Abstract

Background

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage is suggested as the first approach in the management of symptomatic and complex walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Dual approach with percutaneous drainage could be the best choice when the necrosis is deep extended till the pelvic paracolic gutter; however, the available catheter could not be large enough to drain solid necrosis neither to perform necrosectomy, entailing a higher need for surgery. Therefore, percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy through a large bore percutaneous self-expandable metal stent has been proposed.

Case presentation

In this study, we present the case of a 61-year-old man admitted to our hospital with a history of sepsis and persistent multiorgan failure secondary to walled-off pancreatic necrosis due to acute necrotizing pancreatitis. Firstly, the patient underwent transgastric endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage using a lumen-apposing metal stent and three sessions of direct endoscopic necrosectomy. Because of recurrence of multiorgan failure and the presence of the necrosis deeper to the pelvic paracolic gutter at computed tomography scan, we decided to perform percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy using an esophageal self-expandable metal stent. After four sessions of necrosectomy, the collection was resolved without complications. Therefore, we perform a revision of the literature, in order to provide the state-of-art on this technique. The available data are, to date, derived by case reports and case series, which showed high rates both of technical and clinical success. However, a not negligible rate of adverse events has been reported, mainly represented by fistulas and abdominal pain.

Conclusion

Dual approach, using lumen apposing metal stent and percutaneous self-expandable metal stent, is a compelling option of treatment for patients affected by symptomatic, complex walled-off pancreatic necrosis, allowing to directly remove large amounts of necrosis avoiding surgery. Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy seems a promising technique that could be part of the step-up-approach, before emergency surgery. However, to date, it should be reserved in referral centers, where a multidisciplinary team is disposable.

Keywords: Necrotizing pancreatitis, Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy, Walled-off pancreatic necrosis, Endoscopic necrosectomy, Lumen-apposing metal stent

Background

Acute pancreatitis could be complicated by necrosis of the pancreatic gland or peripancreatic tissue in 10–20% of cases [1, 2]. The subset of patients that develop necrosis and superadded infection of the necrotic tissue has a mortality rate that could rank 30% if they are untreated and 6.7% if drainage is performed [1]. Therefore, interventional procedures, especially endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage, are to date recommended by guidelines for the treatment of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) [2, 3].

In the last decade, lumen apposing metal stents (LAMS) have been put into the market, favoring the development of EUS-guided drainage and facilitating direct endoscopic necrosectomy (DEN). When the extension of the necrosis to the pelvic paracolic gutter is present, a transmural endoscopic drainage could be insufficient and a dual approach using percutaneous drainage is recommended [2, 3]. However, even when large catheters are used, the percutaneous treatment could represent an unsatisfactory gateway for solid necrosis. On the other hand, surgical necrosectomy, even though a minimally invasive approach, is burdened by high mortality and complication rates [4]. Therefore, a percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy (PEN) through self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) has been proposed, showing promising results [5–8].

In this study, we proposed a dual approach with EUS-guided drainage using LAMS and percutaneous drainage using a large bore SEMS for the treatment of a symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) extended to the pelvic paracolic gutter. Moreover, a comprehensive review of the literature has been performed, in order to provide an overview of the available evidences of this technique.

Case presentation

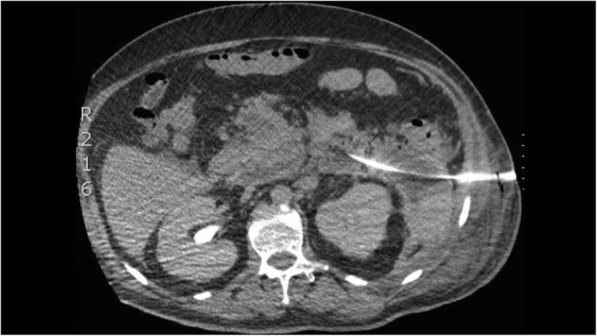

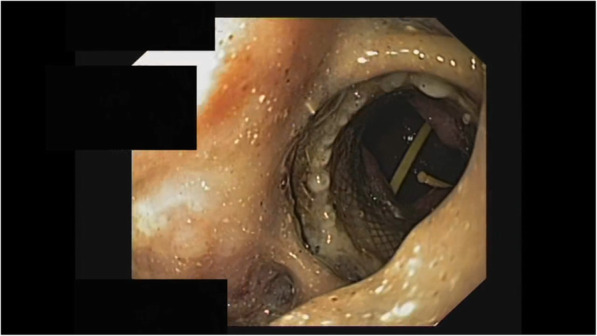

A 61-year-old man developed signs of severe sepsis with multiorgan failure (MOF) 3 weeks after the onset of an acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP). A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the presence of a large WOPN with signs of infection and the patient underwent EUS-guided drainage using LAMS 20 × 10mm (Hot-Axios, Boston Scientific Corp., Marlborough, MA, USA). Three sessions of DEN were performed and the patient rapidly recovered, although a large amount of necrosis was still remnant. After 3 weeks from LAMS placement, the patient newly developed MOF and septic shock; a new CT scan showed an increased amount of necrosis extended deep to the left pelvic paracolic gutter. Because of the severe clinical conditions, surgery was excluded and we decided to perform a percutaneous drainage using a large bore SEMS. Using CT guidance, a catheter was inserted on the left side of the abdomen reaching the necrotic collection (Fig. 1); therefore, the tract was balloon dilated and an esophageal SEMS (TaeWoong Niti-S 20 × 100 mm) was placed over a guidewire (Fig. 2). A balloon-dilation on the stent was done in order to allow the entrance of the gastroscope within the collection (Fig. 3), and a first session of PEN was performed using a snare, leading a rapid resolution of the sepsis. Four sessions of PEN were completed; between each session, irrigation with saline solution and instillation of antibiotics and amphotericin were performed.

Fig. 1.

CT scan previous percutaneous SEMS placement

Fig. 2.

Radiological view of the EC-LAMS and of the percutaneous stent placed on the left side of the abdomen

Fig. 3.

Endoscopic appearance of the cavity after SEMS placement, with view of the EC-LAMS in place

Two weeks after SEMS placement, the LAMS was pulled out, while the percutaneous stent was removed 1 week later, when a complete resolution of the necrosis was obtained (Fig. 4). The large cutaneous bore fistula was sutured and medicated for two months. The patient was discharged 3 weeks later after SEMS removal. No immediate or late complications occurred. At long-term follow-up, 557 days, the patient is asymptomatic, without evidence of recurrence of the collection.

Fig. 4.

CT scan after SEMS removal showing a complete resolution of the collection

From sinus tract endoscopy to SEMS-assisted percutaneous necrosectomy for the treatment of WOPN: a literature overview

In the early 2000s, Carter and colleagues described the development of a minimally invasive approach to retroperitoneal/peripancreatic necrosis, using percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy (PEN, often referred to as sinus tract endoscopy) for the debridement of solid necrotic tissue with either a flexible or a rigid endoscopic system [9]. Ten patients were managed using a percutaneous approach plus PEN as the primary treatment. Except for two patients who died from MOF, the remaining eight patients recovered without the need of adjuvant open surgical treatment, providing an 80% success rate. Moreover, 60% of patients were treated outside the intensive care unit (ICU), because they did not require organ support.

Technically, percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy was preceded by the placement of a percutaneous drainage catheter by interventional radiologists, typically providing an immediate relief of symptoms by decompressing the fluid part of the collection, but that can be inadequate in case of consistent solid necrotic tissue, thus resulting in persistence of sepsis. After the stabilization of the percutaneous tract, a sequential use of upsizing drain (over 28Fr) or dilatation using a CRE™ balloon was performed, allowing the introduction of a pediatric or adult standard upper endoscope into the collection. The necrotic cavity was initially inspected through serial lavages with sterile normal saline and CO2 insufflation; then, several endoscopic devices can be used to remove the necrotic tissue, such as rat-tooth forceps, polypectomy snare, and Dormia basket.

After this first experience, several studies and case reports regarding percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy have been published [10–17], identifying in the above technique an efficient and safe alternative to video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement (VARD) in the treatment of infected WOPN located distal from the gastrointestinal tract. In their retrospective analysis, Moyer et al. [16] reported a clinical success rate of about 82% (19/23), represented by 1-year sustained resolution of symptoms and fluid collection. Likewise, Jain and colleagues [17], whom recently published the largest observational cohort study including 53 patients with either acute, infected necrotic collections or WOPN, achieved a 77% clinical success rate. Indeed, about 12 out of 53 patients (23%) required additional surgical necrosectomy due to persistence of sepsis and organ failure. Post-procedural adverse events varied widely across the studies, reaching a 25% rate at follow-up [16], which was similar to those recently reported in a meta-analysis of three randomized control trials (RCTs) comparing the clinical outcomes between endoscopy (using EUS-guided drainage via cystogastrostomy or cystoenterostomy) and minimally invasive surgery treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis [18].

As we have already highlighted, the abovementioned technique is not free from complications. In fact, in order to gain a wide opening access to the collection, repeated balloon dilatations are required, carrying not only the risk of bleeding [5], but also to postpone the necrosectomy session until the maturity of the skin tract. Together with the need of multiple PEN sessions to achieve the complete debridement of necrotic tissue, these limitations flowed into the use of covered esophageal SEMS as firstly described in 2011 by Navarrete et al. [5], allowing to easily achieve and maintain a stable access to the cavity. Several other case reports and studies [6–8, 19–26] describing PEN through SEMS for the management of complex WOPN were published thereafter, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of studies and case reports using SEMS for percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy

| Study, year of publication | Patients,n | Mean age, y | Type of collection | Size of collection, mean, cm (range) | Previous endoscopic/sur-gical treatment attempt (n) | Mean number of PEN sessions performed | Length of time stent in place, mean, days | Peri-procedural complications, type (n) | Additional surgical intervention for incomplete debridement,n | Clinical success and outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pérez Cuadrado Robles, 2020 | 1 | 72 | WOPN | 23 | LAMS placement, percutaneous catheter drainage | 2 | N/A | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

| Ke, 2019 | 23 | 43 | WOPN | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage (23) | 2 | 7 | Minor bleeding conservatively treated (1) | 5 | 11 patients (48%) had either a major complication and/or died (e.g. septic shock and MOF, hemorrhagic shock), pancreatic fistula (2) |

| Tringali, 2018 | 3 | 45 | WOPN | 15 (7-20) | Percutaneous catheter drainage (3) | 3 | 12.7 | None (0) | 0 | Fluid collection’s recurrence with fever (1) |

| Thorsen, 2018 | 5 | 44 | WOPN | 33.4 (26-54) | Percutaneous catheter drainage (3), ETDN (2) | 5.75 | 37.5 | None (0) | 0 |

Septic shock and death (1), productive cutaneous fistula (2) |

| Saumoy, 2017 | 9 | 62 | WOPN | 11.2 (4.7-17.1) | Percutaneous catheter drainage (9) | 3 | 14.7 | None (0) | 0 | MOF and death (1) |

| D’Souza, 2017 | 1 | 32 | WOPN | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage | 1 | N/A | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

| Sato, 2016 | 1 | 13 | WOPN | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage | 3 | 17 | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

| Kedia, 2015 | 1 | 56 | WOPN | 17 | Percutaneous catheter drainage, ETDN | 2 | N/A | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

| Ceredo-Rodriguez, 2014 | 1 | 43 | WOPN | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage, surgical lavages | 7 | N/A | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

| Bakken, 2011 | 2 | 70 | WOPN | N/A | N/A | 2.5 | 25 | 1 | N/A | N/A |

| Bakken, 2011 | 1 | 75 | WOPN | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage | N/A | N/A | None (0) | N/A | N/A |

| Navarrete, 2011 | 1 | 37 | Infected pseudocyst | N/A | Percutaneous catheter drainage | 4 | 12 | None (0) | 0 | 100% clinical success |

PEN percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy, WOPN walled-off pancreatic necrosis, MOF multi-organ failure, PD leak pancreatic duct leak, ETDN endoscopic trans-gastric drainage and necrosectomy

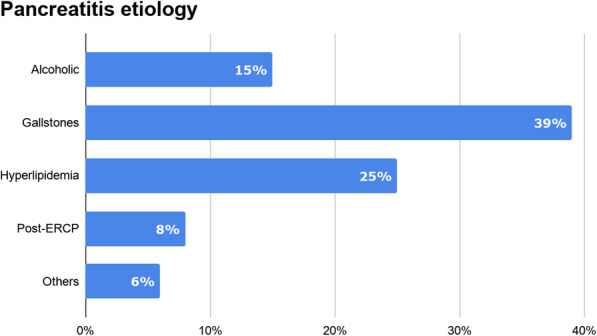

Considering all the published studies, 49 patients have been treated using this technique, with a technical success of 100% [5–8, 19–26]. Regarding the etiology of ANP, summarized in Fig. 5, gallstones emerged as the most common cause, accounting for almost 40% of cases (19/48), which is in line with data derived from Western countries [27].

Fig. 5.

Distribution of pancreatitis etiology in SEMS-assisted percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy studies

Although some differences regarding the definition of clinical success has emerged, the referred rates ranged from 65 to 89% [6, 8, 25]. The number of PEN sessions needed for WOPN resolution varied widely, from 1 to 7, and the mean time for stent removal ranged between 7 and 37 days (range 3–65) [5–8, 19–26]. Additional minimally invasive debridement procedures (i.e., percutaneous and/or trans-gastric, even simultaneous) was required in up to 65% of patients [8, 25], while 30% of patients (7/23) received additional open surgery as reported by Ke and colleagues [25], most of them (5/23) because of inadequate endoscopic debridement of necrotic tissue.

Furthermore, most of the studies reported a wide range of several complications occurred during the hospitalization, including enteric/colonic fistula, compartment syndrome with muscle necrosis, and ongoing septic shock requiring invasive life support measures, mainly related to the clinically severe form of ANP. Indeed, no severe, procedure-related adverse events were observed, and the rate of pancreatic fistula was significantly lower compared to the surgical approach, as emerged in the TENSION trial [4–8, 19–26]. However, this translates into a lengthening of hospitalization as emerged in Thorsen et al. study [6]. Patients included in this series were discharged after a mean of 61 days after percutaneous SEMS removal, although the length of the hospital stay varied among patients and were strongly influenced by the several complications occurred (i.e., stomach and colon perforation after ETDN attempt, aspiration pneumonia, critical illness neuropathy etc.). In the case series by Tringali and colleagues [7], the median length of hospitalization after esophageal stent placement was 18 days, similar with those reported by Navarrete and Cerecedo-Rodriguez and colleagues (15 and 21 days, respectively) [5, 21].

Discussion

Complex WOPN and extended necrotic tissue without a mature capsule are hard-to-treat conditions and potentially life-threatening. Nevertheless, a standard technique is not yet defined, and it is quite clear that a single approach could be unsatisfactory. In fact, it has become increasingly evident that a multidisciplinary, step-up strategy in the treatment of symptomatic fluid collections and infected WOPN leads to better clinical outcomes and lower rates of adverse events than more aggressive treatments [4, 28, 29]. As stated by various international guidelines [2, 3], percutaneous drainage (PCD) or endoscopic transluminal drainage actually represent the initial step, based on location of the necrotic collections and local expertise, and a dual approach is suggested, especially when the necrosis is extended deep to the pelvic paracolic gutter. PCD has the advantage of being widely available and can provide immediate relief of symptoms in those patients who are too ill to undergo endoscopic maneuver, often acting as the first drainage procedure of choice, particularly when necrosis is located distal from both stomach and duodenum. However, solid necrotic tissue cannot be effectively evacuated by small caliber percutaneous catheters and frequently requires direct debridement for complete resolution. To date, therefore, several endoscopic options of treatment of necrotic collections have been proposed and are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Endoscopic treatment options for the management of pancreatic fluid collections

| Procedure | Gateway | Type of stent and diameter | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmural endoscopic drainage with plastic stents |

• Cystogastrostomy • Cystoduodenostomy |

Double-pigtail 7-10 Fr |

• Low cost • Easy placement and removal • Active or passive drainage (with or without nasocystic drain) |

• Small caliber (increased risk of occlusion and secondary infection) • Often need for multiple stents • Possibility of fluid leak and migration • Poor visibility under fluoroscopy during the procedure |

| Transmural endoscopic drainage with FCSEMSs |

• Cystogastrostomy • Cystoduodenostomy |

Tubular biliary stents 6-10 mm |

• Large caliber • Possibility to perform DEN through stent • Prevent fluid leak • Good visibility under fluoroscopy • Haemostatic effect at puncture site |

• Cost • Difficult placement • Increased risk of stent migration and delayed bleeding (even for the possibility of GI tract injury) |

| Transmural endoscopic drainage with LAMSs |

• Cystogastrostomy • Cystoduodenostomy |

• AXIOS™, 10-15-20 mm (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) • SPAXUS™, 8-10-16 mm (Taewoong Medical, Gimpo, Korea) • NAGI™, 10-16 mm (Taewoong Medical, Gimpo, Korea) • AixstentⓇ PPS, 10-15 mm (Leufen Medical, Berlin, Germany) • Hanaro stentⓇ, 10 mm (Mi-TECH-Medical Co, Seoul, South Korea) |

• Large caliber • Easy placement, even without the need for wire exchange • Easy removal • Possibility to perform DEN through stent • Lower risk of migration • Reduced need for fluoroscopy and nasocystic drain placement |

• Cost • Increased risk of suprainfection and bleeding in the early phases (<14 days) |

| Transpapillary drainage via ERCP | • Major/minor duodenal papilla |

Pancreatic endoprosthesis 5-7 Fr |

• Active or passive drainage (with or without nasal drain) • Evidence of pancreatic duct disruption • Considered as an alternative when the distance from the GI wall to the PFC is too large (>10-15 mm) |

• Limited use in WOPN with poorly-liquefied necrotic tissue |

| Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy | • Percutaneous approach |

Esophageal, partially or fully-covered SEMS 18-20 mm |

• Single or multiport gateway • Possibility to perform DEN even if PFC is located distal from the GI tract • Reduced need of deep sedation |

• Preceded by the creation of cutaneous fistula by interventional radiologists • Increased risk of peri-procedural bleeding |

FCSEMS fully-covered self-expandable metal stents, DEN direct endoscopic necrosectomy, GI gastro-intestinal, LAMSs lumen-apposing metal stents, ERCP Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, PFC pancreatic fluid collection

We believe that placement of a large bore percutaneous SEMS allows to overcome these limitations by performing direct necrosectomy with either a standard or therapeutic flexible endoscope, which offers greater maneuverability and penetration into deep recesses than VARD. This technique might also lead to faster debridement and decreased invasiveness. In fact, the use of a SEMS protecting the skin tract could reduce the risk of wound-related complications, like infection and incisional hernia. Moreover, endoscopic necrosectomy is mainly performed under moderate conscious sedation and does not require general anesthesia. This is an important advantage also applicable to PEN, which leads to less systemic pro-inflammatory response and minimal collateral damages in already critically ill patients, thereby improving patients’ quality of life [12, 15, 25]. Although not yet addressed, PEN could be cost-effective and future studies should estimate its economic benefits.

Although both the TENSION and MISER trials showed no difference in terms of mortality between endoscopic and surgical step-up approach, patients undergoing endoscopic procedures had lower rate of disease-related adverse events (i.e., abdominal pain, infection), shorter length of ICU stay and hospitalization, and more economic advantages [4, 29]. Unfortunately, there is limited data about PEN through SEMS and its clinical outcomes, even if the available evidences are encouraging. In our experience, SEMS-assisted PEN was technically feasible, leading to the resolution of symptoms and stent removal in 20 days, in line with those previously reported [5, 7, 8, 22, 25]. Moreover, we did not experience any periprocedural or delayed adverse event, though we do not have to disregard the possible risks of a combined approach (i.e., bleeding, suprainfection, stent migration and stent occlusion due to the LAMS [30], abdominal pain).

Main concerns were about avoidance of a chronic pancreatic-cutaneous fistula (PCF) that could undermine long-term clinical outcomes and patient’s quality of life. As reported by Ross et al. [31], a dual-modality approach, in which endoscopic trans-enteric stents were placed into the necrotic collection immediately after percutaneous drainage, allowed redirection of pancreatic juice back into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. This could decrease the risk of PCF development in patients with disconnected duct syndrome due to the severe pancreatic inflammation. In our case, the cutaneous fistula was conservatively treated and its closure was obtained after 2 months.

Only another case of WOPN drained using a dual endoscopic approach with LAMS and percutaneous SEMS has been reported [26]; in this report, however, the percutaneous drainage was made in two steps, with the esophageal SEMS placed 4 days after the percutaneous access achievement. In our study, instead, the percutaneous procedure was made in a single step, allowing to rapidly gain a large bore gateway to perform endoscopic necrosectomy in the same session. Moreover, the percutaneous stent turned out to be a convenient access to perform high-volume lavages using saline solution and intracystic instillation of antibiotics and antimicrobial agents.

In our opinion, this approach appears to be safe and perfectly suits the extended concept of “dual-approach,” overcoming the limits of both endoscopy and radiology and highlighting the need for multidisciplinarity in this particular setting of patients. However, there are several limitations, mainly due to the lack of high-quality evidence. In fact, the dual-endoscopic technique, especially for PEN, needs to be further refined, with determination of the optimum interval between sessions, end-point during each session, and the final end-point. Furthermore, it should be performed in referral centers, with availability of expert endoscopists, interventional radiologists, and surgical facilities.

Conclusions

Patients affected by WOPN with deep extension of the necrosis are “hard-to-treat” patients, and a dual approach using LAMS and percutaneous, large bore SEMS is a compelling option of treatment that could maximize debridement volume and reduce the need for surgery. Further studies are needed to define the clinical outcome and the cost-effectiveness of this approach.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Abbreviations

- EUS

Endoscopic ultrasound

- WOPN

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis

- PEN

Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy

- SEMS

Self-expandable metal stent

- MOF

Multiorgan failure

- ANP

Acute necrotizing pancreatitis

- LAMS

Lumen apposing metal stent

- DEN

Direct endoscopic necrosectomy

- CT

Computed tomography

- PFCs

Pancreatic fluid collections

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- VARD

Video-assisted retroperitoneal debridement

- RCTs

Randomized control trials

- PCD

Percutaneous drainage

- PCF

Pancreatic-cutaneous fistula

- GI

Gastrointestinal

Authors’ contributions

CB: study design, collection of data, drafting and critical review of the literature and critical revision. MS: collection of data, drafting and critical revision. MLM: drafting, tables, figures and review of literature. DC: video, review of literature and critical revision; AV: critical revision. MT: review of literature and critical revision. VA, EG, LA: critical revision. CF: study design and critical revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that they received no funding.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval and consent were waived because this study is a review of literature with a retrospective case report on one patient that gave consent to participate for publication.

Consent for publication

The patient gave consent for publication.

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS, Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62(1):102–111. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron TH, DiMaio CJ, Wang AY, Morgan KA. American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update: management of pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(1):67–75.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvanitakis M, Dumonceau J-M, Albert J, Badaoui A, Bali MA, Barthet M, Besselink M, Deviere J, Oliveira Ferreira A, Gyökeres T, Hritz I, Hucl T, Milashka M, Papanikolaou IS, Poley JW, Seewald S, Vanbiervliet G, van Lienden K, van Santvoort H, Voermans R, Delhaye M, van Hooft J. Endoscopic management of acute necrotizing pancreatitis: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) evidence-based multidisciplinary guidelines. Endoscopy. 2018;50(5):524–546. doi: 10.1055/a-0588-5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Brunschot S, van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Boermeester MA, et al. Endoscopic or surgical step-up approach for infected necrotising pancreatitis: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2018;391(10115):51–58. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarrete C, Castillo C, Caracci M, Vargas P, Gobelet J, Robles I. Wide percutaneous access to pancreatic necrosis with self-expandable stent: new application (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(3):609–610. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thorsen A, Borch AM, Novovic S, Schmidt PN, Gluud LL. Endoscopic necrosectomy through percutaneous self-expanding metal stents may be a promising additive in treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9):2456–2465. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5131-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tringali A, Vadalà di Prampero SF, Bove V, Perri V, La Greca A, Pepe G, et al. Endoscopic necrosectomy of walled-off pancreatic necrosis by large-bore percutaneus metal stent: a new opportunity? Endosc Int Open. 2018;6(3):E274–E278. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-125313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saumoy M, Kumta NA, Tyberg A, Brown E, Lieberman MD, Eachempati SR, Winokur RS, Gaidhane M, Sharaiha RZ, Kahaleh M. Transcutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis in the paracolic gutter. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(5):458–463. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter CR, McKay CJ, Imrie CW. Percutaneous necrosectomy and sinus tract endoscopy in the management of infected pancreatic necrosis: an initial experience. Ann Surg. 2000;232(2):175–180. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200008000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mui LM, Wong SKH, Ng EKW, Chan ACW, Chung SCS. Combined sinus tract endoscopy and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in management of pancreatic necrosis and abscess. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(3):393–397. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-9120-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zuber-Jerger I, Zorger N, Kullmann F. Minimal invasive necrosectomy in severe pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):e45. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhingra R, Srivastava S, Behra S, Vadiraj PK, Venuthurimilli A, Shalimar, et al. Single or multiport percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy performed with the patient under conscious sedation is a safe and effective treatment for infected pancreatic necrosis (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(2):351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathers B, Moyer M, Mathew A, Dye C, Levenick J, Gusani N, Dougherty-Hamod B, McGarrity T. Percutaneous debridement and washout of walled-off abdominal abscess and necrosis using flexible endoscopy: a large single-center experience. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(1):E102–E106. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-107802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamamoto N, Isayama H, Takahara N, Sasahira N, Miyabayashi K, Mizuno S, et al. Percutaneous direct-endoscopic necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis. Endoscopy. 2013;45(S 02):E44–E45. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goenka MK, Goenka U, Mujoo MY, Tiwary IK, Mahawar S, Rai VK. Pancreatic necrosectomy through sinus tract endoscopy. Clin Endosc. 2018;51(3):279–284. doi: 10.5946/ce.2017.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moyer MT, Walsh LT, Manzo CE, Loloi J, Burdette A, Mathew A. Percutaneous debridement and washout of walled-off abdominal abscess and necrosis by the use of flexible endoscopy: an attractive clinical option when transluminal approaches are unsafe or not possible. VideoGIE Off Video J Am Soc Gastrointest Endosc. 2019;4(8):389–393. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain S, Padhan R, Bopanna S, Jain SK, Dhingra R, Dash NR, Madhusudan KS, Gamanagatti SR, Sahni P, Garg PK. Percutaneous endoscopic step-up therapy is an effective minimally invasive approach for infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(2):615–622. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Arnoletti JP, Varadarajulu S. Superiority of endoscopic interventions over minimally invasive surgery for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: meta-analysis of randomized trials. Dig Endosc. 2020;32(3):298–308. doi: 10.1111/den.13470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakken JC, Baron TH. Pancreatic necrosectomy via percutaneous self-expandable metal stent placement. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73(4):AB103. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.03.1217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakken JC, Baron TH. Use of partially covered and fully covered self expandable metal stents to establish percutaneous access for endoscopic necrosectomy. Endoscopy. 2011;43(Suppl 1):A69. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerecedo-Rodriguez J, Hernández-Trejo A, Alanís-Monroy E, Barba-Mendoza JA, del Tress-Faez MPB, Figueroa-Barojas P. Endoscopic percutaneous pancreatic necrosectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80(1):165–166. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato S, Takahashi H, Sato M, Yokoyama M, Itoi T, Kawano Y, Kawashima H. A case of walled-off necrosis with systemic lupus erythematosus: successful treatment with endoscopic necrosectomy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46(2):e13–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kedia P, Parra V, Zerbo S, Sharaiha RZ, Kahaleh M. Cleaning the paracolic gutter: transcutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy through a fully covered metal esophageal stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81(5):1252. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.D’Souza L, Korman A, Carr-Locke D, Benias P. Percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy. Endoscopy. 2017;49(10):E242–E243. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-114407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ke L, Mao W, Zhou J, Ye B, Li G, Zhang J, Wang P, Tong Z, Windsor J, Li W. Stent-assisted percutaneous endoscopic necrosectomy for infected pancreatic necrosis: technical report and a pilot study. World J Surg. 2019;43(4):1121–1128. doi: 10.1007/s00268-018-04878-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pérez-Cuadrado-Robles E, Berger A, Perrod G, Ragot E, Cuenod CA, Rahmi G, Cellier C. Endoscopic treatment of walled-off pancreatic necrosis by simultaneous transgastric and retroperitoneal approaches. Endoscopy. 2020;52(3):E88–E89. doi: 10.1055/a-1011-3555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Dijk SM, Hallensleben NDL, van Santvoort HC, Fockens P, van Goor H, Bruno MJ, Besselink MG, Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group Acute pancreatitis: recent advances through randomised trials. Gut. 2017;66(11):2024–2032. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Timmer R, Laméris JS, Kruyt PM, Manusama ER, van der Harst E, van der Schelling GP, Karsten T, Hesselink EJ, van Laarhoven CJ, Rosman C, Bosscha K, de Wit RJ, Houdijk AP, van Leeuwen MS, Buskens E, Gooszen HG. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(16):1491–1502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bang JY, Arnoletti JP, Holt BA, Sutton B, Hasan MK, Navaneethan U, et al. An endoscopic transluminal approach, compared with minimally invasive surgery, reduces complications and costs for patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):1027–1040.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fugazza A, Sethi A, Trindade AJ, Troncone E, Devlin J, Khashab MA, Vleggaar FP, Bogte A, Tarantino I, Deprez PH, Fabbri C, Aparicio JR, Fockens P, Voermans RP, Uwe W, Vanbiervliet G, Charachon A, Packey CD, Benias PC, el-Sherif Y, Paiji C, Ligresti D, Binda C, Martínez B, Correale L, Adler DG, Repici A, Anderloni A. International multicenter comprehensive analysis of adverse events associated with lumen-apposing metal stent placement for pancreatic fluid collection drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;91(3):574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ross AS, Irani S, Gan SI, Rocha F, Siegal J, Fotoohi M, Hauptmann E, Robinson D, Crane R, Kozarek R, Gluck M. Dual-modality drainage of infected and symptomatic walled-off pancreatic necrosis: long-term clinical outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(6):929–935. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.