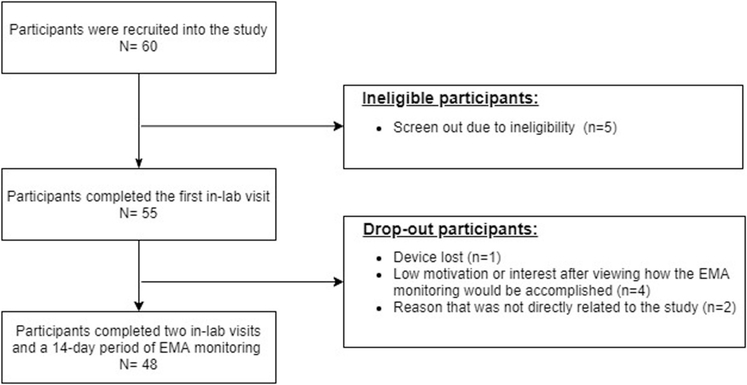

Data were collected between October 2018 and March 2019. We recruited 60 potential participants. Five participants did not meet the eligibility criteria, and 7 participants dropped out before completing the study. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of participant recruitment and completion. Forty-eight participants completed 2 in-lab visits and a 14-day period of EMA monitoring. At the first visit, participants provided written, informed consent in compliance with the institutional review board at the study site, completed a standardized screening to ensure eligibility, and participated in training on the use of status/post,b an EMA survey mobile application (app) on either an iPod Toucha provided by the research team or the participant’s own iPhone.a Orientation to the protocol included instructions for participants to complete surveys by themselves without aid or input from others. Participants completed an in-person practice survey monitored by the examiner to assess any difficulties participants had with the device or survey questions and were provided with a hotline to call should questions arise.

Fig 1.

Flow diagram showing participant recruitment and completion.

The EMA protocol started within 1 week of the first visit. At home, participants were prompted by the smart device to complete electronic surveys 5 times per day for 2 weeks (total of 70 surveys). Surveys were timed for random initiation at approximately 2.5-hour intervals and occurred in the morning, mid-morning, mid-day, early evening, and evening. On the first 2 days and periodically thereafter, the examiner called the participant to verify whether they had any questions completing the surveys at home. After the EMA completion, participants visited the lab to return the iPod Touch or delete the status/post app from their personal iPhones. All participants received an honorarium to acknowledge their research contribution.

Measures

We modified questions from a validated EMA survey.22 Each EMA survey included questions about current ratings of depressive mood, anxious mood, pain, and fatigue. Response options were rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). A social question asked, “Who is with you right now?” Response options for this question included: alone, co-worker(s), family member(s), friend(s), health care provider(s), pet(s), spouse or partner, other known people, unknown people, and people you are socializing with electronically. To harmonize with other studies22,28 defining social relationships as only including human interactions, participants who indicated that they were not currently “alone” or with “pets” were prompted to answer 3 questions related to quality of social interactions: satisfaction (“I am satisfied in my interaction with the person(s) I am with”), confidence (“I am confident with my social interaction”), and success (“I am successful with my social interaction”). Response options were rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (not confident/satisfied/successful) to 7 (very confident/satisfied/successful). Higher scores indicate higher ratings of symptoms and social interactions.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the clinicodemographics of the study sample. Our data were structured such that EMA observations (level 1) were nested within individuals (level 2). We applied multilevel modeling (MLM) to examine concurrent and lagged associations between social interactions and symptoms based on the time of day. Thus, EMA observations were modeled as level 1 (within-person level) units nested within individuals, who were modeled as level 2 (between-person level). In all models, demographic variables were included as covariates and retained regardless of statistical significance to control for effects from the covariates. Categorical covariates were dummy coded. Other covariates such as age, education, and comorbidities were continuous variables. Longitudinal data have autoregressive error situations in which measurement occasions close in time to one another have a stronger relationship than measurement occasions that are separated further in time.29 Thus, the autoregressive correlation was used to correct the autoregressive error with the exception of the model examining the lagged association between social interactions and fatigue under the third set of MLM models (see below) because the model without the autoregressive correlation had better model fit than the model with it. The significance level was set at 0.05. Missing data were not replaced because MLM analyses are robust to missing data.30–32 The average amount of missing data in this EMA study was 18.1%. Statistical tests were performed using R Studio 1.1463 running R 3.5.2.c

To better uncover the temporal complexity of study variables, we conducted 3 sets of models to examine the (1) concurrent association: social interactions as predictors of same-survey symptoms; (2) lagged associations: social interactions as predictors of next-survey symptoms; and (3) lagged associations: symptoms as predictors of next-survey social interactions.

For the first set, 3 individual models were constructed for 3 EMA social variables (ie, satisfaction, confidence, and success), which were entered as dependent variables for each model. Independent variables were 4 symptom ratings. EMA symptom variables were person-centered; the centered value indicated the momentary change relative to each person’s average for 2 weeks. This centering enabled examination of within-person and between-person variance separately.33 The centered EMA symptom variables were entered as level 1 variables, whereas the individual’s average values of symptom variables were entered as level 2 variables in all 3 models.

For the second set, 3 individual models were built for social satisfaction, confidence, and success. Independent variables were 4 EMA symptom ratings from a time point (t). The social interaction variables at the next time point (t+1) were dependent variables. The EMA symptom variables at t were person-centered and entered as level 1 variables, whereas the individual’s average values of symptom variables were entered as level 2 variables in all 3 models.

For the third set, individual models with social satisfaction, confidence, and success were constructed for each of the 4 symptoms, resulting in 12 models. Independent variables were EMA social satisfaction, confidence, and success ratings from a time point (t), whereas EMA symptom ratings at the next time point (t+1) were dependent variables. The social interaction variables at t were person-centered and entered as level 1 variables, whereas the individual’s average values of those variables were entered as level 2 variables in all 12 models.

Results

Sample characteristics

The average EMA survey completion rate was 81.9% (57 out of 70 surveys). The average age of participants was 61 years (table 1). The majority of participants were men (58.3%), white (52.1%), married (56.3%), and unemployed (64.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics (N = 48)

| Demographics | Value | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 61.75 ± 11.08 | 38–87 |

| Years of education, mean ± SD | 14.52 ± 2.49 | 12–20 |

| Sex | ||

| Women, % | 41.7 | NA |

| Men, % | 58.3 | NA |

| Race | ||

| White, % | 52.1 | NA |

| Black, % | 47.9 | NA |

| Marital status | ||

| Married, % | 56.3 | NA |

| Unmarried, % | 43.8 | NA |

| Employment | ||

| Employed, % | 35.4 | NA |

| Unemployed, % | 64.6 | NA |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| MoCA | 25.67 ± 2.94 | 17–30 |

| CCI, mean ± SD | 4.27 ± 2.94 | 1–13 |

| mRS, mean ± SD | 0.27 ± 0.61 | 0–2 |

| NIHSS, mean ± SD | 1.46 ± 1.40 | 0–5 |

| Days since injury, mean ± SD | 907.02 ± 526.78 | 213–2615 |

| Stroke type | ||

| Ischemic, % | 100 | NA |

| Lesion laterality | ||

| Right, % | 46.8 | NA |

| Left, % | 23.4 | NA |

| Bilateral, % | 6.4 | NA |

| Unknown, % | 23.4 | NA |

| EMA variables | ||

| Social satisfaction, mean ± SD | 6.23 ± 1.33 | 1–7 |

| Social confidence, mean ± SD | 6.30 ± 1.26 | 1–7 |

| Social success, mean ± SD | 6.23 ± 1.30 | 1–7 |

| Pain, mean ± SD | 1.65 ± 0.80 | 1–5 |

| Fatigue, mean ± SD | 1.78 ± 1.02 | 1–5 |

| Anxious mood, mean ± SD | 1.28 ± 0.58 | 1–5 |

| Depressed mood, mean ± SD | 1.23 ± 0.56 | 1–5 |

Abbreviations: MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale.

For the question, “Who is with you right now?” 69.9% of responses were a response other than “alone” or “pet.” For social interactions, the average scores were 6.23±1.33 for social satisfaction, 6.30±1.26 for confidence, and 6.23±1.30 for success. For somatic symptoms, pain averaged 1.65±1.80 and fatigue averaged 1.78±1.02. For mood symptoms, the average scores were 1.28±0.58 for anxious mood and 1.23±0.56 for depressed mood.

Concurrent associations: social interactions as predictors of same-survey symptoms

Table 2 displays the MLM results for all concurrent associations between poststroke symptoms and social interactions after controlling for clinicodemographic covariates. Fatigue and depressed mood were negatively associated with social satisfaction. A 1-unit increase in depressed mood was associated with a 0.237-point reduction in social confidence. Increased social success was concurrently associated with decreased fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood. Pain was not significantly related to any social interaction variables (P>.05). In addition, higher average fatigue was associated with lower momentary social satisfaction, confidence, and success over the 2-week period.

Table 2.

Concurrent associations between social interaction variables and symptoms controlling for covariates (dependent variable = social interaction variables)

| Models |

Social Satisfaction |

Social Confidence |

Social Success |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1915) | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 5.648* | 1.329 | <.001 | 3.041 | 8.255 | 4.943* | 1.250 | <.001 | 2.491 | 7.395 | 5.702* | 1.401 | <.001 | 2.955 | 8.450 |

| Pain† | 0.056 | 0.042 | .182 | −0.026 | 0.139 | −0.017 | 0.039 | .670 | −0.094 | 0.061 | 0.030 | 0.038 | .438 | −0.045 | 0.105 |

| Fatigue† | −0.062* | 0.026 | .018 | −0.114 | −0.011 | −0.017 | 0.024 | .472 - | 0.065 | 0.030 | −0.061* | 0.024 | .011 | −0.108 | −0.014 |

| Anxious mood† | −0.088 | 0.050 | .080 | −0.187 | 0.010 | −0.084 | 0.047 | .070 | −0.175 | 0.007 | −0.157* | 0.046 | .001 | −0.247 | −0.067 |

| Depressed mood† | −0.281* | 0.056 | <.001 | −0.391 | −0.171 | −0.237* | 0.052 | <.001 | −0.339 | −0.136 | −0.155* | 0.051 | .003 | −0.255 | −0.054 |

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 36) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain‡ | 0.242 | 0.307 | .435 | −0.380 | 0.865 | 0.245 | 0.288 | .400 | −0.339 | 0.830 | 0.228 | 0.324 | .486 | −0.429 | 0.886 |

| Fatigue‡ | −0.822* | 0.315 | .013 | −1.461 | −0.183 | −0.719* | 0.296 | .020 | −1.319 | −0.119 | −0.844* | 0.333 | .016 | −1.518 | −0.169 |

| Anxious mood‡ | 0.220 | 0.726 | .763 | −1.252 | 1.693 | 0.338 | 0.682 | .624 | −1.045 | 1.721 | −0.056 | 0.766 | .942 | −1.609 | 1.497 |

| Depressed mood‡ | −0.563 | 0.681 | .414 | −1.945 | 0.819 | −0.580 | 0.640 | .371 | −1.879 | 0.719 | −0.262 | 0.718 | .718 | −1.719 | 1.195 |

| Age | 0.020 | 0.015 | .176 | −0.009 | 0.050 | 0.027 | 0.014 | .054 | 0.000 | 0.055 | 0.021 | 0.015 | .191 | −0.011 | 0.052 |

| Race | 0.247 | 0.368 | .507 | −0.500 | 0.993 | 0.301 | 0.346 | .390 | −0.400 | 1.002 | 0.189 | 0.388 | .629 | −0.598 | 0.977 |

| Sex | 0.292 | 0.300 | .337 | −0.316 | 0.899 | 0.329 | 0.282 | .250 | −0.242 | 0.901 | 0.297 | 0.316 | .353 | −0.343 | 0.938 |

| Education | 0.022 | 0.056 | .692 | −0.091 | 0.135 | 0.029 | 0.052 | .579 | −0.077 | 0.135 | 0.018 | 0.059 | .758 | −0.101 | 0.138 |

| Marital status | −0.450 | 0.357 | .215 | −1.173 | 0.273 | −0.572 | 0.336 | .097 | −1.252 | 0.109 | −0.327 | 0.376 | .390 | −1.089 | 0.435 |

| Comorbidities | 0.054 | 0.052 | .308 | −0.052 | 0.160 | 0.038 | 0.049 | .445 | −0.062 | 0.138 | 0.048 | 0.055 | .386 | −0.064 | 0.160 |

| Employee status | 0.721 | 0.337 | .040 | 0.036 | 1.405 | 0.762 | 0.317 | .021 | 0.119 | 1.404 | 0.726 | 0.356 | .049 | 0.003 | 1.449 |

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | |||||||||

| AR(1) | 0.156 | 0.108 | 0.203 | 0.280 | 0.231 | 0.326 | 0.122 | 0.074 | 0.170 | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.846 | 0.654 | 1.094 | 0.788 | 0.621 | 1.001 | 0.899 | 0.726 | 1.112 | ||||||

| Residual | 0.847 | 0.819 | 0.875 | 0.791 | 0.819 | 0.848 | 0.766 | 0.741 | 0.791 | ||||||

NOTE. References for categorical variables: sex: men = 0, women = 1; race: black = 0, white = 1; married status: unmarried = 0, married = 1; employment status: unemployed = 0, employed = 1.

Abbreviations: AR(1), autoregressive matrix; CI, confidence interval.

Significance level was set at P<.05.

Person-centered variable representing deviation (change) from an individual’s average.

Each individual’s average of EMA values over the 2-week-long monitoring period.

Lagged associations: symptoms as predictors of next-survey social interactions

Table 3 displays all MLM results in which symptoms predicted social interactions on the next survey after controlling for covariates. Increased anxious mood was negatively associated with subsequent social confidence. No other significant associations were found between within-person symptoms and social variables in MLMs with lagged effects. Higher average fatigue was associated with lower momentary social satisfaction, confidence, and success over the 2-week period. Increased age was positively associated with social confidence, and being unmarried was negatively associated with social confidence. Being employed was positively associated with social satisfaction, confidence, and success.

Table 3.

Lagged associations between social interaction variables and symptoms controlling for covariates (dependent variable = social interaction variables)

| Models |

Social Satisfaction |

Social Confidence |

Social Success |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | Estimation | SE | P Value | 95% CI | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1391) | |||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.570 | 1.314 | .001 | 1.992 | 7.149 | 4.060 | 1.293 | .002 | 1.523 | 6.598 | 5.245 | 1.367 | <.001 | 2.564 | 7.926 |

| Pain* | 0.071 | 0.053 | .178 | −0.032 | 0.174 | 0.058 | 0.050 | .246 | −0.040 | 0.156 | 0.030 | 0.048 | .527 | −0.064 | 0.124 |

| Fatigue* | −0.009 | 0.036 | .797 | −0.079 | 0.060 | −0.018 | 0.034 | .601 | −0.084 | 0.048 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.626 | −0.048 | 0.079 |

| Anxious mood* | −0.097 | 0.060 | .107 | −0.214 | 0.021 | −0.138† | 0.057 | .016 | −0.249 | −0.026 | −0.029 | 0.055 | 0.603 | −0.137 | 0.079 |

| Depressed mood* | 0.023 | 0.071 | .748 | −0.117 | 0.162 | 0.055 | 0.068 | .414 | −0.077 | 0.188 | −0.086 | 0.065 | 0.188 | −0.214 | 0.042 |

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 36) | |||||||||||||||

| Pain‡ | 0.375 | 0.304 | .225 | −0.241 | 0.991 | 0.347 | 0.299 | .253 | −0.259 | 0.954 | 0.278 | 0.317 | 0.386 | −0.364 | 0.920 |

| Fatigue‡ | −0.984* | 0.305 | .003 | −1.603 | −0.364 | −0.896† | 0.301 | .005 | −1.506 | −0.286 | −1.028† | 0.318 | 0.003 | −1.674 | −0.382 |

| Anxious mood‡ | 0.401 | 0.740 | .591 | −1.099 | 1.901 | 0.447 | 0.728 | .543 | −1.029 | 1.923 | 0.003 | 0.770 | 0.997 | −1.558 | 1.565 |

| Depressed mood‡ | −0.425 | 0.682 | .537 | −1.808 | 0.958 | −0.393 | 0.671 | .562 | −1.754 | 0.968 | −0.043 | 0.709 | 0.952 | −1.481 | 1.396 |

| Age | 0.026 | 0.014 | .078 | −0.003 | 0.055 | 0.032† | 0.014 | .030 | 0.003 | 0.060 | 0.023 | 0.015 | 0.123 | −0.007 | 0.054 |

| Race | 0.374 | 0.353 | .296 | −0.341 | 1.089 | 0.455 | 0.347 | .198 | −0.248 | 1.159 | 0.186 | 0.367 | 0.616 | −0.559 | 0.930 |

| Sex | 0.303 | 0.285 | .295 | −0.275 | 0.881 | 0.381 | 0.281 | .183 | −0.188 | 0.950 | 0.364 | 0.297 | 0.228 | −0.238 | 0.965 |

| Education | 0.051 | 0.054 | .354 | −0.059 | 0.160 | 0.054 | 0.053 | .312 | −0.053 | 0.162 | 0.019 | 0.056 | 0.735 | −0.095 | 0.133 |

| Married status | −0.643 | 0.350 | .075 | −1.353 | 0.067 | −0.758† | 0.344 | .034 | −1.457 | −0.060 | −0.291 | 0.364 | 0.428 | −1.029 | 0.446 |

| Comorbidities | 0.033 | 0.051 | .520 | −0.070 | 0.136 | 0.021 | 0.050 | .684 | −0.081 | 0.122 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.378 | −0.060 | 0.155 |

| Employee status | 0.856† | 0.327 | .013 | 0.192 | 1.519 | 0.834‡ | 0.322 | .014 | 0.181 | 1.488 | 0.835† | 0.342 | 0.019 | 0.143 | 1.528 |

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | |||||||||

| AR(1) | 0.161 | 0.105 | 0.216 | 0.167 | 0.109 | 0.223 | 0.110 | 0.053 | 0.166 | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.807 | 0.632 | 1.031 | 0.796 | 0.624 | 1.016 | 0.850 | 0.660 | 1.094 | ||||||

| Residual | 0.858 | 0.825 | 0.892 | 0.816 | 0.784 | 0.848 | 0.780 | 0.750 | 0.810 | ||||||

NOTE. References for categorical variables: sex: men = 0, women = 1; race: black = 0, white = 1; married status: unmarried = 0, married = 1; employment status: unemployed = 0, employed = 1.

Person-centered variable representing deviation (change) from an individual’s average.

Significance level was set at P<.05.

Each individual’s average of EMA values over the 2-week-long monitoring period.

Lagged associations: social interactions as predictors of next-survey symptoms

Table 4 shows all MLM results in which social interactions predicted symptoms on the next survey after controlling for covariates. Social success at one time point was significantly associated with pain at the next time point. Over the 2-week period, higher average social satisfaction, confidence, and success were associated with lower momentary fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood. In addition, in the models with pain and fatigue, a 1-unit increase in comorbidities was associated with a 0.107-point increase in pain and a 0.066-point increase in fatigue.

Table 4.

Lagged associations between social interaction variables and symptoms controlling for covariates (dependent variable = symptoms)

| Models |

Social Satisfaction |

Social Confidence |

Social Success |

|||||||||

| pain |

pain |

pain |

||||||||||

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1343) | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 3.377 | 0.714 | <.001 | 3.289 | 0.717 | <.001 | 3.337 | 0.711 | <.001 | |||

| Social satisfaction* | 0.023 | 0.015 | .121 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence* | NA | NA | NA | 0.023 | 0.016 | .148 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.054† | 0.017 | .001 | |||

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Social satisfaction‡ | −0.115 | 0.082 | .165 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence‡ | NA | NA | NA | −0.100 | 0.089 | .265 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.103 | 0.078 | .192 | |||

| Age | −0.017 | 0.009 | .051 | −0.017 | 0.009 | .058 | −0.018 | 0.008 | .044 | |||

| Race | −0.079 | 0.209 | .707 | −0.089 | 0.211 | .676 | −0.085 | 0.209 | .687 | |||

| Sex | 0.031 | 0.167 | .853 | 0.038 | 0.168 | .820 | 0.023 | 0.167 | .891 | |||

| Education | −0.035 | 0.033 | .296 | −0.035 | 0.034 | .305 | −0.036 | 0.034 | .296 | |||

| Married status | 0.280 | 0.205 | .180 | 0.285 | 0.210 | .183 | 0.289 | 0.204 | .164 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.107† | 0.027 | <.001 | 0.107* | 0.027 | <.001 | 0.107† | 0.027 | <.001 | |||

| Employee status | −0.156 | 0.214 | .472 | −0.169 | 0.218 | .443 | −0.167 | 0.213 | .438 | |||

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | ||||||

| AR(1) | 0.266 | 0.209 | 0.321 | 0.267 | 0.211 | 0.322 | 0.263 | 0.207 | 0.318 | |||

| Intercept | 0.510 | 0.402 | 0.646 | 0.514 | 0.405 | 0.651 | 0.511 | 0.403 | 0.647 | |||

| Residual | 0.481 | 0.461 | 0.501 | 0.481 | 0.461 | 0.501 | 0.479 | 0.460 | 0.500 | |||

| Models |

Fatigue |

Fatigue |

Fatigue |

|||||||||

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1343) | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 4.141† | 0.787 | <.001 | 4.019† | 0.805 | <.001 | 4.045† | 0.794 | <.001 | |||

| Social satisfaction* | 0.026 | 0.026 | .313 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence* | NA | NA | NA | 0.010 | 0.027 | .707 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.019 | 0.029 | .499 | |||

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Social satisfaction‡ | −0.361† | 0.090 | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence‡ | NA | NA | NA | ™0.360;† | 0.100 | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.329† | 0.087 | .001 | |||

| Age | −0.001 | 0.009 | .950 | 0.001 | 0.010 | .923 | −0.002 | 0.009 | .836 | |||

| Race | 0.071 | 0.230 | .758 | 0.060 | 0.236 | .801 | 0.049 | 0.233 | .834 | |||

| Sex | 0.331 | 0.184 | .080 | 0.357 | 0.189 | .067 | 0.313 | 0.187 | .101 | |||

| Education | −0.039 | 0.037 | .299 | −0.035 | 0.038 | .361 | −0.039 | 0.037 | .297 | |||

| Married status | 0.115 | 0.227 | .616 | 0.090 | 0.237 | .707 | 0.146 | 0.229 | .527 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.066† | 0.030 | .034 | 0.066† | 0.031 | .039 | 0.066† | 0.030 | .035 | |||

| Employee status | 0.074 | 0.236 | .755 | 0.073 | 0.244 | .767 | 0.050 | 0.238 | .835 | |||

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.553 | 0.434 | 0.706 | 0.569 | 0.446 | 0.726 | 0.562 | 0.441 | 0.717 | |||

| Residual | 0.803 | 0.773 | 0.834 | 0.803 | 0.773 | 0.834 | 0.803 | 0.773 | 0.834 | |||

| Models |

Social Satisfaction |

Social Confidence |

Social Success |

|||||||||

| Anxious Mood |

Anxious Mood |

Anxious Mood |

||||||||||

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1343) | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 2.483† | 0.566 | <.001 | 2.345† | 0.586 | <.001 | 2.433† | 0.566 | <.001 | |||

| Social satisfaction* | −0.005 | 0.015 | .735 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence* | NA | NA | NA | −0.018 | 0.015 | .250 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.021 | 0.016 | .189 | |||

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Social satisfaction‡ | −0.240† | 0.065 | .001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence‡ | NA | NA | NA | −0.224† | 0.073 | .004 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.223† | 0.062 | .001 | |||

| Age | 0.003 | 0.007 | .626 | 0.004 | 0.007 | .585 | 0.002 | 0.007 | .719 | |||

| Race | −0.213 | 0.166 | .207 | −0.224 | 0.172 | .201 | −0.223 | 0.166 | .186 | |||

| Sex | −0.058 | 0.132 | .665 | −0.043 | 0.138 | .754 | −0.068 | 0.133 | .612 | |||

| Education | 0.007 | 0.027 | .800 | 0.009 | 0.028 | .755 | 0.007 | 0.027 | .803 | |||

| Married | −0.031 | 0.163 | .849 | −0.040 | 0.172 | .819 | −0.012 | 0.163 | .944 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.019 | 0.022 | .389 | 0.018 | 0.022 | .414 | 0.019 | 0.022 | .387 | |||

| Employee status | 0.125 | 0.170 | .465 | 0.112 | 0.178 | .533 | 0.109 | 0.170 | .524 | |||

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | Estimation | 95% CI | ||||||

| AR(1) | 0.181 | 0.124 | 0.238 | 0.180 | 0.123 | 0.236 | 0.403 | 0.317 | 0.511 | |||

| Intercept | 0.400 | 0.316 | 0.508 | 0.418 | 0.329 | 0.530 | 0.180 | 0.123 | 0.236 | |||

| Residual | 0.460 | 0.442 | 0.478 | 0.459 | 0.441 | 0.478 | 0.459 | 0.441 | 0.478 | |||

| Models |

Depressed Mood |

Depressed Mood |

Depressed Mood |

|||||||||

| Fixed Effects | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | Estimation | SE | P Value | |||

| Within-Person Variables (Time Varying) (df = 1343) | ||||||||||||

| Intercept | 2.732† | 0.547 | <.001 | 2.650† | 0.558 | <.001 | 2.786† | 0.575 | <.001 | |||

| Social satisfaction* | 0.007 | 0.013 | .573 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence* | NA | NA | NA | −0.004 | 0.013 | .753 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success* | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.009 | 0.014 | .533 | |||

| Between-Person Variables (Time Invariant) (df = 39) | ||||||||||||

| Social satisfaction‡ | −0.217† | 0.063 | .001 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social confidence‡ | NA | NA | NA | −0.215† | 0.069 | .004 | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Social success‡ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | −0.191† | 0.061 | .003 | |||

| Age | −0.002 | 0.006 | .764 | −0.001 | 0.007 | .875 | −0.003 | 0.007 | .652 | |||

| Race | −0.119 | 0.160 | .463 | −0.125 | 0.164 | .451 | −0.133 | 0.163 | .420 | |||

| Sex | −0.095 | 0.128 | .462 | −0.080 | 0.131 | .544 | −0.105 | 0.130 | .427 | |||

| Education | −0.002 | 0.026 | .930 | 0.000 | 0.026 | .999 | −0.003 | 0.026 | .911 | |||

| Married status | −0.149 | 0.157 | .349 | −0.165 | 0.164 | .320 | −0.124 | 0.159 | .441 | |||

| Comorbidities | 0.035 | 0.021 | .101 | 0.035 | 0.021 | .109 | 0.035 | 0.021 | .107 | |||

| Employee status | 0.132 | 0.164 | .426 | 0.130 | 0.169 | .446 | 0.109 | 0.167 | .516 | |||

| Random Effects | Estimation | 95% Cl | Estimation | 95% Cl | Estimation | 95% Cl | ||||||

| AR(1) | 0.175 | 0.119 | 0.230 | 0.172 | 0.116 | 0.227 | 0.168 | 0.111 | 0.223 | |||

| Intercept | 0.391 | 0.309 | 0.495 | 0.401 | 0.316 | 0.508 | 0.400 | 0.315 | 0.506 | |||

| Residual | 0.400 | 0.385 | 0.416 | 0.400 | 0.384 | 0.416 | 0.399 | 0.384 | 0.415 | |||

NOTE. References for categorical, variables: sex: men = 0, women = l; race: black = 0, white = l; married status: unmarried = 0, married = l; employment status: unemployed = 0, employed = l.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Person-centered variable representing deviation (change) from an individual’s average.

Significance Level was set at P<.05.

Each individual’s average of EMA values over the 2-week-long monitoring period.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine real-time associations between social interactions and pain, fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood after stroke. Relationships were analyzed at concurrent and consecutive time points to explore predictive factors in either direction. The majority of findings were in the expected direction, with increased depressed mood, anxious mood, and fatigue being variously associated with decreased ratings in social confidence, satisfaction, and success at the concurrent time point. In lagged associations with symptoms as predictors, most within-person effects found in concurrent models had disappeared, and only anxious mood was related to social confidence. In addition, higher average social confidence was observed in participants who were unmarried and older, whereas higher social interactions were associated with being employed. In lagged associations with social interactions as predictors, higher average social interactions were related to lower momentary fatigue, anxious mood, and depressed mood at the subsequent time point. Increased comorbidities predicted increased subsequent somatic symptoms but not mood symptoms.

The finding that increased average fatigue was associated with decreased momentary social satisfaction, confidence, and success at the concurrent and subsequent time points is consistent with the associations Muina-Lopez and Guidon34 identified between poststroke fatigue and self-efficacy, which includes confidence in one’s success in social environments. Another finding of the current study was that increased anxious mood was associated with decreased social confidence at the next time point, a relationship not observed in concurrent measurement. Conversely, we found significant concurrent associations between depressed mood and social interactions but not in the lagged analysis. Thus, depressed mood may have a more immediate effect on social interactions than anxious mood, a finding that may critically inform the development of novel interventions. The present finding that depressed and anxious mood can have discrete and differing effects on social interactions within hours highlights the need for investigation of more immediate interventions based on momentary self-report of symptoms by individuals with stroke. Nevertheless, we should interpret these results cautiously, because they might be complicated by heterogeneous inclusion criteria (eg, diagnosis of anxiety disorder vs emotional distress or anxious symptoms).35

Employed participants had greater social interactions. Employment may offer increased opportunities for social interactions, both in the workplace and outside of work, with meaningful benefit to workers’ health.36 Work may also be tied to greater financial wellbeing, which contributes to greater choice in social activities.37 An increased number of comorbidities was associated with increased momentary pain and fatigue, but not with mood symptoms. These findings are consistent with those of Chen and Marsh,38 who found that medications and other factors relating to specific comorbidities may contribute to fatigue and that poststroke fatigue and mood disorders may occur independently of one another.

Consistent with the adverse effects of social isolation on physiological and mental health,1 the overall between-person analysis showed that, when social interactions improved, momentary anxious mood, depressed mood, and fatigue decreased at the subsequent time point. This finding highlights a valuable role for social interactions as a potential alleviator of several unique poststroke symptoms in a matter of hours. Interestingly, previous social success predicted an increase in pain at the next time point, which was the only observed result in an unexpected direction and one that may warrant further investigation.

The results of this study support the measurement of social interactions in terms of both quantity and quality. An individual may spend much of their time interacting with others without experiencing rich, quality relationships, and another may have infrequent but highly rewarding interactions. In the present study, we measured not only the frequency of social interactions, but also the individual’s self-appraisal of confidence, satisfaction, and success with each interaction.

Clinical implications

The dynamic relationships between decreased social interactions and increased mood and somatic symptoms observed in this study indicate a need for interventions that can interrupt momentary patterns in which adverse conditions feed into one another. For example, increased fatigue was associated with decreases in social factors, at both concurrent and subsequent points in time, and increased overall appraisals of social interactions predicted a reduction in fatigue at the subsequent time point. Energy conservation techniques may be instrumental in improving fatigue and social interactions for individuals with mild stroke. Depressed mood, a factor commonly associated with social isolation, may be a target of intervention both preemptively and in real time, as symptoms occur.

Ecological momentary interventions (EMI), delivered in real time in response to targeted symptoms and situations, may be a future direction for stroke rehabilitation. EMI has been used in numerous interventions, including smoking cessation,39 nutrition,40 psychology,41 and general mental health, including depression and anxiety.42 In a mild stroke population, EMI has the potential to address chronic symptoms that frequently interfere with daily life and maintenance of valued prestroke roles and routines. EMI can facilitate recognition of triggers that contribute to reduced social interactions or exacerbate somatic and mood symptoms. This increased awareness can empower individuals with stroke to manage their activities.

Study limitations

The current study did not collect data on household size, a factor that may affect social interactions. Environmental factors, such as social attitudes and built environments, not included in the study may also contribute to social isolation.43 Limitations to functional independence may limit employment and transportation options, restricting maintenance of prestroke social relationships. Both the quality and quantity of available social support may affect opportunities for social interactions after stroke.44 Future research should include these factors to better understand their effect on poststroke outcomes. The sample size for this study limits generalizability, but given the robust data collected with intensive measurement, we are confident that these preliminary data provide a valuable addition to the literature. Last, we applied multiple MLM analyses to address our research questions. Multiple testing procedures are likely to increase the probability of committing a type I error. Future studies should include a larger sample size to reduce the risk of this error. A strength of our study is that almost half of our sample was black, increasing the generalizability of findings to diverse populations. Our findings may identify targets for interventions to alleviate social isolation and the physical and mental health issues to which they contribute.

Conclusions

The current study provides preliminary evidence of temporal relationships between social interactions and symptoms in individuals with mild stroke. More research is needed to describe these relationships in larger samples to develop effective interventions to interrupt patterns of symptoms and social isolation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Megen Devine, MA, at Washington University for her editorial assistance with this manuscript. We also thank the graduate students and other research personnel at Washington University for their assistance in data collection.

This research was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (award no. TL1TR002344). This work was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development/National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (award no. K01HD095388). The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the policies of the funding agencies. We certify that all financial and material support for this research is clearly identified in the manuscript.

List of abbreviations:

- EMA

ecological momentary assessment

- EMI

ecological momentary intervention

- MLM

multilevel modeling

Suppliers

Apple Inc.

status/post; Christopher Metts.

RStudio, version 1.1463; RStudio.

Disclosures: none.

References

- 1.Leigh-Hunt N, Bagguley D, Bash K, et al. An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health 2017;152:157–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuller KA, Jarrett B, DeVries AC. Stress and social isolation increase vulnerability to stroke. Exp Neurol 2012;233:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Umberson D, Karas Montez J. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51:S54–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC. Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci 2009;13:447–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ouimet M, Primeau F, Cole M. Psychosocial risk factors in poststroke depression: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry 2001;46:819–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawton A, Green C, Dickens AP, et al. The impact of social isolation on the health status and health-related quality of life of older people. Qual Life Res 2011;20:57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci 2015;10:227–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Jaegher H, Di Paolo E, Gallagher S. Can social interaction constitute social cognition? Trends Cogn Sci 2010;14:441–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trigg R, Wood VA, Hewer RL. Social reintegration after stroke: the first stages in the development of the Subjective Index of Physical and Social Outcome (SIPSO). Clin Rehabil 1999;13:341–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwok T, Lo RS, Wong E, Wai-Kwong T, Mok V, Kai-Sing W. Quality of life of stroke survivors: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1177–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delpont B, Blanc C, Osseby G, Hervieu-Bègue M, Giroud M, Béjot Y. Pain after stroke: a review. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2018;174:671–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westerlind E, Singh R, Persson HC, Sunnerhagen KS. Experienced pain after stroke: a cross-sectional 5-year follow-up study. BMC Neurol 2020;20:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cumming TB, Blomstrand C, Skoog I, Linden T. The high prevalence of anxiety disorders after stroke. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016;24: 154–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-stroke depression: a review. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173:221–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angelelli P, Paolucci S, Bivona U, et al. Development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in poststroke patients: a cross-sectional study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;110:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu S, Mead G, Macleod M, Chalder T. Model of understanding fatigue after stroke. Stroke 2015;46:893–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narushima K, Robinson RG. Stroke-related depression. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2002;4:296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myin-Germeys I, Kasanova Z, Vaessen T, et al. Experience sampling methodology in mental health research: new insights and technical developments. World Psychiatry 2018;17:123–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jean FA, Swendsen JD, Sibon I, Fehér K, Husky M. Daily life behaviors and depression risk following stroke: a preliminary study using ecological momentary assessment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2013;26:138–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazure CM, Weinberger AH, Pittman B, Sibon I, Swendsen J. Gender and stress in predicting depressive symptoms following stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;38:240–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kratz AL, Murphy SL, Braley TJ. Ecological momentary assessment of pain, fatigue, depressive, and cognitive symptoms reveals significant daily variability in multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:2142–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paolillo EW, Tang B, Depp CA, et al. Temporal associations between social activity and mood, fatigue, and pain in older adults with HIV: an ecological momentary assessment study. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5:e38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enderby PM, Wood VA, Wade DT, Hewer RL. The Frenchay Aphasia Screening Test: a short, simple test for aphasia appropriate for nonspecialists. Int Rehabil Med 1986;8:166–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanbellingen T, Kersten B, Van de Winckel A, et al. A new bedside test of gestures in stroke: the apraxia screen of TULIA (AST). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011;82:389–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedman PJ. The star cancellation test in acute stroke. Clin Rehabil 1992;6:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey IL, Lovie JE. New design principles for visual acuity letter charts. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1976;53:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Finch WH, Bolin JE, Kelley K. Multilevel modeling using R. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diggle P, Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-Y, Heagerty PJ, Zeger S. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Little RJ. Modeling the drop-out mechanism in repeated-measures studies. J Am Stat Assoc 1995;90:1112–21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gallop R, Tasca GA. Multilevel modeling of longitudinal data for psychotherapy researchers: II. The complexities. Psychother Res 2009;19:438–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Enders CK, Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: a new look at an old issue. Psychol Methods 2007; 12:121–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muina-Lopez R, Guidon M. Impact of post-stroke fatigue on self-efficacy and functional ability. Eur J Physiother 2013;15:86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chun H-YY, Newman R, Whiteley WN, Dennis M, Mead GE, Carson AJ. A systematic review of anxiety interventions in stroke and acquired brain injury: efficacy and trial design. J Psychosom Res 2018;104:65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buunk BP, Verhoeven K. Companionship and support at work: a microanalysis of the stress-reducing features of social interaction. Basic Appl Soc Psych 1991;12:243–58. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Callander E, Schofield DJ. The relationship between employment and social participation among Australians with a disabling chronic health condition: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2013;3: e002054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen K, Marsh EB. Chronic post-stroke fatigue: it may no longer be about the stroke itself. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2018;174:192–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Businelle MS, Ma P, Kendzor DE, Frank SG, Vidrine DJ, Wetter DW. An ecological momentary intervention for smoking cessation: evaluation of feasibility and effectiveness. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brookie KL, Mainvil LA, Carr AC, Vissers MC, Conner TS. The development and effectiveness of an ecological momentary intervention to increase daily fruit and vegetable consumption in low-consuming young adults. Appetite 2017;108:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Versluis A, Verkuil B, Spinhoven P, van der Ploeg MM, Brosschot JF. Changing mental health and positive psychological well-being using ecological momentary interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 2016;18:e152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schueller SM, Aguilera A, Mohr DC. Ecological momentary interventions for depression and anxiety. Depress Anxiety 2017;34: 540–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong AW, Ng S, Dashner J, et al. Relationships between environmental factors and participation in adults with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional multi-center study. Qual Life Res 2017;26:2633–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beckley MN. The influence of the quality and quantity of social support in the promotion of community participation following stroke. Aust Occup Ther J 2007;54:215–20. [Google Scholar]