Abstract

Patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) face a range of treatment options to improve survival and quality of life. An evidence-based shared decision-making tool (brochure, website, and recorded patient vignettes) for patients with new or worsening claudication symptoms was created using mixed methods and following the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) criteria. We reviewed literature and collected qualitative input from patients (n = 28) and clinicians (n = 34) to identify decisional needs, barriers, outcomes, knowledge, and preferences related to claudication treatment, along with input on implementation logistics from 59 patients and 27 clinicians. A prototype decision aid was developed and tested through a survey administered to 20 patients with PAD and 23 clinicians. Patients identified invasive treatment options (endovascular or surgical revascularization), non-invasive treatments (supervised exercise therapy, claudication medications), and combinations of these as key decisions. A total of 65% of clinicians thought the brochure would be useful for medical decision-making, an additional 30% with suggested improvements. For patients, those percentages were 75% and 25%, respectively. For the website, 76.5% of clinicians and 85.7% of patients thought it would be useful; an additional 17.6% of clinicians and 14.3% of patients thought it would be useful, with improvements. Suggestions were incorporated in the final version. The first prototype was well-received among patients and clinicians. The next step is to implement the tool in a PAD specialty care setting to evaluate its impact on patient knowledge, engagement, and decisional quality.

Keywords: claudication, patient centered, patient education, shared decision-making, peripheral artery disease (PAD)

Introduction

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is a burdensome condition that impacts an estimated 8.5 million Americans.1 It is an indicator of systemic atherosclerosis that results in lower extremity arterial blockages leading to impaired blood flow. Symptoms can present as exertional calf (or buttock or thigh) pain while walking that is relieved with rest (‘intermittent claudication’). PAD leg symptoms can severely affect a patients’ health status.2–4 In addition, 1-year cardiovascular event rates are estimated to be over 20% in patients with PAD, and mortality rates of 15–30% within 5 years of diagnosis have been noted.5–7

While cardiovascular risk management is recommended for all patients with PAD, multiple effective treatment options are available to relieve claudication symptoms.8,9 These options range from non-invasive strategies, such as pharmacologic treatment and supervised and home-based exercise therapy, to endovascular or surgical revascularization procedures. While there is no ‘gold-standard’ treatment for PAD symptom relief, less invasive options are recommended as a first-choice treatment and decisions to proceed with revascularization depend on the severity of symptoms, comorbidities, and response to previously tried non-invasive options.8 Importantly, the preferences and treatment goals of the patient are major factors when considering PAD treatment options.8

Ideally, patients with PAD receive education on available treatments, including the risks and benefits of each, to empower them to decide which treatment strategy most aligns with their personal goals and values. Achieving this vision requires developing tools for patients with new or worsening symptoms of claudication. After reviewing publicly available decision-making tools for PAD, we created an evidence-based PAD treatment decision aid for patients with mild to severe claudication symptoms (Rutherford Grade I)10 and evaluated its acceptability as a foundation for the broader integration of shared decision-making into the clinical care processes for patients with PAD.

Methods

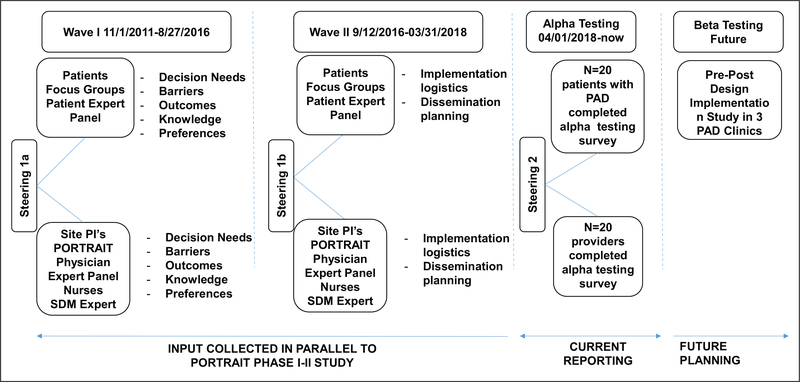

To develop the decision aid, we adhered to the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS).11 Qualitative input was collected from patient and clinician stakeholders in three waves (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline of the development process of the SHOW-ME PAD decision aid. PAD, peripheral artery disease; PI, principal investigator; SDM, shared decision making.

Wave I (November 1, 2011—August 27, 2016) was organized as part of the PORTRAIT study, which enrolled US patients with new or exacerbated PAD symptoms (Rutherford categories 1–3).12 Five patient focus groups (online supplemental Table 1) were conducted. Additionally, a patient expert panel and a clinician expert panel (a cardiologist, a vascular surgeon, and a vascular medicine specialist) were convened to provide perspectives on decisional needs, perceived barriers to PAD decision-making, preferred treatment outcomes, PAD knowledge, and preferences for decision-making. Input was also obtained from clinicians, including physicians and allied health professionals (n = 34). Following these meetings, a steering committee meeting (KS, JS, KS, CD, DS, and expert panel members) (Figure 1) was organized to integrate the collected feedback and make decisions for further study design.

In Wave II (September 12, 2016—March 31, 2018), the stakeholder groups provided input on decision aid implementation and dissemination logistics as well as planning priorities. We also recruited patients and community members from the Second Baptist Church in Kansas City, MO, and from the Diabetes Prevention Program in Kansas City, KS, to elicit their perspectives on formats and interpretability of medical information, followed by another steering meeting (#1b; Figure 1) to review the input and the design of the prototype decision aid with a graphic design and videographer team.

The latest clinical guidelines (only Class I recommendations) from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology13 provided the evidence base used to describe PAD, treatments, and outcomes.13

For the Alpha testing phase, the prototype decision aid was mailed to a convenience sample of 20 patients with PAD (Rutherford categories 1–3, recruited from the Saint Luke’s Health System vascular clinics in Kansas City, MO). The prototype decision aid was also sent to a convenience sample of 23 physicians and allied health professionals from Saint Luke’s Health System, Kansas City, MO; Yale University, New Haven, CT; University of Missouri, Columbia, MO; University Hospitals Cleveland, Cleveland, OH; University of Missouri Kansas City, Kansas City, MO; Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ; and Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, between April 1 and August 31, 2018. For the patient stakeholders, there were six recurrent patients between Wave I and Wave II stakeholder interactions. For the provider stakeholders, there were nine recurrent providers between Wave I and Wave II. Within Wave II, the same stakeholders reviewed multiple iterations of the materials throughout and provided continuous feedback, including the alpha testing survey. Patients and clinicians filled out a 44-item survey through REDCap,14 derived from previous decision aid frameworks (online supplemental Table 2)15,16 on the user-friendliness of the decision aid materials (the website, printed brochure, and discussion cards). The clinicians also evaluated the decision aid using the IPDAS quality criteria for decision aids.11 For the IPDAS quality criteria evaluation, we addressed items for which less than 75% of the reviewers felt that the criterion had been met. Following the Alpha testing and a steering meeting, revisions to the decision aid were integrated.

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Saint Luke’s Health System, Kansas City, MO, and Yale University, New Haven, CT. All enrolled patients provided informed consent. Focus group discussions were recorded, transcribed, and coded using descriptive content analysis until thematic saturation occurred. The transcripts were coded by a multidisciplinary team of nurses, a psychologist, an interventional cardiologist, and community-based participatory health researchers (KS, CD, NS, CF, CP, DS) using the methodology by Hahn.17 For each wave of focus groups, we kept interviewing stakeholders until we reached content saturation, meaning that no new themes emerged. The descriptive data obtained from the Alpha testing survey was generated through the reporting functionality of REDCap.

Finally, the SHOW-ME PAD decision tool was registered and listed in the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute shared decision aid database.18

Results

For Wave I (Figure 1), an overview of stakeholder characteristics and interactions are provided in the online supplemental Tables 1, 3, and 4. The identified decision needs were: symptom relief for PAD and finding the information that would fit patients’ needs. Perceived barriers included a lack of information, the quality of the patient—physician relationship, and variable information provided across different clinicians and care settings.

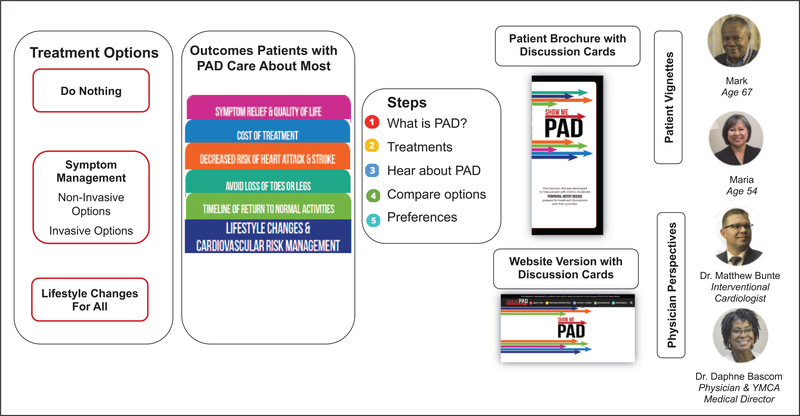

The following PAD treatment outcomes were identified as important: (1) rapid pain relief, (2) living longer, (3) improving quality of life, (4) cost of treatment, (5) avoiding loss of toes or legs, (6) timeline to return to normal activities, (7) decreasing risk of heart attack and stroke, (8) long-lasting symptom relief, and (9) avoiding a procedure or surgery. In steering meeting 1a, it was decided that the treatment decision support should focus on highlighting the evidence13 of two treatment pathways (or combinations thereof) for PAD symptom relief: a non-invasive pathway that included medications and supervised exercise therapy (SET) and an invasive treatment pathway that included endovascular and surgical options. The option of ‘do nothing’ was also included. Per the guidelines, lifestyle management for PAD is recommended for everyone, regardless of the treatment path(s) chosen to relieve the PAD symptoms (Figure 2, left panel). The following consolidated treatment outcomes were highlighted in the decision aid concept: (1) symptom relief and quality of life; (2) cost; (3) decreased risk of heart attack and stroke; (4) avoid loss of toes or legs; and (5) timeline of return to normal activities (Figure 2, middle panel).

Figure 2.

Original conceptual overview of the SHOW-ME PAD decision aid. PAD, peripheral artery disease. Note — This figure is in color online.

For Wave II (Figure 1), patients indicated that they wanted a variety of educational materials (video, paper, website) to meet their PAD treatment decision needs (online supplemental Table 4). The clinician stakeholders’ priority was that the decision aid materials be made available for review within and outside of the clinical setting, typically following a diagnostic test for PAD. By designing the process in this way, the patient would come in prepared and had identified questions they wanted to discuss with their clinician. The prototype decision aid resulted in a website (https://showme-pad.org) with patient stories summarized in videos (vignettes) and physician videos with treatment and outcomes information. In addition, different treatment pathway and outcomes information was summarized through discussion cards, with each card highlighting the PAD treatment goals and outcomes as established in Wave I. A paper version of the decision aid materials mirrored the website materials (Figure 2, right panel).

For the Alpha testing, patient and clinician characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. All patients and clinicians thought the information provided in the brochure was relevant, and that the brochure was easy to use (100% and 90.0%, respectively). Patients and clinicians agreed that the different treatments were presented in a balanced manner (brochure 87.5% and 85.0%, respectively; website 85.7% and 88.2%, respectively). When looking at aesthetics, 84.2% of patients and 94.7% of clinicians indicated the brochure looked visually attractive; 92.9% and 88.2%, respectively, thought the same for the website. Patients and clinicians thought that the language for both the brochure (94.4% and 100%, respectively) and the website (100% and 94.1%, respectively) was easy to understand. Risks of treatments were thought to be presented in a realistic way (range 83.3–92.3% for patients; range 90.0–100% for clinicians). Patients and clinicians agreed that the brochure (75% and 65.0%, respectively) and the website (85.7% and 76.5%, respectively) would be useful instruments for PAD decision-making. Of all the clinicians surveyed, 88.8% would recommend the decision aid in their own practice. While 40% of the clinicians thought the information in the brochure was too much, only 15% of the patients thought the information offered was too much. For the website information, a total of 25% of the patients thought the information was too much, and 26% of the clinicians thought there was too much information offered. Further reporting and details of the survey results are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Overview of patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristic | n = 20 |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 70 ± 12 |

| Female | 12 (60) |

| Race (n = 19 responses) | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 (0) |

| Black/African American | 7 (35) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0) |

| White | 12 (60) |

| Other | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0 (0) |

| Greater than high school education | 13 (65) |

| Married | 12 (60) |

| Full-time or part-time employed | 4 (20) |

| Living location | |

| Urban | 11 (55) |

| Suburban | |

| How long have you had PAD? (n = 19 responses) | |

| < 1 year | 1 (0.05) |

| 1–2 years | 4 (20) |

| 2–3 years | 2 (10) |

| ⩾ 3 years | 12 (60) |

| PAD stage | |

| Claudication | 10 (50) |

| Non-healing wounds | 6 (30) |

| Amputation | 4 (20) |

Data are presented as numbers (percentages), unless otherwise stated.

PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Table 2.

Overview of PAD clinician characteristics.

| Clinician characteristic | n = 23 |

|---|---|

| Specialist type | |

| Cardiologist | 8 (35) |

| Vascular surgeon | 2 (9) |

| Wound care specialist | 0 (0) |

| Internal medicine | 3 (13) |

| Other | 10 (44) |

| Years practicing | |

| 0–5 | 10 (44) |

| 6–10 | 4 (17) |

| 11–15 | 2 (9) |

| 16–20 | 0 (0) |

| 21 + | 7 (30) |

| Practice facility type | |

| Academic | 20 (87) |

| Non-academic | 3 (13) |

Data are presented as numbers (percentages), unless otherwise stated.

PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Table 3.

Alpha testing results.

| Evaluation criteria | Patients (n = 20) | Clinicians (n = 23) |

|---|---|---|

| BROCHURE EVALUATION | ||

| For the paper brochure, I think the amount of information is too much | ||

| Agree | 3 (15) | 8 (40) |

| Disagree | 17 (85) | 10 (50) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the brochure will do more harm than good | ||

| Agree | 1 (5) | 3 (15) |

| Disagree | 18 (90) | 16 (80) |

| Do not know | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the brochure contains information that can help a patient decide about PAD treatment | ||

| Agree | 20 (100) | 18 (90) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the information is relevant | ||

| Agree | 20 (100) | 20 (100) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| I think the paper brochure is easy to use | ||

| Agree | 20 (100) | 18 (90) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the different sections are presented in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 20 (100) | 18 (90) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the information is easy to understand | ||

| Agree | 19 (95) | 17 (85) |

| Disagree | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the different PAD treatments are explained in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 18 (95) | 16 (80) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 3 (15) |

| Do not know | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the pros and cons of PAD treatments are presented in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 19 (95) | 16 (84) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Do not know | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, the invasive treatment information is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 17 (90) | 17 (85) |

| No | 2 (11) | 3 (15) |

| The risks of invasive treatments in the paper brochure seem | ||

| Underestimated | 3 (17) | 2 (10) |

| Overestimated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Realistic | 15 (83) | 18 (90) |

| For the paper brochure, the non-invasive treatment information is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 18 (95) | 20 (100) |

| No | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| The risks of non-invasive treatments in the paper brochure seem | ||

| Underestimated | 3 (16) | 0 (0) |

| Overestimated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Realistic | 16 (84) | 20 (100) |

| Do you feel the information in the paper brochure and decision cards is balanced between invasive and non-invasive PAD treatment options? | ||

| Yes | 14 (88) | 17 (85) |

| No, slanted towards invasive | 1 (6) | 1 (5) |

| No, slanted towards non-invasive | 1 (6) | 2 (10) |

| I think the brochure looks visually attractive | ||

| Agree | 16 (84) | 18 (95) |

| Disagree | 1 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know | 2 (11) | 1 (5) |

| For the paper brochure, I think the font and font size are easy to read | ||

| Agree | 15 (79) | 14 (70) |

| Disagree | 4 (21) | 5 (25) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| How would you rate the paper brochure length? | ||

| Too long | 5 (26) | 5 (25) |

| Too short | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| Just right | 13 (68) | 14 (70) |

| How would you rate the amount of information shared in the paper brochure? | ||

| Too much | 4 (23.5) | 7 (35) |

| Too little | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0) |

| Just right | 12 (70.6) | 13 (65) |

| Overall, the paper brochure is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 17 (94.4) | 20 (100) |

| No | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) |

| The paper brochure is useful in decision making | ||

| Yes | 12 (75) | 13 (65) |

| Yes, with recommended improvements | 4 (25) | 6 (30) |

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| WEBSITE EVALUATION | ||

| For the website, I think the amount of information is too much | ||

| Agree | 4 (25) | 5 (26) |

| Disagree | 9 (56) | 8 (42) |

| Do not know | 3 (19) | 6 (32) |

| For the website, I think it will do more harm than good | ||

| Agree | 3 (19) | 2 (11) |

| Disagree | 10 (63) | 12 (63) |

| Do not know | 3 (19) | 5 (26) |

| For the website, I think it contains information that can help a patient decide about PAD treatment | ||

| Agree | 14 (88) | 14 (74) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 2 (11) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 3 (16) |

| For the website, I think the information is relevant | ||

| Agree | 14 (88) | 15 (79) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 4 (21) |

| I think the website is easy to navigate | ||

| Agree | 13 (81) | 14 (74) |

| Disagree | 1 (6) | 2 (11) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 3 (16) |

| For the website, I think the sections are presented in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 13 (81) | 14 (74) |

| Disagree | 1 (6) | 2 (11) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 3 (16) |

| For the website, I think the information is easy to understand | ||

| Agree | 13 (81) | 14 (74) |

| Disagree | 1 (6) | 1 (5) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 4 (21) |

| For the website, I think the different PAD treatments are explained in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 13 (81) | 12 (67) |

| Disagree | 1 (6.3) | 3 (17) |

| Do not know | 2 (13) | 3 (17) |

| For the website, I think the pros and cons of PAD treatment are presented in a clear manner | ||

| Agree | 13 (81) | 12 (63) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 3 (16) |

| Do not know | 3 (19) | 4 (21) |

| For the website, the invasive treatment information is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 11 (100) | 14 (82) |

| No | 0 (0) | 3 (18) |

| The risks of invasive treatment on the website seem | ||

| Underestimated | 1 (8) | 1 (6) |

| Overestimated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Realistic | 12 (92) | 16 (94) |

| For the website, the non-invasive treatment information is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 13 (93) | 17 (100) |

| No | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| The risks of non-invasive treatments on the website seem | ||

| Underestimated | 1 (8) | 1 (6) |

| Overestimated | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Realistic | 12 (92) | 16 (94) |

| Do you feel the information on the website is balanced between invasive and non-invasive PAD treatment options? | ||

| Yes | 12 (86) | 15 (88) |

| No, slanted towards invasive | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| No, slanted towards non-invasive | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| I think the website looks visually attractive | ||

| Agree | 13 (93) | 15 (88) |

| Disagree | 1 (7) | 0 (0) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| For the website, I think the font and font size are easy to read | ||

| Agree | 14 (100) | 13 (81) |

| Disagree | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Do not know | 0 (0) | 2 (13) |

| How would you rate the amount of information shared on the website? | ||

| Too much | 3 (21) | 2 (12) |

| Too little | 0 (0) | 3 (18) |

| Just right | 11 (79) | 12 (71) |

| Overall, the website is easy to understand | ||

| Yes | 11 (100) | 16 (94) |

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| The website tool is useful in decision making | ||

| Yes | 12 (86) | 13 (77) |

| Yes, with recommended improvements | 2 (14) | 3 (18) |

| No | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| The decision aid provides enough information for a PAD patient to decide on a treatment | ||

| Yes, for both versions | 15 (94) | 15 (83) |

| Yes, for only the paper brochure | 1 (6) | 0 (0) |

| Yes, for only the website | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No | 0 (0) | 3 (17) |

| For both versions, the decision card topics are | ||

| Well chosen | 14 (93) | 17 (94) |

| At least one needs to be removed | 1 (7) | 1 (6) |

| At least one needs to be added | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Do you feel the content of the brochure and website are consistent? | ||

| Yes | 15 (100) | 16 (100) |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Do you find the PAD Quiz and Your Preferences Matter helpful in PAD decision-making | ||

| Yes, for both versions | 12 (80) | 16 (89) |

| Yes, for only the paper brochure | 0 (0) | 1 (6) |

| Yes, for only the website | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| No | 3 (20) | 1 (6) |

| I would recommend the Show-Me PAD decision aid for PAD patients | ||

| Yes, for both versions | 16 (89) | |

| Yes, for only the paper brochure | 0 (0) | |

| Yes, for only the website | 1 (6) | |

| No, I would not recommend either | 0 (0) | |

| No, I do not recommend decision aids in general | 1 (6) | |

Data are presented as numbers (percentages).

PAD, peripheral artery disease.

Online supplemental Tables 4–6 provide an overview of all alpha testing stakeholder suggestions and the Steering 3 action items. The main change was the consolidation of the nine separate discussion cards (both for brochure and website) into a streamlined side-by-side overview of the pros and cons for each treatment modality. In direct response to the feedback that materials were containing too much information, we only focused on two patient-centered outcomes: symptoms and quality of life; and returning to usual activities. Generic cost information, tips, and resources for medical treatments were summarized underneath the decision aid. The decision aid was made central in the brochure as a fold out. The website was updated so that patients could choose to go straight to the decision aid, or they could review a 1.5-minute compilation video. Online supplemental Figure 1 provides an overview of the revised decision aid.

Discussion

Given the preference-sensitive nature of PAD treatments, having a reliable, objective, evidence-based decision-making tool is an important, currently unmet, need. To address this, we designed and tested a decision tool to assist patients and clinicians to make more informed, participatory decisions about PAD treatment. We worked intensely with patient and clinician stakeholders to design and alpha test a tool that would support patients with new or worsening symptoms of PAD in understanding and considering different treatment options for PAD symptom relief. Patients expressed interest in learning more about five different PAD treatment outcomes: (1) symptom relief and quality of life; (2) cost of treatment; (3) decreased risk of heart attack and stroke; (4) avoid loss of toes or legs; and (5) timeline of return to normal activities. These outcomes defined the framework for presenting levels of evidence for non-invasive and invasive treatment options for PAD symptom relief provided in a variety of modalities (website, videos, and printed materials) to facilitate the treatment discussion with the clinician, but also to be used as a resource to patients in preparation of their visit.

Overall, the current SHOW-ME PAD decision aid was well received and next steps for an update of the tool for implementation testing (beta testing) in routine clinical practice (PAD specialty setting) are being developed. To date, tools for shared decision-making in PAD have not been widely developed or studied. A decision aid has been developed by Healthwise,19 but it does not highlight the patient-centered aspects of outcomes following PAD treatment options and does not highlight specific benefits of individual evidence-based strategies, such as SET, whereas the SHOW-ME PAD tool focuses on all potential treatment options as well as the patient experience. With patients and clinicians, we co-created a platform that takes into account the latest evidence about all available treatment options and their outcomes for PAD symptom relief,13 as well as patients’ preferences with regards to treatment and potential outcomes that matter to them.20

Decision aids that facilitate shared decision-making have demonstrated the potential to be cost saving because less invasive options are often preferred by patients when given a choice; higher treatment satisfaction and knowledge are provided; and there is less decision conflict after the decision has been made.20,21 While there is no ‘gold-standard’ treatment for PAD, less invasive options are generally recommended as a first-choice treatment; however, personal preferences, quality of life considerations, or anatomical factors should also weigh into a treatment decision.8 Each of the treatment options has specific risks and benefits. Patients may not know the risks and benefits associated with each treatment and how these align with their treatment preferences and goals. Patient-centric tools like the SHOW-ME PAD decision aid could be used to better tailor decision-making with patients’ preferences and improve the quality of medical decision-making.

The next steps for the evaluation of the SHOW-ME PAD decision aid are designing and testing clinical workflows for implementation in a PAD specialty care setting. Testing of the tool is currently being conducted a pre-post design study22 in patients with new or worsening PAD symptoms who consult with a PAD specialty care clinic in the US. The study goals are to understand if a decision aid reduces ‘decisional conflict’ (i.e. uncertainty and insufficient support and information to make a medical decision) and increases patient knowledge of treatment options. Also, as SHOW-ME PAD is currently designed as a static tool (i.e. no individualized risk prediction for certain outcomes), further development is needed to integrate validated risk prediction models for relevant outcomes (e.g. risk of bleeding or developing acute kidney injury associated with peripheral angioplasty, health status outcomes), and integrate the newest results of comparative effectiveness research as evidence becomes available. Further testing of the decision aid in a randomized design is also anticipated to compare in the most valid method the benefits of shared decision-making in PAD.

Study limitations

While the study has adhered to the IPDAS evaluation criteria, and was conceptualized to be patient-centric, it does have limitations. The tool was designed for the PAD specialty care setting and primarily in academic settings. It is unclear whether it will be acceptable or effective in other settings. Given the use of convenience sampling for this alpha testing stage, validation in larger populations and geographies would be warranted to ensure wider generalizability. Patients with claudication and clinicians treating this condition were intensely involved throughout all phases of design and development of the decision aid. However, in the alpha testing phase, patients with more advanced expression of the disease (those with wounds or a history of amputation) also evaluated the decision aid and it is unclear whether their advanced disease process may have impacted the way they rated the materials. Furthermore, while we relied on the most recent guideline information, the body of comparative effectiveness research in PAD is still being built and, as evidence becomes available, shared decision-making platforms such as SHOW-ME PAD will need periodic updating.

Conclusion

The goal of SHOW-ME PAD is to make the existing evidence on treatment outcomes — focusing on health status outcomes that reflect the patients’ perspective — easily available to patients and clinicians, such that more informed, evidence-based, shared treatment decisions occur. This study serves as the foundation for future efforts to build shared decision-making platforms for patients with PAD facing important treatment decisions. We demonstrated the feasibility of this vision and gained important insights into the barriers and facilitators of implementing personalized shared decision-making tools in routine clinical care. The SHOW-ME PAD platform has the potential to reorganize care delivery to patients with PAD in a way that creates more value for the patient and society.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patient, physician, and allied health stakeholders, members of the graphic design team (Dustin Fann, Kristi Ernstig, Maggie Goldsborough, Brian Ellis), the patient and physician experts who helped with developing the patient and physician videos, and the patients who participated in our focus groups. We would like to thank the authors of the paper on ‘Development of a decision aid about fertility preservation for women with breast cancer in The Netherlands’ for allowing us to use their evaluation questions for the alpha testing of our study.16

Funding

Research reported in this manuscript was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (IP2 PI000753–01; CE-1304–6677), The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (VENI Grant No. 916.11.179), unrestricted grants from W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc. (Flagstaff, AZ) and Merck & Company, Inc. (Kenilworth, NJ). Dr Eric Secemsky is funded in part by NIH/NHLBI K23HL150290.

The funding organizations had no role in the design and conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The statements in this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee. All manuscripts for the PORTRAIT study are prepared by independent authors who are not governed by the funding sponsors and are reviewed by an academic publications committee before submission.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Mena-Hurtado is a consultant for Abbott, Cook, Cardinal Health, Bard, Boston Scientific, Gore, Optum Labs, and Medtronic. Dr Spertus owns the copyright for the KCCQ; has equity interest in Health Outcomes Sciences; has received consulting income from Novartis, Bayer, AstraZeneca, V-Wave, Corvia, and Janssen; has served on the Advisory Board for United Healthcare; and has served on the Board of Directors for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas City. Dr Smolderen is a consultant for Optum Labs and reports support through unrestricted research grants from Cardiva, Abbott, and Johnson & Johnson (for work unrelated to this study). The remaining authors report no relevant disclosures.

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03190382

Supplementary material

The supplementary material is available online with the article.

References

- 1.Allison MA, Ho E, Denenberg JO, et al. Ethnic-specific prevalence of peripheral arterial disease in the United States. Am J Prev Med 2007; 32: 328–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smolderen KG, Pelle AJ, Kupper N, et al. Impact of peripheral arterial disease on health status: A comparison with chronic heart failure. J Vasc Surg 2009; 50: 1391–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.deGraaf JC, Ubbink DT, Kools EJC, et al. The impact of peripheral and coronary artery disease on health-related quality of life. Ann Vasc Surg 2002; 16: 495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallin A, Bergqvist D, Fugl-Meyer K, et al. Areas of concern, quality of life and life satisfaction in patients with peripheral vascular disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2002; 24: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007; 297: 1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): A collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. Circulation 2006; 113: e463–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weitz JI, Byrne J, Clagett GP, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: A critical review. Circulation 1996; 94: 3026–3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (updating the 2005 guideline): A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 2020–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDermott MM, Fried L, Simonsick E, et al. Asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease is independently associated with impaired lower extremity functioning: The women’s health and aging study. Circulation 2000; 101: 1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutherford RB, Baker JD, Ernst C, et al. Recommended standards for reports dealing with lower extremity ischemia: Revised version. J Vasc Surg 1997; 26: 517–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulter A, Kryworuchko J, Mullen P, et al. Using a systematic development process. 2012 updated chapter A. In: Volk R, Llewellyn-Thomas H (ed) 2012 Update of the International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration background document, ipdas.ohri.ca/IPDAS-Chapter-A.pdf (2012, accessed 3 February 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smolderen KG, Gosch K, Patel M, et al. PORTRAIT (Patient-Centered Outcomes Related to Treatment Practices in Peripheral Arterial Disease: Investigating Trajectories): Overview of design and rationale of an international prospective peripheral arterial disease study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2018; 11: e003860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerhard-Herman MD, Gornik HL, Barrett C, et al. 2016 AHA/ACC guideline on the management of patients with lower extremity peripheral artery disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2017; 135: e726–e779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harmsen MG, Steenbeek MP, Hoogerbrugge N, et al. A patient decision aid for risk-reducing surgery in premenopausal BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: Development process and pilot testing. Health Expect 2018; 21: 659–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garvelink MM, ter Kuile MM, Fischer MJ, et al. Development of a decision aid about fertility preservation for women with breast cancer in The Netherlands. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 34: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn C. Doing qualitative research using your computer: A practical guide. London: SAGE, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Patient decision aids. Show me PAD, https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsumm.php?ID=1932 (2020, accessed 3 February 2021).

- 19.Healthwise. Peripheral Artery Disease. Should I have Surgery? https://www.healthwise.net/ohridecisionaid/Content/StdDocument.aspx?DOCHWID=ue4756 (2016, accessed 3 February 2021).

- 20.O’Connor AM, Wennberg JE, Legare F, et al. Toward the ‘tipping point’: Decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007; 26: 716–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arterburn D, Wellman R, Westbrook E, et al. Introducing decision aids at Group Health was linked to sharply lower hip and knee surgery rates and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012; 31: 2094–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.ClinicalTrials.gov. SHOWME-PAD (Peripheral Artery Disease), https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03190382?term=smolderen&rank=3 (2020, accessed 3 February 2021).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.