Abstract

Introduction

In simulation sessions using standardized patients (SPs), it is the instructors, rather than the learners, who traditionally identify learning goals. We describe co-constructive patient simulation (CCPS), an experiential model in which learners address self-identified goals.

Methods

In CCPS, a designated learner creates a case script based on a challenging clinical encounter. Topics that are difficult to openly talk about may be especially appropriate for the CCPS model. The script is then shared with an actor who is experienced working as an SP in medical settings. An instructor with experience in the model is involved in creating, editing, and practicing role play of the case. Following co-creation of the case, learners with no prior knowledge of the case (peers or a supervisor) interview the SP. The clinical encounter is followed by a group debriefing session.

Results

We conducted six CCPS sessions with senior trainees in child and adolescent psychiatry. Topics that are difficult to openly talk about may be especially appropriate for the CCPS model – without overt guidance or solicitation, the scripts developed by learners for this series involved: medical errors and error disclosure; racial tensions, including overt racism; inter-professional conflict; transphobia; patient-on-provider violence; sexual health; and the sharing of vulnerability and personal imperfections in the clinical setting.

Conclusion

CCPS provides an alternative multi-stage and multi-modal approach to traditional SP simulation sessions that can adapt iteratively and in real time to new clinical vicissitudes and challenges This learner-centered model holds promise to enrich simulation-based education by fostering autonomous, meaningful, and relevant experiences that are in alignment with trainees’ self-identified learning goals.

Introduction

Simulation-based education with standardized patients (SPs) has become widespread in health care, particularly as a method to improve experiential learning environments.1-4 Despite its broad uptake as an educational tool, existing models of patient-based simulation remain primarily instructor-driven. Few studies in the simulation literature have designed training that explicitly supports trainees’ role in self-regulating their own learning experiences. Simulation-based learning stands to benefit from embracing an approach that makes explicit the ‘shared responsibility between the trainee and the instructional designer’.5

In preparing a simulation session using SPs, educators usually begin by setting clear objectives that provide guidance to achieve the desired learning outcomes.4 Objectives are in turn identified based on national guidelines (such as those from the ACGME6 or specialty societies), or through needs assessments of the learners or the curricular content. In an effort to engage with the challenges that learners actually encounter in their personal clinical practice, Schweller and colleagues7 described a model of simulation ‘turned upside down’. In their approach, residents brought their challenging clinical situations to a simulation session, in which the educator (i.e. a senior supervisor), now ‘in the shoes’ of the resident, played out the scenario with an SP. Critically, it was the learners who identified and wrote, together with professional actors, the clinical situations with which they struggled, and later articulated the learning gaps and established objectives. Through this approach, learners could see, in a controlled simulation setting, how their senior supervisors would deal with similar challenges in practice. Moreover, learners’ self-directed learning8-10 could be enhanced by incorporating their clinically relevant situations into simulated scenarios.

The co-constructive patient simulation (CCPS) model

Seeing the potential that such an ‘upside down’ approach could have on simulation with SPs, we replicated, expanded, and refined the work by Schweller et al7,11,12 into a co-constructive patient simulation (CCPS) model. In the context of customization to a learner’s specific needs, CCPS builds on the ‘training on the job’ and ‘dramatic role playing’ approaches, respectively used to enhance communication and emotional awareness skills in patient simulation, as described by Rethans et al.13 CCPS provides an opportunity for participants to collectively practice the six principles of active learning described by Brookfield14 as essential for a teaching-learning transaction to be successful: voluntary participation, respect among learners, collaboration, praxis, reflection, and nurturance of a self-directed, empowered adult. The CCPS model also uses best practices from a flipped classroom approach,15-17 in which the time shared with learners is used to maximize practical application, discussion and interaction, while offloading traditional content delivery into time allotted for case preparation.

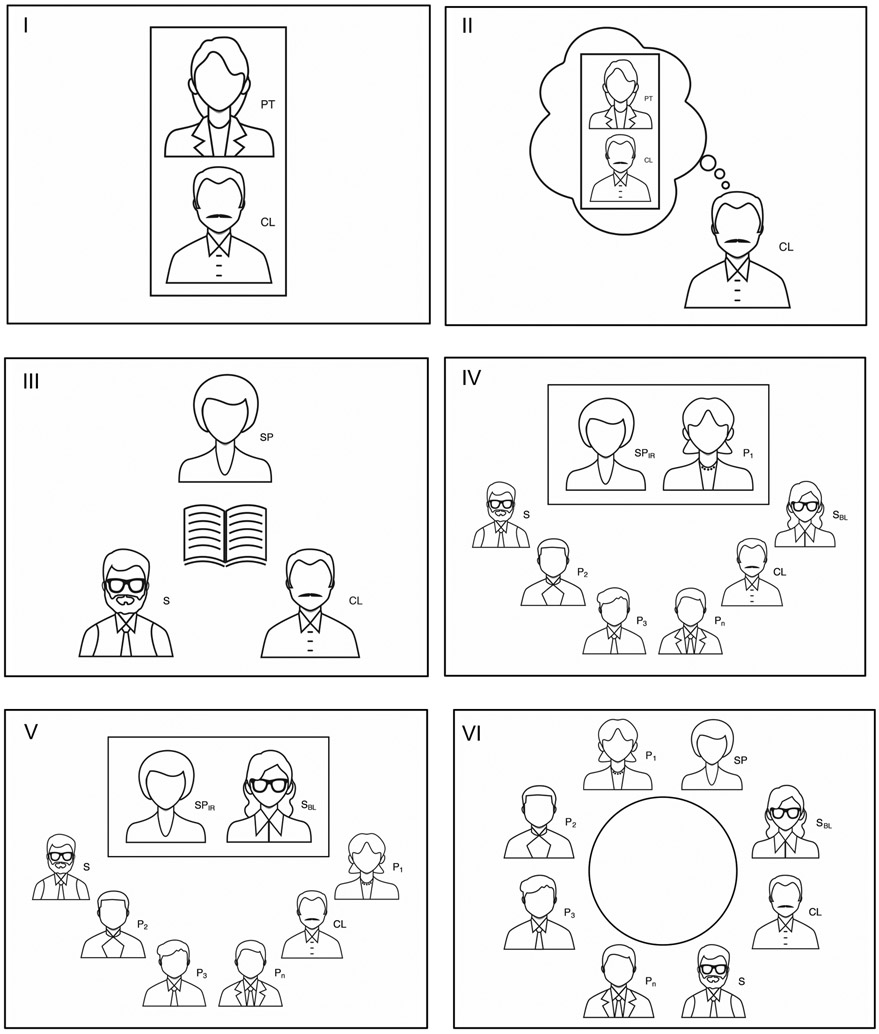

In the CCPS model, a designated learner (hereafter the ‘clinician’) creates a case script based on a challenging clinical encounter faced during training or clinical practice, and this is used by an SP in a similar clinical setting.7,18,19 A supervisor with experience in the CCPS model is involved in creating, editing and practicing role play of the simulated case. During the preparation of the case, the learning goals are jointly elaborated and refined by the triad of clinician, supervisor, and actor. Case preparation includes a rehearsal, during which the SP can optimize the accuracy of their portrayal, and the clinician has an opportunity to re-play and further reflect on the challenging scenario. In this context, the clinician, the supervisor and the SP are collaborators, in that only the three of them know the specific details of the case. Next, a fellow learner (a peer or blinded supervisor) is provided a ‘door note’ with brief background information of the case, before interviewing the SP. The clinical encounter is followed by a group debriefing session involving all learners: beginning with the clinicians’ experiences, followed by the accounts of the clinician and peer learners, and ending with the de-rolled SP. The model can be divided into six distinct phases, as depicted in Figure 1 and as we elaborate in an applied case example (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, in which we outline the development of a co-constructive patient simulation session.)

Figure 1. Co-constructive patient simulation model.

Co-constructive patient simulation phases: I. Clinical encounter between clinician [CL] and patient [PT]; II. Reflection. CL reflects back on the index encounter(s) and starts developing a script; III. Script writing. CL finalizes the script, working in close collaboration with a simulated patient [SP] and a supervisor [S]; IV. Simulated encounter. A first peer [P1] interviews the SP-in-role [SPIR], while other peers [P2-n] and supervisors [depicted wearing glasses] observe the encounter; V. Simulated encounter with blinded supervisor [SBL]. In a variation of phase IV, the interviewer is a different supervisor, not involved in phase III, and as such, blind to the clinical script; and VI. Debriefing. All participants take part in a debriefing session moderated by S; P1 is invited to share first, and CL and SP (de-rolled) contribute last. Note: the rectangular enclosures represent the confidential consultation spaces in which clinical encounters take place.

We developed the CCPS model informed by two main theoretical frameworks. First, self-regulated learning (SRL), which allows learners to have agency on their personal learning trajectories.20,21 Second, critical pedagogy, which focuses on establishing a democratic and non-hierarchical learning environment that invites reflection-toward-action on real-world problems extracted from the learners’ context. 22,23

Methods

Participants and Session Planning

We piloted the CCPS model during six sessions conducted at one-month intervals between November 2019 and May 2020. Participants were physicians enrolled in the final year of their ACGME-accredited fellowship program in child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP) at the Child Study Center of the Yale School of Medicine. In collaboration with the fellowship program’s training director, the project was designed to provide a formative educational opportunity. As such, it was intended to consolidate and refine advanced communication, diagnostic and psychotherapeutic skills gained during postgraduate training in psychiatry residency and CAP fellowship.

A preparatory session took place two months prior to the first session in order to re-acquaint fellows to working with SPs (including through an interactive experience with an SP), and to review in detail the goals, specifics details, logistics, and expectations for the project), including: a) Guidelines for establishing learning objectives24 and writing scripts25 for SP case preparation; and b) Guidelines for effective facilitation26 and debriefing.27-30 All fellows in the graduating class had the opportunity to participate during dedicated education time in the activity and to serve at least once in the different roles of clinician, interviewer, and debriefing group participant. As a capstone project designed to prepare the fellows’ transition into independent practice, the CCPS sessions took place during the months leading to their graduation. This activity was provided as a complement to their existing educational training.

Each session required a mode of six hours toward completion: 1) an estimated two hours for case preparation and scriptwriting; 2) two hours for editing, case clarification, role-play and script finalization with the SP and supervisor; and 3) two hours for the simulation session itself. SPs were compensated at a standard institutional rate of $32/hour for their time in the latter two components. Faculty members participated as part of their supervisory and educational responsibilities and were not compensated separately. Several trainees, who needed additional writing support from our research collaborators, required more time than the allotted four hours for writing and editing.

Outcomes and Analyses

We asked all participants to evaluate the two components of each session: interviews and debriefing. For each of the two, we asked about perceptions on how challenging and how frustrating each component had been using as anchors: ‘not at all’, ‘a little’, ‘just right’, ‘a lot’, and ‘way too much’. We next asked for ratings on five categories for the overall experience: 1) conduciveness to learning and 2) self-reflection; 3) effectiveness at getting into another person’s experience; 4) relevance and applicability to practice and training; and 5) realism in the SP’s portrayal of the patient. For these five items we used as anchors: ‘Not effective at all’, ‘slightly effective’, ‘moderately effective’, ‘very effective’, and ‘extremely effective’. Finally, we provided space for optional free-text comments from participants.

All participants completed evaluations through their preferred, WiFi-enabled personal devices during the last 10 minutes of each CCPS session. We collected information securely through Qualtrics (Provo, UT), and analyzed data using SPSS version 25 (Armonk, NY). We used the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test to compare ratings across sessions and between roles. Having found no differences (p>0.05 for all comparisons), we go on to present data descriptively as raw percentages. We did not conduct any other inferential statistics.

Ethics Approval

We obtained institutional review board approval from the Yale Human Investigations Committee (Protocol # 2000026241). Trainees were encouraged to participate but informed that their participation was neither mandatory nor relevant to their fellowship performance evaluation. They were aware that sessions would be conducted as part of a research project, and that all interviews and debriefing sessions would be audiotaped, transcribed and deidentified toward a subsequent qualitative study. All participants consented to participate in the study.

Results

We invited all twelve graduating CAP fellows in the class of 2020 to participate, with 11 (92%) of them joining. Other participants included seven different SPs (one for each session, except for the final one, which involved two SPs for a father-son scenario), and four supervisors. The latter included three individuals not previously known to the trainees: a physician with expertise in medical education and no formal training in psychiatry (MC), a psychiatrist with experience working with SPs (DA), and an expert in narrative medicine (IW). The fourth, a child psychiatrist and medical educator well known to the fellows as their supervisor and associate training director (AM), served as blinded interviewer in two of the six sessions. Each of the six sessions had a median of 13 participants (range, 11-14); fellows attended a median of five sessions each (range, 3-6).

Topics that are difficult to openly talk about proved especially appropriate for the CCPS model: without overt guidance or solicitation, the scripts developed by learners in this series involved medical errors and error disclosure; racial tensions, including implicit bias and overt racism; inter-professional conflict; transphobia; patient-on-provider violence; sexual health; and the sharing of vulnerability and personal imperfections in the clinical setting.

Upon completion, participants rated each of the six sessions (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, for their evaluation of the co-constructive patient simulation sessions.) Participants scored the sessions highly overall, with 94% of ratings in the ‘very effective or ‘extremely effective’ categories. There were no quantitative differences between sessions with or without a blinded supervisor participating as an interviewer.

Free-text comments, like the select ones included Table 1, provide a textured sense of the participants’ reception of the CCPS model. We organized feedback into five thematic areas: 1) regarding the sessions overall (e.g. ‘how could we not have this in our training?’); 2) around peer interactions (e.g. ‘so great to see our colleagues deal with tough situations’); 3) by and about the professional actors (e.g. ‘most interesting experience I’ve had to date as an SP’); 4) opportunities for reflection (e.g. ‘one vital part of re-humanizing medical education’) and 5) critiques and recommendations (‘could replicating the case with a faculty expert…reinforce content?’)

Table 1.

Participants' select free-text comments on co-constructive patient simulation sessions

| Theme | Participant | Session | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | P 1 | 6 | A truly incredible learning experience and one of the most meaningful and wholehearted during my academic career. I believe this model has the potential to form one vital part of re-humanizing medical education. |

| P 2 | 4 | The debriefing session was safe and engaging, and the conversation was free and meaningful. | |

| P 3 | 3 | I left thinking that this was such a fantastic experience, how could we NOT have this in our training? | |

| Peers | P 4 | 1 | It was so great to see how our colleagues deal with tough situations. That's not something we really ever get the chance to do. |

| P 5 | 4 | The best moment for me was when one of the interviewers forgot what time of day it was, because this was very human. It reminded me that we doctors are human, even if patients may experience us as special and incapable of making mistakes. Hopefully, in those moments, I can still join with the patient rather than beat myself up for not being perfect. | |

| Actors | P 6 | 1 | An actor can be only as good as the writing she is working off of. This actor was superb, and I suspect this had just as much to do with the actor as with the underlying hard work that went into the script. Thank you all! |

| SP 1 | 3 | This was an extremely illuminating experience for me as an actor. I found both interviewers to be deeply compassionate and thoughtful in their approaches. I wanted to be intentional about how I was able to best serve the character and backstory we co-wrote, while also allowing myself to be completely open and responsive to their energies and their words. | |

| SP 2 | 6 | Thanks again for selecting me to portray one of the roles in this event. In total it was the most interesting experience I've had to date as an SP. | |

| Reflection | SW 1 | 5 | I have learned so much. From the actors, from my fellow learners, from being on both (all by now!) sides of the exercises, from the candor and depth and sincerity of everyone's contributions. |

| P7 | 5 | This simulation welcomed vulnerability on both sides, but also challenged me to be patient. These interactions bring me back to why I chose psychiatry. To be with the patient, meet them where they are, and as taught in Circle of Security, to serve as a possible base and haven for the patient. It reinforced the importance of body language and how the unspoken can be even louder than words. | |

| Critique | P8 | 3 | It would interesting, if timing and programming allowed, to see one person do the full 40 minutes. Either way, a wonderful experience. |

| P9 | 6 | I loved the pairing of this lecture with the content lecture that followed. I wonder if recording a mini interview (<10 minutes) replicating the case but with a faculty expert addressing the subject could be incorporated into a reinforcing content lecture. | |

| P10 | 1 | Even though this was presented as not being a "gotcha!" type scenario, it ended up feeling that way. The patient actor - granted with no psychiatric background, so we wouldn't expect him to know how our job works - came off as lecturing us briefly about how we didn't figure out his secret. Otherwise, a good learning experience. It was also great to see how our colleagues interview in tough situations. That's not something we really ever get the chance to do. |

Abbreviations: P = peer; SP = standardized patient; SW = script writer.

Discussion

Co-constructive patient simulation (CCPS) is a new approach that redesigns traditional standardized patient use in medical education to shift the tasks of goal-setting and script-writing from instructors to a shared responsibility with learners. We were able to implement this model in a series of six simulations, conducted in the clinical field of child and adolescent psychiatry (CAP). Although our selection of CAP as a discipline was arbitrary and based on convenience sampling and our particular field of expertise, we were deliberate in our selection of learners. Specifically, we explicitly targeted as learners advanced trainees approaching graduation from fellowship and transition into ‘real world’ practice.8,10 The scenarios that the learners developed were clinically, cognitively and emotionally challenging, and based on situations they had faced and struggled with during their years of training. Of note, even fellows without a declared interest in medical education or academic writing were successful in creating evocative and realistic cases grounded in specific learning objectives. To that end, the availability of scripts from earlier sessions proved useful, with case writing and directions to actors becoming more standardized and consistently structured as time went on.

In keeping with self-regulated learning (SRL) theory,20,21 in the CCPS model learners had full discretion in the selection of their case(s) and of those issues they found clinically challenging in practice. Case preparation, interview and debriefing sessions in which learners broke complex interactions into meaningful pieces helped deconstruct the source of what they found taxing.31,32 and to place their struggles into a broader educational context of deliberate practice.33,34

Informed by the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire’s seminal work Pedagogy of the Oppressed,22,23 critical pedagogy seeks to break common hierarchical divides between senior and junior, teacher and taught, or between supervisor and learner — providing instead a horizontal ‘two-way street’ in which there is a virtuous cycle of mutual learning, curiosity, and growth.22,35 By placing supervisors in the same ‘hot seat’ as their trainees (a concept first introduced into psychodrama by Moreno and Perls),36 CCPS engenders a horizontal disruption of traditionally vertical hierarchies and fixed educational roles, which can hinder collaboration and community formation.

Framing our methodology as a co-constructive process integrates two additional key theoretical strands in the literature. First co-constructivism, as defined in the teaching and pedagogy literature, speaks to the collaborative learning process of co-creating, negotiating, and maintaining meaning through self-reflection and dialogue in a classroom.37 Second, narrative co-construction draws on narrative theory to describe the shared sense-making, structure, and story-building between, for instance, a psychotherapist and their patient38 or between two spouses navigating the treatment course of an illness.39,40 In the health and medical humanities, however, narrative co-construction primarily signifies the clinical encounter between physicians and their patients. Specifically, the physician’s task of close-listening to the patient to co-author their illness narrative and diagnosis to both center patient agency and remediate pre-existing asymmetries of power and expertise.41,42 With the exception of MacKenzie (2018),43 who advocates for the use of co-construction in simulation for occupational therapists, no research and instructional design (ID) in medical education has explored the potential to utilize narrative co-construction of a case study for patient simulation between a learner and an ID. Much like the clinical encounter, the learner’s and instructor’s careful co-authoring of a case-study, written as a composite of the learner’s difficult experiences, humanizes the professional relationship, complicates power dynamics, and fosters an open mutuality of collaboration and learning.

Given the model’s conduciveness to self-reflection and iterative skill-building, CCPS is particularly well suited to address, practice, and refine higher-order clinical skills with exacting emotional, affective or cognitive demands. By providing a space that is emotionally supportive and educationally sound, by developing cases that ‘ring true’ to the learners’ experience, and by providing a setting in which learners can witness a ‘do-over’ and debrief previously challenging or overwhelming experiences, CCPS can facilitate the refinement of critical skills and model collaborative inquiry. The input that the clinician receives in real time during the simulation —as well as in planning ahead toward it— offers a unique opportunity to reimagine the original predicament in new ways toward gaining knowledge, perspective, and mastery. The CCPS approach provides an opportunity for deep experiential learning. For experts, the horizontal nature of this approach encourages a greater appreciation of the distinct struggles of their learners, which might otherwise remain undisclosed. Equally, learners can gain from a shared and self-directed educational activity in a way that traditional methods (such as observation across a one-way mirror, review of videotapes, traditional clinical supervision,38 or paper-and-pencil exams) cannot. The CCPS approach thus puts into practice core principles of self-regulated learning.

Critiques articulated by the learners in their free text feedback included one interviewer feeling like the exercise was a ‘gotcha!’ situation. This comment was provided after the first session, and as such may reflect the learner becoming acquainted with a new model. However, this comment is worth pointing out, as we went on to emphasize that for our sessions’ purpose, the overall goal was about the process of interaction and engagement (in this case with an off-putting, minimizing, and challenging patient). Equally, during the debrief of the lead instructor’s first experience in the ‘hot seat’, he noted that he wished he had been given a more challenging case to model failure for the learners. However, one learner noted the advantages of witnessing the expertise of her supervisor, having never had a similar learning opportunity during her medical training. Being both explicit in our overall learning goals and open to reframing intended learning outcomes proved helpful in subsequent sessions and should be addressed early on by those considering to adapt or replicate the CCPS model.

Even as we implemented this model using psychiatric scenarios, we recognize that the seminal work by Schweller et al7,11,12 was first introduced to address specific challenges in internal medicine. Thus, we consider the CCPS approach to be discipline-independent and believe it can be meaningfully incorporated into any branch of medicine, nursing or the health professions broadly defined. We view CCPS as a vital precursor and catalyst to the work of narrative co-construction in the clinical encounter, which lies at the core of the field of narrative medicine,44 alongside field-wide attempts to support the wellbeing and professional development of trainees.

We recognize several limitations, as well as challenges ahead. First, this report does not include qualitative analyses of the planning, interview and debriefing sessions; we will report these separately, as they are extensive and more narrowly relevant to psychiatric practice. Second, except for the sixth session, all of our simulations involved a single actor. Since clinical situations often involve several interacting individuals, future adaptations of the model may explore these added layers of complexity. Third, none of our SPs was underage, a notable limitation when considering pediatric cases. Even as children can be played by young adult actors, we are exploring ways of incorporating child actors into future scenarios.45 Equally, for cases that center on the use of instrumentation or devices, the model would need mixed simulations that integrate actors with medical equipment. Finally, recognizing that we developed sessions for trainees about to complete their fellowship, we don’t mean to imply that the CCPS model could not be appropriate for more junior learners. Indeed, the opportunity to observe and imitate the behaviors and approaches of others and to learn to negotiate and construct meaning can prove critical in early stages of education.46

In summary, co-constructive patient simulation offers a novel approach to engage learners in a way that equally values the cultivation of their professional competencies alongside a compassionate reckoning with their challenges during medical education. The model seeks to right a balance, moving from the confined terms of teacher and taught to a practice of shared learning guided by the specific needs of the learners themselves, rather than the pedagogical assumptions of their instructors. The model provides, in a psychologically supportive environment, a real-world alternative to traditional supervision and training, and one that can adapt iteratively and in real time to emergent vicissitudes and challenges faced by clinicians. CCPS is a learner-centered approach to simulation that fosters lifelong, autonomous, meaningful and relevant learning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the contributions of the professional actors, the logistic support of Barbara Hildebrand at the Teaching and Learning Center, and the learners’ engaged participation.

Funding Sources

Supported by the Riva Ariella Ritvo Endowment at the Yale School of Medicine, and by NIMH R25 MH077823, ‘Research Education for Future Physician-Scientists in Child Psychiatry’.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards / Ethical Considerations

The Yale Human Investigations Committee approved the study (Protocol #2000026241)

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Rosen KR. The history of medical simulation. J Crit Care. 2008;23(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2007.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qayumi K, Pachev G, Zheng B, et al. Status of simulation in health care education: an international survey. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014:5–457. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S65451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.May W, Park JH, Lee JP. A ten-year review of the literature on the use of standardized patients in teaching and learning: 19962005. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):487–492. doi: 10.1080/01421590802530898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleland JA, Abe K, Rethans JJ. The use of simulated patients in medical education: AMEE Guide No 42 1. Med Teach. 2009;31(6):477–486. doi: 10.1080/01421590903002821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brydges R, Manzone J, Shanks D, et al. Self-regulated learning in simulation-based training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Educ. 2015;49(4):368–378. doi: 10.1111/medu.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (AACGME). Common program requirements. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements. Published 2020. Accessed August 22, 2020.

- 7.Schweller M, Ledubino A, Cecílio-Fernandes D, de Carvalho-Filho MA. Turning the simulation session upside down: the supervisor plays the resident. Med Educ. 2018;52(11):1203–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morris TH. Adaptivity through self-directed learning to meet the challenges of our ever-changing world. Adult Learn. 2019;30(2):56–66. doi: 10.1177/1045159518814486 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li ST, Paterniti DA, Co JPT, West DC. Successful self-directed lifelong learning in medicine: a conceptual model derived from pediatric residents. Acad Med. 2010;85(7):1229–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murad MH, Coto-yglesias F, Varkey P, Prokop LJ, Murad AL. The effectiveness of self-directed learning in health professions education: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2010;44:1057–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03750.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schweller M, Costa FO, Antônio MA, Amaral EM, de Carvalho-filho MA. The impact of simulated medical consultations on the empathy levels of students at one medical school. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):632–637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schweller M, Ribeiro DL, Wanderley JS, de Carvalho-Filho MA. Simulated medical consultations with standardized patients: In-depth debriefing based on dealing with emotions. Rev Bras Educ Med. 2018;42(1):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rethans JJ, Grosfeld FJM, Aper L, et al. Six formats in simulated and standardized patients use, based on experiences of 13 undergraduate medical curricula in Belgium and the Netherlands. Med Teach. 2012;34(9):710–716. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.708466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brookfield S Understanding and Facilitating Adult Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin JE, Roth MT, Glatt DM, et al. The flipped classroom: A course redesign to foster learning and engagement in a health professions school. Acad Med. 2014;89(2):236–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Flaherty J, Phillips C. The use of flipped classrooms in higher education: A scoping review. Internet High Educ. 2015;25:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: A meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1144-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gwin T, Villanueva C, Wong J. Student developed and led simulation scenarios. Nurs Educ Perspect. 2017;38(1):49–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis KL, Bohnert CA, Gammon WL, et al. The Association of Standardized Patient Educators (ASPE) Standards of Best Practice (SOBP). Adv Simul. 2017;2(10):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dornan T, Hadfield J, Brown M, Boshuizen H, Scherpbier A. How can medical students learn in a self-directed way in the clinical environment? Design-based research. Med Educ. 2005;39(4):356–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Houten-Schat MA, Berkhout JJ, van Dijk N, Endedijk MD, Jaarsma ADC, Diemers AD. Self-regulated learning in the clinical context: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1008–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freire P Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garavan M Opening up Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. In: O’Donovan O& FD,ed. Mobilising Classics - Reading Radical Writing in Ireland. Manchester University Press; 2010:123–139. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee IS. INACSL Standards of Best Practice: SimulationSMOutcomes and Objectives. Clin Simul Nurs. 2016;12:S13–S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2016.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDermott DS, Sarasnick J, Timcheck P. Using the INACSL SimulationTM Design Standard for Novice Learners. Clin Simul Nurs. 2017;13(6):249–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2017.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Committee IS. INACSL Standards of Best Practice: Simulation SM Facilitation. Clin Simul Nurs. 2016;12:S16–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2016.09.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Committee IS. INACSL Standards of Best Practice: Simulation SM Debriefing. Clin Simul Nurs. 2016;12:S21–S25. doi: 10.1016/j.ecns.2016.09.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grant VJ, Robinson T, Catena H, Eppich W, Cheng A. Difficult debriefing situations: A toolbox for simulation educators. Med Teach. 2018;40(7):703–712. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1468558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eppich W, Cheng A. Promoting excellence and reflective learning in simulation (PEARLS): Development and rationale for a blended approach to health care simulation debriefing. Simul Healthc. 2015;10(2):106–115. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavares W, Eppich W, Cheng A, et al. Learning conversations: an analysis of their theoretical roots and their manifestations of feedback and debriefing in medical education. Acad Med. 2019:1. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000002932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandomkar R, Sandars J. Clearing the confusion about self-directed learning and self-regulated learning. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):862–863. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1425382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keskitalo T, Ruokamo H, Gaba D. Towards meaningful simulation-based learning with medical students and junior physicians. Med Teach. 2014;36(3):230–239. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.853116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):706–711. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duvivier RJ, Van Dalen J, Muijtjens AM, Moulaert VR, Van Der Vleuten CP, Scherpbier AJ. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of clinical skills. BMC Med Educ. 2011;11(1). doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-11-101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Carvalho-Filho MA. Medical Education Empowered by Theater (MEET). Acad Med. 2020. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pugh M Pull up a chair. Psychologist. 2017;30(7):42–46. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reusser K Co-Constructivism in Educational Theory and Practice. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lieblich A, McAdams DP, Josselson R. Healing Plots: The Narrative Basis of Psychotherapy (The Narrative Study of Lives). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radcliffe E, Lowton K, Morgan M. Co-construction of chronic illness narratives by older stroke survivors and their spouses. Sociol Heal Illn. 2013;35(7):993–1007. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hersh D “Hopeless, sorry, hopeless”: co-constructing narratives of care with people who have aphasia post-stroke. Top Lang Disord. 2015;35(3):219–236. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0000000000000060 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Charon R, Dasgupta S, Hermann N, et al. The Principles and Practice of Narrative Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gowda D, Curran T, Khedagi A, et al. Implementing an interprofessional narrative medicine program in academic clinics: feasibility and program evaluation. Perspect Med Educ. 2019;8(1):52–59. doi: 10.1007/s40037-019-0497-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacKenzie DE, Collins KE, Guimond MJ, et al. Co-constructing simulations with learners: roles, responsibilities, and impact. Open J Occup Ther. 2018;6(1). doi: 10.15453/2168-6408.1335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milota MM, van Thiel GJMW, van Delden JJM. Narrative medicine as a medical education tool: A systematic review. Med Teach. 2019;41(7):802–810. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1584274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Budd N, Andersen P, Harrison P, Prowse N. Engaging children as simulated patients in healthcare education. Simul Healthc. 2020;15(3):199–204. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0000000000000452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grusec JE. Social learning theory and developmental psychology: the legacies of Robert Sears and Albert Bandura. Dev Psychol. 1992;28(5):776–786. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.28.5.776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.