Abstract

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is a leading cause of death in patients with type 1 diabetes. The key to treating IHD is to restore blood supply to the ischemic myocardium, which inevitably causes myocardial ischemia reperfusion (MI/R) injury. Although naringenin (Nar) prevents MI/R injury, the role of Nar in diabetic MI/R (D-MI/R) injury remains to be elucidated. The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and microRNA (miR)-126 have previously been shown to serve anti-MI/R injury roles. The present study aimed to investigate the protection of Nar against D-MI/R injury and the role of the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis. Diabetic rats were treated distilled water or Nar (25 or 50 mg/kg, orally) for 30 days and then exposed to MI/R. The present results revealed that Nar alleviated MI/R injury in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats, as shown below: the reduction myocardial enzymes levels was measured using spectrophotometry, the increase of cardiac viability was detected by MTT assay, the inhibition of myocardial oxidative stress was measured using spectrophotometry and the enhancement of cardiac function were recorded using a hemodynamic monitoring system. Furthermore, Nar upregulated the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in D-MI/R rats. These results indicated that Nar alleviated MI/R injury through upregulating the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in STZ-induced diabetic rats. The current findings revealed that Nar, as an effective agent against D-MI/R injury, may provide an effective approach in the management of diabetic IHD.

Keywords: ischemic heart disease, myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury, naringenin, PI3K/AKT signaling, microRNA-126

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) is a threat to human health (1,2), and the key to treating IHD is to restore blood supply to the ischemic myocardium as soon as possible (3). However, restoration of blood supply is inevitably accompanied by subsequent cardiac injury, which is widely recognized as myocardial ischemia reperfusion (MI/R) injury (1,4,5). Since IHD became the leading cause of death in patients with type 1 diabetes (6), the MI/R injury in diabetes has attracted widespread attention. Epidemiological data have demonstrated that the incidence rate of ischemic cardiomyopathy among patients with diabetes is ~4-fold higher than that among patients without diabetes (7). Patients with diabetes are more susceptible to MI/R injury (8,9), with worse clinical prognosis and higher fatality rate compared with patients without diabetes (10,11). Therefore, it is necessary to implement new strategies to prevent MI/R injury in patients with diabetes to improve the effectiveness diabetic IHD treatment.

Naringenin (Nar) is a naturally occurring flavanone, predominantly derived from citrus fruits. Nar plays a biological role in the human body (12), and is known to exert cardioprotective effects (13). Nar prevents doxorubicin-induced toxicity, including apoptosis and oxidative stress in cardiomyoblasts (14-17). In addition, Nar antagonizes hypercholesterolemia-induced cardiac oxidative stress and subsequent necroptosis in rats (18). Although a few studies have confirmed that Nar is able to attenuate MI/R injury (19,20), to the best of our knowledge, whether Nar counteracts MI/R injury in diabetes has not yet been clarified. It has been reported that Nar protects cardiomyocytes against hyperglycemia-induced injury (21). Therefore, in the present study, streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats were exposed to MI/R to construct a model of diabetic MI/R (D-MI/R) injury, and to explore whether Nar has a potential therapeutic function.

The PI3K/AKT signaling pathway plays a critical protective role in MI/R injury (22). In the myocardium, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway indirectly regulates the contraction of the cardiac muscle and the function of calcium channels (23). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is impaired during MI/R injury, and that MI/R injury can be ameliorated by activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (24-26). These previous studies provided evidence that activated PI3K/AKT signaling may improve MI/R injury. Therefore, the present study investigated whether the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is involved in the protective effect of Nar against MI/R injury in diabetes.

MicroRNA-126 (miR-126) is involved in the pathophysiological processes of various cardiovascular diseases, particularly MI/R injury (27-29). It has been demonstrated that miR-126 attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis induced by MI/R injury in rats (27,28). Notably, miR-126 may be a therapeutic agent for diabetes mellitus (30). Diabetes reduces miR-126 expression and angiogenesis in the myocardium compared with healthy rats, while enhancement of myocardial miR-126 level significantly improves myocardial angiogenesis in diabetic rats (31). Therefore, although an association between Nar and miR-126 has not been reported to date, the aforementioned studies led to a hypothesis that miR-126 may be involved in the protective effects of Nar against MI/R injury in diabetes.

The present study aimed to explore whether Nar antagonizes MI/R-injury in diabetic rats and whether miR-126-PI3K/AKT are involved in this protective effect. The results of the present study demonstrated that Nar significantly ameliorated MI/R injury and enhanced the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in rats with D-MI/R. The results suggest that Nar alleviated MI/R injury via enhancing the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in STZ-induced diabetic rats.

Materials and methods

Reagents

STZ, Nar, ketamine, xylazine and an MTT kit were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA. The BCA protein assay kit was obtained from Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) measurement kits were obtained from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute. The assay kits for glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px), superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and H2O2 measurement were purchased from Wuhan USCN Business Co., Ltd. Specific monoclonal antibodies against phosphorylated (p)-PI3K (cat. no. 4228), PI3K (cat. no. 4255), p-AKT (cat. no. 9271), AKT (cat. no. 9272) and GAPDH (cat. no. 2118), Anti-rabbit IgG-HRP-linked Antibody (cat. no. 7074) were supplied by Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.

Animals

A total of 50 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (age, 8-10 weeks; weight, 250±10 g) were supplied by Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center. Rats were raised in single cages (individually) in a specific-pathogen-free environment under a 12-h light/dark cycle (light exposure, 7:00 a.m.-7:00 p.m.), and maintained at a constant temperature (22±2˚C), ventilation and humidity (50%). Rats were provided with food and water ad libitum, and the bedding was changed 1-2 times a week to ensure a suitable environment for the rats.

Induction of diabetes

STZ was dissolved in 0.1 mol/l sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.3) and used immediately after preparation, which was performed in a cold (4-6˚C) and dark environment. After overnight (12-h) fasting, the rats were weighed. The STZ-treated groups received a single intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of STZ (55 mg/kg), while the other groups received an equivalent dose of PBS (i.p.). The rats were administered food 1 h after STZ injection. A total of 72 h after the STZ injection, Baseline body weight and blood glucose level were measured in all the rats. After STZ or PBS injection, blood glucose levels at day 3 and day 30 were determined measured using a glucometer (Roche Applied Science), and body weights were measured once a week. Only animals with fasting blood glucose levels >16.7 mmol/l at 3 days after STZ injection were considered diabetic and ~80 rats used for further experiments (32). Finally, six of the rats did not reach their target levels of blood glucose, which were supplemented with STZ (10-20 mg/kg) 3 days later. Failing that, diabetic induction was repeated from scratch once blood glucose levels had returned to normal.

Experimental protocol

After a week of adaptation to the experimental environment, then 3 days after the STZ or PBS injection, the rats were randomly divided into the following five groups (10 rats in each group) and were provided with the following treatments: i) Control-sham group (C-S), non-diabetic rats that received sham surgery; ii) diabetes-sham group (D-S), diabetic rats that received sham surgery; iii) D-MI/R group, diabetic rats that were orally treated with vehicle (distilled water, 1.5 ml) for 30 days, and then subjected to MI/R injury; iv) D-MI/R + low-dose Nar (LN) group, diabetic rats that were orally treated with Nar (25 mg/kg/day; diluted in distilled water) for 30 days and then subjected to I/R injury; and v) D-MI/R + high-dose Nar (HN) group, diabetic rats that were orally treated with Nar (50 mg/kg/day; diluted in sterile water) for 30 days and then subjected to I/R injury.

MI/R modeling

After the aforementioned 4 weeks of treatment with Nar or distilled water, the hearts of the rats were isolated and perfused according to a previously described protocol (33,34). Briefly, the each rat were heparinized (500 IU) to avoid blood clotting during surgery and then anesthetized with ketamine (60 mg/kg; i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg/kg; i.p.). Subsequently, the hearts were rapidly excised and immediately perfused on a Langendorff device (ADInstruments, Ltd.) with modified Krebs-Henseleit solution (pH 7.4; 37˚C) containing 118 mmol/l NaCl, 4.7 mmol/l KCl, 1.25 mmol/l CaCl2, 1.2 mmol/l MgSO4, 25 mmol/l NaHCO3, 1.2 mmol/l KH2PO4 and 11 mmol/l glucose, saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Upon stabilization, the hearts were subjected to 30-min regional ischemia by tightening a 5-0 silk suture around the left anterior descending coronary artery and reperfusion for 120 min. The sham groups underwent sham surgery (the left anterior descending coronary artery was not ligated) in which the heart was exteriorized without MI/R injury.

Evaluating myocardial systolic and diastolic functions

For measurement of interventricular pressure changes, a water-filled latex balloon was inserted into the left ventricle, and the signals were delivered to the associated transducer through a connecting pressure catheter. After reperfusion, the cardiac function index, including left ventricular systolic pressure (LVSP), left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) and left ventricular maximal systolic/diastolic velocity (±dP/dtmax, +dP/dtmax = the maximum rate of pressure rise in the left ventricle; -dP/dtmax = the maximum rate of pressure drop in the left ventricle), were recorded using a hemodynamic monitoring system (PowerLab-PL3508; ADInstruments, Ltd.).

Measurement of cardiac tissue viability, and CK and LDH levels

After reperfusion, the hearts were cut into 2-mm-thick sections and incubated with MTT (3 mM) at 37˚C for 30 min to form formazan (34). Based on previous study, cardiac tissue viability was measured by the level of formazan using a spectrophotometer at 550 nm (34). In addition, at 5 min after reperfusion, the coronary effluent was collected for the determination of cardiac CK-MB and LDH activities, which are two major indicators of MI/R injury, by spectrophotometry using the aforementioned commercial assay kits according to a previously described protocol (35). The activities of these two enzymes were expressed as U/l.

Mitochondrial oxidative stress quantification

After reperfusion, the myocardial tissue was homogenized (10% w/v) in 0.1 mol/l PBS and centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. Subsequently, the supernatant was collected, and the protein concentration was quantified using the aforementioned BCA protein assay. As previously described (36,37), the activities of GSH-Px and SOD, the levels of MDA and 8-OHdG, and H2O2 formation in the supernatant were determined by spectrophotometry using the aforementioned commercially available kits.

Western blot analysis

The protein levels of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-AKT and AKT were measured by western blotting. After reperfusion, myocardial tissue was homogenized in ice-cold homogenizing buffer [20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100 and 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride). After centrifugation at 12,000 x g for 30 min at 4˚C, the supernatant was collected and the protein concentration was analyzed using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Approximately 10 µg of protein for each sample were resolved by SDS-PAGE (8-12%) and transferred onto PVDF membranes by electroblotting. Non-specific protein binding was blocked with TBS-Tween-20 [TBS-T; 50 mmol/l Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mmol/l NaCl and 0.05% Tween-20] containing 5% non-fat milk for 2 h at room temperature, and the membranes were incubated overnight at 4˚C with the aforementioned primary antibodies (P-PI3K, PI3K, P-AKT, AKT, GAPDH; dilution, 1:1,000). After the membranes were washed three times with TBS-T buffer, the blots were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5,000) for 2 h at 4˚C. Subsequently, the membranes were washed with TBS-T buffer (five times for 5 min each) and electrogenerated chemiluminescence reaction solution (SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate-A38555; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added for 30 sec. The protein bands were visualized using a Tanon-5600 Imaging System (Tanon Science and Technology Co., Ltd.). The semi-quantitative analysis of each blot was performed using SigmaScan Pro 5.0 software (Systat Software, Inc) and expression values were normalized to that of GAPDH.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The myocardial miR-126 level was measured by RT-qPCR as previously described (28). Briefly, total RNA from the myocardial tissue of rats was isolated using the TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Next, miRNA-specific stem-loop primers were reverse transcribed to cDNA according to the instructions of the miRNA RT kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). RT reaction conditions were processed at 42˚C for 15 min, followed by 3 min at 95˚C. qPCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq™ according to the manufacturer's instructions (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The following PCR protocol was used: 95˚C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 ˚C for 15 sec and 60 ˚C for 1 min. The 2-ΔΔCq method (38) was used to calculate the relative expression levels of miR-126 and U6 was used as an internal reference. The sequences of the primers (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) used were as follows: miR-126 forward, 5'-ACTGTCACTCTCATCACAAGCGC-3' and reverse, 5'-ACGCTGGCTCAGGGATCAGAGA-3'; and U6 forward, 5'-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3' and reverse, 5'-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3'.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were repeated ≥3 times, and statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 20.0 software (IBM Corp.). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM, and differences between groups were assessed using one-way analysis of variance and Tukey's post hoc test. Repeated measurement data were analyzed using mixed ANOVA and a Tukey's post-hoc test for simple main effects. Two-tailed P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Nar does not affect blood glucose levels or body weight in STZ-induced diabetic rats

Blood sugar levels and weight were regularly measured in diabetic rats to determine whether Nar had an effect on these parameters. The blood glucose level of the diabetic groups was significantly higher than that of the control group 3 days after STZ injection (Fig. 1A). At day 30, the blood glucose levels in the four diabetic groups remained high, and there was no significant difference in blood glucose levels between STZ-treated rats and rats co-treated with STZ and Nar (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

Effect of Nar on body weight and blood glucose levels in rats. (A) Blood glucose levels at days 0, 3 and 30 were determined with a blood glucose meter. (B) Body weight in the different groups was measured once a week. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=8-10/group). ***P<0.001 compared with the control-sham group. Nar, naringenin; STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion.

Body weight was measured once a week after STZ or PBS injection

The body weight of STZ-induced diabetic rats was significantly reduced compared with that of the control group. In addition, there were no significant differences in body weight between STZ-treated rats and rats co-treated with STZ and Nar (Fig. 1B). These data indicate that STZ injection resulted in a diabetic status in rats, and that Nar did not affect the blood glucose level or body weight of diabetic rats.

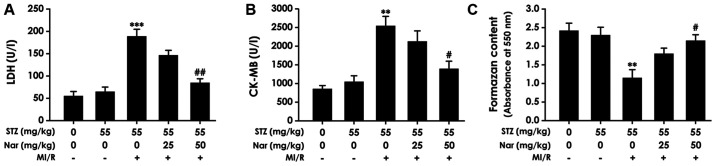

Nar decreases myocardial enzyme content and enhances cardiac tissue viability in D-MI/R rats

To determine if Nar alleviated MI/R injury in diabetic rats, the present study first explored whether Nar decreased myocardial enzyme levels and enhanced cardiac tissue viability by observing the effects of Nar on the levels of LDH and CK-MB in the coronary effluent, and the viability of heart tissues in D-MI/R rats. The results showed that HN significantly downregulated the levels of LDH and CK-MB (Fig. 2A and B) in the coronary effluent, and increased the cardiac formazan content (Fig. 2C) in D-MI/R rats compared with that in the untreated D-MI/R group. Moreover, there was no significant difference in the levels of LDH, CK-MB or formazan content between the C-S and D-S groups. These data indicate that Nar decreased the myocardial enzyme content and increased cardiac tissue viability in D-MI/R rats.

Figure 2.

Effect of Nar on myocardial enzyme levels and cardiac viability in diabetic MI/R rats. Levels of (A) LDH and (B) CK-MB in the coronary effluent were detected using spectrophotometry by commercial assay kits. (C) Cardiac formazan content was measured using an MTT assay. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=3/group). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with the STZ-sham group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 compared with the STZ-M/IR group. LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; CK-MB, creatine kinase myocardial band; STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion; Nar, naringenin.

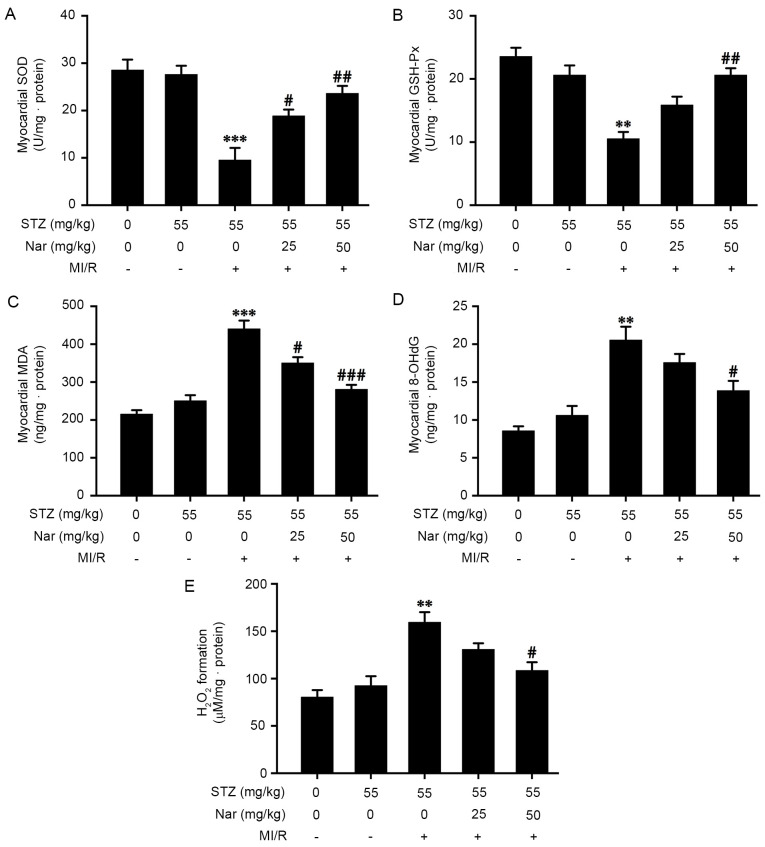

Nar inhibits myocardial oxidative stress in D-MI/R rats

To confirm that Nar alleviates MI/R injury in diabetic rats, the present study investigated whether Nar antagonized myocardial oxidative stress by observing the effects of Nar on the activity of GSH-Px and SOD, and the levels of MDA, 8-OHdG and H2O2 in the myocardium of D-MI/R rats. In the D-MI/R group, upregulation in the content of MDA, 8-OHdG and H2O2, and downregulation in the activities of GSH-Px and SOD in the myocardium of D-MI/R rats were observed, compared with the D-S group, while these effects were markedly reversed by pretreatment with Nar (Fig. 3A-E). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in myocardial oxidative stress indexes between the C-S and D-S groups. These data indicated that Nar inhibited myocardial oxidative stress in D-MI/R rats (Fig. 3A-E).

Figure 3.

Effect of Nar on myocardial oxidative stress in diabetic MI/R rats. Activities of (A) SOD and (B) GSH-Px, and the levels of (C) MDA, (D) 8-OHdG as well as (E) H2O2 formation in the myocardium were determined by spectrophotometry using commercially available kits. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=3/group). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with the STZ-sham group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 compared with the STZ-M/IR group. GSH-Px, glutathione peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde; 8-OHdG, 8-hydroxy-2 deoxyguanosine; STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion; Nar, naringenin.

Nar improves cardiac function in D-MI/R rats

To confirm that Nar alleviates MI/R injury in diabetic rats, the present study sought to determine whether Nar ameliorated cardiac function by observing the effects of Nar on left ventricular hemodynamic parameters in D-MI/R rats. As shown in Fig. 4, compared with the D-S group, the D-MI/R group had lower LVSP and ±dP/dtmax, as well as higher LVEDP. However, pretreatment with HN for 30 days significantly increased LVSP and ±dP/dtmax, and reduced LVEDP in D-MI/R rats (Fig. 4A-D). In addition, there were no significant differences in LVSP, LVEDP or ±dP/dtmax between the C-S and D-S groups. These data indicate that Nar alleviated cardiac dysfunction in D-MI/R rats (Fig. 4A-D).

Figure 4.

Effect of Nar on cardiac function in diabetic MI/R rats. (A) LVSP, (B) LVEDP, (C) +dP/dtmax and (D) -dP/dtmax were recorded using a hemodynamic monitoring system. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=6-8/group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with the STZ-sham group; #P<0.05 and ##P<0.01 compared with the STZ-M/IR group. STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion; Nar, naringenin; LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; +dP/dtmax, peak rate of left ventricular maximal systolic/diastolic velocity rise; -dP/dtmax, peak rate of left ventricular maximal systolic/diastolic velocity fall.

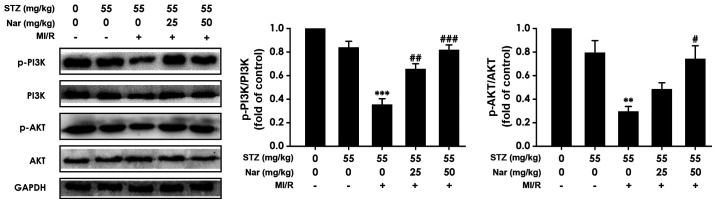

Nar upregulates myocardial PI3K/AKT signaling in D-MI/R rats

To explore whether the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway was involved in the Nar-mediated protection against MI/R injury in diabetic rats, the present study determined whether Nar regulated PI3K/AKT signaling. As represented in Fig. 5, the ratios of p-PI3K/PI3K and p-AKT/AKT were significantly downregulated in D-MI/R rats, while pretreatment with Nar markedly abolished this downregulation (Fig. 5), indicating that enhanced PI3K/AKT signaling may contribute to the Nar-mediated protection against MI/R injury in diabetic rats.

Figure 5.

Effect of Nar on PI3K/AKT signaling in diabetic MI/R rats. The protein levels of p-PI3K, PI3K, p-AKT, AKT and GAPDH in myocardium were detected by western blotting. Data are presented the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=3/group). **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 compared with the STZ-sham group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 compared with the STZ-M/IR group. STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion; Nar, naringenin.

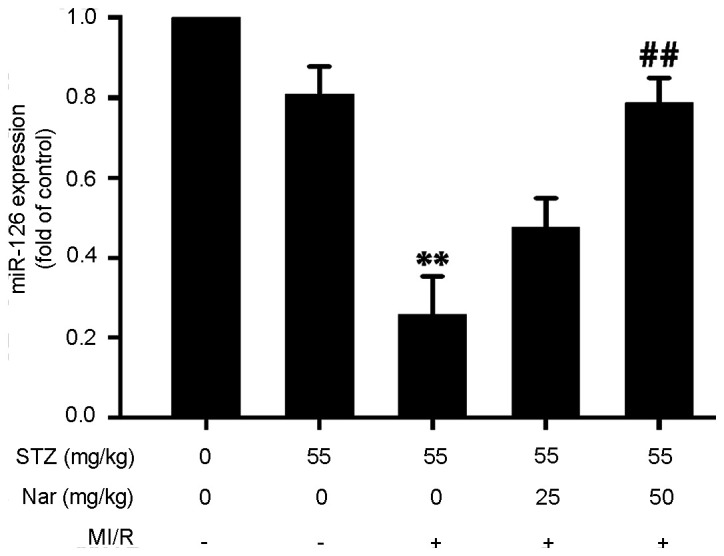

Nar upregulates myocardial miR-126 expression in D-MI/R rats

To investigate whether miR-126 was involved in the Nar-mediated protection against MI/R injury in diabetic rats, the present study examined the effect of Nar on myocardial miR-126 expression in D-MI/R rats. Myocardial miR-126 expression was significantly lower in D-MI/R rats compared with that in the D-S group, while HN significantly reversed this downregulation of miR-126 in D-MI/R rats (Fig. 6), indicating that the upregulation of miR-126 may participate in the Nar-mediated protection against MI/R injury in diabetic rats.

Figure 6.

Effect of Nar on miR-126 expression in diabetic MI/R rats. Relative expression levels of myocardial miR-126 were determined using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (number of repeated measurements: n=3/group). **P<0.01 compared with the STZ-sham group; ##P<0.01 compared with the STZ-M/IR group. miR, microRNA; STZ, streptozotocin; MI/R, myocardial ischemia reperfusion; Nar, naringenin.

Discussion

The anti-MI/R injury role of Nar has been previously reported (19,20,39). Activation of PI3K/AKT signaling alleviates MI/R injury (24-26), and enhanced miR-126 prevents MI/R injury (27,28). The present study used STZ-induced diabetic rats to investigate whether Nar could ameliorate MI/R injury in diabetes, and to explore the role of the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in Nar-mediated protection. The primary findings were as follows: i) Nar decreased myocardial enzyme content and enhanced cardiac tissue viability in D-MI/R rats; ii) Nar inhibited myocardial oxidative stress in D-MI/R rats; iii) Nar improved cardiac function in D-MI/R rats; and iv) Nar upregulated the myocardial miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in D-MI/R rats. In summary, these findings revealed that Nar prevented MI/R injury by upregulating the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis.

In the present study, STZ-induced diabetic rats were exposed to MI/R to establish an ex vivo model of I/R injury. Myocardial enzymes, such as CK-MB and LDH, are released into the plasma during the I/R process due to the loss of myocardial membrane integrity, and are regarded as indicators of MI/R damage (40,41). The present results show that MI/R upregulated the levels of CK-MB and LDH of the coronary effluent following 5 min of reperfusion, and decreased cardiac viability in diabetic rats. Moreover, the main functional manifestation of MI/R injury is cardiac dysfunction, especially systolic and diastolic dysfunction (42,43). The results of the present study showed that MI/R downregulated LVSP and ±dP/dtmax, and upregulated LVEDP in diabetic rats. Substantial evidence indicates that oxidative stress is a major contributing factor to MI/R injury (1,28,34,44). It is known that the activity of SOD and GSH-Px can be used as an objective index to evaluate the scavenging capacity of ROS (45). MDA and 8-OHdG are well-known biomarkers of lipid and DNA peroxidation, respectively, indicating lipid and DNA damage caused by excessive ROS (46,47). In the present study, compared with the D-S group, D-MI/R rats had decreased activities of GSH-Px and SOD, and increased levels of MDA, 8-OHdG and H2O2. These results indicate that D-MI/R rats had upregulated levels of myocardial enzymes, reduced cardiac tissue viability, and enhanced oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction, suggesting the successful establishment of the I/R injury model.

MI/R injury can be triggered while treating IHD (1,4,5). IHD is a leading cause of death in patients with diabetes (6). Therefore, effective approaches against D-MI/R injury may provide a better outcome in the management of diabetic IHD. It has been shown that Nar prevents MI/R injury (19,20,39,48). Thus, the present study aimed to determine whether Nar protected against MI/R injury in diabetic heart. The results showed that Nar reduced the myocardial enzyme content of the coronary effluent, increased cardiac tissue viability, alleviated the oxidative stress level and improved cardiac function in D-MI/R rats. These data indicate that Nar has the ability to alleviate MI/R injury in diabetic rats. The antioxidative effect of Nar has been confirmed in lens (49), retina (50) and renal (51) cells of diabetic rats. In addition, Nar exhibits a protective role on cardiac hypertrophy in STZ-induced diabetic mice (52). These previous findings offer a reasonable explanation for the results obtained in the present study. Therefore, it can be suggested that Nar is an effective therapeutic drug for MI/R injury in diabetic heart.

The present study also investigated the possible underlying mechanism for the protective role of Nar against D-MI/R injury. It has been shown that activation of PI3K/AKT signaling ameliorates MI/R injury (24-26). Notably, miR-126 may be a therapeutic agent for diabetes mellitus (30) and MI/R injury (27,28). Therefore, it was hypothesized that the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis may be involved in Nar-mediated protection against D-MI/R injury. The present study evaluated the role of Nar on myocardial miR-126 and PI3K/AKT signaling in D-MI/R rats. It was revealed that Nar reversed the MI/R-reduced miR-126 expression level, as well as the ratios of p-PI3K/PI3K and p-AKT/AKT in D-MI/R rats, which suggested that the upregulation of the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis contributed to the beneficial effect of Nar on D-MI/R injury. It has previously been confirmed that the antidiabetic effect of Nar is exerted by activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (53). In addition, the activation the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is involved in in the protection mediated by dexmedetomidine (54) and eplerenone (55) against I/R injury in the heart of diabetic rats. Furthermore, long non-coding RNA cardiac hypertrophy-related factor modulates the progression of cerebral I/R injury via the miR-126/SOX6 signaling pathway (56). These previous findings offer a reasonable explanation for the results obtained in the present study.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that Nar was able to prevent MI/R injury and upregulate the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in D-MI/R rats. These results indicated that Nar ameliorated MI/R injury by upregulating the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis in diabetic heart, and suggest that Nar may act as a potential preventive agent for MI/R injury in diabetes, which is important for improving the therapeutic effect of diabetic IHD including antioxidant, improvement of myocardial enzyme level and enhancement of cardiac activity and function.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

Funding: This study was supported by the Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Fund Project (grant nos. A2017494 and A2016267).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

SHL and MSW performed the experiments and data analysis. MRW was a contributor in analyzing the data and writing the manuscript. WLK contributed to the experimental design and manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Guangdong Medical (Zhanjiang, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1121–1135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra071667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pell VR, Chouchani ET, Frezza C, Murphy MP, Krieg T. Succinate metabolism: A new therapeutic target for myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111:134–141. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whayne TF Jr. Ischemic heart disease and the Mediterranean diet. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2014;16(491) doi: 10.1007/s11886-014-0491-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordlie MA, Wold LE, Simkhovich BZ, Sesti C, Kloner RA. Molecular aspects of ischemic heart disease: Ischemia/reperfusion-induced genetic changes and potential applications of gene and RNA interference therapy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2006;11:17–30. doi: 10.1177/107424840601100102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feyzizadeh S, Badalzadeh R. Application of ischemic postconditioning's algorithms in tissues protection: Response to methodological gaps in preclinical and clinical studies. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:2257–2267. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orchard TJ, Costacou T. When are type 1 diabetic patients at risk for cardiovascular disease? Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10:48–54. doi: 10.1007/s11892-009-0089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gharravi AM, Jafar A, Ebrahimi M, Mahmodi A, Pourhashemi E, Haseli N, Talaie N, Hajiasgarli P. Current status of stem cell therapy, scaffolds for the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2018;12:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2018.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whittington HJ, Babu GG, Mocanu MM, Yellon DM, Hausenloy DJ. The diabetic heart: Too sweet for its own good? Cardiol Res Pract. 2012;2012(845698) doi: 10.1155/2012/845698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li N, Yang YG, Chen MH. Comparing the adverse clinical outcomes in patients with non-insulin treated type 2 diabetes mellitus and patients without type 2 diabetes mellitus following percutaneous coronary intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16(238) doi: 10.1186/s12872-016-0422-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lejay A, Fang F, John R, Van JA, Barr M, Thaveau F, Chakfe N, Geny B, Scholey JW. Ischemia reperfusion injury, ischemic conditioning and diabetes mellitus. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2016;91:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jha JC, Ho F, Dan C, Jandeleit-Dahm K. A causal link between oxidative stress and inflammation in cardiovascular and renal complications of diabetes. Clin Sci (Lond) 2018;132:1811–1836. doi: 10.1042/CS20171459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salehi B, Fokou PV, Sharifi-Rad M, Zucca P, Pezzani R, Martins N, Sharifi-Rad J. The therapeutic potential of naringenin: A review of clinical trials. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2019;12(E11) doi: 10.3390/ph12010011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Testai L, Da Pozzo E, Piano I, Pistelli L, Gargini C, Breschi MC, Braca A, Martini C, Martelli A, Calderone V. The citrus flavanone naringenin produces cardioprotective effects in hearts from 1 year old rat, through activation of mitoBK channels. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8(71) doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han X, Pan J, Ren D, Cheng Y, Fan P, Lou H. Naringenin-7-O-glucoside protects against doxorubicin-induced toxicity in H9c2 cardiomyocytes by induction of endogenous antioxidant enzymes. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46:3140–3146. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2008.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han X, Ren D, Fan P, Shen T, Lou H. Protective effects of naringenin-7-O-glucoside on doxorubicin-induced apoptosis in H9C2 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008;581:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han XZ, Gao S, Cheng YN, Sun YZ, Liu W, Tang LL, Ren DM. Protective effect of naringenin-7-O-glucoside against oxidative stress induced by doxorubicin in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Biosci Trends. 2012;6:19–25. doi: 10.5582/bst.2012.v6.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arafa HM, Abd-Ellah MF, Hafez HF. Abatement by naringenin of doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity in rats. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2005;17:291–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chtourou Y, Slima AB, Makni M, Gdoura R, Fetoui H. Naringenin protects cardiac hypercholesterolemia-induced oxidative stress and subsequent necroptosis in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67:1090–1097. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu LM, Dong X, Zhang J, Li Z, Xue XD, Wu HJ, Yang ZL, Yang Y, Wang HS. Naringenin attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via cGMP-PKGIα signaling and in vivo and in vitro studies. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019(7670854) doi: 10.1155/2019/7670854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu LM, Dong X, Xue XD, Zhang J, Li Z, Wu HJ, Yang ZL, Yang Y, Wang HS. Naringenin improves mitochondrial function and reduces cardiac damage following ischemia-reperfusion injury: The role of the AMPK-SIRT3 signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2019;10:2752–2765. doi: 10.1039/c9fo00001a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.You Q, Wu Z, Wu B, Liu C, Huang R, Yang L, Guo R, Wu K, Chen J. Naringin protects cardiomyocytes against hyperglycemia-induced injuries in vitro and in vivo. J Endocrinol. 2016;230:197–214. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yao H, Han X, Han X. The cardioprotection of the insulin-mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2014;14:433–442. doi: 10.1007/s40256-014-0089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viard P, Butcher AJ, Halet G, Davies A, Nürnberg B, Heblich F, Dolphin AC. PI3K promotes voltage-dependent calcium channel trafficking to the plasma membrane. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:939–946. doi: 10.1038/nn1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shen D, Chen R, Zhang L, Rao Z, Ruan Y, Li L, Chu M, Zhang Y. Sulodexide attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress induced by myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:5063–5075. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang BF, Jiang H, Chen J, Guo X, Li Y, Hu Q, Yang S. Nobiletin ameliorates myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury by attenuating endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated apoptosis through regulation of the PI3K/AKT signal pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;73:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng T, Wang Y, Wang C, Yan H. FABP4 silencing ameliorates hypoxia reoxygenation injury through the attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis by activating PI3K/Akt pathway. Life Sci. 2019;224:149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang C, Ji N, Luo G, Ni S, Zong J, Chen Z, Bao D, Gong X, Fu T. The effects and mechanism of miR-92a and miR-126 on myocardial apoptosis in mouse ischemia-reperfusion model. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2014;70:1901–1906. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Zheng Y, Wang M, Yan M, Jiang J, Li Z. Exosomes derived miR-126 attenuates oxidative stress and apoptosis from ischemia and reperfusion injury by targeting ERRFI1. Gene. 2019;690:75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2018.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moghaddam AS, Afshari JT, Esmaeili SA, Saburi E, Joneidi Z, Momtazi-Borojeni AA. Cardioprotective microRNAs: Lessons from stem cell-derived exosomal microRNAs to treat cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2019;285:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pishavar E, Behravan J. miR-126 as a Therapeutic Agent for Diabetes Mellitus. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:3309–3314. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170424120121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Naderi R, Mohaddes G, Mohammadi M, Alihemmati A, Khamaneh A, Ghyasi R, Ghaznavi R. The effect of garlic and voluntary exercise on cardiac angiogenesis in diabetes: The role of miR-126 and miR-210. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2019;112:154–162. doi: 10.5935/abc.20190002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhutada P, Mundhada Y, Bansod K, Bhutada C, Tawari S, Dixit P, Mundhada D. Ameliorative effect of quercetin on memory dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2010;94:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayrami G, Alihemmati A, Karimi P, Javadi A, Keyhanmanesh R, Mohammadi M, Zadi-Heydarabad M, Badalzadeh R. Combination of vildagliptin and ischemic postconditioning in diabetic hearts as a working strategy to reduce myocardial reperfusion injury by restoring mitochondrial function and autophagic activity. Adv Pharm Bull. 2018;8:319–329. doi: 10.15171/apb.2018.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao C, Xia ML, Wang J, Zhou XR, Lou YY, Tang LH, Zhang FJ, Yang JT, Qian LB. Luteolin attenuates cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats by modulating Nrf2 antioxidative function. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019(2719252) doi: 10.1155/2019/2719252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu L, Liang H, Dong X, Zhao G, Jin Z, Zhai M, Yang Y, Chen W, Liu J, Yi W, et al. Reduced silent information regulator 1 signaling exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in type 2 diabetic rats and the protective effect of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2015;59:376–390. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang JT, Qian LB, Zhang FJ, Wang J, Ai H, Tang LH, Wang HP. Cardioprotective effects of luteolin on ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats are modulated by eNOS and the mitochondrial permeability transition pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;65:349–356. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Y, Duan W, Jin Z, Yi W, Yan J, Zhang S, Wang N, Liang Z, Li Y, Chen W, et al. JAK2/STAT3 activation by melatonin attenuates the mitochondrial oxidative damage induced by myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Pineal Res. 2013;55:275–286. doi: 10.1111/jpi.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng LM, Ma HJ, Guo H, Kong QQ, Zhang Y. The cardioprotective effect of naringenin against ischemia-reperfusion injury through activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channel in rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;94:973–978. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2016-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar A, Kaur H, Devi P, Mohan V. Role of coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) in cardiac disease, hypertension and Meniere-like syndrome. Pharmacol Ther. 2009;124:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du L, Zhang H, Zhao H, Cheng X, Qin J, Teng T, Yang Q, Xu Z. The critical role of the zinc transporter Zip2 (SLC39A2) in ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;132:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang M, Kong DY, Chen JC. Inhibition of miR-148b ameliorates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:17757–17766. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mamamtavrishvili ND, Sharashidze NS, Abashidze RI, Kvirkveliia AA. Metabolic issues of ischemia induced myocardial dysfunction. Georgian Med News. 2011;195:40–43. (In Russian) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinning C, Westermann D, Clemmensen P. Oxidative stress in ischemia and reperfusion: Current concepts, novel ideas and future perspectives. Biomarkers Med. 2017;11:11031–11040. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2017-0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taysi S, Tascan AS, Ugur MG, Demir M. Radicals, oxidative/nitrosative stress and preeclampsia. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2019;19:178–193. doi: 10.2174/1389557518666181015151350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kołodziej U, Maciejczyk M, Miąsko A, Matczuk J, Knaś M, Żukowski P, Żendzian-Piotrowska M, Borys J, Zalewska A. Oxidative modification in the salivary glands of high fat-diet induced insulin resistant rats. Front Physiol. 2017;8(20) doi: 10.3389/fphys.2017.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao H, Zhao M, Wang Y, Li F, Zhang Z. Glycyrrhizic acid prevents sepsis-induced acute lung injury and mortality in rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 2016;64:125–137. doi: 10.1369/0022155415610168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kara S, Gencer B, Karaca T, Tufan HA, Arikan S, Ersan I, Karaboga I, Hanci V. Protective effect of hesperetin and naringenin against apoptosis in ischemia/reperfusion-induced retinal injury in rats. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014(797824) doi: 10.1155/2014/797824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wojnar W, Zych M, Kaczmarczyk-Sedlak I. Antioxidative effect of flavonoid naringenin in the lenses of type 1 diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:974–984. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.09.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Dosari DI, Ahmed MM, Al-Rejaie SS, Alhomida AS, Ola MS. Flavonoid naringenin attenuates oxidative stress, apoptosis and improves neurotrophic effects in the diabetic rat retina. Nutrients. 2017;9(E1161) doi: 10.3390/nu9101161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Roy S, Ahmed F, Banerjee S, Saha U. Naringenin ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat renal impairment by downregulation of TGF-β1 and IL-1 via modulation of oxidative stress correlates with decreased apoptotic events. Pharm Biol. 2016;54:1616–1627. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2015.1110599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang J, Qiu H, Huang J, Ding S, Huang B, Wu Q, Jiang Q. Naringenin exhibits the protective effect on cardiac hypertrophy via EETs-PPARs activation in streptozocin-induced diabetic mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;502:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.05.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nishina A, Sato D, Yamamoto J, Kobayashi-Hattori K, Hirai Y, Kimura H. Antidiabetic-like effects of naringenin-7-O-glucoside from edible chrysanthemum ‘Kotobuki’ and naringenin by activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and PPARγ. Chem Biodivers. 2019;16(e1800434) doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201800434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheng X, Hu J, Wang Y, Ye H, Li X, Gao Q, Li Z. Effects of dexmedetomidine postconditioning on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in diabetic rats: Role of the PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling pathway. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018(3071959) doi: 10.1155/2018/3071959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mahajan UB, Patil PD, Chandrayan G, Patil CR, Agrawal YO, Ojha S, Goyal SN. Eplerenone pretreatment protects the myocardium against ischaemia/reperfusion injury through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway in diabetic rats. Mol Cell Biochem. 2018;446:91–103. doi: 10.1007/s11010-018-3276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gai HY, Wu C, Zhang Y, Wang D. Long non-coding RNA CHRF modulates the progression of cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury via miR-126/SOX6 signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;514:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.