Abstract

Early recognition of Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) cases could impact on the management and outcome of this subset of B-lineage ALL. In order to assess the prognostic value of the Ph-like status in a pediatric-inspired, minimal residual disease (MRD)- driven trial, we screened 88 B-lineage ALL cases negative for major fusion genes (BCR-ABL1, ETV6-RUNX1, TCF3-PBX1 and KTM2Ar) enrolled in the GIMEMA LAL1913 front-line protocol for adult BCR/ABL1-negative ALL. The screening - performed using the “BCR/ABL1-like predictor” - identified 28 Ph-like cases (31.8%), characterized by CRLF2 overexpression (35.7%), JAK/STAT pathway mutations (33.3%), IKZF1 (63.6%), BTG1 (50%) and EBF1 (27.3%) deletions, and rearrangements targeting tyrosine kinases or CRLF2 (40%). The correlation with outcome highlighted that: i) the complete remission rate was significantly lower in Ph-like compared to non-Phlike cases (74.1% vs. 91.5%, P=0.044); ii) at time point 2, decisional for transplant allocation, 52.9% of Ph-like cases versus 20% of non-Ph-like were MRD-positive (P=0.025); iii) the Ph-like profile was the only parameter associated with a higher risk of being MRD-positive at time point 2 (P=0.014); iv) at 24 months, Ph-like patients had a significantly inferior event-free and disease-free survival compared to non-Ph-like patients (33.5% vs. 66.2%, P=0.005 and 45.5% vs. 72.3%, P=0.062, respectively). This study documents that Ph-like patients have a lower complete remission rate, event-free survival and disease-free survival, as well as a greater MRD persistence also in a pediatric-oriented and MRD-driven adult ALL protocol, thus reinforcing that the early recognition of Ph-like ALL patients at diagnosis is crucial to refine risk-stratification and to optimize therapeutic strategies. Clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 02067143.

Introduction

Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) accounts for 15-30% of B-lineage ALL, with an increasing incidence starting from adolescence. The growing interest in this subgroup of ALL arises from the distinctive gene expression profile - that resembles that of the true Ph-positive cases - and by the unfavorable clinical outcome.1,2 In-depth and large-scale genetic characterization has shown that the majority of Ph-like ALL cases carry fusion genes involving tyrosine kinases (i.e., ABLclass and JAK2 rearrangements), or cytokine receptor rearrangements (i.e., P2RY8/CRLF2 and IGH/CRLF2), frequently associated with mutations of the JAK/STAT pathway genes.3-5 Among the other co-operating events, a relevant role is played by IKZF1 deletions present in about 70% of cases.4-7 The possibility of recognizing these cases at diagnosis has important prognostic implications and would also pave the way to testing tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) and other targeted therapeutic approaches that have proven successful in pre-clinical models and in vivo in a few relapsed patients.3,8-12 So far, several strategies13-15 have been reported in an attempt to identify Phlike cases, but none of them is deemed as the gold standard for the diagnostic work-up of these patients. To this end, our group recently reported a predictive tool called “BCR/ABL1-like predictor” based on the levels of expression of nine genes together with CRLF2 transcript quantification. 7 From a clinical standpoint, Ph-like patients are characterized by a worse outcome which is due to an inferior response to induction therapy, a higher incidence of relapses and lower survival.1,2,4 Since minimal residual disease (MRD) is considered today the most important prognostic factor in ALL, the role of the Ph-like status has been investigated in the context of MRD-driven protocols, with contradicting results. Roberts and colleagues reported in a pediatric cohort that Ph-like patients, though displaying higher MRD levels at the end of induction, had a survival probability similar to that of non-Ph-like childhood ALL when treated with intensive therapies.16 Opposite results were obtained by Heatley et al.14 who demonstrated that, despite a risk-adjusted treatment approach, a high rate of relapse was recorded among children who were retrospectively identified as Ph-like. In adolescents and young adults, the results of the CALGB10403 trial, based on a pediatric inspired regimen, have shown that parameters associated with inferior survival rates were indeed represented by the Ph-like signature and obesity.17 In adult cohorts, all reported studies so far agree on a shorter survival likelihood for Ph-like ALL compared to non-Ph-like patients.5-7,18,19 However, the data are still insufficient to elucidate whether intensive treatments are capable of abolishing the negative impact of the Ph-like status on prognosis: conflicting results have been reported in the studies by Jain et al.20 and Herold et al.6 Likewise, the role of the Ph-like status in the context of MRD-driven clinical trials is still unclear, since the data produced by the German study group were derived from a small cohort of patients.6

In order to clarify these aspects, we hereby evaluated the incidence and clinical-biologial features of Ph-like cases - identified using the BCR/ABL1-like predictor7 - and the prognostic role of the Ph-like profile in terms of complete remission (CR) achievement, MRD persistence and survival in a cohort of adult ALL patients homogeneously and intensively treated in the pediatric-oriented, MRDdriven LAL1913 GIMEMA front-line protocol for adult Phnegative ALL.

Methods

Study population and experimental strategy

This study included B-lineage ALL patients negative for major molecular aberrations (BCR/ABL1, KT2MA and TCF3/PBX1, BNEG) enrolled in the GIMEMA LAL1913 front-line clinical trial (clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 02067143; Online Supplementary Figure S1) - designed for Ph-negative ALL patients aged 18-65 years - based on a pediatric-oriented backbone, in which Pegasparaginase was administered instead of asparaginase, and on a MRD-driven transplant allocation;20MRD time-points and MRD analysis are detailed in the Online Supplementary Materials and Methods. The EC study number approval is 5629.

Diagnostic bone marrow samples were available from 105 patients (median age 38.7 years, range, 18.2-64.7). Baseline patients’ characteristics are summarized in the Online Supplementary Table S1; there were no differences in clinicalbiologial features between our cohort and the remaining population enrolled in the protocol (Online Supplementary Table S2). All cases underwent centralized molecular screening: i) the “BCR/ABL1-like predictor” assay, ii) sequencing of the JAK/STAT and RAS cascades by next-generation sequencing (NGS), iii) Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA), iv) targeted RNA sequencing. In 17 cases, the BCR/ABL1-like predictor was not feasible due to lack of RNA (Online Supplementary Table S3; Online Supplementary Figure S2).

BCR/ABL1-like predictor

In order to detect the Ph-like cases, we applied the “BCR/ABL1-like predictor”7 to 88 patients (Online Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Screening of recurrent mutations and deletions

The members of the JAK/STAT (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, IL7R and CRLF2) and RAS (FLT3, NRAS, KRAS and PTPN11) pathways (181 amplicons) were sequenced by NGS (Online Supplementary Materials and Methods).

NGS experiments were performed in 91 cases (74 in common with the BCR/ABL1-like predictor analysis - 24 Ph-like and 50 non-Ph-like ALL cases -, Online Supplementary Materials and Methods and Table 3). Variants recognized as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) were excluded, unless of prognostic value or previously reported in Ph-like ALL.21

Recurrent deletions (IKZF1, CDKN2A/2B, PAX5, EBF1, BTG1, RB1, ETV6 and CRLF2) were screened in 87 samples (70 in common with the BCR/ABL1-like predictor analysis - 22 Ph-like and 48 non-Ph-like ALL cases -, Online Supplementary Table S3), by the Salsa MLPA P335 ALL-IKZF1 kit (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) and analyzed according to the Coffalyser manual.22 P2RY8/CRLF2 was inferred when a deletion within the PAR1 region was documented. Samples were defined IKZF1+ CDKN2A/2B and/or PAX5 when IKZF1 deletion cooccurred with CDKN2A/2B and/or PAX5 deletions.23

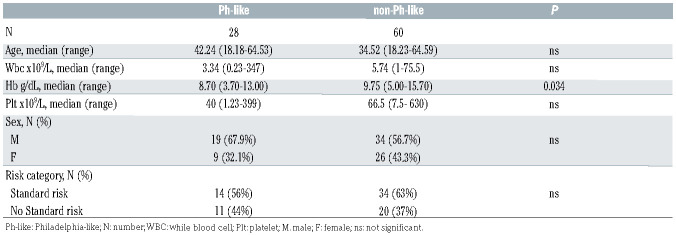

Table 1.

Comparison between Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) and non-Ph-like clinical features.

Targeted RNA-sequencing and FISH analysis

In order to detect fusion genes, libraries were prepared using the TruSight RNA Pan-Cancer Panel (Illumina, San Diego, CA) kit, targeting 1385 cancer- genes (Online Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Double-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies were performed in 20 B-ALL, 13 Ph-like and seven non-Ph-like with high levels of CRLF2 expression (Online Supplementary Materials and Methods).

Overall, 85 cases were screened (25 Ph-like and 60 non-Ph-like ALL cases, Online Supplementary Table S3).

Statistical analyses

Patients’ characteristics were compared by chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon test for continuous data. Overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS) and event-free survival (EFS) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier product-limit and compared by log-rank test. OS was defined as the time between the date of diagnosis and death for any cause; patients still alive were censored at the time of the last follow-up. DFS was defined as the time between the evaluation of CR - after the induction phase - and relapse or death in CR; patients still alive in first CR, were censored at the time of the last follow-up. Finally, EFS was defined as the time between diagnosis and non-achievement of CR in the induction phase, relapse or death in CR, whichever occurred first; patients still alive, in first CR, were censored at the time of the last followup.

Multivariate analysis was performed with the Cox proportional hazards regression model to adjust the effect of BCR/ABL1-like predictor for clinically relevant parameters (age, white blood cell [WBC] count, hemoglobin [Hb] level, platelet count, sex and allogeneic transplant [HSCT] and for genetic aberrations impacting on prognosis [IKZF1+ CDKN2A/2B and/or PAX5, K/NRAS clonal mutations, JAK/STAT clonal mutations]. 21,22 All tests were 2-sided, accepting P<0.05 as statistically significant. All analyses relied on the SAS v9.4 software. Study data were collected and managed using REDCap24 electronic data capture tools hosted at the GIMEMA Foundation.

Results

Incidence and clinical features of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia

We identified 28 (31.8%) Ph-like cases with a median score of 0.85 (range, -0.18 to 6.37); the remaining 60 cases had a median score equal to -1.24 (range, -1.7 to -0.33). Overall, the clinical features (age, sex, WBC and platelet counts) at diagnosis of Ph-like and of non-Ph-like cases were similar. Ph-like patients had lower Hb levels (P=0.016), as detailed in Table 1. The incidence of Ph-like ALL cases was slightly higher in adults (≥36 years) than in young adults (18-35 years), being 36.2% (17 of 47) and 26.8% (11 of 41), respectively. As per clinical protocol guidelines, only 45% of Ph-like cases were assigned to the high-risk category.

Genetic features of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia cases

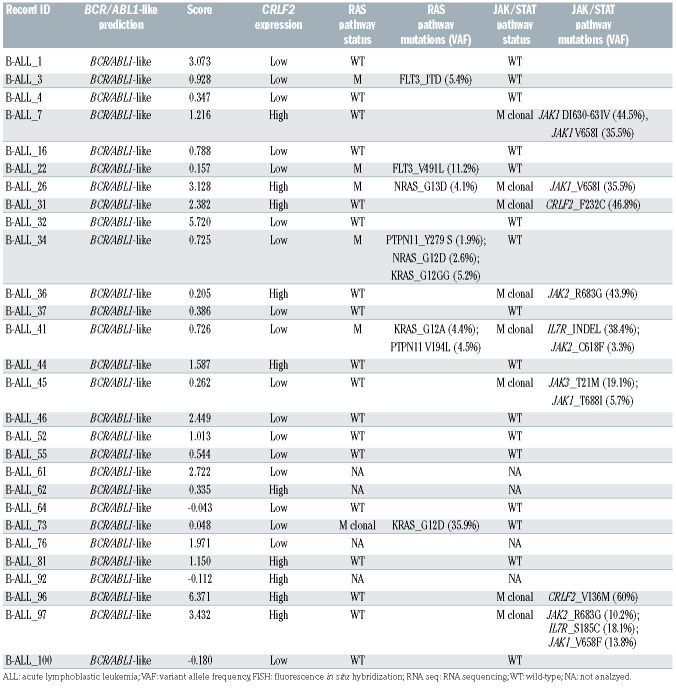

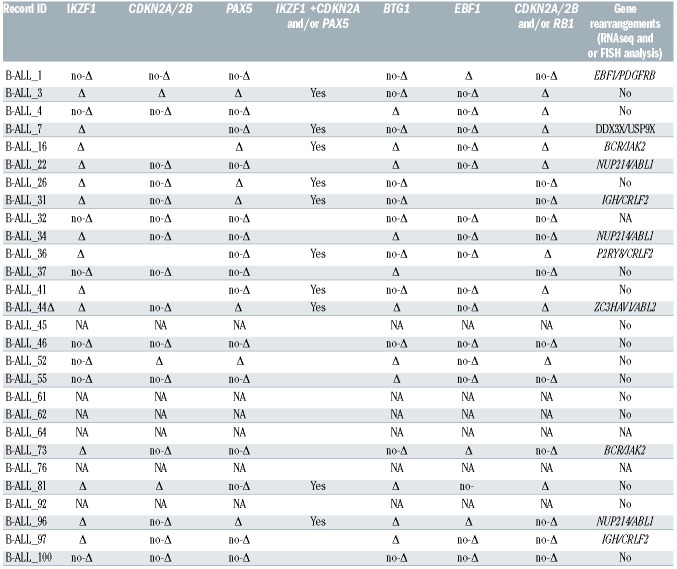

The identified Ph-like cases were evaluated for the following genetic features: CRLF2 expression levels (n=28), JAK/STAT and RAS pathways mutations (n=24), CNA aberrations (n=22) and fusion genes (n=23), the latter either by RNA-sequencing and/or FISH. A CRLF2 overexpression, defined as ΔCt <8,25 was found in 10 of 28 Phlike cases (35.7%). Among the CRLF2-high cases with a ΔCt value <4.5, we observed that three harbored a CRLF2 rearrangement, with one displaying a concomitant F232C CRLF2 mutation. Of the remaining seven CRLF2-high cases, three had a concomitant rearrangement (two ABLclass and one DDX3X/USP9X), one displayed a JAK1 and RAS mutation, and in two cases the mutational screening could not be performed due to lack of genomic material; finally, in one case no additional lesions were detected. Among the 24 Ph-like cases analyzed for the mutational status, we detected a total of 13 JAK/STAT pathway mutations - nine clonal and four subclonal - in eight cases (33.3%). Despite a high heterogeneity among samples, the most frequently mutated genes were JAK1 - affected by five mutations mainly targeting the hotspot V658 - and JAK2 - affected by three mutations focused in the hotspot R683. IL7R and CRLF2 were mutated in two samples, while JAK3 only in one. Furthermore, six of the eight mutated samples (75%) displayed a concomitant CRLF2 overexpression. Nine RAS pathway mutations - only one being clonal - were found in six patients (25%). The most frequent mutations (n=5) involved the hotspot G12-13 of KRAS and NRAS. CNA analysis in Ph-like cases revealed IKZF1, BTG1, CDKN2A/2B, PAX5 and EBF1 deletions in 14 (63.6%), 11 (50%), seven (31.8%), seven (31.8%) and six (27.3%) cases, respectively. Furthermore, IKZF1 + CDKN2A/2B and PAX5 deletions, known to confer a very poor outcome, were identified in 10 cases (45.5%). Finally, RNA-sequencing and/or FISH experiments of the Ph-like ALL cases revealed 11 TK activating lesions (47.8%): five ABL-class fusion genes (three NUP214/ABL1, one ZC3HAV1/ABL2 and one EBF1/PDGFRB), two BCR/JAK2, three CRLF2-r and 1 DDX3X/USP9X, the latter known to be associated with CRLF2 deregulation.26

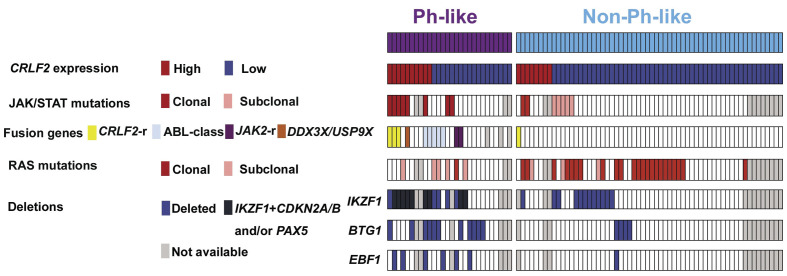

Figure 1.

Distribution of the genetic lesions in the Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) and non-Ph-like cases study. Only the samples evaluated for the BCR/ABL1-like predictor and mutational status are depicted.

Overall, Ph-like associated lesions were identified in 70.8% (17 of 24) of cases and are summarized in Table 2.

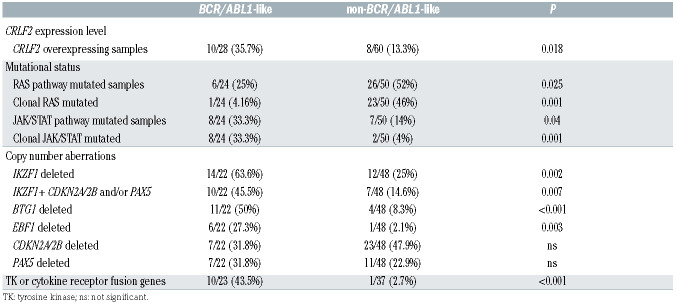

When the genetic landscape of Ph-like ALL was compared to that of the non-Ph-like cases, significant differences emerged. As shown in Table 3, CRLF2-high was significantly more frequent in Ph-like ALL (35.7% vs. 13.3%, P=0.018). Similarly, clonal JAK/STAT mutations were specific of the Ph-like subset (33.3% vs. 4%, P=0.001), while RAS pathway clonal mutations were more frequent in non-Ph-like than in Ph-like ALL cases (46% vs. 4.2%, P=0.001). Coincidence analysis (CNA) documented that IKZF1, EBF1 and BTG1 deletions were significantly more common of the Ph-like than in the non-Ph-like subset (63.6%, 50% and 27.3% vs. 25%, 7.8% and 2.1%, respectively; P=0.002, P<0.001 and P=0.007); CDKN2A/2B and PAX5 deletions were equally distributed among Ph-like and non-Ph-like cases (31.8% vs. 47.9% and 31.8% vs. 22.9%, respectively).

The analysis of fusion genes, performed on a total of 85 patients, showed that rearrangements involving TK or cytokine receptors were significantly higher in the Ph-like cases with ten fusion genes involving either CRLF2 or a TK compared to only one CRLF2-r case in the non- BCR/ABL1-like cases (43.5% vs. 1.6%, P<0.001).

The genetic lesions documented in both the Ph-like and non-Ph-like subgroups are detailed in the Online Supplementary Table S3 and their distribution is provided in Figure 1; further details on non-Ph-like ALL cases, as well as on NGS coverage, are provided in the Online Supplementary Results and Online Supplementary Table S5, respectively.

Response to treatment, minimal residual disease evaluation and transplant allocation

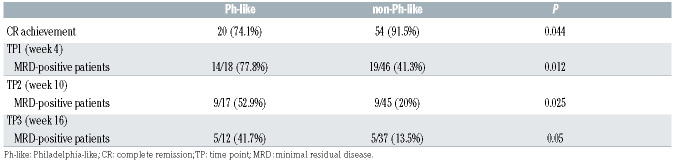

The Ph-like status was significantly associated with response to treatment: in fact, Ph-like patients had a significantly inferior CR rate at time point 1 (TP1) compared to non-Ph-like cases (74.1% vs. 91.5%, P=0.044, Table 4) and this translated into a lower probability of CR achievement (P=0.038, OR=0.265, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.071-0.921, Online Supplementary Table S6). The latter data retained statistical significance also in a multivariate model adjusted for clinically relevant parameters, as well as for genetic lesions with a prognostic relevance.

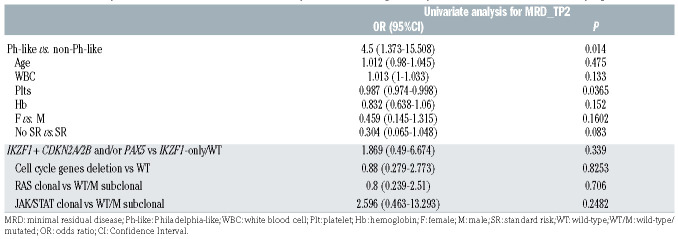

MRD evaluation - feasible in 64 patients at TP1, 62 at TP2 and 49 at TP3 - showed that at TP1, 77.8% of Ph-like cases and 41.3% of non-Ph-like were MRD-positive (P=0.012); at TP2, 52.9% of Ph-like cases and 20% of non-Ph-like were MRD-positive (P=0.025); similarly, at TP3, 41.7% of Ph-like cases and 13.5% of non-Ph-like cases were MRD-positive (P=0.05). These data, summarized in Table 4, indicate that in the Ph-like patients there is a significantly higher MRD persistence at all TP evaluated compared to non-Ph-like cases. Consistently, the univariate analyses for MRD results showed that - when considering both clinically relevant parameters and genetic prognostic markers - only the Ph-like status was a risk factor for being MRD-positive at TP2 (P=0.014, OR=4.5, 95% CI: 1.373-15.508) (Table 5).

As a consequence, HSCT rate in first CR was significantly higher (P=0.015) in Ph-like vs. non-Ph-like cases (eight of 20 vs. 6 of 54, 40% vs. 11%, respectively), in line with the guidelines of the trial, in which MRD persistence was a criterion for HSCT allocation. Importantly, among five MRD+ Ph-like patients who did not undergo a transplant, four relapsed at a median period a 7.8 months from CR, whereas no relapses occurred in the three MRD+ Ph-like patients undergoing HSCT.

Table 2A.

Genetic features of BCR/ABL1-like cases. BCR/ABL1-like BCR/ABL1 -like prediction, scoring, CRLF2 expression and mutational screening.

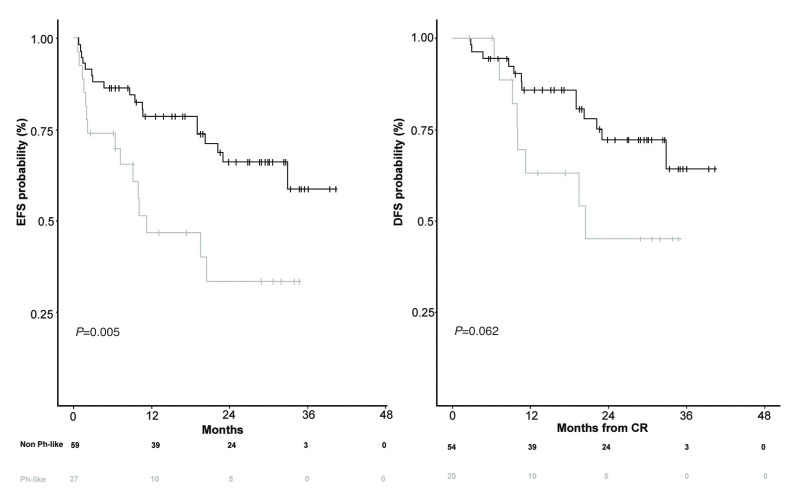

Survival analyses

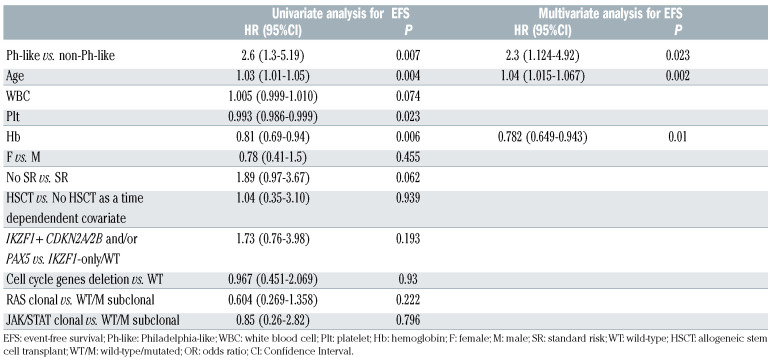

Survival analyses at 24 months showed that Ph-like ALL patients had a significantly inferior EFS than non-Ph-like patients (33.5% vs. 66.2%, P=0.005); this difference was also evident with regard to DFS (45.5% vs. 72.3%, P=0.062), though to a lesser extent, as illustrated in Figure 2; OS was also investigated, and although not significant, it was inferior in Ph-like ALL cases than in non-Ph-like patients (48.5% vs. 72.9%, P=0.16, Online Supplementary Figure S3). The lack of significance is most likely due to the fact that a higher number of Ph-like patients, because of persistent MRD positivity, underwent, as per protocol guidelines, HSCT (40% vs. 11% in Ph-like vs. non-Ph-like cases, respectively, P=0.015).

In a multivariate model for EFS, adjusting for relevant clinical parameters - including HSCT, evaluated as a time dependent covariate - and genetic prognostic markers, the Ph-like profile, age and Hb levels were the only risk factors that retained statistical significance (Table 6). Notably, however, Ph-like patients undergoing an allogeneic transplant showed a trend towards better EFS (P=0.078).

Discussion

The possibility of an early recognition of Ph-like ALL patients offers the unprecedented opportunity to refine the prognostic categories of Ph-negative ALL, and to better understand the reasons for the poor outcome. In the present study, we investigated a cohort of adult B-NEG ALL patients enrolled in the front-line GIMEMA LAL1913 protocol,20 based on a pediatric-inspired backbone and in which MRD quantification at week 10 is pivotal for transplant allocation, in order to assess the prognostic impact of the Ph-like status. In particular, we aimed at understanding the interplay between the Ph-like status and MRD response. Furthermore, we sought to analyze the clinical and genetic features, the hematologic responses to treatment and the outcome of the identified Ph-like ALL patients.

Table 2B.

Copy number aberration (CNA) analysis, and RNA-sequencing/FISH analyses.

The screening carried out using the BCR/ABL1-like predictor7 led to the identification of 28 Ph-like cases - representing 31.8% of the B-NEG cohort - with a slightly higher incidence in adults than in young adults. This finding is in agreement with the recently reported data in other adult cohorts and resembles the epidemiologic behavior of “true Ph-positive” ALL.5,6,19 The comparison of the clinicalbiological features of Ph-like and non-Ph-like cases revealed a substantial homogeneity in terms of WBC count and sex distribution, as in the GMALL and the MDACC clinical trials,6,19 and at variance from Roberts and colleagues5 who reported that adult BCR/ABL1-like patients have a higher WBC and are prevalently of male sex. In children, an association with hyperleukocyotsis has been described by Den Boer et al.1 and Reshmi et al.,27 the latter based on the COG AALL1131 high-risk cohort. The association with male sex was documented in the Total Therapy XV cohort.16 On the contrary, Roberts and colleagues28 did not find significant differences in the WBC count and sex in the standard-risk subset of childhood B-ALL patients enrolled in the COG AALL0331. In addition to the WBC count and sex, it is worth underlying that in our study the population of Ph-like patients was allocated to both the standard- (56%) and high-risk (44%) categories: this finding has important clinical implications since the prompt identification of these cases might lead to a better therapeutic stratification that ultimately would avoid undertreating these high-risk patients. In adults, a similar distribution was reported also by Herold et al.,6 while in the pediatric setting this issue is still controversial. Indeed, most Ph-like cases were associated to a high risk in both the COALL and DCOG cohorts,1 while in the Total Therapy XV trial16 Ph-like cases were equally distributed in the standard and high National Cancer Institute (NCI) risk groups. Of note, in the report on 139 children classified as standard-risk, Roberts and colleagues28 showed that the Ph-like status did not affect outcome, suggesting that in children risk stratification is clinically more significant than the genomic features.

From a genetic standpoint, the present study further corroborates the notion that CRLF2 overexpression, JAK/STAT mutations and deletions of IKZF1, BTG1 and EBF1 are significantly more frequent in Ph-like ALL cases. In addition, we observed that clonal JAK/STAT mutations were almost exclusively found in Ph-like ALL, while clonal RAS mutations were specific of non-Ph-like cases, thus suggesting that they play a different role in the two molecular subtypes. Moreover, when focusing on CRLF2 overexpression, it emerges that it is not sufficient to induce a Ph-like profile: indeed, of the eight Ph-like cases that were fully characterized, seven had at least another lesion. Furthermore, the results on the incidence of rearrangements targeting TK and cytokine receptors indicate that they prevail in the Ph-like subgroup, with ABL-class gene rearrangements outnumbering the other lesions. Thus, we could identify at least one underlying genetic lesion in 70.8% of Ph-like patients. Not for all cases was it possible to perform an extensive biological screening due to the lack of genomic material (four cases) and RNA-sequencing was carried out using targeted approaches and not genomewide tools. This may help to explain why no further genetic lesions could be found in the remaining cases (29.2%) that proved positive with the BCR/ABL1 predictor. The validity and reproducibility of the BCR-ABL1-like predictor has been externally validated by other institutions and from external samples in Europe, showing an overall concordance with other tools (FISH and NGS) of 88%.29

Table 3.

Comparison between Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) and non-Ph-like genetic features.

Table 4.

Complete remission achievement and minimal residual disease evaluation in Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) and non-Ph-like cases.

Table 5.

Univariate analyses for minimal residual disease at time point 2, considering clinically relevant variables and molecular prognostic markers.

Table 6.

Summary of univariate and multivariate analyses for event-free survival, considering clinically relevant variables and molecular prognostic markers.

Figure 2.

Survival curves of Philadelphia-like (Ph-like) and non-Ph-like patients. event-free survival and disease-free survival.

With regards to the relationship between the Ph-like status, MRD response and outcome, we showed that Ph-like ALL patients have a higher risk of CR failure: in fact, 74.1% of Ph-like ALL and 91.4% non-Ph-like achieved a CR. This difference was neither detected in the intensive GMALL trials 06/99 and 07/03 – in which all patients achieved a CR, albeit with a short duration -,6 nor in the hyper-CVAD-based protocols or the augmented BFM regimen administered at MDACC.19

More importantly, our study allowed to correlate the Ph-like status with MRD, that is presently regarded as the most important prognostic marker in ALL management. In fact, this analysis showed that in the GIMEMA LAL1913 protocol, at all TP analyzed, the percentage of MRD-positive patients was significantly higher in the Phlike ALL subset than in non-Ph-like cases. This difference was particularly evident at TP2 (HSCT decisional point), when 52.9% of Ph-like and only 20% of non-Ph-like cases were MRD-positive. Indeed, when both clinically relevant parameters and genetic prognostic markers were taken into account the Ph-like profile proved the only risk factor for MRD positivity at TP2. Thus, considering both response to induction treatment and MRD monitoring, the Ph-like status, if identified early, permits not only to recognize patients who are likely to be refractory to induction treatment, but also to identify - within cases who achieve a CR - those who are likely to remain MRD-positive. This strong association may allow to anticipate therapeutic changes.

To our knowledge, this is the first study that analyzes the interaction between the Ph-like status and MRD - assessed by quantitative PCR of the IG and TR gene rearrangements - in a broad cohort of uniformly and prospectively treated adult ALL patients within a clinical trial. Similar results were provided by Herold and colleagues6 who found that Ph-like patients were less likely to achieve a MRD-negative status in a small cohort of 31 patients with overlapping MRD and Ph-like status information. In the pediatric setting, contradicting results have been reported.14,16

Furthermore, the comparison of survival curves highlighted that Ph-like patients experienced a significantly worse EFS at 24 months compared to that of non-Ph-like cases (33.5% and 66.2%, respectively). Along the same line, also in cases achieving a CR, the Ph-like profile had a negative prognostic impact, as shown by the worse DFS of Ph-like patients. Although limited by the small sample size, our study demonstrates that transplant is beneficial in these cases and should be pursued at the earliest opportunity, as shown by the high rate of relapses within nontransplanted Ph-like patients (4 of 5 MRD positive patients relapsed).

Lastly, in all outcome parameters evaluated - CR achievement, MRD at TP2 and EFS - the Ph-like status emerged as an independent prognostic marker.

In addition to confirming the inferior outcome of Ph-like ALL patients, these data indicate that the differences between Ph-like and non-Ph-like cases are not abolished by pediatric-like intensive therapeutic schemes, in agreement with the results of the MDACC group.18 Based on the MRD findings hereby reported, this is primarily contributed to the significantly lower rates of complete molecular responses observed in Ph-like patients.

In light of the poor outcome of Ph-like ALL and of the possibility of using targeted approaches,30 different clinical trials specifically designed for Ph+ ALL and Ph-like ALL cases are testing the efficacy of dasatinib (clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 02420717, 02883049, 03564470 and 02143414) or of dasatinib in combination with blinatumomab (clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: SWOG-S1318 and NCT02143414). Other studies are investigating the impact of blinatumomab in combination with chemotherapy in Ph-negative B-lineage ALL (GIMEMA LAL2317, clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 03367299 and 02003222). In these latter studies, it is investigated if the addition of blinatumomab can increase the rates of CR and MRD-negativity in Ph-like patients, as already observed in Ph+ ALL.32 In support of the fact that Ph-like patients may benefit from targeted treatment, a recent study from Tanasi and colleagues has reported that the introduction of TKI front-line was associated with a 3-years OS of 77%.31 Other compounds, such as ruxolitinib (clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 02420717, 03571321 and 02723994) and the histone deacetylase inhibitor chidamide (clinicaltrials gov. Identifier: 03564470) are under investigation.

Taken together, the results of this study carried out on adult B-NEG ALL cases enrolled in the front-line GIMEMA LAL1913 clinical protocol confirm that the BCR/ABL1-like predictor7 is a valid tool to rapidly recognize Ph-like cases that account for about 30% of adult B-NEG ALL. In addition, we could show that also in a pediatric-oriented and MRD-driven clinical trial Ph-like patients have a lower probability of achieving a CR, are more likely to remain MRD-positive and have a significantly shorter EFS. The Ph-like profile is an independent risk factor for CR failure and MRD-persistence, thus further underlying the need that Ph-like cases - a primary unmet clinical need in ALL - are rapidly recognized at diagnosis in order to refine the risk stratification of Phnegative ALL and optimize patients’ management. Further investigations are currently ongoing to unravel if within Ph-like ALL there are subgroups of patients with a different outcome likelihood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Grazia Fazio and Chiara Palmi for support in TruSight Pancancer and MLPA experiments, Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) 5x1000, Special Program Metastases (21198), Milan (Italy) to RF; Finanziamento Medi Progetti Universitari 2015 to SC (Sapienza University of Rome); Bandi di Ateneo per la Ricerca (Sapienza University of Rome, RM11816436B712AF) to SC and PRIN 2017 (2017PPS2X4_002) to SC, CM, and RLS; Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Perugia (grant number 2018.0418.021) to RLS.

References

- 1.Den Boer ML, van Slegtenhorst M, De Menezes RX, et al. A subtype of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia with poor treatment outcome: a genome-wide classification study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):125-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(5):470-480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roberts KG, Morin RD, Zhang J, et al. Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute kymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(2):153-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts KG, Li Y, Payne-Turner D, et al. Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(11):1005-1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, et al. High frequency and poor outcome of Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(4):394-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herold T, Schneider S, Metzeler KH, et al. Adults with philadelphia chromosome–like acute lymphoblastic leukemia frequently have igh-CRLF2 and JAK2 mutations, persistence of minimal residual disease and poor prognosis. Haematologica. 2017; 102(1):130-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiaretti S, Messina M, Grammatico S, et al. Rapid identification of BCR/ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukaemia patients using a predictive statistical model based on quantitative real time-polymerase chain reaction: clinical, prognostic and therapeutic implications. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(5):642-652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maude SL, Tasian SK, Vincent T, et al. Targeting JAK1/2 and mTOR in murine xenograft models of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2012; 120(17):3510-3518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lengline E, Beldjord K, Dombret H, et al. Successful tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy in a refractory B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with EBF1-PDGFRB fusion. Haematologica. 2013;98(11):146-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weston BW, Hayden MA, Roberts KG, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy induces remission in a patient with refractory EBF1- PDGFRB-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):e413-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazio F, Barberi W, Cazzaniga G, et al. Efficacy of imatinib and chemotherapy in a pediatric patient with Philadelphia-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia with EBF1- PDGFRB fusion transcript. Leuk Lymphoma. 2020;61(2):469-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tasian SK, Teachey DT, Li Y, et al. Potent efficacy of combined PI3K/mTOR and JAK or ABL inhibition in murine xenograft models of Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2017;129(2):177-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RC, Kang H, Roberts KG, et al. Development and validation of a highly sensitive and specific gene expression classifier to prospectively screen and identify B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) patients with a Philadelphia chromosomelike (“Ph-like” or “BCR-ABL1-Like”) signature for therapeutic targeting and clinical intervention. Blood. 2013;122(21):826. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heatley SL, Sadras T, Kok CH, et al. High prevalence of relapse in children with Philadelphia-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia despite risk-adapted treatment. Haematologica. 2017;102(12):e490-e493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts KG. The biology of Philadelphia chromosome-like ALL. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2017;30(3):212-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roberts KG, Pei D, Campana D, et al. Outcomes of children with BCR-ABL1-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with risk-directed therapy based on the levels of minimal residual disease. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3012-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stock W, Luger SM, Advani AS, et al. A pediatric regimen for older adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of CALGB 10403. Blood. 2019;133(14):1548-1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tasian SK, Hurtz C, Wertheim GB, et al. High incidence of Philadelphia chromosome- like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in older adults with B-ALL. Leukemia. 2017; 31(4):981-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain N, Roberts KG, Jabbour E, et al. Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a high-risk subtype in adults. Blood. 2017;129(5):572-581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassan R, Chiaretti S, Paoloni F, et al. First results of the GIMEMA LAL1913 protocol for adult patients with Philadelphia-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph- ALL). On behalf of the GIMEMA Acute Leukemia Working Group. PS919. HemaSphere. 2018;2(S1):408. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messina M, Chiaretti S, Wang J, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic role of targetable lesions in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia without recurrent fusion genes. Oncotarget. 2016;7(12):13886-13901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Messina M, Chiaretti S, Fedullo AL, et al. Clinical significance of recurrent copy number aberrations in B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia without recurrent fusion genes across age cohorts. Br J Haematol. 2017;178(4):583-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fedullo AL, Messina M, Elia L, et al. Prognostic implications of additional genomic lesions in adult Ph+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2019; 104(2):312-318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap). A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chiaretti S, Brugnoletti F, Messina M, et al. CRLF2 overexpression identifies an unfavourable subgroup of adult B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia lacking recurrent genetic abnormalities. Leuk Res. 2016;41:36-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell LJ, Jones L, Enshaei A, et al. Characterisation of the genomic landscape of CRLF2-rearranged acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2017;56(5):363-372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reshmi SC, Harvey RC, Roberts KG, et al. Targetable kinase gene fusions in high-risk B-ALL: A study from the Children’s Oncology Group. Blood. 2017;129(25):3352-3361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts KG, Reshmi SC, Harvey RC, et al. Genomic and outcome analyses of Ph-like ALL in NCI standard-risk patients: a report from the children’s oncology group. Blood. 2018;132(8):815-824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiaretti S, Taherinasab A, Canichella M, et al. The Validation of the BCR/ABL1-like predictor across laboratories shows reproducibility of results. Blood. 2019: 134 (Suppl 1):S5211. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chiaretti S, Messina M, Foà R. BCR/ABL1- like acute lymphoblastic leukemia: how to diagnose and treat? Cancer. 2019;125(2): 194-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanasi I, Ba I, Sirvent N, et al. Efficacy of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia harboring ABLclass rearrangements. Blood. 2019;134(16): 1351-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Foà R, Bassan R, Vitale A, et al. GIMEMA Investigators. Dasatinib-nlinatumomab for Ph-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(17):1613-1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.