Abstract

Dupilumab is the only biologic therapy currently approved in Europe and the United States for severe atopic dermatitis in patients 6 years of age or older. Off-label use is rationalized in younger children with severe atopic dermatitis. Decisions about vaccination for children on dupilumab are complex and depend on both the child’s current treatment and the type of vaccination required. To achieve consensus on recommendations for vaccination of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis treated with or planning to start dupilumab, a review of the literature and a modified-Delphi process was conducted by a working group of 5 panelists with expertise in dermatology, immunology, infectious diseases and vaccination. Here, we provide seven recommendations for vaccination of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis treated with or planning to start dupilumab. These recommendations serve to guide physicians’ decisions about vaccination in children with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab. Furthermore, we highlight an unmet need for research to determine how significantly dupilumab affects cellular and humoral immune responses to vaccination with live attenuated and inactivated vaccines.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-021-00607-6.

Key Points

| Decisions about vaccination for children on dupilumab are complex and depend on both the child’s current treatment and the type of vaccination required. |

| Pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis on treatment with dupilumab can safely receive inactivated vaccines, whereas live attenuated vaccines, including boosters, should be avoided or carefully considered on an individual basis and with the involvement of appropriate pediatric subspecialists until further evidence demonstrates their safety. |

Introduction

Increasing use of dupilumab for atopic dermatitis [1] in younger and younger children has stimulated new questions about immunization. Immunization is the process of acquiring protective immunity from the vaccine agent and should be distinguished from “vaccination,” which is the act of administering a vaccine. The former may occur, or not, depending on the recipient’s capacity to elicit an optimal immune response to the vaccine [2].

Atopic dermatitis (AD) affects predominantly young children, with most patients presenting within the first 5 years of life. The recent approval of dupilumab in children as young as 6 years of age and its off-label use in even younger children raise the dilemma of how to safely immunize pediatric patients on dupilumab [3].

Dupilumab is a human immunoglobulin (Ig)G4 monoclonal antibody that blocks the α-subunit shared by the types I and II receptor complexes for interleukin-4 (IL-4) and IL-13, decreasing signaling by these two cytokines [4, 5]. It is the only systemic treatment currently licensed to treat severe AD in children aged 6–11 years and moderate-severe AD in adolescents and adults by the US Food and Drug Administration [6, 7]. Its efficacy and safety profiles have been demonstrated in several studies and have been consistent among these age groups (see the electronic supplementary material) [1, 8–13].

Public health agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) encourage physicians to ensure adequate vaccination of immunocompromised patients on a case-by-case basis to avoid vaccine-preventable infections [14, 15]. We followed a modified-Delphi process to reach consensus on recommendations for vaccination of pediatric patients with AD currently on or planning to start dupilumab.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

A literature search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for systematic reviews to answer the research question “What is the safety of vaccinations in pediatric patients taking dupilumab for AD?” A research librarian and an MD, both independent of the consensus panel, ran search strategies in Medline and Embase. The last search was run on February 2, 2020. Two researchers (SMC and SD) independently screened titles and abstracts for relevance. If an article was relevant to the research question, the full text was reviewed to determine if it met eligibility criteria (see the electronic supplementary material). Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion. Reference lists from relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional relevant studies. As no search results met the eligibility criteria, a second literature search was performed on February 2020 in Medline for articles on live attenuated and inactivated vaccines in pediatric AD patients and on pediatric patients receiving biologics, national and international guidelines on vaccination of immunocompromised pediatric patients, and dermatologic guidelines for children with AD (see the electronic supplementary material).

A detailed review of the search results along with the full references was sent to the panelists in advance of the meeting.

Expert Working Group

The working group included members with expertise in the fields of dermatology (SMC, MR, and MK), pediatric dermatology (MR), immunology (LMF and MK), and infectious diseases (CMC).

Two participants (SMC and MR) developed the seven initial statements that were circulated and revised based on feedback received (MK) before the consensus meeting.

Consensus Meeting

The consensus meeting was conducted using a modified-Delphi method in which a physical meeting took place on March 12, 2020. The study followed the Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies (CREDES) [16]. The meeting was chaired by one moderator [5] and had two rounds (see the electronic supplementary material). A detailed overview of the process can be found in the electronic supplementary material. An online poll created using Poll Everywhere (San Francisco, California) with a 5-point Likert scale to describe level of agreement (strongly disagree, disagree, neutral, agree, and strongly agree) was used. In the first round, the panel discussed and revised each statement after voting. A consensus of 75% or more agreement was the predetermined level to include a statement in the final recommendations. Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines were followed for developing the manuscript.

Results

The modified-Delphi process resulted in seven recommendations intended to guide vaccination in children with AD on dupilumab (Table 1).

Table 1.

Recommendations for vaccination in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab based on our modified-Delphi process

| Initial statements | Level of agreement (%) | Final statements/recommendations | Level of agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab interferes with humoral or cellular immune responses to vaccines but does not appear to affect the development of protective titers |

2 (40) neutral 3 (60) disagree |

Based on available data, dupilumab does not appear to affect the development of protective antibodies titers to inactivated vaccines | 100% strongly agree |

| Dupilumab should not be interrupted for inactivated vaccines |

3 (60) strongly agree 2 (40) agree |

Dupilumab treatment does not need to be interrupted for administration of inactivated vaccines | 100% strongly agree |

| Seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccination should not be avoided while on dupilumab |

2 (40) strongly agree 3 (60) agree |

For patients on dupilumab treatment, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccination should continue as recommended | 100% strongly agree |

| Live vaccinations should be given prior to dupilumab if possible |

1 (20) strongly agree 4 (80) agree |

Based on available data, live attenuated vaccines should be avoided while on dupilumab | 100% strongly agree |

| Live attenuated vaccines should be avoided while on dupilumab |

4 (80) agree 1 (20) neutral |

When live attenuated vaccinations are required, they should be given at least 4 weeks prior to initiation of dupilumab treatment, if possible | 100% strongly agree |

| Measurement of antibody levels after vaccination is necessary to ensure serologic protection |

1 (20) agree 3 (60) neutral 1 (20) disagree |

While on dupilumab, measurement of specific antibody levels can be considered to ensure serologic protection after vaccination on dupilumab therapy | 100% strongly agree |

| There is no risk of atopic dermatitis exacerbation with immunization on dupilumab |

1 (20) agree 4 (80) neutral |

There is no evidence to suggest that immunization while on dupilumab causes an exacerbation of atopic dermatitis | 100% strongly agree |

Statement 1

Based on available data, dupilumab does not appear to affect the development of protective antibodies titers to inactivated vaccines.

Evidence Summary

The expert panel agreed dupilumab does not appear to affect the development of antibody titers in adults, according to a phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled study (97 patients in each group) that assessed vaccine responses [17]. The T cell dependent humoral response to tetanus toxoid (Tt) vaccine (Adacel®) demonstrated that vaccination at week 12 of dupilumab therapy (300 mg weekly) did not interfere with IgG production. Most patients (83.3%) developed a protective response, achieving a fourfold increase in titer 1 month after vaccination (median Tt titers from 1.21 IU/mL to 13.91 IU/mL; p < 0.0001). Moreover, no differences were observed between IgG titers in the dupilumab-treated group compared to the placebo group at week 16. Dupilumab did not affect T cell independent responses to the serogroup C meningococcal polysaccharide from the MPSV4 vaccine (Menomune®), with titer levels comparable to placebo treatment (median titers from < 4 IU/mL week 12 to 1024 IU/mL week 16 in both groups) [17]. It is important to note that the Tdap vaccine (Adacel®; approved ≥ 4 years old) is a booster (a subsequent exposure to the vaccine antigen) that elicits a different immune response than the primary series (the first encounter with the vaccine antigen). The primary series triggers the beginning of the immune response, producing IgM and memory cells, whereas a booster produces a secondary immune response in which those previously developed memory T cells and B cells will recognize the vaccine antigen, resulting in a faster, larger, and more effective response, primarily producing IgG specific antibodies. This mechanism explains why immunosuppressive therapies hamper booster responses less than they inhibit primary immune responses. In contrast, Menomune® can be used for both primary immunization and booster. Unfortunately, the MPSV4 vaccination status of patients in this study was not documented, so we cannot distinguish if these patients’ responses were primary or secondary.

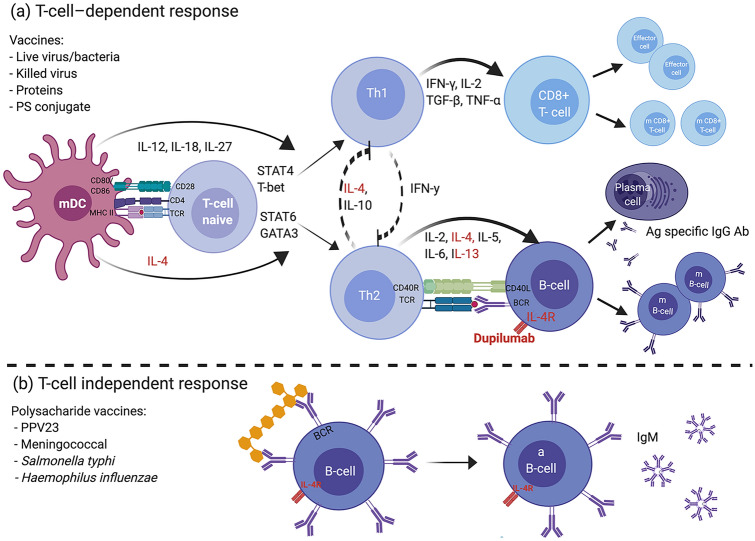

AD patients are prone to infection in part due to overexpression of IL-4 and IL-13 [18, 19]. Specifically, IL-4 has been shown to impair antiviral immunity as it downregulates the type I immune response, thereby decreasing cell-mediated immunity (Fig. 1) [20, 21]. IL-4/13 blockade has numerous potential benefits for AD patients, including a decrease in skin infections, better antimicrobial immunity [22–27], and possible enhanced T helper (TH)1 responses that are critical to antiviral immunity and vaccination responses [17, 28] (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Vaccine response and the potential impact of dupilumab. Dupilumab is a human (IgG4) monoclonal antibody anti-IL-4 receptor that blocks the α-subunit shared by IL‐4R receptor type I and II, decreasing the signal induced by IL-4 and IL-13. a T cell-dependent response vaccines generate humoral and cellular responses with immune memory. After recognition of the antigen, APCs (B cells, macrophages, or DCs) present the processed antigen to naive T cells via peptide-MHC II. Co-stimulation between B7 ligands (CD80/CD86) and CD28 on the T cell is required. The type of pathogen determines the cytokine environment, which dictates the development of a specific T cell phenotype. IL-12, secreted by the DC in response to virus infection or intracellular bacteria, promotes polarization towards the TH1 pathway, which secretes IFNγ and activates CD8 + CTLs and phagocytic cells and inhibits TH2 development. In contrast, IL-4 initiates polarization to TH2 pathways and inhibits TH1 development. Via activation of STAT6 and GATA3, IL-4 promotes gene expression of IL‐4, IL‐5, and IL‐13. APCs trigger a TH2 cell response in the presence of thymic stromal lymphopoietin, IL-25, and IL-33 produced by epithelial cells. TH2 responses drive B cell activation, requiring co‐stimulatory signals through the CD40–CD40L (CD154) from the TH cell and leading to differentiation into a plasma cell, isotype class switching, antibody secretion and clonal expansion of memory B cells. IL-4 acts as a B cell growth factor, and IL-6 assists in maturation of the antibody response. Theoretically, blocking IL-4 does not impair response to viral infection. b Polysaccharide vaccines elicit a T cell–independent response. The antigen directly interacts with B cells, producing antibodies limited to IgM without immunologic memory. Live bacteria: BCG. Live virus: influenza (intranasal), measles, mumps, oral polio, rotavirus, rubella, varicella zoster, yellow fever. Killed virus: inactivated poliovirus. PS conjugated: Haemophilus influenzae type B, meningococcal and pneumococcal conjugated. Protein: acellular pertussis, diphtheria, hepatitis B, human papillomavirus, influenza, tetanus. Ab antibody, aB cell activated B cell, Ag antigen, APC antigen presentation cell, BCG bacille Calmette-Guerin, BCR B cell receptor, CTL cytotoxic T lymphocytes, DC dendritic cell, IFN interferon, Ig immunoglobulin, IL interleukin, m B cell memory B cell, m CD8 + T cell memory T cell, mDC mature dendritic cell, MHC major histocompatibility complex, PS polysaccharide, TH T helper, TNF tumor necrosis factor, TCR T cell receptor, TGF transforming growth factor. Created with BioRender.com

Table 2.

IL-4 and IL-13 summary.

Adapted from Delves et al. [78], Bao and Reinhardt [79], and Kelly-Welch et al. [80]

| IL-4 | IL-13 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gene | Chromosome 5 | Chromosome 5 |

| Source | TH2, mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, NK, NKT, γδ T cell, | TH2 and mast cells |

| Target | T cell, B cell, macrophage | B cell, macrophage |

| Function |

Induces differentiation of TH0 cell to TH2, creating a positive feedback loop, producing more IL-4 Regulation of B cell function and class switching to IgG1 and IgEa Proliferation of activated B, T, and mast cells Upregulates IgM, CD23 and MHC class II on B cells DC differentiation Differentiation, maturation, and functionality of DC in vitro Increases macrophage phagocytosis Inhibition of cell-mediated immunity |

Regulation of several stages of B cell maturation and proliferation Switching to IgG1 and IgE Inhibits activation and cytokine secretion by macrophages Induces VCAM-1 Modulates smooth cell muscle contraction and mucus secretion in the airway epithelium Inhibits cell-mediated immunity |

| Receptor |

Type I receptor (IL‐4Rα/γc)b Type II receptor (IL‐4Rα/IL-13Rα1) |

Type II receptor (IL‐4Rα/IL-13Rα1) IL-13Rα2c |

| Downstream signaling pathways |

JAK1 JAK3 STAT6 |

JAK1 TYK2 STAT6 |

DC dendritic cell, Ig immunoglobulin, IL interleukin, JAK Janus kinase, MHC major histocompatibility complex, NK natural killer, NKT natural killer T cell, TH T helper, VCAM-1 vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

aIL-4 induces class switching to IgG1 and IgE

bType I and II receptor are expressed on hematopoietic cells. Type II is expressed on non‐hematopoietic cells as well

cIL-13Rα2: decoy receptor without signaling function

Differentiation and maturation of dendritic cells (DCs) are essential to vaccination because of their role in initiating the immune response by presenting vaccine antigens. The effect of dupilumab on DCs and vaccination is unknown, but it does suppress the TH2 pathway (chemokines for DCs and T cells) and DC markers and genes [28]. The significance of this suppression is unclear, but it may return overactive DCs to a closer-to-physiologic state.

Statement 2

Dupilumab treatment does not need to be interrupted for administration of inactivated vaccines.

Evidence Summary

The expert panel agreed that inactivated vaccines can be administered while patients are on dupilumab based on the non-existent risk of vaccine-strain infection [29–32]. AD patients with dupilumab who received inactivated (Tdap and MPSV4) vaccination elicited a satisfactory humoral response [17], suggesting immunogenicity is not affected.

Statement 3

For patients on dupilumab treatment, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccination should continue as recommended.

Evidence Summary

Based on the high rates of seasonal influenza infection (influenza A and B) in children, as well as complications associated with this infection, seasonal inactivated influenza vaccination is recommended in pediatric patients with chronic diseases, including pediatric AD patients on dupilumab. The type of seasonal flu vaccine is region-specific and may mount a slightly different immune response and may have varied vaccine efficacy in dupilumab-treated patients. The PHAC and CDC recommend routine annual influenza immunization with an inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV) that is safe and immunogenic in immunocompromised children older than 6 months [14, 15, 33, 34]. The live attenuated influenza vaccine, given intranasally, is contraindicated in patients with compromised immune systems, including immunosuppression caused by medications [14]. The World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended quadrivalent influenza vaccine for the Northern Hemisphere in the 2020–2021 season, the antigenic strains are influenza A (H3N2 and H1N1) and the two influenza B viruses (Yamagata or Victoria) [35]. Studies in vaccinated pediatric oncology patients, pediatric solid organ transplant recipients, and pediatric patients receiving biologics for inflammatory bowel disease or rheumatologic conditions have documented satisfactory humoral immune responses [36–40].

Statement 4

Based on available data, live attenuated vaccines should be avoided while on dupilumab. However, such vaccines can be considered on a case-to-case basis weighing the risk of infection versus the risks of vaccination.

Evidence Summary

The expert panel emphasizes that there is insufficient data on the safety and efficacy of live attenuated vaccines in patients on biologics including dupilumab and recognizes the urgent need for further research to determine whether dupilumab affects the immune response against live attenuated vaccines and how safe these vaccines would be in children on active therapy.

Furthermore, given the lack of safety data on live attenuated vaccine administration in AD patients on dupilumab, the expert panel advises to consider the immunization process and to cautiously extrapolate data from other biologics until new evidence becomes available, with the caveat that the effect on the immune system depends on the type of immunomodulatory agent (Table 3).

Table 3.

Studies of LAVs in a pediatric population on immunosuppressive therapy

| Year | Authors | Study design | Vaccine (n) | n | Age (range) | Disease | Biologics (n) | Safety | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Uziel et al. [53] | Retrospective study. 13 pediatric rheumatology centers in 10 countries | MMR-V booster | 234 | 5 ± 2.7 y |

211 JIA 11 JDM 5 Scle 5 isolated IU 1 NOMID 1 MKD 1 FMF |

MTX m (124) MTX + biologics (62): INX (1) ETN (33) ADA (22) TCZ (1) CAM (5) MTX + DMARDs (9): CsA (7) Salazopirin (1) LEF (1) Biologics (39): INX (1) ETN (16) ADA (6) TCZ (4) ANK (6) CAM (6) |

No vaccine-related infection of measles, rubella, mumps, or varicella was reported. Mild adverse effects were reported |

MMR-V booster vaccines were safe |

| 2018 | Jeyaratnam et al. [56] | Multicenter survey (85 physicians from 23 countries) |

1st dose: YF (4); MMR-V (1); Var (1) Booster: MMR (7); Var (3); oral polio (1) |

17 | 9 (1–58 y) |

7 JIA 5 CAPS 4 MKD 1 FMF |

Anti-IL-1 (10) Anti-IL-6 (7) |

SAE: 2 pts (needing hospitalization) | Study reflects the reluctance of physicians to administer LAVs to patients using biologicals. LAVs cannot be considered entirely safe in patients using IL-1 or IL-6 blockade |

| 2018 | Speth et al. [57] | Prospective study |

Var 1st dose (6): 3 LIIS 3 HIIS 1st + 2nd dose (9): 4 LIIS (6 wks apart) 5 HIIS (3 mo apart) Booster (9): 2 LIIS 7 HIIS |

23 |

LIIS: 8.3 (1.8-17.8 y) HIIS: 9.7 (2.7-17.8 y) |

LIIS: 8 JIA 1 SS HIIS: 11 JIA 2 JDM 1 MPA |

MTX m (1); MMF m (1); LEF m (1); ETN m (3) LEF + biologics: + ABA (1) + ANK + Cs (1) + ETN + Cs (1) + TCZ (1) MTX + biologics: ADA (1) ANK + Cs (1) TCZ (1) |

No vaccine-induced varicella disease symptoms. No other AEs within 4 wk after vaccination |

Var vaccination is safe in children 5 out of the 6 pts naïve to Var vaccination had only one dose due to an increase in Var-IgG-level |

| 2017 | Groot et al. [58] | Prospective study | Var (1st and 2nd doses) | 67 |

G1: 28 pts—5 (2–15 y) received 1 dose 21 pts—3.5 (2–17 y) received 2 doses CG: 8.5 (3–18 y) received one dose |

G1: 39 JIA 5 JDM 5 JScle CG: 18 HP |

MTX m (25) MTX + Cs (18) Biologics (3): ADA—received only the 1st dose Received 2 doses: ETN—responded to 2nd dose ABA—unresponsive |

Pt on ABA developed chicken pox | Biologics affected the immunogenicity of the vaccine in contrast to immunosuppressive drugs |

| 2015 | Toplak and Avcin [59] | Prospective study | Var (1st and 2nd doses) | 6 | 4.7 (2.5–7 y) | JIA |

ETN (3) INX (1) TCZ (2) |

SAE: 0 Mild Var infection (4 mo after the 2nd dose)—1 Pt [81] with low protective levels of Ab |

Variable humoral response to vaccination, which did not always provide adequate protection 5 pts (83%) had protective Ab levels 6 wk after the 2nd dose |

| 2013 | Heijstek et al. [55] | RCT | MMR booster | 131 |

Vg: 6.3 (5.9–6.7 y) CG: 6.5 (6.2–6.9 y) |

Vg: 63 CG: 68 (no vaccination) |

ETN (5) ADA (1)* ANK (3) 2 pts took oral Cs concomitantly |

SAE: 0 None showed disease caused by attenuated viruses |

Biologics did not affect humoral responses when stopped 5 half-lives before administration MMR booster induced high seroprotection rates in all pts At 12 mo after vaccination, Ab concentrations were significantly higher |

| 2009 | Borte et al. [54] | Prospective study | MMR booster | 15 | 6–17 y |

15 JIA: G1: 5 G2a: 5 G2b: 5 CG: 20 HP |

G2b: low-dose MTX in combination with anti-TNF |

No mumps, measles, and rubella infections were seen 6 mo after the booster | MMR booster was effective as virus specific IgG levels were not affected |

Ab antibody, ABA abatacept, ADA adalimumab, AE adverse event, ANK anakinra, CAM canakinumab, CAPS cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome, CG control group, Cs corticosteroids, CsA cyclosporine, DMARDs disease modifying antirheumatic drugs, ETN etanercept, FMF familial Mediterranean fever, G group, HIIS high-intensity immunosuppression including biological therapy, HP healthy persons, Ig immunoglobulin, IL interleukin, INX infliximab, IU idiopathic uveitis, JDM juvenile dermatomyositis, JIA juvenile idiopathic arthritis, JScle juvenile scleroderma, LAVs live attenuated vaccines, LEF leflunomide, LIIS low-intensity immunosuppression including biological therapy, m monotherapy, MKD mevalonate kinase deficiency, MMF mycophenolate mofetil, MMR measles, mumps, and rubella, MMR-V measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella, mo months, MPA microscopic polyangiitis, MTX methotrexate, NOMID neonatal onset multi-inflammatory disease, pt(s) patient(s), RCT randomized controlled trial, SAE serious adverse event, Scle scleroderma, SS Sjögren syndrome, TCZ tocilizumab, Var varicella, Vg vaccinated group, wk weeks, y years, YF yellow fever.

*Were stopped before vaccination at 5 times their half-lives

In general, live attenuated vaccines require an appropriate T cell‐dependent response for virus clearance and to develop an effective specific-antibody response (Fig. 1) [41–43]. Whereas in children, primary measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccination predominantly elicits a TH1 response, in adults, a TH2 response predominates in receiving their booster of monovalent measles vaccine [44, 45]. In measles infection, the TH1 pathway is the initial immune response, shifting towards TH2 and TH17 cells weeks later [46–50]. In theory, dupilumab’s mechanism of action should not affect immune responses to MMR, but may influence the delayed TH2 response and therefore the vaccine immunogenicity and safety.

Regarding measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMR-V) booster vaccination during dupilumab therapy, which is of utmost interest to the panel as some AD pediatric patients would be in the age range when they may require a booster, safety data are insufficient to make a positive recommendation [51]. Nonetheless, the panel recommends an individualized assessment considering the benefit of MMR-V immunization against the risk of infection in patients already taking dupilumab. Specific antibody titers to assess immunity can assist decision making and are discussed in Statement 6.

The Pediatric Rheumatology European Association (PReS) vaccination working party [52] recommend administering an MMR-V booster in children based on a recent retrospective study in pediatric rheumatology that found no severe adverse events or vaccine-related infections in 39 children on biologics (six adalimumab, six anakinra, six canakinumab, 16 etanercept, one infliximab, four tocilizumab) and 62 children on methotrexate with biologics (22 adalimumab, five canakinumab, 33 etanercept, one infliximab, one tocilizumab) who received booster vaccines [53].

However, the results of case series of vaccination of pediatric rheumatologic patients on various biologics show mixed responses. For instance, the MMR/MMR-V booster vaccine was safe and immunogenic in five children who received it simultaneously with etanercept (0.4 mg/kg body weight twice weekly) in combination with low-dose methotrexate (10 mg/m2 body surface per week) [54], and another study showed high and durable seroprotection to MMR booster when biologics (one adalimumab; three anakinra; five etanercept) were discontinued for five half-lives before vaccination [55]. In a study of patients on IL-1 or IL-6 blockade, seven patients received MMR booster and only one developed bacterial pneumonia after an MMR booster while on treatment with anti-IL-1 (canakinumab), prednisone (5 mg/day), and methotrexate [56], likely related to overall immunosuppression rather than the MMR booster.

With regards to the varicella vaccine, studies have also found diverse immune responses [57]. Three children treated with methotrexate combined with biologics (adalimumab, etanercept, abatacept) did not develop antibodies against varicella after vaccination [58]. After a second dose of the vaccine, the patient on etanercept had an increase in varicella IgG titers, but no response was seen in the patient on abatacept who developed varicella infection 1 year after vaccination [58]. Another study of six children with rheumatologic diagnoses on biologics (one infliximab, three etanercept, two tocilizumab) who received two doses of varicella vaccine, showed that the patient on infliximab did not develop antibodies after two doses, while three patients on etanercept had low titers (one of whom developed mild varicella infection 4 months after vaccination). Two children on tocilizumab had an increase in antibody concentration, but their levels significantly declined at 11 and 27 months after vaccination [59]. Other studies in children on anti-IL-1 (n = 14 patients) or IL-6 therapy (n = 3 patients) reported two serious adverse events (SAEs); one of three patients who received a varicella booster had varicella infection on anti-IL-1 (anakinra) and disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) (prednisone 0.12 mg/kg/day, methotrexate, leflunomide, and thalidomide), and another developed bacterial pneumonia after an MMR booster while on anti-IL-1 (canakinumab), prednisone (5 mg/day), and methotrexate [56]. Ultimately, although more evidence is needed, pediatric rheumatologists advocate that live attenuated booster vaccinations (MMR-V) can be considered individually as some studies have reassured safety, and no detrimental effect on immunogenicity has been described for glucocorticosteroids (low doses) and methotrexate. Indeed, rheumatic patients on biologics may need an additional booster due to a rapid loss of antibody levels despite having reached adequate immunogenicity, but less than drug-free patients. Most studies showing this loss in antibody concentrations were on patients using tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) blockers [60, 61].

Statement 5

When live attenuated vaccines are required, they should be given at least 4 weeks prior to initiation of dupilumab treatment, if possible. However, such vaccines can be considered on a case-to-case basis weighing the risk of infection versus the risks of vaccination.

Evidence Summary

The expert panel agreed that live attenuated vaccines should be given 4 weeks before starting dupilumab based on the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommendations for the timing of vaccinations in immunocompromised hosts [30]. These clinical guidelines recommend administering live attenuated vaccines at least 4 weeks prior to initiation of immunosuppressive medications [30]. It is important to note that dupilumab is considered immunomodulatory rather than immunosuppressive by the IDSA. Despite differences in mechanism and impact on immune system function, given the paucity of data, adherence to the IDSA guidelines is suggested. Canadian dermatology guidelines for adult patients on biologic therapy emphasize the importance of considering vaccine-induced viremia and the pharmacokinetic profile of the treatment to determine the best timing of vaccination [31]. Other societies take into account the incubation period instead of the post-vaccinal viremia [62].

For patients already on immunosuppressive therapy, the CDC recommends withholding live attenuated vaccine for 3 months after immunosuppressive therapies, including interleukins, colony-stimulating factors, and TNFα inhibitors, have been stopped [15]. Other guidelines recommend stopping biologic agents more than three half-lives before live attenuated vaccine administration [63–65]. Regarding dupilumab, pharmacokinetic studies showed that dupilumab concentrations decreased below the lower limit of detection 10 weeks after a last dose of 300 mg [6]. Nevertheless, there is insufficient data on its half-life to make an accurate safe timing recommendation [7, 66].

Some guidelines specifically suggest avoiding live attenuated vaccine within 2 weeks of initiation of immunosuppressive therapy [30]. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [29] recommends withholding live attenuated vaccine in pediatric patients on high-dose DMARDs (methotrexate > 15 mg/m2 per week; cyclosporine > 2.5 mg/kg per day; sulfasalazine > 40 mg/kg per day up to 2 g/day; azathioprine > 1 to 3 mg/kg; cyclophosphamide > 0.5 to 2.0 mg/kg per day orally; leflunomide > 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg per day; 6-mercaptopurine > 1.5 mg/kg per day), high-dose glucocorticosteroids (≥ 2 mg/kg or a total dosage of ≥ 20 mg/day for ≥ 2 weeks or < 2 mg/kg/day if chronically administered) or biological agents (anti-TNFα, rituximab, anti-IL-6, and anti-CD11a) [29]. However, EULAR also advises carefully weighing the risk of wild-type infection against the risk of infection with an attenuated agent with vaccination [29, 52]. Similarly, the American Academy of Dermatology [67] recommends a detailed and cautious assessment when considering live attenuated vaccine in children with psoriasis treated with anti-TNFα and ustekinumab [68], while it advises discontinuing psoriasis biologics (anti-TNFα, anti-IL17, and IL-12/IL-23 inhibitors) before live attenuated vaccine in adults [64].

Statement 6

While on dupilumab, measurement of specific antibody levels can be considered to ensure serologic protection after vaccination on dupilumab therapy.

Evidence Summary

Assessment of serologic immune response is recommended by other authors based on studies in children and adult patients on immunosuppressive medications that showed a diminished immunologic response to influenza and pneumococcal [69], hepatitis B [70], and Pneumovax-23 vaccines [70].

Since the degree of impairment of vaccine responses by dupilumab is unknown, the expert panel suggests assessing for seroconversion as available at local laboratories with specific antibodies 4–6 weeks after vaccination to ensure patients have achieved an adequate response. Seroconversion for diphtheria, tetanus, hepatitis A and B, measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella are widely available whereas pneumococcal may not be. Vaccines that do not elicit protective titers should be re-administered and post-vaccination titers repeated to ensure adequate immune responses. Laboratory tests assessing humoral and cellular immunity, including lymphocyte immunophenotyping by flow cytometry and serum immunoglobulins, are recommended if vaccination fails.

Statement 7

There is no evidence to suggest that immunization while on dupilumab causes an exacerbation of AD.

Evidence Summary

Immunizations in AD patients are safe and there is no evidence that immunization aggravates AD [71]. Furthermore, AD patients have a normal immune response to live attenuated vaccine and influenza vaccines [72, 73]. Vaccination at week 12 (with Tdap and MPSV4) of dupilumab therapy was not associated with AD exacerbation in adult patients receiving a weekly dupilumab (higher than standard dosing) [17].

In general, AD patients should be vaccinated according to the national vaccination plan, but they should not be vaccinated during an acute AD flare. In the scenario of an acute AD flare, starting treatment to achieve disease control should be prioritized over vaccination. Good clinical AD control for 2 weeks before receiving vaccinations is optimal to avoid skin complications related to vaccination [74].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first consensus statement addressing the questions of safety and effectiveness of vaccination in children on dupilumab for AD. The strengths of this consensus include its adherence to a modified-Delphi methodology and a face-to-face interaction with multidisciplinary discussion and expert opinion. This consensus resulted in statements that offer an approach to vaccination for healthcare providers caring for children with AD on dupilumab.

The MMR-V booster was extensively discussed, as it is recommended at an age (4–6 years old) commonly affected by AD. Research in children with rheumatic diseases treated with other biologics has suggested booster vaccinations to be generally safe, though caution with live attenuated vaccine and anti-TNF and anti-IL-1/6 agents seems prudent based on severe but rare reports of adverse events. However, prospective studies to prove the safety and efficacy of booster live attenuated vaccines in dupilumab-treated children in the long term are required to provide an evidence-based risk–benefit assessment. If there is a situation where a live attenuated vaccine is needed, such as a measles outbreak in the community and children without protective measles antibody titers who would go to school, the expert panel recommends an individualized assessment weighing the risk of infection in conjunction with a clinical immunologist and an infectious disease specialist. Parents should be made aware of the risks taken regarding vaccination and the dangers of infection. Theoretically, based on the effect of dupilumab on the TH2 pathway, blocking IL-4 probably would not impair the response to viral infection and to live attenuated vaccine; therefore, the immune response to live attenuated vaccines that elicit TH1-dependent immunity should not be affected. However, there is insufficient evidence to provide a formal recommendation.

Unfortunately, our work has several limitations, including the small number of panelists involved in this process and the use of a cut-off of 75% agreement for consensus. We would highlight that all statements did reach 100% agreement despite the a priori 75% level established. From an evidence perspective, there are no data on vaccination of pediatric AD patients from dupilumab clinical trials, as vaccinations were not permitted in trial subjects. Second, evidence of vaccine responses in pediatric AD patients on immunosuppressive treatment is also sparse. Most evidence on vaccinations in immunocompromised patients comes from children with rheumatologic conditions using psoriasis biologics with different mechanisms of action than dupilumab. Third, existing international guidelines on immunizations are primarily based on expert opinion and a moderate to low level of evidence. Though international AD guidelines and national publications providing clinical guidance on the management of adult and pediatric AD exist [75, 76], few have addressed vaccination while on immunosuppressive agents [74, 77]. The American Academy of Dermatology guidelines from 2014 advises considering administering a booster to AD children on long-term systemic steroids [77], whereas the European guidelines from 2018 recommend consulting a specialist before live attenuated vaccine is administered on children on immunosuppressive therapy [74]. Moreover, only two guidelines have been published since the approval of dupilumab [74, 76] (see the electronic supplementary material), but there was no recommendation in this regard. Finally, this consensus meeting happened before coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines became available, which were not included in our literature review and recommendations statements.

Conclusion

This modified-Delphi consensus process identified critical questions for future studies. First, does dupilumab interfere with vaccination responses/development of immunity? Second, how do we address the lack of clinical studies addressing safety, immunogenicity, and clinical efficacy of primary vaccinations and boosters in children with AD on dupilumab, in particular, for the MMR-V booster vaccine, to keep our patients safe? Finally, is there an impact of long-term dupilumab therapy on protective antibodies developed pre-dupilumab therapy and are supplementary boosters required? In the absence of an evidence base to guide clinical decision making, our consensus discussions and statements are a starting point/food for thought for clinicians struggling with these decisions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the research librarian and Dhawan S., MD, for their contribution, and Tracy Chew, Ph.D., who provided professional medical editing support for an initial draft of this manuscript.

Declarations

Funding

None.

Conflicts of interest

SMC: none; MK: advisor/consultant for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bausch Health, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, UCB, and Sanofi Genzyme, and served as a speaker for AbbVie, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, and Sanofi Genzyme; CC: has received honoraria for speaking engagements for Federation of Canadian Women of Canada, GSK, Pfizer, and Merck; LM-F: advisor/consultant for, has received honoraria from Sobi and Takeda; MR: advisor/consultant for, has received grants/honoraria from, and/or has served as a speaker for LEO Pharma, Pfizer, and Sanofi Genzyme.

Authors’ contribution

Conception and design: SMC and MR. Analysis and interpretation of the data: all authors. Drafting of the article: SMC, MR, and MK. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: all authors. Final approval of the article: all authors.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Igelman S, Kurta AO, Sheikh U, McWilliams A, Armbrecht E, Jackson Cullison SR, et al. Off-label use of dupilumab for pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: A multicenter retrospective review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):407–411. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pirofski LA, Casadevall A. Use of licensed vaccines for active immunization of the immunocompromised host. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11(1):1–26. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupixent: EPAR. Product Information. European Medicines Agency 2017. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/dupixent. Revised July 2020. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 4.Gooderham MJ, Hong HC, Eshtiaghi P, Papp KA. Dupilumab: a review of its use in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(3 Suppl 1):S28–S36. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelly-Welch AE HE, Boothby MR, Keegan AD. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science. 2003;300(5625):1527–1528. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science. 2003;300(5626):1527–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. DUPIXENT® (dupilumab). Highlights of prescribing information. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s014lbl.pdf. Revised June 2019. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 7.Sanofi-Aventis Canada Inc. Dupixent. Public Health Agency of Canada.Summary Basis of Decision–Dupixent–Health Canada https://hpr-rps.hres.ca/reg-content/summary-basis-decision-detailTwo.php?linkID=SBD00381 Revised April 2019. Last modified November 13, 2020. Accessed 17 Nov 2020.

- 8.Silverberg JI, Yosipovitch G, Simpson EL, Kim BS, Wu JJ, Eckert L, et al. Dupilumab treatment results in early and sustained improvements in itch in adolescents and adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: analysis of the randomized phase 3 studies SOLO 1 and SOLO 2, AD ADOL, and CHRONOS. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cork MJ, Thaci D, Eichenfield LF, Arkwright PD, Hultsch T, Davis JD, et al. Dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase IIa open-label trial and subsequent phase III open-label extension. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):85–96. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Treister AD, Lio PA. Long-term off-label dupilumab in pediatric atopic dermatitis: a case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):85–88. doi: 10.1111/pde.13697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siegfried EC, Igelman S, Jaworsk JC, Antaya RJ, Cordoro KM, Eichenfield LF, et al. Use of dupilimab in pediatric atopic dermatitis: access, dosing, and implications for managing severe atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(1):172–176. doi: 10.1111/pde.13707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simpson EL, Lockshin B, Davis JD, Sun X, Gadkari A, Eckert L, Rossi AB, Bansal A. pharmacokinetics, safety, and efficacy of dupilumab in children aged ≥ 2 to < 6 years with severe, uncontrolled atopic dermatitis (LIBERTY AD PRE-SCHOOL). Preliminary results presented at the 7th the Pediatric Dermatology Research Alliance (PeDRA) Annual Conference; November 14–16 2019, Chicago, IL.

- 14.Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Immunization Guide Part 3-Vaccination of Specific Populations. Immunization of immunocompromised persons: Canadian Immunization Guide. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-8-immunization-immunocompromised-persons Reviewed on May 2018. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Advisory Comittee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) General Best Practice Guidelines for Immunization: Altered immunocompetence. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/general-recs/immunocompetence.pdf. Last reviewed April 2017. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 16.Junger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31(8):684–706. doi: 10.1177/0269216317690685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blauvelt A, Simpson EL, Tyring SK, Purcell LA, Shumel B, Petro CD et al. Dupilumab does not affect correlates of vaccine-induced immunity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(1):158–67 e1. 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Werfel T, Allam JP, Biedermann T, Eyerich K, Gilles S, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Cellular and molecular immunologic mechanisms in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(2):336–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thyssen JP, Kezic S. Causes of epidermal filaggrin reduction and their role in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(4):792–799. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramshaw IA, Ramsay AJ, Karupiah G, Rolph MS, Mahalingam S, Ruby JC. Cytokines and immunity to viral infections. Immunol Rev. 1997;159:119–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma DP, Ramsay AJ, Maguire DJ, Rolph MS, Ramshaw IA. Interleukin-4 mediates down regulation of antiviral cytokine expression and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses and exacerbates vaccinia virus infection in vivo. J Virol. 1996;70(10):7103–7107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.7103-7107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Benedetto A, Agnihothri R, McGirt LY, Bankova LG, Beck LA. Atopic dermatitis: a disease caused by innate immune defects? J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(1):14–30. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Egholm C, Heeb LEM, Impellizzieri D, Boyman O. The regulatory effects of interleukin-4 receptor signaling on neutrophils in type 2 immune responses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2507. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luci C, Gaudy-Marqueste C, Rouzaire P, Audonnet S, Cognet C, Hennino A, et al. Peripheral natural killer cells exhibit qualitative and quantitative changes in patients with psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(4):789–796. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mack MR, Brestoff JR, Berrien-Elliott MM, Trier AM, Yang TB, McCullen M et al. Blood natural killer cell deficiency reveals an immunotherapy strategy for atopic dermatitis. Sci Transl Med. 2020. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aay1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Howell MD, Boguniewicz M, Pastore S, Novak N, Bieber T, Girolomoni G, et al. Mechanism of HBD-3 deficiency in atopic dermatitis. Clin Immunol. 2006;121(3):332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell MD, Gallo RL, Boguniewicz M, Jones JF, Wong C, Streib JE, et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis skin subverts the innate immune response to vaccinia virus. Immunity. 2006;24(3):341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guttman-Yassky E, Bissonnette R, Ungar B, Suarez-Farinas M, Ardeleanu M, Esaki H, et al. Dupilumab progressively improves systemic and cutaneous abnormalities in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heijstek MW, Ott de Bruin LM, Bijl M, Borrow R, van der Klis F, Kone-Paut I et al. EULAR recommendations for vaccination in paediatric patients with rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1704–12. 10.1136/ard.2011.150193. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, Davies EG, Avery R, Tomblyn M, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):309–318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papp KA, Haraoui B, Kumar D, Marshall JK, Bissonnette R, Bitton A, et al. Vaccination guidelines for patients with immune-mediated disorders on immunosuppressive therapies. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(1):50–74. doi: 10.1177/1203475418811335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.General recommendations on immunization—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60(2):1–64. [PubMed]

- 33.Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2019–2020. Pediatrics. 2019. 10.1542/peds.2019-2478. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Hakim H, Allison KJ, Van de Velde LA, Tang L, Sun Y, Flynn PM, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of high-dose trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine compared to standard-dose vaccine in children and young adults with cancer or HIV infection. Vaccine. 2016;34(27):3141–3148. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.04.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO. Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2020–2021 northern hemisphere influenza season. WHO recommendations on the composition of influenza virus vaccines. https://www.who.int/influenza/vaccines/virus/recommendations/202002_recommendation.pdf?ua. Produced February 2020. Accessed Mar 2020.

- 36.Camacho-Lovillo MS, Bulnes-Ramos A, Goycochea-Valdivia W, Fernandez-Silveira L, Nunez-Cuadros E, Neth O, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of influenza vaccination in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on biological therapy using the microneutralization assay. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s12969-017-0190-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogimi C, Tanaka R, Saitoh A, Oh-Ishi T. Immunogenicity of influenza vaccine in children with pediatric rheumatic diseases receiving immunosuppressive agents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2011;30(3):208–211. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181f7ce44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shinoki T, Hara R, Kaneko U, Miyamae T, Imagawa T, Mori M, et al. Safety and response to influenza vaccine in patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis receiving tocilizumab. Mod Rheumatol. 2012;22(6):871–876. doi: 10.1007/s10165-012-0595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu Y, Jacobson DL, Ashworth LA, Grand RJ, Meyer AL, McNeal MM, et al. Immune response to influenza vaccine in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):444–453. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winthrop KL, Silverfield J, Racewicz A, Neal J, Lee EB, Hrycaj P, et al. The effect of tofacitinib on pneumococcal and influenza vaccine responses in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(4):687–695. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-207191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lin WH, Pan CH, Adams RJ, Laube BL, Griffin DE. Vaccine-induced measles virus-specific T cells do not prevent infection or disease but facilitate subsequent clearance of viral RNA. mBio. 2014;5(2):e01047. 10.1128/mbio.01047-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Permar SR, Griffin DE, Letvin NL. Immune containment and consequences of measles virus infection in healthy and immunocompromised individuals. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13(4):437–443. doi: 10.1128/cvi.13.4.437-443.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Good RA, Zak SJ. Disturbances in gamma globulin synthesis as experiments of nature. Pediatrics. 1956;18(1):109–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pabst HF, Spady DW, Carson MM, Stelfox HT, Beeler JA, Krezolek MP. Kinetics of immunologic responses after primary MMR vaccination. Vaccine. 1997;15(1):10–14. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ward BJ, Griffin DE. Changes in cytokine production after measles virus vaccination: predominant production of IL-4 suggests induction of a Th2 response. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67(2):171–177. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ward BJ, Johnson RT, Vaisberg A, Jauregui E, Griffin DE. Cytokine production in vitro and the lymphoproliferative defect of natural measles virus infection. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1991;61(2 Pt 1):236–248. doi: 10.1016/s0090-1229(05)80027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moss WJ, Ryon JJ, Monze M, Griffin DE. Differential regulation of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-10 during measles in Zambian children. J Infect Dis. 2002;186(7):879–887. doi: 10.1086/344230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffin DE, Ward BJ. Differential CD4 T cell activation in measles. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(2):275–281. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nair N, Moss WJ, Scott S, Mugala N, Ndhlovu ZM, Lilo K, et al. HIV-1 infection in Zambian children impairs the development and avidity maturation of measles virus-specific immunoglobulin G after vaccination and infection. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(7):1031–1038. doi: 10.1086/605648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nelson AN, Putnam N, Hauer D, Baxter VK, Adams RJ, Griffin DE. Evolution of T cell responses during measles virus infection and RNA clearance. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11474. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10965-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Paller AS, Guttman-Yassky E, Irvine AD, Baselga E, de Bruin-Weller M, Jayawardena S, et al. Protocol for a prospective, observational, longitudinal study in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (PEDISTAD): study objectives, design and methodology. BMJ Open. 2020;10(3):e033507. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vaccination Working Group of the Pediatric Rheumatology Society of Europe. https://www.pres.eu/committee-and-wp/working-parties.html.

- 53.Uziel Y, Moshe V, Onozo B, Kulcsar A, Trobert-Sipos D, Akikusa JD, et al. Live attenuated MMR/V booster vaccines in children with rheumatic diseases on immunosuppressive therapy are safe: multicenter, retrospective data collection. Vaccine. 2020;38(9):2198–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borte S, Liebert UG, Borte M, Sack U. Efficacy of measles, mumps and rubella revaccination in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with methotrexate and etanercept. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48(2):144–148. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heijstek MW, Kamphuis S, Armbrust W, Swart J, Gorter S, de Vries LD, et al. Effects of the live attenuated measles-mumps-rubella booster vaccination on disease activity in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309(23):2449–2456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeyaratnam J, Ter Haar NM, Lachmann HJ, Kasapcopur O, Ombrello AK, Rigante D, et al. The safety of live-attenuated vaccines in patients using IL-1 or IL-6 blockade: an international survey. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Speth F, Hinze CH, Andel S, Mertens T, Haas JP. Varicella-zoster-virus vaccination in immunosuppressed children with rheumatic diseases using a pre-vaccination check list. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2018;16(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12969-018-0231-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Groot N, Pileggi G, Sandoval CB, Grein I, Berbers G, Ferriani VPL, et al. Varicella vaccination elicits a humoral and cellular response in children with rheumatic diseases using immune suppressive treatment. Vaccine. 2017;35(21):2818–2822. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Toplak N, Avcin T. Long-term safety and efficacy of varicella vaccination in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with biologic therapy. Vaccine. 2015;33(33):4056–4059. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Groot N, Heijstek MW, Wulffraat NM. Vaccinations in paediatric rheumatology: an update on current developments. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2015;17(7):46. doi: 10.1007/s11926-015-0519-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toplak N, Uziel Y. Vaccination for children on biologics. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2020;22(7):26. doi: 10.1007/s11926-020-00905-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suresh S, Upton J, Green M, Pham-Huy A, Posfay-Barbe KM, Michaels MG et al. Live vaccines after pediatric solid organ transplant: proceedings of a consensus meeting, 2018. Pediatr Transpl. 2019;23(7):e13571. 10.1111/petr.13571. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.S.G. W. XIV Management of the rheumatic diseases. Biologic agents. In: S.G W, editor. Rheumatology secrets. 3rd ed. US: Elsevier, Mosby; 2015.

- 64.Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, Kivelevitch D, Prater EF, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(4):1029–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bühler S, Eperon G, Ribi C, Kyburz D, van Gompel F, Visser LG, et al. Vaccination recommendations for adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14159. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kovalenko P, DiCioccio AT, Davis JD, Li M, Ardeleanu M, Graham N, et al. Exploratory population PK analysis of dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against IL-4Rα, in atopic dermatitis patients and normal volunteers. CPT Pharmacometr Syst Pharmacol. 2016;5(11):617–624. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aikawa NE, Campos LM, Goldenstein-Schainberg C, Saad CG, Ribeiro AC, Bueno C, et al. Effective seroconversion and safety following the pandemic influenza vaccination (anti-H1N1) in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2013;42(1):34–40. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2012.709272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Menter A, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, Kroshinsky D, Paller AS, Armstrong AW, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(1):161–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Agarwal N, Ollington K, Kaneshiro M, Frenck R, Melmed GY. Are immunosuppressive medications associated with decreased responses to routine immunizations? A systematic review. Vaccine. 2012;30(8):1413–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salinas GF, De Rycke L, Barendregt B, Paramarta JE, Hreggvidsdottir H, Cantaert T, et al. Anti-TNF treatment blocks the induction of T cell-dependent humoral responses. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(6):1037–1043. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Anderson HR, Poloniecki JD, Strachan DP, Beasley R, Bjorksten B, Asher MI. Immunization and symptoms of atopic disease in children: results from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(7):1126–1129. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.7.1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schneider L, Weinberg A, Boguniewicz M, Taylor P, Oettgen H, Heughan L, et al. Immune response to varicella vaccine in children with atopic dermatitis compared with nonatopic controls. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(6):1306–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leung DYM, Jepson B, Beck LA, Hanifin JM, Schneider LC, Paller AS, et al. A clinical trial of intradermal and intramuscular seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1575–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.12.952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wollenberg A, Barbarot S, Bieber T, Christen-Zaech S, Deleuran M, Fink-Wagner A, et al. Consensus-based European guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) in adults and children: part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32(5):657–682. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hong CH, Gooderham MJ, Albrecht L, Bissonnette R, Dhadwal G, Gniadecki R et al. Approach to the assessment and management of adult patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section V: consensus statements on the assessment and management of adult patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2018;22(1_suppl):30s–5s. 10.1177/1203475418803625.

- 76.Lansang P, Lara-Corrales I, Bergman JN, Hong CH, Joseph M, Kim VHD et al. Approach to the assessment and management of pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: a consensus document. Section IV: consensus statements on the assessment and management of pediatric atopic dermatitis. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23(5_suppl):32s–9s. 10.1177/1203475419882654.

- 77.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–49. 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Delves PJ, Martin SJ, Burton DR aRI. The production of effectors. Roitt’s essential immunology. 13 ed. UK: Wiley; 2017. p. 220–62.

- 79.Bao K, Reinhardt RL. The differential expression of IL-4 and IL-13 and its impact on type-2 immunity. Cytokine. 2015;75(1):25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kelly-Welch AE, Hanson EM, Boothby MR, Keegan AD. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science. 2003;300(5625):1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1085458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Goll GL, Jørgensen KK, Sexton J, Olsen IC, Bolstad N, Haavardsholm EA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of biosimilar infliximab (CT-P13) after switching from originator infliximab: open-label extension of the NOR-SWITCH trial. J Intern Med. 2019;285(6):653–669. doi: 10.1111/joim.12880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.