Abstract

In the fight against COVID-19, there remains an unmet need for point-of-care (POC) diagnostic testing tools that can rapidly and sensitively detect the causative SARS-CoV-2 virus to control disease transmission and improve patient management. Emerging CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection assays are viewed as transformative solutions for POC diagnostic testing, but their lack of streamlined sample preparation and full integration within an automated and portable device hamper their potential for POC use. We report herein POC-CRISPR – a single-step CRISPR-Cas-assisted assay that incoporates sample preparation with minimal manual operation via facile magnetic-based nucleic acid concentration and transport. Moreover, POC-CRISPR has been adapted into a compact thermoplastic cartridge within a palm-sized yet fully-integrated and automated device. During analytical evaluation, POC-CRISPR was able detect 1 genome equivalent/μL SARS-CoV-2 RNA from a sample volume of 100 μL in < 30 min. When evaluated with 27 unprocessed clinical nasopharyngeal swab eluates that were pre-typed by standard RT-qPCR (Cq values ranged from 18.3 to 30.2 for the positive samples), POC-CRISPR achieved 27 out of 27 concordance and could detect positive samples with high SARS-CoV-2 loads (Cq < 25) in 20 min.

Keywords: CRISPR, Point-of-Care, Sensors, Viruses

1. Introduction

Since its initial report in December 2019, COVID-19 has rapidly spread across the globe (Mattingly et al., 2018). As of June, 2021, there are more than 170 million confirmed cases and more than 3.7 million deaths worldwide. In the fight against this pandemic, diagnostic testing that can rapidly and sensitively detect the causative SARS-CoV-2 virus at the point-of-care (POC) is identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a top priority (World Health Organization, 2020) toward controlling disease transmission and improving patient management. The global scientific community has responded with unprecedented urgency and has developed a remarkable number of diagnostic tests. To date, diagnostic tests that detect SARS-CoV-2 antigens via lateral flow immunoassays (e.g., Sofia SARS Antigen FIA, BD Veritor™ Plus System, and Abbott BinaxNOW COVID-19 Ag Card) offer the speed and simplicity suitable for POC testing but their lack of sensitivity undercuts their usefulness. On the other hand, diagnostic tests that detect viral RNA via nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) generally have higher sensitivity but have yet to be used at POC. Indeed, despite promising advances and several evaluation studies (Assennato et al., 2020; Basu et al., 2020; Brendish et al., 2020; Collier et al., 2020; Gibani et al., 2020; Zhen et al., 2020), even commercial NAAT-based diagnostic tests such as Abbott's ID NOW COVID 19 test (Basu et al., 2020) and Cepheid's Xpert Xpress SARS-CoV-2 (Loeffelholz et al., 2020) have mostly remained in hospitals and centralized clinical labs instead of used at POC.

CRISPR-Cas-assisted diagnostic assays (e.g., SHERLOCK (Gootenberg et al., 2017) and DETECTR (Chen et al., 2018)) have in recent years captured significant attention (Bhattacharyya et al., 2018; Chiu, 2018; Li et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2018). Aided by the elegant detection mechanism, these assays have demonstrated fast detection while obviating instrument-intensive thermocycling. As a result, CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection assays (Broughton et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Hou et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020; Patchsung et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021) are viewed as transformative solutions for POC diagnostic testing. Developing a POC diagnostic test from this nascent method, however, still must address technical requirements such as ease of use, portability, and resource/infrastructure independence, which entails reducing assay steps, minimizing manual operation in sample preparation, and integrating with automated and portable devices. Despite their seminal status, both DETECTR-based (Broughton et al., 2020) and SHERLOCK-based SARS-CoV-2 detection (Patchsung et al., 2020) are ill-suited for POC use because they involve multiple manual assay steps and can only be performed with input SARS-CoV-2 RNA that is already extracted and purified by benchtop instruments. More recent assays (Arizti-Sanz et al., 2020; Ding et al., 2020; Fozouni et al., 2021; Joung et al., 2020; Ning et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021) are more tenable for POC use but have yet to fully meet these requirements. For example, AIOD-CRISPR (Ding et al., 2020), a one-step CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (Piepenburg et al., 2006) (RT-RPA) assay, and the amplification-free CRISPR-Cas13a assay (Fozouni et al., 2021) have incorporated portable detection modalities (e.g., mobile phone), but both still require benchtop-extracted SARS-CoV-2 RNA as the input and separate heating modules for incubation. A new SHERLOCK assay called STOPCovid.v2 (Joung et al., 2020) aims to address sample preparation by coupling one-step CRISPR-Cas12b-assisted reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification (Notomi, 2000) (RT-LAMP) to benchtop magnetic-based RNA extraction, but the multiple manual steps in this assay present challenges for POC use. Thus, there has yet to see a CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection assay that satisfies the requirements for POC use (Nouri et al., 2021).

In response, we have developed POC-CRISPR – the first one-step CRISPR-Cas-assisted assay that is fully integrated with sample preparation and implemented in a POC-amenable device. Sample preparation in POC-CRISPR is achieved through droplet magnetofluidics (DM) (Chiou et al., 2013; Lehmann et al., 2006; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang and Wang, 2013), which uses magnetic-based capture and transport of nucleic acid-binding magnetic beads to concentrate and purify SARS-CoV-2 RNA from a large volume of swab eluate, as well as to transport the RNA to downstream amplification and detection. We have subsequently developed a DM-compatible, one-step, fluorescence-based CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay for SARS-CoV-2 detection. To facilitate POC use, we have adapted the assay within a thermoplastic cartridge that is smaller than a lateral flow strip and has comparable material cost, and we have engineered a palm-sized DM device for automating the assay in the cartridge. As a demonstration, we tested POC-CRISPR with 27 unprocessed clinical nasopharyngeal swabs that were pre-typed by standard RT-qPCR, where POC-CRISPR achieved 27 out of 27 concordance and was able to detect positive samples with high SARS-CoV-2 loads in 20 min.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Assay cartridge for POC-CRISPR

The assay cartridge, which houses a sample well, a wash buffer well, and a reaction mixture well, was fabricated from inexpensive plastic components via laser-cutting and thermoforming. The cartridge was composed of 3 layers: a top cap layer that was made of laser-cut polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) laminated with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tape for establishing a sample injection opening while enclosing the rest of the cartridge, a center spacer layer that was made of laser-cut PMMA laminated with pressure-adhesive tape (PSA, 9472LE adhesive transfer tape, 3M, USA) on both sides for joining the layers, and a bottom well layer that was thermoformed from a polypropylene sheet for holding the assay reagents. Upon fabrication of these individual layers, the spacer layer and the well layer were first assembled via PSA into an open cartridge. Both the cap layer and the open cartridge were kept at room temperature until use.

2.2. Integrated portable DM device for POC-CRISPR

The integrated portable DM device for automating POC-CRISPR was engineered based on our previous work (Trick et al., 2021). The main housing and the detachable faceplate of the device were both 3D-printed (Formlabs Form 2, black resin) and embedded with permanent neodymium magnets, such that the two parts could be aligned and magnetically clasped for attachment. The device was composed of a motorized magnetic arm, a miniature heating module, and a fluorescence detector (Fluo Sens Integrated, Qiagen), all of which were connected to a microcontroller (Arduino Uno R3) with a motorshield (Arduino Motor Shield Rev3) and a custom printed circuit board shield. The motorized magnetic arm, located within the main housing, was a 3D-printed shaft with a pair of permanent neodymium magnets that was actuated by a rotational servo motor (HS–485HB Hitec RCD, Poway, CA, USA) and a linear servo motor (PQ12-R Actuonix, Victoria, BC, Canada). The bi-axial movement of the motorized magnetic arm pulled the beads in and out of each well, as well as across different wells, of the assay cartridge, thereby achieving magnetic transfer within the cartridge. The miniature heating module, located on the detachable faceplate, was an assembly of an aluminum heat block, a thermoelectric cooler, a heat sink, and a miniature fan. The temperature of the heating module was monitored and controlled by the microcontroller with electrical current supplied by the motorshield.

2.3. POC-CRISPR

Prior to performing POC-CRISPR, assay cartridges with pre-loaded reagents were prepared. Specifically, 50 μL wash buffer and 20 μL CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture (see Supplementary Information for reagents and reaction assembly) were loaded into the wash buffer well and the reaction mixture well of an open cartridge, respectively. The cap layer was then capped onto the open cartridge via PSA before 450 μL silicone oil (50 cSt, Millipore-Sigma, USA) was injected through the sample injection opening to cover both the wash buffer well and the reaction mixture well. The immiscible silicone oil layer above the wash buffer and the reaction mixture served both as a medium for transporting the magnetic beads in the cartridge and as a separator that prevented mixing of assay reagents between the wells. The cartridge was either used immediately or placed on ice with the sample injection opening sealed with tape (Scotch Magic Tape, 3M, USA) until use.

For performing POC-CRISPR, a sample (up to 100 μL in input volume) was pipette mixed with 14 μL magnetic bead buffer and then loaded into the sample well of the assay cartridge. After sample loading, the cartridge was tape sealed and mounted onto the faceplate of the portable DM device with the reaction mixture well of the assay cartridge seated in the aluminum heat block, whose inner surface was coated with a thermally conductive paste (Arctic Silver 5, Visalia, California, USA) for ensuring consistent thermal contact between the reaction mixture well and the heat block during reaction incubation. The faceplate was then magnetically clasped onto the main housing of the device, such that the sample well was positioned between the pair of permanent magnets of the magnetic arm.

POC-CRISPR began with a 2-min automated sample preparation process, during which the magnetic beads and bound RNA were concentrated from the sample well, transferred to the wash buffer well for wash, and finally transferred to the reaction mixture well. Once the magnetic beads and bound RNA arrived in the reaction mixture well, the heating module began heating to initiate CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 RT-RPA with real-time fluorescence detection. All reactions were incubated at 45.5 °C (unless otherwise specified) for 60 min. After the heat block reached 45.5 °C, the fluorescence detector (set at a predefined detector current of 65 mA) measured the fluorescence signal from the reaction every 10 s.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overview of POC-CRISPR

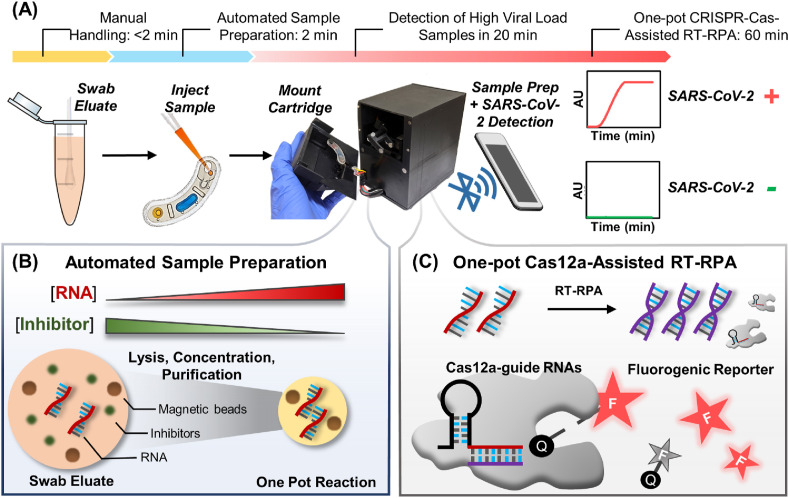

POC-CRISPR detects SARS-CoV-2 virus directly from unprocessed clinical NP swab eluates in a sample-to-result workflow powered by the integrated portable DM device (Fig. 1 A). POC-CRISPR begins by injecting the swab eluate and a magnetic bead buffer into an assay cartridge and mounting the cartridge in the portable DM device. This process takes < 2 min hands-on time and represents the only manual process in POC-CRISPR. Within the portable DM device, a motorized magnetic arm, a miniature heating module, and a compact fluorescence detector are programmed by a microcontroller to execute DM-enabled sample preparation (Fig. 1B) and CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA (Fig. 1C) – the two crucial assay components in POC-CRISPR. In this work, DM-enabled sample preparation from clinical NP swab eluates is facilitated by pH-mediated electrostatic attraction between RNA and functionalized magnetic beads (Cao et al., 2006). Briefly, the swab eluate is first exposed to a low-pH binding buffer supplemented with a detergent, in which the viral particles are lysed. The released negatively charged viral RNA can electrostatically bind to the positively charged magnetic beads. As the magnetic beads can be concentrated, they offer an effective strategy for concentrating RNA from large volumes of swab eluates and boosting the assay sensitivity. When the magnetic beads and bound RNA are magnetically transported out of the swab eluate, potential inhibitors to CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA are left behind. Moreover, as the magnetic beads and bound RNA are magnetically transported into a neutral-pH wash buffer, RNA remains bound to the magnetic beads while potential inhibitors that may have adsorbed to the magnetic beads can be released into the wash buffer, thereby achieving further purification. As a result of DM-enabled sample preparation, concentrated and purified RNA can be delivered to the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture. Within this reaction, SARS-CoV-2 RNA is transcribed and amplified by RT-RPA into DNA amplicons, which activate Cas12a-guide RNA complexes to cleave single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) fluorogenic reporters, thereby producing fluorescent signals for detection (Fig. 1C). Finally, the resulting real-time fluorescence curves signal the presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 virus in the NP swab eluate.

Fig. 1.

Overview of POC-CRISPR. (A) POC-CRISPR detects SARS-CoV-2 virus from unprocessed nasopharyngeal (NP) swab eluates in a sample-to-answer workflow. Upon injecting the NP swab eluate into an assay cartridge and mounting the cartridge into a palm-sized droplet magnetofluidic (DM) device, the device performs sample preparation, reaction incubation, and fluorescence-based SARS-CoV-2 detection in full automation. (B) Within the device, sample preparation is powered by DM, which leverages magnetic-based capture and transport of nucleic acid-binding magnetic beads to concentrate SARS-CoV-2 RNA and remove potential inhibitors from a large volume of NP swab eluate, as well as to transport the RNA into downstream CRISPR-Cas-assisted reaction mixture. (C) Within the reaction, SARS-CoV-2 RNA is in vitro transcribed and amplified into DNA amplicons via reverse transcription recombinase polymerase amplification (RT-RPA). The DNA amplicons then activate Cas12a-guide RNA complexes to cleave single-stranded DNA fluorogenic reporters, thereby producing fluorescent signals for detection.

3.2. Development of DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay

As a prerequisite for realizing POC-CRISPR, we first developed a DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay using manual magnetic bead purification and benchtop reaction incubation. As the testbed, we employed standardized synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA as the target and ChargeSwitch magnetic beads and binding buffer as the magnetic bead buffer as in our previous works (Shin et al, 2017, 2018). For SARS-CoV-2 amplification and detection, a fluorescence-based CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA is adopted and modified from AIOD-CRISPR (Ding et al., 2020) and our recently developed deCOViD (Park et al., 2021) that used a more sensitive, Alexa647 fluorophore-based ssDNA fluorogenic reporter (Hsieh et al., 2020) (Table S1). For developing this new assay, we mixed SARS-CoV-2 RNA with the magnetic bead buffer and used a magnetic rack to pellet and wash the magnetic beads and bound RNA. We next added the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture and used a benchtop qPCR instrument to incubate the reaction and measure the fluorescence. We finally analyzed the real-time fluorescence amplification curves from the reactions to assess the reaction conditions. We note that, aside from differences in assay components and conditions, our benchtop DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection assay shares a comparable workflow as STOPCovid.v2 (Joung et al., 2020).

We investigated a range of parameters in our benchtop DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay to improve its performance in SARS-CoV-2 detection. In these investigations, we used 100 μL of 100 genome equivalent (GE)/μL RNA as the sample – up to 100-fold greater in sample volume than typical CRISPR-Cas-assisted assays in which ~1–5 μL samples are spiked directly into the reaction mixtures – because magnetic beads could capture and concentrate RNA from such a large sample volume. We first observed that CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA produced the strongest amplification signal with the magnetic beads still in the reaction mixture compared to bead removal prior to incubation (Figure S1). Also, while multiple reverse transcriptases supported DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA, WarmStart RTx reverse transcriptase allowed the fastest and most efficient detection among the reverse transcriptases we tested (Figure S2). As WarmStart RTx reverse transcriptase reacts optimally at 55 °C, we next tuned the reaction temperature and found that our assay was the most efficient at 43 °C and 45 °C (Figure S3). Finally, we adjusted the concentrations of WarmStart RTx reverse transcriptase, Cas12a, Cas12a-guide RNAs, and ssDNA fluorogenic reporter, and selected 1.50 U/μL WarmStart RTx reverse transcriptase (Figure S4), 0.32 μM Cas12a in combination with 0.16 μM each of Cas12a-guide RNAs (Figure S5), and 4 μM ssDNA fluorogenic reporter (Figure S6) for our assay. Upon tuning these reaction conditions, when detecting 100 μL of 100 GE/μL SARS-CoV-2 RNA, our DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA could yield real-time fluorescence amplification curves with onsets of fluorescence increase at ~20 min and strong fluorescence signals in 60 min (Figure S5 and Figure S6).

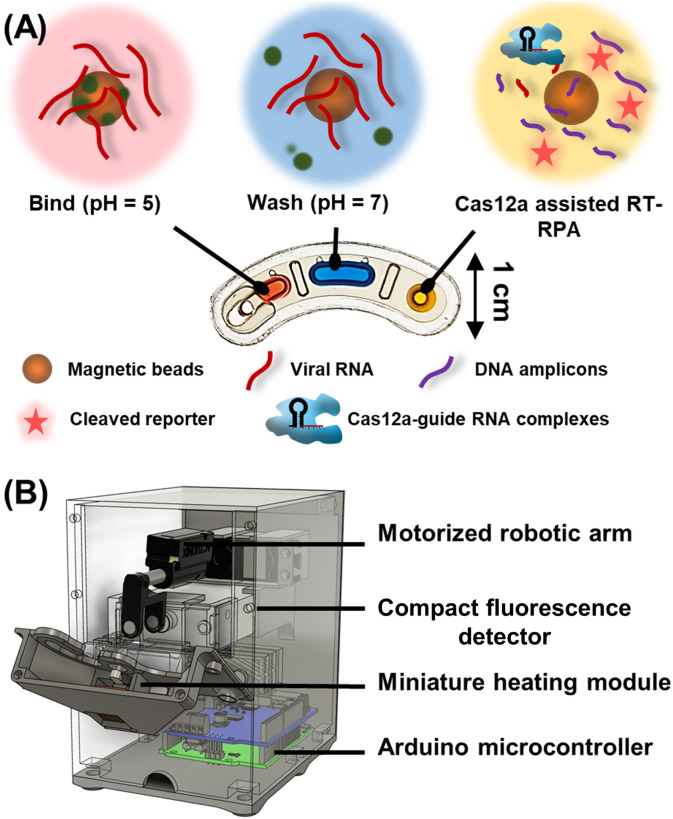

3.3. Development of assay cartridge and integrated portable DM device for POC-CRISPR

We next developed the disposable thermoplastic assay cartridge and the integrated portable DM device for turning the DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay into a POC-amenable assay. The assay cartridge has a compact footprint that is smaller than a lateral flow strip (Fig. 2 A) and is fabricated via simple assembly (Figure S7) of low-cost plastic materials (Table S2). The assay cartridge has 3 independent wells for holdings the mixture of sample and magnetic bead buffer (pH = 5), a wash buffer (pH = 7), and the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture, which are further separated by an immiscible oil that prevents evaporation and mixing of these aqueous reagents. Upon sample loading, to further reduce cross-contamination, each disposable assay cartridge is tape-sealed and mounted in the integrated portable DM device. The device houses a motorized magnetic arm, a miniature heating module, a compact fluorescence detector, and a microcontroller for automating these components (Fig. 2B; also see Table S3 for cost breakdown). Briefly, the motorized magnetic arm, which is equipped with a pair of permanent magnets located at the opposing ends of the assay cartridge, moves bi-axially to concentrate, and sequentially transport the magnetic beads from the sample well to the wash buffer well and then to the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture well (Figure S8). Upon the arrival of the magnetic beads and RNA, the heating module heats the reaction mixture well to initiate the reaction while the fluorescence detector measures the fluorescence emitted from the reaction in real time. Finally, the portable device can be connected to a laptop or even wirelessly interfaced with a smartphone via Bluetooth connection and a custom app (Figure S9), which offers an attractive option for resource limited settings. Finally, for minimizing carryover contamination, which can be detrimental to POC diagnostic tesing, the sealed cartridge is discarded after testing.

Fig. 2.

Assay cartridge and integrated portable DM device for POC-CRISPR. (A) The assay cartridge, which is fabricated via simple assembly of inexpensive thermoplastic materials, has 3 independent wells for holding the mixture of sample and magnetic bead buffer (pH = 5), a wash buffer (pH = 7), and the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture. An immiscible oil overlays these aqueous reagents to prevent evaporation and reagent mixing. After injection of sample into the assay cartridge, the pH-responsive magnetic beads can bind to SARS-CoV-2 RNA and transport the RNA to the wash buffer – where the RNA remains beads-bound due to the neutral pH – and finally to the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture. (B) The integrated portable DM device (represented here with a CAD schematic) houses a motorized magnetic arm for manipulating magnetic beads and executing sample preparation procedures, a miniature heating module for controlling the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction temperature, a compact fluorescence detector for detecting the fluorescence emitted from the reaction in real-time, and a microcontroller for controlling these components and hence automating the assay in the cartridge.

3.4. Rapid and sensitive SARS-CoV-2 detection via POC-CRISPR

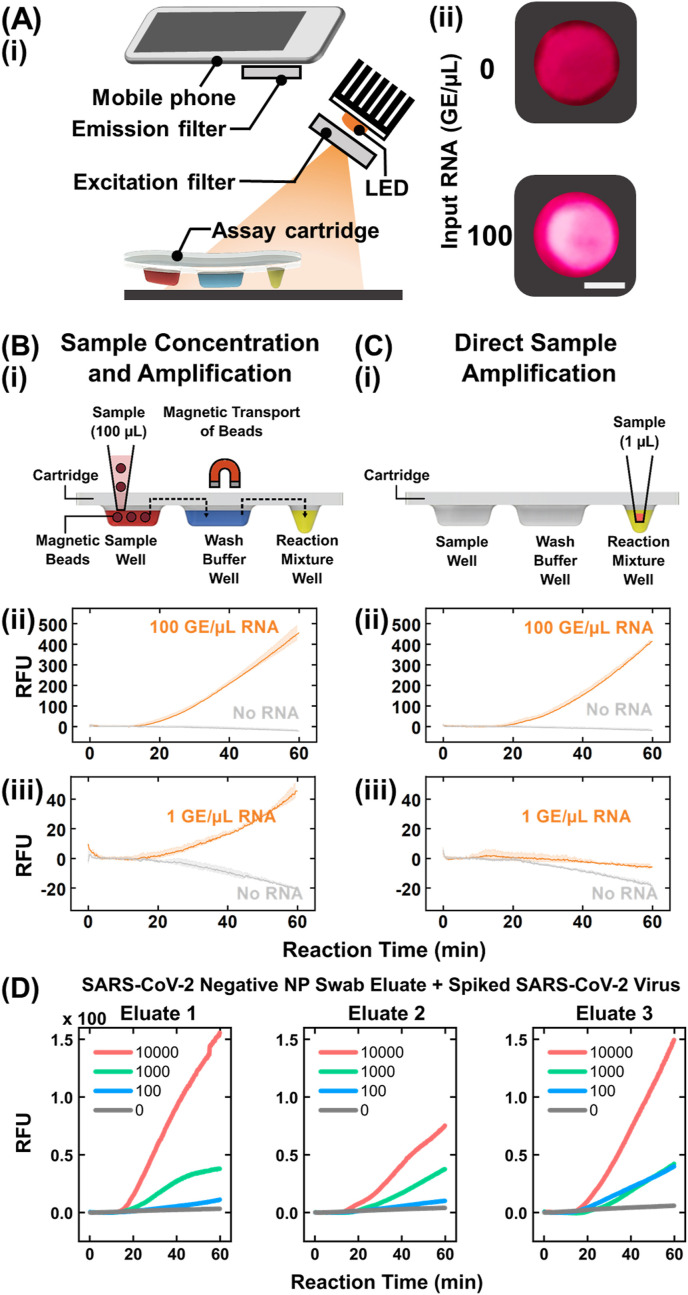

To actualize POC-CRISPR, we adapted the benchtop DM-compatible CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA assay in the assay cartridge and the DM device. Here, we performed initial characterizations using 100 μL synthetic SARS-CoV-2 RNA (100 GE/μL) as the sample, which was loaded into the sample well of the assay cartridge before mounting the cartridge in the DM device and initiating the automated workflow in the device. To account for potential differences between the benchtop qPCR instrument and the miniature heating module in the DM device, we tuned the reaction temperature in the DM device and set it at 45.5 °C for POC-CRISPR (Figure S10). We also found that assembled assay cartridges with CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture could be stored on ice up to 6 h (Figure S11). In addition to detecting the fluorescence via the fluorescence detector in the DM device, we set up a simple and compact fluorescence visualization apparatus using a red LED with an excitation filter for illuminating the reaction mixture well of the cartridge and a smartphone with an emission filter for visualizing the fluorescence (Fig. 3 A(i)). Using this apparatus, we observed strong fluorescence from 100 GE/μL SARS-CoV-2 RNA but only weak fluorescence from the no RNA control (Fig. 3A(ii)). These results not only provide an additional verification method for POC-CRISPR, but also illustrate the potential for further simplifying the instrumentation and reducing the cost for POC-CRISPR.

Fig. 3.

Analytical validation of POC-CRISPR. (A) For simply visualizing POC-CRISPR results in the assay cartridge, (i) a simple apparatus based on a LED and a smartphone can be used to image the cartridges and (ii) differentiate the weak fluorescence in the cartridge with 0 genome equivalent (GE)/μL RNA (top) from the strong fluorescence in the cartridge with 100 GE/μL RNA (bottom). White scale bar = 0.25 cm. (B) (i) In POC-CRISPR, magnetic-mediated concentration of RNA from a large sample volume (e.g., 100 μL) and subsequent automated transfer of magnetic beads and bead-bound RNA to the wash buffer and the reaction mixture within the cartridge enable sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2. Using POC-CRISPR, (ii) 100 GE/μL RNA samples (orange) can be clearly differentiated from the no RNA controls (gray) and (iii) 1 GE/μL RNA samples (orange) can also be distinguished from the no RNA controls (gray). (C) (i) In contrast, “direct sample amplification”, where only a small sample volume (e.g., 1 μL) can be added into the reaction mixture, can lead to poorer detection sensitivity. (ii) Directly amplified 100 GE/μL RNA samples (blue) can still be clearly differentiated from the no RNA controls (gray), but (iii) directly amplified 1 GE/μL RNA samples (blue) become barely distinguishable from the no RNA controls (gray). (D) POC-CRISPR detects 10000 to 100 TCID50/μL of SARS-CoV-2 virus spiked into 3 independent NP swab eluates. These results demonstrate that POC-CRISPR is compatible with multiple biological samples for viral loads that span 3 orders of magnitude. Data in (B) and (C) presented as mean (solid line) ± 1SD (shade), n = 2. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

To demonstrate the advantage of magnetic-mediated concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in POC-CRISPR, we compared SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection via the POC-CRISPR workflow, which entails sample concentration and amplification (Fig. 3B(i)), and direct sample amplification (Fig. 3C(i)). POC-CRISPR could clearly detect 100 μL of 100 GE/μL RNA, as the amplification curves showed onsets of fluorescence increase at ~15 min and steady increases thereafter until 60 min, which were distinct from the slightly decreasing curves in control reactions with no RNA template (Fig. 3B(ii)). POC-CRISPR could also detect down to 1 GE/μL RN in 100 μL of sample volume (Fig. 3B(iii)). Notably, the amplification curves from 1 GE/μL RNA became distinguishable from the slightly decreasing curves from no RNA controls after only ~30 min, suggesting the possibility of shortening the turnaround time of POC-CRISPR. To our knowledge, these results also represent the first real-time monitoring of a CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection assay within a POC-amenable device. For direct sample amplification, we spiked 1 μL SARS-CoV-2 RNA directly into the CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA reaction mixture well of the cartridge and initiated the reaction (Fig. 3C(i)). Under direct amplification, samples containing 100 GE/μL RNA were still clearly detected (Fig. 3C(ii)), though the amplification curves showed slower onsets of fluorescence increase at ~20 min and lower fluorescence signals than those from samples that had been magnetically concentrated. Samples containing 1 GE/μL RNA yielded amplification curves that decreased during incubation and appeared similar to control reactions with no RNA template (Fig. 3C(iii)). This comparison illustrates that sample concentration in POC-CRISPR helps detect low concentrations of RNA, which would improve analytical sensitivity, potentially reducing false negatives and enhancing clinical sensitivity.

We further examined the analytical performance of POC-CRISPR by testing contrived nasopharyngeal (NP) swab eluates with spiked inactivated SARS-CoV-2 viral particles. To do so, we tested a 10-fold dilution series from 10000 to 100 TCID50/μL of viral particles spiked into three independent negative clinical swab eluates. We could detect SARS-CoV-2 in all samples, which demonstrates that POC-CRISPR is compatible with samples of different origins over a broad viral concentration range (Fig. 3D and Figure S12). Additionally, we demonstrated the flexibility of POC-CRISPR in using varying sample volumes by testing samples composed of 10, 30, and 100 μL of contrived samples with 100 TCID50/μL spiked viral particles (Figure S13). The results indicate that the magnetic beads could indeed capture and concentrate the RNA from lysed SARS-CoV-2 viral particles from up to 100 μL sample volume, and the sensitivity of POC-CRISPR for SARS-CoV-2 detection can be potentially improved by increasing the sample volume.

3.5. Evaluation of POC-CRISPR in clinical sample testing

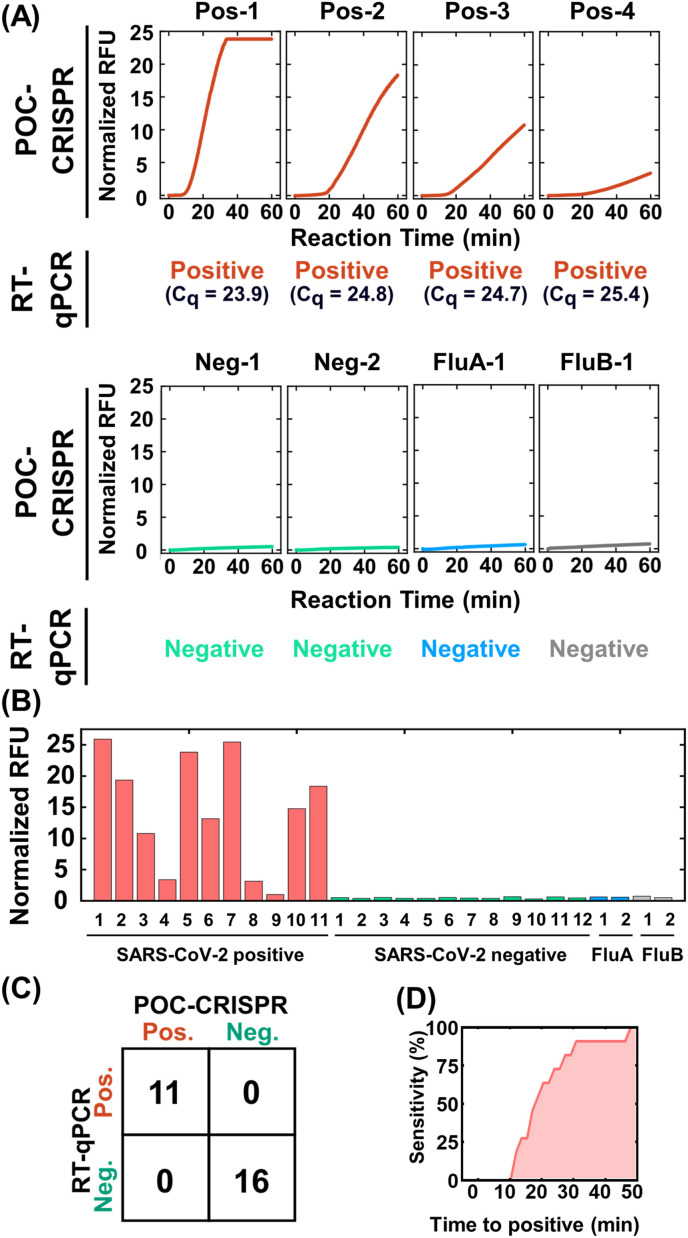

We evaluated the performance of POC-CRISPR in detecting SARS-CoV-2 directly from unprocessed clinical NP swab eluates. Here, we tested 27 clinical NP swab eluates, which were pre-typed by benchtop RT-qPCR using the CDC-approved primers and probe (Lu et al., 2020) as 11 SARS-CoV-2 positive and 16 SARS-CoV-2 negative. For the 11 positive samples, the RT-qPCR cycle of quantification (Cq) values ranged from 18.3 to 30.2 (Table S4). Of the 16 negative samples, 2 were Influenza A (Flu A) positive and 2 were Influenza B (Flu B) positive, which were included for evaluating the specificity of POC-CRISPR. For SARS-CoV-2 positive samples, POC-CRISPR yielded robust fluorescence amplification curves, and samples with Cq < 25 showed onsets of fluorescence increase in < 20 min (Fig. 4 A and Figure S14). In contrast, for SARS-CoV-2 negative samples, POC-CRISPR appropriately showed only negligible increase in the fluorescence signals and no cross-reactivity with all Influenza samples after 60 min (Fig. 4A). For accurately typing the SARS-CoV-2 positive samples with weaker fluorescence signals, we defined the fluorescence signal threshold at 3 standard deviations above the mean normalized endpoint fluorescence signals of the 16 SARS-CoV-2 negative samples (see Supplementary Information for explanation). Based on this standard thresholding strategy, POC-CRISPR could indeed detect the 11 SARS-CoV-2 positive samples (Fig. 4B), including the positive sample with the weakest fluorescence signals (i.e., Positive Sample #9, RT-qPCR Cq = 30.2) (Figure S14). For these 27 pre-typed samples, POC-CRISPR achieved 27 out of 27 concordance with RT-qPCR (Fig. 4C). Importantly, real-time fluorescence detection in POC-CRISPR accelerates testing turnaround time without sacrificing the sensitivity for detecting the 11 positive samples. Indeed, all 11 positive samples reported time-to-positive – defined as the time at which the fluorescence signal reached the fluorescence signal threshold – within 50 min (Fig. 4D and Figure S14). These results demonstrate the potential of leveraging real-time fluorescent detection and live reporting in POC-CRISPR for achieving rapid SARS-CoV-2 detection.

Fig. 4.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 from unprocessed clinical NP swab eluates via POC-CRISPR. Twenty-seven clinical NP swab eluates that are pre-typed by standard RT-qPCR (11 positive and 16 negative including 2 Inflenza A and 2 Influenza B samples) are tested by POC-CRISPR without prior sample processing steps. (A) SARS-CoV-2 positive samples result in fluorescence amplification curves, whereas negative samples – including the Influenza samples – yield negligible fluorescence increases. (B) By comparing the normalized endpoint (i.e., 60 min) fluorescent intensities after POC-CRISPR, the fluorescent signals of SARS-CoV-2 positive samples are higher than the SARS-CoV-2 negative samples, resulting in (C) 27 out of 27 concordance between POC-CRISPR and benchtop RT-qPCR. (D) By virtue of real-time fluorescence detection, POC-CRISPR accelerates testing turnaround time without sacrificing the sensitivity for detecting the 11 positive samples. Indeed, 7 out of the 11 positive samples are identified in 20 min, and all of the 11 positive samples are detected in 50 min.

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have developed POC-CRISPR, the first CRISPR-Cas-assisted assay that is fully integrated with sample preparation and automated within a POC-amenable device. For developing POC-CRISPR, we first developed an integrated benchtop assay by successfully coupling CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted RT-RPA with DM-enabled sample preparation and tuning various assay components (e.g., reverse transcriptase) and reaction conditions (e.g., reaction temperature). We subsequently actualized POC-CRISPR by adapting the newly integrated benchtop assay within our inexpensive and disposable assay cartridge and our palm-sized DM device, which executed the assay in full automation. By performing an one-step assay that integrates sample preparation and real-time fluorescence detection within a sealedand disposable cartridge and an automated and portable device, POC-CRISPR offers a single-use diagnostic test with can quantitative (and hence reliable) detection while reducing contamination, making it highly amenable for POC. We demonstrated that POC-CRISPR is capable of sensitive and rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA – 1 GE/μL from a sample volume of 100 μL in 30 min – which ranks among the most sensitive and fastest CRISPR-Cas-assisted SARS-CoV-2 detection to date. We evaluated the performance of POC-CRISPR by testing 27 unprocessed clinical NP swab eluates that were pre-typed with benchtop RT-qPCR, and POC-CRISPR correctly differentiated the 11 positive samples with Cq between 18.3 and 30.2 from the 16 negative samples. Finally, real-time fluorescence detection in POC-CRISPR enabled identification of positive samples with Cq < 25 in 20 min.

We foresee building on our initial results and taking several routes for improving and expanding POC-CRISPR. First, we would prioritize improving the analytical sensitivity of POC-CRISPR toward testing clinical samples with low SARS-CoV-2 viral loads (e.g., RT-qPCR Cq » 30). This can be achieved by designing and screening new RPA primers and optimizing the magnetic bead buffer so that the input volume of NP swab eluate can be further increased. Second, although POC-CRISPR already involves only a simple manual operation with < 2 min hands-on time after the NP swab was collected, we envision improving the user-friendliness of POC-CRISPR with new cartridge designs that simplify sample injection and mixing with magnetic bead buffers. Third, we plan to expand the number of reaction wells per assay cartridge so that we can add a control to POC-CRISPR. Finally, as both DM-enabled sample preparation and CRISPR-Cas-assisted assay can be readily designed for other DNA or RNA targets, we foresee applying POC-CRISPR toward other diseases such as HIV and Influenza. Taken together, POC-CRISPR not only represents a significant advance for CRISPR-Cas-assisted diagnostic assays but also has strong potential to become a useful POC diagnostic tool for COVID-19 and other diseases.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Fan-En Chen: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Pei-Wei Lee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Alexander Y. Trick: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Joon Soo Park: Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Liben Chen: Methodology, Resources. Kushagra Shah: Resources. Heba Mostafa: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Karen C. Carroll: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Kuangwen Hsieh: Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Tza-Huei Wang: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Institutes of Health (R01AI138978 and R61AI15462). KH is grateful for the financial support from the Sherrilyn and Ken Fisher Center for Environmental Infectious Diseases and the Center for AIDS Research at Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2021.113390.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Arizti-Sanz J., Freije C.A., Stanton A.C., Petros B.A., Boehm C.K., Siddiqui S., Shaw B.M., Adams G., Kosoko-Thoroddsen T.-S.F., Kemball M.E., Uwanibe J.N., Ajogbasile F.V., Eromon P.E., Gross R., Wronka L., Caviness K., Hensley L.E., Bergman N.H., MacInnis B.L., Happi C.T., Lemieux J.E., Sabeti P.C., Myhrvold C. Streamlined inactivation, amplification, and Cas13-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5921. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19097-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assennato S.M., Ritchie A.V., Nadala C., Goel N., Tie C., Nadala L.M., Zhang H., Datir R., Gupta R.K., Curran M.D., Lee H.H. Performance evaluation of the SAMBA II SARS-CoV-2 test for point-of-care detection of SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;59 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01262-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A., Zinger T., Inglima K., Woo K., Atie O., Yurasits L., See B., Aguero-Rosenfeld M.E. Performance of Abbott ID now COVID-19 rapid nucleic acid amplification test using nasopharyngeal swabs transported in viral transport media and dry nasal swabs in a New York city academic institution. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01136-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya R.P., Thakku S.G., Hung D.T. Harnessing CRISPR effectors for infectious disease diagnostics. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018;4:1278–1282. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendish N.J., Poole S., Naidu V.V., Mansbridge C.T., Norton N.J., Wheeler H., Presland L., Kidd S., Cortes N.J., Borca F., Phan H., Babbage G., Visseaux B., Ewings S., Clark T.W. Clinical impact of molecular point-of-care testing for suspected COVID-19 in hospital (COV-19POC): a prospective, interventional, non-randomised, controlled study. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:1192–1200. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30454-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broughton J.P., Deng X., Yu G., Fasching C.L., Servellita V., Singh J., Miao X., Streithorst J.A., Granados A., Sotomayor-Gonzalez A., Zorn K., Gopez A., Hsu E., Gu W., Miller S., Pan C.-Y., Guevara H., Wadford D.A., Chen J.S., Chiu C.Y. CRISPR–Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:870–874. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Easley C.J., Ferrance J.P., Landers J.P. Chitosan as a polymer for pH-induced DNA capture in a totally aqueous system. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:7222–7228. doi: 10.1021/ac060391l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.S., Ma E., Harrington L.B., Da Costa M., Tian X., Palefsky J.M., Doudna J.A. CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science. 2018;360:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.aar6245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou C.-H., Jin Shin D., Zhang Y., Wang T.-H. Topography-assisted electromagnetic platform for blood-to-PCR in a droplet. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013;50:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2013.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu C. Cutting-edge infectious disease diagnostics with CRISPR. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:702–704. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier D.A., Assennato S.M., Warne B., Sithole N., Sharrocks K., Ritchie A., Ravji P., Routledge M., Sparkes D., Skittrall J., Smielewska A., Ramsey I., Goel N., Curran M., Enoch D., Tassell R., Lineham M., Vaghela D., Leong C., Mok H.P., Bradley J., Smith K.G.C., Mendoza Vivienne, Demiris N., Besser M., Dougan G., Lehner P.J., Siedner M.J., Zhang H., Waddington C.S., Lee H., Gupta R.K., Baker S., Bradley J., Dougan G., Goodfellow I., Gupta R.K., Lehner P.J., Lyons P., Matheson N.J., Smith K.G.C., Toshner M., Weekes M.P., Brown N., Curran M., Palmar S., Zhang H., Enoch D., Chapman D., Shaw A., Mendoza Vivien, Jose S., Bermperi A., Zerrudo J.A., Kourampa E., Saunders C., de Jesus R., Domingo J., Pasquale C., Vergese B., Vargas P., Fabiculana M., Perales M., Skells R., Mynott L., Blake E., Bates A., Vallier A., Williams A., Phillips D., Chiu E., Overhill A., Ramenante N., Sipple J., Frost S., Knock H., Hardy R., Foster E., Davidson F., Rundell V., Bundi P., Abeseabe R., Clark S., Vicente I. Point of care nucleic acid testing for SARS-CoV-2 in hospitalized patients: a clinical validation trial and implementation study. Cell Reports Med. 2020;1:100062. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X., Yin K., Li Z., Lalla R.V., Ballesteros E., Sfeir M.M., Liu C. Ultrasensitive and visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 using all-in-one dual CRISPR-Cas12a assay. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:4711. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fozouni P., Son S., Díaz de León Derby M., Knott G.J., Gray C.N., D'Ambrosio M.V., Zhao C., Switz N.A., Kumar G.R., Stephens S.I., Boehm D., Tsou C.-L., Shu J., Bhuiya A., Armstrong M., Harris A.R., Chen P.-Y., Osterloh J.M., Meyer-Franke A., Joehnk B., Walcott K., Sil A., Langelier C., Pollard K.S., Crawford E.D., Puschnik A.S., Phelps M., Kistler A., DeRisi J.L., Doudna J.A., Fletcher D.A., Ott M. Amplification-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR-Cas13a and mobile phone microscopy. Cell. 2021;184:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.12.001. e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibani M.M., Toumazou C., Sohbati M., Sahoo R., Karvela M., Hon T.-K., De Mateo S., Burdett A., Leung K.Y.F., Barnett J., Orbeladze A., Luan S., Pournias S., Sun J., Flower B., Bedzo-Nutakor J., Amran M., Quinlan R., Skolimowska K., Herrera C., Rowan A., Badhan A., Klaber R., Davies G., Muir D., Randell P., Crook D., Taylor G.P., Barclay W., Mughal N., Moore L.S.P., Jeffery K., Cooke G.S. Assessing a novel, lab-free, point-of-care test for SARS-CoV-2 (CovidNudge): a diagnostic accuracy study. The Lancet Microbe. 2020;1:e300–e307. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30121-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Lee J.W., Essletzbichler P., Dy A.J., Joung J., Verdine V., Donghia N., Daringer N.M., Freije C.A., Myhrvold C., Bhattacharyya R.P., Livny J., Regev A., Koonin E.V., Hung D.T., Sabeti P.C., Collins J.J., Zhang F. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science. 2017;356:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Sun X., Wang X., Liang C., Jiang H., Gao Q., Dai M., Qu B., Fang S., Mao Y., Chen Y., Feng G., Gu Q., Wang R.R., Zhou Q., Li W. SARS-CoV-2 detection with CRISPR diagnostics. Cell Discov. 2020;6:34. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0174-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T., Zeng W., Yang M., Chen W., Ren L., Ai J., Wu J., Liao Y., Gou X., Li Y., Wang X., Su H., Gu B., Wang J., Xu T. Development and evaluation of a rapid CRISPR-based diagnostic for COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K., Zhao G., Wang T.-H. Applying biosensor development concepts to improve preamplification-free CRISPR/Cas12a-Dx. Analyst. 2020;145:4880–4888. doi: 10.1039/D0AN00664E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Tian D., Liu Y., Lin Z., Lyon C.J., Lai W., Fusco D., Drouin A., Yin X., Hu T., Ning B. Ultra-sensitive and high-throughput CRISPR-p owered COVID-19 diagnosis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;164:112316. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung J., Ladha A., Saito M., Kim N.-G., Woolley A.E., Segel M., Barretto R.P.J., Ranu A., Macrae R.K., Faure G., Ioannidi E.I., Krajeski R.N., Bruneau R., Huang M.-L.W., Yu X.G., Li J.Z., Walker B.D., Hung D.T., Greninger A.L., Jerome K.R., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Zhang F. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 with SHERLOCK one-pot testing. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383:1492–1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2026172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann U., Vandevyver C., Parashar V.K., Gijs M.A.M. Droplet-based DNA purification in a magnetic lab-on-a-chip. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:3062–3067. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Li S., Wang J., Liu G. CRISPR/Cas systems towards next-generation biosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 2019;37:730–743. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffelholz M.J., Alland D., Butler-Wu S.M., Pandey U., Perno C.F., Nava A., Carroll K.C., Mostafa H., Davies E., McEwan A., Rakeman J.L., Fowler R.C., Pawlotsky J.-M., Fourati S., Banik S., Banada P.P., Swaminathan S., Chakravorty S., Kwiatkowski R.W., Chu V.C., Kop J., Gaur R., Sin M.L.Y., Nguyen D., Singh S., Zhang N., Persing D.H. Multicenter evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert xpress SARS-CoV-2 test. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00926-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X., Wang L., Sakthivel S.K., Whitaker B., Murray J., Kamili S., Lynch B., Malapati L., Burke S.A., Harcourt J., Tamin A., Thornburg N.J., Villanueva J.M., Lindstrom S. US CDC real-time reverse transcription PCR panel for detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26:1654–1665. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattingly T.J., Fulton A., Lumish R.A., Williams A.M.C., Yoon S.J., Yuen M., Heil E.L. The cost of self-reported penicillin allergy: a systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018;6:1649–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.12.033. e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning B., Yu T., Zhang S., Huang Z., Tian D., Lin Z., Niu A., Golden N., Hensley K., Threeton B., Lyon C.J., Yin X.-M., Roy C.J., Saba N.S., Rappaport J., Wei Q., Hu T.Y. A smartphone-read ultrasensitive and quantitative saliva test for COVID-19. Sci. Adv. 2021;7 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notomi T. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:63e–63. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.e63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nouri R., Tang Z., Dong M., Liu T., Kshirsagar A., Guan W. CRISPR-based detection of SARS-CoV-2: a review from sample to result. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;178:113012. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.S., Hsieh K., Chen L., Kaushik A., Trick A.Y., Wang T. Digital CRISPR/Cas‐Assisted assay for rapid and sensitive detection of SARS‐CoV‐2. Adv. Sci. 2021 doi: 10.1002/advs.202003564. 2003564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchsung M., Jantarug K., Pattama A., Aphicho K., Suraritdechachai S., Meesawat P., Sappakhaw K., Leelahakorn N., Ruenkam T., Wongsatit T., Athipanyasilp N., Eiamthong B., Lakkanasirorat B., Phoodokmai T., Niljianskul N., Pakotiprapha D., Chanarat S., Homchan A., Tinikul R., Kamutira P., Phiwkaow K., Soithongcharoen S., Kantiwiriyawanitch C., Pongsupasa V., Trisrivirat D., Jaroensuk J., Wongnate T., Maenpuen S., Chaiyen P., Kamnerdnakta S., Swangsri J., Chuthapisith S., Sirivatanauksorn Y., Chaimayo C., Sutthent R., Kantakamalakul W., Joung J., Ladha A., Jin X., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Zhang F., Horthongkham N., Uttamapinant C. Clinical validation of a Cas13-based assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:1140–1149. doi: 10.1038/s41551-020-00603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piepenburg O., Williams C.H., Stemple D.L., Armes N.A. DNA detection using recombination proteins. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:1115–1121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D.J., Athamanolap P., Chen L., Hardick J., Lewis M., Hsieh Y.H., Rothman R.E., Gaydos C.A., Wang T.H. Mobile nucleic acid amplification testing (mobiNAAT) for Chlamydia trachomatis screening in hospital emergency department settings. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04781-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D.J., Trick A.Y., Hsieh Y.H., Thomas D.L., Wang T.H. Sample-to-Answer droplet magnetofluidic platform for point-of-care hepatitis C viral load quantitation. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28124-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trick A.Y., Melendez J.H., Chen F.-E., Chen L., Onzia A., Zawedde A., Nakku-Joloba E., Kyambadde P., Mande E., Matovu J., Atuheirwe M., Kwizera R., Gilliams E.A., Hsieh Y., Gaydos C.A., Manabe Y.C., Hamill M.M., Wang T. A portable magnetofluidic platform for detecting sexually transmitted infections and antimicrobial susceptibility. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf6356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R., Qian C., Pang Y., Li M., Yang Y., Ma H., Zhao M., Qian F., Yu H., Liu Z., Ni T., Zheng Y., Wang Y. opvCRISPR: one-pot visual RT-LAMP-CRISPR platform for SARS-cov-2 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;172:112766. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization COVID-19 public Health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) global research and innovation forum. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern-(pheic)-global-research-and-innovation-forum [WWW document]

- Zhang Y., Park S., Liu K., Tsuan J., Yang S., Wang T.H. A surface topography assisted droplet manipulation platform for biomarker detection and pathogen identification. Lab Chip. 2011;11:398–406. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00296h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Wang T.H. Full-range magnetic manipulation of droplets via surface energy traps enables complex bioassays. Adv. Mater. 2013;25:2903–2908. doi: 10.1002/adma.201300383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen W., Smith E., Manji R., Schron D., Berry G.J. Clinical evaluation of three sample-to-answer platforms for detection of SARS-CoV-2. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020;58 doi: 10.1128/JCM.00783-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L., Peng R., Zhang R., Li J. The applications of CRISPR/Cas system in molecular detection. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2018;22:5807–5815. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.