ABSTRACT

Background: Experiencing a potentially traumatic event can put individuals at risk for both short-term and long-term mental health problems. While many psychological interventions exist for those who have experienced potentially traumatic events, there remains controversy about the best ways to support them.

Objective: This review explores the effect of brief psychoeducational interventions after potentially traumatic experiences on adult recipients’ mental health, attitudes towards mental health, and trauma-related knowledge, as well as the perceived acceptability of psychoeducation.

Methods: Four electronic databases were searched for relevant published literature.

Results: Ten papers were included in the review. There was no evidence that psychoeducation was any more effective in terms of reducing mental health symptoms than other interventions or no intervention at all. There was some evidence that psychoeducation improved attitudes towards and knowledge of mental health immediately post-intervention; one study examined whether these improvements were sustained over the long term and found that they were not. However, psychoeducation was generally highly regarded by participants.

Conclusions: This review did not find sufficient evidence to support routine use of brief psychoeducation as a stand-alone intervention.

KEYWORDS: Brief interventions, potentially traumatic events, psychoeducation, single-session interventions, trauma

HIGHLIGHTS

Brief single-session psychoeducation interventions delivered within a month of experiencing a potentially traumatic event do not appear to have a significant impact on mental health.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: Experimentar un evento potencialmente traumático puede poner a las personas en riesgo de tener problemas de salud mental tanto a corto como a largo plazo. Si bien existen muchas intervenciones psicológicas para aquellos que han experimentado eventos potencialmente traumáticos, persiste la controversia sobre las mejores formas de apoyarlos.

Objetico: Esta revisión explora el efecto de las intervenciones psicoeducativas breves después de experiencias potencialmente traumáticas en la salud mental de adultos destinatarios de la intervención, las actitudes hacia la salud mental y el conocimiento relacionado con el trauma, así como la aceptabilidad percibida de la psicoeducación.

Método: Se buscó por literatura relevante publicada en cuatro bases de datos electrónicas.

Resultados: Se incluyeron diez artículos en la revisión. No hubo evidencia que la psicoeducación fuera más efectiva en cuanto a reducir los síntomas de salud mental que otras intervenciones o ninguna intervención en absoluto. Hubo alguna evidencia que la psicoeducación mejoró las actitudes y el conocimiento hacia la salud mental inmediatamente después de la intervención; un estudio examinó si estas mejorías se mantenían a largo plazo y encontraron que no se mantenían. Sin embargo, la psicoeducación fue en general muy apreciada por los participantes.

Conclusiones: Esta revisión no encontró evidencia suficiente como para apoyar el uso rutinario de psicoeducación breve como una intervención independiente.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Intervenciones breves, Eventos potencialmente traumáticos, Psicoeducación, Intervenciones de sesión única, Trauma

Short abstract

背景:经历潜在创伤事件可能会使个人面临短期和长期心理健康问题的风险。尽管有很多针对那些潜在创伤事件经历者的心理干预措施, 对于支持他们的最佳方式仍存在争议。

目的:本综述探讨了潜在创伤经历之后的简短心理教育干预对成年受试者心理健康的效果, 对心理健康的态度, 对创伤相关知识的认识, 以及对心理教育的感知可接受性。

方法:在四个电子数据库中检索相关的公开文献。

结果:本综述共纳入10篇论文。没有证据表明, 在减少心理健康症状方面, 心理教育比其他干预措施或者根本没有干预措施更为有效。有证据表明, 干预后立即进行心理教育可以改善人们对心理健康的态度和知识; 一项研究考查了这些改善是否可以长期持续, 发现并非如此。但是, 参与者普遍高度重视心理教育。

结论:本综述没有发现足够的证据支持常规使用简短心理教育作为独立干预措施。

关键词: 简短干预, 潜在创伤事件, 心理教育, 单次干预, 创伤

1. Introduction

Experiences which put an individual (or someone close to them) at risk of serious injury, death or sexual violence are referred to as ‘potentially traumatic events’ (PTEs) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Many people will experience at least one PTE within their lifetime (Ogle, Rubin, Berntsen, & Siegler, 2013); the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (Fear, Bridges, Hatch, Hawkins, & Wessely, 2014) suggests that about a third of adults in the UK have experienced at least one. Experiencing a PTE can be distressing in the short term and, while the majority of people will not go on to develop mental health problems (Bonanno, 2004), a minority may develop longer-term mental health consequences including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety (Neria, Nandi, & Galea, 2008). Prevention, early detection, and treatment of psychological difficulties following a PTE are important in minimizing the mental health consequences of such events (Brooks & Greenberg, in press).

Numerous psychological interventions intended to improve post-traumatic symptoms exist, but controversy remains about the best ways to support people exposed to PTEs. Single session psychological debriefing – a professional intervention within days of PTE, encouraging affected individuals to recollect and talk about their reactions (Mitchell, 1983) was commonly used in the past but there is now strong evidence it is ineffective and even harmful (Wessely, Rose, & Bisson, 2000).

So, the search continues for a simple, brief, easily administered intervention that can be delivered early, which promotes resilience and coping, as well as identifying those who may require additional help (Gibson et al., 2007; Whitworth, 2016). One commonly used example of such an intervention is psychoeducation. This involves the provision of information allowing participants to learn about ‘normal’ psychological responses to PTEs and enhancing understanding of stress reactions, for the purpose of reducing the potential negative impacts of trauma. It usually also includes information on seeking further help (Whitworth, 2016). Psychoeducation can be delivered in multiple ways, including face-to-face sessions either individually or as a group, or provision of educational booklets, websites, or smartphone apps. Howard and Goelitz (2004) suggest it may also encourage help-seeking by reducing the stigma surrounding mental health. The provision of psychoeducation to improve mental health after trauma is based on the assumptions that people will find post-traumatic symptoms to be less disturbing if they have already been given information about them; that they will be reassured by the knowledge that such symptoms are normal; that understanding the nature of symptoms will encourage help-seeking in cases where symptoms are extreme or long-lasting; that psychoeducation could help people adapt by introducing corrective information that modifies their perception of themselves or the event; and that the self-help guidance provided in psychoeducation will be empowering (Wessely et al., 2008).

One difficulty is the issue of what ‘psychoeducation’ actually means. Southwick, Friedman, and Krystal (2008) point out that psychoeducation is framed differently across the literature, sometimes meaning distribution of self-help materials and sometimes including debriefing. We pointed out that psychoeducation is often deemed to be ‘so obviously a good thing’ (Wessely et al., 2008) so that providing evidence of its effectiveness is rarely seen as a priority and argued that further research is needed to ascertain whether psychoeducation is helpful. Furthermore, we suggested that psychoeducation might cause harm by heightening anxiety or providing too much information and triggering an effect similar to the nocebo effect, in which participants expect to experience adverse effects and consequently do so.

This review collates the scientific literature on brief post-event psychoeducation interventions to address the research question: what is known about the effectiveness and acceptability of brief psychoeducation in reducing the risk of mental health problems following a PTE?

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources

Four electronic databases (Embase, MEDLINE, PsycInfo and Web of Science) were searched by one author (SKB) using a combination of psychoeducation-related terms and traumarelated terms (full list of search terms is presented in Appendix I). All citations weredownloaded to EndNote.

2.2. Study selection

To be included, studies had to:

be published in peer-reviewed journals in the English language;

contain primary data;

include only participants aged 16+;

include participants exposed to single traumatic incidents (e.g. disasters, road traffic accidents, injury, assault);

evaluate a brief psychoeducational intervention (e.g. single-session in-person intervention, or provision of educational leaflets, websites or smartphone apps), delivered within 4-week post-PTE;

include measures of either psychological outcomes, attitude outcomes, knowledge outcomes, or participant feedback on the intervention (or some combination of these).

Exclusion criteria included studies on refugees (as they may have a very different trauma experience and it is not clear how psychoeducation might impact on refugee concerns) and torture victims (the added political dimension means there is often ongoing high stress unrelated to trauma, which psychoeducation would likely not impact on). Papers were excluded if the psychoeducation intervention involved more than one in-person session; this is because we did not want psychoeducation as a ‘treatment’ included because many forms of psychotherapy have a psychoeducation component; we were interested in how people might be helped in the immediate aftermath of a traumatic incident where single session interventions are commonly offered. Interventions could be included if they involved aspects other than psychoeducation (e.g. relaxation exercises) but only if psychoeducation made up at least 50% of the intervention. We included studies testing psychoeducation only, studies comparing psychoeducation to other interventions and studies comparing psychoeducation to treatment-as-usual/control groups.

Titles of all studies were screened for relevance by one author (SKB); following this, abstracts were screened and any clearly not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded. The full texts of all remaining citations were downloaded and assessed against the inclusion criteria. Finally, reference lists of all papers meeting the inclusion criteria were hand-searched. At all stages of the screening process, any queries or uncertainties about whether papers should be included were discussed with other members of the research team.

2.3. Data extraction

Data extraction forms were used to systematically extract the following information from each study: country of study; number of participants; demographic characteristics of participants; the traumatic event participants had experienced; details of the psychoeducation intervention and any comparison groups; outcome measures used; and key results.

2.4. Data synthesis

Narrative synthesis was used to analyse the results of all included papers and group their results into themes.

2.5. Quality appraisal

The quality of the included papers was assessed using a structured tool (presented in Appendix B) developed by the authors for a previous review (Brooks et al., 2015), informed by existing quality appraisal tools (Drummond & Jefferson, 1996; EPHPP, 2009; National Institute for Health, 2014). Quality was measured across three domains: study design; data collection and methodology; and analysis and interpretation of results.

3. Results

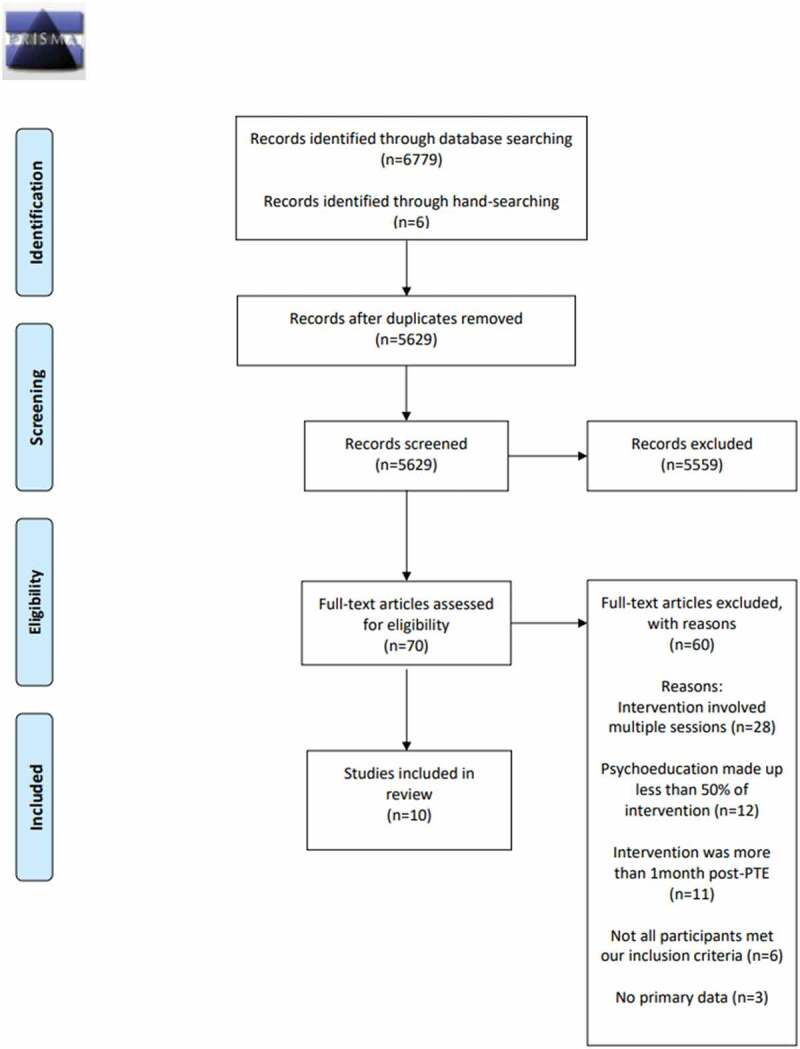

Six thousand seven hundred and seventy-nine citations were found, and 1156 duplicates removed. Five thousand forty were removed based on title and a further 519 based on abstract. The 64 remaining full texts were screened and additional six papers found via hand-searching their references. Of these 70 citations, 60 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. A PRISMA diagram illustrating the screening process can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram

Studies were published between 1999 and 2015. The majority of them were from the UK (n = 6); others were from the Netherlands (n = 2), Sri Lanka (n = 1) and the USA (n = 1). Psychoeducation was most often provided in the form of a written booklet (n = 6); other studies provided psychoeducation via online materials (n = 2), face-to-face (n = 1) or videos (n = 1). Participants included parents of children admitted to intensive care (n = 1), accident or injury survivors (n = 7), snakebite victims (n = 1), and victims of violent crime (n = 1). Table 1 summarizes the included studies.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Authors (year) | Country | Intervention | Participants | Outcome measures | Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Als, Nadel, Cooper, Vickers, and Garralda (2015) | UK | Psychoeducational handbook provided within 7 days of discharge from hospital, outlining possible psychological reactions in children and parents; emotional and behavioural recovery, and getting back to normal; plus a telephone call within 14 days of receiving the handbook, addressing the family’s post-discharge experience, reinforcing the psychoeducational material and encouraging parents to put the advice into practice Comparison group: Treatment as usual (TAU) |

Parents of children aged 4–16 admitted to paediatric intensive care unit Intervention: n = 22; mean age 43; 24% male TAU: n = 9; mean age 36; 17% male |

Impact of Events Scale; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Parental Stressor Scale: Paediatric Intensive Care Unit Measures completed at baseline and 3–6 months follow-up Comments on feasibility and acceptability of intervention – unclear at what point these were collected |

All parents said they had read the handbook. At follow-up, parents who received the intervention reported lower post-traumatic stress and depressive symptoms (small effect sizes) but there was little difference in anxiety scores (effect size <0.2). All evaluated the handbook as useful; most (82%) deemed it appropriately timed. Additional comments collated from parents in the intervention group indicated that the handbook made them feel more prepared for life after PICU (82%) and less anxious or concerned (77%). Almost half (47%) had shared it with others. |

| Bugg, Turpin, Mason, and Scholes (2008) | UK | Information booklet on symptoms of traumatic stress and advice on recovery strategies, provided one month post-injury Comparison group: information booklet plus a one-hour appointment where they received instructions for writing plus three writing exercises on consecutive days, where they were asked to write about their emotions, thoughts and feelings relating to their injury |

Traumatic injury patients at risk of developing PTSD (i.e. scored 50+ on the Acute Stress Disorder Scale within a month after injury) Psychoeducation: n = 36; mean age 38.14; 55.6% female; 19.4% had experienced assault, 75% a road traffic accident and 5.6% an occupational injury Writing: n = 31; mean age 36.65; 90.3% female; 16.1% had experienced assault and 83.9% a road traffic accident |

Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; World Health Organization Quality of Life Measure, brief version Measures completed before reading the booklet and then at 3 months and 6 months post-injury Usefulness of booklet and whether they had put any of the strategies into practice, measured at 3-month post-intervention |

Both groups rated booklet as useful: 72.2% of bookley-only group rated the section on psychological sequelae as moderately, very or extremely useful, compared to 67.8% of writing group. 74.9% of booklet-only group rated the coping strategies section as useful compared to 67.8% in writing group. There were significant improvements on measures of anxiety, depression and PTSD over time. Differences between groups on these measures were not statistically significant. |

| Ehlers et al. (2003) | UK | Approximately 4 weeks after the accident, participants received a 64-page self-help booklet called Understanding Your Reactions To Trauma, based on principles of CBT, with an additional 4-page booklet focusing on common avoidance behaviours and safety-seeking behaviours; clinicians met patients for 40 minutes to explain the booklet and motivate them to follow its advice Comparison groups: 1) 12 weekly sessions of cognitive therapy; 2) group who received repeated assessments only (regular monitoring but no treatment) |

Motor vehicle accident survivors with PTSD Psychoeducation: n = 28; cognitive therapy: n = 28; repeated assessments: n = 29 Age not reported; gender not reported |

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) and Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) to measure PTSD; Beck Anxiety Inventory; Beck Depression Inventory; Sheehan Disability Scale If participants had a PDS score below 14, CAPS global severity rating below 2, and Beck Depression/Anxiety Inventory scores below 12 they were defined as having ‘high end-state functioning’. Study-specific scale to measure treatment credibility Assessed post-treatment and 6 months later |

Both groups rated the booklet as highly logical, were moderately confident it would be helpful, and were confident about recommending it to a friend. The cognitive therapy group showed significantly better outcomes at posttreatment and follow-up. Repeated assessments and booklet-only groups did not significantly differ at either time point. On 2 measures, high end-state functioning at follow-up and request for treatment, the outcome for the self-help group was worse than for the repeated assessments group. |

| Mouthaan et al. (2011) | Netherlands | Trauma TIPS: a 30-minute online intervention based on CBT techniques of psychoeducation, stress management/relaxation techniques, and in vivo exposure. It consists of 6 steps, including introduction to the programme and basic operating instructions; assessments of acute anxiety and arousal; video features of the trauma centre’s surgical head explaining the procedures at the centre and the purpose of the programme, and of 3 patients sharing their experiences after their injury; a short textual summary of 5 coping tips for common physical and psychological reactions after trauma; audio clips with instructions for stress management techniques; contact information for programme assistance or professional help for enduring symptoms; and a forum for peer support | 5 trauma patients v 5 healthy controls Trauma patients: mean age 34.4; 4 males and 1 female; 4 had experienced road traffic accidents and 1 had experienced a workplace accident Controls: mean age 34.6; 4 males and 1 female |

State Trait Anxiety Inventory; Impact of Event Scale-Revised Study-specific scale assessing feasibility of and satisfaction with the intervention, within 24 hours of intervention Measures completed immediately prior to the intervention, immediately following the intervention, 24 hours after intervention, and one month post-trauma |

Participants rated the intervention as useful and clear. Although all mean scores of the patients decreased with time, no significant differences were found between any of the mean scores on posttraumatic stress symptoms. |

| Mouthaan et al. (2013) | Netherlands | Trauma TIPS: see above for description (provided one week post-injury) Comparison group: TAU |

Injury patients suffering possible severe injuries who had experienced a potentially traumatic event Intervention: n = 151; mean age 44.18; 58.9% male TAU: n = 149; mean age 43.49; 61.1% male |

Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale; Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; Impact of Event Scale-Revised; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Assessments were 1, 3, and 12 months post-injury |

PTSD symptoms decreased over time with no significant difference between the intervention group and control group. Moreover, there were no differences between groups with respect to the number of PTSD and depression diagnoses and with respect to the severity of depression and anxiety at 12 months. |

| Rose, Brewin, Andrews, and Kirk (1999) | UK | Educational leaflet about normal post-traumatic reactions and where/when to find help Comparison groups: 1) one-hour debriefing where participants gave a detailed account of their trauma encompassing facts, cognitions and feelings, plus educational leaflet; 2) assessment only |

Victims of a violent crime within the past month (n = 157 at baseline, n = 138 at 6-month follow-up, n = 92 at 11-month follow-up) Psychoeducation: n = 52; mean age 34.9; 39 males and 13 females Debriefing: n = 54; mean age 35.4; 37 males and 17 females Assessment only: n = 51; mean age 37.3 |

Post-traumatic Symptom Scale; Impact of Event Scale; Beck Depression Inventory Measures taken at baseline, 6-month follow-up and 11-month follow-up |

All groups improved over time, but there were no between-group differences. |

| Scholes, Turpin, and Mason (2007) | UK | Self-help booklet providing information about the psychological sequelae of trauma and structured proactive advice based on cognitive behavioural strategies Comparison group: control group (no booklet) |

Patients attending an accident and emergency department; those who scored 50+ on the Acute Stress Disorder Scale were randomized to either intervention or high-risk control group while those scoring below this were assigned to a low-risk control group for comparison Intervention: n = 116 (baseline), n = 60 (post-intervention), n = 49 (follow-up); mean age 37.62; 56.9% female; 64.66% experienced road traffic accident, 25% assault, 10.33% occupational injury High-risk control: n = 111 (baseline), n = 65 (post-intervention), n = 50 (follow-up); mean age 35.61; 45.95% female; 65.76% experienced road traffic accident, 29.73% assault, 4.5% occupational injury Low-risk control: n = 120 (baseline), n = 75 (post-intervention), n = 67 (follow-up); mean age 38.55; 32.5% female; 55.83% experienced road traffic accident, 11.67% assault, 32.5% occupational injury |

Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; World Health Organization Quality of Life Measure, brief version Assessments completed at baseline (within 1-month post-injury) and 3- and 6-months post-injury 3 months post-intervention, participants asked to rate usefulness of intervention |

PTSD, anxiety and depression decreased across time but there were no group differences in these measures or quality of life. However, subjective ratings of the usefulness of the self-help booklet were very high. Participants from the intervention group were asked to rate sections of the booklet on a scale of 1 (not useful) to 5 (extremely useful). Out of 60 completers, 52 rated the section on psychological sequelae, resulting in a mean rating of 3.60 (SD = 0.87), with 94.23% rating it 3 or above and 51.92% rating it ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ useful. Fifty participants rated the section on coping strategies, resulting in a mean rating of 3.70 (SD = 0.89); 94% rated it 3 or above, with 60% rating it ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ useful. |

| Turpin, Downs, and Mason (2005) | UK | 8-page self-help booklet called ‘Responses to traumatic injury’ which explains and normalizes common physiological, psychological and behavioural reactions to traumatic injury; provides advice on non-avoidance and emotional support; gives information on seeking further help Comparison group: no booklet |

Patients attending an accident and emergency department with injuries sustained by road traffic accidents, occupational injury or assault Intervention: n = 75 (baseline), n = 54 (follow-up); mean age 39.74; 45% female; 16% experienced assault, 40% experienced occupational injury, 44% experienced a road traffic accident Control: n = 67 (baseline), n = 46 (follow-up); mean age 37.42; 54% female; 24% experienced assault, 42% experienced occupational injuries, 34% experienced a road traffic accident |

Post-Traumatic Diagnostic Scale; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Assessments at 2, 10–12 and 24–26 weeks At 24–26 weeks, participants in intervention group rated its usefulness and completed some open questions about their experiences |

PTSD), anxiety and depression decreased with time but there were no group differences in PTSD or anxiety. The controls were less depressed at follow-up. There was a reduction in PTSD caseness within the control (50%) compared with the intervention (20%) group which was almost significant. Overall, 66% deemed the booklet useful. When asked what was particularly helpful, 16 people (47%) referred to information and advice and 11 people (32%) the normalization of reactions. |

| Wijesinghe et al. (2015) | Sri Lanka | 15-minute psychoeducation involving discussion about the patient’s opinion on the causes and consequences of the snake bite, and important thoughts to elicit, such as myths, negative assumptions, and future plans and expectations of the patient Comparison groups: 1) one group who received no intervention; 2) one group who received psychoeducation plus a 20-minute cognitive behavioural intervention one month later Interventions took place on discharge from hospital |

Snakebite victims with systemic envenoming Psychoeducation: n = 65; mean age 41.3; 76% male No intervention: n = 68; mean age 42.5; 73.3% male Psychoeducation + cognitive behavioural intervention: n = 69; mean age 40.2; 74.7% male |

Hopkins Symptom Checklist; modified version of the Beck Depression Inventory; Sheehan Disability Inventory; Post-traumatic Stress Symptom Scale-Self Report Measures taken 6 months post-discharge from hospital |

At follow-up, there was a decreasing trend in the proportion of patients who were positive for psychiatric symptoms of depression and anxiety from controls (26.5%) through psychoeducation group (13.8%) to cognitive intervention group (8.7%). This decreasing trend was statistically significant (Chi square test for trend = 7.901, p = 0.005). However, there was no difference in the proportion of patients diagnosed with depression between the three groups and the intervention also had no effect on post-traumatic stress disorder. Depression was diagnosed in 21/68 (30.9%) controls, 17/65 (26.2%) psychoeducation participants and 18/69 (26.1%) patients who received the cognitive intervention. These rates did not show a statistically significant trend (chi square for trend = 0.391, p = 0.532). However, on further analysis, the rate of severe depression was significantly higher in controls. The proportion of patients with PTSD was 7/68 (10.3%) in controls, compared to 8/65 (12.3%) psychoeducation patients and 2/69 (2.9%) cognitive intervention patients which was not statistically significant (Chi-square for trend = 2.448; p = 0.118) |

| Wong, Marshall, and Miles (2013) | USA | 18-minute psychoeducational video on post-traumatic distress and factors related to the mental health treatment seeking process, based on the model of self-regulation Comparison group: 10-minute wound care video on medical treatment for lacerations, the healing process, and home care |

Trauma care centre patients receiving care following hospitalization for a serious physical injury Psychoeducation: n = 52 (baseline), n = 42 (follow-up); mean age 28.8; 17.3% female Wound care group: n = 47 (baseline), n = 37 (follow-up); mean age 33.7; 14.9% female |

PTSD Checklist; Knowledge of PTSD Test; Beliefs about Psychotherapy Scale; and Beliefs about Psychotropic Medication Scale completed immediately after viewing video and at one-month follow-up; at follow-up, participants also asked about mental health service use and self-recognition of PTSD symptoms | Immediately after viewing the video, participants exhibited greater knowledge of PTSD symptoms and more positive beliefs about mental health treatment than those in the wound care condition. At 1-month follow-up, however, these differences were no longer maintained. No significant differences in PTSD were found between the intervention and control groups. Differences in self-recognition of PTSD nearly reached significance with psychoeducation participants being more likely to recognize symptoms as mental health problems. |

3.1. Mental health outcomes

None of the studies comparing psychoeducation to other interventions found psychoeducation to be superior in terms of mental health outcomes. In a study comparing 52 psychoeducation participants to 51 controls and 54 who received debriefing, Rose et al. (1999) found that all groups improved over eleven months in terms of mental health symptoms, but there were no between-group differences. Ehlers et al. (2003) found that the participants receiving cognitive therapy (n = 28) showed significantly better mental health outcomes than the psychoeducation participants (n = 28) at post-treatment and six-month follow-up. Bugg et al. (2008) found significant improvements overall on measures of anxiety, depression and PTSD over 6 months, but no differences were found between a group who received psychoeducation (n = 36) and a group who received psychoeducation plus writing exercises (n = 31); additionally, no significant improvements in quality of life were found for either group. Wijesinghe et al. (2015) found that, after 6 months, 13.8% of 65 participants who received psychoeducation showed psychiatric symptoms of anxiety and depression: this was more than the 8.7% of 69 participants who received psychoeducation plus a cognitive behavioural intervention, but less than the 26.5% of 68 controls. The rate of severe depression was significantly higher in controls than in both other groups. Prevalence of PTSD was highest (12.3%) in psychoeducation participants, compared to 2.9% in the group who received psychoeducation plus cognitive behavioural treatment, and 10.3% in controls; the difference between the psychoeducation and control groups was not statistically significant.

One study found significant differences between psychoeducation and control groups, but only for some measures: in Als et al.’s (2015) study, participants who received psychoeducation (n = 22) reported lower post-traumatic stress symptoms and depressive symptoms at 3–6 month follow-up than participants who did not (n = 9), but there was little difference in anxiety scores.

Several other studies found improvements in symptoms across both control and intervention groups, with no significant differences between groups (Ehlers et al., 2003; Mouthaan et al., 2013, 2011; Rose et al., 1999; Scholes et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2013).

In two studies, psychoeducation yielded poorer results than no intervention: Turpin et al. (2005) found that PTSD, anxiety and depression decreased (p < 0.05) with time but there were no group differences in PTSD or anxiety and the controls were in fact less depressed (p < 0.05) at 24–26 week follow-up. There was a reduction in PTSD caseness within the control (50% of 67) compared with the intervention (20% of 75) group which was almost significant (p < 0.06). Ehlers et al. (2003) found that psychoeducation participants fared worse than the control group in terms of requesting treatment and ‘high end-state functioning’.

3.2. Attitudes towards mental health and treatment

Wong et al. (2013) found that immediately post-intervention, participants who had psychoeducation (N = 52) exhibited more positive beliefs about mental health treatment than controls (n = 47); however, these differences were no longer maintained at the one-month follow-up, and no significant differences in treatment use were found between psychoeducation participants and controls.

3.3. Knowledge

Wong et al. (2013) found that, immediately after viewing the psychoeducational video, participants exhibited greater knowledge of PTSD symptoms than controls. Controlling for PTSD symptoms, participants in the psychoeducation condition were also more likely to endorse self-recognition of PTSD problems immediately post-intervention than controls (p = 0.05). At the 1-month follow-up, group differences in PTSD knowledge were no longer maintained, but differences in self-recognition of PTSD between groups narrowly failed to reach significance, with psychoeducation intervention participants being more likely to recognize their symptoms as mental health problems than controls.

3.4. Acceptability of psychoeducation

Psychoeducation interventions were generally viewed positively, with more than half of participants reporting that they found them useful (Als et al., 2015; Bugg et al., 2008; Mouthaan et al., 2011; Scholes et al., 2007; Turpin et al., 2005). In Turpin et al.’s (2005) study, when asked what was particularly helpful, 16 people (47%) referred to information and advice and 11 people (32%) referred to the normalization of reactions. Positive views appeared to be sustained over time; three studies collected feedback at follow-up and found that participants viewed the intervention positively even after 3 months (Bugg et al., 2008; Scholes et al., 2007) and 6 months (Turpin et al., 2005).

In Als et al.’s (2015) study, all participants evaluated psychoeducational materials as useful and 82% indicated that the information in the handbook made them feel more prepared for life after the paediatric intensive care unit. Mouthaan et al. (2011) found that participants reviewed the psychoeducation programme as useful and clear, with most finding the stress management exercises relaxing and the videos informative.

In a study comparing the perceived usefulness of psychoeducation with cognitive therapy, few differences were found. Ehlers et al. (2003) found that there was no difference in treatment credibility between the groups; both rated their respective interventions as highly logical, were moderately confident they would be helpful, and were confident about recommending the intervention to a friend.

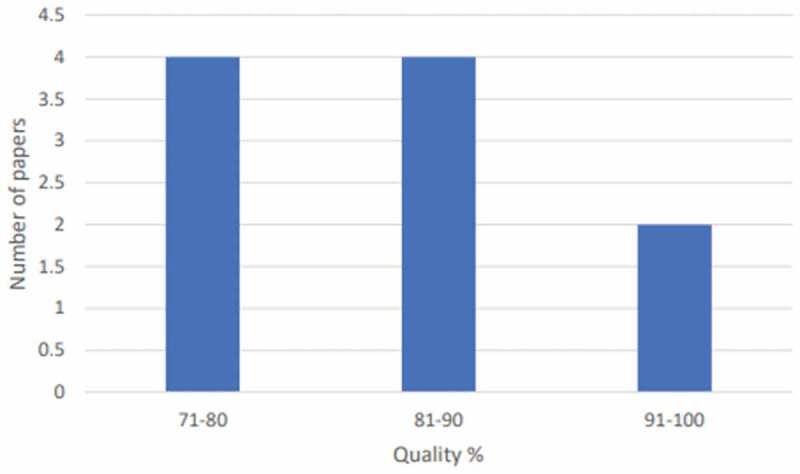

3.5. Study quality

The total percentage of ‘yes’ answers to the quality appraisal questions was calculated for each study (see Figure 2). Quality of papers was high overall with no studies scoring under 70%.

Figure 2.

Scores for overall quality

Most studies scored highly for design, with seven papers scoring 100% on this section; those that did not tended to be let down by not recruiting participants during the same time period or failing to specify inclusion criteria. Methodology scores were more mixed, with only two papers gaining full marks; other studies tended to report response rates of less than 50% or not explain reasons for loss to follow-up. Six papers scored 100% for their analysis and interpretation of results; those that did not typically failed to report confidence intervals or adjust for potential confounding variables, or did not report their data with appropriate caveats.

4. Discussion

This study questioned whether brief post-incident psychoeducation might impact on recipients’ mental health. Overall, we did not find evidence of its effectiveness. Our results do not overall suggest negative effects of psychoeducation with only one of 10 papers reviewed (Turpin et al., 2005) finding that a psychoeducation group fared less well than the control group. However, whilst there was some evidence that psychoeducation recipients reported some increase in knowledge immediately post-intervention and generally liked the information provided, we could find no conclusive evidence that psychoeducation led to a sustained improvement in mental health outcomes after traumatic events. Fortunately, most people exposed to trauma do recover naturally, without the need for any formal intervention (Bonanno, 2004). Psychoeducation appears to add little or nothing to this, although the tendency for participants to endorse psychoeducation suggests that they may attribute symptom improvement to the intervention.

We found some evidence that psychoeducation improved attitudes towards mental health and may increase the likelihood of seeking help for mental health problems; however, these changes did not persist over time (Wong et al., 2013), a not unusual finding (Hanbury et al., 2013) and our results suggest that it is important to ensure that evaluation trials collect their outcome measures after a suitable follow-up period. There was also some evidence that psychoeducation increased knowledge of trauma and PTSD symptoms, but this appeared to be a temporary outcome suggesting a decay of knowledge.

Participants’ opinions of psychoeducation were generally positive with most perceiving it to be useful. Psychoeducation certainly has face validity with the public – for example in a study of students (Tarrier, Liversidge, & Gregg, 2006), psychoeducation was highly endorsed (the fourth highest-rated intervention for PTSD, out of 14). This is also shared by professionals – a study of European Union professionals on the suitability of Dutch guidelines for disaster response (Brake & Dückers, 2013) found that 77% (of 116 participants) were in favour of psychoeducation. However, despite being viewed positively by participants, we found insufficient evidence to conclude that psychoeducation as a stand-alone intervention is effective in preventing or reducing mental health symptoms. Indeed, the recent NICE guidelines for the management of PTSD (NICE, 2018) notes that the evidence base for psychoeducation is ‘very limited and uncertain’ and insufficient to recommend psychoeducation for use on its own. We also note that previous high-quality studies of psychological debriefing concluded that in spite of those who were debriefed reporting high levels of satisfaction with the debriefing process, they nonetheless did not improve and indeed some experienced a deterioration in their mental health (Rose, Bisson, Churchill, & Wessely, 2002). Thus, satisfaction with an intervention is not a useful metric to measure effectiveness.

4.1. Limitations

We found relatively few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of brief psychoeducation interventions after traumatic events. From over 6000 papers found by our initial database searches, only a small number evaluated brief psychoeducation as a stand-alone intervention rather than as part of a more comprehensive, longer-term intervention. While interventions including psychoeducation as just one component may be effective, it is difficult to ascertain how much of their success is due to the psychoeducation aspect. Additionally, it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which psychoeducation is responsible for any improvements in mental health symptoms, attitudes or knowledges because researchers cannot control for other information participants might seek out or knowledge they may already have been exposed to (Robertson, Humphreys, & Ray, 2004; Whitworth, 2016).

Different terminologies used across the literature means that some relevant papers may have been missed. Additionally, given that psychoeducation is frequently used as the control group in evaluations of more comprehensive interventions, it is highly likely that there exist many studies which evaluate psychoeducation but do not include it as a keyword as it is not the focus of the study.

The differences in methodologies, participants and outcomes across papers make comparisons difficult. The types of trauma experienced by participants differed greatly, and some studies provided psychoeducation as a preventive measure whereas others delivered it to participants already diagnosed with PTSD.

Not all studies compared psychoeducation to a control group who received nothing. This means their usefulness in this particular review is limited as it is impossible to ascertain the extent to which symptoms improved due to psychoeducation and the extent to which symptoms merely improved naturally over time.

One limitation within the literature itself is that in any of the studies involving participants having to read a psychoeducational leaflet or booklet, it is not possible to know that every participant did in fact read the material. One study (Als et al., 2015) did ask all participants to confirm that they had read the material; however, most others did not address this. As such, we do not know for certain that the psychoeducation interventions were really administered as intended. Additionally, although we included only studies which provided psychoeducation as an intervention following a single traumatic incident, it is possible that some participants may have also experienced other traumatic incidents which may have affected their symptoms. Whilst we would hope that, if this were the case, studies would consider this as a confounding variable, it is possible that some participants may have experienced more than one single trauma.

4.2. Conclusion

We found no evidence that brief psychoeducation led to a sustained improvement in mental health status after exposure to traumatic events, despite some recipients subjectively regarding psychoeducation as being useful. Although there was some evidence that psychoeducation had a positive effect on attitudes towards, and knowledge of, mental health, such improvements were independent of any change in mental health status. This review concludes that brief psychoeducation, delivered as a stand-alone intervention after traumatic events, is not beneficial to mental health.

Appendix A. Search terms.

Search 1: psychoeducat*; psycho-educat*; educat* adj3 booklet*; educat* adj3 leaflet*; crisis management (combined with OR)

Search 2: Anthrax; avalanche*; avian influenza; bioterroris*; bio-terroris*; bird flu; blizzard*; bomb*; CBRN; chemical spill*; Chernobyl; cyclone*; drought*; disaster*; earthquake*; Ebola; emergenc*; explosion*; fire*; flood*; Fukushima; H1N1; H5N1; hurricane*; industrial accident*; landslide*; massacre*; mass killing*; MERs; Middle East respiratory syndrome; pandemic*; nuclear radiation; radiological; SARs; severe acute respiratory syndrome; September 11th; shooting*; storm*; swine flu; terroris*; Three Mile Island; tidal wave*; tornado*; trauma*; tsunami*; typhoon*; volcanic eruption*; volcano; World Trade Center (combined with OR)

Search 3: 1 AND 2

Appendix B. Quality appraisal tool.

All questions are answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Section 1: Study design

Was the research question/objective clearly stated?

Were all subjects selected or recruited from the same or similar populations (including the same time period)?

Were the inclusion and exclusion criteria for being in the study pre-specified and applied uniformly to all participants?

Was the study population and size clearly specified and defined?

Section 2: Data collection and methodology

Were standardized measures used, or where measures are designed for the study, attempts to ensure reliability and validity were made?

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

Was the participation rate stated and at least 50%?

Was the number of participants described at each stage of the study?

If the study followed participants up, were reasons for loss to follow-up explained?

Section 3: Analysis and interpretation of results

Were details of statistical tests and confidence intervals sufficiently rigorous and described?

Were potential confounding variables measured and adjusted statistically for their impact on the relationship between exposure(s) and outcome(s)?

Was the answer to the study question provided?

Are the findings related back to previous research?

Do conclusions follow from the data reported?

Are conclusions accompanied by the appropriate caveats?

Funding Statement

The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response at King’s College London in partnership with Public Health England (PHE), in collaboration with the University of East Anglia. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or Public Health England. DW is also a member of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit for Behavioural Science and Evaluation at the University of Bristol.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Als, L. C., Nadel, S., Cooper, M., Vickers, B., & Garralda, M. E. (2015). A supported psychoeducational intervention to improve family mental health following discharge from paediatric intensive care: Feasibility and pilot randomized controlled trial. BMJ Open, 5(12), 12. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA, USA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–13. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brake, H. T., & Dückers, M. (2013). Early psychosocial interventions after disasters, terrorism and other shocking events: Is there a gap between norms and practice in Europe? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 19093. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.19093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K., Dunn, R., Sage, C. A. M., Amlot, R., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2015). Risk and resilience factors affecting the psychological wellbeing of individuals deployed in humanitarian relief roles after a disaster. Journal of Mental Health, 24(6), 385–413. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1057334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K., & Greenberg, N. (in press). Preventing and treating trauma-related mental health problems. In L. Peter (Ed.), The textbook of acute trauma care. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bugg, A., Turpin, G., Mason, S., & Scholes, C. (2008). A randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of writing as a self-help intervention for traumatic injury patients at risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(1), 6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, M., & Jefferson, T. (1996). Guidelines for authors and peer reviewers of economic submissions to the BMJ. The BMJ Economic Evaluation Working Party. British Medical Journal, 313(7052), 275–283. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7052.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) . (2009). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Available online: http://www.ephpp.ca/tools.html [accessed 24 November 2020]

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Herbert, C., & Mayou, R. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(10), 1024–1032. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.10.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fear, N. T., Bridges, S., Hatch, S., Hawkins, V., & Wessely, S. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/0/8/adult_psychiatric_study_ch4_web.pdf

- Gibson, L. E., Ruzek, J. I., Naturale, A. J., Watson, P. J., Bryant, R. A., Rynearson, T., … Hamblen, J. L. (2007). Interventions for individuals after mass violence and disaster: Recommendations from the roundtable on screening and assessment, outreach, and intervention for mental health and substance abuse needs following disasters and mass violence. Journal of Trauma Practice, 5(4), 1–28. doi: 10.1300/J189v05n04_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanbury, A., Farley, K., Thompson, C., Wilson, P. M., Chambers, D., & Holmes, H. (2013). Immediate versus sustained effects: Interrupted time series analysis of a tailored intervention. Implementation Science, 8(1), 130. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, J. M., & Goelitz, A. (2004). Psychoeducation as a response to community disaster. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4(1), 1–10. doi: 10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, J. T. (1983). When disaster strikes … the critical incident debriefing process. Journal of the Emergency Medical Services, 8, 36–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouthaan, J., Sijbrandij, M., De Vries, G. J., Reitsma, J. B., Van De Schoot, R., Goslings, J. C., … Olff, M. (2013). Internet-based early intervention to prevent posttraumatic stress disorder in injury patients: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(8), e165. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouthaan, J., Sijbrandij, M., Reitsma, J. B., Luitse, J. S. K., Goslings, J. C., & Olff, M. (2011). Trauma tips: An internet-based intervention to prevent Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in injured trauma patients. Journal of Cyber Therapy and Rehabilitation, 4(3), 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health . (2014). Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovas-cular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort

- Neria, Y., Nandi, A., & Galea, S. (2008). Post-traumatic stress disorder following disasters: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 38(suppl 4), 467–480. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE . (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/chapter/Recommendations#management-of-ptsd-in-children-young-people-and-adults

- Ogle, C. M., Rubin, D. C., Berntsen, D., & Siegler, I. C. (2013). The frequency and impact of exposure to potentially traumatic events over the life course. Clinical Psychological Science, 1(4), 426–434. doi: 10.1177/2167702613485076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, M. F., Humphreys, L., & Ray, R. (2004). Psychological treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder: Recommendations for the clinician based on a review of the literature. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 10(2), 106–118. doi: 10.1097/00131746-200403000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, S., Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Kirk, M. (1999). A randomized controlled trial of individual psychological debriefing for victims of violent crime. Psychological Medicine, 29(4), 793–799. doi: 10.1017/S0033291799008624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose, S. C., Bisson, J., Churchill, R., & Wessely, S. (2002). Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD000560. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholes, C., Turpin, G., & Mason, S. (2007). A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of providing self-help information to people with symptoms of acute stress disorder following a traumatic injury. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(11), 2527–2536. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick, S., Friedman, M., & Krystal, J. (2008). Does psychoeducation help prevent post traumatic psychological stress disorder? In reply. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 71(4), 303–307. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.4.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier, N., Liversidge, T., & Gregg, L. (2006). The acceptability and preference for the psychological treatment of PTSD. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(11), 1643–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turpin, G., Downs, M., & Mason, S. (2005). Effectiveness of providing self-help information following acute traumatic injury: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 187(1), 76–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.1.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely, S., Bryant, R. A., Greenberg, N., Earnshaw, M., Sharpley, J., & Hughes, J. H. (2008). Does psychoeducation help prevent post traumatic psychological distress? Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 71(4), 287–302. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2008.71.4.287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessely, S., Rose, S., & Bisson, J. (2000). Brief psychological interventions (“debriefing”) for trauma-related symptoms and the prevention of post traumatic stress disorder. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth, J. D. (2016). The role of psychoeducation in trauma recovery: Recommendations for content and delivery. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 13(5), 442–451. doi: 10.1080/23761407.2016.1166852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesinghe, C. A., Williams, S. S., Kasturiratne, A., Dolawaththa, N., Wimalaratne, P., Wijewickrema, B., & Jayamanne, S. F. (2015). A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for delayed psychological effects in snakebite victims. PloS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 9(8), e0003989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, E. C., Marshall, G. N., & Miles, J. N. (2013). Randomized controlled trial of a psychoeducational video intervention for traumatic injury survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress Disorders & Treatment, 2(2). doi: 10.4172/2324-8947.1000104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]