Abstract

Despite significant interest in contraception by men, effective methods of male contraception are limited to vasectomy and condoms. Recently, there have been several promising advances in male contraceptive research. This review will update readers on recent research in both hormonal and non-hormonal approaches to male contraception. Hormonal approaches to male contraception have been stymied by adverse effects, formulations requiring injections or implants, a 5-10% non-response rate, as well as poor understanding of user acceptability. In the last several years, research has focused on novel, orally bio-available androgens such as dimethandrolone undecanoate and 11β-methyl-19-nor-testosterone. Additionally combinations of a topical testosterone gel combined with a gel containing Nestorone, a potent progestin, have shown promise in clinical trials recently. Simultaneously, significant pre-clinical progress has been made in several approaches to non-hormonal male contraceptives, including compounds that inhibit sperm motility such as EPPIN, compounds which inhibit retinoic acid binding or biosynthesis, and reversible approaches to obstruction of the vas deferens. It is imperative for both these areas of research to continue making strides so that there is a gamut of contraceptive options for couples to choose from. Some of these approaches will hopefully reach clinical utility soon, greatly improving contraceptive choice for couples.

Keywords: Male contraception, dimethandrolone, nestorone, RISUG, spermatogenesis

Capsule:

Recently, there have been several promising advances in male contraceptive research. Some of these approaches will hopefully reach clinical utility soon, greatly improving contraceptive choice for couples.

INTRODUCTION

The development of female contraceptive methods had great impacts on fertility rate, women’s health, the role of women in society and sexual practices of adults and adolescents (1). Failure rates of these methods range from <1% to over 20% (2), depending on the method, with numerous reversible options. However, a significant proportion of women have contraindications to currently available female contraceptives or experience adverse effects from the use of these methods, resulting in method discontinuation. The only effective and reversible male contraception option is condoms, the use of which is associated with a 13% on year failure rate of unintended pregnancy (3). As a result of the shortcomings of current female contraceptives and very limited male contraceptive options, rates of unplanned pregnancy have largely remained at around 44% globally for some time (4,5), accounting for roughly 100 million unintended pregnancies yearly. Interestingly, surveys of couples have shown that the majority of men and women would be likely to accept and use safe and effective male contraceptive methods, were they to become available (6-9). In this article, we will review the most recent advances in the field of male contraceptive research, work aimed at reducing the currently high rate of unintended pregnancy.

MALE REPRODUCTIVE PHYSIOLOGY

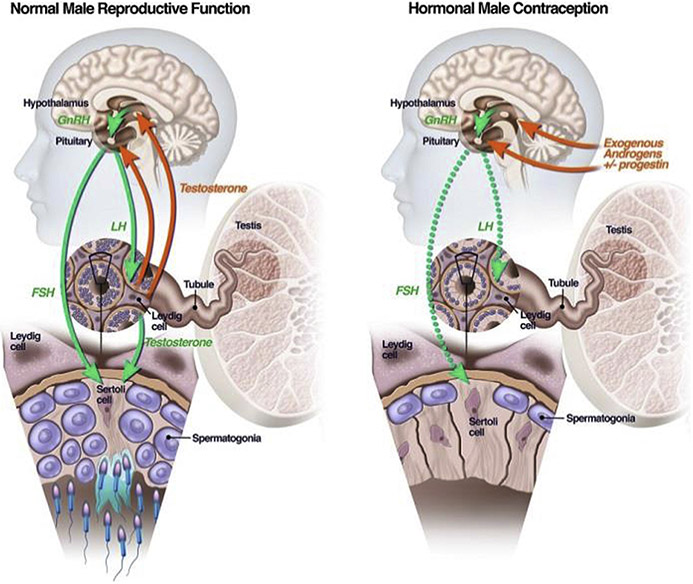

In men, the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis regulates production of testosterone (T) and sperm (Figure 1, left panel). The hypothalamus releases gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the pituitary to release gonadotropins – luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). LH stimulates the Leydig cells of the testes to produce T and FSH stimulates the Sertoli cells, the function of which is necessary for sperm production. Testosterone also binds androgen receptors (AR) in the pituitary that suppress the release of LH and FSH, in a highly regulated feedback loop. Hormonal contraceptive methods exploit this feedback inhibition (Figure 1, right panel) by providing exogenous androgens that bind to AR in the brain and inhibit the release of LH and FSH. Gonadotropin suppression turns off the stimulation of the Leydig and Sertoli cells in the testes, markedly lowering intra-testicular testosterone biosynthesis and Sertoli cell function, leading to a cessation of spermatogenesis in most men. At the same time, the exogenously administered T binds to AR in other tissues, preventing the development of signs and symptoms of hypogonadism. Clinical trials of various hormonal male contraceptive regimens have revealed that the addition of a progestin to the androgen enhances the speed and magnitude of gonadotropin suppression (10), and may even directly inhibit spermatogenesis (11). As a result, most male contraceptive regimens use both androgens and progestins. It takes around 72 days to produce mature sperm from the spermatogonial stem cells (12), which is why male contraceptives that inhibit sperm production, such as hormonal methods, are associated with a 2-3 month delay in the onset of efficacy. Similarly, sperm production is only restored several months after discontinuation or a hormonal method. After sperm are produced, they are stored in the epididymis until ejaculation, only gaining their full motility and capacity to fertilize the egg once within the female urogenital tract. Non-hormonal approaches to male contraception have focused on interrupting different steps in these processes, ranging from interfering with sperm production, to blocking sperm transport during ejaculation or impairing the ability of the sperm to gain motility after ejaculation.

Figure 1.

The normal hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis is depicted on the left. Green arrows are stimulatory and red arrows inhibitory. On the right is the situation induced by hormonal male contraceptives in which exogenous androgens and progestins suppress the release of FSH and LH from the pituitary (dotted green arrows), depriving the testes of the local signals required for spermatogenesis.

HORMONAL MALE CONTRACEPTIVE METHODS – WHAT IS KNOWN

The clinical trials testing androgen/progestin male contraceptive trials conducted to date have been elegantly summarized in prior reviews (13-15). The lessons learnt from these trials are marked gonadotropin suppression to concentrations well below the lower limit of the normal range is required, but not sufficient, for effective suppression of spermatogenesis. For one regimen, only men who suppressed serum FSH and LH to ≤1 IU/L had suppression of sperm concentrations to under 1 million sperm per milliliter of ejaculate (16), a concentration of sperm associated with a roughly 1% rate of unintended pregnancy (17). Normally, sperm concentrations in men exceed 15 million sperm per milliliter of ejaculate. Ideally, male contraceptive regimens would suppress sperm production to zero (azoospermia); however, achieving high rates of azoospermia has proven very difficult. For example, only 70% of men achieved this target in one large male hormonal contraceptive trial (17,18). The good news is that the efficacy at prevention of unintended pregnancy is <1% when azoospermia is achieved, a rate similar to the most effective female methods available currently (2). In the most recent male hormonal contraceptive trials, sperm concentrations of under 1 million sperm per milliliter of ejaculate (severe oligozoospermia) have been achieved in around 95% of men (19-21), a contraceptive efficacy similar to that of female oral contraceptives (3).

CHALLENGES FACING MALE HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION

Male hormonal contraceptive trials have reported a number of adverse side effects, including signs such as acne and weight gain and symptoms such as: depression and reduced libido (22), although the rates of these symptoms is similar to that reported by women using female hormonal methods of contraception (23). Women using hormonal contraception experienced more headaches and weight gain than men, but decrease in libido was comparable across genders. In contrast, men in hormonal contraceptive trials experience more acne, increases in libido and depression (23). Women were more likely to discontinue use of the contraceptive agent than men (23), but this may be due to the fact that the data from women came from real-world use (24), while the male data come from a contraceptive efficacy trial (21), in which the men are self-selected volunteers. The issue of depression in men in male contraceptive studies is particularly worrisome. A recent, large efficacy study of testosterone undecanoate and norethisterone enanthate injections in men was terminated early after an external safety review by the World Health Organization (WHO) due to an undue number of adverse events related to depression, including one suicide, increased libido and injection site pain. As a result, future male hormonal contraceptive studies will need to follow subject’s mood very closely to ensure no harm comes to study subjects.

To date, most male hormonal contraceptive studies have administered the hormones via injections or implants and this comes with both the requirement for medical visits for dosing and significant discomfort to the subjects from the injections or implants procedures (14). Previously, oral androgens have not been frequently studied either due to concern for hepatotoxicity or the need for multiple daily doses (25). Survey data suggests that men might prefer a pill over other delivery methods for hormone delivery (6).

One challenge that male hormonal contraceptives may not be able to address is the 2-3 months it takes to suppress the sperm concentrations to contraceptive thresholds, (10) and the equally long time it takes for recovery of the numbers to normal, when the method is discontinued. These times depend somewhat on the method of hormone delivery and duration of use (26), but reassuringly, hormonal contraception appears to be fully reversible in almost all men. The biggest mystery in the field of male hormonal contraception is why 5-10% of men fail to fully suppress their sperm concentrations in most clinical trials. While explanations such as persistent intra-testicular testosterone (27) and/or persistent gonadotropins (28) have been invoked, the true cause for the sub-optimal response in a small number of subjects remains unclear. Some men (1-2%) also experience “sperm rebound” during efficacy trials, wherein their sperm concentrations transiently rise above the thresholds set for contraceptive efficacy, despite treatment compliance. This phenomenon is not understood.

NOVEL AGENTS FOR MALE HORMONAL CONTRACEPTION

Recent male hormonal contraceptive research has focused on oral and topical methods for self-administration to increase the convenience of use. There are several exciting new oral and topical drugs, Nestorone, dimethandrolone and 11β-19-nor-testosterone that are being tested in male hormonal contraceptive clinical trials. These agents, should they prove to be effective and well tolerated, have the potential for clinical utility. In the following sections, we will review their development in detail.

Nestorone

A novel progestin, segesterone acetate (brand name Nestorone™), has been formulated as a transdermal gel for daily use in male contraceptive trials in combination with a topical T gel. Nestorone is a “pure progestin”, with no androgenic, estrogenic or glucocorticoid activity in vitro (29). It is currently approved for use in women, along with ethinyl estradiol, as a vaginal ring and is well tolerated (30). The first male hormonal contraceptive study in men had participants apply once-daily nestorone gel (variable dose groups of 2-8 mg/day) along with once-daily T gel (10 g/day) for 20 days. This study demonstrated that over 80% of men who received 8 mg/day of nestorone along with T, suppressed their gonadotropins to ≤1 IU/L, 69% of whom suppressed their gonadotropins to less than 0.5 IU/L (31). A subsequent 20-week study showed that among men who received 8-12 mg/day nestorone gel along with T gel (10 g/day), over 88% suppressed their sperm concentrations to under 1 million sperm per milliliter of ejaculate, in contrast to only 23% of men receiving T gel alone (32). The gel was largely well tolerated without significant safety concerns. Five of 99 men in the study discontinued treatment due to adverse events - one for irritability and nightmares, one for decreased libido, one for increased appetite, one for mood swings, and one for an asthma exacerbation (32). Acne was reported by 21% of men, headache by 17%, weight increase by 7% and insomnia by 6% of men during drug exposure (33). Next, Nestorone was formulated as a combination gel (8.3 mg Nestorone and 62.5 mg T) and the combination product demonstrated gonadotropin suppression similar to the two gels used alone after 28 days of treatment (84% men with FSH and LH ≤1 IU/l)(34). Given the promising results of this product, a phase 2B efficacy trial is currently underway using the combined Nestorone/T gel, in 13 sites spanning 4 continents: North America, South America, Europe and Africa. To our knowledge, this trial is the first large-scale, male hormonal contraceptive efficacy trial using a self-administered product. The trial is recruiting 400 couples who will undergo an initial period of sperm suppression until they exhibit a sperm concentration of under 1 million/ml of ejaculate. At this point, men with adequate sperm suppression will enter a 52-week efficacy phase, in which they will only use the study product for contraception. The primary outcome of the study is the rate of unintended pregnancy, with key secondary outcomes being mood and sexual function, as assessed by validated questionnaires.

Novel Oral Androgen: Dimethandrolone

Dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU), is a modified T derivative that is being studied as once daily oral male hormonal contraceptive. Orally dosed DMAU is cleaved by esterases in vivo to the active drug dimethandrolone (DMA). The undecanoate ester both enhances oral absorption when ingested with a fat-containing meal and extends its half-life. DMA does not require 5a-reduction for its action (35) and is not aromatized to an estrogen in vivo (36). Another unique aspect of DMA is that it binds both androgen (AR) and progesterone receptors (PR) with a relative binding affinity four times that of T at the AR and 18% that of progesterone at the PR (37). Animal studies showed that orally administered DMAU was able to reversibly suppress gonadotropins, spermatogenesis and fertility in rodents while still preserving androgenic characteristics (38-40). A first-in-men study of single doses of DMAU at dose ranging from 100-800 mg/orally/day, showed the drug to be well-tolerated when dosed once daily. Similar to oral testosterone undecanoate, oral DMA requires co-administration with a fat-containing meal to optimize absorption (41,42). A subsequent 28-day daily oral dosing study of DMAU showed suppression of serum T to castrate levels in treated men and suppression of serum gonadotropins to ≤ 1 IU/L in all treated groups (43). This study also showed the drug to be mostly well-tolerated by trial participants. DMA is a potent androgen. Therefore, androgenic effects such as weight gain (1.5-3.8 kg), rise in hematocrit (up to 2%), reduction in high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol or HDL-C (6-15 mg/dL) were noted among study subjects (43). Among the participants who received active drug, 11% reported headache, 11% reported decreased libido and 7% reported acne (43). No participants discontinued treatment due to adverse events (43). Given these results, DMAU holds the promise of being a once-daily orally bio-available prototype “male pill”. A 12-week study of DMAU alone and in combination with an oral low-dose progestin, levonorgestrel, has since been completed and the results are forthcoming. In parallel, DMAU has also been formulated as an intramuscular injection and is being studied at various doses as a potential long-acting reversible contraceptive injection.

Novel Oral Androgens: 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone

11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone dodecylcarbonate (11βMNTDC) has many similar features as DMAU, in that it also is can be dosed orally once-daily, is active at both AR and PR (37), is not aromatized (36) and does not require 5a-reduction for its action (35). Pre-clinical studies of 11βMNTDC have demonstrated gonadotropin suppression, while preserving body composition and bone mineral density (38). It has no obvious hepatotoxicity (40). The first human study of 11βMNTDC, similar to DMAU, was a single-dose dose-escalating study, which revealed that the drug did not have obvious toxicity, could be administered once daily, and required administration with fat-containing meal for optimal absorption and suppression of gonadotropins and T (44). A subsequent 28-day daily dosing study tested 200 mg and 400 mg doses of 11βMNTDC and revealed profound suppression of serum T with both doses but greater suppression of gonadotropins to ≤ 1 IU/L at the 400 mg once daily dose (45). Changes in hematocrit, HDL-C and weight were similar to those seen with DMA. A small, but statistically significant rise in serum creatinine and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol were also observed (45). Adverse events in drug-treated men in this study included headache (29%), acne (16%), decreased libido (16%), mood changes (13%), fatigue (13%) and decreased erectile/ejaculatory function (10%) (45). Further studies with this product are still being designed and it is also being considered as a possible long-acting reversible contraceptive injection.

Experimental Non-Hormonal Male Contraceptives

In addition to the work described above attempting to develop hormonal male contraceptives, there has been great interest in trying to develop novel non-hormonal male contraceptive. Non-hormonal male contraception can be defined as an approach to male contraception that doesn’t utilize the administration of testosterone or compounds that block testosterone secretion (46). Non-hormonal contraception may have some advantages compared to hormonal male contraceptives as they would likely avoid any impact on testosterone concentrations and therefore not impact sexual function, sex drive or body composition. In addition, the use of testosterone could lead to disqualification from high-level sporting events. The following sections will describe past and future efforts to develop non-hormonal male contraceptives.

Gossypol

The first widely clinically studied non-hormonal male contraception was gossypol. Gossypol is a large molecule purified from the seeds of a cotton plant grown in China. Gossypol was extensively studied in clinical trials in China in the 1980s in two large phase III studies, enrolling more than 8000 men (47, 48). In these studies, gossypol was demonstrated to reduce both sperm production and sperm motility and induced abnormal sperm morphology via an unknown mechanism. Most men developed azoospermia and Gossypol had a 90% efficacy in pregnancy prevention. Unfortunately, side effects including hypokalemia and hypokalemic periodic paralysis in about 1% of treated men. In addition, spermatogenesis in almost 20% of men did not fully recover. Despite significant efforts to modify the structure of gossypol to reduce the risk of side effects and improve efficacy, the study of Gossypol for non-hormonal male contraception has been largely abandoned (49).

Triptolide

A second naturally-derived male contraceptive compound studied in China was the herb Trypterigium wilfordii, the active compound of which was called triptolide (50). Trypterigium had been in traditional Chinese medicine for many centuries for the treatment of arthritis. Clinical study of patients treated with this compound showed that Trypterigium administration impaired sperm motility and decreased sperm counts. Unfortunately, as was the case with gossypol, several men experienced irreversible suppression of spermatogenesis, causing the abandonment of work studying this compound as a reversible male contraceptive (51).

Adjudin

The compound Adjudin was studied as a non-hormonal male contraceptive in animal studies in the early 2000s (52). The administration of Adjudin to rodents interferes with the ability of spermatids to adhere to Sertoli cells. Because of this, the spermatids undergo premature spermiation resulting in the production of non-functional spermatozoa that are incapable of fertilization. In rats, administration of 50 mg/kg of adjudin twice weekly induced 100% infertility after 5 weeks of treatment. Notably, the administration of Adjudin doesn’t lead to changes in serum gonadotropins or serum testosterone concentrations (53). Unfortunately, several animals experienced liver inflammation in a 29-day study (54). Follow-up work with adjudin conjugated Adjudin to a FSHβ mutant, specifically targeting it to Sertoli cells, reducing systemic exposure (55). Unfortunately, this approach proved prohibitively costly (56), and further study in either animals or humans of this conjugate was not performed.

H2-Gamendazole

H2-Gamendazole is a derivative of adjudin that interferes with the normal functioning of the apical ectoplasmic specialization (57). In one in vivo experiment, all rats receiving a single oral dose of 6 mg/kg of gamendazole became infertile; unfortunately, only half recovered fertility after treatment (58). H2-Gamendazole has also had concerning toxicity. For example, in one study of H2-gamendazole three of five rats dosed with 200 mg/kg died, concerning for a low therapeutic index of this agent. Some pre-clinical study of this compound was performed in hopes eventually performing some human testing, but this has not progressed as hoped.

EPPIN

EPPIN is a protein located on the surface of the sperm. EPPIN functions in liquefaction of the ejaculate, the absence of which severely impairs sperm motility (59). Initial immunization studies in male non-human primates demonstrated that a majority could be immunized against EPPIN. Notably, these males were mated and were unable to father pregnancies. Importantly, the animals re-gained fertility after cessation of the injections (60). After this proof-of-principle immunization study, this research group has focused their work on developing small molecules that inhibit EPPIN binding to the protein semenogelin, which is a necessary step in sperm liquefaction (61). A recent publication demonstrated that IV administration of the small molecule EP055, reduced sperm motility by 80% in male macaques (62). The group is now working on the development of potent, oral compounds in animal studies. Hopefully, continued work on this approach will result in a pill that can effectively reduce sperm motility as a male contraceptive.

BRDT Inhibition

The bromodomain protein, BRDT, is required for meiosis. Intriguingly, men with mutations in the Brdt gene have infertility and semen analysis reveal abnormal sperm heads and poor motility (63). In 2012, a group showed that JQ1, a small molecule that potentially inhibited BRDT function, was shown to reversibly suppress fertility in a murine model (64). Unfortunately, JQ1 inhibits other bromodomain proteins, which leading to toxicity. This group is performing structure-activity modeling of JQ1 in efforts to develop a BRDT specific inhibitor, retaining the contraceptive action while minimizing the potential for side effects (65).

Retinoic Acid Receptor Antagonists

It has been known since 1925 that vitamin-A (retinol) is essential for sperm production and male fertility (66). All of the effects of retinol appear to be mediated by retinoic acid. Retinoic acid has been shown to be necessary both for spermatogenesis (67, 68). Retinoic acid functions via binding to a family of retinoic acid receptors (RARs), which serve to regulate gene expression. Gene knockout experiments have shown that mice with deletion of one of several of the RAR are sterile (69, 70). Based on these observations, several groups are working on developing non-hormonal approaches to male contraception based on the blockade of retinoic acid function or biosynthesis.

One example of such a compound is BMS-189453, which was described in the early 2000s. This compound is an oral RAR pan-antagonist. Initial one-month studies of BMS-189453 at doses of 15, 60, or 240 mg/kg to rats lead to marked testicular degeneration and infertility, but also liver toxicity (71). A second group of investigators followed-up on these earlier studies, testing lower doses of BMS-18945, demonstrating efficacy at sperm suppression without the liver toxicity observed with larger doses (72). For example, mice treated with 2.5-5 mg/kg for 4 weeks were completely sterile by 4 weeks of treatment with return to fertility 12 weeks after the cessation of treatment (73). A specific retinoic acid-alpha antagonist has been reported in the literature (74), more recent versions of which may hold some promise for non-hormonal male contraception (75).

Retinoic Acid Biosynthesis Inhibitors

Almost sixty years ago, the administration of WIN 18,446 was shown to dramatically suppress sperm production in men and was studied as the first non-hormonal male contraceptive in almost 100 men (76, 77). Unfortunately, it was discovered that men taking WIN 18,446 had serious “disulfiram reactions” characterized by vomiting, sweating and palpitations when they drank alcohol while taking WIN 18,446. Because of these severe disulfiram reactions, further study of WIN 18,446 as a male contraceptive stopped. In 2011, it was shown that WIN 18,446 functioned via inhibition of testicular retinoic acid biosynthesis (78). It was further demonstrated that WIN 18,446 inhibited two enzymes called aldehyde dehydrogenase ALDH1A1 and ALDH1A2 that are the final step in retinoic acid production (79). Work in this area is now focused on the production of novel that specifically inhibit ALDH1A1 and 1A2 without causing disulfiram reactions, which are mediated by a similar enzyme ALDH2 (80).

CatSper

In 2001, an investigative group identified a novel sperm-specific calcium channel (81). Genetic deletion of the gene encoding the “CatSper” protein leads to infertility (82). The structure of a candidate CatSper antagonist, HC-056456, has been published (83). When tested In vitro, HC-056456 significantly suppressed sperm motility; however, no in vivo data on is available. Nevertheless, inhibition of Catsper function and research into inhibition of other sperm ion channels necessary for sperm motility as an approach to male contraception is ongoing (84).

Gendarussa

An Indonesian traditional medicine called Justicia gendarussa has been reported to be used as traditional form of contraception by men in Papua New Guinea. The active ingredient is thought to be a flavonoid called gendarusin A (85). Some data on contraceptive efficacy for this compound has been reported in abstract form, but not published. In addition, the mechanism of action remains unclear. Therefore, additional information will be needed to determine whether this is a viable approach to developing a non-hormonal male contraceptive.

Vas Occlusion Methods

Several research groups have conducted research directed towards developing methods to reversibly plug the vas deferens since the 1970s. Reversible vas occlusion is an attractive approach to male contraception, as the initial vasal obstruction could provide long-lasting contraception. Later, the man could have the obstruction removed, and the man have his fertility restored when desired. An Indian vas occlusion device called RISUG (reversible inhibition of sperm under guidance) has been studied in several clinical trials in men (86, 87). The initial procedure is performed under ultrasound guidance. Specifically, a solution of styrene maleic anhydrate is injected into the vas deferens bilaterally, effectively occluding the vas and preventing the passage of sperm during ejaculation. Data from several small clinical trials of RISUG is available (86). Taken together, these studies demonstrate effective contraception over periods of up to one year in men. Unfortunately, no data from large-scale trials or demonstration of reversibility have been published (87).

A re-formulation of RISUG, called “Valsalgel™” in the US was tested as a contraceptive for one year in rabbits (88), and monkeys (89). After reversal, however, the sperm of the rabbits no longer had acrosomes, possibly due to inflammation in the vas, and no return to fertility data on these animals was reported (90). Therefore, as was the case with in the Indian studies, it remains unclear if RISUG is truly reversible. Vas occlusion devices using medical-grade silicone and polyurethane were studied in China in the 1990s (91). These devices also experienced incomplete recovery of sperm parameters after attempted reversal (92), leading the investigators to abandon this approach to male contraception.

Conclusions

Contraception provision is essential for the prevention of unintended pregnancy. Given the limitations of currently available methods of contraception, there is a great deal of interest in the development of novel male contraceptive methods. Numerous hormonal approaches to male contraception tested in human studies and newer studies with novel oral androgen/progestin compounds and topical gels are showing promise. Several non-hormonal approaches have been studied in mostly pre-clinical studies, but human studies to determine their safety and efficacy are lacking. Ongoing work in male contraceptive research is required to meet the unmet need of male-driven methods of birth control.

Acknowledgment:

This work was supported, in part, by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, a division of the National Institute of Health through grant R01HD098039 (JKA).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure Statement: JKA has received research and consultancy funding from Clarus Therapeutics

References

- 1.Tyrer L Introduction of the pill and its impact. Contraception 1999;59(1 Suppl):11S–16S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trussell J Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundaram A, Vaughan B, Kost K, Bankole A, Finer L, Singh S, Trussell J. Contraceptive Failure in the United States: Estimates from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2017;49:7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah I, Ahman E. Unsafe abortion in 2008: global and regional levels and trends. Reprod Health Matters 2010;18:90–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bearak J, Popinchalk A, Alkema L, Sedgh G. Global, regional, and subregional trends in unintended pregnancy and its outcomes from 1990 to 2014: estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e380–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin CW, Anderson RA, Cheng L, Ho PC, van der Spuy Z, Smith KB, et al. Potential impact of hormonal male contraception: cross-cultural implications for development of novel preparations. Hum Reprod 2000;15:637–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heinemann K, Saad F, Wiesemes M, White S, Heinemann L. Attitudes toward male fertility control: results of a multinational survey on four continents. Hum Reprod 2005;20:549–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eberhardt J, van Wersch A, Meikle N. Attitudes towards the male contraceptive pill in men and women in casual and stable sexual relationships. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 2009;35:161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glasier A Acceptability of contraception for men: a review. Contraception 2010;82:453–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Anawalt BD, Anderson RA, Bremner WJ, Elliesen J, et al. Determinants of the rate and extent of spermatogenic suppression during hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:1774–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lue Y, Wang C, Lydon JP, Leung A, Li J, Swerdloff RS. Functional role of progestin and the progesterone receptor in the suppression of spermatogenesis in rodents. Andrology 2013;1:308–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heller CH, Clermont Y. Kinetics of the Germinal Epithelium in Man. Recent Prog Horm Res 1964;20:545–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieschlag E Clinical trials in male hormonal contraception. Contraception 2010;82:457–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Festin MP, Swerdloff RS. Male Hormonal Contraception: Where Are We Now? Curr Obstet Gynecol Rep 2016;5:38–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amory JK. Male contraception. Fertil Steril 2016;106:1303–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roth MY, Ilani N, Wang C, Page ST, Bremner WJ, et al. Characteristics associated with suppression of spermatogenesis in a male hormonal contraceptive trial using testosterone and Nestorone gels. Andrology 2013;1:899–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia in normal men. World Health Organization Task Force on methods for the regulation of male fertility. Lancet 1990;336(8721):955–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Task Force on Methods for the Regulation of Male F. Contraceptive efficacy of testosterone-induced azoospermia and oligozoospermia in normal men. Fertil Steril 1996;65:821–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gu YQ, Wang XH, Xu D, Peng L, Cheng LF, Huang MK, et al. A multicenter contraceptive efficacy study of injectable testosterone undecanoate in healthy Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gu Y, Liang X, Wu W, Liu M, Song S, Cheng L, et al. Multicenter contraceptive efficacy trial of injectable testosterone undecanoate in Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94(6):1910–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behre HM, Zitzmann M, Anderson RA, Handelsman DJ, Lestari SW, McLachlan RI, et al. Efficacy and Safety of an Injectable Combination Hormonal Contraceptive for Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2016;101:4779–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abbe CR, Page ST, Thirumalai A. Male Contraception. Yale J Biol Med 2020;93:603–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abbe C, Roxby AC. Assessing safety in hormonal male contraception: a critical appraisal of adverse events reported in a male contraceptive trial. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2020;46:139–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daniels K, Mosher WD. Contraceptive methods women have ever used: United States, 1982-2010. Natl Health Stat Report 2013:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nieschlag E, Hoogen H, Bolk M, Schuster H, Wickings EJ. Clinical trial with testosterone undecanoate for male fertility control. Contraception 1978;18:607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Christenson PD, Handelsman DJ, Wang C, Hormonal Male Contraception Summit. Rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal male contraception: an integrated analysis. Lancet 2006;367:1412–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang FP, Pakarainen T, Poutanen M, Toppari J, Huhtaniemi I. The low gonadotropin-independent constitutive production of testicular testosterone is sufficient to maintain spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100:13692–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth MY, Page ST, Lin K, Anawalt BD, Matsumoto AM, Snyder CN, et al. Dose-dependent increase in intratesticular testosterone by very low-dose human chorionic gonadotropin in normal men with experimental gonadotropin deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:3806–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sitruk-Ware R, Nath A. The use of newer progestins for contraception. Contraception 2010;82:410–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson AL. Comprehensive overview of the recently FDA-approved contraceptive vaginal ring releasing segesterone acetate and ethinylestradiol: A new year-long, patient controlled, reversible birth control method. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2019;12:953–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mahabadi V, Amory JK, Swerdloff RS, Bremner WJ, Page ST, Sitruk-Ware R, et al. Combined transdermal testosterone gel and the progestin nestorone suppresses serum gonadotropins in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:2313–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilani N, Roth MY, Amory JK, Swerdloff RS, Dart C, Page ST, et al. A new combination of testosterone and nestorone transdermal gels for male hormonal contraception. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:3476–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilani N, Liu PY, Swerdloff RS, Wang C. Does ethnicity matter in male hormonal contraceptive efficacy? Asian J Androl 2011;13:579–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anawalt BD, Roth MY, Ceponis J, Surampudi V, Amory JK, Swerdloff RS, et al. Combined nestorone-testosterone gel suppresses serum gonadotropins to concentrations associated with effective hormonal contraception in men. Andrology 2019;7:878–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Koduri S, Pham T, Pessaint L, Engbring J, et al. The potent synthetic androgens, dimethandrolone (7alpha,11beta-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) and 11beta-methyl-19-nortestosterone, do not require 5alpha-reduction to exert their maximal androgenic effects. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010;122:212–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attardi BJ, Pham TC, Radler LC, Burgenson J, Hild SA, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone (7alpha,11beta-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) and 11beta-methyl-19-nortestosterone are not converted to aromatic A-ring products in the presence of recombinant human aromatase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2008;110:214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone undecanoate: a new potent orally active androgen with progestational activity. Endocrinology 2006;147:3016–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Attardi BJ, Marck BT, Matsumoto AM, Koduri S, Hild SA. Long-term effects of dimethandrolone 17beta-undecanoate and 11beta-methyl-19-nortestosterone 17beta-dodecylcarbonate on body composition, bone mineral density, serum gonadotropins, and androgenic/anabolic activity in castrated male rats. J Androl 2011;32:183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hild SA, Marshall GR, Attardi BJ, Hess RA, Schlatt S, Simorangkir DR, et al. Development of l-CDB-4022 as a nonsteroidal male oral contraceptive: induction and recovery from severe oligospermia in the adult male cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Endocrinology 2007;148:1784–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hild SA, Attardi BJ, Koduri S, Till BA, Reel JR. Effects of synthetic androgens on liver function using the rabbit as a model. J Androl 2010;31:472–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Surampudi P, Page ST, Swerdloff RS, Nya-Ngatchou JJ, Liu PY, Amory JK, et al. Single, escalating dose pharmacokinetics, safety and food effects of a new oral androgen dimethandrolone undecanoate in man: a prototype oral male hormonal contraceptive. Andrology 2014;2:579–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ayoub R, Page ST, Swerdloff RS, Liu PY, Amory JK, Leung A, et al. Comparison of the single dose pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of two novel oral formulations of dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU): a potential oral, male contraceptive. Andrology 2017;5:278–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thirumalai A, Ceponis J, Amory JK, Swerdloff R, Surampudi V, Liu PY, et al. Effects of 28 Days of Oral Dimethandrolone Undecanoate in Healthy Men: A Prototype Male Pill. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:423–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu S, Yuen F, Swerdloff RS, Pak Y, Thirumalai A, Liu PY, et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single-Dose Novel Oral Androgen 11beta-Methyl-19-Nortestosterone-17beta-Dodecylcarbonate in Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2019;104:629–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuen F, Thirumalai A, Pham C, Swerdloff RS, Anawalt BD, Liu PY, et al. Daily Oral Administration of the Novel Androgen 11beta-MNTDC Markedly Suppresses Serum Gonadotropins In Healthy Men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2020;105:e835–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nya-Ngatchou JJ, Amory JK. New approaches to male non-hormonal contraception. Contraception 2013; 87:296–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu GZ, Lyle KC, Cao J. Clinical trial of gossypol as a male contraceptive drug Part I: Efficacy study. Fertil Steril 1987;48:459–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu GZ, Lyle KC, Cao J. Clinical trial of gossypol as a male contraceptive drug Part II: Hypokalemia study. Fertil Steril 1987;48:462–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waites GM, Wang C, Griffin PK. Gossypol: reasons for its failure to be accepted as a safe, reversible male antifertility drug. Int J Androl 1998;21:8–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qian SZ. Tripterygium wildfordii, a Chinese herb effective in male fertility regulation. Contraception 1987; 36:335–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh PN, Hikim AP, Wang C, Stefonovic K, Lue YH, Leung A, et al. Long-term effects of triptolide on spermatogenesis, epididymal sperm function, and fertility in male rates. J Androl 2000;21:689–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng CY, Silvestrini B, Grima J, Mo MY, Zhu LJ, Johannsson E, et al. Two new male contraceptive exert their effects by depleting germ cells prematurely from the testis. Biol Reprod 2001;65:449–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mruk DD, Cheng CY.Testin and actin are key molecular targets of adjudin, an anti-spermatogenic agent, in the testes. Spermatogenesis 2001;1:137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mok K-W, Mruk DD, Lie PPY, Lui WY, Cheng CY. Adjudin, a potential male contraceptive, exerts its effects locally in the seminiferous epithelium of mammalian testes. Reproduction 2011;141:571–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mruk DD, Wong CH, Silvestrini B, Cheng CY. A male contraceptive targeting germ cell adhesion. Nature Medicine 2006;12:1323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen H, Mruk DD, Xia W, Bonanomi M, Silvestrini B, Cheng C-Y. Effective Delivery of Male Contraceptives Behind the Blood-Testis Barrier- Lessons from Adjudin. Curr Med Chem 2016;23:701–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tash JS, Attardi B, Hild SA, Chakrasali R, Jakkaraj SR, Georg G. A novel potent indazole carboxylic acid derivative blocks spermatogenesis and is contraceptive in rats after a single oral dose. Biol Reprod 2008;78:1127–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tash JS, Chakrasali R, Jakkaraj SR, Hughes J, Smith SK, Hornbaker K, et al. Gamendazole, an orally active indazole carboxylic acid male contraceptive agent, targets HSP90AB1 and EEF1A1, and stimulates II1a transcription in rat Sertoli cells. Biol Reprod 2011;78:1139–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.O'Rand MG, Widgren EE, Hamil KG, Silva EJ, Richardson RT. Functional studies of EPPIN. Biochem Soc Trans 2011;39:1447–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Rand MG, Widgren EE, Sivashanmugam P, Richardson RT, Hall SH, French FS, et al. Reversible immunocontraception in male monkeys immunized with EPPIN. Science 2004; 306:1189–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O'Rand MG, Silva EJ, Hamil KG. Non-hormonal male contraception: A review and development of an EPPIN based contraceptive. Pharmacol Ther 2016;157:105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.O'Rand MG, Hamil KG, Adevai T, Zelinski M. Inhibition of sperm motility in male macaques with EP055, a potential non-hormonal male contraceptive. PLoS One 2018;19:e0195953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li L, Sha Y, Wang X, Li P, Wang J, Kee K, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identified a homozygous BRDT mutation in a patient with acephalic spermatozoa. Oncotarget 2017;8:19914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matzuk MM, McKeown MR, Filippakopoulos P, Li Q, Ma L, Agno JE, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of BRDT for male contraception. Cell 2012;150:673–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolbach SB, Howe PR. Tissue changes following deprivation of fat soluble A Vitamin. J Exp Med 1925;42:753–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vernet N, Dennefeld C, Rochette-Egly C, Oulad-Abdelghani M, Chambon P, Ghyselinck NB, et al. Retinoic acid metabolism and signaling pathways in the adult and developing mouse testis. Endocrinology 2006;147:96–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koubova J, Menke D, Zhou Q, Capel B, Griswold MD, Page DC. Retinoic acid regulates sex-specific timing of meiotic initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:2472–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dufour JM, Kim KH. Cellular and subcellular localization of six retinoid receptors in rat testis during postnatal development: identification of potential heterodimeric receptors. Biol Reprod 1999;61:1300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lufkin T, Lohnes D, Mark M, Dierich A, Gorry P, Gaub MP et al. High postnatal lethality and testis degeneration in retinoic acid receptor alpha mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993;90:7225–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lohnes D, Kastner P, Dierich A, Mark M, LeMeur M, Chambon P. Function of retinoic acid receptor gamma in the mouse. Cell 1993;73:643–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulze GE, Clay RJ, Mezza LE, Bregman CL, Buroker RA, Frantz JD. BMS-189453, a novel retinoid receptor antagonist, is a potent testicular toxin. Toxicol Sci 2001;59:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chung SS, Wang X, Roberts SS, Griffey SM, Reczek PR, Wolgemuth DJ. Oral administration of a retinoic acid receptor antagonist reversibly inhibits spermatogenesis in mice. Endocrinology 2011;152:2492–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chung SS, Wang X, Wolgemuth DJ. Prolonged oral administration of a pan-retinoic acid receptor antagonist inhibits spermatogenesis in mice with a rapid recovery and changes in the expression of influx and efflux transporters. Endocrinology 2016; 157:1601–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung SS, Cuellar RA, Wang X, Reczek PR, Georg G, Wolgemuth DJ. Pharmacological activity of retinoic acid receptor alpha-selective antagonists in vitro and in vivo. ACS Med Chem Lett 2013;4:446–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nomann MDD, Kyzer JL, Chung SSW, Wolgemuth DJ, Georg GI. Retinoic acid receptor antagonists for male contraception: current status. Biol Reprod 2020;103:390–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Heller CG, Moore DJ, Paulsen CA. Suppression of spermatogenesis and chronic toxicity in men by a new series of bis(dichloroacetyl)diamines. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1961;3:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beyler AL, Potts GO, Coulston F, Surrey AR. The selective testicular effects of certain bis(dichloroacetyl)diamines. Endocrinology 1961;69:819–33. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Amory JK, Muller CH, Shimshoni AJ, Isoherranen N, Paik J, Moreb J et al. Suppression of spermatogenesis by bisdichloroacetyldiamines is mediated by inhibition of testicular retinoic acid biosynthesis. J Androl 2011;32:111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Paik J, Haenisch M, Muller CH, Goldstein AS, Arnold S, Isoherranen N, et al. Inhibition of retinoic acid biosynthesis by the bisdichloroacetyldiamine WIN 18,446 markedly suppresses spermatogenesis and alters retinoid metabolism in mice. J Biol Chem 2014;289:15104–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen Y, Zhu J, Ho Hong K, Mikles DC, Georg GI, Goldstein AS, et al. Structural basis of ALDH1A2 inhibition by irreversible and reversible small molecule inhibitors ACS Chemical Biology 2018;13:582–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ren D, Navarro B, Perez G, Jackson AC, Hsu S, Shi Q et al. A sperm ion channel required for sperm motility and male fertility. Nature 2001;413:603–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Qi H, Moran MM, Navarro B, Chong JA, Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, et al. All four CatSper ion channel proteins are required for male fertility and sperm cell hyperactivated motility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:1219–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Carlson AE, Burnett LA, del Camino D, Quill TA, Hille B, Chong JA, et al. Pharmacological targeting of native CatSper channels reveals a required role in maintenance of sperm hyperactivation. PLoS One 2009;4:e6844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lishko PV. Contraception: Search for an Ideal Unisex Mechanism by Targeting Ion Channels. Trends Biochem Sci 2016. 41:816–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Widyowati R, Agil M. Chemical constituents and bioactivities of several Indonesian plants typically used in jamu. Chem Pharmaceut Bull 2018; 66:506–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guha SK, Singh G, Ansari S, Kumar S, Srivastava A, Koul V, et al. Phase II clinical trial of a vas deferens injectable contraceptive for the male. Contraception 1997;56:245–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lohiya NK, Alam I, Hussain M, Khan SR, Ansari AS. RISUG: an intravasal injectable male contraceptive. Indian J Med Res 2014;140:S63–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Waller D, Bolick D, Lissner E, Premanandan C, Gamerman G. Azoospermia in rabbits following an intravas injection of Vasalgel™. Basic Clin Androl 2016;26:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Colagross-Schouten A, Lemoy MJ, Keesler RI, Lissner E, VandeVoort CA. The contraceptive efficacy of intravas injection of Vasalgel™ for adult male rhesus monkeys. Basic Clin Androl 2017; 27:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Waller D, Bolick D, Lissner E, Premanandan C, Gamerman G. Reversibility of Vasalgel™ male contraceptive in a rabbit model. Basic Clin Androl 2017;27:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhao SC, Zhang SP, Yu RC. Intravasal injection of formed-in-place silicone rubber as a method of vas occlusion. Int J Androl 1992;15:460–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao SC, Lian YH, Yu RC, Zhang SP. Recovery of fertility after removal of polyurethane plugs from the human vas deferens occluded for up to 5 years. Int J Androl 1993;15:465–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]