Abstract

The primary and secondary coordination spheres of metal binding sites in metalloproteins have been investigated extensively, leading to the creation of high-performing functional metalloproteins; however, the impact of the overall structure of the protein scaffold on the unique properties of metalloproteins has rarely been studied. A primary example is the binuclear CuA center, an electron transfer cupredoxin domain of photosynthetic and respiratory complexes and, recently, a protein coregulated with particulate methane and ammonia monooxygenases. The redox potential, Cu–Cu spectroscopic features, and a valence delocalized state of CuA are difficult to reproduce in synthetic models, and every artificial protein CuA center to-date has used a modified cupredoxin. Here, we present a fully functional CuA center designed in a structurally nonhomologous protein, cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP), by only two mutations (CuACcP). We demonstrate with UV–visible absorption, resonance Raman, and magnetic circular dichroism spectroscopy that CuACcP is valence delocalized. Continuous wave and pulsed (HYSCORE) X-band EPR show it has a highly compact gz area and small Az hyperfine principal value with g and A tensors that resemble axially perturbed CuA. Stopped-flow kinetics found that CuA formation proceeds through a single T2Cu intermediate. The reduction potential of CuACcP is comparable to native CuA and can transfer electrons to a physiological redox partner. We built a structural model of the designed Cu binding site from extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy and validated it by mutation of coordinating Cys and His residues, revealing that a triad of residues (R48C, W51C, and His52) rigidly arranged on one α-helix is responsible for chelating the first Cu(II) and that His175 stabilizes the binuclear complex by rearrangement of the CcP heme-coordinating helix. This design is a demonstration that a highly conserved protein fold is not uniquely necessary to induce certain characteristic physical and chemical properties in a metal redox center.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The environment around metal-binding sites is critical to establish and fine-tune the functions of metalloproteins. Cupredoxins, such as the mononuclear blue Type 1 copper (T1Cu) and binuclear purple CuA proteins, function as electron transfer (ET) centers in photosynthesis and respiration.1 To perform their functions, these proteins have reduction potentials (E°′) precisely tuned to their redox partners; a change as small as 50 mV, may shut down the ET chain.2 Cupredoxins have evolved a tightly conserved Cu primary coordination sphere (PCS) to maintain efficient ET properties, such as low reorganization energy, while using the secondary coordination sphere (SCS) and more distant interactions to tune the E°′ over a ~500 mV range.1,3–6 The E°′ of cupredoxins has been rationally tuned to span the entire physiological E°′ range through these interactions.7,8 While most studies have focused on mutations of the PCS and SCS to tune E°′, the role of protein scaffold structure has not been investigated. It is generally assumed that the conserved fold of the cupredoxins is critical to create the environment necessary for these finely tuned Cu sites, but experimental support for this assumption is lacking.

The copper binding site in cupredoxins is located in a conserved Greek key β-barrel domain that comprises rigid antiparallel strands connected by short loops that constitute the Cu binding site. Like T1Cu centers, CuA centers from ET subunits in cytochrome oxidase (COX) and nitrous oxide reductase (N2OR) from various organisms share the cupredoxin fold and perform similar ET functions. The binuclear CuA center comprises a pair of covalently bonded copper ions with a single unpaired electron delocalized between nearly equivalent Cu nuclei, [Cu(1.5),Cu(1.5)] in the one-electron oxidized state that produces its eponymous purple color.9 The CuA copper binding domain is closely homologous to the Cu binding loops of T1Cu centers.10 Both sites have conserved 2His, 1Cys, and one distant (~2.8 Å) Met residues, while the CuA has a second Cys positioned between the consensus Cys and the adjacent His residue (Figure 1A). Recently, CuA has been found as a dimer of PmoD, a protein encoded in genomic proximity to and coregulated with particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and ammonia monooxygenase (AMO), which has sparked renewed interest in the role of CuA centers and their previously unknown functions related to enzymes critical to the global carbon and nitrogen cycles.11,12

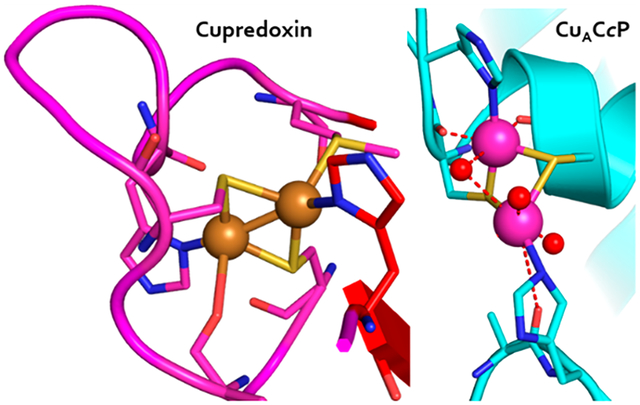

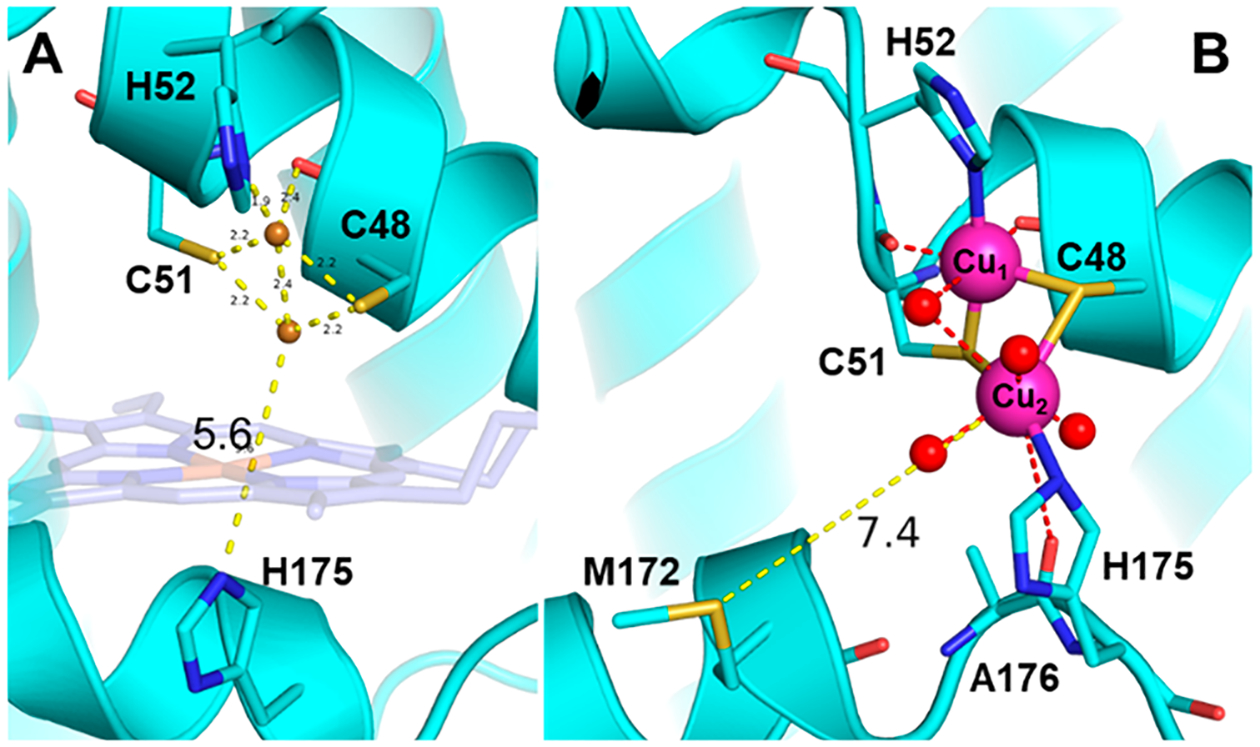

Figure 1.

Comparison of the CuA binding site and the cytochrome c peroxidase active site. (A) Cupredoxin loop of the CuA subunit of T. thermophilus cytochrome ba3 oxidase; Cu ions are drawn as orange spheres (PDB: 2cua). (B) Active site of S. cerevisiae cytochrome c peroxidase with the key binding residues labeled (PDB: 1zby).

Artificial CuA centers that have been created by transplanting the loop sequence from native CuA into the Cu binding loops of the blue Cu proteins amicyanin13 and azurin14–17 without altering the cupredoxin scaffold have provided insight into key structural and electronic properties of Cu redox centers.18–22 A CuA center was similarly restored in cytochrome o quinol oxidase (CyoA),23 which has a vestigial Cu binding loop whose ET function had been lost. A critical common feature of these engineered Cu ET centers is the preservation of the cupredoxin scaffold. While decades of research have shown that elements of this domain can be flexibly transposed between cupredoxins to result in similar T1Cu, CuA, and even red copper centers,24 no attempt to create an artificial binuclear copper center without the cupredoxin fold—and the structural effects induced by it—has fully reproduced the distinctive spectroscopic features and high E°′ of natural cupredoxin centers.20,25–27 Here, we present the design and characterization of the first example of a purple CuA center in an all α-helical domain of a non-cupredoxin protein, cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP, Figure 1B), replacing its heme binding site. We were able to construct a CuA center in CcP by mutating only two residues of the CcP active site to cysteine, residues Arg48 and Trp51, which we call CuACcP. The artificial CuA center shares the core Cu-binding ligands of native CuA—2His and 2Cys residues arranged to create a diamond core motif that promotes a Cu–Cu covalent bond—with virtually no structural homology to the cupredoxin fold. Here, we provide comprehensive spectroscopic studies of the electronic absorption in the UV–vis region (UV–vis), electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR), X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS), resonance Raman (rR), and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) of the CuA center in CuACcP that show it has the essential features of native and engineered CuA centers in cupredoxin scaffolds, including redox properties.

RESULTS

Reconstitution of a purple CuA center in mutant CcP.

The R48C/W51C–CcP mutant was constructed and purified as previously described,28 yielding predominantly apoprotein, but a small amount (~3–7% of total protein) was purified with heme-bound protein. Through additional rounds of ion exchange chromatography, we could separate most of the heme-bound protein from the apoprotein (<2%) until the heme contribution in the 350–700 nm absorption region was minimal. Addition of substoichiometric equivalents of CuSO4 to 100 μM purified apoprotein at room temperature and physiological pH (pH 7.4) resulted in an immediate increase in absorption at ~380 nm (Figure S1). Addition of Cu(II) up to ~2.0 equiv resulted in a transition of the ~380 nm species to a second species with absorption maxima at ~500 nm and ~850 nm (Figure S1) and which appeared vividly magenta in color. The transition was continuous with each addition of Cu(II) and completed within ~5 min after each addition.

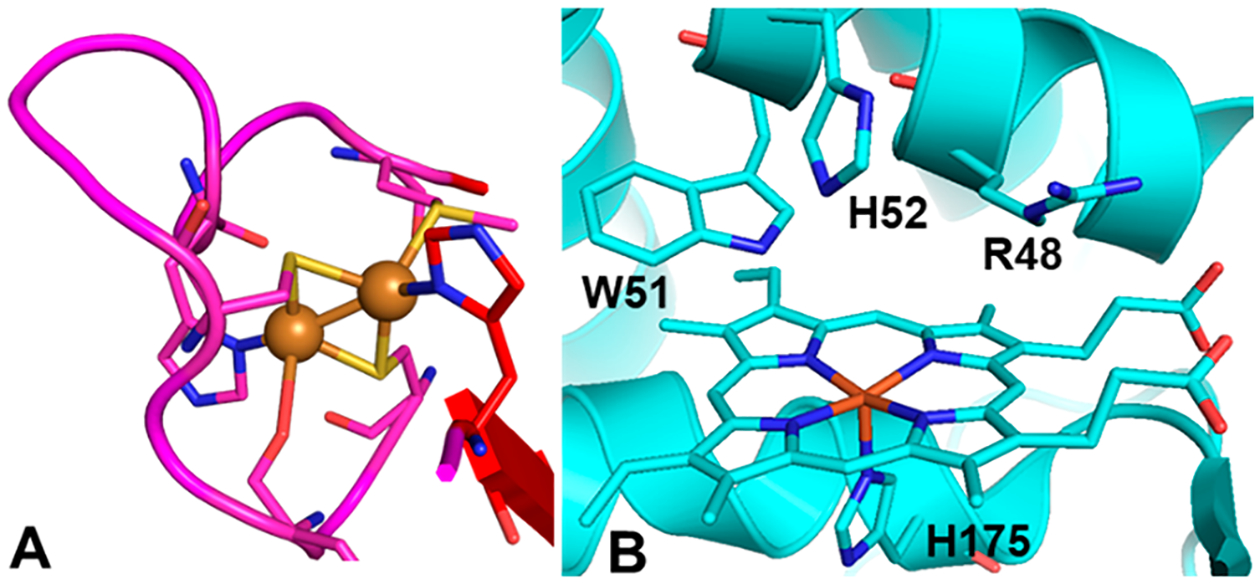

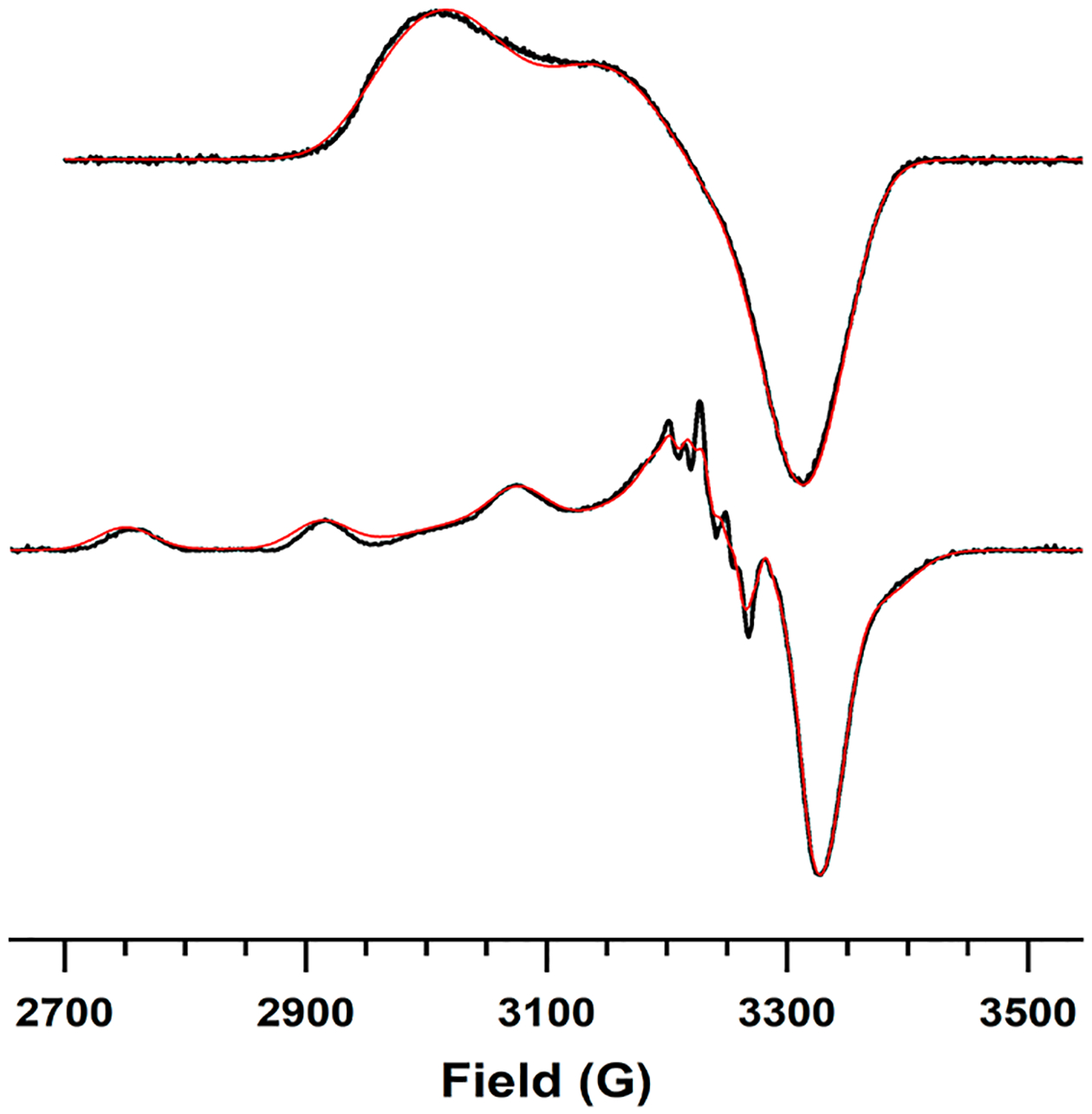

The intensity of the Soret band (~100 mM−1 cm−1) from the residual heme protein was nearly equal in magnitude to the intensities of the Cu species, but the heme spectrum did not change substantially with the addition of Cu(II) (Figure S1). We could therefore subtract the initial absorption spectrum with correction for dilution from all subsequent spectra to obtain the isolated spectra of the Cu-bound species (Figure S1, inset). We reconstituted a higher protein concentration (150 μM) by adding 2.5 mol equiv of CuSO4 at once (Figure S2A). The ~380 nm feature appeared in less than 3 s to approximately 2-fold the peak intensity of gradual Cu addition and more rapidly converted to the magenta species, disappearing completely within 5 min. Global fitting of the difference spectra of this process revealed two distinct species, shown in the inset of Figure 2. Peak maxima and extinction coefficients of both species are given in Table 1. The short-lived intermediate species was found to have λmax = 375 nm, a shoulder at 455 nm, and a broad peak at ~640 nm, resembling a type 2 copper (T2Cu) species like those found in red copper proteins.29–31 The intense transition of this species at 375 nm is indicative of pseudo σ SCys-to-Cu(II) charge transfer (CT), while the shoulder at ~450 nm is consistent with a weakened π SCys-to-Cu(II) CT. The broad 640 nm feature is from dz2 → dx2 − y2 transition.

Figure 2.

Difference spectra of the full anaerobic reconstitution of CuACcP at pH 7.4 by addition of 2.5 mol equiv of Cu(II) at room temperature. The initial spectrum of the apoprotein, which contains ~5% hemoprotein, has been subtracted. Arrows indicate the trajectory of absorbance changes over the course of 400 s, and asterisks denote isosbestic points. Spectra of two distinct species are shown in the inset. The green T2Cu intermediate species and stable purple species are shown in close approximations of their respective apparent colors with absorption peaks indicated.

Table 1.

Absorption Maxima of the Mononuclear T2Cu and Binuclear CuA-Like Species Observed in CuACcP

| Species | λmax (nm) | ελ (M−1cm−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Green T2Cu intermediate | 375 | 4557 |

| 641 | 523 | |

| Purple CuA species | 355 | 502 |

| 486 | 3221 | |

| 841 | 1421 |

Though this first Cu-bound species rapidly transitioned to the second species at room temperature (~10 s after CuSO4 was added), we were able to isolate it by gradual addition of subequivalents of Cu(II) at 10 °C. Surprisingly, the isolated T2Cu species appeared vividly iridescent green rather than the anticipated red despite bearing no resemblance to the UV–vis spectra of the so-called green copper sites that can result from perturbed T1Cu centers.32,33 The green color apparently arises from CT and d−d transitions, particularly the 641 nm feature and local minimum at ~550 nm, that are higher in energy than the well-characterized T2Cu red copper protein nitrosocyanin, which exhibits such features at 390, 500, and >700 nm, respectively.29,31

The T2Cu species began to decrease in intensity to be replaced by the magenta species after addition of ~0.5 equiv of Cu(II), reaching completion within 15 min at 10 °C. The magenta species displayed an absorption band at 486 nm with a ~530 nm shoulder, and a broad 841 nm band, all of which resemble the features of CuA centers found in COX, N2OR, and several engineered cupredoxins with CuA sites created through loop-directed mutagenesis.13,14,23,34 Addition of >2 equiv of Cu(II) only resulted in gradual bleaching of this species with no new species arising. The apparent red/pink color of Cu-reconstituted R48C/W51C–CcP is likely due to the small but relatively intense heme absorption (ε410 nm ~ 100 mM−1 cm−1) mixed with the weaker absorbance of the ostensibly “purple” binuclear CuA center. We therefore named R48C/W51C–CcP “CuACcP.” On the basis of prior reports that used mixtures of Cu(II) and Cu(I), we compared the yield of the CuA-like species from reconstitution with Cu(II) only in air to the addition of 1 equiv of Cu(II) followed immediately by 1 equiv of Cu(I) in an anaerobic chamber. Under anaerobic conditions with a 1:1 Cu(II)/Cu(I) reconstitution, we obtained a greater yield (26% higher CuA absorption, Figure S2B) than that in air and with Cu(II) alone. This result is similar to the increase in CuA yield when CuA-Az was reconstituted with equimolar Cu(II) and Cu(I) or when a sacrificial reductant (ascorbate) was added before reconstitution.35 We also noted that the yield of the CuA-like species was somewhat variable at room temperature but was consistent when maintained at 10–15 °C.

Stability and Structure of the CuACcP Mutant.

Given that the introduction of adjacent Cys mutations could have perturbed the overall structure of the protein, we attempted to crystallize Cu-reconstituted CuACcP and apo-CuACcP, but we did not obtain any crystals. This result is not surprising, because no structures of heme-free CcP have been reported despite numerous crystal structures of heme-containing CcP and its variants. Instead, we obtained a crystal structure of heme-bound CuACcP to 1.6 Å (heme reconstitution, crystallization conditions, and full X-ray statistics are described in the SI). As shown in Figure S3, an overlay of the crystal structures of heme-bound WT CcP (PDB: 2cyp) and CuACcP indicates that the backbone of the CuACcP mutant is virtually unchanged compared to WT CcP. In addition, we obtained circular dichroism (CD) spectra of apo-CuACcP, CuA-reconstituted CuACcP, and heme-CuACcP (Figure S4), which show that while the apoprotein has notably different secondary structure, the secondary structures of the Cu- and heme-reconstituted proteins are very similar. Since the crystal structure of heme-CuACcP is very similar to heme-WT CcP, the similar CD spectra suggest that the overcall structure of CuA-reconstituted CuACcP is similar to when heme is bound. To further establish the availability of the R48C/W51C site for Cu binding, we reconstituted the CuA species after pretreatment of the apoprotein with 2 mM DTT for 1 h to reduce possible disulfide bonds. After removal of the DTT by gel filtration, we observed no difference in the final yield of the CuA species. To confirm that no disulfide bonds are present in the apoprotein, we conducted an Ellman’s assay for free sulfhydryl groups and found that ~3 free Cys were present per protein molecule as-purified, which correspond to the native CcP Cys128 and the two mutant Cys residues, which are both quite distant from Cys128 (Figure S5).

Mass Spectrometry of Cu-Reconstituted CuACcP.

To measure the number of Cu ions bound to CuACcP, we collected native electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) of the Cu-reconstituted protein. The native ESI-MS (Figure S6) contained a major peak for the apoprotein (33591.85 Da, predicted mass from protein sequence = 33594.58 Da) and a second peak at +126.5 Da (33718.35 Da) that corresponds to two bound Cu ions. No peaks were present equal to one bound Cu ions (~33655 Da). From the mass spectrum, we could clearly see that two Cu ions are indeed bound in the CuA-like species. The lack of a peak associated with a single bound Cu ion supports our observation from the UV–vis spectra that the T2Cu species is completely eliminated and that the only Cu-containing species after equilibration is the CuA species.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) Spectroscopy of the Green and Purple Copper Species.

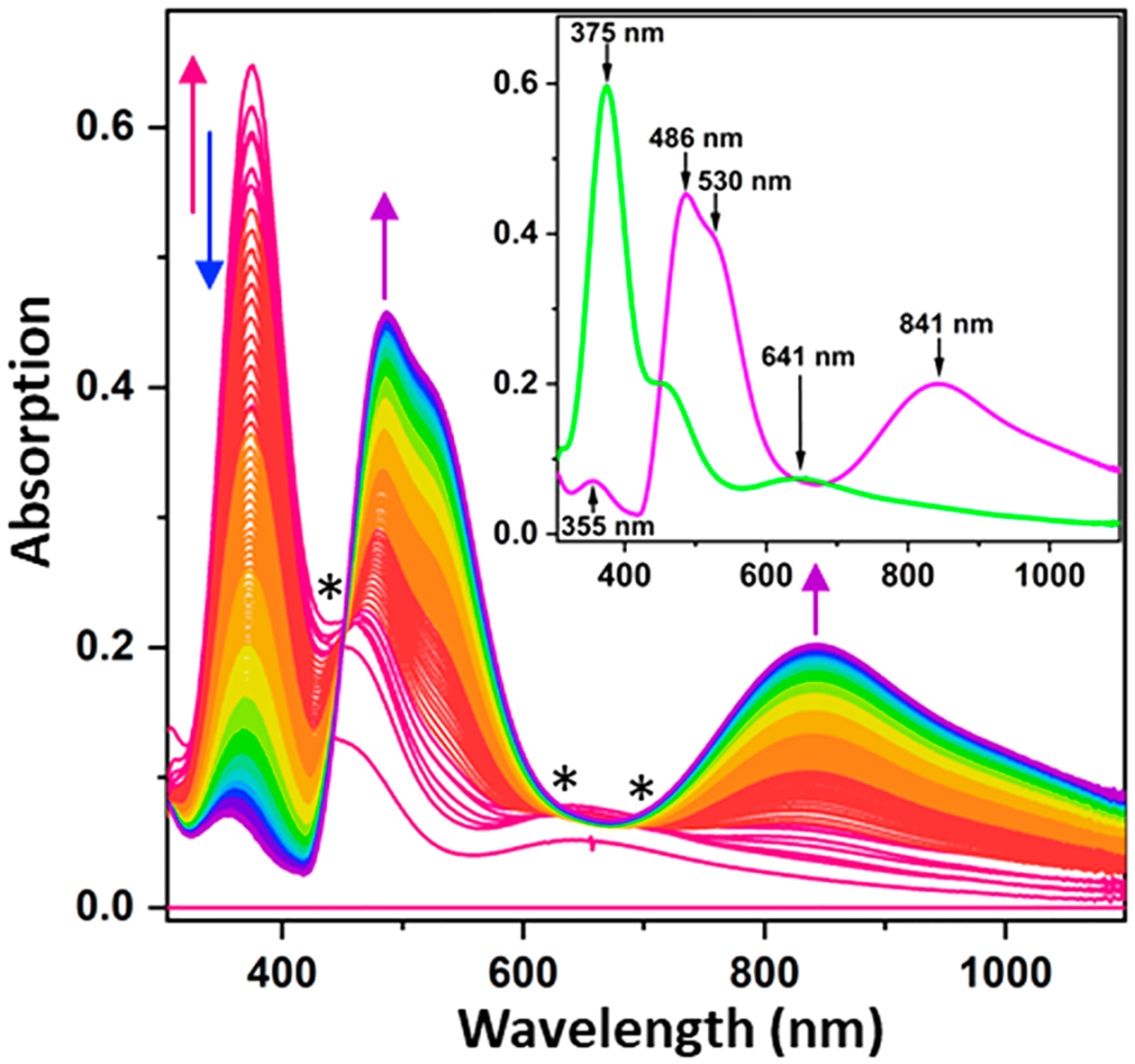

The X-band continuous wave (CW) EPR spectra of the two Cu-reconstituted species described above are shown in Figure 3. The CuA-like species (Figure 3, upper trace) shows an axial signal centered around g = 2 with g|| > g⊥ that resembles previously reported native and engineered mixed valence CuA centers19,36–38 but with the characteristic 7-line hyperfine structure unresolved. We initially attempted to simulate the spectrum assuming two equivalent Cu nuclei with collinear g and hyperfine (A) tensors, which returned an unusual result of Ay > Ax,z. We then simulated the spectrum assuming z-axis of the g and A tensors were noncollinear (0 < β < 90°) for each Cu and found that the spectrum could be reasonably reproduced with Az = 82.5 MHz for one Cu but Az = 50.5 MHz for the other (Table 2). A similar A tensor rotation was noted in the EPR spectra of CuA azurin in low pH and its H120A mutant, which both displayed 4-line hyperfine patterns but were found nevertheless to be valence delocalized.39 The driver of the large difference in Az between the two Cu nuclei was a small amount of 4s orbital mixing into the ground-state spin wave function of one Cu.39,40 The positive peak near the gy feature in the CuACcP CuA species is less intense than in other reported CuA spectra, which may be a result of broadened gx,y area. The gx-gy anisotropy is large (>0.06) compared to engineered CuAAz (gx ≈ gy ≈ 2.02), but these g-values resemble spectra reported for CuA from P. denitrificans.19,41

Figure 3.

EPR spectra of the CuA-like species (top) and the green T2Cu intermediate (bottom) at pH 7.4. Spectra have been normalized to their minima. Experimental data are drawn as black lines, and simulated spectra as red lines. Samples were measured at 2 mW power, 9.17 GHz (top) and 9.29 GHz (bottom) at a temperature of 77 K; a similar spectrum for the CuA-like species was obtained at 30 K.

Table 2.

EPR Parameters from the Spectra of the T2Cu Intermediate and CuA-Like Species of CuACcP

| Species | gx | gy | gz | AxCul, AxCu2 (MHz) | AyCul, AyCu2 (MHz) | AzCul, AzCu2 (MHz)(β°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2Cu | 2.041 | 2.039 | 2.217 | 56.31 | 57.44 | 505.7 |

| CuA | 1.980 | 2.041 | 2.180 | 36.0, 35.2 | 57.9, 67.6 | 50.5(40), 82.6(8.8) |

The larger Az hyperfine coupling constant is 82.5 MHz, which is notably smaller than is typical for CuA species, including the CuAAz mutants M123H, whose X-band spectrum showed significantly different Az for the two Cu nuclei (174.2 and 126.1 MHz), and M123L, which had an atypically small Az at 105 MHz.21 To validate this small Az, we measured the total width of the gz area of published CuA X-band EPR spectra with resolved and unresolved hyperfine structure from several different CuA proteins (Table S1). These gz areas and their corresponding reported Az values vary 2-fold across CuA centers in different proteins. We measured the span of the gz area in CuACcP as 517 MHz, which is smaller than any previously analyzed spectrum, and would predict an Az of ~80 MHz in CuACcP, which is consistent with our simulation. The gz areas, Az values, and the number of resolved hyperfine structure of reported CuA spectra suggest that the structure becomes unresolvable both with decreasing Az and from large differences between the coupling constants of the two Cu nuclei due to differences in their ligand fields. Certainly, we do not expect CuA in CuACcP to have an axial ligand set identical to native CuA proteins (Figure 1 and vide infra), and the possibility of inequivalent axial structure could play a role in both a broadened gx,y area and unresolved hyperfine structure.

We attempted to prepare a sample of the isolated T2Cu intermediate by mixing apoprotein with 0.6 equiv of Cu(II) at 10 °C and rapidly freezing the solution (<10s) to obtain its EPR spectrum without signal contamination from the CuA species. The resulting spectrum is given in the lower trace of Figure 3. The Az hyperfine constant of this species is 505.7 MHz (Table 2), which is indeed indicative of T2Cu centers. However, due to the rapid formation of CuA at even 0.6 equiv of Cu(II), ~30% of the total spins were still attributable to the CuA species in this sample, which was accounted for in the simulation (Figure 3). The Az of the T2Cu in CuACcP is closer to that of a red Cu center24,30,31 than to that of the tetragonally distorted T1Cu “green” Cu centers,32,33 apparent color notwithstanding. This T2Cu species also displays well resolved nitrogen hyperfine splitting in g⊥, suggesting the presence of at least one His ligand.

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy.

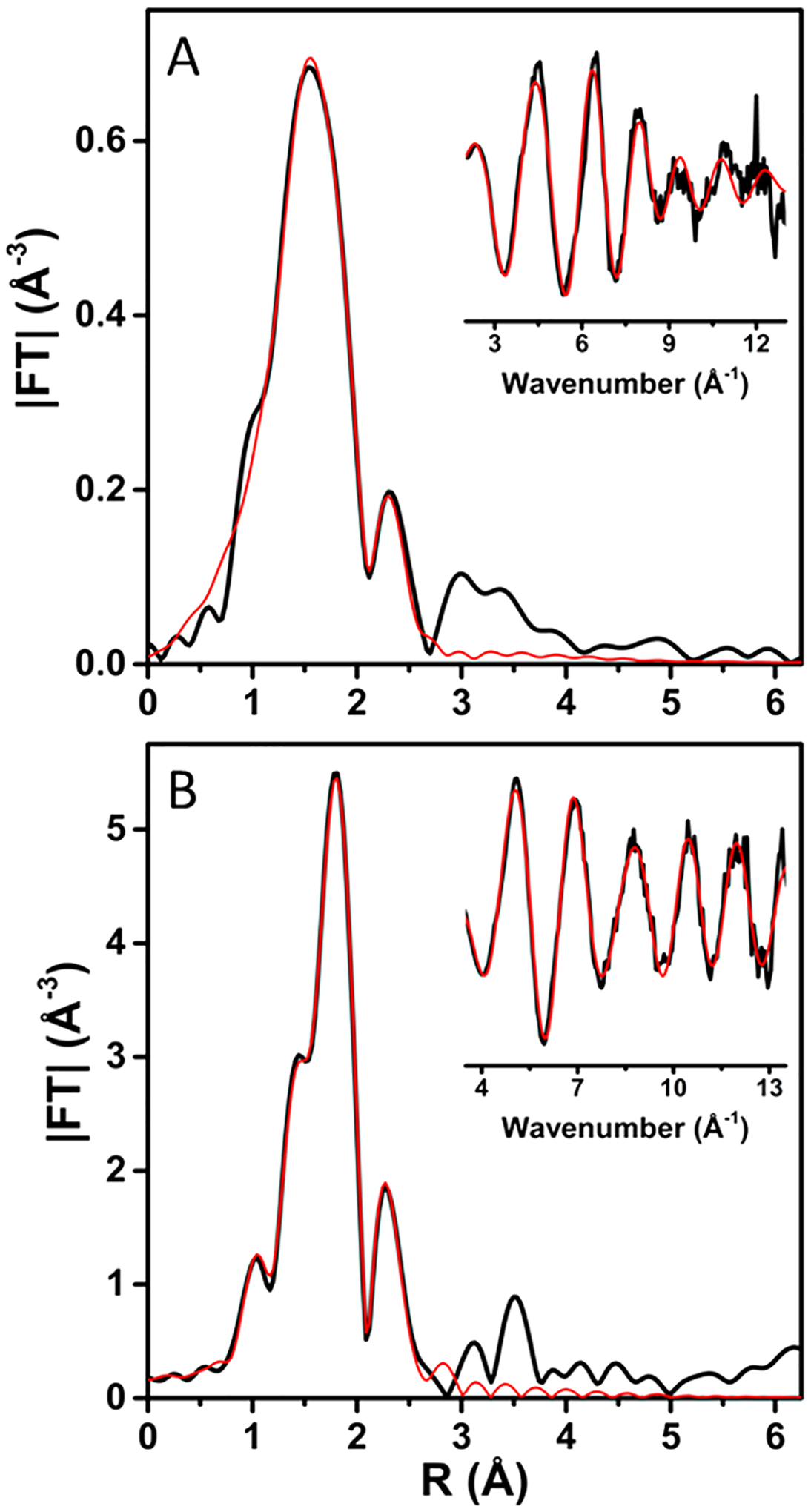

We collected the X-ray absorption near-edge (XANES) and extended fine structure (EXAFS) spectra of the CuA species and T2Cu species in CuACcP to determine whether the structures of these species were consistent with those of previously studied CuA or any of its precursors. The Fourier transform (FT) plots of the CuA species (Figure 4A,B) are dominated by a Cu–S scattering peak, but a weaker peak at ~2.4 Å is also present from Cu–Cu scattering. We obtained the best EXAFS fits for samples in both the mixed valence [Cu(II),Cu(I)] (mixed valence, Figure 4A) and [Cu(I),Cu(I)] (reduced, Figure 4B) states by modeling scattering paths for a binuclear Cu–Cu center calculated from native COX CuA structures with 1 Cu, 2 SCys, and 1 NHis scattering atoms per Cu (Table S2). For the oxidized sample, the best fit to the data was obtained from a model with a Cu–Cu distance of 2.46 Å and Cu–SCys distance of 2.23 Å. A Cu2S2 diamond core with these bond lengths would have a S–Cu–S angle of 66°.

Figure 4.

Fourier transform and EXAFS (inset) of (A) oxidized (as prepared) CuACcP reconstituted with Cu(II) and (B) subsequently reduced with ascorbate. Experimental data are shown as solid black lines, and fits are shown as red lines. Parameters used for the fits shown are given in Table S2.

The Cu–Cu bond in mixed valence CuACcP is slightly longer than the 2.39 Å in CuAAz and 2.43 Å in T. thermophilus CuA, but the EXAFS otherwise resemble reported bond lengths and angles of native and biosynthetic models of mixed valence CuA.42–44 The best fit of the fully reduced CuACcP species reveals slightly shortened Cu–SCys (2.19 Å) and Cu–NHis (1.91 Å) bond distances with a significantly longer Cu–Cu bond (2.61 Å). The longer Cu–Cu bond increases the S–Cu–S angle to 73° and notably distorts the diamond core relative to the mixed valence state. The binuclear Cu center of native CuA has an even lower reorganization energy than mono-nuclear blue T1Cu centers,45,46 and the geometry of the Cu2S2 diamond core has been observed to change very little during redox cycling with bond lengths varying by <0.1 Å and the S–Cu–S angle remaining essentially constant.44,47 We therefore observed the fully reduced CuACcP species to reorganize by a significantly greater degree than native CuA centers. The Debye–Waller factors for the Cu–Cu and, particularly, Cu–SCys scattering paths are somewhat large (Table S2), so the CuACcP diamond core could be distorted even in the mixed valence state, but the presence of difficult-to-remove additional Cu species somewhat muddles the spectrum. For instance, we found that the CuACcP reconstituted with heme binds at least one equivalent of Cu(II) that has at least one Cys ligand. This species is likely a recurring contaminant in our spectra, and so we prepared and characterized its XAS spectra separately, detailed in the SI.

The FT plot of the T2Cu species EXAFS (Figure S7) contains a single peak that is again dominated by Cu–S scattering. The EXAFS of the T2Cu species essentially describe a mononuclear Cu center that is best fit as a tridentate Cu complex (N = 3) consisting of one Sγ (Cys) ligand, one N (His) atom, and one N/O atom (likely water) in the first shell (Table S3). It should be noted that though this model of N and O distances resulted in the best fit and is consistent with typical His-Cu distances, the assignment of O and N atoms is not definitive. Nevertheless, this ligand set is consistent with the UV–vis and EPR features that indicate one Cys and at least one His ligand.

We collected the XANES of every sample simultaneously with the EXAFS, and from them, we were able to construct a more complete picture of the oxidation states of the isolated species. The XANES spectra of all species display a pre-edge peak (8982 eV) which we attribute to sample reduction in the X-ray beam; this feature is least intense for the Cu(II)-bound hemoprotein (Figure S8). The pre-edge feature is most intense for CuA reduced with ascorbic acid. The increase in pre-edge intensity and corresponding decrease in the first post-edge peak (8994 eV) are indicative of an increasing degree of Cu(I) character in each species. The shapes of these pre-edge features also suggest that both the T2Cu species and the CuA species have some mixing of 3-coordinate and 4-coordinate Cu(II) character. When reduced, however, the CuA species appears primarily 3-coordinate, suggesting a weakening or loss of axial ligands.

Resonance Raman and Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy.

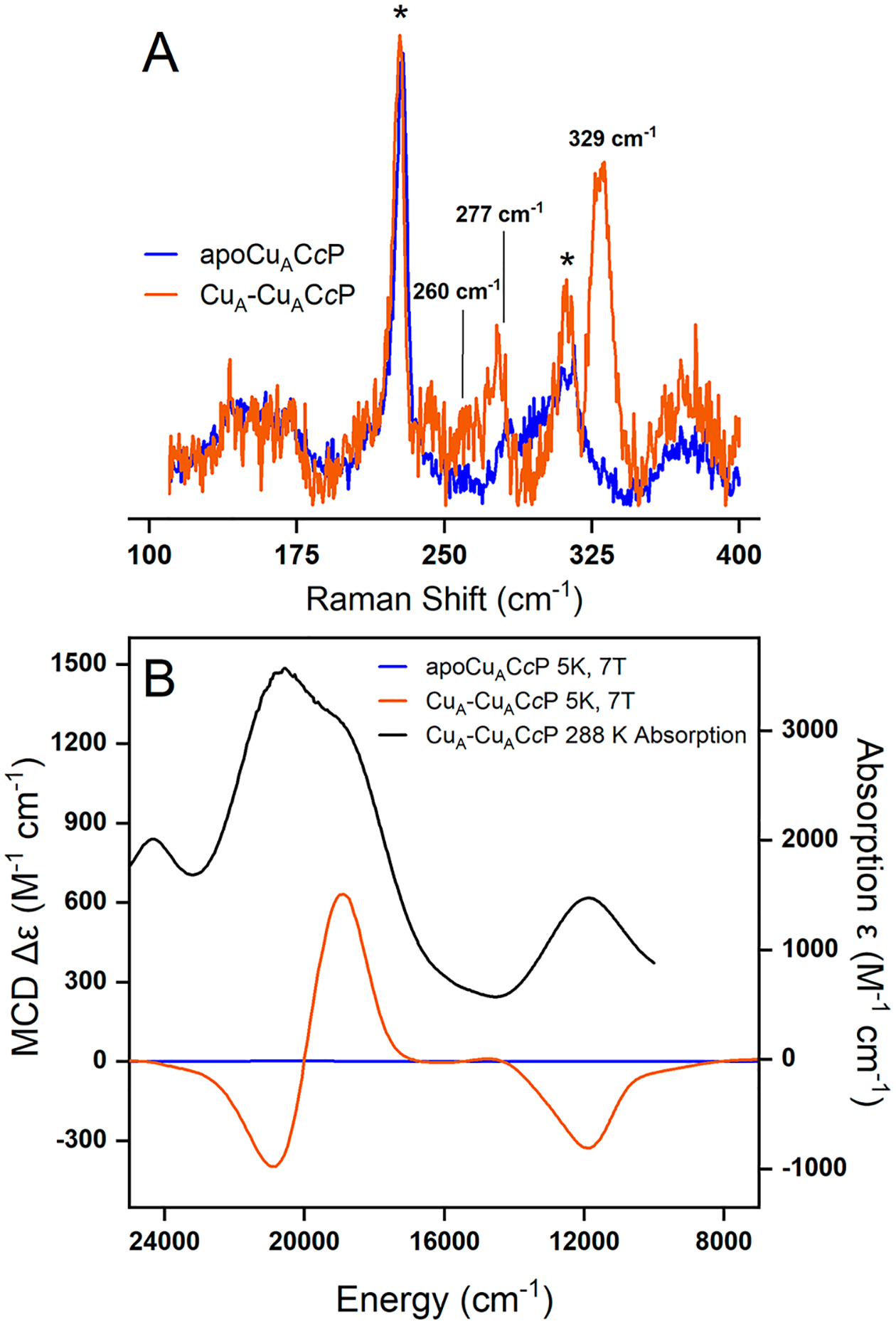

Resonance Raman (rR) and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectra were collected from apo-CuACcP and the CuA-reconstituted holoprotein. Figure 5A shows the rR spectrum of CuACcP at 840 nm excitation (~11900 cm−1) corresponding to the near-IR absorption feature of CuACcP (Figure 2). The rR spectrum of CuACcP is dominated by a 329 cm−1 peak (ν4) along with additional peaks at 277 cm−1 (ν3) and 260 cm−1 (ν2). These are assigned as the resonance enhanced Cu2S2 core breathing mode, the out of phase “twisting” Cu–S stretching mode, and a mixed Cu–S/Cu–N stretching mode, respectively.20 These features are very similar to those observed in the rR spectrum of other CuA sites.20,21,39 A In addition to these three features, a fourth feature at lower energy (~130 to 160 cm−1) is observed in other CuA systems which has been assigned as the Cu2S2 core “accordion” mode (ν1) with a major contribution from the symmetric Cu–Cu stretch,20,21,39 but we do not observe this feature in the rR spectrum of CuACcP at a vibrational energy above 110 cm−1, the cutoff of our data due to scattering from the laser line. The rR bands observed in CuACcP are not significantly broader when compared to those for other CuA systems and have a reasonable signal-to-noise ratio. Thus, we would expect to see the accordion mode involving the symmetric Cu–Cu stretch if it was in our energy window. The lack of a resonance enhanced ν1 vibration may reflect its energy being below our 110 cm−1 energy cutoff.

Figure 5.

Resonance Raman and magnetic circular dichroism (MCD) spectra of CuACcP apoprotein and Cu-reconstituted protein (CuA-CuACcP) at 7 T. (A) Resonance Raman spectra at 840 nm excitation of CuACcP (orange) and apoprotein (blue). Ice peaks are marked with an asterisk (*). (B) Room temperature absorption of CuACcP (black) and low temperature (5 K) MCD spectra of CuA-CuACcP (orange) and apoprotein (blue).

To confirm that CuACcP belongs to the class III mixed valent CuA systems suggested by its EPR spectrum (Figure 3) like other CuA proteins (as opposed to the class II localized valence systems of many artificial dicopper complexes), we collected the low temperature MCD spectra of the CuA species (Figure 5B and Table 3). Class III mixed valent CuA systems have characteristic features in their low temperature MCD spectra.20,21,39 The low temperature MCD of CuACcP has an intense derivative-shaped pseudo-A term feature (18940, 20920 cm−1, Figure 5B, orange trace). This corresponds to features between 17000 and 22000 cm−1 in the absorption spectrum of CuACcP (Figure 5B, black trace; note that this is the raw absorption spectrum of the prepared MCD samples, as in Figure S2, not the difference spectrum as in Figure 2) that have been assigned as the Scys → Cu CT transitions of the bridging thiolates by rR.20 Another band at ~11900 cm−1 in the absorption spectrum of CuACcP exhibits a negative C-term MCD feature and has been assigned as the Ψ → Ψ* transition which involves excitation of an electron from the σg Cu–Cu bonding orbital to the σu antibonding orbital.20 The longer Cu–Cu bond of the mixed valence species determined from EXAFS suggests that CuACcP has a weaker Cu–Cu bond than other CuA systems, which is supported by a Ψ → Ψ* transition (~840 nm) that is lower in energy than in other CuA (Table 3). These MCD features of CuACcP, particularly the Ψ → Ψ* transition, are characteristic of class III mixed valent CuA sites that have been difficult to reproduce in synthetic CuA mimics.20,21,39 Further, the ratio of MCD C-term intensity to the absorption intensity of the band at ~11900 cm−1 in CuACcP, Co/Do = −0.39, is in close agreement with that for other CuA systems (Table 3) and supports the valence delocalized description of CuACcP.

Table 3.

Energy and C0/D0 of the NIR MCD Band in Different CuA Proteins and CuACcPa

| CuA System | Energy (cm−1) | C0/D0 |

|---|---|---|

| CuA subunit in CcO20 | 13175 | −0.29 |

| CuA-Azurin20 | 13670 | −0.16 |

| High pH CuA-Azurin39 | 13300 | −0.43 |

| CuA-Amicyanin20 | 13440 | −0.20 |

| CuACcP | 11875 ± 6 | −0.39 |

The error in the band energy of CuACcP is comparable to the other reported CuA systems.

Pulsed EPR: ESEEM and HYSCORE.

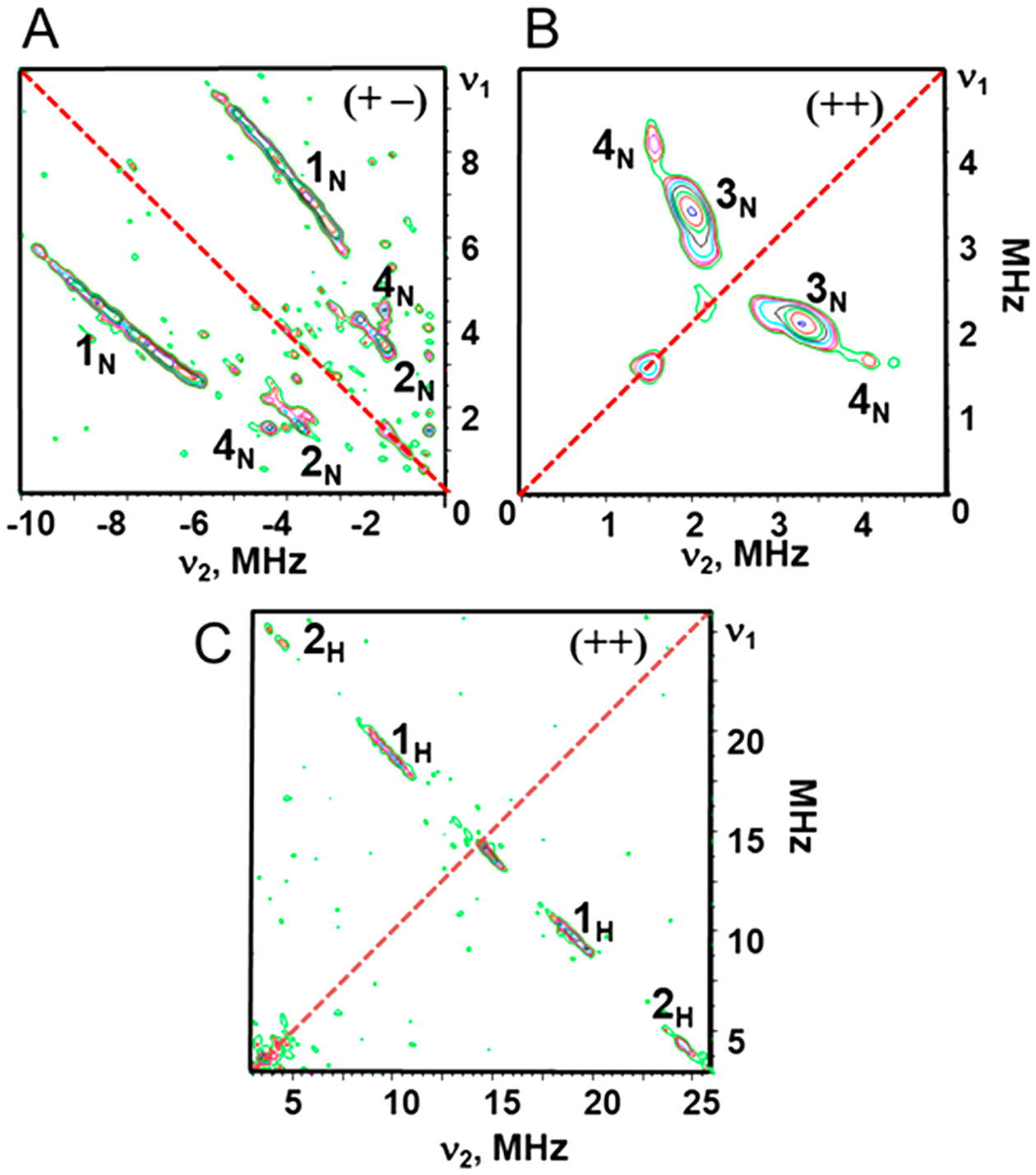

Given the lack of a resolved 7-line hyperfine continuous wave spectrum for the CuA species, we probed the unresolved hyperfine interactions of 14N and 1H nuclei of the CuA ligands by pulsed electron spin echo envelope modulation (ESEEM) and its two-dimensional version, hyperfine sublevel correlation spectroscopy (HYSCORE). The complete 1H and 14N HYSCORE spectra of CuACcP collected at the g⊥ region (see Figure 3, upper trace) are given in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Contour representations of the 14N and 1H HYSCORE spectra of Cu-reconstituted CuACcP. (A) Features of strongly coupled 14N nuclei appear in the (+−) quadrant; (B) weakly coupled features in the (++) quadrant. (C) 1H HYSCORE spectrum of the CuA-like species. Hyperfine splitting values for the cross-ridges were determined in first order as the absolute difference A = |ν1-ν2|, where ν1 and ν2 are coordinates of the point with the maximum intensity for cross-ridges 1H and 2H. Spectra were collected with a microwave frequency of 9.6316 GHz, magnetic field of 336 mT, and time between the first and second pulses (τ) of 136 ns.

The spectrum consists of two quadrants containing cross-features from strongly and weakly coupled nitrogen atoms and several protons. The most prominent feature of the (+−) quadrant (Figure 6A) is the pair of 1N cross-ridges along the antidiagonal that vary by ~3 MHz in both dimensions but without well-defined maxima (Figure S9A). The location of 1N cross-ridges in the (+−) quadrant as well as the difference between coordinates along them allow us to assign them to double-quantum correlations (dq+, dq−) from nitrogens with hyperfine coupling that substantially exceeds the Zeeman frequency (νN = 1.03 MHz in this spectrum) of 14N.48,49 We estimate the corresponding hyperfine coupling constant AN of this feature (eqs S1 and S2)50 to vary between 3.6 and 6.8 MHz with an average value of 5.2 MHz. Previous ENDOR studies of the CuA center in bovine heart cytochrome aa3 oxidase and T. thermophilus cytochrome caa3 oxidase reported AN with low values (6.0 and 8.7 MHz) for one coordinated His nitrogen,51 similar to what we have observed in CuACcP, but another AN ~ 17 MHz resolved in these ENDOR spectra was assigned to the second His ligand. A minor pair of cross-ridges 2N with maxima at (±3.4, ∓1.5) MHz in the (+−) quadrant are assigned to single-quantum correlations of the same nitrogens because the difference in frequency between coordinates along these ridges is close to 2νN in contrast to 4νN for 1N.

The intense cross-peaks 3N (3.3, 2.0) MHz in the (++) quadrant (Figures 6B and S9A) correlate to the νdq± transitions of weakly coupled 14N nuclei. In this case, eq S2 gives an estimate of the hyperfine coupling AN = 0.83 MHz and the quadrupole coupling constant K = e2qQ/4h = 0.39−0.45 MHz (for the asymmetry parameter 0<η<1). The small AN and value of K ~ 0.4 MHz, typical for protonated imidazole nitrogens,52,53 indicate these features arise from remote imidazole nitrogens. The same assignment has been made for the intense doublets at similar frequencies (2.8–3.1, 2.0–2.2) MHz in 14N HYSCORE spectra of CuAAz54 and subunit II of T. thermophilus COX.55 Cross-peaks at the same frequencies (3.3, 2.0) MHz were observed in the 14N HYSCORE of CuA in PmoD,12 while ENDOR spectra of PmoD contain resolved hyperfine coupling AN ~ 17 MHz assigned to the coordinated nitrogens of His ligands. On the basis of this result, the 3N peaks in the HYSCORE spectrum of CuACcP indicate the existence of at least one coordinated nitrogen with the same coupling of ~17 MHz. This suggestion is also supported by the ratio 17/0.83~20 of nitrogen AN values, which is a typical value for coordinated and remote nitrogens of the imidazole rings ligated to Cu(II) and other metals.52,53

Cross-ridges 4N of low intensity with absolute values of both coordinates at (4.0, 1.5) MHz are observed in both quadrants (Figure 6A,B). Each peak is parallel to one coordinate axis, indicating that the corresponding nitrogen(s) have a coupling AN ~ 2 MHz close to 2νN (Figure S9B).52 These values are typical of remote nitrogen(s) of imidazole coordinated Cu(II) complexes and therefore indicate some amount of mono-nuclear nitrogen-coordinated Cu(II) in the sample, which we attribute to contaminating amounts of Cu(II)-bound heme protein (Figure S9B).

The 1H spectrum (Figure 6C) contains only two pairs of well-separated cross-ridges located symmetrically relative to the diagonal line with hyperfine splittings of ~9 MHz (1H) and 19 MHz (2H) (Figures 6C and S10). Linear regression analysis in ν12 vs ν22 coordinates56 of the cross-ridge contour lineshapes under the axial approximation for protons H1 and H2 give anisotropic couplings (T) in the narrow range 2.08 ± 0.1 MHz, while the isotropic couplings (a) are significantly different for these protons (8.7 or −10.8 MHz, H1; and 20.1 or −22.1 MHz, H2) with two possible solutions of opposite sign. These a values are consistent with those previously reported for cysteine Cβ protons (Table S4).12,54,57,58 While ENDOR spectra have previously determined hyperfine tensors for four cysteine Cβ protons resonances in N2OR,57,59 only a single pair of cross-ridges, as here, was observed in the 1H HYSCORE spectra of the H120G mutant of CuAAz.54 It has been suggested these differences arise from the overlap of the lines produced by different Cβ protons with close isotropic couplings: this increases the apparent length of the cross-ridges and leads to a larger anisotropic component in the formal analysis.54 An additional possible factor decreasing the number of resolved peaks from Cβ protons is the small value of the isotropic coupling (~4–5 MHz). In this case, the cross-features from these protons overlap with the central peak from weakly coupled protons in the protein environment. The very weak 2H lines can be tentatively assigned to a T2Cu complex,57,59 presumably the same mononuclear complex assigned to the 4N cross-peaks.

Kinetics of Cu Binding.

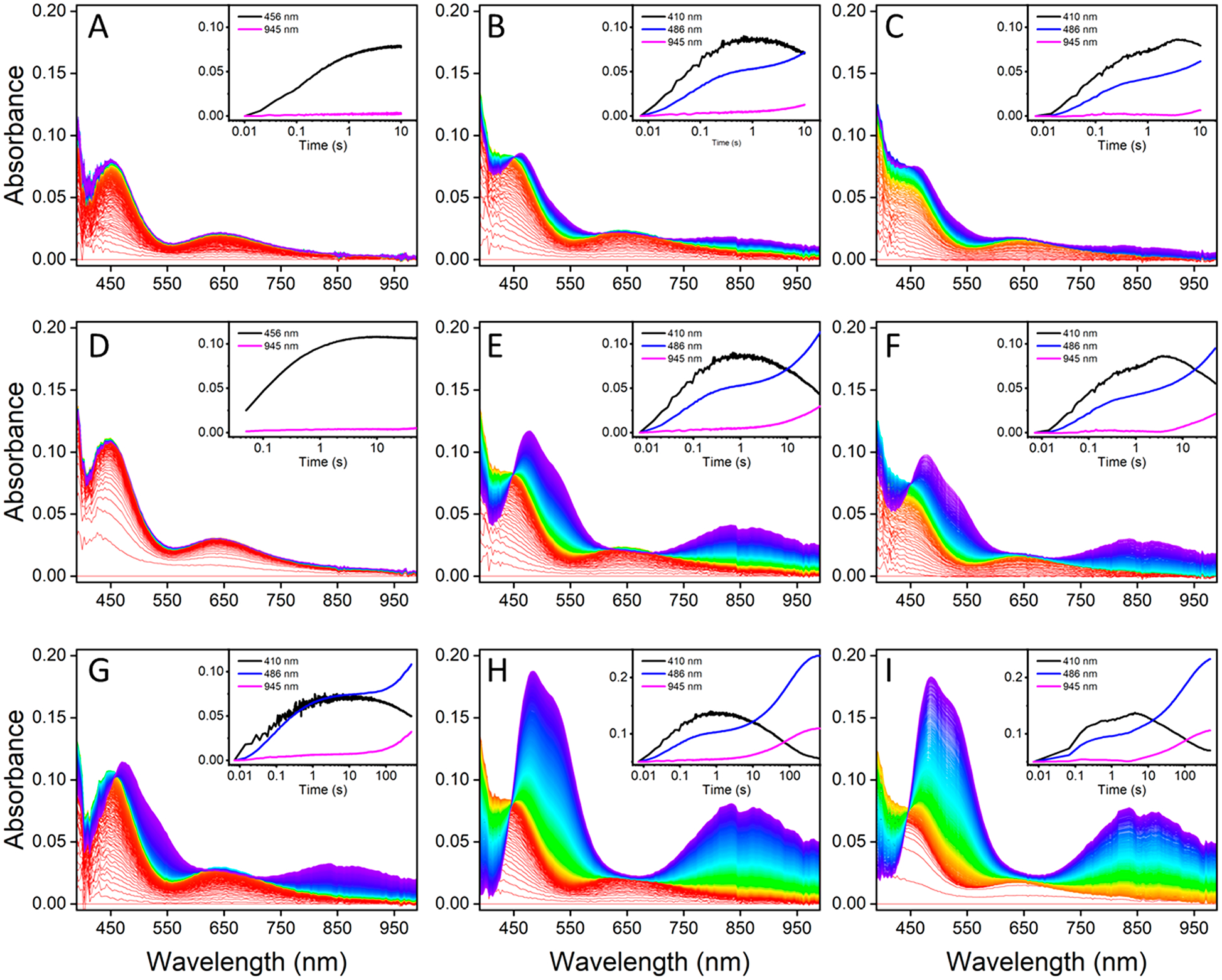

We turned to stopped-flow UV–vis spectroscopy at a controlled lower temperature (15 °C) to investigate whether other short-lived intermediates might be involved in the formation of the T2Cu intermediate or of the final CuA species, such as the transient Cu(II)-SCys-X3 capture complex observed in both Tt CuA and CuAAz and the green Cu-like intermediate Ix in CuAAz.16,17,60 Solutions of either 1 or 2 equiv of Cu(II) were rapidly mixed with apoprotein (100 μM after mixing), and the resulting absorption spectra were collected for a period of 10, 50, or 1000 s under both aerobic and anaerobic conditions (Figure 7A–I). For one equivalent of Cu(II), the spectra collected over the first 10s (Figure 7A) after mixing show a single species with absorption bands at ~450 nm and ~640 nm that we previously identified as the T2Cu intermediate appearing and quickly reaching half-saturation by ca. 100 ms. The detector limitations of our stopped-flow spectrometer at wavelengths lower than ~400 nm prevented us from directly observing the primary absorption peak of the T2Cu species at 375 nm, so the evolution of this species was monitored by its 644 nm feature. The first species remained stable until ca. 23.5 s, beyond which absorbance of the ~840 nm feature indicative of CuA became apparent (Figure 7D,G).

Figure 7.

Stopped-flow difference spectra at 10 s (A–C), 50 s (D–F), and 500 s (G–I) of apo-CuACcP with 1 equiv (parts A, D, G) or 2 equiv (parts B, E, H) of Cu(II) added under aerobic conditions and 2 equiv of Cu(II) added under anaerobic conditions (parts C, F, I). Time-dependent traces of absorption at specific wavelengths associated with either the T2Cu (410, 456 nm) or CuA (486, 945 nm) species with minimal overlap are shown in the insets.

When apoprotein was mixed with 2 equiv of Cu(II), there was little difference between the observable species and their rates of formation under either aerobic or anaerobic conditions over the first 10 s (Figure 7B,C). The development of the CuA species was monitored at its 486 nm peak and at 945 nm (rather than the center of the ~840 nm peak, which overlapped significantly with the broad 641 nm feature of the T2Cu species). Regardless of whether 1 or 2 equiv of Cu(II) were added, a similar maximum amount of the T2Cu species was formed (Figure 7D–F), but with 2 equiv of Cu(II), the onset of CuA features occurred at ca. 3 s, or approximately 10-fold more rapidly than with only 1 equiv of Cu(II). By 50 s, the concentration of the CuA species had reached approximately half-maximum with no absorbance attributable to previously unobserved intermediates, and by 500 s, both the aerobic and anaerobic reconstitutions with 2 equiv of Cu(II) had essentially reached saturation to nearly equal final concentrations of the CuA species (Figure 7H,I). Isosbestic points in the same locations as indicated in Figure 2 are present over all time intervals and copper concentrations that we examined, indicating a purely two-species process.

Early stopped-flow analysis of the Cu reconstitution of engineered CuAAz displayed a very similar apparent CuA formation pathway with a single T2Cu intermediate and which required sacrificial apoprotein disulfide oxidation to reduce Cu(II) to Cu(I) in situ.35 Subsequent stopped-flow experiments at lower temperature (15 °C) and substoichiometric amounts of Cu(II) revealed the presence of additional intermediates including T1Cu and Cu(II)-dithiolate species under aerobic conditions.16,17 These additional species were not observed under similar rapid mixing conditions in CuACcP. Because the Cu(II)-dithiolate intermediate does not form in CuACcP, a major pathway involving O2 and a T1Cu intermediate identified in CuAAz is not available to CuACcP, meaning that CuA evolves directly from the T2Cu intermediate.

The T2Cu intermediate reached the same concentration with 1 or 2 Cu(II) equivalents, suggesting that the available apoprotein readily binds Cu(II) to saturation at stoichiometric concentrations, leaving little to no apoprotein to provide sacrificial reducing equivalents. The T2Cu intermediates must therefore interact with unbound Cu(II) or with each other to produce Cu(I). We fit kinetic models of both mechanisms to the aerobic stopped-flow data: model 1, which involves IT2 interacting with unbound Cu(II) to create an apoprotein with an oxidized disulfide, A(S–S), and 2 equiv of Cu(I) to form CuA from another IT2, was nonconvergent with the stopped-flow data. Model 2 involved a biomolecular interaction of IT2 species disproportionating to yield CuA and an apoprotein radical, A(S•-SH), that can then react with free Cu(II) to form A(S–S) and Cu(I). This model proved to be an excellent fit for the evolution of the T2Cu species: it correctly modeled the exponential appearance of the CuA species following saturation of the T2Cu species without apparent lag and correctly predicted the observed maximum yield of ~70% CuA from Cu(II) alone (Figure S11). The calculated rates for each step in the model are shown in Table 4. The rate of CuA species formation by model 2 is determined by the concentration of IT2, contrary to the increased rate of CuA formation with 2 equiv of Cu(II) that we observed; however, higher Cu(II) concentration did also cause faster T2Cu accumulation (part A vs parts B and C of Figure 7). The calculated rate constants for the relevant steps (k2 and k3) are similar, and it is possible that with excess Cu(II), Cu(II) could drive faster formation of the A(S•-SH) intermediate. Models that combined the model 1 and model 2 pathways did not accurately reproduce the data. It is worth noting that CcP, unlike Az and other native and model CuA proteins, has a large number of oxidizable residues and hole-hopping pathways,61 so the mechanism by which reducing equivalents are generated could be more complicated than a simple S–S forming model.

Table 4.

Rate Constants Calculated from Global Spectral Fitting of the Stopped-Flow Spectra of Cu Incorporation in CuACcP

| Process | Rate (s−1) | St. Dev. (s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apo + Cu(II) → IT2 | kl | 6.86 × 104 | 0.072 × 104 |

| 2 IT2 → A(S•SH) + CuA | k2 | 1.03 × 102 | 0.0071 × 102 |

| A(S•SH) + Cu(II) → Cu(I) + A(S–S) | k3 | 3.40 × 102 | 0.25 × 102 |

| IT2 + Cu(I) → CuA | k4 | 1.76 × 102 | 0.078 × 102 |

Mutation of Key Cu-Binding Residues in CuACcP.

Given the long distance between the position of His175 in native CcP and the putative CuA binding site in CuACcP, we initially questioned whether the CuA species in CuACcP could really have the typical His2Cys2Cu2 core of CuA centers. We studied the effect to Cu binding and formation of both the T2Cu intermediate and the CuA species by systematically mutating the presumed Cu-bindng residues R48C, W51C, His52 as well as His175 and reconstituting the purified mutants with Cu(II) as described above.

Both single mutants R48A and W51A displayed EPR features of T2Cu species in the presence of Cu(II) that were highly similar mixtures of at least two T2Cu species (Figure S12). The UV–vis absorption spectra of the T2Cu species (Figure S13) in these mutants were also similar to each other but distinct from the previously described T2Cu intermediate: both single mutants exhibited blue-shifted d → d transitions at ~620 nm, and the π SCys-to-Cu(II) CT shoulder at ~450 nm was severely reduced or, in the case of R48A, entirely absent. The addition of more than two equivalents of Cu(II) up to 10 equiv did not change the bound Cu species, and no CuA species were formed. The replacement of either R48C or W51C with Ala totally abolished CuA formation, and the T2Cu species that did form differed from the T2Cu intermediate that leads to CuA formation. Additionally, the intensity of all of the principle absorption bands for both Cys-to-Ala mutants was much weaker than when both Cys were present, and approximately 3–5 equiv of Cu(II) were required to reach saturation. Neither T2Cu species was particularly stable and decayed within a few tens of minutes to ~1 h after reconstitution. Owing to the apparent lack of His coordination and relative instability of the Cys → Ala mutants, it is likely that in these mutants Cu(II) is bound only by a single Cys residue, similar to the so-called Cu capture complex observed transiently in nacent CuA in native CuA domains, which has similar spectroscopic features.16,60 The two T2Cu species present in the paramagentic spectra may simply represent two distinct conformations available to the Cu-Cys complex in either mutant.

Mutation of His52 to Ala produced an interesting result: addition of one equivalent of Cu(II) to H52A-CuACcP gave rise to an unstable species with UV–vis absorption features nearly identical to those of the T2Cu intermediate that was formed with His52 but which decayed in ~100 s (Figure S14). Gradual addition of more Cu(II) revealed that the decay of this species accelerated with increasing Cu(II) concentration, suggesting that Cu(II) disproportionation and Cys oxidation may be involved in the T2Cu species decay, and we observed no formation of a CuA-like species. The similarity of the Cu(II)-bound species in the H52A mutant to the green T2Cu intermediate further supports our hypothesis that (1) the T2Cu intermediate is a Cu(II)-2(SCys)-NHis complex, (2) the electronic absorption pattern is determined largely by the Cu(II)-2(SCys) interaction, (3) His52 is necessary to stabilize the complex, and (4) all three residues (R48C, W51C, and His52) are required to form CuA. The Cu(II)-2(SCys)-NHis model of the T2Cu species suggested by the results of Cys → Ala mutations is in conflict with the EXAFS of this species, which suggested only one Cys ligand; however, as we noted, cryoreduction evident in the sample could have led to a significant population of coordinated Cu(I) with a different coordination number and geometry. In the crystal structures of native CcP and of CuACcP, His175, the proximal axial ligand to its heme, appears too distant to form a CuA center in concert with R48C/W51C/His52 (Figure 1B). Nevertheless, His175 is the only nearby His residue other than His52. We sought to test whether His175 is a ligand to CuA by mutating this residue to nonbinding alternatives.

We mutated His175 to Ala to completely remove any potential binding, and to Phe to retain similar sterics. When either mutant was reconstituted with Cu(II), CuA-like species did form after it proceeded through a species highly similar to the green T2Cu intermediate that was formed with His175 (Figure S15). However, these species decayed completely within seconds after forming. This Cu-binding behavior is consistent with the reported effects of mutating His120 in CuAAz,37,38,62 which demonstrated that an endogenous ligand could take the place of one His ligand to form a stable binuclear center. The binuclear species that forms in either H175A- or H175F-CuACcP was not stable and decayed too quickly to reliably capture. However, the binuclear species in the H175F mutant was notably longer lived than in H175A (Figure S15), suggesting that sterics played a role in Cu–Cu bond stability. The stability of the CuA species in the H175A mutant could be increased by the addition of 2 equiv of imidazole during Cu(II) reconstitution, increasing the maximum absorption of the binuclear species by 1.5-fold and causing a blue shift of the ψ → ψ* peak from 864 to 842 nm, which is similar to the peak position with native His175 (higher concentrations of imidazole gave only negligible improvements). The formation of a binuclear species (albeit transient) in the H175A/F mutants demonstrates that Cu capture and reduction in CuACcP do not depend on His175. Further, the ψ → ψ* transition remained near ~840 nm in both H175A/F mutants, indicating that the Cu–Cu bond distance is determined more by the structure of the R48C/W51C/H52 helix/helix terminal loop than by that of the more distant His175. However, replacement of His175 with nonbonding residues resulted in unstable CuA species, which does indicate that His175 is a coordinating residue for the binuclear center and that when His175 is removed, no nearby residues are available to replace it as was observed in CuAAz.

Computational Modeling of the CuA Binuclear Center in CuACcP.

As described above, Cu coordination in CuACcP requires R48C, W51C, and His52 and is stabilized by His175. It is worth noting that His175 natively coordinates heme Fe through the Nε atom and would likely coordinate the binuclear Cu center through the same nitrogen. We therefore anticipate that the remote nitrogens of the two imidazolyl ligands would be inequivalent, which is consistent with what we observed from 14N HYSCORE. Weaker axial ligands in CuA are typically supplied by Met and a backbone carbonyl. The Met residue is more distant (2.9–3.1 Å) and known to modulate the redox potential of CuA centers but not to the same degree as the axial ligands of T1Cu centers.63–65 The crystal structures of native CcP and heme-reconstituted CuACcP indicate that substantial structural deformation is required for the nearest His and Met residues (Met172 and His175) to serve as ligands to the nearest Cu of the binuclear complex if coordinated by R48C/W51C/H52. We therefore generated a plausible CuA site in CuACcP using the CuACcP heme protein crystal structure (Figure S3) as a basis and the diamond core geometry (coordination number, bond lengths, and bond angles) determined from EXAFS to construct an initial Cu-bound state with minimal perturbation to the R48C/W51C/H52 site (Figure 8A). From the results of the H175A/F mutations, we created a bond between His175 and the Cu2 but did not manually adjust the structure to conform to the predicted ~1.9 Å bond length before structure minimization. Given these starting criteria, the backbone carbonyl of R48C appeared as a highly plausible axial ligand, but a Met residue or suitable replacement amino acid were not within typical CuA axial ligand distances, leaving a water molecule as the most plausible second axial ligand, if present. We modeled the thermal equilibration of this site for 20 ns by molecular dynamics (MD) simulation with additional rigid bond and angle parameters applied to the Cu2S2 diamond core to preserve its geometry. The resulting structure is shown in Figures 8B and S16.

Figure 8.

Initial and thermally equilibrated MD structures of CuACcP. (A) Putative structure of the CuA site with copper atoms placed in the X-ray crystal structure of heme-CuACcP based on the bond distances and angles determined from EXAFS of the mixed valent CuA species. The original position of heme (not present when Cu is bound) is drawn transparently. Before movement of the His175 helix, the distance between H175 and the nearest Cu ions is 5.6 Å. (B) CuACcP thermally equilibrated for 20 ns. The average distance between Met172 and Cu2 is indicated.

We note two key changes in the equilibrated structure: first, the backbone hydrogen bonds between residues 50–52 are disrupted by interaction with the Cu coordinated by His52 (Cu1). This disruption appears to be largely due to the preference of the Cys51 backbone carbonyl to interact with Cu1, which causes a rotation of the His52 backbone. Second, His175 rearranges to conform to the short His–Cu bond length during energy minimization, but the structural perturbation required to allow H175 migration to coordinate CuA was less than we anticipated. Only the uncoiling of Ala176 and a shift of the loop region upstream of His175 were required (Figures 8B and S16). The Cu1 is in electrostatic contact with the backbone carbonyl oxygen of R48C, closely mimicking the coordination geometry of the loop in native CuA. No corresponding residue is obviously positioned to act as an axial ligand to the second Cu (Cu2). In the equilibration trajectory, Met172 is 5.6 Å away from Cu2 after initial energy minimization and only moves farther away thereafter (Figure S15). Because heme is not bound when the CuA species is bound, the metal binding site is quite solvent exposed, making water coordination at this site a near certainty. Throughout the equilibration, 2–4 water molecules coordinate to the more exposed Cu2. Our structural modeling, therefore, suggests that the axial ligand for Cu2 is likely to be water, making it a more symmetrical CuA center than the native CuA carbonyl/Met axial ligands. The solvent exposure of the CuA center may also be related to the disorder of the site, particularly of the reduced state, that we found from EXAFS.

Reduction Potential Determination by Redox Titration.

To determine whether CuACcP has the functional ET properties of a cupredoxin, we measured its reduction potential (E°′) by redox titration using [Ru(NH3)5Py]·ClO4 (Figure S17) following a protocol reported previously for CuA.15 As shown in Figure S18, titration of [Ru(NH3)5Py]·ClO4 into CuACcP resulted in a steady decrease in absorbance at 831 nm as the metal center is reduced, finally saturating at ca. 20 equiv of the Ru-complex. The fit to the linear region of the equilibrium constant K (Figure S19) gave E°′ of the CuA center to be 251 mV (vs SHE), which is quite similar to native CuA from COX (240 mV) and CuAAz (254 mV) measured by the same method,15 and these measured values of E°′ are in general agreement with values obtained by other methodologies.64,66–69

Reduction of CuACcP by Cytochrome c.

To validate whether the measured E°′ for CuACcP was accurate and capable of ET to a native redox partner, we tested whether the oxidized CuACcP center could be reduced by cytochrome c (cyt.c), the native redox partner of both the CuA subunits of CcO and of wild type CcP. We added mixed valent CuACcP (final concentration 50 μM) to a 10 μM solution of ferrous bovine type IV cyt.c in an anaerobic chamber to prevent background oxidation by atmospheric oxygen. The oxidation of cyt.c was monitored by the changes in its Soret band (415 nm) and 550 nm peak (Figure S20A). A shift in the cyt.c Soret absorption maximum from 415 to 409 nm as well as loss of intensity at 550 nm were observed, indicative of oxidation from Fe(II) to Fe(III). The change in 550 nm intensity could be modeled as a first order reaction with a rate constant of k = 2.74 × 10−3 s−1 (±1.5 × 10−5 s−1) (Figure S20B). Measuring the ET rate by monitoring reduction of the CuA center at 825 nm (Figure S20C) resulted in an ET rate constant k = 2.24 × 10−3 (±4.8 × 10−5) s−1, which is quite similar to the rate constant we found by monitoring the change in cyt.c oxidation at 550 nm. The rate of ET from ferrous cyt.c to the mixed valent CuA domain of CcO has been measured with a rate of k ~ 105−106 s−1.70 The ET rate of reduction of Fe(III)-cyt.c from beef heart type IV cytochrome c (the same type used by us) by Fe(II)-WT CcP has been reported to be 0.2 s−1 (also determined as a first order rate constant) and to be only minimally impacted by relative protein concentrations.71 This is in contrast to the very fast rate of ET from Fe(II)-cyt.c to the high-valent Fe(IV)=O Compound-I species (E°′Fe(III)/CMPDI = 0.740 V) formed after WT CcP reacts with H2O2 that is natively reduced by Fe(II)-cyt.c (104−105 s−1 under very low ionic strength conditions). Presumably, the same surface interactions are involved in ET to CuACcP. However, the driving force between Fe(II)-CcP (E°′Fe(III)/Fe(II) = −0.198 V) and Fe(III)-cyt.c (E°′Fe(III)/Fe(II)= 0.254 V) is significantly greater than that with mixed valent CuACcP (E°′Cu(1.5)Cu(1.5)/Cu(I)Cu(I) = 0.251 V), so we should expect the ET rate to be significantly slower, on the scale of several orders of magnitude, as we observed.

DISCUSSION

The electronic, X-ray absorption, rR, and MCD spectra of CuACcP all point to a stable CuA center in the class III mixed valence state. The CuA designed in CcP contains all the essential features of native and engineered CuA centers in cupredoxins, including charge delocalization and redox potential. The CuA center in CuACcP also reproduces the key CT features of native CuA proteins that model complexes have failed to capture, and it has demonstrated some ET function. The EPR features of CuA in CuACcP, however, resemble an axially perturbed CuA, and the hyperfine structure is not resolved.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of CuACcP is that there is virtually no structural homology between the CuA center in CcP, a heme peroxidase formed of mainly α-helices, and all characterized natural CuA subunits, which have cupredoxin folds. However, common between these two unrelated folds is the arrangement of the Cu-binding residues: the cupredoxin fold conserves a loop comprising three of the primary coordinating residues, one His and two Cys residues, as well as the weaker axial Met and carbonyl ligands. The second His is located on a separate loop with the surrounding structure composed of β-sheets. From a coarse perspective, the structure of the Cu-binding site in CuACcP is similar. R48C, W51C, and His52 are located on the same α-helix in a rigid conformation, and His175 is located on a second α-helix oriented parallel to the first. This arrangement of the primary coordinating residues creates a spatially—if not necessarily structurally—homologous primary coordination sphere for CuA. The spatially locked residues R48C/W51C/H52 apparently form a copper chelating site that rapidly binds Cu(II) to form the T2Cu intermediate before the second equivalent of copper binds. Kinetic modeling of CuA formation suggests that the dissociation constant is Kd ≈ 15 μM for the first Cu(II) and that the binding occurs an order of magnitude faster than in CuAAz.35 Transition from the T2Cu species to CuA is also more complex than a simple A → B → C model as in CuAAz in the presence of excess Cu. This more complex mechanism is possibly related to the lower accessibility of the CuACcP binding site: though it is fully solvent exposed, it is located within the core of the protein unlike the surface-accessible cupredoxin CuA sites. CcP also has a greater capacity than CuAAz to provide reducing equivalents and stabilize oxidized residues,61 so there are potentially multiple routes to generating Cu(I) in situ other than the known disulfide oxidation mechanism.

Mutations to R48C or W51C severely impair Cu binding, and R48C, W51C, and His52 abolish CuA formation, making it clear that this amino acid triad is critically important for recruiting the first Cu(II) and stabilizing the binuclear center; the same is true of the conserved loop residues of CuA and T1Cu centers. Nevertheless, formation of a CuA center in the CuACcP site is still far from easily predicted, in no small part due to the great distance between His52 and His175 in their native conformations. Mutation of His175 to noncoordinating residues Ala and Phe demonstrated that this distant His residue is clearly important to stabilize the CuA structure and is most probably a Cu ligand. This conclusion is supported by the presence of HYSCORE cross-ridges from two inequivalent nitrogen ligands that may derive from Nδ coordination at His52 and (presumed) Nε coordination at His175. Furthermore, while an axial carbonyl ligand is potentially supplied by R48C, the lack of an obvious replacement for the conserved Met axial ligand in CuACcP provides some insight into the inequivalent Az hyperfine coupling constants for each Cu. The Cu binding site in CuACcP is solvent exposed, and water is the most likely axial ligand to Cu2 (Figure 8B). The combination of a carbonyl/water axial pair compared to a carbonyl/Met pair may contribute to the unusually small Az values, which conforms to the trend observed in CuAAz and its axially perturbed mutants.

Given the tight arrangement of R48C/W51C/H52 in the CuACcP heme protein crystal structure, we predict that His175, located at the negative pole of a different helix, deforms from its native conformation when the heme cofactor is absent. Indeed, subsequent simulations of the apo-CuACcP structure that we performed with His175, H175A, and H175F found that both native His175 and the H175F mutant prefer a collapsed structure that relieves tension in the heme-binding helix when heme is absent. This alternate “apo” conformation is facilitated by rearrangement of the H175/W191/D235 conserved hydrogen bonding network found in peroxidases (Figure S21). Though the structures predicted by these simulations are difficult to verify, the presence of a stable, redox active CuA center in a site that requires deformation to accommodate it is good evidence that there could be a much larger space of metalloproteins whose cofactor binding sites are more malleable than previously thought, providing a broader array of exploitable stable protein folds for artificial metal-loenzyme design.

A key observation from this model, therefore, is the straightforward demonstration that a highly specialized protein fold is not necessary to induce certain characteristic physical and chemical properties in a metal redox center. Protein folds are frequently repurposed in nature to accomplish highly disparate functions. However, purposefully building a metal binding site, particularly a multinuclear metal center, in a non-native scaffold remains challenging, and it is generally considered too difficult to attempt in nonhomologous protein scaffolds that might have otherwise attractive properties. Yet recent success with symmetrical binding sites in de novo proteins and by the use of broader elements of protein scaffold structure such as cavity and backbone structure72 have shown that strict biomimicry is not necessary to build metal sites with properties similar to their natural counterparts. In the case of CuACcP, the minimally necessary components for a mixed valence binuclear Cu center were three of the primary binding residues arranged to provide a rigid binding site for the first Cu(II) with the fourth residue positioned to provide space, symmetry, and stability to the second Cu. However, there are clearly limitations to this minimalist design. While CuACcP does exhibit some ET functionality, with k ~ 3 × 10−3 s−1, it is clearly inferior to the efficiency of native CuA proteins that exhibit a rate of k ~ 105−106 s−1,70 despite having an appropriate redox potential. A major contributing factor to such a slow ET rate in CuACcP is the scaffold of CcP, because the first order ET rate constant of the oxidation of type IV cyt.c by ferrous WT CcP is only k = 0.2 s−1,71 with a substantially greater driving force of (~0.45 V) than between cyt.c and mixed valent CuACcP, which is close to zero. However, the factors that contribute to ET rate (E°′, reorganization energy, and valence orbital structure) can be heavily modulated by fine-tuning in the second coordination sphere, as has been demonstrated definitively for T1Cu centers.8,65,73 It has also been shown that the same SCS mutations made in different cupredoxins cause quantitatively similar changes from different initial E°′.74 Therefore, with sufficient tuning through stabilizing SCS interactions, it is possible that an artificial ET protein like CuACcP could be engineered to have ET efficiency on-par with a native ET protein despite starting from a different scaffold.

CONCLUSIONS

Using a nonhomologous heme protein as a scaffold, we created a binuclear Cu binding site with electronic, redox, and ET properties that closely reproduce the properties of native CuA centers. We obtained evidence of a binuclear Cu center in CuACcP that constitutes a class III mixed valence system with a Cu–Cu bond and a redox potential comparable to native CuA centers. The CuA species in CuACcP exhibits the smallest reported Az hyperfine constant and gz area in a CuA species while still demonstrating electron transfer function to a native CcP redox partner. The creation of this site demonstrates a minimalist approach to the necessary and sufficient elements to design a complex metal binding site inside a protein scaffold. Our design of a multinuclear redox center in a protein scaffold without the aid of exogenous ligands shows that it is possible to design complex metal binding sites in proteins that achieve biomimicry without rigidly adhering to the conserved structural elements of their natural counterparts. In principle, this work demonstrates that complex metal sites can be engineered heuristically in unrelated protein scaffolds that have suitable cavities by first using basic principles of primary coordination to achieve metal binding, followed by the fine-tuning of desirable properties.

METHODS

Protein Mutation, Expression, and Purification.

Mutations were made to an E. coli codon-optimized gene for cytochrome c peroxidase by site-directed mutagenesis via PCR with primers containing the desired mutant sequence. The gene was contained within a pET-17b plasmid bearing an ampicillin resistance cassette. Mutant proteins were transformed into BL21-DE3 high-efficiency chemically competent E. coli (New England Biolabs) and expressed and purified by a protocol previously described and modified by our lab.28,72,75 Briefly, cells were cultured overnight in LB (rich) media, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, and pelleted after 3–4 h of expression. Cell pellets were lysed by sonic disruption, and the clarified soluble supernatant was subjected to anion exchange chromatography (DEAE Sepharose Fast Flow anion exchange resin, GE Healthcare) in phosphate buffer (50 mM, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0) eluted on a linear gradient of potassium chloride (0–500 mM) followed by gel filtration chromatography (Sephacryl S-100 HR, GE Healthcare) in potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0). The major peak fractions were pooled, assessed for purity by mass spectrometry (ESI-MS), and further purified as necessary by separation on Q Sepharose Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) strong anion exchange resin (eluted on a linear potassium chloride gradient) until the hemoprotein content was minimal.

Copper Reconstitution.

Copper was added to apo-CuACcP from 20 mM stock solutions of CuSO4 and Cu(I). The Cu(I) solution was prepared by comproportionation: ~0.5 g of polished pieces of Cu wire was added to 1 mL of a 10 mM CuSO4 in a 1 M acetonitrile aqueous solution and allowed to incubate overnight in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories). The Cu wire was cleaned for at least 1 h in 500 mM EDTA to remove the Zn coating and then washed thoroughly to remove all EDTA prior to use. Copper solutions were added as described to apoprotein in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4, made metal-free by stirring overnight with Chelex resin) in a quartz cuvette stirred by a magnetic bar. The temperature of the cuvette was maintained by a circulating water bath.

UV–Visible Spectroscopy.

All UV–vis absorption spectra were collected on an Agilent 8543 spectrophotometer, setup under normal atmosphere or in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories) as specified. Plots were prepared with Origin 2018b software. Stopped-flow spectra were collected on an Applied Photophysics, Ltd. SX18.MV stopped-flow spectrophotometer equipped with a 256-element photodiode array detector. Equal volumes of 0.2 mM apoprotein and either 0.2 mM or 0.4 mM Cu solutions, both in metal-free (Chelex) Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4), were simultaneously injected. Spectra were recorded on a logarithmic scale over the time periods indicated with an initial sampling frequency of 1 ms. For anaerobic stopped-flow experiments, both apoprotein and Cu solutions were prepared in an anaerobic chamber and transferred to gastight syringes. The stopped-flow apparatus was thoroughly washed with buffer degassed on a Schlenk line immediately prior to sample injection. Temperature control was maintained at 15 °C by a circulating water bath and jacket around the injection chamber. Global fit analyses of the stopped-flow difference spectra data were performed with SpecFit/32 with the data trimmed to remove the high- and low-wavelength limits of the detector.

Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Spectroscopy.

Protein samples were prepared with Cu as described, concentrated by mini (0.5 mL) Amicon Ultra-0.5 Centrifugal Filter Units (10000 Da MW cutoff, Millipore Sigma), and diluted and thoroughly mixed with ethylene glycol (30%, v/v final) to a final volume of ~0.3 mL before being rapidly frozen in a quartz EPR tube by immersion in dry ice cooled acetone or isopentane. Samples were stored in liquid nitrogen until measurement. Protein samples concentrated to >1.0 mM rapidly deteriorated, so samples were generally concentrated only to 0.5–0.8 mM. EPR data were collected on an X-band Varian E-122 spectrometer at the Illinois EPR Research Center (IERC). Spectra of the CuA-like species were collected at 30 K using a liquid He cryostat. Type 2 Cu species spectra were measured at 77 K immersed in a liquid nitrogen dewar with a quartz window. Spectra were simulated with SIMPOW6.76 Plots were prepared with Origin 2018b software. Pulsed EPR experiments were performed as previously described.54

X-ray Absorption Spectroscopy.

XANES and EXAFS data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) on beamline 9−3: a wiggler side-station with a Canberra 100-element Ge monolith solid-state detector with maximum count rates below 120 kHz. Data were collected in fluorescence mode operating at 3 GeV with an optimal current of 500 mA. Soller slits and a 3 μm Z - 1 filter (Ni) were installed between the samples and the detector to minimize back scattering and Kβ fluorescence. The edge energy was calibrated against a Cu foil reference (8979 eV) placed downstream of the I1 ion chamber that was scanned simultaneously with all samples. Samples were scanned 6 times over three positions in each sample to minimize cryoreduction. Samples were maintained at a temperature of 8–10 K with liquid He flow during data acquisition. Data merger, background correction, and EXAFS simulations were all performed with the Demeter software suite (Athena and Artemis).

Resonance Raman spectroscopy.

Resonance Raman (rR) samples were prepared by addition of Cu(II) and Cu(I) to apoprotein. The rR samples were excited at 840 nm using continuous wave excitation from a Lighthouse Photonics Sprout-G pumped SolsTiS-PX Ti: Saph laser with a power of ~100 mW at the sample. The sample was immersed in a liquid nitrogen cooled (77 K) EPR finger dewar (Wilmad). Data were recorded while rotating the sample manually to minimize photodecomposition. The spectra were recorded using a Spex 1877 CP triple monochromator with a 1200 grooves/mm holographic grating and detected by an Andor iDus CCD cooled to −80 °C. Spectra were energy calibrated with citric acid. The protein spectra were normalized to the ice peak at ~230 cm−1. The rR data was processed using SpectraGryph version 1.2 (Dr. Friedrich Menges Software-Entwicklung, Oberstdorf, Germany) and Origin 2018b software.

Magnetic Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy.

Measurements were performed on a Jasco J730 spectropolarimeter (NIR: liquid nitrogen cooled InSb detection; visible: S20 PMT detection) equipped with an Oxford Instruments SM4000–7 T superconducting magneto-optical dewar. Samples of Cu(II)/Cu(I)-reconstituted CuACcP (0.6 mM) and apoprotein (0.8 mM) in Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) were diluted with ethylene glycol (60% v/v, to glass), injected into sample cells composed of two quartz disks separated by a Viton O-ring spacer, and carefully frozen in liquid nitrogen. The sample temperature was measured with a calibrated Cernox resistor (Lakeshore Cryogenics) inserted into the MCD cell. The data were corrected for zero-field baseline effects induced by glass cracks by subtracting the 0 T scan. The final data reported are an average of the positive and negative field data ([7T- (−) 7T]/2). ΔεMCD (M−1cm−1) was calculated using the relation: ΔεMCD = mdeg/(32.98cl) where c is sample concentration (mM) and l is the path length (cm). The Co/Do at 5 K and 7 T for the MCD band at ~11900 cm−1 relative to the absorption at 288 K was calculated using the areas under the MCD and absorption bands. The band energy and its error of the NIR MCD feature in the Table 3 were calculated from the Gaussian fit to the NIR MCD data.

Structural Modeling and Molecular Dynamics.

Coordinates for the 3D structure of the CuA-like species in CuACcP were taken initially from the refined crystal structure of CuACcP with heme-bound protein that was crystallized without the addition Cu (see SI for detailed methods of protein crystallization and structure refinement). The binuclear Cu center was created from the bond lengths and bond angles determined from the best fit EXAFS simulations of the oxidized binuclear species. Cu ions were manually placed, and any mutations were made to the model in WinCoot. Solvated and charge-balanced models of CuACcP were prepared in VMD,77 and all-atom molecular dynamics thermal equilibration simulations were conducted with NAMD2.78 Extra bond parameters with strong spring constants, k (200–500), of the harmonic potential U(x) = k(x – x0)2 for bonds and angles and U(x) = k(1 + cos(nx − x0)) for dihedral angles were applied to the Cu-coordinating atoms to preserve the CuA core structure determined from EXAFS. Simulations were run at 298 K for 20 ns using 2 ps equilibration intervals.

Redox Titration.

[Ru(NH3)5Py]·ClO4 (Py = pyridine) was synthesized as previously reported.79 The redox potential of the synthesized compound (ERu) was standardized by cyclic voltammetry (CV) measured with a CH Instruments Model 620A Electrochemical Analyzer using a standard 3-electrode cell with a pyrolytic graphite edge (PGE) working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference, and Pt wire counter. CV experiments were carried out at ambient temperature in Ar-purged Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4) with 5 mM of the Ru complex. For redox titration, an electrochemical titration cell was assembled in an anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratories) from a 2 mL quartz cuvette with a magnetic stir bar. Measurements were taken at 20 °C maintained by a circulating water bath. Subequivalents of the Ru complex were added in 3.65 μL aliquots to a 150 μM solution of the oxidized CuA species, and the UV–vis absorption spectrum of the solution was monitored at 831 nm; this wavelength was chosen as a well-resolved peak of the protein absorption band in a region where the Ru complex did not significantly contribute to absorption. Corrections were made for dilution. The following reaction was presumed: the apparent equilibrium constant (K) was calculated at every Ru complex concentration according to the equation where A°831, A831, ε831, and [Ru]tot are the initial absorbance of oxidized CuACcP at 831 nm, absorbance of CuACcP at every measurement interval, the extinction coefficient at 831 nm, and the total concentration of [Ru(NH3)5Py]2+/3+, respectively, extrapolated in the linear region to zero concentration to determine the “true” K by a previously reported method.15 The equilibrium constant K is related to the concentrations of both CuACcP and the Ru complex, and the reduction potential of the CuA species can be calculated as where R, T, n, and F are the ideal gas constant, the experimental temperature in Kelvins, the number of electrons (n = 1) associated with the redox process, and the Faraday constant, respectively.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This investigation was supported by the US National Science Foundation under CHE-1710241 to Y.L. and the National Institutes of Health under R01DK031450 to E.I.S. Some EPR data were collected using an X-band EPR Spectrometer purchased with fund from the US National Science Foundation under 1726244. The pulsed EPR data were collected using Grant DE-FG0208ER15960 (to S.A.D.) from the Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences Division, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Office of Sciences, U.S. Department of Energy. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light-source, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103393). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH. We thank Dr. Mark J. Nilges for his help analyzing X-band EPR spectra, Prof. Robert Gennis for use of his stopped-flow instrument, Quan Lam for her help collecting pulsed EPR spectra, Prof. Martin Gruebele and Mayank Murlidhar Boob for their help collecting CD data, and Shengsong Yu for his help with protein preparation.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c04226.

(CIF)

Additional methods for data collection of heme-protein XAS and X-ray crystallography; native ESI-MS; CD; and calculations and equations associated with pulsed EPR data. Additional Tables of previously published EPR and 1H HYSCORE data; fitting parameters for XAS simulation; and X-ray crystal structure refinement. Additional figures of copper titration and EPR for various mutants; redox titration; and structure simulation (PDF)

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/jacs.0c04226

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Contributor Information

Evan N. Mirts, Department of Chemistry and Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

Sergei A. Dikanov, Department of Veterinary Clinical Medicine, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

Anex Jose, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

Edward I. Solomon, Department of Chemistry, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305, United States.

Yi Lu, Department of Chemistry and Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, Illinois 61801, United States.

REFERENCES

- (1).Gray HB; Malmström BG; Williams RJP Copper Coordination in Blue Proteins. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2000, 5 (5), 551–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Hwang HJ; Lu Y PH-Dependent Transition between Delocalized and Trapped Valence States of a CuA Center and Its Possible Role in Proton-Coupled Electron Transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2004, 101 (35), 12842–12847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Donaire A; Jiménez B; Fernández CO; Pierattelli R; Niizeki T; Moratal J-M; Hall JF; Kohzuma T; Hasnain SS; Vila AJ Metal–Ligand Interplay in Blue Copper Proteins Studied by 1H NMR Spectroscopy: Cu(II)–Pseudoazurin and Cu(II)–Rusticyanin. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124 (46), 13698–13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Solomon EI; Szilagyi RK; DeBeer George S; Basumallick L Electronic Structures of Metal Sites in Proteins and Models: Contributions to Function in Blue Copper Proteins. Chem. Rev 2004, 104 (2), 419–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Lancaster KM; Yokoyama K; Richards JH; Winkler JR; Gray HB High-Potential C112D/M121X (X = M, E, H, L) Pseudomonas aeruginosa Azurins. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48 (4), 1278–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Warren JJ; Lancaster KM; Richards JH; Gray HB Inner-and Outer-Sphere Metal Coordination in Blue Copper Proteins. J. Inorg. Biochem 2012, 115, 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Marshall NM; Garner DK; Wilson TD; Gao Y-G; Robinson H; Nilges MJ; Lu Y Rationally Tuning the Reduction Potential of a Single Cupredoxin beyond the Natural Range. Nature 2009, 462 (7269), 113–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Hosseinzadeh P; Marshall NM; Chacón KN; Yu Y; Nilges MJ; New SY; Tashkov SA; Blackburn NJ; Lu Y Design of a Single Protein That Spans the Entire 2-V Range of Physiological Redox Potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113 (2), 262–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Randall DW; Gamelin DR; LaCroix LB; Solomon EI Electronic Structure Contributions to Electron Transfer in Blue Cu and CuA. JBIC, J. Biol. Inorg. Chem 2000, 5 (1), 16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]