Abstract

Astrocytes are traditionally recognized for their multiple roles in support of brain function. However, additional changes in these roles are evident in response to brain diseases. In this review, we highlight positive and negative effects of astrocytes in response to aging, Alzheimer’s disease and Multiple Sclerosis. We summarize data suggesting that reactive astrocytes may perform critical functions that might be relevant to the etiology of these conditions. In particular, we relate astrocytes effects to actions on synaptic transmission, cognition, and myelination. We suggest that a better understanding of astrocyte functions and how these become altered in response to aging or disease will lead to the appreciation of these cells as useful therapeutic targets.

Keywords: astrocytes, aging, Alzheimer’s Disease, Multiple Sclerosis

Introduction

Astrocytes are a heterogenous group of cells that make up to 20–40% of the adult human brain (Rowitch and Kriegstein, 2010; Herculano-Houzel, 2014). The roles of astrocytes are diverse and essential in brain functioning. They regulate ion homeostasis as well as provide structural support (Parpura et al., 2012) and are key in the establishment and regulation of the blood-brain barrier (Lecuyer et al., 2016). In addition, astrocytes provide neurotrophins, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), that enhance function of neurons and oligodendrocytes, promoting survival and differentiation (Xiao et al., 2010; VonDran et al., 2011; Poyhonen et al., 2019). Studies also indicate roles of astrocytes in influencing synaptic function by secreting molecules such as thrombospondin, glypicans and cholesterol (Chung et al., 2015). They are known to participate in synaptic pruning by releasing signals that induce expression of molecules such as complement component 1q in synapses and thereby tag them for elimination by microglia (Chung et al., 2013). Moreover, the astrocyte population can also control the content of several key neurotransmitters in the synapse, most notably glutamate, GABA and adenosine. They take up neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft, thus terminating synaptic transmission. Astrocytes metabolize these neurotransmitters into inert intermediates, which are then returned to neurons to be transformed into active molecules, thus maintaining optimal synaptic transmission (Kreft et al., 2012). Furthermore, by regulating glutamate in the extracellular space they prevent toxicity to proximate cells (Tognatta et al., 2020).

Importantly, when examining the multiple astrocytic functions, it is clear that astrocytes are regionally and subregionally heterogeneous both morphologically and functionally. For example, morphological differences in astrocytes are apparent when those of the hypothalamus, hippocampus and amygdala are described (Emsley and Macklis, 2006). With respect to function, RNA sequencing has identified seven types of astrocytes that are molecularly distinct with respect to their expression of glutamate and glycine transmitter systems and are differentially associated with individual central nervous system (CNS) regions (Zeisel et al., 2018). In another example, within subregions of the cerebellar cortex distinct molecular profiles of receptors, ion channels and transmitter transporters, are observed in different astrocyte populations (Farmer et al., 2016). Note also many other examples of this heterogeneity (O’Malley et al., 1992; Olsen et al., 2007; Takata and Hirase, 2008; Molofsky et al., 2014; John Lin et al., 2017; Kelley et al., 2018; Lanjakornsiripan et al., 2018). These differences may affect the role of astrocytes to regulate neurons in disease. For example, survival of dopaminergic neuronal populations is differentially affected by astrocytes from the substantia nigra, as opposed to those from the ventral tegmentum. Growth and differentiation factor 15, a member of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily that acts in the survival and protection of dopamine neurons, is differentially expressed by these two astrocyte populations, suggesting that expression of a distinct aggregate of factors may impact proximate cell vulnerability in particular diseases (Kostuk et al., 2019).

This article is an overview designed to extend the discussion of astrocyte functions noted above and explore how they are affected in aging, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Multiple Sclerosis (MS) that are apparently pathologically distinct. Aging is a gradual process of natural change that lacks a known pathogenic stimulus but can be triggered by particular genetic predispositions or environmental factors that may increase vulnerability to disease. AD is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder, characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques in the extracellular space and neurofibrillary tangles within neurons. These pathological hallmarks disturb neuronal connectivity within the gray matter. On the other hand, MS is a chronic inflammatory disease with unknown etiology that is characterized by infiltration of immune cells, leading to a succession of inflammatory events and demyelination in the gray and white matter.

Here we focus on how astrocytes are impacted by these conditions and emphasize that they can be stimulated to play both positive and negative roles. An understanding of these roles can lead to manipulations that may be useful and that are relatively poorly understood. For a more comprehensive analysis of the importance of these cells in individual diseases we refer the reader to additional presentations (Rodriguez-Arellano et al., 2016; Palmer and Ousman, 2018; Ponath et al., 2018; Brambilla, 2019; Verkhratsky et al., 2019a; Yi et al., 2019).

The essential functions played by astrocytes in the adult brain are altered as adults age (Palmer and Ousman, 2018). Changes in morphology and astrocyte reactivity have been observed in rodents (Morgan et al., 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2016), and humans (Nichols et al., 1993) in a regionally distinct process. For example, GFAP expression is increased in hippocampal astrocytes in aged rodents (Cerbai et al., 2012; Rodriguez et al., 2014) and in humans (David et al., 1997). On the other hand, cortical astrocytes exhibit little change in GFAP in rodents (Rodriguez et al., 2014), while in humans increases in GFAP are apparent, but to a lesser degree than observed in the hippocampus (David et al., 1997). In complementary work, differential gene expression analysis of astrocytes from aged mice demonstrates that astrocytes from the hippocampus and striatum upregulate a larger number of genes associated with astrocyte reactivity, immune response and synapse elimination, than those of the cortex (Clarke et al., 2018). In humans, assessment of gene expression from post-mortem samples indicate that upon aging astrocyte-specific genes also are altered in a region specific manner, in particular, affecting the hippocampus and substantia nigra (Soreq et al., 2017).

As noted, often the reactive changes in astrocytes occur in regions of the brain commonly associated with age-related neurodegenerative diseases, including the hippocampus and cerebellum (Nichols et al., 1993; Rodriguez et al., 2014; Boisvert et al., 2018). The transcription profile of astrocytes from these regions indicates that there are few changes in genes that affect ion homeostasis or genes that induce synaptogenesis. However, proteins of the complement system, such as complement component 3, and major histocompatibility complex class I are upregulated in astrocytes during aging (Boisvert et al., 2018). These pathways are involved in synapse elimination (Huh et al., 2000), suggesting that their upregulation during aging may lead to cognitive decline. Moreover, the cholesterol synthesis pathway is downregulated in aging astrocytes (Boisvert et al., 2018). Astrocyte-derived cholesterol is essential for neuronal dendritic elaboration and presynaptic function (Mauch et al., 2001). Therefore, decreased astrocyte cholesterol synthesis with age may contribute to deficits. As a whole, these changes described during aging, are further impacted in brain diseases, such as AD and MS.

Alzheimer’s Disease

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder associated with a loss of neurons, myelin ensheathment and synaptic degeneration. The loss of selective neuronal populations is the signature cellular feature of AD, with loss occurring in specific brain regions involved in cognition such as the hippocampal CA1 region, cortex and basal forebrain (Katzman, 1986) that results in interactions among many brain regions being clearly affected (Coleman and Yao, 2003). For example, in the basal forebrain the cholinergic neurons that project to the cortex and the hippocampus degenerate (Whitehouse et al., 1982). It is well established that AD not only affects neurons, but also astrocytes (Verkhratsky et al., 2010). However, the contributions of astroglial cells to disease progression are relatively poorly understood.

A common histological feature of the disease is the extracellular deposition of amyloid beta (Aβ) in plaques. However, even early in the disease before amyloid plaques are noted, toxic amyloid oligomers are present and have deleterious effects on neuron function (Lambert et al., 1998; Kayed and Lasagna-Reeves, 2013; Reiss et al., 2018). At this time astrocyte atrophy is observed (Verkhratsky et al., 2019a) and is characterized by a reduced number of thin astrocytic processes compared to those in healthy or resting astrocytes. It has been suggested that by limiting the extent of astrocyte projections, roles astrocytes play to support neuronal survival and synapse function become limited (Verkhratsky et al., 2019b). The early effects on astrocytes are noted in multiple AD mouse models, as opposed to controls of the same age, including 3xTg-AD (Olabarria et al., 2010), and PDAPP-J20 transgenic mice (Beauquis et al., 2013). Similar results are reported in postmortem early AD brain tissue and in astrocytes derived from induced pluripotent stem cells isolated from AD patients (Verkhratsky et al., 2019b). Moreover, studies of mouse models suggest that the early morphological changes in astrocytes occur in a regionally specific manner. At pre-plaque stages atrophy is noted first in the entorhinal cortex, then in the prefrontal cortex and later in the hippocampus (Verkhratsky et al., 2019b). At later stages of the disease when amyloid plaques emerge, the response of astrocytes is somewhat different. Then astrocyte hypertrophy is observed in astrocytes surrounding amyloid plaques and is prevalent in the hippocampus, as opposed to the entorhinal or the prefrontal cortex where Aβ does not induce reactivity (Verkhratsky et al., 2019b).

Evaluation of astrocytic effects in AD leaves us uncertain whether the changes in astrocyte morphology or function coincident with the disease is a result of exposure to amyloid oligomers, or Aβ plaques. Alternatively, it is possible that changes in astrocyte function contribute to pathogenesis of AD. In an attempt to investigate these two possibilities a number of studies have exposed astrocyte to Aβ in culture. While Aβ affects astrocyte morphology, it also alters astrocyte function. Thus, exposure of cultured astrocytes from cerebral cortices to Aβ decreases the secretion of the extracellular matrix protein thrombospondins, TSP-1, from astrocytes (Christopherson et al., 2005; Liauw et al., 2008). The reduction in TSP-1 is associated with a significant reduction in synaptophysin and PSD95 synaptic proteins in hippocampal neuronal cultures exposed to conditioned media from the Aβ -treated astrocytes (Rama Rao et al., 2013). In another example, astrocytes from late stage, 9-month-old APP/PS1dE9 transgenic AD mice or 3xTg-AD mice significantly upregulate GFAP, suggesting they are impacted by their AD environment. However, inhibition of their reactivity by modulation of the JAK2-STAT3 pathway in these astrocytes reduces not only GFAP upregulation, but also the number of amyloid deposits in the hippocampus (Ceyzeriat et al., 2018). Therefore, astrocytes are influenced by the environment to change their function, but changes in their function can in turn affect their environment, suggesting that the two processes collaborate as AD progresses.

Interestingly, downregulation of this astrocyte reactivity by inhibition of the JAK2-STAT3 pathway is associated with changes in cognition. Behavioral assessments demonstrate that spatial learning is improved in this case in the APP mice and synaptic deficits are reversed in 3xTg-AD mice. The study suggests that astrocytes through the action of the JAK2-STAT3 pathway may contribute to the detrimental effects on learning occurring in progression of AD (Ceyzeriat et al., 2018).

Other astrocyte functions also are affected by Aβ, predicting the effects in vivo on cognition and synaptic dysfunction. For example, exposure of cultured astrocytes to Aβ decreases glutamate uptake into astrocytes (Matos et al., 2008), and increases glutamate release from astrocytes (Talantova et al., 2013). Moreover, when Aβ is applied to hippocampal preparations from hAPPJ20 AD transgenic mice extrasynaptic NMDA receptors are activated in a process dependent on astrocytes (Talantova et al., 2013). In vivo studies complement the culture work and indicate that APPPS1 mice exhibit reduced expression of the glutamate transporter GLT-1 around Aβ plaques (Hefendehl et al., 2016). Moreover, the function of cells other than neurons may be impacted. It is well established in disease models that high levels of glutamate interact with ionotropic receptors on oligodendrocyte lineage cells where they can elicit deleterious effects (Gallo et al., 1996; Fannon et al., 2015). This may be relevant to models of AD where it is found that glutatmate exposure to cultured oligodendrocytes from PS1 mutant AD mice increases vulnerability to oligodendrocyte death (Pak et al., 2003).

Aβ also affects calcium regulation in astrocytes. For example, Aβ increases the amplitude and velocity of Ca2+ transients within cultured astrocytes (Haughey and Mattson, 2003). This has been attributed in part to increases in matabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (Casley et al., 2009) and subunits of nicotinic cholinergic receptors (Xiu et al., 2005). As a consequence of this, Aβ may enhance calcium waves by increasing intracellular Ca2+ release channels (Grolla et al., 2013) or Ca2+ influx may play a role (Abramov et al., 2004). Interestingly, 32 genes from the transcriptome of astrocytes microdissected from AD patients have been associated with Ca2+ signaling, suggesting a possible contribution of altered astrocyte Ca2+ dynamics to AD associated events (Simpson et al., 2011). These events are hypothesized to disrupt neuronal signal transmission and contribute to the progression of neuronal disease.

In contrast to the multiple studies of detrimental effects of astrocytes in AD, to be complete we should note the less appreciated beneficial roles astrocytes play that may counter the potentially damaging actions of Aβ (Escartin and Bonvento, 2008; Hamby and Sofroniew, 2010). For example, the ablation of reactive astrocytes in APP23 AD mouse, results in greater memory deficits, decreased synaptic proteins and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines. This is accompanied by an accumulation in extracellular amyloid protein (Katsouri et al., 2020). Astrocytes have the ability to reverse these effects as they can actively internalize and degrade amyloid peptide (Kurt et al., 1999; Nagele et al., 2003; Pihlaja et al., 2008). They protect themselves in other ways as well. Studies indicate that astrocytes produce TGF-β that prevents synapse loss elicited by amyloid oligomers in hippocampal cultures. These culture results may be important in vivo as intracerebroventricular treatment with TGF-β rescues the atrophy of astrocyte processes induced by amyloid oligomers (Diniz et al., 2017). Additionally, post-mortem AD brains contain increased levels of TGF-β, specifically in plaques, suggesting it may play a protective role in pathology (Chao et al., 1994). These data that illustrate some of the beneficial effects of astrocytes in AD suggest the complexity in understanding their function during neurodegeneration.

While it is apparent that astrocyte play diverse roles in AD, future research will be essential to identify those pathways that should be enhanced or inhibited at particular times and in particular environments. A more extensive understanding of the molecular underpinnings associated with astrocyte reactivity is critical to identify potential therapeutic targets to modulate disease progression.

Multiple Sclerosis

MS is an inflammatory disease associated with demyelination of the CNS. Individuals affected by MS may have symptoms such as muscle weakness, numbness of the arms and legs, fatigue, and cognitive impairments. A majority of patients present with relapsing-remitting MS in which they will often experience acute episodes involving deficits of the brainstem, spinal cord, or optic nerve followed by periods of partial recovery; this cycle continues multiple times following the initial episode. This common type of MS is primarily inflammatory, however with time there is a progression of neurological damage that leads to secondary progressive MS characterized by neurological damage without remission (Weinshenker, 1994; Ebers, 2001). In some cases, patients have progressive disease from the onset that is continuous with decline in neurological function without recovery (Lublin and Reingold, 1996; Koch et al., 2009). Pathologically MS is characterized by chronic inflammation, demyelination, axonal or neuronal loss and, as important to this review, reactive astrogliosis. The axonal losses are particularly important because they are a critical component of the chronically demyelinated lesions associated with progressive disease (Filippi et al., 2018; Thompson et al., 2018). Reactive astrocytes participate in the advancement of the disease by affecting oligodendrocytes as well as neurons in positive and negative directions.

An early sign of MS is the breakdown of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) manifested by morphological changes in astrocytes including swollen cell bodies and retraction of astrocytic end-feet. These changes result in BBB disruption allowing for the entry of inflammatory molecules (Brosnan and Raine, 2013). Studies evaluating this process in a model of MS, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), describe that a loss of the astrocytic extracellular matrix receptor β-dystroglycan in astrocytic end-feet leads to a loss in the polarization of the water channel aquaporin 4, and thus to edema (Wolburg-Buchholz et al., 2009). As the disease progresses astroglial reactivity is observed with elevated GFAP expression that is correlated with the formation of MS plaques (D’Amelio et al., 1990). In this case, astrocytes modulate BBB function through the production of cytokines, chemokines, growth factors and oxidants that can further regulate the immune response (Brambilla, 2019). Roles of astrocytes in this process are complex and appear to vary depending on the stage in disease in which they are examined. For example, when astrocytes are ablated early in EAE the loss of barrier is evident and disease severity is enhanced (Voskuhl et al., 2009; Toft-Hansen et al., 2011), suggesting astrocytes have a protective function. However, in another study the deletion of astrocyte-derived CCL2, a chemokine ligand that recruits peripheral immune cells into the brain, results in no effect early in EAE, but a less severe disease course late in the EAE mouse model (Kim et al., 2014; Ponath et al., 2018). These observations lead to the hypothesis that specific manipulation of the inflammatory response in astrocytes could be an effective approach for MS treatment, but whether inhibition or stimulation of astrocytes is warranted depends on the state of the disease.

To add to these observations, a number of studies suggest that reactive astrocytes may impact the demyelination and remyelination processes negatively in other aspects of their function. For example, as was the case in AD, elevated levels of glutamate are evident in lesioned areas (Srinivasan et al., 2005; Al Gawwam and Sharquie, 2017), and analysis of postmortem MS brains and optic tissue suggests that alteration of glutamate transporters, specifically EAAT1 and EAAT2 in glial cells within early and chronic active MS lesions are in position to promote glutamate excitotoxicity (Pitt et al., 2003; Vercellino et al., 2007). Glutamate levels also are increased in EAE mice that exhibit markedly reduced levels of the astrocytic enzymes, including glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase that are known to metabolize glutamate (Hardin-Pouzet et al., 1997). When these EAE mice are treated with AMPA/Kainate receptor antagonists, death of oligodendrocytes and neurons is markedly reduced (Pitt et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000), indicating that astrocytes may contribute to proximate cell death. Furthermore, deletion of AMPA receptors specifically on proteolipid positive cells reduces loss of myelinated axons and clinical scores in the EAE model, suggesting that effects of glutamate are directly on the oligodendrocytes, themselves (Evonuk et al., 2020).

In other studies astrocytes produce a host of molecules that have been shown to inhibit oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) migration and suppress OPC differentiation (Hammond et al., 2014; Tepavcevic et al., 2014). For example, in MS lesions and after a lysolecithin (LPC) induced demyelinating lesion netrin-1 is found in astrocytes while receptors are seen on oligodendrocyte progenitors. Enhancement of netrin-1 prior to OPC recruitment results in a decrease in OPCs and numbers of mature oligodendrocytes within the lesion, resulting in an inhibition of remyelination (Tepavcevic et al., 2014). In another case, endothelin-1 that is highly expressed in reactive astrocytes in MS (D’Haeseleer et al., 2013), as well as in demyelinating models, is shown to reduce remyelination in the LPC model. In a final example, studies of genes expressed in astrocytes in late stages of EAE reveal that the most abundant gene changes evident are those involved in cholesterol synthesis. Decreases in these genes are correlated with increases in genes involved with the immune pathway (Itoh et al., 2018). As noted in the aging section above, astrocyte-derived cholesterol plays a critical role in synapse function (Mauch et al., 2001), but also in the synthesis of myelin (Saher and Stumpf, 2015). When cholesterol synthesis is increased in the EAE mice, the EAE severity is reduced (Itoh et al., 2018). As a whole, these multiple observations suggest that reactive astrocytes may create an inhibitory environment for remyelination.

Interestingly, as was the case in Alzheimer’s disease, astrocytes also may be harnessed to play positive roles. As noted in the discussion of the BBB, a number of studies demonstrate that astrocytes may limit neuroinflammation and promote myelin repair in EAE models. Particularly early in the disease, deletion of reactive astrocytes from EAE mice, enhances severity of disease, suggesting their protective functions (Voskuhl et al., 2009; Toft-Hansen et al., 2011). Astrocytes have also been found to facilitate remyelination following cuprizone elicited demyelination. In this case ablation of reactive astrocytes results in a delayed removal of myelin debris, a loss in the return of oligodendrocytes to the lesion site after 5 weeks, a loss in OPCs and a decrease in recruitment of microglia to the lesion site (Skripuletz et al., 2013). Moreover, astrocytes can be activated to restore neurological function through the actions of growth factors, such as BDNF (Fulmer et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2018). Metabotropic glutamate receptors and BDNF are upregulated in astrocytes following a cuprizone demyelinating lesion. Stimulation of these receptors results in a reversal in deficits in myelin proteins. This reversal is mediated by astrocyte-derived BDNF as it is abrogated by the deletion of BDNF from the astrocytes (Fulmer et al., 2014). Supportive studies suggesting this role of astrocyte-derived BDNF are also noted using the EAE model. BDNF treatment reduces immune cell infiltration and cell apoptosis in EAE (Makar et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2012), and these effects are reversed upon deletion of BDNF from astrocytes or immune cells (Makar et al., 2008; Linker et al., 2010). Thus, these results suggest that astrocytes are sources of trophic factors that may be used to enhance recovery from a demyelinating injury.

Summary

Numerous studies are now defining the critical roles of astrocytes in normal brain function. However, these functions appear to be altered in extent during aging and in response to injury. In all cases astrocytes show remarkable heterogeneity during progression of aging and disease. By alterations in their function they are in position to influence synaptic function. It is striking that astrocytes can affect brain function positively and negatively. The response they elicit depends on the stage of disease and the region being assessed. An intriguing possibility, but a difficult one to address, is that we can take advantage of these differences to target astrocytes during different aspects of injury and promote their positive influences while downregulating their negative influences. In this light, the use of novel tools and methodologies to probe astrocyte functions and signaling during aging and disease, such as single cell RNA sequence, generation of new animal models where specific astrocyte populations can be manipulated by ablation techniques, non-invasive brain stimulation approaches and genomic, metabolomic or lipidomic high-throughput analyses, can provide novel insights in understanding astroglial contribution to CNS physiology and pathophysiology.

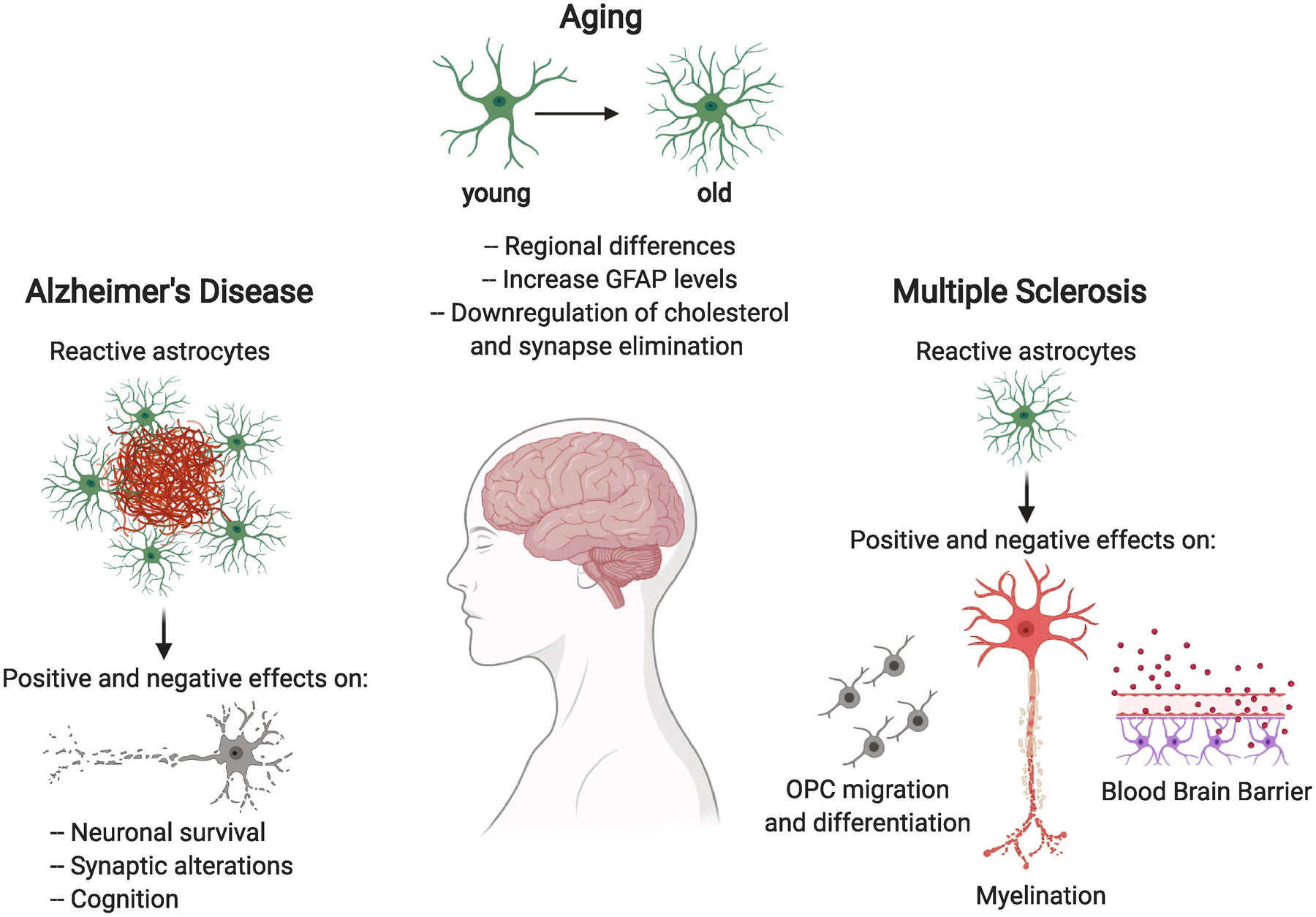

Figure 1.

Astrocytes respond to aging by changes in their morphology and function. These changes are altered further by positive and negative effects on neuronal function and cognition in Alzheimer’s disease and by positive and negative effects on myelin and the blood brain barrier in Multiple Sclerosis.

Astrocyte functions are altered during aging and in response to Alzheimer’s Disease and Multiple Sclerosis.

Astrocytes have beneficial and detrimental effects on neurons and oligodendrocytes during disease.

Understanding these effects can lead to the use of astrocytes as therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgements

The work by the Dreyfus laboratory cited in this review was supported by NMSS grant RG 4257B4/1 and NIH R01 NS036647.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abramov AY, Canevari L, Duchen MR (2004) Calcium signals induced by amyloid beta peptide and their consequences in neurons and astrocytes in culture. Biochim Biophys Acta 1742:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Gawwam G, Sharquie IK (2017) Serum Glutamate Is a Predictor for the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. ScientificWorldJournal 2017:9320802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauquis J, Pavia P, Pomilio C, Vinuesa A, Podlutskaya N, Galvan V, Saravia F (2013) Environmental enrichment prevents astroglial pathological changes in the hippocampus of APP transgenic mice, model of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp Neurol 239:28–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisvert MM, Erikson GA, Shokhirev MN, Allen NJ (2018) The Aging Astrocyte Transcriptome from Multiple Regions of the Mouse Brain. Cell Rep 22:269–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla R (2019) The contribution of astrocytes to the neuroinflammatory response in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol 137:757–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan CF, Raine CS (2013) The astrocyte in multiple sclerosis revisited. Glia 61:453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casley CS, Lakics V, Lee HG, Broad LM, Day TA, Cluett T, Smith MA, O’Neill MJ, Kingston AE (2009) Up-regulation of astrocyte metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 by amyloid-beta peptide. Brain Res 1260:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerbai F, Lana D, Nosi D, Petkova-Kirova P, Zecchi S, Brothers HM, Wenk GL, Giovannini MG (2012) The neuron-astrocyte-microglia triad in normal brain ageing and in a model of neuroinflammation in the rat hippocampus. PLoS One 7:e45250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyzeriat K et al. (2018) Modulation of astrocyte reactivity improves functional deficits in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol Commun 6:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Hu S, Frey WH 2nd, Ala TA, Tourtellotte WW, Peterson PK (1994) Transforming growth factor beta in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 1:109–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS, Ullian EM, Stokes CC, Mullowney CE, Hell JW, Agah A, Lawler J, Mosher DF, Bornstein P, Barres BA (2005) Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis. Cell 120:421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WS, Allen NJ, Eroglu C (2015) Astrocytes Control Synapse Formation, Function, and Elimination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7:a020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WS, Clarke LE, Wang GX, Stafford BK, Sher A, Chakraborty C, Joung J, Foo LC, Thompson A, Chen C, Smith SJ, Barres BA (2013) Astrocytes mediate synapse elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK pathways. Nature 504:394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LE, Liddelow SA, Chakraborty C, Munch AE, Heiman M, Barres BA (2018) Normal aging induces A1-like astrocyte reactivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E1896–E1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PD, Yao PJ (2003) Synaptic slaughter in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 24:1023–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio FE, Smith ME, Eng LF (1990) Sequence of tissue responses in the early stages of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (EAE): immunohistochemical, light microscopic, and ultrastructural observations in the spinal cord. Glia 3:229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Haeseleer M, Beelen R, Fierens Y, Cambron M, Vanbinst AM, Verborgh C, Demey J, De Keyser J (2013) Cerebral hypoperfusion in multiple sclerosis is reversible and mediated by endothelin-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:5654–5658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David JP, Ghozali F, Fallet-Bianco C, Wattez A, Delaine S, Boniface B, Di Menza C, Delacourte A (1997) Glial reaction in the hippocampal formation is highly correlated with aging in human brain. Neurosci Lett 235:53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz LP, Tortelli V, Matias I, Morgado J, Bergamo Araujo AP, Melo HM, Seixas da Silva GS, Alves-Leon SV, de Souza JM, Ferreira ST, De Felice FG, Gomes FCA (2017) Astrocyte Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 Protects Synapses against Abeta Oligomers in Alzheimer’s Disease Model. J Neurosci 37:6797–6809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebers GC (2001) Natural history of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 71 Suppl 2:ii16–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley JG, Macklis JD (2006) Astroglial heterogeneity closely reflects the neuronal-defined anatomy of the adult murine CNS. Neuron Glia Biol 2:175–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Bonvento G (2008) Targeted activation of astrocytes: a potential neuroprotective strategy. Mol Neurobiol 38:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evonuk KS, Doyle RE, Moseley CE, Thornell IM, Adler K, Bingaman AM, Bevensee MO, Weaver CT, Min B, DeSilva TM (2020) Reduction of AMPA receptor activity on mature oligodendrocytes attenuates loss of myelinated axons in autoimmune neuroinflammation. Sci Adv 6:eaax5936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannon J, Tarmier W, Fulton D (2015) Neuronal activity and AMPA-type glutamate receptor activation regulates the morphological development of oligodendrocyte precursor cells. Glia 63:1021–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer WT, Abrahamsson T, Chierzi S, Lui C, Zaelzer C, Jones EV, Bally BP, Chen GG, Theroux JF, Peng J, Bourque CW, Charron F, Ernst C, Sjostrom PJ, Murai KK (2016) Neurons diversify astrocytes in the adult brain through sonic hedgehog signaling. Science 351:849–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, Preziosa P, Solari A, Vukusic S, Rocca MA (2018) Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher JL, Wood RJ, Nguyen J, Norman EML, Jun CMK, Prawdiuk AR, Biemond M, Nguyen HTH, Northfield SE, Hughes RA, Gonsalvez DG, Xiao J, Murray SS (2018) Targeting TrkB with a Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Mimetic Promotes Myelin Repair in the Brain. J Neurosci 38:7088–7099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulmer CG, VonDran MW, Stillman AA, Huang Y, Hempstead BL, Dreyfus CF (2014) Astrocyte-derived BDNF supports myelin protein synthesis after cuprizone-induced demyelination. J Neurosci 34:8186–8196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo V, Zhou JM, McBain CJ, Wright P, Knutson PL, Armstrong RC (1996) Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell proliferation and lineage progression are regulated by glutamate receptor-mediated K+ channel block. J Neurosci 16:2659–2670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grolla AA, Fakhfouri G, Balzaretti G, Marcello E, Gardoni F, Canonico PL, DiLuca M, Genazzani AA, Lim D (2013) Abeta leads to Ca(2)(+) signaling alterations and transcriptional changes in glial cells. Neurobiol Aging 34:511–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamby ME, Sofroniew MV (2010) Reactive astrocytes as therapeutic targets for CNS disorders. Neurotherapeutics 7:494–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TR, Gadea A, Dupree J, Kerninon C, Nait-Oumesmar B, Aguirre A, Gallo V (2014) Astrocyte-Derived Endothelin-1 Inhibits Remyelination through Notch Activation. Neuron 81:1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardin-Pouzet H, Krakowski M, Bourbonniere L, Didier-Bazes M, Tran E, Owens T (1997) Glutamate metabolism is down-regulated in astrocytes during experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Glia 20:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haughey NJ, Mattson MP (2003) Alzheimer’s amyloid beta-peptide enhances ATP/gap junction-mediated calcium-wave propagation in astrocytes. Neuromolecular Med 3:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hefendehl JK, LeDue J, Ko RW, Mahler J, Murphy TH, MacVicar BA (2016) Mapping synaptic glutamate transporter dysfunction in vivo to regions surrounding Abeta plaques by iGluSnFR two-photon imaging. Nat Commun 7:13441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herculano-Houzel S (2014) The glia/neuron ratio: how it varies uniformly across brain structures and species and what that means for brain physiology and evolution. Glia 62:1377–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huh GS, Boulanger LM, Du H, Riquelme PA, Brotz TM, Shatz CJ (2000) Functional requirement for class I MHC in CNS development and plasticity. Science 290:2155–2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N, Itoh Y, Tassoni A, Ren E, Kaito M, Ohno A, Ao Y, Farkhondeh V, Johnsonbaugh H, Burda J, Sofroniew MV, Voskuhl RR (2018) Cell-specific and region-specific transcriptomics in the multiple sclerosis model: Focus on astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E302–E309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John Lin CC, Yu K, Hatcher A, Huang TW, Lee HK, Carlson J, Weston MC, Chen F, Zhang Y, Zhu W, Mohila CA, Ahmed N, Patel AJ, Arenkiel BR, Noebels JL, Creighton CJ, Deneen B (2017) Identification of diverse astrocyte populations and their malignant analogs. Nat Neurosci 20:396–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsouri L, Birch AM, Renziehausen AWJ, Zach C, Aman Y, Steeds H, Bonsu A, Palmer EOC, Mirzaei N, Ries M, Sastre M (2020) Ablation of reactive astrocytes exacerbates disease pathology in a model of Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 68:1017–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R (1986) Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 314:964–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayed R, Lasagna-Reeves CA (2013) Molecular mechanisms of amyloid oligomers toxicity. J Alzheimers Dis 33 Suppl 1:S67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley KW, Ben Haim L, Schirmer L, Tyzack GE, Tolman M, Miller JG, Tsai HH, Chang SM, Molofsky AV, Yang Y, Patani R, Lakatos A, Ullian EM, Rowitch DH (2018) Kir4.1-Dependent Astrocyte-Fast Motor Neuron Interactions Are Required for Peak Strength. Neuron 98:306–319 e307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim RY, Hoffman AS, Itoh N, Ao Y, Spence R, Sofroniew MV, Voskuhl RR (2014) Astrocyte CCL2 sustains immune cell infiltration in chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 274:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Kingwell E, Rieckmann P, Tremlett H (2009) The natural history of primary progressive multiple sclerosis. Neurology 73:1996–2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostuk EW, Cai J, Iacovitti L (2019) Subregional differences in astrocytes underlie selective neurodegeneration or protection in Parkinson’s disease models in culture. Glia 67:1542–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreft M, Bak LK, Waagepetersen HS, Schousboe A (2012) Aspects of astrocyte energy metabolism, amino acid neurotransmitter homoeostasis and metabolic compartmentation. ASN Neuro 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurt MA, Davies DC, Kidd M (1999) beta-Amyloid immunoreactivity in astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease brain biopsies: an electron microscope study. Exp Neurol 158:221–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MP, Barlow AK, Chromy BA, Edwards C, Freed R, Liosatos M, Morgan TE, Rozovsky I, Trommer B, Viola KL, Wals P, Zhang C, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (1998) Diffusible, nonfibrillar ligands derived from Abeta1–42 are potent central nervous system neurotoxins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:6448–6453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanjakornsiripan D, Pior BJ, Kawaguchi D, Furutachi S, Tahara T, Katsuyama Y, Suzuki Y, Fukazawa Y, Gotoh Y (2018) Layer-specific morphological and molecular differences in neocortical astrocytes and their dependence on neuronal layers. Nat Commun 9:1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuyer MA, Kebir H, Prat A (2016) Glial influences on BBB functions and molecular players in immune cell trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1862:472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DH, Geyer E, Flach AC, Jung K, Gold R, Flugel A, Linker RA, Luhder F (2012) Central nervous system rather than immune cell-derived BDNF mediates axonal protective effects early in autoimmune demyelination. Acta Neuropathol 123:247–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liauw J, Hoang S, Choi M, Eroglu C, Choi M, Sun GH, Percy M, Wildman-Tobriner B, Bliss T, Guzman RG, Barres BA, Steinberg GK (2008) Thrombospondins 1 and 2 are necessary for synaptic plasticity and functional recovery after stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 28:1722–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linker RA, Lee DH, Demir S, Wiese S, Kruse N, Siglienti I, Gerhardt E, Neumann H, Sendtner M, Luhder F, Gold R (2010) Functional role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neuroprotective autoimmunity: therapeutic implications in a model of multiple sclerosis. Brain : a journal of neurology 133:2248–2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lublin FD, Reingold SC (1996) Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis: results of an international survey. National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA) Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials of New Agents in Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology 46:907–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makar TK, Trisler D, Sura KT, Sultana S, Patel N, Bever CT (2008) Brain derived neurotrophic factor treatment reduces inflammation and apoptosis in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci 270:70–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Augusto E, Oliveira CR, Agostinho P (2008) Amyloid-beta peptide decreases glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes: involvement of oxidative stress and mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades. Neuroscience 156:898–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauch DH, Nagler K, Schumacher S, Goritz C, Muller EC, Otto A, Pfrieger FW (2001) CNS synaptogenesis promoted by glia-derived cholesterol. Science 294:1354–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky AV, Kelley KW, Tsai HH, Redmond SA, Chang SM, Madireddy L, Chan JR, Baranzini SE, Ullian EM, Rowitch DH (2014) Astrocyte-encoded positional cues maintain sensorimotor circuit integrity. Nature 509:189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan TE, Xie Z, Goldsmith S, Yoshida T, Lanzrein AS, Stone D, Rozovsky I, Perry G, Smith MA, Finch CE (1999) The mosaic of brain glial hyperactivity during normal ageing and its attenuation by food restriction. Neuroscience 89:687–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagele RG, D’Andrea MR, Lee H, Venkataraman V, Wang HY (2003) Astrocytes accumulate A beta 42 and give rise to astrocytic amyloid plaques in Alzheimer disease brains. Brain Res 971:197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols NR, Day JR, Laping NJ, Johnson SA, Finch CE (1993) GFAP mRNA increases with age in rat and human brain. Neurobiol Aging 14:421–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley EK, Sieber BA, Black IB, Dreyfus CF (1992) Mesencephalic type I astrocytes mediate the survival of substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons in culture. Brain Res 582:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olabarria M, Noristani HN, Verkhratsky A, Rodriguez JJ (2010) Concomitant astroglial atrophy and astrogliosis in a triple transgenic animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 58:831–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen ML, Campbell SL, Sontheimer H (2007) Differential distribution of Kir4.1 in spinal cord astrocytes suggests regional differences in K+ homeostasis. J Neurophysiol 98:786–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak K, Chan SL, Mattson MP (2003) Presenilin-1 mutation sensitizes oligodendrocytes to glutamate and amyloid toxicities, and exacerbates white matter damage and memory impairment in mice. Neuromolecular Med 3:53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer AL, Ousman SS (2018) Astrocytes and Aging. Front Aging Neurosci 10:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parpura V, Heneka MT, Montana V, Oliet SH, Schousboe A, Haydon PG, Stout RF Jr., Spray DC, Reichenbach A, Pannicke T, Pekny M, Pekna M, Zorec R, Verkhratsky A (2012) Glial cells in (patho)physiology. J Neurochem 121:4–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pihlaja R, Koistinaho J, Malm T, Sikkila H, Vainio S, Koistinaho M (2008) Transplanted astrocytes internalize deposited beta-amyloid peptides in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Glia 56:154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Werner P, Raine CS (2000) Glutamate excitotoxicity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Nat Med 6:67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Nagelmeier IE, Wilson HC, Raine CS (2003) Glutamate uptake by oligodendrocytes: Implications for excitotoxicity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 61:1113–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponath G, Park C, Pitt D (2018) The Role of Astrocytes in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Immunol 9:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poyhonen S, Er S, Domanskyi A, Airavaara M (2019) Effects of Neurotrophic Factors in Glial Cells in the Central Nervous System: Expression and Properties in Neurodegeneration and Injury. Front Physiol 10:486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rama Rao KV, Curtis KM, Johnstone JT, Norenberg MD (2013) Amyloid-beta inhibits thrombospondin 1 release from cultured astrocytes: effects on synaptic protein expression. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 72:735–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss AB, Arain HA, Stecker MM, Siegart NM, Kasselman LJ (2018) Amyloid toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Rev Neurosci 29:613–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JJ, Butt AM, Gardenal E, Parpura V, Verkhratsky A (2016) Complex and differential glial responses in Alzheimer’s disease and ageing. Curr Alzheimer Res 13:343–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez JJ, Yeh CY, Terzieva S, Olabarria M, Kulijewicz-Nawrot M, Verkhratsky A (2014) Complex and region-specific changes in astroglial markers in the aging brain. Neurobiol Aging 35:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Arellano JJ, Parpura V, Zorec R, Verkhratsky A (2016) Astrocytes in physiological aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience 323:170–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowitch DH, Kriegstein AR (2010) Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial-cell specification. Nature 468:214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saher G, Stumpf SK (2015) Cholesterol in myelin biogenesis and hypomyelinating disorders. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851:1083–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JE, Ince PG, Shaw PJ, Heath PR, Raman R, Garwood CJ, Gelsthorpe C, Baxter L, Forster G, Matthews FE, Brayne C, Wharton SB, Function MRCC, Ageing Neuropathology Study G (2011) Microarray analysis of the astrocyte transcriptome in the aging brain: relationship to Alzheimer’s pathology and APOE genotype. Neurobiol Aging 32:1795–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skripuletz T, Hackstette D, Bauer K, Gudi V, Pul R, Voss E, Berger K, Kipp M, Baumgartner W, Stangel M (2013) Astrocytes regulate myelin clearance through recruitment of microglia during cuprizone-induced demyelination. Brain : a journal of neurology 136:147–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T, Groom A, Zhu B, Turski L (2000) Autoimmune encephalomyelitis ameliorated by AMPA antagonists. Nat Med 6:62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soreq L, Consortium UKBE, North American Brain Expression C, Rose J, Soreq E, Hardy J, Trabzuni D, Cookson MR, Smith C, Ryten M, Patani R, Ule J (2017) Major Shifts in Glial Regional Identity Are a Transcriptional Hallmark of Human Brain Aging. Cell Rep 18:557–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan R, Sailasuta N, Hurd R, Nelson S, Pelletier D (2005) Evidence of elevated glutamate in multiple sclerosis using magnetic resonance spectroscopy at 3 T. Brain : a journal of neurology 128:1016–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takata N, Hirase H (2008) Cortical layer 1 and layer 2/3 astrocytes exhibit distinct calcium dynamics in vivo. PLoS One 3:e2525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talantova M et al. (2013) Abeta induces astrocytic glutamate release, extrasynaptic NMDA receptor activation, and synaptic loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:E2518–2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepavcevic V, Kerninon C, Aigrot MS, Meppiel E, Mozafari S, Arnould-Laurent R, Ravassard P, Kennedy TE, Nait-Oumesmar B, Lubetzki C (2014) Early netrin-1 expression impairs central nervous system remyelination. Ann Neurol 76:252–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AJ, Baranzini SE, Geurts J, Hemmer B, Ciccarelli O (2018) Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 391:1622–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft-Hansen H, Fuchtbauer L, Owens T (2011) Inhibition of reactive astrocytosis in established experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis favors infiltration by myeloid cells over T cells and enhances severity of disease. Glia 59:166–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognatta R, Karl MT, Fyffe-Maricich SL, Popratiloff A, Garrison ED, Schenck JK, Abu-Rub M, Miller RH (2020) Astrocytes Are Required for Oligodendrocyte Survival and Maintenance of Myelin Compaction and Integrity. Front Cell Neurosci 14:74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercellino M, Merola A, Piacentino C, Votta B, Capello E, Mancardi GL, Mutani R, Giordana MT, Cavalla P (2007) Altered glutamate reuptake in relapsing-remitting and secondary progressive multiple sclerosis cortex: correlation with microglia infiltration, demyelination, and neuronal and synaptic damage. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 66:732–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Parpura V, Rodriguez-Arellano JJ, Zorec R (2019a) Astroglia in Alzheimer’s Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1175:273–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Olabarria M, Noristani HN, Yeh CY, Rodriguez JJ (2010) Astrocytes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics 7:399–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A, Rodrigues JJ, Pivoriunas A, Zorec R, Semyanov A (2019b) Astroglial atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Pflugers Arch 471:1247–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VonDran MW, Singh H, Honeywell JZ, Dreyfus CF (2011) Levels of BDNF impact oligodendrocyte lineage cells following a cuprizone lesion. J Neurosci 31:14182–14190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voskuhl RR, Peterson RS, Song B, Ao Y, Morales LB, Tiwari-Woodruff S, Sofroniew MV (2009) Reactive astrocytes form scar-like perivascular barriers to leukocytes during adaptive immune inflammation of the CNS. J Neurosci 29:11511–11522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinshenker BG (1994) Natural history of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 36 Suppl:S6–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse PJ, Price DL, Struble RG, Clark AW, Coyle JT, Delon MR (1982) Alzheimer’s disease and senile dementia: loss of neurons in the basal forebrain. Science 215:1237–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolburg-Buchholz K, Mack AF, Steiner E, Pfeiffer F, Engelhardt B, Wolburg H (2009) Loss of astrocyte polarity marks blood-brain barrier impairment during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol 118:219–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Wong AW, Willingham MM, van den Buuse M, Kilpatrick TJ, Murray SS (2010) Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes central nervous system myelination via a direct effect upon oligodendrocytes. Neurosignals 18:186–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiu J, Nordberg A, Zhang JT, Guan ZZ (2005) Expression of nicotinic receptors on primary cultures of rat astrocytes and up-regulation of the alpha7, alpha4 and beta2 subunits in response to nanomolar concentrations of the beta-amyloid peptide(1–42). Neurochem Int 47:281–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi W, Schluter D, Wang X (2019) Astrocytes in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: Star-shaped cells illuminating the darkness of CNS autoimmunity. Brain Behav Immun 80:10–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeisel A, Hochgerner H, Lonnerberg P, Johnsson A, Memic F, van der Zwan J, Haring M, Braun E, Borm LE, La Manno G, Codeluppi S, Furlan A, Lee K, Skene N, Harris KD, Hjerling-Leffler J, Arenas E, Ernfors P, Marklund U, Linnarsson S (2018) Molecular Architecture of the Mouse Nervous System. Cell 174:999–1014 e1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]