Abstract

The ultimate means of functional restoration of joints with end stage arthritis is prosthetic replacement. Even though there is reluctance to replace the joint of a younger individual, the mean age of joint replacement continues to decrease. This is due to three factors: 1) social expectations, 2) uncertainty with many joint preservation procedures and 3) the ever-increasing reliability and longevity of prosthetic replacement. Unfortunately, the elbow does not share in these advantageous trends to the extent as is the case for the hip, knee and shoulder. Social pressure for restoration of normal or near normal function is certainly present, but the desired improvement of longevity and fewer restrictions of activity have not been documented. Hence, possibly somewhat disproportionately to other joints, there is great need for a reliable and functional non replacement joint reconstruction option. For most other joints, fusion is the ultimate non replacement option. Further, for most joints an optimum position has been defined to allow the greatest chance of normal function of the individual. Unfortunately, there is no truly ‘optimum’ functional position of elbow fusion, and the recommended 90° of flexion is considered the ‘least worse’ position. Further, unfortunately, elbow fusion dysfunction cannot be mitigated by compensated shoulder motion. Hence, while there is little experience in general with interposition arthroplasty of the elbow, in the authors' opinion it remains the treatment of choice in some individuals and in certain circumstances for the reasons explained above. In our judgment, the reason for avoiding this procedure is that it is technically difficult, the absolute frequency of need is not great, and outcomes do appear to be a function of experience and technique. Based on these considerations, in this chapter we review the current indications and assessment and selection considerations. Emphasis is placed on our current technique with technical tips to enhance the likelihood of success and longevity. We conclude with a review of expectations based on current literature.

1. Introduction

Elbow arthropathy in the younger patient is a particularly complex challenge to manage.1 Elbow stiffness and pain can be disabling, and the functional loss is difficult for which to compensate. When nonoperative management fails, surgical treatment is predicated on finding a solution that is sustainable for many years and does not preclude an active lifestyle. Options include fusion, open contracture release, arthroscopic debridement/contracture release, interposition/distraction arthroplasty, and prosthetic replacement. Interposition arthroplasty was historically a modification of simple resection arthroplasty of a joint. The addition of a local tissue or skin to prevent painful contact between the ends of the resection evolved into a strategy of creating a biological membrane over an arthritic joint surface that might otherwise be considered for prosthetic replacement. Interposition arthroplasty in the elbow is particularly well suited for cases where the majority of the cartilage surface is of poor quality with limited viability for nutrition and remodeling, but the overall alignment is acceptable, and the condylar origins of the collateral ligaments have remained intact.2

2. Indications/selection

Interposition arthroplasty is equally effective for inflammatory and post traumatic arthritis.3 Interposition arthroplasty is indicated for patients from the time of skeletal maturity up to essentially any age if the patient's activities are of high enough demand to render prosthetic arthroplasty a risk for failure. Patients with severe arthritis under the age of 60 should be considered for interposition arthroplasty preferentially over prosthetic replacement unless there are mitigating factors that make an alternative procedure safer or more likely to succeed. Selection considerations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of factors considered when selecting appropriate procedure as a function of patient and disease characteristics.

| Stage | Rheumatoid Arthritis | Post Traumatic Arthritis |

|---|---|---|

| Mayo 1/soft tissue inflammation | Medications, nonoperative, injections, joint synovectomy and debridement | Medications, nonoperative, injections, joint synovectomy and debridement |

| Mayo 2/joint erosions and narrowing | Medications, nonoperative, injections, open vs arthroscopic joint synovectomy and debridement | Medications, nonoperative, injections, open vs arthroscopic joint synovectomy and debridement, hardware removal, nerve decompression |

| Mayo 3/significant joint narrowing, architectural changes | Age <60 Interposition vs Total Elbow Arthroplasty (TEA),> 60, TEA | Age < 60 Interposition arthroplasty (with hardware removal, heterotopic bone removal, nerve decompression), >60 shared decision |

| Mayo Stage 4/Severe joint destruction, pain instability | TEA | Age < 60, High demand -Interposition arthroplasty, If stabilization possible (with hardware removal, heterotopic bone removal, nerve decompression), TEA when instability not reconstructible or > 60 and low demand |

3. Contraindications

There are absolute and relative contraindications to interposition arthroplasty. The major absolute contraindication for interposition arthroplasty is the presence of infection. Treatment of infection is best done with resection and debridement and possibly with an antibiotic spacer. Resection for infection alone can be complemented with the use of the same hinged external fixator used in interposition arthroplasty but not the use of an implant or interposition. The other common absolute contraindication is gross instability with significant bone loss precluding ligamentous reconstruction. Another major contraindication is flaccid weakness of the extremity or neurological compromise.

The two relative contraindications of classical concern for interposition arthroplasty are: a) pain at rest and b) significant pre-operative instability.4 Additionally, full or functional arc of motion (flexion extension arc of 100°, protonation/supination of 50°) which is painful suggests a decreased likelihood of improvement with interposition as a bearing surface solution.

4. History

Obtaining a detailed history is critical for proper decision making and planning. A timeline of disease progression and prior treatments should be constructed. Documentation of an adequate trial of nonsurgical care should reveal efforts at bracing, activity modification, lifestyle changes, and medications. Post traumatic cases require careful elucidation of the original injury (presence of open fracture, prior infections, and previous surgeries). Nerve complaints and prior nerve procedures can affect the prognosis and may require revision of prior neurolysis or transposition. History of previous organisms and prior antibiotics are most important in cases where infection has been a concern. The prior operative notes are to be obtained whenever possible and the description of previous surgical approaches and the presence of a nerve transposition are helpful. Knowledge of the manufacturer of retained implants should is essential to prepare for the logistics of hardware removal which can be one of the most challenging aspects of post traumatic surgery.

5. Expectations

Expectations in the consultation process play a major role in patient satisfaction and in the success of interposition arthroplasty. The patient's activity level is not as restricted as a prosthetic arthroplasty (5–10 pounds lifting), but strenuous manual labor or vigorous sporting activities are not recommended. Interposition arthroplasty remains a salvage procedure and the potential for early failure increases with unwillingness to adhere to these guidelines. Patients may be better suited to fusion or continued bracing if they require additional years of high demand activity. Additionally, the patient must be aware of the high likelihood of revision procedures later in life including revision interposition or prosthetic replacement. Both secondary procedures have been shown to be successful and reliable. Awareness of the potential for successful revision can increase patient acceptance of interposition as their best option for the current phase of life.5

6. Physical examination

Physical Examination should begin with a careful assessment of the quality of the soft tissue sleeve. Redness, swelling, drainage, and fluid collections are concerns for infection and may mandate preoperative aspiration and infection work up. The location and enumeration of prior surgical scars and areas of adherence should be noted. In some, consultation with a plastic surgeon for pre-operative flap coverage is indicated, especially given that many patients may ultimately require additional procedures after interposition as an intermediate stage. Range of motion with a goniometer should be obtained and the character of endpoints (hard vs soft) should be noted along with any spasticity. Palpation of the joint line should be specific and include radiocapitellar pain and terminal pain vs midrange pain assessment. Any ligamentous instability including varus/valgus and rotatory instability should be documented. The status of biceps/brachialis and triceps function can be measured by manual motor testing scales. Peripheral nerve function and provocative nerve testing specifically of the ulnar and radial nerves are needed as these nerves are often part of the surgical dissection.

7. Imaging

Traditional x-rays with contralateral films should be obtained. Important elements in available conventional imaging include the quality of the articular surface, amount of joint narrowing, the presence/location of heterotopic ossification, the degree of angular deformity, joint instability, and major areas of bone loss.

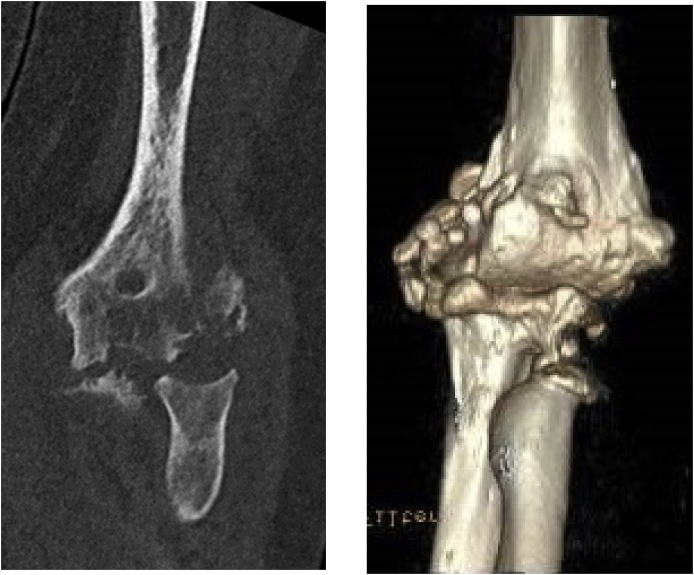

CT/3D CT can be of value in select case where complex deformity is present and precise measurement of coronal, sagittal, or rotational deformity is necessary (Fig. 1). MRI may assist with determining the presence of infection, bone marrow changes or residual infection as well as the status of the collaterals, biceps, and triceps. In some cases, bone scans for infection assessment may be indicated. Laboratory studies should include baseline infection labs (CBC, CRP, ESR) and may require aspiration as well. EMG/NCV can determine the pre-operative status of at risks nerves.

Fig. 1.

Cystic change on the CT scan can help the surgeon understand if interposition is a viable option. Patients with cystic changes of the distal humerus are not good candidates as the subchondral support for the graft is absent which can lead to collapse and subsequent instability.

8. Decision/discussion

As with all elective procedures, the risks and benefits are carefully reviewed. It is essential that the goal of the patient is understood and revisited at the time of the decision to go forward. The clearest way to assure the needs of the patient are understood is to frame the question. “If I can only relieve pain, but with restricted activity, or allow near normal activity but with some residual pain, which of the two outcomes would you prefer.” The answer to this question is often the variable that determines the final endpoint in the decision tree between interposition and prosthetic arthroplasty. The patient must be educated on the arithmetic of outcomes in an easily comprehensible fashion. The parallels between interposition and prosthetic arthroplasty are conveyed by the similarity in survivorship, outcome measures (Mayo Elbow Performance Scores (MEPS), and complication rates.5 Ultimately the patient must also be prepared for the consequences of failure for whatever options they choose and be prepared to accept them and their residual solutions.

9. Preoperative planning

This is a very important step and must include assurance of the availability of the graft to be used. We prefer an Achilles tendon allograft.3 It easily covers the entire distal humerus and can be used to augment the collateral ligament repair. A discussion regarding the use of an external or internal fixator is essential. While we continue to feel that it is of great theoretical and practical value, experience had demonstrated that it is not essential in every case. Nonetheless, we do have it available in all cases.

Similarly, out of an abundance of caution, we also have a prosthesis available should this be necessary. We have yet to abandon an interposition once started, on occasion we make the final decision after exposure and assessment of the pathology. Finally, if any concern exists regarding the potential healing of the surgical incision, a consultation with a plastic or hand surgeon is arranged.6

10. Procedure7

Positioning is determined by the position used for ORIF of distal humeral fractures. We prefer supine with the sterile arm brought across the chest.

A strait posterior incision about 15–20 cm, depending on the degree of scarring and stiffness is preferable. As with any revision procedure efforts are made to use any prior incision, but this must allow the procedure to be performed without compromise of exposure.

Full thickness skin flaps are raised laterally and medially to the epicondyles. Great care is exercised to identify and protect the ulnar nerve early in this step. We typically partially release the nerve, but generally do not transpose it unless it appears compromised by the subluxation of the ulna. But, If the nerve is symptomatic preoperatively, it is released and moved subcutaneously at this time, and protected throughout the remainder of the procedure.

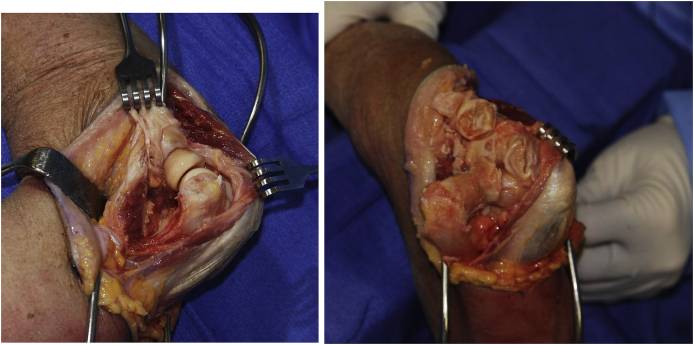

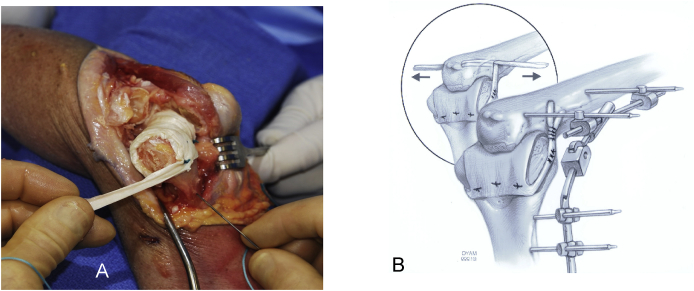

We have always preferred a triceps sparing approach. Details have been well described elsewhere.2 For interposition the lateral collateral ligament is detached, and the ulna is rolled off the humerus hinging on the preserved medial collateral ligament (Fig. 2). It is essential to inspect the nerve when fully exposed to assure that it is not compromised by this maneuver. The radial head is preserved if at all possible, to enhance articular contribution to stability.

Fig. 2.

A triceps preserving approach is favored. An extensile modified Kocher that releases the lateral collateral ligament and about 20% of the lateral triceps attachment (A) permits the radius and ulna to be rotated medially providing adequate exposure of the distal humerus while preserving the medial collateral ligament (B).

Humeral preparation: We attempt to preserve some contour that can also provide some articular stability. It is of paramount importance to preserve the strong subchondral bone to avoid resorption, but at the same time the preparation must also allow for punctate bleeding of the humeral articular surface.

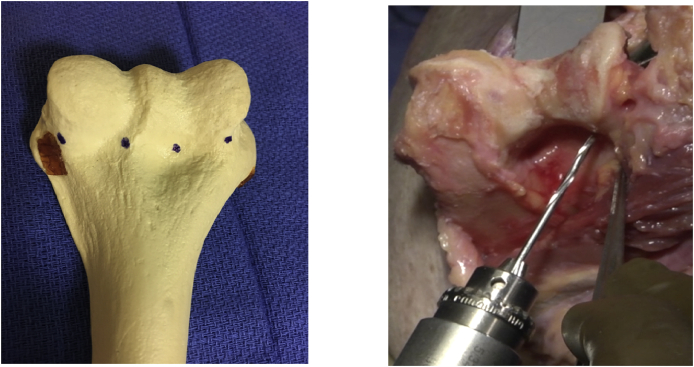

Application of the allograft: The thickest part of the graft should be in the greatest load bearing part of the trochlea. Sutures are placed in the graft in a way to insure they are aligned with the holes placed in the humerus. Drill holes are made from back to front and through the medial and lateral margins of the distal humerus followed by two equally spaced holes roughly mid trochlea, and at the incisura trochlearis (Fig. 3). The sutures are drawn through the drill tunnels from front to back and secured to the graft posteriorly (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Four drill holes are made taking care to assure the medial and lateral most tunnels diverge from posterior to anterior to assure cover the entire width of the distal humerus.

Fig. 4.

By placing the posterior suture slightly distal to the tunnel the graft will be drawn taught when the suture is tied.

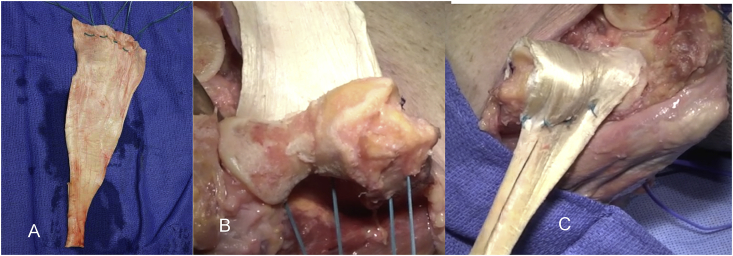

Collateral ligament(s): Collateral ligament integrity is essential. If there is good tissue, the ligament is discretely repaired with a running locked stitch. But if the tissue is inadequate, the repair is reinforced with a portion of the Achilles allograft fashioned to reconstruct the lateral complex (Fig. 5). If both collateral ligaments must be reconstructed, a strip is harvested from the medial and lateral excess tissue margins and brought through a tunnel connecting the sublime tubercle and the tubercle of the supinator crest. We term this a “loop” or “sling” reconstruction (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

To assure collateral integrity, strips are fashioned from the excess graft (A) and attached to the anatomic flexion axis. The graft then reinforces the deficient collateral ligament. If both sides are deficient a “sling” or “loop” reconstruction is performed by creating a tunnel between the sublime tubercle medially and the tubercle christus supinatoris laterally and secured to reinforce each ligament (B).

Articulated external fixator (ExFix): We use this as it allows protection of the collateral ligament healing and by separating the ulna it avoids sheer stress on the graft or strain on the collateral ligament repair/reconstruction while allowing active motion. Furthermore, at the time of removal we perform an examination of the elbow. This examination assesses smoothness of the flexion arc, ligament stability and we stretch the joint in flexion and in extension to facilitate regaining motion.8 While the senior authors prefer the DJD ll from Stryker for its simplicity and effectiveness (no royalties currently received), any articulated fixator, internal or external can be effective.9

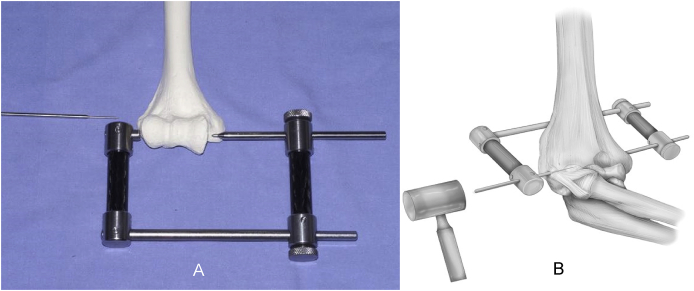

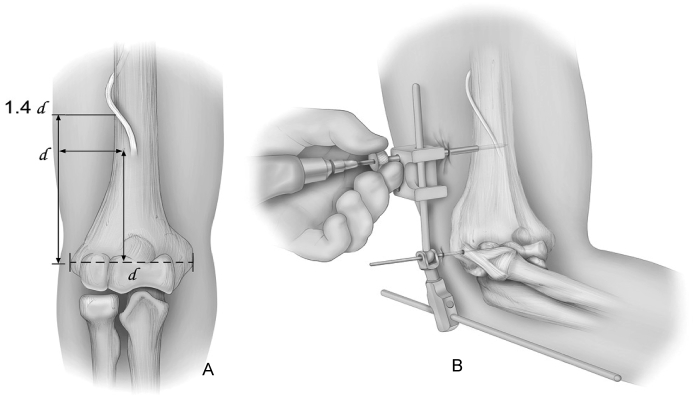

Technique (DJD II): A smooth Steinman pin – diameter of the rod of the ExFix - is tapped in place using the targeting device to assure replication of the axis of the flexion/extension arc (Fig. 6). The outrigger of the ExFix device is placed over the axis pin. The humeral arm of the fixator is aligned with the anterior cortex of the humerus. The proximal humeral half pin is placed by palpation or under direct vision through the open wound. It is important to place the proximal pin no more than one epicondylar axis length proximal to the flexion axis. The radial nerve is further proximal by about 40% of that distance (Fig. 7).10 For additional protection, tissue protector should be used with the proximal humeral pin placement.

Fig. 6.

A guide is helpful to introduce the axis pin for the articulated external fixator laterally(A). The stylus is inserted with a mallet, avoiding potential suture cut out caused by a drill (B).

Fig. 7.

The radial nerve is at risk if the proximal humeral pin is more proximal than 1 epicondylar width (A). Tissue protecting trocars are also used in the placement of the humeral pins (B).

Post application: AP and lateral films are taken to confirm joint integrity; distract 2–4 mm; examine and document the flexion arc before and after application of the external fixator.

11. Post procedure

While the patient is encouraged to use this extremity as tolerated, no formal therapy is prescribed except as may be needed for the hand or shoulder.

11.1. Three weeks and beyond

Examination under anesthesia: This is an important step as noted above. The patient is placed under sedation or a brief general anesthesia, and the external fixator and sutures are removed, and the elbow is ‘examined’.(8) Stability and smoothness of passive motion is assessed and documented. Importantly, the elbow is then stretched to the flexion arc attained at surgery. Further rehabilitation is to actively use the arm as tolerated, employing a Mayo elbow brace to protect and provide flexion and extension torque to attain motion gained at the examination. A second ‘examination’ may be performed if progress is not being made at 6–8 weeks. We typically follow patients for, a minimum of one and ideally 2 years after surgery.

12. Results, expectations

As is always the case, when reviewing outcomes of interposition arthroplasty, indications, cohort size, techniques, thoroughness and duration of the surveillance - all vary widely based on the nature of the prevalent pathology and the affluence of the society. Interposed materials also vary widely and today consist primarily of cutis, anconeus, fascia lata, triceps facia autografts and Achilles and cutis allografts. One of the most interesting studies in the last two decades from Sweden reported 35 procedures for rheumatoid arthritis. In spite of 21of 28 (75%) followed for a mean of 6 years with satisfactory outcomes, the authors conclude that total elbow is the treatment of choice for rheumatoid arthritis.11

More recent studies are typically with small cohorts and markedly varying results. Ahmed et al.12 reported 18 elbows from 2010 to 2015 with arthritis from trauma, inflammatory disease and sepsis. These patients were treated with interposition arthroplasty using abdominal dermal autograft. The average age was 34.3 years with an average follow-up of only 22 months (maximum 50 months). These patients had a posterior long arm splint in 90° flexion and mid prone position for 2 weeks instead of a hinged external fixator, followed by range of motion exercises. Pre-operative flexion averaged 25° which improved to 120° (P < 0.01). Preoperative MEPS of 45 increased to 95 (p < 0.01). Post-operatively, 14 rated there results as excellent and 4 as good.

Ersen et al.13 presented a small series from Turkey, of 5 patients with Achilles allograft interposition done between 2001 and 2010 with a mean follow up of 87.6 months. They report good outcomes with improved average post-operative MEPS at 71 (25 pre-op). Range of motion improved from 24° flexion arc to 81° post operatively. There were no revisions. These exceptional results are in contrast to most of the recently reported experience. For example, Laubscher14 in 2014 reported 17 patients of mean age 41 years and followed for a mean of 54 months, 15 cases underwent at least one re-operation. There were seven revisions, in which 4 were converted to total elbows, 2 were converted to arthrodesis and one opting for a revision interposition. The average time to revision/conversion was 23 months. Of the remaining 10 patients that maintained the original interposition, there was improvement in VAS scores from 7.4 to 2.4 and mean MEPS from 42 to 76 points. This parallels our experience, specifically, if the interposition is doing well at one year, most will continue to do well for 10 or so years. Failures are usually identified within one year of surgery.

Recently, Iyidobi et al. from Nigeria explored a series of 16 very young patients of average age 22.8 years with nine males and seven females who underwent interposition with autologous triceps fascia between 2009 and 2017.15 There is very limited follow up of only 24 weeks, far too early to draw conclusions. But this report does highlight the impact of severe traumatic elbow arthritis in the young patient internationally and underscores the need to have reasonable options to restore function which in some cultures has grave implication referable to one's livelihood. In addition to cost, the practical advantage of this procedure is the availability of the interposition tissue in the surgical field. This is important as it can demonstrate the potential for alternate approaches in locales with more-limited resources.

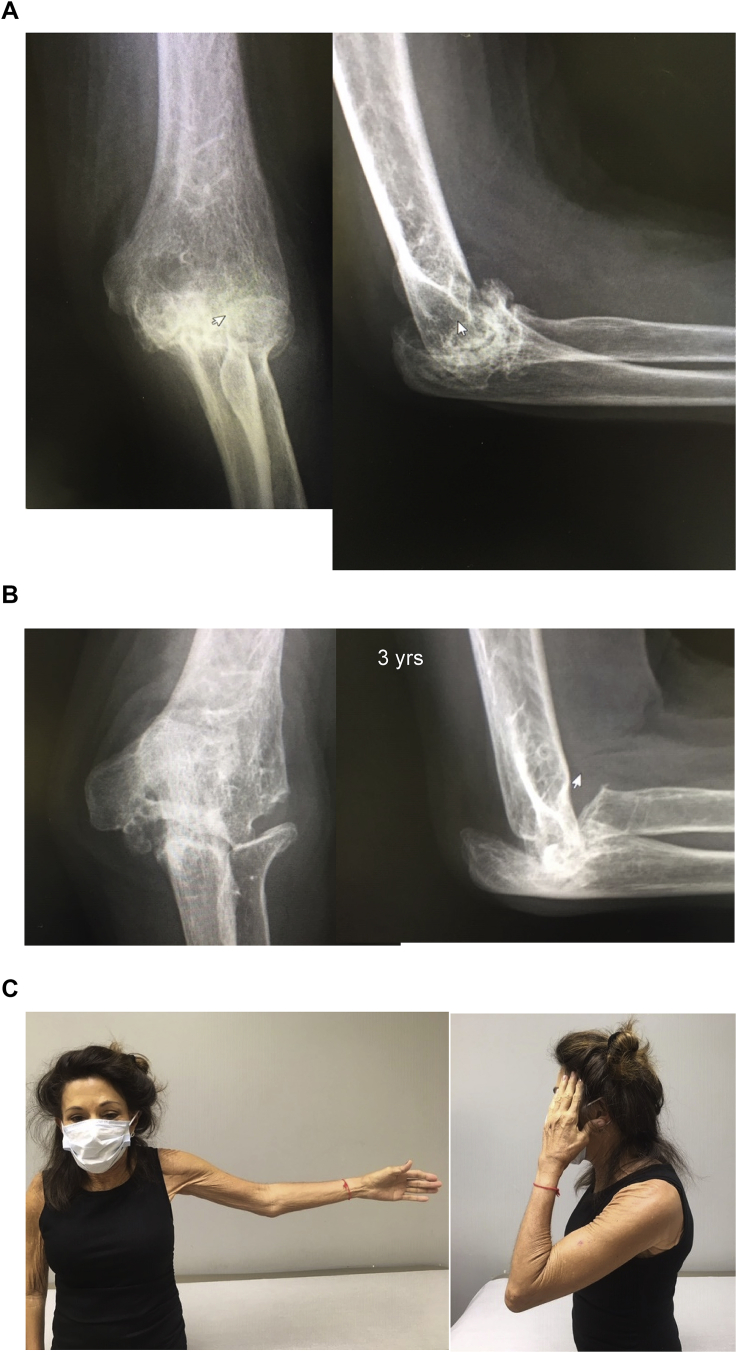

The Mayo experience was reviewed by Larson et al.3 and reported in 2008. A total of 69 patients with an average age of 39 years were treated with interposition using Achilles allograft from 1996 to 2003. Of those, 45 patients met inclusion criteria and 38 patients were followed for a mean of 6.0 years. Of note, there were 11 patients that were also treated simultaneously for varus or valgus instability of the elbow and underwent ligamentous reconstruction of one or both ligaments, which did result in some decreased post-operative motion. In spite of this, there was a mean flexion-extension arc improvement from 51° to 97° (p < 0.001). The mean Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) improved from 41 to 65 points (p < 0.0001). Thirteen patients had a good or excellent result, fourteen had a fair result, and eleven had a poor result; the remaining seven (of the original 45) had a revision. 31 patients gave subjective feedback of somewhat better or much better based on the MEPS. Of interest, 88% said they were glad they had the surgery (Fig. 8). A subsequent study identified nine patients who underwent revision to another interposition from 1996 to 2008.16 These were done at an average of 5.6 years after the initial procedure at a mean age of 47 years. With surveillance averaging of 4.7 years, the mean MEPS improved from 49 to 73 (p = 0.04). Five of the nine patients had subjective improvement on the MEPs and four patients were able to resume manual labor.

Fig. 8.

The radial nerve is at risk if the proximal humeral pin is more proximal than 1 epicondylar width (A). Tissue protecting trocars are also used in the placement of the humeral pins (B).

Alternative methods employing arthroscopic assistance with the preparation of the joint and placement of the graft have boasted the potential for decreased soft tissue disruption and improved stability as a result. Chauhan et al.17 performed a retrospective review of 4 patients with an average age of 57 with an average follow up of 3.6 years. The youngest patient was converted to a total elbow after 2.5 years, the other patients each had improvement in pain and gains of at least 30° of flexion arc with no instability at a mean of 4 years.

Regardless of the technique, it is important to note that these procedures may ultimately fail, and a salvage elbow replacement will be indicated. Blaine5 documented 11 of 13 (85%) satisfactory outcomes at a mean of 9 years after total elbow salvage for a failed interposition arthroplasty at the Mayo Clinic.

13. Conclusion

Severe arthritis in the young patient is a significant problem throughout the world and total elbow arthroplasty or fusion are unlikely to be the procedures that will provide patients the durability or function to meet the demands of this population. Ideally, in this population a treatment should provide good functional outcomes with good pain relief, without burning bridges for future intervention. Conceptually, while these outcomes are not impressive on an individual, objective level when viewed under the lens as a salvage procedure in young patients, they can be revised with reasonable outcomes to another interposition or even a TEA, this presents itself as a viable option for treatment. Additionally, with almost 90% of patients in the original Mayo series stating that they would undergo the procedure based on their outcome prompts the continued use of this procedure.

References

- 1.O'Neill O.R., Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.N. Compensatory motion in the upper extremity after elbow arthrodesis. Clin Orthop. 1992;281:89–96. PMID:1499233, 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morrey B.F. Interposition arthroplasty. Chap 114. In: Morrey B., Sanchez Sotelo J., Morrey M., editors. The Elbow and It's Disorders. fifth ed.. Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson A.N., Morrey B.F. Interposition arthroplasty with an Achilles tendon allograft as a salvage procedure for the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;(12):2714–2723. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00768. Dec;90. PMID: 19047718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng S.L., Morrey B.F. Treatment of the mobile, painful arthritic elbow by distraction interposition arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(2):233–238. Mar. PMID:10755432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaine T.A., Adams R., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty after interposition arthroplasty for elbow arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):286–292. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.03031pp. Feb. PMID:15687149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeon I.H., Morrey B.F., Anakwenze O.A. Incidence and implications of early postoperative wound complications after total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):857–865. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrey B.F. Morrey BF Editor. The Elbow. Third Edition. Wolters Kluwer; Philadelphia: 2015. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow; pp. 405–415. (Master techniques in orthopaedic surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araghi A., Celli A., Adams R., Morrey B. The outcome of examination (manipulation) under anesthesia on the stiff elbow after surgical contracture release. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.07.060. Mar. Epub 2009 Oct 17. PMID:19837613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative treatment with distraction interposition arthroplasty. J Bone and Jont Surg. 1990;72:601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanineni S., Ankem H., Patten D. Anatomic relationship of the radial nerve to the elbow joint. Clinical implication to safe pin placement. Clin Anat. 2009;22:684–688. doi: 10.1002/ca.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ljung P., Jonsson K., Larsson K. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow with rheumatoid arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:81. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed P., Debbarma I., Ameer F. Management of elbow arthritis by interposition arthroplasty with abdominal dermal graft. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;(Suppl 4):S610–S620. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2019.08.019. Jul;11. Epub 2019 Sep 2. PMID: 32774037; PMCID: PMC7394806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erşen A., Demirhan M., Atalar A.C., Salduz A., Tunalı O. Stiff elbow: distraction interposition arthroplasty with an Achilles tendon allograft: long-term radiological and functional results. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turcica. 2014;48(5):558–562. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.14.0131. PMID: 25429583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laubscher M., Vochteloo A.J., Smit A.A., Vrettos B.C., Roche S.J. A retrospective review of a series of interposition arthroplasties of the elbow. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6(2):129–133. doi: 10.1177/1758573214525126. Apr. Epub 2014 Apr 4. PMID: 27582927; PMCID: PMC4935068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iyidobi E.C., Nwadinigwe C.U., Ekwunife R.T. Early outcome after the use of the triceps fascia flap in interposition elbow arthroplasty: a novel method in the treatment of post-traumatic elbow stiffness. SICOT J. 2020;6:8. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2020006. Epub 2020 May 5. PMID: 32369013; PMCID: PMC7199511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larson A.N., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Revision interposition arthroplasty of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(9):1273–1277. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24039. Sep. PMID: 20798447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chauhan A., Palmer B.A., Baratz M.E. Arthroscopically assisted elbow interposition arthroplasty without hinged external fixation: surgical technique and patient outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(6):947–954. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.02.003. Jun. Epub 2015 Apr 7. PMID: 25861851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]