Key Points

Question

Are there symptom burden differences between Black and White women with early-stage breast cancer before starting chemotherapy?

Findings

In this cross-sectional observatonal study of 1338 patients from 1 cancer center, Black women reported a higher burden for symptoms typically associated with chemotherapy and lower distress than White women before chemotherapy intiation. Black patients’ baseline characteristics were associated with a significantly higher symptom burden, but this symptom burden was offset by relatively greater, unexplained reporting of physical, distress, and despair symptoms by White patients.

Meaning

Capturing treatment-related toxic effects by considering pretreatment symptoms may result in better-informed treatment decisions for patients.

Abstract

Importance

Race disparities persist in breast cancer mortality rates. One factor associated with these disparities may be differences in symptom burden, which may reduce chemotherapy tolerance and increase early treatment discontinuation.

Objectives

To compare symptom burden by race among women with early-stage breast cancer before starting chemotherapy and quantify symptom differences explained by baseline characteristics.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional analysis of symptom burden differences by race among Black and White women with a diagnosis of stage I to III, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer who had a symptom report collected before chemotherapy initiation in a large cancer center in the southern region of the US from January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2015. Analyses were conducted from November 1, 2019, to March 31, 2021. Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition was used, adjusting for baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Four symptom composite scores with a mean (SD) of 50 (10) were reported before starting chemotherapy (baseline) and were derived from symptom items: general physical symptoms (11 items), treatment adverse effects (8 items), acute distress (4 items), and despair (7 items). Patients rated the severity of each symptom they experienced in the past week on a scale of 0 to 10 (where 0 indicates not a problem and 10 indicates as bad as possible).

Results

A total of 1338 women (mean [SD] age, 54.6 [11.6] years; 420 Black women [31.4%] and 918 White women [68.6%]) were included in the study. Before starting chemotherapy, Black women reported a statistically significantly higher (ie, worse) symptom composite score than White women for adverse effects (44.5 vs 43.8) but a lower acute distress score (48.5 vs 51.0). Decomposition analyses showed that Black patients’ characteristics were associated with higher symptom burden across all 4 scores. However, these differences were offset by relatively greater, statistically significant, unexplained physical, distress, and despair symptom reporting by White patients.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this study, before starting chemotherapy, Black patients with early-stage breast cancer reported significantly higher burden for symptoms that may be exacerbated with chemotherapy and lower distress symptoms compared with White patients. Future studies should explore how symptoms change before and after treatment and differ by racial/ethnic groups and how they are associated with treatment adherence and mortality disparities.

This cohort study compares symptom burden among Black and White women with early-stage breast cancer before starting chemotherapy and assesses symptom differences associated with baseline characteristics.

Introduction

Although the breast cancer mortality rate has decreased, large racial/ethnic disparities persist.1,2 From 2012 to 2016, the breast cancer mortality rate among Black women was 41% higher than among White women.3 Although differences in treatment, health care access, and comorbidities explain some of the differences in mortality,4,5,6,7 they do not fully explain this disparity. Another important factor may be symptom burden. Severe or uncontrolled physical symptoms and mental health issues may decrease tolerance for the full chemotherapy course and are associated with early treatment discontinuation, which may increase breast cancer mortality.8,9,10

Chemotherapy is a critical treatment component for early-stage breast cancer. Compared with White women, Black women are more likely to delay initiation of chemotherapy or discontinue chemotherapy early.8,11,12,13,14 Several studies compared symptoms during or after chemotherapy by race/ethnicity and found mixed results.12,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Symptom assessment timing varied in these studies (eg, during treatment vs later in survivorship), which may explain the inconsistent findings. To our knowledge, no studies have compared differences in patient-reported symptoms before starting chemotherapy.

Several studies found that symptom severity differences between Black and White patients were attenuated but remained statistically significant after adjusting for patient characteristics (eg, sociodemographic characteristics, cancer stage, treatment received, and comorbidities).17,37 However, it is unclear whether symptom differences were associated with the treatment itself or with preexisting symptom burden not associated with the treatment.38,39 By comparing symptoms before treatment initiation, we can establish baseline treatment-related symptom differences between Black and White patients, which is an important step in determining symptom changes associated with treatment.

This study compared patient-reported symptoms before initiating chemotherapy among Black and White women with breast cancer. We used a Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition model to isolate the difference in symptom burden associated differences in baseline characteristics (ie, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics) from the unexplained difference in symptom reporting by Black and White women. We hypothesized that Black patients would report a higher baseline symptom burden than White patients and that most of the differences by race would be explained by associations with baseline characteristics.

Methods

Data and Analytical Sample

Our cohort consisted of patients treated at a large multidisciplinary cancer center, the West Cancer Center and Research Institute (WCCRI). At the WCCRI, patient-reported outcomes are routinely collected during visits using the Patient Care Monitor (PCM; ConcertAI). Responses are saved in patients’ electronic health records, and severe symptoms are highlighted for further evaluation during their visit. The WCCRI serves 60% of all oncology patients in the tristate area of west Tennessee, north Mississippi, and east Arkansas. Although the disparity in breast cancer mortality rates between Black and White patients improved in this region during the last 20 years, the mortality rate remains 1.7 times higher for Black women.5,40 The University of Tennessee Health Science Center institutional review board approved the study protocol and waived the requirement for written informed consent for participants in this data-only study. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

We used electronic health record data to identify patients’ diagnosis date, diagnosis stage, and demographic information. We merged electronic health record and PCM data with data from the Tennessee cancer registry to retrieve patients’ cancer history and cancer treatments received outside the WCCRI system. Where available, we obtained enrollment and claim information from Medicare and Tennessee’s Medicaid programs, to identify additional health care services used and chronic conditions.

We included patients who received a diagnosis during the period from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2015, of a first primary and stage I to III hormone receptor–positive breast cancer at the WCCRI (n = 5807), and we restricted the sample to those who initiated chemotherapy within 180 days of diagnosis (n = 1865). We then identified patients with a PCM report up to 45 days before chemotherapy initiation (n = 1526) and selected the report closest to the initiation date. We further restricted our sample to those who identified as White or Black (n = 1477), given a limited sample of other races/ethnicities, and those with a nonmissing residence zip code (n = 1338) (eFigure in the Supplement).

Comorbidity and surgery are important confounders for symptoms. Therefore, we tested the sensitivity of our findings using the following 2 subset samples: (1) Medicare beneficiaries with continuous fee-for-service coverage and complete claims for comorbidity evaluation in the year before their diagnosis (n = 147) and (2) patients with surgery identified prior to chemotherapy and a PCM report collected between surgery and chemotherapy initiation (n = 658).

Patient-Reported Symptoms

Our primary outcomes are 4 validated PCM scores derived from symptom items: general physical symptoms (11 items), treatment adverse effects (8 items), acute distress (4 items), and despair (7 items) (eTable 1 in the Supplement).41 Patients rated the severity of each symptom they experienced in the past week on a scale of 0 to 10 (where 0 indicates not a problem and 10 indicates as bad as possible). Given low symptom prevalence, we calculated the percentage of patients reporting any severity (0 vs 1-10) for each symptom. Each PCM score was calculated by summing raw item scores and then transformed into a normalized T score with a mean (SD) of 50 (10). Although common physical symptoms are captured in both general physical symptoms and treatment adverse effects scores, the items included in the treatment adverse effects score capture symptoms that may be exacerbated by chemotherapy. Because we included symptoms reported before starting chemotherapy, they should not be interpreted as symptoms caused by chemotherapy. General physical symptoms and treatment adverse effects scores together capture patients’ full profile of physical symptoms.

Covariates

Patient baseline characteristics included sociodemographic (eg, race, age, neighborhood-level income, educational level, and state of residence) and clinical factors (eg, cancer stage at diagnosis, time between cancer diagnosis and chemotherapy initiation, and time between PCM survey and chemotherapy initiation). Time between cancer diagnosis and chemotherapy was included given evidence that Black women delay initiation of cancer treatment, which may affect outcomes.11,42,43 We controlled for the lag between PCM date and chemotherapy initiation because of its considerable variation. Data on neighborhood-level household median income and percentage of adults with a high school degree from the 2011-2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates file44 were linked using patients’ residence zip codes or county codes where zip code–level data were not available.

For subsample analyses of Medicare beneficiaries, we obtained comorbidity data from the Chronic Conditions Segment of Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. Twelve common comorbidities were selected according to the National Cancer Institute Comorbidity Index.45 Subgroup analyses among patients with prechemotherapy surgery also controlled for time between surgery and the PCM survey.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted from November 1, 2019, to March 31, 2021. We used the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition model to quantify net differences in reported symptoms explained by differences in observable covariates between 2 groups and unexplained differences in symptoms.46,47,48,49 Specifically, we used a 2-fold–type decomposition with White patients as the reference group. Net differences refer to differences in raw symptom scores between White and Black patients. The explained difference was calculated as the sum of the difference in White and Black patients for each observed characteristic multiplied by the corresponding coefficient from the ordinary linear square model of White patients. A negative explained difference in our outcome variables would mean that, if Black patients had shared the same baseline characteristics as White patients, their symptom burden would be lower (ie, negative). The unexplained difference quantifies the change in Black patients’ symptom scores when applying White patients’ coefficients to Black patients. In our context, we interpreted unexplained differences as differences in reporting patterns between Black and White women not accounted for by covariates in our model.

To explore the extent to which the unexplained differences in symptom scores between Black and White patients were associated with differences in baseline comorbidities or receipt of surgery, we estimated Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition among a subset of Medicare patients with or without comorbidity indicators and a subset of surgery recipients with or without controlling for time from surgery. In the baseline characteristics comparison by race, the t test was used for mean comparisons, the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for median comparisons, and the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test were used for categorical measures. All P values were from 2-sided tests, and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. We used SAS software (2002-2012; SAS Institute Inc) for sample creation and Stata (2013; Stata Statistical Software: Release 13; StataCorp LP) for data analysis.

Results

Among the 1338 women in the study, the mean (SD) age was 54.6 (11.6) years, 918 (68.6%) were White women, and 420 (31.4%) were Black women. Compared with White patients, Black patients were younger (mean [SD], 52.3 [10.9] years vs 55.7 [11.8] years; P < .001) and more likely to live in neighborhoods with lower incomes (mean [SD], $42 167 [$18 828] vs $58 091 [$24 704]; P < .001) and fewer adults with a high school degree (mean [SD], 81.3% [8.6%] vs 86.2% [9.1%]; P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | P valuea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N = 1338) | Black (n = 420) | White (n = 918) | ||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.6 (11.6) | 52.3 (10.9) | 55.7 (11.8) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 54.0 (47.0-62.0) | 53.0 (45.0-60.0) | 55.0 (47.0-64.0) | <.001 |

| Stage at diagnosis | ||||

| I | 402 (30.0) | 115 (27.4) | 287 (31.3) | .10 |

| II | 679 (50.7) | 211 (50.2) | 468 (51.0) | |

| III | 257 (19.2) | 94 (22.4) | 163 (17.8) | |

| Household income at the neighborhood level, $ | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 53 092 (24 173) | 42 167 (18 828) | 58 091 (24 704) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 50 701 (33 829-65 517) | 35 686 (29 193-51 656) | 52 180 (36 816-70 541) | <.001 |

| Adults with high school degree at the neighborhood level, % | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 84.7 (9.3) | 81.3 (8.6) | 86.2 (9.1) | <.001 |

| Median (IQR) | 86.0 (77.0-92.8) | 80.0 (75.6-88.4) | 87.4 (79.7-94.2) | <.001 |

| State of residence | ||||

| Arkansas | 58 (4.3) | 9 (2.1) | 49 (5.3) | .001 |

| Mississippi | 367 (27.4) | 87 (20.7) | 280 (30.5) | |

| Tennessee | 866 (64.7) | 319 (76.0) | 547 (59.6) | |

| Other | 47 (3.5) | 5 (1.2) | 42 (4.6) | |

| Time between survey and chemotherapy initiation, mean (SD), d | 5.9 (8.3) | 6.1 (9.0) | 5.8 (8.0) | .52 |

| Time between diagnosis and chemotherapy initiation, mean (SD), d | 60.6 (32.0) | 65.7 (35.1) | 58.2 (30.2) | <.001 |

| Any severity symptoms, mean (SD), No. | 11.8 (9.2) | 11.9 (9.3) | 11.8 (9.1) | .87 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

The t test was used for mean comparisons, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for median comparisons, and the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test were used for categorical measures.

General Physical Symptoms

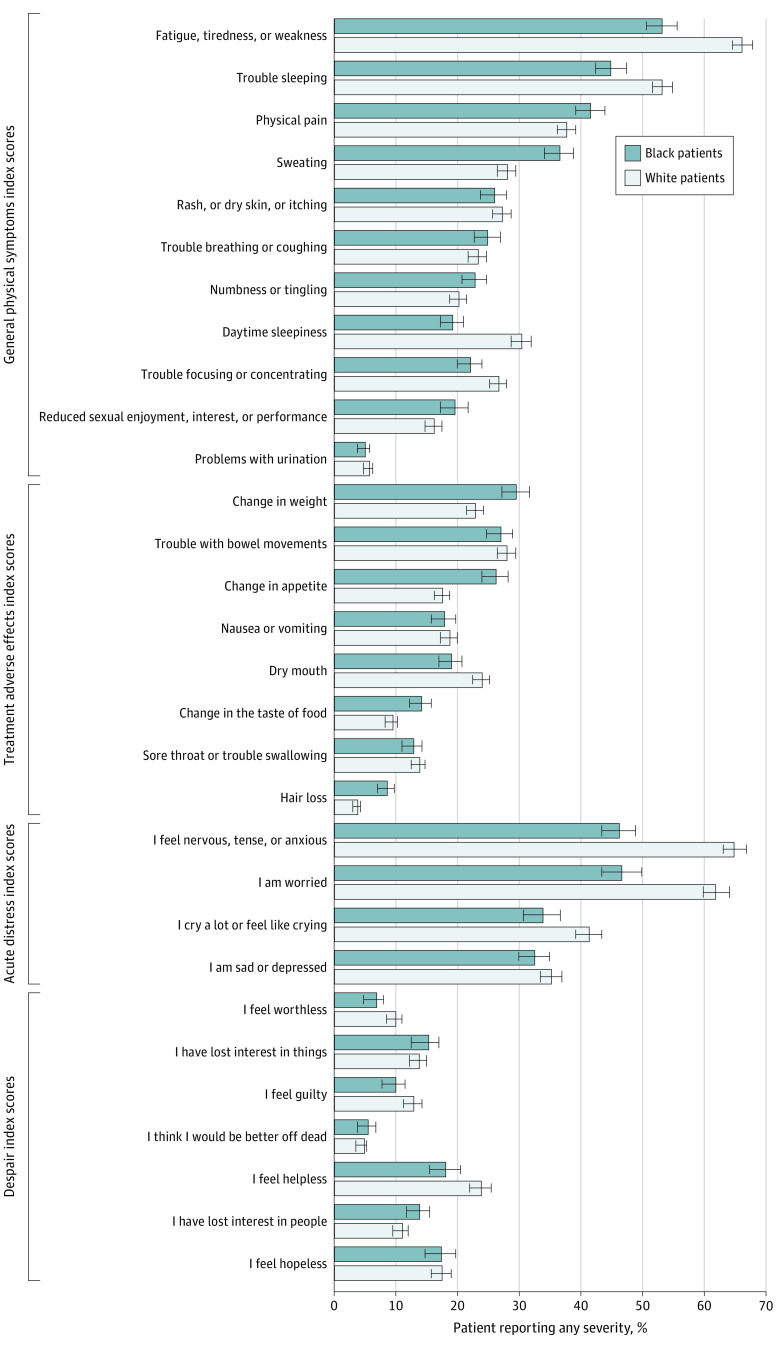

Of 11 symptoms in the general physical symptoms score, patients reported a mean (SD) of 3.2 (2.5) symptoms of any severity. White patients reported 3 symptoms more often than Black patients: fatigue, tiredness, or weakness (597 of 903 [66.1%] vs 219 of 412 [53.2%]; P < .001); daytime sleepiness (279 of 917 [30.4%] vs 80 of 416 [19.2%]; P < .001); and trouble sleeping (487 of 916 [53.2%] vs 187 of 417 [44.8%]; P = .005). Black patients reported sweating more frequently than White patients (153 of 418 [36.6%] vs 257 of 914 [28.1%]; P = .002) (Figure).

Figure. Unadjusted Differences in Reported Symptom Index Scores and Individual Symptoms by Race.

White and Black patients reported similar mean (SE) general physical symptom scores (44.7 [0.3] vs 44.5 [0.4]) (Table 2). When the net difference of 0.2 (P = .62) was decomposed, we found a negative explained difference. Thus, collectively, Black patient characteristics were associated with 1.1 points higher (ie, worse) general physical symptom scores (P < .001). Among the sociodemographic characteristics, neighborhood-level income was associated with the largest proportion of total explained difference (–0.52 of –1.1 [48.3%]) (Table 3). The negative explained difference was offset by the larger, positive unexplained difference; thus, for a given set of characteristics, White patients reported more severe physical symptoms (mean [SE], 1.3 [0.6] points; P = .02) (Table 2).

Table 2. Blinder-Oaxaca Decomposition of Racial Differences in Symptom Index Scores.

| Symptom index score | Patients, No. | Unadjusted mean (SE) composite scorea | Crude net difference (SE) in mean scoresa | Explained difference (SE)a | Unexplained difference (SE)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White patients | Black patients | |||||

| General physical symptoms | 1338 | 44.7 (0.3)b | 44.5 (0.4)b | 0.2 (0.5) | −1.1 (0.3)b | 1.3 (0.6)b |

| Treatment adverse effects | 1337 | 43.8 (0.2)b | 44.5 (0.3)b | −0.7 (0.3)b | −0.5 (0.2)b | −0.2 (0.3) |

| Acute distress | 1037 | 51.0 (0.4)b | 48.5 (0.6)b | 2.5 (0.8)b | −1.2 (0.4)b | 3.7 (0.8)b |

| Despair | 819 | 48.0 (0.3)b | 47.6 (0.5)b | 0.4 (0.6) | −1.1 (0.4)b | 1.4 (0.7)b |

Robust SEs in parentheses. Analysis controlled for age groups, household income at the neighborhood level and adults with high school degree at the neighborhood level, cancer stage, time between cancer diagnosis and chemotherapy, time between survey and chemotherapy, and state of residence.

P < .05.

Table 3. Explained Racial Differences in Symptom Index Scores by Each Baseline Characteristic.

| Characteristic | General physical symptoms | Treatment adverse effects | Acute distress | Despair | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained difference | % of Total explained difference | Explained difference | % of Total explained difference | Explained difference | % of Total explained difference | Explained difference | % of Total explained difference | |

| Total | −1.1a | 100.0 | −0.5a | 100.0 | −1.2a | 100.0 | −1.1a | 100.0 |

| Age | −0.24a | 22.5 | 0.01 | −3.0 | −0.30a | 25.8 | −0.17 | 16.4 |

| Disease stage | −0.02 | 2.0 | −0.02 | 4.9 | 0.02 | −1.9 | −0.05 | 5.1 |

| Household income at the neighborhood level | −0.52a | 48.3 | −0.20 | 43.1 | −0.81a | 68.9 | −0.98a | 93.2 |

| Adults with high school degree at the neighborhood level | −0.06 | 5.3 | −0.10 | 21.9 | 0.02 | −1.4 | 0.37 | −35.2 |

| State of residency | −0.06 | 6.0 | −0.05 | 9.9 | −0.32 | 27.1 | −0.13 | 12.4 |

| Time between survey and chemotherapy initiation | −0.02 | 14.3 | −0.02 | 19.3 | −0.02 | −20.0 | −0.02 | 6.2 |

| Time between diagnosis and chemotherapy initiation | −0.15a | 1.6 | −0.09 | 3.9 | 0.24 | 1.3 | −0.07 | 1.9 |

P < .05.

Treatment Adverse Effects

With the 8-item treatment adverse effects score, patients reported a mean (SD) of 1.4 (1.7) symptoms with any severity. Most of these symptoms were less common among White patients than Black patients, including weight change (206 of 899 [22.9%] vs 121 of 410 [29.5%]; P = .01), appetite change (161 of 916 [17.6%] vs 110 of 419 [26.3%]; P < .001), taste changes (86 of 914 [9.4%] vs 59 of 416 [14.2%]; P = .01), and hair loss (35 of 915 [3.8%] vs 36 of 418 [8.6%]; P < .001) (Figure).

White patients reported lower mean (SE) treatment adverse effects scores than Black patients (43.8 [0.2] vs 44.5 [0.3]; net difference, −0.7; P = .02). The explained difference was negative, implying that, if the average Black patient had the same characteristics as the average White patient, she would have reported a 0.5-point lower mean treatment adverse effects score (P = .005). Neighborhood-level income and educational level were associated with 43.1% (–0.20 of –0.5) and 21.9% (–0.10 of –0.5) of total explained differences, respectively (Table 3). The remaining unexplained difference was small and not statistically significant (−0.2; P = .54) (Table 2).

Acute Distress

Patients reported a mean (SD) of 1.7 (1.5) of 4 acute distress symptoms of any severity. White patients reported 3 distress symptoms more frequently than Black patients: feeling nervous, tense, or anxious (457 of 705 [64.8%] vs 153 of 331 [46.2%]; P < .001), feeling worried (350 of 566 [61.8%] vs 118 of 253 [46.6%]; P < .001), and crying a lot or feeling like crying (234 of 566 [41.3%] vs 86 of 254 [33.9%]; P = .04) (Figure).

White patients reported significantly higher mean (SE) acute distress scores than Black patients (51.0 [0.4] vs 48.5 [0.6]; net difference, 2.5; P = .001) (Table 2). The explained difference was negative, implying that Black patient characteristics were associated with, on average, a 1.2-point higher score (P = .005). Most of the explained difference was associated with neighborhood-level income (–0.81 of –1.2 [68.9%]) (Table 3). Higher scores assocated with Black patient characteristics were offset by a relatively larger and positive unexplained difference. For a given set of characteristics, White patients reported a mean (SE) 3.7 (0.8) points higher acute distress score than Black patients (P < .001) (Table 2).

Despair

Patients reported, on average, less than 1 of 7 despair symptoms (mean [SD] score, 0.7 [1.5]) (Figure). Comparisons of individual despair symptoms did not show a statistically significant difference between White and Black patients.

White patients reported a mean (SE) despair score of 48.0 (0.3), and Black patients reported a mean (SE) despair score of 47.6 (0.5) (net difference, 0.4; P = .55) (Table 2). The decomposition model found an explained difference of −1.1 points (P = .003), which was mostly associated with neighborhood-level income (–0.98 of –1.1 [93.2%] of total explained difference [Table 3]). Thus, if a Black patient had the same characteristics as a White patient, she would have reported a 1.1-point lower (or better) despair score. The explained difference was offset by a relatively larger positive mean (SE) unexplained difference of 1.4 (0.7) points (P = .049), resulting in a positive crude difference in mean despair score (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Among the 147 Medicare beneficiaries, we compared Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition models with or without adjusting for comorbidities. We found that, by adjusting for comorbidities, the explained differences were larger and statistically significant in all 4 scores. Nevertheless, it did not change the overall direction of results, which were comparable with the main cohort results (eTable 2 and eTable 4 in the Supplement). Analyses among 658 patients with a documented prechemotherapy surgery date with or without adjusting for time from surgery showed similar results and were consistent with main analyses as well. This finding suggests the minimal confoundedness of surgery on the baseline chemotherapy symptom report (eTable 3 and eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare patient-reported physical and psychological symptoms among Black and White women with breast cancer before starting chemotherapy. As expected, symptom burden was considerably lower than in previous studies in which assessments were taken after chemotherapy started.16,17,18,23,25 We found race-based differences in reported symptoms, with White women reporting more severe distress symptoms and Black women reporting more severe symptoms typically associated with chemotherapy treatment.

For all composite scores, decomposition of differences between Black and White patients consistently showed a negative and statistically significant explained difference. Thus, if Black patients had the same characteristics as White patients, such as living in neighborhoods with higher incomes, they would have reported a lower symptom burden. Neighborhood-level income had the most explanatory power (43.1%-93.2% of total explained difference) among the included baseline characteristics. Moreover, the positive and statistically significant unexplained difference found in physical, distress, and despair symptom scores suggests that White women reported significantly more severe symptoms than Black women with comparable characteristics. In other words, given Black patients’ characteristics, if they reported symptoms as if they were the average White patient, Black patients’ symptom burden scores would be higher (ie, worse). This pattern provides evidence of race-based differences in symptom reporting and illustrates the insights gained from exploring the masked underlying variations in symptom reporting by race.

It is concerning that symptoms that may be exacerbated with chemotherapy were more severe at baseline among Black patients.8,9,10 Among specific symptoms, Black women were more likely to report appetite changes, weight changes, changes in taste, and hair loss before starting chemotherapy. The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition found that a large proportion (71%, −0.5 explained of −0.7 net difference) of the difference between Black and White patients in baseline adverse effects was associated with the difference in observed patient characteristics. Unlike the other composite scores, we did not find evidence of unexplained higher reporting of treatment adverse effects among White women. Having higher baseline symptoms that may be exacerbated with chemotherapy may be associated with even higher symptom burden during treatment, potentially contributing to the greater treatment discontinuation rates observed among Black women.50 Without accounting for baseline symptoms, treating oncologists may incorrectly assume that these symptoms are associated with chemotherapy itself rather than patients’ characteristics. This assumption may result in treatment course changes due to misattributed chemotherapy-related toxic effects. Therefore, oncologists should consider making treatment decisions based on changes in treatment-related symptoms reported before and after chemotherapy initiation.

Our finding that White women reported greater distress than Black women is consistent with previous epidemiologic surveys that Black women report lower levels of distress compared with White women during cancer treatment and in later survivorship.51,52,53 Prior research identified several potential protective factors that may be associated with this difference (eg, resilience, social support, and religious beliefs).51,54 Moreover, Black women may use different coping strategies (eg, suppressing emotions and wishful thinking) that may be associated with lower reporting of distress, whereas White women may be more comfortable expressing emotions.55 Accordingly, our decomposition results suggest that, if Black women had the same characteristics as White women, they would have reported even lower (ie, better) distress composite scores, widening the gap between the 2 groups. More research is needed to investigate the causes of this racial/ethnic difference in distress.

Across all 4 composite scores, neighborhood-level income was most associated with the observed differences in symptoms by race, ranging from 43.1% of the difference in treatment adverse effects to 93.2% for distress. Thus, oncologists, hospitals, and related public health authorities should consider the social context when evaluating the source of racial differences in symptoms and subsequent cancer outcomes. Targeted social support programs for patients living in underresourced communities may be beneficial.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. Unexplained differences in reported symptoms may have been associated with both differences in actual prevalence of symptoms and systemic differences in reporting between the 2 groups. For example, although it is possible that Black women truly experienced less fatigue and had lower distress and despair than White patients, these differences may also be partially explained by interpretation of the questions and reporting preferences.56 It is also possible that Black patients underreported symptoms owing to fears that racial bias may interfere with their physician’s decision about their treatment.57 More research is needed to fully understand the reporting process, including how patient perceptions and patient-clinician interactions are associated with treatment strategies and decision-making. Measurement equivalence for different racial/ethnic groups is a concern for patient-reported outcome assessment,58,59,60 and we cannot separate out such an effect given the study data. In addition, interpretation of the explained and unexplained differences depends on the availability of observable characteristics. Although our sensitivity analyses addressed the potential confoundedness of comorbidities and symptoms from surgery, there may be other potential confounders, such as surgery types, other treatments, lifestyle factors, and social support, that we were not able to measure and include in our models.61 Furthermore, we studied women with hormone receptor–positive early-stage breast cancer who were treated in a single cancer center in the southern US. Therefore, our results may not be generalizable to other conditions or settings.

Conclusions

In this large, single-center cross-sectional study of 1338 women with a diagnosis of early-stage breast cancer between 2007 and 2015, we found 2 key differences in symptoms before chemotherapy among Black and White women. First, if Black patients had the same baseline characteristics as White patients, they would have had a lower symptom burden across all 4 symptom scores. However, this symptom burden was not always observable when comparing crude differences in average symptoms because it was offset by larger, statistically significant, unexplained reporting of more severe symptoms by White patients. Second, in contrast to other symptom measures, the mean treatment adverse effects score before starting chemotherapy was higher among Black patients. Higher baseline symptoms may be associated with even higher reported treatment adverse effects during chemotherapy. Consequently, capturing treatment-related toxic effects by comparing changes from pretreatment symptoms may result in better-informed treatment decisions for patients. Future studies should examine how prechemotherapy symptom differences by race/ethnicity may be associated with differences in symptom changes during chemotherapy and their subsequent association with treatment adherence and cancer survival.

eFigure. Sample Selection Flow Chart

eTable 1. List of Individual Symptoms Used for Four Compound Scores

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics of Medicare Subsample

eTable 3. Patient Characteristics of Patients Who Received Surgery Before Chemotherapy and Had a PCM Report Between Surgery and Chemotherapy Initiation

eTable 4. Oaxaca Decomposition of Race Differences in Symptom Index Scores of Medicare Subsample

eTable 5. Oaxaca Decomposition of Race Differences in Symptom Index Scores of Patients Who Received Surgery Before Chemotherapy and Had a PCM Report Between Surgery and Chemotherapy Initiation

References

- 1.McCarthy AM, Yang J, Armstrong K. Increasing disparities in breast cancer mortality from 1979 to 2010 for US black women aged 20 to 49 years. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(suppl 3):S446-S448. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller JW, Smith JL, Ryerson AB, Tucker TC, Allemani C. Disparities in breast cancer survival in the United States (2001-2009): findings from the CONCORD-2 study. Cancer. 2017;123(suppl 24):5100-5118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Cancer statistics for African Americans, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(3):211-233. doi: 10.3322/caac.21555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cook BL, McGuire TG, Zaslavsky AM. Measuring racial/ethnic disparities in health care: methods and practical issues. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3, pt 2):1232-1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01387.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt BR, Whitman S, Hurlbert MS. Increasing Black:White disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;38(2):118-123. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2013.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menashe I, Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Rosenberg PS. Underlying causes of the Black-White racial disparity in breast cancer mortality: a population-based analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(14):993-1000. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(20):2254-2261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knisely AT, Michaels AD, Mehaffey JH, et al. Race is associated with completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Surgery. 2018;164(2):195-200. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neugut AI, Hillyer GC, Kushi LH, et al. A prospective cohort study of early discontinuation of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer: the Breast Cancer Quality of Care Study (BQUAL). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158(1):127-138. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3855-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonadonna G, Valagussa P. Dose-response effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(1):10-15. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198101013040103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green AK, Aviki EM, Matsoukas K, Patil S, Korenstein D, Blinder V. Racial disparities in chemotherapy administration for early-stage breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;172(2):247-263. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4909-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCall MK, Connolly M, Nugent B, Conley YP, Bender CM, Rosenzweig MQ. Symptom experience, management, and outcomes according to race and social determinants including genomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics (SEMOARS + GEM): an explanatory model for breast cancer treatment disparity. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35(3):428-440. doi: 10.1007/s13187-019-01571-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griggs JJ, Sorbero MES, Stark AT, Heininger SE, Dick AW. Racial disparity in the dose and dose intensity of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2003;81(1):21-31. doi: 10.1023/A:1025481505537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhargava A, Du XL. Racial and socioeconomic disparities in adjuvant chemotherapy for older women with lymph node–positive, operable breast cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(13):2999-3008. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, et al. Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106(1):85-95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budhrani PH, Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Tofthagen C, Jim H. Minority breast cancer survivors: the association between race/ethnicity, objective sleep disturbances, and physical and psychological symptoms. Nurs Res Pract. 2014;2014:858403. doi: 10.1155/2014/858403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Check DK, Chawla N, Kwan ML, et al. Understanding racial/ethnic differences in breast cancer–related physical well-being: the role of patient-provider interactions. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;170(3):593-603. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4776-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(2):250-256. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.250-256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallicchio L, Calhoun C, Helzlsouer KJ. Association between race and physical functioning limitations among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1081-1088. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2066-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, Holland J. Prevalence of physical problems detected by the distress thermometer and problem list in patients with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2018;27(5):1394-1403. doi: 10.1002/pon.4631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McFarland DC, Shaffer KM, Tiersten A, Holland J. Physical symptom burden and its association with distress, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(5):464-471. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrow PK, Broxson AC, Munsell MF, et al. Effect of age and race on quality of life in young breast cancer survivors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2014;14(2):e21-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paskett ED, Alfano CM, Davidson MA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life: racial differences and comparisons with noncancer controls. Cancer. 2008;113(11):3222-3230. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perry LM, Hoerger M, Sartor O, Robinson WR. Distress among African American and White adults with cancer in Louisiana. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2020;38(1):63-72. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2019.1634176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinheiro LC, Samuel CA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Wheeler SB, Olshan AF, Reeve BB. Understanding racial differences in health-related quality of life in a population-based cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;159(3):535-543. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3965-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ploos van Amstel FK, van den Berg SW, van Laarhoven HW, Gielissen MF, Prins JB, Ottevanger PB. Distress screening remains important during follow-up after primary breast cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(8):2107-2115. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1764-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porter LS, Clayton MF, Belyea M, Mishel M, Gil KM, Germino BB. Predicting negative mood state and personal growth in African American and White long-term breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(3):195-204. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3103_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuel CA, Pinheiro LC, Reeder-Hayes KE, et al. To be young, Black, and living with breast cancer: a systematic review of health-related quality of life in young Black breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;160(1):1-15. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3963-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Samuel CA, Schaal J, Robertson L, et al. Racial differences in symptom management experiences during breast cancer treatment. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(5):1425-1435. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3965-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tejeda S, Stolley MR, Vijayasiri G, et al. Negative psychological consequences of breast cancer among recently diagnosed ethnically diverse women. Psychooncology. 2017;26(12):2245-2252. doi: 10.1002/pon.4456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Von Ah DM, Russell KM, Carpenter J, et al. Health-related quality of life of African American breast cancer survivors compared with healthy African American women. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(5):337-346. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182393de3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yee MK, Sereika SM, Bender CM, Brufsky AM, Connolly MC, Rosenzweig MQ. Symptom incidence, distress, cancer-related distress, and adherence to chemotherapy among African American women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2017;123(11):2061-2069. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoon J, Malin JL, Tao ML, et al. Symptoms after breast cancer treatment: are they influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(2):153-165. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9599-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoon J, Malin JL, Tisnado DM, et al. Symptom management after breast cancer treatment: is it influenced by patient characteristics? Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;108(1):69-77. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9580-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gill KM, Mishel M, Belyea M, et al. Triggers of uncertainty about recurrence and long-term treatment side effects in older African American and Caucasian breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(3):633-639. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.633-639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haq MU, Vontela N, Naini P, Snider JN, Walker MS, Schwartzberg LS. Acute toxicity in African American and Caucasian patients with adjuvant/neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(15_suppl):1059. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.1059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jemal A, Robbins AS, Lin CC, et al. Factors that contributed to Black-White disparities in survival among nonelderly women with breast cancer between 2004 and 2013. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(1):14-24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hahn EA, Segawa E, Kaiser K, Cella D, Smith BD. Validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (FACT-B) quality of life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(15_suppl):e17753. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.33.15_suppl.e17753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitchell SA, Lang K, Nichols C, et al. Validation of the NCI patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) in women receiving treatment for metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15_suppl):9144. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.30.15_suppl.9144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hunt BR, Hurlbert MS. Black:White disparities in breast cancer mortality in the 50 largest cities in the United States, 2005-2014. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;45:169-173. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abernethy AP, Zafar SY, Uronis H, et al. Validation of the Patient Care Monitor (Version 2.0): a review of system assessment instrument for cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(4):545-558. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nurgalieva ZZ, Franzini L, Morgan RO, Vernon SW, Liu CC, Du XL. Impact of timing of adjuvant chemotherapy initiation and completion after surgery on racial disparities in survival among women with breast cancer. Med Oncol. 2013;30(1):419. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0419-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fedewa SA, Ward EM, Stewart AK, Edge SB. Delays in adjuvant chemotherapy treatment among patients with breast cancer are more likely in African American and Hispanic populations: a national cohort study 2004-2006. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4135-4141. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.United States Census Bureau. American Community Survey, 2015 American Community Survey 5-year estimates, table S1901. Accessed September 23, 2020. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/

- 45.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, Warren JL. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(12):1258-1267. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00256-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wheeler SB, Spencer J, Pinheiro LC, et al. Endocrine therapy nonadherence and discontinuation in Black and White women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(5):498-508. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oaxaca R. Male-female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int Econo Rev. 1973;14(3):693-709. doi: 10.2307/2525981 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blinder AS. Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J Hum Resources. 1973;8(4):436-455. doi: 10.2307/144855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jann B. The Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for linear regression models. Stata J. 2008;8(4):453-479. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0800800401 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Richardson LC, Wang W, Hartzema AG, Wagner S. The role of health-related quality of life in early discontinuation of chemotherapy for breast cancer. Breast J. 2007;13(6):581-587. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00512.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fayanju OM, Ren Y, Stashko I, et al. Patient-reported causes of distress predict disparities in time to evaluation and time to treatment after breast cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2021;127(5):757-768. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bratter JL, Eschbach K. Race/ethnic differences in nonspecific psychological distress: evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. Soc Sci Q. 2005;86(3):620-644. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamlish T, Papautsky EL. Differences in emotional distress among Black and White breast cancer survivors during the Covid-19 pandemic: a national survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Published online February 23, 2021. doi: 10.1007/s40615-021-00990-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psychooncology. 2002;11(6):495-504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reynolds P, Hurley S, Torres M, Jackson J, Boyd P, Chen VW. Use of coping strategies and breast cancer survival: results from the Black/White Cancer Survival Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(10):940-949. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Im EO, Lim HJ, Clark M, Chee W. African American cancer patients’ pain experience. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(1):38-46. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305685.59507.9e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43-52. doi: 10.1370/afm.1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carle AC, Weech-Maldonado R, Ngo-Metzger Q, Hays RD. Evaluating measurement equivalence across race and ethnicity on the CAHPS Cultural Competence Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(9)(suppl 2):S32-S36. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182631189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim G, Wang SY, Sellbom M. Measurement equivalence of the subjective well-being scale among racially/ethnically diverse older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75(5):1010-1017. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lix LM, Acan Osman B, Adachi JD, et al. Measurement equivalence of the SF-36 in the Canadian Multicentre Osteoporosis Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weaver A, Himle JA, Taylor RJ, Matusko NN, Abelson JM. Urban vs rural residence and the prevalence of depression and mood disorder among African American women and non-Hispanic White women. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(6):576-583. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Sample Selection Flow Chart

eTable 1. List of Individual Symptoms Used for Four Compound Scores

eTable 2. Patient Characteristics of Medicare Subsample

eTable 3. Patient Characteristics of Patients Who Received Surgery Before Chemotherapy and Had a PCM Report Between Surgery and Chemotherapy Initiation

eTable 4. Oaxaca Decomposition of Race Differences in Symptom Index Scores of Medicare Subsample

eTable 5. Oaxaca Decomposition of Race Differences in Symptom Index Scores of Patients Who Received Surgery Before Chemotherapy and Had a PCM Report Between Surgery and Chemotherapy Initiation