Abstract

Background In this study we sought to evaluate the contribution of dynamic four-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) relative to the standard imaging work-up for the identification of the dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI) in patients with suspected chronic scapholunate instability (SLI).

Methods Forty patients (22 men, 18 women; mean age 46.5 ± 13.1 years) with suspected SLI were evaluated prospectively with radiographs, arthrography, and 4DCT. Based on radiographs and CT arthrography, three groups were defined: positive SLI ( n = 16), negative SLI ( n = 19), and questionable SLI ( n = 5). Two independent readers used 4DCT to evaluate the lunocapitate angle (LCA) (mean, max, coefficient of variation [CV], and range values) during radioulnar deviation.

Results The interobserver variability of the 4DCT variables was deemed excellent (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.79 to 0.96). Between the three groups, there was no identifiable difference for the LCA mean . The LCA max values were lower in the positive SLI group (88 degrees) than the negative SLI group (102 degrees). The positive SLI group had significantly lower LCA cv (7% vs. 12%, p = 0.02) and LCA range (18 vs. 27 degrees, p = 0.01) values than the negative SLI group. The difference in all the LCA parameters between the positive SLI group and the questionable SLI group was not statistically significant. When comparing the negative SLI and questionable SLI groups, the LCA cv ( p = 0.03) and LCA range ( p = 0.02) values were also significantly different. The best differentiation between patients with and without SLI was obtained with a LCA cv and LCA range threshold values of 9% (specificity of 63% and sensitivity of 62%) and 20 degrees (specificity of 71% and sensitivity of 63%), respectively.

Conclusion In this study, 4DCT appeared as a quantitative and reproducible relevant tool for the evaluation of DISI deformity in cases of SLI, including for patients presenting with questionable initial radiography findings.

Level of evidence This is a Level III study.

Keywords: carpal instability, dorsal intercalated segment instability, four-dimensional computed tomography, kinematics, scapholunate ligament

Scapholunate instability (SLI) may be challenging to diagnose. 1 2 It is the most frequent cause of wrist osteoarthritis, defined as scapholunate advanced collapse or SLAC wrist. 3 In static stage, the diagnosis is obvious when a careful radiographic analysis is performed. However, in the predynamic and dynamic SLI stages, the diagnosis is harder to make solely based on static imaging methods (radiographs, computed tomography [CT] arthrogram), which means exploratory arthroscopy may be required prior to surgical treatment. SLI is visible on lateral radiograph or sagittal CT scan as lunate instability in extension or dorsal intercalated segment instability (DISI), along with dorsal displacement of the scaphoid. 4 5 6 7 8 9 With the wrist in a neutral position, DISI typically demonstrates dorsal tilt of the lunate with an increase of scapholunate (SLA) and lunocapitate (LCA) angles. 10 DISI deformity is an important diagnostic factor and its assessment is difficult on static view. Bone superimposition and patient positioning issues can influence the relative projection of the lunate with the scaphoid and capitate on radiographs. 6 Dynamic imaging can provide information about carpal anatomy and alignment by analyzing the carpus and its joint spaces during various wrist movements. 11 Abou Arab et al 12 and Rauch et al 13 described the use of dynamic four-dimensional CT (4DCT) to analyze the carpus during radioulnar deviation (RUD). 4DCT allowed a dynamic and quantitative analysis of the LCA with a correlation to scapholunate ligament (SLL) status on CT arthrogram. 13 4DCT could improve SLI imaging assessment by providing a more accurate evaluation of the DISI deformity in static SLI cases and by improving the identification of predynamic and dynamic SLI. We hypothesize quantitative evaluation of lunate displacement with the 4DCT can provide means to distinguish wrists with and without chronic SLI. In this study, we sought to evaluate the contribution of 4DCT relative to the standard imaging work-up for the identification of the DISI.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

This was a prospective study approved by our institutional review board. This study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry (no. NCT02401568). Between January 2015 and December 2018, we included 40 consecutive patients older than 18 years who presented with chronic, posttraumatic wrist pain (more than 6-week history) (spontaneous and/or induced by palpation) over the scapholunate joint. They were referred by the same surgical team for complete imaging work-up because of suspected SLI. Patients with major joint stiffness, history of wrist surgery, fracture fixation, or arthroplasty implants in the wrist or congenital wrist deformity were excluded. All patients provided a written informed consent. An independent examiner (hand surgeon with 9 years of clinical experience) reviewed all the medical records to confirm the patients met the inclusion criteria. Each patient underwent an imaging evaluation consisting of radiographs and CT arthrogram of the painful wrist.

Radiographic Evaluation

All patients underwent standard anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs along with dynamic AP views with a clenched fist. The images were analyzed on an OsiriX workstation (Pixmeo 2016, Geneva, Switzerland). Measurements were performed by two readers independently (R1–hand surgeon with 5 years of clinical experience and R2–radiologist with 5 years of experience with musculoskeletal imaging). Static and dynamic scapholunate gaps (SLGs) (in mm), SLA, and LCA (in degrees) were calculated (0.1 mm accuracy for gaps and 1 degree for angles). SLGs greater than 3 mm, SLAs greater than 70 degrees, and capitolunate angles greater than 15 degrees were considered pathological. 10

4DCT Acquisition and Postprocessing of Images

Images were acquired with a 320-detector row CT scanner (Aquilion ONE, Canon Medical Systems, Otawara, Japan). We used acquisition parameters as described by Gondim Teixeira et al. 14 All acquisitions were performed using continuous volumetric mode (no table feed), 8 to 10 cm field-of-view, 512 × 512 matrix, and 0.5 mm slice thickness. Tube rotation time and intervolume interval were 0.5 second. Tube output was 100 kVp and 50 mAs. Images were reconstructed with bone kernel. The z -axis coverage was 8 cm.

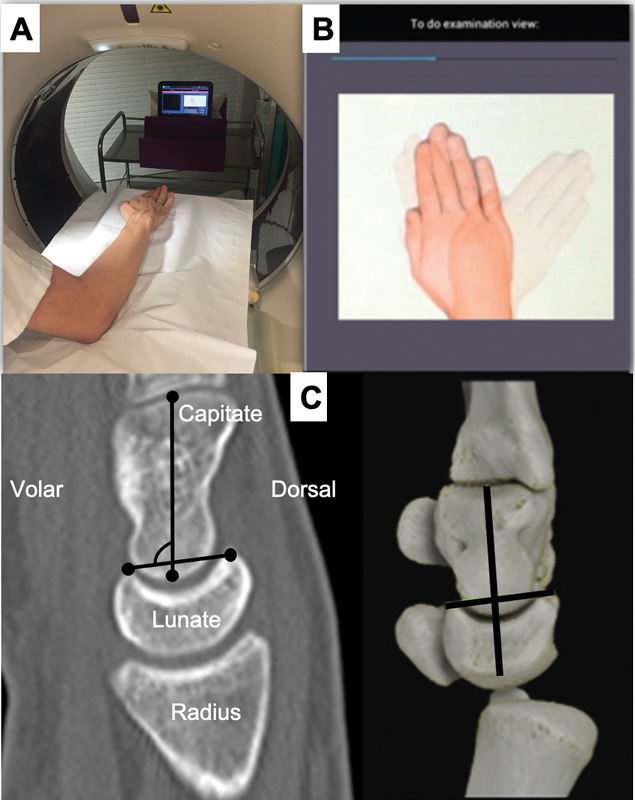

Before the acquisition, the patients were instructed on how to perform the RUD manoeuver. Patients were asked to move their wrist in a continuous and homogenous manner, from maximum radial deviation to maximum ulnar deviation, and then to return to the starting point (RUD cycle). Several RUD cycles (each ∼8 seconds long) were performed. Once patient motion was adequate, one RUD cycle was imaged. The examination lasted approximately 5 minutes (positioning + acquisition). The patient's position in the CT scanner is shown in Fig. 1 . RUD amplitude was measured in all patients on coronal slices. A line passing through the long axis of the radius and another through the third metacarpal were drawn in the volumes acquired in maximum radial deviation and maximum ulnar deviation. The sum of these two angles was considered as the RUD amplitude. The 4DCT images were analyzed on a postprocessing workstation (Vitrea, version 7.0; Canon Medical Systems) using the 4D Ortho application. Two independent readers (R1 and R2), blinded to clinical and CT arthrogram findings performed all measurements. Once all the 4DCT volumes were loaded, multiplanar and three-dimensional images were displayed. On a multiplanar image of one of the acquisition volumes, the readers manually selected the distal radius by placing a point in its medullary canal. The software then, registered this bone in all acquisition volumes making it a static referential, which served as the basis for the manual selection of the measurement reference planes. The LCA was measured by manually placing four markers on a sagittal plane located closest to the center of the lunate fossa of the radius ( Fig. 1 ). Then, the software automatically tracked the selected markers on all the remaining volumes allowing the calculation of the LCA in degrees on each acquired volume. Four variables were calculated based these data: mean (LCA mean ), maximum (LCA max ), coefficient of variation (LCA cv , standard deviation/mean in %), and range (LCA range , maximum – minimum LCA value). The estimated measurement accuracy was 1 degree.

Fig. 1.

Photographs of the acquisition protocol for four-dimensional computed tomography (4DCT) images: ( A ) Participant is standing beside the CT scanner table, with their wrist in neutral, placed on the table on foam cushions while wearing the lead apron and thyroid protector. ( B ) Screen capture from a tablet showing the amplitude and displacement speed during radioulnar deviation (right side). ( C ) Reference planes and marker position used for performing the lunocapitate angle (LCA) measurements in the CT multiplanar images. For construction of LCA, two markers were placed in volar and dorsal horns of lunate bone and two other markers were positioned over capitate bone long axis, in sagittal plane located closest to the center of the lunate fossa of the radius.

CT Arthrogram

All patients underwent a CT arthrogram less than 1 hour after the 4DCT using the same CT scanner. The contrast agent was injected into the joint in strict aseptic conditions under fluoroscopy control by a musculoskeletal radiologist with opacification of the midcarpal and radiocarpal compartments. Nondiluted iodixanol was used as a contrast agent. The three portions of the SLL (dorsal, volar, proximal) were analyzed by an independent examiner (radiologist, 12 years' experience in musculoskeletal imaging). Based on the ligament's appearance, the patients were split into two groups: no tear or isolated tear of proximal portion only (normal SLL) and partial or full tear of dorsal and/or volar portions (ruptured SLL). The SLL ruptures were further split into two groups: partial tears (PT) (partial or total loss of continuity in the dorsal or volar segment) and full tear (FT) (total loss of continuity in the dorsal and volar segments).

Group Definition

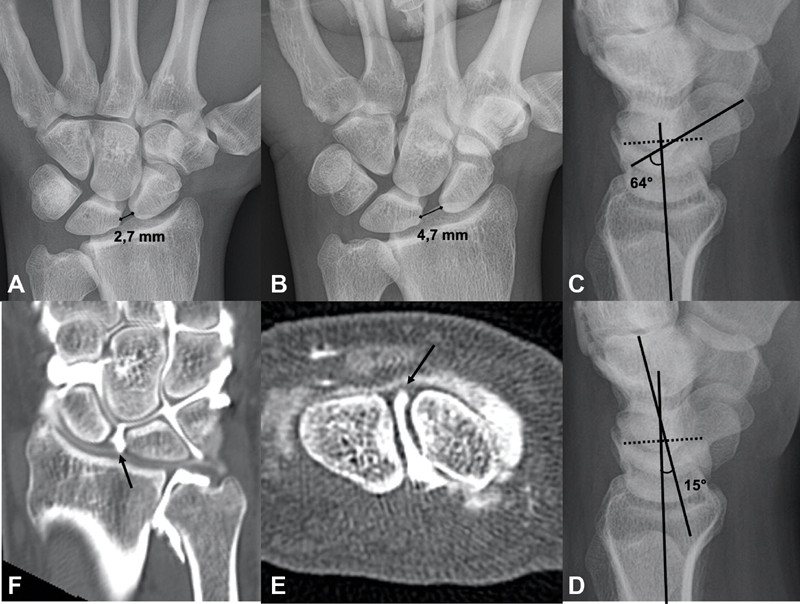

Using the radiographic and CT arthrogram data, three groups were defined. The positive SLI groups consisted of patients who had at least one pathological radiographic variable and a ruptured SLL on the CT arthrogram ( Fig. 2 ). The negative SLI group consisted of patients who had normal radiographs and CT arthrogram. The questionable SLI groups consisted of patients who had either at least one pathological radiographic variable or a ruptured SLL on the CT arthrogram.

Fig. 2.

Example of chronic scapholunate instability in a 33-year-old man with a history of chronic right wrist pain for many years. ( A ) Standard anteroposterior (AP) radiograph showing scapholunate gap (SLG) static, which was measured at 2.7 mm. ( B ) Dynamic AP view in clenched fist showing SLG dynamic, which was measured at 4.7 mm. ( C , D ) Standard lateral radiographs showing scapholunate angle and capitolunate angle, which was measured at 64 and 15 degrees, respectively. ( E ) Frontal computed tomography (CT) arthrogram slice showing tear of scapholunate ligament (arrow). ( F ) Axial CT arthrogram slice showing full tear of scapholunate ligament (arrow).

Statistical Analysis

Quantitative variables were described by their mean ± standard deviation, or by their median and interquartile range. Qualitative variables were described by their counts and percentages. Interobserver variability was measured with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). Quantitative radiological and 4DCT data were compared between subgroups using the Wilcoxon test with Holm–Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. This comparison was performed for the two readers (R1 and R2). The between-group characteristics were compared using the Fisher's test or the chi-square test depending on the nature of the data.

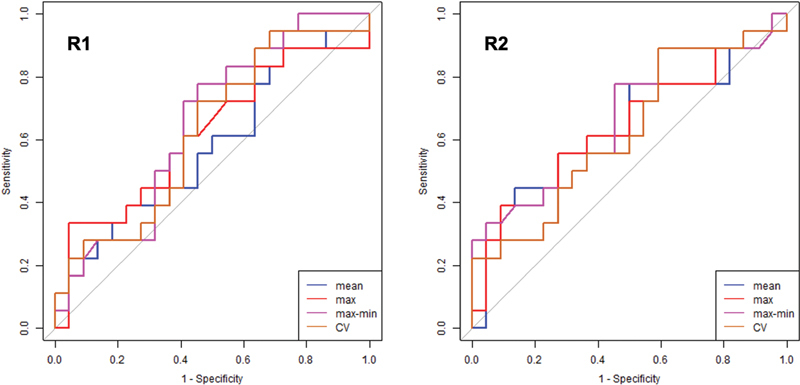

The sensitivity, specificity, cutoff value, and area under the curve (AUC) value for each parameter calculated from 4DCT (mean, maximum, CV, and range), were determined using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. The ROC analysis was performed to predict positive or negative SLI. The significant threshold was set at 5% (two-tailed tests).

Results

The mean age of the 40 patients was 47 ± 13 years. There were 18 women and 22 men. Sixteen patients were in the positive SLI group, 5 in the questionable SLI group, and 19 in the negative SLI group. The interobserver variability for each radiographic and 4DCT variable was excellent (ICC: 0.79 to 0.96). Table 1 summarizes the data for each group.

Table 1. Radiography and CT arthrogram findings in each group.

| Parameters | Group positive SLI ( n = 16) | Group negative SLI ( n = 19) | Group questionable SLI ( n = 5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) | 54 ± 11 | 39 ± 12 | 53 ± 6 | |

| Sex (% women / men) | 6% W; 94% M | 68% W; 32% M | 60% W; 40% M | |

| Radiographs, median (IQR) | SLG static (mm) | 2.7 (2.2–2.9) | 1.4 (1.3–1.9) | 1.5 (1–1.7) |

| SLG dynamic (mm) | 3.6 (2.8–4.7) | 2 (1.8–2.6) | 2.2 (1.7–2.7) | |

| SLA (degrees) | 82 (68–85) | 56 (49–63) | 64 (50–64) | |

| LCA (degrees) | 12 (9–23) | 10 (4–12) | 12 (9–15) | |

| CT arthrogram ( n ) | 3 FT; 13 PT | 19 N | 0 FT; 4 PT; 1 N | |

Abbreviations: CLA, capitolunate angle; CT, computed tomography; FT, full tear; IQR, interquartile range; LCA, lunocapitate angle; N, normal; PT, partial tear; SD, standard deviation; SLA, scapholunate angle; SLG, scapholunate gap; SLI, scapholunate instability.

Radiographic Evaluation

For the two readers, all the radiographic variables, except the LCA, were significantly higher in the positive SLI group than the negative SLI group ( p < 0.01). When comparing the positive SLI and questionable SLI groups, the SLG static ( p = 0.02) and SLG dynamic ( p = 0.03) were found to be significantly higher in the positive SLI group. There was no significant difference in any of the parameters ( p > 0.05) between the negative SLI and questionable SLI groups, although the SLA and LCA values were generally higher in the questionable SLI group.

CT Arthrogram Evaluation

In the positive SLI group ( n = 16), a FT of the SLL was found in 3 wrists and a PT in 13 wrists. In the questionable SLI group ( n = 5), a PT was found in 4 wrists and the other wrist had a normal SLL on CT arthrogram. There were no FTs in this group.

4DCT Evaluation

The RUD movement amplitude was similar between subgroups: 27 ± 19 degrees for positive SLI, 30 ± 21 degrees for negative SLI, and 29 ± 20 degrees for questionable SLI.

Between the three groups, there was no significant ( p > 0.05) difference for the LCA mean and LCA max . However, the LCA max values were lower in the positive SLI group than the negative SLI group. There was a trend toward lower values in the positive SLI group compared with the negative SLI group of 14% for the LCA max .

The positive SLI group had significantly lower LCA cv ( p = 0.02) and LCA range ( p = 0.01) values than the negative SLI group. For both readers, the values were 41% lower for the LCA cv and 40% lower for the LCA range .

The difference in all the LCA parameters between the positive SLI group and the questionable SLI group was not statistically significant ( p > 0.05).

When comparing the negative SLI and questionable SLI groups, the LCA cv ( p = 0.03) and LCA range ( p = 0.02) values were also significantly different ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. The LCA measured on 4DCT and their respective statistical significance in comparisons.

| Measurements of LCA | Group positive SLI a ( n = 16) | Group negative SLI b ( n = 19) | Group 3: questionable SLI c ( n = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (degrees) | 76 (66–88) | 83 (78–93) | 81 (77–88) |

| NS | NS | NS | |

| Max (degrees) | 88 (77–106) | 102 (89–108) | 97 (85–100) |

| NS | NS | NS | |

| CV (%) | 7 (5–12) | 12 (6–16) | 8 (6–10) |

| p = 0.02 | p = 0.03 | NS | |

| Range (degrees) | 18 (11–23) | 27 (15–41) | 18 (15–24) |

| p = 0.01 | p = 0.02 | NS |

Abbreviations: 4DCT, four-dimensional computed tomography; CV, coefficient of variation; LCA, lunocapitate angle; NS, no significant difference; SLI, scapholunate instability.

Note: The data shown are median (interquartile range).

p -Values in this column are results compared with group negative SLI.

p -Values in this column are results compared with group questionable SLI.

p -Values in this column are results compared with group positive SLI.

Diagnostic Performance for Chronic SLI

Given the similar sample size in the positive SLI ( n = 16) and negative SLI ( n = 19) subgroups, and the small size of the questionable SLI ( n = 5) subgroup, only the positive and negative subgroups were included in the ROC analysis. Thus, for the two readers ( Fig. 3 ), the best overall performance for differentiation between patients with and without SLI was reached with the LCA cv and LCA range parameters. LCA cv yielded a specificity and sensitivity of 63 and 62% by using a threshold of 9%, whereas LCA range yielded a specificity and sensitivity of 71 and 63% with a threshold of 20 degrees for both readers. For LCAc v and LCA range , the respective AUC were 0.62 and 0.67 ( Table 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the lunocapitate angle parameters during four-dimensional computed tomography for the diagnosis of scapholunate instability for the two readers (R1 and R2).

Table 3. Threshold values used for LCA cv and LCA range of 4DCT with their sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and AUC in differentiation between the patients with positive and negative SLI .

| LCA | Threshold | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | 9% | 62 | 63 | 60 | 65 | 0.62 |

| Range | 20 degrees | 63 | 71 | 67 | 65 | 0.67 |

Abbreviations: 4DCT, four-dimensional computed tomography; AUC, area under curve; CV, coefficient of variation; LCA, lunocapitate angle; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; SLI, scapholunate instability.

Discussion

The current study is consistent with that of Rauch et al 13 and confirm the benefits of using 4DCT with RUD movements during the imaging work-up of patients with suspected chronic SLI.

LCA cv and LCA range values were significantly different between patients with and without SLI. In the studied population, low values were correlated with the presence of SLI. The threshold values of 9% and 20 degrees were the best parameters for differentiation of these patients. Moreover, despite the absence of a significant difference, there was a trend toward lower LCA max values in patients with SLI. With a RUD manoeuver, 4DCT allowed to identify and quantify the lunate instability in extension or DISI and confirmed the SLI status with an excellent interobserver reproducibility.

Contrary to Rauch et al., 13 our groups were defined using combined radiographic and CT arthrogram data, which better reflects our current practice when making a diagnosis. However, according to those authors, the best differentiation of patients with and without SLL tears was achieved with the LCA cv , LCA range , and LCA max .

Despite the small sample size of the questionable SLI group ( n = 5), when it was compared with the negative SLI groups, the LCA cv and LCA range values were clearly lower in the questionable SLI group. Given the significant difference found, those two parameters appear to be the most relevant for differentiating between these two groups. Also, the LCA cv and LCA range values were fairly similar between the positive SLI patients and questionable SLI patients.

DISI deformity is an important element of the pathogenesis of SLI. Classically described as a lunate dorsiflexion with a rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid, static SLI manifests itself as a complex deformity with posterior subluxation of the unit formed by the scaphoid and the capitate. 5 6 Omori et al, 15 in a three-dimensional analysis of the DISI deformity in the scapholunate dissociated wrists confirmed the lunate is extended and supinated secondarily to SLI. Thus, these positional abnormalities of the scaphoid and lunate contribute in the development of SLAC wrist. The posterior radioscaphoid contact and the lunocapitate decentering are the origin of the radioscaphoid and midcarpal osteoarthritis that later appears. 16

Up to now, evaluation of DISI deformity was made using static imaging methods, without assessing carpal bone position during motion, which may be of interest for the diagnostic SLI. On lateral radiographic view or sagittal CT images, DISI typically demonstrates dorsal tilt of the lunate with an increase of SLA and LCA. 10 In our study, for the both readers, on the radiographic analysis, SLA and LCA values were not systematically correlated. Koh et al 17 suggested with their study that even minimal degrees of wrist flexion-extension (from 20 degrees of flexion to 20 degrees of extension) can affect the measurements of carpal measurements on lateral radiographs, such as the SLA and the LCA. Also, one of the advantages of 4DCT is that it gets around superimposition phenomenon and errors related to the patient's wrist position during standard radiographs or CT scan. Thus, LCA on 4DCT is interesting because it is quantitative and reproducible. LCA could be used as a single parameter for the DISI deformity and lunate motion amplitude assessment with potential surgical implications. The presence of a lunate dorsiflexion and its quantification could be used as a marker of the biomechanical importance of the scapholunate complex (SLL and extrinsic ligaments) injury and the severity of SLI. Pérez et al, in a cadaveric study, evaluated the role of the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid, and dorsal intercarpal (DIC) ligaments in preventing DISI. 18 To produce that deformity, SLL injuries require the associated disruption of at least one extrinsic ligament, stabilizer of the scaphoid or lunate. Mitsuyasu et al had already highlighted the essential role of the DIC in stabilizing the scaphoid and lunate and preventing DISI deformity in cases of SLI. 19 Thus, it might be possible to identify and treat patients with an early stage of SLI characterized by a partial SLL tears associated with an extrinsic ligament injury. 20 21 22

As for the type of movement used during 4DCT, Abou Arab et al 12 and Rauch et al 13 stated that the RUD movement was better at detecting SLL lesions than clenched fist movements. According to these authors, analyzing the carpus during RUD movements has better diagnostic performance and superior reproducibility than during clenched fist movements.

The primary limitation of our study is the small number of patients in each group, especially the questionable SLI group ( n = 5). Thereby, further studies are necessary to explore this group of patients. Second, the SLL ruptures and SLI were not confirmed by arthroscopy, which is generally considered the true reference standard for the diagnosis. However, CT arthrogram has a high performance for the diagnosis of SLL tears (95% sensitivity and 86% specificity) 23 and arthroscopy is an invasive procedure that places the patient at risk of an infection, nerve lesion, pain, or stiffness. 24 Also, it is currently impossible to quantify the DISI deformity during arthroscopy. 4DCT data could be beneficial since arthroscopy scores 7 8 for SLI diagnosis are known to have inter- and intraobserver errors, 25 making them less reproducible than 4DCT. Third, the amplitude of the RUD movement was not standardized, thus varied from one patient to another. In our study, the mean RUD amplitude was fairly similar between the three groups. This parameter did not seem to have influence the diagnostic performance of 4DCT.

Lastly, implementation of this new imaging modality requires training of the medical staff and also teaching the patient beforehand how to perform the movement correctly without moving the forearm.

Conclusion

Given our study's findings, 4DCT appeared as a quantitative relevant tool for the evaluation of DISI deformity in cases of SLI, including for patients presenting with questionable initial radiography findings. LCA analysis was invariably measurable and reproducible. LCA cv and LCA range were the best parameters to identify patients with and without SLI. Values under 9% and 20 degrees were strongly associated with SLI. Abnormal LCA values, especially CV and range, seem to be indicative of significant biomechanical changes in the dissociated wrists with potential implications for patient treatment. The continuation of our prospective study is necessary to fully appreciate the prognostic value of LCA.

Funding Statement

Funding None.

Conflict of Interest P.A.G.T. and A.B. participate on a non-remunerated research contract with TOSHIBA Medical Systems for the development and clinical testing of postprocessing tools for musculoskeletal CT. The remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Note

All patients gave their informed consent for this study.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by our institutional review board and by the local ethics committee (PERSONAL PROTECTION COMMITTEE EST-III, VANDŒUVRE-LES-NANCY, France). This study was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry (no. NCT02401568).

References

- 1.Athlani L, Pauchard N, Detammaecker R. Treatment of chronic scapholunate dissociation with tenodesis: a systematic review. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2018;37(02):65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.hansur.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford K, Owusu-Sarpong N, Day C, Iorio M. Scapholunate ligament reconstruction: a critical analysis review. JBJS Rev. 2016;4(04):e41–e48. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.O.00060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson H K, Ballet F L. The SLAC wrist: scapholunate advanced collapse pattern of degenerative arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(03):358–365. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80223-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linscheid R L, Dobyns J H, Beabout J W, Bryan R S. Traumatic instability of the wrist: diagnosis, classification, and pathomechanics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84(01):142. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson H, Ottoni L, Pitts E C, Handal A G. Rotary subluxation of the scaphoid: a spectrum of instability. J Hand Surg [Br] 1993;18(01):62–64. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(93)90199-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kitay A, Wolfe S W. Scapholunate instability: current concepts in diagnosis and management. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(10):2175–2196. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dreant N, Dautel G. Development of a arthroscopic severity score for scapholunate instability [in French] Chir Main. 2003;22(02):90–94. doi: 10.1016/s1297-3203(03)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geissler W B. Arthroscopic management of scapholunate instability [in French] Chir Main. 2006;25 01:S187–S196. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taleisnik J. Current concepts review. Carpal instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(08):1262–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsen C F, Amadio P C, Gilula L A, Hodge J C. Analysis of carpal instability: I. Description of the scheme. J Hand Surg Am. 1995;20(05):757–764. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao K, Breighner R, Holmes D, III, Leng S, McCollough C, An K N.A technique for quantifying wrist motion using four-dimensional computed tomography: approach and validationJ Biomech Eng 2015;137(07): [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Abou Arab W, Rauch A, Chawki M B. Scapholunate instability: improved detection with semi-automated kinematic CT analysis during stress maneuvers. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(10):4397–4406. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauch A, Arab W A, Dap F, Dautel G, Blum A, Gondim Teixeira P A. Four-dimensional CT analysis of wrist kinematics during radioulnar deviation. Radiology. 2018;289(03):750–758. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gondim Teixeira P A, Formery A S, Hossu G. Evidence-based recommendations for musculoskeletal kinematic 4D-CT studies using wide area-detector scanners: a phantom study with cadaveric correlation. Eur Radiol. 2017;27(02):437–446. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4362-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omori S, Moritomo H, Omokawa S, Murase T, Sugamoto K, Yoshikawa H. In vivo 3-dimensional analysis of dorsal intercalated segment instability deformity secondary to scapholunate dissociation: a preliminary report. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38(07):1346–1355. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laulan J. Rotatory subluxation of the scaphoid: pathology and surgical management [in French] Chir Main. 2009;28(04):192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koh K H, Lee H I, Lim K S, Seo J S, Park M J. Effect of wrist position on the measurement of carpal indices on the lateral radiograph. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(05):530–541. doi: 10.1177/1753193412468543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez A J, Jethanandani R G, Vutescu E S, Meyers K N, Lee S K, Wolfe S W. Role of ligament stabilizers of the proximal carpal row in preventing dorsal intercalated segment instability: a cadaveric study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101(15):1388–1396. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.18.01419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitsuyasu H, Patterson R M, Shah M A, Buford W L, Iwamoto Y, Viegas S F. The role of the dorsal intercarpal ligament in dynamic and static scapholunate instability. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(02):279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathoulin C L. Indications, techniques, and outcomes of arthroscopic repair of scapholunate ligament and triangular fibrocartilage complex. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2017;42(06):551–566. doi: 10.1177/1753193417708980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degeorge B, Coulomb R, Kouyoumdjian P, Mares O. Arthroscopic dorsal capsuloplasty in scapholunate tears EWAS 3: preliminary results after a minimum follow-up of 1 year. J Wrist Surg. 2018;7(04):324–330. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1660446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ho P C, Wong C W, Tse W L. Arthroscopic-assisted combined dorsal and volar scapholunate ligament reconstruction with tendon graft for chronic SL instability. J Wrist Surg. 2015;4(04):252–263. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1565927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bille B, Harley B, Cohen H. A comparison of CT arthrography of the wrist to findings during wrist arthroscopy. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(06):834–841. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee Y H, Choi Y R, Kim S, Song H T, Suh J S. Intrinsic ligament and triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) tears of the wrist: comparison of isovolumetric 3D-THRIVE sequence MR arthrography and conventional MR image at 3 T. Magn Reson Imaging. 2013;31(02):221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Obdeijn M C, Tuijthof G J, van der Horst C M, Mathoulin C, Liverneaux P. Trends in wrist arthroscopy. J Wrist Surg. 2013;2(03):239–246. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1351355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]