Abstract

Background

Evidence regarding the risk of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 among people with disabilities (PwDs) is scarce.

Objective

This study investigated the association of disability status with the risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) test positivity and the risk of major adverse clinical outcomes among participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

This study included all patients (n = 8070) who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and individuals without COVID-19 (n = 121,050) in South Korea from January 1 to May 30, 2020. The study variables included officially registered disability status from the government, SARS-CoV-2 test positivity, and major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 (admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death).

Results

The study participants included 129,120 individuals (including 7261 PwDs), of whom 8070 (6.3%) tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, PwDs had an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity compared with people without disabilities (odds ratio [OR]: 1.36, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.24–1.48). Among participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, PwDs were associated with an increased risk of major adverse clinical outcomes from COVID-19 compared to those without disabilities (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.11–1.86).

Conclusions

PwDs had an increased risk of COVID-19 and major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with people without disabilities. Given the higher vulnerability of PwDs to COVID-19, tailored policy and management to protect against the risk of COVID-19 are required.

Keywords: Disability, COVID-19, Major adverse clinical outcomes, Korean

Introduction

Globally, there were 115.7 million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) by March 07, 2020, including 2.6 million deaths according to World Health Organization, and the spread of COVID-19 is predicted to increase worldwide.1 Various risk factors for infection and severe outcomes of COVID-19 have been investigated.2 , 3 However, the wide-ranging effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with disabilities (PwDs) has received relatively little attention, and the development of evidence-based guidelines on COVID-19 for PwDs are lagging behind and are being given lower priority than those for people without disabilities.4 Disability is a lack or restriction of ability to perform an activity in any domain of life.5 Approximately 15% of the world's population is estimated to live with some form of disability6 and the number of registered PwDs in South Korea has increased (from 1,134,177 in 2001 to 2,585,876 in 2018), which accounts for approximately 5% of the total population.7 Given the vulnerability of PwDs to COVID-19 due to their physical or mental impairments, the right of this population to be protected from COVID-19, and the increasing number of PwDs due to population aging and a global increase in the prevalence of chronic health conditions,8 there is a need to investigate the risk of COVID-19 among PwDs.

Previous studies examined the association of disability characteristics with the incidence of COVID-19 and death using the U.S. regional data9, 10, 11; however, personal data, such as sex, age, and chronic diseases, were not considered in these studies. Therefore, no evidence regarding the association between disability characteristics with COVID-19 incidence and death was found using personal data. Other previous studies have examined trends in COVID-19 and COVID-19-related deaths among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.12, 13, 14 However, they included only a few types of disability and did not consider potential confounding factors, such as underlying comorbidities. In other words, there is no evidence for the association between disability status and risk of COVID-19. It is necessary to examine the association between disability status, including all types, and risk of COVID-19, after controlling individual characteristics.

This study assessed the association between disability status and risk of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) test positivity among all study participants. This study also investigated the relationship between disability status and risk of major adverse clinical outcomes (admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death) among participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Data source and participants

This study used national data from the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS), which provides mandatory health insurance for all Korean citizens. As Korea has a single-payer national health system, the NHIS has all insured individuals’ demographic information (e.g., sex, age, household income, residential area, disability status); all medical records regarding diagnoses, treatments, and prescribed drugs; and death information.15 The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) database has epidemiological information on all individuals who have been tested for SARS-CoV-2, and the information on SARS-CoV-2 test results in the KCDC dataset is linked to the NHIS database.16

The NHIS provided data on all patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between January 1 and May 30, 2020. The NHIS also provided data on comparison groups from the general population who did not test for SARS-CoV-2 during the same period. Among the general population, the comparison group was selected based on characteristics for sex, age, and residential area similar to those of the patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 using simple stratified sampling. This study included 8070 patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and 121,050 controls.

Measures

This study used information on disability status as assessed by physicians and officially registered by the national government. For an individual to be registered as disabled, they needed to submit documents, including the diagnosis established by a physician, to a local National Pension Service office, which then notifies the applicant of the results, including the registered type and grade of the disability.17 The severity of disability is classified as mild (grades 4–6) or severe (grades 1–3) on the basis of functional losses and clinical impairment. Mild disability was defined as the ability to perform some daily tasks independently even though there may be a partial need for assistive devices or personal assistance. Severe disability was defined as increased dependence on assistive devices or personal assistance. The National Pension Service categorizes disabilities into 15 types, which include physical disability, disability due to brain injury, visual disability, hearing disability, speech and language disability, intellectual disability, disability due to mental disorder, speech and language disability, and disability due to autism spectrum disorder, heart problems, respiratory problems, liver disease, facial disfigurement, excretory problems, and epilepsy.

The primary outcome in this study was SARS-CoV-2 test positivity among all study participants. The secondary outcome was major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19, which comprised admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death.

The potentially confounding factors included sex, age, residential area, household income, and comorbidities. During the initial epidemic period in South Korea, there was an explosive outbreak of COVID-19 in the Daegu and Gyeongbuk regions18; therefore, study participants were categorized as living in Daegu and Gyeongbuk or other regions. Household income was divided into quintiles. A history of diabetes mellitus (E10–14), hypertension (I10–15), dyslipidemia (E78), ischemic heart disease (I20–25), stroke (I60–63), chronic kidney disease (N18), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (J43–J44, except J430), asthma (J45–J46), cancer (C00–97), mental illness (F00–99), and chronic liver disease (K704, K711, K713–K715, K721, K73, K743, K767–K769) were confirmed by the reporting of at least two claims within 1 year during the 3-year period before COVID-19 outbreak using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Revision code.19

Statistical analysis

First, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all study participants were compared according to disability status using Pearson's chi-square tests. To explore the association of disability status and severity of disability with the risk of COVID-19, multivariable conditional logistic regression was performed after adjusting for household income and comorbidities. Second, among participants with COVID-19, Pearson's chi-square tests were used to compare sociodemographic and clinical characteristics with respect to disability status. To examine the association of disability status and the severity of the disability with the major adverse clinical outcomes from COVID-19, this study used multivariable conditional logistic regression models after adjusting for sex, age, residential area, household income, and comorbidities.

All data extraction and statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The Yonsei University Institutional Review Board approved this study (approval number: 7001988-202010-HR-1016-01 E).

Results

The general characteristics of the study participants according to COVID-19 status and major adverse clinical outcomes are shown in Table 1, Table 2 . Table 1 shows that the proportion of PwDs was higher among people with COVID-19 than among those without COVID-19 (7.7% vs. 5.5%). Table 2 shows that the proportion of PwDs was substantially higher among people with major adverse outcomes than among those without major adverse outcomes (23.9% vs. 6.6%).

Table 1.

General characteristics of study participants according to COVID-19 status.

| Variables | Total | With COVID-19 |

Without COVID-19 |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Total | 129,120 | 8070 | 6.3 | 121,050 | 93.8 | ||

| Men | 51,776 | 3236 | 40.1 | 48,540 | 40.1 | 1.000 | |

| Age group (years) | 1.000 | ||||||

| 0–9 | 1296 | 81 | 1.0 | 1215 | 1.0 | ||

| 10–19 | 4416 | 276 | 3.4 | 4140 | 3.4 | ||

| 20–29 | 32,912 | 2057 | 25.5 | 30,855 | 25.5 | ||

| 30–39 | 13,312 | 832 | 10.3 | 12,480 | 10.3 | ||

| 40–49 | 16,576 | 1036 | 12.8 | 15,540 | 12.8 | ||

| 50–59 | 25,072 | 1567 | 19.4 | 23,505 | 19.4 | ||

| 60–69 | 19,184 | 1199 | 14.9 | 17,985 | 14.9 | ||

| 70≤ | 16,352 | 1022 | 12.7 | 15,330 | 12.7 | ||

| Residential area | 1.000 | ||||||

| Daegu and Gyeongbuk | 84,224 | 5264 | 65.2 | 78,960 | 65.2 | ||

| Other regions | 44,896 | 2806 | 34.8 | 42,090 | 34.8 | ||

| Household income | <0.001 | ||||||

| First quantile (lowest) | 31,769 | 2401 | 29.8 | 29,368 | 24.3 | ||

| Second quantile | 19,140 | 1101 | 13.6 | 18,039 | 14.9 | ||

| Third quantile | 21,829 | 1311 | 16.2 | 20,518 | 17.0 | ||

| Fourth quantile | 24,289 | 1348 | 16.7 | 22,941 | 19.0 | ||

| Fifth quantile (highest) | 32,093 | 1909 | 23.7 | 30,184 | 24.9 | ||

| Disability status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 7261 | 619 | 7.7 | 6642 | 5.5 | ||

| No | 121,859 | 7451 | 92.3 | 114,408 | 94.5 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17,288 | 1185 | 14.7 | 16,103 | 13.3 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 26,716 | 1662 | 20.6 | 25,054 | 20.7 | 0.826 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 35,702 | 2268 | 28.1 | 33,434 | 27.6 | 0.347 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5818 | 399 | 4.9 | 5419 | 4.5 | 0.050 | |

| Stroke | 3525 | 266 | 3.3 | 3259 | 2.7 | 0.001 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1717 | 136 | 1.7 | 1581 | 1.3 | 0.004 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1467 | 80 | 1.0 | 1387 | 1.1 | 0.205 | |

| Cancer | 5764 | 361 | 4.5 | 5403 | 4.5 | 0.967 | |

| Asthma | 14,258 | 953 | 11.8 | 13,305 | 11.0 | 0.023 | |

| Mental illness | 26,176 | 1928 | 23.9 | 24,248 | 20.0 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 23,054 | 1500 | 18.6 | 21,554 | 17.8 | 0.076 | |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease.

Table 2.

General characteristics of patients with COVID-19 according to major adverse clinical outcomes.

| Variables | Total | With major adverse clinical outcomes |

Without major adverse clinical outcomes |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Total | 8070 | 507 | 6.3 | 7563 | 93.7 | ||

| Men | 3236 | 281 | 55.4 | 2955 | 39.1 | <0.001 | |

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 20–59 | 5849 | 108 | 21.3 | 5741 | 75.9 | ||

| 60≤ | 2221 | 399 | 78.7 | 1822 | 24.1 | ||

| Residential area | <0.001 | ||||||

| Daegu and Gyeongbuk | 5264 | 285 | 56.2 | 4979 | 65.8 | ||

| Other regions | 2806 | 222 | 43.8 | 2584 | 34.2 | ||

| Household income | <0.001 | ||||||

| First quantile (lowest) | 2401 | 165 | 32.5 | 2236 | 29.6 | ||

| Second quantile | 1101 | 37 | 7.3 | 1064 | 14.1 | ||

| Third quantile | 1311 | 77 | 15.2 | 1234 | 16.3 | ||

| Fourth quantile | 1348 | 80 | 15.8 | 1268 | 16.8 | ||

| Fifth quantile (highest) | 1909 | 148 | 29.2 | 1761 | 23.3 | ||

| Disability status | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 619 | 121 | 23.9 | 498 | 6.6 | ||

| No | 7451 | 386 | 76.1 | 7065 | 93.4 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1185 | 216 | 42.6 | 969 | 12.8 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 1662 | 308 | 60.7 | 1354 | 17.9 | <0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 2268 | 291 | 57.4 | 1977 | 26.1 | <0.001 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 399 | 78 | 15.4 | 321 | 4.2 | <0.001 | |

| Stroke | 266 | 68 | 13.4 | 198 | 2.6 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 136 | 41 | 8.1 | 95 | 1.3 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 80 | 27 | 5.3 | 53 | 0.7 | <0.001 | |

| Cancer | 361 | 55 | 10.8 | 306 | 4.0 | <0.001 | |

| Asthma | 953 | 104 | 20.5 | 849 | 11.2 | <0.001 | |

| Mental illness | 1928 | 286 | 56.4 | 1642 | 21.7 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 1500 | 153 | 30.2 | 1347 | 17.8 | <0.001 | |

The major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 comprised admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics according to disability status are presented in Table 3 . This study identified 7261 PwDs and 121,859 people without disabilities. The proportions of men; older adults (≥60 years); individuals living in regions other than Daegu and Gyeongbuk; individuals with low household income; and individuals with certain medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, cancer, asthma, mental illness, and chronic liver disease, were significantly higher among PwDs than among people without disabilities.

Table 3.

Characteristics of study participants according to disability status.

| Variables | Total | People with disabilities |

People without disabilities |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 129,120 | 7261 | 5.6 | 121,859 | 94.4 | |

| Men | 51,776 | 3688 | 50.8 | 48,088 | 39.5 | <0.001 |

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | |||||

| 0–9 | 1296 | 14 | 0.2 | 1282 | 1.1 | |

| 10–19 | 4416 | 52 | 0.7 | 4364 | 3.6 | |

| 20–29 | 32,912 | 458 | 6.3 | 32,454 | 26.6 | |

| 30–39 | 13,312 | 241 | 3.3 | 13,071 | 10.7 | |

| 40–49 | 16,576 | 455 | 6.3 | 16,121 | 13.2 | |

| 50–59 | 25,072 | 1239 | 17.1 | 23,833 | 19.6 | |

| 60–69 | 19,184 | 1670 | 23.0 | 17,514 | 14.4 | |

| ≥70 | 16,352 | 3132 | 43.1 | 13,220 | 10.8 | |

| Residential area | 0.003 | |||||

| Daegu and Gyeongbuk | 84,224 | 4618 | 63.6 | 79,606 | 65.3 | |

| Other regions | 44,896 | 2643 | 36.4 | 42,253 | 34.7 | |

| Household income | <0.001 | |||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 31,769 | 2760 | 38.0 | 29,009 | 23.8 | |

| Second quintile | 19,140 | 669 | 9.2 | 18,471 | 15.2 | |

| Third quintile | 21,829 | 919 | 12.7 | 20,910 | 17.2 | |

| Fourth quintile | 24,289 | 1108 | 15.3 | 23,181 | 19.0 | |

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 32,093 | 1805 | 24.9 | 30,288 | 24.9 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 17,288 | 2461 | 33.9 | 14,827 | 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 26,716 | 3788 | 52.2 | 22,928 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 35,702 | 3986 | 54.9 | 31,716 | 26.0 | <0.001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 5818 | 1028 | 14.2 | 4790 | 3.9 | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 3525 | 1041 | 14.3 | 2484 | 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1717 | 380 | 5.2 | 1337 | 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1467 | 496 | 6.8 | 971 | 0.8 | <0.001 |

| Cancer | 5764 | 612 | 8.4 | 5152 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 14,258 | 1258 | 17.3 | 13,000 | 10.7 | <0.001 |

| Mental illness | 26,176 | 3705 | 51.0 | 22,471 | 18.4 | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 23,054 | 2440 | 33.6 | 20,614 | 16.9 | <0.001 |

The general characteristics of the study participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 are shown according to disability status in Table 4 , and 7.7% among them had disabilities. The proportions of men, young or middle-aged adults (≤59 years); those living in regions other than Daegu and Gyeongbuk; and those with low household income, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, ischemic heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, asthma, mental illness, or chronic liver disease among PwDs were significantly higher than those among people without disabilities.

Table 4.

Characteristics of patients with COVID-19 according to disability status.

| Variables | Total | People with disabilities |

People without disabilities |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | ||||

| Total | 8070 | 619 | 7.7 | 7451 | 92.3 | ||

| Men | 3236 | 333 | 53.8 | 2903 | 39.0 | <0.001 | |

| Age group (years) | <0.001 | ||||||

| 20–59 | 2058 | 228 | 36.8 | 1830 | 24.6 | ||

| ≥60 | 6012 | 391 | 63.2 | 5621 | 75.4 | ||

| Residential area | 0.015 | ||||||

| Daegu and Gyeongbuk | 5264 | 376 | 60.7 | 4888 | 65.6 | ||

| Other regions | 2806 | 243 | 39.3 | 2563 | 34.4 | ||

| Household income | <0.001 | ||||||

| First quintile (lowest) | 2401 | 352 | 56.9 | 2049 | 27.5 | ||

| Second quintile | 1101 | 36 | 5.8 | 1065 | 14.3 | ||

| Third quintile | 1311 | 51 | 8.2 | 1260 | 16.9 | ||

| Fourth quintile | 1348 | 70 | 11.3 | 1278 | 17.2 | ||

| Fifth quintile (highest) | 1909 | 110 | 17.8 | 1799 | 24.1 | ||

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1185 | 215 | 34.7 | 970 | 13.0 | <0.001 | |

| Hypertension | 1662 | 319 | 51.5 | 1343 | 18.0 | <0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 2268 | 347 | 56.1 | 1921 | 25.8 | <0.001 | |

| Ischemic heart disease | 399 | 73 | 11.8 | 326 | 4.4 | <0.001 | |

| Stroke | 266 | 106 | 17.1 | 160 | 2.1 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 136 | 34 | 5.5 | 102 | 1.4 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 80 | 35 | 5.7 | 45 | 0.6 | <0.001 | |

| Cancer | 361 | 30 | 4.8 | 331 | 4.4 | 0.640 | |

| Asthma | 953 | 99 | 16.0 | 854 | 11.5 | 0.001 | |

| Mental illness | 1928 | 396 | 64.0 | 1532 | 20.6 | <0.001 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 1500 | 195 | 31.5 | 1305 | 17.5 | <0.001 | |

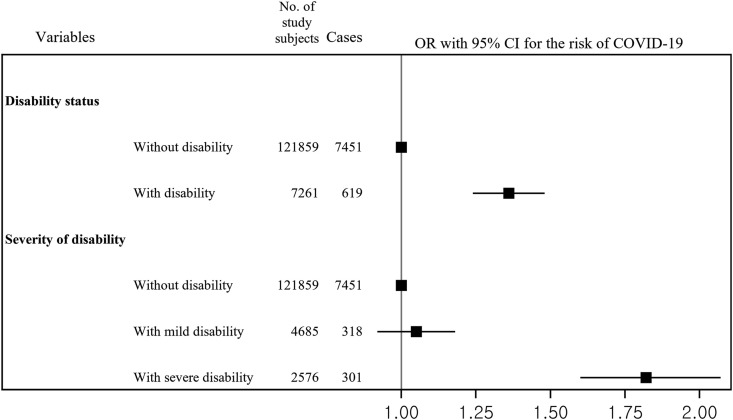

Fig. 1 shows the association between disability status and risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity. After adjusting for potential confounders, PwDs (odds ratio [OR]: 1.36, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.24–1.48) had a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity than those without disabilities. People with severe disability (OR: 1.82, 95% CI: 1.60–2.07) had a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity than those without disabilities; however, there was no significant association between mild disability and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity compared with no disability (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 0.92–1.18).

Fig. 1.

Association between disability status and the risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity.

The OR and 95% CI were calculated after adjusting for household income and comorbidities.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Fig. 2 shows the association between disability status and the risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. After adjusting for potential confounding factors, PwDs (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.11–1.86) were associated with an increased risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with people without disabilities. People with severe disability (OR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.12–2.31) were associated with an increased risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with people without disabilities; however, there was no significant association between mild disability and the risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with no disability (OR: 1.29, 95% CI: 0.93–1.78).

Fig. 2.

Association between disability status and the risk of major adverse clinical outcomes among participants who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2

The major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 comprised admission to the intensive care unit, invasive ventilation, or death. The OR and 95% CI were calculated after adjusting for sex, age, residential area, household income, and comorbidities.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; MACOs, major adverse clinical outcomes; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; COVID-19, coronavirus disease.

Discussion

This nationwide study found that PwDs had an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity compared with those without disabilities. Among people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, PwDs had a higher risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 than those without disabilities. People with severe disabilities had a higher risk of COVID-19 and major adverse clinical outcomes than those without disabilities; however, there was no significant association between mild disability and the risk of COVID-19.

There are several possible explanations for the increased risk of COVID-19 observed among PwDs. First, PwDs may have difficulty practicing routine prevention behaviors (e.g., washing hands and social distancing) due to their physical or mental health problems, especially those relying on assistance with personal care. A previous study showed that those with disabilities were significantly less likely than those without any disability to report frequent handwashing and surface disinfection.20 PwDs also have inequities in access to public health messaging, possibly making their preventive actions for COVID-19 difficult. A previous study showed that PwDs felt that relevant health information is provided in a fragmentary manner through several channels that have relatively low reliability.21 Second, PwDs may have limited access to healthcare services.22 A study showed that most PwDs were affected by a lack of access to facilities and equipment after COVID-19.23 Finally, PwDs have more chronic medical conditions, as evidenced by the data in this study (higher prevalence of chronic diseases in PwDs compared to people without disabilities). These characteristics may be associated with an increased risk of COVID-19 and worse outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic.24

This study suggests that the preparedness and response planning of COVID-19 must be inclusive of and accessible to PwDs by recognizing and addressing their challenges.4 , 25 , 26 Information on COVID-19 should be conveyed using formats accessible to people with specific types of disabilities, such as those who are blind, deaf, and have intellectual impairment. Additionally, strategies for vital in-person communication, such as sign language interpreters and wearing of transparent masks by healthcare providers to allow lip-reading, must be safe and accessible.

For PwDs with COVID-19, access to healthcare facilities, including hospitals, needs to be strengthened so that they can receive appropriate treatment for their underlying diseases, which predispose them to poorer outcomes of COVID-19. If there are no family members who can help PwDs with COVID-19, support from care workers should be provided to enable them to access healthcare services. At a policy level, the responsible authorities should give high priority and budgetary support to measures designed to reduce the risk of COVID-19 among PwDs. Healthcare staff should also be provided with rapid awareness training on the rights and diverse needs of PwDs and the need to maintain their dignity, safeguard against discrimination, and prevent inequities in care provision.

This study showed that severe disability was associated with an increased risk of COVID-19, but there was no significant association with mild disability. People with severe disability have a higher level of physical or mental functional impairment than those with mild disability, and they may experience more barriers during the COVID-19 pandemic, implying the need for specific measures for those with severe disability.27

This study had some limitations. First, this study did not adjust for some potential confounding factors, such as obesity, which may have affected the response to SARS-CoV-2 infection.28 Further studies that consider additional risk factors for COVID-19 are required. Second, this study did not determine the association between the type of disability (e.g., vision, hearing, and intellectual disability) and the risk of COVID-19 because of the data de-identification policy of the NHIS. Further study is needed to investigate the risk of COVID-19 according to disability type. Finally, this study was conducted only in South Korea; therefore, further studies are warranted to explore the associations between disability and risk of COVID-19 in other populations and countries.

Conclusions

This large nationwide study found that PwDs were associated with an increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 test positivity compared with people without disabilities. Among patients who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, PwDs were associated with an increased risk of major adverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 compared with people without disabilities. This study suggests that PwDs should be included in the COVID-19 vaccination priorities. This study suggests that further research on the causes of high risk of COVID-19 among PwDs is required to create evidence for addressing their challenges.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (grant number: 2019R1A2C1003259 and 2020R1I1A1A01053104). The funders had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. 2020. https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Wiersinga W.J., Rhodes A., Cheng A.C., Peacock S.J., Prescott H.C. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324(8):782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jordan R.E., Adab P., Cheng K.K. COVID-19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabatello M., Burke T.B., McDonald K.E., Appelbaum P.S. Disability, ethics, and health care in the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Publ Health. 2020;110(10):1523–1527. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 1980. International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps.https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/41003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2011. World Report on Disability.https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics Korea The number of registered disabled people in South Korea. 2018. http://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=117&tblId=DT_11761_N004&checkFlag=N

- 8.Zeng Y., Feng Q., Hesketh T., Christensen K., Vaupel J.W. Survival, disabilities in activities of daily living, and physical and cognitive functioning among the oldest-old in China: a cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389(10079):1619–1629. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30548-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chakraborty J. Social inequities in the distribution of COVID-19: an intra-categorical analysis of people with disabilities in the U.S. Disabil Health J. 2020:101007. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karaye I.M., Horney J.A. The impact of social vulnerability on COVID-19 in the U.S.: an analysis of spatially varying relationships. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):317–325. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olulana O., Abedi V., Avula V., et al. medRxiv; 2020. Regional Association of Disability and SARS-CoV-2 Infection in 369 Counties of the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turk M.A., Landes S.D., Formica M.K., Goss K.D. Intellectual and developmental disability and COVID-19 case-fatality trends: TriNetX analysis. Disabil Health J. 2020;13(3):100942. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landes S.D., Turk M.A., Formica M.K., McDonald K.E., Stevens J.D. COVID-19 outcomes among people with intellectual and developmental disability living in residential group homes in New York State. Disabil Health J. 2020:100969. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mills W.R., Sender S., Lichtefeld J., et al. Supporting individuals with intellectual and developmental disability during the first 100 days of the COVID-19 outbreak in the USA. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2020;64(7):489–496. doi: 10.1111/jir.12740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song S.O., Jung C.H., Song Y.D., et al. Background and data configuration process of a nationwide population-based study using the Korean national health insurance system. Diabetes Metab J. 2014;38(5):395–403. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2014.38.5.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S., Choi G.J., Ko H. Information technology-based tracing strategy in response to COVID-19 in South Korea-privacy controversies. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(21):2129–2130. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi J.W., Lee K.S., Han E. Psychiatric disorders and suicide risk among adults with disabilities: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2019;263:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shim E., Tariq A., Choi W., Lee Y., Chowell G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung C.R., Chen W.T., Tang Y.H., Hwang B.F. Fine particulate matter exposure during pregnancy and infancy and incident asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(6):2254–2262. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.03.024. e2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollis N.D., Thierry J.M., Garcia-Williams A. Self-reported handwashing and surface disinfection behaviors by U.S. adults with disabilities to prevent COVID-19. Disability and Health Journal. 2020;2021:101096. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101096. Spring. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shon C., Jeon B., Lim J.H., et al. Focus group interview regarding the accessibility of health information for people with disabilities and means of improving this accessibility in the future. Medicine (Baltim) 2020;99(8) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maart S., Jelsma J. Disability and access to health care - a community based descriptive study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(18):1489–1493. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.807883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Theis N., Campbell N., De Leeuw J., Owen M., Schenke K.C. The effects of COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity and mental health of children and young adults with physical and/or intellectual disabilities. Disabil Health J. 2021:101064. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). People with disabilities. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extraprecautions/people-with-disabilities.html

- 25.Armitage R., Nellums L.B. The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e257. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30076-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendall E., Ehrlich C., Chapman K., et al. Immediate and long-term implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities. Am J Publ Health. 2020:e1–e6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brady N.C., Bruce S., Goldman A., et al. Communication services and supports for individuals with severe disabilities: guidance for assessment and intervention. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2016;121(2):121–138. doi: 10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jung C.Y., Park H., Kim D.W., et al. Association between body mass index and risk of COVID-19: a nationwide case-control study in South Korea. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]