Abstract

Impaired glucose metabolism in diabetes causes severe acute and long-term complications, making real-time detection of blood glucose indispensable for diabetic patients. Existing continuous glucose monitoring systems are unsuitable for long-term clinical glycemic management due to poor long-term stability. Polymer dot (Pdot) glucose transducers are implantable optical nanosensors that exhibit excellent brightness, sensitivity, selectivity, and biocompatibility. Here we show that hydrogen peroxide—a product of glucose oxidation in Pdot glucose sensors—degraded sensor performance via photobleaching, reduced glucose oxidase activity, and generated cytotoxicity. By adding catalase to a glucose oxidase-based Pdot sensor to create an enzymatic cascade, the hydrogen peroxide product of glucose oxidation is rapidly decomposed by catalase, preventing its accumulation and improving the sensor’s photostability, enzymatic activity, and biocompatibility. Thus, we present a next-generation Pdot glucose transducer with a multienzyme reaction system (Pdot-GOx/CAT) that provides excellent sensing characteristics as well as greater detection system stability. Pdot glucose transducers that incorporate this enzymatic cascade to eliminate hydrogen peroxide will possess greater long-term stability for improved continuous glucose monitoring in diabetic patients.

Keywords: semiconductor polymer dots, continuous glucose monitoring, diabetes, enzymatic cascade, long-term stability

Graphical Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide, as a product of glucose oxidation in Pdot glucose sensors, degraded sensor performance via photobleaching, reduced glucose oxidase activity, and generated cytotoxicity. By incorporating a biomimetic enzymatic cascade consisting of glucose oxidase and catalase, hydrogen peroxide produced during glucose oxidation is rapidly decomposed, greatly improving sensing characteristics and detection system stability of the Pdot glucose transducer.

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a common chronic disease caused by lack of insulin or proper insulin response resulting in disordered glucose metabolism.[1] Prolonged hyperglycemia can lead to serious damage to the heart, kidneys, eyes, and nervous system.[2] Because there is no effective cure for diabetes, tight control of blood glucose levels plays a crucial role in the prevention of complications.[3] The advent of a portable fingertip-prick blood glucose test promoted a shift to home self-testing, which improved glycemic management for diabetics.[4] However, the resulting intermittent glucose concentration information is insufficient for maintaining a healthy range of blood glucose levels for many diabetic patients.[5] Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) provides near real-time blood glucose concentration information to allow more precise and personalized clinical glycemic management.[6] CGM technology is of great significance for improving the prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of diabetes.[7]

CGM technologies are developing rapidly,[8] but almost all existing CGM systems are unsuitable for clinical glycemic management due to poor long-term stability of the detection system.[9] The most well-known CGM system is a subcutaneously implanted electrochemical device that uses an enzyme-coated amperometric sensor to measure glucose concentration in interstitial fluid in real time.[4] This device has several serious drawbacks that limit its clinical application, including the need for frequent electrode replacement due to surface fouling and degradation, and the need for multiple calibrations due to unpredictable signal drift, as well as pain and inflammation from the invasive implantation process.[10] Optical technology is poised to overcome these limitations and drive the development of the next generation of CGM sensors.[3a, 8g, 8h, 11] Semiconductor polymer dots (Pdots) are luminescent nanoparticles with great potential for applications in biological imaging and biosensing due to their brightness, photostability, and biocompatibility.[12] We recently described an optical glucose sensor (Pdot-GOx) that integrates an oxygen-sensing Pdot with the oxygen-consuming enzyme glucose oxidase.[13] We developed an ancillary image processing algorithm and smartphone application software to build a flexible, miniaturized optical detection platform with the advantages of mobile network platforms.[14] However, maintaining the stability of detection for a prolonged period remained a challenge. A key impediment to prolonged stability is hydrogen peroxide, a potentially harmful byproduct of glucose oxidation that is often neglected in glucose sensor applications.

In our Pdot-GOx system, hydrogen peroxide is continuously generated by the glucose oxidation reaction and accumulates around the Pdot transducer. Hydrogen peroxide is an ubiquitous metabolite, and its biological functions depend on its concentration.[15] At physiological levels, hydrogen peroxide is important in cell signal transduction and metabolism, but at higher levels, it has long been recognized as a destructive molecule that can cause non-specific oxidative damage to cells and tissues by attacking proteins, lipids, and DNA.[16] To prevent such oxidative damage, cells use catalase (CAT) after some enzymatic metabolic reactions to catalyze the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into oxygen and water.[16a] Such multienzyme reactions or “enzymatic cascades” provide spatiotemporal control of metabolism in biological systems.[17] Inspired by the ingenuity of this natural system, many researchers in the field of biocatalysis have focused on enzymatic cascades.[18] In this study, we examine the effects of hydrogen peroxide on Pdot glucose transducers and show that hydrogen peroxide degrades sensor performance via photobleaching, reduced glucose oxidase activity, and generated cytotoxicity. By incorporating a biomimetic enzymatic cascade consisting of glucose oxidase and catalase, hydrogen peroxide produced during glucose oxidation is rapidly decomposed, preventing its accumulation and improving the sensor’s photostability, enzymatic activity, and biocompatibility. However, oxygen produced by catalase also can interfere with sensing by the Pdot transducer, because the sensing mechanism is based on detecting the glucose-oxidase/glucose-induced local depletion of oxygen concentration which the Pdot-oxygen sensor measures. Here, we systematically characterize each of these potential effects on the function of Pdot transducer, and present a Pdot glucose transducer with a multienzyme reaction system (Pdot-GOx/CAT) that provides excellent sensing characteristics as well as greater detection system stability for improved long-term continuous glucose monitoring.

2. Results and Discussion

The Pdot-GOx sensor consists of the oxygen-consuming enzyme glucose oxidase and an oxygen-sensing fluorescent semiconducting polymer dot.[13] Depletion of oxygen during glucose oxidation causes an increase in Pdot luminescence intensity. A continuous transdermal optical output signal from a subcutaneously implanted Pdot-GOx transducer provides a real-time indicator of blood glucose level (Scheme 1). The oxygen-sensing Pdot is composed of the fluorescent semiconducting polymer poly(9,9-dihexylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl) (PDHF) doped with the oxygen-sensitive material palladium(II) meso-tetra(pentafluorophenyl) porphine (PdTFPP). The UV-Vis absorption spectrum of the PdTFPP-doped PDHF Pdot exhibits a peak at 380 nm from the PDHF polymer (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Upon UV excitation, the emission spectrum shows a blue fluorescence peak at 425 nm from PDHF, and a red phosphorescence peak at 672 nm from PdTFPP (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Bioconjugation of the oxygen-sensing Pdot with glucose oxidase produces the Pdot-GOx glucose transducer (Figure S1, Supporting Information). Figure 1a shows the significantly different emission spectra of the Pdot-GOx transducer at different glucose concentrations. The red phosphorescence centered at 672 nm is sensitive to glucose; the blue fluorescence centered at 425 nm remains unchanged. The ratio of emission intensities at these two peak wavelengths (I672/I425) provides a ratiometric system for high-precision quantitative detection of glucose. The I672/I425 ratio exhibits a linear relationship (R2 > 0.99) with glucose concentration in the physiological blood glucose range (4–16 mM) (Figure 1b). Due to the specificity of glucose oxidase, the Pdot-GOx sensor possesses high selectivity with respect to other carbohydrate molecules. Based on this high sensitivity and selectivity, the Pdot-GOx transducer is a promising implantable optical glucose sensor. However, hydrogen peroxide produced during glucose oxidation may degrade the long-term accuracy of the detection system; therefore, we investigate the effect of added hydrogen peroxide on sensor characteristics.

Scheme 1.

Schematic of the Pdot-GOx/CAT glucose transducer. Glucose oxidase (GOx) catalyzes the oxidation of glucose, causing depletion of oxygen which increases the luminescence intensity of the Pdot, allowing glucose sensing. Catalase catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, preventing its accumulation and subsequent loss of photostability, enzymatic activity, and biocompatibility of the detection system. However, oxygen produced by the catalase reaction can interfere with oxygen sensing by Pdot and reduce the sensitivity of the Pdot transducer to glucose.

Figure 1.

Luminescence response of Pdot-GOx transducer to glucose with and without exogenous H2O2. a) Luminescence spectra of Pdot-GOx transducer in HEPES buffer pH 7.4 at various glucose concentrations. b) The emission ratio I672/I425 as a function of glucose concentration with and without exogenous hydrogen peroxide at 100 mM. The curves show a linear relationship (R2 > 0.99) over the physiologically relevant range (4–16 mM). The calibration curve slope decreased ~25% with the addition of 100 mM hydrogen peroxide. c) Response curves of the Pdot-GOx transducer following addition of 20 mM glucose in the presence of different concentrations of exogenous hydrogen peroxide.

To evaluate the impact of hydrogen peroxide on the Pdot-GOx transducer, we added exogenous hydrogen peroxide to simulate its accumulation around the sensor. Addition of 100 mM H2O2 to the Pdot-GOx solution caused an intense change in sensing properties, with ~25% reduction of the slope of the calibration curve (change in I672/I425 versus glucose concentration) (Figure 1b). Although the emission intensity ratio was still linearly related to glucose concentration over the physiological range, unpredictable calibration-curve deviations severely affect the stability of detection, and in practical applications will lead to the need for frequent calibration and replacement of the transducer. Figure 1c shows the glucose response curves of the Pdot-GOx transducer at different concentrations of added H2O2. With no added H2O2, 20 mM glucose causes the emission ratio to increase and reach a plateau when the dissolved oxygen is completely depleted. This glucose response is fast (<5 min) and exhibits a strong phosphorescence enhancement. However, this responsiveness declines with increasing added H2O2 concentration, manifested by a slower response and a lower emission ratio enhancement.

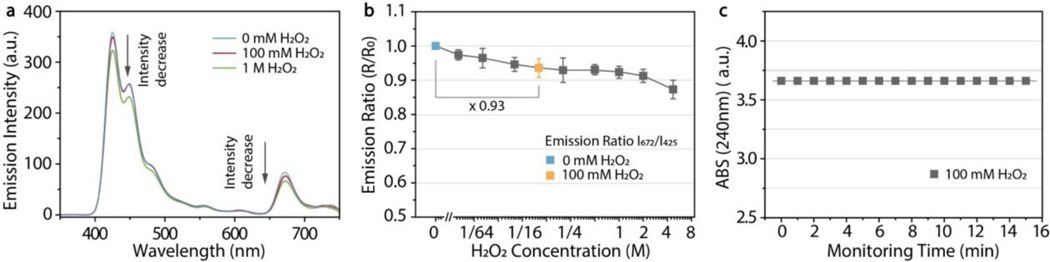

The sensing degradation by H2O2 shown in Figure 1 may be caused by photobleaching and/or reduction of enzymatic activity. Photostability is critical for long-term use of optical transducers in glucose monitoring. We previously showed that PdTFPP-doped Pdots exhibit superior photostability due to the TFPP ligand relative to other porphyrin dye ligands such as platinum(II) octaethylporphyrin (PtOEP).[14] Here we incubated the PdTFPP-doped PDHF Pdot-GOx sensor with hydrogen peroxide at 100 mM or 1 M, and observed luminescence decay at the blue and red emission peaks (Figure 2a). The Pdots showed a monotonic decrease in emission ratio with increasing H2O2 concentration (Figure 2b). At 100 mM H2O2, the emission intensity ratio of Pdots was reduced by ~7% (indicated by the blue and orange squares in Figure 2b). This slight signal drift causes a failure of the internal reference calibration system which can be amplified by fluctuations in excitation changes or in detection changes, causing serious measurement errors and a loss of test accuracy during glucose monitoring. We tested whether spontaneous decomposition of hydrogen peroxide could have caused the reduced emission ratio. For H2O2 at 100 mM, the absorbance at 240 nm remained constant for 15 min at room temperature without catalyst, indicating minimal decomposition (Figure 2c). Therefore, the decrease in emission ratio is not due to H2O2 decomposition and is more likely due to photobleaching caused by the strong oxidizing effect of hydrogen peroxide on the organic luminophores.

Figure 2.

Effect of hydrogen peroxide on photostability of the Pdot-GOx transducer. a) Luminescence emission spectra of the Pdots at 0, 100 mM, and 1 M H2O2, showing a reduction in emission intensity with addition of H2O2. b) The phosphorescence/fluorescence emission ratio I672/I425 of the Pdots decreases monotonically with increasing H2O2 concentration, likely due to photobleaching. Error bars represent standard deviations of three measurements. c) Absorbance at 240 nm of hydrogen peroxide (100 mM) for 15 min at room temperature without catalyst, indicating minimal spontaneous decomposition of hydrogen peroxide.

A key part of the glucose sensing system is the glucose oxidase-catalyzed reaction of glucose with O2 to produce glucono-δ-lactone and H2O2.[19] Enzyme catalysis allows faster reactions and greater specificity than chemical catalysis, but is vulnerable to factors that reduce enzyme activity such as pH, temperature, enzyme concentration, substrate concentration, and inhibitors.[20] Enzymatic activity can be evaluated by measuring the increase in product concentration or the decrease in substrate concentration over time. We measured the decrease in dissolved oxygen in real time using a dissolved-oxygen meter in a vessel filled with buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 10 mM glucose and 10 nM glucose oxidase (GOx) (Figure 3a). The oxygen consumption rate was 1.03 μMs−1, calculated as slope of the linear portion of the oxygen concentration versus time curve. To determine the effect of accumulated hydrogen peroxide on glucose oxidase activity, we monitored oxygen consumption in the presence of the same concentrations of glucose (10 mM) and glucose oxidase (10 nM), but added 100 mM H2O2 (Figure 3a). The oxygen consumption rate decreased to 0.88 μMs−1, a reduction of ~15%, which we attribute mainly to reduced glucose oxidase activity. The initial kinetics of glucose oxidase-catalyzed reaction were determined by adding different concentrations of glucose to 10 nM glucose oxidase in HEPES (Figure S2, Supporting Information). The Michaelis constant (KM) of 14.36 ± 1.94 mM and maximum reaction rate (Vmax) of 2.53 ± 0.18 μMs−1 were determined by plotting the rate of reaction (V) versus the substrate concentration (S), which follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Figure S2b, Supporting Information). Addition of 100 mM H2O2 caused an increase in KM (18.34 ± 4.84 mM) with a smaller change in Vmax (2.57 ± 0.39 μMs−1), indicating competitive inhibition of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction by hydrogen peroxide. Using Lineweaver–Burk plots, the competitive inhibition is readily observed (Figure 3b). This inhibition is caused by the similar chemical structures of the inhibitor (H2O2) and the substrate (O2), which leads to competition for binding at the enzyme active site.[20] Equation 1 shows the mechanism of glucose oxidase-catalyzed glucose oxidation inhibited competitively by hydrogen peroxide:

| (1) |

where G is glucose, FAD is the cofactor flavin adenine dinucleotide, and FAD·H2 is reduced FAD. Hydrogen peroxide acts as a competitive inhibitor by competing with O2 and reacting with FAD·H2 to produce a dead-end complex (FAD·H2·H2O2).[21] These results demonstrate that accumulated hydrogen peroxide produced during glucose oxidation could inhibit glucose oxidase activity, leading to the reduced Pdot-transducer responsiveness shown in Figure 1.

Figure 3.

Inhibitory effect of hydrogen peroxide on catalytic activity of glucose oxidase. a) Decay curves of oxygen concentration were determined by using a dissolved-oxygen meter in a vessel filled with 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 10 nM GOx and 10 mM glucose, in the absence (green) and presence (red) of 100 mM hydrogen peroxide. b) Lineweaver–Burk plots in the absence (green) and presence (red) of hydrogen peroxide, indicating competitive inhibition of glucose oxidase by hydrogen peroxide. c) Oxygen consumption rate (10 nM GOx, 20 mM glucose) at different ratios of catalase to glucose oxidase concentration. All reactions converge to a new reaction equilibrium state in which the hydrogen peroxide decomposition rate is equal to the product rate.

Hydrogen peroxide is a common metabolic byproduct in aerobic metabolism. At physiological levels, hydrogen peroxide is involved in the transmission of intracellular signals; at higher levels, hydrogen peroxide is associated with oxidative damage to cells and tissues. To prevent such damage, cells use catalase to mediate an additional enzymatic reaction, the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen. To mimic this natural multienzyme cascade, we added catalase to our Pdot-GOx sensor, so that a catalase-catalyzed H2O2 decomposition reaction would rapidly remove hydrogen peroxide produced during glucose oxidation. As a result, when the hydrogen peroxide is completely decomposed, a new reaction equilibrium will be re-established as follows (Equation 2):

| (2) |

To determine the optimal amount of added catalase, we introduced different concentrations of catalase into the glucose oxidase-catalyzed reaction (10 nM GOx, 20 mM glucose) (Figure 3c). Increasing the amount of catalase accelerates the conversion of H2O2 into water and oxygen, thus reducing the oxygen consumption rate (Figure S2, Supporting Information). We measured the kinetics of oxygen consumption, and found that the maximum reaction rates at 0, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 200 nM catalase ([CAT]/[GOx] ratios of 0, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20) were 1.46, 1.13, 0.96, 0.83, 0.83, and 0.84 μMs−1, respectively (Figure 3c). All of these reactions converge to a steady state in which the H2O2 decomposition rate is equal to the production rate. When the hydrogen peroxide product is completely depleted, the oxygen consumption rate decreases by nearly half in the presence of same concentration of glucose (Equation 2).

Biocompatibility is an essential property of CGM sensors. First, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the PdTFPP-doped PDHF Pdots alone (without GOx) at various concentrations (0–100 ppm) for 24 h using HeLa cells, and observed no loss of cell viability and no morphological change (Figure S3, Supporting Information). However, even a small amount of glucose oxidase (1 nM) can cause significant cytotoxicity (~50% cell mortality) due to hydrogen peroxide generated during glucose oxidation (Figure 4a). Hydrogen peroxide is a common reactive oxygen species (ROS) and a potent cytotoxin, which is why it has attracted attention in the field of tumor therapy.[22] When we added catalase at different concentrations to 10 nM GOx in HeLa cell medium, cytotoxicity was reduced with increasing [CAT] (Figure 4b). Addition of 50 nM CAT to 10 nM GOx (final concentrations) causes a cell morphological change versus 10 nM GOx alone (Figure 4c). A molar concentration ratio of CAT to GOx of 5-fold or more resulted in nearly 100% cell viability without morphological change. We have obtained similar experimental results using another commonly used cell line, MCF-7 cells, which confirm the generality of the results (Figure S4, Supporting Information). These results suggested that addition of catalase to a glucose oxidase-based sensor to create a multienzyme reaction system could prevent cytotoxicity due to accumulation of hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 4.

Catalase reduces the cytotoxicity of glucose oxidase. a) HeLa cells were incubated with GOx at different concentrations for 24 h, showing significant cell cytotoxicity above 0.5 nM GOx. b) HeLa cells were incubated with GOx and catalase (CAT) at different concentration ratios for 24 h ([GOx] = 10 nM), showing reduction of cytotoxicity by catalase. c) Cell morphological images in presence of GOx alone (10 nM; left) or with catalase (10 nM GOx, 50 nM CAT; right), acquired using an optical microscope. Scale bar, 50 μm. Error bars represent standard deviations of three separate measurements.

To characterize the sensing properties of the Pdot-GOx/CAT glucose transducer, we measured the emission ratio (I672/I425) as function of time at different CAT to GOx concentration ratios ([GOx] = 10 nM) in the presence of 20 mM glucose (Figure 5a). As expected, as the amount of catalase increased (and the oxygen consumption rate decreased), the glucose response of the Pdot transducer slowed down. When amount of catalase reached 5-fold that of glucose oxidase, the glucose response curves converged to a new equilibrium state. At this time, in the presence of the same concentration of glucose, the response rate of Pdot-GOx/CAT (10 nM GOx, 50 nM CAT) was roughly half that of Pdot-GOx (10 nM). Since the response is primarily determined by glucose diffusion and enzymatic reactions, the dynamic response range and response speed can be tuned by varying the molar ratio of enzyme coated on the Pdot surface in the bioconjugation reaction. The Pdot-GOx/CAT glucose transducer exhibited a significant increase in emission intensity with increasing glucose (from 0–20 mM) (Figure 5b). By measuring the I672/I425 emission ratio, the Pdot-GOx/CAT sensor was highly sensitive to glucose in the physiological blood glucose range (4–16 mM) (Figure 5c), with comparable results to the Pdot-GOx sensor. Moreover, we also measured the change in sensor emission as glucose level was varied repeatedly. Here, hydrogel beads loaded with Pdot transducer were washed with PBS and then exposed to various glucose concentrations. The sensor’s response remained unchanged for at least 5 repetitive measurements (Figure S5, Supporting Information). These results indicate that the Pdot-GOx/CAT glucose transducer maintains excellent sensing characteristics while also improving the long-term sensing stability by incorporating a multienzyme cascade which eliminates hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 5.

Performance of Pdot-GOx/CAT glucose transducer. a) Glucose response curves of Pdot-GOx/CAT transducer at different CAT to GOx concentration ratios ([GOx] = 10 nM) in the presence of 20 mM glucose. b) Luminescence spectra of Pdot-GOx/CAT ([CAT]/[GOx] = 5) at various concentrations of glucose in HEPES pH 7.4. c) Emission ratio of Pdot-GOx/CAT ([CAT]/[GOx] = 5) as a function of glucose concentration, showing a linear relationship (R2 > 0.99) in the physiologically relevant range (4–16 mM).

3. Conclusion

In this work, we developed an enzyme cascade reaction system containing glucose oxidase and catalase to enhance the long-term stability of a polymer dot glucose transducer for use in continuous glucose monitoring. Hydrogen peroxide is a byproduct of the glucose oxidation reaction and is continuously generated and accumulated around glucose oxidase-based Pdots. By examining the effects of hydrogen peroxide on the Pdot-GOx sensing system, we found that hydrogen peroxide causes Pdot photobleaching, inhibits the activity of glucose oxidase, and causes cytotoxicity, which will seriously affect the stability of detection for long-term glucose monitoring. By incorporating a bioinspired enzyme cascade consisting of glucose oxidase and catalase, the hydrogen peroxide product is rapidly decomposed, but in the process also generates oxygen that can inhibit the sensitivity of the Pdot transducer. By systematically studying this reaction cascade system as well as the sensitivity of the resultant Pdot transducer, we determined the optimal ratio of GOx/CAT for conjugation onto the Pdot surface. A Pdot glucose transducer modified with this multienzyme reaction system (Pdot-GOx/CAT) exhibited excellent sensing characteristics and improved photostability and enzyme activity, and reduced cytotoxicity. This strategy of using an enzyme cascade to eliminate harmful byproducts generated during enzyme-based biosensor reactions can be generalized to improve the long-term stability of a wide range of enzymatic Pdot transducers and biosensors.

4. Experimental Section

Materials:

The fluorescent semiconducting polymer poly(9,9-dihexylfluorenyl-2,7-diyl) (PDHF, Mw ~55,000), amphiphilic functional polymer poly(styrene-co-maleic anhydride) (PSMA, Mw ∼1,700), phosphorescent dye palladium(II) meso-tetra (pentafluorophenyl) porphine (PdTFPP), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent were purchased from Millipore Sigma. Glucose oxidase from Aspergillus niger (≥100,000 units/g protein, Mw ~160 kDa), catalase from bovine liver (2,000–5,000 units/mg protein, Mw ~250 kDa), 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide (EDC) were purchased from Millipore Sigma and stored at −20 °C. β-D-glucose and hydrogen peroxide (30 wt% in water) were also purchased from Millipore Sigma. HEPES and PBS buffers were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and stored at 4 °C. All chemical agents were used without further purification. All experiments were performed at room temperature unless otherwise indicated.

Preparation and bioconjugation of Pdot transducer:

Aqueous dispersions of the oxygen-sensing Pdot transducer were prepared by using the reprecipitation method described in our previous reports. Stock solutions of PDHF polymer (1 mg/mL), PSMA polymer (1 mg/mL), and PdTFPP (0.5 mg/mL) were diluted in THF to produce precursor mixture solutions. A 1-mL aliquot of the solution mixture consisting of PDHF (100 μg/mL), PSMA (10 μg/mL), and PdTFPP (10 μg/mL) was quickly added to 5 mL of Milli-Q water in a bath sonicator for 2 min. The Pdot suspension solution was heated on a hot plate (~90 °C) under a nitrogen atmosphere until THF solvent was completely removed. The solution was further concentrated to 2 mL on a hot plate and followed by filtration through a 0.2 μm filter. During nanoparticle formation, the maleic anhydride units of the PSMA polymer were hydrolyzed to carboxyl groups on the Pdots. According to the previous experimental protocol, by utilizing an EDC-catalyzed reaction between carboxyl and amine groups, the enzyme was conjugated to the surface of the Pdots. In this bioconjugation reaction, 20 μL of concentrated HEPES buffer (1 M, pH 7.4) was added to 1 mL of Pdot solution (50 μg/mL). The glucose oxidase and catalase were pre-mixed at a certain ratio, and 25 μL of the mixed enzyme solution was added to the homogeneous solution to participate in the reaction. Then, 20 μL of freshly prepared EDC solution (5 mg/mL) was added to the solution. The above mixture was left on a rotary shaker for 4 h at room temperature. The resulting Pdot bioconjugates were separated from free enzyme molecules by gel filtration using Sephacryl HR-400 gel media. Measurements of particle size and surface potential were used to confirm whether the enzyme was successful conjugated to the particle surface.

Spectroscopic characterization of Pdots:

Absorption spectra were obtained using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (DU 720 scanning spectrophotometer, Beckman Coulter, Inc., CA USA) and luminescent spectra were obtained using a fluorescence spectrophotometer (LS-55 fluorescence spectrophotometer, PerkinElmer, Inc., MA USA). To characterize Pdot sensing, different concentrations of glucose were added to a quartz cuvette containing the Pdot glucose transducer, and the luminescent spectra were measured once per minute for 10 min with excitation at 380 nm.

Enzymatic assays:

Oxygen consumption during glucose oxidation was measured by using a dissolved-oxygen meter (Mettler-Toledo, FiveGo F4) in air-saturated HEPES buffer (20 mM, pH 7.4) containing 10 nM glucose oxidase and various concentrations of glucose. The probe of the dissolved-oxygen meter was placed close to the bottom of a glass vessel filled with 30 mL of buffer solution. After the enzymatic reaction was triggered, the dissolved oxygen concentration was recorded every second until the oxygen was exhausted. The activity was calculated from the slope of the linear portion of the oxygen concentration versus time curve. To evaluate enzyme activity inhibition by hydrogen peroxide, hydrogen peroxide was added to the buffer solution at various concentrations before adding glucose.

Cytotoxicity and cell morphology:

HeLa cells (American type culture collection, VA USA) were used for cytotoxicity studies. The cells were cultured in an incubator (air/CO2 (95:5) atmosphere at 37 °C, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA USA) using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 μg/mL streptomycin, and 50 U/mL penicillin. For cytotoxicity experiments, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates at ~7,000 cells per well for 24 h. Pdots, GOx, and/or CAT were added to the cell culture medium, the cells were incubated for 24 h, and 20 μL MTT (5 mg/mL, 1x PBS) was added for 3 h. The medium was then removed and 150 μL DMSO solvent was added for 10 min with gentle shaking at room temperature. The absorbance at 490 nm was recorded using a microplate reader (BioTek Cytation3, USA). Cell viability was expressed as the ratio of abs (490 nm) with and without addition of Pdots, GOx, and/or CAT. For cell morphological imaging, ~1.5×104 cells were plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated glass-bottom culture dishes for 12 h, then Pdots, GOx, and/or CAT were added, and the cells were incubated for an additional 12 h. The cells were then washed three times with warm PBS buffer (1x, pH 7.4) before imaging. Cell morphological images were captured by using an inverted optical microscope (Olympus IX71, Japan) equipped with Andor iXon3 frame transfer EMCCD (Andor, UK). All biological reagents for cell experiments were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific and stored at 4 °C.

Statistics:

The statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism and Origin Pro software. The statistical data was plotted either as mean ± standard deviation or individual data points. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05. The photostability and cytotoxicity analysis were performed with three separate measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the University of Washington and the National Institutes of Health (R01MH113333). We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (KQTD20170810111314625), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81771930), and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFB0407200).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

J. Yu and D. T. Chiu have financial interest in Lamprogen, which has licensed the described technology from the University of Washington.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Kai Sun, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Zhaoyang Ding, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Jicheng Zhang, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Haobin Chen, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Yuling Qin, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Shihan Xu, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Prof. Changfeng Wu, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518055, China

Jiangbo Yu, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA.

Prof. Daniel T. Chiu, Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195, USA

References

- [1].a) IDF Diabetes Atlas, 9th ed., International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; [Google Scholar]; b) Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, Cavan D, Shaw JE, Makaroff LE, Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract 2017, 128, 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Care 2017, 40, S11;27979889 [Google Scholar]; b) Katsarou A, Gudbjörnsdottir S, Rawshani A, Dabelea D, Bonifacio E, Anderson BJ, Jacobsen LM, Schatz DA, Lernmark Å, Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2017, 3, 17016; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) De Fronzo RA, Ferrannini E, Groop L, Henry RR, Herman WH, Holst JJ, Hu FB, Kahn CR, Raz I, Shulman GI, Simonson DC, Testa MA, R. Weiss Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Veiseh O, Tang BC, Whitehead KA, Anderson DG, Langer R, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 45; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) American Diabetes Association, Diabetes Care 2019, 42, S61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Heller A, Feldman B, Chem. Rev 2008, 108, 2482; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wilson GS, Hu Y, Chem. Rev 2000, 100, 2693; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang J, Chem. Rev 2008, 108, 814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Boland E, Monsod T, Delucia M, Brandt CA, Fernando S, Tamborlane WV, Diabetes care 2001, 24, 1858; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Tamborlane WV, Beck RW, Bode BW, Buckingham B, Chase HP, Clemons R, Fiallo-Scharer R, Fox LA, Gilliam LK, Hirsch IB, Huang ES, Kollman C, Kowalski AJ, Laffel L, Lawrence JM, Lee J, Mauras N, O’Grady M, Ruedy KJ, Tansey M, Tsalikian E, Weinzimer S, Wilson DM, Wolpert H, Wysocki T, Xing D, N. Engl. J. Med 2008, 359, 1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Wolpert HA, N. Engl. J. Med 2010, 263, 383; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Waldron-Lynch F, Herold KC, Nat. Clin. Pract. Endocrinol. Metab 2009, 5, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N, Israeli D, Rothschild D, Weinberger A, Ben-Yacov O, Lador D, Avnit-Sagi T, Lotan-Pompan M, Suez J, Mahdi JA, Matot E, Malka G, Kosower N, Rein M, Zilberman-Schapira G, Dohnalova L, Pevsner-Fischer M, Bikovsky R, Halpern Z, Elinav E, Segal E, Cell 2015, 163, 1079; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Klonoff DC, Ahn D, Drincic A, Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract 2017, 133, 178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].a) Nichols SP, Koh A, Storm WL, Shin JH, Schoenfisch MH, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 2528; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nightingale AM, Leong CL, Burnish RA, Hassan SU, Zhang Y, Clough GF, Boutelle MG, Voegeli D, Niu X, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, 2741; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Park J, Kim J, Kim SY, Cheong WH, Jang J, Park YG, Na K, Kim YT, Heo JH, Lee CY, Lee4 JH, Bien F, Park JU, Sci. Adv 2018, 4, eaap9841; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gao W, Emaminejad S, Nyein HYY, Challa S, Chen K, Peck A, Fahad HM, Ota H, Shiraki H, Kiriya D, Lien DH, Brooks GA, Davis RW, Javey A, Nature 2016, 529, 509; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Lee H, Choi TK, Lee YB, Cho HR, Ghaffari R, Wang L, Choi HJ, Chung TD, Lu N, Hyeon T, Choi SH, Kim DH, Nat. Nanotechnol 2016, 11, 566; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Lu Y, Aimetti AA, Langer R, Gu Z, Nat. Rev. Mater 2017, 2, 16075; [Google Scholar]; g) Shibata H, Heo YJ, Okitsu T, Matsunaga Y, Kawanishi T, Takeuchi S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2010, 107, 17894; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Heo YJ, Shibata H, Okitsu T, Kawanishi T, Takeuchi S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2011, 108, 13399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].a) Rodbard D, Diabetes Technol. Ther 2016, 18, S2; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Vashist SK, Anal. Chim. Acta 2012, 750, 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].a) Klonoff DC, J. Diabetes Sci. Technol 2012,6,1242; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Pickup JC, Hussain F, Evans ND, Rolinski OJ, Birch DJS, Biosens. Bioelectron 2005, 20, 2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Steiner MS, Duerkop A, Wolfbeis OS, Chem. Soc. Rev 2011, 40, 4805; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Howes PD, Chandrawati R, Stevens MM, Science 2014, 346, 1247390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Wu C, Chiu DT, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2013, 52, 3086; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chen X, Li R, Liu Z, Sun K, Sun Z, Chen D, Xu G, Xi P, Wu C, Sun Y, Adv. Mater 2017, 29, 1604850; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pu K, Shuhendler AJ, Jokerst JV, Mei J, Gambhir SS, Bao Z, Rao J, Nat. Nanotechnol 2014, 9, 233; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Li K, Liu B, Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 6570; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Zhu C, Liu L, Yang Q, Lv F, Wang S, Chem. Rev 2012, 112, 4687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Sun K, Tang Y, Li Q, Yin S, Qin W, Yu J, Chiu DT, Liu Y, Yuan Z, Zhang X, Wu C, ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sun K, Yang Y, Zhou H, Yin S, Qin W, Yu J, Chiu DT, Yuan Z, Zhang X, Wu C, ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gough DR, Cotter TG, Cell Death Dis. 2011, 2, e213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Löffler G, Petrides PE, Physiologische Chemie, Springer-Verlag, 2013; [Google Scholar]; b) Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2007, 8, 722; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J, Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol 2007, 39, 44–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Ricca E, Brucher B, Schrittwieser JH, Adv. Synth. Catal 2011, 353, 2239; [Google Scholar]; b) Sperl JM, Sieber V, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2385. [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Grondal C, Jeanty M, Enders D, Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 167; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wen M, Ouyang J, Wei C, Li H, Chen W, Liu YN, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2019, 58, 17425; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Wang H, Zhao Z, Liu Y, Shao C, Bian F, Zhao Y, Sci. Adv 2018, 4, eaat2816; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Huffman MA, Fryszkowska A, Alvizo O, Borra-Garske M, Campos KR, Canada KA, Devine PN, Duan D, Forstater JH, Grosser ST, Halsey HM, Hughes GJ, Jo J, Joyce LA, Kolev JN, Liang J, Maloney KM, Mann BF, Marshall NM, McLaughlin M, Moore JC, Murphy GS, Nawrat CC, Nazor J, Novick S, Patel NR, Rodriguez-Granillo A, Robaire SA, Sherer EC, Truppo MD, Whittaker AM, Verma D, Xiao L, Xu Y, Yang H, Science 2019, 366, 1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tao Z, Raffel RA, Souid AK, Goodisman J, Biophys. J 2009, 96, 2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Baynes J, Dominiczak MH, Medical biochemistry, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bao J, Furumoto K, Yoshimoto M, Fukunaga K, Nakao K, Biochem. Eng. J 2003, 13, 69. [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Chang K, Liu Z, Fang X, Chen H, Men X, Yuan Y, Sun K, Zhang X, Yuan Z, Wu C, Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4323; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fan W, Lu N, Huang P, Liu Y, Yang Z, Wang S, Yu G, Liu Y, Hu J, He Q, Qu J, Wang T, Chen X, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 2017, 56, 1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.