Abstract

Objective

Asian Americans are underutilizing mental health services. The aim of the current systematic review was to identify protective and risk factors of mental health help-seeking patterns among the disaggregated Asian Americans and to classify types of help.

Methods

A systematic literature review was conducted using the PRISMA guidelines. The Health Belief Model served as the theoretical framework for this review. Thirty-four articles were reviewed, and the studies investigated one of the following Asian ethnic subgroups: Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian, Korean, or Vietnamese. Data were extracted based on the study characteristics, sample characteristics, and protective and risk factors to mental health help-seeking patterns.

Results

Predisposing factors like female gender, higher levels of English proficiency, and history of mental illness increased the likelihood for help-seeking across several ethnic groups. Interestingly, cues to action and structural factors were under-examined. However, cues to action like having a positive social network did increase the likelihood of using formal support services among Chinese and Filipinx participants. Structural factors like lacking ethnic concordant providers and access to healthcare served as barriers for Korean and Vietnamese participants.

Discussion

The findings showed a need for ethnic tailored approaches when supporting mental health help-seeking patterns. Asian ethnic group’s immigration status, acculturation level, and psychological barriers to help-seeking should continue to be emphasized. Psychoeducational groups can be beneficial to expand the knowledge base surrounding mental illness and to link group members to culturally responsive resources.

Keywords: Asian American, Mental health, Help-seeking

Introduction

With the Asian population in the US on the rise, concerns have been raised about their mental and behavioral health issues. An important health topic that is overlooked across Asian American (AA) subgroups is mental health [1]. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Minority Health (OHM) states that suicide is the leading cause of death for AA youth ages 15–24, and Southeast Asian refugees may be at greater risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) associated with trauma before and after immigration to the US [2]. Despite alarming rates of suicide and other mental illnesses like major depressive disorder, this issue continues to be ignored in both AA adults and youths, resulting in underutilization of mental health services [1, 3]. Moreover, a study showed that a diverse sample of Asian communities identified mental health as something that an individual should have control over, and therefore, it is something that one should manage individually rather than seeking outside care [1]. This sheds light on the psychological (cognitive and emotional) factors worthy of further investigation across AA subgroups and specifically when addressing disparities in mental health care utilization [4]. The present study aims to analyze the mental health help-seeking attitudes and behaviors of AA subgroups.

Literature Review

According to the Office of Management and Budget [5], Asian people are those having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or Indian subcontinent. Mental illness disparities exist among AA subgroups. The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Minority Health (OHM) states that suicide is the leading cause of death for AA youth ages 15–24, and Southeast Asian refugees may be at greater risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) associated with trauma before and after immigration to the US [6]. Despite alarming rates of suicide and other mental illnesses like major depressive disorder, mental illness continues to be ignored in AAs, resulting in the underutilization of mental health services [1, 3]. Our understanding of AA mental health is disadvantaged by the lack of ethnically disaggregated public mental health data [6]. Although great strides have been made to disaggregate AA health data, it is important to highlight that within-group AA differences in help-seeking attitudes and behavior were reported to be inconclusive [7]. The limitations of reporting aggregated data include lack of targeted resources, inaccuracy in health profile, and inability to capture important cultural factors associated with health. Disaggregation of AA subgroups provides meaningful ways to develop culturally sensitive and effective mental health treatment programs for AA subgroups who may be at risk.

Sources of Mental Health Support

Previous studies have distinguished formal sources of support and informal support [8, 9]. Within formal support, a wide range of professions includes generalists, specialists, primary care physicians and non-health professionals (e.g., lay persons, teachers, and community

workers) [8]. On the other hand, informal support includes personal social networks like family, significant others, and friends [8]. A third source—self-help—was identified as the use of support available online and computer-mediated processes (i.e., the use of unguided website use) [8]. Although attempts to categorize sources of help have been made, it is important to understand that “formal source” and “informal source” need to be conceptualized and explained with consideration of the population group and context [8]. In this review, formal help includes both health and non-health professionals who may or may not have a specified role in the delivery of mental health care (e.g., physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, counselors, teacher, religious leader, spiritual advisor, and herbalist); informal help as social support networks like family, friends, and significant other; and other sources of help which can include self-help or digital mediated support such as unguided website use.

Distinguishing sources of support can reveal unique factors to pay attention to when promoting AA’s help-seeking patterns. Studies show that AA subgroups appear to respond less favorably to formal sources of support (e.g., physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, counselor, etc.) [1, 10] and more favorably to informal sources of support (e.g., family, significant other, friends, lay person, herbalist, etc.) [7, 11–13]. Interestingly, a study using the 2002-2003 National Latino and Asian American Study further revealed the importance of the roles of family and friends. Family is viewed to be the central social unit across AA subgroups. Therefore, family members may play a strong protective role from the onset of mental health problems [14]. For instance, when controlling for covariates, greater family support was associated with decreased odds of major depressive disorder (odds ratio [OR] = 0.63, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.48, 0.82]) and with meeting criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (OR = 0.42; 95% CI [0.27, 0.65]) [14]. This hints at the protective impacts of having family support in promoting mental health. Another qualitative study also revealed that trust-building and family-engaging approaches in service provision were critical when working with AA families [15]. Both studies underscore the importance of engaging family as critical stakeholders when aiming to improve mental health outcomes and access to services. A possible explanation for AA’s reliance on informal support networks to address their mental health needs may be due to the limited ethnic-specific or culturally anchored mental health services [15]. This corresponds with the final comments offered in a literature review that stressed actions when implementing culturally relevant, competent, and meaningful psychotherapy for patients of diverse ethnic and/or cultural backgrounds [16]. Formal support providers should tailor and adjust their professional practice on three levels: 1) technical adjustments of therapeutic methods, skills, and practices; 2) theoretical modifications to the understanding of human behavior and the nature of the mental illness; and 3) philosophical reorientation toward the nature of life and the definitions of normality and maturity, which are the goals of psychotherapy [16].

Factors Associated with Mental Health Help-Seeking

Notably, stigma has been identified as a strong predictor of an individual's decision to either seek or fully participate in mental health care [1, 17]. There is also a difference between public stigma and self-stigma. Public stigma is associated with stereotypes held by the general public about service users resulting in harm to social opportunities (i.e., employment, access to healthcare, etc.). On the other hand, self-stigma is associated with the application of stereotypes to oneself, resulting in diminished views about personal worth compounded by feelings of shame and low efficacy [17]. A study showed that perceived public stigma and anticipated self-stigma had unique impacts on the perceived importance of formal and informal care [9]. For instance, study respondents’ fear of perceived public stigma appeared to prevent respondents from viewing informal care (friends/family) as an important coping strategy, and higher levels of anticipated self-stigma had negative attitudes toward formal help-seeking from general practitioners and psychiatrists [9].

The role of the model minority stereotype (MMS) on mental health outcomes and service utilization should also be acknowledged. The MMS is a pervasive and influential stereotype experienced by AA today. This stereotype and myth depict AA as hard-working, succeeding without support from others, and establishing themselves as productive and strong contributors in their communities [3, 18, 19]. Although the term model minority may deceptively appear positive, it is important to note that this construct has been externally imposed on AA and signified that those who fell behind were due to their inferior culture and poor personal behavior. This diverts attention from institutional racism/structural inequality and denies the different historical contexts of ethnic minority subgroups and their experiences with suppression [18, 20, 21].

It has been reported that “MMS may be associated with the paucity of research related to mental health problems among AA and the troubling belief that research on AA mental health is not as important as other minority groups” [22]. Furthermore, there is some empirical evidence suggesting MMS contributes to a higher level of distress [22–25], minimization of psychological distress, and less favorable attitudes on help-seeking behavior [9, 17, 24, 26]. For example, MMS has been identified as a structural barrier that results in the presumption that AA is less likely to experience mental distress, which results in decreased linkages to mental health services [15, 27]. Another impact of the MMS is the internalization of the myth among AA group members. A study examining the association between internalization of MMS with help-seeking attitudes showed that MMS was a statistically significant predictor, B = −.10, t(102) = −2.11, p = .038 [26]. Although strides have been made to understand MMS and its impacts on AA’s help-seeking patterns, it has been suggested that in-depth information regarding stereotypes among AA is scant, especially with regards to mental health needs. Qualitative studies that allow for in-depth exploration of MMS’s impacts can be beneficial [24].

Sociocultural factors also influence ethnic group’s mental health outcomes and service use [13]. Risk factors or factors that can decrease the likelihood for service utilization include: distrust or stigma of psychiatric services [28], racial and cultural biases (i.e., culturally inappropriate services), conflicts between the etiology and characteristics of mental illness, personality syndromes, “Western” psychotherapy, values, expectations, and interpersonal styles of AA, cultural attitudes toward seeking help, language barriers [15], shortage of bilingual/culturally sensitive service providers, and lack of knowledge of existing services [13].

Conceptual Framework

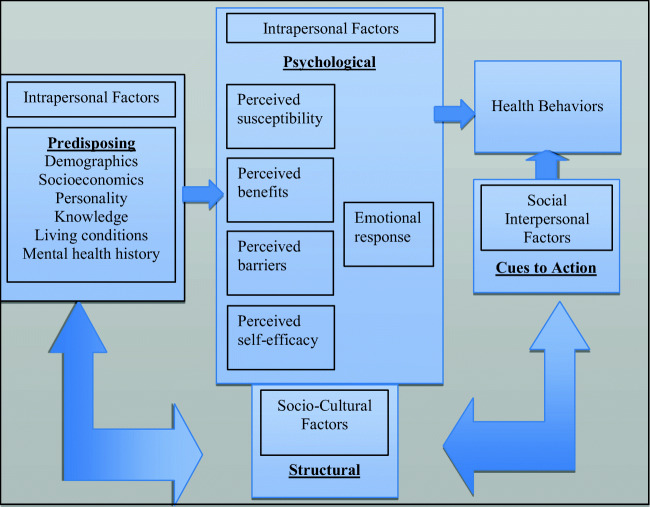

An intrapersonal-interpersonal framework of AA help-seeking processes has been examined with distinctions being offered between the: 1) cultural values emphasizing within-person elements (intrapersonal factors), 2) relational values (interpersonal factors) [26], and 3) sociocultural obstacles (e.g., racism) [27]. In this review, the aforementioned dimensions in the intrapersonal-interpersonal-sociocultural framework were conceptualized within the main constructs of the HBM. The main constructs of HBM are categorized by the following dimensions: 1) psychological (i.e., perceived susceptibility to mental illness, perceived benefits of mental health support, perceived barriers to mental health support, perceived self-efficacy of utilizing mental health support to achieve health outcome, and emotional response to mental health support) and 2) social (cues to action, i.e., public service announcements, media/educational campaigns, and social support from family, friends, or professional health providers) [29, 30]. One of the fundamental components within the Health Care Access Barrier (HCAB) Model is structural barriers. Structural barriers can exist both within the health care facility (e.g., excessive waiting times, ethnic patient and provider discordant dyads, operating hours of health care facility, continuity of care issues, and multi-step care processes) as well as externally (e.g., availability and proximity of facilities, lack of child care resources) [31]. All of which can result in barriers to accessing needed services. The structural dimension was included in this review’s conceptual model and was conceptualized as being both influenced by intrapersonal factors and influencing AA subgroups’ help-seeking processes.

Although studies have examined factors related to help-seeking among AA, few have utilized theoretical frameworks to examine factors that influence specific help-seeking [31]. The call for ongoing development and evaluation of models or frameworks of AA help-seeking processes has been made [26]. Examining the protective and risk factors to mental health help-seeking, categorized using the HBM’s constructs, can shed light on areas of focus when developing interventions to promote mental health outreach and services to AA communities. (Fig. 1: Conceptual model)

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model

Study Aims

This review has several unique components. First, to contribute to the efforts to disaggregate AA health data, specific AA subgroups will be highlighted and mental health help-seeking patterns by three sources of support (i.e., formal support, informal support, and self-help) will be examined. Secondly, protective and risk factors associated with help-seeking will be examined, categorized, and synthesized using constructs from the HBM. The primary goal of this systematic review is to address the following research question: What are the protective and risk factors to mental health help-seeking patterns among the disaggregated AA? Moreover, the present study classifies types of help.

Methods

Eligibility Criteria

Peer-reviewed articles were to meet the following inclusion criteria: 1) study conducted in the US and written in English, 2) study must evaluate factors associated with mental health help-seeking as their outcome measure, 3) AA subgroups as a disaggregated measure must be the focus in the study, and 4) there were no publication year restrictions placed. In addition, dissertation papers and conference/book abstracts were not included in this review.

Search Strategy

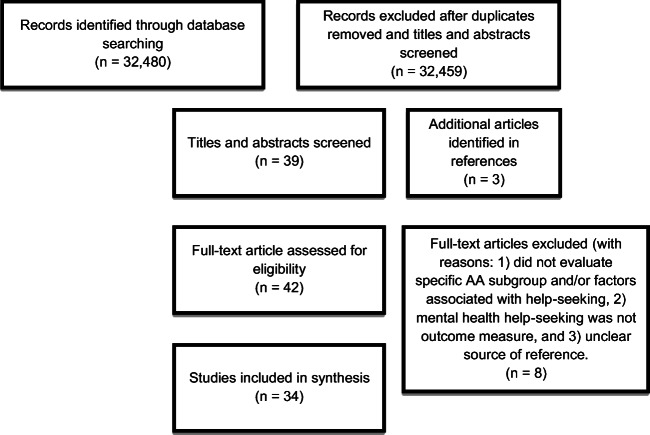

Figure 2 shows the flow diagram using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. A systematic literature review was conducted using the PRISMA guidelines and four databases in total, OneSearchManoa, two EBSCO databases (i.e., Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection), and PubMed were examined using the search string “mental health AND help-seeking.” The following AA subgroups [Chinese (CA), Filipino (FA), Korean (KA), Japanese (JA), Asian Indian (AI), Pakistani (PA), Thai (TA), and Vietnamese (VA)] American” were also included in the search to identify ethnic-specific studies. Each ethnic group was searched independently. No limits for the year of publication were set for the search, but selected studies were published in the years 1992 to 2020.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow chart

Data Extraction

The initial search was held between March and May 2020, and AA subgroups were assigned to each author. Both authors conducted independent searches which yielded the following articles across subgroups: CA (n = 16,568), FA (n = 1,788), AI (n = 10,973), KA (n = 6,361), VA (n = 3,787), JA (n = 13,518), PA (n = 1,993), and TA (n = 3,151). Duplicate articles were removed and titles and abstracts were screened for appropriateness for this review. Each author also cross-checked and discussed any studies that were in question as needed. The search yielded 38 studies (or examinations of AA subgroups) consisted of five AA subgroups: CA (n = 16), FA (n = 4), AI (n = 1), KA (n = 9), and VA (n = 8) for full text review. The subgroups, including JA, PA, and TA, were not included in the final review (n = 0, respectively). Appropriateness for full-text review was determined by screening the articles’ titles and abstracts for elements of the four inclusion criteria. Upon the completion of full-text reviews, five studies were excluded for the following reasons: 1) did not evaluate disaggregated AA subgroup and/or factors associated with mental health help-seeking patterns, 2) mental health help-seeking patterns was not the outcome variable, and 3) paper used findings from a larger study but did not explicitly cite the original study. Finally, 34 articles were included for synthesis and highlighted the following five subgroups: CA (n = 12), FA (n = 4), AI (n = 1), KA (n = 9), and VA (n = 8). Data were extracted based on the study characteristics, sample characteristics, and protective and risk factors to mental health help-seeking patterns. (Fig. 2: PRISMA flow chart)

Results

The final number of studies (N = 34) included in this review was CA (n = 12), FA (n = 4), AI (n = 1), KA (n = 9), and VA (n = 8). A total of 21 studies (61.76%) focused on East Asian

Americans (i.e., CA and KA), while 12 studies (35.29%) focused on South East Asian Americans (i.e., FA and VA), and only 1 study (2.94%) focused on South Asian American (AI). (Refer to Table 1). For each article, help-seeking source was also dismantled and examined by the following categories: 1) formal support (health professionals e.g., physician, psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, and counselor; and non-health professionals e.g., teacher, religious leader, spiritual advisor, and herbalist), 2) informal support (e.g., family, friends, and significant other), and 3) other sources of support which can include self-help initiatives (e.g., digital mediated support). In addition, a summary of protective and risk factors to help-seeking pattern across AA subgroup and by help source were identified. (Refer to Table 2).

Table 1.

Study and sample characteristics

| Ethnic group | Study | Study Design | Geographic location | Theoretical framework (yes or no) | Sample size | Age (Mean)/ Female (F) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | Leung, Cheung, & Tsui (2019) | Quantitative Survey | Houston, TX | No | N = 516 |

Age: (48.3) F = 293 (56.8%) |

| Park et al. (2019) | Qualitative | Northern CA | Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care (Aday & Andersen, 1974) | N = 15 married women |

Age: (33.2) F = 15 (100%) |

|

| Anyon et al. (2012) |

Sequential mixed methods Phase 1: secondary data analysis using 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBS) Phase 2: 2008 focus groups among students who had not accessed services from their School Health Programs. |

San Francisco, CA | No |

Phase 1: 2007 YRBS n = approx. 732 Chinese Americans Phase 2: N = 44 high school students |

Phase 1: age (NA); F = NA Phase 2: 9th grade (n=29) and 10th grade (n=15) F = (50%) |

|

| Abe-Kim, Takeuchi, & Hwang (2002) | Secondary data analysis using Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study (CAPES) | Los Angeles county | Network-episode model of help seeking | N = 1,503 |

Age: 30-49 F = (49.6%) |

|

| Spencer & Chen (2004) | Secondary data analysis using the 2-wave Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Survey (CAPES) | Los Angeles county | No |

Wave 1: N = 1,747 Wave 2: N = 1,503 |

Age: (40.1) F = 788 (52.4%) |

|

| Kung & Lu (2008) | Secondary data analysis using the 2-wave Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Survey (CAPES) | Los Angeles county | No | Only Wave 1 used. Two subsamples were examined with full sub sample consisting of N = 246 respondents with diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or somatoform d/o as a single d/o or comorbid d/o) | NA for specific subsamples. | |

| Kung (2003) | Secondary data analysis using the 2-wave Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Survey (CAPES) | Los Angeles county | No | N = 1,747 |

Whole sample Age: (37.81) F = (49.5%) Subsample with psychiatric disorder Age: (39.9) F = (48.5%) |

|

| Kung (2004) | Secondary data analysis using the 2-wave Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Survey (CAPES) | Los Angeles county | No | N = 1,747 |

Age: NA F = (49.5%) |

|

| Yee, Ceballos, & Lawless (2020) | Quantitative | 20 states recruited. Top recruitment states: Texas, CA, NY, Michigan, and OK | No |

N = 251 Texas: 168 CA: 22 NY: 12 Michigan:8 OK: 6 |

Age: 18-61 (32.6) F = (59.8%) |

|

| Chen & Mak (2008) | Quantitative | University of California system at California | No | N = 194 students |

Age: (19.7) F = 132 (68%) |

|

| Tata & Leong (1994) | Quantitative | University of Illinois at Chicago | No | N = 219 university students |

Age: (24.7) F = 117 (53.4%) |

|

| Ying & Miller (1992) | Quantitative | San Francisco, CA | No | N = 143 |

Age: (35.6) F = (49.2%) |

|

| Filipino | David (2010) | Quantitative | NA | No | N = 118 |

Age: (30.2) F = (47.5%) |

| Abe-Kim, Gong, & Takeuchi, (2004) | Secondary data analysis using Filipino American Epidemiological Study (FACES) 1998-1999 | San Francisco and Honolulu | No | N = 2,285 |

Age: 18-49 F = (50.6%) |

|

| Tuazon, Gonzalez, Gutierrez, & Nelson, (2019) | Quantitative | NA | Identity Theory (Marcia, 1980) | N = 410 |

Age: (35.5) F = 321 (78.3%) |

|

| Gong, Gage, & Tacata, (2003) | Secondary data analysis using Filipino American Epidemiological Study (FACES) 1998-1999 | San Francisco and Honolulu | No | N = 2,230 |

Age: (42) F = (51%) |

|

| Asian Indian | Turner & Mohan (2016) | Quantitative | Primary recruitment in Texas, and remainder in CA, Maryland, Ohio, and Florida | Theory of Planned Behavior | N = 89 parents |

Age: (42.4) F = 67 (75.3%) |

| Korean | Donnelly (2005) | Qualitative | respondents were recruited from a family support group in an Asian Mental Health Clinic (AMHC) located in an urban community. | Interpretive-phenomenology | N = 10 |

Age: (56.1) F = 7 (70%) |

| Han, Goyal, Lee, Cho, & Kim (2020) | Qualitative | US ("Participants were recruited from the first author’s networks”) | No | N = 11 |

Age: (33.5) F = 11 (100%) |

|

| Oh, Ko, & Waldman (2019) | Quantitative | Los Angeles, CA | No | N = 137 |

Age: (average age was approximately 30) F = 75 (55%) * The study only provides the approximate percentage instead of the exact sample size for males. The number of females was calculated based on the original study information. |

|

| Kim, Kehoe, Gibbs, & Lee (2019) | Qualitative | Southern California | No | N = 18 |

Age: (65.3) F = 15 (83.3%) |

|

| Jeong, Mccreary, Hughes, & Jeong (2018) | Qualitative | Chicago | Jorm’s (2000) mental health literacy model | N = 14 |

Age: (44.7) F = 10 (71.4%) |

|

| Jeon, Park, & Bernstein (2017) | Quantitative | New York City (NYC) or in metropolitan New Jersey | No | N = 286 |

Age: (54.4) F = 171 (59.8%) |

|

| Park & Bernstein (2008) | Review paper | NA | No | NA | NA | |

| Cheon, Chang, Kim, & Hyun (2016) | Qualitative | US (I am assuming CA because "Participants were recruited from the first author’s professional and personal networks ? | No | N = 10 |

Age: (45.5) F = 1 (10%) |

|

| Lee-Tauler et al. (2016) | A qualitative follow-up study | Geographic location; (The Memory and Aging Study of Koreans; MASK) | No | N = 8 qualitative interviews |

Age: (67.4) F = 4 (50%) |

|

| Vietnamese | Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018) | Quantitative | San Francisco Bay Area and the Greater Washington DC area | No | N = 1666 |

Age: (48) F = 973 (58.4%) |

| Ta Park, Goyal, Nguyen, Lien, & Rosidi (2017) | Mixed-methods pilot study | Northern California | No | N = 15 |

Age: (32.3) F = 15 (100%) |

|

| Ta Park et al. (2018) | Qualitative study | Northern California |

No (Cognitive Behavioral Model/programs was mentioned) |

N = 8 |

Age: (Median 52.5) F = 6 (75.0%) |

|

| Guo, Nguyen, Weiss, Ngo, & Lau (2015) | Quantitative | Mixed lower- and middle-income communities. |

The Andersen behavioral model (ABM) and the theory of reasoned action (TRA) |

N = 169 youths Vietnamese American (n=99) and European American (n=70) youth in 10th and 11th |

Time 1 survey age: (15.6) *from a sample of 427 students. The mean age for the longitudinal sample of 169 was not reported. F = NA *The study only provides the approximate percentage instead of the exact sample size for males among both Vietnamese Americans and European Americans. Authors stated that “Of these participants, 58.6% (n = 99) were Vietnamese American and 41.4% (n = 70) were European American; 46.2% (n = 78) were male.” (p. 684). |

|

| Luu, Leung, & Nash (2009) | Quantitative | Houston, Texas | No | N = 210 (195 respondents were used for the regression model) |

Age: (45.6) F = 105 (About 50%) * The study only provides the approximate percentage instead of the exact sample size for males (50%). The number of females was calculated based on the original study information. |

|

| Appel, Huang, Ai, & Lin (2011) | Quantitative |

US (a nationally representative sample from the National Latino Asian American Study (NLAAS) |

No | N = 1,097 |

Age: (41.2) F = 1097 (100%) |

|

| Leung, Cheung, & Cheung (2010) | Quantitative | Houston, Texas | No | N = 572 |

Age: (37.9) F = 267 (47%) |

|

| Nguyen & Anderson (2005) | Quantitative | A large southwestern city | No (The role of acculturation was mentioned) | N = 148 |

Age: (46.4) F = 55 (37.7% among 146 respondents) * The study only provides the approximate percentage instead of the exact sample size for the gender variable out of 146 people instead of a total sample size of 148. The number of females was calculated based on the original study information. |

Table 2.

Protective and risk factors to mental health help-seeking

| Ethnic group | Study | Protective factors | Risk factors | Sources of mental health help |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

HBM constructs (predisposing characteristics, psychological, cues to action) by source of help |

HBM constructs (predisposing characteristics, psychological, cues to action) by source of help |

|||

| Chinese | Leung, Cheung, & Tsui (2012) |

Physician: Predisposition: (male, unemployed) Friends: Predisposition (female, unemployed) Herbalist: Predisposition (unemployed, low income [<$20,001] level) |

NA |

Formal sources: “physicians,” “mental health professionals” “religious leaders” “herbal doctors” Informal sources: “Friends or relatives” |

| Park et al. (2019) |

Spouses: Predisposition (depressive symptoms) Family and friends: Predisposition (depressive symptoms) Professional help: Predisposition (depressive symptoms) |

Aggregated help: Psychological (attitude/belief about illness, stigma) Structural: (costs, language or cultural barriers, lack of/unaware of services) |

Formal sources: “professional help” Informal sources: “Family or friends” “Spouses” |

|

| Anyon et al. (2012) |

School health program: Cues to action (teacher referral) |

School health program: Predisposition (ethnicity) Psychological (externalized stigma [qualitative results: associate regular service users as being “different” or having “problems” which made them feel “awkward” about using services because they did not view themselves or their friends that way.]) |

Formal sources: “School health program” (medical care, general counseling, specialty behavioral health services) |

|

| Abe-Kim, Takeuchi, & Hwang (2002) |

Medical service: Predisposition (high family conflict) Mental health service: Predisposition (negative life events, high distress, high family conflict, no insurance) Informal services: Predisposition (high distress) Psychological (knowledge barrier) |

NA |

Formal sources: “Medical services” ([non-psychiatrist] medical doctor or emergency room) “Mental health services” (psychiatrist or other mental health specialist) Informal sources: “Informal services” (minister or priest, self-help or support groups, spiritualist, herbalist, or fortune teller) |

|

| Spencer & Chen (2004) |

Formal service: Predisposition (stress life events) Informal service: Predisposition (psychiatric disorder, female, and high stress) Structural (language discrimination) Friends/relatives: Predisposition (psychiatric disorder, high stress, and daily hassles) |

Formal services: Predisposition (Length in U.S. < or equal to 5 or 10 years) Structural (access issues) Informal services: Predisposition (single and household income $12,500 - $24,999) Friends/relatives: Predisposition (race discrimination, age, high school or GED, not having medical insurance) |

Formal and Self-Help sources: “Formal services” (psychiatrist or other mental health specialist at a health or family clinic, medical doctor in private practice, child counseling, someone at a self-help group like Alcoholics Anonymous, community program like a crisis center or calling a hotline number. “Informal services” (minister or priest including a priest in a Taoist or Buddhist temple, spiritualist, herbalist, or fortune teller). Informal sources: “Friends and relatives” |

|

| Kung & Lu (2008) |

Professional help: Predisposition (depression, anxiety, or somatoform diagnosis) Psychological (perceived social disruptiveness) Mental health professional: Predisposition (depression, anxiety diagnosis) |

NA |

Formal sources: “Mental health professional” (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, “Professional help” (medical doctors, nurses, ministers, priests at temple, and counselors) |

|

| Kung (2003) |

OR for whole sample (N=1,747): Informal help: Predisposition (female, higher education, DSM diagnosis, global severity index, higher acculturation, internal locus of control, external locus of control) Medical help: Predisposition (age, DSM diagnosis, GSI, personality trait [hardiness, challenge]) Mental health help: Predisposition (female, age, having medical insurance, GSI, higher acculturation) Alternative help: Predisposition (Gender, higher education, family income, DSM diagnosis, global severity index, higher acculturation, personality trait (hardiness, challenge) OR analyses for subsample with diagnosable psych do (N=253): Informal help: Predisposition (age, education level, global severity index, personality trait [hardiness, challenge]) Medical health help: Predisposition (older age, global severity index, personality trait [hardiness, challenge] Mental health help: Predisposition (Female, older age, having medical insurance, global severity index, personality trait (hardiness, challenge), acculturation x luck) Alternative help: Predisposition (age, GSI) |

OR for whole Sample (N=1,747) Informal help: Predisposition (age, gender x luck, acculturation x internal locus of control, acculturation x powerful other) Medical help: Predisposition (personality trait [hardiness, commitment]) Mental health help: Predisposition (married, personality trait [hardiness, commitment], gender x luck). Alternative help: Predisposition (internal locus of control, acculturation x internal locus of control, acculturation x challenge) OR analyses for subsample with diagnosable psych do (N=253): Informal help: Predisposition (older age, acculturation, personality trait (external locus of control, powerful others), personality trait (hardiness, challenge), gender x luck) Medical help: Predisposition (personality trait [external locus of control, luck]). Mental health help: Predisposition (acculturation, personality trait (external locus of control, luck), gender x self-esteem. |

Formal sources: “medical help” (medical doctors in private practice or a health plan, primary care clinic or hospital emergency room) “MH support” (psychiatrist, psychologists, social workers, counselors, or other mental health professionals) “Alternative help” (herbalist, acupuncturists, ministers, priests, monks, spiritualists, or fortune tellers) Informal sources: “Informal help” (relatives and friends) |

|

| Kung (2004) |

Odds ratio for whole sample (N=1607 sample size reduced for missing data for some predictor variables): Help-seeking: Predisposition (global severity index, higher acculturation, older age have insurance coverage) Odds ratio for subsample with DSM diagnosis (N= 224): Help-seeking: Predisposition (Global severity index, older age) |

Odds ratio for whole sample (N=1607 sample size reduced for missing data for some predictor variables) Help-seeking: Predisposition (U.S. born, married) Structural (practical barriers [cost, language, time, and knowledge of access]). Odds ratio for subsample with DSM diagnosis (N= 224): Help-seeking: Structural (practical barriers) |

Formal and Informal sources: “Help seeking” (informal sources [relatives & friends], medical sector [medical doctors, hospital emergency room], mental health sector [psychiatrist, psychologist, social workers, counselors, or other mental health professionals], and alternative sources [herbalist, acupuncturist, ministers, priests, monks, spiritualists, and fortune tellers) |

|

| Yee, Ceballos, & Lawless (2020) | NA |

Help-seeking attitude: Psychological (self-stigma) |

Formal sources: Help-seeking attitude (Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help-Short Form [ATSPPH-SF]) |

|

| Chen & Mak, (2008) |

Help-seeking likelihood: Predisposition (help-seeking history, environmental/hereditary causes of mental illness) |

NA |

Formal sources: Help-seeking likelihood (social workers or counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and university counseling centers).Help-seeking likelihood (social workers or counselors, psychologists, psychiatrists, and university counseling centers). |

|

| Tata & Leong (1994) |

Attitudes towards professional psychological help: Predisposition (higher acculturation level) Cues to action (more positive social network orientation). |

Attitudes towards professional psychological help: Predisposition (male, more individualistic [self-reliant]) |

Formal sources: Attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help (Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help Scale [ATSPPHS]) |

|

| Ying & Miller (1992) |

Attitude about professional help: Predisposition (better English, younger age, married, coming from lower socioeconomic status) Seek professional help: Predisposition (more physical symptoms and nervous breakdown, family member in treatment, and American born. |

NA |

Formal sources: Help-seeking behavior (“Have you ever consulted a doctor, psychiatrist, psychologist, or anyone else in connection with a nervous or emotional problem?”) |

|

| Filipino | David (2010) | NA |

Attitudes toward seeking mental health services: Predisposition (Asian values scales) Psychological (“loss of face”) Structural (“cultural mistrust) |

Formal sources: Attitudes toward Seeking Mental Health Services (IASMHS) |

| Abe-Kim, Gong, & Takeuchi (2004) |

Mental health professional: Predisposition (Somatic symptoms (1+symptoms), SCL-90R [Depression and other subscale items -Symptom Checklist-90-Revised 1-4.6], understanding English well) Religious clergy: Predisposition (somatic symptoms, SCL-90R, religiosity) |

Mental health professional: Predisposition (understanding Filipino well, Spirituality) Psychological (loss of face) |

Formal sources: “Mental health professionals” (psychiatrist, or other mental health specialist at a health plan/family clinic, mental health center, outpatient, general hospital, psychiatric hospital, social service agency) “Religious clergy” (minister or priest including a priest in the Taoist or Buddhist temple) |

|

| Tuazon, Gonzalez, Gutierrez, & Nelson (2019) |

Attitudes toward seeking mental health services: Predisposition (level of American cultural tendencies) Cues to action (social support) |

Attitudes toward seeking mental health services: Psychological (colonial mentality) |

Formal sources: Attitudes toward Seeking Mental Health Services (IASMHS) |

|

| Gong, Gage, & Tacata (2003) |

Lay system: Predisposition (psychological distress, psychiatric disorders, single, born in U.S., born in SF) Mental health care: Predisposition (only understands English very well, understands both English and Filipino very well, psychological distress, psychiatric disorder, General practitioner: Predisposition (only understands English very well, understands both English and Filipino very well, psychological distress, older age) Folk system: Predisposition (psychological distress, psychiatric disorder, widowed/separated/divorced, born in SF, religiosity) |

Lay system: Predisposition (only understanding English very well, understanding both English and Filipino very well, older age) Mental health care: Psychological (loss of face) General practitioner: Predisposition (currently employed) Folk system: Predisposition (higher education) |

Formal sources: “Mental health care” (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, counselor in private practice) “General practitioner” (medical doctor in private practice, health center, or primary care clinic) “Folk system” (priest or minister, spiritualist, herbalist, fortune teller) Informal sources: “Lay system” (friend or relative) |

|

| Asian Indian | Turner & Mohan (2016) |

Attitudes toward child mental health: Predisposition (mother) Psychological (higher parental attitudes of child mental health) |

NA |

Formal sources: Attitudes toward child mental health (Parental Attitudes Toward Psychological Services Inventory [PATPSI]) |

| Korean American | Donnelly (2005) |

Mental health professional: Predisposition (children's serious mental disorder) Psychological (reality of their children's serious mental disorder, failure to manage children's psychiatric symptoms) Spirituality such as prayer to God: Predisposition (children's serious mental disorder) Psychological (transcending the pain) |

Professional help: Psychological (cultural beliefs) Structural (stigma, Confucian principles) |

Formal sources: “Mental health professional” Informal sources: “Family support group and network” |

| Han et al. (2020) |

Professional Korean postpartum care: Predisposition (cultural relevance, language ability) The online social networking mechanisms: Predisposition (immigration status) Psychological (comfort) |

Professional help: Predisposing (lack of awareness of service) Psychological (cultural beliefs; a strong desire to have professional care back in home country; normalization of postpartum depression symptoms; seek mental health help from family first before considering professional help) Structural (translation services) |

Formal sources: “Professional Korean postpartum care, Sanhoo-Joerisa/Sanhoo-Joeriwon” (a person who provides postpartum care in the home in a clinic in Korea or a place for postpartum care)” Informal and Self-Help sources: “Family” “Social media and chat rooms” |

|

| Oh et al. (2019) |

Perceiving the need for treatment/seeking treatment: Predisposing (sleep disturbances were associated with greater odds of perceiving the need for treatment, and seeking treatment) |

NA |

Formal and Informal sources: “Church community” |

|

| Kim et al. (2019) |

Self-initiated efforts (Online searches in Korean): Predisposing (language) |

Professional help: Predisposing (financial status, lack of knowledge of condition, English proficiency, health insurance, financial status) |

Self-help sources: “Internet resources as form of self-help” (e.g., NAVER, DAUM search engines) Informal sources: “Family, friends, and acquaintances at church” “Support groups" |

|

| Jeong et al. (2018) |

Formal support from professionals: Psychological (motivation to help children with mental health problems) Informal support (family): Psychological (motivation to help children with mental health problems) |

Professional help: Predisposing (lack of awareness of service, language, financial, and gender role barriers (most mothers needed to receive their husbands’ approval for their children to see a physician because husbands made the money and were the ultimate decision makers about their children’s health care) to seek treatment for depression) Psychological (misconceptions about the causes and treatment, treatment takes too long without doing anything but talking) |

Formal sources: “Professionals sources” Informal sources: “Family” |

|

| Jeon et al. (2017) |

Visiting a mental health professional: Predisposing (stress) |

NA |

Formal sources: “A mental health specialist” |

|

| Park et al. (2008) |

Formal services (e.g., help from medical professionals): Psychological factor (belief that medical system is based on a holistic integration of mind and body, more socially acceptable to have bodily health problems) Mental health services: Psychological (when family members can no longer tolerate a relative's mental illness) |

Informal services (Korean Americans will often try to keep mental illness secret by involving family members rather than seeking formal intervention): Psychological (focus reporting physical symptoms rather than their emotional suffering, stigma associated with mental illness, the belief that depression is a normal part of life) |

Formal sources: “Formal services” (medical professional, herbal or acupuncture practitioner or a religious counselor; ethnic Korean churches as major sources of support, including seeking for spiritual counseling) “Mental health services (the last resort)” Informal sources: “Informal services” (family members) Self-help: “Self-help” |

|

| Cheon et al. (2016) | NA (need for changes are identified but the study did not examine the protective factors) |

Professional help: Predisposing (lack of knowledge of condition, English proficiency, lack of health insurance) Psychological (personal sense of failure, feared of rumors spreading to friends and church members) Structural (high cost, and lack of bilingual and professional counselors. discrimination, lack of family-based counseling) |

Formal sources: “A mental health practitioner” “Lay church leaders” with some level of psychology training (e.g., pastor). Self-help: “Self-managing” emotional distress appeared to be a response to having few options for professional, bilingual, and affordable mental health treatment and lack of social support. |

|

| Vietnamese American | Kim-Mozeleski et al. (2018) |

Professional help-seeking (a mental health provider and/or a family doctor): Predisposition (health insurance coverage and having a usual source of care) Preferring professional help-seeking: Psychological (perceived poor health; preferences for non-professional help-seeking options) Predisposition (health care access) |

NA |

Formal sources: “Professional” (A family doctor; a mental health professional) Informal sources: “Non-professional help-seeking options” (such as talking to friends or family, looking up information, and getting spiritual help) |

| Ta Park et al. (2017) |

Cues to action (families would play a significant role in whether they would seek help): Predisposing (severe conditions will motivate professional help as respondents’ last resort) |

Professional help: Predisposing (condition was not severe enough to warrant help-seeking, a lack of financial resources or health insurance, a lack of knowledge about their options to mental health care) Structural (stigma, lack of culturally appropriate care) Psychological (shame/ embarrassment, fear of the medication’s side effects, denial of sadness/depression, hopelessness) |

Formal sources: “Professional mental health help (from a psychologist)” “Nonprofessional mental health help (a religious or spiritual advisor like a minister, priest, pastor, or rabbi)” Formal and Informal sources: “Social support from family, friends, and church” |

|

| Ta Park et al. (2018) |

Professional help: Predisposing (established career individuals usually are more comfortable seeking professional services-such as in-home services and nursing homes-, persons from recent wave (later 80’s or later) of immigration are more willing to seek help) |

Professional help: Psychological (mental disorder is not an illness but perceived as just “stress”, stigma associated with mental health, caregivers may seek help due to stressful caregiving, but not because there is something “wrong” with them) Structural (lack of mental health resources and support in the community) |

Formal sources: “Seeking professional services” (such as in-home services and nursing homes) |

|

| Guo et al. (2015) |

Help from formal sources: Predisposing (European American adolescents, a higher number of academic stressful life events, females were more likely than males to seek support from formal providers) Informal care Predisposing (females were more likely than males to seek support from adults and peers) |

Professional help: Psychological (sense of family obligation may have prevented these adolescents from seeking help from formal sources) |

Formal and Informal sources: “Help-seeking support” (i.e., peers, adults, formal providers) |

|

| Luu et al. (2009) |

Professional psychological help: Predisposing (the more acculturation, the higher the level of cultural barriers, the older the participant, those in the professional and paraprofessional occupations). Psychological (the lower the level of spiritual beliefs, the higher the positive attitudes toward professional psychological help-seeking) |

NA (opposite of the protective factors) |

Formal sources: “Professional psychological help” |

|

| Appel et al. (2011) | NA | NA |

Formal sources: “Professionals” (general practitioner: family/general practice medical doctor, specialist: psychiatrist, psychologist, other health provider: D.O., R.N., O.T./P.T., M.S.W., counselor, other mental health provider, religious or spiritual healer) |

|

| Leung et al. (2010) |

Professional help: Predisposing (having mental health issues or family conflicts was related to talking with physicians) Informal help: Predisposing (having mental health issues or family conflicts was related to seeking advice by friends, herbal doctors, and religious consultations) Self-help: Psychological (belief that the problem would take care of itself) |

NA |

Formal sources: “Physicians” “Mental health professionals/agencies” “Herbal/non-Westernized/alternative doctors or services” “Religious consultation” Informal sources: “Informal help” (friends, family members, or relatives) |

|

| Nguyen et al. (2005) |

Professional help: Psychological (greater willingness to disclose, higher preference for professional resources over family/community resources, and higher priority placed on mental/emotional health concerns over physical health) |

Professional help: Predisposing (the greater the number of years in the U.S., the less favorable attitudes toward seeking services) |

Formal sources: “Professional” Informal sources: “Family/community” |

Chinese Americans

There were 12 studies focusing on Chinese Americans. Half of the studies (n = 6) conducted secondary data analysis with nearly all studies (n = 5) using data provided by Los Angeles County residents via the Chinese American Psychiatric Epidemiological Study (CAPES) [13, 28, 32, 33]. Two studies explicitly used a theoretical framework to inform their research: Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care [34] and Network Episode Model of Help Seeking [28]. Across the six studies, sample sizes ranged from 15 to 1747 with a fairly equal representation of males and females. A qualitative study [34] was the only study with a sample composed of 100% females. Two studies [33, 35] did not provide age information for their sample, while four studies included youths [4, 36–38]. All 12 studies examined formal sources of support, six studies examined informal sources, and one study examined other sources of support.

Formal Help-Seeking

Nearly all of the studies found predisposing factors to promote formal help attitudes or likelihood to seek help. For instance, having a history or existing mental health concerns like a DSM diagnosis, high global severity index score, depression, anxiety, or somatoform disorder symptoms, perceived high level of distress, increased the likelihood for formal help-seeking [28, 32–35, 39]. Some acculturation variables were examined and shown to increase the likelihood for help-seeking: higher acculturation level, being US national, and higher English proficiency [32, 33, 37, 39]. Psychological factors like knowledge barrier and perceived social disruptiveness [28, 35] and structural factors like language discrimination [13] were specifically shown to be associated with the use of non-healthcare professionals like a minister or priest, self-help or support groups, spiritualist, herbalist, or fortune teller. A cue to action, teacher referral [36] and positive social network orientation [37], were shown to increase the likelihood of use of a school health program which includes medical care, general counseling, specialty behavioral health services and attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help, respectively.

Various predisposing, psychological, and structural factors were found to inhibit formal help-seeking. Several predisposing factors presented as barriers: male [37], external locus of control personality trait [32] or more individualistic (self-reliant) [37], lower number of years in U.S., and lower income [13]. Psychological barrier included perceived external stigma [36] and self-stigma [38]. Structural barrier included mental health access issues [13, 33] costs, perceived language or cultural barriers, and perceived lack of services or unawareness of services [33].

Informal Help-Seeking

Four studies identified predisposing factors’ association with informal help-seeking. Three of the four studies showed that mental health concerns like having a DSM diagnosis, high global severity index score, depressive symptoms, and high stress, increased help-seeking [13, 32, 34]. Predisposing and psychological factors like older age, lower education level, no medical insurance, external locus of control personality trait, and race discrimination inhibited help-seeking from family or friends [13, 32].

Other Sources of Support

Only one to include “self-help” as their dependent variable [28], however, it was aggregated with other non-health professionals. Thus, specific associations between independent and dependent variables were deemed undetermined.

Aggregated Help-Seeking

Various psychological factors including attitudes and beliefs of mental illness and stigma inhibited help-seeking among the aggregated help sources [34]. In addition, findings showed the following structural barriers: costs, perceived language or cultural barriers, and perceived lack of services or unawareness of services.

Korean Americans

There were nine studies focusing on Korean Americans. Seven of the studies were conducted mostly in California or New York using primary data collection methods. The methodology employed in the studies varied: six used qualitative approaches, one used literature review [40] and two used quantitative data analyses [41, 42]. A limited number of studies utilized a guiding theoretical framework. Interpretive-phenomenology [43] and mental health literacy model informed one study [44]. Although the remaining studies did not explicitly use a guiding theory to inform their research questions, the concept of acculturation and Confucianism were mentioned to inform issues of mental health and help-seeking attitudes/behaviors. The number of participants in the studies varied from eight to 1118. A sample of 1118 respondents from a studywas briefly mentioned as part of the original Memory and Aging Study of Koreans (MASK) data [45], but the main focus of the study was on eight qualitative interviews. The six qualitative studies employed between eight and 18 participants. The sample sizes for the two quantitative analysis studies were 137 [46] to 286 [42], respectively. Most studies included both males and females. However, one focused exclusively on Korean immigrant women [47]. All studies focused on adult participants except for a review paper [40]. Seven studies examined formal sources of support, six studies examined informal sources, and four examined other sources of support.

Formal Help-Seeking

Predisposing factors such as socioeconomics, knowledge, and underlying mental health beliefs were characteristics of formal help-seeking attitudes or behaviors. Financial status [48], lack of knowledge of condition [45, 48], lack of awareness of existing mental health services or intervention pathways or US healthcare [44, 47, 49], English proficiency [44, 48, 49], health insurance [45, 48], and financial status [48] were associated with limited help-seeking attitudes/behaviors. Moreover, Confucian principles [49] were also a barrier to help-seeking behaviors. On the other hand, serious mental disorder conditions, cultural relevance/language ability, sleep disturbances, and stressful situations were predisposing factors associated with formal help-seeking attitudes and behaviors.

Psychological factors that seem to decrease professional help-seeking attitude/behavior included cultural beliefs such as honor/shame culture and family pride [43, 47, 49] a strong desire to have professional care back in the home country [47], stigma [40, 43], lack of trust in professionals [49], sense of failure [45], and misconceptions about the causes or treatment [44]. In contrast, the realization of serious mental health conditions motived people to seek formal help [43]. Structural factors that played as barriers in help-seeking behaviors included high cost and lack of culturally matched providers and services [49].

Informal Help-Seeking

Identified informal support was family support group and network [43, 47], church community [46, 49], friends, and internet resources [48].

Other Sources of Help

Immigrant status (predisposing factor) was associated with online help-seeking [47]. Psychological factors such as comfort were identified as protective factors utilizing online support. Gaining support through spirituality, such as prayer to God, was identified to transcend pain related to mental health [43]. One study indicated self-help was a way to deal with mental health issues because individuals need to deal with their own issues rather than burning the family [40].

Asian Indian

Only one study with Asian Indian respondents was identified that met the present study criteria for this review [50]. The researchers in this exploratory study collected primary data from Asian Indian parents, primarily from middle-aged mothers (75.28%). Participant recruitment was in Texas and the remainder from California, Maryland, Ohio, and Florida. The Theory of Planned Behavior informed this empirical study. The study examined formal sources of support.

Formal Help-Seeking

Compared to fathers, mothers (predisposition) were more likely to be open to help-seeking. Positive parental attitudes of child mental health (psychological) increased the likelihood of seeking child mental health services [50].

Filipino Americans

There were four studies focusing on Filipino Americans. Half of the studies (n = 2) conducted secondary data analysis utilizing data from the Quantitative Filipino American Epidemiological Study (FACES) [51, 52]. Sample respondents for FACES were from San Francisco, California, and Honolulu, Hawaii. One study used the Identity Theory as their theoretical framework for their study [53], with no explicit mention of the use of a theoretical framework from the other studies. Across the four studies, sample sizes ranged from 118 to 2285. One study had a noticeably higher female sample than male and uniquely integrated opportunities for their respondents to express their non-binary gender identification (e.g., transgender and non-binary identification) [53]. All of the study respondents were adults. Four studies examined formal sources of support, and one study examined informal sources.

Formal Help-Seeking

Nearly all of the studies found predisposing factors to promote formal help attitudes or likelihood to seek help. For instance, older age, having a history or existing mental health concerns like depression or other psychiatric diagnoses, somatic symptoms increased the likelihood for formal help-seeking [51–53]. Acculturation variables like higher levels of American culture and higher English proficiency levels were also shown to increase the likelihood for formal help-seeking. High religiosity and having mental health concerns (i.e., psychological distress) specifically increased the likelihood for non-healthcare professionals like religious clergy [51, 52]. Finally, having social support (cues to action) increased attitudes towards help-seeking [53].

Predisposing factors associated with the likelihood for formal help-seeking or related attitudes included having higher Asian values, a good understanding of Filipino, and having high spirituality [51]. Psychological factors like perceived “loss of face” and colonial mentality [53] were identified as barriers.

Informal Help-Seeking

One study found that the following predisposing factors: single status, born in the US, and mental health concerns (i.e., psychological distress or psychiatric disorders) increased the likelihood to seek help from family or friends [52]. In turn, older age and high English proficiency decreased the likelihood for informal help-seeking [52].

Vietnamese Americans

There were eight studies focusing on Vietnamese Americans. Seven of the studies used quantitative analysis, and one was a mixed-method study. The quantitative data analysis approach varied: logistic regression analysis [54, 55], multinomial logistic regression analysis [56], multiple regression analysis [57], descriptive/Chi-square tests [58], and correlation/regression [59]. One qualitative study conducted semi-structured interviews and applied content analysis [60]. California and Texas were representative states in Vietnamese American studies. Except for one study, which focused on youth [56], the age of participants ranged from their 30s to 50s. The aforementioned youth study used two theoretical models to understand help-seeking behaviors among adolescents: the Andersen behavioral model (ABM) and the theory of reasoned action (TRA). Sample sizes ranged from eight to 1666. Some studies had a balanced number of men and women [54, 56, 57], while other studies focused on women only [58, 60]. Another study had more women than men [60], and another study had more men than women [59]. All of the studies examined formal sources of support, and five studies examined informal sources.

Formal Help-Seeking

Among Vietnamese Americans, formal help from educators and mental health professionals (i.e., counselors, psychologists, social workers, doctors) was identified [56, 58].

Predisposing risk factors included lack of financial resources or health insurance [60], a lack of knowledge about their options to mental health care, and the greater number of years in the US [59]. On the other hand, predisposing protective factors included severe mental health conditions or mental health issues and established careers. However, there was a mixed finding related to the role of acculturation. One study found that the recent wave (80s or later) of immigration [60] was positively associated with help-seeking, whereas another study found that a positive association between acculturation and attitudes towards professional help-seeking [57].

Psychological protective factors such as perceived poor health [54], willingness to disclose, higher preference for professional resources over family/community resources, and prioritizing mental/emotional health concerns over physical health were identified [59].

Structural protective factors included health insurance coverage and having a usual source of care and access to health care [54].

Informal Help-Seeking

Informal support was provided by friends, significant others, family, and religious/spiritual leaders. Predisposing protective factors included being females [56] and the presence of underlying mental health issues [55].

Other Sources of Help

Self-care and motivation from family played a role in help-seeking attitudes and behaviors. For instance, the belief that the problem would take care of itself [55] and cues to action from family played a role in help-seeking [60].

Discussion

This review highlighted different sources of support that are being investigated in AA help-seeking studies, as well as shed light on varying factors that influence help-seeking. Across AA ethnic subgroups, the studies focused on individual-level factors’ (predisposing or psychological variables) relationship with mental health help-seeking patterns. This calls attention to the need for a comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment and for a tailored approach when working with AA subgroups. Interestingly, religiosity and/or spirituality was investigated only for Filipino Americans and Vietnamese American [51, 57]. This is a surprise since many AA identify with a religious identity [61]. It has been noted that most mental health practitioners lack formal training in religion and spirituality; and efforts are needed to work effectively with religious leaders to promote mental health needs in their communities [51]. One example of this is a study exploring how Catholic priests’ perceived their own barriers to mental health help-seeking and showed that the priests perceived counseling as “helpful, supportive, and healing” and that receiving recommendations from another priest, friends, or others in their personal network helped initiate their help-seeking behavior [62]. This hints at the potential benefits of traditional mental health providers strengthening their allyships with religious clergy to support Filipino American’s mental health needs. The psychological variables identified in this review (e.g., external stigma perceived social disruptiveness for Chinese Americans and loss of face for Filipino Americans), corresponded with some of [63] five factors that hinder the help-seeking process: social stigma, treatment fears, fear of emotion, anticipated utility and risks, and self-disclosure. Notably, when structural and/or cues to action variables were examined (i.e., language/cultural discrimination and costs), they were done primarily for the studies examining Chinese Americans’ formal help-seeking. Researchers argued that the model minority stereotype may need to be dispelled across all stakeholders in AA mental health care, in addition to recruiting a more diverse and culturally competent workforce, help-seeking patterns may improve [64]. Similarly, Korean Americans and Vietnamese Americans identified structural barriers such as stigma, high cost, and lack of culturally sensitive services playing an important role in help-seeking attitudes and behaviors. Future studies should continue to examine the structural and cues to action factors that can promote or hinder mental health help-seeking patterns for other AA ethnic subgroups as well. More variables should be investigated to clarify the relationship between protective and risk factors and mental health help-seeking patterns, which goes beyond help-seeking attitudes but includes the behavior itself.

A theme that arose while conducting this review was that there was some overlap in terms of how researchers conceptualized and operationalized constructs of interest in their studies. All of the studies included the examination of “formal support” in their analysis, and 44.1% (15/34) studies included “informal support” in their analysis. Only one study [33] did not disaggregate support sources and instead aggregated “help seeking” to include various professionals and across sectors. Across studies, formal support was generally defined similarly and included health professionals like physicians, psychiatrists, psychologists, and clinical social workers. There was some variability regarding how informal support was conceptualized. For instance, several studies categorized other non-health professionals (i.e., clergy members, spiritualists, herbalists) as informal sources of support [13, 28], as alternative help [32], or as folk systems [52]. The operationalization of the different sources of help warrants further clarification with respect to ethnic and cultural contexts [8]. Additionally, informal mental health help-seeking patterns as dependent variable warrants continued investigation because AA may be more likely to rely on informal support networks to address their mental health needs [13]. In a qualitative study, the respondents were AA individuals who were sought out by other individuals with mental health problems, and they confirmed the need for mental health services for AA and further discussed the importance of engaging family members in service provision [13].

Interestingly, only six studies included other sources of support in their study, and they were examined in the Korean American studies [13, 28, 40, 45, 48]. One study identified online sources as self-initiated efforts [48], and another study found online social networking as a source of help [44]. However, it was unclear how self-help was conceptualized in one study as it was categorized within “informal sources” along with minister or priest, support groups, spiritualist, herbalist, or fortune teller) [51], while another study specified “self-help” groups like Alcoholics Anonymous [13]. In the current digital era and in light of the current pandemic Covid-19 that has resulted in severe disruptions in everyday lives, self-help efforts (computer-mediated and/or unguided website use) aimed at promoting mental health should be investigated more closely. The immense number of resources, information, and live support offered online should be investigated and with regards to its relevance and applicability of e-mental health services to ethnically and racially diverse populations [65]. E-mental health services like web-based psychological interventions with or without therapist support, smartphone applications, and online counseling increased reach and scope to mental health support [8, 65]. This may be a more acceptable approach to addressing mental health concerns and/or expanding the types of mental health support utilized by AA ethnic subgroups.

The findings from this review should be understood in the context of their limitations. As such, the following recommendations for future research are offered. First, the search strategy used in this review may have resulted in articles being missed and therefore not included in the analysis. Future researchers should aim to use librarian support services to support the search strategy and identify more search terms to optimize the result. Second, the majority of the studies in this review employed a cross-sectional design which limits the impact of time on the variables of interest. Additional methodologies should be employed to triangulate findings and increase external validity. Third, out of the 34 studies in this review, only seven studies (20.6%) explicitly used a theoretical framework to inform their research. Theoretical framework can guide understanding of phenomena by providing an organized approach for bringing together observations and facts from separate investigations, assisting in summarizing and linking findings into an accessible, coherent, useful structure, and providing a basis for prediction [65]. The Cultural Determinants of Help Seeking (CDHS) is a theoretical model that synthesized theoretical concepts and has been argued to have implications for cross-cultural health promotion, primary health care, and psychiatry [66]. However, it is important to note that the CDHS emphasizes the cultural determinants of help-seeking as it affects aspects of health and illness, including the perception of, the explanation for it, and the behavioral options to promote health or relieve suffering [66]. The structural barriers that hinder access to care for diverse cultural groups are a missing construct in CDHS [66]. The reasons for the small number of studies using a theoretical framework in this review warrant investigation. Continued testing of relevant mental health help-seeking theories should be explored by researchers and expanded to more accurately explain AA mental health help-seeking patterns. Fourth, intervention studies should be increased in this area across AA ethnic subgroups. Although a systematic review and meta-analysis of 98 studies conducted in English, German, and Chinese showed that help-seeking interventions do improve attitudes, intentions, and behaviors for formal help-seeking, no evidence for effects on informal help-seeking, and facilitates the use of self-help programs or materials [67], it is unclear the extent that this finding is generalizable nor applicable for AA ethnic subgroups. Lastly, it is important to acknowledge non-significant predictors of help-seeking behaviors varied by studies such as gender [54, 57, 59], geographic location [54], family obligation, emotional restraint [56], stigma, and traditional beliefs [59].

Since the passing of the Community Mental Health Centers (CMHC) Act, 1963, mental health care in the community has been broadened [68]. Yet, there are a limited number of mental health services targeted for diverse Asian American community members who may be experiencing added challenges such as limited English proficiency and poverty. The present study findings suggest that cues to action from close family and friends encourage people to think about the help-seeking process for some AA subgroups positively. Thus, psychoeducational groups in the community and efforts from the local mental health agencies to promote family or group therapy sessions and education may plan a significant role in improving help-seeking patterns. Because each minority group has different historical experiences and help-seeking culture, culturally appropriate resources and services are essential. Moreover, the present study informs future research in several ways. First, researchers need to use theoretical frameworks to inform their studies. Second, studies should explore inter-and intra-differences among Asian ethnic subgroups.

The systematic review results indicate the importance of understanding the impact of predisposing characteristics, psychological-perceived barriers, structural factors, and cues to action on various help-seeking behaviors among AA subgroups. Disaggregating ethnicity is important to inform not only practice but also policy decisions. There is a socio-cultural complexity of mental health and help-seeking behavior among Asian Americans. Practitioners, policy-makers, and researchers using disaggregated data will provide a better understanding of the mental health-seeking patterns among Asian Americans. Thus, it will allow stakeholders to play a meaningful role in developing more effective interventions to improve help-seeking patterns.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sophia Bohun Kim, Email: sophiabk@hawaii.edu.

Yeonjung Jane Lee, Email: yeonjung@hawaii.edu.

References

- 1.Lee S, Juon H, Martinez G, Hsu CE, Robinson ES, Bawa J, Ma GX. Model minority at risk: Expressed needs of mental health by Asian American young adults. J Community Health. 2009;34(2):144–152. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9137-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health. Mental and behavior health - Asian Americans. n.d.. Retrieved by https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=54#1. Accessed 29 May 2020.

- 3.Sue DW. Asian-American mental health and help-seeking behavior: Comment on Solberg et al. (1994), Tata and Leong (1994), and Lin (1994) J Couns Psychol. 1994;41(3):292–295. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.41.3.292. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen SX, Mak WWS. Seeking professional help: Etiology beliefs about mental illness across cultures. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55(4):442–450. doi: 10.1037/a0012898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of Management and Budget. Revisions to the Standards for the Classification Of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Federal Register: 62: No.210, October 30. 1997.

- 6.Fang JS. Asian American, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and the American mental health crisis. Asian American Policy Review. 2018;28:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheu H, Sedlacek WE. An exploratory study of help-seeking attitudes and coping strategies among college students by race and gender. Meas Eval Couns Dev. 2004;37(3):130–143. doi: 10.1080/07481756.2004.11909755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rickwood D, Thomas K. Conceptual measurement framework for help-seeking for mental health problems. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2012;5:173–183. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S38707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pattyn E, Verhaeghe M, Sercue C, Bracke P. Public stigma and self-stigma: Differential association with attitudes toward formal and informal help seeking. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):232–238. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin H, Wardenaar KJ, Xu G, Tian H, Schoevers RA. Help-seeking behavior among Chinese people with mental disorders: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):373–384. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2316-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen JA, Hung GC, Parkin S, Fava M, Yeung AS. Illness beliefs of Chinese American immigrants with major depressive disorder in a primary care setting. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;13:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung P, Cheung M, Tsui V. Help-seeking behavior among Chinese Americans with depressive symptoms. Soc Work. 2012;57(1):61–71 http://search.proquest.com/docview/1018365404/. Accessed 29 May 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Spencer MS, Chen J. Effect of discrimination on mental health service utilization Among Chinese Americans. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):809–814. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.94.5.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangalang CC, Gee GC. Depression and anxiety among Asian Americans: The effects of social support and strain. Soc Work. 2012;57(1):49–60. doi: 10.1093/sw/swr005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weng SS, Spaulding-Givens J. Informal mental health support in the Asian American community and culturally appropriate strategies for community-based mental health organizations. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership, and Governance. 2017;41(2):119–132. doi: 10.1080/23303131.2016.1218810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tseng W. Culture and psychotherapy: Asian perspectives. J Ment Health. 2004;13(2):151–161. doi: 10.1080/09638230410001669282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawai Y. Stereotyping Asian Americans: The dialectic of the model minority and the yellow peril. Howard J Commun. 2005;16:109–130. doi: 10.1080/10646170590948974. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong F, Halgin R. The “model minority”: Bane or blessing for Asian Americans? J Multicult Couns Dev. 2006;34:38–49. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00025.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shih KY, Chang TF, Chen SY. Impacts of the model minority myth on Asian American individuals and families: Social Justice and critical race feminist perspectives. J Fam Theory Rev. 2019:412–28. 10.1111/jftr.12342.

- 21.Yoo HC, Burrola KS, Steger MF. A preliminary report on a new measure: internalization of the model minority measure (IM-4) and its psychological correlates among Asian American college students. J Couns Psychol. 2010;57(1):114–127. doi: 10.1037/a0017871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng AW, Chang J, O’Brien J, Budgazad MS, Tsai J. Model minority stereotype: Influence on perceived mental health needs of Asian American. J Immigr Minor Health. 2017;19:572–581. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-04400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assalone AE, Fann A. Understanding the influence of model minority Stereotypes on Asian American community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 2017;41(7):422–435. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2016.1195305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]