Abstract

Objective:

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) has a primary role in the prophylaxis and treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and may be protective against thrombosis in SLE. Optimal weight-based dosing of HCQ is unknown. This study examined the usefulness of HCQ blood monitoring in predicting thrombosis risk in a longitudinal SLE cohort.

Methods:

HCQ levels were serially quantified from EDTA whole blood by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Mean HCQ blood levels calculated prior to thrombosis or until the last visit were compared between patients with and without thrombosis using t-test. Pooled logistic regression was used to analyze the association between rates of thrombosis and HCQ blood level.

Results:

In 739 patients with SLE, thrombosis occurred in 38 patients (5.1%). Mean HCQ blood level was lower in patients who developed thrombosis vs without thrombosis (720±489 vs 935±580, p=0.025). Thrombosis rates were reduced by 12% for every 200 ng/mL increase in the most recent HCQ blood level (0.87 [0.78, 0.98], p=0.025) and by 13% for mean HCQ blood level (rate ratio 0.87 [0.76,1.00], p=0.056). Thrombotic events were reduced by 69% in patients with mean HCQ blood levels >1068 ng/mL vs <648 ng/mL (0.31 [0.11, 0.86], p=0.024). This remained significant after adjustment for confounders (0.34 [0.12, 0.94], p=0.037).

Conclusion:

Low HCQ blood levels are associated with thrombotic events in SLE. Longitudinal measurement of HCQ levels may allow for personalized HCQ dosing strategies. Recommendations for empirical dose reduction may reduce or eliminate the benefits of HCQ in this high-risk population.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombosis, hydroxychloroquine

Introduction

Thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Thrombosis in SLE is multifactorial with antiphospholipid antibodies, disease activity, nephrotic-range proteinuria and co-morbidities, including hypertension, all playing a role. Thrombosis in SLE represents immunothrombosis, with cross-talk between the coagulation and complement systems augmenting hypercoagulability (1). In particular, the SLE thrombosis risk equation found that the lupus anticoagulant, low complement component C3, and C4d bound to platelets all contributed significantly to the risk of thrombosis occurring over the past five years (2).

Multiple retrospective and a few prospective studies (3–13) have found that hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) reduces the risk of arterial and venous thrombosis. An overall thrombosis odds ratio of 0.51 favoring hydroxychloroquine was found by Sankhyan et al (14). There are multiple mechanisms of action of hydroxychloroquine (summarized in (13)) that contribute to the benefit of hydroxychloroquine including an anti-platelet effect, reduction in antiphospholipid antibodies, and a positive rheologic effect. Hydroxychloroquine may also exert protective effects by preventing disruption of the annexin A5 anticoagulant “shield”, reduction of soluble tissue factor, and inhibition of endosomal NADPH oxidase induction (15–17). In addition, it has benefit as it reduces flares (18), increases low C3, improves renal outcome (19) and reduces co-morbid factors including diabetes (20) and hyperlipidemia (5).

Despite its widespread use since the 1950s (21), optimal dosing of HCQ in SLE is unknown. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of HCQ are complex and influenced by differences in gastrointestinal and tissue-specific absorption, lysosomal sequestration and melanin binding, and both hepatic metabolism and renal excretion (22,23). Studies on the benefit of hydroxychloroquine in reducing thrombosis in SLE were done using older dosing regimens. More recently, concern about retinopathy increased after a retrospective Kaiser-Permanente study (24). A prospective study limited to SLE patients confirmed that retinopathy was more common than previously understood, but at 16 years of use the frequency was only 11.5%, using sensitive screening tests including optical coherence tomography (25).

The retrospective Kaiser-Permanente study was the basis for the revised American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) guidance to limit hydroxychloroquine dosing to less than 5 mg/kg absolute body weight (26). The Kaiser-Permanente study, however, was based on pharmacy dispensing records and not on the prescribed dose (which is higher due to partial adherence). A study of 412 SLE patients recently suggested that empirical dose reduction following AAO guidelines was not associated with increased short-term risk of lupus-related end-organ damage, but importantly did not look at therapeutic drugs levels or thromboembolic events (27).

The role of monitoring hydroxychloroquine blood levels has been studied for the last decade. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels are preferred over plasma levels due to binding of hydroxychloroquine to red blood cells and its lysosomal sequestration in leukocytes (28). Hydroxychloroquine blood levels reflect hydroxychloroquine intake and tissue stores. The coefficient of variation is small (29). The highest tertile of hydroxychloroquine blood levels in the prospective study did predict later retinopathy, indicating a role in monitoring blood levels to reduce toxicity (25). In this study, we asked whether hydroxychloroquine blood levels were associated with thrombosis.

Methods

Patients

The study population was patients in the Hopkins Lupus Cohort, a longitudinal study of outcomes of SLE. One of its original specific aims starting 35 years ago was the longitudinal study of antiphospholipid antibodies in SLE to predict thrombosis. All patients met the revised ACR classification criteria (30) or the SLICC classification criteria (31) for SLE. The study protocol included visits every 3 months, with laboratory tests performed to complete the SELENA version of the SLE Disease Activity Index SLEDAI (32). Extra visits were scheduled as needed for disease activity or complications. The Hopkins Lupus Cohort was approved on a yearly basis by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (Study ID NA_00039294). All patients provided written, informed consent.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the study planning, design or execution.

Hydroxychloroquine quantification in blood

To be included, the patient must have had one or more hydroxychloroquine blood levels measured. If the patient had to discontinue hydroxychloroquine due to retinopathy or intolerance, visits off hydroxychloroquine were censored. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels done at the Johns Hopkins clinical laboratories were included. Hydroxychloroquine levels were quantified from EDTA whole blood by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as described by Chambliss et al, with measurements being linear over a range of 16 to 4000 ng/mL (29). The coefficient of variation was <3%.

Assessment of thrombotic events

Venous (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, superficial venous thrombosis, other venous thrombosis) or arterial (stroke, myocardial infarction, digital gangrene or other arterial thrombosis) were recorded at each visit according to the cohort protocol and confirmed through review of medical records. For example, deep vein thrombosis required ultrasound or equivalent imaging and pulmonary embolus required V/Q scan, CT angiogram or equivalent imaging. Stroke required brain CT or MRI scan confirmation. Myocardial infarction required confirmation by EKG, cardiac enzymes or myocardial imaging. Other arterial thrombosis was defined as appropriate for the site involved.

Patients were excluded if their thrombotic event occurred prior to the first hydroxychloroquine measurement. Follow up for each patient was censored after the first thrombotic event.

Statistical methods

Between-person and within-person correlation coefficients were used to measure the strength of the linear association between HCQ blood levels and commonly prescribed HCQ doses from 4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg. Student’s t-test was used to evaluate the differences in mean HCQ blood levels between the thrombosis and no thrombosis group.

To facilitate the time-to-event analysis, we constructed a data set with one record for each month of follow up for each patient after the first measurement of HCQ blood levels. Each record contained information on the patient’s clinical and medication history up to that month. For each person-month, we created a variable indicating whether a thrombotic event had occurred during that month. In addition, mean HCQ blood levels over all previous months were calculated.

To calculate the rate of thrombosis in each subgroup, we calculated the number of thrombotic events divided by the number of person months at risk and converted this rate to the rate per 1000 person years. To assess the relationship between HCQ blood levels (mean or most recent measures), we used pooled logistic regression (33). Unadjusted and adjusted results were reported. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4.

Results

Clinical characteristics

739 patients were eligible to be included in this analysis. They were 93% female, 46% Caucasian, 43% African-American, with a mean age of 43 years at the time the hydroxychloroquine blood level measurements commenced. The cumulative ACR or SLICC classification criteria included 43% malar rash, 18% discoid rash, 49% photosensitivity, 53% oral/nasal ulcers, 69% arthritis, 44% proteinuria, 41% pleurisy, 20% pericarditis, 2% psychosis, 6% seizures, 97% ANA, 61% anti-dsDNA, 25% anti-Sm, 21% lupus anticoagulant (by dRVVT with confirmatory testing), 51% leukopenia, 18% thrombocytopenia, 8% hemolytic anemia and 18% positive Coombs test.

Thrombotic events

This analysis was based on 2330 person years of follow up from 739 patients with SLE. Incident thrombosis occurred in 38 patients (5.1%) during follow-up, giving an overall rate of 16.3 per 1000 person years. There were 18 patients with venous thrombotic events (15 DVT/PE, 1 other venous thrombosis, and 2 superficial thrombosis) representing 3% of the total patients. The 2 episodes of superficial thrombophlebitis were not included in the analysis. There were 20 patients with arterial thrombotic events (13 strokes, 3 myocardial infarctions, 2 digital gangrene and 5 other sites of arterial thrombosis).

Prescribed hydroxychloroquine doses did not predict hydroxychloroquine blood levels

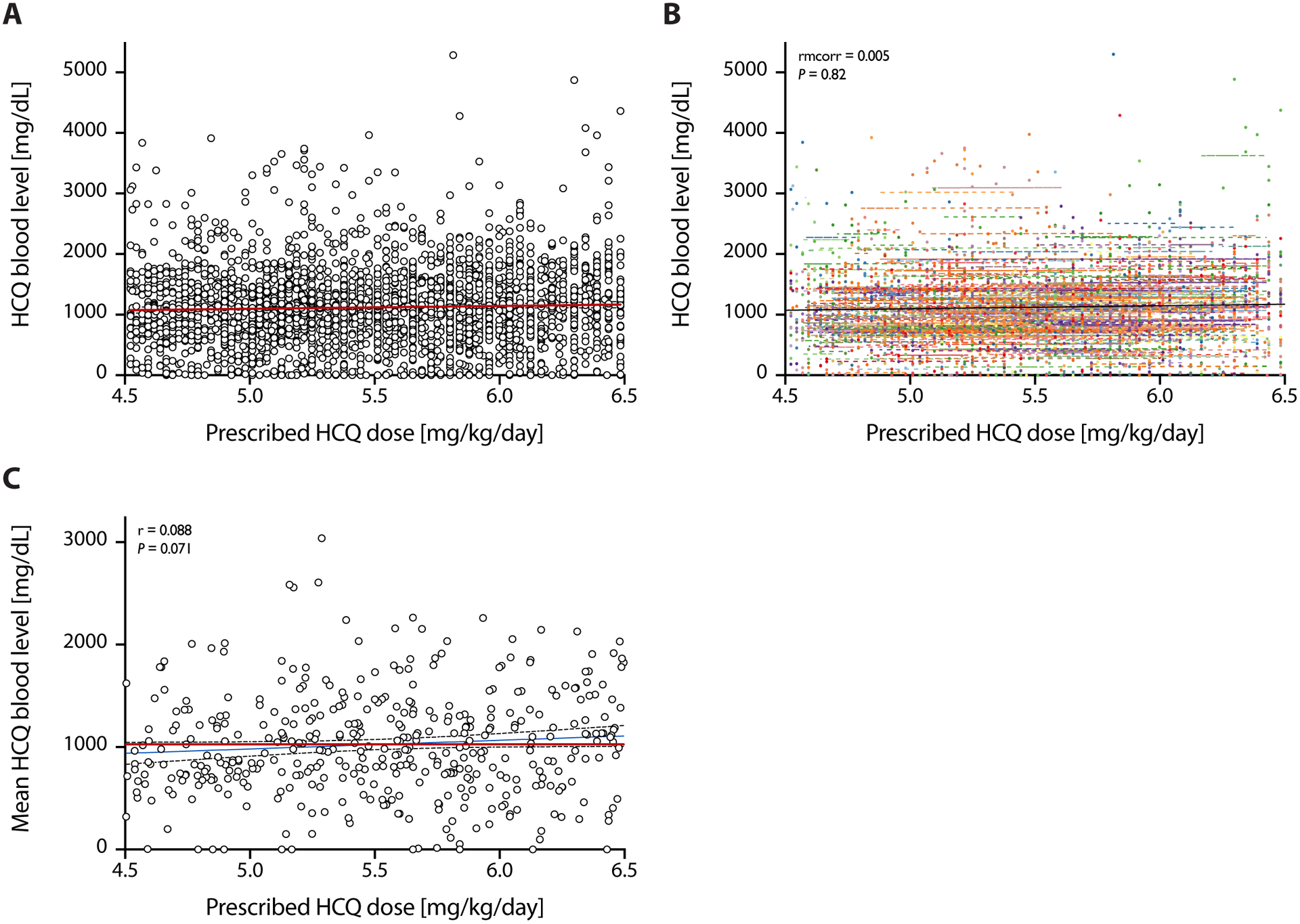

Figure 1 shows the lack of correlation between the prescribed hydroxychloroquine dose in mg/kg (through the range of clinical use of 4.5 mg/kg to 6.5 mg/kg per day) and the hydroxychloroquine whole blood level. In the within-person level using repeated measure correlation (rmcorr), the HCQ blood level did not change as prescribed dose increased (rmcorr=0.01). In the between-person analysis, there was a non-significant relationship between mean HCQ blood level and prescribed dose (r=0.088).

Figure 1. Commonly Prescribed Hydroxychloroquine Doses Do Not Predict Hydroxychloroquine Whole Blood Levels.

(A) Pooled data on prescribed doses of hydroxychloroquine (in mg/kg/day) and hydroxychloroquine levels (in mg/dL) as measured by HPLC in whole blood. (B) Within-person correlation of prescribed doses and whole blood levels: Observations from the same patient are given the same color, with corresponding lines to show the rmcorr fit for each patient’s data. (C) Between-person correlation of prescribed doses and whole blood levels: averaged by patient. Both show weak and not statistically significant correlations.

Potential confounders

Table 1 shows the univariate analysis of several potential confounders in the analysis of thrombosis including gender, ethnicity, age, body mass index, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking, history of the lupus anticoagulant and low C3. African-Americans were more likely to have had a thrombotic event (p=0.0233) compared to Caucasians. The most important confounders were hypertension (p=0.0176) and low C3 (p=0.0173).

Table 1.

Association of Clinical Factors with Thrombosis

| Subgroup | Observed No. of TEs | Person-years of follow up | Rate of events per 1000 person-years | Rate ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 38 | 2330 | 16.3 | ||

| Age at first HCQ | |||||

| <40 | 17 | 990 | 17.2 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 40–49 | 9 | 488 | 18.4 | 1.07 (0.48, 2.41) | 0.86 |

| 50–59 | 9 | 489 | 18.4 | 1.07 (0.48, 2.41) | 0.87 |

| >=60 | 3 | 363 | 8.3 | 0.48 (0.14, 1.64) | 0.24 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 2 | 174 | 11.5 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Female | 36 | 2156 | 16.7 | 1.45 (0.35, 6.03) | 0.61 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 11 | 1096 | 10.0 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| African American | 23 | 998 | 23.0 | 2.3 (1.12, 4.72) | 0.02 |

| Other | 4 | 236 | 17.0 | 1.69 (0.54, 5.32) | 0.37 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 24 | 1616 | 14.9 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Ever | 14 | 712 | 19.7 | 1.33 (0.69, 2.56) | 0.40 |

| BMI | |||||

| <20 | 3 | 193 | 15.5 | 1.96 (0.49, 7.84) | 0.34 |

| 20–25 | 6 | 757 | 7.9 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| 25–30 | 14 | 668 | 20.9 | 2.64 (1.02, 6.89) | 0.046 |

| >=30 | 15 | 710 | 21.1 | 2.67 (1.03, 6.87) | 0.042 |

| History of RVVT | |||||

| No | 27 | 1831 | 14.7 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 11 | 494 | 22.3 | 1.51 (0.75, 3.05) | 0.25 |

| History of low C3 | |||||

| No | 9 | 1013 | 8.9 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 29 | 1317 | 22.0 | 2.48 (1.17, 5.24) | 0.017 |

| History of hypertension | |||||

| No | 11 | 1136 | 9.7 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 27 | 1194 | 22.6 | 2.34 (1.16, 4.72) | 0.018 |

| History of hyperlipidemia | |||||

| No | 17 | 1229 | 13.8 | 1.00 (ref) | |

| Yes | 21 | 1096 | 19.2 | 1.39 (0.73, 2.63) | 0.32 |

Thrombotic events were associated with a lower mean hydroxychloroquine blood level. Table 2 shows the cross-sectional analysis. For any thrombosis, the mean hydroxychloroquine blood level was significantly lower (p=0.0247). For the sub-analysis for venous (p=0.0747) and arterial thrombotic events (p=0.1735) the results were similar, but were not statistically significant (due to lower power).

Table 2.

Association of Thrombotic Events with Mean Hydroxychloroquine Whole Blood Level

| Mean HCQ blood levels | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombotic event | No event | p-value | |

| Any thrombosis | 720±489 | 935±580 | 0.0247 |

| Any Venous | 688±389 | 931±580 | 0.0747 |

| DVT/PE | 623±399 | 931±578 | 0.0406 |

| Any arterial | 751±566 | 929±577 | 0.1735 |

| Stroke | 764±674 | 927±575 | 0.3113 |

DVT: Deep venous thrombosis; PE: pulmonary embolism

Prospective thrombotic events and adjusted analyses

Table 4 shows the rate ratio for the mean hydroxychloroquine blood level per 200 ng/mL increments. Both the mean (p=0.0296) and the hydroxychloroquine blood level closest to the thrombotic event (p=0.0134) were statistically significant. This relationship remained statistically significant when adjusted first for age, ethnicity, and lupus anticoagulant; and also if adjusted for low C3 and hypertension.

Table 4.

Rate Ratios for Risk of Prospective Thrombotic Events Based on Hydroxychloroquine Whole Blood Levels

| RR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted RR (95% CI)1 | Adjusted p-value1 | Adjusted RR (95% CI)2 | Adjusted p-value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean HCQ blood level (per 200 ng/ml increase) | 0.86 (0.75, 0.99) | 0.030 | 0.87 (0.76, 1.00) | 0.051 | 0.87 (0.76, 1.00) | 0.056 |

| Most recent HCQ blood level (per 200 ng/ml increase) | 0.86 (0.77, 0.97) | 0.013 | 0.87 (0.78, 0.98) | 0.023 | 0.87 (0.78, 0.98) | 0.025 |

Adjusted for age, ethnicity, and LAC

Adjusted for age, ethnicity, LAC, C3, and HTN

RR: Rate ratio; LAC: lupus anticoagulant; C3: complement component C3; HTN: arterial hypertension

Target hydroxychloroquine blood level and risk of thrombotic events

Figure 2 shows Forest plots of rate ratios of thrombotic events by tertiles of mean and most recent hydroxychloroquine blood levels. A mean whole blood level of greater than 1068 ng/mL and a most recent whole blood level of greater than 1192 ng/mL, as defined by tertiles, were protective against thrombosis in our cohort (adjusted rate ratio 0.34 [0.12, 0.94], p=0.0374 and 0.40 [0.16, 1.04], p=0.0614, respectively, with the latter p-value just missing statistical significance). The event rates per 1000 person-years, unadjusted rate ratios, and rate ratios adjusted for age, ethnicity, and lupus anticoagulant are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 2. Forest Plots of Rate Ratios for Thrombosis Risk by Mean and Most Recent Hydroxychloroquine Whole Blood Level.

(A) Forest plot of rate ratios for thrombotic events by tertiles of most recent HCQ blood level, adjusted for age, ethnicity, and presence of lupus anticoagulant (left) and bar graph of thrombotic event rates/ 1000 patient years by tertiles of most recent HCQ blood level (right). (B) Same as A, but for tertiles of mean HCQ blood level. *P: indicates p-value of adjusted analyses.

Table 3. Event Rates, Unadjusted and Adjusted Rate Ratios for Thrombosis by Tertiles of Mean and Most Recent Hydroxychloroquine Whole Blood Level.

HCQ blood levels are measured in ng/mL. The P value for trend was p=0.0170 for most recent HCQ blood level and p=0.0062 for mean HCQ blood level.

| Subgroup | Observed No. of TEs | Person-years of follow up | Rate of events per 1000 pys | Rate ratio | p-value | Rate ratio adjusted for age, ethnicity, LAC | p-value adjusted |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 36 | 2326 | 15.5 | ||||

| Most recent HCQ blood level tertiles | |||||||

| 0–667 | 16 | 776 | 20.6 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 668–1191 | 14 | 775 | 18.1 | 0.88 (0.43, 1.8) | 0.7196 | 0.97 (0.47, 2.01) | 0.94 |

| ≥1192 | 6 | 775 | 7.7 | 0.38 (0.15, 0.96) | 0.0408 | 0.4 (0.16, 1.04) | 0.061 |

| Mean HCQ blood level tertiles | |||||||

| 0–648 | 16 | 777 | 20.6 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | ||

| 648–1068 | 15 | 776 | 19.3 | 0.94 (0.46, 1.9) | 0.8595 | 1.05 (0.52, 2.14) | 0.89 |

| ≥1068 | 5 | 773 | 6.5 | 0.31 (0.11, 0.86) | 0.0237 | 0.34 (0.12, 0.94) | 0.037 |

Pys: person years

We next determined whether a dose effect for hydroxychloroquine and risk of thrombotic events was present. Indeed, thrombosis rates were reduced by 13% for every 200 ng/mL increase in mean HCQ blood level (rate ratio 0.87 [0.76, 1.00], p=0.0559) and, statistically so, for the most recent HCQ blood level (0.87 [0.78, 0.98], p=0.0249) after adjusting for age, ethnicity, lupus anticoagulant, C3, and hypertension. Thrombotic event rates were reduced by 69% in patients with mean HCQ blood levels ≥1068 vs. <648 ng/mL (0.31 [0.11, 0.86], p=0.0237). This remained significant after adjustment for confounders (0.34 [0.12, 0.94], p=0.0374) (Table 3). Together, these data suggest that hydroxychloroquine whole blood levels were predictive of thrombotic events in SLE in a dose-dependent manner and suggest an opportunity for personalized drug dosing approaches beyond empirical dosing recommendations.

Discussion

Hydroxychloroquine has been the mainstay of SLE therapy for many decades and is an accepted background medication in SLE (34,35). Older dosing guidelines recommending up to 6.5 mg/kg actual body weight (36) have now been challenged, based on an analysis of the retrospective Kaiser-Permanente study (24). The new recommendations advise to use less than 5 mg/kg ideal body weight of hydroxychloroquine to reduce the risk of future retinopathy (26). The dilemma remains: how do we ensure that patients receive the full benefit of hydroxychloroquine, but at the same time, reduce risk of retinopathy? Given the extensive tissue distribution and long terminal half-life of hydroxychloroquine, whole blood levels integrate drug exposure, patient-specific differences in metabolism/clearance, and compliance over weeks, allowing for a more accurate risk assessment than using the prescribed dose/body weight (37).

SLE increases the risk of both venous (38) and arterial thrombosis (39). Of hydroxychloroquine’s many benefits in SLE, reduction in arterial and venous thrombotic risk has been proven in many studies (13). In the current study, the data showed that a lower mean hydroxychloroquine whole blood level – and, importantly, a lower hydroxychloroquine whole blood level closest to the thrombotic event – were associated with higher thrombosis risk. There was a dose response (Figure 2 and Table 3), demonstrating that a mean hydroxychloroquine whole blood level of greater than 1068 ng/mL and a most recent level of greater than 1192 ng/mL conferred significant protection. Importantly, for each 200 ng/mL increase in the most recent hydroxychloroquine whole blood level, there was a 13% reduction in the rate of thrombosis (Table 4). While our study was not powered to assert the benefit of hydroxychloroquine for specific thrombotic events, similar trends were observed for both arterial and venous thrombosis. Similar results were obtained for the optimum blood level to control disease activity in work from Costedoat-Chalumeau et al., with 1,000 ng/mL whole blood level as the clinically therapeutic goal using receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (37).

Our study suggested the usefulness of hydroxychloroquine blood level monitoring for ensuring the benefit of hydroxychloroquine for thrombosis reduction. Hydroxychloroquine whole blood levels more accurately reflect hydroxychloroquine exposure (versus plasma or serum levels) and are indicative of the last month’s adherence. Importantly, there was no correlation between the prescribed dose and the hydroxychloroquine blood level over the range (4.5 to 6.5 mg/kg) used in clinical practice, highlighting the need for personalized hydroxychloroquine drug level-guided therapy and dose adjustment.

The observational study design has potential limitations. These include the potential for confounding by unknown variables that we did not include in our modelling. The additional limitations include the single site, single rheumatologist, and small numbers of prospectively ascertained thrombotic events.

In conclusion, empirical hydroxychloroquine dose reduction to less than 5 mg/kg might reduce or eliminate the benefit of hydroxychloroquine in thrombosis prevention. Targeting the hydroxychloroquine blood level to 1068 ng/mL was associated with protection. It should be possible to target this level and still avoid the “upper tertile” that we previously proved was associated with retinopathy. Routine clinical integration of hydroxychloroquine blood level measurement offers an opportunity for personalized drug dosing and risk management beyond rigid empirical dosing recommendations in patients with SLE.

Acknowledgments

The Hopkins Lupus Cohort (MP) was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01-AR069572. MFK was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health T32AR048522. These findings were presented at the 2019 ACR/ARP Annual Meeting, November 8-13, 2019, Atlanta, GA, (Conference proceedings in Arthritis and Rheumatology vol. 71, Issue S10, October 2019).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Keragala CB, Draxler DF, McQuilten ZK, Medcalf RL. Haemostasis and innate immunity - a complementary relationship. Br J Haematol 2018;180:782–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petri MA, Conklin J, O’Malley T, Dervieux T. Platelet-bound C4d, low C3 and lupus anticoagulant associate with thrombosis in SLE. Lupus Sci Med 2019;6:e000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace DJ. Does hydroxychloroquine sulfate prevent clot formation in systemic lupus erythematosus? Arthritis Rheum 1987;30:1435–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho KT, Ahn CW, Alarcón GS, Baethge BA, Tan FK, Roseman J, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic cohort (LUMINA): XXVIII. Factors predictive of thrombotic events. Rheumatology 2005;44:1303–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petri M, Lakatta C, Magder L, Goldman D. Effect of prednisone and hydroxychloroquine on coronary artery disease risk factors in systemic lupus erythematosus: a longitudinal data analysis. Am J Med 1994;96:254–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaiser R, Cleveland CM, Criswell LA. Risk and protective factors for thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: results from a large, multi-ethnic cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:238–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung H, Bobba R, Su J, Shariati-Sarabi Z, Gladman DD, Urowitz M, et al. The protective effect of antimalarial drugs on thrombovascular events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:863–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu C-Y, Lin Y-S, Su Y-J, Lin H-F, Lin M-S, Syu Y-J, et al. Effect of long-term hydroxychloroquine on vascular events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a database prospective cohort study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:2212–2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tektonidou MG, Laskari K, Panagiotakos DB, Moutsopoulos HM. Risk factors for thrombosis and primary thrombosis prevention in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with or without antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erkan D, Yazici Y, Peterson MG, Sammaritano L, Lockshin MD. A cross-sectional study of clinical thrombotic risk factors and preventive treatments in antiphospholipid syndrome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:924–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sisó A, Ramos-Casals M, Bové A, Brito-Zerón P, Soria N, Muñoz S, et al. Previous antimalarial therapy in patients diagnosed with lupus nephritis: influence on outcomes and survival. Lupus 2008;17:281–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thrombosis Petri M. and systemic lupus erythematosus: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort perspective. Scand J Rheumatol 1996;25:191–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petri M Use of hydroxychloroquine to prevent thrombosis in systemic lupus erythematosus and in antiphospholipid antibody–positive patients. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2011;13:77–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankhyan P, Cook, Boonpheng B, Cook CT. Hydroxychloroquine and the risk of thrombotic events in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2018;70. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rand JH, Wu X-X, Quinn AS, Ashton AW, Chen PP, Hathcock JJ, et al. Hydroxychloroquine protects the annexin A5 anticoagulant shield from disruption by antiphospholipid antibodies: evidence for a novel effect for an old antimalarial drug. Blood 2010;115:2292–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiber K, Breen K, Parmar K, Rand JH, Wu X-X, Hunt BJ. The effect of hydroxychloroquine on haemostasis, complement, inflammation and angiogenesis in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:120–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Müller-Calleja N, Manukyan D, Canisius A, Strand D, Lackner KJ. Hydroxychloroquine inhibits proinflammatory signalling pathways by targeting endosomal NADPH oxidase. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsakonas E, Joseph L, Esdaile J, Choquette D, Senécal J, Cividino A, et al. A long-term study of hydroxychloroquine withdrawal on exacerbations in systemic lupus erythematosus. The Canadian Hydroxychloroquine Study Group. Lupus 1998;7:80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kasitanon N, Fine DM, Haas M, Magder LS, Petri M. Hydroxychloroquine use predicts complete renal remission within 12 months among patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil therapy for membranous lupus nephritis. Lupus 2006;15:366–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wasko MCM, Hubert HB, Lingala VB, Elliott JR, Luggen ME, Fries JF, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and risk of diabetes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. JAMA 2007;298:187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tye MJ, White H, Appel B, Ansell HB. Lupus erythematosus treated with a combination of quinacrine, hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine. N Engl J Med 1959;260:63–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Collins KP, Jackson KM, Gustafson DL. Hydroxychloroquine: A physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model in the context of cancer-related autophagy modulation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2018;365:447–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JY, Vinayagamoorthy N, Han K, Kwok SK, Ju JH, Park KS, et al. Association of polymorphisms of cytochrome P450 2D6 with blood hydroxychloroquine levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melles RB, Marmor MF. The risk of toxic retinopathy in patients on long-term hydroxychloroquine therapy. JAMA Ophthalmol 2014;132:1453–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petri M, Elkhalifa M, Li J, Magder LS, Goldman DW. Hydroxychloroquine blood levels predict hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Arthritis Rheumatol 2020;72:448–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TYY, Melles RB, Mieler WF. Recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy (2016 revision). Ophthalmology 2016;123:1386–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vázquez-Otero I, Medina-Cintrón N, Arroyo-Ávila M, González-Sepúlveda L, Vilá LM. Clinical impact of hydroxychloroquine dose adjustment according to the American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med 2020;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carlsson H, Hjorton K, Abujrais S, Rönnblom L, Åkerfeldt T, Kultima K. Measurement of hydroxychloroquine in blood from SLE patients using LC-HRMS-evaluation of whole blood, plasma, and serum as sample matrices. Arthritis Res Ther 2020;22:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Füzéry AK, Breaud AR, Emezienna N, Schools S, Clarke WA. A rapid and reliable method for the quantitation of hydroxychloroquine in serum using turbulent flow liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta 2013;421:79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, Masi AT, Mcshane DJ, Rothfield NF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1982;25:1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petri M, Orbai A-M, Alarcón GS, Gordon C, Merrill JT, Fortin PR, et al. Derivation and validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2677–2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petri M, Kim MY, Kalunian KC, Grossman J, Hahn BH, Sammaritano LR, et al. Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med 2005;353:2550–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Agostino RB, Lee ML, Belanger AJ, Cupples LA, Anderson K, Kannel WB. Relation of pooled logistic regression to time dependent Cox regression analysis: the Framingham Heart Study. Stat Med 1990;9:1501–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, Aringer M, Bajema I, Boletis JN, et al. 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:736–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.American College of Rheumatology Ad Hoc Committee on Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Guidelines. Guidelines for referral and management of systemic lupus erythematosus in adults. Arthritis Rheum 1999;42:1785–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marmor MF, Kellner U, Lai TYY, Lyons JS, Mieler WF. Revised recommendations on screening for chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine retinopathy. Ophthalmology 2011;118:415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Amoura Z, Hulot J-S, Hammoud HA, Aymard G, Cacoub P, et al. Low blood concentration of hydroxychloroquine is a marker for and predictor of disease exacerbations in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:3284–3290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Somers E, Magder LS, Petri M. Antiphospholipid antibodies and incidence of venous thrombosis in a cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2002;29:2531–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Merkel PA, Lo GH, Holbrook JT, Tibbs AK, Allen NB, Davis JC, et al. Brief Communication: High Incidence of Venous Thrombotic Events among Patients with Wegener Granulomatosis: The Wegener’s Clinical Occurrence of Thrombosis (WeCLOT) Study. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]