Abstract

Background:

Despite many successful clinical trials to test HIV-prevention interventions for sexual minority men (SMM), not all SMM are reached by these trials. Identifying factors associated with non-participation in these trials could help to ensure the benefits of research extend to all SMM.

Methods:

Prospective participants in New York City and Miami were screened to determine eligibility for a baseline assessment for a mental health/HIV-prevention trial (N = 633 eligible on screen). Logistic regression and classification and regression tree (CART) analysis identified predictors of non-participation in the baseline, among those who were screened as eligible and invited to participate.

Results:

Individuals who reported unknown HIV status were more likely to be non-participators than those who reported being HIV-negative (OR = 2.39; 95% CI: 1.41, 4.04). In New York City, Latinx SMM were more likely to be non-participators than non-Latinx white SMM (OR = 1.81; 95% CI, 1.09, 2.98). A CART model pruned two predictors of non-participation: knowledge of HIV status and age, such that SMM with unknown HIV status and SMM ages 18-19 were less likely to participate.

Discussion:

Young SMM who did not know their HIV status, and thus are more likely to acquire and transmit HIV, were less likely to participate. Additionally, younger SMM (18-19 years) and Latinx SMM in New York City were less likely to participate. The findings suggest the importance of tailored recruitment to ensure HIV-prevention/mental health trials reach all SMM.

Keywords: HIV prevention, sexual minority men, mental health, recruitment and outreach

Resumen

Trasfondo:

A pesar de muchos ensayos clínicos exitosos para probar intervenciones de prevención del VIH para hombres de minorias sexuales (HMS), no todos los HMS son alcanzados por estos ensayos. La identificación de factores asociados con la no participación en estos ensayos podría ayudar a asegurar que los beneficios de la investigación se extiendan a todos los HMS.

Métodos:

Se realizaron evaluaciones de teléfono para determinar la elegibilidad para la visita inicial para un ensayo de salud mental/prevención del VIH (N = 633 elegibles en las evaluaciones). La regresión logística y el análisis de arboles de regresión y clasificación (ARC) identificaron predictores de no participación en la visita inicial, entre aquellos que fueron evaluados como elegibles e invitados a participar.

Resultados:

Los individuos que reportaron estado desconocido de VIH fueron más probables a ser no participantes que aquellos que reportaron ser VIH negativos (RP = 2.39; IC 95%: 1.41, 4.04). En la ciudad de Nueva York, HMS latinx eran más probable a no participar que los HMS blancos no latinx (RP = 1.81; IC 95%, 1.09, 2.98). Un modelo de ARC podó dos predictores de no participación: el conocimiento del estado de VIH y la edad, tal que los HMS con estado desconocido del VIH y las HMS de 18-19 años eran menos probables a participar.

Discusión:

Los HMS jóvenes que no conocían su estado de VIH, y por lo tanto eran más probables a adquirir y transmitir el VIH, tenían menos probabilidades de participar. Además, las HMS más jóvenes (18-19 años) y los HMS latinx en la ciudad de Nueva York eran menos probables a participar. Los resultados sugieren la importancia de un reclutamiento personalizado para garantizar que los ensayos de prevención del VIH y salud mental lleguen a todos los SMM.

Sexual minority men (SMM) and other men who have sex with men (MSM)1 represent approximately seven percent of the male population in the United States, yet accounted for more than 83% of new HIV diagnoses among men and 68% of all new diagnoses in 2016 (1). Although HIV diagnoses have remained relatively stable among MSM overall, HIV is not equally distributed among MSM in the US, with younger MSM bearing a greater burden of HIV incidence (2). From 2014 to 2018, HIV incidence among MSM was greatest among individuals aged 25 to 34 years old (2). Latinx SMM are the only racial/ethnic subgroup of MSM with increasing HIV incidence (2) and Black SMM show stable but high HIV incidence and prevalence, compared to non-Latinx white SMM (1,2).

In addition to these HIV disparities, structural and social circumstances contribute to mental health disparities among sexual minority people, who are more likely to experience mental health and substance use concerns (hereafter referred to collectively as “behavioral health concerns”), including depression, anxiety, psychological distress, self-harm behavior, suicidality, and alcohol and other substance use concerns compared to heterosexual peers (3–5). Younger sexual minority populations display even more behavioral health concerns than older sexual minority populations (6,7) due to a variety of factors including less access to culturally competent providers (8) and added stress associated with parental and/or peer rejection (9), sexual orientation concealment (10), and workplace discrimination (11). These disparities, driven by minority stress (12–15), are in turn associated with greater likelihood of HIV acquisition among SMM (16–22). The synergistic co-occurrence of these behavioral health concerns and structural factors that place some individuals at higher odds of HIV acquisition are referred to as “synergistic epidemics” or a “syndemic” (23,24).

Because of the disproportionate impact of HIV and co-occurring behavioral health disparities on young SMM, it is essential to engage this population in clinical trials that seek to: (1) develop evidence-based interventions for addressing behavioral and sexual health disparities and (2) deliver interventions resulting from clinical trials to this population, thereby mitigating disparities. Given racial/ethnic and age-related disparities in the impact of HIV on SMM, there is also a need to develop and deliver tailored interventions for addressing these disparities to those hardest hit by the HIV epidemic, including young SMM, Latinx SMM, and Black SMM. Yet, HlV-prevention research does not equally engage all subgroups of SMM due to challenges associated with recruiting, enrolling, and retaining this population in research (25).

The research community has often considered people who identify as sexual minorities as “hard to reach” or “hidden” due to being less readily accessible when it comes to recruitment into studies (26,27). Studies examining predictors of MSM participating in HIV-prevention trials found that MSM who were younger, had less education, did not know their HIV status, or were more concealed or did not identify as gay were less likely to enroll (28,29). Others have found racial/ethnic and age-related disparities in MSM’s participation in HIV vaccine trials, with older and non-Latinx white MSM more likely to participate (29–31). Black and Latinx SMM are also less likely to participate in clinical research compared to non-Latinx white SMM (32,33).

Lower research participation among Black and Latinx SMM has been attributed to multilevel factors such as medical mistrust, lack of access to research opportunities, multiple forms of stigma, and less knowledge of HIV and sexual health (28,32,34–39). Our work found that Latinx SMM report sexual orientation stigma, mental health stigma, and HIV-related stigma as barriers to participating in research, with undocumented Latinx sexual minority men experiencing additional immigration-related barriers to participation (40). In fact, the majority of HIV research among MSM has employed convenience sampling due to its methodological ease and low cost (41,42), suggesting HIV research focused on MSM may not be representative of the full SMM population (42).

To ensure the benefits of HlV-prevention and mental health clinical trials extend to all SMM, and in particular, SMM experiencing syndemic behavioral health concerns, it is important to identify factors associated with participation in such trials. Identifying these factors can facilitate equitable representation in these clinical trials, as well as access to the evidence-based HIV-prevention and mental health services that ultimately emerge from them. Although sexual minority people are more likely to utilize some health services, such as those focused on mental health (3,43–45) or HIV-prevention (46,47) compared to heterosexual people, access remains inequitable, especially for young SMM as well as Black and Latinx SMM (48,49). Accordingly, the purpose of this exploratory study is to identify factors associated with non-participation in an HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trial for young (age 18–35) SMM who report behavior that could lead to HIV acquisition and co-occurring mental health concerns. The findings of this study may facilitate the development of tailored recruitment strategies to engage eligible SMM who are least likely to participate in HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trials.

METHOD

Participants and Procedures

Participants (N = 633) in this study were young (age 18–35) SMM (i.e., identified as gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual identity) who completed a phone screen to determine their eligibility for the baseline assessment of a three-arm HTV-prevention and mental health clinical trial. The clinical trial from which these data were drawn sought to recruit 254 SMM across both sites in order to be powered to the primary trial outcome (i.e., incidence of condomless anal sex in the absence of pre-exposure prophylaxis/PrEP or known undetectable viral load of HIV-positive primary partners), therefore the sample size of this analysis represents the number of individuals determined to be eligible for the trial based on the phone screen.

The trial compared three conditions: (A) ESTEEM, or, “Effective Skills to Empower Effective Men,” (B) community-based LGBTQ-affirming mental health treatment, and (C) voluntary testing and counseling (VCT) only. Individuals randomized to ESTEEM received up to ten sessions of a brief, LGBTQ-affirming cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) designed to address the minority stressors hypothesized to contribute to behavioral and sexual health concerns that disproportionately affect young SMM. ESTEEM was delivered at the University-based research center where baseline and follow up assessments for the larger trial occurred (see Figure 1). Those randomized to community-based LGBTQ-affirming mental health treatment received up to ten sessions of therapy delivered by an existing community mental health treatment center that partnered with the study team for this project. Those randomized to VCT received a one-session intervention that involves testing for HIV and STIs and developing a personalized risk reduction plan with a counselor (50). Individuals randomized to ESTEEM and LGBTQ-affirmative community mental health treatment also received VCT before proceeding to mental health treatment, whereas those randomized to VCT did not receive further treatment. The study was conducted in New York City and Miami. Within each city, we had one study site where study visits, VCT, and ESTEEM took place. Community mental health treatment took place within one community partner organization within each city. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review board for each study site.

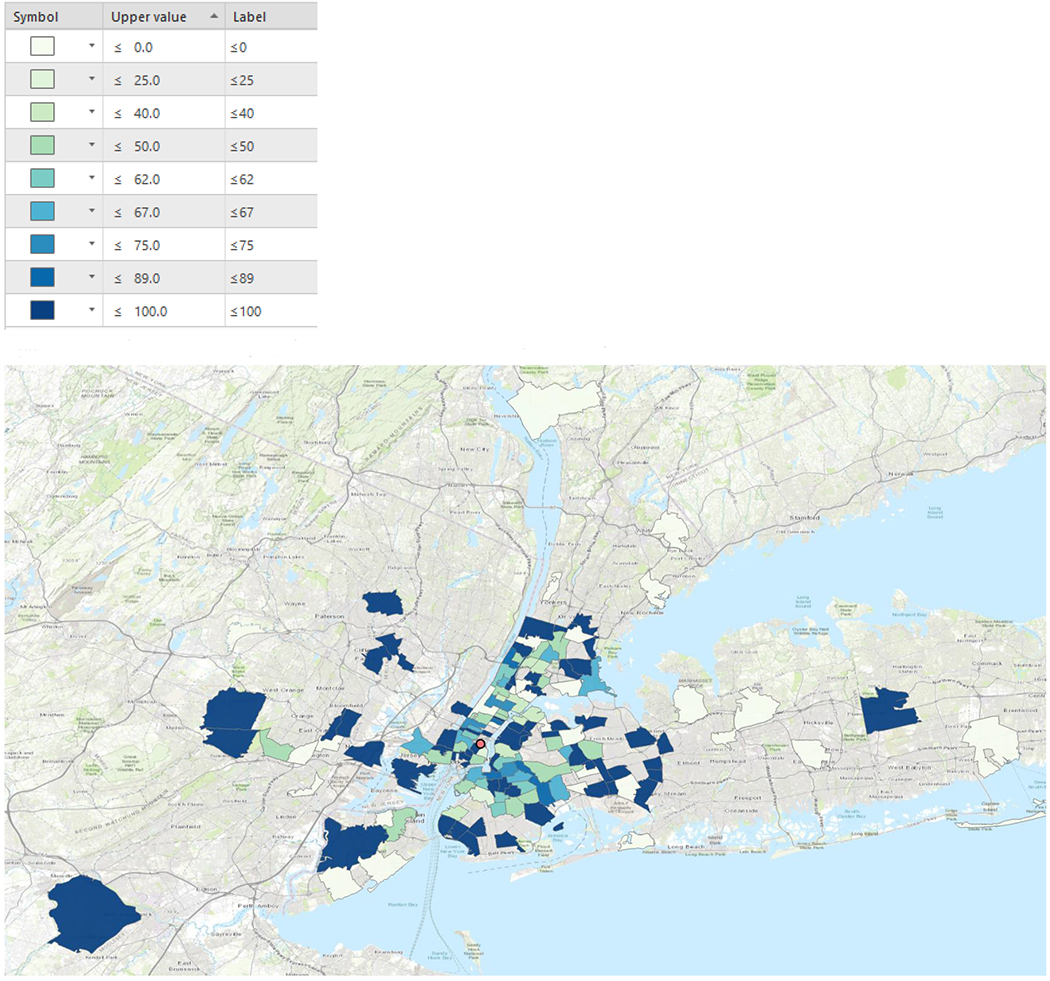

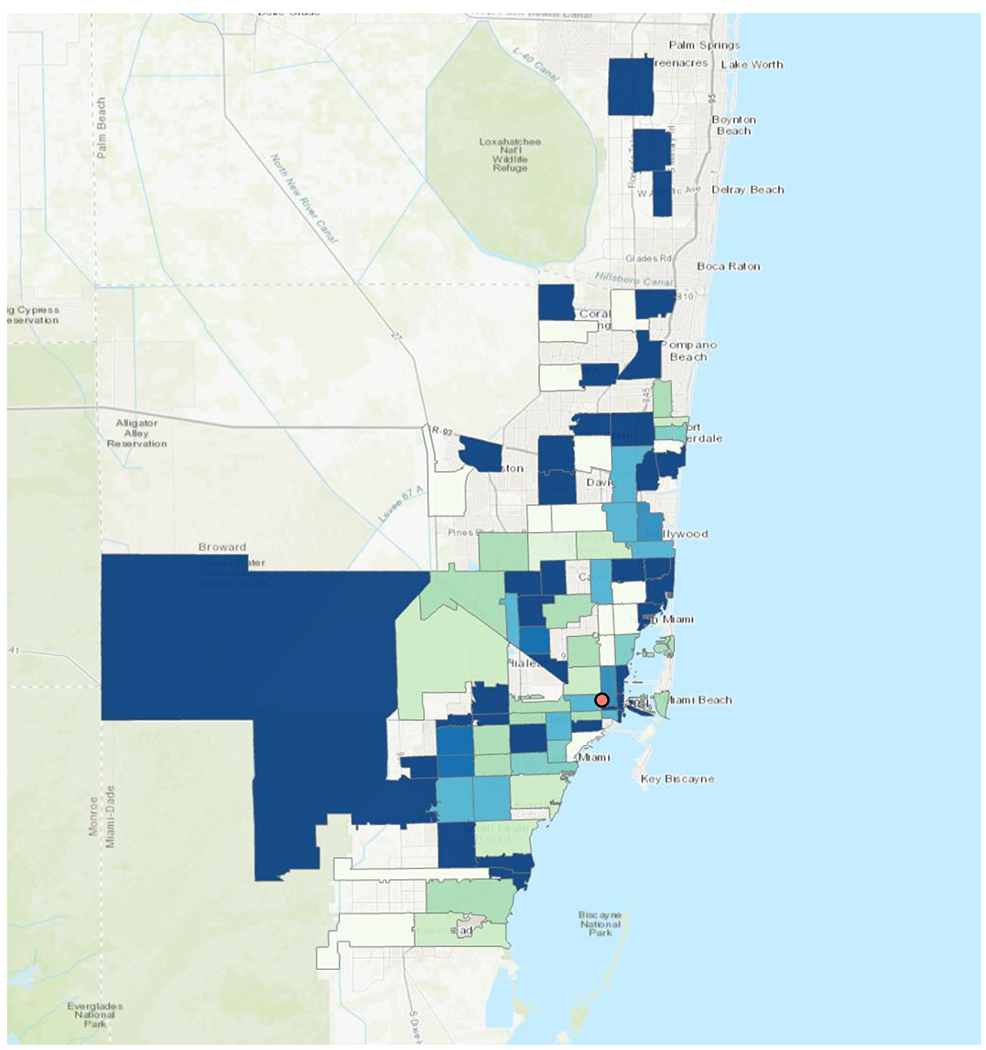

Figure 1.

Percentage of Participants who Participated vs. Did Not Participate by ZIP Code

*Note that the red dot in each map references the study site.

Participants were recruited into the study using a variety of methods. The team developed IRB-approved recruitment flyers, text, and images that were posted on social media (e.g., Facebook, Instagram) and in-person at venues such as community centers, public gathering spaces, bars/clubs, and other locations where young sexual minority men gather. Additionally, information about the study was shared with prospective participants via sexual networking apps, such as Grindr, Growler, and Scruff. Study staff also attended community events to share information about the study and recruit prospective participants. All recruitment methods involved prospective participants completing a brief survey and providing their contact information to complete a full phone-screening from the study staff to determine their eligibility for a baseline assessment.

Participants were eligible to complete a baseline eligibility assessment for the clinical trial based on their responses to the phone screen which assessed the following inclusion criteria: identified as a man (regardless of sex assigned at birth); identified as a sexual minority; aged 18–35 years; resided in the New York City or Miami area; indicated they were comfortable reading and verbally responding to questions about mental and sexual health in English; self-reported HIV-negative or unknown HIV status; were not currently adherent to PrEP; self-reported psychological distress exceeding an established threshold (2.5 initially, reduced to 1.5 in Miami site only); did not receive ongoing mental health treatment or 8 or more sessions of cognitive-behavioral therapy in the past 12 months; and self-reported sexual behavior that could lead to HIV acquisition (i.e., ≥1 act of condomless anal sex with a male partner of unknown HIV status or HIV-positive status in the past 90 days, unless with a HIV-positive main partner with a known undetectable viral load).

During the phone screen, trained study staff explained that the purpose of the trial was to evaluate interventions to improve the health and wellbeing of the LGBTQ community. Staff explained that the research team was comprised of LGBTQ-affirmative researchers. Study staff informed prospective participants that, if eligible on the phone screen, they would be scheduled for a series of two baseline assessments, which would involve asking about minority stress, behavioral health, and sexual health. Staff also informed prospective participants that they would take HIV, chlamydia, and gonorrhea tests and be given their results. They explained that participants who were eligible and agreed to participate would be randomly assigned to receive ten sessions of ESTEEM, ten sessions of LGBTQ-affirming community mental health treatment, or no further counseling and would be asked to complete follow-up assessments after four, eight, and 12 months and receive up to $350 for completing all study visits. Before proceeding to the phone screen, study staff explained that phone screen responses were confidential, and the information provided could be used to examine recruitment trends. Participants then provided verbal consent for the phone screen.

Measures

During the phone-screening to determine eligibility to complete a baseline assessment, prospective participants completed each of the following measures verbally.

Demographics.

For the purpose of the current study, we examined age (continuous), race/ethnicity (categorical, reference = non-Latinx white), and sexual orientation identity (binary, gay vs. other sexual minority identities) as possible predictors of study participation.

Psychological distress.

The abbreviated 4-item Brief Symptom Inventory (51) assessed participants’ symptoms of anxiety (nervousness and shakiness inside, feeling tense or keyed up) and depression (feeling blue, feelings of worthlessness) in the last three months. Participants rated each item from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The 4-item BSI has high specificity for detecting depressive or anxiety disorders, is highly related to the full BSI, and demonstrates equivalent reliability (51,52). Those with a mean score of 2.5 or higher for either the depression or anxiety items were eligible to continue with the study by completing a baseline assessment to determine their eligibility for the full trial. The threshold was reduced to 1.5 for the Miami site approximately halfway through the trial. This decision was made in response to clinician feedback we received that men in Miami may have been underreporting their mental health symptoms due to sociocultural pressure and/or mental health stigma in Miami. This adjustment increased the number of individuals who qualified for the baseline assessment. Despite this change, most still met criteria for a DSM diagnosis. As in prior research (53), we computed an overall composite score across all four items as an indicator of overall psychological distress from 0 (no distress) to 8 (extreme distress).

HIV status.

Participants self-reported their HIV status. Those who reported being HIV-negative or unsure of their HIV status were considered eligible for the baseline assessment to determine their eligibility for the full trial.

PrEP history.

Participants reported whether they had ever taken PrEP to reduce the likelihood of acquiring HIV and, of those reporting a PrEP history, how frequently they were currently taking PrEP. Those who reported currently taking PrEP four or more times per week were not eligible to participate in the current study, as this level of protection would substantially reduce the likelihood of HIV acquisition. For the purpose of the current study, we compared individuals who reported any PrEP history to those who reported no PrEP history (i.e., had never taken PrEP).

Study site.

We included study site (New York City or Miami) as a possible predictor of study participation and examined interaction effects for selected variables by study site.

Distance from study site.

Participants reported their residential ZIP code on the phone screen, which we used to compute an absolute distance in miles from the study site (New York City or Miami). As shown in Figure 1, each city in which the trial took place had one study site where research assessments took place. ArcGIS permits the creation of map-based data using geographic information. We used ArcGIS Pro 2.3 to compute absolute distance in miles from the geographic centroid of participants’ residential ZIP code and the study site (New York City or Miami). Although ArcGIS can compute driving or public transportation distance, the absolute distance was considered the most accurate estimate of distance because we did not have a specific address for each participant.

Community HIV prevalence.

We matched publicly available HIV prevalence data to participants’ residential ZIP codes to determine community HIV prevalence. Prevalence (from 2017) for ZIP codes in New York (Kings, Queens, New York, and Bronx counties) and Florida (Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties) and were downloaded from AIDSVu (54), an online mapping tool that reports HIV prevalence across the United States. Some participants indicated a residential ZIP code outside of New York City, Miami-Dade County, Broward County, and Palm Beach County, which were not available from AIDSVu (n = 32). Prevalence data for ZIP codes not accessible through AIDSVu were gathered through two additional sources – Statimetric, whose data is based on the CDC’s National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention AtlasPlus statistics (55) and reports from the New Jersey Department of Health (56). Prevalence data are reported as the number of people living with HIV per 100,000.

Study non-participation.

The main outcome of the current analysis was study non-participation (i.e., whether individuals chose to complete a baseline assessment after screening into the study by phone). Those who screened as eligible on the phone screen and then declined a baseline assessment or scheduled a baseline assessment but never completed it (e.g., no shows/cancellations that were not rescheduled) were considered “non-participators.” Individuals were coded as “participators” if they scheduled and attended their baseline assessment.

Data Analysis

The purpose of this study was to identify factors that were related to whether young SMM who were eligible, based on their phone screen responses, ultimately participated in a baseline assessment for the clinical trial. Two modeling strategies were used: logistic regression, which focuses on how individual predictors and their interactions increase or decrease the chance of the outcome, and additionally, classification and regression trees (CART), a machine learning method which uses predictors to build groups of individuals with similar chances of the outcome (57), in this case, “participating” or “not participating.”

For the logistic regression modeling, we conducted a series of bivariate logistic regression analyses to identify which of our independent variables were individually associated with study participation. Independent variables with a p-value of .20 or less were considered for inclusion in the multivariate logistic regression model. Those involved in the bivariate interactions were left in the final model, even if they were not significant using the traditional p-value of .05 or less. Finally, we explored interaction effects by study site to explore whether any bivariate predictors with a p-value of .20 or less were related to the study outcome within one study site but not the other. Because in Miami, but not New York City, we decreased the cutoff score for psychological distress necessary to participate in a baseline assessment, we introduced greater variability in distress scores only in the Miami site. Therefore, distress was included only as a control variable to control for the differential variability across the two sites. For the same reason, a distress-by-study-site interaction term was included in the final model. Finally, we examined the relationship between distress and study participation within the Miami site only, as there was greater variability in distress scores within Miami. These models and descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS version 26.

We also used CART (57), which uses an algorithm to repeatedly split the dataset into subgroups that were either majority participators or non-participators. These splits can be thought of as “rules” for predicting the likelihood that individuals will participate. CART models start by examining every binary variable, as well as every possible cut point for each continuous variable, to determine which variables (i.e., binary variables or cut points for continuous variables) create the most homogenous set of participators and non-participators. For example, for the continuous variable of “age,” the CART model first determined if the group of men aged 18 vs. 19+ were similar in their outcome, followed by men aged 18–19 vs. 20+, and so on for each cut point. CART repeated this process using every potential variable to determine if making another binary split in the dataset created additional homogenous groups. CART continued making splits until groups were homogenous in terms of the outcome variable (study participation). CART model “trees” (the visual model that shows all splits) require “pruning” to make them interpretable. Here, we used five-fold cross-validation (i.e., splitting the data into fifths) to determine the amount of pruning. That is, the algorithm built a model using 80% of the data and checked the classification accuracy (i.e., the percent of records correctly classified) and kappa statistics (i.e., classification accuracy normalized to account for the rarity of the outcomes) of that model when it was applied to the remaining 20% of the data. Then, the first 20% was added back into the 80%, and the second 20% was removed, following the same process until each fifth of the data was used. The pruning parameter yielding the model with the highest accuracy and best kappa in the cross-validation was then applied to the dataset to determine the final model. Here, CART modeling was completed using the rpart package (version 4.1-15) with cross-validation completed using the cart package (6.0-86) in R 3.6.2.

RESULTS

Demographics

Table 1 contains complete participant demographics for all participants, and by site: New York (N = 402) and Miami (N = 231). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 35 years old (M = 26.58, SD = 4.30). Most participants identified as gay (n = 488, 77.1%) and a racial/ethnic minority (n = 471, 74.4%). The Miami site had a greater proportion of Latinx participants (60.6%) than the New York City site (38.6%), χ2(1) = 28.66, p < 0.001. Few participants were unsure of their HIV status (n = 67, 10.6%), however this was more common in Miami than New York, χ2(1) = 5.27, p = 0.022. Similarly, most had not taken PrEP (n = 524, 82.8%), but Miami participants were less likely to have taken PrEP in the past compared to those in New York, χ2(1) = 7.81, p = 0.005. Participants’ average psychological distress was 5.36 (SD = 1.26), indicating moderate to high levels of anxiety/depression. As expected due to the lowering of inclusion based on distress scores in Miami, average distress scores in Miami were lower compared to New York, t(396) = −5.62, p < 0.001. Participants lived an average of 10.52 miles (SD = 8.80) from the study site, with average residential distance from the study site 5.8 miles further in Miami compared to New York, t(338) = 7.53, p < 0.001. More than one-third were classified as “non-participators” (n = 239, 37.8%).

Table I.

Descriptive statistics of study sample.

| Total (N = 633) |

Miami (N = 231) |

New York (N = 402) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Age (years) | 26.58 | 4.30 | 26.26 | 4.66 | 26.77 | 4.08 | −1.40 |

| Distance (miles) | 10.52 | 8.80 | 14.24 | 10.49 | 8.40 | 6.84 | 7.53*** |

| HIV Prevalence by ZIP Code (per 100,000) | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0.02 | 0.019 | 0.013 | −1.09 |

| Psychological Distress | 5.36 | 1.26 | 4.98 | 1.40 | 5.58 | 1.11 | −5.62*** |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | |

| Ethnicity | 28.66*** | ||||||

| Latinx | 295 | 46.6 | 140 | 60.6 | 155 | 38.6 | |

| Non-Latinx | 338 | 53.4 | 91 | 39.4 | 247 | 61.4 | |

| Race | 18.53** | ||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 7 | 1.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.7 | |

| Asian | 27 | 4.3 | 3 | 1.3 | 24 | 6.0 | |

| Black/African American | 131 | 20.7 | 45 | 19.5 | 86 | 21.4 | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| White | 284 | 44.9 | 120 | 51.9 | 164 | 40.8 | |

| Multiracial | 64 | 10.1 | 20 | 8.7 | 44 | 10.9 | |

| Other | 10 | 1.6 | 4 | 1.7 | 6 | 1.5 | |

| Unknown | 109 | 17.2 | 38 | 16.5 | 71 | 17.7 | |

| Self-Reported HIV Status | 5.27* | ||||||

| Negative | 566 | 89.4 | 198 | 85.7 | 368 | 91.5 | |

| Unknown | 67 | 10.6 | 33 | 14.3 | 34 | 8.5 | |

| PrEP History | 7.81** | ||||||

| Yes | 109 | 17.2 | 27 | 11.7 | 82 | 20.4 | |

| No | 524 | 82.8 | 204 | 88.3 | 320 | 79.6 | |

| Sexual Orientation | 2.52 | ||||||

| Gay | 488 | 77.1 | 170 | 73.6 | 318 | 79.1 | |

| Other Sexual Minority Identity | 145 | 22.9 | 61 | 26.4 | 84 | 20.9 | |

| Study Participation | 0.09 | ||||||

| Yes | 394 | 62.2 | 142 | 61.5 | 252 | 62.7 | |

| No | 239 | 37.8 | 89 | 38.5 | 150 | 37.3 | |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

Logistic Regression Model

Bivariate Relationships – Preliminary Analyses.

As shown in Table 2, self-reported HIV status was significantly associated with study non-participation, such that those who reported having an unknown HIV status were 2.22 times more likely not to participate in the trial (95% CI: 1.33, 3.70) compared to those who reported an HIV-negative status. None of the other independent variables were significantly associated with study participation. Of note, distance from the study site was not related to study participation; this is highlighted in Figure 1, which shows that study participators were geographically dispersed for both sites. Psychological distress, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation were not significant predictors, but their p-values were < 0.20; therefore, these variables were retained for the multivariate model. We also retained the study site in the multivariate model to facilitate planned interaction analyses by site.

Table II.

Predictors of study non-participation (BL1)

| OR (95%) | AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main Effects | |||

| Age (year) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.02) | — | — |

| Distance (miles) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | — | — |

| Community HIV Prevalence | 19.28 (0.01, >500) | — | — |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Latinx | 1.32 (0.88, 1.96)+ | 1.33 (0.88, 2.02)+ | 1.80 (1.10, 2.95)* |

| Blacka | 1.03 (0.62, 1.71) | 1.01 (0.60, 1.71) | 1.01 (0.54, 1.92) |

| Another race/ethnicitya | 1.03 (0.57, 1.87) | 1.09 (0.60, 2.00) | 0.92 (0.45, 1.88) |

| Whitea (ref) | — | — | — |

| HIV Status (NEG vs. UNK) ref: HIV-Negative | 2.22 (1.33, 3.70)** | 2.21 (1.31, 3.72)** | 2.39 (1.41, 4.04)** |

| PrEP History (Yes vs. No) ref: Yes | 0.84 (0.55, 1.27) | — | — |

| Psych.Distress | 0.91 (0.80, 1.04)+ | 0.92 (0.81, 1.06) | 1.05 (0.87, 1.27) |

| Sex. Ori. (Gay vs. OSM) ref: Gay | 0.77 (0.52, 1.14)+ | 0.69 (0.46, 1.03)+ | 0.64 (0.38, 1.09)+ |

| Study Site (NYC vs. Miami) ref: NYC | 1.05 (0.76, 1.47) | 0.88 (0.62, 1.27) | 6.40 (1.26, 32.51)* |

| Interaction Effects | |||

| Study Site X Psych. Distress | — | — | 0.73 (0.56, 0.96)* |

| Miami | — | — | 0.77 (0.64, 0.94)* |

| NYC | — | — | 1.06 (0.88, 1.28) |

| Study Site X Race/Ethnicity | — | — | Wald χ2(3) = 8.29* |

| Miami | |||

| Latinx | — | — | 0.81 (0.37, 1.77) |

| Blacka | — | — | 1.08 (0.42, 2.81) |

| Another race/ethnicitya | — | — | 1.62 (0.49, 5.34) |

| Whitea (ref) | — | — | — |

| New York | |||

| Latinx | — | — | 1.81 (1.09, 2.98)* |

| Blacka | — | — | 1.01 (0.53, 1.93) |

| Another race/ethnicitya | — | — | 0.93 (0.45, 1.91) |

| Whitea (ref) | — | — | — |

| Study Site X Sex. Ori. | — | — | 1.21 (0.53, 2.76) |

Note:

denotes non-Latinx ethnicity; OR, odds ratio from bivariate logistic regression; AOR, adjusted odds ratio from the multivariate logistic regression model and controlling for site; Interactions, adding in interactions terms; NEG, negative; UNK, unknown; OSM, other sexual minority; Psych. Distress, psychological distress; Sex. Ori., sexual orientation;

p < .20 (included in multivariate model)

p < .05,

p < .01.

Multivariate Model.

In the multivariate model, HIV status remained a significant predictor of study non-participation (OR = 2.21, 95% CI [1.31, 3.72], p = 0.003), with those who were unsure of their HIV status substantially more likely not to participate, despite being eligible. The other predictors (i.e., psychological distress, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and study site) remained non-significant.

Interaction Effects.

We then added interaction effects by study site for all predictors that trended toward, but did not reach, significance in the bivariate models: race/ethnicity and sexual orientation. We also retained a study-site-by-psychological-distress interaction term as a control.

First, we found that race/ethnicity was differentially associated with study participation in New York City versus Miami, Wald χ2(3) = 8.29, p = 0.04. Within New York City, participants who identified as Latinx were significantly more likely to be non-participators than those who identified as non-Latinx White (OR = 1.81, 95% CI [1.09, 2.98], p = 0.021), whereas in Miami, there was no difference in Latinx SIMM’s odds of participation, compared to non-Latinx White SMM (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.37, 1.77], p = 0.596). No other racial/ethnic differences in participation were observed within each study site.

In contrast, we did not find a significant interaction between sexual orientation identity and study site (OR = 1.21, 95% CI [0.53, 2.76], p = 0.661). In both New York City and Miami, there was no significant difference in the likelihood of SMM who identified as gay compared to those who identified with another sexual minority identity (e.g., bisexual, queer) in terms of study participation.

Finally, we examined the association between psychological distress and study participation in the Miami site, as within Miami there was greater variability in distress scores based on the study design. We found that in Miami, individuals with greater psychological distress were significantly more likely to participate in the trial (OR = 0.77, 95% CI [0.64, 0.94], p = 0.011).

Overall, this multivariate model, including the specified interactions, had better discriminative power than chance to predict which of two prospective participants who would ultimately be a participator vs. non-participator (c = 0.62; note that c = 1.00 would constitute perfect classification; 53), with the model having an accuracy (proportion of cases that are correctly identified) of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.60, 0.68).

CART Model

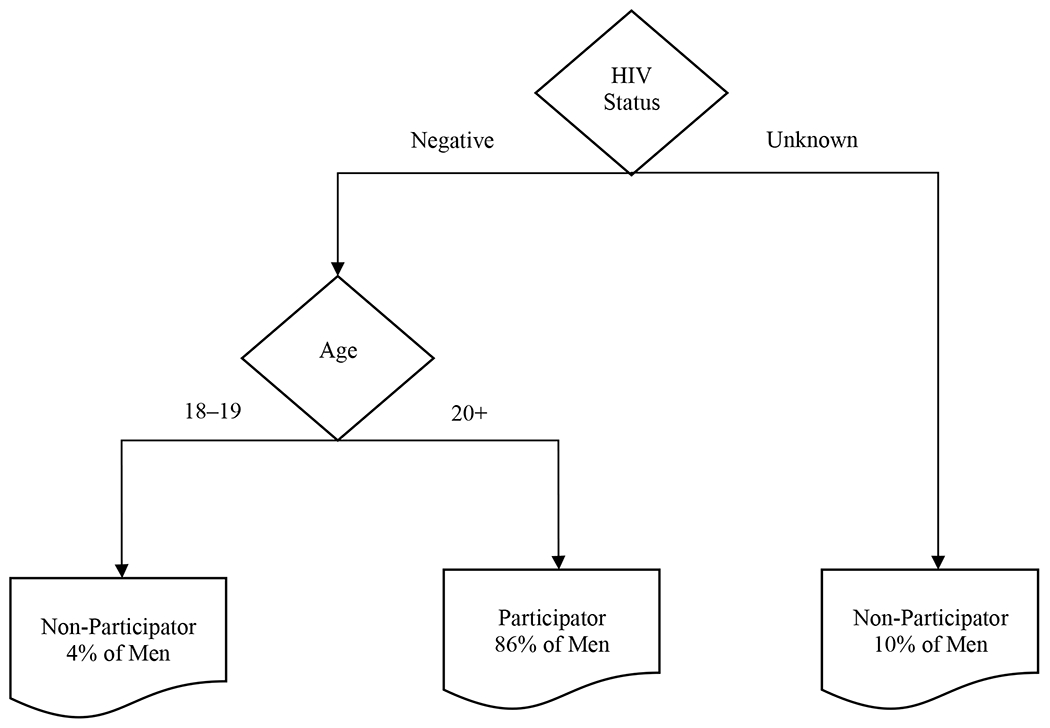

Before pruning, CART suggested an extremely “bushy” classification tree with 14 splits based on HIV status, age, HIV prevalence, psychological distress, and study site. Five-fold cross-validation using accuracy or kappa suggested a pruning parameter (i.e., cp; ,59) of approximately 0.019. Applying that stringent pruning reduced the tree to only two splits. As can be seen in Figure 2, the three groups formed by these splits are: (1) men whose HIV status was unknown (10% of the total sample) and were mostly non-participators; (2) men who were at least 20 years old and reported being HIV-negative (86% of the sample) and were mostly participators; and (3) teenagers (18-19 years) who reported being HIV-negative (4% of the sample) and were mostly non-participators. The overall performance of this model was comparable to that of the logistic model, with an accuracy of 0.64 (95% CI: 0.60, 0.68).

Figure 2.

CART Model

DISCUSSION

This study found that, within this group of young SMM with mental health concerns, those who did not know their HIV status were less likely to participate in a clinical trial focused on addressing behavioral and sexual health. This is a significant finding because theoretically, this population is likely to have a greater likelihood of acquiring or transmitting HIV, given uncertainty about their current HIV status and co-occurring mental health concerns, yet were least likely to engage in a clinical trial that could address those behaviors that may pose a risk for acquiring HIV. Furthermore, among those who reported being HIV-negative, SMM ages 18-19 were less likely to participate in the trial than SMM ages 20–35. In addition, we identified notable site-specific findings. In New York City, individuals who identified as Latinx were less likely to participate than those who were non-Latinx, whereas this pattern was not observed in Miami, nor were any other racial/ethnic differences observed. Finally, psychological distress was associated with participation within the Miami site.

The current findings support and expand prior research findings. Although several studies have demonstrated that race/ethnicity, age, and engaging in behavior that could lead to HIV acquisition are predictors of MSM’s participation in HIV vaccine trials, most of these studies examined “willingness” to participate, not actual participation (29–31,60). Other studies have found that factors such as not knowing one’s HIV status are associated with MSM’s engagement in HIV-prevention programs (61). The current findings add to prior work by highlighting these previously observed relationships in the context of a different type of clinical trial, one focused on young SMM’s behavioral and sexual health. The current trial is also tailored to a different population than prior research; it only included young SMM with co-occurring behavioral health concerns, and therefore may have unique needs and motivations for participating in an HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trial. The findings help to inform recruitment strategies that could help to ensure equitable representation of SMM who are diverse with respect to HIV status, age, ethnicity, and mental health needs, as described below.

The current study suggests that, among young SMM with co-occurring mental health concerns, individuals who did not know their current HIV status were less likely than those who reported being HIV-negative to participate in a trial that sought to address both sexual health and the syndemic mental health concerns that can lead to HIV acquisition. Furthermore, we observed that SMM in Miami were more likely than those in New York to not know their current HIV status at the time of the phone screen. These findings suggest the potential utility of recruitment messages emphasizing the direct benefits of participating in an HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trial, with potential benefits including receiving free HIV testing, meeting with an LGBTQ-affirming HIV testing counselor to discuss their sexual health in a sex-positive manner, and having the opportunity to reflect on one’s own sexual health goals. SMM often cite fear of testing positive as a barrier for HIV testing (62,63). Therefore, it may be helpful to alter recruitment language to reduce the emphasis on risk and, instead, focus on benefits of engaging in an HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trial (e.g., linkage to affirming care regardless of test results) to ensure that individuals who are unsure of their status, and theoretically at the greatest risk of having HIV and not knowing it, are engaged in the trial. This is consistent with established public health approaches of using “gain-framed” (emphasizing the benefits of a health behavior) versus “loss-framed” (emphasizing the costs of not engaging in a health behavior) messaging. Prior studies have shown that individuals were more willing to participate in HIV-related research and mental health services when provided “gain-framed” messaging about the study (64,65), a potentially useful strategy to use when developing inclusive recruitment campaigns.

Our finding that teenage SMM were less likely than SMM ages 20–35 to be non-participators suggests another population that may benefit from tailored recruitment strategies. It is possible that by age 20, SMM have reached a level of independence that allows them to feel more comfortable engaging in a HIV-prevention and LGBTQ mental health focused research study and less worried about the potential concerns associated with family or friends finding out about their participation. A Pew Research Center (66) poll showed that, among LGB adults in the US, the median age of sexual orientation disclosure is 20, supporting the notion that at this age, SMM may have felt more comfortable participating in a study that could identify their sexual orientation identity. According to the most recent Center for Disease Prevention and Control HIV surveillance report, HIV incidence remained stable for MSM aged 13-24 years and increased for MSM aged 25-34 (2). Racial/ethnic HIV disparities among MSM emerge early, with only 3% of 18- to 24-year-old White MSM diagnosed with HIV, followed by 9% of Latinx MSM, and 26% of Black MSM (67). The evidence regarding the efficacy of HIV/STI-prevention interventions among young SMM is mixed (68–70); therefore, future research should continue to engage younger SMM in clinical trials to ensure findings are applicable to younger SMM, who are developmentally situated to receive a preventive intervention. Additionally, engaging younger SMM may help to address the racial and ethnic HIV disparities that emerge early in the SMM population. Lucassen and colleagues’ (71) qualitative work with sexual minority adolescents yielded suggestions for engaging sexual minority youth in research. For instance, they recommended creating a comfortable environment for sexual minority youth to participate (e.g., confidential, building a personal relationship), recruiting actively (vs. passively) through academic and social settings, being aware of unique barriers for sexual minority youth (e.g., navigating participation if not “out” to family), and leveraging altruistic motives for participating in research. By tailoring interventions to the needs of younger SMM, researchers may be able to capitalize on early HIV-prevention programs among a population in increasing need for tailored support.

We found that in New York City, but not in Miami, Latinx SMM were less likely to participate in the trial compared to non-Latinx White SMM. In the Miami site, we initially had difficulty with overall recruitment. Despite using the same recruitment strategies as the New York City site (e.g., Grindr shouts, flyers), the Miami site did not receive as many interested prospective participants. Therefore, the Miami site modified their recruitment strategies to ensure it reached young SMM in Miami, a population primarily comprised of Latinx SMM. This involved tailored recruitment such as creating culturally congruent outreach materials that reduced the emphasis on “mental health,” and psychological symptoms/treatment (e.g., “Stressed? Nervous? Blue? Low Self-Esteem? Participate in an investigative mental health treatment designed by and for the gay community”), which is often stigmatized among Latinx families (72,73) and instead focused on “wellness” (e.g., “Looking? So are we. Participate in a sexual health and wellness study – you may receive free counseling.”). We also transitioned from a focus on LGBTQ imagery (e.g., pride flags) to images of racially and ethnically diverse men in familiar social and sexual contexts (e.g., at the beach, with groups of friends, drinking coffee, in bed together). The Miami site hired a full-time outreach specialist who substantially increased community-engaged recruitment efforts, developing regular social events at local venues that serve the young SMM community in Miami and becoming an active presence at other LGBTQ community events. After these efforts were employed, the Miami site saw improved participation. It is possible that these tailored recruitment efforts could be useful in other contexts. Relatedly, other overall study modifications, such as hiring Spanish-speaking staff and making recruitment materials available in Spanish, could further facilitate equitable representation of Latinx SMM. In the context of the current study, however, participation was limited to individuals who were comfortable conversing in English, potentially limiting the participation of Latinx SMM. Our qualitative work also highlights the utility of using relational strategies, such as peer-based outreach, emphasizing altruism, emphasizing confidentiality and building trust, destigmatizing HIV and behavioral health, and maintaining a stance of personalismo and affirmation to promote participation of Latinx SMM (40).

Despite the difference in Latinx SMM’s participation in the trial within New York City, we did not find any other overall or site-specific differences in study participation based on race/ethnicity. For example, Black SMM, another subgroup of SMM disproportionately impacted by HIV in the US, were equally likely to be “participators” in the trial compared to non-Latinx White SMM. Within this trial, approximately 20% of prospective participants identified as Black, which is reflective of the overall demographics of New York and Miami, where 24.3% and 17.7% of the population identifies as Black, respectively (74). However, Black SMM are disproportionately impacted by HIV, with 37% of new HIV diagnoses among SMM occurring among Black SMM (75). As such, enhanced recruitment strategies may be needed to engage Black SMM in the initial phone screen, to adequately reflect the proportion of Black SMM who are affected by the HIV epidemic in the US. To reach both Latinx and Black SMM, community-based participatory research may be a particularly effective method for developing tailored recruitment and retention strategies through understanding factors that may facilitate and impede participation for these two subpopulations of SMM (76,77). Within the Miami site, we observed an association between psychological distress and study participation, such that those with greater distress were more likely to participate. We speculate that the association between distress and participation in Miami could pertain to the inaccessibility of mental health services outside the context of our study. Anecdotally, many participants reported that one motivator for participating in the study was the potential for receiving mental health treatment, which they felt was difficult to access within the community. In fact, in a subsequent qualitative study, “participator” and “non-participator” Latinx SMM cited the direct benefits that they anticipated receiving as a motivating factor for their trial participation (40). As such, it is possible that those who anticipated deriving greater benefit (i.e., those who were most distressed) may have been more motivated to participate in the trial. With this reasoning, it may be helpful to continue emphasizing or describe in greater detail the direct benefits of HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trials to participants to facilitate participation.

Our non-significant findings may also have implications for recruiting young SMM into HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trials. For example, we found that distance from the study site did not make a difference in whether SMM ultimately participated. Although there may be some participants for whom longer travel distance is a barrier to participation, among the overall sample, this was not a consistent pattern. As such, it may be advisable for researchers to consider recruiting in broad geographic areas rather than focusing solely on geographic areas with larger LGBTQ populations.

Despite the strengths of this study, there were also limitations. For example, we were only able to include a limited number of questions on the phone screen, as it was designed to be brief and only assess those factors relevant to the eligibility criteria for the trial. As such, we were not able to assess a variety of other factors that may be associated with research engagement, such as socioeconomic status, employment status, access to public transportation, and others. Additionally, participants who were not able to communicate in English were screened out of the study due to limitations in bilingual staff availability; therefore, this study does not capture individuals who were non-English speaking. As noted above, we changed the threshold for inclusion in a baseline assessment of full study eligibility based on responses to the BSI such that it was lowered in Miami, but not in New York City, approximately halfway through the study. This precludes interpreting the interaction effect between sites on psychological distress to suggest that there were differences in the relationship between psychological distress and study participation between sites. Instead, we examined the relationship within the Miami site only and found a significant association between distress and research participation; future research is needed to determine the unique or common functionality of psychological distress in different settings. Finally, this study was conducted in two urban US centers with young SMM, therefore, generalizability of the findings may be limited, and future research is warranted within non-urban settings and with SMM across the lifespan. Further research is also needed to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of different recruitment approaches for engaging subpopulations of SMM in HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trials. These findings suggest avenues for beginning to develop these tailored recruitment approaches to increase equitable representation in clinical trials and, ultimately, in SMM’s HIV and mental health prevalence.

Conclusion

This study identified factors that were associated with non-participation in an HIV-prevention and mental health clinical trial for young SMM, including not knowing one’s HIV status, being a teenager (age 18-19), identifying as Latinx (in New York City), and reporting less psychological distress (in Miami). These factors may be leveraged to develop tailored outreach strategies to facilitate equitable representation of young SMM in trials that will determine evidence-based practice for this population.

Acknowledgements:

Data collection for this study was supported by R01MH109413 (Pachankis). Additional support came from P30MH116867 and K24DA040489 (Safren) and K23MD015690 (Harkness). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Funding: Data collection for this study was supported by R01MH109413 (Pachankis). Additional support came from P30MH116867 and K24DA040489 (Safren) and K23MD015690 (Harkness).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests:

Dr. Pachankis receives royalties from Oxford University Press for books related to LGBTQ-affirmative mental health treatments. Dr. Safren receives royalties from Oxford University Press, Guilford Publications, and Springer/Humana press for books on cognitive behavioral therapy. The authors have no other relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Yale University and University of Miami.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

We use the term “sexual minority men” to refer to men who identify as gay, bisexual, or another non-heterosexual identity. Some sources referenced use the term “men who have sex with men” (MSM) to refer to men who engage in sexual behavior with men, regardless of their sexual orientation identity; therefore, we use the term MSM to describe these groups, consistent with the cited research.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States 2010–2016 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-24-1.pdf

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2014–2018 [Internet]. 2020. Report No.: 25. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-supplemental-report-vol-25-1.pdf?deliveryName=FCP_2_USCDCNPIN_162-DM27706&deliveryName=USCDC_1046-DM27774

- 3.Cochran SD, Sullivan JG, Mays VM. Prevalence of mental disorders, psychological distress, and mental health services use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003. February;71(1):53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King M, Semiyen J, Tai SS, Killaspy H, Osborn D, Popelyuk D, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry [Internet]. 2008. December [cited 2019 Jan 11];8(1). Available from: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshal MP, Dietz LJ, Friedman MS, Stall R, Smith HA, McGinley J, et al. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: A meta-analytic review. J Adolesc Health. 2011. August;49(2):115–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bränström R, Hatzenbuehler ME, Pachankis JE. Sexual orientation disparities in physical health: Age and gender effects in a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016. February;51(2):289–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice CE, Vasilenko SA, Fish JN, Lanza ST. Sexual minority health disparities: An examination of age-related trends across adulthood in a national cross-sectional sample. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;39:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Institute of Medicine. The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding [Internet]. 2011. [cited 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/13128/the-health-of-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-people-building [PubMed]

- 9.Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. PEDIATRICS. 2009. January 1;123(1):346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pachankis JE, Cochran SD, Mays VM. The mental health of sexual minority adults in and out of the closet: A population-based study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(5):890–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ragins BR, Singh R, Cornwell JM. Making the invisible visible: Fear and disclosure of sexual orientation at work. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92(4):1103–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Gamarel KE, Bryant KJ, Zaller ND, Operario D. Discrimination, mental health, and substance use disorders among sexual minority populations. LGBT Health. 2016. July 6;3(4):258–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCabe SE, Bostwick WB, Hughes TL, West BT, Boyd CJ. The relationship between discrimination and substance use disorders among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2010. October;100(10):1946–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer IH, Frost DM. Minority stress and the health of sexual minorities. In: Patterson CJ, D’Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation [Internet], Oxford University Press; 2012. [cited 2019 Jan 11], p. 252–66. Available from: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199765218.001.0001/acprof-9780199765218-chapter-18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dyer TP, Shoptaw S, Guadamuz TE, Plankey M, Kao U, Ostrow D, et al. Application of syndemic theory to Black men who have sex with men in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. J Urban Health. 2012. August 1;89(4):697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferlatte O, Hottes TS, Trussler T, Marchand R. Evidence of a syndemic among young Canadian gay and bisexual men: Uncovering the associations between anti-gay experiences, psychosocial issues, and HIV risk. AIDS Behav. 2014. July;18(7):1256–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mimiaga MJ, Biello KB, Robertson AM, Oldenburg CE, Rosenberger JG, O’Cleirigh C, et al. High prevalence of multiple syndemic conditions associated with sexual risk behavior and HIV infection among a large sample of Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking men who have sex with men in Latin America. Arch Sex Behav. 2015. October 1;44(7):1869–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, Donenberg G. Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Ann Behav Med. 2007. August 1;34(1):37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):156–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parsons JT, Millar BM, Moody RL, Starks TJ, Rendina HJ, Grov C. Syndemic conditions and HIV transmission risk behavior among HIV-negative gay and bisexual men in a U.S. national sample. Health Psychol. 2017. July;36(7):695–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2003. June 1;93(6):939–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, et al. Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med. 2006. October;63(8):2010–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer MC, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: reconceptualizing disease in bio-social context. Med Anthropol Q. 2003. December;17(4):423–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fitzpatrick LK, Sutton M, Greenberg AE. Toward eliminating health disparities in HIV/AIDS: The importance of the minority investigator in addressing scientific gaps in Black and Latino communities. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006. December;98(12):1906–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellard-Gray A, Jeffrey NK, Choubak M, Crann SE. Finding the hidden participant: solutions for recruiting hidden, hard-to-reach, and vulnerable populations. Int J Qual Methods. 2015. December 9;14(5):160940691562142. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernández MI, Warren JC, Varga LM, Prado G, Hernandez N, Bowen GS. Cruising in cyber space: Comparing Internet chat room versus community venues for recruiting Hispanic men who have sex with men to participate in prevention studies. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2007. December 17;6(2):143–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holloway IW, Cederbaum JA, Ajayi A, Shoptaw S. Where are the young men in HIV prevention efforts? Comments on HIV prevention programs and research from young men who sex with men in Los Angeles County. J Prim Prev. 2012. December;33(5–6):271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson S, Seekaew P, Koblin B, Vazquez T, Nandi V, Tieu H-V. Barriers and facilitators of HIV vaccine and prevention study participation among Young Black MSM and transwomen in New York City. Consolaro MEL, editor. PLOS ONE. 2017. July 19;12(7):e0181702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnold MP, Andrasik M, Landers S, Karuna S, Mimiaga MJ, Wakefield S, et al. Sources of racial/ethnic differences in awareness of HIV vaccine trials. Am J Public Health. 2014. June 12;104(8):e112–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connochie D, Tingler RC, Bauermeister JA. Young men who have sex with men’s awareness, acceptability, and willingness to participate in HIV vaccine trials: Results from a nationwide online pilot study. Vaccine. 2019. October 8;37(43):6494–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castillo-Mancilla JR, Cohn SE, Krishnan S, Cespedes M, Floris-Moore M, Schulte G, et al. Minorities remain underrepresented in HIV/AIDS research despite access to clinical trials. HIV Clin Trials. 2014. February;15(1):14–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sullivan PS, McNaghten AD, Begley E, Hutchinson A, Cargill VA. Enrollment of racial/ethnic minorities and women with HIV in clinical research studies of HIV medicines. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007. March;99(3):242–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrasik MP, Chandler C, Powell B, Humes D, Wakefield S, Kripke K, et al. Bridging the divide: HIV prevention research and Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2014. April;104(4):708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014. February;104(2):e16–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grov C, Cain D, Whitfield THF, Rendina HJ, Pawson M, Ventuneac A, et al. Recruiting a US national sample of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men to complete at-home self-administered FHV/STI testing and surveys: Challenges and opportunities. Sex Res Soc Policy. 2016. March;13(1):1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoyt MA, Rubin LR, Nemeroff CJ, Lee J, Huebner DM, Proeschold-Bell RJ. HIV/AIDS-related institutional mistrust among multiethnic men who have sex with men: Effects on HIV testing and risk behaviors. Health Psychol. 2012;31(3):269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez O, Wu E, Shultz AZ, Capote J, López Rios J, Sandfort T, et al. Still a hard-to-reach population? Using social media to recruit Latino gay couples for an HIV intervention adaptation study. J Med Internet Res. 2014. April 24;16(4):e113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Westergaard RP, Beach MC, Saha S, Jacobs EA. Racial/ethnic differences in trust in health care: HIV conspiracy beliefs and vaccine research participation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014. January;29(1):140–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harkness A, Rogers BG, Mayo D, Smith-Alvarez R, Pachankis JE, Safren SA. “People naturally want to be part of something that’s bigger than themselves:” A relational framework for engaging Latino sexual minority men in research. Manuscript Under Review [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhalla S, Poole G. Effect of race/ethnicity on participation in HIV vaccine trials and comparison to other trials of biomedical prevention. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2014. July 7;10(7):1974–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo Y, Li X, Fang X, Lin X, Song Y, Jiang S, et al. A comparison of four sampling methods among men having sex with men in China: implications for HIV/STD surveillance and prevention. AIDS Care. 2011. November;23(11):1400–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Balsam KF, Beauchaine TP, Mickey RM, Rothblum ED. Mental health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings: effects of gender, sexual orientation, and family. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114(3):471–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kerr DL, Santurri L, Peters P. A comparison of lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual college undergraduate women on selected mental health issues. J Am Coll Health. 2013. May;61 (4):185–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Platt LF, Wolf JK, Scheitle CP. Patterns of mental health care utilization among sexual orientation minority groups. J Homosex. 2018. January 28;65(2):135–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raifman J, Dean LT, Montgomery MC, Almonte A, Arrington-Sanders R, Stein MD, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis awareness among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2019. October 1;23(10):2706–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV infection risk, prevention, and testing behaviors among men who have sex with men national HIV behavioral surveillance 23 U.S. cities, 2017 [Internet]. 2019. Report No.: 22. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-special-report-number-22.pdf

- 48.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, et al. The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2015. February;105(2):e75–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhodes SD, Martinez O, Song E-Y, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Eng E, et al. Depressive symptoms among immigrant Latino sexual minorities. Am J Health Behav. 2013. May;37(3):404–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pachankis JE, McConocha EM, Reynolds JS, Winston R, Adeyinka O, Harkness A, et al. Project ESTEEM protocol: A randomized controlled trial of an LGBTQ-affirmative treatment for young adult sexual minority men’s mental and sexual health. BMC Public Health. 2019. August 9;19(1):1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lang AJ, Norman SB, Means-Christensen A, Stein MB. Abbreviated brief symptom inventory for use as an anxiety and depression screening instrument in primary care. Depress Anxiety. 2008;n/a–n/a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983. August;13(3):595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Orellana ER, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Miller KM, Catania J, Epperson M, et al. Sex trading and other HIV risks among drug-involved men: Differential associations with childhood sexual abuse. Soc Work Res. 2014. June 1;38(2):117–26. [Google Scholar]

- 54.AIDSVu [Internet]. Emory University, Rollins School of Public Health; Available from: aidsvu.org [Google Scholar]

- 55.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHHSTP AtlasPlus [Internet]. cdc.gov. 2019. [cited 2020 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/NCHHSTP/Atlas/

- 56.New Jersey Department of Health. County and municipal HIV/AIDS statistics, 2018 [Internet]. state.nj.us. 2018. [cited 2020 Feb 5]. Available from: https://www.State.nj.us/health/hivstdtb/hiv-aids/statmap.shtml

- 57.Kuhn M, Johnson K. Applied Predictive Modeling. 1st ed. 2013, Corr. 2nd printing 2018 edition. New York: Springer; 2013. 613 p. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Caetano SJ, Sonpavde G, Pond GR. C-statistic: A brief explanation of its construction, interpretation and limitations. Eur J Cancer Oxf Engl 1990. 2018;90:130–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Therneau TM, Atkinson EJ. An introduction to recursive partitioning using the RPART routines [Internet]. 2019. April. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rpart/vignettes/longintro.pdf

- 60.Huamani KF, Metch B, Broder G, Andrasik M. A demographic analysis of racial/ethnic minority enrollment into HVTN preventive early phase HIV vaccine clinical tials conducted in the United States, 2002-2016. Public Health Rep. 2019;134(1):72–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orellana ER, Picciano JF, Roffman RA, Swanson F, Kalichman SC. Correlates of nonparticipation in an HIV prevention program for MSM. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006. August;18(4):348–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Joseph HA, Belcher L, O’Donnell L, Fernandez MI, Spikes PS, Flores SA. HIV testing among sexually active Hispanic/Latino MSM in Miami-Dade County and New York City: opportunities for increasing acceptance and frequency of testing. Health Promot Pract. 2014. November;15(6):867–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mackellar DA, Hou S-I, Whalen CC, Samuelsen K, Sanchez T, Smith A, et al. Reasons for not HIV testing, testing intentions, and potential use of an over-the-counter rapid HIV test in an internet sample of men who have sex with men who have never tested for HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2011. May;38(5):419–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evangeli M, Kafaar Z, Kagee A, Swartz L, Bullemor-Day P. Does message framing predict willingness to participate in a hypothetical HIV vaccine trial: An application of Prospect Theory. AIDS Care. 2013. May 8;25(7):910–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mavandadi S, Wright E, Klaus J, Oslin D. Message framing and engagement in specialty mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017. December 1;69(3):308–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pew Research Center. Chapter 3: The coming out experience [Internet]. 2013. June [cited 2020 Oct 8]. (A survey of LGBT Americans attitudes, experiences and values in changing times). Available from: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2013/06/13/chapter-3-the-coming-out-experience/

- 67.Wejnert C, Hess KL, Rose CE, Balaji A, Smith JC, Paz-Bailey G. Age-specific race and ethnicity disparities in HIV infection and awareness among men who have sex with men—20 US cities, 2008–2014. J Infect Dis. 2016. March 1;213(5):776–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dowshen N, Lee S, Matty Lehman B, Castillo M, Mollen C. Iknowushould2: Feasibility of a youth-driven social media campaign to promote STI and HIV testing among adolescents in Philadelphia. AIDS Behav. 2015. June;19(S2):106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rice E, Tulbert E, Cederbaum J, Barman Adhikari A, Milburn NG. Mobilizing homeless youth for HIV prevention: A social network analysis of the acceptability of a face-to-face and online social networking intervention. Health Educ Res. 2012. April 1;27(2):226–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ybarra ML, Liu W, Prescott TL, Phillips G, Mustanski B. The effect of a text messaging based HIV prevention program on sexual minority male youths: A national evaluation of information, motivation and behavioral skills in a randomized controlled trial of Guy2Guy. AIDS Behav. 2018. October;22(10):3335–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lucassen MFG, Fleming TM, Merry SN. Tips for research recruitment: The views of sexual minority youth. J LGBT Youth. 2017. January 2;14(1):16–30. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bermúdez MJ, Kirkpatrick DR, Hecker L, Torres-Robles C. Describing Latinos families and their help-seeking attitudes: Challenging the family therapy literature. Contemp Fam Ther. 2010. June;32(2):155–72. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mendoza H, Masuda A, Swartout KM. Mental health stigma and self-concealment as predictors of help-seeking attitudes among Latina/o college students in the United States. Int J Adv Couns. 2015. September;37(3):207–22. [Google Scholar]

- 74.United States Census Bureau. 2019 national and state population estimates [Internet]. United States Census Bureau. 2019. [cited 2020 Oct 8]. Available from: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2019/national-state-estimates.html [Google Scholar]

- 75.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2018 [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020. [cited 2020 May 7]. Report No.: 31. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2018-updated-vol-31.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez O A review of current strategies to improve HIV prevention and treatment in sexual and gender minority Latinx (SGML) communities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2020. September 17;1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: Policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health Change Learn Pract. 2001. July 1;14(2):182–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]